Abstract

Objective

Practice parameters recommend systematic assessment of depression symptoms over the course of treatment to inform treatment planning; however, there are currently no guidelines regarding how to use symptom monitoring to guide treatment decisions for psychotherapy. The current study compared two time points (week 4 and week 8) for assessing symptoms during interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (IPT-A) and explored four algorithms that use the symptom assessments to select the subsequent treatment.

Method

Forty adolescents (aged 12–17 years) with a depression diagnosis began IPT-A with an initial treatment plan of 12 sessions delivered over 16 weeks. Adolescents were randomized to a week 4 or week 8 decision point for considering a change in treatment. Insufficient responders at either time point were randomized a second time to increased frequency of IPT-A (twice per week) or addition of fluoxetine. Measures were administered at baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16.

Results

The week 4 decision point for assessing response and implementing treatment augmentation for insufficient responders was more efficacious for reducing depression symptoms than the week 8 decision point. There were significant differences between algorithms in depression and psychosocial functioning outcomes.

Conclusion

Therapists implementing IPT-A should routinely monitor depression symptoms and consider augmenting treatment for insufficient responders as early as week 4 of treatment.

Clinical Trial Registration Information

An Adaptive Treatment Strategy for Adolescent Depression. https://clinicaltrials.gov; NCT02017535.

Keywords: depression, psychotherapy, fluoxetine, symptom assessment, algorithms

Depression is a common psychiatric disorder during adolescence; the 12-month prevalence of a major depressive episode is approximately 11%.1 This prevalence rate is particularly concerning given the impact that depression has on adolescents’ lives. It is the largest diagnostic predictor of death by suicide during adolescence.2 It increases risk for substance use disorders and physical health problems, such as obesity, and it is associated with significant psychosocial impairment, including academic difficulties and difficulties in relationships with family and peers.3,4

There are now a number of evidence-based treatments for adolescents with depression, including psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, and their combination.5 Despite progress in treatment development, approximately 30% to 50% of adolescents who receive these treatments do not respond.6,7 Similar to the small effect sizes found for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs),8 a recent meta-analysis of randomized trials of youth psychotherapy found that psychotherapy for depression had the weakest effect size, on average, compared to psychotherapies for other common childhood disorders.9 To address this problem, practice parameters recommend systematic and routine assessment and monitoring of depression symptoms over the course of treatment to inform treatment planning, including decisions regarding whether to switch or augment treatment.5,10 Algorithms have been developed to guide pharmacological treatment of depression (eg, Texas Medication Algorithm Project and Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression Study [STAR*D]).11,12 Psychotherapy, however, currently has no empirically derived guidelines to direct therapists regarding how to use symptom assessments to guide subsequent treatment decisions. At the time of the conceptualization of the current study, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommended a multidisciplinary team review for adolescents with mild depression who have not responded to psychotherapy after 3 months, and review after 4 to 6 sessions for adolescents with moderate to severe depression, but did not operationalize response or provide guidance regarding how to adapt the treatment plan for nonresponders.13 As a consequence, decisions to continue, switch, or augment treatment may be made in a trial-and-error fashion, which could result in extended time to remission or increased cost or other burdens to families.

Developing an algorithm for psychotherapy requires identifying the following: (1) when, during the course of psychotherapy, to administer symptom assessments; (2) what degree of symptom improvement is needed to decide whether a change in the treatment plan is needed; and (3) what subsequent intervention to provide for insufficient responders. We selected interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (IPT-A) as the therapy of focus. IPT-A aims to treat depression by teaching adolescents interpersonal skills needed to improve their relationships and to address one or more of four interpersonal problem areas: grief, role disputes, role transitions, and interpersonal deficits.14 IPT-A was selected because of its strong empirical support and successful implementation in real-world settings.6,15,16 In previous trials, 50% to 75% of adolescents met criteria for remission at the end of the trial.6,17 Identifying specific critical treatment decision points is a particularly important first step,18 as decision points that are specifically operationalized are more easily replicated and disseminated in general clinical practice.19 In previous research, we identified two possible critical decision points for adolescents receiving IPT-A.20 Using data from a previous trial of IPT-A,6 we conducted receiver operating characteristic analysis to identify the time point and degree of reduction in depressive symptoms that best predicted treatment response at the end of the trial (week 16).We found that adolescents who had begun a 12-session course of IPT-A delivered over the course of 16 weeks could be classified as likely to respond or not likely to respond at week 4 or week 8 of treatment.20 At week 4, a cutoff of a 20% reduction in depressive symptoms (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HRSD])21 from baseline was found to represent the best combined sensitivity and specificity for predicting response status at the end of the 16-week trial. That is, adolescents who demonstrated at least a 20% reduction in HRSD score could be expected to be full treatment responders at the end of 16 weeks, whereas adolescents who had demonstrated less than a 20% reduction in symptoms at week 4 were not likely to be full responders at 16 weeks and could be expected to need a change to their treatment plan to bring about a full treatment response. At week 8, a 40% reduction in HRSD represented the best combined sensitivity and specificity for predicting week 16 treatment response.

In considering what subsequent intervention to provide for insufficient responders, we selected two augmentation strategies: adding an antidepressant medication, fluoxetine, or increasing the number of IPT-A sessions by delivering them twice per week (ie, increase from 12 to 16 sessions). Three studies have found that a combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication was significantly more efficacious than monotherapy for reducing depression symptoms in adolescents.7,22,23 Thus, adding antidepressant medication to IPT-A may be an effective option for insufficient responders to IPT-A. Fluoxetine was the medication selected, given the literature supporting its efficacy, tolerability, and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use with adolescents.7,24–26 Studies have also found that psychotherapy delivered twice per week is an effective treatment approach for depression.27–30 Neither of these treatment augmentation strategies has yet been evaluated in the context of treatment with IPT-A.

