Abstract

Endometrial cancer is the only gynecological cancer that is rising in incidence and associated mortality worldwide. Although most cases are diagnosed as early stage disease, with chances of cure after primary surgical treatment, those with advanced or metastatic disease have a poor prognosis because of the quality of treatment options that are currently available. Mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient cancers are susceptible to programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors. The US Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for MMR-deficient tumors, the first tumor-agnostic approval for a drug. We present a case of stage IV endometrioid endometrial carcinoma with isolated PMS2 protein loss, in which treatment with first-line pembrolizumab therapy achieved a complete clinical and pathological response of tumor.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, Mismatch repair proteins, Checkpoint inhibitors, Microsatellite instability, Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome

Introduction

Endometrial carcinomas of endometrioid type are more frequent than the non-endometrioid type of carcinoma, and extremely heterogeneous in terms of prognosis. Surgical staging is the most important prognostic factor and the guide for adjuvant treatment [1]. Stage IV endometrial cancer is a disease with poor prognosis, with 5-year overall survival ranging from 17 to 30%, despite the quality of multimodality therapy available, which includes radical cytoreductive surgery, combined radiation therapy, and chemotherapy [1, 2].

In The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), endometrial cancer is stratified into four distinct prognostic groups according to the associated molecular profile, based on the results of integrated genomic and proteomic analyses, including measurements of somatic mutation frequency, copy numbers alterations, and microsatellite instability [3]. Endometrial cancer with microsatellite-instability (MSI) accounts for 15–30% of endometrial cancers and is associated with immune activation. Affected patients may therefore be candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, such as anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibodies [4].

On May 23, 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated tissue agnostic approval for pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co), an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, for patients with unresectable or metastatic, microsatellite instable-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient solid tumors that have progressed on prior therapy and for which there are no satisfactory treatment options [5].

Here, we present a case of stage IV endometrioid endometrial carcinoma with PMS2 protein loss, treated with first-line pembrolizumab therapy that achieved a complete clinical response and near-complete pathological response.

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman, gestation 2, presented in April 2018 with a diagnosis of endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium, FIGO grade 3. The diagnosis had been based on the results of endometrial biopsy indicated because of abnormal vaginal bleeding and suspicion of endometrial polyp. On physical examination, the patient was in good condition, with a body mass index of 19.6. Her family history included a brother who developed a colon cancer at age 32 and a maternal grandmother who had a gynecological cancer at the age of 70 years.

The review of the endometrial biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of endometrioid endometrial carcinoma, FIGO grade 3. The histological examination revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, extensively necrotic, with 75% solid areas, 25% villoglandular architecture, and foci of squamous differentiation. Nuclear pleomorphism was high, with numerous mitosis, including atypical figures. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes accounted for 15% of the stroma tumor and were associated with an intraepithelial component.

