Abstract

Gene editing approaches using CRISPR/Cas9 are being developed as a means for targeting the integrated HIV-1 provirus. Enthusiasm for the use of gene editing as an anti-HIV-1 therapeutic has been tempered by concerns about the specificity and efficacy of this approach. Guide RNAs (gRNAs) that target conserved sequences across a wide range of genetically diverse HIV-1 isolates will have greater clinical utility. However, on-target efficacy should be considered in the context of off-target cleavage events as these may comprise an essential safety parameter for CRISPR-based therapeutics. We analyzed a panel of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) gRNAs directed to the 5′ and 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR) regions of HIV-1. We used in vitro cleavage assays with genetically diverse HIV-1 LTR sequences to determine gRNA activity across HIV-1 clades. Lipid-based transfection of gRNA/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins was used to assess targeting of the integrated HIV-1 proviral sequence in cells (in vivo). For both the in vitro and in vivo experiments, we observed increased efficiency of sequence disruption through the simultaneous use of two distinct gRNAs. Next, CIRCLE-Seq was utilized to identify off-target cleavage events using genomic DNA from cells with integrated HIV-1 proviral DNA. We identified a gRNA targeting the U3 region of the LTR (termed SpCas9-127HBX2) with broad cleavage efficiency against sequences from genetically diverse HIV-1 strains. Based on these results, we propose a workflow for identification and development of anti-HIV CRISPR therapeutics.

Keywords: Cas9, CRIPSR, HIV-1, HIV-1 LTR, off-target analysis

Introduction

The development of RNA-guided endonucleases, including CRISPR/Cas9, for targeted cleavage of genomic DNA within eukaryotic cells has provided a potential means of achieving the removal of integrated DNA derived from viral pathogens.1,2 CRISPR/Cas9 gene disruption uses a guide RNA (gRNA) sequence that is complementary to an ∼20 base pair (bp) target DNA sequence, together with the Cas endonuclease, to bind to and then cleave the target DNA region. For Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) to efficiently cleave double-stranded DNA, the target sequence to which the gRNA binds must be located 5′ to the “N-G-G” nucleotide sequence that is termed the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM).3

Once cleaved by Cas9, endogenous cellular DNA repair mechanisms, most prominently nonhomologous end joining, act on the double-stranded breaks, and, through error-prone repair mechanisms, can introduce small substitutions, insertions or deletions (indels). Large deletions or insertions can also be achieved through the introduction of two or more double-stranded breaks.

In designing gRNA sequences to viral pathogens, it is critically important to confirm that the gRNA lacks complementarity to normal cellular genes, especially those that are important for cell growth, viability, and metabolism. CRISPR-based therapeutics can target viral gene sequences that are either integrated into the host cell genome as in the case of HIV-1, or present in an extrachromosomal body such as the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) of the hepatitis B virus.4

Antiviral CRISPR therapeutic approaches also include the manipulation of the host genome to improve immunity or resistance to viral infection.5–8 In the case of HIV-1, multiple groups have explored strategies to enhance HIV-1 resistance, most significantly by disrupting the chemokine receptors CCR5 or CXCR4 required for viral binding and internalization, in addition to using approaches that inactivate or delete the HIV-1 provirus.9,10

The predominant HIV-1 Major (M) group comprises multiple clades that are genetic subtypes that vary in sequence within several areas of the HIV-1 genome, including the long terminal repeat (LTR), as well as the env (envelope) and gag (group antigen) genes. There are currently 14 M group clades (A1, A2, A3, A4, A6, B, C, D, F1, F2, G, H, J, and K) and 97 reported circulating recombinant forms (CRFs).11

Individual subtypes predominate within distinct geographic areas due, in part, to the high HIV-1 mutation rate and geographical constraints during HIV-1 transmission. Knowledge about the geographical distribution of HIV-1 subtypes can inform the selection of specific guides for each region. For example, HIV-1A is common in East Africa, while HIV-1B is the dominant form in Europe and the Americas. In Asia, HIV-1A dominates in Russia, HIV-1C is predominant in India, and numerous CRFs are found across the continent, especially in China.12,13 This genetic variability makes the design of both vaccines and virus-specific CRISPR-based therapies with universal clinical applicability especially challenging because of the large distribution of HIV-1 subtypes, CRFs, and unique recombinant forms. Thus, the identification and surveillance of the various molecular strains of HIV remain critical for therapeutics that target genetic elements of this virus.13

One approach to identify potential target sites is to focus only on the most conserved regions of the HIV-1 provirus. An alternate method is to design gRNAs with the goal of excising the majority of the proviral genome and, secondarily, constrain guide selection by relative conservation of sequences within potential target regions and empirically test efficacy against multiple HIV-1 clades.

In this report, we compared the cleavage efficacy of a panel of SpCas9 gRNAs targeting the proviral LTR region both in vitro and in cells. We assessed the applicability of this panel of guides for targeting the LTR regions from disparate clades of HIV-1. We subjected genomic DNA containing integrated HIV-1 provirus to CIRCLE-Seq analysis14 to quantify specific on-target events, as well as to identify off-target cleavage events within genomic DNA. We found a high degree of specific HIV-1 proviral DNA cleavage with several single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), which in some cases was increased when two different guides were used together. Moreover, we found that a particular guide we designed was able to cleave the 3′ HIV-1 LTR region from multiple HIV-1 clades. CIRCLE-Seq analyses revealed few predicted off-target events.

These findings underscore the importance of testing gRNAs against different targets to identify broadly conserved regions among genetically disparate HIV-1 sources, and to confirm lack of off-target events in nontargeted regions. Finally, we propose an anti-HIV-1 guide nomenclature to standardize the naming and identification of gRNAs developed by various investigators.

Materials and Methods

Identification of gRNA sequences to the HIV-1 provirus

To develop gRNA candidates for HIV-1 excision, we first utilized in silico approaches to identify regions that could serve as SpCas9 targets. Two methods were used to identify candidate gRNA target sequences. The first method searched for possible target regions in the pNL4-3 HIV 5′ LTR15 by scanning for the Cas9 PAM (NGG) using Gene Construction Kit software (Textco BioSoftware, Raleigh, NC), and then testing each of the adjacent 20 bp sequences for unintended homologies to human genomic DNA using Blast from the National Center for Biotechnology Information's website.16

Using this process, the U3B gRNA (SpCas9-278+HXB2) was identified, and subsequently cloned by the Gibson method17,18 (Cat. No. E2611S; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA,) into a vector containing the gRNA scaffold under the human U6 promoter (gRNA cloning vector was a gift from George Church, plasmid No. 41824; Addgene; http://n2t.net/addgene:41824: RRID: 41824; Addgene)19).

