Abstract

The study of nonenzymatic template-directed RNA copying is the experimental basis for the search for chemistry and reaction conditions consistent with prebiotic RNA replication. The most effective model systems for RNA copying have to date required a high concentration of Mg2+. Recently, Fe2+, which was abundant on the prebiotic anoxic Earth, was shown to promote the folding of RNA in a manner similar to the case of Mg2+, as a result of the two cations having similar interactions with phosphate groups. These observations raise the question of whether Fe2+ could have promoted RNA copying on the prebiotic Earth. Here, we demonstrate that Fe2+ is a better catalyst and promotes faster nonenzymatic RNA primer extension and ligation than Mg2+ when using 2-methylimidazole activated nucleotides in slightly acidic to neutral pH solutions. Thus, it appears likely that Fe2+ could have facilitated RNA replication and evolution in concert with other metal cations on the prebiotic Earth.

Introduction

The emergence of self-replicating RNA in the absence of complex enzymatic machinery was a key event in the origin of life. The search for environmental conditions and chemistry that could have enabled nonenzymatic RNA replication is a long-standing challenge in the field of prebiotic chemistry. Known nonenzymatic RNA copying chemistries require a high concentration of Mg2+, typically 50–200 mM.1 However, such high concentrations of Mg2+ are problematic because Mg2+ also catalyzes the degradation of RNA and the hydrolysis of activated nucleotides and oligonucleotides, and in addition it is unclear whether environments containing such high levels of Mg2+ are geochemically realistic. These considerations make it important to examine potential alternatives to Mg2+, which might provide superior catalytic function, possibly at lower metal ion concentrations, and which might be more geochemically plausible.

It is well established that the atmosphere of the early Earth was essentially oxygen-free;2 in addition, aqueous environments buffered by equilibration with the high levels of atmospheric CO2 on the early Earth would have been slightly acidic to neutral.3,4 Together, these factors would have allowed for the existence of high concentrations of soluble ferrous iron in at least some local aqueous environments such as ponds or lakes. The best modern Earth analogs of such environments may be the deep anoxic ferruginous layers of permanently stratified lakes, some of which contain Fe2+ at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 mM.5−9 Fe2+ possesses the same charge and similar ionic radius as Mg2+,10 and it has proven to function well as a substitute for Mg2+ in RNA folding and catalysis if acidic or neutral pH and anoxic conditions are maintained.11,12 Computational studies have shown that the conformations of the RNA-Mg2+ and RNA-Fe2+ clamps in the L1 ribozyme ligase are nearly identical. Furthermore, the L1 ribozyme ligase and the hammerhead ribozyme retain catalytic function in solution conditions where Fe2+ is the only divalent cation present. Inspired by these findings, we asked whether Fe2+ could also promote nonenzymatic RNA copying. Here, we show that Fe2+ can substitute for Mg2+ in such reactions, especially in anoxic aqueous environments near neutral pH.

