Abstract

Introduction

The objective of this study was to examine changes in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), anti-diabetic medication use, insulin resistance, and other ambulatory glucose profile metrics between baseline and after 90 days of participation in the Twin Precision Nutrition (TPN) Program enabled by Digital Twin Technology.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients with type 2 diabetes who participated in the TPN Program and had at least 3 months of follow-up. The TPN machine learning algorithm used daily continuous glucose monitor (CGM) and food intake data to provide guidelines that would enable individual patients to avoid foods that cause blood glucose spikes and to replace them with foods that do not produce spikes. Physicians with access to daily CGM data titrated medications and monitored patient conditions.

Results

Of the 89 patients who initially enrolled in the TPN Program, 64 patients remained in the program and adhered to it for at least 90 days; all analyses were performed on these 64 patients. At the 90-day follow-up assessment, mean (± standard deviation) HbA1c had decreased from 8.8 ± 2.2% at baseline by 1.9 to 6.9 ± 1.1%, mean weight had decreased from 79.0 ± 16.2 kg at baseline to 74.2 ± 14.7 kg, and mean fasting blood glucose had fallen from 151.2 ± 45.0 mg/dl at baseline to 129.1 ± 36.7 mg/dl. Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) had decreased by 56.9% from 7.4 ± 3.5 to 3.2 ± 2.8. At the 90-day follow-up assessment, all 12 patients who were on insulin had stopped taking this medication; 38 of the 56 patients taking metformin had stopped metformin; 26 of the 28 patients on dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors discontinued DPP-4 inhibitors; all 13 patients on alpha-glucosidase inhibitors discontinued these inhibitors; all 34 patients on sulfonylureas were able to stop taking these medications; two patients stopped taking pioglitazone; all ten patients on sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors stopped taking SGLT2 inhibitors; and one patient stopped taking glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues.

Conclusion

The results provide evidence that daily precision nutrition guidance based on CGM, food intake data, and machine learning algorithms can benefit patients with type 2 diabetes. Adherence for 3 months to the TPN Program resulted in patients achieving a 1.9 percentage point decrease in HbA1c, a 6.1% drop in weight, a 56.9% reduction in HOMA-IR, a significant decline in glucose time below range, and, in most patients, the elimination of diabetes medication use.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Continuous glucose monitoring, Diabetes medication elimination, Digital twin technology, HbA1c reduction, Precision nutrition, Type 2 diabetes

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Typical disease progression of type 2 diabetes (T2D) leads to increases in glucose-lowering medication use, healthcare costs, and complications. |

| The objective of this retrospective study was to assess changes in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), anti-diabetic medication use, insulin resistance, and other metrics between baseline and after 90 days of participation by patients with T2D in the Twin Precision Nutrition (TPN) Program powered by continuous glucose monitoring and artificial intelligence algorithms. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Patients who adhered to the TPN Program for 3 months achieved a 1.9 percentage point decrease in HbA1c, a 56.9% reduction in HOMA-IR, a 6.1% drop in weight, a significant decline in glucose time below range, and, in most patients, the elimination of diabetes medication use. |

| The significant improvements in a wide array of diabetes-related metrics provide evidence that adherence to a well-tolerated continuous glucose monitoring system and an artificial intelligence-driven precision nutrition program can reverse diabetes symptoms. |

| Future randomized controlled trials may provide additional evidence. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12943226.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a chronic disease that has typically been thought of as incurable. Often the best outcome hoped for is improvement in the disease’s symptoms and slowing of its progression [1]. Typically, disease progression leads to increases in glucose-lowering medication use, healthcare costs, and complications [2]. The 2016 World Health Organization global report on diabetes acknowledged that diabetes reversal is possible through weight loss and reduced calorie intake [3]. Although specific criteria have not been finalized, it is commonly accepted that maintaining hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) below 6.5% for an extended period of time without the use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications (with the possible exception of metformin) would be considered diabetes reversal or remission [1, 4].

Various studies have shown reductions in weight and improvements in glycemic control using bariatric surgery, low-calorie diets, or carbohydrate restriction [1, 5]. Limitations that may hinder the use of bariatric surgery include the high cost of surgery and an increased likelihood of adverse events [1]. The limitation of using a low-calorie diet (e.g., < 800 kcal/day) to manage diabetes is that the diet may not be sustainable over the long term [2]. The studies using carbohydrate restriction found improved glycemic control, but were often only short-term trials, only included small groups, focused on morbidly obese patients, and/or excluded subjects taking insulin [2, 6–10].

