Introduction

Prof. M. Kudo Editor Liver Cancer

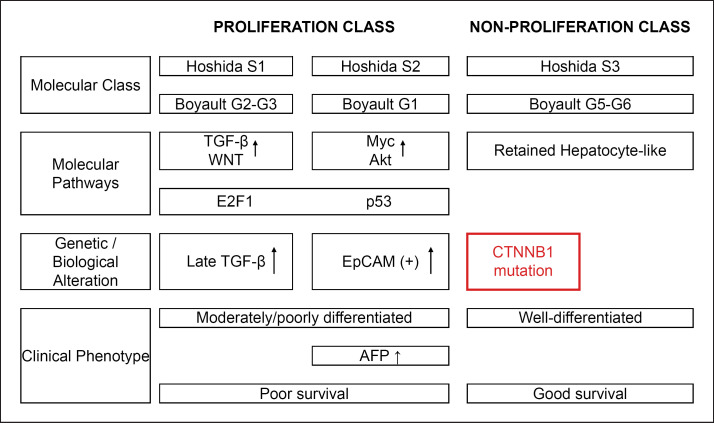

Approximately 11–37% of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) have WNT/β-catenin mutations [1]. These HCCs are classified as either S3, according to the molecular classification of HCC proposed by Hoshida et al. [2], or G5-G6, according to the molecular classifications of Boyault et al.[3] and Zucman-Rossi et al. [4], and they have a more favorable prognosis than other subclasses [5, 6] (Fig. 1).

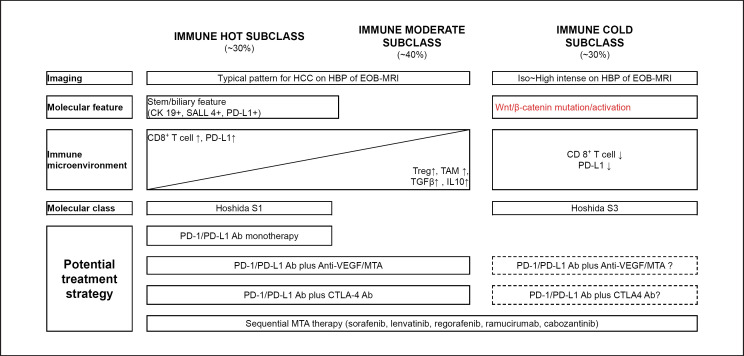

Fig. 1.

Molecular classification of HCC. The figure is based on previous studies [2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

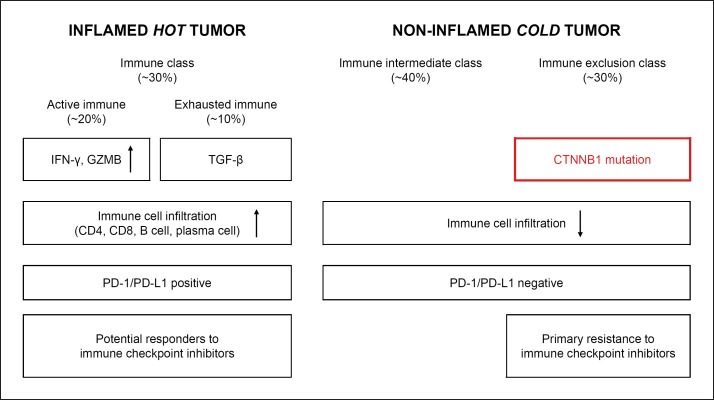

The development of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapies led to the classification of HCC into immune subclasses according to the tumor microenvironment (TME), which should affect the outcome of ICI therapy [7, 8, 9, 10]. For example, Llovet et al. [10] proposed 3 immune-specific subtypes, i.e., an immune class, an immune intermediate class, and an immune exclusion class; 20–30% of HCC belong to the immune exclusion class with WNT/β-catenin mutations [11] (Fig. 2). Kurebayashi et al. [8] proposed 3 subclasses (immune high, immune-mid, and immune-low subtypes) and showed that infiltration of B cells and plasma cells, as well as of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, is responsible for the high antitumor immune response of the immune-high subtype [12]. In any classification system, the subclasses carrying activation mutation in the WNT/β-catenin pathway are poorly immunogenic; the resulting inhibition of dendritic cell (DC) recruitment and suppression of CD8+ cell infiltration to cancerous tissues leads to resistance to ICI therapy. This prediction is supported by clinical cases, although few have been reported [13].

Fig. 2.

Immune subclasses of HCC. The figure is based on previous studies [10, 11, 13].

