Abstract

Background

With the rise of connected sensor technologies, there are seemingly endless possibilities for new ways to measure health. These technologies offer researchers and clinicians opportunities to go beyond brief snapshots of data captured by traditional in-clinic assessments, to redefine health and disease. Given the myriad opportunities for measurement, how do research or clinical teams know what they should be measuring? Patient engagement, early and often, is paramount to thoughtfully selecting what is most important. Regulators encourage stakeholders to have a patient focus but actionable steps for continuous engagement are not well defined. Without patient-focused measurement, stakeholders risk entrenching digital versions of poor traditional assessments and proliferating low-value tools that are ineffective, burdensome, and reduce both quality and efficiency in clinical care and research.

Summary

This article synthesizes and defines a sequential framework of core principles for selecting and developing measurements in research and clinical care that are meaningful for patients. We propose next steps to drive forward the science of high-quality patient engagement in support of measures of health that matter in the era of digital medicine.

Key Messages

All measures of health should be meaningful, regardless of the product's regulatory classification, type of measure, or context of use. To evaluate meaningfulness of signals derived from digital sensors, the following four-level framework is useful: Meaningful Aspect of Health, Concept of Interest, Outcome to be measured, and Endpoint (exclusive to research). Incorporating patient input is a dynamic process that requires more than a single, transactional touch point but rather should be conducted continuously throughout the measurement selection process. We recommend that developers, clinicians, and researchers reevaluate processes for more continuous patient engagement in the development, deployment, and interpretation of digital measures of health.

Keywords: Digital medicine, Patient engagement, Digital measures

Principles of Digital Measurements of Health

Measurement is fundamental to defining health and disease. Regulators describe the measurable characteristic of a disease as an outcome, and the measurement itself as a value obtained by a test, tool, or instrument [1].

With the rise of connected sensor technologies such as smartphones, wearables, implantables, ingestibles, and other sensors in the home with wireless protocols to upload data to a server, the possibilities of measuring individuals' biological processes, and characteristics of how they feel and function, are seemingly infinite. Researchers and clinicians have the opportunity to go beyond brief snapshots of data captured by traditional in-clinic assessments, to redefine health and disease.

Just Because We Can, Does It Mean We Should?

Given the myriad opportunities for measurement, how do we know what we shouldbe measuring?

Patient engagement, early and often, is paramount to thoughtfully selecting what is most important. Regulators encourage stakeholders to have a patient focus, but actionable steps for continuous engagement are not well defined [2]. Without patient-focused measurement, stakeholders risk entrenching digital versions of poor traditional assessments and proliferating low-value tools that are ineffective, burdensome, and reduce both quality and efficiency in clinical research and care.

For example, the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) is widely used in clinical practice and clinical trials across a broad range of conditions including cardiovascular, pulmonary, inflammatory, and central nervous system diseases, and post-op patients. While the evaluation is cheap and requires little training, the 6MWT is a poor measure and it is not specified how the assessment is intended to represent a patient's meaningful functional abilities in real life. The 6MWT shows inconsistent correlation with clinical endpoints such as mortality [3], lack of specificity in some patient populations [4], and systematically excluding non-ambulatory members of other patient populations [5]. Despite cries against the measure from patients and clinicians [6], the 6MWT has been widely adopted by professional societies and frequently included as an endpoint in clinical trials.

How can we ensure that we are developing high-quality, patient-centric, digital measures of health? In other words, how can we ensure that new digital measures are effective in detecting change in what matters to patients in their everyday lives? What steps can the rapidly advancing field of digital medicine take to ensure that we do not develop a litany of new digital measures that lack relevance to patients and clinicians?

Here, we synthesize and define a sequential framework of core principles for selecting and developing measurements in research and clinical care that are meaningful for patients. Building upon work from the FDA-NIH's BEST framework, the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI) Mobile Clinical Trials Program, and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research's (ISPOR) ClinRO Good Practices for Outcomes Research Task Force [7, 8, 9], we target new stakeholders (technologists, data scientists, and citizen scientists) engaging in the measurement of health for the first time. We propose next steps to drive forward the science of high-quality patient engagement in support of measures of health that matter in the era of digital medicine.