A previous publication described the feasibility and acceptability of the four IPT-A algorithms.31 The primary aim of the present article is to report the clinical and psychosocial outcomes of the study, and to compare the efficacy of the week 4 versus week 8 decision point for identifying and augmenting treatment for potential insufficient responders to IPT-A. In secondary exploratory analyses, we also examined the clinical and psychosocial outcomes of each of the four IPT-A algorithms (see Table 1 for descriptions of the algorithms).

TABLE 1.

The Four Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A) Algorithms

| Algorithm 1: First treat with weekly IPT-A with an initial treatment plan of 12 sessions. If at week 4 the adolescent has shown at least a 20% reduction in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) score, maintain initial treatment plan of 12 IPT-A sessions. If the adolescent has not shown at least a 20% reduction in HRSD score, augment treatment by adding fluoxetine and continuing IPT-A (12 sessions total). |

| Algorithm 2: First treat with weekly IPT-A with an initial treatment plan of 12 sessions. If at week 4 the adolescent has shown at least a 20% reduction in HRSD score, maintain initial treatment plan of 12 IPT-A sessions. If the adolescent has not shown at least a 20% reduction in HRSD score, increase dose of IPT-A by scheduling sessions twice a week for 4 weeks; then return to weekly IPT-A (16 sessions total). |

| Algorithm 3: First treat with weekly IPT-A with an initial treatment plan of 12 sessions. If at week 8 the adolescent has shown at least a 40% reduction in HRSD score, maintain initial treatment plan of 12 IPT-A sessions. If the adolescent has not shown at least a 40% reduction in HRSD score, augment treatment by adding fluoxetine and continuing IPT-A (12 sessions total). |

| Algorithm 4: First treat with weekly IPT-A with an initial treatment plan of 12 sessions. If at week 8 the adolescent has shown at least a 40% reduction in HRSD score, maintain initial treatment plan of 12 IPT-A sessions. If the adolescent has not shown at least a 40% reduction in HRSD score, increase dose of IPT-A by scheduling sessions twice a week for 4 weeks; then return to weekly IPT-A (16 sessions total). |

METHOD

Study Design

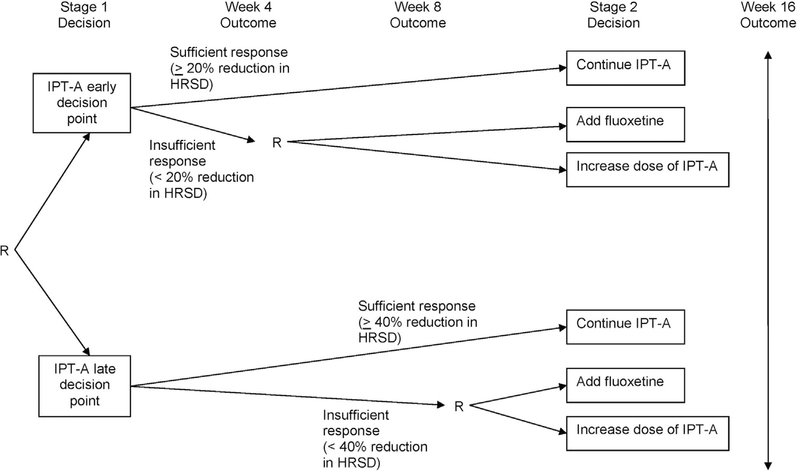

A full description of the study design and methods is provided in Gunlicks-Stoessel et al.31 The study was a 16-week sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) (Figure 1) carried out at the site’s Ambulatory Research Center. In SMARTs, research participants can be randomized multiple times, and these randomizations occur sequentially through time at selected critical decision points. The results of the SMART are then used to define the decision rules that make up the treatment algorithm.32,33 All eligible adolescents began treatment with an initial treatment plan of 12 IPT-A sessions. At week 4, adolescents were randomized with equal probability to an early decision point (week 4) or late decision point (week 8) for identifying potential nonresponders to IPT-A. Adolescents who were classified as insufficient responders (<20% reduction in HRSD score at week 4 or <40% reduction in HRSD score at week 8) were randomized a second time, with equal probability, to the addition of fluoxetine or an additional 4 IPT-A sessions delivered twice per week (ie, increase from 12 to 16 sessions). Adolescents who were classified as sufficient responders continued with the original treatment plan of 12 sessions of IPT-A. The HRSD was administered by the therapists during the week 4 and week 8 therapy sessions. Research outcome measures were administered by independent evaluators who were blinded to treatment condition at baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16. The study was approved by the site’s institutional review board. Parents gave written informed consent, and adolescents gave written informed assent (and written consent after they turned age 18 years).

FIGURE 1. Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART) Design.

Note: HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IPT-A = interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents; R = randomization.

Participants

Adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 years were recruited from the Minneapolis metropolitan area via flyers, radio advertisements, newspaper advertisements, school referrals, and clinic referrals. Parents of potential participants completed a telephone screen to provide adolescents’ developmental, social, and treatment history, as well as current psychiatric symptoms. Adolescents who did not meet exclusion criteria on the telephone screen were invited to participate in a consent meeting and baseline evaluation to determine eligibility.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: age 12 to 17 years; DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified (NOS); significant symptoms of depression (Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised raw score >35); impairment in general functioning (Children’s Global Assessment Scale score <65); and English-speaking adolescent and parent. Exclusion criteria were as follows: DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychosis, substance abuse, obsessive compulsive disorder, conduct disorder, eating disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder; intellectual disability disorder; active suicidal ideation with a plan and/or intent; already receiving treatment for depression; taking medication for a psychiatric diagnosis other than attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (adolescents taking a stable dose of stimulants [≥3 months] were included); nonresponder to an adequate trial of IPT-A or fluoxetine in the past; and female adolescents who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or having unprotected sexual intercourse.

