Abstract

China faces the greatest challenge from stroke in the world. The death rate for cerebrovascular diseases in China was 149.49 per 100 000, accounting for 1.57 million deaths in 2018. It ranked third among the leading causes of death behind malignant tumours and heart disease. The age-standardised prevalence and incidence of stroke in 2013 were 1114.8 per 100 000 population and 246.8 per 100 000 person-years, respectively. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017, the years of life lost (YLLs) per 100 000 population for stroke increased by 14.6%; YLLs due to stroke rose from third highest among all causes in 1990 to the highest in 2017. The absolute numbers and rates per 100 000 population for all-age disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for stroke increased substantially between 1990 and 2017, and stroke was the leading cause of all-age DALYs in 2017. The main contributors to cerebrovascular diseases include behavioural risk factors (smoking and alcohol use) and pre-existing conditions (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and atrial fibrillation (AF)). The most prevalent risk factors among stroke survivors were hypertension (63.0%-84.2%) and smoking (31.7%-47.6%). The least prevalent was AF (2.7%-7.4%). The prevalences for major risk factors for stroke are high and most have increased over time. Based on the latest national epidemiological data, 26.6% of adults aged ≥15 years (307.6 million adults) smoked tobacco products. For those aged ≥18 years, age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension was 25.2%; adjusted prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia was 5.8%; and the standardised prevalence of diabetes was 10.9%. For those aged ≥40 years, the standardised prevalence of AF was 2.31%. Data from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System showed that 3 010 204 inpatients with stroke were admitted to 1853 tertiary care hospitals during 2018. Of those, 2 466 785 (81.9%) were ischaemic strokes (ISs); 447 609 (14.9%) were intracerebral haemorrhages (ICHs); and 95 810 (3.2%) were subarachnoid haemorrhages (SAHs). The average age of patients admitted was 66 years old, and nearly 60% were male. A total of 1555 (0.1%), 2774 (0.6%) and 1347 (1.4%) paediatric strokes (age <18 years) were identified among IS, ICH and SAH, respectively. Over one-third (1 063 892 (35.3%)) of the patients were covered by urban resident basic medical insurance, followed by urban employee basic medical insurance (699 513 (23.2%)) and new rural cooperative medical schema (489 361 (16.3%)). The leading risk factor was hypertension (67.4% for IS, 77.2% for ICH and 49.1% for SAH), and the leading comorbidity was pneumonia or pulmonary infection (10.1% for IS, 31.4% for ICH and 25.2% for SAH). In-hospital death/discharge against medical advice rate was 8.3% for stroke inpatients, ranging from 5.8% for IS to 19.5% for ICH. The median and IQR of length of stay was 10.0 (7.0–14.0) days, ranging from 10.0 (7.0–13.0) in IS to 14.0 (8.0–22.0) in SAH. Data from the Chinese Stroke Center Alliance demonstrated that the composite scores of guideline-recommended key performance indicators for patients with IS, ICH and SAH were 0.77±0.21, 0.72±0.28 and 0.59±0.32, respectively.

Keywords: stroke, statistics

Introduction

Stroke was the third highest cause of death in China, accounting for 1.57 million deaths in 2018.1 The 2016 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study estimated that China had the highest estimated lifetime risk of stroke from age 25 years onward of up to 39.3%.2 Stroke has imposed an enormous disease burden on the healthcare system in China. Tracking risk factors, clinical characteristics, management patterns and outcomes of patients with stroke will facilitate resource allocation and priority setting in healthcare system. The prevalences for major risk factors for stroke are high in the general population and among stroke survivors, and most have increased over time. National surveillance systems, such as mortality surveillance, nutrition and chronic disease surveillance, and tobacco surveillance can regularly assess changes in risk factors in the general population. In the past decades, several registry studies have been launched, including the China National Stroke Registries (CNSR-I, CNSR-II and CNSR-III).3–5 These registries provide timely evidence for clinical practice and scientific research.

In this report, we aim to use contemporary nationally representative data from surveillance systems, epidemiological surveys, administrative databases, registry databases and research projects6 to assess the prevalence and trends in community-based risk factors, clinical characteristics, management and outcomes of patients hospitalised in China. In addition, up-to-date evidence for healthcare resource allocation, planning and optimisation is provided.

Methods

This is a post hoc analysis based on information from multiple sources. We abstracted the most up-to-date data available to support the analyses in this report. Findings of stroke-related risk factors were extracted from published literature and surveillance reports. Patient demographic characteristics, comorbidities, procedures/operations and in-hospital outcomes were abstracted from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System (HQMS); in-hospital key performance indicators were abstracted from the Chinese Stroke Center Alliance (CSCA). The contents of this report have been internally and externally reviewed and approved by the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in Neurological Diseases.

Data sources

The National Mortality Surveillance System (NMSS) provides the total and cause-specific mortality by provinces and facilitates the development of a comprehensive real-time registration and mortality surveillance system. This system covered 24% of the Chinese population and has 605 points of surveillance. To ensure representation at the provincial level, these 605 surveillance points were selected to cover China’s 31 provinces using a multistage stratification method that accounted for sociodemographic characteristics of each region.1 ‘Province’ is hereafter referred to in this report to encompass provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in China.

The National Epidemiological Survey of Stroke in China (NESS-China) was conducted in 157 survey sites (64 urban and 93 rural sites) in China. A multistage stratified cluster-sampling method was applied. The study was designed as a door-to-door survey, and participants were people who had lived in that county or district for at least 6 months. The point-prevalence day was determined as 31 August 2013. The population-based incidence rates of stroke were estimated between 1 September 2012 and 31 August 2013. A total of 480 687 participants completed the survey, with an overall response rate of 81%.7

The China National Stroke Registry (CNSR) was a nationwide prospective registry for patients presented to hospitals with acute cerebrovascular events. CNSR-I was conducted between September 2007 and August 2008. A total of 132 study sites were selected, including 100 tertiary and 32 secondary urban hospitals in 27 provinces and four municipalities in Mainland China. A total of 21 902 patients aged ≥18 years were eligible and had complete information at baseline. Among the patients, 66.4% had IS.5

CNSR-II was launched during June 2012 to January 2013 and enrolled 219 hospitals. Among them, 72 hospitals participated in both CNSR-I and II, 59 sites only in CNSR-I and 147 hospitals only in CNSR-II. CNSR-II recruited 19 604 inpatients ≥18 years of age with acute IS.4

Between August 2015 and March 2018, CNSR-III recruited consecutive patients with IS or transient ischaemic attack from 201 hospitals that cover 22 provinces and four municipalities in China. A total of 15 166 patients with stroke were enrolled, among whom 93.3% had IS.3

The Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) used a global standardised methodology. In China, GATS was conducted in 2018 as a household survey of persons ≥15 years of age by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). A total of 24 370 households were sampled and one individual was randomly selected from each participating household to complete the survey. Survey information was collected electronically by using handheld devices. A total of 19 376 individuals completed the interview with an overall response rate of 91.5%.8

The Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance (CNHS) was a nationally representative cross-sectional study conducted by the China CDC to assess population health and nutrition status every 10 years. A stratified multistage cluster sampling was used. CNHS 2002 covered 132 surveillance sites consisting of 71 280 households and 252 912 subjects in 31 provinces.9

The first part of CNHS 2010–2013 was conducted during 2010 and 2012, randomly selecting 150 districts or counties within the 31 provinces and covering a total of 66 438 households. The second part of CNHS 2010–2013 was completed in children aged <6 years and lactating mothers in 55 surveillance sites. The final study sampled 36 878 children aged 0–5 years, 44 306 toddlers and adolescents aged 6–17 years, 157 850 non-pregnant adults ≥18 years of age and 4315 pregnant women.10

The Chinese Adults Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Surveillance (CANCDS) 2015 was a nationally and provincially representative surveillance study conducted by the China CDC. Multistage stratified cluster random sampling was used and based on the NMSS. CANCDS 2015 covered 302 surveillance sites in 31 provinces, and 179 728 participants provided data for the analysis of blood lipid levels.11

The China Patient-Centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events (PEACE) Million Persons Project was a population-based screening project conducted from 15 September 2014 to 20 June 2017. A convenience sampling strategy was used to select 141 sites (88 rural counties and 53 urban districts) from 31 provinces in Mainland China. Residents who were 35–75 years old and had lived in the selected regions for at least 6 of the previous 12 months were enrolled. The sample contained 1 738 886 participants with a mean age of 55.6 years and a majority (59.5%) were female.12

The China Chronic Disease and Risk Factors Surveillance (CDRFS) study is a nationwide cross-sectional study conducted every 3 years. The study was designed to measure the epidemiology of chronic disease and associated risk factors by selecting a nationally representative sample of the general population. In the 2010 survey, a total of 298 surveillance points were used in the 31 provinces. A total of 97 200 participants aged ≥18 years were enrolled in the survey. In the 2013 survey, a total of 179 347 participants were enrolled in the survey. The overall response rate was 93.4%.13

The China National Stroke Screening and Prevention Project (CNSSPP) is an ongoing community-based study that was conducted by the National Project Office of Stroke Prevention and Control. The CNSSPP used a two-stage stratified cluster sampling method. The cluster sampling method was used in every primary sampling unit, and all residents aged ≥40 years were surveyed during the primary screening. A total of 726 451 residents (386 975 women and 339 476 men) were included from October 2014 to November 2015.14

Data sources for epidemiology and risk factors of stroke are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiology of stroke and related risk factors and their data sources

| Indicators | Data sources | Survey year |

| Death rate of cerebrovascular disease | National Mortality Surveillance | 2018 |

| Prevalence and incidence rate of stroke | National Epidemiological Survey of Stroke | 2013 |

| Comorbidities in patients with ischaemic stroke | National Epidemiological Survey of Stroke China National Stroke Registry - I China National Stroke Registry - II China National Stroke Registry - III |

2013 2007–2008 2012–2013 2015–2018 |

| Tobacco use for adults (≥15 years of age) | China Global Adult Tobacco Survey | 2018 |

| Food and nutrition for adults (≥18 years of age) | Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance | 2002 2010–2012 |

| Overweight and obesity for adults (≥18 years of age) | Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance | 2002 2010–2012 |

| Hypertension and its awareness, treatment and control for adults (≥18 years of age) | Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance | 2002 2010–2012 |

| Hypertension and its awareness, treatment and control (35–75 years of age) | China Patient-Centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events (PEACE) Million Persons Project | 2014–2017 |

| Diabetes for adults (≥18 years of age) | China Chronic Disease and Risk Factors Surveillance | 2013 |

| Blood lipid and its screening, awareness and treatment for adults (≥18 years of age) | Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance Chinese Adults Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Surveillance |

2002 2010–2012 2015 |

| Atrial fibrillation for adults (≥40 years of age) | China National Stroke Screening and Prevention Project | 2014–2015 |

The Hospital Quality Monitoring System (HQMS) database is a mandatory national inpatient database system under the authority of the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. All tertiary care hospitals in China were required to submit standardised inpatient discharge records to HQMS. Patient data were collected from the nationally standardised front page of the hospital medical record. A total of 642 variables, including demographics of in-hospital patients, clinical diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), procedures and operations, costs, and information about affiliated hospitals or divisions were collected. The HQMS data reporting system performs automated data quality control on a daily basis at the time of data submission to ensure the completeness, consistency, and accuracy of data. If inconsistencies are detected, the entire daily data package of the hospital will be rejected and the hospital will be required to review and resubmit.15

The Chinese Stroke Center Alliance (CSCA) database is a national, hospital-based, voluntary, multifaceted intervention and continuous quality improvement initiative that provides a unique platform to develop stroke centres, improve stroke care quality and clinical outcomes. The CSCA was designed and led by a team of volunteers from the China Stroke Association under the guidance of the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in Neurological Diseases.6 Data were collected via the web-based patient data collection and management tool (Medicine Innovation Research Centre, Beijing, China), abstracted via chart review, coded, deidentified and transmitted in a secure manner in order to maintain patient confidentiality and to remain compliant with national privacy standards. The following data were collected for each hospitalisation: patient demographics, history of diseases and medications taken, hospital presentation, initial neurological status, medications and interventions during the hospital stay, reperfusion strategy, in-hospital outcomes and complications.6

Identification of diagnosis for stroke, comorbidities and procedures

Stroke diagnosis and comorbidities in HQMS were identified by main diagnosis using National Clinical V.2.0 of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, disease codes. Stroke diagnosis in CSCA was determined at discharge. Procedures or interventions were identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, Volume 3 (table 2).

Table 2.

ICD-10 disease code used for identification of patients with stroke and comorbidities and ICD-9-CM code used for identification of interventions or procedures

| Disease | ICD-10 |

| Stroke | |

| Ischaemic stroke | I63 |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage stroke | I61 |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage stroke | I60 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | I10 |

| Diabetes mellitus | E11.900 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | E78.500 |

| Atrial fibrillation | G91.900 |

| Coronary atherosclerotic heart disease | I25.103 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | I49.900 |

| Hyperuricaemia | E79.001 |

| Sequelae of cerebral infarction | I69.300 |

| Lacunar cerebral infarction | I63.801 |

| Encephalopathy | G31.902 |

| Cerebral hernia | G93.501 |

| Occlusion and stenosis of unspecified cerebral artery | I66.901 |

| Cerebral atherosclerosis | I67.200 |

| Pulmonary infection | J98.414 |

| Pneumonia | J18.900 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | J69.001 |

| Hydrothorax | J94.804 |

| Hypokalemia | E87.600 |

| Hypoproteinaemia | E77.801 |

| Fatty liver | K76.000 |

| Hyperplasia of prostate | N40.x00 |

| Procedures | |

| Intracranial artery thrombectomy | 39.7400×002, 39.7401,39.7400 |

| Carotid artery stenting | 0.63 |

| Vertebral artery balloon angioplasty | 00.6400×009 |

| Intracranial artery stenting/intracranial artery angioplasty | 0.6500 to 0.6200 |

| Vertebral artery stenting | 00.6102 |

| Middle cerebral artery stenting | 00.6501 |

| Evacuation of intracerebral haematoma/evacuation of intracranial haematoma/transtemporal evacuation of intracerebral haematoma | 01.3900×009, 01.2408, 01.3904 |

| Burr-hole drainage of ventricle/burr-hole decompression of skull | 01.3901,01.2414 |

| Stereotactic aspiration of intracranial haematoma/stereotactic puncture and drainage of intracranial haematoma/ hard tunnel puncture and drainage of intracranial haematoma | 01.3905, 01.3900×013, 01.3900×003 |

| Endoscopic drainage of haematoma | 01.3906 |

| Ventriculoperitoneal shunt/ventricoextracranial shunt | 02.3400×002, 02.3900 |

| Wrapping of intracranial aneurysm/resection of intracranial vascular malformation/clipping of carotid aneurysm | 39.5101 |

