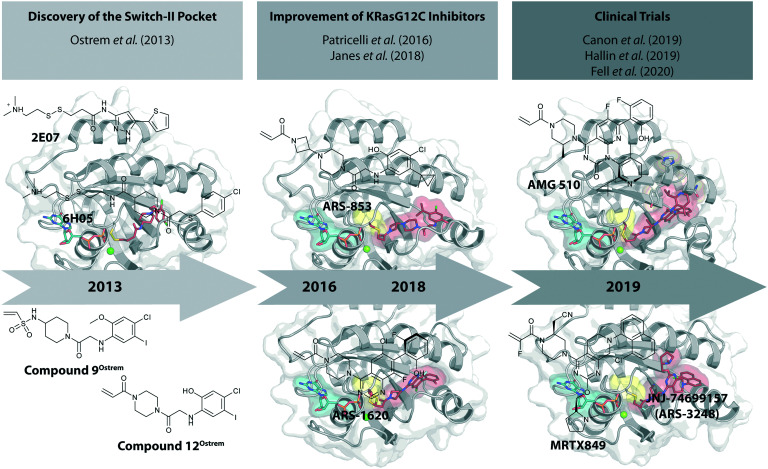

Short historical perspective of the development of promising KRasG12C inhibitors that have recently entered clinical trials.

Short historical perspective of the development of promising KRasG12C inhibitors that have recently entered clinical trials.

Abstract

KRas is the most frequently mutated oncogene in human cancer, and even 40 years after the initial discovery of Ras oncogenes in 1982, no approved drug directly targets Ras in Ras-driven cancer. New information and approaches for direct targeting of mutant Ras have fueled hope for the development of direct KRas inhibitors. In this review, we provide a comprehensive historical perspective of the development of promising KRasG12C inhibitors that covalently bind to the mutated cysteine residue in the switch-II pocket and trap the protein in the inactive GDP bound state. After decades of failure, three covalent G12C-specific inhibitors from three independent companies have recently entered clinical trials and therefore represent new hope for patients suffering from KRasG12C driven cancer.

Introduction

Ras proteins act as molecular switches that regulate many cellular processes by switching between an inactive GDP-bound and an active GTP-bound state. To accomplish this switch between states, guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that promote activation and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) that inactivate RAS by catalyzing GTP hydrolysis come into play.1,2 Mutations within the Ras proteins that lead to defects in the switch mechanism represent major drivers in human cancer. Oncogenic Ras mutations are found in about 25% of all human cancers, including three of the most lethal forms (lung, colon, and pancreatic cancer).3 Among the Ras proteins, KRas is the predominantly mutated isoform (85%), followed by NRas (11%) and HRas (4%), with the most frequent mutations occurring at amino acid positions G12, G13, and Q61.3 Their oncogenic properties are commonly attributed to mutations at positions 12 and 13, causing a steric clash with the catalytic arginine finger that is donated by the GAPs, while mutations at position 61 disturb the coordination of a nucleophilic water molecule leading to an accumulation of active GTP-bound Ras proteins in the cell.4,5

Westover and colleagues systematically characterized the biochemical and biophysical properties of common cancer-associated KRas mutations. They showed that the investigated G12, G13 and Q61 residue mutations exhibit decreased intrinsic as well as GAP-stimulated GTP-hydrolysis rates.6 They also showed that the rate of GEF-independent nucleotide exchange is increased for the G13D mutant Ras compared to the wild type protein, thus providing an additional explanation for the cause of enhanced aberrant Ras signaling in the cell.

Because of their prominent role in cancer, Ras oncogenes were identified as attractive targets for cancer therapy since their discovery, but attempts to target Ras have been largely unsuccessful for several reasons and Ras proteins were long considered “undruggable”.7,8 Early attempts to impair oncogenic Ras signaling via GTP-competitive inhibitors were regarded as constituting an unfavorable approach due to the high affinity of GDP/GTP (KD ∼ 20 pM) for Ras and the high cellular concentrations of these nucleotides (GDP ∼ 40 μM, GTP ∼ 400 μM).9 However, this general approach recently gained renewed attention when GDP derivatives harboring an electrophilic group on the β-phosphate were shown to be able to bind irreversibly to the oncogenic G12C mutant of Ras.10,11

Alternative strategies to disrupt the cellular localization of Ras proteins have included the inhibition of post-translational modifications via FTase or APT1-inhibitors, leading to the discovery of potent inhibitors for NRas and HRas, but not KRas, and some of these compounds are currently under pre-clinical investigation.12–14 PDEδ inhibitors have been developed to target the KRas localization at the plasma membrane, but have not yet advanced to clinical trials.15–17 Efforts to inhibit the Ras–SOS (son of sevenless, a GEF) interactions led to the first pan-Ras inhibitor that recently entered clinical trials.18 This approach generally seems promising because of the positive feedback mechanism of SOS that is recruited by Ras:GTP, thus leading to an amplification of the Ras activation and a cross-activation of wild-type Ras and other Ras isoforms by oncogenic Ras.19,20 However, despite the extensive research on the possible ways to tackle oncogenic Ras in the last 4 decades, no compound that directly or indirectly targets Ras in Ras-driven cancers has been approved as a drug.

The recent development of molecules that bind covalently and effectively inhibit the G12C oncogenic mutant of KRas, but without interaction with the wild-type protein, raised great excitement.21 These small molecules bind to a previously unrecognized pocket, the switch-II pocket. In this review, we provide a short historical perspective of the development of these KRasG12C inhibitors that covalently bind to the mutated cysteine residue. These compounds have entered clinical trials in 2019 only six years after the seminal publication appeared (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Time-line of the development of promising KRasG12C inhibitors.

