Abstract

Background:

More than a hundred species of mammals, birds, and reptiles are infected by nematodes of the Trichinella genus worldwide. Although, Trichinella spp. are widely distributed in neighboring countries including Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey and Iran, no study was conducted in Armenia since 1980’s.

Methods:

In 2017–2018, five muscle samples belonging to Armenian lynx, otter, wild boar, fox and wolf were tested for Trichinella spp. and recovered larvae were identified by multiplex PCR technique.

Results:

Twenty-six larvae/gram and one larva/gram were found in lynx and fox samples respectively. They were identified as T. britovi.

Conclusion:

So far only two species were identified in Armenia, T. spiralis and T. pseudospiralis, and this is the first time that T. britovi is reported in Armenia.

Keywords: Lynx, Fox, Trichinella britovi, Armenia

Introduction

Trichinella spp. are some of the most widespread parasites infecting mammals (including Human) all over the world )1(. This zoonotic nematode includes a very broad range of host species, although only humans become clinically affected )2(. Trichinellosis is acquired by ingesting raw or under-cooked meat containing cysts (encysted L1 larvae) of Trichinella spp.

The first studies on the presence of Trichinella spp. in Armenia refer to 1950–60th when Trichinella spp. was detected in pigs )3(. Later in 1980–1985, wide scale investigation of Trichinella spp. diversity and distribution was conducted among set of wildlife and domestic animals (4). T. spiralis was reported in 13 different mammal species, including domestic pigs, and T. pseudospiralis was found in Turdus merula (4). Trichinella spp. are widely distributed in neighboring countries including Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey and Iran (5).

As there were no any survey conducted in Armenia after 1980’s, we decided to test five carnivorous animals muscle samples for presence of Trichinella spp.: lynx (Lynx lynx dinniki), otter (Lutra lutra), wild boar (Sus scrofa), fox (Vulpes vulpes) and wolf (Canis lupus campestris). Both of five tested samples appeared to be infected by T. britovi which is the first report of the species from Armenia.

Materials and Methods

Muscle sampling from wildlife

Collaboration with World Wildlife Fund Armenia allowed collecting some carnivorous or partly carnivorous animal muscle samples from dead animals, which included a red fox, a gray wolf, a Eurasian lynx, a Eurasian otter and a wild boar (Table 1).

Table 1:

Muscles sampling

| ID | Date | State | Locality | Species | N | E | Elev | LPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGG1 | 18.01.2018 | Vayots Dzor | Artavan | Gray wolf (Canis lupus) | 39°39′27″ | 45°37′00″ | 1880m | 0 |

| GGG2 | 26.01.2018 | Vayots Dzor | Artavan | Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) | 39°39′27″ | 45°37′00″ | 1880m | 1 |

| GGG3 | 05.12.2017 | Hadrut | Hadrut | Wild boar (Sus scrofa) | 39°31′00″ | 47°01′48″ | 720m | 0 |

| GGG4 | 10.12.2017 | Vayots Dzor | Noravan k | Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) | 39°41’06” | 45°13’59” | 1550m | 0 |

| MA026 | 10.01.2018 | Syunik | Kajaran | Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) | 39°08’40” | 46°08’30” | 2051m | 26 |

The sampling followed the ethical rules in force in the country and has been approved by the Yerevan State University.

Each sample size was different (25–100g), however, a minimum of 25 g was collected on carcasses. The samples were kept frozen at −20 °C until their analysis.

Artificial digestion of muscle samples

After thawing, samples were mixed in a blender at 7000 rpm during 2 seconds. The magnetic stirrer method was then used for the artificial digestion of the mixed muscles using the European Union reference method (6). The larvae were counted in a gridded petri dish under a binocular magnifying glass.

DNA extraction, PCR, electrophoresis

The DNA of five pooled larvae per sample was extracted using the DNA IQ System Kit (PROMEGA, DC6701) and the Tissue and Hair Extraction Kit (PROMEGA, DC6740) (7).

