Abstract

Objective

The aim of this rapid scoping review, for which only studies from the general population were considered, was to describe the extent of existing research on HL in the context of previous coronavirus outbreaks (SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2).

Methods

We searched major databases and included publications of quantitative and qualitative studies in English and German on any type of research on the functional, critical and communicative domains of HL conducted in the context of the three outbreaks in the general population. We extracted and tabulated relevant data and narratively reported where and when the study was conducted, the design and method used, and how HL was measured.

Results

72 studies were included. Three investigated HL or explicitly referred to the concept of HL, 14 were guided by health behaviour theory. We did not find any study designed to develop or psychometrically evaluate pandemic/epidemic HL instruments, or relate pandemic/epidemic or general HL to a pandemic/epidemic outcome, or any controlled intervention study. Type of assessment of the domains of HL varied widely.

Conclusion

Theory-driven observational studies and interventions, examining whether pandemic-related HL can be improved are needed.

Practice implications

The development and validation of instruments that measure pandemic-related HL is desirable.

Keywords: Health literacy, Pandemic, Epidemic, Coronavirus, Scoping review

1. Introduction

In late 2019 an outbreak of a new viral disease occurred in Wuhan, China and later spread to almost all countries of the world [1]. It is caused by a novel beta coronavirus, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome – Coronavirus – 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes Coronavirus Disease (COVID) – 19) [2]. The clinical epidemiology of COVID-19 is currently being investigated intensely [3]. Course of disease may be very mild, asymptomatic to very severe with respiratory and systemic damage and requiring mechanical ventilation [4]. Responses of governments to the COVID-19 pandemic have been multi-faceted including outbreak management (suppression versus mitigation), provision of adequate clinical treatment facilities for severe cases and measures to alleviate the economic and psychosocial impact of the pandemic and the measures taken to manage it [2]. Public health measures implemented in many countries across the globe encompass contact restrictions and physical distancing, hygiene rules (i.e. frequent and thorough handwashing or disinfection), mask wearing, eye protection and recommendations about how to sneeze and cough [3,5]. Some of these measures, particularly contact restrictions, have been law enforced in many countries [6]. Relaxing regulations and re-organising social life requires people to voluntarily adhere to the named measures in order to avoid exponential growth of SARS-CoV-2 to reoccur. Further, people who contract SARS-CoV-2 need to know when and how to seek health care and/or be tested. Those who suffer from severe COVID-19 and survive will have to seek health care to mitigate the potentially long-lasting physical and psychological sequelae such as kidney damage [7] or post-traumatic stress disorder [8]. In all these and other different scenarios, the concept of health literacy (HL) becomes a vital public health concept that is essential to counterpart on the individual level the social restrictions enforced by law. When restrictions are gradually lifted, the role of individual level HL increases in order to prevent the resumption of these restriction, should infection numbers surge again. The currently prevailing integrated HL notion “entails the motivation, knowledge and competencies to access, understand, appraise and apply health information in order to make judgements and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life throughout the course of life” [9] and is promoted by WHO (World Health Organisation) Europe [10]. While other notions refer, for instance to HL being the result of health education and distinguishes the distinct concepts of functional, critical and communicative HL [11] the aforementioned HL notion was arrived at by a systematic review and an integration of medical and public health views of HL [9].

In other words, what is necessary beyond governmental regulations and policy, is an increase in the levels of COVID-19 related health literacy [12,13]. We not only need to monitor the pandemic’s epidemiology during the course of the pandemic including the creation of herd immunity but also HL and health behavioural responses related to the pandemic in the population [13]. HL is considered a major determinant of a person’s health [14,15], a factor that contributes to health inequalities [14], and a person's health behaviour, for instance, healthy diet adherence or non-smoking [15] and health care utilisation [16]. There is evidence that lower HL is consistently associated with mortality [16] or lower self-rated health status [17].

Research suggests that adequate HL may not be as prevalent among populations as might be necessary in order to navigate the increasingly complex healthcare landscape [15,16,18]. Synthesised evidence suggests a relationship between levels of HL and infectious disease prevention in non-pandemic contexts [19]. Inadequate HL was found to be associated with reduced adoption of protective behaviours such as vaccination uptake and poor understanding of antibiotics [19]. Large research gaps were found in relation to infectious diseases with a high clinical and societal impact, such as tuberculosis and malaria [19]. For instance, it was emphasised that critical HL, which focuses on supporting effective political and social action, was not considered in any of the reviewed studies [19]. The strengths of this relationship may be exponentially higher under pandemic circumstances, but no synthesised information on this topic appears to exist to date. Further, the importance of individual HL in pandemic control has been emphasised more urgently [12,13].

Therefore, the aim of this rapid scoping review, for which only studies from the general population were considered, was to describe the extent of existing research on HL in the context of previous coronavirus outbreaks (SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2). The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared only SARS-CoV-2 a pandemic [1] while MERS-CoV [20] and SARS-CoV-1 [21] remained epidemics. Facets of HL that were of particular interest were: type of assessment of HL (theory-based versus proxy assessment; validated instrument versus ad hoc assessment), interventions aiming to improve HL during outbreak situations, or HL surveillance during outbreak.

2. Method

2.1. Overview

This scoping review was performed according to the methodological framework as outlined by Khalil et al. [22]. Their guidelines regarding scoping reviews build on the work of Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage scoping review framework [23], complemented with the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology [24], in order to (1) identify the research questions, (2) identify relevant studies, (3) select studies, (4) chart the data, and (5) collate and summarise the data. A scoping review’s objective is to identify the nature and extent of the existing evidence. Unlike other types of review, it does not endeavour to systematically evaluate the quality of available research, but rather seeks to identify the contribution of existing literature to an area of interest [25]. Our methodology was also guided by the rapid review approach which inevitably uses less rigor as is required by a traditional systematic review due to the need for production within a short time-frame using limited resources [26]. The protocol for this rapid review was registered at OSFREGISTRIES on 06/04/2020 [27].

2.2. Search strategy, selection criteria, extraction strategy and data analysis

Two authors (UM, NE) ran the search strategy on PubMed (MEDLINE®) and PsycINFO® on 20th April 2020. Citations were downloaded to Citavi (Swiss Academic Software). We included publications in English and German of quantitative and qualitative studies. The same authors evaluated titles and abstracts excluding any irrelevant ones. Full texts of the remaining citations were obtained, and two authors (UM, NE) reviewed these, excluding any, which did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, reference lists of remaining papers were hand-searched for additional relevant studies. We then compared results from full text screening; there were only minor discrepancies, which were resolved through discussion with the whole team. Data extraction was carried out by five authors (UM, NE, JT, CT, JL) in independent pairs of two. Consensus was achieved through discussion and arbitration within the team. The search strategy was informed by HL theory (derivation of search terms) and is displayed in appendix 1. Inclusion criteria were:

We included reports on any type of research on the functional, critical and communicative domains of HL [11] conducted in the context of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV in the general population. This was a rational decision as an initial search using HL as the chief search term in conjunction with the aforementioned coronavirus outbreaks resulted in very few hits. We used the following definitions / concepts of functional, communicative and critical HL: Functional HL is broadly compatible with the narrow definition of ‘health literacy’ which can be considered to consist of health-related knowledge, risk perceptions, attitudes, motivation, behavioural intentions, personal skills, or self-efficacy [11]. Communicative HL means to be able …’to derive meaning from different forms of communication’…, while the ability to critically analyse information is referred to as critical HL [11].

