Abstract

Intracellular signaling is a critical determinant of the normal growth and development of plants. Signaling peptides, also known as peptide hormones, along with classical phytohormones, are the significant players of plant intracellular signaling. C-terminally encoded peptide (CEP), a 15-amino acid post-translationally peptide identified in Arabidopsis, plays a pivotal role in lateral root formation, nodulation, and act as long-distance root to shoot signaling molecule in N-starvation conditions. Expression of CEP gene members in Arabidopsis is perturbed by nitrogen starvation; however, not much is known regarding their role in other abiotic stress conditions. To gain a comprehensive insight into CEP biology, we identified CEP genes across diverse plant genera (Glycine max, Sorghum bicolor, Brassica rapa, Zea mays, and Oryza sativa) using bioinformatics tools. In silico promoter analysis revealed that CEP gene promoters show an abundance of abiotic stress-responsive elements suggesting a possible role of CEPs in abiotic stress signaling. Spatial and temporal expression patterns of CEP via RNA seq and microarray revealed that various CEP genes are transcriptionally regulated in response to abiotic stresses. Validation of rice CEP genes expression by qRT-PCR showed that OsCEP1, OsCEP8, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10 were highly upregulated in response to different abiotic stress conditions. Our findings suggest these CEP genes might be important mediators of the abiotic stress response and warrant further overexpression/knockout studies to delineate their precise role in abiotic stress response.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12298-020-00881-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Abiotic stress, C-terminally encoded peptide (CEP), qRT-PCR, Signaling peptides

Background

Intracellular communication and coordination among different tissues and cells is an essential determinant for the growth and development of multicellular organisms. In animals, cell to cell communication primarily involves signaling peptides like insulin, secretin, etc. However, until the discovery of systemin (first peptide ligand) in 1991, phytohormones, viz., auxin, gibberellin, cytokinin ethylene, and abscisic acid were known to be the key players in intercellular communication in plants (Pearce et al. 1991; Kende 1997). During the last two decades, several signaling peptides have been identified in plants with the help of bioinformatics tools (Matsubayashi 2018; Grienenberger and Fletcher 2015). These signaling peptides may be involved in short distance or long-distance root to shoot signaling mechanisms under different environmental conditions.

In plants, signaling peptides are classified into two groups based on their structural similarity (Murphy et al. 2012). The first group includes small post-translationally modified peptides (5–20 AA), and the second group comprises cysteine-rich polypeptides (< 160 AA), which form disulfide linkages upon maturation (Grienenberger and Fletcher 2015). More than 1000 putative small signaling polypeptides have been discovered in Arabidopsis (Lease and Walker 2006), and many of these peptides have been found to play a role in developmental responses due to altering environmental conditions (Taleski et al. 2016). One such signaling peptide involved in root to shoot long-distance signaling under nitrogen starvation conditions is C-terminally Encoded Peptide (CEP) (Tanaka and Ogawa-ohnishi 2017).

The CEP polypeptide before post-translational modification contains an N-terminal secretion signal (NSS), a variable domain, one or more CEP domain, and a short C-terminal extension (Ogilvie et al. 2014). The post-translational modification of peptides is essential for their biological activity (Ohyama et al. 2008; Matsuzaki et al. 2010; Matsubayashi 2011; Whitford et al. 2012). The mature CEP peptide contains one or two proline residues that are chemically modified into hydroxyproline or arabinosylated hydroxyproline (Delay et al. 2013a, b; Patel et al. 2018). NMR studies have shown that these hydroxyl proline residues influence the protein flexibility and its ability to interact with the receptors (Kondo et al. 2011; Bobay et al. 2013; Shinohara and Matsubayashi 2010; Mohd-radzman et al. 2015). Patel et al. (2018) suggested that after cleavage of a signal sequence, the CEP prepropeptide undergoes endoproteolytic cleavage by aminopeptidases and carboxypeptidases.

CEP(s) function in root growth and development (Ohyama et al. 2014; Delay et al. 2018, 2013a, b; Roberts et al. 2013a, b). In Medicago, MtCEP1 affects lateral root growth and nodule formation when expressed in primary root tips, vascular tissues, and lateral organ primordia. Overexpression of exogenous addition of synthetic MtCEP1 peptide results in the inhibition of lateral root formation and enhancement in nodule formation (Imin et al. 2013; Mohd-radzman et al. 2015). It was due to the interaction of MtCEP1 with the CRA2 receptor (Mohd-Radzman et al. 2016). Cra2 knockout plants show a highly branched root phenotype indicating that CRA2 interacts with MtCEP1 (Huault et al. 2014). AtCEP5 expressed in phloem pole pericycle showed a similar phenotype to MtCEP1 when overexpressed (Roberts et al. 2016). AtCEP3 mutant showed enhanced primary and lateral root growth when grown under various abiotic stress conditions (Delay et al. 2013a, b). Besides the role in root architecture, CEP genes also play a role in nitrate assimilation under N- starvation conditions (Tabata et al. 2014). CEP(s) act as long-distance root to shoot signaling molecules produced under the N-starvation condition and results in the upregulation of NRT2.1 (Tanaka and Ogawa-ohnishi 2017; Tabata et al. 2014; Ohkubo et al. 2017). CEP interaction with CEPR, also known as XIP1 (Bryan et al. 2012), results in the expression of CEPD1 and CEPD2 in shoots, which act as root ward signals necessary for upregulation of NRT2.1 (Tabata et al. 2014). These studies indicate that CEP peptide might have a role in the abiotic stress signaling mechanism, which needs to be investigated.

To have a clear understanding of diverse aspects of CEP functions, it is necessary to explore the role of CEP in different plants, especially in agronomically important crops. We have identified CEP genes in various plant genera viz Glycine max, Sorghum bicolor, Brassica rapa, Zea mays, and Oryza sativa. The RNA seq and microarray data were analyzed to obtain a snapshot of expression patterns of CEP genes in various abiotic stress conditions and different developmental stages. The qRT-PCR analysis was done to identify the temporal and spatial expression patterns of CEP genes in rice seedlings in response to abiotic stress conditions.