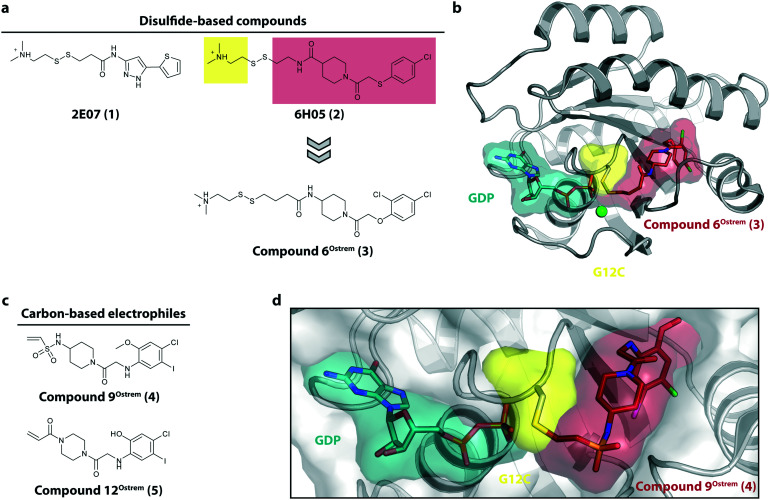

Discovery of switch-II pocket binders

The starting point for the development of KRasG12C inhibitors currently being investigated in clinical trials was the discovery of the so called switch-II pocket in 2013 by the Shokat Laboratory.22 Using a disulfide-fragment-based screening approach, a library of 480 tethering compounds was screened for covalent binding to KRasG12C. The fragments ; 2E07 (1) and ; 6H05 (2) showed the greatest degree of modification of the G12C mutant while sparing the wild-type protein (Fig. 2a). Via structure–activity-relationship (SAR) studies of ; 6H05 (2), compound 6Ostrem (3) was generated and finally led to a co-crystal structure with KRasG12C in the GDP state (Fig. 2b, pdb id ; 4luc). The crystallographic study revealed that the compound does not bind to the nucleotide binding pocket, but to a new pocket beneath the effector binding switch-II and it was therefore termed the switch-II pocket (S-IIP). S-IIP is located between the central β-sheet and switch-II that shows significant conformational changes upon ligand binding to form a distinct pocket, whereas the conformation of switch-I is unchanged from the GDP-bound state. To generate more potent inhibitors, Shokat and colleagues continued with carbon-based electrophiles including acrylamides and vinyl sulfonamides to allow covalent modification of the mutant cysteine. Around 100 derivatives were synthesized by iterative structural evaluation and compound 9Ostrem (4) as well as compound 12Ostrem (5) showed the greatest degree of protein modification (Fig. 2c). A co-crystal structure of compound 9Ostrem (4) (pdb id ; 4lyh, ; 4lyj) bound to KRasG12C was obtained showing a similar binding mode as previously described for compound 6Ostrem (3) (Fig. 2d). Upon compound binding, the protein is locked in the inactive GDP bound conformation and GTP binding as well as interactions with regulatory and effector proteins such as SOS and Raf are impaired, thereby blocking oncogenic Ras signaling.21,23 Thus, the identification of an addressable, previously unknown binding pocket on the surface of Ras and the proof-of-concept of the first switch-II pocket inhibitors that covalently bind to the KRasG12C mutant represented a major step towards targeting the “undruggable” Ras in Ras-driven cancer.

Fig. 2. Discovery of switch-II pocket binder. a, Chemical structures of the screening hits 2E07 (1) and ; 6H05 (2). b, Co-crystal structure of KRasG12C in the GDP state bound to compound 6Ostrem (3) (pdb id ; 4luc). c, Chemical structures of the vinyl sulfonamide compound 9Ostrem (4) and the acrylamide compound 12Ostrem (5). d, Co-crystal structure of KRasG12C in the GDP state bound to compound 12Ostrem (5) (pdb id ; 4lyh).

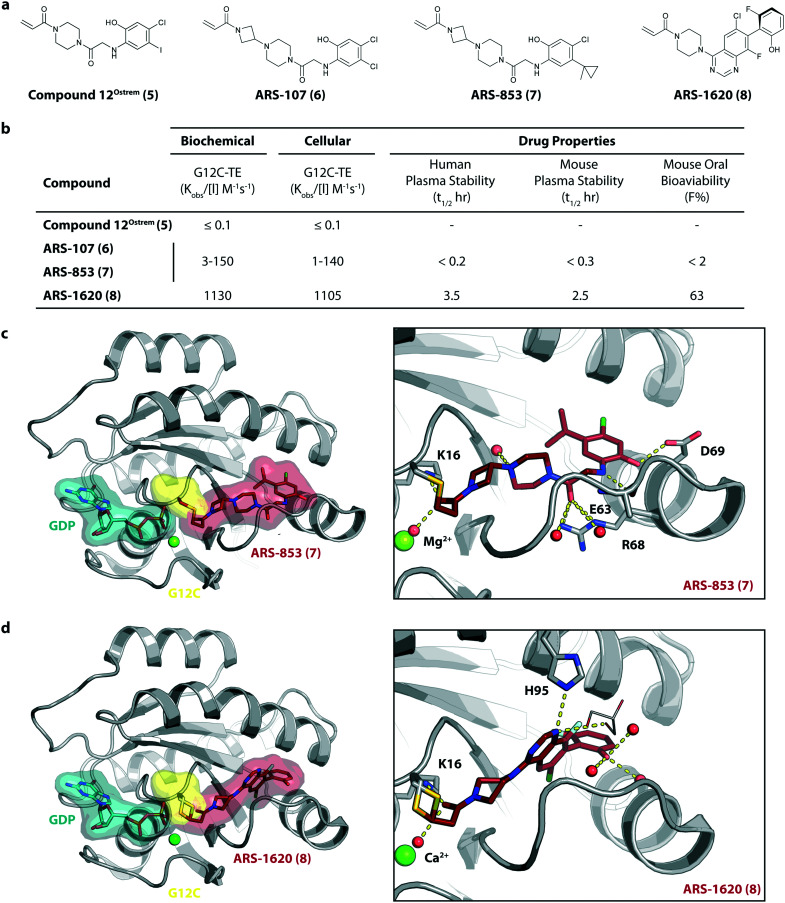

Further improvement of KRasG12C inhibitors

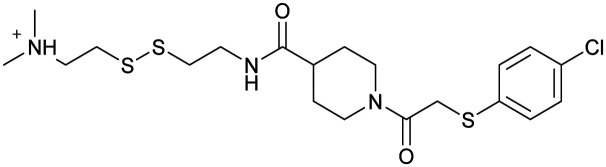

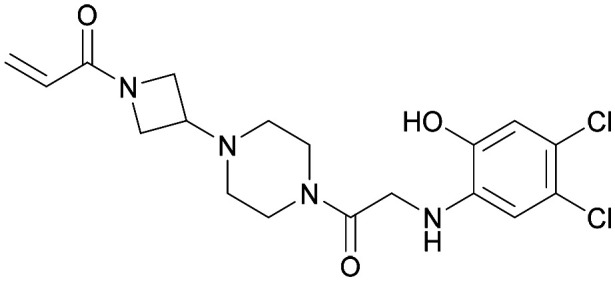

To improve the cellular efficacy of the previously reported compound 12Ostrem (5), Wellspring Bioscience, co-founded by Kevan Shokat and others in 2012, developed an LC/MS–MS-based assay to directly and quantitatively determine small molecule engagement of KRasG12C in a cellular setting.23 An iterative structure-based design of covalent KRasG12C compounds was performed and an early strong biochemical hit, ARS-107 (6), was identified (Fig. 3a). Modification of the hydrophobic binding pocket elements finally led to the more potent compound ARS-853 (7) that showed a 600-fold improvement in the biochemical assay compared with compound 12Ostrem (5), and the IC50 in the cellular setting was improved from >100 μM to 1.6 μM, despite targeting only the inactive GDP-bound state of KRasG12C (Fig. 3b). The co-crystal structure of ARS-853 (7) (pdb id ; 5f2e) bound to KRasG12C confirmed the covalent modification of the mutant cysteine trapping the oncoprotein in the inactive conformation and therefore inhibiting mutant KRas-driven signaling (Fig. 3c).