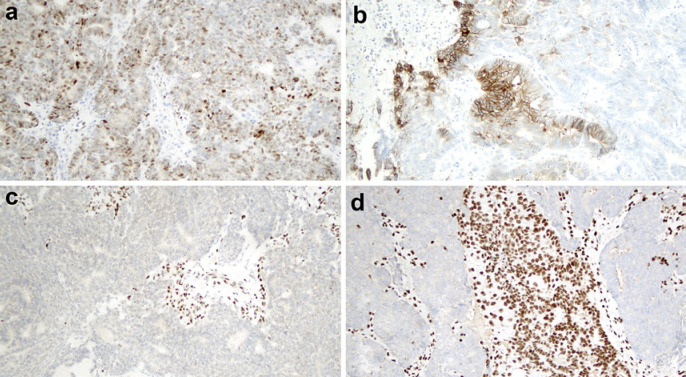

Immunohistochemistry showed neoplastic cells that were positive for estrogen receptor (<5%), vimentin, p63 (30%), CDX2, p16 (diffuse, nuclear and cytoplasmic staining), and synaptophysin (isolated cells). Immunohistochemistry staining was negative for progesterone receptor, napsin A, HNF1B (hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 homeobox B), and chromogranin. Staining for TP53 tumor suppressor gene product (clone DO-7) was of wild type, with weak to moderate expression in 35% of the neoplastic cells (Fig. 1a). Staining for PMS2 protein was negative in neoplastic cells and positive in stroma (Fig. 1c). Staining for MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 proteins was positive. L1CAM (the L1 cell adhesion molecule) was expressed in 15% of neoplastic cells (Fig. 1b). ARID1A (AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A) expression was lost in 30% of neoplastic cells (Fig. 1d). Immunohistochemistry also revealed a non-nuclear expression of catenin beta, wild type.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemistry of the neoplasia. a Wild-type p53, with weak/moderate staining in 35% of neoplastic cells. b The membranes of more than 10% of cells stained positively for L1-CAM positive. c Staining for PMS2 was negative in neoplastic cells and positive in stroma cells. d Loss of ARID1A in neoplastic cells.

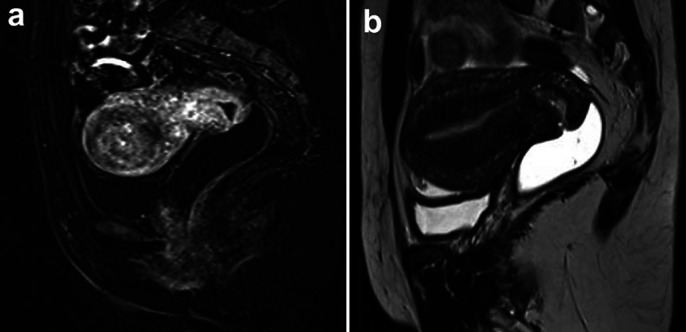

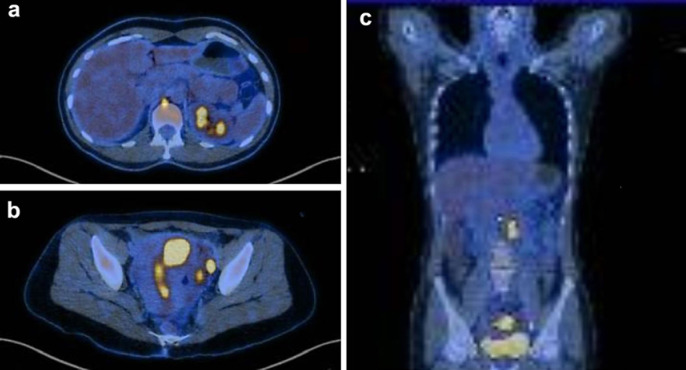

Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a 4-cm tumor located in the uterine fundus, which had infiltrated the myometrium and extended to serosa, beyond the left fallopian tube, and adjacent peritoneal fat (Fig. 2a). There were enlarged iliac and retroperitoneal para-aortic lymph nodes suggestive of neoplastic involvement. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-18F positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) demonstrated intense FDG uptake (SUV = 38.3) in expansive lesion affecting the uterus. Several lymph nodes, some of which displayed enlargement, were observed in the external iliac (SUV max = 29.3), interaortocaval (SUV max = 12.6), left para-aortic (SUV = 21.2), right retrocrural (SUV = 7.7), and thoracic periesophageal chains (SUV = 16.2) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging. a Pretreatment image with a 4-cm tumor located in the uterine fundus, infiltrating the organ wall to the serosa, extending to the left fallopian tube and a nodule in adjacent peritoneal fat. b After 3 cycles of pembrolizumab.

Fig. 3.

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-18F PET-CT pretreatment. a Lymph nodes at right retrocrural (SUV = 7.7) and thoracic periesophageal chains (SUV = 16.2). b External iliac (SUV max = 29.3). c Expansive uterine lesion FDG (SUV = 38.3), interaortocaval (SUV max = 12.6) and left para-aortic lesions (SUV = 21.2), as visualized on FDG.

FoundationOne CDx assay was performed on tumor sample and showed high microsatellite instability and intermediate Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) (13 muts/Mb). There were 19 genomic findings: MTOR (C1483Y), PTCH1 (Y1316 fs*56), PTEN (K269 fs*28, R130*), APC (G471 fs*27, S1465 fs*3), ARID1A (F2141 fs*59), BCORL1 (P1681 fs*20), CTCF (T204 fs*26), MAGI2 (M986I), MLH1 (splice site 117-11_153del48), MLL2 (splice site 4693+1 G > C), PIK3R2 (G373R), RB1 (M484 fs*8, splice site 861+2T > A), SPTA1 (K1125 fs*3), and TAF1 (G365D-subclonal).