Despite the importance of good glycemic control and the association of postprandial glycemic response (PPGR) with diabetes complications, predicting the impact of specific foods on PPGR has been challenging due to the high variability in different people’s response to the same food [11]. Some attempts have been made to estimate PPGR using the carbohydrate content of meals [11] or using glycemic indices [12]. Few studies have attempted to build or test predictive models of PPGR based on specific foods eaten in individual meals [11, 13, 14]. None of the studies to date have combined long-term continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), artificial intelligence methods, and precision nutrition in an attempt to reverse diabetes.

The Twin Precision Nutrition (TPN) Program uses detailed patient food intake information and CGM values as inputs to a machine learning predictive model and then provides daily precision nutrition guidance to the patient. The objective of this study was to examine changes in HbA1c, anti-diabetic medication use, insulin resistance, and other ambulatory glucose profile (AGP) metrics between baseline and after 90 days of participation in the TPN Program in patients with T2D. We hypothesized that each metric would improve significantly over the 90-day treatment period.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

This was a retrospective study of 64 patients diagnosed with T2D who chose to participate in the TPN Program for 90 days and who were at least 60% adherent to program protocols. Program enrollees were required to have adequate hepatic and renal function to be included in the study, with the former defined as an aspartate transaminase or alanine transaminase ratio ≤ 3-fold the upper limit of normal, and the latter defined as serum creatinine ≤ 1.5 mg/dl or an estimated glomerular filtration rate > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2). Patients were excluded if they had a history of ketoacidosis, had major psychiatric disorders, or had myocardial infarction, stroke, or angina within the last 3 months prior to enrollment.

This study was approved by the Medisys Clinisearch Ethical Review Board and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. All subjects consented to participate in the program.

TPN Program

The TPN Program is an outpatient program that uses a whole body Digital Twin Technology, powered by artificial intelligence and Internet of Things, to understand the metabolic impairment in the patient’s body, which is unique to each patient. The platform collects data from body sensors and a mobile app to track and analyze the body's health signals in order to personalize the patient’s treatment.

During the first TPN Program enrollment visit of each patient, clinical history, vitals, electrocardiogram, and biothesiometry were assessed. Fasting blood specimens were drawn at baseline and at 30, 60, and 90 days of treatment. Health coach assistance was provided to each patient to support the TPN Program. Once the results of the initial blood test were known, the TPN mobile app had been installed, and the sensors had been activated, each patient was provided with a precision nutrition overview. Patients were asked to wear a sensor watch (Fitbit Charge 2 wristband; Fitbit, San Francisco, CA, USA) to continuously record sleep parameters, heart rate, step count, and other fitness parameters. Patients were also asked to record their blood pressure daily using a digital Bluetooth-enabled blood pressure meter (model TD-3140; TaiDoc Technology Corp., New Taipei City, Taiwan). Patients measured their weight each morning after the first void of urine using a PowerMax BCA-130 Bluetooth Smart Scale (PowerMax Fitness (India) Pvt Limited, Mumbai, India). Patients measured blood beta-hydroxybutyrate levels daily by means of finger prick. To create ambulatory glucose profiles, CGM was performed daily throughout the study using a Libre Pro CGM Diabetes Sensor (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA), and the data were integrated into the TPN Program web-based software. All these data were transmitted securely through a cellular network to the software each day. This information and software access were made available to the patients as biometric feedback via the TPN app.

Patients were also asked to record their food intake on the app each day. Machine learning algorithms analyzed the macronutrients, micronutrients, and biota nutrients from the database to determine the drivers of glucose response to specific foods for each participant. Factors found to be associated with glycemic response were analyzed for each participant. Participants were then provided with a set of specific food recommendations each day with the aim to avoid glucose spikes. Using CGM data, future blood glucose values of the participants were predicted using machine learning algorithms and data fusion techniques. Each food item within every meal was logged along with its weight by selecting it from a database of more than 2000 foods with full nutritional values based on the US Department of Agriculture FoodData Central database [15] that were further improved and expanded with additional items from certified sources [16]. The machine learning algorithm integrated these multi-dimensional data to predict personalized PPGR. Dietary intake is a central determinant of blood glucose levels and, therefore, to achieve normal glucose levels, it is imperative to make food choices that induce normal PPGRs.

The aim of the TPN Program was to provide the optimal combination of macronutrients, micronutrients, and biota nutrients, while simultaneously guiding individual patients to avoid foods that cause blood glucose spikes and to replace them with foods that do not produce glucose spikes. There was no cap on calorie consumption, and patients were allowed to consume food ad-libitum to satiety. Nutritional counselling was provided by trained coaches through the app and via telephone. Subjects with less than 60% adherence to the nutritional suggestions were excluded from the study.