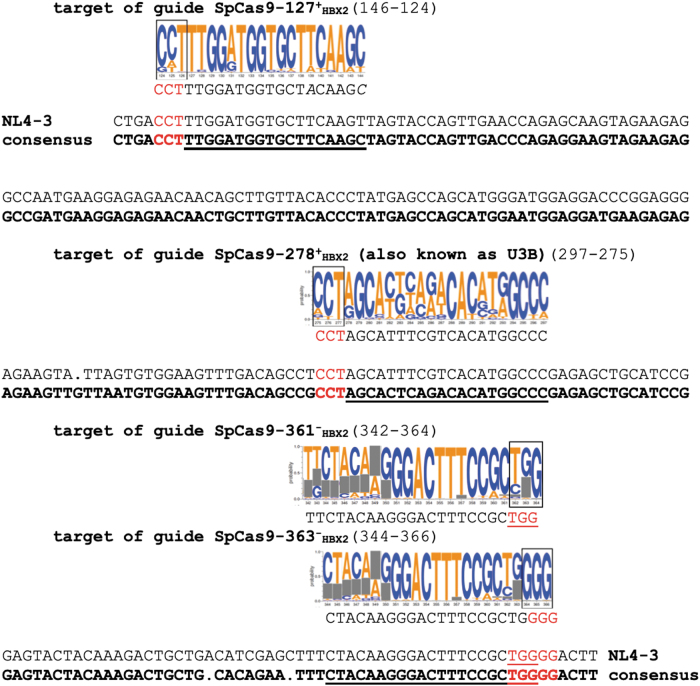

The second method identified gRNA target sequences using Integrated DNA Technologies (IDTdna, Coralville, IA) custom gRNA design link.20 The sequence for the HXB2 5′ LTR region was uploaded into the IDTdna site, and this method identified the gRNAs noted as SpCas9-127+HXB2, SpCas9-361−HXB2, and SpCas9-363−HXB2. The target regions for these gRNAs are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Cas-OFFinder was used to determine the possible number of off-target events (Supplementary Table S1). Conservation of these target regions between HIV-1 isolates was determined using web alignments from the Los Alamos National Laboratory HIV Sequence Database (https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/index). All clades were represented in the 1,242 HIV sequences used (data that were available in 2017). A logo graphical representation of the probability of each nucleotide at its specific base pair position was created (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

U3 region of 5′ LTR sequences. The sequence conservation of the four different target regions for the gRNAs was derived by web alignments using the Los Alamos National Laboratory HIV Sequence Database (https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/index) utilizing 1,242 complete HIV sequences from all clades (available in 2017). The logo for each target region indicates the probability of each nucleotide at a specific position. The PAM sequence is boxed, and gray boxes denote sites of sequence insertions and deletions in multiple clades where alignment is lost, but becomes re-established downstream. The consensus sequence (shown in bold font) from 1,242 analyzed HIV-1 sequences was aligned with the sequence of NL4-3 (GenBank AF324493.2), the source of LTRs in the plasmid used in Figure 2. The target region of the four guides is underlined, and the PAM sequence is in red font. The numbers in parentheses are coordinates with reference to the HIV-1 HXB2 sequence. gRNAs, guide RNAs; LTR, long terminal repeat; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif. Color images are available online.

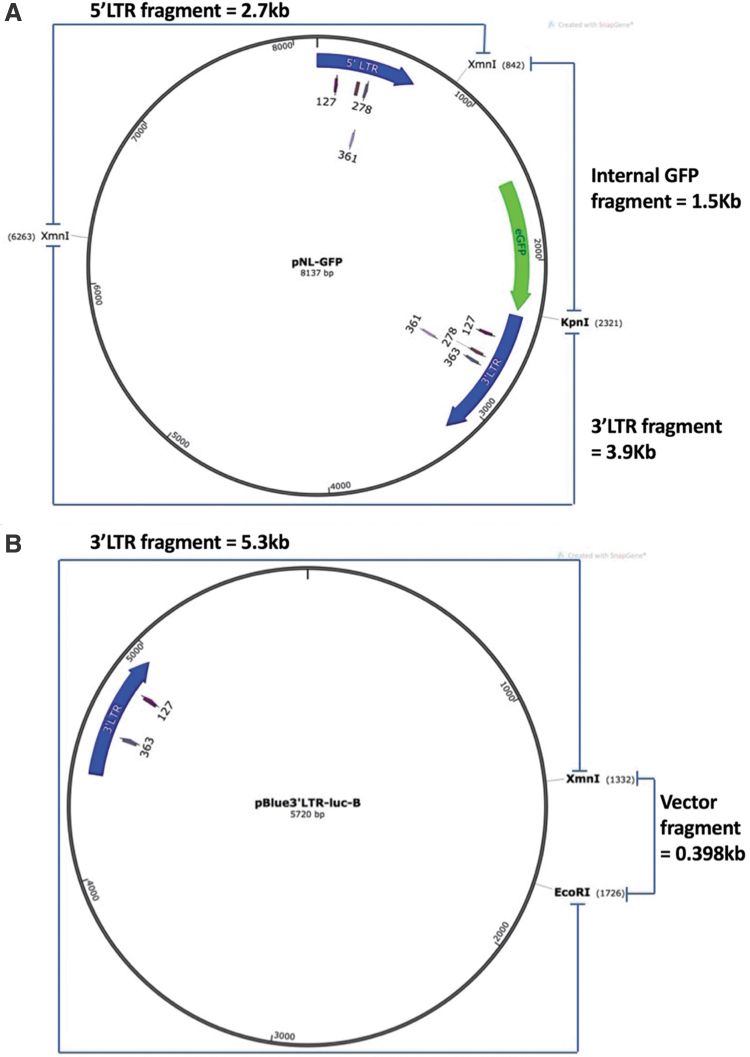

FIG. 2.

Maps of the two plasmids used in the in vitro cleavage assays. (A) Schematic representation of plasmid pNL-GFP with 5′ and 3′ LTRs (HIV-1 LTRs derived from NL4-3, shown as blue arrows) flanking the green fluorescent protein gene (eGFP in green). Noted are the restriction enzyme sites for XmnI and KpnI that cleave the plasmid into three fragments, with the anticipated fragment sizes indicated. Target sites of the LTR guides are noted by the numerical value that represents the nucleotide closest to the PAM. (B) Schematic representation of plasmid pBlue3′LTR-luc-B. This plasmid contains the LAI HIV-1 3′ LTR derived from pBluescript KS(+), shown as a blue arrow. This plasmid was used as the backbone for each clade, interchanging the 3′ LTR to correspond appropriately. Noted are the restriction enzyme sites for XmnI and EcoRI that cleave the plasmid into two fragments, and the target sites of the LTR gRNA 127 and gRNA 363. Color images are available online.

Standardization of gRNA nomenclature

gRNA nomenclature was developed for the SpCas9 gRNAs utilized in this study. The species origin of the Cas enzyme is noted first, followed by the nucleotide position adjacent to the Cas-specific PAM. The orientation of the complementary strand the gRNA binds to is denoted in superscript as being either on the plus(+) strand (5′→3′) or the minus (−) strand (3′→5′). In the case of the gRNAs reported here, the numerical designation of the gRNA refers to the nucleotide position in the HBX2-HIV reference genome (Accession No. K03455.1). The reference genome used is depicted as a subscript notation.