| Resection of intracranial aneurysm | 38.6100×002 |

| Neuroendoscopic clipping of intracranial aneurysm | 39.5100×004 |

| Clipping of posterior communicating artery aneurysm | 39.5104 |

| Clipping of anterior cerebral artery–anterior communicating artery aneurysm | 39.5107 |

| Clipping of middle cerebral artery aneurysm | 39.5103 |

| Clipping of cerebral aneurysm | 39.5100×007 |

| Clipping of aneurysm | 39.5100 |

| Interventions | |

| Intracranial aneurysm embolisation/intracranial aneurysm coil embolisation/intracranial aneurysm embolisation/middle cerebral aneurysm embolisation | 39.7203, 39.7204, 39.7209, 39.7200×006 |

| Intracranial artery stenting/intracranial artery stent-assist coil embolisation | 00.6500×008, 00.6500, 39.7205 |

| Intracranial and cervical artery occlusion | 39.7500 to 39.7200 |

| Carotid aneurysm embolisation | 39.7206 |

| Carotid aneurysm coil embolisation | 39.7207 |

| Internal carotid embolisation | 39.7200×004 |

| Carotid artery stenting | 00.6300 |

| Wrapping of intracranial aneurysm | 39.5201 |

| Clipping of intracranial vascular malformation | 38.8101 |

| Other arteriorrhaphy | 39.5200 |

| Clipping of anterior cerebral artery aneurysm | 39.5102 |

| Resection of intracranial vascular malformation | 38.6101 |

| Clipping of carotid aneurysm | 39.5101 |

| Resection of intracranial aneurysm | 38.6100×002 |

| Neuroendoscopic clipping of intracranial aneurysm | 39.5100×004 |

| Clipping of posterior communicating artery aneurysm | 39.5104 |

| Clipping of anterior cerebral artery–anterior communicating artery aneurysm | 39.5107 |

| Clipping of middle cerebral artery aneurysm | 39.5103 |

| Clipping of cerebral aneurysm | 39.5100×007 |

| Clipping of aneurysm | 39.5100 |

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Key performance indicators

A total of 11 guideline-recommended performance metrics of medication usage were prespecified for this study based on the national guidelines and the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke criteria. Detailed definitions are listed in table 3.

Table 3.

Specifications of guideline-recommended performance measures

| Performance measure of IS care | Performance measure definition for eligible patients* |

| Acute performance measures | |

| Intravenous rtPA <4.5 hours | Intravenous rtPA in patients who arrive within 3.5 hours after initial symptom onset and treated within 4.5 hours |

| Endovascular treatment <6 hours | Mechanical endovascular reperfusion therapy for acute IS caused by arterial occlusion of proximal anterior circulation within 6 hours after admission |

| Early antithrombotics | Antithrombotic therapy prescribed within 2 days of hospitalisation, including antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy |

| DVT prophylaxis | Patients at risk for DVT (non-ambulatory) who underwent DVT prophylaxis by the end of hospital day 2, including pneumatic compression, warfarin sodium, heparin sodium or new oral anticoagulants |

| Dysphagia screening | Dysphagia screening prior to any oral intake |

| Rehabilitation assessment | Assessed for stroke rehabilitation services |

| Performance measures at discharge | |

| Antithrombotic medication | Antithrombotic therapy prescribed at discharge |

| Anticoagulation for AF | Anticoagulation prescribed at discharge for patients with AF or atrial flutter documented during the hospitalisation |

| Antihypertensive medicines for patients with hypertension | Antihypertension medication prescribed at discharge for patients with history of hypertension disease or hypertension disease documented during the hospitalisation |

| Hypoglycaemic medication for diabetes mellitus | Hypoglycaemic medication prescribed at discharge for patients with history of diabetes mellitus or diabetes mellitus documented during the hospitalisation |

| Statin for lowering LDL≥100 mg/dL | Statin prescribed at discharge if LDL≥100 mg/dL, if patient treated with lipid-lowering agent prior to admission, or LDL not documented, hypoglycaemic medication for diabetes mellitus |

| Smoking cessation | Smoking cessation intervention (counselling or medication) prior to discharge for current or recent smokers |

| Stroke education | Stroke education provided to patient and/or caregiver, including all five components: modifiable risk factors, stroke warning sign and symptoms, how to activate emergency medical services, need for follow-up and medications prescribed |

*Eligible patients are those without any medical contraindications (eg, treatment intolerance, excessive risk of adverse reaction, patient/family refusal, or terminal illness/comfort care only) documented as reasons for non-treatment for each of the applicable measures. Acute performance measures, except for the rtPA measure, exclude patients who died before the end of day 2 of the hospital stay. Performance measures at discharge exclude patients who died during hospitalisation.

AF, atrial fibrillation; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; IS, ischaemic stroke; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; rtPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.

Statistical methods

Data were presented as means with SD or medians with IQRs for continuous variables and as frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. We did not report p values because large sample sizes in HQMS and CSCA would likely yield statistically significant p values with small absolute differences that may not be clinically meaningful. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4. To enhance the speed and efficiency of report creation and presentation, a SAS macro called %ggBaseline was used to analyse and report results automatically.16

Results

Stroke (cerebrovascular disease)

Mortality rate

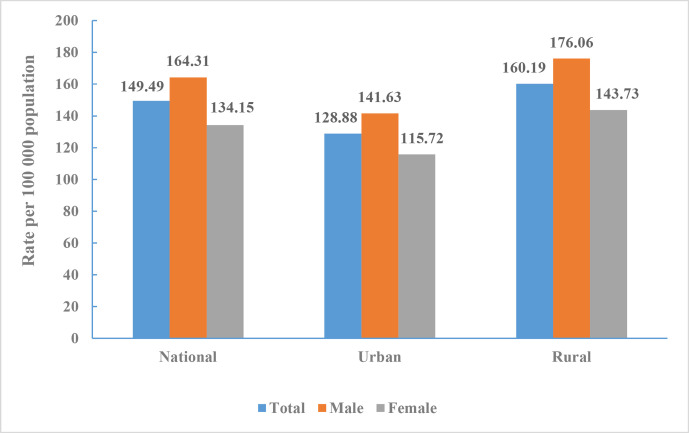

The death rate of cerebrovascular disease in China was 149.49 per 100 000 (1.57 million total) in 2018, accounting for 22.33% of all deaths. It ranked third among all causes of death behind malignant tumours (160.17 per 100 000) and heart disease (156.73 per 100 000).

The death rate of cerebrovascular disease in men was 164.31 per 100 000, ranking second behind malignant tumours (203.59 per 100 000). The death rate in women was 134.15 per 100 000, ranking second behind heart disease (152.74 per 100 000).

The death rate of cerebrovascular disease in urban and rural residents were 128.88 per 100 000 and 160.19 per 100 000, respectively, ranking third in cities and second in rural areas (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Crude mortality rate of cerebrovascular disease in Chinese residents by sex and region, National Mortality Surveillance System 2018.

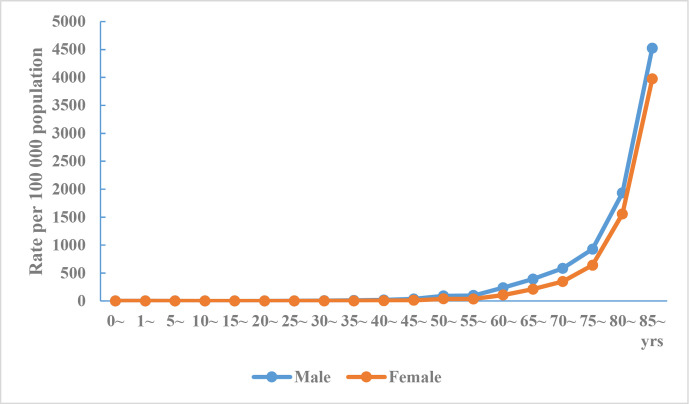

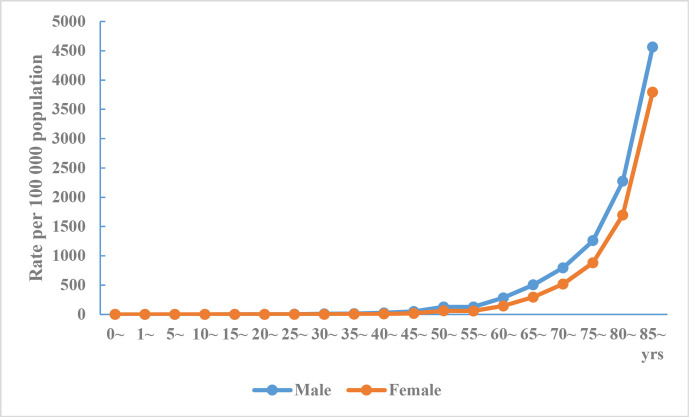

The death rate of cerebrovascular disease in urban and rural areas increases with age, and the death rate in men was higher than that in women for all age groups (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Crude mortality rate of cerebrovascular disease in Chinese urban residents by age and sex, National Mortality Surveillance System 2018.

Figure 3.

Crude mortality rate of cerebrovascular disease in Chinese rural residents by age and sex, National Mortality Surveillance System 2018.

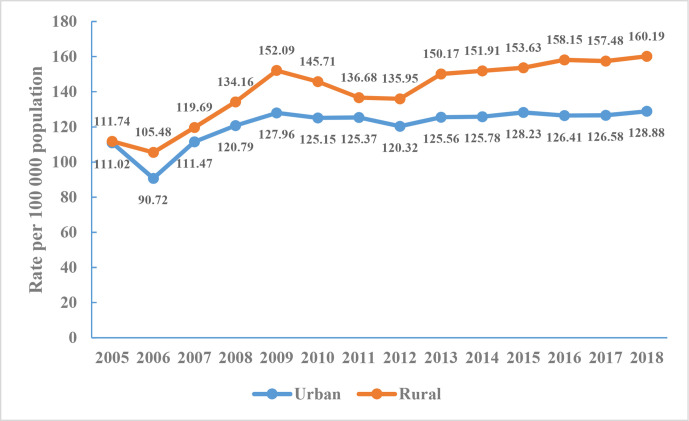

The annual crude mortality of cerebrovascular disease in rural areas was higher than that in urban areas from 2005 to 2018. Cerebrovascular disease mortality increased by 1.41 times in cities and 1.44 times in rural areas from 2006 to 2009. The crude death rate of cerebrovascular disease in 2009–2012 showed a downward trend but increased slightly during 2013–2018, and this change was observed to be more pronounced in rural areas (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Crude mortality rate of cerebrovascular disease in Chinese residents, National Mortality Surveillance System 2005–2018.

Prevalence and incidence

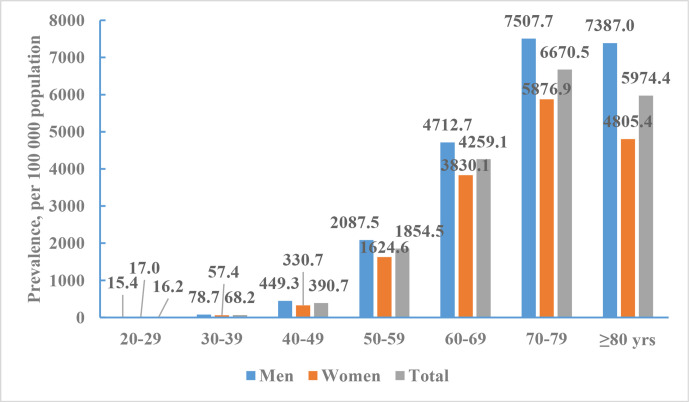

According the data from NESS-China 2013, 7672 out of 480 687 participants were diagnosed with a prevalent stroke. The mean age of participants with prevalent strokes was 66.4 years (66.2 years for men and 66.6 years for women). The crude prevalence of stroke was 1596.0/100 000. The age-standardised prevalence of stroke was 1114.8/100 000. The crude and age-standardised prevalence of stroke were 1768.7 /100 000 and 1222.2/100 000 for men, and 1426.2/100 000 and 1005.7/100 000 for women. The age-standardised prevalence of stroke did not differ significantly between men and women. The age-specific prevalence of stroke was markedly higher among men than among women across all age groups except for those aged 20–39 years. The age-specific prevalence of stroke increased with older age in both men and women, with a particularly marked increase in those aged ≥50 years (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Age-specific prevalence of stroke per 100 000 of Chinese adults by sex, National Epidemiological Survey of Stroke in China 2013.

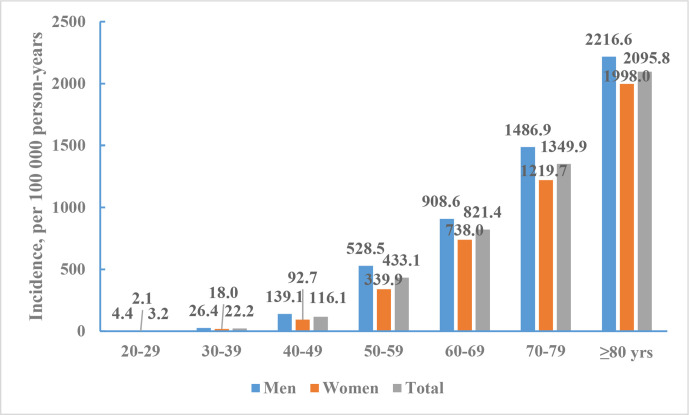

There were 1643 incident stroke cases (55.0% were men) identified between 1 September 2012 and 31 August 2013. The mean age of people with incident stroke was 66.4 years: 65.5 years in men and 67.6 years in women. The crude incidence of stroke was 345.1 per 100 000 person-years. The age-standardised incidence of stroke was 246.8 per 100 000 person-years. The crude and age-standardised incidence of stroke were 382.2 and 266.4 per 100 000 person-years for men, 308.5 and 226.9 per 100 000 person-years for women. There were no statistically significant sex differences in the age-standardised incidence rates. Stroke incidence in rural residents (298.2/100 000) was significantly greater than that in urban residents (203.6/100 000) (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Incidence rates of stroke per 100 000 person-years of Chinese adults (≥20 years) by sex, National Epidemiological Survey of Stroke in China 2013.