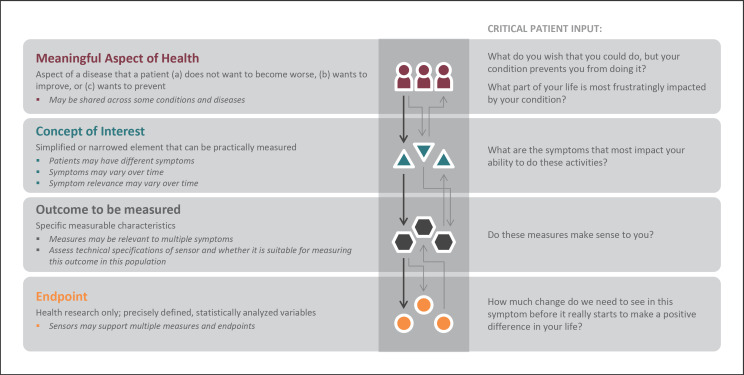

Framework for Meaningful Measurement: A Four-Level Process

Improving a measure of health through a therapeutic intervention can only be considered beneficial if the improvement matters to the patient. To evaluate meaningfulness of signals derived from digital sensors, the following four-level framework is useful:

Meaningful Aspect of Health (MAH)

Concept of Interest (COI)

Outcome to be measured

Endpoint (exclusive to research)

In order for the framework to be effective, levels 1–4 should be followed sequentially and in partnership with patients at every step [8, 10]. Defining the MAH before selecting concepts, outcomes, or endpoints (exclusive to research) is the best way to ensure patient-focused measurement. Incorporating patient input is a dynamic process that requires more than a single, transactional touch point in a focus group, but rather is conducted continuously throughout the measurement selection process. Here, we focus on defining the four levels of measurement selection with a call to action for stakeholders to reevaluate their traditional patient engagement practices.

Meaningful Aspect of Health

An MAH broadly defines an aspect of a disease that a patient (a) does not want to become worse, (b) wants to improve, or (c) wants to prevent [8, 9]. Patients may describe specific and unique activities of their day such as fear of falling down the stairs, or a desire to maintain independence by being able to walk to the bus stop or around the grocery store. Such activities can be grouped into an MAH category that can be readily assessed in clinical care or research. For example, walking independently outside to enjoy the yard or the ability to make it around the grocery store to complete the weekly shop can be grouped together as the ability to perform ambulatory activities [9]. For a treatment or intervention to be proven beneficial, researchers and clinicians should strive to achieve positive changes in the specific daily activities that patients report [7].

Concept of Interest

Once the MAH is identified, a COI can be defined. The COI is a simplified or narrowed element of an MAH that can be practically measured [8, 9]. As shown in Figure 1, a single MAH can have multiple concepts depending on patient input. For example, the MAH “ability to perform ambulatory activities” can have multiple COIs, such as walking capacity, lower extremity balance, or lower extremity strength, depending on the patient population. Selecting an appropriate COI is a crucial step in narrowing the MAH into a targeted aspect for actual measurement. Patient input as indicated by the questions in Figure 1 is critical to ensure selection of a COI that is most important for a particular patient group.

Fig. 1.

Examples of how a variety of concepts of interest cascade from a single meaningful aspect of health across select conditions.

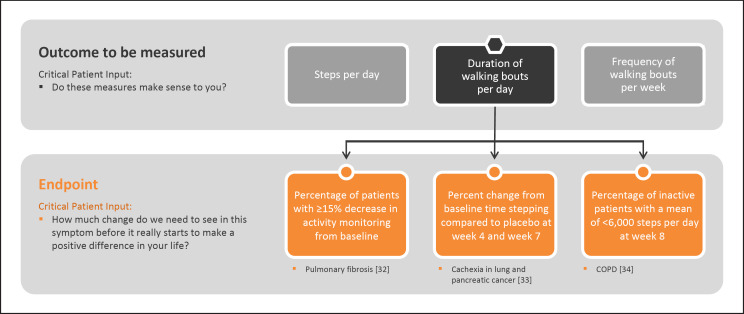

Outcome to Be Measured

Next, the outcome to be measured can be selected. Outcomes are the specific measurable characteristics of the disease that evaluate the MAH as defined by the COI [1]. Regardless of whether the outcomes are measured using clinical outcome assessments, such as surveys, or biomarkers, such as lab tests, it is crucial that they reflect the patient-focused COI [5, 11]. For example, walking capacity is a concept often measured using a 6MWT in a controlled environment, such as a clinic. As shown in Figure 2, a wearable accelerometer can capture steps per day, duration of walking bouts per day, or frequency of walking bouts per week to get a more accurate expanded view of how a disease impacts walking capacity day to day.

Fig. 2.

Examples of how a variety of outcomes cascade from a single concept of interest across select conditions.