In vitro DNA cleavage assay

We designed several gRNAs with specificity to the HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 1 shows the target sequences, and Fig. 2 shows the sites in pNL-GFP), and tested cleavage efficiency either with a single gRNA or with a combination of two gRNAs. The target plasmid, pNL-GFP (Fig. 2), was derived from pNL4-3 Luc (No. 3418; Addgene)15 by digesting with NsiI and XhoI to remove the majority of the HIV and luciferase sequences. We then reintroduced nuclear localization and splice acceptor sites using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and added the eGFP sequence by PCR from the Clontech plasmid (pEGFP-N1) between the XhoI and KpnI sites. In addition, we tested two different gRNAs against pBluescript KS(+)LTR-luc plasmids expressing various HIV-1 3′ LTRs from HIV-1 clades A through G (Cat. Nos. 4787–4793; NIH AIDS repository).21,22

To test HIV-1 DNA cleavage, the pNL-GFP plasmid was first digested either with combinations of the Kpn1 and Xmn1 restriction enzymes, or the Xho1 and Xmn1 restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs), to yield three fragments (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1). The pBluescript KS(+) plasmids expressing different HIV-1 clades (A–G) were each digested with the combination of the Xmn1 and EcoR1 restriction enzymes to generate two fragments of 6 and 0.4 kb. The in vitro cleavage assay was performed by initially forming a duplex of gRNA and tracrRNA, followed by the addition of recombinant SpCas9 to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. Briefly, the gRNA:tracrRNA duplex was formed by incubating 300 pmoles of gRNA with 300 pmoles of tracrRNA (Alt-R® CRISPR-Cas9 tracrRNA; IDTdna, Coralville, IA) for 5 min at 95°C.

This duplex was then diluted 1:100 with nuclease-free duplex buffer (IDTdna) to a final concentration of 3 μM. For a 30 μL RNP assembly, 1 μL (3 pmoles) of gRNA:tracrRNA duplex was added to 3 pmoles of Cas9 (Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3; IDTdna) together with 3 μL of 10 × Cas9 nuclease reaction buffer (IDTdna). The complexes were incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and then added to 300 ng of the digested plasmid DNA and incubated at 37°C for an additional 15 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 μL of proteinase K (800 units/mL; New England Biolabs) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. To assess cleavage efficiency, the DNA fragments were separated on a 0.9% agarose gel, and visualized with GelRed (Biotium, Fremont, CA) on a Bio-Rad Versa Doc imaging system using Image Lab software (Hercules, CA).

In vivo cleavage of the HIV-1 LTR

TZM-bl cells were used as a model for the in vivo assessment of CRISPR/Cas9 gene cleavage as these cells contain two copies of a modified HIV-1 provirus that express either the luciferase or beta-galactosidase gene.23–27 These cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, and 1 × penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) at 37°C and 5% CO2. A mixture of RNPs containing either one or two different gRNAs to the U3 region of the LTR (gRNA 363 and gRNA127) were transfected into TZM-bl cells using CRISPRmax (CMAX0001; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Control RNPs were prepared using a gRNA to HPRT (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase; IDTdna).

Briefly, RNPs for TZM-bl cells were prepared by mixing 40 pmoles of the gRNA:tracrRNA duplex, 40 pmoles of Cas9, and 3.4 μL of Cas9-plus reagent (total volume equals 83 μL), and incubating for 5 min at room temperature. This RNP was then mixed with 4 μL of CRISPRMax plus 79 μL of OPTI Mem (GIBCO), and incubated for an additional 20 min. The RNP was then added to wells of a 24-well plate, followed by the addition of 8 × 104 TZM-bl cells in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS in a final volume of 0.5 mL. Cells were incubated for 60 h before analysis of gene cleavage.

The loss of functional activity in TZM-bl cells following in vivo cleavage of the HIV-1 LTR was assessed by a luciferase reporter assay. Briefly, TZM-bl cells transfected with RNPs (above) were removed using trypsin following the 60-h incubation, counted, and 1 × 104 cells from each transfection condition plated in triplicate in wells of a 96-well plate. The cells were allowed to attach to the plastic wells overnight, then stimulated with 10 ng/mL of TNF-α for 4 h, washed with 1 × phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed with 25 μL of luciferase cell culture lysis reagent (Promega). The plate containing the cells was placed at −80°C overnight to facilitate lysis and then thawed at room temperature in the dark. Twenty microliters of each lysate was then transferred to 1.5 mL microliter tubes, followed by the addition of 100 μL of Luciferase assay substrate (Promega). The luciferase activity was recorded in a luminometer (Turner Systems 20/20).

T7E1 assay

DNA was isolated from TZM-bl cells using the QIAamp Micro DNA kit (Qiagen, Waltham, MA) following in vivo transfection of RNPs. Genome editing via the CRISPR/Cas9 RNP complex was quantified by the EnGen Mutation detection kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, PCR was performed on genomic DNA flanking the 5′ LTR target site for 35 cycles (98°C, 30 s; 66°C, 20 s; 72°C, 30 s) using Phusion Hi-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), primer pairs (fwd: GGAAGGGCTAATTCACTCCCAA, rev: ACAGGCCAGGATTAACTGCG) at a final concentration of 500 nM, and 50–100 ng of genomic DNA. A 1.083 kb portion of the HPRT gene was amplified using Q5 Hot Start High Fidelity 2 × Master Mix (New England Biolabs), and Alt-R Human HPRT PCR Primer Mix (IDTdna). This PCR was performed for 35 cycles (98°C, 15 s; 67°C, 20 s; 72°C, 30 s).

To complete the assay, PCR products were reannealed (95°C–85°C, 2°C/s; 85°C–25°C, 0.1°C/s) in a final volume of 19 μL using 5 μL of PCR product, 2 μL of 10 × New England Biolabs Buffer 2, and then digested with 1 μL of EnGen T7 endonuclease 1 mutation detection (T7E1) for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by incubating with 1 μL of proteinase K (New England Biolabs) for 5 min at 37°C, and PCR products were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel. DNA bands were visualized with GelRed, and band density was determined as described above. The quantification of gene modification was based on relative band intensity and determined by the following formula: % Gene Modification = 100 × (1-fraction cleaved)1/2 as previously described.28

CIRCLE-Seq

sgRNA synthesis

The gRNAs used for CIRCLE-Seq in vitro cleavage reactions were sgRNAs containing both the target-specific gRNA and the tracrRNA. These were transcribed from a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) template with a T7 promoter using the Engen sgRNA synthesis kit (Cat. No. E3322S; New England Biolabs,) and purified using the Monarch RNA Cleanup kit (Cat. No. T2040L; New England Biolabs,). DNA oligos containing the T7 promoter and target-specific sequence required for synthesis of the dsDNA template were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Cat. No. 10336022).

CIRCLE-Seq library preparation

Genomic DNA was purified from TZM-bl cells using the Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (Cat. No. 158667; input: 1–2 × 107 cells; Qiagen) and sheared using the Covaris S220 acoustic sonicator (Woburn, MA) to an average length of 300 bp according to the manufacturer's protocol. The CIRCLE-Seq protocol was performed largely as previously reported.14

Briefly, sheared genomic DNA was subjected to solid-phase reversible immobilization beads using AMPure XP bead-based double size selection (Cat. No. NC9959336, size range: 200–700 bp; Beckman Coulter, Jersey City, NJ), end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated (Cat. No. KK8235; KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) to a hairpin adapter (oSQT1288; 5′- P-CGGTGGACCGATGATCUATCGGTCCACCG*T-3′, where * indicates phosphorothioate linkage). The ligated, hairpin DNA fragments were treated with a mixture of lambda exonuclease and Escherichia coli exonuclease I (Cat. Nos. M0262L, M0293L; New England Biolabs) to remove DNA with free ends.

