Abstract

Insurance enrollment is complex for people living with HIV (PLWH) and people at increased risk for HIV, in part, owing to needing to ensure access to adequate provider networks and appropriate formularies. Insurance for PLWH facilitates access to HIV care/treatment and, ultimately, viral suppression, which has the individual benefit of longevity and the public health benefit of decreased HIV transmission. For people at increased risk for HIV, access to insurance facilitates improved access to HIV biomedical prevention, which has the individual benefit of elimination of transmission risk and the public health benefit of decreased HIV transmission. The objective of this study was to explore perceptions of priorities related to plan navigation, barriers and facilitators for enrolling and maintaining insurance coverage, and questions related to regional, state, and federal policies impacting plans provided both on and off the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace. We interviewed a national sample of assisters (n = 40), who specialize in insurance plan selection for these populations. We found that assisters tailor their approaches to HIV-specific and person-specific concerns by navigating challenges related to affordability, formularies, and provider networks. In a complex coverage landscape during a time of uncertainty about the long-term future of the ACA, assisters have mastered the ability to simplify the insurance selection process for a vulnerable population. Assisters have excelled at incorporating insurance literacy education and encouraging client engagement in the process. Assisters play an essential role in the current complicated and fragmented United States' health care delivery system for PLWH and people at increased risk for HIV and could be incorporated into the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative.

Keywords: HIV, preexposure prophylaxis, access to health care, health care reform, health insurance, patient protection and Affordable Care Act

Introduction

Insurance enrollment is complex for people living with HIV (PLWH) and at increased risk for HIV, in part, owing to needing to ensure adequate provider networks and formularies. For PLWH, provider networks need to include clinicians who provide medical care for PLWH, and for those who are at increased risk for HIV, the network needs to include a clinician who is willing to prescribe HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for biomedical prevention.1,2 With the high costs associated with antiretroviral therapy (ART) and PrEP, PLWH and those at increased risk of HIV need to ensure that these medications are on formulary and that the client's out of pocket cost will be minimized.3,4

Before the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010, HIV was essentially an uninsurable preexisting condition in the individual market.5 Because of this issue, shopping for individual market coverage was relatively new for PLWH. After the full implementation of the ACA in 2014, the percentage of PLWH with private insurance was estimated to have doubled by 2015.6,7 For many people who gained insurance, there has been a shift in how they access health care and medications (e.g., utilizing a provider network, accessing primary as opposed to emergency care, and navigating formulary limitations). For PLWH, particularly with lower incomes, insurance enrollment is often coordinated with Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP) clinics and state AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAPs).7,8

While ensuring adequate health insurance is not an explicit part of the federal government's Ending the HIV Epidemic,9 health insurance has impacts on access to HIV care,10 access to ART,11,12 achievement of viral suppression,13–15 and access to PrEP.16 Access to HIV care and viral suppression are associated with improved morbidity and mortality for the individual.17,18 For PLWH, insurance has also been associated with a survival benefit.12 In addition, there is a public health benefit to individuals achieving viral suppression because that results in less HIV transmission.19–22

For those at increased risk for HIV, lack of health insurance is a barrier to PrEP access.16 In addition, lack of health insurance has been associated with delayed PrEP initiation despite available patient assistance programs and any delay in initiation can result in preventable HIV infections.23 Moreover, PrEP-related out-of-pocket costs can vary widely depending on one's insurance,24 and high PrEP-related costs are a barrier to PrEP use.25–27 PrEP reduces HIV transmission for sexual encounters by >90% and for injection drug use by >70%.28 Each HIV infection that is averted saves approximately $400,000.29 Ensuring adequate insurance for PLWH and people at increased risk for HIV has individual-level benefits and societal benefits. It is line with two essential goals of the U.S. government's Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative: improved viral suppression and improved HIV biomedical prevention, through access to PrEP.9

Throughout the United States, there are people who specialize in assisting PLWH and people at increased risk for HIV with navigating insurance enrollment and maintaining insurance coverage. These assisters, sometimes referred to as benefits specialists or nonmedical case managers, vary by jurisdiction depending on funding and programmatic needs. Many assisters focused on HIV treatment are funded directly by state ADAPs, with a focus on enrolling ADAP eligible clients into health insurance. For PrEP, assisters are more decentralized, with clinics employing their own assister workforce. Training to become an assister also varies, but many programs utilize the federal certified application counselor (CAC) training and resources. Given limited funding and strict financial eligibility criteria for services, the number of PLWH and people at increased risk for HIV who are able to access assisters is likely relatively low.

Through interviews with assisters, the objective of this study was to explore (1) perceptions of a) priorities related to plan navigation, b) barriers and facilitators for enrolling and maintaining insurance coverage, and (2) questions related to regional, state, and federal policies impacting plans provided both on and off the ACA marketplace.