It is also essential to obtain evidence to demonstrate that the outcome selected shows a strong relationship back to the COI and, in turn, the desired MAH. Without doing so, the study team cannot infer that observed treatment effects on the outcomes to be measured will be related to treatment effects in the MAH. For the example in Figure 2, study teams would next demonstrate that there is evidence to support that steps per day has a relationship with the MAH “ability to perform ambulatory activities.”

Endpoints

Endpoints are precisely defined variables intended to reflect outcomes of interest that are statistically analyzed to address a particular research question [1]. As such, “digital endpoints” are only relevant in health research and are not part of routine clinical care. In clinical trials, an endpoint measures clinical benefit related to improvement in how patients feel, function, or survive [12]. A key difference between an outcome and an endpoint is that researchers must be able to clearly identify if endpoints were affected.

Endpoints should include a method for documenting how often the measurement takes place and the statistical plan to determine a treatment benefit, as reflected in the study protocol [9]. Examples of digital endpoints that have been submitted by industry sponsors of new medical products are shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

Example of how a variety of clinical endpoints can be used to evaluate a measure and determine whether the intervention being studied is beneficial [22].

The importance of identifying meaningfulness to patients during industry-sponsored trials of new medical products is illustrated by FDA guidance regarding developing drugs for the acute treatment of migraine. In this regulatory guidance, sponsors are advised to develop a co-primary endpoint that best aligns the study outcome with the symptom(s) of primary importance to patients [13].

This Framework Applies Broadly

All measures of health should be meaningful, regardless of the product's regulatory classification, type of measure, or context of use.

Whatever the regulatory status of a digital measurement product, it is essential that it assesses outcomes that reflect the MAH and simplified COI identified as meaningful to the target population. Digital measurement products may:

sit outside regulatory oversight in general health and wellness [14];

be regulated as medical products, such as mobile medical applications [15] or Software as a Medical Device [16].

be developed as drug development tools [17] such as electronic clinical outcome assessments [7] or digital biomarkers [7].

In all cases, developers and clinical users should work with patients and their representative groups to ensure measurements are meaningful for the intended population [5].

The framework applies to both direct measures of how patients feel or function (clinical outcome assessment), and measures of normal biological or pathogenic processes (biomarkers) [1]. Even though measurements of biological or pathological processes are not direct measurements of patients' feelings or functions, they should correlate with outcomes that matter [18].

Meaningfulness matters in clinical care and clinical research environments. Both clinicians and researchers should assess elements of daily life that are most impacted by the disease from the patient perspective. Improvements in blood tests or a decrease in tumor size on an MRI are powerful measures assessing the pathophysiology of a disease. However, if the patient remains unable to function in ways that allow them to live the lives they want, or if they do not feel better, the improvements did not translate in ways that are perceived as improved or enhanced quality of life by the patient.

Why Meaningfulness Matters

Digital measures offer the promise of transforming how we define health and how we evaluate the impact of interventions, from therapies in development to care in practice. To ensure that digital measures realize this potential, prioritizing resources towards measures that are most meaningful to patients is critical. We strongly recommend that stakeholders develop strategies to engage early and more continuously with broader patient groups. As a first step, the Digital Medicine Society (DiMe) is compiling a patient directory for release later this year to remove some of the barriers to connection and collaboration between patients, researchers, and trial sponsors.

Prioritizing the identification and development of digital measures that are most meaningful to patients will likely broaden acceptance and adoption of digital measurement in healthcare and health research. Currently, there is a wide array of digital measures being developed across technologies, therapeutic areas, use cases, and populations [19, 20, 21, 22]. If this trend continues, disjointed and unfocused measure development will complicate interpretation and comparison of results, inhibiting the development of strong bodies of evidence supporting digital measures in the service of health.

There is no place for technological determinism in patients' lives. In other words, we have to lead with the patient perspective and not technology solutions when selecting measurements. This four-tier framework is already well established and should be foundational to measurement in digital medicine. This framework should be used across the full spectrum of digital measures, regardless of regulatory status. In Figure 4, we illustrate the framework in full and highlight a sample of patient considerations that should drive measure selection and development.

Fig. 4.

Developing measures that matter to patients. This figure was adapted from original work by Evidation Health, with permission. This figure illustrates patient considerations that should drive digital measure selection and development. These should precede technical considerations [8]. Additional information on subsequent technical considerations are available at [35, 36, 37].