Next, adapter-ligated DNA was treated with USER enzyme (Cat. No. M5505L; New England Biolabs) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Cat. No. M0201L; New England Biolabs), generating complementary 3′ overhangs to promote self-ligation and circularization of the DNA fragments. Resulting DNA (500 ng) was circularized overnight with T4 DNA ligase (Cat. No. M0202L; New England Biolabs) and was then treated with Plasmid-Safe ATP-dependent DNase (Cat. No. E3101K; Epicentre, Madison, WI) to remove noncircular DNA fragments before in vitro digestion with gRNA/SpCas9 nuclease (Cat. No. M0386S; New England Biolabs,). Cas9-treated DNA was A-tailed, ligated to the NEBNext adaptor for Illumina® (Cat. No. E7601A; New England Biolabs), USER enzyme-treated, and amplified by PCR using KAPA Hifi polymerase (KK2601; KAPA Biosystems) and NEBNext® Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Cat. No. E7600S). Amplified DNA was subjected to another round of AMPure XP bead-based double-sided size selection.

Completed DNA libraries were quantified by quantitative PCR using the KAPA Library Quant Kit (Cat. No. 07960140001; KAPA Biosystems), Qubit dsDNA quantitation, and sizing on an Agilent Fragment Analyzer before subsequent sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq500 instrument in the Genomics and Molecular Biology Shared Resource at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center Core Facility (Lebanon, NH).

CIRCLE-Seq data analysis

Completed DNA libraries were normalized, denatured, and loaded onto flow cells and sequenced with 150 bp paired end reads on the Illumina NextSeq500 instrument, with ∼5 million sequence read pairs per sample. A modified CIRCLE-Seq pipeline29 was implemented locally on a 10-Core iMac Pro. Briefly, demultiplexed, trimmed, merged, paired end reads were mapped to a custom genome assembly that comprised the human reference genome GRCh37 and HIV-1 HXB2 as a separate chromosome. Matched and unmatched sites were identified using default settings as previously published.14 In brief, read sequences with less than or equal to 6 nucleotide mismatches (including deletions and insertion) to the target (guide)+PAM sequence were identified as off-target sites, while those with greater than six nucleotide mismatches were categorized as unmatched.

Results

In vitro cleavage of the HIV-1 proviral LTR sequence

In vitro cleavage assays were performed to test the specificity and cleavage activity of various gRNAs targeting the HIV-1 LTR sequences present in the pNL-GFP plasmid. Individual gRNAs were complexed with SpCas9 tracrRNA and were combined with recombinant SpCas9 to form RNPs. RNPs were then incubated with restriction enzyme-digested pNL-GFP. Cleavage efficiencies were assessed by monitoring the production and intensity of expected cleavage products visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis.

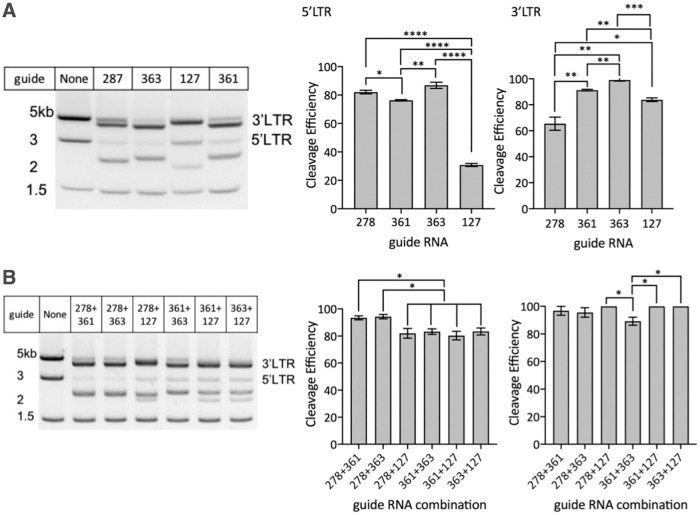

Supplementary Figure S1 and Figure 3A, left panel, depict agarose gel images of target DNA cleavage. The percentage of target region cleaved is depicted in bar graph format (Fig. 3A, middle and right panels) and shows that the gRNAs SpCas9-363−HXB2 (363) and SpCas9-361−HXB2 (361) were the most effective in cleaving both the 5′ and 3′ LTRs, whereas SpCas9-278+HXB2 (278) and SpCas9-127+HXB2 (127) showed disparate cleavage efficiencies of the 5′ and 3′ LTR regions. It is likely that differences in cleavage efficiencies between the 5′ and 3′ LTRs could be attributed to differences in gene sequences at these regions in our target (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3), although we cannot rule out that various gRNA-containing RNPs are inherently more efficient at cleaving target DNA.

FIG. 3.

In vitro analysis of fragmented pNL-GFP cleaved with single or double LTR gRNAs. Left panels: gel images of fragmented pNL-GFP cleaved by (A) single or (B) double LTR guides directed to the 5′ and 3′ LTRs. Right panels: cleavage efficiency of each guide tested was determined for the 5′ and 3′ LTR independently. Data are the mean ± SEM from three experiments and analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001, ****p ≤ .0001. Results show cleavage of pNL-GFP cleaved by one LTR guide (right panel, A) and two LTR guides (right panel, B) at the 5′ and 3′ LTRs. SEM, standard error of the mean.

We next determined whether CRISPR/Cas9 RNPs targeting different regions of the HIV-1 LTR were more efficient at gene cleavage when used in combination compared with single RNPs. As shown in Figure 3B, we found that the use of combinations of gRNAs demonstrated similar or higher cleavage efficiencies when compared with individual gRNAs. For example, the combination of gRNA 278 plus gRNA 361 (93.4% ± 0.6% cleavage), and gRNA 278 plus gRNA 363 (94.3% ± 0.8% cleavage) showed significantly higher target region cleavage at the 5′LTR compared with the other combinations we tested.