Measures

Interview measures were administered by independent evaluators who were blinded to treatment condition. Training in the interview measures included didactics, observing a trained evaluator conducting an assessment, being observed by a trained evaluator until interview administration was assessed to be adequate, and participating in reliability coding of previously recorded interview measures.

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS)34 is a clinician-administered semi-structured interview that assesses current episode and lifetime history of psychiatric diagnoses based on DSM-IV criteria. Adolescents and their parents were interviewed separately, and a consensus on diagnosis was formed based on best estimate of the two reports. Interrater reliability was 100% for depression diagnosis, 84.63% for depression symptom ratings, and 96% for the screen items.

Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised

The Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R)35 is a clinician-administered semistructured interview that assesses symptoms of depression experienced during the previous 2 weeks. The interview is conducted with the adolescent and the parent separately, and a summary score is created for each symptom based on best estimate of the two reports. The CDRS-R has been found to have good reliability and validity.36

Children’s Global Assessment Scale

The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS)37 is a clinician-rated scale that assesses overall functioning and impairment in all aspects of the child’s life. It has been found to be a reliable instrument for assessing impairment in children with psychiatric disorders.37

Social Adjustment Scale–Self Report

The Social Adjustment Scale–Self Report (SAS-SR)38 is a self-report measure that assesses social functioning in the following four categories: school, friends, family, and dating. The average of all items also provides an overall index of social impairment. Higher scores indicate more difficulties with social adjustment.

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale

Suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and engagement in self-injurious behavior were assessed using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS),39 a clinician-administered standardized suicide rating system that was conducted with the adolescent. Treatment-emergent events were defined as any new-onset or worsening symptoms. A harm-related adverse event was defined as an event that involved harm to self, including treatment-emergent nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior, worsening suicidal ideation, or a suicide attempt of any lethality; or harm to others, including aggressive or violent ideation or action towards another person or property. A suicide-related adverse event was defined as worsening suicidal ideation, a suicide attempt, or both.

Intervention

Initial Treatment

IPT-A is a 12-session evidence-based psychotherapy that aims to decrease depressive symptoms by helping adolescents improve their relationships and interpersonal interactions.14 It addresses one or more of four interpersonal problem areas: grief, role disputes, role transitions, and interpersonal deficits. During treatment, the therapist identifies and teaches specific communication and interpersonal problem-solving skills that can improve the interpersonal difficulties that are most closely related to the onset or maintenance of depression. The adolescent role-plays these skills in session and works toward implementing them in their current relationships. Parents are involved in treatment, as appropriate, to learn about the IPT-A model, to provide opportunities for adolescents to practice their skills, and to learn communication and interpersonal problem solving strategies to use with their adolescents. Adolescents began the study with an initial treatment plan of 12 weekly sessions delivered over the course of 16 weeks to allow scheduling flexibility for missed/canceled appointments.

Sufficient/Insufficient Response Measure

The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)21,40 was used to measure sufficient/insufficient response to IPT-A. The HRSD is a clinician-administered semistructured interview measure that has been used with both adult and adolescent populations.6,17 It was selected as the response measure because it was the outcome measure used in the previous clinical trial of IPT-A from which the algorithm was developed. It has the additional advantage of being a free measure, which facilitates its use in clinical practice. In contrast to the research measures administered by independent evaluators (eg, CDRS-R), the HRSD was administered by therapists during the therapy sessions. As such, the HRSD was considered to be part of treatment and was not a research outcome measure. As a standardized interview assessment measure, use of the HRSD minimizes the therapist and patient bias that can occur during progress monitoring. Therapists administered the HRSD at weeks 1, 4, and 8, and they calculated the percent change in HRSD from week 1 to week 4, and from week 1 to week 8. Therapists’ HRSD ratings at week 4 and week 8 were significantly correlated with independent evaluator ratings on the CDRS-R at those time points (week 4: r = 0.83, p = .000; week 8: r = 0.58, p = .002).

Secondary Treatments

Adolescents who demonstrated sufficient symptom reduction at their randomized decision time point (≥20% reduction in HRSD at week 4 or ≥40% reduction in HRSD at week 8) continued the initial treatment plan of 12 IPT-A sessions delivered within 16 weeks. Adolescents who demonstrated insufficient symptom reduction at their randomized decision time point (<20% reduction in HRSD at week 4 or <40% reduction in HRSD at week 8) were randomized to the addition of fluoxetine or 4 additional IPT-A sessions delivered twice per week (ie, total of 16 sessions).

The dosage schedule for fluoxetine followed published guidelines, but allowed for flexibility to balance efficacy and side effects: 10 mg per day for the first week and 20 mg per day for the following 5 weeks. If no treatment response was observed by the sixth week, the dosage could be increased to 40 mg per day.41 Medication sessions were scheduled weekly for the first 4 weeks and every other week thereafter. Sessions included assessment of vital signs, adverse effects, safety, and symptomatic response.

Statistical Analyses

The main effect of week 4 versus week 8 decision point on week 16 primary outcome (CDRS-R) and secondary outcomes (CGAS, SAS-SR) were evaluated using linear regressions with covariates for decision point (4 versus 8 weeks) and baseline score on the outcome measure. Separate models were fit for each outcome.

