Abstract

Background:

Our aim was to identify health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) issues and symptoms in patients with haematological malignancies (HMs) and develop a conceptual framework to reflect the inter-relation between them.

Methods:

A total of 129 patients with HMs were interviewed in a UK multicentre qualitative study. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and analysed using NVivo-11.

Results:

Overall, 34 issues were reported by patients and were grouped into two parts: quality of life (QoL) and symptoms. The most prevalent HRQoL issues were: eating and drinking habits; social life; physical activity; sleep; and psychological well-being. Furthermore, most prevalent disease-related symptoms were: tiredness; feeling unwell; breathlessness; lack of energy; and back pain. The most prevalent treatment side effects were: tiredness; feeling sick; disturbance in sense of taste; and breathlessness.

Conclusions:

Both HMs and their treatments have a significant impact on patients’ HRQoL, in particular on issues such as job-role change, body image and impact on finances.

Keywords: clinical practice, clinical research, haematological malignancy, quality of life, symptoms

Introduction

Haematological malignancies (HMs) include neoplasms of myeloid and lymphoid cell lines1 with an expected UK incident rate of 38,740 per annum.2 The non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are the most prevalent HMs in the UK, followed by leukaemias and other lymphomas.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the primary objectives of cancer diagnosis and treatment as cure, prolongation of life and improvement of the quality of life (QoL).4 The maintenance of patients’ well-being is a fundamental goal of medical practice. Although treatments have the potential to cure or prolong life in some patients, the evidence suggests that health-related QoL (HRQoL) of patients with HM is significantly affected by the disease and its treatments.5–11 Until recently, it was assumed that measurement of an individual patient’s QoL as an endpoint was specific to clinical-trial scenarios evaluating efficacy of a single treatment. However, it is reported that the QoL information used during outpatient consultation may influence treatment decision making and result in changes in the current interventions or initiation of new ones. Thus, the assessment of QoL in routine clinical practice in patients with HMs is greatly needed and there is much demand from haematologists. This, alongside clinical care, could monitor response to treatment, focus on goals of care, identify unmet patients’ needs and facilitate patient–physician communication.12–14

Planning provision of patient care requires incorporating patients’ views and lived experience of disease and treatment. Given the rapid uptake and success of several treatments, HM is being transformed from a disease that one died from to a disease that one lives with. Hence, experiential patient evidence is a cornerstone of patient-centred care. Issues related to burden of the disease and treatment, information about the disease and the treatment, support factors, body image, insecurity, financial and insurance-related issues are generally overlooked,15 thus it is essential to further explore and identify the importance of these issues from HM patients’ perspectives.

Some recent systematic literature reviews highlighted how HM negatively affects patients’ overall HRQoL and reported psychological, social, professional, financial, sexual, cognitive and physical well-being as significant areas of such impact.15,16 Furthermore, the authors emphasised the importance of assessing HRQoL in the early course of care in order to adopt interventions which could improve physical and mental functioning.16 Another systematic review conducted describes how the burden of disease increases with the ageing population.17,18

A recent systematic literature review was published in 2019 with an aim to identify HRQoL issues important to patients with HMs, and the HRQoL instruments used both in routine clinical practice, as well as in clinical research.15 The review unfolds the evidence gap in the qualitative literature as well as the gap in the conceptual coverage among the identified instruments currently used in haematology. Among the 24 identified qualitative studies reviewed, only 3 reported sampling to redundancy (saturation), which is an important sampling criterion for qualitative studies. Moreover, the review reflected that current instruments do not cover important issues such as worrying/uncertainty about future, eating and drinking habits, being a burden to others, being judged by other people, travelling, going on holidays, difficulty with leaving the house, appearance/body image and sleeping patterns.15 This highlights the need for conducting a well-structured qualitative study using sampling-to-redundancy methodology to better understand the lived experience with different HMs from a patient’s perspective. The aims of the study were: (a) to explore the impact of a wide range of HMs and their treatment on patients’ HRQoL and symptoms, from their own perspective; and (b) to develop a conceptual framework based on the identified HRQoL issues and ‘signs and symptoms’.

Methods

Patient recruitment

The inclusion criteria were: ability to give informed written consent; being diagnosed with HM as per the most recent WHO classification;19 any state of the disease (stable, progressing or remission); any stage of the treatment (due to start the treatment, on treatment or finished treatment); and ability to read and write in English. A purposive sampling was chosen, including various types of HM, different states of the disease and treatment and geographical location, as such that the sample would be representative of the target population. Patients from 10 different HMs were recruited into the study including: acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), acute lymphoid leukaemia (ALL), chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), chronic lymphoid leukaemia (CLL), multiple myeloma (MM), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (INHL) and aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (ANHL). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patients were categorised as indolent or aggressive based on rate of progression and irrespective of cell type (B/T cell). For example, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma were grouped into ANHL, and follicular lymphoma and adult T-cell lymphoma were grouped into INHL. The MPN category included myelofibrosis, essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. The principal investigator from each participating centre or respective clinical nurses confirmed the type of diagnosis as listed above and categorised the patients as progressing, in remission or stable.