Results

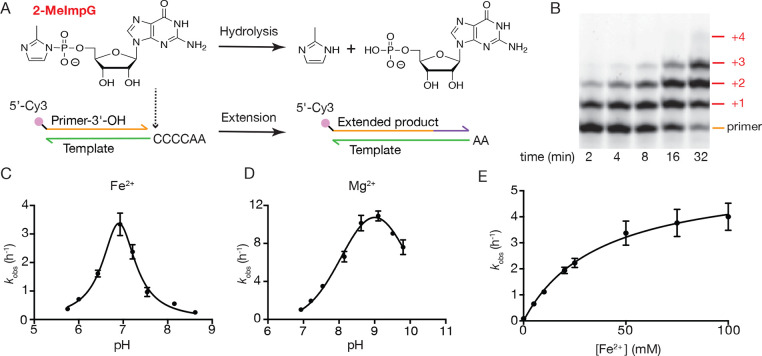

Dissolved ferrous iron Fe2+ is readily oxidized to ferric iron Fe3+, and this reaction is particularly rapid in alkaline solutions. As expected, Fe3+ had no catalytic effect (Figure S1) because Fe3+ is known to complex very strongly with phosphate and leads to precipitation of RNA and activated monomer hydrolysis.13 Therefore, to study the catalytic effect of Fe2+ on a template-directed nonenzymatic RNA primer extension, we performed all experiments inside an oxygen-free glovebox with thoroughly degassed reagents (for details see the Supporting Information). We measured the pseudo-first-order observed rate kobs of conversion of primer to extended products on a template with a 3′-CCCCAA-5′ overhang (Figure 1A), using a large excess of 2-MeImpG (50 mM) in the presence of either Fe2+ or Mg2+. Since the pKa of aqueous Fe2+ (9.4) is approximately 2 units lower than that of Mg2+ (11.4),14 we examined the effect of pH on catalysis and plotted the pH–rate profile (Figure 1B–D, Figure S2). The reaction pH was measured after the reaction was complete. From pH 5.0 to 8.5, primer extension products accumulated in the presence of Fe2+. We observed the highest reaction rate at a pH of ca. 7, with more than 90% primer extended to primer+1 (or greater) within 30 min. Mg2+-containing reactions, in contrast, exhibited the highest rate of primer extension under more basic conditions; at a pH of ca. 9, nonenzymatic primer extension proceeded at 3.2 times the rate of Fe2+-containing reactions at pH 7. Notably, Mg2+-containing reactions exhibited significantly slower primer extension than those containing Fe2+ at neutral pH, with Fe2+-containing reactions proceeding 3.3 times faster than those containing Mg2+ at pH 7.

Figure 1.

Characterization of nonenzymatic RNA primer extension in the presence of Fe2+. (A) Structure of the activated monomer 2-MeImpG, and schematic diagram of the hydrolysis and primer extension reactions. (B) Representative electropherogram showing time course of primer extension (2.5 μM standard primer, 5 μM 4C template, 50 mM 2-MeImpG) in the presence of 50 mM 2-MeImpG, 50 mM Fe2+, and 250 mM pH 6.5 Bis-Tris Propane (BTP) buffer. (C, D) Primer extension rate vs pH profiles for 50 mM Fe2+ (n = 4) and 50 mM Mg2+ (n = 5); error bars represent SEM. Reaction pH was measured after reaction and averaged. Curves were fitted in Gaussian. (E) Saturation curve of Fe2+ catalyzed primer extension using 50 mM 2-MeImpG as substrate in 250 mM BTP buffer pH 6.5. Data were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation for enzyme kinetics with kmax = 5.6 ± 0.2 h–1, Km = 37 ± 3 mM, n = 3; error bars represent SEM.

Our laboratory has recently shown that 2-aminoimidazole (2-AI) activated nucleotides significantly accelerate nonenzymatic primer extension, relative to the rates typically observed with 2-methylimidazole activated monomers.15 This enhanced template copying is thought to be due in part to the formation of a more stable imidazolium-bridged dinucleotide intermediate, which accumulates to higher levels and therefore leads to faster primer extension. When we used Fe2+ to catalyze primer extension with 2-AIpG, we observed the formation of a white precipitate in all pH conditions tested, which apparently results from an interaction between ferrous ions and 2-AI activated monomers and possibly also the 2-aminoimidazolium-bridged intermediate. Despite the observed precipitation, and thus presumably lower actual concentration of dissolved monomer and intermediate, the kobs still reached 6.3 h–1 at the optimal pH of 7.5 (Figure S3). This pH optimum was slightly higher than that of primer extension driven by 2-methylimidazole activated monomers, most likely due to the higher pKa of the 2-aminoimidazole group. However, other factors such as the possible pH dependence of the dissolved monomer and/or intermediate concentration could also affect the pH optimum of the reaction.

Because high concentrations of divalent ions have a variety of deleterious effects ranging from the catalysis of RNA degradation16 and the hydrolysis of activated monomers17 to the disruption of fatty acid based membranes,18 we wished to determine the concentrations of Fe2+ needed for effective catalysis of RNA template copying. We therefore performed template-directed nonenzymatic RNA primer extension using 2-methylimidazole activated G and the same C4 template described above, at various Fe2+ concentrations at neutral pH. We fit the reaction rate vs Fe2+ concentration data to a Michaelis–Menten kinetic model, assuming that Fe2+ ions would be in rapid equilibrium with the primer/template intermediate complex, and that initial concentrations of monomer would not change significantly during the course of the reaction (Figure 1E, Figure S4). The kmax obtained was 5.6 ± 0.2 h–1, and the apparent Km for Fe2+ was 37 ± 3 mM (however, this value may be low because at higher Fe2+ concentrations the monomer degrades rapidly). To compare the catalytic effects of Fe2+ and Mg2+ at low metal ion concentrations, we analyzed the primer extension results at 0.1, 1, or 5 mM of Fe2+ and Mg2+, respectively, and found that primer extension in the presence of 1 and 5 mM Fe2+ yielded significantly more extended products than when using Mg2+ for catalysis (Figure S5). Interestingly, at pH 9, the optimum pH for Mg2+ catalyzed primer extension, the yield of extended products with 5 mM Mg2+ was only half of that obtained in the presence of 5 mM Fe2+ at neutral pH.