Disease burden

According to the data from NESS-China 2013, the years of life lost (YLLs) for stroke was 1748 per 100 000 people; the years lived with disability (YLDs) was 262 per 100 000 people; and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) was 2010 per 100 000 people. DALYs were 2171 per 100 000 for men and 1848 per 100 000 for women. The YLLs, YLDs and DALYs in rural areas were 1964/100 000, 294/100 000 and 2258/100 000, respectively. YLLs, YLDs and DALYs in urban areas were 1533/100 000, 229/100 000 and 1762/100 000, respectively.17

According to results from the GBD study 2017, YLLs per 100 000 population for stroke increased from 2298 in 1990 to 2633 in 2017, an increase of 14.6%. The age-standardised YLLs decreased by 38.8%, while YLLs due to stroke rose from the third highest among all causes in 1990 to the highest in 2017. The absolute numbers and rates per 100 000 population for all-age DALYs for stroke increased substantially between 1990 and 2017 (DALY counts increased by 46.8%, while the DALY rate increased by 24.4%), but age-standardised DALYs per 100 000 population decreased by 33.1% during this period. Stroke was the leading cause of all-age DALYs in 2017, replacing lower respiratory infections and neonatal disorders, which was the leading cause of all-age DALYs in 1990.18

Risk factors in stroke survivors

According to data from NESS-China 2013, the most prevalent risk factors in stroke survivors were hypertension (84.2%), smoking (47.6%) and alcohol use (43.9%). The least prevalent was AF (2.7%). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, AF and coronary heart disease (CHD) was significantly greater in women, but the prevalence of alcohol use and smoking was significantly greater in men. Although there was no significant difference in the prevalence of hypertension, alcohol use and smoking between urban and rural participants, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, AF and CHD were more prevalent among urban participants (table 4).

Table 4.

Prevalence of some risk factors in stroke survivors by sex and residency, National Epidemiological Survey of Stroke in China 2013

| Sex (%) | Urban and rural (%) | Total (%) | |||

| Men | Women | Urban | Rural | ||

| Hypertension | 83.71 | 84.89 | 84.42 | 84.09 | 84.24 |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 12.78 | 15.89 | 17.51 | 11.35 | 14.18 |

| Dyslipidaemia* | 20.63 | 23.18 | 27.08 | 17.26 | 21.78 |

| Atrial fibrillation* | 2.35 | 3.07 | 3.48 | 1.98 | 2.67 |

| Coronary heart disease* | 14.89 | 19.10 | 20.11 | 13.95 | 16.79 |

| Current smoker† | 72.28 | 17.54 | 46.91 | 48.24 | 47.63 |

| Alcohol drinking† | 65.66 | 17.42 | 44.45 | 43.51 | 43.94 |

*These risk factors were significantly different by sex and residency (p<0.05).

†These risk factors were significantly different between men and women (p<0.05).

We further analysed the prevalent risk factors in patients with IS by using data from CNSR. The final sample sizes of patients with IS were 12 173 in CNSR-I, 19 604 in CNSR-II and 13 982 in CNSR-III. Hypertension and current smoking were the risk factors with the high prevalences, and the prevalence of AF was the lowest (table 5).

Table 5.

Prevalence of risk factors in patients with ischaemic stroke, CNSRs I–III

| CNSR-I 2007–2008 (%) |

CNSR-II 2012–2013 (%) |

CNSR-III 2015–2018 (%) |

|

| Previous stroke/TIA | 34.1 | 35.6 | 23.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21.6 | 20.7 | 23.5 |

| Hypertension | 63.9 | 64.8 | 63.0 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 11.2 | 12.1 | 7.6 |

| CHD/previous MI | 14.5 | 13.5 | 10.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7.4 | 7.0 | 6.9 |

| Ever smoking | 39.8 | 44.2 | 31.7 |

CHD, coronary heart disease; CNSR, China National Stroke Registry; MI, myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Risk factors in general population

Health behaviours

Smoking/tobacco use

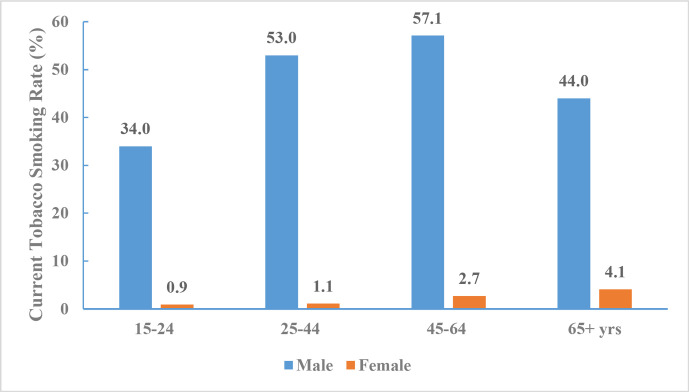

According to the China GATS 2018 data, among adults ≥15 years of age, 26.6% overall (307.6 million adults), 50.5% of men and 2.1% of women were current smokers. About 23.2% overall (268.9 million adults), 44.4% of men and 1.6% of women smoked tobacco on a daily basis.

Over half of the adults (216.9 million, 50.9%) who worked indoors were exposed to tobacco smoke at their workplace, and 44.9% (515.0 million) were exposed to tobacco smoke at home (table 6 and figure 7).

Table 6.

Prevalence of tobacco use for adults ≥15 years of age by sex, China Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2018

| Overall (%) | Men (%) | Women (%) | |

| Tobacco smokers | |||

| Current tobacco smokers | 26.6 | 50.5 | 2.1 |

| Daily tobacco smokers | 23.2 | 44.4 | 1.6 |

| Secondhand smoke | |||

| Adults exposed to tobacco smoke at the workplace* | 50.9 | 60.5 | 39.6 |

| Adults exposed to tobacco smoke at home† | 44.9 | 51.7 | 37.9 |

*Among those who work outside of the home who usually work indoors or both indoors and outdoors.

†Smoking occurs in the home at least monthly.

Figure 7.

Current tobacco smoking rate for adults aged 15 years and older by age and sex, China Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2018.

Food and nutrition

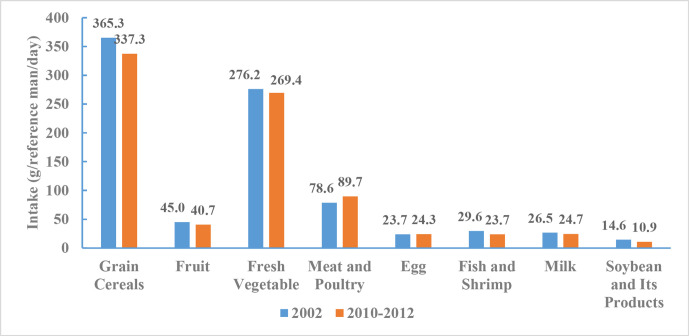

The average daily food consumption by Chinese adults, categorised by selected nutrients related to cardiometabolic health, was based on the data from CNHS 2002 and 2010–2012.

From 2010 to 2012, consumption of grain cereals per capita per day was 337.3 g, consisting of 177.7 g of rice, 142.8 g of flour and 16.8 g of other cereals. Grain cereal intake decreased slightly between 2002 and 2010–2012. Fruit and fresh vegetable consumption were 40.7 and 269.4 g per day, respectively, and remained stable between 2002 and 2010–2012. Consumption of meat and poultry was 89.7 g, consisting of 64.3 g of pork, 8.2 g of other livestock meat, 2.5 g of internal organs and 14.7 g of poultry meat. Average meat and poultry intake increased by 11.1 g between 2002 and 2010–2012. Consumption of other dairy and meat products included 24.3 g of eggs, 23.7 g of fish and shrimp, 24.7 g of milk, 10.9 g of soybean and other soy products. Milk intake remained at a low level from 2002 to 2010–2012, while consumption of fish and shrimp, and soybean and other soy products decreased by 5.9 and 3.7 g, respectively, and egg consumption remained stable between 2002 and 2010–2012 (figure 8).

Figure 8.

Comparison of Chinese adults’ food consumption, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012.

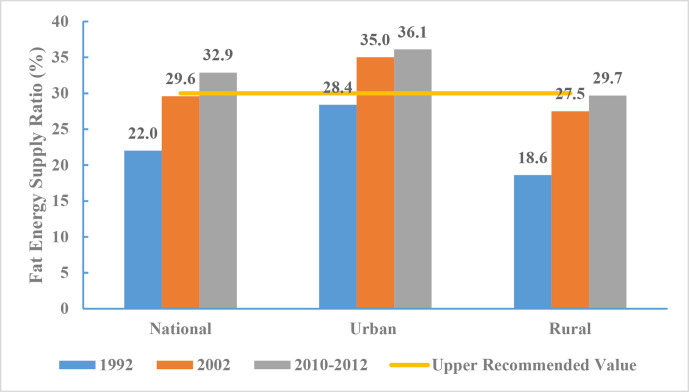

From 2010 to 2012, the proportion of fat-based energy for Chinese adults was 32.9% (36.1% in urban and 29.7% in rural areas). Data from CNHS 1992, 2002 and 2010-2012 indicated that the proportion of energy intake from fat increased over time. According to the Chinese Dietary Guidelines, the recommended upper limit for the proportion of fat-based energy intake is 30%. As such, fat-based energy intake among urban adults exceeded this limit by 6.1%, while that of rural adults approached but did not exceed the limit (figure 9).

Figure 9.

Proportion of fat-based energy for Chinese adults by region, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 1992, 2002 and 2010–2012.

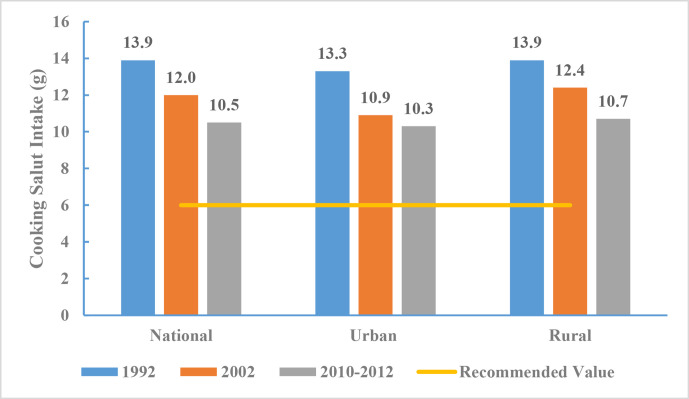

The average daily salt intake among Chinese adults ≥18 years of age was 10.5 g from 2010 to 2012, which is lower than 13.9 g in 1992 and 12.0 g in 2002. The recommended amount of daily salt intake as in Chinese Dietary Guidelines19 is 6 g. As such, the average intake among Chinese adults in 2012 was still 75.0% higher than the recommended value from 2010 to 2012 (figure 10).

Figure 10.

Salt intake for Chinese adults by region, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 1992, 2002 and 2010–2012.

Overweight and obesity

Classification of overweight and obesity

For adults (≥18 years of age), this was determined using Criteria of Weight for Adults (WS/T 428–2013).20 Being overweight was defined as having a body mass index (BMI) between 24.0 and 27.9 kg/m2. Obesity was defined as having a BMI of ≥28.0 kg/m2. We also used the standards recommended by the WHO21 that overweight is defined as 25.0 kg/m2 ≤BMI<30.0 kg/m2 and obesity was defined as BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2.

Prevalence

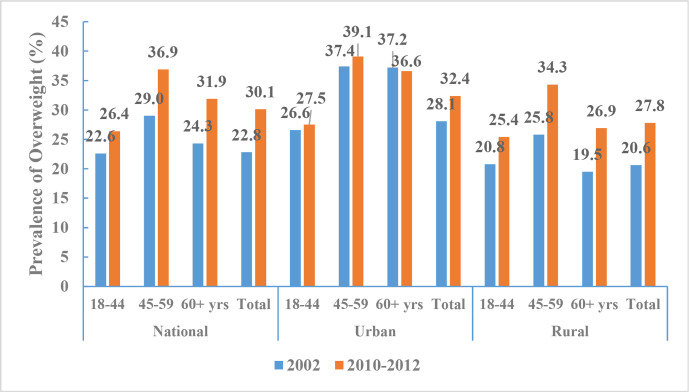

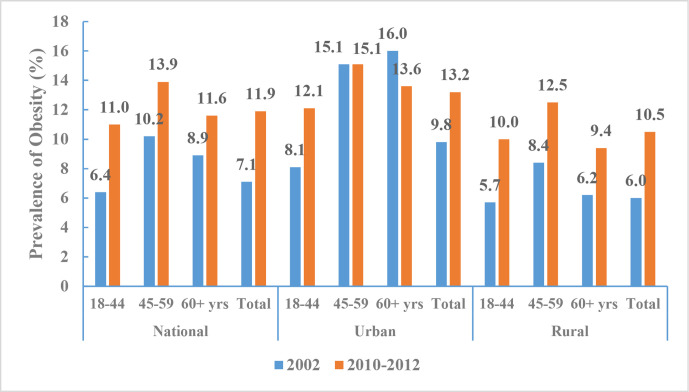

According to CNHS 2010–2012, the aged-adjusted prevalence of being overweight among Chinese adults (≥18 years of age) was 30.1% (30.3% of men and 29.9% of women, 32.4% in urban areas and 27.8% in rural areas), and the prevalence of obesity was 11.9% (12.1% of men and 11.7% of women, 13.2% in urban areas and 10.5% in rural areas). These BMI cut-offs for defining overweight and obesity are based on the Chinese standard. In contrast, the aged-adjusted prevalences of overweight or obesity were lower when defined according to the WHO standard (27.1% and 5.2%, respectively). The age-standardised prevalences of overweight or obesity increased significantly from 2002 to 2010–2012; using BMI definitions according to the Chinese standard, we found that the prevalence of overweight increased from 22.8% to 30.1% (figure 11) and the prevalence of obesity increased from 7.1% to 11.9% (figure 12).

Figure 11.

Prevalence of overweight among Chinese adults by regions and age groups, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012 (Chinese standard for body mass index).

Figure 12.

Prevalence of obesity among Chinese adults by regions and age groups, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012 (Chinese standard for body mass index).

High blood pressure

Definitions

Hypertension of adults (≥18 years of age) is defined as systolic blood pressure≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure≥90 mm Hg, or self-reported antihypertensive medicine use over the past 2 weeks.

Rate of hypertension awareness refers to the proportion of individuals having known hypertension (diagnosed by qualified medical institutions or doctors) and subsequently confirmed in the survey.

Rate of hypertension treatment refers to the proportion of individuals in the survey taking antihypertensive drugs over the past 2 weeks.

Rate of hypertension control refers to the proportion of individuals whose blood pressure was controlled to a level below 140/90 mm Hg after treatment.

Rate of hypertension treatment and control refers to the proportion of individuals whose blood pressure is controlled to a level <140/90 mm Hg among patients who have taken antihypertensive drugs over the past 2 weeks.