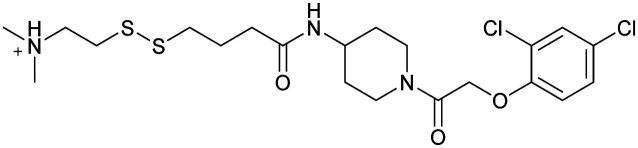

Fig. 3. Further improvement of KRasG12C inhibitors. a, Chemical structures of compound 12Ostrem (5), ARS-107 (6), ARS-853 (7) and ARS-1620 (8). b, Biochemical and cellular data as well as drug-like properties of compounds shown in Fig. 2a. c, Co-crystal structure of KRasG12C in the GDP state bound to compound ARS-853 (7) (left, pdb id ; 5f2e) and key interactions (right). d, Co-crystal structure of KRasG12C in the GDP state bound to compound ARS-1620 (8) (left, pdb id ; 5v9u) and key interactions (right).

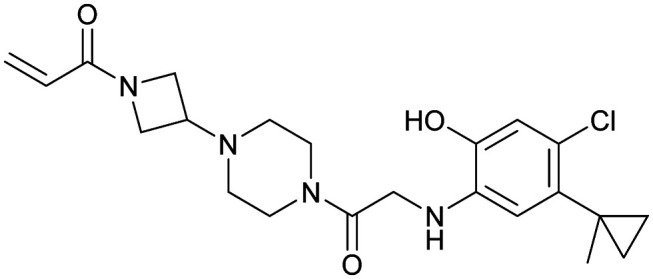

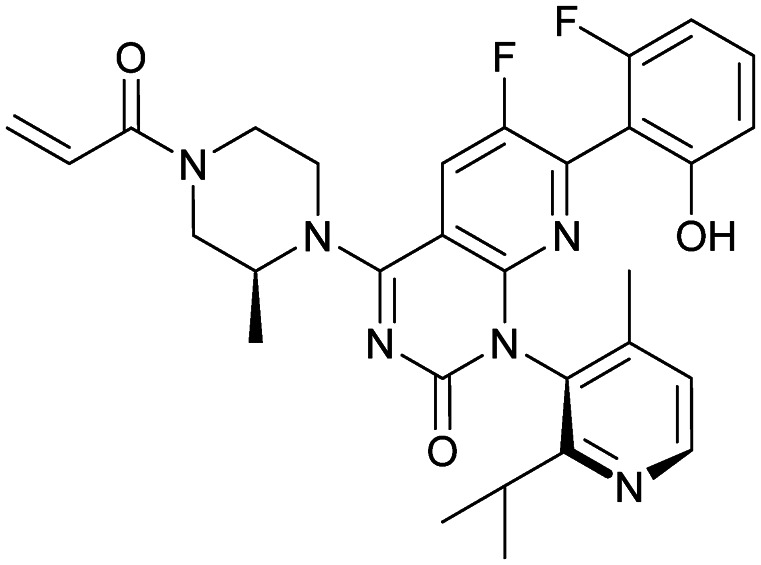

ARS-853 (7) was at the time the first KRasG12C inhibitor with cellular potency in the range of a drug candidate, but a major drawback of this ARS-series was the short metabolic plasma stability and poor bioavailability in mice. In a subsequent study, Janes et al. identified the ortho-amino phenol moiety as well as the glycine linker within the core scaffold as metabolic hotspots and therefore replaced the flexible linker of the ARS-853 series with a more rigid bicyclic scaffold.24 A quinazoline core was identified as a lead scaffold with drug-like properties. Several quinazoline-based compounds were synthesized and led to the development of ARS-1620 (8), which contains a fluorophenol hydrophobic binding moiety (Fig. 3a). The co-crystal structure of ARS-1620 (8) (pdb id ; 5v9u) bound to KRasG12C revealed a different binding mode and trajectory compared to the previously known S-IIP KRasG12C inhibitors. ARS-1620 (8) covalently binds to the mutant cysteine and traps the oncoprotein in the inactive form. An additional hydrogen bond with the side chain of His95 was observed that presumably induced a more rigid conformation that favors the covalent bond formation. Additional analysis revealed that the covalent reaction appears to be catalyzed intrinsically by Lys16 of Ras, thus leading to a high potency of the compounds despite low reversible binding affinities.25 The hydroxyl group of the fluorophenol moiety of the active S-atropisomer formed several hydrogen bonds with KRas (R68, D69 and Q99), whereas the fluoro group occupied a hydrophobic region (Fig. 3d). Compared to ARS-853 (7), ARS-1620 (8) shows a 10-fold improvement in the biochemical assay used to quantify Ras engagement (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the R-atropisomer is nearly 1000-fold less potent than ARS-1620 (8) and therefore served as a useful control derivative for all following experiments. In addition to the improved biochemical activity, ARS-1620 (8) also inhibited Ras signaling in H358 cells harboring the G12C mutation in a dose-dependent and selective manner with a 10-fold improvement in potency (IC50 of 120 nM for ARS-1620 versus 1700 nM for ARS-853). Janes et al. showed that ARS-1620 (8) exhibited a high oral bioavailability (F > 60%) in mice and sufficient plasma stability in mice as well as in humans. In both subcutaneous xenograft models and patient-derived tumor xenograft models bearing the G12C mutation, ARS-1620 (8) inhibited tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner. Thus, ARS-1620 (8) represented a new generation of a KRasG12C S-IIP binder with promising drug-like properties for translation into the clinic.