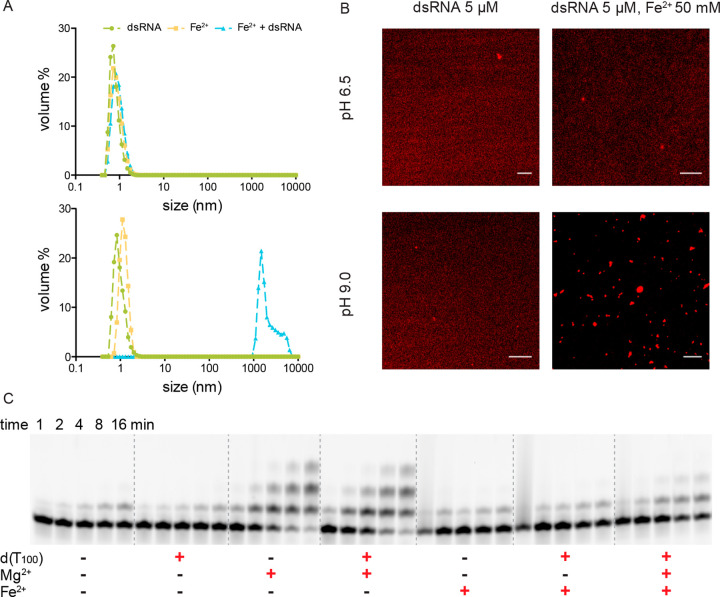

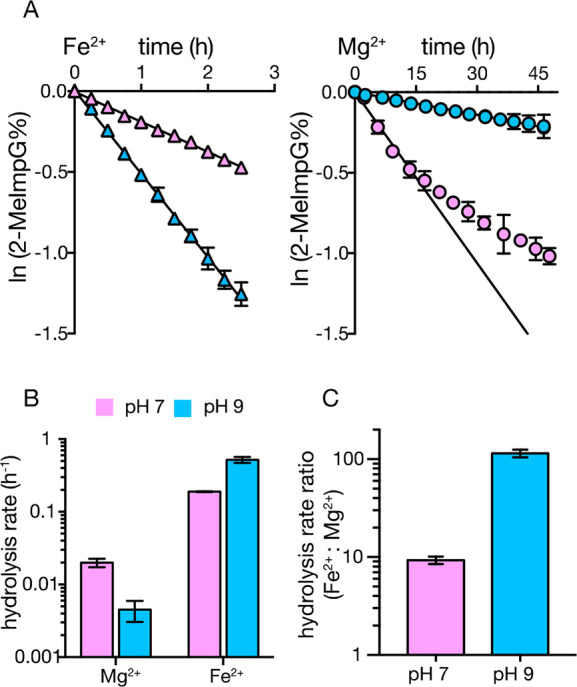

In the presence of divalent cations such as Mg2+, nucleotide phosphoroimidazolides are hydrolyzed into nucleotide monophosphates (Figure 1A), which are unreactive monomers that both competitively inhibit primer extension and react with activated monomers to generate pyrophosphate linked dinucleotides, which also inhibit primer extension.17 Hence, we determined the rate of hydrolysis of 2-MeImpG in the presence of 50 mM Mg2+ and Fe2+ using an HPLC assay, under the optimum pH values for primer extension for both Mg2+ or Fe2+ (Figure 2A). We found that 2-MeImpG hydrolyzed 10 times faster in the presence of Fe2+ than Mg2+ at neutral pH and over 100-fold faster at pH 9 (Figure 2B, 2C). The very rapid Fe2+-promoted hydrolysis of 2-MeImpG at high pH may explain the limited yield of extended primer products at pH 9, due to depletion of 2-MeImpG. Even at neutral pH, the relatively rapid rate of monomer hydrolysis in the presence of 50 mM Fe2+, corresponding to a half-life of ∼3 h, suggests that high Fe2+ concentrations would be problematic for RNA replication efficiency.

Figure 2.

