Abstract

Objectives

In Italy the burden of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) gradually decreased from March to the end of May. In this work we aimed to evaluate a possible association between the severity of clinical manifestations and viral load over time during the epidemiological transition from high-to low-transmission settings.

Methods

We reviewed the cases of COVID-19 diagnosed at the emergency room of our hospital, retrieving the proportion of patients admitted to the intensive care unit. A raw estimation of the viral load was done evaluating the Ct (cycle threshold) trend obtained from our diagnostic reverse transcriptase real-time PCR test.

Results

The proportion of patients requiring intensive care significantly decreased from 6.7% (19/281) in March to 1.1% (1/86) in April, and to none in May (Fisher's test p 0.0067). As for viral load, we observed a trend of Ct increasing from a median value of 24 (IQR 19–29) to 34 (IQR 29–37) between March and May, with a statistically significant difference between March and April (pairwise Wilcoxon test with stepdown Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing, p 0.0003).

Conclusions

We observed a reduction over time in the proportion of patients with COVID-19 requiring intensive care, along with decreasing median values of viral load. As the epidemiological context changes from high-to low-transmission settings, people are presumably exposed to a lower viral load which has been previously associated with less severe clinical manifestations.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Viral load

Introduction

In Italy, the first case of local infection by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was diagnosed at the end of February 2020 [1]. Since then, cases increased rapidly, so that in March 2020 Italy was among the countries most severely hit by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [2]. Hospitals struggled with the exponential increase in patients with COVID-19 who needed admission to medical wards and intensive care units (ICUs) [3]. In response to this dramatic situation, the Italian government imposed lockdown measures, first to the provinces with the highest number of cases, then to the whole country (9th March 2020) [4]. The quarantine resulted in a gradual decrease in cases of COVID-19 [2]. Apparently, patients also presented with less severe clinical manifestations.

In this work, we aimed to explore a possible association between the severity of clinical manifestations and viral load over time during the epidemiological transition from high-to low-transmission settings.

Methods

We reviewed the number of patients with a final diagnosis of COVID-19 (based on the molecular test described below) performed at the emergency room of IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar, Verona, Northern Italy between 1st March and 31st May 2020. The number of patients admitted to the ICU was retrieved. The study (No. 39528/2020 Prog. 2832CESC) was approved by the competent Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Verona and Rovigo Provinces. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients, and all research was performed in accordance with European guidelines/regulations.

We performed a raw estimation of the viral load, evaluating the Ct (cycle threshold) trend obtained from our diagnostic reverse transcriptase real-time PCR (RT-PCR) test. Our in-house diagnostic protocol, performed on nasal/pharyngeal swabs, was standardized following the WHO guidelines [5], and the RT-PCR was cross-validated with the regional reference laboratory (Department of Microbiology, University Hospital of Padua). We performed viral RNA extraction from nasal/pharyngeal swabs by an automated method (Magnapure LC RNA isolation kit—high performance, Roche). For the RT-PCR test, we applied either the protocol published by Corman et al. [6] or by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (https://www.fda.gov/media/134922/download). The use of these two different RT-PCR assays was imposed on us by the lack of reagents during the worldwide emergency. Thus, we evaluated for this purpose the Ct variability between the two assays in a subset of 158 cases of our dataset and we did not notice any significant difference (ΔCt mean ~1.2, t-test p 0.29). In order to evaluate the viral load trend in our COVID-19 patients throughout the pandemic, we evaluated Ct data from 373 patients admitted to the emergency room of our hospital between 1st March and 31st May.

Results

At the emergency room we diagnosed 281 cases in March, 86 in April and six in May. Along with the decrease in the number of cases, we also registered a significant reduction in the proportion of patients requiring intensive care from 6.7% (19/281) in March to 1.1% (1/86) in April, and to none in May (Fisher's test p 0.0067). Table 1 shows the demographical characteristics of the included patients. Patient age and sex distribution significantly changed from March to April. On the other hand, the time lapse between symptom onset and PCR testing did not significantly change through time: a median of 7 days (IQR 3–10) was observed in March, 5 days in April (IQR 1–10) (Wilcoxon two-sample test p 0.2436). Clinical management was partially changed during the course of the pandemic, but the clinical assessment used to decide upon hospital and ICU admission remained substantially the same.

Table 1.

Demographical characteristics

| March | April | May | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort (n = 373) | ||||

| Sexn (%) | ||||

| Female | 97 (34.5) | 52 (60.5) | 1 (16.6) | <0.0001 |

| Male |

184 (65.5) |

34 (39.5) |

5 (83.3) |

|

| Age Median years (Q1–Q3) | ||||

| All patients | 62 (51–75) | 72.5 (53–81) | 71.5 (68–76) | 0.0050 |

| Female | 56 (46–69) | 74 (51–80) | 68b | 0.3360 |

| Male |

63 (53–76) |

71 (55–81) |

72 (71–76) |

0.0494 |

|

Patients admitted to ICU (n = 20) | ||||

| Sexn (%) | NA | |||

| Female | 1 (5.8) | 3 (100) | 0 | |

| Male |

16 (94.1) |

0 |

0 |

|

| Age Median years (Q1–Q3) | ||||

| Female | 72b | 53b | 0 | |

| Male | 67 (65–69) | 74 (75–77) | 0 | 0.1000 |

NA, not applicable.