As an exploratory analysis, we estimated the expected (ie, mean) outcomes if all participants in the population were to follow each embedded algorithm in the trial design. Weighted linear regressions were used to estimate the anticipated primary outcome (CDRS-R) and secondary outcomes (CGAS, SAS-SR) at week 16 for the 4 algorithms embedded in the trial design (Table 1). Separate models were fit for each outcome. Each model included an indicator for each algorithm and adjusted for the baseline measure of each outcome. Insufficient responders were given a weight of 4 (to account for the 1 in 4 chance of following their assigned sequence of treatments) while sufficient responders were given a weight of 2 (to account for the 1 in 2 chance of receiving their assigned sequence of treatments).42–44 A weighted analysis is needed because, for any given adaptive treatment strategy, all sufficient responders who are randomized to the given assessment time (eg, 4 weeks) are consistent with the algorithm, but only half of insufficient responders are (half are randomized to increased IPT-A, whereas half are randomized to add fluoxetine). That is, sufficient responders are overrepresented in our sample of participants consistent with a particular algorithm. Therefore, insufficient responders are given larger weight in the analysis. This is conceptually similar to survey weights that are used to correct for over- or underrepresentation of subgroups in opinion polls. Sandwich variance estimators were used to obtain standard error estimates to account for the fact that research participants may contribute to the estimation of more than one algorithm.

Missing data were replaced using multiple imputation. The imputation model included all of the longitudinal outcome measures included in the subsequent analyses; baseline sample characteristics, treatment indicators, and other psychosocial time-varying variables thought to be associated with outcomes. Twenty imputed data sets were generated using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method. Rubin’s combining rules were used combine point estimates and to obtain measures of uncertainty from analyses from the multiple imputed datasets.45

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All tests were 2-sided, with statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. As these analyses are hypothesis generating, no adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed. Cohen’s effect size of f 2 was calculated for the multiple regressions. An effect size of f 2 = 0.02 is defined as small, 0.15 as medium, and 0.35 as large.46

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Retention

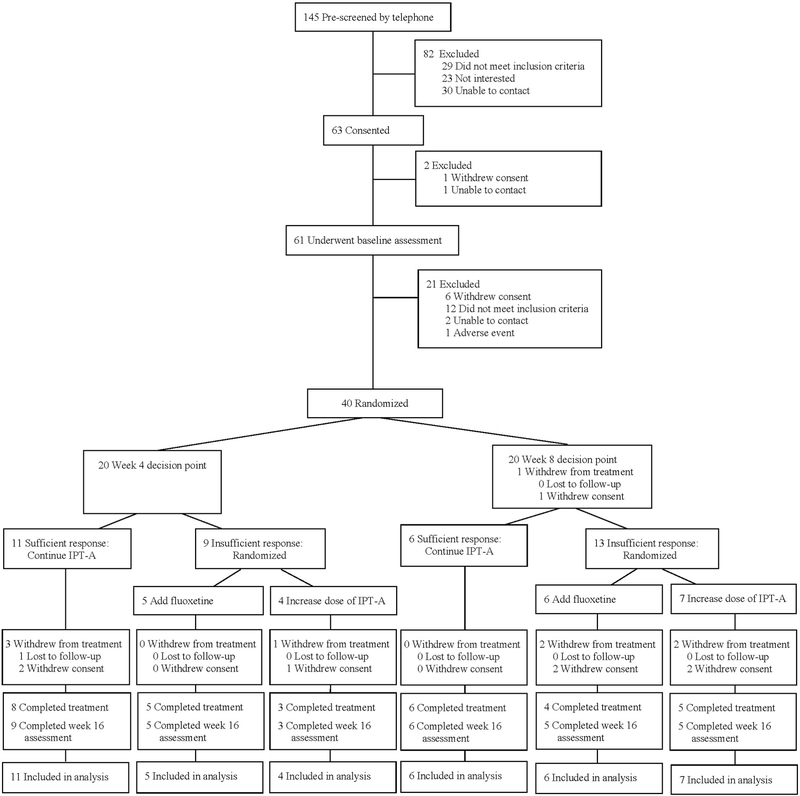

A total of 145 individuals were screened by telephone. Of those, 63 provided consent/assent, 61 completed the baseline assessment, and 40 were eligible and participated in the first randomization (see CONSORT diagram, Figure 2). Sample characteristics are reported in Table 2. CDRS-R scores ranged from mild (CDRS-R = 38) to severe (CDRS-R = 73), with a mean severity in the moderate range (CDRS-R = 55.6, SD = 10.5). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between adolescents randomized to a week 4 versus week 8 decision point.

FIGURE 2. CONSORT Diagram.

Note: IPT-A = interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Sample at Baseline

| Characteristics | Overall (N = 40) | Week 4 Decision Point (n = 20) | Week 8 Decision Point (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 14.8 (1.7) | 14.8 (1.8) | 14.8 (1.8) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 31 (77.5%) | 16 (80.0%) | 15 (75.0%) |

| Male | 9 (22.5%) | 4 (20.0%) | 5 (25.0%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 (10.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (10.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Asian | 3 (7.5%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (10.0%) |

| White | 32 (80.0%) | 16 (80.0%) | 16 (80.0%) |

| More than one race | 2 (5.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Clinical Characteristics Diagnosis | |||

| Major depressive disorder | 38 (95.0%) | 19 (95.0%) | 19 (95.0%) |

| Dysthymic disorder | 2 (5.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Depressive disorder NOS | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 9 (22.5%) | 3 (15.0%) | 6 (30.0%) |

| Social anxiety disorder | 9 (22.5%) | 6 (30.0%) | 3 (15.0%) |

| Panic disorder | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Specific phobia | 2 (5.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Anxiety disorder NOS | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 2 (5.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 3 (7.5%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (10.0%) |

| CDRS-R score, mean (SD) | 55.6 (10.5) | 55.9 (10.4) | 55.3 (11.0) |

| C-GAS score, mean (SD) | 51.0 (6.1) | 50.4 (5.2) | 51.6 (6.9) |

| SAS-SR score, mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.7) |

Note: CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised; C-GAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; NOS = not oterwise specified; SAS-SR = Social Adjustment Scale—Self-Report.