Rate of hydrolysis of 2-MeImpG as a function of pH in the presence of Fe2+ and Mg2+. (A) Plot of the hydrolysis of 2-MeImpG measured by HPLC with 50 mM Fe2+ (Δ) or 50 mM Mg2+ (○) in either high pH (pH 9.0, blue fill) or neutral pH (pH 7.0, pink fill). The natural logarithm of the fraction of activated 2-MeImpG remaining after increasing times was fit to a line, and the slope yielded the pseudo-first-order rate constants (B). The ratio of rates for Fe2+ vs Mg2+ is plotted in (C). n = 3, error bars represent SEM. *Note that Mg2+ catalysis at low pH appears biphasic, possibly due to changing reaction conditions with time. We therefore used only the earliest 4 time points to calculate the initial rate.

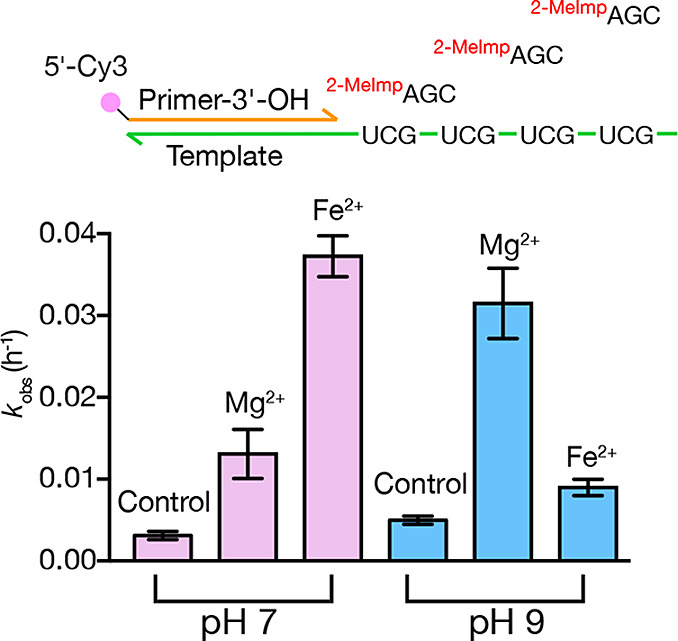

Prebiotic RNA template copying could in principle be achieved by either monomer polymerization or through ligation of RNA fragments. Template-directed nonenzymatic RNA ligation has been previously demonstrated using activated oligonucleotide substrates with Mg2+ as the catalytic metal ion.19 In order to compare the catalytic effects of Fe2+ and Mg2+ on RNA ligation, we examined the sequential ligation of 2-methylimidazole activated RNA trinucleotides to an RNA primer annealed to a complementary RNA template. Consistent with the primer extension reaction results, Fe2+ catalyzed the ligation reaction at neutral pH at a rate (0.037 h–1) that was about 3-fold higher than the rate observed for the otherwise identical Mg2+-catalyzed reaction (0.013 h–1) (Figure 3, Figure S6). In contrast with nonenzymatic primer extension with monomers, where the rate with Mg2+ at high pH was much faster than that with Fe2+ at neutral pH, ligation in the presence of Mg2+ was faster at pH 9 (0.031 h–1) than at pH 7, but was still slower than that catalyzed by Fe2+ at neutral pH. As expected, all ligation rates were much slower than helper-assisted monomer addition, because monomer addition proceeds through a highly preorganized imidazolium-bridged intermediate. Ligation is slower, as there is no conformational preorganization to favor the in-line displacement reaction and expulsion of the protonated imidazole leaving group. The similar 3-fold rate enhancement of Fe2+ over Mg2+ at neutral pH suggests a similar mechanism of action for both metal ions in both reactions, possibly involving metal-assisted deprotonation of the primer 3′-hydroxyl and/or electrophilic activation of the phosphate and/or a bridging interaction that brings the hydroxyl and phosphate physically closer together.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of nonenzymatic RNA ligation in the presence of Mg2+ and Fe2+. (Top) Schematic of template-directed RNA ligation of Cy3-labeled primer to 2-methylimidazole-activated trimer. (Bottom) Rates of conversion of primer to extended products by ligation to trimers, at either pH 7 or pH 9, and with no divalent cations, 50 mM Mg2+ or 50 mM Fe2+, n = 3; error bars represent SEM. Reaction conditions: 2.5 μM standard primer, 5 μM UGC repeat template, 10 mM 2-MeImpACG, 250 mM BTP buffer.