The patient was treated with intravenous pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck & Co) at a dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks.

After 3 cycles of pembrolizumab, the uterine lesion completely regressed (Fig. 2b). PET-CT no longer demonstrated anomalous uptake in the iliac, para-aortic, retrocrural, or periesophageal lymph nodes. To evaluate the pathological response, the patient underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, omentectomy, and inventory of the peritoneal cavity. There was no macroscopic evidence of disease. The right retrocrural and thoracic periesophageal lymph nodes were not dissected. Pathological examination of the surgical specimens showed no residual neoplasia in the uterus. Histological signs of complete tumoral regression (fibrosis, edema, histiocytes, lymphoid aggregates, hemorrhage organizing, and endothelial hyperplasia) were seen in endometrium, myometrium, cervix, uterine serosa, left ovary, and adipose tissue in adhering to the uterine fundus. Forty-one lymph nodes (17 pelvic, 23 para-aortic, and 1 omental) were dissected. A micrometastasis of 3.0 mm was identified in one right pelvic lymph node, and an aggregate of isolated tumor cells (diameter 0.2 mm) with signs of partial regression was present in one para-aortic lymph node. Signs of complete tumoral regression were identified in another 3 lymph nodes (1 left pelvic and 2 para-aortic).

The patient has completed 24 months without evidence of progression of disease and without adverse effects.

Genetic Evaluation

The patient was referred to a genetic counselor for risk assessment. The patient reported a family history that included a brother with colon cancer at the age of 32 years and a maternal grandmother with gynecological cancer at the age of 70 years. It is important to note that the maternal family history was limited, as the patient's mother was the only child. After receiving pre-test genetic counseling, the patient was tested for a next-generation sequencing cancer panel that included all MMR genes. A genetic variant was identified in MLH1 gene c.193 G > A (p.Gly65Ser) and classified by a CLIA-certified lab as of uncertain significance (VUS). This classification was based on American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines and the laboratory pipeline. The laboratory reported that the variant has 3.5 points for pathogenic classification (a minimum of 4 points are needed to be classified as probably pathogenic). This variant has no entry in ClinVar. Post-test genetic counseling was provided, and the patient was informed about the possibility that this variant may be reclassified as likely pathogenic, which would confirm a diagnosis of Lynch syndrome.

Discussion

Cancer is among the leading causes of death worldwide. The number of new cases of corpus uterine cancer in 2018 was 382,069; the number of related deaths was 89,929 [6]. The highest rates occur in North America (20.5 per 100,000), while South America presented only 6.9 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [6]. While the incidence of cervical cancer is declining, particularly in most developed countries, endometrial cancer is the only gynecological malignancy with a rising incidence and associated mortality. Apart from a genetic predisposition, obesity is an important risk factor for endometrial carcinoma. The fraction of all corpus uterine cancers attributable to excess body mass index is 37.1% in Brazil and 48.3% in the US [6]. We must be prepared for the management of this growing number of endometrial carcinoma cases.

TCGA study of endometrial cancer identified four categories of tumors: POLE ultramutated, microsatellite instability hypermutated, copy number low/microsatellite stable, and copy number high [3]. These four categories are differentiated in the Proactive Molecular Risk Classifier for Endometrial Cancer (ProMisE), which uses the results of immunohistochemistry for MMR proteins and sequencing of the POLE exonuclease domains [7]. Tumors are classified as POLE mutant, MMR-deficient, p53 wild-type, or p53 abnormal, which are surrogates for the TCGA categories of POLE ultramutated, microsatellite instability hypermutated, copy number low/microsatellite stable, and copy number high, respectively.