Materials and methods

Identification and nomenclature of CEP family members

Putative CEP genes were identified using characterized AtCEP protein sequence obtained from NCBI. The protein sequence of known CEP members was searched in the UniprotKB database (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/), which were then aligned using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo) and retained in Stockholm output format for identification of CEP genes in Glycine max, Sorghum bicolor, Brassica rapa, Zea mays, and Oryza sativa. Using EMBOSS CONS (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi- bin/emboss/cons), the consensus sequence of the proteins was obtained, and the entire proteome sequence of Glycine max (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-33/fasta/glycine_max/pep/), Zea mays (http://www.plantgdb.org/XGDB/phplib/download.php?GDB=Zm), Brassica rapa (https://plants.ensembl.org/Brassica_napus/Info/Annotation/#assembly) and Sorghum bicolor (ftp://ftpmips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/plants/sorghum/genes/) was downloaded from the respective databases. Further, from these downloaded proteome sequences, a BLAST compatible protein database was created on our local computer and masked to remove simple internal repeats using SAGE. Standalone BLAST+ (Camacho et al. 2009) and HMMER 3.1b2 (http://hmmer.org/) were used in the Linux platform on the local machine for searching putative CEP genes in Oryza sativa, Glycine max, Zea mays, Brassica rapa and Sorghum bicolor. The aligned sequences of previously known CEP genes obtained from UniProtKB (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/) in Stockholm format were used as a query for Psi-BLAST against the masked proteome databases, separately for each species. An e-value cutoff of ± 1e−10 was taken as a search threshold, and further redundant entries were removed. JACKHMMER and Hidden Markov Model were used to refine the results further (Batth et al. 2017). Orthologous genes between Arabidopsis thaliana, Brassica rapa, and Zea mays, Sorghum bicolor were identified using proteinortho (Lechner et al. 2011). We filtered the best ortholog pairs, wherever there were multiple relationships between orthologs, based on the lowest e-value and highest bitscore among the ortholog clusters.

Chromosomal localization of CEP genes

Chromosomal coordinates of the CEP gene were retrieved from Ensembl plants biomart. Gene loci were used to create a chromosome map of each species using Mapchart. Gene locations are shown in Mega basepairs (Mbp).

Identification of Cis-acting regulatory elements (CAREs) in CEP genes

Upstream region (~ 1500 bp) of CEP genes was retrieved from Ensembl plants biomart and used to identify CAREs using the PlantCARE database as well as the PLACE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/https://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/?action=newplace). CAREs identified in all plants were pooled together and redundant were removed. The remaining CAREs were divided into six broad categories based on their function. All the CEP genes were plotted with the identified CARE elements in the form of a binary (presence/absence) heatmap. Transcription factor enrichment was done using PlantRegMap (http://plantregmap.cbi.pku.edu.cn/tf_enrichment.php). A p-value cutoff of 0.05 was used to get significantly enriched transcription factors.

Expression profiling of CEP genes using publicly available data

Publicly available RNA seq data and microarray data at EBI expression atlas (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gxa/home) and Genevestigator (https://genevestigator.com/gv/start/start.jsp) respectively, were used to analyze the expression levels of CEP genes under different abiotic stress conditions (cold, salinity, drought, etc.) and different developmental stages. A summary of the RNA-seq datasets employed for expression analysis of CEP genes is given in Supplementary Table 1. RNA-Seq datasets available at EBI expression atlas were queried using the Bioconductor package ExpressionAtlas (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ExpressionAtlas.html). Gene level counts obtained from ExpressionAtlas were analyzed for differential expression using Wald’s test in the DESeq 2 package (Love et al. 2014). The resulting p-values from Wald’s test were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) (Supplementary sheet 2). In the case of tissue-specific and developmental stage-related experiments, TPM/FPKM values were centered and scaled using unit variance scaling before plotting the heatmap. In the case of stress conditions, log2FC estimated by DESeq 2 is plotted as a heatmap.

Plant material and qRT-PCR analysis

IR64 seeds were grown hydroponically in a growth chamber at 28 ± 2 °C under a photoperiod of 16 h and a dark period of 8 h at 70% humidity. The seeds were first treated with Bavistin, an antifungal agent, and allowed to germinate in water. After germination, seeds were grown in Yoshida media for 10 days following which different stress treatments were given. Salinity stress was applied by growing the plants in Yoshida media supplemented with 200 mM of NaCl, and for drought stress, seedlings were removed from the media and dried on tissue paper for 1 h and 24 h. Seedlings grown in Yoshida media without any stress were used as control. Total RNA was isolated from both root and shoot tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). 250 µg of total RNA was used to isolate mRNA by streptavidin magnetic beads and biotinylated Oligo (dT) primer. First-strand cDNA was prepared from 500 ng of mRNA using Maxima first-strand cDNA synthesis kit for qRT-PCR (Thermo Fisher). The primers for real-time analysis were designed using the NCBI blast and are listed in Supplementary Table 7. qRT-PCR analysis was done using the eIF4α gene as a reference gene for normalizing the data. A PCR reaction was set using 2.5 µl of 10X diluted first-strand cDNA, 5 µl of 2X SYBR Green PCR mix and 1 µl of 10 µM of each gene-specific primer in a total volume of 10 µl. Following conditions were set for PCR in ViiA7™ real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, USA): 10 min at 95 °C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C and melt curve with single reaction cycle with following conditions, 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min and dissociation at 95 °C for 15 s. Three biological replicates were used for each sample, and the relative expression ratio was calculated using the delta–delta Ct value method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Results

CEP genes identification in different crop plants

Using bioinformatics tools and previously reported AtCEP protein sequence as a query sequence, we identified CEP genes across various plant genera such as Oryza sativa, Sorghum bicolor, Zea mays, Brassica rapa, and Glycine max. The presence of CEP domains confirmed the identity of protein as the CEP protein. Five putative CEP genes were identified in Sorghum bicolor, twenty-seven in Glycine max, ten in Zea mays, twenty-four in Brassica rapa, and fifteen in Oryza sativa. CEP genes have been identified in Oryza sativa in previous studies (Delay et al. 2013a, b; Roberts et al. 2013a, b; Sui et al. 2016; Ogilvie et al. 2014). However, we found that OsCEP7 and OsCEP8, OsCEP2, and OsCEP4 share a common protein sequence as well as gene id (LOC_Os01g10640 and LOC_Os03g27690, respectively) (Sui et al. 2016). In our study, in an attempt to compare the previously published results from O. sativa, we identified fifteen CEP genes, of which thirteen were the same as formerly known CEP genes. Two novel CEP genes were retrieved in our study, namely OsCEP2 and OsCEP15. Further, since CEP genes from different plant species were identified, a standard way of nomenclature of genes was adopted to avoid any ambiguity. All the identified CEP genes from Glycine max, Sorghum bicolor, Brassica rapa, Zea mays, and Oryza sativa were named based on order and chromosomal location according to nomenclature employed in several previous studies on plant gene families (Ghosh 2017; Li et al. 2019).