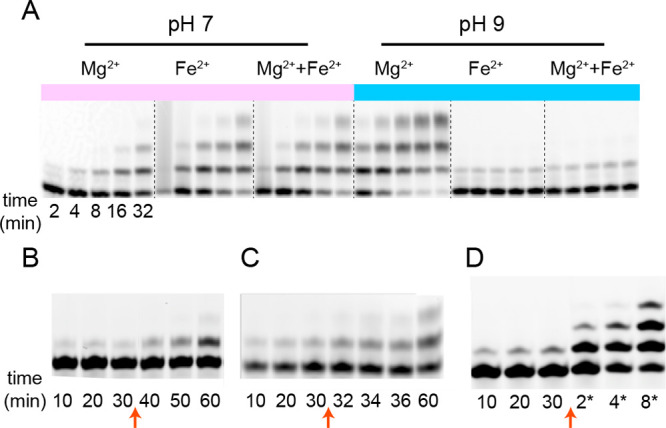

As described above, Fe2+-catalyzed nonenzymatic RNA primer extension exhibits a pH optimum near neutrality, while the Mg2+ catalyzed reaction exhibits a higher pH optimum. This led us to ask whether Mg2+ and Fe2+ could act synergistically to catalyze primer extension at a high rate over a wide pH range. We performed the polymerization reaction with 50 mM of each divalent cation at pH 7 and at pH 9 and compared the result with control reactions containing 50 mM of Mg2+ only, or 50 mM of Fe2+ only, at each pH. As expected, at neutral pH, Mg2+ had very little additive catalytic effect when compared to the control with only Fe2+ (Figure 4A). More surprising was that, at high pH, Fe2+ strongly inhibited Mg2+ catalyzed primer extension. Interestingly, this inhibition was reversible after 30 min of incubation of the RNA with Fe2+ at high pH, and the RNA polymerization reaction could be reinitiated either by dropping the pH to 7 or by removing the Fe2+ by adding EDTA, which exhibits 5–6 orders of magnitude higher binding affinity for Fe2+ than Mg2+ (Figure 4B–D). Thus, the Fe2+-induced inhibition at high pH was not due to irreversible damage to the RNA structure.

Figure 4.

Reversible inhibition of primer extension by Fe2+ at high pH. (A) Electropherograms of nonenzymatic primer extension with (left to right) 50 mM Mg2+, 50 mM Fe2+, or 50 mM of both cations, at pH 7 or pH 9, time points in each group: 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 min. (B, C, and D) Nonenzymatic primer extension started with 50 mM Mg2+ and 50 mM Fe2+ at pH 9 for 30 min, then either adjusted to pH 7 by addition of HCl (B, red arrow), or added 55 mM EDTA at pH 9 (C, red arrow), or ethanol precipitated and resuspended with 50 mM Mg2+ and fresh monomer at pH 7 (D, red arrow) with new time points taken at 2, 4, 8 min.

We investigated the mechanism of the inhibition of the polymerization reaction by Fe2+ at high pH, because if it was possible to prevent this inhibition, Fe2+ could potentially provide better catalysis of primer extension than Mg2+, due to the lower pKa of the Fe2+ coordinated water molecules. We first asked whether the inhibition was due to the binding of ferrous ions to a specific site on either RNA oligonucleotides or monomers at higher pH. Two potential sites for such interactions are the cis-diol of the primer and N7 of guanine. We therefore compared the rate of template-directed primer extension, using a primer with a 3′-terminal 2′-deoxy-nucleotide, in the presence of either or both Mg2+ and Fe2+ in pH 6.5 and 9.0 buffer (Figure S8). The rate of primer extension was somewhat lower compared to that previously observed for a primer with a 3′-terminal ribonucleotide, as expected. However, the Fe2+ inhibition of Mg2+ catalyzed primer extension at high pH was not alleviated, suggesting that the inhibitory effect does not arise from coordination of Fe2+ to the cis-diol of the primer. We also examined the possibility that Fe2+ binding to the N7 of guanine nucleobases in the template might interfere with template copying. We therefore synthesized a template oligonucleotide with the same sequence as used for all previous experiments described above, except with the G4 template region replaced with four 7-deazaguanine residues. Surprisingly, primer extension in the presence of 50 mM 2MeImpC was very slow under all conditions (Mg2+ or Fe2+, low or high pH). Nevertheless the inhibition of primer extension by Fe2+ at high pH remained complete with this template, suggesting that Fe2+ binding to template guanine-N7 cannot account for the inhibitory effect (Figure S9). Finally, we examined the possibility that the nonspecific binding of hydrated Fe2+ ions to the RNA backbone might cause a conformational change that prevents template-directed primer extension from proceeding. We used cobalt hexammine to attempt to compete with such interactions, because Co(NH3)63+ is known to bind tightly to nucleic acids through outer shell interactions.20 However, the addition of cobalt hexammine did not affect the Fe2+ inhibition at high pH; indeed, Fe2+ abolished the modest degree of primer extension observed in the presence of cobalt hexammine alone (Figure S10).