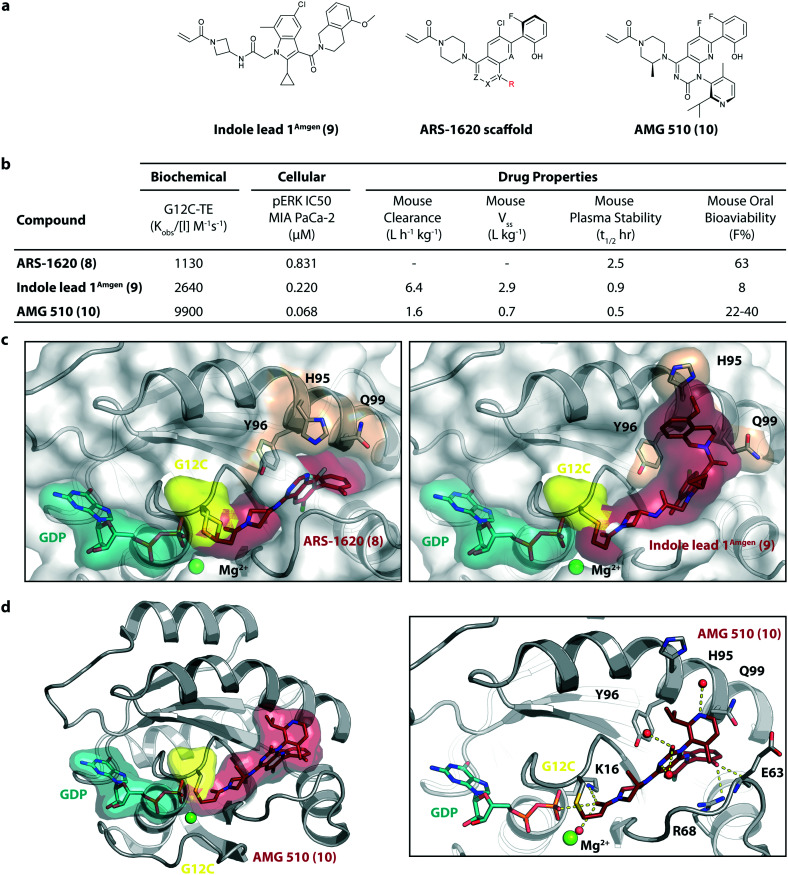

KRasG12C inhibitors in clinical trials

In 2018/2019, only about six years after the initial publication of the switch-II pocket in KRasG12C by the Shokat Laboratory, three small molecules, AMG 510, MRTX849, and JNJ-74699157 (ARS-3248) from three independent companies reached clinical testing in humans.

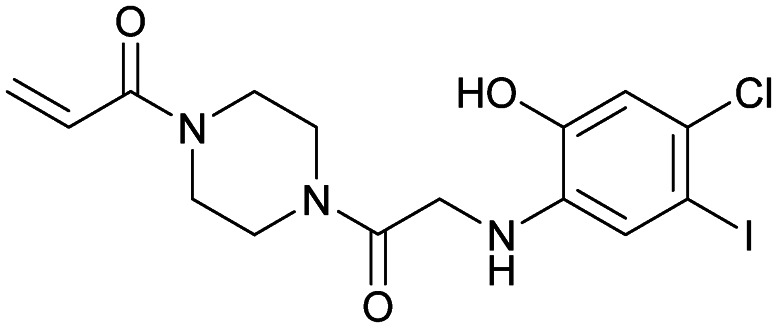

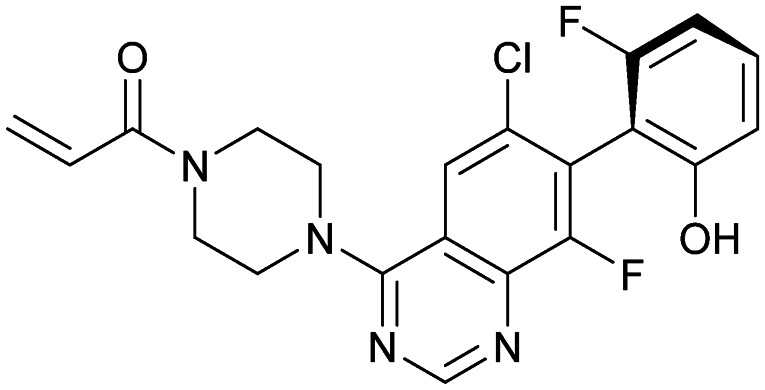

AMG 510 (10), developed by Amgen, was the first KRasG12C inhibitor that entered clinical trials in humans in August 2018 (NCT03600883).26 In collaboration with Carmot Therapeutics, Amgen identified this compound through a custom library synthesis and screening platform called Chemotype Evolution as well as structure-based design of azetidine-based covalent KRasG12C inhibitors that finally led to the identification of indole lead 1Amgen (9) with submicromolar inhibition of downstream Ras signaling.27 The co-crystal structure of compound 9 (pdb id ; 6p8z) bound to KRasG12C revealed a novel binding mode compared to ARS-1620 (8) with a previously unknown cryptic pocket on the surface of KRasG12C created by an alternative orientation of histidine 95. The tetrahydroisoquinoline ring of compound 9 occupied the unexploited cryptic pocket compromised by the residues H95, Y96 and Q99 (Fig. 4c). Although the engagement of this surface groove led to a significant enhancement in cellular potency (pERK IC50 = 0.220 μM) compared to ARS-1620 (pERK IC50 = 0.831 μM) compound 9 suffered from very high clearance and low oral bioavailability, thus making it unsuitable for in vivo testing. To improve ADME properties and obtain compounds that are suitable for in vivo use, Lanman et al. compared the binding modes of compound 9 and ARS-1620 (8) and suggested potential access to the cryptic pocket by substitution of the N1 position of ARS-1620 (8).28 A series of novel acrylamide-based groove-binding compounds with a hybrid scaffold with access to the surface groove were prepared and finally led to the discovery of AMG 510 (10) (pdb id ; 6oim). The isopropyl-methylpyridine substituent of AMG 510 (10) that occupied the cryptic groove led to a 10-fold improvement in potency in a biochemical assay compared to ARS-1620 (IC50 = 0.09 μM) and also the IC50 in the cellular setting was improved to 0.03 μM (20-fold improvement in potency). In preclinical experiments, AMG 510 (10) inhibited the growth of mice xenograft tumors of KRasG12C mutant human tumor cells and patient-derived xenograft tumors in a dose-dependent manner; furthermore, tumor regression was observed at higher doses (Fig. 4b).29 AMG 510 (10) is currently being tested in a phase 1/2 study as a monotherapy (NCT03600883) involving patients with KRasG12C mutant advanced solid tumors.26 Four patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were treated once daily in escalating dosing cohorts with doses of 180 mg and 360 mg. AMG 510 (10) elicited a partial response (PR) in half of the patients, and led to stable disease (SD) in two patients. Treatment with AMG 510 (10) led to tumor reduction of 34% (180 mg) and 67% (360 mg) after 6 weeks, and after 18 weeks complete tumor regression in the patient who received 360 mg AMG 510 (10) was observed.29 AMG 510 (10) is also being tested in a phase 1 study in combination with anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibition (NCT04185883).30 In preclinical experiments, Amgen treated immunocompetent mice harboring KRasG12C-CT-26 tumors with AMG 510 (10) plus PD-1 inhibitor leading to complete and durable response in 9 out of 10 mice caused by an inflammatory response within the tumor microenvironment.29 Amgen is also planning to combine AMG 510 (10) with the SHP2 inhibitor RMC-4630 of Revolution Medicine to enhance response and tumor regression.31 SHP2 inhibition is known to enhance the covalent target modification of KRasG12C switch-II pocket inhibitors by decreasing KRas GTP loading and is therefore a potential treatment strategy for patients with KRas-mutant cancer.32–34

Fig. 4. Development of AMG 510 (10). a, Chemical structures of indole lead 1Amgen (9), ARS-1620 scaffold and AMG 510 (10). b, Biochemical and cellular data as well as drug-like properties of compounds shown in Fig. 4a. c, Structural comparison of the KRasG12C:GDP binding modes of ARS-1620 (8) (left, pdb id ; 5v9u) and indole lead 1Amgen (9) (right, pdb id ; 6p8z). d, Co-crystal structure of KRasG12C:GDP bound to AMG 510 (10) (left, pdb id ; 6oim) and key interactions (right).

