Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes a severe acute respiratory syndrome, a characteristic hyperinflammatory response, vascular damage, microangiopathy, angiogenesis and widespread thrombosis. Four stages of COVID-19 have been identified: the first stage is characterised by upper respiratory tract infection; the second by the onset of dyspnoea and pneumonia; the third by a worsening clinical scenario dominated by a cytokine storm and the consequent hyperinflammatory state; and the fourth by death or recovery. Currently, no treatment can act specifically against the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Based on the pathological features and different clinical phases of COVID-19, particularly in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19, the classes of drugs used are antiviral agents, inflammation inhibitors/antirheumatic drugs, low molecular weight heparins, plasma, and hyperimmune immunoglobulins. During this emergency period of the COVID-19 outbreak, clinical researchers are using and testing a variety of possible treatments. Based on these premises, this review aims to discuss the most updated pharmacological treatments to effectively act against the SARS-CoV-2 infection and support researchers and clinicians in relation to any current and future developments in curing COVID-19 patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Antiviral agents, Inflammation inhibitors, Antirheumatic drugs, Low molecular weight heparins

1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is an RNA virus genetically located within the genus Betacoronavirus that uses a glycoprotein (spike protein) to bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. After binding, the serine protease TGRBSS2 facilitates virus entry into the cell (Matricardi et al., 2020). The results of a recent study (Long et al., 2020) on COVID-19 patients showed that 100% of patients tested positive for IgG about 17–19 days following the onset of symptomatology, with a peak of 94.1% after 20–22 days. In addition, the study found that there was an increase in SARS-CoV-2 specific IgG and IgM antibody titres after the first 3 weeks following the onset of symptomatology, but no correlation was found between IgG levels and patients’ clinical characteristics (Long et al., 2020). Following infection with SARS-CoV-2 some infected individuals may remain asymptomatic or only present with mild upper respiratory symptoms, others develop pneumonia and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) that requires intubation in intensive care and presents complications with an inauspicious outcome. A model (Matricardi et al., 2020) has recently been published based on literature studies in which it is emphasised that the balance between the cumulative dose of viral exposure and the efficacy of the local innate immune response (IgA, IgM, MBL antibodies) is crucial in the evolution of COVID-19. In particular, this model identifies the first stage of COVID-19, which is characterised by upper respiratory tract infection, accompanied by fever, muscle fatigue and pain. Nausea or vomiting and diarrhoea are infrequent in this initial stage of the disease. The second stage is characterised by the onset of dyspnoea and pneumonia.

The third stage is characterised by a worsening clinical scenario dominated by a cytokine storm and the consequent hyperinflammatory state that determines local and systemic consequences causing arterial and venous vasculopathy in the lung with thrombosis of the small vessels and evolution towards serious lung lesions up to ARDS and in some cases to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (Matricardi et al., 2020; Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020 a). Acute cardiac and renal damage, sepsis and secondary infections were the other complications most frequently reported in this phase (Huang et al., 2020). The fourth stage is characterised by death or recovery (Matricardi et al., 2020). Mortality is associated with advanced age, the presence of comorbidities, greater disease severity, worsening of respiratory failure, high levels of D-Dimer and C-reactive protein, low lymphocyte counts and infections (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020 a).

Currently, no treatment is very effective in treating the SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the classes of drugs that are mainly used include antiviral agents, inflammation inhibitors, low-molecular-weight heparins, plasma, and hyperimmune immunoglobulins. Based on the pathological features and different clinical stages of COVID-19, clinical researchers are using and testing a variety of possible treatments. In the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infections, antiviral agents could prevent the progression of the disease, whilst immunomodulatory plus antiviral agents appear to improve clinical outcomes in patients with critical COVID-19.

Based on these premises, this review aims to discuss the above mentioned pharmacological treatments to combat the infection and support researchers and clinicians in current and future developments for curing COVID-19 patients. More specifically, this review summarises the main therapeutic strategies that have been proposed so far for COVID-19 in randomised controlled trials, clinical and experimental research studies, case series, and observational retrospective and longitudinal studies, providing a summary (Table 1 ) of the different classes of drugs used and also highlighting the different stages in which these drugs improve symptomatology or decrease the mortality rate.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the overviewed studies and their findings.

| Studies, Year | Study Design | Main inclusion criteria | No of patients/Enrollment | Interventions/treatments | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cao, B. et al., 2020. Chinese Clinical Trial Register number, ChiCTR2000029308. |

Randomised, controlled, open-label trial | Hospitalised adult SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, and 94% SaO2 (ambient air) or a PaO2/Fio2 ratio < 300 mm Hg | 199 patients January 18, 2020–February 3, 2020. |

Patients randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either lopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg and 100 mg, respectively) b.id. for 14 days plus SOC or SOC alone. | Similar mortality rate observed in lopinavir – ritonavir group and SOC group (19.2% vs. 25.0%; difference, −5.8 percentage points; [95% CI, −17.3 to 5.7]). No benefit observed in Lopinavir–Ritonavir group vs SOC group. |

| Grein, J. et al., 2020. | Compassionate-use cohort. | Hospitalised adult SARS-CoV-2 infected patients and 94% SaO2 (ambient air) or receiving oxygen support | 53 patients January 25, 2020,- March 7, 2020 |

Patients received a 10-day course of Remdesivir (200 mg i.v. on day 1, and 100 mg daily for the remaining 9 days) | Clinical improvement observed in 36 of 53 patients (68%). |

| Beigel, J.H. et al., 2020. ClinicalTrials.gov Register number, NCT04280705. |

Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Hospitalised adult SARS-CoV-2 infected patients and ≤94% SaO2 | 1063 patients February 21, 2020–April 19, 2020 | Patients randomly assigned to receive either Remdesivir (200 mg on day 1, and 100 mg daily for up to 9 additional days) or placebo for up to 10 days | A 10-day course of Remdesivir was superior to placebo in number of days to recovery (median, 11 vs 15 days; recovery rate ratio, 1.32 [95% CI, 1.12 to 1.55]) and in recovery according to ordinal scale score at day 15 (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.18 to 1.91). |

| Guaraldi, Gul et al., 2020. | Retrospective, observational cohort study | Adults (≥18 years) with severe COVID-19 pneumonia, admitted to tertiary care centres | 1351 patients February 21, 2020–April 30, 2020. |

All patients treated with SOC (ie, supplemental oxygen, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, antiretrovirals, and low molecular weight heparin), and a non-randomly patients' selected subset also received tocilizumab. | Reduced risk of invasive mechanical ventilation or death (AHR: 0·61, 95% [CI 0·40–0·92]; p = 0·020) observed in Tocilizumab group |

| Cantini, F. et al., 2020. | Observational, retrospective, longitudinal study | Hospitalised adults with COVID-19 moderate pneumonia | 191 patients February 20, 2020–May 5, 2020. | 113 patients treated for 2 weeks with Baricitinib 4 mg/day p.o. plus lopinavir/ritonavir tablets 250 mg/bid; Control-arm: 78 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine plus lopinavir/ritonavir. |

