Abstract

Here, using human metallothionein (MT2) as an example, we describe an improved strategy based on differential alkylation coupled to MS, assisted by zinc probe monitoring, for identification of cysteine-rich binding sites with nanomolar and picomolar metal affinity utilizing iodoacetamide (IAM) and N-ethylmaleimide reagents. We concluded that an SN2 reaction provided by IAM is more suitable to label free Cys residues, avoiding nonspecific metal dissociation. Afterward, metal-bound Cys can be easily labeled in a nucleophilic addition reaction after separation by reverse-phase C18 at acidic pH. Finally, we evaluated the efficiency of the method by mapping metal-binding sites of Zn7–xMT species using a bottom-up MS approach with respect to metal-to-protein affinity and element(al) resolution. The methodology presented might be applied not only for MT2 but to identify metal-binding sites in other Cys-containing proteins.

Approximately one-third of human genes encode proteins that bind metal ions, and in around 10% of the proteome, Zn2+ ions are used as a catalytic, structural, and regulatory cofactor.1−4 Metallothioneins (MTs) play a role in homeostatic control of Zn2+ and Cu+ ions in cellular signaling and transduction networks by muffling reactions.5 They bind metal ions and serve as both metal donor or acceptor, controlling the cellular Zn2+ fluctuations in the cytosol, nucleus, or mitochondria.6,7 Mammalian MTs are low molecular mass (6–7 kDa) cysteine-rich molecules that bind multiple metal ions in a multiple tetrathiolate coordination environment within two separate MxSy clusters.8,9 In humans, there exist at least a dozen MT proteins, categorized into subfamilies (MT1–4 isoforms and MT1 subisoforms) depending on sequence, tissue localization, function specificity, or metal-binding properties.8,10 Cysteine (Cys) is the most nucleophilic amino acid residue, commonly binding essential as well as toxic metal ions.11,12 Moreover, the Cys residue is a cellular target for reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species, and it is post-translationally modified in S-methylation and S-linked acylation, among other reactions.13−16 Thus, Cys acts in multiple proteins as a redox switch, depending on the oxidative molecules and metal ion concentration.17−20 Because of the aforementioned relevance, a range of experimental and theoretical tools has been developed aimed at identifying different Cys residue states in proteomes.21−24 Most of the chemical tools are based on the nucleophilic reaction of Cys toward thiol-specific probes, which may exhibit different reactivity, enabling differentiation of the cysteine sulfur state.25 Some of these common protein thiol probes are iodoacetamide (IAM), iodoacetic acid (IAA), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS), Cys-reactive mass tag (cys-TMT), and p-benzoquinone (Bq).21,22 Among them, IAM and NEM are commonly used, forming covalent products with sulfhydryl groups by an SN2 nucleophilic substitution or by nucleophilic Michael addition, respectively.13,26 NEM reacts with thiols faster than IAM and also exhibits a wider range of pH applicability.27 It shows an appreciable rate even at acidic pH, whereas IAM requires neutral or basic pH.26,27 However, NEM exhibits less specificity, which gives rise to side reactions with histidine and lysine residues when NEM is used at large excess or basic pH.13,26 On the other hand, IAM is preferred since it forms a very stable thioether, whereas NEM might undergo partial ring hydrolysis.27 These alkylation reagents have been independently used in the past to study Cd2+ binding kinetics, to follow the cluster formation,28−30 or to gain insights into partially Zn2+-metalated species in metallothionein.31 Other examples include the differential alkylation for mapping Cys redox states, on purified proteins but also in cellular proteomes.32−36 Differential alkylation traditionally is based on blocking a reduced free thiol with one alkylator followed by a reduction step and a second alkylation.25 Other derived strategies are based on a dual parallel experiment in which a native protein and the treated protein are both labeled by the alkylation reagent.31,37 For instance, if one is interested in localizing metal-binding Cys residues, the protein is treated by removing the metal ion by chelation or reducing the pH to promote metal dissociation and then labeling.37−39 Subsequently, by comparing both experiments, the native metalloprotein labeled and the treated protein, one might inquire into a particular Cys residue participating in metal ion binding.31 This methodology coupled to state-of-art mass spectrometry (MS) techniques has been successfully used in the past in Cd2+- and Zn2+-containing MT studies.31,37,40,41 Despite the efforts and advances made, these methods still present several limitations in metalloproteomic studies.42 In principle, a metal-bound thiolate would decrease its reactivity toward nucleophiles and thus no modification would occur under controlled conditions because it is metal-protected.24,40,43 This is a fact for a kinetically inert metal–Cys bond.44 For instance, 2 out of 10 Cys residues from the p53 core domain were found to be reactive toward NEM.45 Identification of the Cys positions revealed that they do not belong to the Zn(Cys)3(His) core, which remained unmodified.45 Not only the kinetic stability but also the thermodynamic stability of the metal–protein complex dictates how the reaction proceeds. In the presence of the same ligand, properties of the metal ion influence the thermodynamic stability of the protein complex. For instance, Cd2+, which in terms of the hard–soft acid–base concept is significantly softer than Zn2+, is bound more strongly to Cys4 sites and more weakly to the Cys2His2 core.46 Therefore, proteins with a low or moderate Zn2+ binding affinity (log Kb of 7–10) and kinetically labile metal–protein bonds, such as MT2, might reveal other scenarios.47 The alkylator concentration and time of reaction should be particularly optimized to avoid Zn2+ dissociation from the reactive Zn2+-bound Cys residue. Unlike traditional differential alkylation, a similar reactivity might appear for a metal-bound Cys and for a free Cys residue with a low pKa, which hinders their nucleophilic differentiation.23−25 The local electrostatic environment will affect the acidity of Cys residues present in the protein, dictating the reactivity toward the electrophile.48 This might lead to situations in which an M(Cys)4 core is alkylated without metal dissociation. The situation where a reactive Cys residue participates in coordination of both a metal ion and an alkylator moiety has been previously observed.28,37,49 Three possible scenarios need to be contemplated: (i) alkylation of a free Cys residue, (ii) alkylation of a metal-bound Cys residue without metal ion dissociation, and (iii) alkylation of a metal-bound Cys residue and subsequent metal ion dissociation. Therefore, finding a reagent or reaction conditions that distinguish between free Cys and metal-protected Cys residues is a fundamental issue. Moreover, high-resolution methods such MS are greatly needed to follow the modification extent but also to identify metal-binding sites.50,51 Using soft electrospray ionization (ESI) conditions and transmission parameters, native conditions might be preserved during ESI-MS analysis, maintaining the noncovalent metal–protein interactions, the solution-phase populations, and the conformational states for the labeled metal-bound protein.52−56 During the last 2 decades, a vast number of research studies have applied ESI-MS for MT investigations.28,31,37,40,57−59 To map the modification sites, top-down sequencing provides an easy and fast way, although it still provides a lower sequencing coverage than bottom-up approaches.60,61