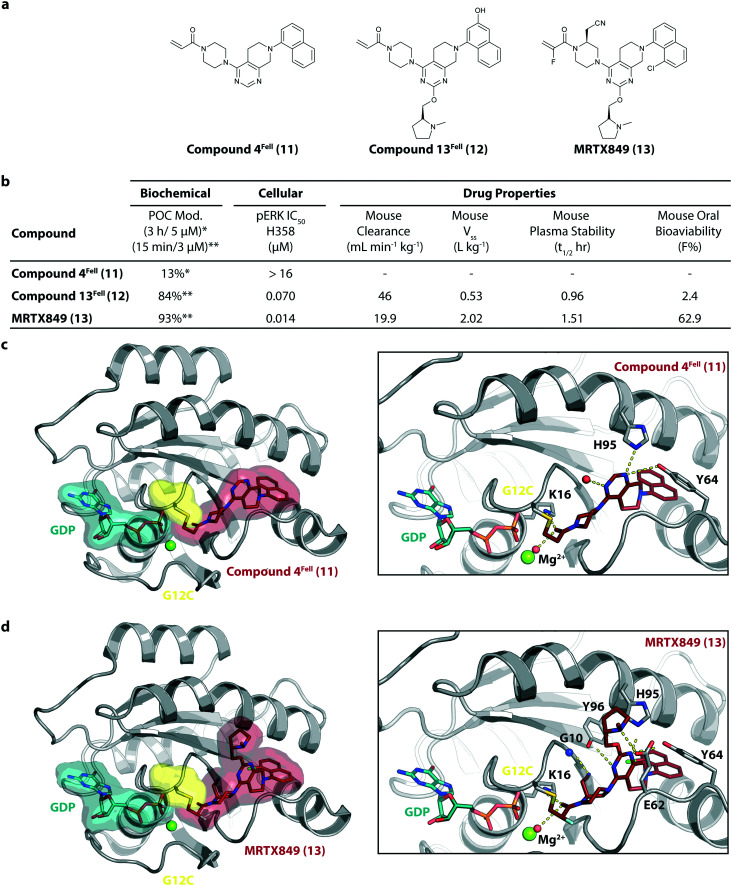

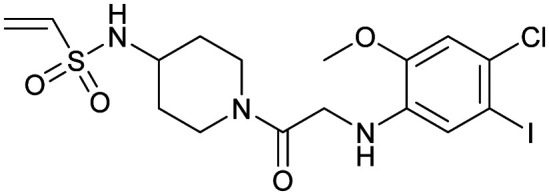

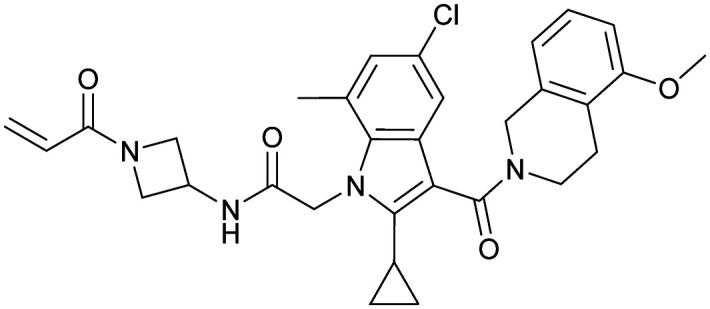

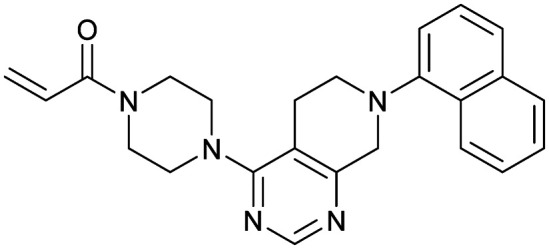

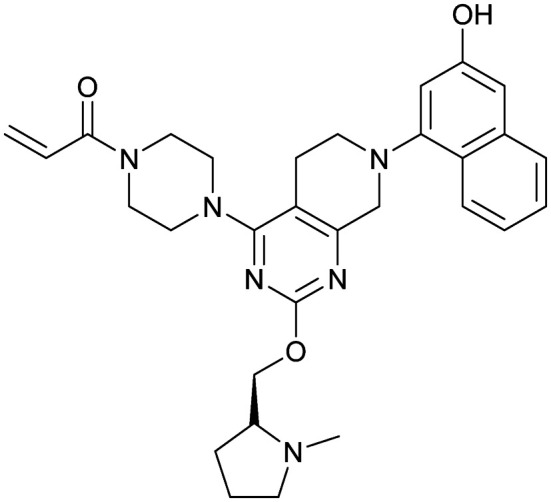

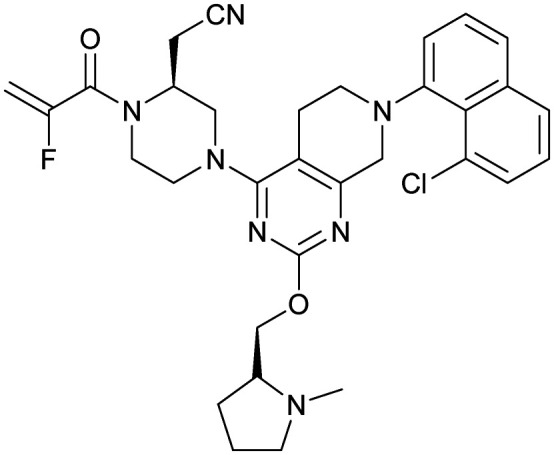

MRTX849 (13), developed by Mirati Therapeutics, entered clinical trials in humans in January 2019 (NCT03785249).35 In collaboration with Array BioPharma, Mirati Therapeutics identified a series of tetrahydropyridopyrimidines as irreversible covalent inhibitors of KRasG12C that led to the discovery of compound 4Fell (11).36 The co-crystal structure of compound 4Fell (11) (pdb id ; 6n2j) bound to KRasG12C confirmed the covalent modification of the mutant cysteine trapping KRas in the inactive conformation (Fig. 5c) with micromolar inhibition of downstream Ras signaling (pERK IC50 ≥ 16 μM). Modifications of the naphthyl ring as well as the C2 substituent led to a significant improvement in solubility and cellular potency (pERK IC50 = 70 nM). A structure-based drug design approach, including optimization with respect to favorable drug-like properties, finally led to the discovery of MRTX849 (13) (Fig. 5a).37,38 The 8-chloronaphtyl substituent of MRTX849 fills the lipophilic pocket as previously described for compound 4Fell (11). Additional hydrogen bonds between the cyanomethyl group and the backbone NH of Gly10 as well as between the pyrrolidine moiety and Glu62 were observed (Fig. 5d, pdb id ; 6ut0). MRTX849 (13) inhibits Ras signaling including ERK phosphorylation in H358 lung cells as well as MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cells that harbor the G12C mutation with IC50 values in the nanomolar range. In preclinical experiments, MRTX849 (13) inhibited KRas signaling and tumor growth in mice and patient-derived xenograft models of KRasG12C mutant human tumor cells in a dose-dependent manner. Tumor regression was observed in 17 out of 26 (65%) KRasG12C-positive cell line- and patient-derived xenograft models from multiple tumor types.37 In a phase 1/2 study involving patients with advanced mutant KRasG12C solid tumors, mostly NSCLC and colorectal carcinoma, MRTX849 (13) achieved a partial response (PR) in four out of twelve patients and eight showed stable disease (SD).39 After 6 weeks of treatment, in patients with partial response who received 600 mg MRTX849 (13) twice a day, a tumor reduction of 33% (NSCLC) and 37% (CRC) was observed and after twelve weeks a further tumor shrinkage to 47% in case of the CRC patient was detected.37 MRTX849 (13) is also being tested in combination with agents that target RTKs, mTOR, or the cell cycle to increase the anti-tumor activity. A phase 1/2 combination trial of the experimental SHP2 inhibitor TNO155 of Novartis with MRTX849 (13) is planned for 2020.31,39