The stable, progressing, remission state of the disease was completely based on disease progression irrespective of whether a patient was on treatment. Therefore, patients could be on a treatment, awaiting treatment or off treatment. The primary focus was to be inclusive and the views of all types of patients to be considered and to understand the impact of the disease without limiting it to a particular stage or status of the treatment. Each study participant was assigned a unique identification number to allow collection of anonymised sociodemographic characteristics.

Patient research partner

A patient research partner (RE) diagnosed with CLL, was closely involved throughout the study as a member of the research team and carried out patient interviews. He will be referred to as ‘patient research partner’ throughout the paper.

Patient interview guide

A draft version of the ‘patient interview guide’ was prepared following discussion with the ‘patient research partner’ and was finalised after pilot testing with five patients (Table 1). Both interviewers had undergone qualitative interview research training at the University of Hertfordshire for carrying out patient interviews.

Table 1.

Suppinfo: patient interview guide.

| Themes | Guiding questions |

|---|---|

| Opening question | Can you tell me about any ways your life has been affected by your condition? |

| Main interview questions | Can you tell me how living with your condition makes you

feel? Can you tell me what things make you feel like this? Can you give examples? Do your activities change as a result of feeling like this? If so, how? How do you cope with feeling like this? Who do you talk to about feeling like this? Do you use any support services for example, websites/counselling to help you with your feelings? If so, what do you use and why? Does your condition affect your social life? Can you think of any social activities that you used to do which you can’t now as a result of your condition? What effect does your condition have on your day-to-day activities? /How does your disease affect your daily life? Has your disease had an impact on your working life? If so, how? Does your condition affect your housework? If so, how? What effect does your condition have on your friendships with others, both friends and strangers? Has your condition affected any relationships within your family? If so, how? Do you buy anything special or different as a result of your condition? Can you explain what and why? Do you experience any financial difficulties associated with your condition? What are the causes of these? Has your condition affected going on holiday at all? If so, how? Does your condition affect your sleep? If so, why? Has your condition affect your health in other ways? If so, how? Have you changed what you eat at all? If so, how? Do you have any support from people or groups? Can you tell me more? Do you feel fatigued or tired? Can you tell me more? How does this affect you? Has your sex life been affected at all? If so, how? Can you think of any other ways that your condition has affected your life? |

| Other questions | How do you feel you are coping with your

disease? Have you experienced any symptoms from your disease? If so, how have they affected your QoL? Have you experienced any side-effects from your treatment? If so, how have they affected your QoL? How do you feel in yourself? Do you worry about anything? If so, could you expand on this? (e.g. future concerns) Do you have any concerns regarding your medication/treatment? If so, what are they? . . . Could you elaborate? How do you manage your medication? Have you experienced any difficulty with your treatment/medication? Do you get support from friends and family? If so, how have they helped? What effect has this had on your QoL? Do you feel your needs as a patient are met adequately? Could you explain? Have you sought any other services outside of family, friends or the hospital? Have you experienced any distress as a result of your condition? How would you describe the emotions you feel living with your disease? |

| Closure | Is there anything else you can think of that you haven’t told me? |

QoL, quality of life.

Procedures

This study employed face-to-face interviews with open-ended questions related to HRQoL and symptoms. Patients with different types of HM were interviewed from six secondary care hospitals in England and Wales, United Kingdom, from both inpatient and outpatient settings. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Of all the transcriptions, 10% were randomly selected and validated by an independent interviewer (i.e. patient research partner) who was not involved in the transcription. This was done to confirm that all the transcripts fully reflected what had been reported by the patients. All the patients were encouraged to be honest, open and as detailed as possible. As there is no set sample size for such research, the criteria used in this study was ‘sampling to redundancy’ that is, interviewing people until a saturation point is reached and no new theme or sub-theme emerges.20 Since patients with 10 different HMs were recruited into the study, it was deemed prudent to aim for establishing saturation for each of the 10 HMs.

Data processing and analysis

The content analysis of all the transcribed interviews was performed using the NVivo 11 qualitative analysis software.21 The conventional content analysis approach was used to allow different HRQoL categories and the names of the categories to flow from the data rather than using any preconceived categories.22,23 The initial coded segments were clustered into categories that led to theme development following Saldana’s codes to theory model.24 The coding was carried out by PG and RE separately and was discussed to reach consensus. Any unresolved discrepancies were then further discussed with the third reviewer, the adjudicator (SS), to reach a decision. Furthermore, the final list of coded themes and sub-themes was then discussed among a panel of experts involving two haematologists, three patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) experts, a patient-advocacy group representative and a patient with HM. The relationship between the themes and sub-themes was based on the concurrence, antecedents or consequences that helped develop the conceptual model.25

Analysis of the transcriptions commenced after the first five interviews and was consistent with a constant comparison technique where new data was examined in the light of emerging themes. This technique helped to insure the ‘fit’ between the data and developing themes and added credibility to the findings. The coding followed the cross-analysis to identify issues and symptoms specific to disease type, disease state, age and sex.