HCC with WNT/β-catenin mutations show an iso-high intensity in the hepatobiliary phase (HBP) of gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (Gd-EOB-DTPA-MRI: EOB-MRI) and a favorable prognosis [14]. This is consistent with the classification of patients with WNT/β-catenin mutations into molecular subclasses with a favorable prognosis, i.e., S3 according to Hoshida et al.[2], and G5-G6 according to Boyault et al.[3] and Zucman-Rossi et al. [4, 5, 6]. WNT/β-catenin mutations induce the expression of organic anion transporter 1B3 (OATP1B3), a transporter of Gd-EOB-DTPA [15], suggesting that the HBP of EOB-MRI is a molecular imaging biomarker of OATP1B3 (and WNT/β-catenin mutation) and could predict resistance to ICI therapy in a noninvasive manner [15].

WNT/β-Catenin Mutations Promote Immune Escape

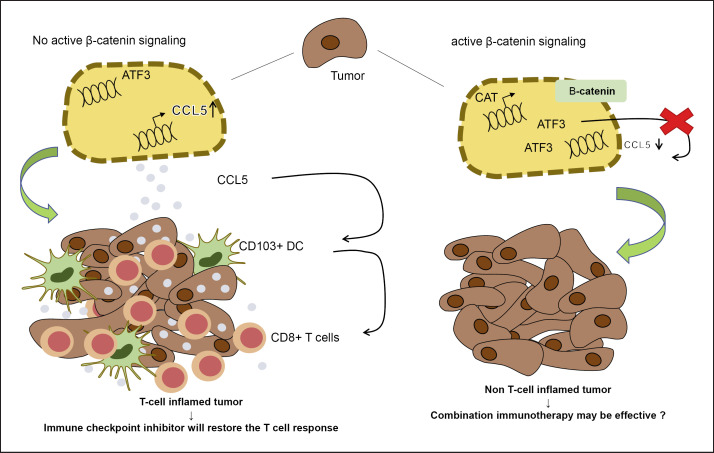

Mutation in the CTNNB1, which encodes β-catenin, is present in 20–30% of HCC, and these types show a pseudoglandular pattern without marked lymphocytic infiltrate [5]. Melanoma with WNT/β-catenin mutations is characterized by a decreased recruitment of CD103+ DCs and CD8+ T cells, and the underlying mechanism involves the induction of activating transcription factor 3 via WNT/β-catenin signaling and the consequent decrease in chemokine (c-c motif) ligand 4 (CCL4) production [16, 17] (Fig. 3). A recent study using a murine HCC model and human HCC samples showed that CXCL1, CCL20, and CCL5, but not CCL4, are downregulated in HCC with WNT/β-catenin mutations [18]. Furthermore, CCL5 overexpression induces the recruitment of CD103+ DC and antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, suggesting that the role of CCL5 in immune escape in HCC is more critical than that of CCL4 [18, 19] (Fig. 3). Taken together, these findings suggest that ICI have a limited effect on HCC with WNT/β-catenin mutations because they are poorly immunogenic and have a suppressed antitumor response, i.e., primary resistance to ICI [10, 13].

Fig. 3.

Mechanism underlying non-T-cell-inflamed tumor development caused by WNT/β-catenin mutations. ATF3, activating transcription factor 3. The figure is based on previous studies [16, 17, 18, 19].

WNT/β-catenin mutations in HCC decrease the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the tumor tissues by reducing the recruitment of CD103+ DC, a state referred to variably as “immune exclusion,” “noninflamed phenotype,” “cold tumor”, or “immune desert.” Sia et al. [7] and Llovet et al. [10] categorized HCC harboring WNT/β-catenin mutations in the immune exclusion subclass, and they provided a theoretical and experimental basis for the resistance of this subclass to ICI therapy (Fig. 2).

Resistance to ICI in HCCs with WNT/β-Catenin Mutations

Harding et al. [13] treated 31 advanced HCC patients with ICI therapy (anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy [n = 1], anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy [n = 25], and anti PD-1/PD-L plus other ICI including anti-CTLA-4 [n = 1], anti-LAG3 [n = 2], and anti-KIR [n = 2]) and conducted next-generation sequencing analysis. Of the 31 advanced HCC patients, 27 were evaluable, including 10 with WNT/β-catenin mutations and 17 without. The 10 patients with WNT/β-catenin mutations did not respond to therapy at all, and the best objective response was progressive disease (PD) in all patients (Table 1). Conversely, among the 17 patients without WNT/β-catenin mutations, a complete response was achieved in 1 (6%), a partial response in 2 (12%), stable disease (SD; defined as SD for ≥4 months) in 9 (53%), and PD in only 5 patients (29%; Table 1). Progression-free survival (PFS) was shorter in the 10 patients with WNT/β-catenin mutations than in the 17 patients without (2 vs. 7.4 months; HR = 9.2; 95% CI 2.9–2.89; p < 0.0001). Similarly, overall survival (OS) was shorter in the 10 patients with WNT/β-catenin mutations than in those without (9.1 vs. 15.2 months, respectively; HR = 2.6; 95% CI 0.76–8.7; p = 0.11; Table 1).