Fig. 5. Development of MRTX849 (13). a, Chemical structures of compound 4Fell (11), compound 13Fell (12) and MRTX849 (13). b, Biochemical and cellular data as well as drug-like properties of compounds shown in Fig. 5a. c, Co-crystal structure of KRasG12C:GDP bound to compound 4Fell (11) (left, pdb id ; 6n2j) and key interactions (right). d, Co-crystal structure of KRasG12C:GDP bound to MRTX849 (13) (left, pdb id ; 6ut0) and key interactions (right).

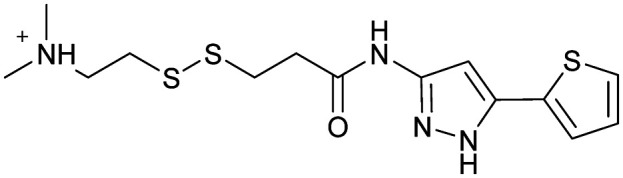

JNJ-74699157 (ARS-3248, 14), developed by Johnson and Johnson and Wellspring Bioscience, entered clinical trials in humans in July 2019 (NCT04006301).40 However, no further data is available for this compound as of now.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Ras genes are the most commonly mutated oncogenes and despite decades of drug discovery research, efforts to develop small molecules directly targeting Ras have so far failed due to lack of clear druggable pockets. In 2013, Shokat and colleagues identified cysteine-reactive molecules that bind covalently to the G12C mutant of KRas in the previously unknown allosteric switch-II pocket, thereby trapping the protein in the inactive GDP-bound state. After more than 30 years of setbacks in all efforts to directly target Ras, this finding led to an impressive effort within the academic and industrial world to develop potent KRas G12C inhibitors and finally led to the discovery of three small molecules, AMG 510, MRTX849, and JNJ-74699157 (ARS-3248) from three independent companies that recently reached clinical testing in humans. Whereas no information is available for JNJ-74699157 (ARS-3248), AMG 510 as well as MRTX849 demonstrated safety and clinical activity in patients with KRasG12C mutant tumors. Due to the moderate side effects of KRasG12C specific inhibitors, Amgen as well as Mirati Therapeutics are planning drug combination studies with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and other targeted agents to enhance anti-tumor activity.

These findings finally provide valuable insights concerning the therapeutic susceptibility of the KRas G12C mutant in cancer and therefore represent a major milestone in personalized/precision medicine.41 In principle, this approach can serve as the starting point for drug discovery efforts targeting other common KRas mutations such as G12D, G13D, or G13C, finally paving the way to tackle one of the major oncogenes in human cancer.

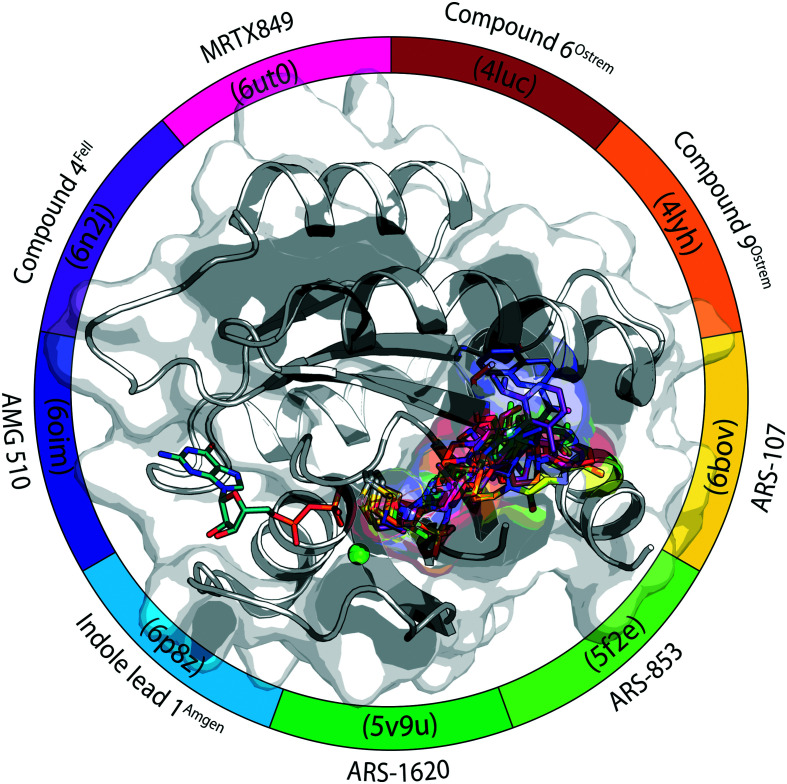

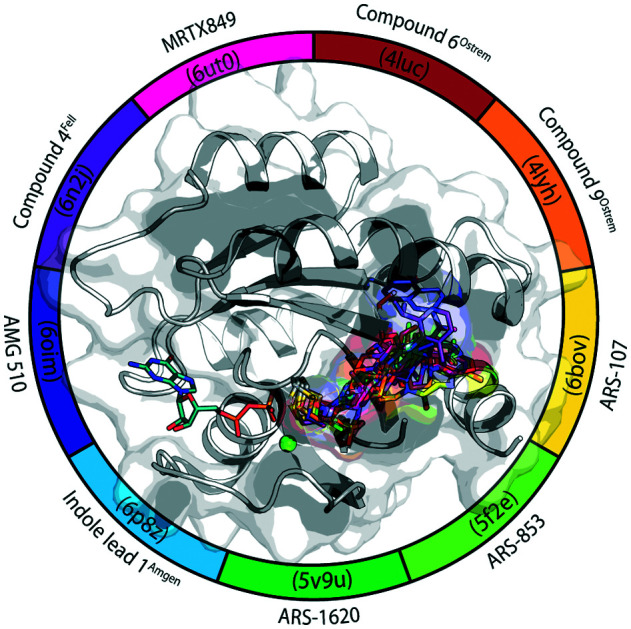

All compounds that are part of this review are summarized in Fig. 6 and Table 1. In the supporting information, a corresponding PyMOL session is provided.42

Fig. 6. KRasG12C switch-II pocket inhibitors.