Methods

Data source

State health departments were asked for lists of insurance assisters who specialize in insurance enrollment for PLWH and those at increased risk for HIV who are prescribed PrEP. The study was approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board for Social and Behavioral Sciences. We conducted semistructured telephone-based interviews with insurance assisters who specialized in insurance plan selection for PLWH and people at increased risk for HIV who were prescribed PrEP. At the time of the study, only one formulation of PrEP was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration: the once-daily combined tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine. For the duration of the article, PrEP will refer to that formulation. Interviews occurred from February through April 2019. We used purposive sampling to identify states that varied by region, dominant political party, rural versus urban predominance, HIV prevalence, assister type, assister focus on HIV or PrEP, and whether the state had undergone Medicaid expansion.

Respondents were asked to respond to interview questions specific to characteristics of their role, perceptions of their priorities related to plan navigation for clients, barriers and success stories for enrolling and maintaining insurance coverage for clients living with HIV or those on PrEP, specific questions related to regional, state, and federal context for the plans provided both on and off the marketplace (see Appendix for interview guide). Each interview lasted between 20 and 45 min. Participants were compensated for their time. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were then uploaded to Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Manhattan Beach, CA), a qualitative software management program.

Analysis

We analyzed the interview responses using qualitative descriptive methodology,30,31 meaning the analytical frame was guided by an open coding strategy that was applied to the entire data set, followed by inductive theme development using thematic analysis. The text data were analyzed by (1) immersion in the data (reading the transcripts several time for context), (2) line-by-line analysis and data reduction in which inductive codes were derived and applied, and (3) codes that were conceptually grouped together to form final themes.32 We also used aspects of situational analysis33 to map the multiple sectors mentioned by assisters as being either directly or peripherally involved with maintenance of insurance for persons living with HIV and persons at increased risk for HIV.

Rigor and trustworthiness were addressed in the following ways: an audit log was maintained during the analytical process to document decisions. Aspects of the study process and analytical log was open for review by all members of the study team. Content validity was addressed by review of key findings with all members of the study team.

Results

The participation rate was 60.6% with 40 participants from 18 states. The majority of the participants assisted clients in southeast (50%), followed by the midwest (22%), west (15%), and northeast (13%). The majority of settings the assisters worked were community based (65%) followed by state/local government (18%), and clinic or health-system settings (18%). Most assisters were CACs (63%) and worked year round (88%) versus seasonally.

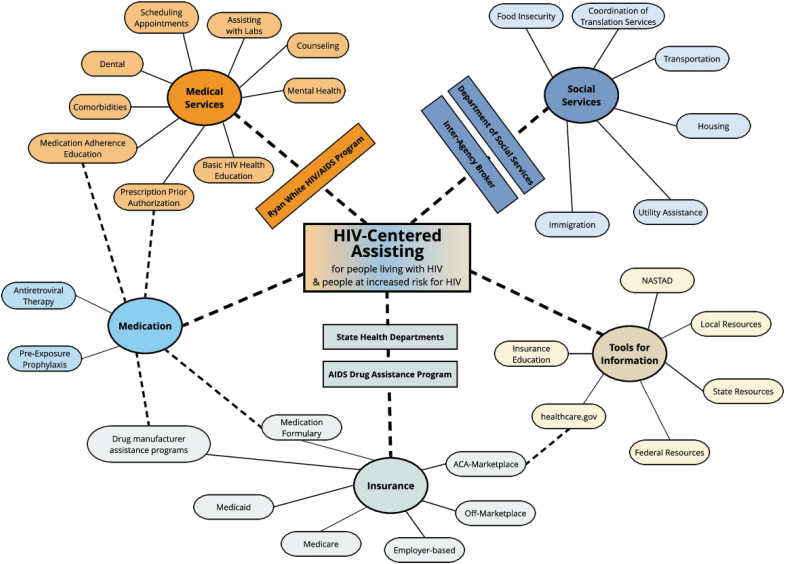

Three overall themes were developed that described the process and context for insurance navigation for persons living with HIV that included the following: (1) person-centered and HIV-centered navigation (subthemes included costs of plans, specialty drug challenges, and fragmentation of network providers) (2) complexity of coverage landscape (subthemes include temporal features, uncertainties in a nested federal, state, and local context), and (3) engagement for informed choices (subthemes include health insurance literacy and promoting congruity and stability to mitigate intersectional risks). Themes, subthemes, and sectors discussed by assisters as being key to enroll these vulnerable populations were incorporated into a situational map (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Situational map of assisters' key themes, subthemes, and sectors for insurance navigation for people living with HIV and people at increased risk of HIV. Color figures are available online.

Theme 1: person-centered and HIV-centered navigation

The assisters described a process of navigation that was inherently person centered, recognizing that no two clients living with HIV have the same insurance coverage needs (Table 1). They described starting the navigation process with the costs of the plans available with personalized premium and deductible estimates based on the client's income, and working with the client to anticipate health needs in the upcoming year. One assister described, “We would talk with them about the level of medical care they anticipated needing over the year and select a plan without having to meet a large deductible first.”

Table 1.

