Abstract

Objective:

Comparing the prediction models for the ISUP/WHO grade of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) based on CT radiomics and conventional contrast-enhanced CT (CECT).

Methods:

The corticomedullary phase images of 119 cases of low-grade (I and II) and high-grade (III and IV) ccRCC based on 2016 ISUP/WHO pathological grading criteria were analyzed retrospectively. The patients were randomly divided into training and validation set by stratified sampling according to 7:3 ratio. Prediction models of ccRCC differentiation were constructed using CT radiomics and conventional CECT findings in the training setandwere validated using validation set. The discrimination, calibration, net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement index (IDI) of the two prediction models were further compared. The decision curve was used to analyze the net benefit of patients under different probability thresholds of the two models.

Results:

In the training set, the C-statistics of radiomics prediction model was statistically higher than that of CECT (p < 0.05), with NRI of 9.52% and IDI of 21.6%, both with statistical significance (p < 0.01).In the validation set, the C-statistics of radiomics prediction model was also higher but did not show statistical significance (p = 0.07). The NRI and IDI was 14.29 and 33.7%, respectively, both statistically significant (p < 0.01). Validation set decision curve analysis showed the net benefit improvement of CT radiomics prediction model in the range of 3–81% over CECT.

Conclusion:

The prediction model using CT radiomics in corticomedullary phase is more effective for ccRCC ISUP/WHO grade than conventional CECT.

Advances in knowledge:

As a non-invasive analysis method, radiomics can predict the ISUP/WHO grade of ccRCC more effectively than traditional enhanced CT.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common malignant tumor in adult kidneys, and the clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the most common type, accounting for 70–75% of RCC. Compared with papillary RCC (pRCC) and chromophobe cell carcinoma (chRCC), ccRCC has a worse prognosis.1,2 According to the 2018 European Society of Urology (EAU) Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of RCC, the prognostic factors of RCC include anatomy, histology, clinic and molecular level.3 Histologically, high-grade RCC has a worse prognosis than low-grade RCC.4,5 The National comprehensive cancer network (NCCN) 2018 guidelines also point out that cancer grade is one of the prognostic determinants of 5 year survival in RCC patients.6 Fuhrman nuclear grading is the most widely accepted grading system, and is an independent prognostic factor for RCC.7 Previous studies have shown that the predictive accuracy of improved and simplified two- or three-strata system may be comparable to that of traditional four-tiered grading scheme.8–10 However, Fuhrman nuclear classification system does not consider the latest tissue subtypes of RCC, and there are discrepancies between intra- and interobserver11 and has poor interpretability. Therefore, the International Society for Urology and Pathology (ISUP) has issued the new ISUP/WHO grading system to replace Fuhrman nuclear grading system.12,13 It has been reported that ISUP/WHO grading system is related to the prognosis of ccRCC patients.14

Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) is the most commonly used imaging method for early detection and diagnosis of renal tumors.15 However, the evaluation of pathological grade of RCC is often influenced by the subjectivity of radiologists. In recent years, the combination of large data technology and artificial intelligence diagnosis of medical imaging has produced a new radiomics method. It has important clinical value and advantages to extract a large number of features from images to reflect the heterogeneity of tumor tissue.16 Radiomics, by the application of advanced computer methods to solve specific clinical problems, will have broad application prospects, for the tumor to bring new analytical methods.

Therefore, our study intended to compare the prediction models for the ISUP/WHO grade of ccRCC based on the CT radiomics and the conventional CECT, so as to provide more evidence for evaluating the prognosis for patients with ccRCC.

Methods

Study population

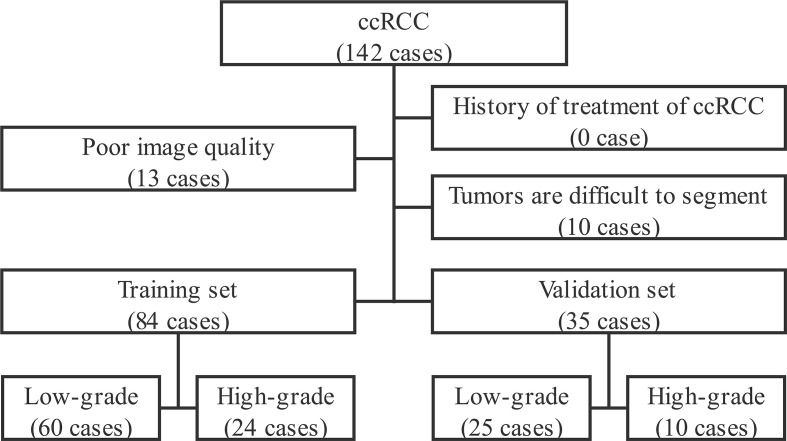

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and the consents from patients were waived. Patients with ccRCC and met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria in our institution (Affiliated Hospital of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine) were continuously collected from March 2014 to March 2019.Inclusion criteria: a. with the complete enhanced CT scan data of the mid-abdomen; b. tumors confirmed pathologically by surgery or puncture biopsy; c. with complete clinical data. Exclusion criteria: a. poor image quality affected image analysis and radiomics feature extraction; b. Tumors were invasive,causing unclear boundary between tumor and normal renal parenchyma and making it hard for clear segmentation manually.c. Patients with RCC received treatment before CT enhanced scan. The flowchart is shown in Figure 1. A total of 119 patients were enrolled in the study. The patients were randomly divided into the training set and validation set by stratified sampling according to the ratio of 7:3. The basic characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for ccRCC patient enrollment. ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Table 1.