Although, technically, the terms ‘signs’ and ‘symptoms’ are different, but the patients used them interchangeably. Therefore, all the findings were classified into two categories: HRQoL issues; and signs and symptoms. The classification of the themes and sub-themes into two categories was based on the underlying cause from the patients’ perspective. For example, if a patient reported difficulty moving around in the house due to tiredness, then tiredness, which is the proximal impact of the disease or the treatment, was classified into the ‘sign and symptom’ category, whereas the distal impact of tiredness, that is, difficulty moving around in the house, was categorised into HRQoL issues.

Results

Socio-demographics characteristics of the study participants

A total of 129 patients (male = 76–58.9%; mean age = 61.12 years; median age = 65 years; age range = 18–88 years) with median time since diagnosis of 2 years (range = 19 days to 23 years) were recruited into the study (Table 2). There was a difference in median age between different HMs, as expected; MM, CLL, MDS and MPN were diagnosed mostly in older patients, whereas HL and CML were diagnosed in a younger patient population. In addition, AML, CLL, CML and ALL were more prevalent in males compared with females. A total of 50 (38.6%) patients had other comorbidities [the most prevalent were arthritis (7), asthma (4), hypertension (6), diabetes (4)], of whom 5 had other types of cancers [prostate cancer (3), lung cancer (1), skin cancer (1)]. The median duration of the interviews was 26 min (range = 11–54 min).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants (n = 129).

| Characteristic | Category | Mean (±SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.1 (±15.4) | 18–88 | |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 3.7 (±4.3) | 0.05–23 | |

| n | % | ||

| Sex | Male | 76 | 58.9 |

| Female | 53 | 41.1 | |

| Employment status | Employed full time | 31 | 24.0 |

| Unemployed | 6 | 4.7 | |

| Self-employed | 8 | 6.2 | |

| Homemaker | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Retired | 71 | 55.0 | |

| Other | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 3.9 | |

| Student | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Ethnic origin | White | 122 | 94.6 |

| Asian or Asian British | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Black or Black British | 6 | 4.7 | |

| Disease sub-type | AML | 18 | 14.0 |

| ALL | 7 | 5.4 | |

| CLL | 11 | 8.5 | |

| MM | 21 | 16.3 | |

| ANHL | 17 | 13.2 | |

| INHL | 14 | 10.9 | |

| CML | 12 | 9.3 | |

| MPN | 10 | 7.8 | |

| MDS | 8 | 6.2 | |

| HL | 11 | 8.5 | |

| Disease state | Stable | 34 | 26.4 |

| Progression | 49 | 38.0 | |

| Remission | 46 | 35.7 | |

| Comorbidities | Comorbidities, cases | 45 | 34.8 |

| Other Cancer, cases | 5 | 3.8 |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, AML, acute myeloid leukaemia ANHL, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphoid leukaemia; CML, chronic lymphoid leukaemia; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; INHL, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; SD, standard deviation.

Saturation point

After every five interviews, transcriptions were analysed to check for saturation point. The new themes and sub-themes were emerging until the 120th patient was recruited into the study. To confirm the saturation, we continued interviewing seven patients from the same hospital sites, followed by two new patients from a different geographical location, separated by a period of 2 months. The additional nine interviews did not generate any new theme(s) for any of the 10 HMs and therefore saturation was confirmed.

Health-related quality-of-life themes generated by patients with HM

Following the content analysis of all transcribed interviews, the issues were coded into themes and sub-themes. This resulted in a list of overall 34 categories of issues identified to be important from the patients’ perspective. After reaching consensus among the panel, these issues were then grouped under two parts: HRQoL issues (impact); and symptoms (Table 3).

Table 3.

Health-related quality-of-life themes and symptoms reported by patients with haematological malignancies.

| Categories | Prevalence | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | Quality-of-life issues (n = 129) | ||

| Eating and drinking habits | 117 | 90.7 | |

| Social life or participatory function | 86 | 66.7 | |

| Physical ability or independency | 70 | 54.3 | |

| Sleep | 66 | 51.2 | |

| Psychological well-being | 64 | 49.6 | |

| Daily activities | 62 | 48.1 | |

| Holidays and travelling | 60 | 46.5 | |

| Sexual life | 55 | 42.6 | |

| Work Life | 55 | 42.6 | |

| Feeling distressed | 43 | 33.3 | |

| Ability to manage finances | 36 | 27.9 | |

| Support from family, relatives and friends | 35 | 27.1 | |

| Information about disease or treatment | 35 | 27.1 | |

| Recreational activities and pastime | 31 | 24.0 | |

| Delay diagnosis | 31 | 24.0 | |

| Attitude towards disease | 29 | 22.5 | |

| Current and future concerns | 27 | 20.9 | |

| Relationships | 26 | 20.2 | |

| Duration of the treatment | 21 | 16.3 | |

| Healthcare services | 19 | 14.7 | |

| Commuting to the hospital | 17 | 13.2 | |

| Bone marrow test | 16 | 12.4 | |

| Time spent in hospital | 14 | 10.9 | |

| Medication management | 12 | 9.3 | |

| Support services | 12 | 9.3 | |

| Blood transfusions | 12 | 9.3 | |

| Worried about hospital visits | 11 | 8.5 | |

| Biopsy | 9 | 7.0 | |

| Body image | 7 | 5.4 | |

| Buying behaviour | 5 | 3.9 | |

| Treatment affected more than the disease | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Studies | 2 | 1.6 | |