Thematic Exemplar of Person-Centered and HIV-Centered Navigation

| Theme: Person-centered and HIV-centered navigation |

|---|

| Subtheme: Costs of plans |

| “It's a really unique situation because the costs as they appear on healthcare.gov or other cost comparison tools are not necessarily reflective of our clients' cost because ADAP [and other programs like Ryan White clinics] do help defray a lot of the costs. We then have to look outside of the HIV world to understand other costs as well.” (Participant 10: southeast, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “Especially with some of our younger clients in service industries, they are offered minimal essential coverage that will cover generic medications and doesn't cover HIV treatment at all….letting them know that it would better to stay on the ACA plan because you're not going to get the coverage you need offered by your employer.” (Participant 17: southeast, community-based setting) |

| “We have 3 or 4 plans we work with…we check with all of the hospitals and make sure they accept the plan and of course, check the medication coverage.” (Participant 18: southeast, community-based setting) |

| “I think increased costs are distributed in other ways—moving to coinsurance models, shrinking networks, other changes to tier formularies—I would say hidden costs.” (Participant 29: west, community-based setting) |

| Subtheme: Specialty drugs challenges |

| “Specifically with PrEP labs and follow-up labs are a big deal, we have a lot of patients who come out with large bills because of lab work.” (Participant 6: southeast, state/local government setting) |

| “There are huge challenges with getting PrEP access especially in rural parts of the state. I can remember an instance where we could not find a provider willing to prescribe PrEP and let alone prescribe it to someone under 18. Most of the doctors in our state believe they have to be infectious disease doctors to prescribe it” (Participant 6: southeast, state/local government setting) |

| “I also make sure that they're able to get medications quickly even if it means calling ADAP to make sure that they can get meds in the gap between enrollment date and when their insurance starts.” (Participant 23: west, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “The cost of prescriptions was the biggest driver for decisions and I feel like in smaller states with less competition there are times when one plan will cover your medication and the other won't so you are only left with one option.” (Participant 38: northeast, state/local government setting) |

| Subtheme: Fragmentation of network providers |

| “We did not have enough doctors in that network to provide HIV care to everyone.” (Participant 22: midwest, state/local government setting) |

| “Some insurers require a medical home and they're required to see a primary care doctor first before they can see a specialist…that can be a challenge for newly diagnosed clients who want to see an HIV specialist right away.” (Participant 23: west, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “Clients tend to be attached to providers and a change in provider can be very traumatic for them.” (Participant 23: west, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “The [approved] provider networks are narrowing.” (Participant 23: west, clinic/health-system setting) |

After each quote, there is information about the participant who stated the quote: “(Participant number: region, setting).”

ACA, Affordable Care Act; ADAP, AIDS Drug Assistance Programs; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis.

The assisters also perceived that rising premiums were a high priority concern for their clients, particularly for those ineligible for federal premium tax credits or at a higher income where premium tax credits were lower. However, the assisters said that this concern was often offset because the state ADAPs covered the premium cost for many clients. As described, “Without the [State ADAP] to pay for the premiums, our individuals wouldn't be able to afford them.” Many assisters brought up the fact that ADAP support, through premium payments and cost sharing for ART and HIV medical visits, for clients with HIV was crucial to them being able to afford plans. Beyond income, assisters also assessed age and other comorbidities to determine the overall context of care needs for their clients.

The assisters also recognized having professional experience representing persons living with HIV was critical in providing person-centered navigation, and said that specifically understanding the context of HIV medical care and ART for clients living with HIV or PrEP for those at increased risk for HIV was a central feature of their navigation process. One challenge that was cited repeatedly was that most ART regimens and PrEP are specialty drugs, which adds a layer of complexity. Resoundingly, knowing how specific insurance plans covered ART was described by assisters as a central component of navigation. As one assister described, “Almost all of the plans code HIV meds as a higher tier (tier 4 or 5 specialty meds) and most of them are 15% co-insurance, so if you're taking a $2000/month medication, that's a lot.”

Assisters raised concerns with ART being covered by the plan formulary one year, and not the next year, and changes to ART regimens covered (e.g., coverage only paying for certain pill combinations). In addition, they shared that while the state ADAPs often cover cost sharing for drugs specific to HIV care, drugs related to other comorbidities were noted to be a large financial concern. Some assisters stated that formulary coverage of ART was better than coverage of PrEP because the only drug that was approved for PrEP at the time of this study—a brand name medication of combined tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine—was more often on the specialty drug tier and subjected to prior authorization.

Assisters also commented about the difficulty of people less than the age of 18 finding a provider who would prescribe PrEP despite adolescents being added to the FDA indication in 2018. Many assisters referenced that PrEP cost for the medication was not an issue because of the drug manufacturer assistance programs, which provide assistance to insured individuals to pay for medication cost sharing (however, these programs do not cover cost sharing associated with clinic and lab visits). Of interest, an assister in a rural southeast location specifically described that the challenges with accessing PrEP were not because of the cost of the medication, but because of the lack of providers willing to prescribe the medication.

Assisters shared that assessment of the client's provider network was also a key component of person-centered navigation to ensure that clients could continue to see their HIV clinician or the clinician who prescribed their PrEP. Assisters noted many challenges with narrowing of provider networks, not enough HIV specialists in networks, or the situation of a fragmented provider network (within one group/facility, some specialist providers are in network and others out). As described, “Several of my clients had to pick one hospital to stay in-network for their HIV care, but then we had to send them somewhere else for their blood work because insurance didn't cover [that hospital's] lab, so they had their care split between two [locations].” Assisters also raised that some insurance networks did not have enough specialist providers to provide HIV care to everyone.