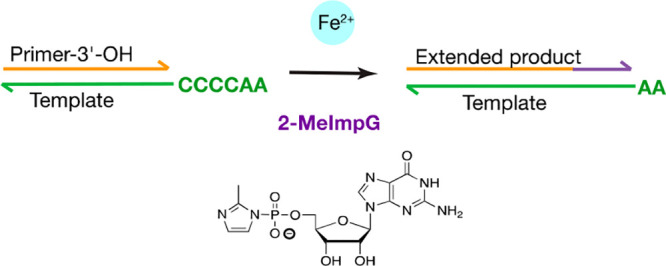

Aqueous Fe2+ is well-known to hydrolyze under alkaline conditions, generating poorly soluble or insoluble species such as Fe(OH)+ and Fe(OH)2.21 However, we did not observe visible precipitation of insoluble ferrous hydroxides during primer extension reactions and, therefore, did not initially favor the hypothesis that such complexes might be responsible for the inhibition of template-directed primer extension. Nevertheless, since the RNA backbone is negatively charged, we wondered if the observed high pH inhibition could be due to indiscriminate electrostatic interaction between heterogeneous cationic ferrous hydroxide complexes and RNA primer–template complexes, which might form microscopic aggregates in solution. When we used dynamic light scattering (DLS) to search for such complexes, we observed micron-sized particles forming in solutions containing Fe2+ and the RNA duplex at pH 9, but not at pH 6.5 (Figure 5A). This result was further confirmed by confocal microscopy (Figure 5B). At pH 6.5, 5′-Cy3-labeled RNA primer template complexes dissolved in an Fe2+-containing solution remained homogeneous, while at pH 9.0 we observed aggregation of the fluorescently labeled RNA into micron-sized particles. We then attempted to out-compete this presumed electrostatic interaction by adding an excess of a longer oligonucleotide. When we added a DNA oligonucleotide d(T100) to the primer extension reaction, such that the total amount of negative charge associated with this oligonucleotide was 100-fold higher than that associated with the RNA primer–template complex, the Mg2+ catalyzed reaction was not affected, while the Fe2+ inhibition was slightly alleviated at pH 8.5 (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

RNA aggregation in the presence of Fe2+ at high pH. (A) Volume size distribution as measured by dynamic light scattering, of 5 μM double stranded RNA, 50 mM Fe2+, or a mix of both in 250 mM BTP buffer (pH 6.5, top panel; pH 9.0 bottom panel). (B) Confocal microscopy images of pure Cy3 labeled RNA primer template complex without (left) or with (right) Fe2+ at low and high pH. Scale bar: 5 μm. (C) Electropherograms of primer extension products at pH 8.5 with or without adding DNA oligonucleotide d(T100). Reaction conditions: 0.5 μM standard primer, 1 μM 4C template, 50 mM 2-MeImpG in 250 mM buffer; 50 mM of each divalent cations if added; 30 μM d(T100) if added.