2-week case fatality rate was significantly lower in the Baricitinib-arm vs controls; ICU admission was requested in 0.88% (1/113) vs 17.9% (14/78) patients in baricitinib-arm vs control-arm; discharge rate was significantly higher in the Baricitinib-arm. |

| RECOVERY Collaborative Group, 2020. Clinicaltrial.gov Register number NCT04381936 |

- Randomised controlled, open-label trial | 1. Aged at least 18 years 2. Hospitalised 3. SARS-CoV-2 infection (suspected or confirmed) 4. No medical history that might, in the opinion of the attending clinician, put the patient at significant risk if he/she were to participate in the trial |

11,303 patients March 19, 2020–June 8, 2020 | Drug: Lopinavir-Ritonavir Drug: Corticosteroid Drug: Hydroxychloroquine Drug: Azithromycin Biological: Convalescent plasma Drug: Tocilizumab |

Among patients in ordinary care program, 28-day mortality was higher or intermediate in those needed ventilation or only oxygen, respectively. In dexamethasone group, mortality was 1/3 lower in ventilated patients and 1/5 lower in oxygen-treated subjects. Follow-up was completed for over 94% of the enrolled patients. |

| Tang, N. et al., 2020. | Retrospective, cohort study | Hospitalised adult patients with severe COVID-19 | 449 patients January 1, 2020–February 13, 2020 | All patients received antivirals and appropriate supportive therapies after admission. Ninety-nine (22.0%) patients received heparin treatment for up to 7 days. |

No difference in 28-day mortality in heparin users and nonusers (30.3% vs 29.7%, P = 0.910). The 28-day mortality of heparin users was lower than nonusers in patients with SIC score ≥4 (40.0% vs 64.2%, P = 0.029), or D-dimer >6-fold of upper limit of normal (32.8% vs 52.4%, P = 0.017). |

| Shen, Cao et al., 2020. | Case series | Adult COVID-19 patients and ARDS and the following criteria: severe pneumonia with rapid progression and continuously high viral load despite antiviral treatment; PaO2/FiO2 <300; and mechanical ventilation. | 5 patients January 20, 2020–March 25, 2020 |

Patients received convalescent plasma (between 10 and 22 days after admission) with a SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody (IgG) binding titer > 1:1000 and a neutralization titer > 40 obtained from 5 recovered COVID-19 patients | Improvement in clinical status |

| Goldman, J.D. et al., 2020 Clinicaltrial.gov Register number NCT04292899 |

Randomised, open-label trial | Hospitalised patients (age>12 years) SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by PCR within 4 days before randomization No mechanically ventilated |

397 patients | Patients randomly assigned (1:1) to receive Remdesivir i.v. for either 5 days or 10 days (200 mg on day 1 and 100 mg daily on subsequent days). | By day 14, a clinical improvement >2 points on the ordinal scale occurred in 64% of patients in 5-day group and in 54% in 10-day group. After adjustment for baseline clinical status, similar clinical status at day 14 was found in 10-day group and 5-day group (P = 0.14). |

| Adaptive Randomised trial for therapy of COrona virus disease 2019 at home with oral antivirals (ARCO-Home study), 2020 Eu CT number: 2020-001528-32 |

Multi-arm parallel randomised controlled clinical trial - (five-arms). | Adult (age ≥18 years) with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic for < 5 days before starting therapy and without criteria for immediate hospitalisation. | Expected sample size: 175–435 within two months of the start of the project (April 20, 2020). | Control arm. No specific antiviral treatment. Arm-1. One tablet of Darunavir (800 mg) + Cobicistat (150 mg) for 14 days. Arm-2. Two tablets of Hydroxychloroquine (each tablet = 200 mg) b.i.d. on day 1 and one tablet b.i.d. on day 2 to day 10. Arm-3. Two tablets of Lopinavir/Ritonavir b.i.d. for 14 days. Each tablet contains 200 mg of Lopinavir and 50 mg of Ritonavir. Arm-4. Nine tablets of favipiravir (each tablet = 200 mg) b.i.d. on day 1 and 4 tablets b.i.d. on day 2 to day 10. |

Ongoing No results available |

| A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with severe covid-19 pneumonia, 2020 Eu CT number: 2020-001154-22 |

Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Adult hospitalised patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia | 330 patients (Date of Approval: March 30, 2020) | Patients randomly assigned (2:1) to receive blinded treatment of either Tocilizumab (one or two doses of tocilizumab i.v., at a dose of 8 mg/kg to a maximum of 800 mg per dose) or a matching placebo (one or two doses), respectively. | Ongoing No results available |

| Efficacy and Safety of Emapalumab and Anakinra in Reducing Hyperinflammation and Respiratory Distress in Patients With COVID-19 Infection, 2020 Clinicaltrial.gov Register number NCT04324021 |

Open label, controlled, parallel group, 3-arm | Hospitalised SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (age > 30 to < 80 years), diagnosis as per hospital routine | 54 patients (Date of Approval: April 20, 2020) |

Active arm: Emapalumab (infusion every 3rd day for a total 5 infusions, at day 1: 6 mg/kg and at the other days: 3 mg/kg) Active arm: Anakinra (400 mg/day in total, divided into 4 doses given every 6 h for 15 days)No Intervention: SOC according to local practice |

No results available |

| BARICIVID-19 STUDY: MultiCentre, randomised, Phase IIa clinical trial evaluating efficacy and tolerability of Baricitinib as add-on treatment of patients with COVID-19 compared to standard therapy, 2020 Eu CT number: 2020-001955-42 |

Multicenter randomised controlled PoC (phase IIa) clinical trial | Adult hospitalised patients COVID-19 pneumonia | 126 patients (Date of Approval: April 22, 2020) |

All patients were treated with SOC. 63 patients received baricitinib 4 mg p.o., 1 tablet daily for 14 days. Patients with eGFR >30 and < 60 mL/min and those with age >75 years was treated with ½ tablet daily (2 mg) for 14 days. The control group (63 patients) was treated with SOC |

No results available |

| U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov, 2020 b. Convalescent Plasma vs. Standard Plasma for COVID-19, 2020 Clinicaltrial.gov Register number NCT04344535 |

Randomised, Parallel Assignment | Adults hospitalised with COVID-19 infection | 500 patients (Date of Approval: August 4, 2020) |

Active arm: Convalescent Plasma 450–550 mL of plasma containing anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer ideally > 1:320 (minimum titer per FDA Guidelines for convalescent plasma).Control arm: Standard Donor Plasma 450–550 mL of plasma with low titer to anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies |

No results available |

Abbreviations: SaO2: oxygen saturation; PaO2/Fio2 ratio: partial oxygen pressure (PaO2)/inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2); b.i.d.: bis in die; SOC: standard of care; i.v.: intravenous; CI: confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; PCR: polymerase-chain-reaction; AHR: adjusted hazard ratio; p.o.: per os.