Theme 2: complexity of coverage landscape

Insurance assisters have the difficult task of providing navigation in a constantly evolving coverage landscape (Table 2). Central to this theme, assisters expressed the temporal features that add to the complexity or the changes that occur year to year coupled with the short time periods for open enrollment. As described, “We only get a small window. It's from November to December, it's only 45 days that patients have to reenroll or enroll for health coverage.”

Table 2.

Thematic Exemplar of Complexity of Coverage Landscape

| Theme: Complexity of coverage landscape |

|---|

| Subtheme: Temporal features |

| “A lot of our patients have concerns when [State ADAP] is slow sending out the payments because it causes insurance companies to cancel their plans.” (Participant 21: southeast, community-based setting) |

| [serves rural population]…“transportation is a huge barrier so trying to get people enrolled in the plan [during open enrollment] is such a time crunch.” (Participant 27: midwest, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “So they pick a pharmacy and I do a plan comparison and I find out the pharmacies were bought out and no longer in network so it changes at the last minute….during open enrollment I was able to get their plan switched and saved them over $86,000 for the year.” (Participant 27: midwest, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “I would say the biggest challenge was just having people get the required documentation in…verifying eligibility for tax credits and verifying citizenship.” (Participant 34: west, community-based setting) |

| Subtheme: Uncertainties in a nested federal, state, local knowledge and context |

| “I think being someone who can communicate and link people—letting them know what's going on at the state level [is important].” (Participant 1: midwest, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “We've recently expanded [Medicaid] so folks still don't know what they are eligible for.” (Participant 6: southeast, state/local government setting) |

| “With our current political climate the last two open enrollments have been more stressful in general.” (Participant 23: west, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “Helping clients is never black and white, the guidelines are not clear. I have encountered problems with every single person I have enrolled.” (Participant 30: southeast, community-based setting) |

After each quote, there is information about the participant who stated the quote: “(Participant number: region, setting).”

Assisters added that when clients have transportation or documentation challenges, including issues with immigration status, it can add additional layers of complexity to this already compressed timeframe. In addition, assisters stated that navigation is occurring within a patchwork of federal and state policies and programs and nested local resources. Assisters also stressed that keeping up with the changes that occur year to year and the documentation requirements for enrollment can be challenging. One participant noted, “The language is just so confusing and the levels of complexity are so much for some cases.”

In addition, issues with transitions between coverage, such as from ADAP-supported marketplace plans to Medicaid when a state expands Medicaid coverage, were mentioned by assisters as an issue. One assister shared, “We are seeing patients who get both Medicaid and an Obama Care card and can't get access to medicines either way.” Assisters voiced that the navigation process is occurring within the current sociopolitical context that involves uncertainties-related political climate and long-term political solvency of the Affordable Care, and as a participant described a “fear and trepidation of what comes next [politically].” To offset this uncertainty, many of the assisters described a sense of comradery and connection to those doing similar work and the desire to be up-to-date with the evolving sociopolitical context of care.

Theme 3: engagement for informed choices

Participants uniformly described a navigation process that can result in client engagement to make informed health insurance choices (Table 3). Assisters highlighted that education was a key component because most of their clients had never had health insurance. They cited needing to explain how health insurance works and the value of it. The structure of providing enhanced health insurance literacy is one way the assisters evoke client engagement. For example, one assister shared, “For patients that have been lost to care and not wanting to be compliant with medications, by counseling and just being consistent we let them know we care…and they can become undetectable.”

Table 3.

Thematic Exemplar of Engagement for Informed Choices

| Theme: Engagement for informed choices |

|---|

| Subtheme: Health insurance literacy |

| “I feel like if we are going to continue with the federal marketplace we have to bring back in the outreach and education component because there's too many people falling through the cracks and don't know that we're here” (Participant 3: southeast, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “I think the thing that sticks out for me is how far people are willing to go to get in-person assistance that they can't get by simply calling the marketplace help line.” (Participant 10: southeast, clinic/health-system setting) |

| “I just think the language and terminology gets so overwhelming for folks.” (Participant 16: west, community-based setting) |

| “Some were confused about what they need to look for [in a plan]…we are able to educate all clients on their insurance, how it works, their provider networks, the cost to them as well as to the state” (Participant 22: midwest, state/local government setting) |

| Subtheme: Promoting congruity and stability to mitigate intersectional risks |

| “There is a very high stigma about delivering care for those who are perceived at risk, those who are people of color, gender non-conforming, or identify as non-binary…there are multiple problems at the intersections.” (Participant 6: southeast, state/local government setting) |

| “Our bilingual support has been critical…helping establish care in linguistically and culturally appropriate ways has been super helpful and great [for me] to advocate for the Latino community.” (Participant 11: southeast, community-based setting) |

| “Getting out of jail is a big special enrollment window for folks outside of open enrollment and you have to continually submit documentation of either release paperwork or an affidavit that they're in the community that proves it's a special enrollment period…you end up having to submit documentation like six times.” (Participant 17: southeast, community-based setting) |

| “We got creative with our homeless patients to make sure they got their insurance paid, so I had to use my valid address here to get their premium notices.” (Participant 39: southeast, community-based setting) |

After each quote, there is information about the participant who stated the quote: “(Participant number: region, setting).”