Titration of medicines followed medicine guidelines based on CGM values and patient characteristics. The patients’ CGM values were supervised online on a daily basis by physicians, and diabetes medications were down-titrated based on the CGM readings. Any changes in medicine use were based on data from the Twin platform, and the physician would endorse the change or not at his/her discretion. Each patient’s insulin dose was adjusted based on daily average blood glucose levels. Oral hypoglycemic agents, such as metformin and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, were initially provided and reduced over time as the blood glucose levels improved. Further medication management was based on customized guidelines by the physician. All patients’ symptoms were recorded and analyzed by the physicians.

Outcome Measures

Patient age, gender, duration of diabetes, and body mass index (BMI) were recorded at enrollment. The primary endpoint in the study was HbA1c (%). HbA1c and the following secondary endpoints were assessed at baseline (program enrollment) and at 30, 60, and 90 days after enrollment: fasting blood glucose (FBG, in mg/dl), homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), estimated HbA1c (eA1c, as a percentage), mean glucose (mg/dl) obtained from CGM, C-peptide (ng/ml), sleep (h/night), steps per day, and heart rate (beats per minute [bpm]). Blood glucose percentage of time above range (TAR level 2) > 250 mg/dl and percentage of time > 180 mg/dl and ≤ 250 mg/dl (TAR level 1); percentage of time in range 70–180 mg/dl (TIR); percentage of time < 70 mg/dl and ≥ 54 mg/dl (time below range [TBR] level 1); and percentage of time < 54 mg/dl (TBR level 2) were recorded during the first week of the program and after 90 days of enrollment. Finally, insulin and oral hypoglycemic medication dosages were reported for each person at baseline and after 90 days of enrollment in the TNP Program.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviation (SD). Percentages were used to report the means of binary variables. Changes in mean values of continuous variables from baseline to 30, 60, and 90 days after enrollment were assessed using paired t tests. Changes in medians were evaluated using paired sign tests. Changes in average values of binary variables were assessed using McNemar’s chi-squared test.

Results

A total of 89 patients were enrolled in the TPN Program. Of these, 16 patients discontinued the program before 90 days of follow-up due to difficulties completing the study-related procedures (e.g., wearing the CGM for a prolonged period) or because of life-altering events, such as family emergencies. Among the remaining 73 patients, nine were eliminated from the analysis due to significant non-adherence to the nutritional instructions provided by the TNP Program. Of the 64 patients who remained in and adhered to the TPN Program, 19 (29.7%) were women. At enrollment, the average (SD) age of the 64 patients was 52.4 (10.0) years; average duration of T2D was 8.4 (6.5) years; average BMI was 29.2 (5.8) kg/m2; and 18.8% were taking insulin.