Comparison between March and April.

Only one subject.

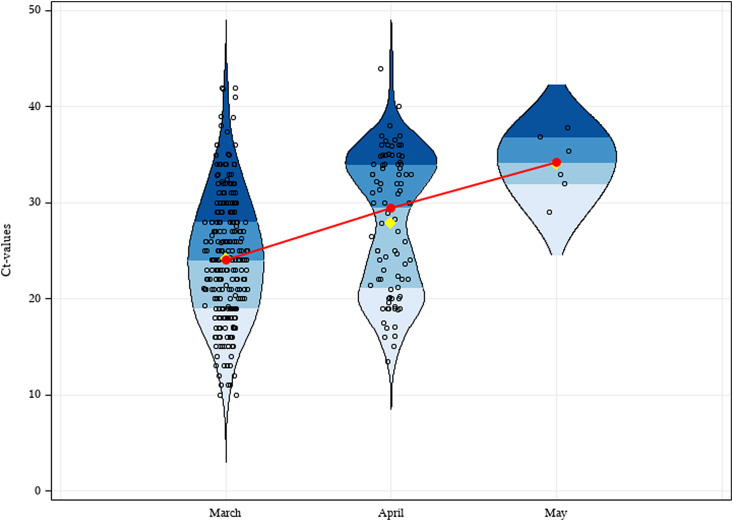

As for viral load, we observed a trend of Ct increasing from a median value of 24 (IQR 19–29) to 34 (IQR 29–37) (Fig. 1 ) between March and May. In other words, based on data obtained with serial ten-fold dilutions of a quantified control sample, the median ΔCt = 10 between March and May indicates a decrease in the detected viral targets of about 1000-fold [7]. Data analysis showed a statistically significant difference between March and April (pairwise Wilcoxon test with stepdown Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing, p 0.0003; Fig. 1). Considering only ICU patients, there was no significant difference in viral load (p 0.8910) when comparing March and April. By contrast, in non-ICU patients we noted that in the same time frame the viral load significantly decreased (p < 0.001). For May, the small number of observations prevented us from drawing conclusions because of uncertainty of the possible range of Ct values.

Fig. 1.

Violin plot showing the distribution of 373 COVID-19 cases, 281 subjects in March (median = 24, Q1 = 19, Q3 = 29), 86 in April (median = 30, Q1 = 21, Q3 = 34) and six in May (median = 34, Q1 = 29, Q3 = 37). Quartiles are represented by blue shades, means by yellow points, and medians by red dots. The red line shows the trend line.

Discussion

In conclusion, along with the decreasing viral load we also observed a significant reduction in severe COVID-19 cases (patients who needed intensive care) throughout the pandemic. Probably the lockdown measures had an impact not only on the absolute number of infected people but also indirectly on the severity of clinical manifestations. Indeed, some authors have supposed that exposure to the infection in a high-transmission setting has an adverse impact on mortality rates compared to what happens in a low-transmission setting [8]. In the latter, people are presumably exposed to a lower viral load, and this has previously been associated with less severe clinical manifestations [9].

Of course, other factors might have had an influence on the decrease in severe cases, such as stricter adherence to quarantine of the most fragile groups of people (i.e. those with chronic conditions and the elderly). In our cohort, median age increased from March to April, but older age has been associated with a worse outcome [10], so we suppose that this factor might not have a major role in our findings. Conversely, the relevance of the transmission setting seems plausible, and efforts aimed at maintaining a low-transmission setting probably have a positive impact on the clinical expression of new COVID-19 cases.

Author contributions

CP, FG and DB conceived and designed the study. CP, MD, EP, FF and FP collected and interpreted the data. RS, CP, EP, MD, FG and DB analysed and interpreted the data. CP, DB and FG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version.

Transparency declaration

All authors declare no conflicts of interest. This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health ‘Fondi Ricerca corrente—L1P5’ to IRCCS Sacro Cuore—Don Calabria Hospital.

Editor: A Kalil

References

- 1.Romagnani P., Gnone G., Guzzi F., Negrini S., Guastalla A., Annunziato F. The covid-19 infection: lessons from the Italian experience. J Public Health Policy. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00229-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track covid-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covid-19 dashboard by the center for systems science and engineering (csse) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

- 4.Italian Prime Ministry Decreto del presidente del consiglio dei ministri. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/09/20A01558/sg

- 5.World Health Organization . 2020. Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease (covid-19) in suspected human cases, interim guidance.https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/technical-guidance/2020/laboratory-testing-for-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-in-suspected-human-cases-interim-guidance,-19-march-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-ncov) by real-time rt-pcr. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pcr and the 2(-delta delta c(t)) method. Methods (San Diego, Calif) 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen D., Hu C., Su F., Song Q., Wang Z. Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in a high transmission setting increases the risk of severe covid-19 compared to exposure to a low transmission setting? J Trav Med. 2020;27 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y., Yan L.M., Wan L., Xiang T.-X., Le A., Liu J.-M. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of covid-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:656–657. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poletti P., Tirani M., Cereda D., Trentini F., Guzzetta G., Marziano V. Age-specific sars-cov-2 infection fatality ratio and associated risk factors, Italy, february to april 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2001383. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.31.2001383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]