The comparison of patient characteristics between the training and validation sets

| Parameters | Total | Training set | Validation set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-grade (n = 60) | High-grade (n = 24) |

P | Low-grade (n = 25) | High-grade (n = 10) |

|||

| Gender (female/male) | 41/78 | 26/34 | 9/15 | 0.62 | 6/19 | 0/10 | 0.15 |

| Age (years) | 61.55 ± 11.57 | 60.28 ± 12.51 | 62.88 ± 9.30 | 0.36a | 64.84 ± 11.35 | 57.80 ± 9.65 | 0.09a |

| Visible hamaturesis (no/yes) | 105/14 (11.8%) | 56/4 | 22/2 | 1.00 | 20/5 | 7/3 | 0.66 |

| Flank pain (no/yes) | 93/26 (21.8%) | 48/12 | 17/7 | 0.40 | 20/5 | 8/2 | 1.00 |

| Palpable abdominal mass (no/yes) | 113/6 (5.0%) | 59/1 | 24/0 | 1.00 | 22/3 | 8/2 | 0.61 |

| Non-urinary cancer (no/yes) | 102/17 (16.7%) | 53/7 | 21/3 | 1.00 | 21/4 | 7/3 | 0.38 |

For independent sample Student’s t-test, the others were with Fisher exact probability method or χ2 test.

Determination of ISUP/WHO of ccRCC

Post-operative histopathological specimens of all patients were re-diagnosed and graded by two pathologists (with 8- and 12 years’ experience in renal pathology) according to the ISUP/WHO pathological grading criteria of the 2016 edition of renal cancer. Patients with Grade I and II were further defined as low-grade group, and III and IV were defined as high-grade group for analysis. The final grade was decided by the two pathologists after consulting each other.

CT data acquisition

All patients signed informed consent before CT scanning. The unenhanced and three phases contrast-enhanced scans in the corticomedullary phase, nephrographic phase and excretion phase were performed in a 64-slice scanner (Discovery CT 750HD, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI,) using the dual-energy spectral imaging mode. The scan covered the entire kidney. The Gemstone Spectral Imaging (GSI) protocol GSI-1: 630 mA was used with the following scan parameters: rotation speed 0.5 s/rot, pitch 1.375:1, scan field of view 50 cm, and collimation 64*0.625 mm. Non-ionic contrast agent Ioversol (350 mg I/ml, Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co. Ltd., China) was used as the contrast agent for the enhanced scanning, and Ulrich (Ulrich, Germany) high pressure syringe was used to inject contrast agent at a dose of 450 mg I/kg of body weight through the right anterior elbow vein. The injection flow rate was 3.5–4.0 ml s−1.

Traditional imaging features of ccRCC

Two abdominal radiologists (with 5 and 8 years of experience in CT abdominal imaging) evaluated the unenhanced and enhanced CT images of each patient, and identified the tumor characteristics including location, size, growth pattern, capsule, necrosis, cystic, calcification, intertumoral artery, perinephric fat invasion, venous involvement (VI), enlargement of lymphnodes (ELN), metastasis, enhancement mode, and enhancement uniformity. The results were finalized by the two radiologists after consulting each other.

VOI delineation and radiomics features calculation

The original data were reconstructed into 1.25 mm virtual monochromatic image sets using the adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction (ASIR) algorithm at 40% strength. The corticomedullary phase images at 70 keV energy level17 were imported into ITK-Snap v.3.4.0 software (An open source software for medical image segmentation, URL https://www.itksnap.org/.), and the volume of interest (VOI) for the entire tumor of ccRCC was delineated by another radiologist (with 7 years of experience in CT abdominal imaging), including necrosis, cystic change, capsule and calcification. The VOI did not contain extraneoplastic tissue, extraneoplastic blood vessels and retroperitoneal/hilar enlarged lymph nodes. The VOI was then saved as a boundary file (.nii file format, used to preserve the spatial location of ccRCC), which was manually revised by another radiologist (with 13 years’ experience in CT abdominal imaging) after 1–2 months to ensure the accuracy of the boundary file.18 The boundary file and the DICOM data were imported into a radiomics analysis software (Artificial Intelligence Kit v.3.1.0.R, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) to calculate the radiomics features of ccRCC. These features included five categories: Histogram, Gray Level Co-ocurrence Matrix, Gray level size zone matrix, Gray Level Run-length Matrix, and Form-Factor. The steps of Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix and Gray Level Run-length Matrix were set to 1, 4 and 7. A total of 396 radiomics features were calculated.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by using R v. 3.5.2 (A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.) and SPSS® v. 25.0. (IBM Corp., New York, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), with p < 0.05 indicating statistically significant difference. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The independent samples Student’s t-test was used to test the parameters when data were consistent with normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, otherwise the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Categorical variables were compared by using χ2 test or Fisher exact probabilities method. Weighted-Kappa test was used for ordered multi classification parameters and κ test was used for binary classification parameters. The Weighted-Kappa or κ values were defined as follows: κ value >0.75, excellent agreement; 0.60–0.74, good agreement; 0.40–0.59, fair agreement; and κ value <0.40, poor agreement.