The following data were extracted from the included studies: authors, publication year, country of study, type of epidemic or pandemic outbreak (SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV), participants (including sample size), design, method, and instruments, and measured constructs including how they were measured (only if applicable e.g. not in qualitative studies). Findings were synthesized quantitatively and narratively and reporting followed the guidelines as proposed in PRISMA-ScR [28]. A critical appraisal of the quality of the included studies was not within the scope of this review. We do however, comment on major methodological issues regarding the studies.

There was no funding source for this study.

3. Results

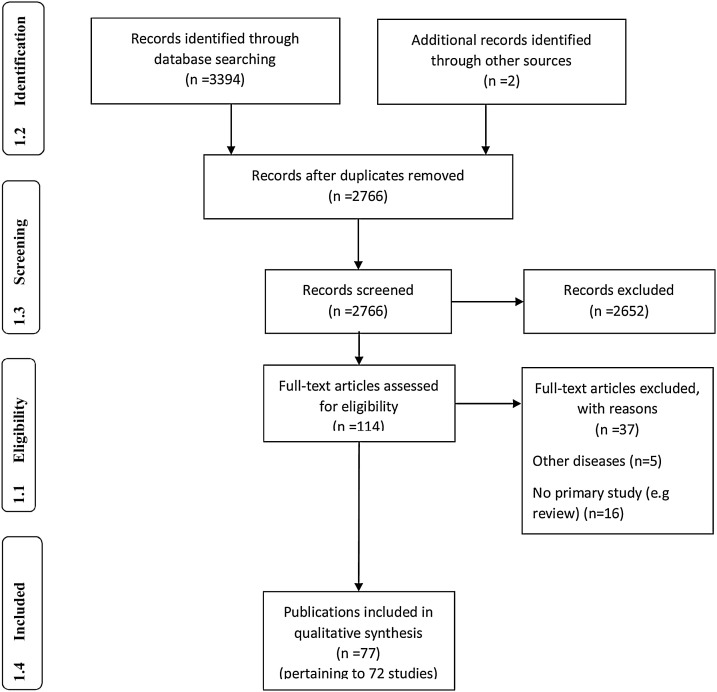

The search in PubMed (MEDLINE®) and PsycInfo® yielded 3394 references, two were obtained from colleagues [29,30], leading to 2766 references after removal of duplicates. Title and abstract screening resulted in exclusion of 2652 articles. Full-texts of the remaining 114 references were assessed for eligibility leading to inclusion of 77 publications pertaining to 72 studies. Details of the selection stages are provided in Fig. 1 . SARS-CoV-2 was investigated in 10, MERS-CoV in 26 and SARS-CoV-1 in 36 studies. Only three studies investigated HL or explicitly referred to the concept of HL [30,32]. 14 studies were conducted in the context of health behaviour theory, seven of another theory (Appendix 2). All studies, while mainly not explicitly investigating HL, measured one or more components of HL (Appendix 2). Most studies were observational or short longitudinal (58 cross-sectional, eight pre-post) and six qualitative. All SARS-CoV-2 studies were conducted during, of the MERS-CoV studies 27 during, one during (first wave), eight after, of the MERS-CoV studies 24 during, one after and one both during and after the pandemic/epidemic outbreak. 66 studies used questionnaires, two used focus group discussions, four others used qualitative methods (e.g. interviews) for data collection. 49 studies investigated convenience or opportunity samples and 23 representative samples drawn from general populations. Sample size ranged from 19 to 222.599 participants.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram [28].

3.1. Functional, critical, communicative HL and individual behaviour in quantitative studies

Within the nine quantitative SARS-CoV-2 studies, knowledge was measured in seven, attitude in seven, risk perceptions in four, self-efficacy in three, critical HL in five, communicative HL in three, Health-information seeking behaviour (HISB) in two, and behavioural aspects in four studies. Only one study [29] measured functional, critical and communicative HL as well as a behavioural outcome. All others assessed only some aspects of HL. While seven studies reported on knowledge, most studies asked only about knowledge of symptoms. No study undertook a comprehensive assessment covering a broad range of SARS-CoV-2 related knowledge. Within the knowledge domain, symptoms were most often assessed. (Table 1 ). Wearing a mask was the most frequently assessed behaviour (Table 1).

Table 1.

Health literacy (HL) and behavioural dimensions assessment in quantitative studies.

| SARS-CoV-2 9 studies |

SARS-CoV-1 31 studies |

MERS-CoV 26 studies |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional HL | Knowledge dimension |

7 [29,32,36,37,58,59,60,61,62] | 25 [33,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,78,79,80,81,82,84,85,86,87,88,91,92,94] | 21 [34,38,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,111,112,113,114,115,116] |

| Awareness | 2 [60,61] | 3 [66,85,91] | 9 [99,100,102,103,106,107,108,111,112,115] | |

| Nature of disease |

2 [29,61] | 10 [33,63,64,65,66,68,73,87,91,94] | 9 [38,97,98,102,104,107,112,113,116] | |

| Transmission mode |

4 [29,36,37,60,62] | 18 [63,64,65,67,68,72,73,74,75,76,78,79,80,81,82,84,85,86,87] | 18 [34,38,95,96,97,98,101,102,103,104,106,107,108,111,112,113,115,116] | |

| Symptoms | 6 [29,32,58,59,60,61,62] | 8 [33,63,64,68,72,87,91,94] | 13 [34,38,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,104,112,113,116] | |

| Course | 2 [29,32] | 4 [68,75,76,91] | 7 [38,96,97,98,103,113,116] | |

| Treatment | 2 [29,36,37] | 5 [64,65,72,76,91] | 8 [34,38,96,97,102,111,113,116] | |

| Risk groups | 1 [58] | 0 | 3 [38,96,102] | |

| Fatality rate/# infections | 2 [36,37,58,59] | 1 [66] | 3 [38,105,113] | |

| Measures of infection control | 0 | 1 [85] | 1 [102] | |

| Prevention | 4 [32,58,59,61,62] | 3 [72,73,76] | 8 [38,95,96,98,103,104,112,116] | |

| Attitude | 7 [29,36,37,58,59,60,61,62] | 28 [33,63,64,65,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,86,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] | 17 [34,35,38,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,103,104,105,106,107,110,114,116] | |

| Risk perception | 4 [29,36,37,58,59] | 20 [33,66,67,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,83,84,86,88,89,91,92,94] | 18 [34,35,38,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,106,107,112,113,116,118] | |

| Self-efficacy/skills/preparedness | 3 [29,30,32] | 8 [33,66,68,83,88,89,92,94] | 3 [34,35,118] | |

| Critical HL | 5 [29,30,32,36,37,62] | 11 [33,63,66,72,73,74,83,84,88,91,94] | 4 [35,110,115,116] | |

| Communicative HL | 3 [29,30,60] | 12 [33,63,64,65,66,67,73,74,75,83,85,91] | 17 [34,95,98,99,100,101,102,104,105,106,107,109,111,112,113,115,117,118] | |

| HISB | 2 [29,32] | 4 [63,65,68,91] | 2 [34,109] | |

| Behaviour/practices | 4 [29,32,36,37,62] | 18 [63,65,66,67,68,73,75,77,78,79,80,81,84,86,87,88,89,91,92] | 10 [34,38,97,99,100,101,108,109,110,116,117] | |