The attrition rate at the week 16 posttreatment assessment was 17.5%. Attrition did not differ by week 4 versus week 8 decision point (p = .68), whether the adolescents were sufficient or insufficient responders at week 4 or week 8 (p = .58), or by treatment augmentation strategy for adolescents who were insufficient responders (ie, increase IPT-A versus add fluoxetine) (p = .27).

There were no significant differences between sufficient responders and insufficient responders at week 4 based on baseline age, sex, number of depression episodes, duration of depression episode, number of comorbid diagnoses, or CDRS-R, CGAS, or SAS-SR scores. Week 8 insufficient responders had significantly higher baseline CDRS-R and SAS-SR scores than week 8 sufficient responders (CDRS-R: t17 = −2.58, p = .02; SAS-SR: t16 = −2.31, p = .04).

Posttreatment Outcomes by Decision Point

Table 3 gives the estimated mean posttreatment outcomes by decision point averaging over second-stage treatment decision. Using a week 4 decision point resulted in lower average posttreatment depressive symptoms as measured by the CDRS-R (Table 3) and higher functioning based on the CGAS, although the latter difference was not statistically significant. Decision point was not associated with posttreatment social functioning based on the SAS-SR. Of the 33 adolescents who completed the trial, 9 continued to meet diagnostic criteria for their original depression diagnosis: 3 were randomized to the week 4 decision point, and 6 were randomized to the week 8 decision point.

TABLE 3.

Estimated Posttreatment Outcomes by Decision Point

| Week 4 Decision Point | Week 8 Decision Point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | B | t | f2 |

| CDRS-R score | 34.94 (2.05) | 40.65 (2.05) | 5.72 | 1.97* | 0.08 |

| CGAS score | 66.52 (2.39) | 60.66 (2.39) | −5.85 | −1.71 † | 0.08 |

| SAS-SR score | 2.16 (.13) | 2.35 (.14) | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.03 |

Note: t in the column heading refers to value for the t test. CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised; C-GAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; SAS-SR = Social Adjustment Scale-Self-Report

SE = standard error.

p < .05

p < .10 (significance level is at a “trend” level).