Because there were many radiomics features, there were varying degrees of correlation among these features. In order to prevent the model from being over fitted, the training set used The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)19 regression to screen the radiomics features of ccRCC, which was suitable for penalty estimation of high-dimensional data, and to establish the radiomics risk score (RRS) according to the coefficients of the features after dimension reduction. In LASSO regression, glmnet package in R was used to determine the optimal λ value by cross-validation method, and the corresponding LASSO regression model was selected with the λ value.

With the simplified pathological grading as the reference standard, binary logistic regression was used to construct parametric prediction models based on CECT and radiomics for predicting the differentiation of ccRCC in the training set. ROC was drawn to evaluate the diagnostic efficiency of the two models, and C-statistics, sensitivity and specificity were calculated. Then the two prediction models were applied to the validation set, and the C-statistics, sensitivity and specificity were again calculated. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to evaluate the calibration of the two models in the training set and validation set. Delong method was used to compare the C-statistics of the two prediction models. Net reclassification index (NRI) and Integrated discrimination improvement index (IDI) were used to evaluate the improvement of the radiomics model relative to CECT. Decision curve analysis (DCA)20 was used to analyze patients' net benefits under different probability thresholds.

Results

General information of patients

There was no significant difference in sex, age, visible hematuresis, flank pain, palpable abdominal mass, and non-urinary cancer between the low-grade and high-grade patients (all p > 0.05), whether in training or validation set (Table 1). The proportion of the classic triad was 1.7% (2/119). 66.4% (79/119) of the patients had no obvious symptoms.

ISUP/WHO Grade of ccRCC

The weighed-Kappa value of the consistency test of two pathologists in the four grades of ccRCC was 0.773 (p < 0.01), and the κ value in the binary grade was 0.744 (p < 0.01). The final grades of ccRCC were: 46 cases of Grade I, 39 cases of Grade II, 30 cases of Grade III and 4 cases of Grade IV, and the simplified grades were: 85 cases of low-grade, 34 cases of high-grade.

Establishment of Prediction Model Based on CECT

Traditional imaging features of ccRCC

The subjective evaluation of the conventional CECT features by the two radiologists was in good agreement. The κ values were greater than 0.75 (all p < 0.01). Comparisons of CECT image features between the high- and low-grade levels in the training and validation sets are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics comparison between the two groups

| Parameters | Total | Training set | Validation set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-grade (n = 60) | High-grade (n = 24) |

Low-grade (n = 25) | High-grade (n = 10) |

||||

| Location (left/right) | 60/59 | 28/32 | 15/9 | 0.23 | 11/14 | 6/4 | 0.47 |

| Size (mm) | 51.98 ± 28.05 | 42.35 ± 25.20 | 63.21 ± 26.73 | <0.01a | 54.37 ± 26.75 | 67.60 ± 27.11 | 0.20a |

| Growth pattern (non-invasive/invasive) | 84/35 | 53/7 | 8/16 | <0.01 | 20/5 | 3/7 | 0.02 |

| Capsule (no/yes) | 37/82 | 14/46 | 11/13 | 0.04 | 5/20 | 7/3 | 0.02 |

| Necrosis (no/yes) | 61/58 | 45/15 | 4/20 | <0.01 | 10/15 | 2/8 | 0.43 |

| Cystic (no/yes) | 55/64 | 19/41 | 15/9 | 0.01 | 12/13 | 9/1 | 0.03 |

| Calcification (no/yes) | 98/21 | 51/9 | 18/6 | 0.35 | 21/4 | 8/2 | 1.00 |

| Intertumoral artery (no/yes) | 48/71 | 31/29 | 6/18 | 0.03 | 9/16 | 2/8 | 0.45 |

| Perinephric fat invasion (no/yes) | 69/50 | 44/16 | 7/17 | <0.01 | 14/11 | 4/6 | 0.47 |

| VI (no/yes) | 102/17 | 52/8 | 16/8 | <0.01 | 21/4 | 7/3 | 0.38 |

| ELNs (no/yes) | 79/40 | 47/13 | 9/15 | <0.01 | 21/4 | 2/8 | <0.01 |

| Metastasis (no/yes) | 95/24 | 55/5 | 15/9 | <0.01 | 20/5 | 5/5 | 0.11 |

| Enhancement mode (washout/DE) | 104/15 | 53/7 | 18/6 | 0.18 | 25/0 | 8/2 | 0.08 |

| Enhancement uniformity (yes/no) | 16/103 | 11/49 | 2/22 | 0.33 | 2/23 | 1/9 | 1.00 |

VI, venous involvement; ELNs, enlargement of locoregional lymphonodus; DE, delay enhancement.