| Wash hands | 1 [36,37] | 13 [66,67,68,75,78,79,80,81,84,86,87,89,91,92] | 9 [34,38,97,99,100,101,108,109,110,117] | |

| Wear mask | 3 [29,36,37,62] | 15 [66,67,68,75,77,78,79,80,81,84,86,87,88,89,91,92] | 7 [34,38,97,99,100,101,108,110] | |

| Avoid touching face | 0 | 3 [78,79,80,81] | 4 [38,97,101,110] | |

| Cough/Sneeze hygiene | 1 [36,37] | 7 [67,78,79,80,81,84,86,92] | 6 [34,38,97,99,100,101,110] | |

| Correct tissue disposal | 0 | 0 | 3 [38,97,99,100] | |

| Self-impose quarantine if experiencing symptoms | 0 | 1 [77] | 2 [38,97] | |

| Consult doctor if experiencing symptoms | 0 | 5 [65,68,77,89,91] | 1 [38] | |

| Avoid sharing personal items | 1 [36,37] | 6 [67,78,79,80,81,84,86] | 0 | |

| Avoid travelling | 0 | 3 [63,65,91] | 0 | |

| Avoid travelling to high-risk areas | 0 | 2 [73,91] | 0 | |

| Avoid public transport | 0 | 4 [66,75,77,91] | 0 | |

| Avoid crowded places | 2 [29,62] | 5 [65,66,73,75,91] | 1 [110] | |

| Avoid eating out | 0 | 3 [66,68,91] | 0 | |

| Avoid people with flu-like symptoms | 0 | 2 [63,68] | 2 [101,110] | |

| General personal self-care (pro-active HB) | 0 | 6 [66,68,87,89,91,92] | 0 | |

| Home hygiene | 0 | 7 [65,66,68,75,87,89,92] | 1 [101] | |

| Avoid camel exposure and products | 0 | 0 | 3 [99,100,101,108] | |

| Other behavioural responses | 2 [29,32] | 7 [65,67,68,75,86,87,91] | 3 [108,109,110] | |

HB: health behaviour; HISB: health-information seeking behaviour; note: cited references do not correspond to number of studies but publications.

31 quantitative studies were conducted in the context of SARS-CoV-1. 25 measured knowledge, 28 attitude, 20 risk perception, eight SE, 11 critical HL, 12 communicative HL, and 18 behaviour. One study [33] reported all six HL aspects, the others one to five aspects. Within knowledge, transmission mode was most often measured. Although 25 studies reported knowledge assessment, most studies did not comprehensively assess knowledge (Table 1). Handwashing was the most frequently measured behaviour (Table 1).

Of the 26 quantitative MERS-CoV studies 21 measured knowledge, 17 attitude, 18 risk perceptions, 3 SE, 4 critical HL, 17 communicative HL, and 10 behaviour. Two studies assessed five of the six HL aspects [34,35], the remainder one to four. Within knowledge, transmission mode was most often assessed. Again, most studies did not comprehensively assess knowledge. Handwashing was the most frequently assessed behaviour (Table 1).

The reported measured depth within the domains of HL varied widely among the studies (results not shown). For instance, the number of knowledge components ranged from one to at least eight.

3.2. Health-information seeking behaviour (HISB) in quantitative studies

HISB was measured in two (SARS-CoV-2), four (SARS-CoV-1), two (MERS-CoV) quantitative studies.

3.3. Pandemic/Epidemic HL measurement and relationship to pandemic/epidemic outcome (quantitative and qualitative studies)

Our search failed to come across any studies designed to develop or psychometrically evaluate pandemic/epidemic HL instruments or relate pandemic/epidemic or general HL to a pandemic/epidemic outcome.

3.4. Other aspects of HL measurement in pandemic/epidemic contexts (quantitative and qualitative studies)

The number of items per HL aspect varied widely (data not shown), hardly any study reported on psychometric properties, two studies from three publications [31,36,37] were the notable exception (Appendix 3) and a clear distinction between knowledge, attitude, or risk perceptions was sometimes absent. For instance, perceived vulnerability was reported as an attitude [38].

3.5. Qualitative studies

Six qualitative studies explored domains of HL in the context of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1, and MERS-CoV. One focus group study [39] reported low risk perceptions and a lack of seeking relevant health information in relation to SARS-CoV-2. One interview study [40] and one focus group study [41] explored risk perceptions and preventive behaviour in relation to SARS-CoV-1, another interview study [42] explored individual experiences during quarantine. One interview study reported low knowledge about SARS-CoV-1 and its prevention [43]. Another interview study in the context of SARS-CoV-1 concluded that attitudes towards mask wearing had substantially changed in the post-SARS-CoV-1 period [44].

4. Discussion

While individual HL is recognised as an increasingly important construct in public health [45], it is of note that only three studies emerged from our extensive search, which explicitly referred to the construct of HL in the context of any of the three coronavirus outbreaks. One used the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), a test measuring nutrition label information processing ability [32], another study [31] administered a short form of the HLS-EU-Q47, an HL instrument rooted in testable theory [46] and the third [30] study used a version of the HLS-EU-Q47 adapted to SARS-CoV-2. However, the latter provided no evidence on the psychometric properties of the adapted instrument. Hence, at present there seems to be no tested instrument designed to measure coronavirus pandemic-related HL. There is, however, one HL instrument assessing print and multimedia literacy in respect to respiratory diseases [47].

Most of the other included studies were not theory-based. It is important to highlight that these studies did not purport to measure HL, but were included in this review because the search strategy was based on a pragmatic application of suggested HL components within domains [11,48]. Of those that were theory-driven, the majority employed health-behaviour theory as conceptualised by social cognition models. There is substantial overlap between socio-cognitive predictors of health behaviour and HL. For instance, attitude and self-efficacy (defined as behavioural control) are part of the theory of planned behaviour [49], risk perceptions part of the health belief model [50] or knowledge part of protection motivation theory [51]. Theory-based research allows the formulation of testable a priori hypotheses, and if necessary revision of the theory. Nonetheless, the measures obtained from those studies lacking an explicit theoretical foundation can be considered proxies of HL because they constitute or at least contribute to one or more HL domains.

While there appears to be no evidence linking validly measured (epidemic or pandemic) HL to coronavirus outbreak/pandemic outcomes there is evidence that HL can be linked to other epidemic outbreaks, e.g. the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic outbreak in West Africa resulted among other factors from low health literacy [52]. A Center for Disease Control and Prevention campaign, with input from partners, helped increase HL [53]. HL has also been shown to be associated with health and health behaviour in general. Hence, one would expect that this association would hold in coronavirus outbreak situations.

Communicative HL included the measurement of access to different sources of information. Whether this had anything to do with better decisions about health in relation to any of the three outbreaks, remained unclear. Knowledge items were generally devised by the authors, and very few reported to have items checked against guidelines. This and the lack of an objective standard for cut-offs make knowledge assessment arbitrary as it cannot be established whether knowledge items reflect current and correct evidenced knowledge. Similarly, while risk perceptions generally pertain to perceptions of vulnerability/susceptibility to and severity of a disease, they were not always measured accordingly or sometimes subsumed under the term attitudes or knowledge.

We also observed very little evidence about the psychometric properties of instruments used to measure socio-cognitive variables such as attitude, risk perceptions, and self-efficacy. It is desirable to know whether measures are reliable and valid, and sensitive to change if the aim is to reflect the effects of health literacy interventions by e.g. education (responsiveness).