| (b) | Symptoms (n = 129) | Number of symptoms/side effects reported | |

| Disease-related symptoms | 102 | ||

| Treatment side effects | 121 | ||

A sample of the 34 categories of issues identified will be described fully here in two parts: part I, QoL issues; and part II, symptoms. A more detailed version of the manuscript will be available from the authors on request.

Part I: quality-of-life issues

Eating and drinking habits

Concerns related to eating and drinking habits were raised by 117 patients of whom 30% were in the age group of 65–75 years and 45% between age group 35–65 and were more prevalent in males (61%). Forty-two (36%) of these patients were in the early course of their disease (less than a year). A total of 58 patients changed their eating and drinking habits after being diagnosed or as a result of treatment [Table 4: 1(a, b)] and 48 patients reported a decrease in their appetite during or after treatment [Table 4: 1(c)]. Conversely, 13 patients reported an increase in appetite, which was mainly associated with steroids prescribed during treatment [Table 4: 1(d)], 29 patients reported they had stopped drinking alcohol since their diagnosis and 28 reported reduced alcohol intake, whereas 2 patients reported an increase in alcohol consumption as a reaction to their diagnosis [Table 4: 1(e)].

Table 4.

Patient quotes.

| Comment number | Age in years (sex) |

Diagnosis | Patient comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating and drinking habits | |||

| 1(a) | 37 (female) | CML | ‘I have started this organic food, more healthy. I think people hate me all of sudden, I just moan about everything, sugar and things like that.’ |

| 1(b) | 58 (male) | FL | ‘So, in my opinion you have to try something else before it comes back, I have to try alternatives, supplements, new theories, eat more healthy, sugar is killer, more green and any kind of thing to not to encourage cancer in your body.’ |

| 1(c) | 29 (male) | NHL | ‘All the side effects were just disgusting, if you’re feeling sick or if you have a headache, you are not susceptible to have food’ |

| 1(d) | 40 (male) | MM | ‘Over the 5 months I gained weight because of the steroids, they increase your appetite, I found myself sitting at home and eating. Also, I could not do exercise.’ |

| 1(e) | 67 (male) | MM | ‘I am really trying to find an answer to that myself. It might have been because of stress, I can’t honestly put my finger on why I just thought of drinking more.’ |

| Social life and participatory function | |||

| 2(a) | 49 (male) | ALL | ‘No social life at all because my neutrophils are low, I am neutropenic and I cannot go outside. If I go, I wear the mask and if I go with the mask then people look at me and think I am stupid, they think I have some virus, so they avoid me.’ |

| 2(b) | 51 (female) | AML | ‘I didn’t have a social life really because I was so ill, like I said even to wash and to have a bath was difficult, I kind of lost all my muscle strength.’ |

| 2(c) | 44 (female) | HL | ‘If I was going somewhere where there was crowd, I used to have a panic attack and I couldn’t breathe properly. I just was too scared to get myself into that state because it was going to be crowded and it was family, not strangers.’ |

| Physical well-being and independence | |||

| 3(a) | 79 (female) | MM | ‘I could not walk at all, so they put a special toilet for me, which was the best thing and then I had a physiotherapist coming. But of course if you lay on your bed for more than 2 months then everything goes, your muscles don’t work properly.’ |

| 3(b) | 47 (female) | ALL | ‘I think my partner probably felt different about me. Because I have always been so independent and did everything on my own, we never talked about this but I think he felt I was very fragile and I can’t handle it.’ |

| 3(c) | 50 (female) | ALL | ‘I have weakness, extreme tiredness, loss of appetite, just not going out to do things, just going from able body to disabled within few weeks, not able to go upstairs at home and feeling unwell generally.’ |

| Psychological well-being and attitude towards treatment | |||

| 4(a) | 52 (female) | MM | ‘At one stage I was really suicidal about the condition. When you are in that position, especially during the first week, I was really feeling unsafe. It was a very tough time. I’m still very traumatised by the whole thing during the diagnosis.’ |

| Daily activities/chores and home management | |||

| 5(a) | 53 (female) | ALL | ‘I would say each day is a real effort to get through and to be at home, cook and do stuff yourself is extremely difficult. So, everything is an effort, to do it you really have to push yourself.’ |

| 5(b) | 56 (female) | INHL | ‘Well, generally my sister comes over which is a pain because I can’t do anything. She does everything for me. The nurses here care for me, they come in to change my things.’ |