The detailed CEP gene sequence features are listed in Supplementary Table 2-6. None of the identified CEP genes have alternative splice form. We identified a total of 81 CEP genes in five different crop plants. The largest CEP gene/protein identified was SbCEP4 with a gene length of 5891 bp, and the smallest CEP was SbCEP2 with a gene length of only 141 bp. There was no correlation between the genome size/ploidy level and the number of CEP genes in the crops (Table 1). Since the CEP gene is a short signaling peptide molecule, it was difficult to find orthologous CEP genes in distant relatives. However, by using proteinortho, we identified CEP orthologues between Brassica rapa and Arabidopsis; Sorghum bicolor and Zea mays. Eight orthologous gene pairs were identified in B. rapa and Arabidopsis, three each in Sorghum bicolor and Zea mays. Since the RNA seq and microarray data from Sorghum bicolor, Zea mays, and Brassica rapa were from different developmental stages and stress conditions, we were not able to compare expression patterns of all the orthologous gene pairs. The available data did not comprise all identified CEP genes, which further added to the difficulty. However, SbCEP2 and ZmCEP9; AtCEP15 and BrCEP4 were found to be expressed highly in roots while AtCEP13 and BrCEP13 were predominant in flowers in respective species (Fig. 4b–d).

Table 1.

Table showing the correlation between the number of CEP genes identified in different crop plants and genome size/ploidy level

| Crop name | No. of CEP genes identified | Genome size | Ploidy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oryza sativa | 15 | 500 Mb | 2n |

| Zea mays | 10 | 2.4 Gb | 2n |

| Brassica rapa | 24 | 849.7 Mb | 2n |

| Sorghum bicolor | 5 | 730 Mb | 2n |

| Glycine max | 27 | 1.15 Gb | Partially diploidized tetraploid |

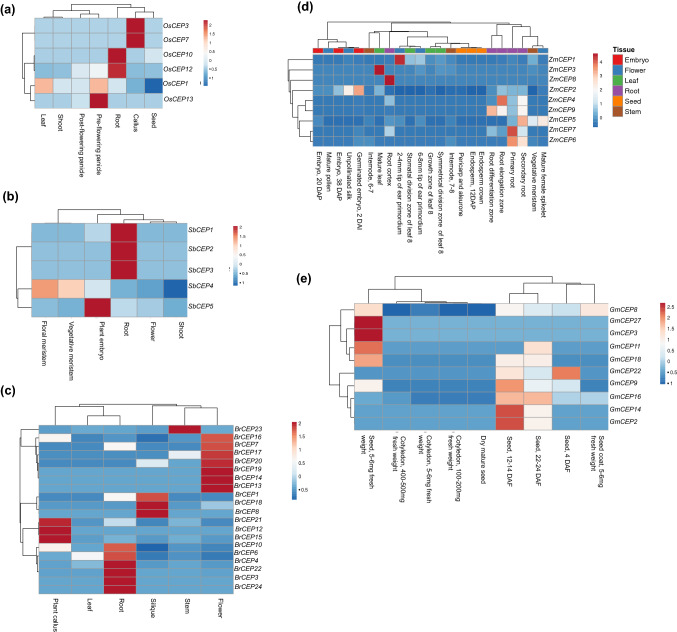

Fig. 4.

Heatmap depicting expression level of CEP genes at different developmental stages across various plant genera. The expression of CEP genes at different stages of development in a rice, b Sorghum bicolor, c Brassica rapa, d Zea mays, and e Glycine max. FPKM values were scaled and centered before creating the heatmap

Chromosomal distribution and gene duplication

CEP genes did not show any particular pattern in terms of their distribution on the chromosomes. All the crops had CEP genes distributed randomly on different chromosomes (Fig. 1). Gene density was also not confined to a particular arm of the chromosome, and they were distributed randomly on both arms. These gene pairs are highlighted in red in Fig. 1. We found one tandemly duplicated array of four CEP genes in rice, namely OsCEP7, OsCEP8, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10. Gene pairs that share more than 40% amino acid similarity and are intervened by less than five genes are considered as tandemly duplicated gene pairs (Kapoor et al. 2008).

Fig. 1.

Chromosomal localization of the CEP gene in different plant genera. Chromosomal distribution of CEP genes in a rice, b Sorghum bicolor, c Glycine max, d Brassica rapa, e Zea mays. The chromosomal position, along with the CEP gene name, is marked on the chromosome. The only chromosome with CEP genes is shown. Tandemly duplicated gene pairs are highlighted in red (color figure online)

CEP gene promoters show an abundance of multiple stress-responsive CAREs

Cis-acting elements in their promoter region mainly regulate spatial, temporal, and cell-specific expression of genes. Therefore, a comparative analysis of the CEP promoter was carried out in various plant species using the PLACE database, which revealed the presence of several elements related to stress, phytohormone response, cell cycle, and light response (Fig. 2). Among various cis-acting regulating elements, stress-responsive elements are most abundant in all CEP genes across all the plant species under study. The promoter region of CEP gens of each plant species have MYB binding sites, W-box [TGAC], an element known for the binding site of WRKY transcription factor-induced in salinity, wounding and cold conditions, CCAAT box (heat shock responsive elements), GTI (salt responsive element), GTAC (copper responsive element), SURE (sulfur responsive elements), MYC recognition site and ACGT (drought-responsive elements). These elements were present as multiple copies within the same CEP gene, indicating a role of CEPs in abiotic stress response. BrCEP16, a 106 AA protein contained 16 binding sites for copper responsive element 16 times while OsCEP1 and OsCEP13 contained 22 and 20 s GTAC sites.

Fig. 2.

Heatmap representing the presence or absence of cis-acting regulatory elements (CAREs) in all the identified CEP genes. The CAREs are divided into broad categories based on their function. These categories are depicted on top of the heatmap

Similarly, several MYC and MYB binding sites were present as multiple copies in CEP genes. MYCCONSENSUSAT, an MYC recognition site, found in the promoters of the dehydration-responsive gene RD22 and many other genes (Chinnusamy et al. 2004) was present 25, 22 and 20 times in OsCEP13, OsCEP10, and OsCEP8 respectively. CEP genes contain various ABA response elements such as ABRE, ABRE2, ABRE3a, and ABRE4 in their upstream region, thus suggesting that ABA regulates CEP genes. A detailed list of different stress-responsive motif present in CEP genes is listed in supplementary sheet 1. bHLH, WRKY, bZIP, MADS, and G2-like were found to be the probable transcription factors, that might bind to the upstream regions of various CEP genes (Fig. 3). All of these transcription factors are known to be involved in abiotic stress response and are influenced by phytohormones such as auxin, ABA, and gibberellins (Hatorangan et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2012; Zou et al. 2008; Castelán-muñoz et al. 2019). However, experimental validation through CHIP-seq analysis will be needed to establish the mechanistic details of these in silico study based observations.

Fig. 3.