Discussion

We have assessed the catalytic activity of Fe2+ as a substitute of Mg2+ for nonenzymatic template-directed RNA primer extension. Both Fe2+ and Mg2+ form octahedral hexa-aquo hydrated species in water at pH near neutrality, but the pKa of the hydrated Fe2+ ion is approximately two units lower than that of Mg2+ (9.4 vs ∼11.4). Consequently, at more alkaline pH values near pH 9, ferrous ion solutions contain significant levels of Fe(OH)+, which is much less soluble; at higher pH values Fe(OH)2 forms, which is insoluble in water. At pH 9, the equilibrium solubility of total ferrous ion species is <0.1 mM.22 We suggest that the ionization and solubility properties of dissolved Fe2+ explain the differing properties of Fe2+ vs Mg2+ as a catalyst of RNA primer extension. At neutral pH, the hydrated Fe2+ ion is likely to interact with RNA in a similar manner as Mg2+, as previously discussed by Hud and Williams.12 Exchange reactions may lead to inner sphere coordination with the 3′-hydroxyl of the primer, facilitating deprotonation of the hydroxyl and therefore its activation as a nucleophile. This effect most likely accounts for the ∼3-fold increase in the rate of primer extension at pH 7 with Fe2+ as the catalytic metal vs Mg2+. The relatively modest observed rate increase could result from any of a number of effects, such as differences in the precise coordination geometry, or differences in the simultaneous electrophilic activation of the reactive phosphate of the incoming nucleotide. It is interesting to note that the similarly large change in the pKa of the 3′-hydroxyl of the primer, when the primer ends in a ribonucleotide vs a 2′-deoxynucleotide (pKa of ∼12 vs 15), also has a relatively small effect on the rate of primer extension (Figure S8). One possibility is that the transition state of the reaction involves a small degree of bond formation with the attacking nucleophile. However, the actual mechanism of the primer extension reaction is kinetically complex, and additional experimental work will be required to fully explain these observations.

At high pH (pH of ∼9), Fe2+ becomes a strong inhibitor of the primer extension reaction. This appears to be due to the formation of insoluble precipitates, which bind the RNA primer–template complexes, forming microscopically visible particles. In this form, the RNA is unable to participate in primer extension reactions for unknown reasons; the conformation of the bound RNA could be altered, or the reactive site could be sterically occluded and unavailable for binding of the monomer substrate or imidazolium-bridged dinucleotide intermediate. At least after short periods of time, these insoluble complexes can be dissolved, by either lowering the pH or complexing the Fe2+ with EDTA, both of which restore the ability of the RNA to participate in primer extension chemistry. It will be interesting to see if complexation of the metal ion with an appropriate chelator could prevent precipitation at elevated pH, while maintaining correct interaction with the RNA reaction center. If this is possible, much higher rates of primer extension and possibly more extensive template copying might be achievable.

Fe2+ salts are highly soluble in water at slightly acidic to neutral pH. Such aqueous environments are thought to have been common on the early Earth, due to equilibration with much higher levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Because the early Earth was anoxic, ferrous iron could have accumulated to relatively high concentrations in surface waters, limited by precipitation of FeCO3 as the ferrous iron carbonate mineral siderite. Our findings suggest that Fe2+ could have promoted RNA copying in neutral or mildly acidic aqueous environments, where it would have been a better catalyst of primer extension than dissolved Mg2+. It is thought that, during the subsequent evolution of primitive life, nonenzymatic RNA copying may have first been replaced with ribozyme catalyzed copying, and then finally by protein-based RNA and DNA polymerases. These enzymes may have evolved to use Fe2+ first and subsequently adapted to be able to use either Fe2+ or Mg2+ as life spread into different environments. Later in Earth’s history, around the time of the Great Oxidation Event when atmospheric levels of oxygen became significant, levels of ferrous iron in surface oxic waters declined drastically, as a result of oxidation to ferric iron which forms highly insoluble oxyhydroxide complexes even at neutral or mildly acidic pH. As soluble iron levels declined, and the uptake of iron became ever more metabolically expensive, life would have had to adapt by replacing Fe2+ with the more readily available Mg2+ ion wherever possible, and especially for RNA chemistry.

Acknowledgments

J.W.S. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation [CHE-1607034] and the Simons Foundation [290363] to J.W.S. The authors thank Dr. Ayan Pal and Dr. Anders Bjorkbom for glovebox installation and maintenance. The authors also thank Dr. Chun-Pong Tam, Dr. Claudia Bonfio, Dr. Neha P. Kamat, and Dr. David C. Catling for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b09617.