2. Treatment for COVID-19

2.1. Antiviral agents

Several protease inhibitors (e.g. darunavir, atazanavir) currently used for treating HIV could inhibit the viral replication of SARS-CoV-2 by inactivating the proteases, which are fundamental for replication. The Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco - AIFA) approved the ARCO-Home study that aims to test the efficacy of darunavir-cobicistat, lopinavir-ritonavir, favipiravir and hydroxychloroquine as therapies at home in an early COVID-19 population to prevent the progression of the infection towards serious or critical clinical forms with the need to resort to hospitalisation and invasive procedures such as intubation (Documents - AIFA, 2020).

We will review herein some of the evidence on treatment with protease inhibitors, nucleotide analogues, and new antiviral agents in the treatment of different stages of COVID-19.

2.1.1. Lopinavir/ritonavir

The main drugs used in the context of the national emergency management plan for COVID-19 include lopinavir/ritonavir, which is mainly used in COVID-19 patients with less severe symptoms and in the early stages of the disease, managed both at home and in the hospital. Previous experiences with SARS-CoV-1 and MERS infections suggest that this drug may improve some patients’ clinical parameters (Gul et al., 2020). A randomised, controlled, open-label study on oral lopinavir-ritonavir for severe COVID-19 involved 199 hospitalised adult patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 (Cao et al., 2020). In addition to the infection criterion, the enrolled patients had an oxygen saturation (SaO2) of 94% or less during respiration in ambient air or a ratio between partial oxygen pressure (PaO2) and inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2) of less than 300 mm Hg. Patients were randomly assigned to receive lopinavir-ritonavir in addition to standard therapy. The control group was treated with standard care only (N = 100 patients). The primary endpoint was the time to clinical improvement. Despite the important effort of the researchers who carried out a randomised clinical trial during a pandemic emergency, the results did not have the expected effects. Lopinavir-ritonavir therapy was not associated with significant clinical improvements compared to standard therapy, nor was it associated with improvements in 28-day mortality and the nasopharyngeal persistence of viral RNA detected at different time points.

2.1.2. Remdesivir

Remdesivir, belonging to the class of nucleotide analogues, was previously used in the Ebola virus epidemic in Africa and is currently used in moderate and severe COVID-19. Grein et al. (2020) described the results of data analysis of the compassionate use of remdesivir in a small cohort of severe COVID-19 patients. Clinical improvement was found in 36 out of 53 patients in whom it was possible to analyse the data (68%). Of the sixty-one subjects that underwent remdesivir treatment, statistics from eight of these were not analysed (7 subjects had no post-treatment data and 1 had a dosage error). Of the fifty-three subjects for whom it was viable to analyse the data, thirty subjects (57%) underwent mechanical ventilation and four (8%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Patients receiving invasive ventilation were older than those receiving non-invasive oxygen help at baseline, they were mainly men, had greater ranges of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and creatinine and a greater occurrence of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and bronchial asthma. Although limited, the study results show that remdesivir may also have therapeutic advantages in patients with severe Covid-19.

Goldman et al. (2020) published the first results of the phase 3 trial (randomised, open-label) on the use of remdesivir in hospitalised patients. Remdesivir was administrated for 5 or 10 days in patients with severe Covid-19. Patients who received concomitant treatment (within 24 h before starting remdesivir treatment) with other potentially active drugs against Covid-19 were excluded. Patients were randomly divided in a 1:1 ratio for intravenous administration of remdesivir for 5 or 10 days at a dosage of 200 mg on day 1 and 100 mg once a day on the following days. The primary endpoint of the trial was to evaluate the clinical status on day 14. Three hundred and ninety-seven patients were randomised (200 patients in the group on therapy for 5 days and 197 on therapy for 10 days).

Among those who did not participate in the entire therapy for 10 days, motives included clinic discharge, unfavourable events and dying (6%). On day 14, clinical improvement was found in 64% of patients in the 5-day treatment group and 54% in the 10-day group. The authors conclude that the effects discovered exhibit no great distinction in effectiveness between a 5-day and a 10-day cycle of intravenous administration of remdesivir in patients with severe Covid-19 who required mechanical ventilation at baseline, and although further studies on high-risk groups are needed to establish the shortest period of therapy, they suggest that patients undergoing mechanical ventilation could benefit from 10-day treatment with remdesivir.

A new randomised controlled trial (NCT04280705) was conducted on 1063 patients, with the same dosing cycle and administered dose of remdesivir used in the compassionate use of this antiviral agent in a small cohort of patients (Beigel et al., 2020). Beigel et al. (2020) presented data on 1059 patients, including 538 assigned remdesivir and 521 on placebos. Sixty main and 13 secondary centres were involved in this trial. The average age of the patients was 58.9 years and 64.3% were male. Available data showed that patients assigned remdesivir treatment had an average hospitalisation time of 11 days, compared to 15 days on placebos, with a mortality estimate of 7.1% in remdesivir-treated patients compared to 11.9% of those on placebos. The results of the study suggest starting remdesivir treatment early before lung disease progression requiring mechanical ventilation.

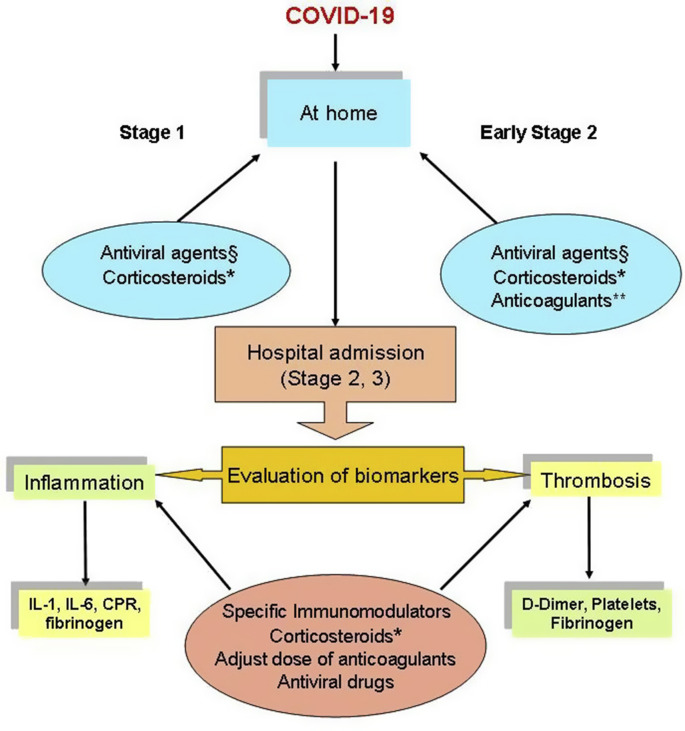

Based on these studies, our opinion is that some antivirals are promising in paucisymptomatic patients to prevent the progression of the SARS-CoV-2 infection (U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov, 2020a ; U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov, 2020b .) and remdesivir appears to shorten recovery times for hospitalised patients (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