Plot showing an abundance of probable transcription factors that might bind to the promoter of CEP genes. Word plot showing an abundance of transcription factors that might bind in the upstream region of CEP genes across different genera. Transcription factor enrichment was done using PlantRegMap. Word size is directly proportional to the number of times any transcription factor was reported as enriched with a p-value cutoff of 0.05

Expression of CEP genes in different developmental stages

The presence of CAREs involved in various developmental processes indicates a role of CEPs in the growth and development of plants. We investigated the expression pattern of CEPs across different developmental stages in crop plants (Fig. 4). In rice (Fig. 4a), most of the CEP genes showed low expression at various developmental stages except for a few such as OsCEP10, and OsCEP12 had a higher expression in roots. In comparison, OsCEP3 and OsCEP7 had a higher expression in callus, while OsCEP13 was predominant in the pre-flowering stage.

In Sorghum bicolor (Fig. 4b), SbCEP1, SbCEP2, and SbCEP3 were highly expressed in roots while SbCEP5 had higher expression in the embryo stage. Except for SbCEP4, the expression of other SbCEP genes was negligible in flower, shoot, and vegetative and floral meristem.

In Brassica rapa (Fig. 4c), CEP genes show changes in expression at different developmental stages. BrCEP3, BrCEP4, BrCEP6, BrCEP10, BrCEP22, and BrCEP24 have higher expression in roots than the rest of CEP genes, and BrCEP23 is abundant in the stem. In leaf tissue, CEP genes were expressed at a lower level. BrCEP13, BrCEP14, BrCEP16, BrCEP17, BrCEP19, BrCEP20, and BrCEP7 were abundantly expressed in flower while BrCEP1, BrCEP8, and BrCEP18 were expressed at a higher level in silique.

In Zea mays (Fig. 4d), CEP genes had low expression in stem, leaf, flower, embryo, and seed except for ZmCEP1 in flower and ZmCEP3 in mature leaf. ZmCEP4, ZmCEP5, ZmCEP6, ZmCEP7, ZmCEP8, and ZmCEP9 showed higher expression in different parts of roots.

In Glycine max (Fig. 4e), RNA seq data was available for seed tissues from fertilization to mature seeds formation. GmCEP8 expression is low in cotyledons, whereas GmCEP27 and GmCEP3 expression is highest in the seed.

Expression of CEP genes under different abiotic stress conditions

CEP(s) have been reported to be expressed under various stress conditions in Arabidopsis, Apple, and Medicago (Li et al. 2018; Mohd-radzman et al. 2015; Taleski et al. 2018). The presence of various CAREs involved in stress response (Fig. 2) indicated the role of CEP in stress conditions. Thus, microarray and RNA seq data was analyzed to check the expression profile of CEP genes in different abiotic stress conditions (Fig. 5). The CEP genes were found to be significantly differentially regulated in response to different abiotic stress conditions in various plant species (Supplementary sheet 2).

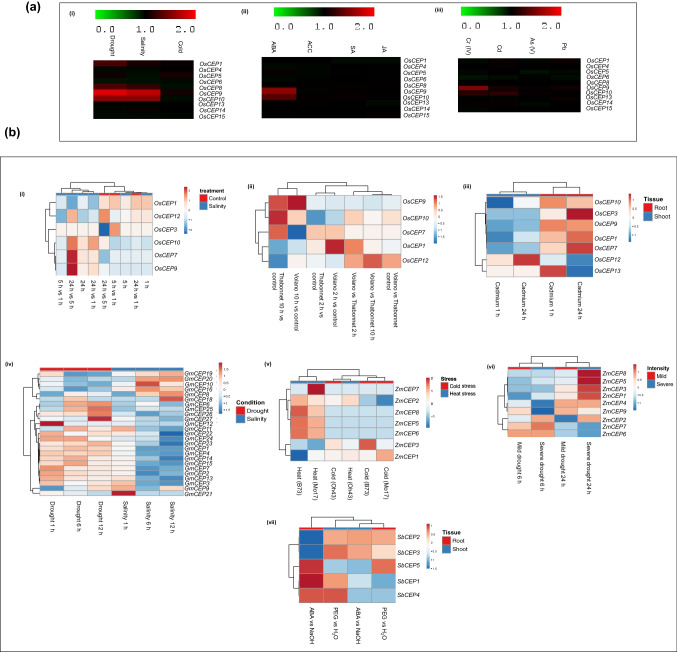

Fig. 5.

Expression level of CEP genes under different abiotic stress conditions based on publicly available a microarray and b RNA seq data. Heatmap analysis of expression of CEP genes a(i) in 7-day old IR64 seedlings under different abiotic stress conditions such as salinity, drought, and cold stress. a(ii) in 7-day old IR64 seedlings incubated for 3 h in different hormone solutions such as abscisic acid (AbA), salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA) and 1-aminocyclopropane-1carboxyclic acid (ACC). a(iii) in 10-day old IR64 seedlings grown in Hewit solution and treated with 100 µm of chromium (Cr), Cadmium (Cd), Arsenic (As), and Lead (Pb). The green color represents down-regulation of the gene; black color represents no change in expression level, while red color represents up-regulation with respect to control samples. Heatmap representing log2 fold change of various CEP genes in different plants in different abiotic stress conditions based on RNA seq data b(i) from Nipponbare in salinity stress b(ii) cold stress and b(iii) cadmium stress. b(iv) Heatmap showing expression of CEP genes in Glycine max under salinity and drought stress at different time points. b(v) Heatmap representing the expression of CEP genes in response to cold and heat stress in different Zea mays varieties (Mo17, Oh43, B70). b(vi) Heatmap representing the expression of CEP genes in Zea mays varieties (Mo17, Oh43, B70) under drought stress. b(vii) Heatmap representing the expression of CEP genes from Sorghum bicolor shoot and root tissues under ABA and PEG

Microarray data was available for an indica variety, IR64, and it was observed that OsCEP9 & OsCEP10 were highly upregulated in drought and salt stress. OsCEP1 and OsCEP8 showed higher expression in drought conditions as compared to salinity stress [Fig. 5a (i)]. Abscisic acid (ABA) is a stress-responsive hormone in plants. In the presence of ABA, OsCEP9 and OsCEP10 expression were upregulated, whereas, upon the external application of other hormones such as ACC, salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA), OsCEP expression remained unchanged [Fig. 5a (ii)]. Microarray data depicts that OsCEP9 expression was also upregulated in response to heavy metals like chromium and cadmium. OsCEP10 was also slightly upregulated in response to heavy metal stress [Fig. 5a (iii)].

RNA seq data of Nipponbare rice variety reveals that OsCEP7, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10 were highly upregulated in salt stress [Fig. 5b (i)]. Additionally, their expression also increased in cold-sensitive rice variety Thaibonnet, while in Volano (cold-tolerant), only OsCEP9 expression was high when compared with control at 10 h of stress. OsCEP1 showed a higher expression in Volano at 2 h of cold stress, while OsCEP7 expression was downregulated at 10 h of stress treatment [Fig. 5b (ii)]. In the case of cadmium stress, OsCEP13 had higher expression at 1 h while the rest of OsCEPs showed higher expression at 24 h in roots except for OsCEP13 and OsCEP12, whose expression decreased with prolonged exposure to cadmium. On the other hand, in shoot, most of the CEP genes showed downregulation in both early and late time points [Fig. 5b (iii)].