A multiplex PCR using the GoTaq® Hot Start Green MasterMix (PROMEGA, M5122) was performed according to published protocol (7,8). Five primer pairs were used in a multiplex PCR (7). Primer set I, ESV target locus, 5′-GTTCCATGTGAACAGCAGT-3′, 5′-CGAAAACATACGACAACTGC-3′; primer set II, ITS1 target locus, 5′-GCTACATCCTTTTGATCTGTT-3′, 5′-AGACACAATA TCAACCACAGTACA-3′; primer set III, ITS1 target locus 5′-GCGGAAGGATCATTATCGTGTA-3′, 5′-TGGATTACAAAGAAAACCATCACT-3′; primer set IV, ITS2 target locus 5′-GTGAGCGTAATAAAGGTGCAG-3′, 5′-TTCATCACACATCTTCCACTA-3′; and primer set V, ITS2 target locus 5′-CAATTGAAAACCGCTTAGCGTGTTT-3′, 5′-TGATCTGAGGTCGACATTTCC-3′.

The PCR cycles were performed as follows: a pre-denaturation and polymerase activation step at 95 °C for 2 min, then 35 amplification cycles (denaturation at 95 °C for 10 sec, hybridization at 55 °C for 30 sec and elongation at 72 °C for 30 sec), and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 5 min.

For the PCR positive controls, muscle larvae from OF-1 female mice infected by T. spiralis, T. britovi, T. pseudospiralis or T. nativa were used.

Agarose (Ozyme, LON50004) gels (2%) were prepared in TAE (2M Tris-acetate, 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.3) (Lonza, BE51216) solution with 5 ng/mL of ethidium bromide (Sigma, E1510). Electrophoresis was performed using 10 μL of PCR products with 100 pb O’Range Ruler DNA ladder (ThermoFisher Scientific, SM0653) for 30 min at 100 V.

Results

After the artificial digestion of lynx and fox muscles, a total of 936 larvae were found in 36 g (26 LPG) and 37 larvae in 37 g (1 LPG) respectively (Table 1).

The different columns represent: the Identification (ID) of the samples, the date of sampling, the species muscles, the State, the Locality, the North (N) and East (E) coordinates, and the Elevation (Elev) where sampling occurred; in the last column, the results are given in Larvae per Gram of muscle (LPG)

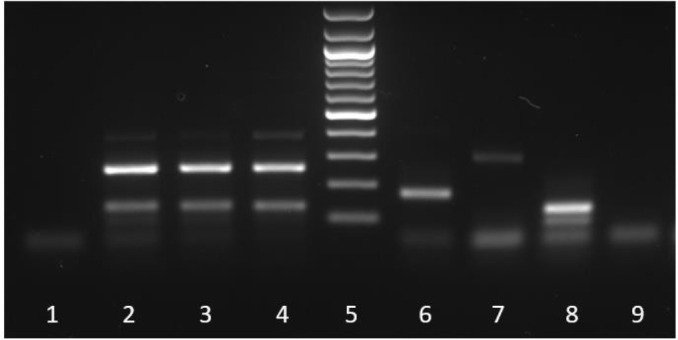

The DNA analysis showed that both isolates are Trichinella britovi (Fig. 1). This is the first record of T. britovi in Armenia.

Fig. 1:

Electrophoretic profiles of multiplex PCR amplification products

Multiplex PCR amplification products from PCR Negative Control (lane 1), DNA from T. britovi, T.spiralis, T. pseudospiralis and T. nativa Positive Controls (lane 2, 6, 7 and 8 respectively), from larvae found in Lynx muscles (lane3) and Red Fox Muscles (lane 4), and extraction Negative Control (lane 9). Lane 5=100 bp ladder

Discussion

Trichinella is a common infection in Caucasus region including Turkey, Iran, Georgia and Azerbaijan (5). However, this is the first finding of T. britovi in Armenia. Previously only T. spiralis or T. pseudospiralis were reported in 1980’s (4). T. britovi seems to be widespread in neighboring countries.

Several outbreaks of human trichinellosis have been reported in Turkey, Antalya province (9), Izmir province and in Bursa province, all due to consumption of meat infected by T. britovi (10,11). Additionally, in Turkey, T. spiralis was found in domestic and wild boars and in pork products.

T. britovi was also reported in leopard (Panthera pardus) and wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Iran (12,13). Both species are known to migrate between Iran and Armenia (14). In addition, T. britovi was reported from number of regions south of the Caspian Sea, including neighboring to Armenia regions of Azerbaijan (15).