In contrast, when quantifying cleavage at the 3′LTR with combinations of gRNAs, all gRNA combinations showed increased cleavage efficiency compared with single gRNAs. The two best guide combinations, gRNA 278 plus 361 (96.8% ± 3.2%), and gRNA 278 plus 363 (95.6% ± 3.4%), had slightly increased cleavage efficiency in the 3′LTR compared with the 5′LTR. This pattern of differential cleavage to the 5′ and 3′ LTRs was consistent for both individual gRNAs as well as combinations of two different gRNAs used simultaneously (cleavage efficiencies ranged from 80% to 100%).

gRNAs to HIV-1 LTRs target HIV-1 clades with variable efficiencies

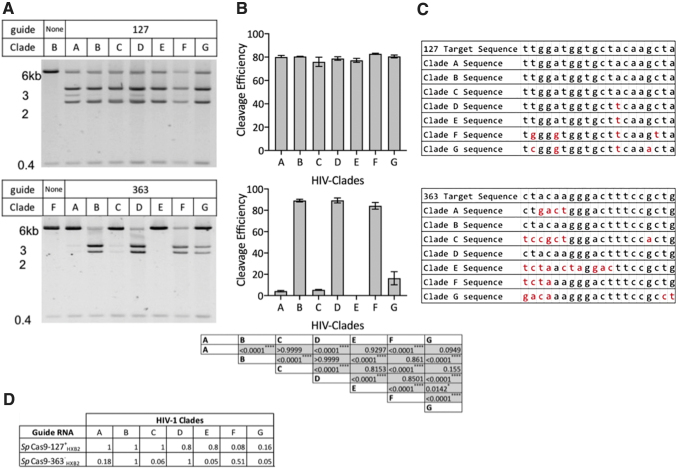

While the activity of each gRNA against a single HIV-1 clade gives some indication of functional activity, the ability to target various LTR sequences should also be assessed. Therefore, we used plasmids containing divergent portions of the 3′ LTRs from HIV-1 clades A through G21 in an in vitro assay similar to that performed above. We tested gRNA 127 because this gRNA had the greatest homology to the target region among all the various clades, as well as gRNA 363 that had the least homology across all of the 3′LTRs of the various clades.

When testing in vitro cleavage, we found that the cleavage efficiencies of these gRNAs correlated with similarities in homology between the target sequence and the gRNAs among the various HIV clades A–G (Fig. 4A–C). Target cleavage was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4A) and the percentage of cleavage efficiency was calculated and is shown in Figure 4B. Figure 4C shows the nucleotide mismatches between gRNA and target DNA, which in some cases were noncontiguous and located both proximal and distal to the PAM. Cutting Frequency Determination (CFD) scores were calculated for each guide using a pairwise comparison with each representative clade sequence to predict the impact of mismatches on cleavage efficiencies (Fig. 4D). This analysis considers the number of mismatches between gRNA and target DNA, the location(s) of the mismatches, the PAM, and the specific nucleotide mismatch.30

FIG. 4.

Cleavage by individual gRNAs of the 3′ LTR from multiple HIV-1 clades. (A) Gel images of gRNA 127 (A, top panel) and gRNA 363 (A, bottom panel) cleavage of the 3′ LTR from pBlue 3′LTR-luc-A through G. (B) Cleavage efficiency of each clade against gRNA 127 (B, top panel) or gRNA 363 (B, bottom panel) was quantified. Data are the mean ± SEM from three experiments and statistical analysis was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD post hoc test. All means were compared with one another. p Values are found in the table for clades cleaved with guide 363; ****p ≤ .0001. No significant differences were found between clades cleaved with gRNA 127. (C) DNA sequence differences (shown in red) between target sequence of gRNA 127 (top) and gRNA 363 (bottom) against the HIV-1 reference sequence, HXB2 (Target sequence). (D) CFD was calculated using Python version 2.749 with packages pickle, re, and NumPy. Original code was obtained from Doench et al.30 ANOVA, analysis of variance; CFD, Cutting Frequency Determination. Color images are available online.

Cleavage efficiencies for gRNA 127 ranged from 76% ± 4% to 83% ± 0.5%, and were similar among clades (Fig. 4B). In contrast, RNPs with gRNA 363, which had a greater degree of nucleotide mismatch with the 3′ LTR, showed reduced target gene cleavage (Fig. 4B). Not surprisingly, perfect matches between gRNA 363 and target sequences (clade B and D) resulted in the highest cleavage efficiency (89% ± 1.3% and 89% ± 2.3%, respectively) (Fig. 4B). The sequence targeted by gRNA 363 contained 4 nucleotide mismatches with the corresponding sequence in HIV-1 clades A and G, and these mismatches were clustered proximal to the PAM (Fig. 4C). The degree of mismatch corresponded to decreases in cleavage efficiency for clade A (4.2% ± 0.6%) and for clade G (16% ± 6.1%) (Fig. 4B).

There were 6 bp mismatches between gRNA 363 and the 3′ LTR of clade C, and consequently demonstrated very low levels of cleavage of this target (5.4% ± 0.3%) (Fig. 4B, C). There were 10 bp mismatches between gRNA 363 and clade E, and this resulted in a complete lack of target cleavage (Fig. 4B). In contrast to this pattern, gRNA 363 had four nucleotide mismatches with the 3′ LTR of clade F, but demonstrated high levels of target cleavage (84% ± 3%) (Fig. 4B). These results highlight the impact of sequence diversity on the potential therapeutic utility of anti-HIV-1 gRNAs, and also show that imperfect complementarity between target and gRNA does not prohibit the broad use of a given gRNA across HIV-1 sequences.

In vivo cleavage of HIV-1 proviral 5′ LTR in TZM-bl cells

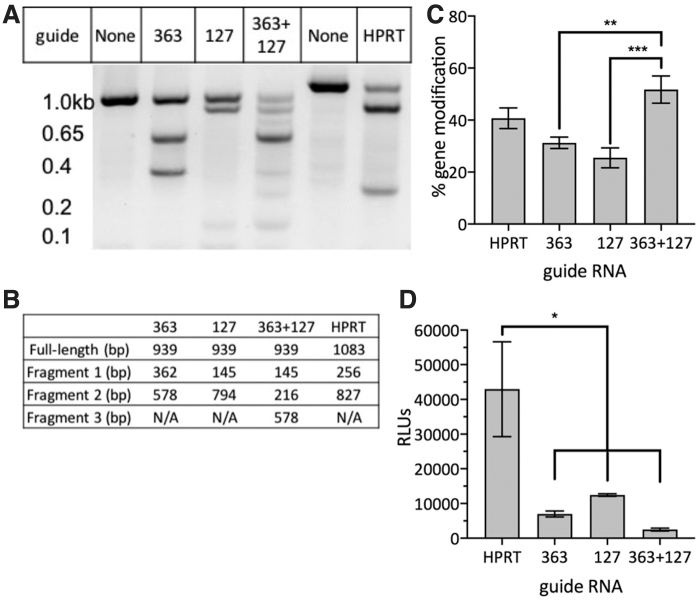

To assess the efficacy of anti-HIV-1 gRNAs following delivery to cells, we performed in vivo assays in TZM-bl cells that contain integrated copies of two modified forms of the HIV-1 provirus.31 Four days after transfection with RNPs, the genomic DNA was isolated from the cells, and the percentage of gene modification resulting from cleavage of the 5′ LTR was determined using PCR followed by the T7E1 assay. An optimized control gRNA targeting the HPRT gene was used as a positive control. The percentage of gene modification following transfection of RNPs targeting the HPRT gene was 41% ± 4.0% (Fig. 5A, C). The expected fragment sizes following cleavage with each guide is shown in Figure 5B.

FIG. 5.

CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage of 5′LTR in TZM-bl cells with one or more LTR gRNAs. Gene modification was analyzed using T7EI assay. (A) Example gel image yielded by T7E1 assay, which showed positive gene modification to the amplified 5′LTR and HPRT gene by gRNAs 363 and 127, and in combination. (B) The expected fragment size of PCR product after T7E1 digestion. (C) Percent gene modification for each gRNA treatment was determined using the following formula: 100 × [(1 − (1-fraction cleaved))1/2]. Mean data ± SEM from six experiments. (D) Luciferase reporter assay mean data ± SEM from triplicates. Statistical analysis was determined for both (C, D) using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD post hoc test. All means were compared with one another; *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001. HPRT, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; T7E1, T7 endonuclease 1 mutation detection.

Transfection with RNPs expressing gRNA 363 or gRNA 127 resulted in similar frequencies of modification of the 5′ LTR compared with those using the HPRT gRNA. The cotransfection of RNPs containing gRNA 363 and gRNA 127 demonstrated the highest levels of gene modification (52% ± 5.2%) and was significantly higher than transfection of either gRNA alone (31% ± 2.2% gene modification with gRNA 363, and 25% ± 3.9% gene modification with gRNA 127) (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, use of the two different gRNAs resulted in a 231 bp deletion event (Supplementary Fig. S4). Given that the deletion event is not quantified by the T7E1 assay, it is likely that the targeting of the 5′ LTR by transfection of both gRNA 363 and gRNA 127 was higher than what was measured.

A luciferase reporter assay was performed to examine functional activity of the LTR after transfection with the RNPs stated above. Cells treated with LTR guide RNPs demonstrated significantly less luciferase expression than those treated with the HPRT RNP. gRNAs 363 and 127, either alone or in combination, mediated functional damage of the LTR, damaging transcriptional capability.

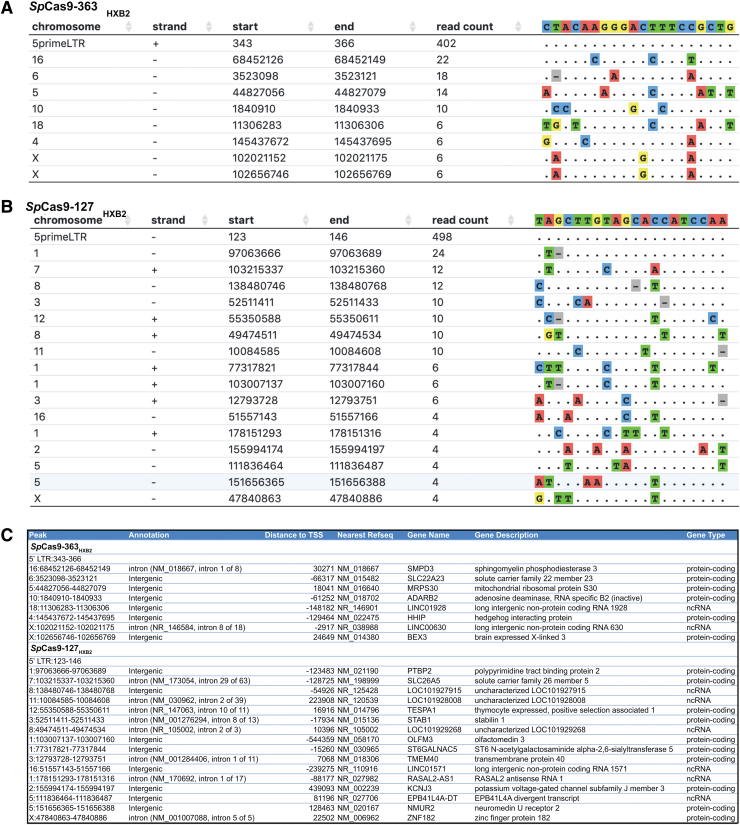

CIRCLE Seq analysis of on- and off-target cleavage events

We performed CIRCLE-Seq to assess off-target cleavage events resulting from the use of several different gRNAs. To perform CIRCLE-Seq, we used circularized genomic DNA from the TZM-bl cell line as a target for in vitro cleavage using RNPs consisting of SpCas9, tracrRNA, and either gRNA 127 or gRNA 363. After adaptor ligation and library preparation, off-target events induced by CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage were assessed by next-generation sequencing.

The most common off-target cleavage events for these gRNAs occurred at ∼5% of the frequency of on-target cleavage events (Fig. 6A, B). This was a relatively high degree of target specificity relative to other published guides tested by CIRCLE-Seq.14 Although the on- to off-target ratio is informative, it is also important to identify whether likely off-target cleavage events would be at concerning genomic locations—for example, tumor suppressor genes or cancer-associated chromosomal translocations. Therefore, we performed an analysis to identify the nearest annotated gene, and to delineate the position of the predicted off-target cleavage site relative to the target gene (Fig. 6C). While several intronic cleavage events were detected, it is notable that we did not detect any off-target events within known protein coding sequences.

FIG. 6.

Assessment of on- and off-target cleavage events using CIRCLE-Seq. CIRCLE-Seq was performed using DNA from TZM-bl cells and RNPs formed with recombinant SpCas9 and in vitro transcribed sgRNA 363 (A) and sgRNA 127 (B). Analysis of the resulting sequencing data identified the indicated cleavage events with the indicated numbers of read counts. (C) Annotation of cleavage events identified by CIRCLE-Seq. No off-target events were identified within the exons of protein coding genes. Off-target cleavage events occurred within both intergenic and intronic regions as indicated. RNP, ribonucleoprotein; sgRNA, single-guide RNA; SpCas9, Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9. Color images are available online.

These data provide a manageable list of potential off-target events that could be assessed by targeted, capture, or amplicon-based resequencing during preclinical development of identified gRNAs. Taken together, these data demonstrate the design and implementation of gRNAs capable of effectively and specifically targeting the LTRs of HIV-1 of multiple clades, and provide a framework for the development and thorough assessment of gRNA candidates.

Discussion

The development of CRISPR/Cas gene editing to cleave the integrated HIV-1 provirus and prevent new virus production provides new opportunities for the development of innovative therapeutic approaches. This method requires the careful design of gRNA molecules that bind to a small region within the target DNA sequence, and directs the double-stranded DNA cleavage event by the Cas9 endonuclease. Careful design and testing of gRNAs are critically important for the efficacy and clinical success of this technique, and selection of gRNAs with broad reactivity across patient isolates is an important consideration when developing gene editing therapeutics.32,33

When over 1,200 HIV-1 LTR sequences were aligned to more than 500 potential gRNA sites, the most conserved target regions were found in 70% of sequences studied, including all main M group subtypes.33 In another analysis, guides targeting within or proximal to the TAR encoding region were predicted to cleave 100% of clade B sequences, and 96.1% of unique sequences from each common subtype.32

Selection of conserved regions in the viral genome is critical to avoid areas of sequence diversity both among and within patient isolates. The Los Alamos National Laboratories (LANL) HIV-1 sequence database is a highly impactful tool to search for conserved target regions among and between clades, as it contains over three thousand complete HIV-1 sequences, categorized by subtype and geographical region.