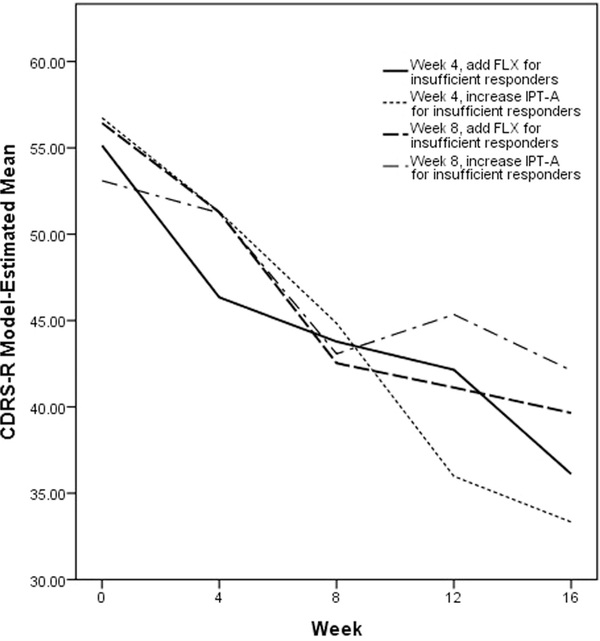

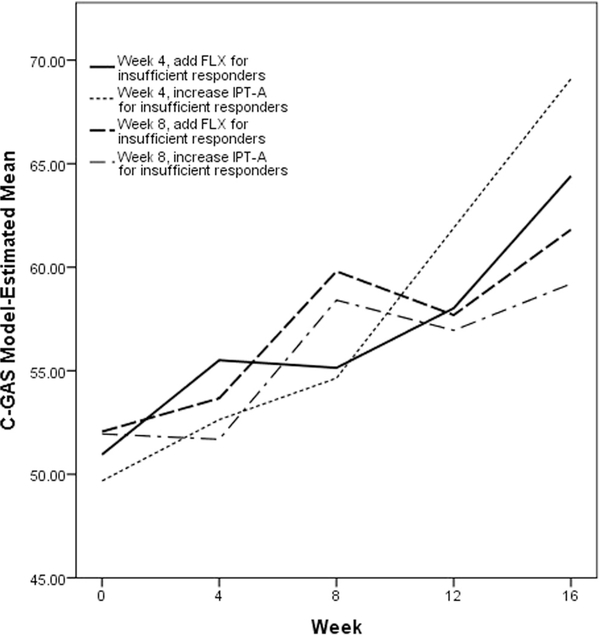

Exploratory Analyses: Posttreatment Outcomes by Algorithm

Table 4 reports the estimated mean posttreatment outcome if all adolescents in the population were to follow the four algorithms embedded in this trial design. Results are also illustrated in Figures 3 to 5. The algorithm in which adolescents were evaluated after 4 weeks of IPT-A and insufficient responders received increased frequency of IPT-A had more favorable outcomes across all three of the measures considered than the algorithm in which adolescents were evaluated after 8 weeks of IPT-A and insufficient responders received increased frequency of IPT-A (CDRS-R: B = 8.78, t = 2.96, p = .003, f 2 = 0.11; CGAS: B = −9.90, t = −2.86, p = .004, f 2 = 0.12; SAS-SR: B = 0.39, t = 1.78, p = .077, f 2 = 0.09). The algorithms in which insufficient responders received fluoxetine did not not differ based on whether adolescents were evaluated at week 4 versus week 8. The algorithm in which adolescents were evaluated after 4 weeks of IPT-A and insufficient responders received increased frequency of IPT-A also had more favorable outcomes across all 3 of the measures considered than the algorithm in which adolescents were evaluated after 8 weeks of IPT-A and insufficient responders received fluoxetine (CDRS-R: B = 6.32, t = 2.12, p = .034, f 2 = 0.11; CGAS: B = −7.28, t = −2.03, p = .043, f 2 = 0.12; SAS-SR: B = 0.38, t = 1.82, p = .070, f 2 = 0.09). The algorithm in which adolescents were evaluated after 4 weeks of IPT-A and insufficient responders received fluoxetine resulted in lower depression scores as measured by the CDRS-R than the algorithm in which adolescents were evaluated after 8 weeks of IPT-A and insufficient responders received increased frequency of IPT-A (B = 5.99, t = 2.09, p = .036, f 2 = 0.11).

TABLE 4.

Estimated Posttreatment Outcomes by Adaptive Treatment Strategy

| Week 4 | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR Add FLX | IR Increase IPT-A | IR Add FLX | IR Increase IPT-A | |

| Outcome | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) |

| CDRS-R score | 36.11 (1.97)a,b | 33.33 (2.09)a | 39.65 (2.14)b,c | 42.11 (2.09)c |

| CGAS score | 64.41 (2.27)a,b | 69.10 (2.48)a | 61.82 (2.49)b | 59.20 (2.35)b |

| SAS-SR score | 2.27 (0.12)a | 1.98 (0.14)a | 2.36 (0.16)a | 2.37 (0.16)a |

Note: Within each row, means that have a superscript letter in common are not significantly different from each other (p ≥ .05). CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised; C-GAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; FLX = fluoxetine; IPT-A = interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents; IR = insufficient responder; SAS-SR = Social Adjustment Scale—Self-Report; SE = standard error.

FIGURE 3. Model-Estimated Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R) Scores by Algorithm.

Note: FLX = fluoxetine; IPT-A = interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents.

FIGURE 5. Model-Estimated Social Adjustment Scale–Self-Report (SAS-SR) Scores by Algorithm.

Note: FLX = fluoxetine; IPT-A = interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents.

Harm and Suicide-Related Adverse Events

Harm and suicide-related adverse events are reported in Table 5. Four adolescents met the FDA’s definition of a serious adverse event. All four of these were suicide attempts. There were no deaths by suicide. No adolescents were hospitalized over the course of the trial.

TABLE 5.

Harm and Suicide-Related Adverse Events

| Emerged During Stage 1 |

Emerged During Stage 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Week 4 Decision |

Before Week 8 Decision |

Week 4 IR Add FLX |

Week 4 IR Increase IPT-A |

Week 8 IR Add FLX |

Week 8 IR Increase IPT-A |

|

| Outcome | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Harm-related | 3 (7.5%) | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (5.0%) | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (5.0%) |

| Suicide-related | 2 (5.0%) | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (5.0%) | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (2.5%) | 0 |

| Suicide attempt | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (5.0%) | 0 | 1 (2.5%) | 0 | 0 |

Note: FLX = fluoxetine; IPT-A = interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents; IR = insufficient responder.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that takes initial steps toward developing empirically based algorithms for guiding psychotherapy for adolescents with depression. We compared the efficacy of two time points during treatment with IPT-A for identifying and augmenting treatment for potential insufficient responders. Identifying decision points for adjustment to the treatment plan is needed for improving treatment efficacy and efficiency. Waiting too long to decide whether to change treatment for an insufficient responder could mean prolonged experience of depressive symptoms and associated functional impairments. On the other hand, augmenting treatment too soon might mean adding treatments that could increase the risk of side effects or other burdens before giving the initial treatment sufficient time to work. In the current study, we found that the earlier time point for assessing and identifying potential insufficient responders (week 4) was more efficacious in reducing adolescents’ depression symptoms than the later week 8 time point. Thus a “sooner rather than later” approach appears to be the best approach for catching potential insufficient responders to IPT-A. This is consistent with a study of antidepressant medication with adolescents, which also found that treatment response can be detected early in the course of treatment.47

We also explored the clinical and psychosocial outcomes of each of the four IPT-A algorithms embedded in the trial. For all outcomes, including depression, general functioning, and social functioning, the results indicated that if the algorithm augmented treatment for insufficient responders by increasing the dose of IPT-A, it was more efficacious to initiate this at week 4 than at week 8. Given the small sample size, these findings should be interpreted cautiously; however, they do provide some preliminary evidence that the timing of increasing the dose of psychotherapy may matter. It may be that adolescents who were asked to attend therapy twice weekly after 8 weeks of an insufficient response were less engaged and/or had a lower expectation of a treatment response than adolescents who were asked to attend therapy twice per week after just 4 weeks of an insufficient response. Previous research has shown a significant association between treatment expectancy and treatment outcome.48 It is also possible that the difference in timing has something to do with what is occurring in IPT-A at those two time points. At week 4, the adolescent is about to initiate working on the interpersonal problem area and learning new communication and interpersonal problem-solving skills. It may be that meeting twice per week at this time is particularly good timing, as it provides more concentrated skill building and opportunities for engaging in interpersonal experiments between sessions. In contrast, at week 8, the adolescent has already spent 4 weeks working on interpersonal skill building. If the adolescent is not responding sufficiently at that point, it may be that there are challenges with skill acquisition and/or problems with the receptivity of the individuals with whom the adolescent is trying build relationships. In this case, attempting to intensify the therapy may have diminishing returns.