Table 1.

Efficacy of ICI in patients with advanced HCC

| All patients (n = 27) | WNT/β-catenin mutation/activation (n = 10) | Non-WNT/β-catenin mutation/activation (n = 17) | HR (95% CI), p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | p = 0.009 |

| PR | 2 (7.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | |

| SDa | 10 (37) | 0 (0) | 9 (53) | |

| PD | 14 (51.9) | 10 (100) | 5 (29) | |

| ORR | 3 (11) | 0 (0) | 3 (18) | |

| DCR | 13 (48) | 0 (0) | 12 (71) | |

| PFS, months | 5.4 | 2.0 | 7.4 | 9.2 (2.9–2.89), <0.0001 |

| OS, months | 12.9 | 9.1 | 15.2 | 2.6 (0.76–8.7), 0.11 |

The total number of patients is 27. Values are presented as numbers (%) unless otherwise stated. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; OS, overall survival. a Durable SD (≥4 months).

In 179 sorafenib-treated patients who underwent gene sequencing, PFS did not differ between those with and without WNT/β-catenin mutations (4.5 vs. 5.1 months; p = 0.44; Table 2). Sorafenib was effective regardless of the WNT/β-catenin mutation status, and this may be the same for other molecular targeted agents (MTA) such as lenvatinib, ramucirumab, cabozantinib, and regorafenib. These findings suggest that the WNT/β-catenin mutation status does not affect the efficacy of MTA.

Table 2.

PFS of patients with advanced HCC treated with ICI and sorafenib

| WNT/β-catenin mutation/activation | Non-WNT/β-catenin mutation/activation | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICIa (n = 27), months Sorafenib (n = 79), months | 2.0 4.5 |

7.4 5.1 |

<0.0001 0.44 |

Including anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy (n = 1), anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy (n = 25), and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 + other ICI (anti-CTLA-4 [n = 1], anti-LAG3 [n = 2] and anti-KIR [n = 2]). Cited from Harding et al. [13].

This was a breakthrough that provided clinical proof, albeit in a small number of cases, of the hypothesis that HCC with WNT/β-catenin mutation/activation are immune cold tumors because of decreased tumor infiltration of CD8+ T cells and are thus resistant to ICI therapy. Studies also show that conventional treatment such as sequential therapy with MTA can be effective in HCC patients with WNT/β-catenin mutations. These results suggest the possibility of biomarker selection trials for ICI therapy in which immune-excluded tumors (i.e., tumors harboring WNT/β-catenin mutations) should be excluded from the trial of ICI therapy.

At present, however, it remains unclear whether combination therapies such as ICI plus anti-VEGF/MTA therapy are effective in HCC harboring WNT/β-catenin mutations and consequently CD8+ T-cell exclusion. The PD rate was 37% with nivolumab monotherapy in the CheckMate 459 trial [20], 32.4% with pembrolizumab monotherapy in KEYNOTE 240 [21], and 20% with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab combination therapy in the IMbrave 150 trial [22]. Moreover, the PD rate of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab was extremely low (7%) per RECIST 1.1 in a phase 1b study [23]. These results imply that patients with tumors of the immune exclusion class are resistant to ICI monotherapy, although some may respond to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody plus anti-VEGF/MTA combination therapy [24] at least due to additive anticancer effect of MTA, which is not affected by WNT/β-catenin mutation status.

EOB-MRI Is a Molecular Imaging Biomarker of OATP1B3

EOB-MRI is a well-established imaging modality with a high accuracy for diagnosing HCC. Gd-EOB-DTPA is a liver-specific contrast agent for MRI that is preferentially taken up by hepatocytes through OATP1B3 [25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. In the HBP phase of EOB-MRI, typical HCC commonly show low intensity compared with the surrounding liver parenchyma. However, 10–20% of hypervascular typical HCC show an iso-high intensity in the HBP of EOB-MRI [25, 26, 27, 28].