For independent sample student-t test, the others were with Fisher exact probability method or χ2 test.

Model of CECT

The simplified pathological grading was used as dependent variable, and CECT features were used as independent variable to be included in the binary logistic regression. The results showed that tumor growth pattern and necrosis were independent risk factors for predicting the ISUP/WHO grade of ccRCC. Odds ratio of the growth pattern were 5.60 (95% CI: 1.47–21.40), p < 0.05, and necrosis Odds ratio was 6.30 (95% CI: 1.55–25.72), p = 0.01. The prediction model was Yradiology = 1/(1 + exp(-Z)), Z = 1.722 * Growth +1.841 * Necrosis - 2.553. The prediction model was internally validated by Bootstrap method and the C-statistics was 0.84 (95%CI: 0.74–0.94). The sensitivity and specificity was 87.5 and 73.3%, respectively, Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test results show that the calibration of the prediction model was good (χ2 = 5.50, p = 0.78).

Establishment of prediction model based on radiomics

Dimension reduction of radiomics features and establishment of RRS

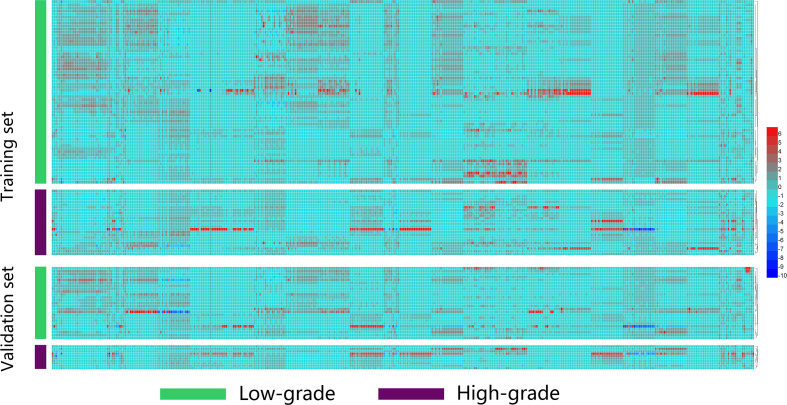

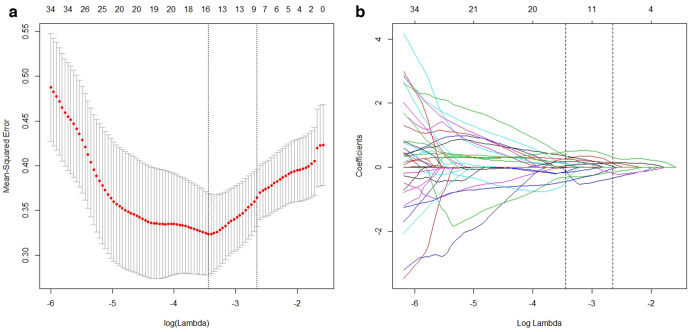

A total of 396 radiomics features were extracted from each ccRCC. The heat map is shown in Figure 2. After standardizing these features with Z-score, LASSO regression was used to reduce the dimension of the data, and the optimal λ value was determined to be 0.03198681 (log(λ)=−3.44) by cross-validation (Figure 3). A total of 17 non-zero coefficients were screened out, and the coefficients are shown in Table 3. According to the sum of the product of these 17 features and their coefficients, the RRS was established. The RRS of the high- and low-grade groups were −1.95 ± 1.08 and 0.48 ± 1.23 in the training set, respectively, with statistical significance (t = −8.99, p < 0.01) and −1.37 ± 1.25 and 0.66 ± 0.93 in the validation set, respectively, with statistical significance (t = −4.63, p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Heatmap of radiomics for visualizing the distribution difference of the low- and high-grade ccRCC in training set and validation set. ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Figure 3.

LASSO regression cross-validation diagram and regression coefficient diagram, the upper horizontal axis is the number of radiomics features corresponding to the models. The two vertical dashed lines in Figure 3A show the two log (λ) values for minimum mean-squared error minimum and the increase of 1 SD (one standard deviation) mean-squared error minimum determined by cross-validation. Figure 3B shows that with the increase of log (λ), the radiomics features coefficients were gradually compressed to 0, and the number of features was reduced to 17 by the log (λ) with minimum mean-squared error minimum. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

Table 3.