Prevalence

In 2002, the prevalence of hypertension was 18.8% among all Chinese adults and has increased since then. The age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension among Chinese adults ≥18 years of age was 25.2% in CNHS from 2010 to 2012 (26.2% for men and 24.1% for women, 26.8% for urban and 23.5% for rural) (table 7). This equates to an estimated 265.2 million adults who have high blood pressure (139.5 million men and 125.7 million women). Between 2010 and 2012, the prevalence of high blood pressure was 10.6% among those 18–44 years of age, 35.7% among those 45–59 years of age and 58.9% among those ≥60 years of age.

Table 7.

Prevalence of hypertension for adults ≥18 years of age by region and sex, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2010–2012

| National | Urban | Rural | |

| Total | 25.2 | 26.8 | 23.5 |

| Men | 26.2 | 28.1 | 24.2 |

| Women | 24.1 | 25.4 | 22.8 |

| 18–44 years | |||

| Subtotal | 10.6 | 11.3 | 10.0 |

| Men | 13.6 | 14.6 | 12.7 |

| Women | 7.3 | 7.6 | 6.9 |

| 45–59 years | |||

| Subtotal | 35.7 | 36.6 | 34.7 |

| Men | 35.9 | 37.9 | 33.6 |

| Women | 35.5 | 35.2 | 35.9 |

| 60+ years | |||

| Subtotal | 58.9 | 60.6 | 57.0 |

| Men | 56.5 | 57.6 | 55.3 |

| Women | 61.2 | 63.4 | 58.7 |

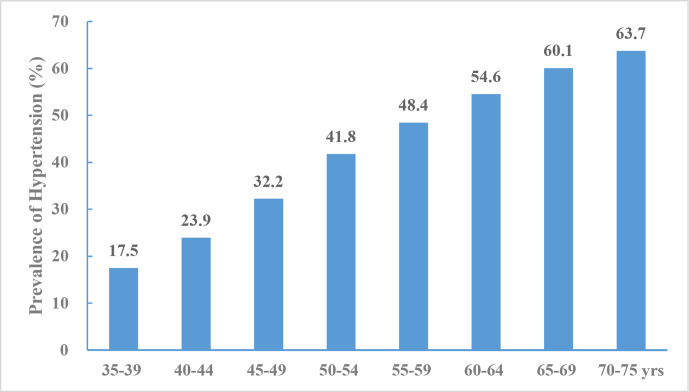

According to the data from China PEACE,12 44.7% of the study population had hypertension, including 15.2% with stage II hypertension. Hypertension prevalence increased with age (figure 13). The overall age-standardised and sex-standardised rate of hypertension prevalence was 37.2%.

Figure 13.

Prevalence of hypertension aged 35–75 years, China Patient-Centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events (PEACE) Million Persons Project 2014–2017.

Awareness, treatment and control

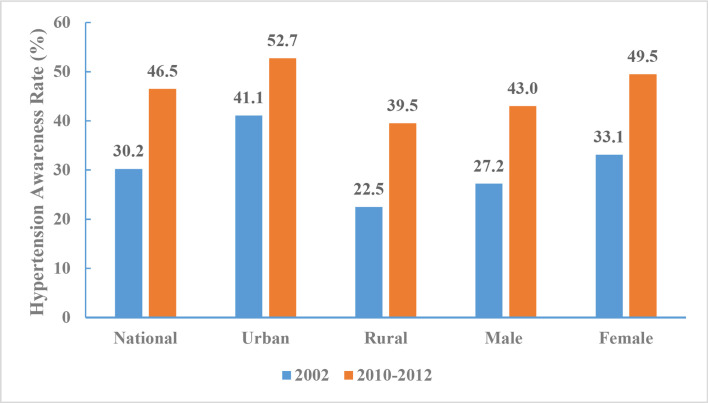

In 2010–2012, the rate of hypertension awareness among adults was 46.5% (43.0% for men and 49.5% for women). There was a significant difference in the awareness rate of hypertension among urban (52.7%) and rural (39.5%) adults. Analysis of CNHS 2002 and 2010–2012 found the proportion of adults aware of their hypertension increased within each subgroup by region and sex. The largest increase in the rate of hypertension awareness (17%) occurred among those living in rural areas (figure 14).

Figure 14.

Hypertension awareness rate of Chinese adults aged 18 years and above by region and sex, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012.

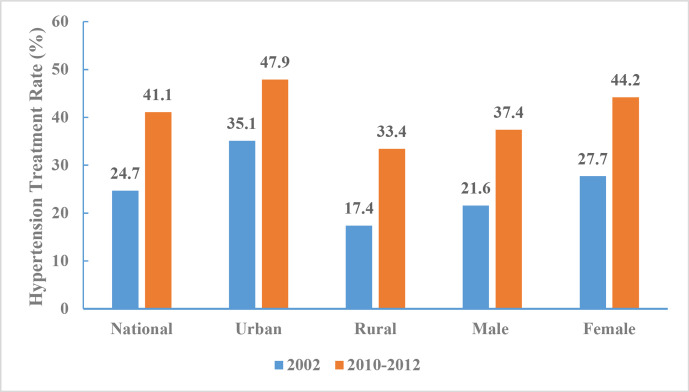

In 2010–2012, the rate of hypertension treatment among adults was 41.1% (37.4% for men and 44.2% for women). There was a significant difference in the treatment rate of hypertension among urban (47.9%) and rural (33.4%) adults, and the proportion of adults treated increased within each subgroup by region and sex. The largest increase in the rate of treatment (16.5%) occurred among women (figure 15).

Figure 15.

Hypertension treatment rate of Chinese adults aged 18 years and above by region and sex, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012.

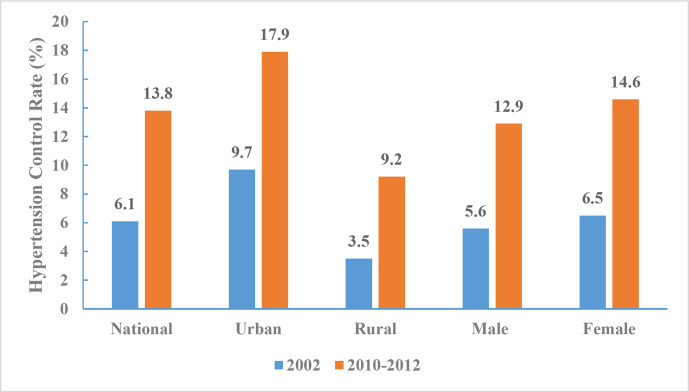

In 2010–2012, the hypertension control rate among Chinese adults ≥18 years was 13.8% (12.9% for men and 14.6% for women). Significant differences in the rate of control was observed between urban (17.9%) and rural (9.2%) adults, and the control rate increased within each subgroup by region and sex. Similar to trends observed in hypertension treatment rate, the largest increase in control rate (8.1%) was also among women (figure 16).

Figure 16.

Hypertension control rates for Chinese adults aged 18 years and above by region and sex, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012.

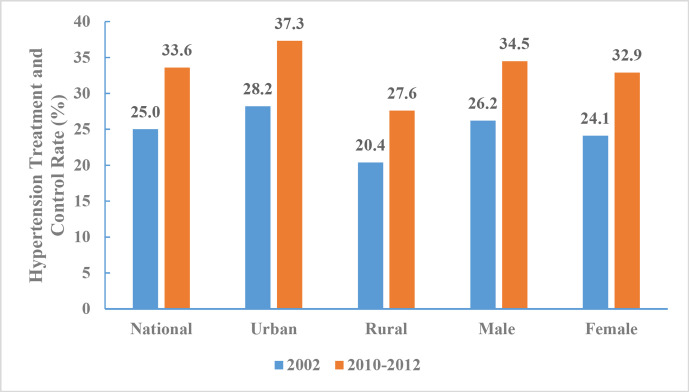

From 2010 to 2012, the rate of hypertension treatment and control among Chinese adults aged 18 years and above was 33.6% (34.5% for men and 32.9% for women). A significant difference was observed between urban (37.3%) and rural (27.6%) adults, and the proportion with controlled hypertension increased within each subgroup by region and sex. The largest increase (9.1%) occurred in urban areas (figure 17).

Figure 17.

Hypertension treatment and control rates for Chinese adults aged 18 years and above by region and sex, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012.

According to the data from China PEACE,12 44.7% participants were aware of their diagnosis; 30.1% were taking prescribed antihypertensive medications; and 7.2% had achieved control. The age-standardised and sex-standardised rates of hypertension awareness, treatment and control were 36.0%, 22.9% and 5.7%, respectively.

Diabetes mellitus

Definitions

Diagnosed diabetes is defined as self-reported but previously diagnosed by a healthcare professional. If no self-reported diagnosis exists, undiagnosed diabetes is defined according to the American Diabetes Association 2010 criteria, which includes fasting plasma glucose level of ≥126 mg/dL, 2-hour plasma glucose level of ≥200 mg/dL (after 75 g glucose ingestion) or an Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of ≥6.5%. Total diabetes prevalence is calculated by combining diagnosed and undiagnosed cases.

Pre-diabetes is identified as those who have no diabetes but have an HbA1c level between 5.7% and 6.4%, fasting plasma glucose level between 100 and 125 mg/dL, or 2-hour plasma glucose level between 140 and 199 mg/dL.

Awareness rate is defined as the proportion of individuals with physician-diagnosed diabetes among all patients with diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes.

Treatment rate is defined as the proportion of individuals receiving diabetic treatment medications among all patients with diabetes.

Control rate is defined as the proportion of individuals with an HbA1c level of <7.0% among patients with diabetes who are taking diabetic treatment medications.

Prevalence

According to the data from China CDRFS 2013, the standardised prevalence of diabetes in Chinese adults was estimated at 10.9%, with 10.2% in women and 11.7% in men. The prevalence of diabetes was higher in older patients, men and urban residents. The estimated prevalence of pre-diabetes was 35.7%, with 35.0% in women and 36.4% in men. The prevalence of pre-diabetes was also higher in older patients.

Awareness, treatment and control

The diabetes awareness rate was 36.5% (39.8% for women, 33.5% for men). The treatment rate was 32.2% and the control rate was 49.2%. The awareness rate and treatment rate were higher in older, female and urban residents. The control rate was higher in younger and urban residents (table 8).

Table 8.

Weighted prevalence, awareness rate, treatment rate and control rate of diabetes among Chinese adults from China Chronic Disease and Risk Factors Surveillance in 2013

| Total diabetes | Pre-diabetes | Awareness of diabetes | Treatment of diabetes | Control of diabetes | |

| Overall | 10.9 | 35.7 | 36.5 | 32.2 | 49.2 |

| Age groups (years) | |||||

| <40 | 5.9 | 28.8 | 22.8 | 20.0 | 56.0 |

| 40–59 | 12.9 | 39.5 | 39.0 | 34.5 | 47.0 |

| ≥60 | 20.2 | 45.8 | 43.5 | 38.4 | 49.3 |

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 10.2 | 35.0 | 39.8 | 35.3 | 48.5 |

| Men | 11.7 | 36.4 | 33.5 | 29.5 | 49.9 |

| Location | |||||

| Urban | 12.6 | 34.3 | 43.1 | 38.4 | 53.3 |

| Rural | 9.5 | 37.0 | 29.1 | 25.2 | 42.3 |

High blood cholesterol and other lipids

Definitions

According to the guidelines of Chinese Adult Dyslipidaemia Prevention and Treatment (2016 revised edition),22 a serum total cholesterol concentration greater than 6.22 mmol/L (240 mg/dL) is considered hypercholesterolaemia; triglyceride greater than 2.26 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) is considered hypertriglyceridaemia; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) greater than 4.14 mmol/L (160 mg/dL) is considered high LDL-c; and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) lower than 1.04 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) is considered low HDL-c.

Prevalence

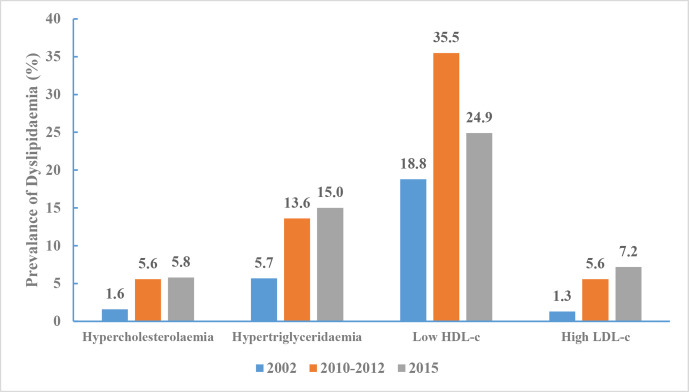

The adjusted prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia was 1.6% (95% CI 1.3% to 1.8%) in 2002, increased to 5.6% (95% CI 5.1% to 6.1%) in 2010 and then increased to 5.8% (95% CI 5.3% to 6.3%) in 2015 (p for trend <0.001). Hypertriglyceridaemia prevalence dramatically increased from 5.7% (95% CI 5.1% to 6.3%) to 13.6% (95% CI 12.9% to 14.2%) and then to 15.0% (95% CI 14.3% to 15.7%). Low HDL-c prevalence changed remarkably over these years, increasing from 18.8% (95% CI 17.0% to 20.6%) to 35.5% (95% CI 33.3% to 37.6%) and then to 24.9% (95% CI 23.5% to 26.4%). Similarly, high LDL-c prevalence increased from 1.3% to 5.6% and then to 7.2% over the 13-year interval (figure 18).

Figure 18.

Prevalence of dyslipidaemia in Chinese adults aged 18 years and above, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002, 2010–2012 and 2015.

Screening, awareness and treatment

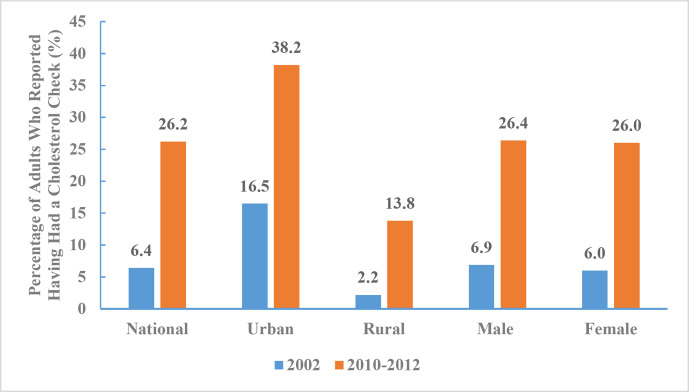

Between 2010 and 2012, the percentage of adults who reported having had a cholesterol check was 26.2% (26.4% for men and 26.0% for women, 38.2% in urban areas and 13.8% in rural areas). The percentages of adults who reported having had a cholesterol check by age group were 16.6% for those 18–44 years of age, 26.7% for those 45–59 years of age, and 35.3% for those 60 years of age and above. The percentage of adults who reported having had a cholesterol check increased from 6.4% to 26.2% between 2002 and 2010–2012 (figure 19).