In accordance with the decrease in the relative enhancement ratio (RER), which is the ratio of the enhancement intensity in the tumor region to that in the nontumor region in the HBP of EOB-MRI, immunohistochemical staining for OATP1B3 in resected specimens showed a gradual decrease of OATP1B3 expression in correlation with multistep carcinogenesis from low-grade dysplastic nodule (DN) to high-grade DN, early HCC, well-differentiated HCC, moderately differentiated HCC, and finally poorly differentiated HCC [29]. Immunohistological staining showed strong OATP1B3 expression in a particular form of hypervascular nodules characterized by hyperintensity in the HBP of EOB-MRI [26, 27]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the HBP of EOB-MRI is an imaging biomarker or a molecular biomarker of OATP1B3 [29].

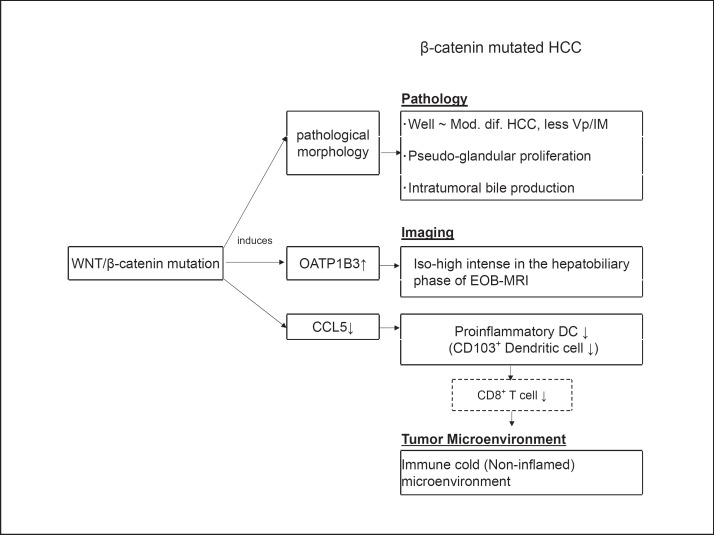

OATP1B3 Is Induced by WNT/β-Catenin Mutations

Ueno et al. [15] showed a strong correlation between OATP1B3 mRNA expression and downstream targets of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway (CYP2E1, GS, OAT, AXIN2,and LGR5), suggesting that the expression of OATP1B3 should be regulated by the WNT/β-catenin pathway. These authors showed that treating KYN-2 cell lines with the agonist of the canonical WNT signaling lithium chloride (LiCl) upregulates OATP1B3 mRNA as well as axis inhibition protein 2 (AXIN2) and leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5), suggesting that WNT/β-catenin signaling induces OATP1B3. They also found that tumor cholestasis, which is known to be associated with WNT/β-catenin mutations, was correlated with OATP1B3 expression. This association has also been reported in other studies [14, 30] (Fig. 4). These findings led Ueno et al. [15] to suggest the possibility of noninvasive diagnosis of WNT/β-catenin mutations by EOB-MRI.

Fig. 4.

Pathology, imaging, and TME in WNT/β-catenin-mutated HCC.

Pathological Characteristics and Aggressiveness of Tumors with a High OATP1B3 Expression (β-Catenin-Mutated HCC)

High-intensity HCC (HCC with a high expression of OATP1B3) show lower levels of tumor markers such as AFP, PIVKA-II (DCP), and AFP-L3, less portal infiltration, and significantly more favorable outcomes (based on the recurrence rate and OS after resection) than low-intensity HCC on the HBP of EOB-MRI [14, 26, 27, 31]. Many HCC with a high OATP1B3 expression are well differentiated or moderately differentiated but not poorly differentiated. Many are of the pseudoglandular pathological type and show increased intratumoral bile production [14, 15, 30] (Fig. 4). Immunohistological staining shows that portal vascular invasion and intrahepatic metastases occur with a low frequency in HCC with a high OATP1B3 expression [32]. Taken together, these findings indicate that HCC with OATP1B3 expression are tumors with a relatively low malignancy and a favorable prognosis. This is consistent with the finding that β-catenin-activated HCC are included in molecular subclasses with a favorable prognosis, such as S3 according to the classification of Hoshida et al. [2] and G5-G6 according to the classifications of Boyault et al. [3] and Zucman-Rossi et al. [4] (Fig. 1).

EOB-MRI Could Predict WNT/β-Catenin Mutations and Resistance to Immunotherapy

Taken together, these findings lead to the following conclusions: (1) OATP1B3 is a transporter of EOB; (2) WNT/β-catenin signaling induces OATP1B3; (3) the HBP of EOB-MRI is a molecular imaging biomarker of OATP1B3 expression status; (4) consequently, progressed HCC with an iso-high intensity (i.e., not clearly low intensity) in the HBP of EOB-MRI is considered to carry activating mutations in the WNT/β-catenin-pathway; and (5) ultimately the HBP of EOB-MRI may help identity patients with a primary resistance to ICI therapy.