Even if knowledge, attitudinal constructs, risk perceptions or self-efficacy were composed in a clear-cut and unequivocal way and psychometrically sound, uncertainty as to whether HL in its broader definition [9,54] as a composite/compound construct was measured, would still prevail. HL was proposed to be a latent construct [46] thus indicators for its measurement are necessary. There is the need for the development of adequate measurement models.

The present review cannot ascertain, whether established instruments such as TOFHLA (Test of Functional Health Literacy) [55], or the broader dimension based instruments, for instance the HLQ (Health Literacy Questionnaire) [56] could be used to predict a pattern of association between HL and epidemic or pandemic outcomes (and antecedents such as favourable behaviours and practices), because no such investigations appear to have been carried out, yet. The study [31] that used a short form of the HLS-EU-Q did not investigate the relationship between HL and pandemic outcome/preventive behaviour but coping responses to the outbreak (depression, quality of life). Okan et al. [30] reported individuals’ subjective perceptions about how well they could access, understand, appraise and apply information in the SARS-CoV-2 context but did not test the actual level of what these skills pertain to and whether they are related to better/more favourable behaviour/practices.

Further, it also not possible to state at present whether pandemic outbreaks require a specific HL instrument, that is able to explain variance in relevant behaviour and practices over and above that of general instruments (i.e. latent trait/construct measured by discrete manifest cognitive antecedents of behaviour).

In this rapid review, the systematic search was restricted to two major data bases and no grey literature search was conducted. Also, as this review was conducted as a scoping review, we did not look at the strengths of any reported associations between HL aspects and behavioural aspects. Further, it is beyond the scope of this review to assess the quality of the reviewed studies according to standard guidelines for observational studies.

5. Conclusion

At present HL in the context of coronavirus outbreaks is at an early stage to inform public health/educational strategies aimed at improving the public’s HL in order to contain the spread of pandemics. One study [29] appears to be able to shed light on the question of whether HL related aspects change over the course of the pandemic as its survey is conducted in weekly intervals.

6. Practice implications

We recommend future research be guided by theory from HL research [9,48] in the much needed work on HL in pandemic outbreak situations. Consequently, assessment of HL should be based on the ability to access, understand, critically appraise and eventually apply information to make better choices about one’s health in pandemic outbreak situations when viewed as a set of meta-cognitive skills or a latent trait [46]. Nevertheless, operationalisations at the manifest level, for example, knowledge, or attitudes (which influence critical appraisal) need to be considered, as latent constructs cannot be directly measured. Nevertheless, in the interim, public health communication could benefit from what is generally known from HL research. Health information should be clear so that all members of the public can access needed health information for routine and critical decisions [57].

Beside theory-driven observational studies, we also need interventions, examining whether coronavirus pandemic-related HL can be improved. In addition, research should also attempt to develop HL instruments that measure coronavirus pandemic-related HL and test the reliability, validity and responsiveness to change. The latter is of particular importance, if we want to be able to examine change during the stages of a pandemic.

Contributors

CA conceived the study. CA & UM developed the protocol. UM, NE, CT, JT, JL, CA, MLD & EMB contributed to the search strategy, screened the search results, extracted data, and interpreted the findings. UM, CA & EMB wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the paper for important intellectual content.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

There was no funding source for this study.

Appendix 1 search strategy

PubMed (MEDLINE®)

(health literacy[MeSH Terms] OR (health[Title/Abstract] AND competence[Title/Abstract]) OR literacy[Title/Abstract] OR knowledge[Title/Abstract] OR attitude[Title/Abstract] OR motivation* OR intention* OR skills OR self-efficacy[MeSH] OR organisation*[Title/Abstract] OR community[Title/Abstract]) AND ((2019-nCoV OR 2019nCoV OR COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR ((wuhan AND coronavirus) AND 2019/12[PDAT]:2030[PDAT])) OR ("Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome"[MeSH Terms] OR SARS) OR ("middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus"[MeSH Terms] OR MERS)) NOT (animals [mh] NOT humans [mh])

PsycINFO®

(health literacy or health education or health knowledge or health information or health understanding) AND (pandemic* or epidemic* or outbreak or covid-19 or coronavirus OR 2019-ncov or sars OR sars-cov-2 OR mers) NOT (hiv or aids or acquired human immunodeficiency syndrome or human immunodeficiency virus)

Appendix 2 Summary of study characteristics

| Study ID | Country | n | When conducted | Design | Method | Sampling method |

HL specific | Other theory guided | Type of theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | |||||||||

| Betsch 2020 [29] | GER | 1000 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Geldsetzer 2020a 2020b [58,59] | UK, USA | 5974 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Khan 2020 [60] | PAK | 302 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Ma 2020 [39] | AUS | 28 | during | qual. | Focus groups | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Nguyen 2020 [31] | VNM | 3974 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | yes | no | n.a. |

| Okan 2020 [30] | GER | 1000 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | yes | no | n.a. |

| Roy 2020 [61] | IND | 662 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Wang 2020a 2020b [36,37] |

CHN | 1738 | during | obs Pp | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Wolf 2020 [32] | USA | 630 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | yes | no | n.a. |

| Zhong 2020 [62] | CHN | 6919 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| SARS-CoV-1 | n.a. | ||||||||

| Bener 2004 [63] | QAT | 1386 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Bergeron 2005 [64] | CAN | 300 | post | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Blendon 2004 [65] | CAN, USA | 1500 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Brug 2004 [66] | NLD | 373 | during | obs cross | Quest. | unclear | no | no | n.a. |

| Cava 2005 [42] | CAN | 21 | during | qual. | Interview | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Chan 2007 [67] | HKG | 296/122 | during | obs Pp Intervention | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Cheng 2006 [68] | CHN, SGP, HKG, CAN | 300 | during | obs Pp | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Chuo 2014 [69] | TWN | 294/88 | partly during (first survey wave) | obs Pp | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Des Jarlais 2006/2005 [70,71] | USA | 928 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | yes | OM |

| Deurenberg-Yap 2005 [72] | SGP | 853 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | yes | OM |

| Hazreen 2005 [73] | MYS | 201 house holds | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Ishizaki 2004 [74] | JPN | 821 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Jiang 2009 [41] | UK, NLD | 164 | post | Qual. | Focus groups | Conv. | no | yes | GT |

| Lau 2003 [75] | HKG | 1397 | during | obs Pp | Quest. | repr. | no | yes | THB |

| Lau 2005 [76] | HKG | 820 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Lau 2004 [77] | HKG | 820 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Leung 2003 [78] | HKG | 1115 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Leung 2005 [79] | HKG | 4481 | post | obs Pp | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Leung 2004/2009 [80,81] | HKG, SGP | 1906 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Lim 2003 [82] | SGP | 101 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Peng 2010 [83] | TWN | 1278 | post | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Quah 2004 [84] | SGP | 1201 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Seng 2004 [85] | SGP | 593 | post | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Siu 2016 [44] | HKG | 40 | post | qual. | interview | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| So 2004 [86] | HKG | 163/112 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Tan 2004 [87] | CHN | 1807 | during | obs retros | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Tang 2003 [88] | HKG | 2331 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Tang 2005 [89] | HKG | 354 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Tracy 2009 [90] | CHN | 500 | post | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | PHM |

| Tse 2003 [43] | HKG | 40 | during | qual. | interview | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Vartti 2009 [91] | NLD, FIN | 681 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | MISR |