| 5(c) | 79 (female) | MM | ‘I have not got any energy to do anything. I stopped, I use to go for shopping to Tesco because I could hold on to trolley, but I cannot do anything now’. |

| Sexual life | |||

| 6(a) | 37 (female) | CML | ‘How would I explain to someone that I don’t really feel like having sex because I have been compromised and I don’t feel confident, I have no idea how I can say I can’t have kids.’ |

| Work life, study and ability to manage finances | |||

| 7(a) | 63 (male) | AML | ‘I used to be a production manager and obviously being off for 12 months or even less, it wasn’t an option to try and continue. So, someone else has got my job now. So, I’m no longer a production manager. They give me another title, so I’m still employed, but I have never actually taken that role until now, it is an office space job.’ |

| 7(b) | 31 (male) | ALL | ‘I ended up in the hospital, I had my business, my wife is not working, I was the only source of income, so money is not coming in, everything started to crumble, and everything started to go around suddenly.’ |

| 7(c) | 36 (female) | CML | ‘I ended up in debt. At one point when I was going through treatment, I was haunted by banks but that was fine. Obviously coming from a decent-paying job to relying on state hand out was really tough. I also had to wait for the handouts to come.’ |

| 7(d) | 38 (male) | ALL | ‘The condition has affected me big time. When I will leave the hospital now what I am going to do, I cannot go to work straight away, we supposed to be moving, if we move then we do need funding to buy stuff and putting things at place. So, I don’t know what I am going to do, I cannot go straight to work. There is no one that would say that now you are in the hospital here is the funding, you know what I mean, could say that we will pay for the first 6 months but there is nothing, I am sick, I am here but I still have to make sure that everything is alright at the shop, arrange everything, one of my fridges is not working so I have been googling to try and find someone who can fix it or replace it.’ |

| 7(e) | 24 (female) | ALL | ‘I had to stop looking after the children when I was in the hospital, so he did not have any of his money coming in, we could not pay any rent or bills but I had then social insurance people and she sorted out things for us. Now it is affecting me financially because now I cannot go back to work, my maternity leave is finished and I have no pay at all at the moment and with things like when I am feeling ill or when I have bone marrow then my partner has to come home and then we are not getting any money.’ |

ALL, acute lymphoid leukaemia; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; CLL, chronic lymphoid leukaemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; FL, follicular lymphoma; INHL, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MM, multiple myeloma; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Social life and participatory function

A total of 86 patients (66%) with different HMs reported issues relating to their social life and participatory functions. Twenty-eight (32.6%) of these patients were diagnosed less than a year ago and 35 (40.7%) were still in the ‘active’ disease state. Only 20% of the patients diagnosed 5 years ago reported impact on social life and participatory function. Most of the patients were known to have a clinically exploitable immune system because of the disease and treatments and 21 patients were housebound due to severe neutropenia. The patients discussed difficulty with being isolated and they could not go out in ‘crowds’ because they were susceptible to infections [Table 4: 2(a)]. For other patients, the issue was mainly a physical inability, as they did not have enough strength to move [Table 4: 2(b)]. Further concerns were related to ‘eating or drinking out’; for many patients, their social life involved going to the restaurants for meals or going to the pub [Table 4: 2(c)].

Physical well-being and independence

A total of 70 patients (54%) reported limitations in physical activity. This was experienced in the early course of the disease and was raised by 38 (54.3%) patients who were retired, with the highest being among the 65–75 years’ age group. Tiredness, lack of energy and low muscular strength were the main reasons for limited physical activities [Table 4: 3(a)]. Eight patients were having difficulty in going up or down the stairs and five patients reported difficulty in walking up or down the hill. Immobility made them dependent on their caregiver for even basic daily activities [Table 4: 3(b, c)].

Psychological well-being and attitude towards treatment

Maintaining a sense of psychological well-being and being positive towards life is very difficult for HM patients. Sixty-four (50%) patients reported concerns relating to their psychological well-being. The patients expressed how traumatic and emotional their diagnosis has been. Fourteen patients expressed disappointment and frustration about the diagnosis and the treatment. One patient expressed suicidal thoughts because of the condition [Table 4: 4(a)]. Forty-three (33%) patients mentioned that they were distressed during and after the treatment. Similarly, 27 (21%) discussed their worries about treatment, their families and about their physical appearance.

When asked about any concerns, 27 patients expressed their worries. Most of these patients were worried about their future health, work, studies, family and finances. Three patients expressed uncertainty about the future being really disappointing. Seven patients who were in remission mentioned that they were always thinking and worried about relapse.

Daily activities/chores and home management

A total of 62 patients (48%) experienced negative impacts on their daily activities, 25 (40.3%) of whom were diagnosed less than a year ago. Seventeen patients (13%) mentioned that they had stopped or did less cooking because of lack of energy and tiredness. Fifteen patients (12%) were not able to do any work, 13 of whom were still on treatment at the time of the interview [Table 4: 5(a)]. Furthermore, 4 patients reported difficulty in taking a shower and 3 had problems with dressing up [Table 4: 5(b)]. Nine patients discussed the difficulty in going for their regular shopping [Table 4: 5(c)].