Ueno et al. [15] reported that the HBP of EOB-MRI identifies WNT/β-catenin-activated HCC (RER ≥0.9) with a sensitivity of 78.9% and a specificity of 81.7%. In the same study, of 101 resected cases 30 (30%) had an RER ≥0.9, which is in good agreement with the frequency of WNT/β-catenin mutations of 20–30% in HCC reported previously [1, 7, 10, 18].

Possible Treatment Strategy for the Immune Subclass Including EOB-MRI Findings

Llovet et al. [10] divided HCC into inflamed hot tumors and noninflamed tumors and further divided inflamed hot tumors into an active immune class and an exhausted immune class [11]. These authors reported that patients in both immune classes are potential responders to ICI therapy (Fig. 2). By contrast, 20–30% of patients with HCC of the immune exclusion class may be resistant to ICI therapy because of a reduced CD8+ T-cell infiltration into tumors due to mutation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway and the absence of PD-L1 expression in cancer cells [10, 11] (Fig. 2, 5). These predictions were successfully proven clinically in the study of Harding et al. [13] mentioned earlier. In contrast, high PD-L1 expression is associated with CK19 and SALL4 expression, and ICI monotherapy should be effective in HCC with these characteristics [8, 33, 34] (Fig. 2, 5).

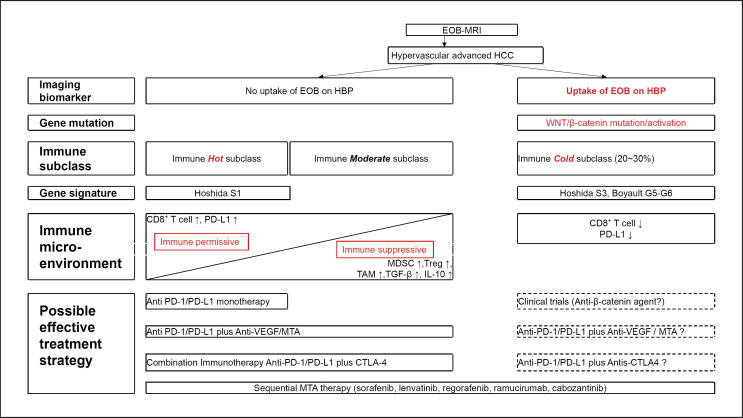

Fig. 5.

Immunological classification and possible treatment strategy. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; Treg, regulatory T cell; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage.

In a recent research breakthrough, the HBP of EOB-MRI predicted the WNT/β-catenin mutation that induces OATP1B3 [15, 33]. This suggests that EOB-MRI can be useful in the clinical setting for identifying the immune exclusion class that is highly unlikely to respond to ICI monotherapy. Indeed, in our experience, ICI monotherapy is not effective and actually causes marked progression in HCC with WNT/β-catenin mutation showing an iso-high intensity in the HBP of EOB-MRI (Fig. 6). In addition, HCC patients with an iso-high intensity in the HBP of EOB-MRI who received ICI monotherapy had a poorer PFS than HCC patients with a low intensity in the HBP of EOB-MRI in our experience (manuscript submitted elsewhere). Therefore, the HBP of EOB-MRI may serve as an imaging biomarker to select poorly responding subpopulations of patients who can be excluded from clinical trials of ICI or ICI treatment in real-world practice (Fig. 7).

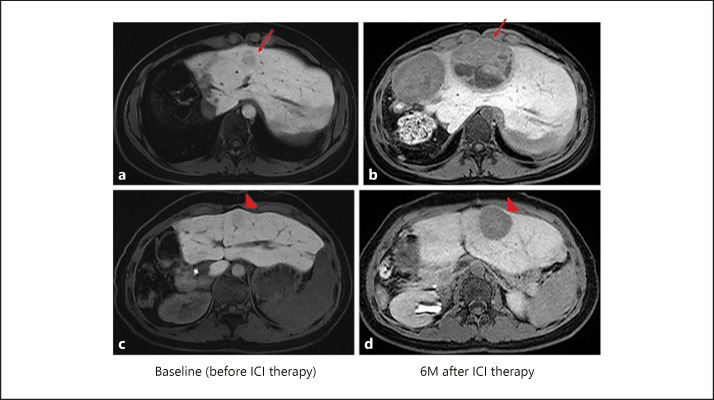

Fig. 6.