Here, we describe an improved strategy based on differential alkylation coupled to MS for identification of multi-Cys metal-binding sites with nanomolar and picomolar metal affinity in MT2 by utilizing IAM and NEM reagents. First, we studied the kinetic and thermodynamic lability of Zn2+– and Cd2+–thiolate bonds in Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2 using both alkylators and analyzed them by UV–vis, matrix-assisted-laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS), and ESI-MS methods. Most biophysical research has used Cd2+ for MT study since it produces well-defined spectroscopic signals, in contrast to spectroscopically silent Zn2+.31 Notably, MTs were originally isolated as a mixed Zn2+/Cd2+ complex.8 For our purposes, MT2 was used as a model of a protein with various low, moderate, and high Zn2+ binding affinities. It is worth noting that the first three Zn2+ ions dissociating from MT2 demonstrate nano- and subnanomolar affinity, perfect for this investigation. Comparing the reactivity with the more thermodynamically stable Cd7MT2 protein (low pico- and femtomolar affinity) illustrated the issue regarding the metal–protein stability and the phenomena of metal dissociation. Through this, we ranked and ordered the reactivity, allowing us to develop a differential alkylation strategy to map partially Zn2+-loaded Zn7–xMT2 species. We demonstrated that IAM is more suitable than NEM to be used as the first labeling reagent in order to label free Cys residues. The lower reactivity of IAM prevents the metal ion dissociation, whereas its small size and hydrophilic character allow access to buried free thiols.40,62 This step was followed by metal ion removal with acidification and a subsequent second labeling reaction with NEM. Although we and others demonstrated that addition of NEM without acidification may dissociate all seven Zn2+ from Zn7MT2, different conclusions are found for Cd7MT2.28,30 NEM did not dissociate all seven Cd2+ due to the higher Cd2+-to-protein affinity. Another factor that may limit the metal ion dissociation with addition of NEM without acidification is the thiol accessibility. The low pH greatly facilitates the access of NEM to all of the Cys residues, independently if they were buried or solvent-exposed Cys residues.24 For this purpose, NEM offers faster kinetics than iodoacetamide derivatives, even at low pH.26,27 Thus, in order to elaborate a general method that may be applicable for other Cys-containing proteins, with higher metal-to-protein affinity and with different thiol accessibility,63,64 we introduced an acidification step prior to NEM labeling. Altogether, this ensures metal ion removal independent of how strongly they are bound and facilitates the access of NEM to the thiols. Afterward, utilizing the differential alkylation developed, we identified the Zn2+-binding Cys residues in Zn7–xMT2 species with a bottom-up MS approach. The methodology presented herein represents a general technique to study metal-binding Cys-containing proteins, independently of their metal-binding properties and protein structure.

Experimental Section

Materials

All reagents used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Group), Acros Organic, Roth, BioShop, VWR International (Avantor), and Iris-Biotech GmbH. The pH buffers and solutions were prepared with Milli-Q water (Merck Millipore), incubated with Chelex 100 resin (Bio-Rad) and degassed to eliminate trace metal ion contamination. For more detailed information about materials employed see the Supporting Information (SI).

Expression and Purification of Metallothionein

MT2 (Addgene plasmid ID 105693) was overexpressed in a bacterial system and purified as previously described.31 Detailed information may be found in the SI.

Reactions of Zn7MT and Cd7MT with NEM and IAM Alkylation Reagents

To study the metal release reactions, 15 μM Zn7MT2 or Cd7MT2 in 50 mM ammonium acetate (pH 7.4) and 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) solution were incubated with a total of 0.01, 15, 40, 180, 715, 1400, and 3600 mol equiv of IAM or NEM for 15 and 60 min at 25 °C in darkness. All solutions and plastic tubes were previously degassed by purging with nitrogen. To measure the modification profile by MALDI-MS, an aliquot of 12 μL was taken for each sample and purified by ZipTip μ-C18 with 5 μL of Milli-Q water/acetonitrile (ACN) solution (50:50, v/v) for elution. The rest of the sample (80 μL) was purified using a 3 kDa Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter for 10 min under a nitrogen blanket and analyzed by ESI-MS. Care was taken to avoid oxidation of the free thiols,37 using a low capillary voltage (2 kV), in the presence of 1 mM TCEP and a nitrogen blanket. We used TCEP as a reducing agent since it binds zinc less tightly than DL-dithiothreitol (DTT) (submillimolar affinity).31 Under our experimental conditions, we did not observe oxidation of thiols, as confirmed by ESI-MS analysis.

Identification of Zn2+-Binding Sites by a Dual Labeling Strategy

Zn7MT2 was purified by size exclusion chromatography with 10 mM HCl, and the concentration of apoMT was estimated by 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) and Cd2+ titration experiments. Then, apoMT was saturated with 4, 5, 6, or 7 mol equiv of ZnSO4 under a nitrogen blanket in the presence of 1 mM TCEP, followed by buffer exchange to 50 mM ammonium acetate (pH 7.4) and purification with a 10 min spin time (three times) using 3 kDa Amicon filters, purging nitrogen, and addition of 1 mM TCEP at each round. Partially metalated proteins were subsequently analyzed by ESI-MS. Then, a 15 μM Zn0–7MT2 aliquot was incubated in 1 mM IAM (15 min, 25 °C) in darkness. From this, an aliquot was purified by ZipTip μ-C18, as done previously, and measured by MALDI-MS. Another aliquot was analyzed by ESI-MS. The rest of the sample (80 μL) followed the dual-labeling strategy. First, the pH was reduced with 0.1% formic acid (FA) and 1 mM DTT and the excess IAM removed by purification with C18 resin. Eluted protein was double-labeled with incubation in 3 mM NEM (30 min, 25 °C). After that, an aliquot was analyzed by MALDI-MS. The rest of the sample underwent a bottom-up MS approach by digestion in a solution using trypsin at a weight ratio of 1:20 (30 min, 37 °C). The trypsinization reaction was quenched by addition of 5 μL of 0.1% FA.

UV–Vis Spectroscopy

UV–vis spectra were recorded on a JASCO V-650 spectrophotometer at 25 °C with a 1 cm quartz cuvette. The Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2 reactions with NEM and IAM were followed at 492 nm using 100 μM Zincon (ZI) or 4-(2-pyridylazo)resorcinol (PAR) in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4, NaCl 150 mM) buffer, respectively.65,66 To avoid oxidation, 1 mM TCEP was used as a non-metal-binding reducing agent. The reactions were followed at 618 and 492 nm, respectively, for a period of 0–24 h.

ESI-MS

ESI-MS experiments were performed on a quadrupole time-of-flight (qTOF) Bruker Maxis Impact mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) calibrated with a commercial ESI-TOF tuning mix (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were directly infused with a 1 μL/min flow rate. ESI-MS spectra were recorded in positive mode with a capillary voltage of 2 kV, end plate offset potential of 500 V, nebulizer gas (N2) pressure of 1.5 bar, drying gas (N2) flow rate of 4 L/min, and drying temperature of 180 °C. The mass range was set from 500 to 3000 m/z and recorded and averaged over 1 min. The Bruker Compass data analysis software package and in-house R scripts were used to analyze the data.