The radiomics features of non-zero coefficients screened by LASSO regression

| No. | Non-zero radiomics features | Coefficient | No. | Non-zero radiomics features | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | (Intercept) | −1.118206859 | 10 | ZGLCMEntropy_AllDirection_offset7_SD | 0.10047984 |

| 1 | ZQuantile0.975 | −0.466611265 | 11 | ZLongRunEmphasis_angle90_offset4 | 0.122333202 |

| 2 | ZShortRunHighGreyLevelEmphasis_AllDirection_offset1_SD | −0.440694599 | 12 | ZLongRunEmphasis_angle90_offset1 | 0.180743953 |

| 3 | ZInertia_angle135_offset1 | −0.310972696 | 13 | ZCompactness2 | 0.249924096 |

| 4 | ZLongRunHighGreyLevelEmphasis_angle0_offset7 | −0.161307435 | 14 | ZLongRunLowGreyLevelEmphasis_AllDirection_offset7_SD | 0.267301753 |

| 5 | ZInertia_angle90_offset1 | −0.134920077 | 15 | ZShortRunLowGreyLevelEmphasis_AllDirection_offset4_SD | 0.344677654 |

| 6 | ZPercentile95 | −0.134845433 | 16 | ZZonePercentage | 0.357469909 |

| 7 | ZLongRunHighGreyLevelEmphasis_AllDirection_offset4_SD | −0.007880575 | 17 | ZMaximum3DDiameter | 0.484997245 |

| 8 | ZLargeAreaEmphasis | 0.042493511 |

LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

Z was standardized by Z score.

Model of radiomics

With the simplified pathological grading as dependent variable, CECT features and RRS of ccRCC were taken as independent variables and included in the binary logistic regression. The results showed that all CECT features as a confounding factor did not enter the equation, only RRS was an independent risk factor for predicting the ISUP/WHO grade of ccRCC. The Odds ratio was 9.73 (95% CI: 3.36–28.13), p < 0.01. The prediction model was Yradiomics = 1/(1 + exp(-Z)), Z = 2.275 * RRS +0.733. The prediction model was internally validated by Bootstrap method and the C-statistics was 0.95 (95%CI: 0.90–0.99). The sensitivity and specificity were 91.7 and 85.0%, respectively. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test results showed that the calibration of the prediction model was good (χ2 = 3.45, p = 0.90).

Model validation

In the validation set, the C-statistics based on CECT prediction model was 0.72 (95% CI: 0.530–0.910), the sensitivity was 60.0%, and the specificity was 80.0%. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test results showed that the calibration of the prediction model was good (χ2 = 4.08, p = 0.13). The C-statistics based on radiomics prediction model was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.824–1.000), the sensitivity was 100.0%, and the specificity was 84.0%. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test results showed that the calibration of the prediction model was good (χ2 = 6.00, p = 0.54).

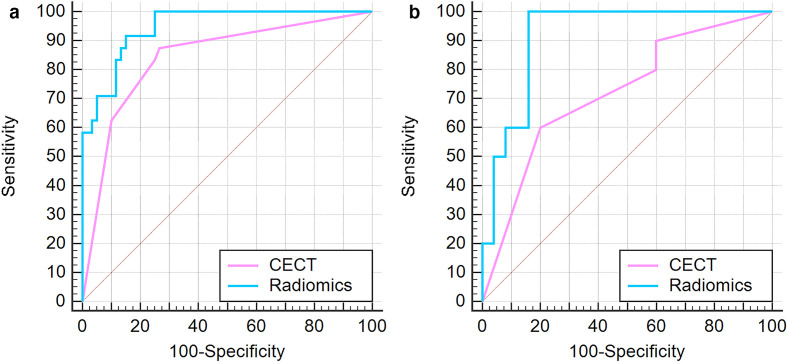

Comparison of two prediction models

In the training set, the C-statistics of the radiomics prediction model was larger than that of CECT prediction model, and had statistical significance (Z = 2.47, p < 0.05) (Figure 4A). The NRI was 9.52%, with statistical significance (Z = 3.14, p < 0.01). The IDI was 21.6%, with statistical significance (Z = 3.30, p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

(A) ROC of the two prediction models in training set, (B) ROC of the two prediction models in validation set. CECT, contrast-enhanced CT; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

In the validation set, the C-statistics of the radiomics prediction model was larger than that of CECT prediction model, but there was no significant difference (Z = 1.81, p = 0.07) (Figure 4B). NRI was 14.29%, and there was statistical significance (Z = 4.64, p < 0.01). IDI was 33.7%, with statistical significance (Z = 2.70, p < 0.01).