In addition, one assister described the importance of education beyond insurance that includes life skills, such as “how to open mail, and get insurance premium [bills] sent to ADAP” or “the difference between a bill and an explanation of benefits.” Similarly, another assister described health literacy as a process that extends beyond HIV-specific care, “I explain to them the difference between primary care and emergency care services. I also give them the explanation on their role as an individual not just to themselves but the community as well…we discussed establishing a relationship with a primary care provider and learned the benefits of establishing a relationship. I taught them how health insurance works and how it works with other services they are enrolled in such as ADAP and the Ryan White programs they are involved in. I discuss how each one of those programs is a puzzle piece that is designed to work together to reduce the possibility of them creating bills they can't afford which can turn into a barrier for them accessing care.”

Many assisters described education processes specific to insurance, such as explanations of deductibles and copayments. Assisters described the modalities they used for education, such as comparison tools, specific websites, and visuals. Although a central goal for navigation is enhanced health insurance literacy for all clients, the assisters did discuss specific subpopulations with complex needs including those with limited English proficiency, those who identify as transgender, clients who are homeless or have unstable housing, clients who were previously incarcerated and reentering the community, and older clients who may be aging into Medicare coverage.

Assisters expressed that the long-term goals of insurance navigation extended beyond insurance itself to include other positive spillover impacts health and wellbeing because of the stability insurance provides and the potential for this stability to mitigate other intersectional risks. As one assister described, “With [client] able to pay for the marketplace, this individual was able to stay in his home, and actually purchase his home.” Insurance assisters perceived that congruity and stability of maintaining insurance had positive spillover impacts beyond the financial aspect for their clients living with HIV.

Discussion

The first theme we found was that assisters have tailored their approaches to HIV-specific and person-specific concerns by navigating challenges related to affordability, formularies, and provider networks. In a recent study, Virginia ADAP clients reported that assisters helped them to overcome barriers and successfully enroll in marketplace plans on the ACA marketplace.34 With the emergence of the theme of person-centered and HIV-centered navigation, it is essential to note that the assisters cited previous education about HIV care, HIV risk, and additional knowledge about HIV-related resources (RWHAP, ADAP, pharmaceutical assistance programs) as essential in helping to inform their assistance for these vulnerable populations. This underscores the importance of ensuring that there are navigators with this experience who are available in every state.

Unfortunately, over the past 4 years, there has been an 85% decrease in federal funds to support navigators in states using the federal marketplace (currently 34 states).35 In addition, following the 2017 cut in navigator funds, a Kaiser Family Foundation study found that many organizations reported that the funding reduction resulted in a 50% reduction in assisters.36 These funding cuts endanger the availability of knowledgeable assisters across the United States and could lead to disparities in access to optimal insurance coverage. It raises the question of whether RWHAP resources could be put toward this service or whether insurance navigation could be added to the current role of RWHAP-funded HIV case managers.

In addition, the first theme highlights the issue that someone living with HIV or at increased risk for HIV needs to feel comfortable disclosing this information to an insurance assister for the assister to be able to accurately compare insurance options. This may be more difficult in areas of the country, such as the South, with higher rates of stigma and bias related to living with HIV or identifying as LGBTQ.37

Possible solutions would include the availability of private spaces to discuss insurance navigation and possibly colocating assisters in RWHAP clinics, as has been done in Virginia and other states.8 In the Virginia example, a RWHAP clinic became a CMS-certified designated organization, which allowed the clinic to train and certify CACs. Through this RWHAP-supported program, the clinics' CACs offered evening/weekend enrollments in an effort to be available at convenient times for clients. They also offered off-site enrollments at libraries, community-based organizations, and AIDS service organizations to reach a large catchment area. The program was successful with QHP enrollment rates of eligible clinic clients at 94% in 2014 and 97% in 2015.8

Central to the first theme is the issue that assisters operate in different political contexts and with vastly different state and local resources. Assisters operating in states with robust state-based marketplaces had more plan assessment tools available, making it easier to help clients find the plan they needed. For example, whereas all assisters could access the NASTAD resource on selecting insurance for someone who needs access to PrEP,38 only some states, such as California, have created a website specifically designed to help determine the best insurance plan for PLWH.39 More state marketplaces and the federal marketplace could consider adding these resources to their websites.