A proposed potential therapeutic algorithm based on current studies and clinical trials

§ In the early stages of COVID-19, one or a combination of antiviral agents could be used as a prophylactic or early treatment option to decrease viral load, transmission and prevent progression to the later stage of the disease. The early treatment is under evaluation in some clinical trials (U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov, 2020a; U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov, 2020b)

*In the early stage, specific adjustment of glucocorticoid therapy could be needed based on specific reasons (i.e. in adrenal insufficient patients (Isidori et al., 2000)). WHO suggests not to use corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with non-severe COVID-19 as the treatment brought no benefits (World Health Organization, 2020 b).** Based on the clinical status, anticoagulants could be administered to prevent thrombotic phenomena starting from the pulmonary circulation as a consequence of hyperinflammation.

Several studies showed that inflammatory cytokines (Il-1, IL-6), c-reactive proteins (CPR), fibrinogen, D-Dimer, ferritin and other biomarkers are significantly elevated in patients with more advanced disease. Therefore, specific immunomodulators and corticosteroids are useful to counteract and prevent the cytokine storm and anticoagulants to prevent thrombotic events. The antiviral remdesivir appears to shorten recovery times for hospitalised patients.

2.1.3. New molecules

Dai et al. (2020) developed 2 molecules capable of blocking the protease enzyme that allows replication of SARS-CoV-2: molecules 11a and 11b. To verify the enzyme's inhibitory activity, the research team assessed the capacity of these molecules to interfere with SARS-CoV-2 activity in cell cultures in vitro. Both molecules showed satisfactory anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity in cell culture. Furthermore, neither of the two compounds caused significant cytotoxicity. Both the immunofluorescence method and the quantitative PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) were used to detect the antiviral activity of 11a and 11b in real-time. Study results showed that 11a and 11b had an acceptable antiviral effect on SARS-CoV-2. To discover the further pharmacological potential of 11a and 11b molecules, both have been investigated for their pharmacokinetic properties in animal experiments. The intraperitoneal and intravenous administration of compound 11a had a half-life (T1/2) of 4.27 h and 4.41 h, respectively, a high maximum concentration (Cmax = 2394 ng/mL), and a bioavailability of 87.8% when compound 11a was administered intraperitoneally. The metabolic stability of 11a in mice was also good. Compound 11b, when administered intraperitoneally (20 mg/kg), subcutaneously (5 mg/kg) and intravenously (5 mg/kg), showed good pharmacokinetic properties (intraperitoneal and subcutaneous bioavailability was 80% greater, and a half-life longer than 5.21 h was recorded when 11b was administered intraperitoneally). Further pharmacokinetic trials (area under the curve - AUC, half-life and clearance rate) of the intravenous compounds suggested further studies on compound 11a. An in vivo toxicity study, conducted on animals, did not demonstrate obvious toxicity by suggesting that molecule 11a may represent a good candidate for human clinical trials.

2.2. Immunomodulatory drugs

Numerous experimental and clinical pieces of evidence have shown that an important part of the damage caused by the virus is linked to an altered inflammatory response and, in some patients, to an abnormal release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon-gamma, and tumour necrosis factor alpha. For this reason, in addition to being based on previous experience demonstrated in patients with SARS, anti-inflammatory drugs (particularly monoclonal antibodies) are used in the COVID-19 emergency, which have been used in rheumatology for some years to inhibit the immune response. In this section, we will discuss the possible role played by anti-IL6, anti-IL-1, JAK inhibitors, corticosteroids, antimalarials, heparins, and immunoglobulins, particularly in the treatment of moderate/severe COVID-19.

2.3. Tocilizumab

The most used drug in the therapy of COVID-19 was Tocilizumab (antibody directed against the Il-6 receptor). This drug was authorised by AIFA on 3 April in a phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind study to investigate its safety and efficacy (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020b). Subsequently, AIFA made a summary of the Italian non-comparative study on tocilizumab “TOCIVID-19″ available, promoted by the National Cancer Institute of Naples. Although it has some limitations, the results suggest that the drug can significantly reduce mortality at one month, while its impact is less relevant on early mortality (14 days) (Executive summary – AIFA, 2020). The results of the retrospective observational cohort study by Guaraldi et al. (2020) included adults (≥18 years) with severe COVID-19 pneumonia, hospitalised at the tertiary care centres of Bologna and Reggio Emilia between 21 February and March 24, 2020, and at a tertiary assistance centre in Modena between 21 February and April 30, 2020. The purpose of this multicentre study was to evaluate the efficacy of Tocilizumab treatment in addition to usual care in reducing mortality and the likelihood of invasive mechanical ventilation in a cohort of patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia compared to the cohort of patients who received standard treatment.

Patients were regarded as eligible for tocilizumab therapy if they had a SaO2 of less than 93% and a partial oxygen pressure (PaO2)/inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2) ratio of less than 300 mm Hg in ambient air or a reduction of over 30% in the PaO2/FiO2 ratio in the 24 h preceding hospitalisation. Of the 1351 patients admitted, 544 (40%) with severe COVID-19 pneumonia were included in the study. The usual care group included older patients with less severe cases of the disease and the group treated with intravenous tocilizumab included the most compromised patients. Of the 365 patients treated with the usual care, 57 (16%) needed mechanical ventilation, whilst of the 179 patients treated with tocilizumab, 33 (18%) needed mechanical ventilation. New episodes of infection were carefully monitored in the group treated with tocilizumab compared to the group with standard therapy, of the 179 total patients who underwent tocilizumab treatment, new infections were diagnosed in 24 patients (13%), compared to 14 (4%) of the 365 patients treated with usual care. 20% of the patients treated with usual care died, compared with 7% of patients treated with tocilizumab. The authors concluded that both the intravenous and subcutaneous administration of tocilizumab may be able to reduce the risk of invasive mechanical ventilation or death in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Even if the results of the study are promising, they should be confirmed through ongoing randomised trials.