| Voeten 2009 [33] | UK, NLD | 300 | post | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Wills 2008 [40] | CAN | 19 | during | qual. | interview | Conv. | no | no | |

| Wong 2005 [92] | HKG | 230 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | yes | THB |

| Yip 2007 [93] | HKG | 463 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | |

| Zwart 2009 [94] | DNK,NLD, UK, ESP, POL, SGP, CHN, HKG | 3436 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | yes | THB |

| MERS-CoV | |||||||||

| Al-Hazmi 2018 [95] | SAU | 1109 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Al-Mohaissen 2017 [96] | SAU | 1541 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Alhomoud 2017 [38] | SAU | 292/257 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Almutairi 2015 [97] | SAU | 1147 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Alotaibi 2017 [98] | SAU | 417 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Alqahtani 2016a/2016b [99,100] | AUS | 421 | during | obs Pp | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Alqahtani 2017 [101] | SAU, KWT, UAE, QAT, BHR, OM | 1812 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Althobaity 2017 [102] | SAU | 2120 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Ashok 2016 [103] | SAU | 404 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Bawazir 2018 [104] | SAU | 676 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Gautret 2013 [105] | FRA | 360 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Hoda 2016 [106] | SAU | 854/658 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | yes | CPM |

| Hou 2018 [107] | SGP | 2969 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | THB |

| Jang 2018 [34] | KOR | 1036 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | yes | THB |

| Kamau 2019 [108] | KEN | 22 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Kim 2018 [35] | KOR | 814 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | yes | VBM |

| Lee 2019 [109] | KOR | 855 | post | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Lee 2016 [110] | KOR | 6739 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Lin 2017 [111] | USA | 627 | both | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Migault 2019 [112] | FRA | 82 | during | obs Pp Intervention | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Nooh 2010 [113] | SAU | 384 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Sahin 2015 [114] | TUR | 381 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Tashani 2014 [115] | AUS | 119 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Yang 2017 [116] | KOR | 1470 | during | obs cross | Quest. | Conv. | no | no | n.a. |

| Yang 2019 [117] | KOR | 222,599 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

| Yoo 2016 [118] | KOR | 1000 | during | obs cross | Quest. | repr. | no | no | n.a. |

CPM: communication-persuasion model; Conv.: convenience or opportunity sample; GT: grounded theory; HL specific: Do the authors specifically refer to health literacy and/or a health literacy concept?; MISR: Model of Illness Perceptions and Self-Regulation; n.a.: not applicable; obs cross: observational cross-sectional; obs Pp: observational pre-post; OM: other model; THB: Theory of health behaviour; PHM: Public health model; repr.: representative; VBM: value-based model; Quest.: Questionnaire.

Appendix 3 Health literacy (HL) dimensions and their components and behaviour/practice measured in studies

| Health Literacy | HISB | Behaviour/practice | Instrument validated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional | Critical | Commu-nicative | |||||||

| Know-ledge | Atti-tude* | Risk perc-eption† | Skills‡ | ||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | |||||||||

| Betsch 2020 [119] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Geldsetzer 2020a 2020b [58,59] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Khan 2020 [60] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Ma 2020 [39] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.a. |

| Nguyen 2020 [31] | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | partly |

| Okan 2020 [120] | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Roy 2020 [61] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Wang 2020a 2020b [36,37] |

25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | partly |

| Wolf 2020 [32] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Zhong 2020 [62] | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| SARS-1 | |||||||||

| Bener 2004 [63] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Bergeron 2005 [64] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Blendon 2004 [65] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Brug 2004 [66] | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Cava 2005 [42] | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | |

| Chan 2007 [67] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Cheng 2006 [68] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Chuo 2014 [69] | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Des Jarlais 2006/2005 [70,71] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Deurenberg-Yap 2005 [72] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Hazreen 2005 [73] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Ishizaki 2004 [74] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Jiang 2009 [41] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.a. |

| Lau 2003 [75] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Lau 2005 [76] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Lau 2004 [77] | f0a1; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Leung 2003 [78] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Leung 2005 [79] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | f02d;○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Leung 2004/2009 [80,81] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Lim 2003 [82] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Peng 2010 [83] | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Quah 2004 [84] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Seng 2004 [85] | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Siu 2016 [44] | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.a. |

| So 2004 [86] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Tan 2004 [87] | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Tang 2003 [88] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Tang 2005 [89] | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Tracy 2009 [90] | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Tse 2003 [43] | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.a. |

| Vartti 2009 [91] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Voeten 2009 [33] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Wills 2008 [40] | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.a. |

| Wong 2005 [92] | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Yip 2007 [93] | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Zwart 2009 [94] | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| MERS | |||||||||

| Al-Hazmi 2018 [95] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Al-Mohaissen 2017 [96] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Alhomoud 2017 [38] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Almutairi 2015 [97] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Alotaibi 2017 [121] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Alqahtani 2016a/2016b [99,100] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Alqahtani 2017 [101] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Althobaity 2017 [102] | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Ashok 2016 [103] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Bawazir 2018 [104] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Gautret 2013 [105] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Hoda 2016 [122] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Hou 2018 [107] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Jang 2018 [34] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Kamau 2019 [108] | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Kim 2018 [35] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Lee 2019 [109] | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Lee 2016 [110] | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Lin 2017 [111] | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Migault 2019 [112] | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Nooh 2010 [113] | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Sahin 2015 [114] | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Tashani 2014 [115] | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

| Yang 2017 [116] | 25CF; | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Yang 2019 [117] | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | n.r. |

| Yoo 2016 [118] | ○ | ○ | 25CF; | 25CF; | ○ | 25CF; | ○ | ○ | n.r. |

f06c; yes; f0a1; no; n.a.: not applicable; HISB: health information seeking behaviour; n.r.: not reported; * includes related concepts (e.g. outcome expectancies, response efficacy); † perceived vulnerability and/or severity; ‡ Skills (self-efficacy, skills, preparedness).

References

- 1.World Health Organisation . 2020. Novel Coronavirus(2019-nCoV)SITUATION REPORT-121 JANUARY.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4 (Accessed 20 May 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilder-Smith A., Chiew C.J., Lee V.J. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:e102–e107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai C.-C., Shih T.-P., Ko W.-C., Tang H.-J., Hsueh P.-R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu D.K., Akl E.A., Duda S., Solo K., Yaacoub S., Schünemann H.J. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattioli A.V., Ballerini Puviani M., Nasi M., Farinetti A. COVID-19 pandemic: the effects of quarantine on cardiovascular risk. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020;74:852–855. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0646-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng Y., Luo R., Wang K., Zhang M., Wang Z., Dong L., Li J., Yao Y., Ge S., Xu G. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97:829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Röhr S., Müller F., Jung F., Apfelbacher C., Seidler A., Riedel-Heller S.G. Psychosocial impact of quarantine measures during serious coronavirus outbreaks: a rapid review. Psychiatr. Prax. 2020;47:179–189. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorensen K., van den Broucke S., Fullam J., Doyle G., Pelikan J., Slonska Z., Brand H. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kickbusch I. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. Health Literacy: The Solid Facts. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000;15:259–267. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abel T., McQueen D. Critical health literacy and the COVID-19 crisis. Health Promot. Int. 2020 doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaa040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paakkari L., Okan O. COVID-19: health literacy is an underestimated problem. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e249–e250. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rikard R.V., Thompson M.S., McKinney J., Beauchamp A. Examining health literacy disparities in the United States: a third look at the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) BMC Public Health. 2016;16:975. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3621-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Wagner C., Knight K., Steptoe A., Wardle J. Functional health literacy and health-promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2007;61:1086–1090. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eichler K., Wieser S., Brugger U. The costs of limited health literacy: a systematic review. Int. J. Public Health. 2009;54:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0058-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Heide I., Wang J., Droomers M., Spreeuwenberg P., Rademakers J., Uiters E. The relationship between health, education, and health literacy: results from the dutch adult literacy and life skills survey. J. Health Commun. 2013;18:172–184. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paasche-Orlow M.K., Parker R.M., Gazmararian J.A., Nielsen-Bohlman L.T., Rudd R.R. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005;20:175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castro-Sánchez E., Chang P.W.S., Vila-Candel R., Escobedo A.A., Holmes A.H. Health literacy and infectious diseases: why does it matter? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;43:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organisation, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ (accessed 20 May 2020).