MALDI-MS

A MALDI-TOF/TOF MS Bruker UltrafleXtreme instrument (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) was used for MALDI-MS experiments. 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA) were used as the MALDI-TOF matrix for protein and peptide analysis, respectively. The saturated matrix solution was prepared in 30% ACN and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. MALDI-MS analysis of proteins was performed in a linear positive mode in the 2–20 kDa range. The mass spectra were typically acquired by averaging 2000 subspectra from a total of 2000 laser shots per spot. The laser power was set at 5–10% above the threshold. The calibration was done using a standard peptide and protein calibration mixture obtained from Bruker (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). MALDI-TOF/TOF measurements of peptides were performed in reflector positive mode in the 0–4 kDa range. Moreover, a LIFT cell was used for MS/MS analysis of detected peptides.67 The instrument was controlled by flexControl ver. 3.4 and flexAnalysis ver. 3.4 software. BioTools 3.2 SR3 and Sequence Editor (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) were used to analyze the MALDI-MS data.

Results and Discussion

The first part of this research attempted to study the kinetic and thermodynamic lability of Zn2+–thiolate bonds in fully saturated Zn7MT2 and to compare it with its cadmium counterpart. To do so, zinc and cadmium proteins were incubated with increasing concentrations of both alkylation reagents NEM and IAM for different periods of time. The reaction was then simultaneously followed by native ESI-MS and MALDI-MS (Figure 1A). Complementarily, UV–vis spectrophotometric studies were carried out using chromophoric chelating probes ZI and PAR, respectively, to monitor the Zn2+ and Cd2+ dissociation upon protein modification. ZI forms a weak ZnZI complex with a dissociation constant of Kd = 2.09 × 10–6 M at pH 7.465 that ensures no Zn2+ competition with Zn7MT2 protein. Because Cd2+ binds less tightly to ZI than Zn2+, we could apply PAR to monitor the Cd2+ dissociation upon alkylation in a more quantitative way without Cd2+ competition with Cd7MT2.65,66 No doubt, ESI can retain the native-like structures, possibly because of the kinetic trapping effect.68 However, complementing gas-phase MS and solution experiments might require caution to be taken due to concentration-dependent rate limitations, differences in the solvent composition, or pH-induced changes.69 However, general trends and conclusions obtained from both gas-phase and solution experiments matched very well, as will be presented in the next section.

Figure 1.

Overview of the hereby presented differential labeling approach. (A) Steps of the procedure for labeling free- and metal-bound Cys residues by IAM and NEM, respectively. (B) Human metallothionein-2 (MT2) sequence with indicated tryptic fragments and position numbers of Cys residues. Arrows indicate the cleavage positions of the C-terminal lysine, specific for trypsin enzyme.

Profiling Reactive Cysteine Residues in Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2 Proteins by NEM and IAM

The oxidative alkylation and subsequent metal dissociation from Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2 were followed with MALDI-MS, ESI-MS, and UV–vis experiments at increasing concentrations of both alkylating reagents and as a function of time (Table 1 and Figures 2 and 3). Note that in solution experiments detected ca. 1 equiv less of Cd2+/Zn2+ displaced than for the gas-phase experiments for the same reaction time (60 min) (Figure S3, SI). The detected number of metal ions displaced at 200 min using UV–vis experiments followed a similar pattern as obtained at 60 min in the gas-phase experiments. However, particular differences encountered may be attributed to pH-induced changes, as ammonium acetate likely undergoes acidification in the ESI plume,69 or to differences due to the absence of nonvolatile salts in ESI-MS.70 As demonstrated with submicron electrospray emitters, the concentration of NaCl might stabilize protein conformations toward more compact structures.70,71 Besides, the spectroscopic signal is an average response of all the species in solution. Figure 2 contains the Cys modification profile obtained with MALDI-MS and the number of metal ions transferred to PAR and ZI measured with UV–vis, as a function of NEM or IAM concentration. The data shows that small amounts of both NEM or IAM lead to a single cysteine alkylated without metal dissociation [Table 1 and Figure S4 (SI)]. Noticeable differences in the reaction of NEM with Zn7MT2 were observed in the gas phase and in solution (Table 1). Meanwhile, ESI-MS captured the intermediate Zn7NEM1MT2, and approximately 2.5 Zn2+ dissociated rapidly in solution [Table 1 and Figure S4 (SI)]. The number of Zn2+ detected by UV–vis practically did not change after addition of 40 equiv of alkylator, but the product ion [Zn4NEM9–11MT2]5+ showed up in the ESI-MS spectra [Figure 2A, Table 1, and Figure S4 (SI)]. These results are consistent with the 10 Cys being NEM-labeled, suggesting a concomitant full β-domain modification, where 3 Zn2+ had been dissociated (Figure 2A). The reaction intermediate Zn4NEM9–11MT2 disappeared after addition of 180 equiv of NEM with the formation of metal-depleted MT (NEM20MT2) [Table 1 and Figure S4 (SI)]. Its Cd2+ counterpart (Cd4NEM9–11MT2) appeared and remained the most abundant, even at large molar excess, which clearly shows the higher Cd2+-to-protein affinity. On the other hand, less reactive IAM required at least 180 equiv to provoke Zn2+ dissociation and to form the intermediates Zn4IAM9–11MT2. In disagreement, UV–vis experiments showed that only one Zn2+ dissociated from the protein. Note that the spectroscopic signal obtained is the average response from dynamic equilibria between multiple species. This hypothesis is supported by the Cys modification profile that showed a broad number of modifications (Figure 2B). Increasing to 750 equiv of alkylator leads to the formation of the intermediate Cd4IAM9–10MT2 and the species Zn0–2IAM0–12MT2 that were metal-stripped after doubling the IAM concentration [Table 1, Figure 2B, and Figure S5 (SI)]. Interestingly, IAM was able to alkylate and dissociate the four Cd2+ from the Cd4(Cys)11 α-domain, while the intermediate Cd4NEM9–11MT2 remained stable. Thus, not only the higher metal-to-protein affinity but also the bigger size of NEM inhibits the access to the thiols buried in the Cd4S11 cluster. In agreement with ESI-MS experiments, NEM reached a plateau with ca. 11 Cys modified for Cd7MT2 (Figures 2A and 3A). UV–vis confirmed that, even after 24 h of incubation with 3600 equiv of NEM, no more than 4 equiv of Cd2+ was detected (Figure 3B). IAM, on the other hand, did not stabilize any intermediate (Figure 3C,D).

Table 1. Oxidative Alkylation and Subsequent Metal Dissociation from Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2 Followed with MALDI-MS, ESI-MS, and UV–Vis Experiments at Increasing Concentrations of IAM and NEM Alkylating Reagents.

| NEM |

IAM |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| equiv | protein | species (ESI-MS) | metal ions transferred (UV–vis) | Cys residues modifieda (MALDI-MS) | species (ESI-MS) | metal ions transferred (UV–vis) | Cys residues modifieda (MALDI-MS) |

| 15 | Cd7MT | Cd7NEM0–1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | Cd7IAM0–1 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Zn7MT | Zn7NEM0–1 | 2.5 | 1.0 | Zn7IAM0–1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | |

| 40 | Cd7MT | Cd6NEM2–3 | 1.2 | 2.5 | Cd7IAM0–1 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Cd7NEM2–3 | |||||||

| Zn7MT | Zn4NEM9–11b | 3.0 | 10.0 | Zn7IAM0–1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | |

| 180 | Cd7MT | Cd4NEM9–11 | 1.3 | 7.5 | Cd6IAM3–5 | 0.3 | 2.5 |

| Zn7MT | Zn0NEM19–20 | 5.6 | 17.5 | Zn4IAM9–11 | 1.0 | 6.0 | |

| 750 | Cd7MT | Cd4NEM10–12 | 2.3 | 11.0 | Cd4IAM9–10 | 0.3 | 7.0 |

| Zn7MT | Zn0NEM19–20 | 6.7 | 19.0 | Zn0IAM19–20 | 2.4 | 14.0 | |

| Zn1IAM15–1 | |||||||

| Zn2IAM6–12 | |||||||

| 1400 | Cd7MT | Cd4NEM9–11 | 2.7 | 12.5 | Cd0IAM18–20 | 1.2 | 13.0 |

| Cd2IAM17 | |||||||

| Cd3IAM14 | |||||||

| Zn7MT | Zn0NEM19–20 | 6.8 | 19.5 | Zn0IAM18–20 | 3.5 | 14.5 | |

| Zn1IAM15–16 | |||||||

| Zn2IAM6–12 | |||||||

Figure 2.