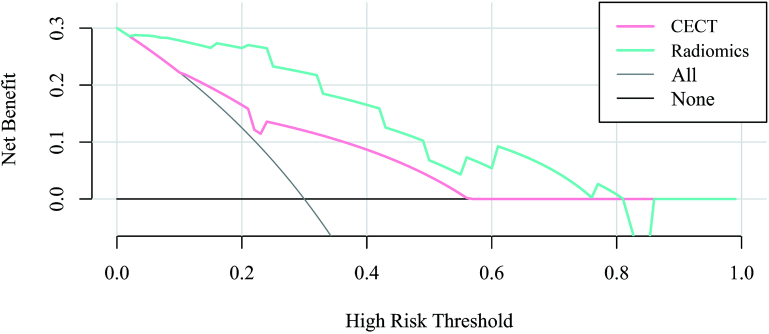

Clinical application: DCA

The validation set DCA showed that when the probability threshold of the predictive model based on CECT was in the range of 11–57%, and the probability threshold of the predictive model based on radiomics was in the range of 3–81%, the predictive pathological grading of ccRCC was better than that of all patients considered as high-grade, and also better than that of all patients considered as low-grade. The net benefit of radiomics prediction model in the range of 3–81% was greater than that of CECT prediction model (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Decision curve analysis using the validation set. CECT, contrast-enhanced CT.

Discussion

The results of our study showed that the ISUP/WHO simplified grade prediction model based on CT radiomics and conventional CECT has good discrimination and calibration. The discrimination of radiomics prediction model in the training set was greater than that of conventional CECT prediction model, and the difference was statistically significant. Although the discrimination of radiomics prediction model in the validation set was also greater than that of conventional CECT prediction model, there was no significant difference between the two models, indicating that the discrimination of the two prediction models in the validation set was similar. On the other hand, the NRI and IDI of the radiomics prediction model were improved in both the training and validation set, compared with the conventional CECT prediction model. Meanwhile, the DCA using the validation set showed that the radiomics model was better than the CECT model in patients' benefit. NRI pays more attention to a predefined cut-off, and how the new model changes the correct number of lesions compared with the old model and IDI considers different cut-offs to reflect overall improvements with the new model.The fact that we obtained positive improvements of NRI and IDI in both training and validation sets and DCA in the validation set showed that the reclassification and overall prediction ability based on the radiomics model were improved. Therefore, the prediction model based on radiomics had better diagnostic efficiency than conventional CECT.

The imaging diagnosis of ccRCC was not very difficult. Some CT findings can provide additional information on the grade of ccRCC. Previous studies have reported that tumor margin, necrosis, calcification, size, cystic change, collection system/perinephric fat invasion, locoregional lymphnodus enlargement, enhancement mode and enhancement uniformity were risk factors for predicting the grade of ccRCC in conventional CECT images.21–29 But the CT findings screened by different research centers and different samples were not all inconsistent, and there are large differences. It is suggested that the conventional CECT features can provide some additional information, but there is a certain degree of subjectivity and low specificity, and it is vulnerable to the impact of the samples of various research centers, resulting in the generalization of the prediction model being not strong.

In our study, radiomics showed a strong predictive ability for evaluating the ISUP/WHO grade of ccRCC compared with CECT. By extracting a large number of features in the tumor, the RRS was established after feature dimensionality reduction. Further multivariate analysis results showed that only the RRS was an independent risk factor for predicting the grade of ccRCC in the radiomics prediction model, and it achieved a high degree of discrimination and calibration in the training and validation sets.

Previous studies have reported the establishment of prediction models using Fuhrman nuclear grading as a reference standard, but there were few studies using ISUP/WHO as a reference standard. In Ding J et al30 study, the AUC of the prediction model based on tumors 2D texture features of corticomedullary and nephrographic phases was higher than that based on non-texture features. The results of our study were similar. A study by Shu j et al31 showed that there was no significant difference in AUC between the two predictive models constructed by nephrographic and medullary radiomics. The combined model of two phases had the highest differential diagnostic efficiency (AUC: 0.822 (95% CI: 0.769–0.866), but there was no significant difference with nephrographic phase. The Fuhrman classification of ccRCC predicted by Lin et al32 using decision tree showed that AUC in the corticomedullary phase and nephrographic phase was the largest (0.87) in unenhanced combined with enhanced scans. The AUC for the unenhanced, corticomedullary phase and nephrographic phase was 082, 0.80 and 0.84, respectively. The research results of He et al33 based on 2D-ROI to predict ISUP/WHO grade showed that AUC, a combined model of conventional CECT features and nephrographic texture features, reached a maximum of 0.986. However, corticomedullary phase or nephrographic phase alone could achieve a higher diagnostic efficiency (AUC 0.975 and 0.963, respectively). In another study of He et al,34 artificial neural networks were used to model the same samples. Their results showed that the combined model of conventional CECT features and nephrographic texture features still had the highest accuracy (94.06%), and the accuracy of corticomedullary phase or nephrographic phase alone was more than 90%. It showed that the single-phase prediction model based on radiomics could provide high diagnostic efficiency.