Hyperprogression caused by anti-PD-1 antibody monotherapy. This patient had a mutation in WNT/β-catenin confirmed by cancer genome sequencing with a next-generation sequencer using tissue from a previously resected tumor specimen. At baseline before ICI therapy, a 15-mm nodule that showed near iso-intensity in the HBP of EOB-MRI (arrow in a) increased to 74 mm in size 6 months after ICI (anti-PD-1 antibody) monotherapy (arrow in b). Another 16-mm nodule (arrowhead in c) that also showed near iso-intensity in the HBP of EOB-MRI grew to 36 mm (arrowhead in d) 6 months after ICI monotherapy.

Fig. 7.

Possible role of EOB-MRI in treatment selection. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; Treg, regulatory T cell; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage.

ICI monotherapy is not effective in HCC of the immune exclusion type with activating WNT/β-catenin mutation; however, it remains unclear whether combination therapies (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy plus anti-CTLA-4 therapy or anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy plus anti-VEGF/MTA therapy) [35, 36, 37] can alter the TME and induce a change from immune suppressive to immune permissive even in β-catenin-mutated HCC [38, 39], which would revert the decreased DC recruitment and CD8+ T-cell infiltration into tumors caused by β-catenin activation. These issues need to be confirmed in future studies.

A recent phase 1b study showed that the objective response rate (ORR; according to RECIST version 1.1) of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (arm A) was 36% [40], which was markedly higher than the ORR (RECIST version 1.1) of nivolumab monotherapy and pembrolizumab monotherapy (15–18.3%) [20, 21]. This is attributed to the fact that anti-VEGF therapy improves the recruitment of DC, the activation of CD8+ T cells, and trafficking and infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the tumor tissue and improves immunosuppressive TME in the immune moderate subclass [39] (Fig. 5, 7). Furthermore, the ORR (RECIST version 1.1) for pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib (36%) [23] and nivolumab plus lenvatinib (54.2%) [41] is higher than that of the phase 3 atezolizumab plus bevacizumab combination (IMbrave150; 27.3%). This could be attributed to the higher antitumor effect of lenvatinib over bevacizumab [42, 43, 44, 45], specifically, a more effective induction of necrosis in cancer cells, enhanced induction of DC induced by an increased neoantigen release, and more potent trafficking and infiltration of CD8+ T cells into tumors. Therefore, effect of combination immunotherapy with multi-target MTA is highly anticipated [37]. In other words, because MTA are expected to have a certain effect irrespectively of any immune class of HCC, sequential therapy using MTA [44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51] is extremely important in the treatment of the WNT/β-catenin mutation.

Most interestingly, the PD rates in combination trials of pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib [23], and nivolumab plus lenvatinib [41], were considerably lower (7 and 8.3%, respectively) than those of nivolumab (37%) [20] or pembrolizumab monotherapy (32.4%) [21]. The PD rate of 7–8.3% is lower than the rate of the immune exclusion class with WNT-β-catenin mutation of 20–30% [10, 11]. These favorable results (low PD rates) of combination immunotherapy could be attributed simply to the additive anticancer effect by lenvatinib with a high response rate of 40.8% [44, 45], even in HCC with WNT/β-catenin mutation. On the other hand, there is a possibility that this low PD rate may be due to the synergistic effect of combination therapy which may alter the TME from immune suppressive to immune permissive even in immune exclusion subclass, WNT/β-catenin-mutated HCC. It may be easily identified whether this hypothesis is true or not by gene sequencing using a next-generation sequencer in the prospective cohort treated with this combination immunotherapy.

In any case, this important question, i.e., whether the low PD rate in combination immunotherapy is a result of an additive or synergistic effect of MTA, should be clarified in future studies.

Conclusion

The signal intensity in the HBP of EOB-MRI is an imaging biomarker of OATP1B3 and can also be considered an imaging biomarker of WNT/β-catenin mutation/activation. This suggests that the signal intensity on HBP of EOB-MRI can be used to noninvasively predict the effect of ICI monotherapy. This hypothesis should be verified in a larger number of studies in the future.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author has received honoraria from Eisai, Bayer, MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, and EA Pharma and grants from Gilead Sciences, Taiho, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Takeda, Otsuka, EA Pharma, Abbvie, and Eisai and has had an advisory role in Eisai, Ono, MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Roche.

Funding Sources

There are no funding sources to declare.

Author Contributions

M.K. conceived, wrote, and approved the final version of this work.