There are several computational tools that have been developed to aid in the design and in silico testing of gRNAs.34 Dampier et al. adapted the Activity Score (MIT CRISPR Design Tool, http://crispr.mit.edu) that defined the probability of a particular gRNA inducing an off-target event in the human genome,35 to instead determine the predicted percentage cleaved by a specific gRNA.34 They screened over 200 anti-HIV-1 gRNAs against 390,000 subtype B patient-derived HIV-1 sequences and found that published gRNAs had highly variable predicted effectiveness in cleaving the target sequences. An integral part to finding an effective guide would be to test guides representative of sequences from patients to enhance their broad clinical application. Within the HIV-1 genome, such regions include the 5′ and 3′ LTRs, gag, env, pol, as well as other highly conserved regions such as the viral primer binding site.36

Single edits by CRISPR/Cas could eventually lead to viral escape,37 and thus, the complete excision of the viral genome using gRNAs to the LTRs would avoid the potential for viral escape.38 In addition, targeting highly conserved regions in the genome was also found to decrease the chance of viral escape because the most conserved regions are essential for viral integrity and are less tolerable to mutations.37,39 Alternatively, the use of more than one gRNA (multiplexing) to target two distinct regions in the viral genome at the same time has also been found to significantly decrease viral escape following gene editing.40

In addition to designing gRNA molecules with efficient binding to conserved DNA regions, it is also important to ensure that there is little, if any, off-target binding. This arises when the gRNA binds to a closely homologous region in the human genome, where nontarget DNA sequences can be cleaved. Of special concern is if the off-target region lies within an exon of a gene important for cellular metabolism, or is involved in preventing malignant transformation such as a tumor suppressor gene. In this case, an off-target event could have catastrophic consequences for the cell, and for a patient receiving this form of therapy.

Direct testing of off-target cleavage events with proposed Cas9/gRNA pairs should be a prerequisite for implementation of genome editing strategies. A wide variety of techniques have been developed to identify off-target cleavage events or mutations induced by a complex of a Cas endonuclease and gRNA. These range from whole-genome sequencing, which lacks the depth of coverage that would be needed to identify rare events within a population of cells, to in silico analyses of predicted cut sites with implementation of targeted sequencing approaches to identify mutations in transduced cells.41–43 This later approach holds particular appeal, as focusing on a smaller set of targets using capture or amplicon-based sequencing would allow the high depth of sequencing that is required to detect rare events.

However, while it was initially thought that in silico prediction algorithms might accurately predict the possible range of off-target effects, it has become apparent that Cas endonuclease systems exhibit an as of yet poorly understood site preference with respect to off-target events. The full array of tens of thousands of potential off-target sites that could be predicted using imperfect search parameters is far more than could be reasonably sequenced to an acceptable depth of coverage, even in a targeted manner. As we have shown, gRNA/Cas9 pairs exhibited significant cleavage activity on sequences with as many as four mismatches. CIRCLE-seq analyses also detected cleavage events at sites with DNA or RNA bulges. Allowing for single RNA or DNA bulges and four bases of misalignment results in the identification of more than 3,000 off-target sites using in silico tools such as Cas-OFFinder.44

As of now, it is unclear whether computational tools could be used to more accurately predict which of these sites should be monitored by targeted sequencing in subsequent experiments. Recently, methods for in vitro identification of Cas cleavage sites have emerged as an alternative or supplement to in silico prediction. These methods use genomic DNA and in vitro cleavage reactions with gRNA/Cas9 endonucleases to identify the universe of preferred cleavage sites.14,45 Two of these methods, CIRCLE-Seq and SITE-Seq, have been coupled to amplicon based-sequencing to allow detailed examination of Cas9-mediated on- and off-target cleavage events in cells.43,45

We describe the design and testing of several gRNAs that target the 5′ and 3′ LTR region of the HIV-1 provirus. We prepared RNPs containing a gRNA/tracrRNA and SpCas9, and used these complexes to achieve in vitro modification of target DNA, as well as in vivo delivery to assess the cleavage efficiency of the gRNAs in nucleated cells. We observed significant cleavage efficiencies of the target DNA in vitro. In vivo cleavage efficiencies reached as high as 50% and correlated with functional damage to the LTR by reductions in luciferase activity in the TZM-bl cell line. Other methods, in addition to the T7E1 assay used to quantify gene cleavage in vivo,46 include interference of cleavage edits (ICE)47 and tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE).48 These studies were followed by an in-depth analysis of the on-target and off-target efficiencies of the gRNAs against the target sequence.

Our findings show that the gRNAs we designed had high levels of cleavage efficiencies when used individually, and in some cases, the use of two guides increased the proportion of target cleavage over a single guide. We also determined that gRNA 127 showed high levels of cleavage of different LTR sequences from HIV-1 clades A to G, suggesting that efficient gene cleavage can occur even with less than perfect homology between the gRNA and target. These results are consistent with previous analyses of off-target cleavage events in vitro.14,45

To assess the conservation of gRNA target regions across the different HIV-1 clade sequences at the 3′ LTR, we aligned each of four different gRNAs to their target sequence in each of the eight clades. We then assessed the frequency by which the gRNA matched each clade, by comparing to multiple isolates of HIV within each clade. These analyses showed a striking conservation of target region across clades, and within a high percentage of different isolates from each clade (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Our studies highlight several considerations in the use of CRISPR/Cas9 for eliminating viral targets, including HIV-1. The careful design of gRNAs is critically important, as is determining whether a particular guide or guides would be effective against genetic variants in a single patient. In addition, it is important to define the degree and type of off-target events of particular guides. Off-target cleavage in cellular targets (or other cell types) may lead to serious adverse events that must be considered before developing gene editing as a therapeutic modality. Furthermore, the widespread applicability of a particular gRNA, or combinations of gRNAs, could significantly extend the global utility of a given therapeutic modality. This is illustrated on the use of gRNAs to the LTR region of different clades of HIV-1, and demonstrated a high degree of gene cleavage despite differences in the genetics of these viral strains. Thus, the combination of careful screening of gRNAs, both singly and in combinations, together with a careful analysis of the proportion of on- and off-target events is recommended for the eventual clinical development of gene editing as a therapeutic. The gRNA nomenclature is to facilitate comparisons and analyses among laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The pBlue 3′LTR-luc-A through G (also known as HIV-1 LAI LTR Luciferase Reporter Vectors) was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV-1 LAI LTR Luciferase Reporter Vector from Dr. Reink Jeeninga and Dr. Ben Berkhout (Cat. No. 4788).21,22 We acknowledge the contributions to CFD computations by Drs. Jiang Gui and Siting Li (Department of Data Sciences, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