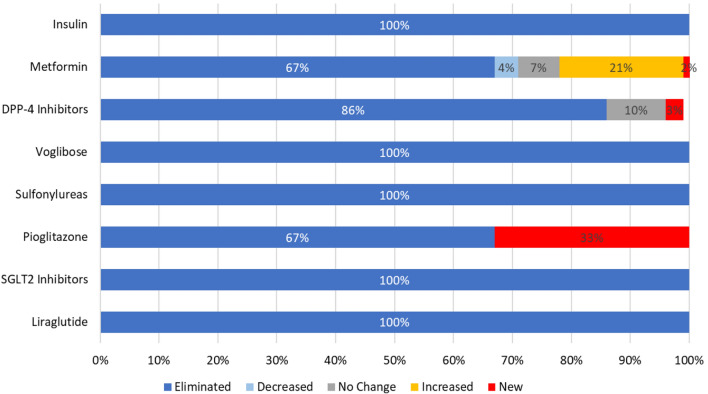

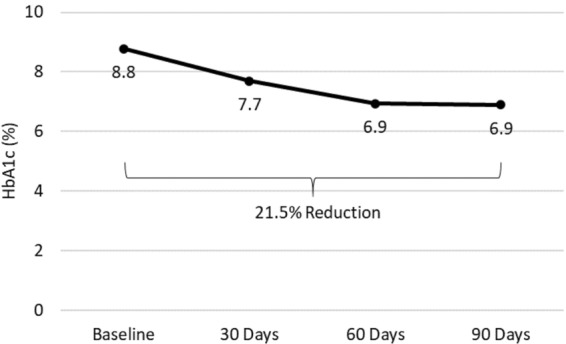

The mean (SD) HbA1c of the 64 patients decreased from 8.8% (2.2%) at baseline to 7.7% (1.6%) at 30 days and to 6.9% (1.1%) at 60 and 90 days (all p < 0.0001 vs. baseline) (Fig. 1). Six of the 64 patients (9.4%) had an HbA1c < 6.5% at baseline. The percentage of patients with measured HbA1c < 6.5% increased to 24.6% at 30 days, 38.0% at 60 days, and 39.7% at 90 days (all p < 0.003 vs. baseline) (Fig. 2). The eA1c also decreased significantly over the study period, from 6.9% (2.3%) at baseline to 5.7% (1.0%) at 30 days, 5.8% (1.0%) at 60 days, and 5.9% (1.2%) at 90 days (all p < 0.001 vs. baseline). The patients’ mean body weight decreased from 79.0 (16.2) kg at baseline to 76.1 (15.3) kg at 30 days, 75.1 (15.0) kg at 60 days, and 74.2 (14.7) kg at 90 days (all p < 0.0001 vs. baseline) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Change in mean hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) from baseline to 90 days of follow-up in patients who remained in and adhered to the Twin Precision Nutrition (TPN) Program for at least 90 days

Fig. 2.

Change in the percentage of patients with HbA1c < 6.5% from baseline to 90 days of follow-up

Table 1.

Changes in diabetes-related metrics in the study population from baseline to 90 days of follow-up

| Diabetes-related metrics | Baseline | 30 Days | 60 Days | 90 Days | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Valuesa | N | Valuesa | p value vs. baseline | N | Valuesa | p value vs. baseline | N | Valuesa | p value vs. baseline | |

| HbA1c (%) | 64 | 8.8 (2.2) | 61 | 7.7 (1.6) | < 0.0001 | 50 | 6.9 (1.1) | < 0.0001 | 63 | 6.9 (1.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Percentage of patients with HbA1c < 6.5% | 64 | 9.4% | 61 | 24.6% | 0.0027 | 50 | 38.0% | 0.0002 | 63 | 39.7% | < 0.0001 |

| eA1c (%) | 64 | 6.9 (2.3) | 64 | 5.7 (1.0) | < 0.0001 | 64 | 5.8 (1.0) | 0.0001 | 63 | 5.9 (1.2) | 0.0007 |

| Body Weight (kg) | 64 | 79.0 (16.2) | 64 | 76.1 (15.3) | < 0.0001 | 63 | 75.1 (15.0) | < 0.0001 | 64 | 74.2 (14.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dl) | 64 | 151.2 (45.0) | 62 | 135.2 (38.1) | 0.0043 | 50 | 131.5 (31.9) | 0.0205 | 62 | 129.1 (36.7) | 0.0001 |

| HOMA-IR | 64 | 7.4 (3.5) | 61 | 3.1 (2.5) | < 0.0001 | 50 | 3.3 (2.4) | < 0.0001 | 62 | 3.2 (2.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Mean glucose from CGM (mg/dl) | 64 | 147.4 (59.1) | 64 | 116.7 (27.9) | < 0.0001 | 64 | 120.5 (29.6) | 0.0001 | 64 | 122.6 (33.3) | 0.0009 |

| C-Peptide (ng/ml) | 64 | 3.2 (2.2) | 60 | 1.7 (0.9) | < 0.0001 | 49 | 2.1 (0.9) | < 0.0001 | 62 | 1.9 (0.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Sleep (h/night) | 58 | 5.9 (1.0) | 56 | 6.2 (1.1) | 0.1459 | 58 | 6.3 (1.2) | 0.1574 | 59 | 6.1 (1.3) | 0.6124 |

| Number of steps per day | 61 | 4677.4 (2804.9) | 58 | 6816.8 (2854.1) | < 0.0001 | 60 | 6788.8 (3384.1) | < 0.0001 | 61 | 7004.1 (3999.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Resting heart rate (bpm) | 64 | 75.0 [65, 85] | 62 | 72.5 [61, 84] | 0.0001 | 62 | 71.5 [62, 85] | < 0.0001 | 64 | 71.0 [62, 85] | < 0.0001 |

bpm Beats per minute, CGM continuous glucose monitoring, eA1c estimated HbA1c, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, HOMA-IR homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

aValues are presented as the mean with the standard deviation (SD) in parenthesis, the percentage, or the median with the minimum–maximum values in square brackets

Mean (SD) FBG fell from 151.2 (45.0) mg/dl at baseline to 135.2 (38.1) mg/dl at 30 days (p = 0.0043), 131.5 (31.9) mg/dl at 60 days (p = 0.0205), and 129.1 (36.7) mg/dl at 90 days (p = 0.0001) (Table 1). At baseline, 34.4% of patients had FBG < 126 mg/dl, whereas after 90 days on the TNP Program 59.7% of patients had FBG < 126 mg/dl.