- 21.World Health Organisation, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome). https://www.who.int/ith/diseases/sars/en/ (accessed 19 May 2020).

- 22.Khalil H., Peters M., Godfrey C.M., McInerney P., Soares C.B., Parker D. An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews, worldviews evid. Based Nurs. 2016;13:118–123. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters M.D.J., Godfrey C., McInerney P., Munn Z., Tricco A.C., Khalil H. In: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. Aromataris E M.Z., editor. JBI; 2020. Scoping reviews. (2020 version)Chapter 11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant M.J., Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 2009;26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khangura S., Konnyu K., Cushman R., Grimshaw J., Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst. Rev. 2012;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matterne U., Egger N., Apfelbacher C., Lander J., Bitzer E.M., Dierks M.L. 2020. Health Literacy in the Context of Pandemic and Epidemic (outbreak): Rapid Scoping Review.https://osf.io/sgw76/ (accessed 6 April 2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M.D.J., Horsley T., Weeks L., Hempel S., Akl E.A., Chang C., McGowan J., Stewart L., Hartling L., Aldcroft A., Wilson M.G., Garritty C., Lewin S., Godfrey C.M., Macdonald M.T., Langlois E.V., Soares-Weiser K., Moriarty J., Clifford T., Tuncalp O., Straus S.E. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betsch C., Wieler L., Bosnjak M., et al. 2020. Germany COVID-19 Snapshot MOnitoring (COSMO Germany): Monitoring Knowledge, Risk Perceptions, Preventive Behaviours, and Public Trust in the Current Coronavirus Outbreak in Germany.https://www.psycharchives.org/handle/20.500.12034/2501 (accessed 8 May 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okan O., de Sombre S., Hurrelmann K., Berens E.M., Bauer U., Schaeffer D. 2020. Gesundheitskompetenz Der Bevölkerung Im Umgang Mit Der Coronavirus-pandemie. (accessed 7 May 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen H.C., Nguyen M.H., Do B.N., Tran C.Q., Nguyen T.T.P., Pham K.M., Pham L.V., Tran K.V., Duong T.T., Tran T.V., Duong T.H., Nguyen T.T., Nguyen Q.H., Hoang T.M., Nguyen K.T., Pham T.T.M., Yang S.-H., Chao J.C.-J., van Duong T. People with suspected COVID-19 symptoms were more likely depressed and had lower health-related quality of life: the potential benefit of health literacy. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/jcm9040965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf M.S., Serper M., Opsasnick L., O’Conor R.M., Curtis L.M., Benavente J.Y., Wismer G., Batio S., Eifler M., Zheng P., Russell A., Arvanitis M., Ladner D., Kwasny M., Persell S.D., Rowe T., Linder J.A., Bailey S.C. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to covid-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the U.S. outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voeten Helene A.C.M., de Zwart O., Veldhuijzen I.K., Yuen C., Jiang X., Elam G., Abraham T., Brug J. Sources of information and health beliefs related to SARS and avian influenza among Chinese communities in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, compared to the general population in these countries. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009;16:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s12529-008-9006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang K., Park N. The effects of repetitive information communication through multiple channels on prevention behavior during the 2015 MERS outbreak in South Korea. J. Health Commun. 2018;23:670–678. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1501440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim S., Kim S. Exploring the determinants of perceived risk of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., McIntyre R.S., Choo F.N., Tran B., Ho R., Sharma V.K., Ho C. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alhomoud F., Alhomoud F. "Your health essential for your Hajj": Muslim pilgrims’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) during Hajj season. J. Infect. Chemother. 2017;23:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma T., Heywood A., MacIntyre C.R. Travel health risk perceptions of Chinese international students in Australia - Implications for COVID-19. Infect. Dis. Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wills B.S.H., Morse J.M. Responses of Chinese elderly to the threat of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in a Canadian community. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25:57–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang X., Elam G., Yuen C., Voeten H., de Zwart O., Veldhuijzen I., Brug J. The perceived threat of SARS and its impact on precautionary actions and adverse consequences: a qualitative study among Chinese communities in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009;16:58–67. doi: 10.1007/s12529-008-9005-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cava M.A., Fay K.E., Beanlands H.J., McCay E.A., Wignall R. The experience of quarantine for individuals affected by SARS in Toronto. Public Health Nurs. 2005;22:398–406. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tse M.M.Y., Pun S.P.Y., Benzie I.F.F. Experiencing SARS: perspectives of the elderly residents and health care professionals in a Hong Kong nursing home. Geriatr. Nurs. (Minneap) 2003;24:266–269. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4572(03)00251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siu J.Y.-M. Qualitative study on the shifting sociocultural meanings of the facemask in Hong Kong since the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak: implications for infection control in the post-SARS era. Int. J. Equity Health. 2016;15:73. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0358-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nielsen-Bohlman L., Panzer A.M., Kindig D.A. 2004. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington (DC) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sørensen K., van den Broucke S., Pelikan J.M., Fullam J., Doyle G., Slonska Z., Kondilis B., Stoffels V., Osborne R.H., Brand H. HLS-EU Consortium, Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q) BMC Public Health. 2013;13:948. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun X., Chen J., Shi Y., Zeng Q., Wei N., Xie R., Chang C., Du W. Measuring health literacy regarding infectious respiratory diseases: a new skills-based instrument. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nutbeam D., Kickbusch I. Advancing health literacy: a global challenge for the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000;15:183–184. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.3.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health. 2011;26:1113–1127. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenstock I.M. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA, US: 1990. The Health Belief Model: Explaining Health Behavior Through Expectancies, in: Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogers R.W., Prentice-Dunn S. Plenum Press; New York, NY, US: 1997. Protection Motivation Theory, in: Handbook of Health Behavior Research 1: Personal and Social Determinants; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fowler R.A., Fletcher T., Fischer W.A.2, Lamontagne F., Jacob S., Brett-Major D., Lawler J.V., Jacquerioz F.A., Houlihan C., O’Dempsey T., Ferri M., Adachi T., Lamah M.-C., Bah E.I., Mayet T., Schieffelin J., McLellan S.L., Senga M., Kato Y., Clement C., Mardel S., Bejar De Villar Vallenas, Constanza Rosa, Shindo N., Bausch D. Caring for critically ill patients with ebola virus disease. Perspectives from West Africa. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014;190:733–737. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1514CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bedrosian S.R., Young C.E., Smith L.A., Cox J.D., Manning C., Pechta L., Telfer J.L., Gaines-McCollom M., Harben K., Holmes W., Lubell K.M., McQuiston J.H., Nordlund K., O’Connor J., Reynolds B.S., Schindelar J.A., Shelley G., Daniel K.L. Lessons of risk communication and health promotion - West Africa and United States. MMWR Suppl. 2016;65:68–74. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6503a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pleasant A., Kuruvilla S. A tale of two health literacies: public health and clinical approaches to health literacy. Health Promot. Int. 2008;23:152–159. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parker R.M., Baker D.W., Williams M.V., Nurss J.R. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1995;10:537–541. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Osborne R.H., Batterham R.W., Elsworth G.R., Hawkins M., Buchbinder R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) BMC Public Health. 2013;13:658. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rudd R., Baur C. Health literacy and early insights during a pandemic. J. Commun. Healthc. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1080/17538068.2020.1760622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geldsetzer P. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional online survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-0912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geldsetzer P. Use of rapid online surveys to assess people’s perceptions during infectious disease outbreaks: a cross-sectional survey on COVID-19. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e18790. doi: 10.2196/18790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khan S., Khan M., Maqsood K., Hussain T., Noor-Ul-Huda M. Zeeshan, Is Pakistan prepared for the COVID-19 epidemic? A questionnaire-based survey. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roy D., Tripathy S., Kar S.K., Sharma N., Verma S.K., Kaushal V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51:102083. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhong B.-L., Luo W., Li H.-M., Zhang Q.-Q., Liu X.-G., Li W.-T., Li Y. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:1745–1752. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bener A., Al-Khal A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards SARS. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health. 2004;124:167–170. doi: 10.1177/146642400412400408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bergeron S.L., Sanchez A.L. Media effects on students during SARS outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:732–734. doi: 10.3201/eid1105.040512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blendon R.J., Benson J.M., DesRoches C.M., Raleigh E., Taylor-Clark K. The public’s response to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:925–931. doi: 10.1086/382355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brug J., Aro A.R., Oenema A., de Zwart O., Richardus J.H., Bishop G.D. SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:1486–1489. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.040283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chan S.S.C., So W.K.W., Wong D.C.N., Lee A.C.K., Tiwari A. Improving older adults’ knowledge and practice of preventive measures through a telephone health education during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: a pilot study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007;44:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheng C., Ng A.-K. Psychosocial factors predicting SARS-Preventive behaviors in four major SARS-Affected regions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006;36:222–247. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00059.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chuo H.-Y. Restaurant diners’ self-protective behavior in response to an epidemic crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014;38:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Des Jarlais D.C., Galea S., Tracy M., Tross S., Vlahov D. Stigmatization of newly emerging infectious diseases: AIDS and SARS. Am. J. Public Health. 2006;96:561–567. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Des Jarlais D.C., Stuber J., Tracy M., Tross S., Galea S. Social factors associated with AIDS and SARS. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:1767–1769. doi: 10.3201/eid1111.050424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deurenberg-Yap M., Foo L.L., Low Y.Y., Chan S.P., Vijaya K., Lee M. The Singaporean response to the SARS outbreak: knowledge sufficiency versus public trust. Health Promot. Int. 2005;20:320–326. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hazreen A.M., Myint Myint S., Farizah H., Abd Rashid M., Chai C.C., Dymna V.K., Gilbert W., Sri Rahayu S., Seri Diana M.A., Noor Huzaimnah H. An evaluation of information dissemination during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak among selected rural communities in Kuala Kangsar. Med. J. Malaysia. 2005;60:180–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ishizaki T., Imanaka Y., Hirose M., Hayashida K., Kizu M., Inoue A., Sugie S. Estimation of the impact of providing outpatients with information about SARS infection control on their intention of outpatient visit. Health Policy. 2004;69:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lau J.T.F., Yang X., Tsui H., Kim J.H. Monitoring community responses to the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: from day 10 to day 62. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2003;57:864–870. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.11.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lau J.T.F., Yang X., Pang E., Tsui H.Y., Wong E., Wing Y.K. SARS-related perceptions in Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:417–424. doi: 10.3201/eid1103.040675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lau J.T.F., Yang X., Tsui H., Pang E., Kim J.H. SARS preventive and risk behaviours of Hong Kong air travellers. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004;132:727–736. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804002225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leung G.M., Lam T.-H., Ho L.-M., Ho S.-Y., Chan B.H.Y., Wong I.O.L., Hedley A.J. The impact of community psychological responses on outbreak control for severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2003;57:857–863. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.11.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leung G.M., Ho L.-M., Chan S.K.K., Ho S.-Y., Bacon-Shone J., Choy R.Y.L., Hedley A.J., Lam T.-H., Fielding R. Longitudinal assessment of community psychobehavioral responses during and after the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40:1713–1720. doi: 10.1086/429923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leung G.M., Quah S., Ho L.-M., Ho S.-Y., Hedley A.J., Lee H.-P., Lam T.-H. A tale of two cities: community psychobehavioral surveillance and related impact on outbreak control in Hong Kong and Singapore during the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2004;25:1033–1041. doi: 10.1086/502340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leung G.M., Quah S., Ho L.M., Ho S.Y., Hedley A.J., Lee H.P., Lam T.H. Community psycho-behavioural surveillance and related impact on outbreak control in Hong Kong and Singapore during the SARS epidemic. Hong Kong Med. J. 2009;15(Suppl 9):30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lim V.K.G. War with SARS: an empirical study of knowledge of SARS transmission and effects of SARS on work and the organisations. Singapore Med. J. 2003;44:457–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peng E.Y.-C., Lee M.-B., Tsai S.-T., Yang C.-C., Morisky D.E., Tsai L.-T., Weng Y.-L., Lyu S.-Y. Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: an example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2010;109:524–532. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60087-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Quah S.R., Hin-Peng L. Crisis prevention and management during SARS outbreak, Singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:364–368. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Seng S.L., Lim P.S., Ng M.Y., Wong H.B., Emmanuel S.C. A study on SARS awareness and health-seeking behaviour - findings from a sampled population attending National Healthcare Group Polyclinics. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 2004;33:623–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.So W.K.W., Chan S.S.C., Lee A.C.K., Tiwari A.F.Y. The knowledge level and precautionary measures taken by older adults during the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2004;41:901–909. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tan X., Li S., Wang C., Chen X., Wu X. Severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic and change of people’s health behavior in China. Health Educ. Res. 2004;19:576–580. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tang C.S.K., Wong C.-Y. An outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome: predictors of health behaviors and effect of community prevention measures in Hong Kong, China. Am. J. Public Health. 2003;93:1887–1888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tang C.S.-K., Wong C.-Y. Psychosocial factors influencing the practice of preventive behaviors against the severe acute respiratory syndrome among older chinese in Hong Kong. J. Aging Health. 2005;17:490–506. doi: 10.1177/0898264305277966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tracy C.S., Rea E., Upshur R.E.G. Public perceptions of quarantine: community-based telephone survey following an infectious disease outbreak. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:470. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vartti A.-M., Oenema A., Schreck M., Uutela A., de Zwart O., Brug J., Aro A.R. SARS knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors: a comparison between Finns and the Dutch during the SARS outbreak in 2003. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009;16:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s12529-008-9004-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wong C.-Y., Tang C.S.-K. Practice of habitual and volitional health behaviors to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Adolesc. Health. 