In Glycine max, CEP genes showed a distinctive expression pattern in drought and salinity stress [Fig. 5b (iv)]. At 1 h of salt stress, mostly GmCEP genes expression was low or close to zero except for GmCEP21, whose expression decreased with an increase in the duration of salt stress. Similarly, most GmCEP genes expression was downregulated as salt stress continued except for a few, namely GmCEP8, GmCEP10, GmCEP16, GmCEP18, GmCEP19, and GmCEP20. On the contrary, in drought conditions, only a few CEP genes are involved, mainly GmCEP27 and GmCEP12, whose expression was upregulated at 12 h and 1 h of stress, respectively.

In Zea mays, CEP genes show changes in expression in different abiotic stress conditions [Fig. 5b (v, vi)]. ZmCEP1, ZmCEP3, ZmCEP5, and ZmCEP8 were highly upregulated in severe drought conditions at 24 h while ZmCEP4 and ZmCEP9 were highly downregulated at 6 h of severe drought condition in primary roots. In B73, Mo17, and Oh43, CEP expression was slightly altered in cold stress while in heat stress, ZmCEP7 showed the highest expression in Mo17, and ZmCEP1 showed the lowest expression in B73.

In Sorghum, all of the CEP showed altered expression upon the application of abscisic acid (ABA) and PEG in both root and shoot tissues. Upon treatment with ABA, the expression of CEP genes was most altered in root tissues. SbCEP1 and SbCEP5 were highly upregulated, while SbCEP2 and SbCEP3 were downregulated [Fig. 5b (vii)].

qRT-PCR reveals CEP genes to be differentially expressed in root and shoot

The qRT-PCR reaction was set for only those genes which could be amplified from cDNA in reverse transcriptase PCR (OsCEP1, OsCEP5, OsCEP8, OsCEP9, OsCEP10, and OsCEP13). OsCEP8 and OsCEP9 were highly upregulated in shoots (Fig. 6a) at the early time point of abiotic stress conditions, whereas expression of both the genes decreased with increasing duration of stress. OsCEP1, OsCEP5, and OsCEP13 were downregulated in response to stress. After 1 h of salinity stress (200 mM NaCl), OsCEP8 was 66-folds upregulated while OsCEP9 was one hundred 22-folds upregulated compared to the control conditions. Expression of both OsCEP8 and OsCEP9 decreased significantly after 24 h of stress treatment as compared to 1 h after salinity stress. Similarly, in case of drought stress, initially (1 h), the expression of OsCEP8 and OsCEP9 was remarkably high (24-fold and 68-folds, respectively). With increase in time of stress treatment, the level of OsCEP8 and OsCEP9 went down. OsCEP1 and OsCEP5 were downregulated at different abiotic stress conditions in shoot samples. OsCEP1 expression was initially two-fold downregulated in drought stress, which almost doubled with a four-fold decrease at 24 h time point.

Fig. 6. Expression profile of CEP genes in response to different abiotic stress conditions.

The expression level of CEP genes in rice variety IR64 in response to various abiotic stress conditions [drought and salinity (200 mM)] for 1 h and 24 h duration in a shoots and b roots were obtained by qRT-PCR. The expression level of CEP genes in control samples without any stress was set as 1, and the fold change values were plotted in the form of a bar graph. All qRT-PCR experiments were done with three biological replicates and three technical replicates. The standard deviation of three biological replicates has been shown by error bars

Similarly, OsCEP1 expression decreased up to five-fold in salinity stress. OsCEP5 expression level slightly increased during the early stage of salinity stress but later on decreased by nine-fold, whereas in drought stress, its level went down by six-folds at a later stage. OsCEP10 expression was quite contrasting in case of drought stress. Initially, its expression was downregulated three-folds, while later on, its expression surged up to nine-folds. OsCEP13 is a late responsive gene whose expression changed by ten-folds and seven-folds at later stages of salinity and drought stress, respectively.

In roots (Fig. 6b), out of fifteen OsCEP genes, only five were expressed in different abiotic stress conditions. OsCEP1 expression was not significantly altered in various stress conditions. Its expression remained approximately two times upregulated when compared with the control but did not change much among different stress conditions and time points. In contrast to OsCEP1, the expression of OsCEP8, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10 changed notably in stress conditions. In salinity, stress, OsCEP8, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10 were highly upregulated. OsCEP8 expression went from 24-fold to 28-fold while OsCEP9 expression almost doubled up changing from 25-fold to 49-fold when rice seedling was subjected to salinity stress. OsCEP9 and OsCEP8 expression patterns were quite similar in case of drought stress, i.e., at an early time point, the expression of both the genes was downregulated, followed by an increase during later stages of drought stress. OsCEP8 was initially one-hundred-thirty-seven times downregulated while OsCEP9 was only three-fold downregulated. At the later stage of drought stress, OsCEP8 expression was upregulated almost five times, and on the other hand, OsCEP9 was upregulated by 34-fold. OsCEP10 expression pattern was quite the opposite in salinity and drought stress. In the case of salinity stress, OsCEP10 was an early responsive gene, while in drought stress, it acted as a late responsive gene. The 24-fold high expression changed to a two-fold change in salinity stress and 1.7-fold change to a 25-fold change in drought stress. OsCEP13 expression did not vary significantly among various stress conditions.

Discussion

Abiotic stress negatively impacts the growth and productivity of crop plants worldwide (Lamaoui et al. 2018). Plant adaptation to environmental stresses is controlled by a cascade of molecular networks involving expression of stress-associated genes, phytohormones, transcription factors, etc. It leads to the activation of stress-responsive mechanisms to protect and repair damaged proteins and membranes and to re-establish homeostasis. Small, secreted signaling peptides work in parallel with phytohormones to control important aspects of plant growth and development. In some cases, they are encoded by genes in their own right, but in others, they are derived from the post-translational modification of larger proteins. Plant peptide hormones are short peptides that bind to receptor kinases and initiate a signaling cascade in response to internal or external stimuli (Gancheva et al. 2019). Peptide hormone genes of the CEP family have been implicated as potent regulators of plant developmental processes. CEP genes encode for N-terminal secretion signal (NSS), a variable domain, one or more CEP domains, and a short C-terminal extension (Tavormina et al. 2015). CEP genes negatively regulate plant root development in abiotic stress (Matsubayashi 2011). CEP genes were found to be associated with the development of lateral root and nodules, regulating the growth of root and stem, and response to nitrogen deficiency conditions (Taleski et al. 2018; Roberts et al. 2016). They have also been implicated in abiotic stress response (Stührwohldt and Schaller 2019).