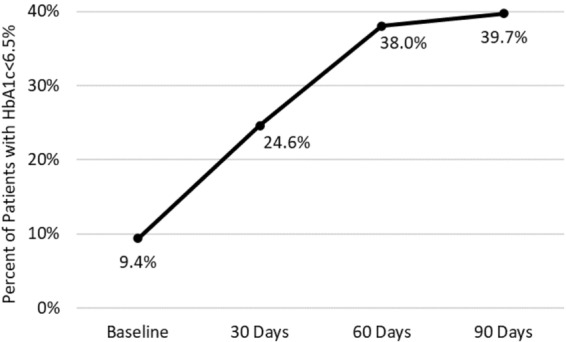

Mean HOMA-IR (SD) fell from 7.4 (3.5) at baseline to 3.1 (2.5) at 30 days, 3.3 (2.4) at 60 days, and 3.2 (2.8) at 90 days (all p < 0.0001 vs. baseline). The change from baseline to 90 days was a 56.9% reduction (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Change in homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) from baseline to 90 days of follow-up

Mean (SD) glucose levels obtained from CGM fell from 147.4 (59.1) mg/dl at baseline to 116.7 (27.9) mg/dl at 30 days, 120.5 (29.6) mg/dl at 60 days, and 122.6 (33.3) mg/dl at 90 days (all p < 0.001 vs. baseline). Similarly, mean C-peptide values decreased from 3.2 (2.2) ng/ml at baseline to 1.7 (0.9) ng/ml at 30 days, 2.1 (0.9) ng/ml at 60 days, and 1.9 (0.9) ng/ml at 90 days (all p < 0.0001 vs. baseline) (Table 1). Some of this decrease was driven by large decreases in patients with very high baseline C-peptide values, which resulted in closer-to-normal C-peptide values for those patients.

The increase in average number of hours of sleep per night was not significant, but mean (SD) number of steps taken per day increased from 4677.4 (2804.9) steps per day at baseline to 7004.1 (3999.0) steps at 90 days (p < 0.0001). Median resting heart rate decreased from 75.0 bpm at baseline to 71.0 bpm at 90 days (p < 0.0001) (Table 1). Mean calories consumed per day decreased from 1884.0 kcal (326.5) at baseline to 1649.6 (310.1) kcal at 30 days, 1607.4 (311.4) kcal at 60 days, and 1573.0 (373.1) kcal at 90 days.

During the first week of the program, 55 patients had TIR values > than 70%. This result was maintained, and at 90 days 57 patients had TIR values > than 70%.

In only one patient was the percentage of time > 250 mg/dl (TAR level 2 of 11.9%) higher than the accepted threshold (< 5%) [17] during the first week of the program; this was subsequently reduced to 0.5% at the end of 3 months of treatment. Two patients had an initial TAR level 1 that was above the accepted threshold (< 25%) [17]; these were reduced from 41.7 and 71.3% during the first week to 2.2 and 15.8%, respectively, after 3 months.

Eighteen patients had unacceptable [17] (> 4%) levels of TBR level 1 during the first week of the program; this number had improved at the end of 3 months to 12 patients with TBR level 1 > 4%. Thirteen patients had unacceptable [17] (> 1%) levels of TBR level 2 during the first week of the program; this number improved at the end of 3 months to only four patients with TBR level 2 > 1%.

Mean TAR level 2, TAR level 1, and TIR values reached normal ranges by the end of the first week of the TNP Program and were maintained through the 90 days of the follow-up. The mean (SD) TIR in the first week was 87.1% (16.8%) and continued as such throughout the 90-day period, ending at 87.1% (19.4%). Mean TBR level 1 values were slightly above the normal range in the first week and at 90 days. Mean TBR level 2 values were slightly above the normal range in the first week and then decreased further to well within the normal range by 90 days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Continuous glucose monitoring metrics at week 1 and at 90 days of follow-up

| Continuous glucose monitoring metrics | TNP Program week 1 | 90 Days of follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Range | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | p value vs. week 1 | |

| Blood glucose % time above 250 mg/dl (TAR level 2) | < 5 | 64 | 0.5 (1.6) | 64 | 1.8 (10.5) | 0.3189 |

| Blood glucose % time above 180 mg/dl and ≤ 250 mg/dl (TAR level 1) | < 25 | 64 | 4.8 (11.0) | 64 | 5.8 (9.4) | 0.5297 |

| Blood glucose % time in range 70–180 mg/dl (TIR) | > 70 | 64 | 87.1 (16.8) | 64 | 87.1 (19.4) | 0.9979 |

| Blood glucose % time below 70 mg/dl and ≥ 54 mg/dl (TBR level 1) | < 4 | 64 | 6.2 (11.9) | 64 | 5.0 (14.4) | 0.6136 |

| Blood glucose % time below 54 mg/dl (TBR level 2) | < 1 | 64 | 1.4 (3.2) | 64 | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.0056 |