Illumina Sequencing was carried out at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth in the Genomics Shared Resource that was established by equipment grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, and is supported, in part, by a Cancer Center Core Grant (P30CA023108) from the National Cancer Institute. Implementation of CIRCLE-Seq was supported by a grant to M.S.H. from the Munck-Pfefferkorn Education and Research Fund at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. Funding for this work was provided by a Merit Review award to A.L.H. by the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. de Buhr H, Lebbink RJ: Harnessing CRISPR to combat human viral infections. Curr Opin Immunol 2018;54:123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hu W, Kaminski R, Yang F, et al. : RNA-directed gene editing specifically eradicates latent and prevents new HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:11461–11466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E: A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012;337:816–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin SR, Yang HC, Kuo YT, et al. : The CRISPR/Cas9 system facilitates clearance of the intrahepatic HBV templates in vivo. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2014;3:e186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang W, Ye C, Liu J, Zhang D, Kimata JT, Zhou P: CCR5 gene disruption via lentiviral vectors expressing Cas9 and single guided RNA renders cells resistant to HIV-1 infection. PLoS One 2014;9:e115987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kang H, Minder P, Park MA, Mesquitta WT, Torbett BE, Slukvin II: CCR5 disruption in induced pluripotent stem cells using CRISPR/Cas9 provides selective resistance of immune cells to CCR5-tropic HIV-1 virus. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2015;4:e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu Z, Chen S, Jin X. et al. : Genome editing of the HIV co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 by CRISPR-Cas9 protects CD4(+) T cells from HIV-1 infection. Cell Biosci 2017;7:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu L, Yang H, Gao Y, et al. : CRISPR/Cas9-mediated CCR5 ablation in human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells confers HIV-1 resistance in vivo. Mol Ther 2017; 25:1782–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Panfil AR, London JA, Green PL, Yoder KE: CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to disable the latent HIV-1 provirus. Front Microbiol 2018;9:3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xiao Q, Guo D, Chen S: Application of CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing in HIV-1/AIDS therapy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2019;9:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Los Alamos National Laboratories, HIV sequence database. Available at https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HIV/CRFs/CRFs.html

- 12. Bbosa N, Kaleebu P, Ssemwanga D: HIV subtype diversity worldwide. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2019;14:153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hemelaar J, Elangovan R, Yun J, et al. : Global and regional molecular epidemiology of HIV-1, 1990–2015: A systematic review, global survey, and trend analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:143–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsai SQ, Nguyen NT, Malagon-Lopez J, Topkar VV, Aryee MJ, Joung JK: CIRCLE-seq: A highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat Methods 2017;14:607–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adachi A, Gendelman HE, Koenig S, et al. : Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol 1986;59:284–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Center for Biotechnology Information Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. Available at http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

- 17. Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO: Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 2009;6:343–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gibson DG: Enzymatic assembly of overlapping DNA fragments. Methods Enzymol 2011;498:349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, et al. : RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 2013;339:823–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Integrated DNA Technologies Custom Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 guide RNA design site. Available at https://www.idtdna.com/site/order/designtool/index/CRISPR_CUSTOM

- 21. Jeeninga RE, Hoogenkamp M, Armand-Ugon M, de Baar M, Verhoef K, Berkhout B: Functional differences between the long terminal repeat transcriptional promoters of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes A through G. J Virol 2000;74:3740–3751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klaver B, Berkhout B: Comparison of 5′ and 3′ long terminal repeat promoter function in human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol 1994;68:3830–3840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Platt EJ, Bilska M, Kozak SL, Kabat D, Montefiori DC: Evidence that ecotropic murine leukemia virus contamination in TZM-bl cells does not affect the outcome of neutralizing antibody assays with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 2009;83:8289–8292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Platt EJ, Wehrly K, Kuhmann SE, Chesebro B, Kabat D: Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 1998;72:2855–2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takeuchi Y, McClure MO, Pizzato M: Identification of gammaretroviruses constitutively released from cell lines used for human immunodeficiency virus research. J Virol 2008;82:12585–12588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wei X, Decker JM, Liu H et al. : Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46:1896–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Derdeyn CA, Decker JM, Sfakianos JN, et al. : Sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to the fusion inhibitor T-20 is modulated by coreceptor specificity defined by the V3 loop of gp120. J Virol 2000;74:8358–8367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guschin DY, Waite AJ, Katibah GE, Miller JC, Holmes MC, Rebar EJ: A rapid and general assay for monitoring endogenous gene modification. Methods Mol Biol 2010;649:247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsai lab respository for CIRCLE-seq analytical software. Available at https://github.com/tsailabSJ/circleseq

- 30. Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, et al. : Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol 2016;34:184–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Geonnotti AR, Bilska M, Yuan X, et al. : Differential inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and TZM-bl cells by endotoxin-mediated chemokine and gamma interferon production. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2010;26:279–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sullivan NT, Dampier W, Chung CH, et al. : Novel gRNA design pipeline to develop broad-spectrum CRISPR/Cas9 gRNAs for safe targeting of the HIV-1 quasispecies in patients. Sci Rep 2019;9:17088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roychoudhury P, De Silva Feelixge H, Reeves D et al. : Viral diversity is an obligate consideration in CRISPR/Cas9 designs for targeting the HIV reservoir. BMC Biol 2018;16:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dampier W, Sullivan NT, Chung CH, Mell JC, Nonnemacher MR, Wigdahl B: Designing broad-spectrum anti-HIV-1 gRNAs to target patient-derived variants. Sci Rep 2017;7:14413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, et al. : DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:827–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang Z, Wang W, Cui YC, et al. : HIV-1 employs multiple mechanisms to resist Cas9/single guide RNA targeting the viral primer binding site. J Virol 2018;92:e01135–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Das AT, Binda CS, Berkhout B: Elimination of infectious HIV DNA by CRISPR-Cas9. Curr Opin Virol 2019;38:81–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lebbink RJ, de Jong DC, Wolters F, et al. : A combinational CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing approach can halt HIV replication and prevent viral escape. Sci Rep 2017;7:41968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Darcis G, Binda CS, Klaver B, Herrera-Carrillo E, Berkhout B, Das AT: The impact of HIV-1 genetic diversity on CRISPR-Cas9 antiviral activity and viral escape. Viruses 2019;11:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang G, Zhao N, Berkhout B, Das AT: A combinatorial CRISPR-Cas9 attack on HIV-1 DNA extinguishes all infectious provirus in infected T cell cultures. Cell Rep 2016;17:2819–2826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jamal M, Ullah A, Ahsan M, Tyagi R, Habib Z, Rehman K: Improving CRISPR-Cas9 on-target specificity. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2018;26:65–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zischewski J, Fischer R, Bortesi L: Detection of on-target and off-target mutations generated by CRISPR/Cas9 and other sequence-specific nucleases. Biotechnol Adv 2017;35:95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Akcakaya P, Bobbin ML, Guo JA, et al. : In vivo CRISPR editing with no detectable genome-wide off-target mutations. Nature 2018;561:416–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bae S, Park J, Kim J: Cas-OFFinder: A fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics 2014;30:1473–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cameron P, Fuller CK, Donohoue PD, et al. : Mapping the genomic landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage. Nat Methods 2017;14:600–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hadden JM, Convery MA, Déclais A-C, Lilley DMJ, Phillips SEV: Crystal structure of the Holliday junction resolving enzyme T7 endonuclease I. Nat Struct Biol 2001;8:62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hsiau T, Conant D, Maures T, et al. : Inference of CRISPR edits from Sanger trace data. Available at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2019/01/14/251082.full.pdf accessed on August11, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B: Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van Rossum G, Drake FL Jr: Python Reference Manual. Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica, Amsterdam, 1995 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.