The MMR-deficient group corresponds to tumors with the loss of proteins expression secondary to either germinative or somatic mutations, generally in the genes for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. The MMR system is an essential mechanism for maintaining genome integrity in organisms. MMR deficiency results in greatly increased rates of spontaneous mutation with consequent microsatellite instability and predisposition to cancer development. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, or Lynch syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by germline mutations in MMR genes. Endometrial cancer is the second most common manifestation of this disease. Apart from its role in classification of molecular subtype, MMR deficiency analysis is recommended for all endometrial cancers, because a significant percentage of women with Lynch syndrome will present with an endometrial cancer as their initial manifestation of cancer [8]. The ultimate diagnosis of Lynch syndrome requires documentation of a mutation within one of the four MMR genes (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6) or EPCAM, currently achieved with comprehensive sequencing analysis of germline DNA. Immunohistochemistry for MMR proteins can be performed to screen patients with endometrial cancer for Lynch syndrome [9].

MMR proteins are stable only as heterodimers: MLH1 pairs with PMS2; MSH2 pairs with MSH6. Considering that PMS2 and MSH6 only dimerize with MLH1 and MSH2, respectively, some recommend the immunohistochemistry analysis only for PMS2 and MSH6, which become unstable when protein expression of MLH1 or MSH2, respectively, is lost [8]. However, our case presented only the loss of PMS2 expression, a finding reported in 7% of endometrial carcinomas with MMR deficiency [10]. The management of patients with this finding, for purposes of screening for Lynch syndrome, must include MLH1 analysis if no mutations are detected through PMS2 testing, because approximately 24% of patients harbor germline MLH1 mutations not detected by immunohistochemistry [10].

Apart from its role in screening for Lynch syndrome, MMR protein testing is a prognostic classifier that may be used to guide adjuvant treatment [9].

MMR plays an important role in editing DNA mismatches that occur during replication and in recombination repair. MMR defects increase the rate of mismatch errors, resulting in microsatellite instability and, consequently, abnormal proteins that activate the immune system. Yamashita et al. [4] identified a loss of MMR proteins in 42/149 (28.2%) patients with endometrial cancer. The group of patients with MMR defects presented higher levels of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and PD-L1/PD-1 expression, suggesting that MSI may be a biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors. In our case, besides alterations in MLH1 (splice site 117-11_153del48), Foundation One detected high MSI.

Previous work has shown that pembrolizumab has durable antitumor activity in patients with locally advanced or metastatic PD-L1-positive endometrial cancer that has not responded to treatment [11]. However, responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors are observed regardless of the status of PD-L1, as in the recent case reported by Takeda et al. [12] and in their literature review, which included 7 cases of endometrial carcinoma successfully managed by pembrolizumab. The approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of all solid tumors with defective DNA MMR could benefit a significant portion of patients with advanced endometrial cancer. However, patients respond to treatment in different ways. For example, in a study of endometrial carcinoma, Sloan et al. [13] found that PD-L1 expression was more common in tumors from patients with MMR deficiency associated with Lynch syndrome than in those with MLH1 promoter hypermethylation or MMR-intact tumors, suggesting differences in the benefits afforded by PD-1/PD-L1 drugs. These findings indicate that not all tumor neoantigens generated by MSI are antigenic [14] and additional information on the pathological and genomic features of MMR deficient tumors may facilitate the search for an effective immunotherapy. Our case presented an extraordinary response and several characteristics aside from MSI-H that suggest immune activation. The tumor presented lymphocyte infiltration of the stroma and neoplasia, suggesting lymphocyte mobilization. The tumor was poorly differentiated, high-grade, with high mitotic index and atypical mitosis, carrying a high neoantigen load that elicited the recruitment and activity of cytotoxic lymphocytes, and, consequently, the expression of PD-L1/PD-1. The tumor also presented a loss of ARID1A expression. ARID1A encodes a member of the SWI/SNF (switch/sucrose non-fermentable) chromatin remodeling complex, and there is an association between ARID1A loss and sporadic MSI [15]. Although the loss of ARID1A is associated with MLH1 silencing, which was not demonstrated in our case, it interacts with several other proteins, some of which are involved in DNA repair and genomic stability [15]. Foundation One testing revealed alterations in 19 genes, most of which act as tumor suppressors.