Table 1. KRasG12C switch-II pocket inhibitors.

| Compound name in publication | Numbering in this article | Chemical structure | PDB ID | Reference | Company/origin | Phase | ID |

| 2E07 | 1 |

|

— | Ostrem et al. (2013)22 | Shokat Laboratory | — | — |

| 6H05 | 2 |

|

— | Ostrem et al. (2013)22 | Shokat Laboratory | — | — |

| Compound 6 | 3 |

|

4luc | Ostrem et al. (2013)22 | Shokat Laboratory | — | — |

| Compound 9 | 4 |

|

4lyh | Ostrem et al. (2013)22 | Shokat Laboratory | — | — |

| 4lyj | |||||||

| Compound 12 | 5 |

|

— | Ostrem et al. (2013)22 | Shokat Laboratory | — | — |

| ARS-107 | 6 |

|

6b0v | Patricelli et al. (2016)23 | Wellspring Bioscience | — | — |

| ARS-853 | 7 |

|

5f2e | Patricelli et al. (2016)23 | Wellspring Bioscience | — | — |

| ARS-1620 | 8 |

|

5v9u | Janes et al. (2018)24 | Wellspring Bioscience | — | — |

| Indole lead 1 | 9 |

|

6p8z | Shin et al. (2019)27 | Amgen | — | — |

| AMG 510 | 10 |

|

6oim | Canon et al. (2019)29 | Amgen | I/II | NCT03600883 |

| NCT04185883 | |||||||

| Compound 4 | 11 |

|

6n2j | Fell et al. (2018)36 | Array BioPharma | — | — |

| Mirati Therapeutics | |||||||

| Compound 13 | 12 |

|

— | Fell et al. (2018)36 | Array BioPharma | — | — |

| Mirati Therapeutics | |||||||

| MRTX849 | 13 |

|

6ut0 | Hallin et al. (2019)37 | Mirati Therapeutics | I/II | NCT03785249 |

| Fell et al. (2020)38 | |||||||

| JNJ-74699157 (ARS-3248) | 14 | — | — | — | J&J Wellspring Bioscience | I | NCT04006301 |

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was co-funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; RA 1055/5-1) and the Drug Discovery Hub Dortmund (DDHD).

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d0md00096e

References

- Cox A. D., Fesik S. W., Kimmelman A. C., Luo J., Der C. J. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2014;13:828–851. doi: 10.1038/nrd4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter I. R., Wittinghofer A. Science. 2001;294:1299–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1062023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs G. A., Der C. J., Rossman K. L. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:1287–1292. doi: 10.1242/jcs.182873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffzek K., Ahmadian M. R., Kabsch W., Wiesmuller L., Lautwein A., Schmitz F., Wittinghofer A. Science. 1997;277:333–338. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrman G., Holzapfel G., Fetics S., Mattos C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:4931–4936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912226107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. C., Manandhar A., Carrasco M. A., Gurbani D., Gondi S., Westover K. D. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015;13:1325–1335. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John J., Sohmen R., Feuerstein J., Linke R., Wittinghofer A., Goody R. S. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6058–6065. doi: 10.1021/bi00477a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traut T. W. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1994;140:1–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00928361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M. P., Jeganathan S., Heidrich A., Campos J., Goody R. S. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3687. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03973-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. M., Westover K. D., Ficarro S. B., Harrison R. A., Choi H. G., Pacold M. E., Carrasco M., Hunter J., Kim N. D., Xie T., Sim T., Janne P. A., Meyerson M., Marto J. A., Engen J. R., Gray N. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:199–204. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Lu J., Hunter J., Li L., Scott D., Choi H. G., Lim S. M., Manandhar A., Gondi S., Sim T., Westover K. D., Gray N. S. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;8:61–66. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker F. J., Rocks O., Vartak N., Menninger S., Hedberg C., Balamurugan R., Wetzel S., Renner S., Gerauer M., Scholermann B., Rusch M., Kramer J. W., Rauh D., Coates G. W., Brunsveld L., Bastiaens P. I., Waldmann H. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt N., Hamilton A. D., Sebti S. M. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:775–791. doi: 10.1038/nrc3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte D. B., Kirschmeier P., Hockenberry T. N., Nunez-Oliva I., James L., Catino J. J., Bishop W. R., Pai J. K. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:14459–14464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann G., Papke B., Ismail S., Vartak N., Chandra A., Hoffmann M., Hahn S. A., Triola G., Wittinghofer A., Bastiaens P. I., Waldmann H. Nature. 2013;497:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nature12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke B., Murarka S., Vogel H. A., Martin-Gago P., Kovacevic M., Truxius D. C., Fansa E. K., Ismail S., Zimmermann G., Heinelt K., Schultz-Fademrecht C., Al Saabi A., Baumann M., Nussbaumer P., Wittinghofer A., Waldmann H., Bastiaens P. I. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11360. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Gago P., Fansa E. K., Klein C. H., Murarka S., Janning P., Schurmann M., Metz M., Ismail S., Schultz-Fademrecht C., Baumann M., Bastiaens P. I., Wittinghofer A., Waldmann H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:2423–2428. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicaltrials.gov, A Study to Test Different Doses of BI 1701963 Alone and Combined With Trametinib in Patients With Different Types of Advanced Cancer (Solid Tumours With KRAS Mutation), 2019, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04111458.