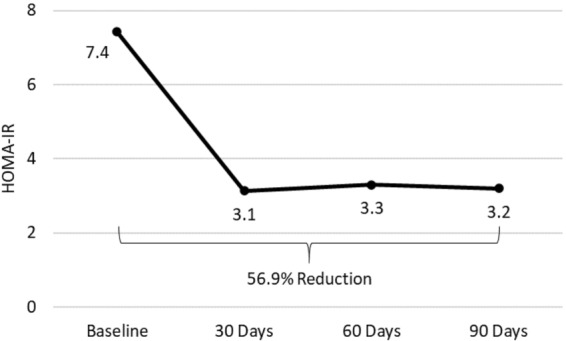

All 12 patients who were on insulin at baseline stopped insulin within 3 months after the start of the program. Of the 56 patients who were on metformin at baseline, 38 were able to stop taking metformin. One patient who was not on metformin at baseline began taking metformin during the 90-day period. Of the 28 patients on DPP-4 inhibitors at baseline (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, or teneligliptin), 26 were able to stop DPP-4 inhibitors. One patient not on sitagliptin at baseline began taking sitagliptin, and one patient switched from vildagliptin to sitagliptin. All 13 patients taking an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor medication (voglibose) at baseline were able to stop taking this medication. All 34 patients taking sulfonylureas (glibenclamide/glyburide, gliclazide, glimepiride, or glipizide) were able to stop taking them. Both patients taking pioglitazone at baseline had stopped by 90 days of follow-up. One patient began taking pioglitazone during the 90-day period. All ten patients taking sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors at baseline (dapagliflozin or empagliflozin) stopped taking their SGLT2 inhibitors prior to the end of the 90 days. The one patient taking a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogue (liraglutide) stopped as well (Fig. 4). Six of the 64 patients had no medicines at baseline.

Fig. 4.

Change (or lack thereof) in the percentage of patients taking medications for type 2 diabetes from baseline to 90 days of follow-up. DPP-4 Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, teneligliptin), SGLT2 sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin). Sulfonylureas taken by patients in study included glibenclamide/glyburide, gliclazide, glimepiride, and glipizide

We observed no cases of diabetic ketoacidosis. No new cases of gout were diagnosed, and no episodes of symptomatic hypoglycemia were reported. There were no other serious adverse events during the study. Non-serious adverse events, such as headache, tiredness, or constipation, occurred primarily early in the study and were transient.

Discussion

The TPN Program uses CGM, Internet of Things technology, food intake data, and machine learning algorithms to provide daily precision nutrition guidance to individual patients with T2D so that they can avoid foods that cause blood glucose spikes and replace them with foods that do not produce glucose spikes. The results of the study are consistent with the hypothesis that each diabetes-related outcome was significantly improved over the 90 days of the program.

The results from the present study compare well with those from prior investigations on interventions in diabetes patient populations. Studies of bariatric surgery have shown that normal HbA1c and glucose levels can be achieved in most patients following surgery, sometimes within a few days [1, 18]. Nearly 39.7% of the patients in the current study reached HbA1c < 6.5% within 90 days of initiating the TNP Program and 38.0% reached that level within 60 days. Studies have found that diets that are very low in calories quickly improve glucose and HbA1c levels and lead to discontinuation of insulin use [1, 19]. However, many low-calorie diet studies have also found that patients find these diets difficult to maintain and that the improvements in diabetic endpoints could not maintained long-term [20–23]. All patients taking insulin in the present study discontinued the use of insulin, with most oral anti-diabetic medications also discontinued. In the very low-calorie study by Steven et al. [19], 40% of patients reached FBG < 126 mg/dl (the threshold for partial remission of diabetes [24]) at 10 weeks when isocaloric eating was resumed, and 43% of patients continued to have FBG < 126 mg/dl at 6 months. In the current study, 59.7% of patients had FBG < 126 mg/dl after 90 days. In a study of morbidly obese diabetic patients on a low-carbohydrate diet, the HbA1c of these patients decreased from 7.6 to 6.6% in 10 weeks [2]; by 10 weeks, the percentage of people with HbA1c < 6.5% had increased from 20 to 56%, and 57% had one or more diabetes medications reduced or eliminated [2]. Within 1 year, the HbA1c had dropped to 6.3%, 94% of these patients had stopped taking insulin, and 100% had stopped taking sulfonylureas [5]. In comparison, the patients in the current study started with a higher average HbA1c (8.8%) and had a larger decrease (1.9 percentage points) in HbA1c and a higher rate of elimination of diabetes medications after 90 days (13 weeks). In a study of patients with T2D on a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet [7], HbA1c decreased from 8.8 to 7.2% and FBG fell from 178.1 to 156.4 mg/dl over a 12-week period. This decrease in HbA1c is slightly less than that observed in the present study, but the percentage decrease in FBG is the same in both studies (12.2%).