Sexual life

Sexual feelings and attitude may change for a person at different points in life; in particular, for those with a chronic life-threatening disease. To this end, 55 patients (43%) reported concerns regarding their sexual life. Male patients (69%) were affected more than females (30.9%). A total of 14 (26%) of these were diagnosed 2–4 years ago and 22 (40%) were on remission. Most of their concerns were particularly during the early course of their disease and treatment [Table 4: 6(a)]. The main reasons for impaired sexual life were tiredness, lack of energy, lack of confidence, skin bruises, scars, disappointment and frustration because of the disease and treatment. Seven patients expressed concerns about their body image.

Work life, study and the ability to manage finances

Fatigue had significant effect on workers, affecting their physical functioning/work performance and ability to concentrate. A total of 55 patients (42%) reported a negative impact on their work life, of whom 10 had to take early retirement. In addition, three patients had given up their jobs, two were dismissed and three made redundant. Seven patients experienced a change in their job-role function, as they could not cope with the demands of their previous role or because their job was given to someone else [Table 4: 7(a)]. Three patients had to close their business, as they were spending most of their time in the hospital or recovering in bed at home [Table 4: 7(b)]. The main reasons for the impact on work life as reported by the patients were tiredness, amount of time spent in hospital for diagnostic procedure and treatments, and inability to concentrate. Two students could not continue their studies and had to take a break because of the treatment.

A total of 36 patients reported difficulty in managing their finances, of whom 31% were in the 25–45 age group and, interestingly, 42% in remission [Table 4: 7(c–e)]. Furthermore, there was also no or limited support for the self-employed who were greatly affected financially, as they did not have any employer providing paid sick leave.

Part II: disease-related symptoms and treatment side effects

When asked what kind of symptoms they experienced at the time of diagnosis, before they started treatment, 102 different symptoms were reported (Table 5). With respect to disease-specific symptoms: 15 patients, all with lymphoma, reported ‘night sweats’; 18 patients experienced ‘back pain’, of whom those with MM were affected the most; 21 patients suffered from ‘lack of energy’, of whom the AML patients were affected the most (5); 16 reported ‘weight loss’ with the highest in CML patients (4); 7 patients experienced ‘bone ache’ of whom the MM patients (5) were highly affected; and 9 were affected by ‘lump on the neck’, with the highest among those with HL (5). In contrast, 13 patients reported ‘no symptoms’, out of which 4 (30.8%) were CLL, 3 (23.1%) CML and 3 (23.1%) MPN patients. Eight (88.9%) of nine cases of ‘chest pain’ were reported by males.

Table 5.

Disease-related symptoms and treatment side effects reported by patients with haematological malignancies.

| Disease-related symptoms | Prevalence (n = 129) | % | Treatment side effects | Prevalence (n = 129) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiredness | 66 | 51.2 | Tiredness | 74 | 57.4 |

| Not feeling well | 28 | 21.7 | Feeling sick | 36 | 27.9 |

| Breathlessness | 24 | 18.6 | Lack of energy | 20 | 15.5 |

| Lack of energy | 21 | 16.3 | Taste disturbance | 20 | 15.5 |

| Back pain | 18 | 14.0 | Nausea | 17 | 13.2 |

| Weight loss | 16 | 12.4 | Breathlessness | 16 | 12.4 |

| Body ache | 15 | 11.6 | Diarrhoea | 16 | 12.4 |

| Night Sweats | 15 | 11.6 | Hair Loss | 15 | 11.6 |

| No symptoms | 13 | 10.1 | Bowel problems | 13 | 10.1 |

| Coughing | 10 | 7.8 | Body ache | 12 | 9.3 |

| Chest pain | 9 | 7.0 | Raised body temperature |

12 |

9.3 |

| Feeling lethargic | 9 | 7.0 | Weight gain | 11 | 8.5 |

| Lump on the neck | 9 | 7.0 | Chest pain | 10 | 7.8 |

| Abdominal pain | 8 | 6.2 | Headache | 9 | 7.0 |

| Itching | 8 | 6.2 | Loss of appetite | 9 | 7.0 |

| Bone ache | 7 | 5.4 | Weight loss | 9 | 7.0 |

| Cold | 7 | 5.4 | Constipation | 8 | 6.2 |

| Difficulty in walking | 7 | 5.4 | Fatigue |

7 |

5.4 |

| Lumps on skin | 7 | 5.4 | Vomiting | 7 | 5.4 |

A total of 121 side effects were reported when patients were asked if they had experienced any side effects with their treatment (Table 5). Breathlessness was observed the highest in the CML patients (4 of 16), and 5 of the 16 cases were among the 65–75 age group. Four of the eight reported constipation cases were patients with ANHL. Hair loss was highly reported by the ANHL patients (7 of 15 cases). Male patients were highly affected by body ache (10 of 12), diarrhoea (11 of 16), headache (8 of 9) and nausea (10 of 16).