Within personalized navigation, it is clear that there were issues with ensuring affordability and access to adequate formularies and provider networks. Assisters emphasized that ensuring continuity of ART year-to-year has become more difficult as plans limit ART coverage or change ART coverage, particularly with regard to single tablet regimens. The fact that ART is more commonly covered on highest cost specialty tiers creates affordability barriers. Previous studies and nonprofit advocacy organizations have found evidence of discriminatory formulary design for ART, which results in increased costs to the consumer.40–42 Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that at least 7% of PLWH engage in cost saving-related nonadherence that is associated with worse health outcomes.43

The challenges in access to comprehensive formularies with fair utilization management practices and affordable cost sharing for ART and biomedical prevention speaks to the need for additional federal and state regulation and enforcement to ensure nondiscriminatory plan design.44 For clients who have ADAP-supported individual market plans or ADAP-supported medication costs, ART cost sharing and copays are covered; however, this still leaves significant gaps for PrEP.

One issue that came up specifically about PrEP was the difficulty in ensuring access because of the fact that there was not a federal or state program analogous to the RWHAP or ADAP for PrEP-related care and medication access. There has been a drug manufacturer medication assistance program in place for many years for uninsured individuals with incomes <500% of the federal poverty level in addition to a manufacturer copay assistance program that provides medication cost-sharing assistance for insured individuals.45 Although there is a robust policy debate about the sustainability of drug companies' patient assistance programs,46 this program has been an essential component to PrEP access to the point that it has been included in the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control's cost analysis of PrEP affordability.47

The federal government has launched a new PrEP program for uninsured individuals, “Ready, Set, PrEP,” to provide PrEP to people living in the United States who do not have prescription drug coverage, who have an HIV test with a negative result, and who have a prescription for PrEP.48 The Health Resources and Services Administration's Bureau of Primary Health Care has also been allocated funds to expand PrEP services through Community Health Centers that are also RWHAP grantees.49 Time will tell if these programs are as successful as the RWHAP in terms of providing a nationally available, federally funded comprehensive medical home for PLWH with low incomes that achieves excellent health outcomes.50 However, “Ready, Set, PrEP” does not seem to be as comprehensive as the RWHAP given that there are no funds to cover PrEP-related, quarterly medical visits or PrEP-related, quarterly labs.

Assisters in rural areas raised the concern that narrow provider networks make it more difficult to ensure that RWHAP clinicians and providers with whom clients already have a relationship are in-network. Assisters in rural areas also voiced that limited access to PrEP was often because of the lack of a clinician who would prescribe the medication, which is supported by recent research demonstrating that rural areas of the United States are more likely to be “PrEP deserts.”51

The second theme that arose was the complexity of coverage landscape. Assisters were clear that the enrollment periods are not long enough and that more advertisements are needed for healthcare.gov. They also requested stable, or ideally increased, transparency from healthcare.gov and insurance companies is needed to ensure that they can continue to perform at high levels. Given that some assisters have this job as a seasonal position, it makes their mastery of this complex system even more impressive. In addition, the assisters who were interviewed were engaged and had this knowledge. It is possible that the average national knowledge is less because our sample likely represents a motivated group.

The third overarching theme of engagement for informed choices highlighted that many assisters viewed insurance enrollment as an opportunity for education about how insurance works and many other health- and HIV-related topics. Assisters noted that basic insurance literacy is a significant barrier to insurance enrollment. Assisters reported needing to start with the basics of explaining how insurance works to ensure that clients understand how to use insurance once they have it. In a Kaiser Family Foundation study, HIV-focused navigators reported presenting an “Insurance 101” type of class to many people who newly gained insurance.36 It is unclear if this is standard practice, but likely leads to improved understanding of insurance coverage and possibly improved usage of insurance coverage.

This analysis has limitations, including that the data are perceptions of HIV insurance assisters who each have a specific professional context and may not understand all barriers faced by persons living with HIV and persons at increased risk for HIV. We do not know any information about the assisters who declined to participate. We used a nonprobability sampling strategy that may not be representative or generalizable. Finally, this study was cross-sectional in nature and relied on participants recalling past experiences that were temporal.

In a complex coverage landscape during a time of uncertainty about the long-term future of the ACA, assisters have mastered the ability to simplify the insurance selection process for a vulnerable population, those living with HIV and those at increased risk for HIV. Assisters have excelled at incorporating insurance literacy education and encouraging client engagement in care during the process, which aims to result in successful enrollment and access to care. Assisters play an essential role in the current complicated and fragmented United States' health care delivery system for PLWH and people at increased risk for HIV. Assisters could be incorporated into the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the state health departments for their assistance and the assisters who generously participated. The authors thank Michelle Hilgart, PhD, for assistance with the figure.

Appendix

Interview Guide

-

To begin, we will ask some basic questions about you and your employment

What type of company employs you? (e.g., state/local health department, community-based organization, clinic)

What area do you serve? (region, state, part of state, city?)

Is the area urban, rural, or a mix?

What is your title?

What does your role entail?

Are you a Certified Application Counselor (CAC), Navigator, or other licensed/trained enrollment assister?

-

How many years have you been providing plan assessment and enrollment support?

If >1, ask:

Have you worked as an insurance assister year-round or seasonally (e.g., during open enrollment only)? First, we would like to know about the types of plan assessment and enrollment assistance that you provide:

-

Do you provide education about public and private insurance options?

If so, can you tell us some of the information that you share?

-

Do you provide personalized assessment of plan options, including comparison of costs across plans?

If so, can you tell us more about how you do this?

And what resources or websites you use?