Figure 19.

Percentage of adults who reported having had a cholesterol check by regions and sex, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012.

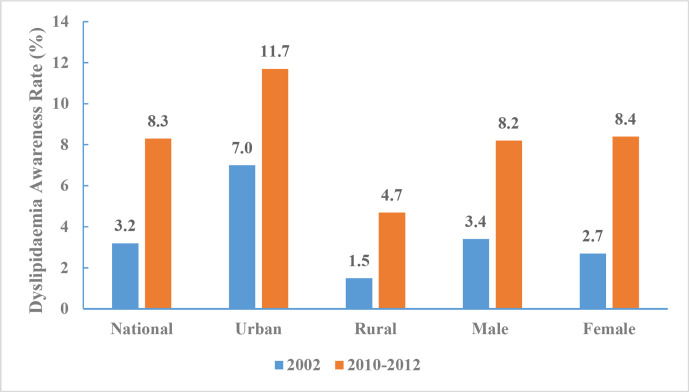

Between 2010 and 2012, dyslipidaemia awareness rate was 8.3% (8.2% for men and 8.4% for women, 11.7% in urban areas and 4.7% in rural areas). The dyslipidaemia awareness rate was 3.3% for those 18–44 years of age, 8.8% for those 45–59 years of age, and 12.4% for those 60 years and above. The dyslipidaemia awareness rate increased from 3.2% in 2002 to 8.3% during 2010–2012 (figure 20).

Figure 20.

Dyslipidaemia awareness rate of Chinese adults aged 18 years and above by region and sex, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012.

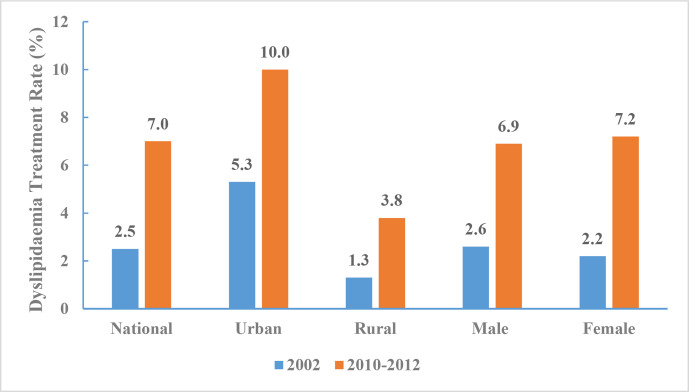

Between 2010 and 2012, dyslipidaemia treatment rate among Chinese adults ≥18 years of age was 7.0% (6.9% for men and 7.2% for women, 10.0% in urban areas and 3.8% in rural areas). The dyslipidaemia treatment rates by age group were 2.6% in for those between 18 and 44 years of age, 7.2% for those between 45 and 59 years of age, and 11.0% for those ≥60 years of age. Dyslipidaemia treatment rate increased from 2.5% in 2002 to 7.0% between 2010 and 2012 (figure 21).

Figure 21.

Dyslipidaemia treatment rate of Chinese adults aged 18 years and above by region and sex, Chinese Nutrition and Health Surveillance 2002 and 2010–2012.

Atrial fibrillation

Definitions

Individuals with AF is identified based on a self-reported history of persistent AF or identified based on results of previous ECG or ECG examinations during the survey.

Prevalence

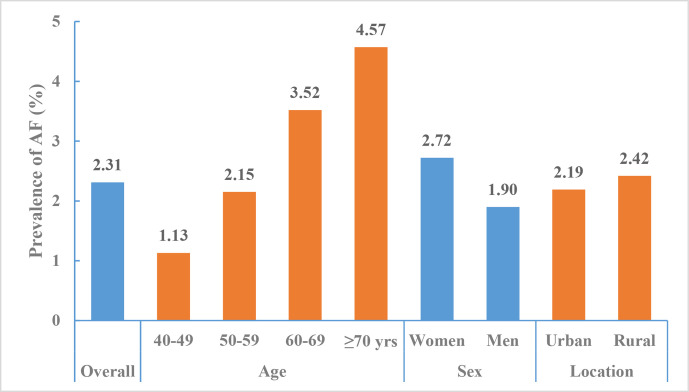

According to the data from the CNSSPP in all provinces other than Tibet from October 2014 to November 2015, the standardised prevalence of AF among Chinese adults aged ≥40 years was 2.31% (95% CI 2.28% to 2.33%). The prevalence increased with age, from 1.13% among adults aged between 40 and 49 years to 4.57% among adults aged ≥70 years. AF prevalence was higher among women compared with men (2.72% vs 1.90%) and higher among rural residents compared with urban residents (2.42% vs 2.19%)14 (figure 22).

Figure 22.

Prevalence of atrial fibrillation among adults aged ≥40 years by region and sex, China National Stroke Screening and Prevention Project 2014–2015.

Inpatient stroke care management and quality

Admission

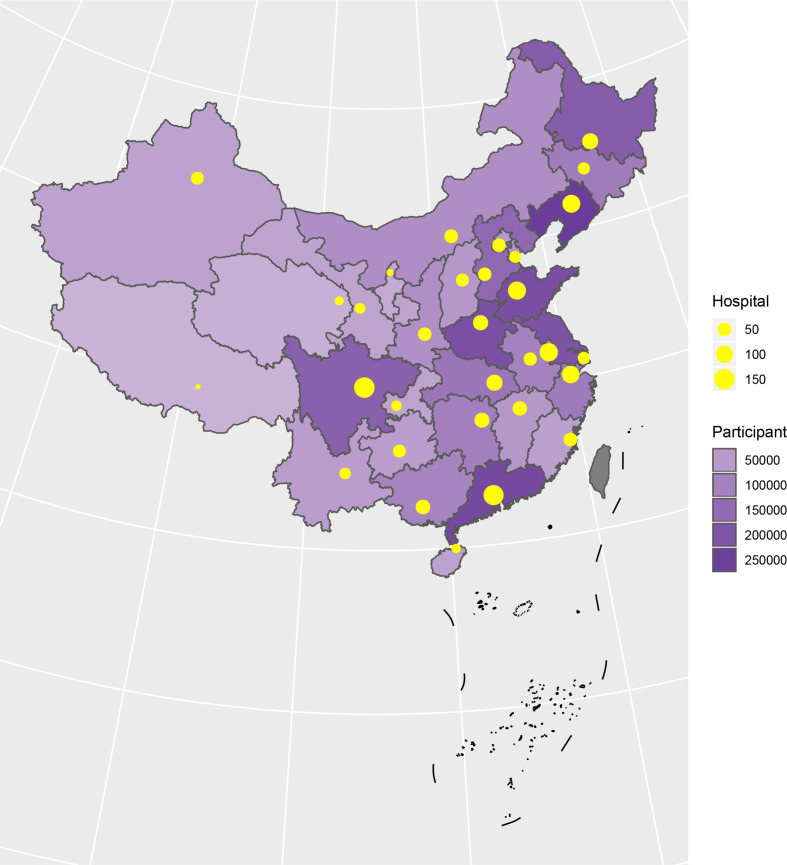

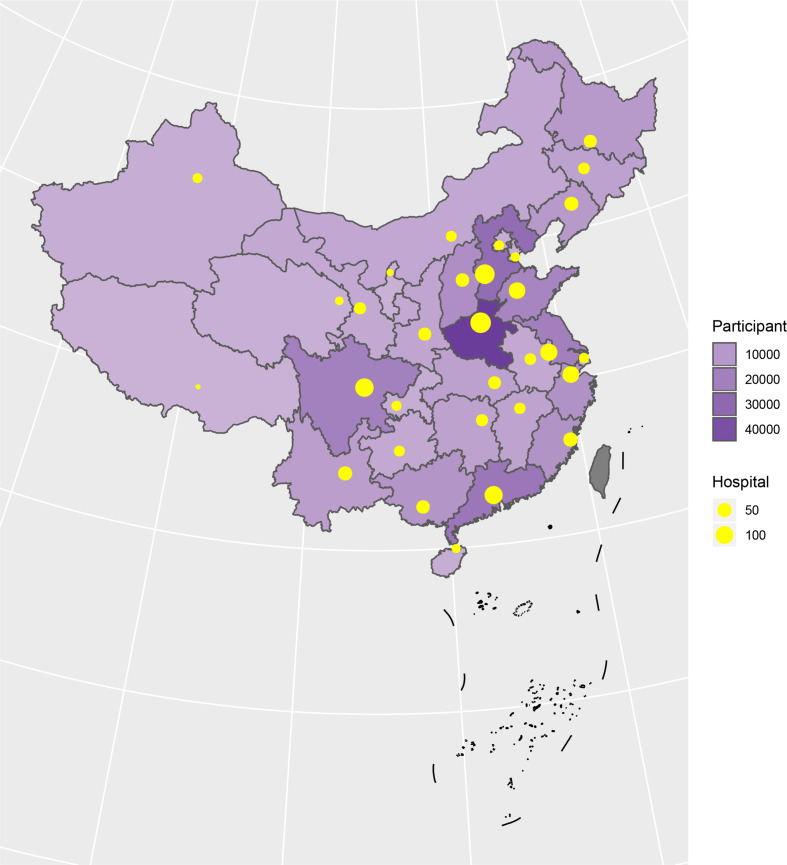

A total of 3 010 204 stroke patients admitted in 2018 were identified from HQMS among 1853 tertiary hospitals (figure 23). Of those, 2 466 785 (81.9%) were ISs, 447 609 (14.9%) were intracerebral haemorrhagic strokes, and 95 810 (3.2%) were subarachnoid haemorrhages (SAHs). Patients with IS were primarily admitted from the clinic (53.9%) and patients with intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) were primarily admitted from the emergency room (55.0% for ICH and 58.9% for SAH). All patients with stroke were more likely to be admitted on weekdays, especially on Mondays, and were less likely to be admitted on weekends (table 9).

Figure 23.

Distribution of hospitals and participants from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018.

Table 9.

Admission of in-patients with stroke from Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018

| Variables | Total (n=3 010 204 (100%)) |

IS (n=2 466 785 (81.9%)) |

ICH (n=447 609 (14.9%)) |

SAH (n=95 810 (3.2%)) |

| Admission | ||||

| Other | 362 176 (12.0) | 300 091 (12.2) | 52 145 (11.6) | 9940 (10.4) |

| Emergency | 1 113 395 (37.0) | 810 693 (32.9) | 246 281 (55.0) | 56 421 (58.9) |

| Clinic | 1 500 439 (49.8) | 1 330 705 (53.9) | 142 647 (31.9) | 27 087 (28.3) |

| Transfer | 34 194 (1.1) | 25 296 (1.0) | 6536 (1.5) | 2362 (2.5) |

| Admission day | ||||

| Monday | 524 402 (17.4) | 440 525 (17.9) | 69 340 (15.5) | 14 537 (15.2) |

| Tuesday | 470 785 (15.6) | 390 573 (15.8) | 66 097 (14.8) | 14 115 (14.7) |

| Wednesday | 452 805 (15.0) | 373 970 (15.2) | 64 876 (14.5) | 13 959 (14.6) |

| Thursday | 442 845 (14.7) | 364 341 (14.8) | 64 739 (14.5) | 13 765 (14.4) |

| Friday | 438 835 (14.6) | 359 499 (14.6) | 65 465 (14.6) | 13 871 (14.5) |

| Saturday | 352 261 (11.7) | 279 510 (11.3) | 59 667 (13.3) | 13 084 (13.7) |

| Sunday | 328 271 (10.9) | 258 367 (10.5) | 57 425 (12.8) | 12 479 (13.0) |

ICH, intracerebral haemorrhage; IS, ischaemic stroke; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Patients characteristics: sex, age and medical insurance

Among the 3 010 204 patients with stroke admitted to 1853 tertiary hospitals across China, nearly 60% were male. The average age was 66 (SD 12.8), and the median age was 67 (IQR 57.0–76.0). Most patients were covered by the urban resident basic medical insurance (URBMI) (35.3%), followed by the urban employee basic medical insurance (UEBMI) (23.2%) and new rural cooperative medical schema (NRCMS) (16.3%). Only 10.7% were self-pay (including off-site medical treatment of insured patients). For ISs and ICHs, a higher number of male patients were admitted compared with female patients. In contrast, more patients with SAH were female. Compared with other stroke subtypes, patients with SAH were younger and a higher proportion was self-pay (table 10).

Table 10.

Characteristics of in-patients with stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018

| Variables | Total (n=3 010 204(100%)) |

IS (n=2 466 785 (81.9%)) |

ICH (n=447 609 (14.9%)) |

SAH (n=95 810 (3.2%)) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 784 347 (59.3) | 1 460 467 (59.2) | 284 065 (63.5) | 39 815 (41.6) |

| Female | 1 225 857 (40.7) | 1 006 318 (40.8) | 163 544 (36.5) | 55 995 (58.4) |

| Age, mean±SD | 66.1±12.8 | 67.3±12.1 | 61.2±14.0 | 58.4±14.4 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 67.0 (57.0–76.0) | 68.0 (59.0–76.0) | 62.0 (52.0–71.0) | 59.0 (50.0–68.0) |

| Insurance | ||||

| URBMI | 1 063 892 (35.3) | 932 502 (37.8) | 110 358 (24.7) | 21 032 (22.0) |

| UEBMI | 699 513 (23.2) | 563 963 (22.9) | 112 805 (25.2) | 22 745 (23.7) |

| NRCMS | 489 361 (16.3) | 379 973 (15.4) | 89 838 (20.1) | 19 550 (20.4) |

| Self-pay | 321 318 (10.7) | 229 797 (9.3) | 72 984 (16.3) | 18 537 (19.3) |

| Other | 436 120 (14.5) | 360 550 (14.6) | 61 624 (13.8) | 13 946 (14.6) |

ICH, intracerebral haemorrhage; IS, ischaemic stroke; NRCMS, new rural cooperative medical schema; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage; UEBMI, urban employee basic medical insurance; URBMI, urban resident basic medical insurance.

Geographical distribution

Liaoning province contributed the largest number of patients for this report (8.4%), followed by Guangdong (7.6%) and Shandong (7.2%). Tibet contributed less than 1% (table 11).

Table 11.