Conceptual model

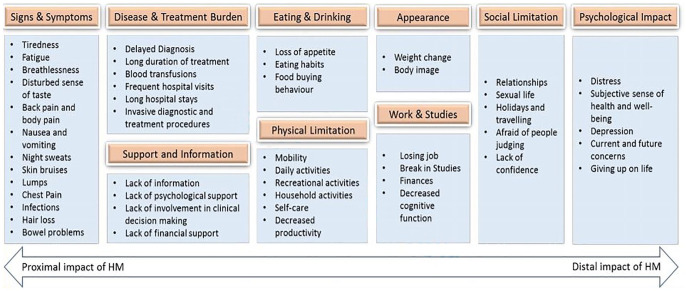

A revised conceptual model, which superseded the initial hypothesised conceptual model, was developed to help to understand the relationship between the themes and how they have been classified in this research (Figure 1). The model shows relevant concepts, organised by type, with the proximal impact (i.e. areas directly impacted by the disease or the treatment) on the left and the distal impact (i.e. indirect and long-term effect of the disease and the treatment) on the right. All the signs and symptoms reported by more than five patients and the impact of the diagnostic and treatment procedures were found to be more proximal. Further, impact on social limitation and physiological well-being was found to be a more distal impact of the disease.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for impact on HRQoL for patients with HMs.

HMs, haematological malignancies; HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this research was to better understand the experiences of adult patients living with haematological malignancy. This study goes beyond the general qualitative research methodology by recruiting 129 patients using purposive sampling techniques to reach saturation point for each of the 10 HMs in order to improve their generalisability across individual HMs. The HRQoL issues and signs and symptoms reported in the other studies are among those identified through this qualitative research.5–11,15 However, this study goes beyond the common themes reported by previous qualitative research and has identified HRQoL issues such as ‘eating and drinking, sleep, delayed diagnosis, duration of treatment, medication management, blood transfusions’, and sign and symptoms such as ‘lumps, abdominal pain, itching, taste disturbance, and loss of appetite’ which were reported by HM patients in this study with high prevalence and significantly affecting patients’ lives. Furthermore, this study has also identified that only 10% of patients did not experience any symptoms at all prior to their diagnosis or remission. The comprehensive qualitative analysis including identification of the proximal and distal determinants impacting HRQoL carried out in this study clearly reflect the intricate picture of the patients’ lives and all the areas that are greatly affected by the disease and its treatments.

The key symptoms, as well as treatment side effects, reported by all the patients, were tiredness and fatigue, which support the findings of previous studies.26,27 In addition, this study has identified that patients with HM suffer from a great deal of anxiety and depression5,28 and has clarified the main reasons behind this emotional behaviour; that is, the unmet need of these patients with respect to psychological support. Interestingly, not a single patient mentioned that he/she was offered any psychosocial screening and/or rehabilitation. Further, we also found a communication gap between the patients, consultants and hospital staff which created a delay in diagnosis/treatment which, in turn, prevented them being able to express their feelings. Moreover, the waiting time for the appointments, blood test or scan results contributed to anxiety and impaired psychological well-being. Diagnostic procedures, such as bone marrow test and biopsy, and treatment procedures, like blood transfusion, were identified as the main burden of disease.

The findings clearly indicate how the disease and side effects of treatments affect relationships. Many patients during the interviews expressed that they were not comfortable talking about issues related to their personal and sexual life to the consultant and/or other hospital staff. The impaired psychological and physical well-being and duration of treatments were the main reasons for the negative impact on work life, which have also been reported in previous studies.29,30

Conclusion

The evidence generated by this study clearly suggests that HRQoL of patients with HM is significantly affected by the disease and its treatments and the relationship between the different HRQoL issues is more complex than it appears.

The conceptual framework developed may help the clinicians and clinical practice staff to successfully implement the knowledge translation interventions in their practice. Such a framework can assist uptaking the evidence on patients’ HRQoL, identify its proximal and distal impact and discuss with the patients a tailored intervention on an individual basis. This framework would also act as a bridge between research and practice.

Study limitations

Although some of our findings support previously published studies, it should be noted that the study is qualitative in nature and not a hypothesis-testing one. Thus, it did not lend itself to statistical analysis. The heterogeneity in the sample might be considered as another limitation of the study, but the saturation point for both ‘HRQoL issues’ and ‘signs and symptoms’ across different HMs was achieved and is consistent with the research question. However, no such study has been performed previously and therefore, it is unique in the sense of involving patients with all kinds of HMs. Furthermore, the study recruited patients from secondary care hospitals in the UK and therefore has a form of geographical limitation and may not be representative of the HM population outside the UK.

Clinical implications

There are no clinical implications of this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the input of all the study participants and participating centres for their support throughout the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Consent for publication: All the authors gave their consent for publication of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Multicentre ethics approval was obtained from the NRES South West Bristol, UK (ref 14/SW/0033) followed by individual research-and-development approvals from all the participating centres. Signed informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data availability statement: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding: The author(s) disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the European Haematology Association Scientific Working Group ‘Quality of life and symptoms’ through unrestricted grants from Novartis, Bristol Myers Squib and Sanofi.

