Evidence demonstrates that individuals from ethnic minority groups are at increased risk of COVID-19 infection, severe disease and mortality,1, 2, 3, 4 even accounting for socio-economic deprivation.5 Despite calls to ensure ethnicity is integral to COVID-19 research,6 opportunities have been missed to engage with these communities and, even more notably, recent migrants. Wide participation is needed to avoid continued tragedy in future pandemic waves.

Community engagement during COVID-19 has lacked urgency and transparency. The absence of the insights and voices of migrants and diverse ethnic groups was highlighted by the omission of stakeholder contributions in the report of Public Health England (PHE) on COVID-19 disparities,7 which was criticised for failing to advance understandings of risk factors and discrimination or provide actionable recommendations.8 Community viewpoints were subsequently published two weeks later,9 , 10 following condemnation by more than 30 organisations.8

A key finding of the report of PHE on disparities was the relationship between the country of birth and COVID-19 mortality.7 However, this went unreported, and an opportunity to robustly examine migration as a risk factor for poor outcomes was missed, echoing the stark absence of attention to the country of birth and migration status during COVID-19. This highlights the need for safe and confidential mechanisms to improve collection and reporting of migrant data across health services and research, supported by adequate funding.3

Despite the risks faced by newly arrived migrants during COVID-19,11 these groups have not been meaningfully included in engagement activities or recommendations, reflected in their under-representation in PHE's stakeholder report.9 Migrant views are also notably absent as new strategies to monitor or react to COVID-19 develop, including testing, contact tracing or social distancing and lockdown measures.

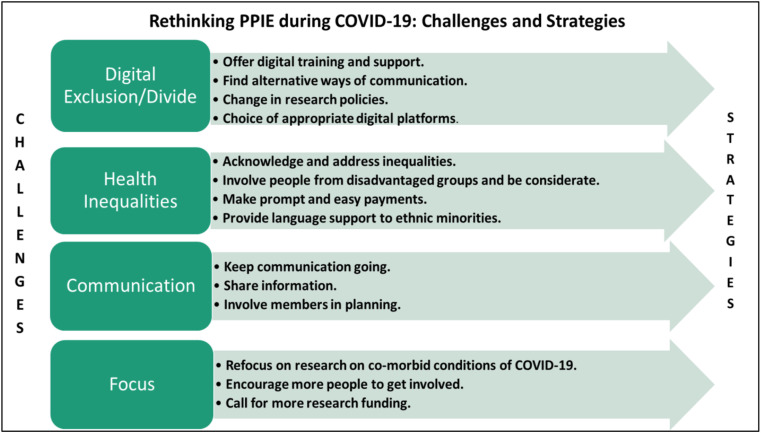

Migrants should be explicitly integrated within the COVID-19 narrative through patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) and participatory research, as well as collaboration with clinical and non-clinical healthcare workers from diverse migrant and ethnic backgrounds (see Fig. 1 ). Such involvement of migrants and other underrepresented groups is essential to guide research, to inform policy and practice and to promote accountability. This is critical in light of concerns that urgency in developing the evidence base is taking precedence over robust ethical approval processes, informed consent and PPIE.12 Research ethics committees and funders should critically evaluate proposals, indicating these communities will not be recruited as they are considered too hard to reach.

Fig. 1.

Challenges and strategies for conducting PPIE during the COVID-19 pandemic. PPIE, patient and public involvement and engagement.

Achieving meaningful engagement necessitates addressing multiple barriers to involvement across very diverse communities, including mental and physical health and disability, caring and employment responsibilities and legal status; alongside the implications, this may have for entitlement to health care, fears around immigration enforcement or stigmatisation and trust and willingness to engage with researchers.13 Transparency and inclusion is also vital and requires ongoing communication (particularly while social distancing), sharing and facilitating access to updated information (e.g., appropriate languages, multiple formats and provision of professional linkworker services) and inclusion of stakeholders in planning and responding to the pandemic. The shift to the virtual space during the COVID-19 pandemic may also impact on recruitment, accessibility and development of trust and rapport, particularly for those facing barriers owing to Internet access, digital literacy or language. This digital divide will disproportionately affect ethnic minority and migrant groups.14