Trichinella spp. was also reported in Georgia, particularly in stone martens, jackals, red foxes and corsac foxes, and domestic cats (16) and in pigs (17). In Azerbaijan, Trichinella spp infections were reported in wildlife (18,19) and T. britovi seems to be the etiological agent in domestic and sylvatic cycles (20). Unlike Armenia, the presence of T. britovi was reported in all countries surrounding Armenia. As mentioned above only T. spiralis and T, pseudospiralis were detected previously (4). In case of T. spiralis, this could be misidentification as to that time one species in the Trichinella genus was known. T. pseudospiralis was found in one common blackbird (Turdus Merula) (4). This is the only species infecting birds, so it is probably the second species circulating in the country.

Our study reports for the first time the presence of T. britovi in lynx and fox in Armenia. Further epidemiological investigations should be conducted on carnivorous species to better understand Trichinella spp distribution in wild-life within the country in order to evaluate the exposure of game meat consumers in Armenia.

Conclusion

It is the first time in Armenia T. britovi is reported. More research should be done to understand the current situation in Armenia, including human and wildlife.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to WWF-Armenia for providing samples and continuous support of the research. The field work was partly supported by the State Committee of Science, RA, in the frames of the research project № 16YR-1F077.

We also want to convince our gratitude to Galouste Gulbenkian foundation, for making this research possible with their financial support (research fellowship # 215935).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dupouy-Camet J. Trichinellosis: A worldwide zoonosis. Vet Parasitol. 2000; 93(3–4):191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottstein B, Pozio E, Nöckler K. Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control of trichinellosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009. 22(1): 127–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessonov AS. Trichinellosis (in Russian). M. - Kolos. 1976. 335 p.

- 4.Asatryan AM. Spread and specific composition of Trichinella in Armenia (in Russian). Acad Sci Armen SSR, Inst Zool Zool Pap. 1987; 21:34–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pozio E. World distribution of Trichinella spp. infections in animals and humans. Vet Parasitol. 2007; 149(1–2):3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Union. COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2015/1375 of 10 August 2015 laying down specific rules on official controls for Trichinella in meat (Codification). Official Journal of the European Union. 2015; 212:7–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karadjian G, Heckmann A, La Rosa G, et al. Molecular identification of Trichinella species by multiplex PCR: New insight for Trichinella murrelli. Parasite. 2017; 24:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zarlenga DS, Chute MB, Martin A, et al. A multiplex PCR for unequivocal differentiation of all encapsulated and non-encapsulated geno-types of Trichinella. International Journal for Parasitology. 1999. November; 29(11):1859–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pozio E, Darwin Murrell K. Systematics and Epidemiology of Trichinella. Adv Parasitol. 2006. 63: 367–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inci A, Doganay M, Ozdarendeli A, et al. Overview of Zoonotic Diseases in Turkey: The One Health Concept and Future Threats. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2018; 42(1):39–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altintas N. Parasitic zoonotic diseases in Turkey. Vet Ital. 2008; 44(4):633–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mowlavi G, Marucci G, Mobedi I, et al. Trichinella britovi in a leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor) in Iran. Veterinary Parasitology. 2009; 164(2–4):350–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rostami A, Khazan H, Kazemi B, et al. Prevalence of Trichinella spp. Infections in Hunted Wild Boars in Northern Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2017; 46(12):1712–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khorozyan IG, Abramov AV. The Leopard, Panthera pardus, (Carnivora:Felidae) and its resilience to human pressure in the Caucasus. Zoology in the Middle East. 2007; 41(1):11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shamsian A, Pozio E, Fata A, et al. The Golden jackal (Canis aureus) as an indicator animal for Trichinella britovi in Iran. Parasite. 2018; 25:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurashvili BE, Rodonaja TE, Matsaberidze GV, et al. Trichinellosis of animals in Georgia. Wiad Parazytol. 1970; 16(1):76–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potskhveria S, Ghlonty N. Trichinosis in Georgia. J Innov Med Biol. 2011; 4–5:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaikenov B, Boev SN. Distribution of Trichinella species in the Old World. Wiadomości Parazytol. 1983; 29(4–6):596–608. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadykhov IA. Helminths of fur-bearing animals of Azerbaidzhan. (Azerbaidzhani), Baku. (Original not seen.). 1962.

- 20.Pozio E. New patterns of Trichinella infection. Vet Parasitol. 2001; 98(1–3): 133–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]