This was the first clinical trial to implement IPT-A in conjunction with antidepressant medication. The results indicated that the algorithm that added fluoxetine at week 4 for insufficient responders was more efficacious than the algorithm that increased the dose of IPT-A at week 8. This is consistent with the overall pattern that augmenting treatment at week 8 with an increased dose of IPT-A is the least efficacious strategy. The algorithm that assessed depression symptoms at week 4 and augmented treatment for insufficient responders by increasing the frequency of IPT-A was more efficacious than the algorithm in which depression symptoms were assessed at week 8 and treatment was augmented by adding fluoxetine. For families who have concerns about antidepressant medication, increasing the frequency of IPT-A sessions represents an alternative treatment strategy, if it is initiated early in treatment. Increasing the frequency of sessions to twice per week is likely to be a challenging augmentation approach for families and therapists alike, given busy schedules. However, knowing that doing so for a time limited period of time (ie, 4 weeks) may increase the chances of a treatment response, and may help motivate families to find a way to make it work.

There were no significant differences in outcomes between the algorithms that augmented treatment with fluoxetine at week 4 versus at week 8. It may be that the timing of adding fluoxetine is not critical in the way that it appears to be for increasing the dose of IPT-A. Within each decision point, the algorithms that augmented treatment for insufficient responders by adding fluoxetine or increasing the dose of IPT-A were also comparable. It also may be that within a given time point (week 4 or week 8), adding fluoxetine or increasing the dose of IPT-A are comparable augmentation strategies. However, as this was a pilot study, the results should be considered preliminary because of the small sample size. It is possible that the algorithms that were not significantly different from one another in the current trial would be different in a larger, adequately powered study. A full-scale SMART is necessary to replicate these results and provide sufficient power to compare the efficacy of each of the algorithms. We are currently conducting a full-scale SMART to evaluate the relative effectiveness of the algorithms that include augmenting IPT-A with more frequent IPT-A sessions versus adding antidepressant medication (ie, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

The effect sizes of the differences in outcomes by timing of the decision point and by algorithm were in the small range, with some approaching the medium range. Statistical experts warn against overinterpreting pilot data for estimating effect sizes, as pilot study effect sizes are often inaccurate estimates of true effect sizes.49 However, should differences in the subsequent full- scale trial also be in the small range, this would not be entirely surprising, given that the interventions in this trial (IPT-A and fluoxetine) are both among the most effective interventions for adolescents with depression. Differences between them as augmentation strategies and differences in the timing of augmentation may not be large. Although there is hope and ongoing search for new interventions that might have a large effect, having clinical decision tools that can be used with currently available interventions, are easily implemented in practice, and can improve outcomes even incrementally is clinically meaningful. Furthermore, we would expect that the effect size of any of the adaptive interventions considered here would be larger compared to a nonadaptive strategy or treatment as usual. Such comparisons may be more meaningful, although we do not have data collected as part of this study to estimate those effect sizes.

In the current study, we piloted two treatment augmentation strategies: increasing the dose of IPT-A, and adding fluoxetine. Both of these treatment augmentation strategies implicitly assume that IPT-A was the appropriate first-choice psychotherapy for the adolescent. In addition, in the case of the algorithms that augment treatment with an increased dose of IPT-A, the assumption is that the insufficient response has occurred because the adolescent has not received enough IPT-A. However, given the heterogeneity in the underlying mechanisms of depression,50 it can be expected that some adolescents did not show a sufficient early response to treatment because IPT-A was not the appropriate first-line psychotherapy approach for them. For those adolescents, augmenting treatment by increasing the dose of IPT-A would be a particularly ineffective strategy if it is providing more of the “wrong” therapy. Future studies might investigate the effectiveness of switching the therapy approach for insufficient responders to IPT-A. Measures of depression mechanisms targeted by other psychotherapy approaches, such as cognitive distortions or level of engagement in pleasurable activities (both treatment targets of cognitive behavioral therapy), administered at week 4 and week 8 of IPT-A, might prove to be indicators of who should switch to an alternative therapy approach.

In addition to the small sample size, limitations of the current study include a primarily white upper-middle–class sample, conduct of the study in a research setting, and more stringent exclusion criteria typical of an efficacy study, all of which may limit the generalizability of the results. Our current full-scale trial is being conducted in a community mental health care setting with the goal of increasing the applicability of results to general clinical practice.

Despite the limitations of the current pilot study, the results have preliminary implications for clinical practice. Therapists should routinely monitor symptoms over the course of IPT-A and can consider augmenting treatment for insufficient responders as early as week 4 of treatment. Augmenting IPT-A by increasing the frequency of sessions to twice per week for a period of 4 weeks shows promise as a treatment augmentation strategy, as long as it is initiated early in treatment. Augmenting IPT-A with fluoxetine at week 4 for insufficient responders to IPT-A may be an efficacious strategy, as well. These results provide initial guidance for therapists in delivering personalized care that is adapted over time to meet the needs of each individual patient.