Reductions in HbA1c and HOMA-IR have been shown to be correlated with lower health risk in patients with diabetes. Stratton et al. showed that a 1.0% reduction in HbA1c is associated with a 37% reduction in diabetes microvascular complications [25]. Bonora et al. reported that lower HOMA-IR values independently predicted lower cardiovascular disease prevalence and incidence [26]. The 1.9 percentage point decrease in HbA1c and 56.9% reduction in HOMA-IR, combined with fewer medications, that was achieved in our study population have the potential to lower the number of vascular complications in this patient population and thus result in cost savings over time. Increasing the TIR (even by only 5%) and decreasing TBR have also been shown to be associated with fewer diabetes complications [17]. TIR is strongly correlated with HbA1c, and each 10% increase in TIR corresponds with a 0.4–0.8 percentage point reduction in HbA1c [27, 28]. Additionally, the hazard rates for retinopathy progression and microalbuminuria have been shown to increase by 64 and 40%, respectively, for each 10% reduction in TIR [29]. Similarly, a post hoc analysis of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial data showed a link between TBR glucose thresholds of < 70 mg/dL and < 54 mg/dL and an increased risk for severe hypoglycemia [30]. After 90 days on the TPN Program, 57 patients (89.1%) had TIR 70–180 mg/dl ≥ 70%. The number of patients in the TPN Program with unacceptable TBR level 1 values decreased from 18 patients at week 1 to 12 patients at 90 days, and those with unacceptable TBR level 2 values decreased from 13 patients at week 1 to only four patients at 90 days of follow-up.

The strengths of this study include the significant improvements in patient outcomes and the serial HbA1c testing with continuous AGP monitoring that shed new light on changes in AGP metrics. The nutritional intervention happened in an outpatient setting employing home-cooked foods, making the intervention sustainable in the long term. App-based logging of food by patients allowed for accurate assessment of nutrition.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, a relatively small study population, and no control arm. Additionally, although most of the patients discontinued diabetes medications and reached the FBG threshold for partial remission of diabetes, the length of the study was not long enough to verify remission of diabetes. This will be the goal of subsequent randomized controlled studies.

Conclusion

The results provide evidence that daily precision nutrition guidance based on CGM, Internet of Things technology, food intake data, and machine learning algorithms can benefit patients with T2D. Diabetes-related endpoints in the 64 participants who adhered to the TNP Program for 90 days improved significantly over the course of the study. Following 3 months of the TPN Program, patients achieved a 1.9 percentage point decrease in HbA1c, a 56.9% reduction in HOMA-IR, a significant decline in TBR, and the elimination of diabetes medication use in most of the patients. Ongoing results will shed further light on the long-term effectiveness, safety, and sustainability of the TNP Program.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to the participants of the study.

Funding

This study was funded by Twin Health, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA. Twin Health, Inc. also funded the Rapid Service Fees.

Other Assistance

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Mohammed Abul Hassan and Dr. Rajamohan for using TPN with their patients. We appreciate and gratefully acknowledge the input of Mr. Hanif Syed and the members of his operation team, and thank Ms. Monika Nanda and Ms. Abinaya, who offered necessary support in handling sensors, blood investigation coordination, and health coaching. We would also like to acknowledge the engineering and product design team for making all necessary technology support in offering a friction-free best patient experience.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Paramesh Shamanna, Jahangir Mohammed, Maluk Mohamed, Terrence Poon, and Mohamed Thajudeen are employees of Twin Health. Banshi Saboo and Suresh Damodharan are members of the advisory board of Twin Health. Nathan Kleinman is a consultant to Twin Health.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by the Medisys Clinisearch Ethical Review Board and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. All subjects consented to participate in the program.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.12943226.