The expertise these individuals bring through their lived experience, and its value in informing appropriate, effective and equitable policy and practice, should be meaningfully recognised.13 As such, engagement with migrants should be mutually beneficial, for example, the provision of PPIE payments or material contributions in recognition of the expertise these individuals have shared.15 Such contributions should be prompt and appropriate, and organisations should consider access to banking (including online banking), permission to work and recourse to public funds, ensuring such contributions do not have legal repercussions for those participating. Providing payments in cash can overcome some of these barriers. However, social distancing restrictions have made it necessary to consider virtual methods of providing PPIE payments. Mobile wallets, credit and vouchers may bypass these barriers, although it is important to consider their accessibility for those who are digitally excluded, as well the relevance and convenience of selected vendors. Defining material contributions as a recognition or ‘thank you’ for shared expertise, and determining the amount of these contributions by the type of activity (e.g., research interview, stakeholder meeting or coproducing a resource), rather than an hourly rate, may both avoid framing such payments as income and support meaningful engagement. It is also important to consider that PPIE payments may also incentivise participation, which could be coercive or lead to risk taking by target groups. Discussing these issues with target communities may be an effective and inclusive strategy for determining how to recognise PPIE contributions.

There is an urgent need to reorient research, policy and practice to address the acute needs of the populations hardest hit by the pandemic. To achieve this, it is imperative to commit to community-centred research.16 In line with good PPIE practice,17 research teams must innovatively strengthen involvement to ensure research is appropriate and impactful and proactively involve migrants and diverse ethnic groups from the outset.

The increasing recognition of inequities in COVID-19 outcomes, and pledges to challenge disparities across political, health and academic sectors, will only be realised with financial commitments. Funding bodies should adequately and equitably support migrant-focused research and promote inclusion of migrant-specific PPIE activities. We must move beyond descriptive need assessments to generate concrete actions responding to these populations, aligning with their requests for community-based research, coproduced policy and health services and targeted communications.9 Ultimately, organisations, funders and journals will be judged by their actions—not by their words.

Author statements

Competing interests

M.P. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (ARC EM), the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and an NIHR Development and Skills Enhancement Award. M.P. is a member of the Health Data Research (HDR) UK COVID-19 Taskforce. M.P., L.B.N., and M.G. receive funding from the UKRI / MRC (MR/V027549/1). L.B.N. also receives funding from the Academy of Medical Sciences (SBF005∖1047) and the Medical Research Council / Economic and Social Research Council / Arts and Humanities Research Council (MR/T046732/1). M.P., G.B., B.R., M.G. and H.E. acknowledge funding from the Leicester Institute for Advanced Studies through the Migration, Mobilities and Citizenship research network. C.A.O. is a member of the Scottish Government Expert Reference Group on COVID-19 and Ethnicity.

References

- 1.Khunti K., Singh A.K., Pareek M., Hanif W. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2020. Is ethnicity linked to incidence or outcomes of covid-19? [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khunti K., Pareek M. BMJ Opinion; 2020. Covid-19 in ethnic minority groups: where do we go following PHE's report? [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan D., Sze S., Minhas J.S. The impact of ethnicity on clinical outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020:100404. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pareek M., Bangash M.N., Pareek N. Ethnicity and COVID-19: an urgent public health research priority. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1421–1422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30922-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niedzwiedz C.L., O'Donnell C.A., Jani B.D. Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection: prospective cohort study using UK Biobank. BMC Med. 2020;18:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01640-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treweek S., Forouhi N.G., Narayan K.V., Khunti K. COVID-19 and ethnicity: who will research results apply to? Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31380-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19. Public Health England; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Response to the ‘Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19’ report. 2020. https://cdn-cms.f-static.net/uploads/905961/normal_5ee1390b002e5.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyond the data: understanding the impact of COVID-19 on BAME groups. Public Health England; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhopal R. BMJ Opinion; 2020. Delaying part of PHE's report on covid-19 and ethnic minorities turned a potential triumph into a PR disaster. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orcutt M., Patel P., Burns R. Global call to action for inclusion of migrants and refugees in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1482–1483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30971-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armitage R., Nellums L. Whistleblowing and patient safety during COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100425. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eborall H., Wobi F., Ellis K. Integrated screening of migrants for multiple infectious diseases: qualitative study of a city-wide programme. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21:100315. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López L., Green A.R., Tan-McGrory A., King R.S., Betancourt J.R. Bridging the digital divide in health care: the role of health information technology in addressing racial and ethnic disparities. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(10):437–445. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nihr I. Eastleigh: INVOLVE; 2012. Briefing notes for researchers: public involvment in NHS, public health, and social care research. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marston C., Renedo A., Miles S. Community participation is crucial in a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1676–1678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31054-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Involve N. INVOLVE Eastleigh; 2016. What is public involvement in research. [Google Scholar]