FIGURE 4. Model-Estimated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS) Scores by Algorithm.

Note: FLX = fluoxetine; IPT-A = interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by award number K23MH090216 from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health and award number UL1TR000114 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Center for Research Resources. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Minnesota.

Dr. Vock served as the statistical expert for this research.

The authors wish to thank Susan Murphy, PhD, of Harvard University, and Daniel Almirall, PhD, of the University of Michigan, for their assistance with this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Mufson has received royalties from Guilford Press, Inc. for the book, Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents. Drs. Gunlicks-Stoessel, Bernstein, Reigstad, Klimes-Dougan, Cullen, Murray, Vock, and Ms. Westervelt report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Meredith Gunlicks-Stoessel, University of Minnesota, MN.

Laura Mufson, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY.

Gail Bernstein, University of Minnesota, MN.

Ana Westervelt, University of Minnesota, MN.

Kristina Reigstad, University of Minnesota, MN.

Bonnie Klimes-Dougan, University of Minnesota, MN.

Kathryn Cullen, University of Minnesota, MN.

Aimee Murray, University of Minnesota, MN.

David Vock, University of Minnesota, MN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han V. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;138: e20161878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brent DA, Baugher M, Bridge J, Chen T, Chiappetta L. Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38: 1497–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glied S, Pine DS. Consequences and correlates of adolescent depression. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewinsohn PM, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Rohde P, Gotlib IH, Hops H. Adolescent psychopathology II: psychosocial risk factors for depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994; 103:302–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birmaher B, Brent D. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46: 1503–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mufson L, Dorta KP, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Olfson M, Weissman MM. A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.TADS Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive–behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Locher C, Koechlin H, Zion SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and placebo for common psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:1011–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, et al. What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: a multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. Am Psychol. 2017;72:79–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewandowski RE, Acri MC, Hoagwood KE, et al. Evidence for the management of adolescent depression. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e996–e1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crismon ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:142–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression in children and young people: identification and management. NICE guideline (CG28); 2005. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg28 Accessed December 11, 2018.

- 14.Mufson L, Dorta KP, Moreau D, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents 2 ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mufson L, Yanes-Lukin P, Anderson G. A pilot study of Brief IPT-A delivered in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37:481–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young JF, Benas JS, Schueler CM, Gallop R, Gillham JE, Mufson L. A randomized depression prevention trial comparing interpersonal psychotherapy–adolescent skills training to group counseling in schools. Prev Sci. 2016;17:314–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mufson L, Weissman MM, Moreau D, Garfinkel R. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy SA, Oslin DW, Rush AJ, Zhu J. Methodological challenges in constructing effective treatment sequences for chronic psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32: 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steidtmann D, Manber R, Blasey C, et al. Detecting critical decision points in psychotherapy and psychotherapy & medication for chronic depression. J Consult Clin Psychology. 2013;81:783–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunlicks-Stoessel ML, Mufson L. Early patterns of symptom change signal remission with interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28: 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton M Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with our without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression. JAMA. 2008;299:901–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke GN, Debar L, Lynch F, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of brief cognitive–behavioral therapy for depressed adolescents receiving antidepressant medication. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:888–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emslie G, Kowatch R, Costello L, Travis G, Peirce L. Double-blind study of fluoxetine in depressed children and adolescents. Proc Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995; 11:41–42. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emslie GJ, Heiligenstein JH, Wagner KD, et al. Fluoxetine for active treatment of depression in children and adolescents: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, Weinberg WA, Kowatch RA, Carmody T, Mayes TL. Fluoxetine in child and adolescent depression: acute and maintenance treatment. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7:32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke G, Rohde P, Lewinsohn P, Hops H, Seeley J. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of adolescent depression: efficacy of acute group treatment and booster sessions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:658–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Hops H, Andrews J. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of depressed adolescents. Behav Ther. 1990;21:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Mufson L, Westervelt A, Almirall D, Murphy S. A pilot SMART for developing an adaptive treatment strategy for adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45:480–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavori P, Dawson R. Dynamic treatment regimes: practical design considerations. Clinical Trials. 2003;1:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy SA. An experimental design for the development of adaptive treatment stratgies. Stat Med. 2005;24:1455–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaput F, Fisher P, Klein R, Greenhill L, Shaffer D. Columbia K-SADS (Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children) New York: Child Psychiatry Intervention Research Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. The Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poznanski EO, Miller E, Salguero C, Kelsh RC. Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the Children’s Depression Rating Scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1984;23:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Bird HR, Aluwahlia S. A children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissman MM, Bothwell S. Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1111–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C–CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1035–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scales. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;299:901–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy SA, Lynch KG, Oslin D, McKay JR, TenHave T. Developing adaptive treatment strategies in substance abuse research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88S:S24–S30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy SA, Oslin DW, Rush AJ, Zhu J. Methodological challenges in constructing effective treatment sequences for chronic psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nahum-Shani I, Qian M, Almirall D, et al. Experimental design and primary data analysis methods for comparing adaptive interventions. Psychol Methods. 2012;17: 457–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tao R, Emslie G, Mayes T, Nakonezny P, Kennard B, Hughes C. Early prediction of acute antidepressant treatment response and remission in pediatric major depressive disorder. J Ame Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curry J, Rohde P, Simons A, et al. Predictors and moderators of acute outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1427–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kraemer HC, Mintz J, Noda A, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006; 63:484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldberg D The heterogeneity of “major depression”. World Psychiatry. 2011;10: 226–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]