Dependence of the molar ratio (0–3600 equiv) of alkylating agents NEM and IAM on the Cys residue modification (A and B, respectively) monitored with MALDI-MS and the metal dissociation from Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2 analyzed by UV–vis spectrophotometry (C and D, respectively). MALDI-MS and UV–vis spectra were recorded after 60 and 200 min of sample incubation at 25 °C. Metal ion dissociation was analyzed using Zincon and PAR assays.59,60 Red and blue stand for Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2, respectively. Cd2+ and Zn2+ refer to Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2 proteins.

Figure 3.

Analysis with bar plot of MALDI-MS cysteine profiling for Cd7MT2 and Zn7MT2 to which 15, 750, and 1400 equiv of NEM or IAM (A and C, respectively) had been added and incubated with for 15 and 60 min at 25 °C. UV–vis experiments of Cd7MT2 and Zn7MT2 to which 3600 equiv of NEM had been added and incubated with for 0–1450 min (B and D, respectively). Red and blue stand for Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2, respectively. Gray and cyan stand for 15 and 60 min of alkylation, respectively.

In the light of these results, we interpret the data as follows (Scheme 1): NEM empties out the β-domain faster than IAM, forming the Cd4MT2 α-cluster or a Zn4MT2 where the Zn2+ are redistributed within the α- and β-domains. The higher Cd2+–S bond stability was directly probed for both alkylator reagents. Similarly, the latter occurs for the α,β-Zn4MT product, indicating lower kinetic lability (indeed, more inert to breaking metal–ligand bonds). Subsequently, IAM dissociated the four α-domain Cd2+ and NEM still did not dissociate the remaining α-Cd4S11 cluster. This suggests an additional factor to Cd2+–S bond stability preventing the disruption of Cd4NEM9–11MT2. Therefore, the lower IAM reactivity could benefit the mapping of free Cys residues without altering metal-binding sites, even in these proteins with low metal-to-protein affinity. The small size and hydrophilic character of IAM allows Cys-labeling, even for the Cys residues that are buried.40,62

Scheme 1. Summary of the Structures Obtained as the Reaction Progressed Followed by either Increasing the Equivalents of NEM or IAM or Increasing the Reaction Time.

The structures are based on the combination of the methods explored in this research, through cysteine profiling with MALDI-MS and metal probe monitoring with UV–vis and native ESI-MS. The Zn7MT2 and Cd7MT2 proteins were incubated with NEM or IAM at different molar equivalents (e.g. 40, 180, 750, and 1400) for 60 min. In the other option, the proteins were incubated at fixed molar equivalents of NEM or IAM (3600 equiv for UV–vis and 750 or 1400 equiv for MALDI-MS and ESI-MS), and the reaction was followed over time (0–1450 min for UV–vis and 0–60 min for MALDI-MS and ESI-MS).

Mapping the Zn4–7MT2 Species—Pinpointing the Zn2+-Binding Sites

The previous results helped us with the main aim of this research: the improvement of a differential alkylation strategy to map Zn2+-binding sites in partially Zn2+-loaded proteins.31 We demonstrated how the use of first IAM followed by NEM to label metal-free Cys residues in the presence and absence of Zn2+ is the best choice (Figure 1A).

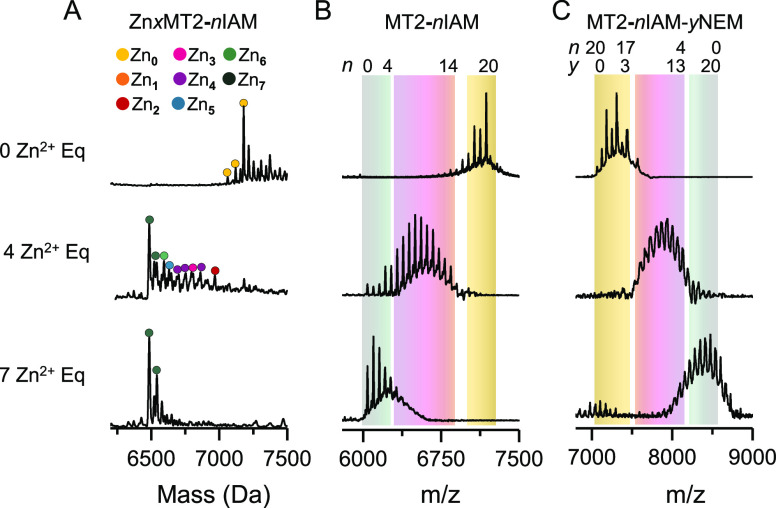

For this purpose, native ESI-MS and MALDI-MS analysis for metal-free IAM-labeled samples showed modifications ranging from 17 to 20, where the latter was the maximum (Figure 4A,B). Parallel nESI-MS analysis annotated peaks corresponding to [Zn0IAM18–20MT2]4+, with the fully modified species being the most abundant [Figure 4A and Table S1 (SI)]. After removing the excess IAM, NEM-labeled apoMT2 analyzed by MALDI-MS showed a peak previously fully modified by IAM (7183.3 m/z) but also double-labeled peaks with both IAM and NEM (Figure 4C). The distribution of modifications was centered at 7319 m/z, which corresponds to the IAM18NEM2MT2 species with a visible 7308 m/z peak that comes from overalkylation of IAM20NEM1MT2. With the conditions applied, we only observed one non-cysteine residue reacting with NEM. Double-labeled peaks extended up to forming IAM17NEM3MT2 species (7388 m/z).

Figure 4.

Native ESI-MS (A) and MALDI-MS analysis (B) of apoMT2 with 0, 4, and 7 equiv of Zn2+ to which IAM had been added to a concentration of 1 mM and incubated in darkness for 15 min at 25 °C. After removal of excess IAM and metal ions, NEM was added to a concentration of 3 mM and incubated for 30 min at 25 °C (C). ESI-MS is shown as a deconvolved zero-charge mass spectrum. The x, n, and y stand for the Zn2+ stoichiometry found for gas-phase ions, the number of IAM modifications, and the number of NEM modifications, respectively. The green, pink, and yellow backgrounds in parts B and C refer to the isolated modification profile for 7.4 and 0 Zn2+ equiv added to apoMT2, respectively.