References

- 1.Torbenson MS, Ng IO, Park YN, Roncalli M, Sakamoto M. Digestive system tumours: WHO classification of tumours. 5th ed. Geneva: WHO Press; 2019. Hepatocellular carcinoma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, editor; pp. p. 229–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoshida Y, Nijman SM, Kobayashi M, Chan JA, Brunet JP, Chiang DY, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009 Sep;69((18)):7385–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyault S, Rickman DS, de Reyniès A, Balabaud C, Rebouissou S, Jeannot E, et al. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology. 2007 Jan;45((1)):42–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, Llovet JM. Genetic Landscape and Biomarkers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015 Oct;149((5)):1226–1239.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calderaro J, Couchy G, Imbeaud S, Amaddeo G, Letouzé E, Blanc JF, et al. Histological subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma are related to gene mutations and molecular tumour classification. J Hepatol. 2017 Oct;67((4)):727–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calderaro J, Ziol M, Paradis V, Zucman-Rossi J. Molecular and histological correlations in liver cancer. J Hepatol. 2019 Sep;71((3)):616–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sia D, Jiao Y, Martinez-Quetglas I, Kuchuk O, Villacorta-Martin C, Castro de Moura M, et al. Identification of an Immune-specific Class of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Based on Molecular Features. Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep;153((3)):812–26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurebayashi Y, Ojima H, Tsujikawa H, Kubota N, Maehara J, Abe Y, et al. Landscape of immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma and its additional impact on histological and molecular classification. Hepatology. 2018 Sep;68((3)):1025–41. doi: 10.1002/hep.29904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada S, Mogushi K, Akiyama Y, Furuyama T, Watanabe S, Ogura T, et al. Comprehensive molecular and immunological characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. EBioMedicine. 2019 Feb;40:457–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llovet JM, Montal R, Sia D, Finn RS. Molecular therapies and precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Oct;15((10)):599–616. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinyol R, Sia D, Llovet JM. Immune Exclusion-Wnt/CTNNB1 Class Predicts Resistance to Immunotherapies in HCC. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2019;25:2021–2023. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garnelo M, Tan A, Her Z, Yeong J, Lim CJ, Chen J, et al. Interaction between tumour-infiltrating B cells and T cells controls the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2017 Feb;66((2)):342–51. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding JJ, Nandakumar S, Armenia J, Khalil DN, Albano M, Ly M, Shia J, Hechtman JF, Kundra R, El Dika I, Do RK, Sun Y, Kingham TP, D'Angelica MI, Berger MF, Hyman DM, Jarnagin W, Klimstra DS, Janjigian YY, Solit DB, Schultz N, Abou-Alfa GK. Prospective Genotyping of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Clinical Implications of Next-Generation Sequencing for Matching Patients to Targeted and Immune Therapies. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2019;25:2116–2126. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitao A, Matsui O, Yoneda N, Kozaka K, Kobayashi S, Sanada J, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma with β-Catenin Mutation: Imaging and Pathologic Characteristics. Radiology. 2015 Jun;275((3)):708–17. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14141315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueno A, Masugi Y, Yamazaki K, Komuta M, Effendi K, Tanami Y, et al. OATP1B3 expression is strongly associated with Wnt/β-catenin signalling and represents the transporter of gadoxetic acid in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014 Nov;61((5)):1080–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015 Jul;523((7559)):231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue G, Romano E, Massi D, Mandalà M. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in melanoma: preclinical rationale and novel therapeutic insights. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016 Sep;49:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruiz de Galarreta M, Bresnahan E, Molina-Sánchez P, Lindblad KE, Maier B, Sia D, et al. β-Catenin Activation Promotes Immune Escape and Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019 Aug;9((8)):1124–41. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chabot V, Reverdiau P, Iochmann S, Rico A, Sénécal D, Goupille C, et al. CCL5-enhanced human immature dendritic cell migration through the basement membrane in vitro depends on matrix metalloproteinase-9. J Leukoc Biol. 2006 Apr;79((4)):767–78. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, Cheng AL, Mathurin P, Edeline J, et al. CheckMate 459: A randomized, multi-center phase III study of nivolumab vs sorafenib as first-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 5):v874–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, Kudo M, Bouattour M, Lim HY, et al. KEYNOTE-240 investigators Pembrolizumab As Second-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jan;38((3)):193–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. IMbrave150 Investigators Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020 May;382((20)):1894–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Ikeda M, Sung MW, Baron AD, Kudo M, Bouattour M, Lim HY, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:193–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kudo M. A New Era in Systemic Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab Combination Therapy. Liver Cancer. 2020 Apr;9((2)):119–37. doi: 10.1159/000505189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narita M, Hatano E, Arizono S, Miyagawa-Hayashino A, Isoda H, Kitamura K, et al. Expression of OATP1B3 determines uptake of Gd-EOB-DTPA in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44((7)):793–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitao A, Zen Y, Matsui O, Gabata T, Kobayashi S, Koda W, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: signal intensity at gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR Imaging—correlation with molecular transporters and histopathologic features. Radiology. 