Genome-wide analysis of CEP genes leads to the identification of multiple gene members in different crop species. The presence of a myriad of CEP genes in all these species viz. twenty-seven in Glycine max, twenty-four in Brassica rapa, and fifteen in Oryza sativa suggests a wide range of functions adopted by CEP genes for growth and survival of plants. CEP genes were randomly distributed across the genome of all species. In rice, one tandem array pair was found comprising of four genes, namely OsCEP7, OsCEP8, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10, which is quite rare. Mostly tandem duplications reported in Arabidopsis or rice contain only two genes (Rizzon et al. 2006), but, recently tandem arrays containing 3 genes have been reported in orchids (Kuo et al. 2019). Tandem gene duplication is one of the ways by which gene families grow in size. The presence of tandemly duplicated CEP gene pairs suggests that tandem duplications might have played a crucial role in the expansion of CEP gene families.

CEP genes promoter region has cis-acting regulator elements not only related to stress but also various elements involved in the growth and development of plants such as phytohormone response, cell cycle, and light response (Fig. 2). Therefore it was essential to look at the expression pattern of CEP genes in various developmental stages (Fig. 4). Different CEP genes are expressed in different parts of plants such as callus, seed, embryo, root, shoot, flower, siliques, stem, and leaf. However, upon comparison, we found that CEP genes were more likely to express in various roots tissues (primary root, secondary root, root elongation zone) than in other parts of plants. Out of the five CEP genes in Sorghum, three genes (SbCEP1, SbCEP2, and SbCEP3) were expressed only in root tissues (Fig. 4b). In Zea mays, most of the CEP genes were expressed in different tissues/zones of root tissues (Fig. 4d). Similarly, in rice and Brassica, two and six CEP genes showed root-specific expression, respectively (Fig. 4a, c).

Orthologous CEP gene pairs (SbCEP2 and ZmCEP9; AtCEP15 and BrCEP4) were also highly expressed in roots. Previous studies have shown that CEP genes are highly expressed in roots and are involved in inhibition of primary root length and lateral root number (Roberts et al. 2013a, b, 2016; Mohd-radzman et al. 2015; Li et al. 2018). Our study also shows that CEP genes are expressed to a greater extent in roots and other parts of plants. Roots are the primary source of stress signaling mechanism in plants, and the expression of several CEP genes in various root tissues further points to the role of CEP genes in the stress signaling pathway.

Transcription is the first step in gene regulation; analysis of transcriptome data is essential for the discovery and functional characterization of the gene. The role of cis-regulatory elements in abiotic stress conditions is well known (Sheshadri et al. 2016). Their presence or absence or variation in the sequence has a high impact on the expression of genes, and identifying cis-acting regulatory sequences can help in understanding the role of a particular gene. Analysis of promoter sequences of the identified CEP genes revealed that stress and ABA-responsive elements are most abundant among the CEP genes. Also, these elements were present in numerous copies across the upstream region of CEP genes. MYC recognition site, MYCCONSENSUSAT found in the promoters of the dehydration-responsive gene RD22 (Chinnusamy et al. 2004,) was present 25, 22, and 20 times in OsCEP13, OsCEP10, and OsCEP8, respectively. On comparison, we found that MYC and MYB binding/recognition sequences and ABA response elements are most commonly present across all CEP genes. Transcription factors such as MYB, WRKY, bZIP, MADS, bHLH are among major and most studied transcription factors that play an essential role in activation or repression of biochemical and developmental processes during abiotic stress conditions (Chen et al. 2012; Zou et al. 2008; Castelán-muñoz et al. 2019; Koini et al. 2009). Furthermore, a predominant presence of binding sites of these transcription factors in the upstream region of CEP genes suggests that CEP genes might be regulated by these transcription factors and involved in abiotic stress signaling.

Rapid and coordinated changes occur at the transcript level of the entire gene networks in response to diverse stress conditions in rice (Santos et al. 2011). To comment on the transcript alterations in CEP genes in response to stress, publicly available microarray and RNA seq data sets were employed to study the expression pattern of OsCEP genes. In all cereal plants, domestication has resulted in extensive genomic and functional divergence within the subspecies (Zhang et al. 2011). The Difference in the expression pattern might be due to the difference in the amount of stress, stage as well as variety. The RNA seq data was available from leaf tissue of 2-week-old seedlings of Nipponbare variety exposed to 300 mM NaCl for 1 h, 5 h and 24 h whereas the qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 6) was done from 10- day old seedling of IR64 rice variety exposed to 200 mM NaCl stress for 1 h and 24 h. Microarray data from IR64 variety (Fig. 4a) was also analyzed as RNA seq data from IR64 species was not available. Both microarray and RNA seq data analysis shows that CEP genes were significantly differentially regulated in various abiotic stress conditions. OsCEP8, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10 in rice were highly upregulated in salinity and drought conditions while ZmCEP7 was induced in response to heat stress. Heavy metal stresses also induced CEP gene expression. OsCEP3 was found to be upregulated in response to cadmium stress, while OsCEP8 and OsCEP9 were induced under chromium stress. Microarray and RNA seq data were validated by qRT-PCR analysis. Expression of OsCEP8, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10 genes was highly upregulated in both roots and shoot tissues in the early stages of abiotic stress conditions (Fig. 6). Previously reported studies also show that CEP genes are expressed under nutrient-deficient conditions such as nitrogen starvation (Taleski et al. 2018). In apple, MdCEP expression was significantly upregulated in response to different environmental cues such as NaCl, cold (4 °C), exogenous ABA, etc. (Li et al. 2018). A comparison of the protein sequence of the MdCEP17 gene (reported to be highly expressed under ABA treatment) with SbCEP1 revealed high protein similarity. RNA seq data shows that SbCEP1 was also highly expressed after ABA treatment. Thus, the findings of the present study are consistent with previously reported studies in Arabidopsis and apple. This might be due to the presence of several repeats of ACGT sequence in the upstream region, which are known to the essential for ERD1 expression (early responsive gene to dehydration) (Alves et al. 2011). The microarray and RNA-seq data analysis also revealed that the external application of ABA influences CEP gene expression. The expression of OsCEP9, OsCEP10, SbCEP1, SbCEP4, and SbCEP5 genes was upregulated in response to ABA (Fig. 5a (ii), b (vii)). It might be correlated with the fact that the promoter region of these genes contains numerous repeats of binding sites of ABA-responsive genes such as RD22, ABI5, ABI3, and ABI1 (Supplementary sheet 1). The expression of apple MdCEP genes was induced by environmental cues as well as ABA treatment (Li et al. 2018). ABA acts as an endogenous messenger in plants in abiotic stress response. Any abiotic stress results in the synthesis of ABA, accompanied by alteration of gene expression and, consequently, an adaptive physiological response to the stress such as structure and regulation of stomatal function and seed dormancy (Christmann et al. 2005; Hirayama and Shinozaki 2007). During this process, ABA also acts in intricate cross-communication with other phytohormones, such as gibberellic acid, ethylene, auxin, and brassinosteroids (Alves et al. 2011). Therefore, ABA-responsive elements present in the promoter region of CEP genes might result in the regulation and expression of CEP genes in response to abiotic stress conditions.