Addition of 4 equiv of Zn2+ to apoMT2 resulted in a wide IAM modification profile ranging from 0 to 14 M with a maximum centered at 8–9 M, which suggests eight or nine noncoordinating Cys residues possibly from the β-domain (Figure 4B). Comparing both the maximum for apoMT2 (20 M) and the results after addition of 4 equiv of Zn2+ (8–9 M) reveals a difference of ∼11–12 modifications (Figure 4B). This might correspond with the number of Cys residues in the α-domain. The nESI-MS analysis confirmed the presence of [Zn4IAM6–10MT2]4+ ions, but also other Zn2+-to-protein stoichiometries are visible [Figure 4A and Table S2 (SI)]. We hypothesized the existence of several conformers, where 4 Zn2+ were located in the α-domain or there are redistributed between both β- and α-domains.

To assess the Cys residues coordinating Zn2+, IAM-labeled Zn4MT2 protein samples were DTT-treated with a reduced pH accompanied by Zn2+ removal and further purification using C18 resin (Figure 1). As concluded before, NEM might be not able to displace all of the metal ions in proteins that binds Zn2+ with high affinity. To elaborate a general method for proteins that binds Zn2+ with low but also with high affinity, we introduced an acidification step for metal ion removal. Moreover, the acidification and metal ion removal promote destabilization of the natively folded structure, facilitating the access of NEM to all of the Cys residues.24 NEM is a suitable reagent for this purpose, since it exhibits fast kinetics even at low pH.26,27 The Zn2+ purified protein was then incubated with an excess of NEM. The former population of singly IAM-labeled peaks now appeared doubly labeled with both IAM and NEM moieties (Figure 4C). For instance, the peak centered at 9 IAM now incorporated 11 NEM molecules in the metal-coordinating Cys residues, forming the IAM9NEM11MT2 species (7936 m/z), which suggests that before to Zn2+ removal, the α-domain was fully occupied with 4 Zn2+. As in the previous step, where the protein was singly labeled with IAM, multiple products are observed.

Inferring the localization of Zn2+ binding among the Cys residues was achieved with a bottom-up approach. In order to demonstrate the approach presented, we worked with purified proteins or complexes, taking advantage of the speed, sensitivity, and mass accuracy in the analysis provided by the MALDI ion source coupled to the TOF detector. However, one needs to consider other analytical platforms in the case of more complex samples. First, we collected peptide mass fingerprints (PMF) from tryptic fragments measured by MALDI-MS [Figure 1B and Figure S8 (SI)]. A detailed analysis showed an emerging fully modified tryptic fragment, NEM3[44–51], from the Zn4MT sample (Figure S9, SI). This fragment was not previously found in the apoMT2 sample, suggesting that all three Cys residues had bound Zn2+. Congruently, IAM3[44–51] is no longer visible (Figure S10, SI). Moreover, we observed the appearance of fragment IAM1NEM4[31–43] sequenced with IAM-labeled Cys41 accompanied by disappearance of IAM4[32–43] (Figures S11 and S12, SI). Fragment NEM3[52–61] from the C-terminal region was also detected, suggesting that it had bound Zn2+. On the other hand, tryptic peptides NEM1[21–30] and NEM2[26-31], corresponding to the N-terminal β-domain, emerged for Zn4MT. De novo sequencing localized NEM-labeled Cys21 for the former tryptic peptide and NEM-labeled Cys26 and Cys29 for the latter one (Figures S13 and S14, SI). This was confirmed by observing how fragment IAM2[23–31] with IAM-labeled Cys26 and Cys29 disappeared (Figure S15, SI). Altogether, the evidence suggests no exclusive selectivity for the first four Zn2+ toward the α-domain but partial redistribution within the β-domain region. This is opposite to its Cd2+ counterpart that demonstrated formation of a stable Cd4MT intermediate.28 In our previous research, we demonstrated an initial sequential Zn2+ binding mechanism for the α-domain forming independent ZnS4 sites and Zn3–4S9–10 clusters.31 Here, by using the presented methodology, our results support the hypothesis of multiple conformations being simultaneously present, where both populations have the full α-domain saturated, forming Zn2+ clusters (α-Zn4MT), and with redistributed Zn2+ among the α- and β-domains (Zn3αZn1βMT) coexisting in solution. Thus, it might be feasible to consider the equilibrium αZn4MT ⇌ Zn3αZn1βMT, which indicates a similar Zn2+ stability between the strongest β-site and the weakest α-site. In a previous pH-titration report, the authors reported a similar conclusion, which supports this idea.72,73 A second, alternative option is that there are multiple populations, including Zn4MT2 and Zn5MT2, coexisting simultaneously. This solution is further supported by native ESI-MS, where we observed multiple metal-loaded species coexisting. The third option includes both solutions, Zn4MT with multiple conformations, where Zn2+ ions are redistributed between both domains, and coexisting Zn4–5MT. Recently, a paper reported collision-induced unfolding experiments followed through ion mobility-MS for Zn4MT2.74 The authors reported four separate conformers with regard to collision cross section (CCS) profiles that required a different collision activation for unfolding. The β-domain is not fully extended but rather folded for Cd4MT2, as opposed to Zn4MT2, which showed a CCS of around 1000, which corresponds to the β-domain being fully extended. This may support the idea of an equilibrium, αZn4MT ⇌ Zn3αZn1βMT, that is shifted toward the formation of αZn4MT upon protein destabilization. In agreement, Stillman’s group reported that at physiological pH the four Zn2+ are bound between both domains.75 The authors suggested that the terminal Cys5 and Cys7 are involved in Zn2+ coordination. However, this idea has been supported by neither Russell’s group nor here.74,75 Russell’s group concluded that the region from Asn18 to Cys38 participates in the coordination of the first four Zn2+ ions, but the terminal Cys5 or Cys7 are at most weakly interacting. Here, with the experimental conditions employed, we suggest that the region 21–30 participates in Zn2+ binding. Despite the above differences, our results agreed and suggested that there exists a Zn2+ redistribution between both α- and β-domains.74,75

Subsequently, addition of 5 equiv of Zn2+ to apoMT2 shifted the distribution of IAM modifications, now centered at 6–7 with a maximum of 10 IAM, clearly right skewed, clumping up populations with few or no IAM modifications (Figure S16A, SI). The complementary, double-labeling distribution obtained was centered, forming the IAM7NEM13MT2 species (8067.5 m/z) (Figure S16C, SI). Interestingly, this stoichiometry does not resemble that for coordination of a single ZnCys4 site binding or a completely saturated α-cluster (Zn4S11) but rather suggests a structure with redistributed Zn2+ ions between domains.31 Moreover, a mixture of gas-phase ions with [Zn7–3IAMxMT2]5+ stoichiometry was annotated by nESI, which confirms the products IAM11NEM9MT2 (7817 m/z) and IAM3NEM17MT2 (8339 m/z) found in MALDI-MS (Figure S16B and Table S3, SI). The former one correlated with Zn3S9 stoichiometry and the latter with Zn6S17 [Zn4(Cys)11 α-domain and Zn2(Cys)6 in β-domain]. Fragments analyzed from PMF traced increased tryptic NEM1[26–31] with respect to Zn4MT, which after thorough MS/MS sequenced the NEM molecule attached to Cys29 [Figure 1B and Figure S17 (SI)]. The region 1–20 appeared with two IAM modifications for Cys5 and Cys19, so the three remaining Cys residues might be involved in coordination of the fifth Zn2+ (Figure S18, SI). Additionally, tryptic NEM5[44–61], NEM4[31–43], and NEM5[31–43] were detected and sequenced (Figures S19 and S20, SI). These results provide interesting clues concerning the binding of the fifth Zn2+. As the protein is being Zn2+ saturated, the α-domain folds to an α-Zn4S11 cluster and starts to fill the β-domain. The question arises whether a Zn2+ redistribution between domains occurs, to end up with a coordinated native-like α-cluster and a single ZnS4 site in the β-domain. It is noteworthy how the ZnS4 coordination sphere pinpointed for the single β-site does not resemble any position from the rabbit X-ray structure but perfectly matches our previous report.31 In that study, we indicated that the fifth Zn2+ probably causes conformational changes for the 1–20 and 26–31 sequence regions (Figure 1B). We might confirm that, under the conditions employed, Cys7, Cys13, Cys15, and Cys29 coordinate the fifth Zn2+ (Figure 1B). Notwithstanding, other Zn5MT2 populations are simultaneously present, as observed by IM-MS experiments, but likely with lower probability than the one described.49