Conclusion

An approach to risk stratification based on a combination of molecular and clinical-pathological data can improve the quality of treatment decisions. Routine immunohistochemical testing of MMR-related proteins should be performed in all patients with endometrial cancer. Understanding the prognostic relevance of MMR deficiency in endometrial cancer is an important first step in working to identify effective treatment strategies. Pembrolizumab is a promising first-line agent for treatment of some types of endometrial cancer. Current trials of immune checkpoints inhibitors therapies for endometrial cancer are limited to stage III or IV disease, and recurrent/metastatic tumors that have not responded to prior therapy. The enrollment of patients into clinical trials of first-line immunotherapy regimens should be considered to save time in serious cases like the one presented here.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by the Research Committee of Hospital Sirio Libanes (Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil) (approval No. 1746) and registered on the Plataforma Brasil (CAAE 31530120.9.0000.5461). The study complies with the ethical precepts proposed by the legislation in force in Brazil (R466/2012). The patient signed the written informed consent to use and publish the patient's data, case details, and images for study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the work. J.P.C. was the surgeon, M.I.A. the genetic counselor, A.D.G. the oncologist, and F.M.C. the pathologist of the case. J.P.C. and F.M.C. were responsible for drafting the work and all of them revised and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Colombo N, Creutzberg C, Amant F, Bosse T, González-Martín A, Ledermann J, et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO Consensus Conference on Endometrial Cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016 Jan;27((1)):16–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galaal K, Al Moundhri M, Bryant A, Lopes AD, Lawrie TA. Adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 May;((5)):CD010681. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010681.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kandoth C, Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013 May;497((7447)):67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamashita H, Nakayama K, Ishikawa M, Nakamura K, Ishibashi T, Sanuki K, et al. Microsatellite instability is a biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors in endometrial cancer. Oncotarget. 2018 Jan;9((5)):5652–64. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasad V, Kaestner V, Mailankody S. Cancer Drugs Approved Based on Biomarkers and Not Tumor Type-FDA Approval of Pembrolizumab for Mismatch Repair-Deficient Solid Cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Feb;4((2)):157–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferlay J, Ervik M, FL, MC, LM, MP, et al. Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, Yang W, Lum A, Senz J, et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: A simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer. 2017 Mar;123((5)):802–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crosbie EJ, Ryan NAJ, Arends MJ, Bosse T, Burn J, Cornes JM, et al. The Manchester International Consensus Group recommendations for the management of gynecological cancers in Lynch syndrome. Genet Med. 2019 Oct;21((10)):2390–400. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0489-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stelloo E, Jansen AML, Osse EM, Nout RA, Creutzberg CL, Ruano D, et al. Practical guidance for mismatch repair-deficiency testing in endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017 Jan;28((1)):96–102. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudley B, Brand RE, Thull D, Bahary N, Nikiforova MN, Pai RK. Germline MLH1 Mutations Are Frequently Identified in Lynch Syndrome Patients With Colorectal and Endometrial Carcinoma Demonstrating Isolated Loss of PMS2 Immunohistochemical Expression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015 Aug;39((8)):1114–20. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ott PA, Bang YJ, Berton-Rigaud D, Elez E, Pishvaian MJ, Rugo HS, et al. Safety and Antitumor Activity of Pembrolizumab in Advanced Programmed Death Ligand 1-Positive Endometrial Cancer: Results From the KEYNOTE-028 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug;35((22)):2535–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.5952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda A, Koike W, Watanabe K. Rapid regression of microsatellite instability-high/programmed cell death ligand 1-negative recurrent endometrial carcinoma by immune checkpoint blockade with pembrolizumab: A case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2020 May;32:100553. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2020.100553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloan EA, Ring KL, Willis BC, Modesitt SC, Mills AM. PD-L1 Expression in Mismatch Repair-deficient Endometrial Carcinomas, Including Lynch Syndrome-associated and MLH1 Promoter Hypermethylated Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017 Mar;41((3)):326–33. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viale G, Trapani D, Curigliano G. Mismatch Repair Deficiency as a Predictive Biomarker for Immunotherapy Efficacy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4719194. doi: 10.1155/2017/4719194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosse T, ter Haar NT, Seeber LM, v Diest PJ, Hes FJ, Vasen HF, et al. Loss of ARID1A expression and its relationship with PI3K-Akt pathway alterations, TP53 and microsatellite instability in endometrial cancer. Mod Pathol. 2013 Nov;26((11)):1525–35. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]