Patients and their care partners should be active participants engaged throughout the selection and development of every digital measure. To support this effort, we recommend that developers, clinicians, and researchers reevaluate processes for more continuous patient engagement during measure development and selection in clinical care and research. It is critical that patient engagement with respect to the development and selection of digital measures be recognized as distinct from usability testing of the measurement technologies. Building upon principles previously described by the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative [5, 23], Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute [24], Meharry Vanderbilt Alliance [25], and the FDA's Voice of the Patient Reports from patient-focused drug development [26], we must develop and test a framework that advances the science of high-quality, continuous patient engagement in the development, deployment, and interpretation of digital measures of health.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no disclosures to report.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources to disclose.

Author Contributions

C.M., B.P.-L., and J.G. made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. C.M., B.P.-L., and J.G. drafted this work and revised it critically for important intellectual content. C.M., B.P.-L., and J.G. gave final approval of the version to be published. C.M., B.P.-L., and J.G. agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Noel Benedetti for support in developing the figures.

References

- 1.FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) Resource [Internet] Silver Spring (MD): Food and Drug Administration (US); 2016. Glossary. 2016 Jan;28 [Updated 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338448/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FDA CDER Patient-Focused Drug Development. 2020 Apr;21 Available in: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/cder-patient-focused-drug-development. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapter 57. In. Kraus WE. Heart Failure: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease. Exercise in Heart Failure; 2011. pp. 834–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoindre Y, Meune C, Dinh-Xuan AT, Avouac J, Kahan A, Allanore Y. Lack of specificity of the 6-minute walk test as an outcome measure for patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2009 Jul;36((7)):1481–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081221. Available in: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19487260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CTTI Use Cases for Developing Novel Endpoints Generated Using Mobile Technology: Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. 2020. Mar, Available in: https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/files/usecase-duchenne.pdf.

- 6.Lake BP. Slide credit to @DoctorSwig during the @PFFORG Summit. It's time for objective measures that better assess how patients feel, function and survive so we can inform treatment selection a and shared decision making. Twitter. 2019 Nov;9 Available in: https://twitter.com/BrayPatrickLake/status/1193238806633287684. [Google Scholar]

- 7.FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) Resource [Internet] Silver Spring (MD): Food and Drug Administration (US); 2016. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326791/ [PubMed]

- 8.CTTI Novel Endpoints. (n.d.). Available from: https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/projects/novel-endpoints.

- 9.Walton MK, Powers JH, Hobart J, Patrick DL, Marquis P, Vamvakas S, et al. Clinical Outcome Assessments: Conceptual Foundation–Report of the ISPOR Clinical Outcomes Assessment − Emerging Good Practices for Outcomes Research Task Force DOES THIS HAVE TO BE LABLED AS PART 1. Value Health. 2015 Sep;18((6)):741–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FDA Roadmap to PATIENT-FOCUSED OUTCOME MEASUREMENT in Clinical Trials. (n.d.) Available in: https://www.fda.gov/media/87004/download.

- 11.Coravos A, Goldsack JC, Karlin DR, Nebeker C, Perakslis E, Zimmerman N, Erb MK. Digital Medicine: A Primer on Measurement. Digit Biomark. 2019 May 9;3((2)):31–71. doi: 10.1159/000500413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friends of Cancer Research. Clinical Benefit, Safety, and Toxicity. (n.d.) Available in: https://www.focr.org/clinical-benefit-safety-and-toxicity.

- 13.Migraine FD. Developing Drugs for Acute Treatment Guidance for Industry. 2018. Feb, Available in: https://www.fdanews.com/ext/resources/files/2018/02-15-18-Guidances.pdf?1520798582.

- 14.Goldsack J. Digital Health, Digital Medicine, Digital Therapeutics (DTx): What's the difference? DiMe. 2019 Nov;10 Available in: https://medium.com/digital-medicine-society-dime/digital-health-digital-medicine-digital-therapeutics-dtx-whats-the-difference-92344420c4d5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.FDA Device Software Functions Including Mobile Medical Applications. 2019 Nov;5 Available in: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications. [Google Scholar]

- 16.FDA Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) 2018 Dec;4 Available in: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/software-medical-device-samd. [Google Scholar]