There are also some limitations in our study: a. Although all patients in this study chose fixed contrast agent concentration, scanning protocol and image reconstruction parameters, the volume of contrast agent was calculated according to the patient's body weight, so the effect of individual circulation difference on renal perfusion was not eliminated. b. The radiomics of medullary and excretory phase images was not analyzed in this study because of the enhancement characteristics of ccRCC, unclear demarcation between the medullary and excretory phases of tumors and normal renal parenchyma, and the presence of contrast agents in the calyx and pelvis of patients during excretory phase. VOI mapping was easily affected in some tumors closely related to the calyx and pelvis. The final results also showed that the radiomics prediction model of corticomedullary phase image alone could achieve high diagnostic efficiency in differentiating high and low differentiation of ccRCC. c. In our study, 10 cases of ccRCC with difficult boundary delineation were excluded. Most of these cases were high-grade ccRCC. These tumors often exhibited biological behavior of invasive growth. At the same time, the number of fourth-grade ccRCC in this study was too small. Therefore, there was bias in this study. d. In this study, some patients were graded according to percutaneous biopsy specimens. ISUP/WHO grading is usually used to diagnose surgical specimens. Although percutaneous biopsy can also be used to assess nuclear grading, small biopsy tissues and tumors heterogeneity still challenges the accurate grading of tumors.35,36

In conclusion, as a non-invasive analysis method, the CT radiomics prediction model in the corticomedullary phase in contrast enhanced scanning is more effective than conventional CECT in predicting the ISUP/WHO grade of ccRCC, which may provide a reference for the prognosis of patients.

Footnotes

Acknowledgment: We would like to thank Dr Jianying Li for editing the article.

Funding: Subject Innovation Team of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine(2019-YS04)

Disclosure: All authors of this manuscript declared that there were no financial interests related to the material in the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dong Han, Email: 147690660@qq.com.

Yong Yu, Email: 22434158@qq.com.

Nan Yu, Email: 349863320@qq.com.

Shan Dang, Email: dangshan849215084@qq.com.

Hongpei Wu, Email: Ljhwhp@sina.com.

Ren Jialiang, Email: renjialiang@vip.qq.com.