Geographical distribution of in-patients with stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018

| Variables | Total (n=3 010 204 (100%)) |

IS (n=2 466 785 (81.9%)) |

ICH (n=447 609 (14.9%)) |

SAH (n=95 810 (3.2%)) |

| Geographical distribution | ||||

| Anhui | 103 116 (3.4) | 86 149 (3.5) | 14 101 (3.2) | 2866 (3.0) |

| Beijing | 53 003 (1.8) | 45 777 (1.9) | 5519 (1.2) | 1707 (1.8) |

| Fujian | 40 616 (1.3) | 30 512 (1.2) | 7752 (1.7) | 2352 (2.5) |

| Gansu | 32 806 (1.1) | 25 737 (1.0) | 6127 (1.4) | 942 (1.0) |

| Guangdong | 227 357 (7.6) | 187 282 (7.6) | 32 259 (7.2) | 7816 (8.2) |

| Guangxi | 97 243 (3.2) | 78 676 (3.2) | 15 314 (3.4) | 3253 (3.4) |

| Guizhou | 44 168 (1.5) | 31 717 (1.3) | 10 270 (2.3) | 2181 (2.3) |

| Hainan | 34 925 (1.2) | 31 484 (1.3) | 2944 (0.7) | 497 (0.5) |

| Hebei | 158 322 (5.3) | 132 826 (5.4) | 21 131 (4.7) | 4365 (4.6) |

| Henan | 213 814 (7.1) | 182 358 (7.4) | 25 650 (5.7) | 5806 (6.1) |

| Heilongjiang | 183 046 (6.1) | 163 356 (6.6) | 16 680 (3.7) | 3010 (3.1) |

| Hubei | 130 052 (4.3) | 102 556 (4.2) | 21 895 (4.9) | 5601 (5.8) |

| Hunan | 106 151 (3.5) | 80 124 (3.2) | 20 399 (4.6) | 5628 (5.9) |

| Jilin | 114 379 (3.8) | 97 868 (4.0) | 13 630 (3.0) | 2881 (3.0) |

| Jiangsu | 204 413 (6.8) | 166 696 (6.8) | 31 755 (7.1) | 5962 (6.2) |

| Jiangxi | 58 123 (1.9) | 42 650 (1.7) | 12 165 (2.7) | 3308 (3.5) |

| Liaoning | 254 149 (8.4) | 221 027 (9.0) | 28 139 (6.3) | 4983 (5.2) |

| Inner Mongolia | 76 376 (2.5) | 64 937 (2.6) | 9883 (2.2) | 1556 (1.6) |

| Ningxia | 16 661 (0.6) | 13 883 (0.6) | 2313 (0.5) | 465 (0.5) |

| Qinghai | 6898 (0.2) | 4472 (0.2) | 2127 (0.5) | 299 (0.3) |

| Shandong | 215 365 (7.2) | 179 071 (7.3) | 29 810 (6.7) | 6484 (6.8) |

| Shanxi | 57 230 (1.9) | 46 766 (1.9) | 8798 (2.0) | 1666 (1.7) |

| Shannxi | 74 292 (2.5) | 61 643 (2.5) | 10 799 (2.4) | 1850 (1.9) |

| Shanghai | 39 673 (1.3) | 32 697 (1.3) | 5582 (1.2) | 1394 (1.5) |

| Sichuan | 177 402 (5.9) | 131 854 (5.3) | 37 958 (8.5) | 7590 (7.9) |

| Tianjin | 58 340 (1.9) | 49 493 (2.0) | 7335 (1.6) | 1512 (1.6) |

| Tibet | 999 (0.0) | 411 (0.0) | 510 (0.1) | 78 (0.1) |

| Xingjian | 35 639 (1.2) | 27 244 (1.1) | 7195 (1.6) | 1200 (1.3) |

| Yunnan | 44 494 (1.5) | 32 298 (1.3) | 10 116 (2.3) | 2080 (2.2) |

| Zhejiang | 117 845 (3.9) | 91 224 (3.7) | 21 980 (4.9) | 4641 (4.8) |

| Chongqing | 33 307 (1.1) | 23 997 (1.0) | 7473 (1.7) | 1837 (1.9) |

ICH, intracerebral haemorrhage; IS, ischaemic stroke; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage.

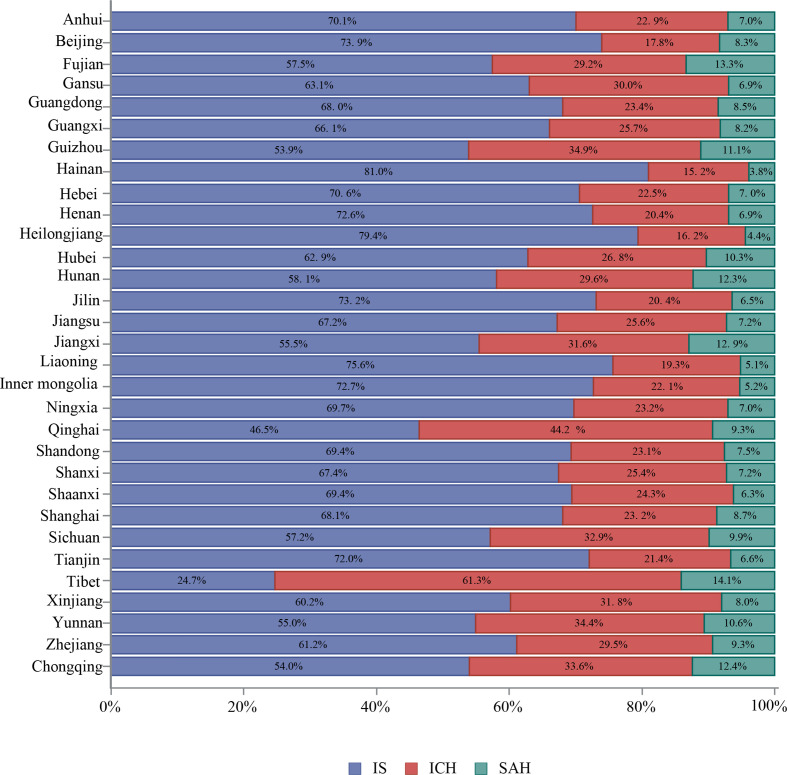

Stroke subtypes by geographical area

The proportion of each stroke subtype varied by province. Tibet had the highest proportion of ICH (61.3%), followed by Qinghai (44.2%) and Guizhou (34.9%) (figure 24).

Figure 24.

Proportion of stroke type for in-hospital patients with stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 stratified by province.

Age distribution stratified by sex and stroke subtype

The proportions of strokes occurring in those under 18 years of age were 0.1% for IS, 0.6% for ICH and 1.4% for SAH. Male patients had higher proportions of strokes occuring in each age groups under 65 years than female patients (tables 12–14).

Table 12.

Inpatients with ischaemic stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by age and sex

| Variables | Total (n=2 466 785 (100%)) |

Male (n=1 460 467 (59.2%)) |

Female (n=1 006 318 (40.8%)) |

| Age (years) | |||

| <18 | 1555 (0.1) | 936 (0.1) | 619 (0.1) |

| 18–24 | 1258 (0.1) | 757 (0.1) | 501 (0.0) |

| 25–29 | 3611 (0.1) | 2541 (0.2) | 1070 (0.1) |

| 30–34 | 8600 (0.3) | 6542 (0.4) | 2058 (0.2) |

| 35–39 | 18 521 (0.8) | 14 554 (1.0) | 3967 (0.4) |

| 40–44 | 42 521 (1.7) | 31 925 (2.2) | 10 596 (1.1) |

| 45–49 | 109 070 (4.4) | 77 032 (5.3) | 32 038 (3.2) |

| 50–54 | 197 522 (8.0) | 131 870 (9.0) | 65 652 (6.5) |

| 55–59 | 240 695 (9.8) | 158 180 (10.8) | 82 515 (8.2) |

| 60–64 | 357 504 (14.5) | 219 813 (15.1) | 137 691 (13.7) |

| 65–69 | 398 120 (16.1) | 229 912 (15.7) | 168 208 (16.7) |

| 70–74 | 350 936 (14.2) | 194 747 (13.3) | 156 189 (15.5) |

| 75–79 | 316 267 (12.8) | 168 082 (11.5) | 148 185 (14.7) |

| 80–84 | 246 343 (10.0) | 126 991 (8.7) | 119 352 (11.9) |

| 85+ | 174 262 (7.1) | 96 585 (6.6) | 77 677 (7.7) |

Table 13.

Inpatients with intracerebral haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by age and sex

| Variables | Total (n=447 609 (100%)) |

Male (n=284 065 (63.5%)) |

Female (n=163 544 (36.5%)) |

| Age (years) | |||

| <18 | 2774 (0.6) | 1617 (0.6) | 1157 (0.7) |

| 18–24 | 1710 (0.4) | 1100 (0.4) | 610 (0.4) |

| 25–29 | 2757 (0.6) | 1938 (0.7) | 819 (0.5) |

| 30–34 | 5712 (1.3) | 4364 (1.5) | 1348 (0.8) |

| 35–39 | 11 329 (2.5) | 9115 (3.2) | 2214 (1.4) |

| 40–44 | 20 670 (4.6) | 15 838 (5.6) | 4832 (3.0) |

| 45–49 | 41 279 (9.2) | 28 817 (10.1) | 12 462 (7.6) |

| 50–54 | 59 147 (13.2) | 37 494 (13.2) | 21 653 (13.2) |

| 55–59 | 51 790 (11.6) | 33 360 (11.7) | 18 430 (11.3) |

| 60–64 | 61 613 (13.8) | 39 562 (13.9) | 22 051 (13.5) |

| 65–69 | 61 129 (13.7) | 37 814 (13.3) | 23 315 (14.3) |

| 70–74 | 47 388 (10.6) | 28 423 (10.0) | 18 965 (11.6) |

| 75–79 | 37 221 (8.3) | 21 529 (7.6) | 15 692 (9.6) |

| 80–84 | 26 497 (5.9) | 14 541 (5.1) | 11 956 (7.3) |

| 85+ | 16 593 (3.7) | 8553 (3.0) | 8040 (4.9) |

Table 14.

In-patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by age and sex

| Variables | Total (n=95 810 (100%)) |

Male (n=39 815 (41.6%)) |

Female (n=55 995 (58.4%)) |

| Age (years) | |||

| <18 | 1347 (1.4) | 841 (2.1) | 506 (0.9) |

| 18–24 | 764 (0.8) | 500 (1.3) | 264 (0.5) |

| 25–29 | 1000 (1.0) | 637 (1.6) | 363 (0.6) |

| 30–34 | 1622 (1.7) | 1065 (2.7) | 557 (1.0) |

| 35–39 | 2625 (2.7) | 1534 (3.9) | 1091 (1.9) |

| 40–44 | 5123 (5.3) | 2690 (6.8) | 2433 (4.3) |

| 45–49 | 10 470 (10.9) | 4966 (12.5) | 5504 (9.8) |

| 50–54 | 13 883 (14.5) | 6199 (15.6) | 7684 (13.7) |

| 55–59 | 11 555 (12.1) | 5084 (12.8) | 6471 (11.6) |

| 60–64 | 14 586 (15.2) | 5715 (14.4) | 8871 (15.8) |

| 65–69 | 12 570 (13.1) | 4342 (10.9) | 8228 (14.7) |

| 70–74 | 8670 (9.0) | 2787 (7.0) | 5883 (10.5) |

| 75–79 | 5798 (6.1) | 1701 (4.3) | 4097 (7.3) |

| 80–84 | 3698 (3.9) | 1105 (2.8) | 2593 (4.6) |

| 85+ | 2099 (2.2) | 649 (1.6) | 1450 (2.6) |

Risk factors or comorbidities

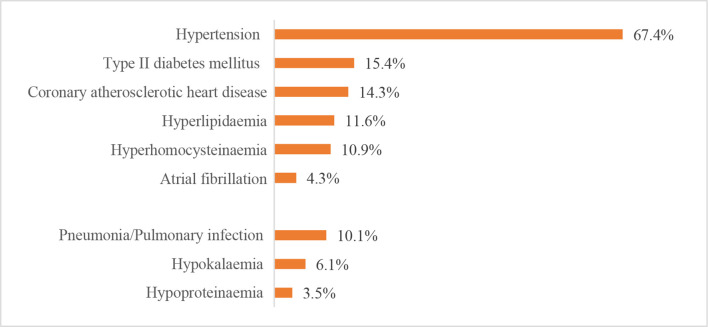

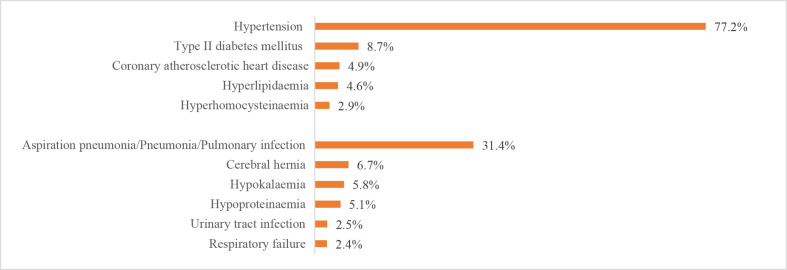

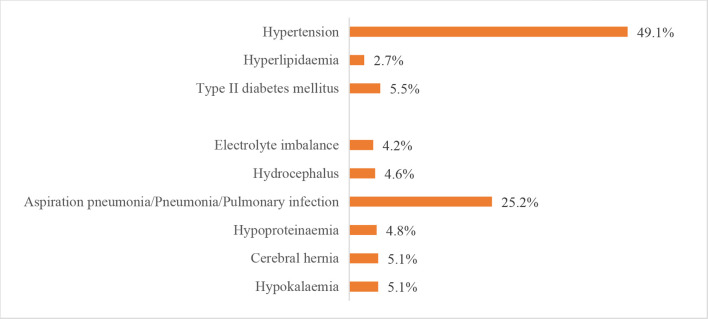

The leading risk factor for stroke was hypertension, which was present in 1 663 252 (67.4%) patients with IS, 345 572 (77.2%) patients with ICH and 47 008 (49.1%) patients with SAH. The leading comorbidity was pneumonia or pulmonary infection, which was present in 248 656 (10.1%) patients with IS, 140 338 (31.4%) patients with ICH and 24 111 (25.2%) patients with SAH. Other risk factors and comorbidities are shown in figures 25–27.

Figure 25.

Risk factors or comorbidities for patients with ischaemic stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018.

Figure 26.

Risk factors or comorbidities for patients with intracerebral haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018.

Figure 27.

Risk factors or comorbidities for patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018.

In-hospital management

We first assessed key performance indicators based on the national guidelines using the CSCA data from 2018. A total of 297 327 strokes (269 428 IS, 24 556 ICH and 3343 SAH) from 1377 hospitals were analysed (figure 28). The composite scores for patients with IS, ICH and SAH were 0.77±0.21, 0.72±0.28 and 0.59±0.32, respectively. The all-of-null measures for patients with IS, ICH and SAH were 27.1 (26.9–27.3), 37.3 (36.7–37.9) and 25.3 (23.9–26.8), respectively. Other indicators are shown in tables 15–17.