A total of 6 equiv of Zn2+ added to apoMT2 caused an abrupt change of the IAM modification profile, with none to four modifications giving 1 IAM as the most intense peak (Figure S16D). Gas-phase ions detected by the nESI-MS spectrum showed the product ions [Zn7IAM0–1MT2]5+, [Zn6IAM3MT2]5+, and [Zn5IAM3–4MT2]5+ (Figure S16E and Table S4, SI). Likewise, double-labeled proteins showed that various species formed, ranging from IAM4NEM16MT to IAM0NEM20MT, the latter corresponding to Zn7MT2 (Figure S16F, SI). Precisely, we found a tryptic fragment NEM2[23–31] with NEM-labeled Cys24 and Cys29 (Figure S21). These two Cys residues were not previously found to be coordinating and their participation in Zn2+ coordination appears after addition of the 6 equiv of Zn2+. Such results match perfectly with our previous research, validating the approach presented herein.31 Addition of the last Zn2+ equivalent did not cause an observable major change for the MALDI modification profile, with the most intensive modification corresponding to one Cys residue (Figure 4B). The nESI-MS results distinguished gas-phase ions [Zn7IAM0MT2]5+ and [Zn7IAM1MT2]5+ [Figure 4A and Table S5 (SI)]. So, after removal of Zn2+, NEM labeled those Cys residues, matching with the stoichiometry obtained from MALDI-MS (Figure 4C). Interestingly, the bottom-up MS results identified the tryptic fragment NEM1[21–30] with NEM-labeled Cys21 as still existing in the spectra, confirming the gating role of Cys21 for the seventh Zn2+ previously reported [Figure 1B and Figure S22 (SI)].31

Conclusion

Cysteine is the most nucleophilic amino acid residue of all building proteins; a target for reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species and numerous chemical reactions, including post-translational ones; and critical for binding essential and toxic metal ions. To identify the chemical or redox state of Cys residues in proteins, analytical methods are based on reactions with thiol-specific probes. Among them, IAM and NEM are commonly used following an SN2 reaction and nucleophilic addition, respectively. Differential labeling coupled to mass spectrometry is used for mapping metal-binding sites. In principle, a single labeling approach should be sufficient to pinpoint Znx(Cys)y protein sites, on which the Zn2+-bound thiolate would exhibit lower reactivity toward electrophiles. However, this is not the case for low- or moderate-affinity Zn2+-binding sites, where unwanted metal ion dissociation during protein modification might occur. Moreover, a similar reactivity for a Zn2+-bound and free Cys residue with low pKa might occur, hampering their nucleophilic differentiation. Herein, we developed a dual-labeling methodology to overcome these obstacles. Our findings suggested proceeding with an SN2 reaction with IAM or a similar reagent, but not with a nucleophilic addition provided by maleimides, to label free Cys residues and avoid Zn2+ dissociation. The small size and hydrophilic character permits the labeling of free Cys residues, regardless if they are buried or not. Once the free Cys residues are labeled, metal-bound Cys might easily be labeled by a second nucleophile after extraction of the metal ion by acidification and followed by reverse-phase C18 separation. A priori, Zn2+ removal can be approached by increasing the alkylator concentration or reaction time. However, this approach does not work for high-stability metal–protein sites, and substantial overalkylation may occur. Thus, the acidification step ensures metal ion removal independent of how strongly it is bound. Not only the metal-to-protein affinity but also the thiol accessibility may limit the labeling reaction. The acidification step greatly facilitates the access of the second alkylator to all of the Cys residues, even if they were buried in the protein structure. Although any reagent different than IAM would in principle work for the second labeling reaction, NEM reacts faster than iodoacetamide derivatives with thiols/thiolates, even at low pH.

This research demonstrated how the combination of inexpensive standard labeling reagents and mass spectrometry can directly map metal-binding sites in Cys-rich proteins. Lastly, the methodology presented is very encouraging and illustrates its future use to study other metal-binding Cys proteins.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Science Centre of Poland (NCN) under the Opus grant no. 2018/31/B/NZ1/00567 (to A.K.). M.D.P.-D. thanks the Erasmus+ program and the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange under the PROM program (grant no. PPI/PRO/2018/1/00007/U/00). V.A. would like to thank to the European Research Council (ERC) for financial support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant agreement no. 759585).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01604.