-

Do you refer people to CACs, Navigators, or other licensed assisters for plan enrollment?

If so, do you have a partnership with specific CACs or navigators?

If yes, how did you form that partnership?

Are there any other essential things that you do? Please describe them.

-

Next, we would like to get a sense of the number of clients that you assisted in the last Affordable Care Act (ACA) open enrollment period.

-

Approximately how many clients did you assist with marketplace plans?

If >0, then ask:

For those clients, what is an estimate of the proportion who were eligible for advance premium tax credits or cost-sharing reductions available through the marketplace?

If you assist clients in comparing individual market plans, please describe the different plan characteristics you think are most important for your clients (e.g., formulary coverage and tiering, prior authorization, premium costs, out-of-pocket maximum, deductible, provider network)?

Approximately how many clients assisted with off-marketplace individual plans?

Approximately how many clients assisted with employer-based coverage?

Approximately how many clients assisted with Medicaid?

Approximately how many clients assisted with Medicare?

-

-

Did you face any challenges during the last open enrollment period?

If so, please describe them.

-

Additional probing questions: Any difficulty with

Availability of plans—there were not many marketplace plan options for my clients

Narrow provider networks that didn't cover HIV/PrEP providers

High premiums

High deductibles

High prescription drug cost-sharing/co-insurance

Prior authorization for HIV drugs/PrEP

Confusion about non-ACA compliant options (e.g., short-term limited duration plans)

Uncertainty about the stability of the ACA

Other?

Have there been any successes with this role and model of assistance that you would like to share?

-

Without using any facts that would identify a client's situation, are there any stories that you would like to share?

Any that you would like to share about when you thought a navigator was critical?

Is there anything else about your experience assisting clients understand their insurance options and/or enroll in coverage that you would like to share?

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

K.A.M. reports investigator-initiated research funding from Gilead Sciences, Inc., K.A.M. reports stock ownership in Gilead Sciences, Inc. No competing financial interests exist for the other authors.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant number K08AI136644 to K.A.M.). This work was supported by the University of Virginia's 3 Cavaliers Program and the University of Virginia Global Infectious Diseases Institute through funding to K.A.M. and J.K.-M.

References

- 1. Kates J: Implications of the Affordable Care Act for people with HIV infection and the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program: What does the future hold? Top Antivir Med 2013;21:138–142 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marks SJ, Merchant RC, Clark MA, et al. : Potential healthcare insurance and provider barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:470–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y: Prescription drug cost sharing: Associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA 2007;298:61–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitfield THF, John SA, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Parsons JT: Why I quit pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? A mixed-method study exploring reasons for PrEP discontinuation and potential re-initiation among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3566–3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Claxton G, Cox C, Damico A, Levitt L, Pollitz K: Pre-existing condition prevalence for individuals and families. 2018. [cited April 28, 2020]. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/pre-existing-condition-prevalence-for-individuals-and-families

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Affordable Care Act helps people living with HIV/AIDS. 2019. [cited August 27, 2019]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/aca.html

- 7. Dawson L, Kates J. An update on insurance coverage among people with HIV in the United States. 2019. [cited August 27, 2019]. Available at: https://www.kff.org/report-section/an-update-on-insurance-coverage-among-people-with-hiv-in-the-united-states-findings

- 8. McManus KA, Rodney RC, Rhodes A, Bailey S, Dillingham R: Affordable Care Act qualified health plan enrollment for AIDS drug assistance program clients: Virginia's Experience and Best Practices. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016;32:885–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP: Ending the HIV epidemic: A plan for the United States. JAMA 2019;321:844–845. [cited June 28, 2019] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bradley H, Prejean J, Dawson L, Kates J, Shouse RL: Health care coverage and viral suppression pre- and post-ACA implementation. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2017 [cited April 28, 2020]. Available at: www.croiconference.org/sites/default/files/posters-2017/1012_Bradley.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhattacharya J, Goldman D, Sood N: The link between public and private insurance and HIV-related mortality. J Health Econ 2003;22:1105–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldman DP, Bhattacharya J, McCaffrey DF, et al. : Effect of insurance on mortality in an HIV-positive population in care. J Am Stat Assoc 2001;96:883–894 [Google Scholar]

- 13. McManus KA, Rhodes A, Bailey S, et al. : Affordable Care Act qualified health plan coverage: Association with improved HIV viral suppression for AIDS Drug Assistance Program Clients in a Medicaid Nonexpansion State. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:396–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Furl R, Watanabe-Galloway S, Lyden E, Swindells S: Determinants of facilitated health insurance enrollment for patients with HIV disease, and impact of insurance enrollment on targeted health outcomes. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McManus KA, Christensen B, Nagraj VP, et al. : Evidence from a multistate cohort: Enrollment in Affordable Care Act qualified health plans' association with viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis 2019:ciz1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kay ES, Pinto RM: Is insurance a barrier to HIV preexposure prophylaxis? Clarifying the issue. Am J Public Health 2020;110:61–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC Jr, et al. : Retention in care: A challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:1493–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, et al. : Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373:795–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. : Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Castilla J, Del Romero J, Hernando V, Marincovich B, Garcia S, Rodriguez C: Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;40:96–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. : Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 2016;316:171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. : Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): Final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet (London, England) 2019;393:2428–2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Serota DP, Rosenberg ES, Thorne AL, Sullivan PS, Kelley CF: Lack of health insurance is associated with delays in PrEP initiation among young black men who have sex with men in Atlanta, US: A longitudinal cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22:e25399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. King A, Pulsipher C, Holloway I: PrEP Cost Analysis for Covered California Health Plans. 2016. [cited April 28, 2020]. Available at: http://getprepla.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/11-7-16-UCLA-PrEP-Policy-Brief.pdf