Figure 28.

Distribution of hospitals and participants from Chinese Stroke Center Alliance in 2018.

Table 15.

Key performance indicators of ischaemic stroke from Chinese Stroke Center Alliance in 2018

| Key performance indicators | Relative frequency | % (95% CI) |

| Acute performance measures | ||

| Intravenous rtPA≤4.5 hours | 16 270/67 122 | 24.2 (23.9% to 24.6%) |

| Early antithrombotics | 223 740/264 348 | 84.6 (84.5% to 84.8%) |

| DVT prophylaxis | 35 321/83 605 | 42.3 (41.9% to 42.6%) |

| Discharge performance measures | ||

| Antithrombotics | 229 080/261 594 | 87.6 (87.4% to 87.7%) |

| Anticoagulants for AF | 8448/19 283 | 43.8 (43.1% to 44.5%) |

| BP lowering for HTN | 130 477/202 912 | 64.3 (64.1% to 64.5%) |

| Glucose-lowering for hyperglycaemic | 59 039/75 330 | 78.4 (78.1% to 78.7%) |

| Statin for LDL | 238 145/266 767 | 89.3 (89.2% to 89.4%) |

| Additional quality measures | ||

| Smoking cessation | 61 221/63 630 | 96.2 (96.1% to 96.4%) |

| Dysphagia screen | 214 407/269 428 | 79.6 (79.4% to 79.7%) |

| Rehabilitation | 202 787/269 428 | 75.3 (75.1% to 75.4%) |

| Summary performance measures | ||

| Composite score | 0.77±0.21 | |

| All-or-none measure | 73 017/269 428 | 27.1 (26.9% to 27.3%) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; BP, blood pressure; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; HTN, hypertension; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; rtPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.

Table 16.

Key performance indicators of intracerebral haemorrhage from Chinese Stroke Center Alliance in 2018

| Key performance indicators | Relative frequency | % (95% CI) |

| DVT prophylaxis | 6938/14 902 | 46.6 (45.8% to 47.4%) |

| BP lowering for HTN | 17 505/20 748 | 84.4 (83.9% to 84.9%) |

| Smoking cessation | 4354/4640 | 93.8 (93.1% to 94.5%) |

| Dysphagia screen | 17 330/24 556 | 70.6 (70.0% to 71.1%) |

| Rehabilitation | 18 333/24 556 | 74.7 (74.1% to 75.2%) |

| Summary performance measures | ||

| Composite score | 0.72±0.28 | |

| All-or-none | 9149/24 556 | 37.3 (36.7% to 37.9%) |

BP, blood pressure; DVR, deep vein thrombosis; HTN, hypertension.

Table 17.

Key performance indicators of subarachnoid haemorrhage from Chinese Stroke Center Alliance in 2018

| Key performance indicators | Relative frequency | % (95% CI) |

| DVT prophylaxis | 752/1940 | 38.8 (36.6% to 40.9%) |

| BP lowering for HTN | 1391/1975 | 70.4 (68.4% to 72.4%) |

| Smoking cessation | 429/470 | 91.3 (88.7% to 93.8%) |

| Dysphagia screen | 1971/3343 | 59.0 (57.3% to 60.6%) |

| Rehabilitation | 1995/3343 | 59.7 (58.0% to 61.3%) |

| Summary performance measures | ||

| Composite score | 0.59±0.32 | |

| All-or-none | 847/3343 | 25.3 (23.9% to 26.8%) |

BP, blood pressure; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; HTN, hypertension.

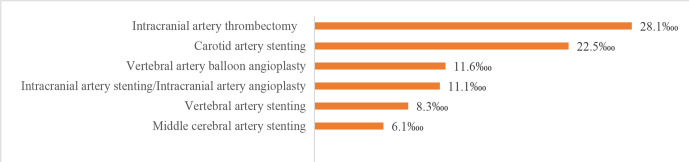

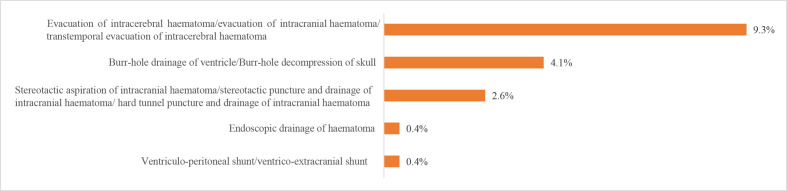

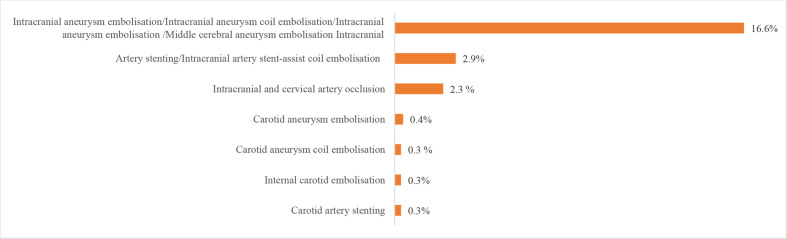

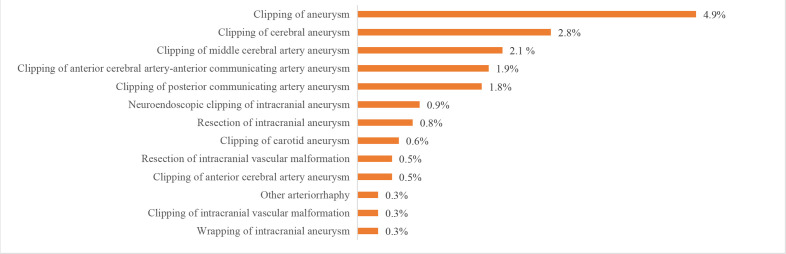

We also evaluated procedures and operations using the HQMS 2018 data. The most common procedures for patients with IS in HQMS were intracranial intra-arterial thrombectomy (6923 (28.1‱)) and carotid artery stenting (5540 (22.5‱)). The most common procedures for patients with ICH in HQMS were the evacuation of intracerebral haematoma/evacuation of intracranial haematoma/transtemporal evacuation of intracerebral haematoma (41 705 (9.3%)) and burr-hole drainage of ventricle/burr-hole decompression of skull (18 142 (4.1%)). For patients with SAH in HQMS, the most common interventions were intracranial aneurysm embolisation/intracranial aneurysm coil embolisation/intracranial aneurysm embolisation/middle cerebral aneurysm embolisation (15 895 (16.6%)) and intracranial arterial stenting/intracranial arterial stent-assist coil embolisation (2818 (2.9%)). The most common procedure for patients with SAH in HQMS was the clipping of aneurysms (4743 (4.9%)). Prevalence of other procedures and interventions are shown in figures 29–32.

Figure 29.

Procedures for patients with ischaemic stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018.

Figure 30.

Procedures for patients with intracerebral haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018.

Figure 31.

Intervention for patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018.

Figure 32.

Proceduresfor patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018.

In-hospital outcomes

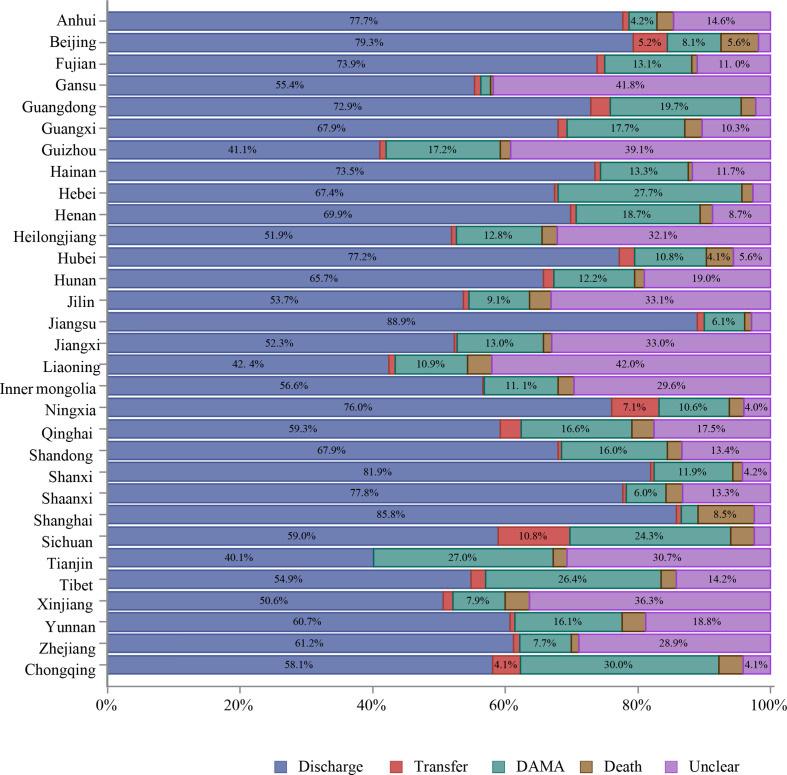

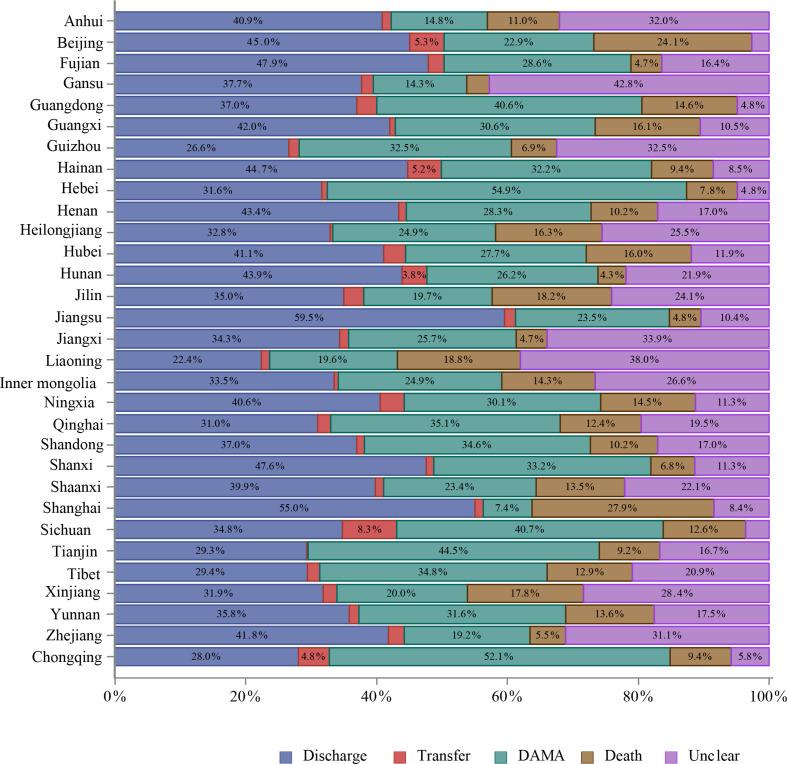

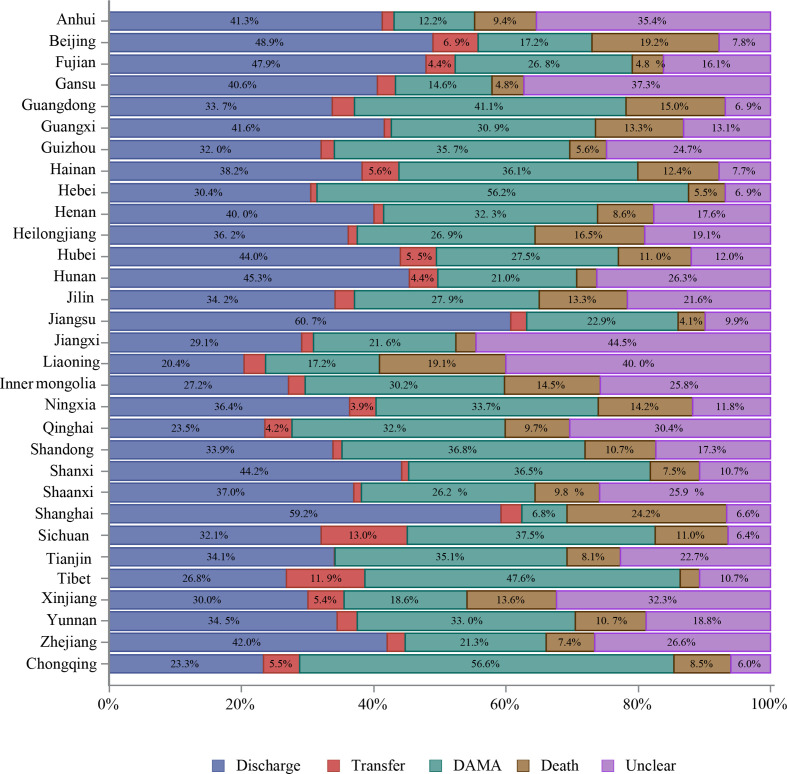

About 87% of hospitalised patients with stroke were discharged as planned. However, 8.3% were discharged against medical advice (DAMA) or died during hospitalisation. The mean length of stay was 12.4±10.5 days, with median and IQR at 10.0 (7.0–14.0) days. The average fee for the care of one patient with stroke was about 18 555 yuan (RMB), and average out-of-pocket spending was about 5765 yuan (RMB). More patients with ICH and SAH stroke were discharged against medical advice or died during hospitalisation and had higher total fees and out-of-pocket spending than those with IS (table 18).

Table 18.

In-hospital outcomes of patients with stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018

| Variables | Total (n=3 010 204 (100%)) |

IS (n=2 466 785(81.9%)) |

ICH (n=447 609(14.9%)) |

SAH (n=95 810 (3.2%)) |

| In-hospital outcomes | ||||

| Unclear | 94 651 (3.1) | 72 501 (2.9) | 18 145 (4.1) | 4005 (4.2) |

| Discharge | 2 629 861 (87.4) | 2 226 794 (90.3) | 332 929 (74.4) | 70 138 (73.2) |

| Transfer | 35 663 (1.2) | 23 510 (1.0) | 9025 (2.0) | 3128 (3.3) |

| DAMA/death | 250 029 (8.3) | 143 980 (5.8) | 87 510 (19.5) | 18 539 (19.4) |

| DAMA | 206 921 (6.9) | 125 930 (5.1) | 66 457 (14.8) | 14 534 (15.2) |

| Death | 43 108 (1.4) | 18 050 (0.7) | 21 053 (4.7) | 4005 (4.2) |

| Length of stay | ||||

| Mean±SD | 12.4±10.5 | 11.3±8.3 | 17.7±16.6 | 14.7±14.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 10.0 (7.0–14.0) | 10.0 (7.0–13.0) | 14.0 (8.0–22.0) | 12.0 (5.0–19.0) |

| Total fee | ||||

| Mean±SD | 18 555.2±29 893.9 | 13 675.7±18 167.6 | 34 071.1±44 760.2 | 71 696.4±75 216.5 |

| Median (IQR) | 10 213.5 (6547.5–17 271.9) | 9456.6 (6287.0–14 686.4) | 18 114.2 (9274.5–40 106.0) | 42 209.6 (11 739.6–116 403.0) |

| Out of pocket | ||||

| Mean±SD | 5765.0±16 395.9 | 4034.6±9848.3 | 10 980.4±25 195.7 | 25 951.4±48 698.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 1090.0 (0.0–5510.7) | 1004.7 (0.0–4826.2) | 1703.8 (0.0–11 007.8) | 2624.8 (0.0–29 138.7) |

DAMA, discharge against medical advice.