Detailed materials and protocol for expression and purification of MTs; MALDI-MS spectra of Cd7MT2 and Zn7MT2, to which 15–3600 equiv of NEM or IAM had been added, after 60 min of incubation; UV–vis spectra of the metal displacement reactions after 60 min incubation with 0–3600 equiv of IAM and NEM with Cd7MT2 and Zn7MT2; ESI-MS spectra of Cd7MT2 and Zn7MT2 incubated with increasing equivalents of IAM and NEM for 60 min; ESI-MS spectra after 60 min of incubation with 750 or 1400 equiv of IAM and NEM with Cd7MT2 and Zn7MT2; number of Cys modified determined by MALDI-MS as a function of alkylator/MT ratio after 60 min incubation; peptide mass fingerprint for IAM and NEM labeling for Zn4MT2, Zn5MT2, Zn6MT2, and Zn7MT2 samples analyzed by MALDI-MS; MALDI-MS/MS analysis for the tryptic fragment of Zn0MT2, Zn4MT2, Zn5MT2, Zn6MT2, and Zn7MT2 samples; gas-phase ions annotated for Zn4MT2, Zn5MT2, Zn6MT2, and Zn7MT2 samples labeled with IAM (Figures S1–S22 and Tables S1–S5) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Andreini C.; Banci L.; Bertini I.; Rosato A. Counting the zinc-proteins encoded in the human genome. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 196–201. 10.1021/pr050361j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreini C.; Banci L.; Bertini I.; Rosato A. Zinc through the three domains of life. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 3173–3178. 10.1021/pr0603699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochańczyk T.; Drozd A.; Krężel A. Relationship between the architecture of zinc coordination and zinc binding affinity in proteins - insights into zinc regulation. Metallomics. 2015, 7, 244–257. 10.1039/C4MT00094C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W.; Li Y. Coordination dynamics of zinc in proteins. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 4682–4707. 10.1021/cr800556u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. Metals on the Move: Zinc ions in cellular regulation and in the coordination dynamics of zinc proteins. BioMetals 2011, 24, 411–418. 10.1007/s10534-010-9406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B.; Maret W.; Vallee B. L. Zinc metallothionein imported into liver mitochondria modulates respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 2317–2322. 10.1073/pnas.041619198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova M. D.; Ivanova I. A.; Cherian M. G. Metallothionein and apoptosis during differentiation of myoblasts to myotubes: protection against free radical toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999, 159, 175–184. 10.1006/taap.1999.8755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krężel A.; Maret W. The functions of metamorphic metallothioneins in zinc and copper metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1237. 10.3390/ijms18061237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blindauer C. A.; Leszczyszyn O. I. Metallothioneins: unparalleled diversity in structures and functions for metal ion homeostasis and more. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 720–741. 10.1039/b906685n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila M.; Atrian S. Metallothionein protein evolution: a miniassay. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 16, 977–989. 10.1007/s00775-011-0798-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci L.; Bertini I. In Metallomics and the Cell; Banci L., Ed.; Springer, 2013; pp 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W.Zinc and Zinc Ions in Biological Systems. In Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins; Kretsinger R. H., Uversky V. N., Permyakov E. A., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2013; p 87. [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen C. E.; Carroll K. S. Cysteine-mediated redox signaling: chemistry, biology, and tools for discovery. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 4633–4679. 10.1021/cr300163e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H. S.; Wang S.-B.; Venkatraman V.; Murray C. I.; Van Eyk J. E. Cysteine oxidative posttranslational modifications: emerging regulation in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 382–392. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Sickinger A. G.; Mörl K.. Posttranslational Modification of Proteins: Expanding Nature’s Inventory; Roberts & Co. Publishers: Englewood, CO, 2005; pp 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoo S. B.; Madder A. Chemical protein modification through cysteine. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 529–553. 10.1002/cbic.201500667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. The redox biology of redox-inert zinc ions. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2019, 134, 311–326. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krężel A.; Maret W. Zinc-buffering capacity of a eukaryotic cell at physiological pZn. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 11, 1049–1062. 10.1007/s00775-006-0150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krężel A.; Hao Q.; Maret W. Zinc/Thiolate redox biochemistry of metallothionein and the control of zinc ion fluctuations in cell signaling. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 463, 188–200. 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig A. Metal interaction with redox regulation: an integrating concept in metal carcinogenesis?. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2013, 55, 63–72. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcock L. J.; Perkins M. V.; Chalker J. M. Chemical methods for mapping cysteine oxidation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 231–268. 10.1039/C7CS00607A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalker J. M.; Bernardes G. J. L.; Lin Y. A.; Davis B. G. Chemical modification of proteins at cysteine: opportunities in chemistry and biology. Chem. - Asian J. 2009, 4, 630–640. 10.1002/asia.200800427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awoonor-Williams E.; Rowley C. N. Evaluation of methods for the calculation of the pKa of cysteine residues in proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 4662–4673. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino S. M.; Gladyshev V. N. Analysis and functional prediction of reactive cysteine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 4419–4425. 10.1074/jbc.R111.275578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojdyla K.; Rogowska-Wrzesinska A. Differential alkylation-based redox proteomics - lessons learnt. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 240–252. 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulech J.; Solis N.; Cordwell S. J. Characterization of reaction conditions providing rapid and specific cysteine alkylation for peptide-based mass spectrometry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2013, 1834, 372–379. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill B. G.; Reily C.; Oh J. Y.; Johnson M. S.; Landar A. Methods for the determination and quantification of the reactive thiol proteome. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 675–683. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. H.; Russell D. H. Reaction of human Cd7metallothionein and N-Ethylmaleimide: kinetic and structural insights from electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 2015, 54 (39), 6021–6028. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard W. R.; Vašák M.; Kägi J. H. R. Cadmium binding and metal cluster formation in metallothionein: a differential modification study. Biochemistry 1986, 25, 1975–1980. 10.1021/bi00356a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C. F.; He L.; Muñoz A.; Savas M. M.; Chi S.; Fink C. L.; Gan T.; Petering D. H. Kinetics of reversible N-Ethylmaleimide alkylation of metallothionein and the subsequent metal release. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 2, 65–73. 10.1007/s007750050107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drozd A.; Wojewska D.; Peris-Díaz M. D.; Jakimowicz P.; Krȩzel A. Crosstalk of the structural and zinc buffering properties of mammalian metallothionein-2. Metallomics 2018, 10, 595–613. 10.1039/C7MT00332C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert B.; Hayen H.; Karst U. Differential labeling of free and disulfide-bound thiol functions in proteins. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 19, 1–7. 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling B.; Yoo C. B.; Collins C. J.; Gibson B. W. Determining cysteine oxidation status using differential alkylation. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 236, 117–127. 10.1016/j.ijms.2004.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh B.; Sakellariou G. K.; Smith N. T.; Brownridge P.; Jackson M. J. Differential cysteine labeling and global label-free proteomics reveals an altered metabolic state in skeletal muscle aging. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 5008–5021. 10.1021/pr5006394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held J. M.; Danielson S. R.; Behring J. B.; Atsriku C.; Britton D. J.; Puckett R. L.; Schilling B.; Campisi J.; Benz C. C.; Gibson B. W. Targeted quantitation of site-specific cysteine oxidation in endogenous proteins using a differential alkylation and multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry approach. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2010, 9, 1400–1410. 10.1074/mcp.M900643-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerapana E.; Wang C.; Simon G. M.; Richter F.; Khare S.; Dillon M. B. D.; Bachovchin D. A.; Mowen K.; Baker D.; Cravatt B. F. Quantitative reactivity profiling predicts functional cysteines in proteomes. Nature 2010, 468, 790–797. 10.1038/nature09472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.-H.; Russell W. K.; Russell D. H. Combining chemical labeling, bottom-up and top-down ion-mobility mass spectrometry to identify metal-binding sites of partially metalated metallothionein. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 3229–3237. 10.1021/ac303522h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S.-H.; Hao Q.; Maret W. Domain-specific fluorescence resonance energy transfer (fret) sensors of metallothionein/thionein. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 2005, 18, 255–263. 10.1093/protein/gzi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potier N.; Rogniaux H.; Chevreux G.; Van Dorsselaer A. Ligand-metal ion binding to proteins: investigation by ESI mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2005, 402, 361–389. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)02011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine G. W.; Santolini M.; Stillman M. J. Selective cysteine modification of metal-free human metallothionein 1a and its isolated domain fragments: solution structural properties revealed via ESI-MS. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 960–971. 10.1002/pro.3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.-H.; Chen L.; Russell D. H. Metal-induced conformational changes of human metallothionein-2a: a combined theoretical and experimental study of metal-free and partially metalated intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9499–9508. 10.1021/ja5047878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace N. J.; Weerapana E. A competitive chemical-proteomic platform to identify zinc-binding cysteines. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 258–265. 10.1021/cb400622q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puljung M. C.; Zagotta W. N. Labeling of specific cysteines in proteins using reversible metal protection. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2513–2521. 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. M.; Lim C. Factors controlling the reactivity of zinc finger cores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8691–8703. 10.1021/ja202165x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotcher J.; Clarke D. J.; Weidt S. K.; Mackay C. L.; Hupp T. R.; Sadler P. J.; Langridge-Smith P. R. R. Identification of two reactive cysteine residues in the tumor suppressor protein p53 using top-down FTICR mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 22, 888–897. 10.1007/s13361-011-0088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopera E.; Schwerdtle T.; Hartwig A.; Bal W. Co(II) and Cd(II) substitute for zn(ii) in the zinc finger derived from the dna repair protein xpa, demonstrating a variety of potential mechanisms of toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004, 17, 1452–1458. 10.1021/tx049842s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krȩżel A.; Maret W. Dual nanomolar and picomolar zn(ii) binding properties of metallothionein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 10911–10921. 10.1021/ja071979s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto P. J.; Knipling L.; Wolff J. The local electrostatic environment determines cysteine reactivity of tubulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 29018–29027. 10.1074/jbc.M204263200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. H.; Chen L. X.; Russell D. H. Metal-induced conformational changes of human metallothionein-2a: a combined theoretical and experimental study of metal-free and partially metalated intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9499–9508. 10.1021/ja5047878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poltash M. L.; McCabe J. W.; Shirzadeh M.; Laganowsky A.; Clowers B. H.; Russell D. H. Fourier transform-ion mobility-orbitrap mass spectrometer: a next-generation instrument for native mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 10472–10478. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose R. J.; Damoc E.; Denisov E.; Makarov A.; Heck A. J. R. High-sensitivity orbitrap mass analysis of intact macromolecular assemblies. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 1084–1086. 10.1038/nmeth.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrat F. D. L.; Kowald G. R.; Scarff C. A.; Scrivens J. H.; Blindauer C. A. Resolution of a paradox by native mass spectrometry: facile occupation of all four metal binding sites in the dimeric zinc sensor SmtB. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 813–815. 10.1039/C2CC38387J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E. M.; Kondrat F. D. L.; Stewart A. J.; Scrivens J. H.; Sadler P. J.; Blindauer C. A. Native electrospray mass spectrometry approaches to probe the interaction between zinc and an anti-angiogenic peptide from histidine-rich glycoprotein. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8646. 10.1038/s41598-018-26924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel K.; Natan E.; Hall Z.; Fersht A. R.; Robinson C. V. Intrinsically disordered p53 and its complexes populate compact conformations in the gas phase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 361–365. 10.1002/anie.201203047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurneczko E.; Cruickshank F.; Porrini M.; Clarke D. J.; Campuzano I. D. G.; Morris M.; Nikolova P. V.; Barran P. E. Probing the conformational diversity of cancer-associated mutations in p53 with ion-mobility mass spectrometry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4370–4374. 10.1002/anie.201210015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt C.; Flegler V.; Ihling C. H.; Schäfer M.; Thondorf I.; Sinz A. An integrated mass spectrometry based approach to probe the structure of the full-length wild-type tetrameric p53 tumor suppressor. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 275–279. 10.1002/anie.201609826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Zúñiga C.; Leiva-Presa A.; Austin R. N.; Capdevila M.; Palacios O. Pb(Ii) binding to the brain specific mammalian metallothionein isoform MT3 and its isolated αMT3 and βMT3 domains. Metallomics 2019, 11, 349–361. 10.1039/C8MT00294K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Wojciechowski M.; Fenselau C. Assessment of metals in reconstituted metallothioneins by electrospray mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1993, 65, 1355–1359. 10.1021/ac00058a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris-Díaz M. D.; Richtera L.; Zitka O.; Krężel A.; Adam V. A chemometric-assisted voltammetric analysis of free and Zn(II)-loaded metallothionein-3 states. Bioelectrochemistry 2020, 134, 107501. 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2020.107501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza V. L.; Vachet R. W. Probing protein structure by amino acid-specific covalent labeling and mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2009, 28, 785–815. 10.1002/mas.20203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.; Weisbrod C. R.; Marshall A. G. Protein de novo sequencing by top-down and middle-down ms/ms: limitations imposed by mass measurement accuracy and gaps in sequence coverage. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 427, 107–113. 10.1016/j.ijms.2017.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powlowski J.; Sahlman L. Reactivity of the two essential cysteine residues of the periplasmic mercuric ion-binding protein, MerP. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 33320–33326. 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorska M.; Krężel A.; Otlewski J. Femtomolar Zn2+ affinity of lim domain of pdlim1 protein uncovers crucial contribution of protein-protein interactions to protein stability. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 115, 28–35. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanczyk T.; Nowakowski M.; Wojewska D.; Kocyla A.; Ejchart A.; Kozminski W.; Krężel A. Metal-coupled folding as the driving force for the extreme stability of Rad50 zinc hook dimer assembly. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36346. 10.1038/srep36346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocyła A.; Pomorski A.; Krężel A. Molar absorption coefficients and stability constants of zincon metal complexes for determination of metal ions and bioinorganic applications. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 176, 53–65. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocyła A.; Pomorski A.; Krężel A. Molar absorption coefficients and stability constants of metal complexes of 4-(2-Pyridylazo)Resorcinol (PAR): revisiting common chelating probe for the study of metalloproteins. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 152, 82–92. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suckau D.; Resemann A.; Schuerenberg M.; Hufnagel P.; Franzen J.; Holle A. A novel MALDI LIFT-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer for proteomics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 376, 952–965. 10.1007/s00216-003-2057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiari M.; Konermann L. Protein ions generated by native electrospray ionization: comparison of gas phase, solution, and crystal structures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 1784–1796. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann L. Addressing a common misconception: ammonium acetate as neutral pH “buffer” for native electrospray mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 28, 1827–1835. 10.1007/s13361-017-1739-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z.; Degrandchamp J. B.; Williams E. R. Native mass spectrometry beyond ammonium acetate: effects of nonvolatile salts on protein stability and structure. Analyst 2019, 144, 2565–2573. 10.1039/C9AN00266A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susa A. C.; Xia Z.; Williams E. R. Small emitter tips for native mass spectrometry of proteins and protein complexes from nonvolatile buffers that mimic the intracellular environment. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 3116–3122. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasak M.; Kagi J. H. R.; Hill H. A. O. Zinc(II), Cadmium(II), and Mercury(II) thiolate transitions in metallothionein. Biochemistry 1981, 20, 2852–2856. 10.1021/bi00513a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. H.; Toyama M.; Maret W.; Murooka Y. High yield expression and single step purification of human thionein/metallothionen. Protein Expression Purif. 2001, 21, 243–250. 10.1006/prep.2000.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S.; Wagner N. D.; Russell D. H. Collision-induced unfolding of partially metalated metallothionein-2a: tracking unfolding reactions of gas-phase ions. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 11856–11862. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b01622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine G. W.; Pinter T. B. J.; Stillman M. J. Defining the metal binding pathways of human metallothionein 1a: balancing zinc availability and cadmium seclusion. Metallomics 2016, 8, 71–81. 10.1039/C5MT00225G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.