On 17 June, the preliminary results of the “RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 - Early Administration of Tocilizumab” study, which was carried out in 24 Italian centres, were published on the AIFA website (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020c). This multi-centre, open-label study mainly aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the early administration of tocilizumab in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

The study estimated the enrolment of 398 patients, but the analysis of data carried out on 123 enrolled patients showed a similar rate of aggravation in the first two weeks in patients randomised to receive tocilizumab compared to patients randomised to receive standard therapy (28.3% vs. 27.0%). No significant differences were observed in the total number of ICU admissions (10.0% vs 7.9%) and 30-day mortality rate (3.3% vs 3.2%). The researchers therefore concluded that the early administration of tocilizumab in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia does not provide any relevant clinical benefit for patients. Simultaneously, they stressed the need for further investigation to evaluate the efficacy of the drug in specific patient subgroups.

At the Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale (ASST or Local Healthcare Area) Spedali Civili di Brescia, the data of 1525 patients with rheumatic or musculoskeletal diseases were collected (Fredi et al., 2020): 117 (8%) presented symptoms compatible with COVID-19, of whom 65 returned a positive SARS-CoV-2 swab, while 52 had a spectrum of symptoms indicative of COVID-19 but had not been tested with a swab. Patients with confirmed COVID-19 were older than those with suspected COVID-19 (average age of 68 and 57 respectively) and were more likely to have high blood pressure (51% vs 27%) and be obese (17% vs 2%). There were no differences in rheumatologic disease or background therapy between confirmed and suspected COVID-19 patients. Of the 65 patients with confirmed COVID-19, 47 (72%) developed pneumonia that required hospitalisation. There were 12 (10%) deaths among the total 117 patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 (ten of them had confirmed COVID-19 and two of them had suspected COVID-19). Patients who died with confirmed COVID-19 were older than patients who survived. The case-control study included 26 patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases and COVID-19 pneumonia and 62 corresponding controls. There was no significant difference between cases and controls in the duration of COVID-19 symptoms before admission, the length of hospital stays or the Brescia-COVID Respiratory Severity Scale score. Of 26 patients, glucocorticoids were used in 17 (65%) for severe respiratory manifestations related to lung involvement, while tocilizumab was used in six (23%); thrombotic events occurred in four (15%) out of 26 cases. Four (15%) out of 26 cases and six (10%) out of 62 controls died during the study period. In patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, the poor prognosis was associated with older age and the presence of comorbidities.

2.3.1. Anakinra

A recent letter by Mehta et al. (2020) suggested that screening COVID-19 patients for hyper inflammation and subsequently treating them with immunosuppressant drugs could improve mortality rates. These include anakinra inhibitors IL-1α and IL-1β proinflammatory cytokines, which were administered with some benefit in the treatment of macrophage activation syndrome caused by various inflammatory conditions and were also administered in several studies on patients with COVID-19. King et al. (2020) support this scientific background for targeting hyperinflammation with anakinra in COVID-19 patients, emphasising several aspects of its use, patient selection, dosage and outcome measures. Although it has been found that serum ferritin and IL-6 levels are highly associated with hyperinflammation, in the absence of validated diagnostic criteria, recognition is often delayed. The authors suggest a practical approach to patient selection dependent on the investigation of the presence of severe COVID-19 and increased inflammation, such as worsening lymphocytopenia (a marker of progression and severity of COVID-19) and assessment of classification of C-reactive as an indication of worsening inflammation. The dose and administration of anakinra are particularly relevant. Due to its short plasma half-life, both intravenous and subcutaneous administration should be taken into consideration. A short half-life is useful to limit the duration of the drug's action in case of adverse effects, but variation in the dosage must be avoided for a constant and guaranteed bioavailability and to avoid a harmful rebound of inflammation. Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that the subcutaneous route could guarantee an adequate plasma concentration with a bioavailability ranging from 80 to 95%. The studies conducted so far report different endpoints in most cases. The authors therefore suggest, in current and future studies, a fundamental core of data. The effectiveness of emapalumab, a monoclonal anti-interferon gamma antibody, and anakinra, a receptor antagonist for IL-1, are being evaluated in a phase 2/3, in a multi-centre study aimed at reducing hyperinflammation and respiratory distress in patients with the new coronavirus infection (U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov, 2020c).

2.3.2. Baricitinib

Richardson et al. (2020) suggest baricitinib as a possible therapy for acute respiratory disease caused by COVID-19. Baricitinib is an inhibitor of Janus kinases (enzymes involved in the transduction of the cytokine-mediated signal). The Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020a) authorised a clinical trial, which is currently in progress, on the use of baricitinib as an add-on treatment in patients with COVID-19 compared to standard therapy. The primary objective is to evaluate the effectiveness of baricitinib in decreasing the need for invasive ventilation after 7 and 14 days of treatment. The secondary objectives were to evaluate: the mortality rate 14 and 28 days after randomization; the invasive mechanical ventilation time; independence from non-invasive mechanical ventilation; independence from oxygen therapy; improvement of oxygenation for at least 48 h; the length of hospital stay and stay in intensive care; the instrumental response (pulmonary ultrasound); and the description of the toxicity of baricitinib. Cantini et al. (2020) conducted an observational, retrospective, longitudinal multi-centre study in 7 Italian hospitals with COVID-19 moderate pneumonia patients to evaluate the 2-week effectiveness and safety of baricitinib plus antivirals (lopinavir/ritonavir) compared with the standard of care therapy. In this study, 113 patients were treated with baricitinib and 78 were treated with usual care. The results showed that the 2-week case fatality rate was significantly lower in patients treated with baricitinib compared with controls. Moreover, as highlighted by the authors, treatment with baricitinib was started in the early phase of the COVID-19 disease (the median time was 7-days from the onset of symptomatology), which may explain the low number of intensive care unit admissions and deaths.

2.3.3. Corticosteroids

COVID-19 patients over the age of 18 may be invited to participate in the UK's randomised RECOVERY Trial (Randomised evaluation, 2020). The RECOVERY Trial aims to identify effective drugs in the treatment of adults hospitalised with COVID-19, particularly focusing on: low dosage dexamethasone; lopinavir-ritonavir; hydroxychloroquine; azithromycin; and tocilizumab. The trial is designed to have the lowest possible impact on the health service. The trial data are periodically reviewed so that any effective treatment identified can be quickly made available to all patients. There are currently 170 centres and 6232 patients involved in the United Kingdom. Preliminary results (Horby et al., 2020) of the randomised RECOVERY clinical trial aimed at evaluating the efficacy of potential treatments for COVID-19, including low-dose dexamethasone (corticosteroid), have recently been published. Altogether, the study enrolled 11,500 patients from over 175 NHS hospitals in the UK. In terms of the cohort referred for the use of dexamethasone, 2104 patients were randomly enrolled for the administration of dexamethasone 6 mg once a day (intravenously or orally) for ten days, compared with a control group consisting of 4321 randomised patients who were only administered ordinary treatments. Among patients undergoing the ordinary care programme, 28-day mortality was higher or intermediate in those who needed ventilation or only oxygen, respectively. In the dexamethasone group, mortality was one third lower in ventilated patients and one fifth lower in oxygen-treated subjects. Follow-up was completed for over 94% of the enrolled patients.