Taiping He, Email: hundnn@qq.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Keegan KA, Schupp CW, Chamie K, Hellenthal NJ, Evans CP, Koppie TM. Histopathology of surgically treated renal cell carcinoma: survival differences by subtype and stage. J Urol 2012; 188: 391–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capitanio U, Cloutier V, Zini L, Isbarn H, Jeldres C, Shariat SF, et al. A critical assessment of the prognostic value of clear cell, papillary and chromophobe histological subtypes in renal cell carcinoma: a population-based study. BJU Int 2009; 103: 1496–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun M, Shariat SF, Cheng C, Ficarra V, Murai M, Oudard S, et al. Prognostic factors and predictive models in renal cell carcinoma: a contemporary review. Eur Urol 2011; 60: 644–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ficarra V, Righetti R, Pilloni S, D'amico A, Maffei N, Novella G, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with renal cell carcinoma: retrospective analysis of 675 cases. Eur Urol 2002; 41: 190–8. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(01)00027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ficarra V, Righetti R, Martignoni G, D'Amico A, Pilloni S, Rubilotta E, et al. Prognostic value of renal cell carcinoma nuclear grading: multivariate analysis of 333 cases. Urol Int 2001; 67: 130–4. doi: 10.1159/000050968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minervini A, Lilas L, Minervini R, Selli C. Prognostic value of nuclear grading in patients with intracapsular (pT1-pT2) renal cell carcinoma. long-term analysis in 213 patients. Cancer 2002; 94: 2590–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang H, Lindner V, de Fromont M, Molinié V, Letourneux H, Meyer N, et al. Multicenter determination of optimal interobserver agreement using the Fuhrman grading system for renal cell carcinoma: Assessment of 241 patients with > 15-year follow-up. Cancer 2005; 103: 625–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rioux-Leclercq N, Karakiewicz PI, Trinh Q-D, Ficarra V, Cindolo L, de la Taille A, et al. Prognostic ability of simplified nuclear grading of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2007; 109: 868–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun M, Lughezzani G, Jeldres C, Isbarn H, Shariat SF, Arjane P, et al. A proposal for reclassification of the Fuhrman grading system in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2009; 56: 775–81. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker A, Hickmann D, Hansen J, Meyer C, Rink M, Schmid M, et al. Critical analysis of a simplified Fuhrman grading scheme for prediction of cancer specific mortality in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma--Impact on prognosis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016; 42: 419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delahunt B, Egevad L, Samaratunga H, Martignoni G, Nacey JN, Srigley JR. Gleason and Fuhrman no longer make the grade. Histopathology 2016; 68: 475–81. doi: 10.1111/his.12803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM, The UTM. The 2016 who classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital Organs-Part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol 2016; ; 70: 93–1052016. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delahunt B, Cheville JC, Martignoni G, Humphrey PA, Magi-Galluzzi C, McKenney J, et al. The International Society of urological pathology (ISUP) grading system for renal cell carcinoma and other prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37: 1490–504. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f0fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khor L-Y, Dhakal HP, Jia X, Reynolds JP, McKenney JK, Rini BI, et al. Tumor necrosis adds prognostically significant information to grade in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a study of 842 consecutive cases from a single institution. Am J Surg Pathol 2016; 40: 1224–31. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsili AC, Argyropoulou MI. Advances of multidetector computed tomography in the characterization and staging of renal cell carcinoma. World J Radiol 2015; 7: 110–27. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v7.i6.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, Peerlings J, de Jong EEC, van Timmeren J, et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017; 14: 749–62. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schabel C, Patel B, Harring S, Duvnjak P, Ramírez-Giraldo JC, Nikolaou K, et al. Renal lesion characterization with spectral CT: determining the optimal energy for virtual monoenergetic reconstruction. Radiology 2018; 287: 874–83. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018171657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology 2016; 278: 563–77. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tibshirani RJ. Regression shrinkage and selection via the LASSO. Journal of the Royal statistical Society. Series B: Methodological 1996; 73: 273–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making 2006; 26: 565–74. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SY, Sung DJ, Yang KS, Kim KA, Yeom SK, Sim KC, et al. Small (<4 cm) clear cell renal cell carcinoma: correlation between CT findings and histologic grade. Abdom Radiol 2016; 41: 1160–9. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0732-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh S, Sung DJ, Yang KS, Sim KC, Han NY, Park BJ, et al. Correlation of CT imaging features and tumor size with Fuhrman grade of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Acta Radiol 2017; 58: 376–84. doi: 10.1177/0284185116649795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coy H, Young JR, Douek ML, Pantuck A, Brown MS, Sayre J, et al. Association of qualitative and quantitative imaging features on multiphasic multidetector CT with tumor grade in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Abdom Radiol 2019; 44: 180–9. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1688-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C, Kang Q, Xu B, Guo H, Wei Q, Wang T, et al. Differentiation of low- and high-grade clear cell renal cell carcinoma: tumor size versus CT perfusion parameters. Clin Imaging 2017; 46: 14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huhdanpaa H, Hwang D, Cen S, Quinn B, Nayyar M, Zhang X, et al. Ct prediction of the Fuhrman grade of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC): towards the development of computer-assisted diagnostic method. Abdom Imaging 2015; 40: 3168–74. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0531-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dall'Oglio MF, Ribeiro-Filho LA, Antunes AA, Crippa A, Nesrallah L, Gonçalves PD, et al. Microvascular tumor invasion, tumor size and Fuhrman grade: a pathological triad for prognostic evaluation of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 2007; 178: 425–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J, Xu W-H, Wei Y, Qu Y-Y, Zhang H-L, Ye D-W. An integrated score and nomogram combining clinical and immunohistochemistry factors to predict high ISUP grade clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front Oncol 2018; 8: 634. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Wang Y, Yang L, Li T, Wu J, Chang R, et al. Delayed enhancement of the peritumoural cortex in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: correlation with Fuhrman grade. Clin Radiol 2018; 73: 982.e1–982.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2018.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Y-H, Wang X, Zhang J, Chen Y-H, Kong W, Huang Y-R. Low enhancement on multiphase contrast-enhanced CT images: an independent predictor of the presence of high tumor grade of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 203: W295–300. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding J, Xing Z, Jiang Z, Chen J, Pan L, Qiu J, et al. Ct-Based radiomic model predicts high grade of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Radiol 2018; 103: 51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shu J, Tang Y, Cui J, Yang R, Meng X, Cai Z, et al. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: CT-based radiomics features for the prediction of Fuhrman grade. Eur J Radiol 2018; 109: 8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin F, Cui E-M, Lei Y, Luo L-P. Ct-Based machine learning model to predict the Fuhrman nuclear grade of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Abdom Radiol 2019; 44: 2528–34. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-01992-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He X, Zhang H, Zhang T, Han F, Song B. Predictive models composed by radiomic features extracted from multi-detector computed tomography images for predicting low- and high- grade clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a STARD-compliant article. Medicine 2019; 98: e13957. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He X, Wei Y, Zhang H, Zhang T, Yuan F, Huang Z, et al. Grading of clear cell renal cell carcinomas by using machine learning based on artificial neural networks and radiomic signatures extracted from multidetector computed tomography images. Acad Radiol 2020; 27;): 30225–9pii: S1076-. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lane BR, Samplaski MK, Herts BR, Zhou M, Novick AC, Campbell SC. Renal mass biopsy--a renaissance? J Urol 2008; 179: 20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warren AY, Harrison D. WHO/ISUP classification, grading and pathological staging of renal cell carcinoma: standards and controversies. World J Urol 2018; 36: 1913–26. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2447-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]