2010 Sep;256((3)):817–26. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10092214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitao A, Matsui O, Yoneda N, Kozaka K, Kobayashi S, Koda W, et al. Hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation between biologic features and signal intensity on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR images. Radiology. 2012 Dec;265((3)):780–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuboyama T, Onishi H, Kim T, Akita H, Hori M, Tatsumi M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: hepatocyte-selective enhancement at gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging—correlation with expression of sinusoidal and canalicular transporters and bile accumulation. Radiology. 2010 Jun;255((3)):824–33. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitao A, Matsui O, Yoneda N, Kozaka K, Shinmura R, Koda W, et al. The uptake transporter OATP8 expression decreases during multistep hepatocarcinogenesis: correlation with gadoxetic acid enhanced MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2011 Oct;21((10)):2056–66. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sekine S, Ogawa R, Ojima H, Kanai Y. Expression of SLCO1B3 is associated with intratumoral cholestasis and CTNNB1 mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2011 Sep;102((9)):1742–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamashita T, Kitao A, Matsui O, Hayashi T, Nio K, Kondo M, et al. Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and alpha-fetoprotein predict prognosis of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014 Nov;60((5)):1674–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.27093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsujikawa H, Masugi Y, Yamazaki K, Itano O, Kitagawa Y, Sakamoto M. Immunohistochemical molecular analysis indicates hepatocellular carcinoma subgroups that reflect tumor aggressiveness. Hum Pathol. 2016 Apr;50:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ueno A, Masugi Y, Yamazaki K, Kurebayashi Y, Tsujikawa H, Effendi K, et al. Precision pathology analysis of the development and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma: implication for precision diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Int. 2020 Mar;70((3)):140–54. doi: 10.1111/pin.12895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishida N, Sakai K, Morita M, Aoki T, Takita M, Hagiwara S, et al. Association between genetic and immunological background of hepatocellular carcinoma and expression of programmed cell death-1. Liver Cancer. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1159/000506352. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudo M. Combination Cancer Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2018 Mar;7((1)):20–7. doi: 10.1159/000486487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu LC, Lee YH, Chang CJ, Shun CT, Fang CY, Shao YY, et al. Increased Expression of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 in Infiltrating Immune Cells in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tissues after Sorafenib Treatment. Liver Cancer. 2019 Mar;8((2)):110–20. doi: 10.1159/000489021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kudo M. Immuno-Oncology Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Status and Ongoing Trials. Liver Cancer. 2019 Jul;8((4)):221–38. doi: 10.1159/000501501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teng MW, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Smyth MJ. Classifying Cancers Based on T-cell Infiltration and PD-L1. Cancer Res. 2015 Jun;75((11)):2139–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kudo M. Scientific Rationale for Combined Immunotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 Antibodies and VEGF Inhibitors in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020 Apr;12((5)):12. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee MS, Ryoo BY, Hsu CH, Numata K, Stein S, Verret W, et al. GO30140 investigators Atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (GO30140): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Jun;21((6)):808–20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30156-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kudo M, Ikeda K, Motomura K, Okusaka T, Kato N, Dutcus CE, et al. A phase 1b study of lenvatinib plus nivolumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. ASCO-GI. 2020 Jan;:23–25. San Francisco, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegel AB, Cohen EI, Ocean A, Lehrer D, Goldenberg A, Knox JJ, et al. Phase II trial evaluating the clinical and biologic effects of bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jun;26((18)):2992–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wattenberg MM, Damjanov N, Kaplan DE. Utility of bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A veterans affairs experience. Cancer Med. 2019 Apr;8((4)):1442–6. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018 Mar;391((10126)):1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kudo M. Extremely High Objective Response Rate of Lenvatinib: Its Clinical Relevance and Changing the Treatment Paradigm in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2018 Sep;7((3)):215–24. doi: 10.1159/000492533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouattour M, Mehta N, He AR, Cohen EI, Nault JC. Systemic Treatment for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2019 Oct;8((5)):341–58. doi: 10.1159/000496439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kudo M. Targeted and immune therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: predictions for 2019 and beyond. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Feb;25((7)):789–807. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i7.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, et al. REACH-2 study investigators Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Feb;20((2)):282–96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. RESORCE Investigators Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017 Jan;389((10064)):56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. SHARP Investigators Study Group Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul;359((4)):378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul;379((1)):54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]