- Jeng H. H., Taylor L. J., Bar-Sagi D. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:1168. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margarit S. M., Sondermann H., Hall B. E., Nagar B., Hoelz A., Pirruccello M., Bar-Sagi D., Kuriyan J. Cell. 2003;112:685–695. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goody R. S., Muller M. P., Rauh D. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019;26:1338–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrem J. M., Peters U., Sos M. L., Wells J. A., Shokat K. M. Nature. 2013;503:548–551. doi: 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patricelli M. P., Janes M. R., Li L. S., Hansen R., Peters U., Kessler L. V., Chen Y., Kucharski J. M., Feng J., Ely T., Chen J. H., Firdaus S. J., Babbar A., Ren P., Liu Y. Cancer Discovery. 2016;6:316–329. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes M. R., Zhang J., Li L. S., Hansen R., Peters U., Guo X., Chen Y., Babbar A., Firdaus S. J., Darjania L., Feng J., Chen J. H., Li S., Li S., Long Y. O., Thach C., Liu Y., Zarieh A., Ely T., Kucharski J. M., Kessler L. V., Wu T., Yu K., Wang Y., Yao Y., Deng X., Zarrinkar P. P., Brehmer D., Dhanak D., Lorenzi M. V., Hu-Lowe D., Patricelli M. P., Ren P., Liu Y. Cell. 2018;172:578–589.e517. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen R., Peters U. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018;25:454–462. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicaltrials.gov, A Phase 1/2, Study Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, PK, and Efficacy of AMG 510 in Subjects With Solid Tumors With a Specific KRAS Mutation, 2018, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03600883.

- Shin Y., Jeong J. W., Wurz R. P., Achanta P., Arvedson T., Bartberger M. D., Campuzano I. D. G., Fucini R., Hansen S. K., Ingersoll J., Iwig J. S., Lipford J. R., Ma V., Kopecky D. J., McCarter J., San Miguel T., Mohr C., Sabet S., Saiki A. Y., Sawayama A., Sethofer S., Tegley C. M., Volak L. P., Yang K., Lanman B. A., Erlanson D. A., Cee V. J. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;10:1302–1308. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanman B. A., Allen J. R., Allen J. G., Amegadzie A. K., Ashton K. S., Booker S. K., Chen J. J., Chen N., Frohn M. J., Goodman G., Kopecky D. J., Liu L., Lopez P., Low J. D., Ma V., Minatti A. E., Nguyen T. T., Nishimura N., Pickrell A. J., Reed A. B., Shin Y., Siegmund A. C., Tamayo N. A., Tegley C. M., Walton M. C., Wang H. L., Wurz R. P., Xue M., Yang K. C., Achanta P., Bartberger M. D., Canon J., Hollis L. S., McCarter J. D., Mohr C., Rex K., Saiki A. Y., San Miguel T., Volak L. P., Wang K. H., Whittington D. A., Zech S. G., Lipford J. R., Cee V. J. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:52–65. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canon J., Rex K., Saiki A. Y., Mohr C., Cooke K., Bagal D., Gaida K., Holt T., Knutson C. G., Koppada N., Lanman B. A., Werner J., Rapaport A. S., San Miguel T., Ortiz R., Osgood T., Sun J. R., Zhu X., McCarter J. D., Volak L. P., Houk B. E., Fakih M. G., O'Neil B. H., Price T. J., Falchook G. S., Desai J., Kuo J., Govindan R., Hong D. S., Ouyang W., Henary H., Arvedson T., Cee V. J., Lipford J. R. Nature. 2019;575:217–223. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicaltrials.gov, AMG 510 Activity in Subjects With Advanced Solid Tumors With KRAS p.G12C Mutation, 2019, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04185883.

- Mullard A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2019;18:887–891. doi: 10.1038/d41573-019-00195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainardi S., Mulero-Sanchez A., Prahallad A., Germano G., Bosma A., Krimpenfort P., Lieftink C., Steinberg J. D., de Wit N., Goncalves-Ribeiro S., Nadal E., Bardelli A., Villanueva A., Bernards R. Nat. Med. 2018;24:961–967. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruess D. A., Heynen G. J., Ciecielski K. J., Ai J., Berninger A., Kabacaoglu D., Gorgulu K., Dantes Z., Wormann S. M., Diakopoulos K. N., Karpathaki A. F., Kowalska M., Kaya-Aksoy E., Song L., van der Laan E. A. Z., Lopez-Alberca M. P., Nazare M., Reichert M., Saur D., Erkan M. M., Hopt U. T., Sainz, Jr. B., Birchmeier W., Schmid R. M., Lesina M., Algul H. Nat. Med. 2018;24:954–960. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G. S., Zhou J., Liu J. B., Wu Z., Xu X., Li T., Xu D., Schumacher S. E., Puschhof J., McFarland J., Zou C., Dulak A., Henderson L., Xu P., O'Day E., Rendak R., Liao W. L., Cecchi F., Hembrough T., Schwartz S., Szeto C., Rustgi A. K., Wong K. K., Diehl J. A., Jensen K., Graziano F., Ruzzo A., Fereshetian S., Mertins P., Carr S. A., Beroukhim R., Nakamura K., Oki E., Watanabe M., Baba H., Imamura Y., Catenacci D., Bass A. J. Nat. Med. 2018;24:968–977. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0022-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicaltrials.gov, Phase 1/2 Study of MRTX849 in Patients With Cancer Having a KRAS G12C Mutation, 2018, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03785249.

- Fell J. B., Fischer J. P., Baer B. R., Ballard J., Blake J. F., Bouhana K., Brandhuber B. J., Briere D. M., Burgess L. E., Burkard M. R., Chiang H., Chicarelli M. J., Davidson K., Gaudino J. J., Hallin J., Hanson L., Hee K., Hicken E. J., Hinklin R. J., Marx M. A., Mejia M. J., Olson P., Savechenkov P., Sudhakar N., Tang T. P., Vigers G. P., Zecca H., Christensen J. G. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;9:1230–1234. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallin J., Engstrom L. D., Hargis L., Calinisan A., Aranda R., Briere D. M., Sudhakar N., Bowcut V., Baer B. R., Ballard J. A., Burkard M. R., Fell J. B., Fischer J. P., Vigers G. P., Xue Y., Gatto S., Fernandez-Banet J., Pavlicek A., Velastagui K., Chao R. C., Barton J., Pierobon M., Baldelli E., Patricoin 3rd E. F., Cassidy D. P., Marx M. A., Rybkin I. I., Johnson M. L., Ou S. I., Lito P., Papadopoulos K. P., Janne P. A., Olson P., Christensen J. G. Cancer Discovery. 2020;10:54–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell J. B., Fischer J. P., Baer B. R., Blake J. F., Bouhana K., Briere D. M., Brown K. D., Burgess L. E., Burns A. C., Burkard M. R., Chiang H., Chicarelli M. J., Cook A. W., Gaudino J. J., Hallin J., Hanson L., Hartley D. P., Hicken E. J., Hingorani G. P., Hinklin R. J., Mejia M. J., Olson P., Otten J. N., Rhodes S. P., Rodriguez M. E., Savechenkov P., Smith D. J., Sudhakar N., Sullivan F. X., Tang T. P., Vigers G. P., Wollenberg L., Christensen J. G., Marx M. A. J. Med. Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero D. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020;17:6. [Google Scholar]

- Clinicaltrials.gov, First-in-Human Study of JNJ-74699157 in Participants With Tumors Harboring the KRAS G12C Mutation, 2019, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04006301.

- Murugan A. K., Grieco M., Tsuchida N. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019;59:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger, LLC.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.