WHO suggests not to use corticosteroids in non-severe COVID-19 as the treatment brought no benefits (World Health Organization, 2020 b).

Based on the research conducted so far, monoclonal antibodies against specific cytokines and corticosteroids are useful to counteract and prevent the cytokine storm, and they appear to improve clinical outcomes in patients with critical stage COVID-19 (Fig. 1).

2.3.4. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are drugs with antiviral activity that both also have immunomodulatory activity that could synergistically enhance the antiviral effect in vivo. As with other drugs, even in this case, the current state of emergency has meant that the aminocholine chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, widely used for malaria and rheumatic disease treatment, were also used on COVID-19 due to the anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects of both. An international multi-centre analysis, subsequently retracted (Mehra et al., 2020), investigated the use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without macrolides (azithromycin and clarithromycin, which are antibiotics with immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects) for the treatment of COVID-19. The study included data from 671 hospitals on six continents. Hospitalised patients with positive laboratory results for SARS-CoV-2 between December 20, 2019 and April 14, 2020 were included. Overall, the data covered 96,032 patients (average age of 53.8 years and 46.3% women) with COVID-19 who were hospitalised during the study period and met the inclusion criteria. The results of this large multi-centre observational analysis showed that each of the pharmacological regimens examined (chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with a macrolide) were associated with an increased risk of the (clinically significant) onset of arrhythmias ventricular and increased risk of in-hospital death. This result was associated with the cardiovascular toxicity of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, particularly because of their known relationship with electrical instability characterised by the prolongation of the QT interval (this interval expresses the time it takes for the ventricular myocardium to depolarise and repolarise). This propensity is greater in subjects with cardiovascular problems and heart injuries. As this was an observational study, the authors highlight the presence of numerous biases. However, the results indicate that these treatments should not be used outside of clinical trials and that they require “urgent” confirmation through randomised clinical trials. On June 17, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the hydroxychloroquine arm of the Solidarity trial project to find an effective COVID-19 treatment was being stopped (WHO, 2020). On April 23, 2020, AIFA had already published the communication of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) on its website. This communication drew attention to the risk of serious side effects from the use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19 patients, such as heart rhythm disturbances, which can be aggravated if treatment is combined with other medicines, and antibiotic azithromycin (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020 e). On May 29, 2020, pending obtaining more solid evidence from ongoing clinical trials in Italy and other countries, AIFA suspended the authorisation to use hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19 outside of authorised clinical trials (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020 f). AIFA supports this decision based on a critical review of the latest literary evidence (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020 g).

2.3.5. Anticoagulants

In the advanced stage of COVID-19, a progressive alteration of some inflammatory and coagulative parameters was observed, including increased levels of the fragments of degradation of fibrin such as D-dimer, consumption of coagulation factors, thrombocytopenia, etc. Therefore, in this stage, the goal should be the containment of hyperinflammation and its consequences (for example with biological drugs) and therapeutic doses of non-fractionated LMWH or heparins, which are known for their anticoagulant properties (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020 a).

Although not a specific drug for the treatment of COVID-19 patients, based on results highlighted in some scientific studies, AIFA included low-molecular-weight heparins among the drugs that can be used in the treatment of this pathology, providing useful elements to guide clinicians when prescribing (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020a). Moreover, as part of the COVID-19 emergency, the evaluation of all clinical trials on drugs has been entrusted to AIFA (Italian Care Law Decree Art. 17).

A retrospective analysis (Tang et al., 2020) of 415 consecutive cases of severe COVID-19 pneumonia patients in Wuhan hospital suggests that in patients in whom coagulation activation is demonstrated, administration of heparin for at least 7 days may result in an advantage in terms of survival. LMWH can be used in the initial stage of the disease when pneumonia is present and the patient suffers hypomobility at bedtime, as prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism, or in the more advanced stage, in hospitalised patients with thrombotic phenomena starting from the pulmonary circulation as a consequence of hyperinflammation.

To the best of our knowledge, in the context of the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19, it seems of fundamental importance to prevent the complication of venous thromboembolism through pharmacological prophylaxis (Fig. 1).

2.3.6. Therapeutic antibodies

Antibodies taken from the blood of recovered patients serve as a therapeutic alternative that is presently under study. It is estimated that the dose of antibodies critical for treating a person affected with SARS-CoV-2 requires the removal of antibodies from at least three patients who have recovered from the SARS-CoV-2 infection. The short period between the pandemic and the treatment under consideration means that few pieces of evidence are currently available on the safety and efficacy of the use of plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulins in the treatment of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infections. One of the first studies on the use of plasma in the treatment of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infections was conducted on 5 COVID-19 patients (Shen et al., 2020), which was then followed by many other studies, mostly on a small number of patients. The main results of the studies conducted so far reported clinical and survival improvement in all patients after the end of the additional intervention with plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulins. These findings need to be confirmed through some randomised clinical trials (RCTs). In this regard, the review by Valk et al. (2020) examined both studies conducted on a limited number of patients and more complex research designs such as still ongoing RCTs. Among these, the recent trial of Bennett-Guerrero et al. (U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov, 2020d) (process identification number on Trials. gov: NCT04344535) evaluates if the blood plasma transfusion containing antibodies to COVID-19 (anti-SARS-CoV-2), donated by patients recovered from the infection, is safe and can be effective in the treatment of hospitalised patients with COVID-19. This study involved 500 patients with a control group. In the United States (FDA NEWS RELEASE, 2020), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indicates 3 regulatory pathways that allow access to the plasma of convalescents for the therapy of COVID-19 to determine, through clinical studies, the efficacy and administration of the plasma: access treatment through participation in the clinical trial; extended access (which provides patients with a serious or fatal disease the opportunity to obtain trial medical treatment outside the clinical trial, in the absence of available alternative treatments); new emergency investigative drug (the clinician may request this for a single patient if they believe that treatment may be urgently needed for the serious or life-threatening conditions they are experiencing). The position paper (Accorsi et al., 2020) of the Italian Society for Transfusion Medicine and Immunohematology (SIMTI) and of the Italian Society of Hemapheresis and Cell Manipulation (SidEM) described the requirements that donors must have, the plasma collection methods, the times for administration and possible adverse events. The main focus is patients with a SARS-CoV-2 documented infection who voluntarily offer, after informed consent, to undergo apheresis procedures for the collection of specific plasma for the treatment of serious SARS-CoV-2 infections, according to all the directives in force on a national level. According to these indications, a subject with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection can donate at least 14 days after their clinical recovery (no symptoms) and after at least two NAT tests (Nucleic Acid Test, a test that identifies the possible presence of the virus) with negative results on the nasopharyngeal swab and serum/plasma, performed after 24 h, after recovery or before discharge if hospitalised. An additional negative NAT test, performed 14 days after the first, is not mandatory (and not required by most protocols in place). An adequate serum titre of specific neutralising antibodies is required (>160 with the EIA method or with other equivalent methods). These people are selected to donate hyperimmune plasma because they are COVID-19 convalescent patients. The authors of the position paper point out that a large number of people who have recovered from asymptomatic infection (or from a disease with minor clinical signs) may become a relevant source of hyperimmune plasma after demonstrating the presence of an antibody titre of >160 with the EIA method (or equivalent with other methods) with serological tests. Since they are regular blood donors, they fully comply with the selection criteria for plasma donation after an adequate interval (28 days) has passed from symptom resolution. Their recruitment could easily be performed by screening for SARS-CoV-2 (possibly followed by an antibody titration) in the donor population at the time of donation. This would also allow for an epidemiological picture outside the context of a serious clinical disease leading to hospitalisation (Accorsi et al., 2020). To evaluate the efficacy and role of plasma obtained from patients cured of COVID-19 with a unique and standardised method, the National Institute of Health and AIFA launched a randomised and controlled national multi-centre study (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, 2020h).