References

- 1.Hallberg SJ, Gershuni VM, Hazbun TL, Athinarayanan SJ. Reversing type 2 diabetes: a narrative review of the evidence. Nutrients. 2019;11:766. doi: 10.3390/nu11040766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenzie AL, Hallberg SJ, Creighton BC, et al. A novel intervention including individualized nutritional recommendations reduces hemoglobinA1c level, medication use, and weight in type 2 diabetes. JMIR Diabetes. 2017;2:e5. doi: 10.2196/diabetes.6981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. https://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/grd-2016/en/. Accessed 24 June 2020.

- 4.Ramos-Levi AM, Cabrerizo L, Matia P, Sanchez-Pernaute A, Torres AJ, Rubio MA. Which criteria should be used to define type 2 diabetes remission after bariatric surgery. BMC Surg. 2013;13:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallberg SJ, McKenzie AL, Williams PT, et al. Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the management of type 2 diabetes at 1 year: an open-label, non-randomized. Controlled Study Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:583–612. doi: 10.1007/s13300-018-0373-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yancy WS, Olsen MK, Guyton JR, Bakst RP, Westman EC. A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:769–777. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westman EC, Yancy WS, Mavropoulos JC, Marquart M, McDuffie JR. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008;5:36. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-5-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen JV, Joensson EA. Low-carbohydrate diet in type 2 diabetes: stable improvement of bodyweight and glycemic control during 44 months follow-up. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2008;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saslow LR, Kim S, Daubenmier JJ, et al. A randomized pilot trial of a moderate carbohydrate diet compared to a very low carbohydrate diet in overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazzano LA, Hu T, Reynolds K, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:309–318. doi: 10.7326/M14-0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmora N, et al. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell. 2015;163:1079–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Taylor RH, et al. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:362–366. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendes-Soares H, Raveh-Sadka T, Azulay S, et al. Model of personalized postprandial glycemic response to food developed for an Israeli cohort predicts responses in Midwestern American individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(1):63–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seo W, Lee Y, Lee S, Jin S, Park S. A machine-learning approach to predict postprandial hypoglycemia. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19:210. doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0943-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019). FoodData Central Download Data. Agricultural Research Service. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/download-datasets.html. Accessed: 24 June 2020.

- 16.Longvah T, Ananthan R, Bhaskarachary K, Venkaiah K. Indian Food Composition Tables 2017. National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research, Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. https://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/IFCT%25202017%2520Book.pdf. Accessed: 24 June 2020).

- 17.Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1593–1603. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubino F, Gagner M. Potential of surgery for curing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2002;236:554–559. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steven S, Hollingsworth K, Al-Mrabeh A, et al. Very low-calorie diet and 6 months of weight stability in type 2 diabetes: pathophysiological changes in responders and nonresponders. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:808–815. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammer S, Snel M, Lamb HJ, et al. Prolonged caloric restriction in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus decreases myocardial triglyceride content and improves myocardial function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snel M, Jonker JT, Hammer S, et al. Long-term beneficial effect of a 16-week very low calorie diet on pericardial fat in obese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Obesity. 2012;20:1572–1576. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paisey RB, Harvey P, Rice S, et al. An intensive weight loss programme in established type 2 diabetes and controls: effect on weight and atherosclerosis risk factors at 1 year. Diabet Med. 1998;15:73–79. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199801)15:1<73::AID-DIA516>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wing RR, Blair E, Marcus M, Epstein LH, Harvey J. Year-long weight loss treatment for obese patients with type II diabetes: Does including an intermittent very-low-calorie diet improve outcome? Am J Med. 1994;97:354–362. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buse J, Caprio S, Cefalu W, et al. How do we define cure of diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):2133–2135. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonora E, Formentini G, Calcaterra F, et al. HOMA-estimated insulin resistance is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetic subjects: prospective data from the verona diabetes complications study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1135–1141. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirsch IB, Battelino T, Peters AL, Chamberlain JJ, Aleppo G, Bergenstal RM. Role of continuous glucose monitoring in diabetes treatment. Arlington: American Diabetes Association; 2018.

- 28.Vigersky RA, McMahon C. The relationship of hemoglobin A1C to time-in-range in patients with diabetes. DiabetesTechnolTher. 2019;21:81–85. doi: 10.1089/dia.2018.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, Riddlesworth TD, et al. Validation of time in range as an outcome measure for diabetes clinical trials. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:400–405. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, Riddlesworth TD, Kollman C. The association of biochemical hypoglycemia with the subsequent risk of a severe hypoglycemic event: analysis of the DCCT data set. Diabetes TechnolTher. 2019;21:1–5. doi: 10.1089/dia.2018.0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.