- 25. Jaiswal J, Griffin M, Singer SN, et al. : Structural barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis use among young sexual minority men: The P18 cohort study. Curr HIV Res 2018;16:237–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V: Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:102–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pleuhs B, Quinn KG, Walsh JL, Petroll AE, John SA: Health care provider barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: A systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2020;34:111–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Riddell J 4th, Amico KR, Mayer KH: HIV preexposure prophylaxis: A review. JAMA 2018;319:1261–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Farnham PG, Gopalappa C, Sansom SL, et al. Updates of lifetime costs of care and quality-of-life estimates for HIV-infected persons in the United States: Late versus early diagnosis and entry into care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64:183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sandelowski M: What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 2010;33:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sandelowski M: Focus on research methods-whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cohen MZ, Kahn DL, Steeves RH: Hermeneutic Phenomenological Research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clarke A: Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Postmodern Turn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 34. McManus KA, Debolt C, Elwood S, et al. : Facilitators and barriers: Clients' perspective on the Virginia AIDS Drug Assistance Program's Affordable Care Act Implementation. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2019;35:734–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pollitz K, Tolbert J, Diaz M: Data Note: Limited Navigator Funding for Federal Marketplace States. 2019. [cited November 27, 2019]. Available at: https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/data-note-further-reductions-in-navigator-funding-for-federal-marketplace-states

- 36. Kaiser Family Foundation. Implications of Navigator Funding Changes on People with HIV: Navigator Perspectives. 2017. [cited August 28, 2019]. Available at: https://www.kff.org/hivaids/issue-brief/implications-of-navigator-funding-changes-on-people-with-hiv-navigator-perspectives

- 37. Reif S, Safley D, McAllaster C, Wilson E, Whetten K: State of HIV in the US Deep South. J Community Health 2017;42:844–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. NASTAD. NASTAD PrEP cost calculator. 2019. [cited November 27, 2019]. Available at: https://nastad.checkbookhealth.org/prepcost/2020

- 39. Covered California. Information for individuals with hIV or AIDS. 2019. [cited November 27, 2019]. Available at: https://www.coveredca.com/individuals-and-families/special-circumstances/hiv-or-aids

- 40. The National Health Law Program. NHeLP and the AIDS Institute Complaint to HHS Re HIV/AIDS Discrimination by FL. 2014. [cited December 17, 2019]. Available at: https://healthlaw.org/resource/nhelp-and-the-aids-institute-complaint-to-hhs-re-hiv-aids-discrimination-by-fl

- 41. Jacobs DB, Sommers BD: Using drugs to discriminate—Adverse selection in the insurance marketplace. N Engl J Med 2015;372:399–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee R: HIV/AIDS group: Insurance companies discriminating against Georgians living with HIV. 2017. [cited December 16, 2019]. Available at: chlpi.org/hivaids-group-insurance-companies-discriminating-georgians-living-hiv

- 43. Beer L, Tie Y, Weiser J, Shouse RL: Nonadherence to any prescribed medication due to costs among adults with HIV infection—United States, 2016–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1129–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019. Letter to issuers in the federally-facilitated exchanges. 2018. [cited December 18, 2019]. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Regulations-and-Guidance/Downloads/2019-Letter-to-Issuers.pdf

- 45. Gilead Sciences. Advancing access. 2019. [cited December 17, 2019]. Available at: https://www.gileadadvancingaccess.com

- 46. Howard DH: Drug companies' patient-assistance programs—Helping patients or profits? N Engl J Med 2014;371:97–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith DK, Van Handel M, Huggins R: Estimated coverage to address financial barriers to HIV preexposure prophylaxis among persons with indications for its use, United States, 2015. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:465–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Ready, Set, PrEP. 2019. [cited December 13, 2019]. Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/prep-program

- 49. Health Resources and Services Administration. FY 2020 Ending the HIV Epidemic-Primary Care HIV Prevention Supplemental Funding Technical Assistance (HRSA-20-091). 2019. [cited November 27, 2019]. Available at: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/program-opportunities/funding-opportunities/primary-care-hiv-prevention

- 50. Health Resources and Services Administration. Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program Annual Client-Level Data Report 2018. 2019. [cited December 13, 2019]. Available at: https://hab.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hab/data/datareports/RWHAP-annual-client-level-data-report-2018.pdf

- 51. Siegler AJ, Bratcher A, Weiss KM: Geographic access to preexposure prophylaxis clinics among men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health 2019;109:1216–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]