In our view, the plasma of convalescents for the therapy of COVID-19 represents an experimental and emergency therapy already utilised for other diseases.

3. Conclusions

Antiviral agents are useful to inhibit the clinical progression and complications of COVID-19. Future studies are needed to identify specific targets that inhibit the life cycle of SARS-COV-2 to prevent its replication and that, if used early, could avoid the characteristic complications of COVID-19. Clinical and survival improvement was found in patients treated with plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulins. Inflammation inhibitors (in particular anti-IL6, anti-IL1, inhibitors of Janus kinases) are valuable candidates for the treatment of COVID-19 in its advanced stages. The ongoing clinical trials should confirm safety and efficacy, and determine the COVID-19 stage in which these treatments have the greatest benefit in terms of disease regression.

Statements

The submitted manuscript “TREATMENT FOR COVID-19: AN OVERVIEW” by Stasi et al., submitted for possible publication in the European Journal of Pharmacology.

-

1.

Has not been published previously, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

-

2.

The submitted manuscript is approved by all Authors.

-

3.

In case of acceptance of the manuscript the copyright will be transferred to European Journal of Pharmacology.

-

4.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Accorsi P., Berti P., de Angelis V., De Silvestro G., Mascaretti L., Ostuni A. ”Position paper” sulla produzione di plasma iperimmune da utilizzare nella terapia della malattia da SARS-CoV2. 2020. http://www.emaferesi.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Convalescent-Plasma-SIMTI_SIDEM-1.pdf Available at:

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco BARICIVID-19 study: MultiCentre, randomised, Phase IIa clinical trial evaluating efficacy and tolerability of Baricitinib as add-on treatment of patients with COVID-19 compared to standard therapy. Sperimentazioni cliniche. 2020 https://www.aifa.gov.it/sperimentazioni-cliniche-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco COVID-19 - AIFA autorizza nuovo studio clinico con tocilizumab. 2020 b. https://www.aifa.gov.it/web/guest/-/covid-19-aifa-autorizza-nuovo-studio-clinico-con-tocilizumab

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco . 2020 c. Studio randomizzato multicentrico in aperto sull’efficacia della somministrazione precoce del Tocilizumab in pazienti affetti da polmonite da COVID-19.https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1123276/studio_RE_Toci_17.06.2020.pdf/c32ed144-ce26-d673-6e4d-11d5d0d84836 [Google Scholar]

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco Plasma: ISS e AIFA, studio nazionale per valutarne l'efficacia. 2020 h. https://www.aifa.gov.it/-/plasma-iss-e-aifa-studio-nazionale-per-valutarne-l-efficacia

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco Eparine a basso peso molecolare nei pazienti adulti con COVID-19. 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1123276/Eparine_Basso_Peso_Molecolare_11.04.2020.pdf/e30686fb-3f5e-32c9-7c5c-951cc40872f7

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco COVID-19 - comunicazione EMA su clorochina e idrossiclorochina. 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/-/covid-19-comunicazione-ema-su-clorochina-e-idrossiclorochina

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco AIFA sospende l’autorizzazione all’utilizzo di idrossiclorochina per il trattamento del COVID-19 al di fuori degli studi clinici. 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/web/guest/-/aifa-sospende-l-autorizzazione-all-utilizzo-di-idrossiclorochina-per-il-trattamento-del-covid-19-al-di-fuori-degli-studi-clinici

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco Idrossiclorochina nella terapia dei pazienti adulti con COVID-19. 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1123276/idrossiclorochina_29.05.2020.pdf/3958aea0-5a5f-2d05-b1f6-034dbe28ce2a

- Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., Mehta A.K., Zingman B.S., Kalil A.C., Hohmann E., Chu H.Y., Luetkemeyer A., Kline S., Lopez de Castilla D., Finberg R.W., Dierberg K., Tapson V., Hsieh L., Patterson T.F., Paredes R., Sweeney D.A., Short W.R., Touloumi G., Lye D.C., Ohmagari N., Oh M.D., Ruiz-Palacios G.M., Benfield T., Fätkenheuer G., Kortepeter M.G., Atmar R.L., Creech C.B., Lundgren J., Babiker A.G., Pett S., Neaton J.D., Burgess T.H., Bonnett T., Green M., Makowski M., Osinusi A., Nayak S., Lane H.C., ACTT-1 Study Group Members Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantini F., Niccoli L., Nannini C., Matarrese D., Natale M.E.D., Lotti P., Aquilini D., Landini G., Cimolato B., Pietro M.A.D., Trezzi M., Stobbione P., Frausini G., Navarra A., Nicastri E., Sotgiu G., Goletti D.J. Beneficial impact of Baricitinib in COVID-19 moderate pneumonia; multicentre study. J. Infect. 2020;S0163–4453(20) doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.052. 30433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G., Ruan L., Song B., Cai Y., Wei M., Li X., Xia J., Chen N., Xiang J., Yu T., Bai T., Xie X., Zhang L., Li C., Yuan Y., Chen H., Li H., Huang H., Tu S., Gong F., Liu Y., Wei Y., Dong C., Zhou F., Gu X., Xu J., Liu Z., Zhang Y., Li H., Shang L., Wang K., Li K., Zhou X., Dong X., Qu Z., Lu S., Hu X., Ruan S., Luo S., Wu J., Peng L., Cheng F., Pan L., Zou J., Jia C., Wang J., Liu X., Wang S., Wu X., Ge Q., He J., Zhan H., Qiu F., Guo L., Huang C., Jaki T., Hayden F.G., Horby P.W., Zhang D., Wang C. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W., Zhang B., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., Xie X., Jin Z., Peng J., Liu F., Li C., Li Y., Bai F., Wang H., Cheng X., Cen X., Hu S., Yang X., Wang J., Liu X., Xiao G., Jiang H., Rao Z., Zhang L.K., Xu Y., Yang H., Liu H. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Documents - AIFA Adaptive Randomized trial for therapy of Corona virus disease 2019 at home with oral antivirals (ARCO-Home study) 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1131319/covid-19_sperimentazioni_in_corso_09.05.2020.pdf/9d46f533-7406-8f7c-5e34-c119f7087d65 Accessed 7 May.