In-hospital outcomes were reported by sex. Female patients with stroke had lower cost of care for ischaemic stroke and ICH but higher cost of care for SAH compared with male patients with stroke (tables 19–21).

Table 19.

In-hospital outcomes of patients with ischaemic stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by sex

| Variables | Total (n=2 466 785 (100%)) |

Male (n=1 460 467 (59.2%)) |

Female (n=1 006 318(40.8%)) |

| In-hospital outcomes | |||

| Unclear | 72 501 (2.9) | 43 879 (3.0) | 28 622 (2.8) |

| Discharge | 2 226 794 (90.3) | 1 318 716 (90.3) | 908 078 (90.2) |

| Transfer | 23 510 (1.0) | 13 975 (1.0) | 9535 (0.9) |

| DAMA/death | 143 980 (5.8) | 83 897 (5.7) | 60 083 (6.0) |

| DAMA | 125 930 (5.1) | 73 438 (5.0) | 52 492 (5.2) |

| Death | 18 050 (0.7) | 10 459 (0.7) | 7591 (0.8) |

| Length of stay | |||

| Mean±SD | 11.3±8.3 | 11.5±8.5 | 11.0±8.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 10.0 (7.0–13.0) | 10.0 (7.0–14.0) | 10.0 (7.0–13.0) |

| Total fee | |||

| Mean±SD | 13 675.7±18 167.6 | 14 349.4±19 456.1 | 12 698.0±16 065.1 |

| Median (IQR) | 9456.6 (6287.0–14 686.4) | 9779.2 (6492.2–15 245.3) | 9007.7 (6017.5–13 881.0) |

| Out of pocket | |||

| Mean±SD | 4034.6±9848.3 | 4212.8±10 547.1 | 3775.9±8728.8 |

| Median (IQR) | 1004.7 (0.0–4826.2) | 958.0 (0.0–4928.7) | 1091.0 (0.0–4689.1) |

DAMA, discharge against medical advice.

Table 20.

In-hospital outcomes of patients with intracerebral haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by sex

| Variables | Total (n=447 609 (100%)) |

Male (n=284 065 (63.5%)) |

Female (n=163 544 (36.5%)) |

| In-hospital outcomes | |||

| Unclear | 18 145 (4.1) | 11 553 (4.1) | 6592 (4.0) |

| Discharge | 332 929 (74.4) | 210 151 (74.0) | 122 778 (75.1) |

| Transfer | 9025 (2.0) | 5854 (2.1) | 3171 (1.9) |

| DAMA/death | 87 510 (19.5) | 56 507 (19.9) | 31 003 (18.9) |

| DAMA | 66 457 (14.8) | 42 062 (14.8) | 24 395 (14.9) |

| Death | 21 053 (4.7) | 14 445 (5.1) | 6608 (4.0) |

| Length of stay | |||

| Mean±SD | 17.7±16.6 | 17.8±17.0 | 17.5±15.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 14.0 (8.0–22.0) | 14.0 (8.0–23.0) | 14.0 (8.0–22.0) |

| Total fee | |||

| Mean±SD | 34 071.1±44 760.2 | 35 262.9±46 808.4 | 32 001.0±40 877.5 |

| Median (IQR) | 18 114.2 (9274.5–40 106.0) | 18 317.1 (9295.0–41 467.4) | 17 792.3 (9233.7–37 890.9) |

| Out of pocket | |||

| Mean±SD | 10 980.4±25 195.7 | 11 329.7±26 102.7 | 10 373.6±23 525.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 1703.8 (0.0–11 007.8) | 1730.3 (0.0–11 178.3) | 1655.2 (0.0–10 753.5) |

DAMA, discharge against medical advice.

Table 21.

In-hospital outcomes of patients with subarachnoid haemorhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by sex

| Variables | Total (n=95 810 (100%)) |

Male (n=39 815 (41.6%)) |

Female (n=55 995 (58.4%)) |

| In-hospital outcomes | |||

| Unclear | 4005 (4.2) | 1679 (4.2) | 2326 (4.2) |

| Discharge | 70 138 (73.2) | 29 276 (73.5) | 40 862 (73.0) |

| Transfer | 3128 (3.3) | 1210 (3.0) | 1918 (3.4) |

| DAMA/death | 18 539 (19.4) | 7650 (19.2) | 10 889 (19.4) |

| DAMA | 14 534 (15.2) | 5897 (14.8) | 8637 (15.4) |

| Death | 4005 (4.2) | 1753 (4.4) | 2252 (4.0) |

| Length of stay | |||

| Mean±SD | 14.7±14.2 | 14.6±14.4 | 14.7±14.1 |

| Median (IQR) | 12.0 (5.0–19.0) | 12.0 (5.0–19.0) | 13.0 (5.0–19.0) |

| Total fee | |||

| Mean±SD | 71 696.4±75 216.5 | 66 809.2±74 334.4 | 75 171.4±75 646.3 |

| Median (IQR) | 42 209.6 (11 739.6–116403.0) | 33 721.9 (10 857.4–107 940.0) | 50 550.0 (12 483.0–122 352.5) |

| Out of pocket | |||

| Mean±SD | 25 951.4±48 698.2 | 24 607.7±47 861.6 | 26 906.9±49 262.6 |

| Median (IQR) | 2624.8 (0.0–29 138.7) | 2644.0 (0.0–25 907.8) | 2607.0 (0.0–32 100.0) |

DAMA, discharge against medical advice.

In-hospital outcomes were also reported by stroke subtypes and insurance status. Patients with stroke covered by URBMI had the lowest DAMA rate and the highest in-hospital death rate. Conversely, patients with stroke covered by NRCMS had the highest DAMA rate and the lowest in-hospital death rate. Other in-hospital outcomes such as length of stay, total fees and out-of-pocket spending are shown in tables 22–24.

Table 22.

In-hospital outcomes of patients with ischaemic stroke from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by insurance

| Variables | Total (n=2 466 785 (100%)) |

URBMI (n=932 502 (37.8%)) |

UEBMI (n=563 963 (22.9%)) |

NRCMS (n=379 973 (15.4%)) |

Self-pay (n=229 797 (9.3%)) |

Other (n=360 550 (14.6%)) |

| In-hospital outcomes | ||||||

| Unclear | 72 501 (2.9) | 18 386 (2.0) | 9292 (1.6) | 13 094 (3.4) | 5325 (2.3) | 26 404 (7.3) |

| Discharge | 2 226 794 (90.3) | 865 202 (92.8) | 511 609 (90.7) | 333 905 (87.9) | 205 733 (89.5) | 310 345 (86.1) |

| Transfer | 23 510 (1.0) | 7553 (0.8) | 6473 (1.1) | 4460 (1.2) | 1748 (0.8) | 3276 (0.9) |

| DAMA/death | 143 980 (5.8) | 41 361 (4.5) | 36 589 (6.5) | 28 514 (7.5) | 16 991 (7.3) | 20 525 (5.7) |

| DAMA | 125 930 (5.1) | 32 275 (3.5) | 33 708 (6.0) | 27 328 (7.2) | 14 815 (6.4) | 17 804 (4.9) |

| Death | 18 050 (0.7) | 9086 (1.0) | 2881 (0.5) | 1186 (0.3) | 2176 (0.9) | 2721 (0.8) |

| Length of stay | ||||||

| Mean±SD | 11.3±8.3 | 11.8±8.6 | 10.8±7.5 | 10.6±7.0 | 10.7±8.9 | 11.7±9.4 |

| Median (IQR) | 10.0 (7.0–13.0) | 10.0 (8.0–14.0) | 10.0 (7.0–13.0) | 10.0 (7.0–13.0) | 9.0 (6.0–13.0) | 10.0 (7.0–14.0) |

| Total fee | ||||||

| Mean±SD | 13 675.7±18 167.6 | 14 403.4±18 780.2 | 13 154.4±16 494.8 | 12 313.2±15 499.1 | 14 610.3±20 919.0 | 13 449.4±19 595.7 |

| Median (IQR) | 9456.6 (6287.0–14 686.4) | 10 029.5 (6851.6–15 320.8) | 9321.1 (6206.1–14 369.0) | 8662.2 (5791.2–13 360.8) | 9672.4 (5997.0–15 522.3) | 8863.7 (5676.5–14 327.4) |

| Out of pocket | ||||||

| Mean±SD | 4034.6±9848.3 | 3424.0±9100.7 | 3739.3±8158.1 | 4250.5±9046.3 | 6711.1±15 278.0 | 4142.2±10 223.8 |

| Median (IQR) | 1004.7 (0.0–4826.2) | 788.9 (0.0–3579.1) | 1136.1 (0.0–4892.0) | 1319.2 (0.0–5588.7) | 1538.2 (0.0–8757.3) | 1100.0 (0.0–5000.0) |

DAMA, discharge against medical advice; UEBMI, urban employee basic medical insurance; URBMI, urban resident basic medical insurance.

Table 23.

In-hospital outcomes of patients with intracerebral haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by insurance

| Variables | Total (n=447 609 (100%)) |

URBMI (n=110 358 (24.7%)) |

UEBMI (n=112 805 (25.2%)) |

NRCMS (n=89 838 (20.1%)) |

Self-pay (n=72 984 (16.3%)) |

Other (n=61 624 (13.8%)) |

| In-hospital outcomes | ||||||

| Unclear | 18 145 (4.1) | 3285 (3.0) | 3039 (2.7) | 4579 (5.1) | 3003 (4.1) | 4239 (6.9) |

| Discharge | 332 929 (74.4) | 84 996 (77.0) | 85 522 (75.8) | 66 474 (74.0) | 52 351 (71.7) | 43 586 (70.7) |

| Transfer | 9025 (2.0) | 2142 (1.9) | 2544 (2.3) | 1883 (2.1) | 1225 (1.7) | 1231 (2.0) |

| DAMA/death | 87 510 (19.5) | 19 935 (18.1) | 21 700 (19.2) | 16 902 (18.8) | 16 405 (22.5) | 12 568 (20.4) |

| DAMA | 66 457 (14.8) | 11 592 (10.5) | 18 045 (16.0) | 15 198 (16.9) | 12 325 (16.9) | 9297 (15.1) |

| Death | 21 053 (4.7) | 8343 (7.6) | 3655 (3.2) | 1704 (1.9) | 4080 (5.6) | 3271 (5.3) |

| Length of stay | ||||||

| Mean±SD | 17.7±16.6 | 19.8±18.4 | 17.5±15.7 | 16.9±15.2 | 15.4±15.6 | 17.9±17.4 |

| Median (IQR) | 14.0 (8.0–22.0) | 15.0 (9.0–24.0) | 14.0 (8.0–22.0) | 14.0 (7.0–22.0) | 12.0 (5.0–20.0) | 14.0 (7.0–23.0) |

| Total fee | ||||||

| Mean±SD | 34 071.1±44 760.2 | 39 562.8±52 449.2 | 31 952.4±40 252.5 | 30 908.3±38 416.6 | 32 816.8±42 964.6 | 34 211.1±47 366.7 |

| Median (IQR) | 18 114.2 (9274.5–40 106.0) | 20 319.9 (10 849.9–45 746.2) | 17 606.5 (9252.0–37 643.0) | 17 159.0 (8907.0–37 146.4) | 17 161.5 (7980.1–40 204.0) | 17 829.6 (8647.3–39 803.6) |

| Out of pocket | ||||||

| Mean±SD | 10 980.4±25 195.7 | 10 231.0±25 911.0 | 8594.7±19 318.0 | 10 993.7±23 503.0 | 15 571.7±31 361.6 | 11 232.4±26 814.8 |

| Median (IQR) | 1703.8 (0.0–11 007.8) | 1789.7 (0.0–9241.1) | 1133.2 (0.0–9336.3) | 2176.3 (0.0–11 605.0) | 2571.0 (0.0–16 693.1) | 1111.6 (0.0–11 165.2) |

DAMA, discharge against medical advice; UEBMI, urban employee basic medical insurance; URBMI, urban resident basic medical insurance.

Table 24.

In-hospital outcomes of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage from the Hospital Quality Monitoring System in 2018 by insurance

| Variables | Total (n=95 810 (100%)) |

URBMI (n=21 032 (22.0%)) |

UEBMI (n=22 745 (23.7%)) |

NRCMS (n=19 550 (20.4%)) |

Self-pay (n=18 537 (19.3%)) |

Other (n=13 946 (14.6%)) |

| In-hospital outcomes | ||||||

| Unclear | 4005 (4.2) | 682 (3.2) | 810 (3.6) | 991 (5.1) | 762 (4.1) | 760 (5.4) |

| Discharge | 70 138 (73.2) | 15 793 (75.1) | 16 554 (72.8) | 14 056 (71.9) | 13 541 (73.0) | 10 194 (73.1) |

| Transfer | 3128 (3.3) | 604 (2.9) | 790 (3.5) | 709 (3.6) | 532 (2.9) | 493 (3.5) |

| DAMA/death | 18 539 (19.4) | 3953 (18.8) | 4591 (20.1) | 3794 (19.4) | 3702 (20.0) | 2499 (17.9) |

| DAMA | 14 534 (15.2) | 2383 (11.3) | 3898 (17.1) | 3417 (17.5) | 2965 (16.0) | 1871 (13.4) |

| Death | 4005 (4.2) | 1570 (7.5) | 693 (3.0) | 377 (1.9) | 737 (4.0) | 628 (4.5) |

| Length of stay | ||||||

| Mean±SD | 14.7±14.2 | 16.3±15.9 | 15.2±14.0 | 14.0±13.1 | 12.7±13.0 | 14.7±14.6 |

| Median (IQR) | 12.0 (5.0–19.0) | 13.0 (7.0–21.0) | 13.0 (5.0–20.0) | 12.0 (5.0–19.0) | 10.0 (3.0–17.0) | 12.0 (5.0–19.0) |