ORCID iD: Goswami Pushpendra  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3171-2495

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3171-2495

Contributor Information

Pushpendra Goswami, School of Life and Medical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK.

Esther N. Oliva, Haematology Unit, Grande Ospedale Metropolitano, Reggio Calabria, Italy

Tatyana Ionova, St Petersburg State University Medical Center and Multinational Centre for Quality of Life Research, St Petersburg, Russia.

Roger Else, Patient Research Partner, Milton Keynes, UK.

Jonathan Kell, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, Cardiff, UK.

Adele K. Fielding, University College London Cancer Institute, London, UK

Daniel M. Jennings, Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Guildford, Surrey, UK

Marina Karakantza, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK.

Saad Al-Ismail, Singleton Hospital, ABM University Health Board, Swansea, UK.

Graham P. Collins, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust, Oxford, UK

Stewart McConnell, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK.

Catherine Langton, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK.

Sam Salek, School of Life and Medical Science, University of Hertfordshire, Health Research Building (2F412), College Lane, Hatfield, Herts AL10 9BR, UK.

References

- 1. HMRN. Classification, https://www.hmrn.org/about/classification (2004, 23 February 2017).

- 2. HMRN. Incidence and survival, https://www.hmrn.org/statistics/quick (2014, 23 February 2017).

- 3. CancerResearch. Cancer incidence for common cancers, http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/incidence/common-cancers-compared#heading-Zero (2015, 23 February 2017).

- 4. World Health Organisation. Cancer: diagnosis and treatment, http://www.who.int/cancer/treatment/en/ (2017, 25 February 2017).

- 5. Johnsen AT, Tholstrup D, Petersen MA, et al. Health related quality of life in a nationally representative sample of haematological patients. Eur J Haematol 2009; 83: 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strasser-Weippl K, Ludwig H. Psychosocial QOL is an independent predictor of overall survival in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol 2008; 81: 374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holzner B, Kemmler G, Kopp M, et al. Quality of life of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of a longitudinal investigation over 1 yr. Eur J Haematol 2004; 72: 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mols F, Aaronson NK, Vingerhoets AJ, et al. Quality of life among long-term non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors: a population-based study. Cancer 2007; 109: 1659–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Persson L, Larsson G, Ohlsson O, et al. Acute leukaemia or highly malignant lymphoma patients’ quality of life over two years: a pilot study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001; 10: 36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Santos FR, Kozasa EH, Chauffaille Mde L, et al. Psychosocial adaptation and quality of life among Brazilian patients with different hematological malignancies. J Psychosom Res 2006; 60: 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shanafelt TD, Bowen D, Venkat C, et al. Quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an international survey of 1482 patients. Br J Haematol 2007; 139: 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenhalgh J. The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why? Qual Life Res 2009; 18: 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ 2001; 322: 1297–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 714–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goswami P, Khatib Y, Salek S. Haematological malignancy: are we measuring what is important to patients? A systematic review of quality-of-life instruments. Eur J Haematol 2019; 102: 279–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Allart-Vorelli P, Porro B, Baguet F, et al. Haematological cancer and quality of life: a systematic literature review. Blood Cancer J 2015; 5: e305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Osborne TR, Ramsenthaler C, Siegert RJ, et al. What issues matter most to people with multiple myeloma and how well are we measuring them? A systematic review of quality of life tools. Eur J Haematol 2012; 89: 437–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. York. DoHSTUO. Haematological malignancy research network incidence & survival, https://www.hmrn.org/statistics/quick (2017, 27 February 2017).

- 19. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Publications, 2017, p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Heatlh measurement scales a practical guide to their development and use. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, pp. 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Beyond constant comparison qualitative data analysis: using NVivo. Sch Psychol Q 2011; 26: 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kondracki NL, Wellman NS, Amundson DR. Content analysis: review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J Nutr Educ Behav 2002; 34: 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Washington, DC: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2016, pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995, p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Courneya KS, Sellar CM, Stevinson C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 4605–4612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Else M, Smith AG, Cocks K, et al. Patients’ experience of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: baseline health-related quality of life results from the LRF CLL4 trial. Br J Haematol 2008; 143: 690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Molassiotis A, Wilson B, Blair S, et al. Unmet supportive care needs, psychological well-being and quality of life in patients living with multiple myeloma and their partners. Psychooncology 2011; 20: 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Flechtner H, Ruffer JU, Henry-Amar M, et al. Quality of life assessment in Hodgkin’s disease: a new comprehensive approach. First experiences from the EORTC/GELA and GHSG trials. EORTC lymphoma cooperative group. Groupe D’Etude des Lymphomes de L’Adulte and German Hodgkin study group. Ann Oncol 1998; 9(Suppl. 5): S147–S154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, et al. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: effects on quality of life. Cancer 2008; 112: 616–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]