All experimental materials, methods, supplementary figures S1–S10, and additional references (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Szostak J. W. The Eightfold Path to Non-Enzymatic RNA Replication. J. Syst. Chem. 2012, 3, 2. 10.1186/1759-2208-3-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D. E. The Early History of Atmospheric Oxygen: Homage to Robert M. Garrels. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2005, 33, 1–36. 10.1146/annurev.earth.33.092203.122711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy I.; Bachan A. The Geologic History of Seawater pH. Science 2017, 355, 1069–1071. 10.1126/science.aal4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep N. H.; Zahnle K. Carbon Dioxide Cycling and Implications for Climate on Ancient Earth. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2001, 106, 1373–1399. 10.1029/2000JE001247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard A.; Symonds R. B. The Significance of Siderite in the Sediments from Lake Nyos, Cameroon. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1989, 39, 187–194. 10.1016/0377-0273(89)90057-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michard G.; Viollier E.; Jézéquel D.; Sarazin G. Geochemical Study of a Crater Lake: Pavin Lake, France — Identification, Location and Quantification of the Chemical Reactions in the Lake. Chem. Geol. 1994, 115, 103–115. 10.1016/0009-2541(94)90147-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakabe M.; Tanyileke G.; McCord S.; Schladow S. Recent pH and CO2 Profiles at Lakes Nyos and Monoun, Cameroon: Implications for the Degassing Strategy and Its Numerical Simulation. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2000, 97, 241–260. 10.1016/S0377-0273(99)00170-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busigny V.; Planavsky N. J.; Jézéquel D.; Crowe S.; Louvat P.; Moureau J.; Viollier E.; Lyons T. W. Iron Isotopes in an Archean Ocean Analogue. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 133, 443–462. 10.1016/j.gca.2014.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bravidor J.; Kreling J.; Lorke A.; Koschorreck M. Effect of Fluctuating Oxygen Concentration on Iron Oxidation at the Pelagic Ferrocline of a Meromictic Lake. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 723. 10.1071/EN14215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon R. D. IUCr. Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Cryst. Phys., Diffr., Theor. Gen. Crystallogr. 1976, 32, 751–767. 10.1107/S0567739476001551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C.; Chou I.; Okafor C. D.; Bowman J. C.; O'Neill E. B. O.; Athavale S. S.; Petrov A. S.; Hud N. V.; Wartell R. M.; Harvey S. C.; et al. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 525–528. 10.1038/nchem.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athavale S. S.; Petrov A. S.; Hsiao C.; Watkins D.; Prickett C. D.; Gossett J. J.; Lie L.; Bowman J. C.; O’Neill E.; Bernier C. R.; et al. RNA Folding and Catalysis Mediated by Iron (II). PLoS One 2012, 7, e38024. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Roode J. H. G.; Orgel L. E. Template-Directed Synthesis of Oligoguanylates in the Presence of Metal Ions. J. Mol. Biol. 1980, 144, 579–585. 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson V. E.; Felmy A. R.; Dixon D. A. Prediction of the P Ka ’s of Aqueous Metal Ion + 2 Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 2926–2939. 10.1021/jp5118272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Prywes N.; Tam C. P.; O'Flaherty D. K.; Lelyveld V. S.; Izgu E. C.; Pal A.; Szostak J. W. Enhanced Nonenzymatic RNA Copying with 2-Aminoimidazole Activated Nucleotides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1810–1813. 10.1021/jacs.6b13148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barshevskaia T. N.; Goriunova L. E.; Bibilashvili R. S. Non-Specific RNA Degradation in the Presence of Magnesium Ions. Mol. Biol. (Mosk). 1987, 21, 1235–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanavarioti A.; Bernasconi C. F.; Doodokyan D. L.; Alberas D. J. A Magnesium Ion Catalyzed P-N Bond Hydrolysis in Imidazolide-Activated Nucleotides. Relevance to Template-Directed Synthesis of Polynucleotides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7247–7257. 10.1021/ja00200a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I. A.; Salehi-Ashtiani K.; Szostak J. W. RNA Catalysis in Model Protocell Vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13213–13219. 10.1021/ja051784p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prywes N.; Blain J. C.; Del Frate F.; Szostak J. W. Nonenzymatic Copying of RNA Templates Containing All Four Letters Is Catalyzed by Activated Oligonucleotides. eLife 2016, 5, 1–14. 10.7554/eLife.17756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong B.; Chen J.-H.; Bevilacqua P. C.; Golden B. L.; Carey P. R. Competition between Co(NH(3)(6)3+ and Inner Sphere Mg2+ Ions in the HDV Ribozyme. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 11961–11970. 10.1021/bi901091v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayer K. H.; Woontner L. The Solubility of Ferrous Hydroxide and Ferric Hydroxide in Acidic and Basic Media at 25°. J. Phys. Chem. 1956, 60, 1569–1571. 10.1021/j150545a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singer P. C.; Stumm W. The Solubility of Ferrous Iron in Carbonate Bearing Waters. J. - Am. Water Works Assoc. 1970, 62, 198–202. 10.1002/j.1551-8833.1970.tb03888.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.