OsCEP genes show genotype/developmental stage and stress-specific expression pattern wherein genes show temporal and spatial specificity. The CEP genes might play a significantly important role in abiotic stress response. There are several inconsistencies w.r.t role in these processes via interaction with downstream signaling members as their full story is yet to be uncovered (Roberts et al. 2016, Tabata et al. 2014). It would be worthwhile to explore the role of OsCEP genes showing alterations under stress conditions through overexpression and knockout studies. Genes that are perturbed under stress, i.e., upregulated (OsCEP8, OsCEP9, and OsCEP10) and down-regulated (OsCEP5), may serve as good candidates for gene editing/engineering studies to study the effect of these genes on stress mitigation. This study provides significant evidence to investigate further and validate the role of CEP(s) in different abiotic stress conditions.

Conclusion

In recent years, abiotic stress management is a primary concern for developing high yielding stress-tolerant crop varieties. Therefore, it is vital to study the molecular mechanism of abiotic stress-induced gene expression. This study indicates that some of the CEP genes are induced under abiotic stress and have a role in its signaling mechanism, which needs to be dissected further to harness them in engineering stress-resilient crop plants.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by Science and Engineering Research Board (Grant No. YSS/2015/00401) to SK.

Abbreviations

- CEP

C-terminally encoded peptide

- AA

Amino acid

- CAREs

Cis-acting regulatory elements

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- ACC

1-Aminocyclopropane 1-carboxylic acid

- JA

Jasmonic acid

- SA

Salicylic acid

Authors contributions

The idea, concept, design of experiments and manuscript preparation were done by AM. SK helped in developing the concept and critically reviewed the manuscript. SA, AS and KS carried out the bioinformatics analysis. Wet lab experiments were performed by SA. SK, JS and MJ helped in performing the experiments and preparation of manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alves MS, Fontes EPB, Fietto LG. Early responsive to dehydration 15, a new transcription factor that integrates stress signaling pathways. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:1993–1996. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.12.18268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batth R, Singh K, Kumari S, Mustafiz A. Transcript profiling reveals the presence of abiotic stress and developmental stage specific ascorbate oxidase genes in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8(February):1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol) 1995;57(1):289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bobay BG, Digennaro P, Scholl E, Imin N, Djordjevic MA, Bird DM. Solution NMR studies of the plant peptide hormone CEP inform function. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(24):3979–3985. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AC, Obaidi A, Wierzba M, Tax FE. Xylem intermixed with Phloem1, a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase required for stem growth and vascular development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2012;235(1):111–122. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10(1):421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelán-muñoz N, Herrera J, Cajero-sánchez W, Arrizubieta M. MADS-Box genes are key components of genetic regulatory networks involved in abiotic stress and plastic developmental responses in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:853. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Song Yu, Li S, Zhang L, Zou C, Diqiu Yu. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant abiotic stresses ☆. BBA Gene Regul Mech. 2012;1819(2):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V, Schumaker K, Zhu J-k. Molecular genetic perspectives on cross-talk and specificity in abiotic stress signalling in plants. J Exp Bot. 2004;55(395):225–236. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christmann A, Hoffmann T, Teplova I, Grill E, Müller A. Generation of active pools of abscisic acid revealed by in vivo imaging of water-stressed arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2005;137(1):209–219. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.053082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delay C, Imin N, Djordjevic MA, Sui Z, Wang T, Li H, Zhang M, et al. CEP genes regulate root and shoot development in response to environmental cues and are specific to seed plants. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(17):5383–5394. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delay C, Imin N, Djordjevic MA. Regulation of Arabidopsis root development by small signaling peptides. Front Plant Sci. 2013 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delay C, Imin N, Djordjevic MA. CEP genes regulate root and shoot development in response to environmental cues and are specific to seed plants. J Exp Bot. 2018;64(17):5383–5394. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancheva MS, Malovichko Y, Poliushkevich LO, Dodueva IE, Lutova LA. Plant peptide hormones. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2019;66(2):171–189. doi: 10.1134/S1021443719010072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. Genome-Wide identification of glyoxalase genes in Medicago truncatula and their expression profiling in response to various developmental and environmental stimuli. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:836. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grienenberger E, Fletcher JC. Polypeptide signaling molecules in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2015;23:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatorangan MR, Sentausa E, Wijaya GY. In silico identification of cis-regulatory elements of phosphate transporter genes in rice (Oryza Sativa L.) J Crop Sci Biotechnol. 2009;12(1):25–30. doi: 10.1007/s12892-008-0054-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama T, Shinozaki K. Perception and transduction of abscisic acid signals: keys to the function of the versatile plant hormone ABA. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12(8):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huault E, Laffont C, Wen J, Mysore KS, Ratet P, Duc G, Frugier F. Local and systemic regulation of plant root system architecture and symbiotic nodulation by a receptor-like kinase. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(12):e1004891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imin N, Mohd-Radzman NA, Ogilvie HA, Djordjevic MA. The peptide-encoding CEP1 gene modulates lateral root and nodule numbers in Medicago truncatula. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(17):5395–5409. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert36910.1093/jxb/ert369?. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor M, Arora R, Lama T, Nijhawan A, Khurana JP, Tyagi AK, Kapoor S. Genome-wide identification, organization and phylogenetic analysis of Dicer-like, Argonaute, and RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase gene families and their expression analysis during reproductive development and stress in rice. BMC Genom. 2008;9:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kende H. The five ‘classical’ plant hormones. Plant Cell Online. 1997;9(7):1197–1210. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koini MA, Alvey L, Allen T, Tilley CA, Harberd NP, Whitelam GC, Franklin KA, Le L. Report high temperature-mediated adaptations in plant architecture require the BHLH transcription factor PIF4. Curr Biol. 2009;19(5):408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Yokomine K, Nakagawa A, Sakagami Y. Analogs of the CLV3 peptide: synthesis and structure–activity relationships focused on proline residues. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52(1):30–36. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YT, Chao YT, Chen WC, Shih MC, Chang SB. Segmental and tandem chromosome duplications led to divergent evolution of the chalcone synthase gene family in Phalaenopsis orchids. Ann Bot. 2019;123(1):69–77. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaoui M, Jemo M, Datla R, Bekkaoui F. Heat and drought stresses in crops and approaches for their mitigation. Front Chem. 2018;6:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lease KA, Walker JC. The Arabidopsis unannotated secreted peptide database, a resource for plant peptidomics. Plant Physiol. 