2005;36:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yip H.K., Tsang P.C.S., Samaranayake L.P., Li A.H.P. Knowledge of and attitudes toward severe acute respiratory syndrome among a cohort of dental patients in Hong Kong following a major local outbreak, Community Dent. Health. 2007;24:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Zwart O., Veldhuijzen I.K., Elam G., Aro A.R., Abraham T., Bishop G.D., Voeten Hélène A.C.M., Richardus J.H., Brug J. Perceived threat, risk perception, and efficacy beliefs related to SARS and other (emerging) infectious diseases: results of an international survey. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009;16:30–40. doi: 10.1007/s12529-008-9008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Al-Hazmi A., Gosadi I., Somily A., Alsubaie S., Bin Saeed A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of secondary schools and university students toward Middle East Respiratory Syndrome epidemic in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018;25:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Al-Mohaissen M. Awareness among a Saudi Arabian university community of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus following an outbreak, East. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2017;23:351–360. doi: 10.26719/2017.23.5.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Almutairi K.M., Al Helih E.M., Moussa M., Boshaiqah A.E., Saleh Alajilan A., Vinluan J.M., Almutairi A. Awareness, Attitudes, and Practices Related to Coronavirus Pandemic Among Public in Saudi Arabia. Fam. Community Health. 2015;38:332–340. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Alotaibi M.S., Alsubaie A.M., Almohaimede K.A., Alotaibi T.A., Alharbi O.A., Aljadoa A.F., Alhamad A.H., Barry M. To what extent are Arab pilgrims to Makkah aware of the middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus and the precautions against it? J. Family Community Med. 2017;24:91–96. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.205119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alqahtani A.S., Wiley K.E., Mushta S.M., Yamazaki K., BinDhim N.F., Heywood A.E., Booy R., Rashid H. Association between Australian Hajj Pilgrims’ awareness of MERS-CoV, and their compliance with preventive measures and exposure to camels. J. Travel Med. 2016;23 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taw046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alqahtani A.S., Wiley K.E., Tashani M., Heywood A.E., Willaby H.W., BinDhim N.F., Booy R., Rashid H. Camel exposure and knowledge about MERS-CoV among Australian Hajj pilgrims in 2014. Virol. Sin. 2016;31:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s12250-015-3669-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Alqahtani A.S., Rashid H., Basyouni M.H., Alhawassi T.M., BinDhim N.F. Public response to MERS-CoV in the Middle East: iPhone survey in six countries. J. Infect. Public Health. 2017;10:534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Althobaity H.M., Alharthi R.A.S., Altowairqi M.H., Alsufyani Z.A., Aloufi N.S., Altowairqi A.E., Alqahtani A.S., Alzahrani A.K., Abdel-Moneim A.S. Knowledge and awareness of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus among Saudi and Non-Saudi Arabian pilgrims. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim) 2017;11:20–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ashok N., Rodrigues J.C., Azouni K., Darwish S., Abuderman A., Alkaabba A.A.F., Tarakji B. Knowledge and apprehension of dental patients about MERS-A questionnaire survey. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016;10:ZC58–62. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/17519.7790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bawazir A., Al-Mazroo E., Jradi H., Ahmed A., Badri M. MERS-CoV infection: mind the public knowledge gap. J. Infect. Public Health. 2018;11:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gautret P., Benkouiten S., Salaheddine I., Belhouchat K., Drali T., Parola P., Brouqui P. Hajj pilgrims knowledge about Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, August to September 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.41.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hoda J. Identification of information types and sources by the public for promoting awareness of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia. Health Educ. Res. 2016;31:12–23. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hou Y.’a., Tan Y.-R., Lim W.Y., Lee V., Tan L.W.L., Chen M.I.-C., Yap P. Adequacy of public health communications on H7N9 and MERS in Singapore: insights from a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:436. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5340-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kamau E., Ongus J., Gitau G., Galgalo T., Lowther S.A., Bitek A., Munyua P. Knowledge and practices regarding Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus among camel handlers in a Slaughterhouse, Kenya, 2015. Zoonoses Public Health. 2019;66:169–173. doi: 10.1111/zph.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lee M., Ju Y., You M. The effects of social determinants on public health emergency preparedness mediated by health communication: The 2015 mers outbreak in south korea. Health Commun. 2019 doi: 10.1080/10410236.2019.1636342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee S.Y., Yang H.J., Kim G., Cheong H.-K., Choi B.Y. Preventive behaviors by the level of perceived infection sensitivity during the Korea outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in 2015. Epidemiol. Health. 2016;38 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lin L., McCloud R.F., Bigman C.A., Viswanath K. Tuning in and catching on? Examining the relationship between pandemic communication and awareness and knowledge of MERS in the USA. J. Public Health (Oxf) 2017;39:282–289. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdw028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Migault C., Kanagaratnam L., Hentzien M., Giltat A., Nguyen Y., Brunet A., Thibault M., Legall A., Drame M., Bani-Sadr F. Effectiveness of an education health programme about Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus tested during travel consultations. Public Health. 2019;173:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nooh H.Z., Alshammary R.H., Alenezy J.M., Alrowaili N.H., Alsharari A.J., Alenzi N.M., Sabaa H.E. Public awareness of coronavirus in Al-Jouf region, Saudi Arabia. Z. Gesundh. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01209-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sahin M.K., Aker S., Kaynar Tuncel E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning Middle East respiratory syndrome among Umrah and Hajj pilgrims in Samsun, Turkey, 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.38.30023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tashani M., Alfelali M., Barasheed O., Fatema F.N., Alqahtani A., Rashid H., Booy R. Australian Hajj pilgrims’ knowledge about MERS-CoV and other respiratory infections. Virol. Sin. 2014;29:318–320. doi: 10.1007/s12250-014-3506-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yang S., Cho S.-I. Middle East respiratory syndrome risk perception among students at a university in South Korea, 2015. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2017;45:e53–e60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yang J., Park E.-C., Lee S.A., Lee S.G. Associations between hand hygiene education and self-reported hand-washing behaviors among korean adults during MERS-CoV outbreak. Health Educ. Behav. 2019;46:157–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198118783829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yoo W., Choi D.-H., Park K. The effects of SNS communication: how expressing and receiving information predict MERS-preventive behavioral intentions in South Korea. Comput. Human Behav. 2016;62:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Betsch C., Wieler L., Bosnjak M., et al. 2020. Germany COVID-19 Snapshot MOnitoring (COSMO Germany): Monitoring Knowledge, Risk Perceptions, Preventive Behaviours, and Public Trust in the Current Coronavirus Outbreak in Germany.https://www.psycharchives.org/handle/20.500.12034/2501 (accessed 8 May 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 120.Okan O., de Sombre S., Hurrelmann K., Berens E.M., Bauer U., Schaeffer D. 2020. Gesundheitskompetenz Der Bevölkerung Im Umgang Mit Der Coronavirus-pandemie. (accessed 7 May 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 121.Alotaibi M.S., Alsubaie A.M., Almohaimede K.A., Alotaibi T.A., Alharbi O.A., Aljadoa A.F., Alhamad A.H., Barry M. To what extent are Arab pilgrims to Makkah aware of the middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus and the precautions against it? J. Family Community Med. 2017;24:91–96. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.205119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hoda J. Identification of information types and sources by the public for promoting awareness of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia. Health Educ. Res. 2016;31:12–23. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]