- Executive summary – Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/1127901/executive_summary_Toci_Nazionale.pdf

- FDA News Release Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA coordinates national effort to develop blood-related therapies for COVID-19. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-coordinates-national-effort-develop-blood-related-therapies-covid-19

- Fredi M., Cavazzana I., Moschetti L., Andreoli L., Franceschini F., on behalf of the Brescia Rheumatology COVID-19 Study Group COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases in northern Italy: a single-centre observational and case–control study. 2020. https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S2665-9913%2820%2930169-7 18 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goldman J.D., Lye D.C.B., Hui D.S., Marks K.M., Bruno R., Montejano R., Spinner C.D., Galli M., Ahn M.Y., Nahass R.G., Chen Y.S., SenGupta D., Hyland R.H., Osinusi A.O., Cao H., Blair C., Wei X., Gaggar A., Brainard D.M., Towner W.J., Muñoz J., Mullane K.M., Marty F.M., Tashima K.T., Diaz G., Subramanian A., GS-US-540-5773 Investigators Remdesivir for 5 or 10 Days in patients with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015301. 2020, 10.1056/NEJMoa2015301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grein J., Ohmagari N., Shin D., Diaz G., Asperges E., Castagna A., Feldt T., Green G., Green M.L., Lescure F.X., Nicastri E., Oda R., Yo K., Quiros-Roldan E., Studemeister A., Redinski J., Ahmed S., Bernett J., Chelliah D., Chen D., Chihara S., Cohen S.H., Cunningham J., D'Arminio Monforte A., Ismail S., Kato H., Lapadula G., L'Her E., Maeno T., Majumder S., Massari M., Mora-Rillo M., Mutoh Y., Nguyen D., Verweij E., Zoufaly A., Osinusi A.O., DeZure A., Zhao Y., Zhong L., Chokkalingam A., Elboudwarej E., Telep L., Timbs L., Henne I., Sellers S., Cao H., Tan S.K., Winterbourne L., Desai P., Mera R., Gaggar A., Myers R.P., Brainard D.M., Childs R., Flanigan T. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaraldi G., Meschiari M., Cozzi-Lepri A., Milic J., Tonelli R., Menozzi M., Franceschini E., Cuomo G., Orlando G., Borghi V., Santoro A., Di Gaetano M., Puzzolante C., Carli F., Bedini A., Corradi L., Fantini R., Castaniere I., Tabbì L., Girardis M., Tedeschi S., Giannella M., Bartoletti M., Pascale R., Dolci G., Brugioni L., Pietrangelo A., Cossarizza A., Pea F., Clini E., Salvarani C., Massari M., Viale P.L., Mussini C. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e474–e484. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gul M.H., Htun Z.M., Shaukat N., Imran M., Khan A. Potential specific therapies in COVID-19. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2020;14 doi: 10.1177/1753466620926853. 1753466620926853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R., Mafham M., Bell J.L., Linsell L., Staplin N., Brightling C., Ustianowski A., Elmahi E., Prudon B., Green C., Felton T., Chadwick D., Rege K., Fegan C., Chappell L.C., Faust S.N., Jaki T., Jeffery K., Montgomery A., Rowan K., Juszczak E., Baillie J.K., Haynes R., Landray M.J. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 17 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. NEJMoa2021436, Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32678530; PMCID: PMC7383595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidori A.M., Arnaldi G., Boscaro M., Falorni A., Giordano C., Giordano R., Pivonello R., Pofi R., Hasenmajer V., Venneri M.A., Sbardella E., Simeoli C., Scaroni C., Lenzi A. COVID-19 infection and glucocorticoids: update from the Italian Society of Endocrinology Expert Opinion on steroid replacement in adrenal insufficiency. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2020;43:1141–1147. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01266-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A., Vail A., O'Leary C., Hannan C., Brough D., Patel H., Galea J., Ogungberno K., Wright M., Pathmanaban O., Hulme S., Allan S. Anakinra in COVID-19: important considerations for clinical trials. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e379–381. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Q.X., Li Y., Peng J., Huang Y., Xu D. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matricardi P., Dal Negro R., Nisini R. The first, holistic immunological model of COVID‐19: implications for prevention, diagnosis, and public health measures. Paediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2020 doi: 10.1111/pai.13271. 10.1111/pai.13271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra M.R., Desai S.S., Ruschitzka F., Patel A.N. RETRACTED: hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without a macrolide for treatment of COVID-19: a multinational registry analysis. Lancet. 2020;S0140–6736(20):31180–31186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31180-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J., on behalf of the HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randomised evaluation of COVID-19 therapy. 2020. https://www.recoverytrial.net/ Available at:

- Richardson P., Griffin I., Tucker C., Smith D., Oechsle O., Phelan A., Rawling M., Savory E., Stebbing J. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020;395:e30–e31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C., Wang Z., Zhao F., Yang Y., Li J., Yuan J., Wang F., Li D., Yang M., Xing L., Wei J., Xiao H., Yang Y., Qu J., Qing L., Chen L., Xu Z., Peng L., Li Y., Zheng H., Chen F., Huang K., Jiang Y., Liu D., Zhang Z., Liu Y., Liu L. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323:1582–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2020;18:1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov FLARE: favipiravir +/- lopinavir: a RCT of early antivirals (FLARE) 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04499677

- U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov Trial of Early Therapies During Non-hospitalized Outpatient Window for COVID-19 (TREATNOW) 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04372628?term=antiviral+agents%2C+early+phase&cond=Covid19&draw=6

- U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov Efficacy and safety of emapalumab and anakinra in reducing hyperinflammation and respiratory distress in patients with COVID-19 infection. 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT043240

- U. S. National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrial.gov Convalescent plasma vs. Standard plasma for COVID-19. 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04344535?cond=NCT04344535&draw=2&rank=1

- Valk S.J., Piechotta V., Chai K.L., Doree C., Monsef I., Wood E.M., Lamikanra A., Kimber C., McQuilten Z., So-Osman C., Estcourt L.J., Skoetz N. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID‐19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020;5:CD013600. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Solidarity clinical trial for COVID-19 treatments. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/solidarity-clinical-trial-for-covid-19-treatments

- World Health Organization WHO updates clinical care guidance with corticosteroid recommendations. 2020 b. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-updates-clinical-care-guidance-with-corticosteroid-recommendations