2006;142(3):831–838. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner M, Findeiß S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: detection of (co-) orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, An J, You C, Shu J, Wang X, Hao Y. Identification and expression of the CEP gene family in apple (Malus × domestica) J Integr Agric. 2018;17(2):348–358. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(17)61653-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Cheng X, Wang Y, Yin X, Li Z, Liu R, Liu G, Wang Y, Yan X. Genome-wide analysis of glyoxalase-like gene families in Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) and their expression profiling in response to downy mildew infection. BMC Genom. 2019;20(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5733-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 − δδCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15(12). 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matsubayashi Y. Small post-translationally modified peptide signals in Arabidopsis. Arabidopsis Book. 2011;9:e0150. doi: 10.1199/tab.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y. Exploring peptide hormones in plants: identification of four peptide hormone-receptor pairs and two post-translational modification enzymes. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B. 2018;94(2):59–74. doi: 10.2183/pjab.94.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y, Ogawa-Ohnishi M, Mori A, Matsubayashi Y. Secreted peptide signals required for maintenance of root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Science. 2010;329(5995):1065–1067. doi: 10.1126/science.1191132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd-Radzman NA, Binos S, Truong TT, Imin N, Mariani M, Djordjevic MA. Novel MtCEP1 peptides produced in vivo differentially regulate root development in Medicago truncatula. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(17):5289–5300. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd-Radzman NA, Laffont C, Ivanovici A, Patel N, Reid DE, Stougaard J, Frugier F, Imin N, Djordjevic MA. Different pathways act downstream of the peptide receptor CRA2 to regulate lateral root and nodule development. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:2536–2548. doi: 10.1001/jama.1899.92450700018001f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Smith S, De Smet I. Small signaling peptides in arabidopsis development: how cells communicate over a short distance. Plant Cell. 2012;24(8):3198–3217. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.099010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie HA, Imin N, Djordjevic MA. Diversification of the C-terminally encoded peptide (CEP) gene family in angiosperms, and evolution of plant-family specific CEP genes. BMC Genom. 2014;15(1):870. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo Y, Tanaka M, Tabata R, Ogawa-Ohnishi M, Matsubayashi Y. Shoot-to-root mobile polypeptides involved in systemic regulation of nitrogen acquisition. Nat Plants. 2017;3:1–6. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama K, Ogawa M, Matsubayashi Y. Identification of a biologically active, small, secreted peptide in Arabidopsis by in silico gene screening, followed by LC-MS-based structure analysis. Plant J. 2008;55:152–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama K, Ogawa M, Matsubayashi Y, Delay C, Imin N, Djordjevic MA, Tabata R, et al. Perception of root-derived peptides by shoot LRR-RKs mediates systemic N-demand signaling. Science (New York, NY) 2014;346(6207):343–346. doi: 10.1126/science.1257800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N, Mohd-radzman NA, Corcilius L, Crossett B, Connolly A, Cordwell SJ, Ivanovici A, et al. Diverse peptide hormones affecting root growth identified in the Medicago truncatula secreted peptidome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2018;17(1):160–174. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce G, Strydom D, Johnson S, Ryan CA. A polypeptide from tomato leaves induces wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor proteins. Science. 1991;253:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.253.5022.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzon C, Ponger L, Gaut BS. Striking similarities in the genomic distribution of tandemly arrayed genes in Arabidopsis and rice. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2(9):0989–1000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I, Smith S, De Rybel B, Van Den Broeke J, Smet W. The CEP family in land plants: evolutionary analyses, expression studies, and role in Arabidopsis shoot development. J Exp Bot. 2013 doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I, Smith S, De Rybel B, Van Den Broeke J, Smet W, De Cokere S, Mispelaere M, et al. The peptide-encoding CEP1 gene modulates lateral root and nodule numbers in Medicago truncatula. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(17):5371–5381. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I, Smith S, Stes E, De Rybel B, Staes A, Van De Cotte B, Njo MF, et al. CEP5 and XIP1/CEPR1 regulate lateral root initiation in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(16):4889–4899. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos AP, Serra T, Figueiredo DD, Barros P, Lourenço T, Chander S, Oliveira MM, Saibo Nelson JM. Transcription regulation of abiotic stress responses in rice: a combined action of transcription factors and epigenetic mechanisms. OMICS. 2011;15(12):839–857. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheshadri SA, Nishanth MJ, Simon B. Stress-mediated cis-element transcription factor interactions interconnecting primary and specialized metabolism in planta. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–23. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara H, Matsubayashi Y. Arabinosylated glycopeptide hormones: new insights into CLAVATA3 structure. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:515–519. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhrwohldt N, Schaller A. Regulation of plant peptide hormones and growth factors by post-translational modification. Plant Biol. 2019 doi: 10.1111/plb.12881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui Z, Wang T, Li H, Zhang M, Li Y, Ruibin X, Xing G, Ni Z, Xin M. Overexpression of peptide-encoding OsCEP6.1 results in pleiotropic effects on growth in rice (O. sativa) Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata R, Sumida K, Yoshii T, Ohyama K, Shinohara H, Matsubayashi Y. Perception of root-derived peptides by shoot LRR-RKs mediates systemic N-demand signaling. Science. 2014;346(6207):343–346. doi: 10.1126/science.1257800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taleski M, Imin N, Djordjevic MA. New role for a CEP peptide and its receptor: complex control of lateral roots. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(16):4798–4799. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taleski M, Imin N, Djordjevic MA. CEP peptide hormones: key players in orchestrating nitrogen-demand signalling, root nodulation, and lateral root development. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(8):1829–1836. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Ogawa-ohnishi M. Shoot-to-root mobile polypeptides involved in systemic regulation of nitrogen acquisition. Nat Plants. 2017;3(4):1–6. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavormina P, De Coninck B, Nikonorova N, De Smet I, Cammuea Bruno PA. The plant peptidome: an expanding repertoire of structural features and biological functions. Plant Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford R, Fernandez A, Tejos R, Pérez AC, Kleine-Vehn J, Vanneste S, Drozdzecki A, et al. GOLVEN secretory peptides regulate auxin carrier turnover during plant gravitropic responses. Dev Cell. 2012;22(3):678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Belcram H, Gornicki P, Charles M, Just J, Huneau C, Magdelenat G, et al. Duplication and partitioning in evolution and function of homoeologous Q loci governing domestication characters in polyploid wheat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(46):18737–18742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110552108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou M, Guan Y, Ren H, Zhang F, Chen F. A BZIP transcription factor, OsABI5, is involved in rice fertility and stress tolerance. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;66(6):675–683. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.