- 17.FDA Drug Development Tools | DDTs. 2019 Jun;6 Available in: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/drug-development-tools-ddts. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biomarker Qualification FD. Evidentiary Framework. 2018 Dec; Available in: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/biomarker-qualification-evidentiary-framework. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perry B, Herrington W, Goldsack JC, Grandinetti CA, Vasisht KP, Landray MJ, et al. Use of Mobile Devices to Measure Outcomes in Clinical Research, 2010–2016: A Systematic Literature Review. Digit Biomark. 2018 Jan-Apr;2((1)):11–30. doi: 10.1159/000486347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byrom B, Rowe DA. Measuring free-living physical activity in COPD patients: Deriving methodology standards for clinical trials through a review of research studies. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016 Mar;47:172–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakker JP, Goldsack JC, Clarke M, Coravos A, Geoghegan C, Godfrey A, et al. A systematic review of feasibility studies promoting the use of mobile technologies in clinical research. NPJ Digit Med. 2019 Jun 6;2:47. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0125-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stat News Goldsack J, Chasse RA, and Wood WA. Digital endpoints library can aid clinical trials for new medicines. 2019 Nov;6 Available in: https://www.statnews.com/2019/11/06/digital-endpoints-library-clinical-trials-drug-development/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.CTTI CTTI Recommendations: Effective Engagement with Patient Groups around Clinical Trials. (n.d.) Available in: https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/files/pgctrecs.pdf.

- 24.PCORI Engagement Tool and Resource Repository for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2019 Sep;16 Available in: https://www.pcori.org/engagement/engagement-resources. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyer AP, Fair AM, Joosten YA, Dolor RJ, Williams NA, Sherden L, et al. A Multilevel Approach to Stakeholder Engagement in the Formulation of a Clinical Data Research Network. Med Care. 2018 Oct;56((10 Suppl 1)):S22–S26. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FDA The Voice of the Patient: Series of Reports from FDA's Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative. 2019 Nov;13 Available in https://www.fda.gov/industry/prescription-drug-user-fee-amendments/voice-patient-series-reports-fdas-patient-focused-drug-development-initiative. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris R, Martini DN, Smulders K, Kelly VE, Zabetian CP, Poston K, et al. Cognitive associations with comprehensive gait and static balance measures in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019 Dec;69:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larkin L, Nordgren B, Purtill H, Brand C, Fraser A, Kennedy N. Criterion Validity of the activPAL Activity Monitor for Sedentary and Physical Activity Patterns in People Who Have Rheumatoid Arthritis. Phys Ther. 2016 Jul;96((7)):1093–101. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20150281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams JL, Dinesh K, Xiong M, Tarolli CG, Sharma S, Sheth N, et al. Multiple Wearable Sensors in Parkinson and Huntington Disease Individuals: A Pilot Study in Clinic and at Home. Digit Biomark. 2017;1:52–63. doi: 10.1159/000479018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigues R, Ferraz RB, Kurimori CO, Guedes LK, Lima FR, de Sá-Pinto AL, et al. Low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction increases muscle function, mass and functionality in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020 Jun;72((6)):787–797. doi: 10.1002/acr.23911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrzejewski KL, Dowling AV, Stamler D, Felong TJ, Harris DA, Wong C, et al. Wearable Sensors in Huntington Disease: A Pilot Study. A Pilot Study. J Huntingtons Dis. 2016 Jun 18;5((2)):199–206. doi: 10.3233/JHD-160197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. ClinicalTrials.gov A Dose Escalation Study to Assess the Safety and Efficacy of Pulsed iNO in Subjects With Pulmonary Fibrosis. 2020 Jan;14 Available in: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03267108. [Google Scholar]

- 33. ClinicalTrials.gov Clinical Study of BYM338 for the Treatment of Unintentional Weight Loss in Patients with Cancer of the Lung or the Pancreas. 2016 Mar;2 Available in: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01433263?term=NCT01433263&draw=2&rank=1. [Google Scholar]

- 34. ClinicalTrails.gov Effect of Aclidinium/Formoterol on Lung Hyperinflation, Exercise Capacity and Physical Activity in Moderate to Severe COPD Patients (ACTIVATE) 2018 Oct;9 Available in: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02424344. [Google Scholar]

- 35.CTTI Digital Health Technologies. (n.d.). Available in: https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/projects/digital-health-technologies.

- 36.Goldsack JC, Coravos A, Bakker JP, Bent B, Dowling AV, Fitzer-Attas C, et al. Verification, analytical validation, and clinical validation (V3): the foundation of determining fit-for-purpose for Biometric Monitoring Technologies (BioMeTs) NPJ Digit Med. 2020 Apr;3((1)):55. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-0260-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coravos A, Doerr M, Goldsack J, Manta C, Shervey M, Woods B, et al. Modernizing and designing evaluation frameworks for connected sensor technologies in medicine. NPJ Digit Med. 2020 Mar;3((1)):37. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-0237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]