Health interventions address many types of stigma among sexual and gender minorities, however, intervention must expand to address diverse populations’ needs beyond HIV-related outcomes among sexual minority men.

Keywords: Gender minorities, Intersectionality, Intervention, Stigma, Sexual minorities

Abstract

Stigma against sexual and gender minorities is a major driver of health disparities. Psychological and behavioral interventions that do not address the stigma experienced by sexual and gender minorities may be less efficacious. We conducted a systematic review of existing psychological and behavioral health interventions for sexual and gender minorities to investigate how interventions target sexual and gender minority stigma and consider how stigma could affect intervention efficacy. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed. Eligible studies were peer reviewed and published in English between January 2003 and July 2019 and reported empirical results of behavioral or psychological interventions implemented among sexual and gender minorities. All interventions addressed stigma. We identified 37 eligible interventions. Most interventions targeted sexual minority men. Interventions were frequently developed or adapted for implementation among sexual and gender minorities and addressed multiple levels and types of stigma. Interventions most frequently targeted proximal stressors, including internalized and anticipated stigma. HIV and mental health were the most commonly targeted health outcomes. A limited number of studies investigated the moderating or mediating effects of stigma on intervention efficacy. The application of an intersectional framework was frequently absent and rarely amounted to addressing sources of stigma beyond sexual and gender minority identities. A growing number of interventions address sexual and gender minority stigma in an effort to prevent deleterious health effects. Future research is needed to assess whether stigma modifies the effectiveness of existing psychological and behavioral interventions among sexual and gender minorities. Further, the application of intersectional frameworks is needed to more comprehensively intervene on multiple, intersecting sources of stigma faced by the diverse sexual and gender minority community.

IMPLICATIONS.

Practice: Behavioral and psychological health interventions for sexual and gender minorities should account for experiences of stigma when they are designed and adapted.

Policy: Policy makers seeking to reduce psychological and behavioral health disparities among sexual and gender minorities should support sexual and gender minority-specific, evidence-based preventative interventions that intervene on stigma.

Research: Future intervention research with sexual and gender minority populations should investigate the impact of stigma on intervention effectiveness and examine the impact of multiple, intersecting sources of stigma.

Health disparities experienced by sexual and gender minorities (SGMs; i.e., individuals who do not identify as heterosexual or cisgender) are widely recorded in scientific literature [1–3]. Even with advances in social policy for SGM equality and protection, SGMs are more likely to experience psychological disorders [4], physical illness [5], and barriers to comprehensive, affirming health care [6] compared to heterosexual or cisgender populations. Minority stress theory posits that SGMs experience unique and chronic, stigma-related stress contributing to elevated risk for poor health and reduced access to coping resources [7, 8]. Thus, it is critical that interventions seeking to alleviate psychological distress and improve health among SGMs take into account the role stigma plays in SGM health.

Although a recent review summarized evidence-based interventions targeting stigma against sexual minorities [9], less is known about how the stigma experienced by SGMs is addressed. Thus, researchers are limited in their ability to improve on prior interventions systematically because the field has not yet summarized how existing interventions address SGM stigma. Further, attention should be paid to how stigma is operationalized in intervention research. The stigma that SGMs face occurs along a continuum of proximity to the individual from distal stressors (e.g., events of discrimination or violence and lack of legal protection) to more proximal stressors (e.g., expectations of rejection or internalized stigma). In addition, minority stress theory emerged from research mainly focused on a single aspect of an individual’s identity (i.e., sexual orientation or gender identity) rather than addressing the intersection of multiple, stigmatized social identities and the interlocking of identities with social privilege and disadvantage [10, 11]. Indeed, SGMs may experience SGM-specific stigma (e.g., homonegative discrimination) and non-SGM-specific stigma (e.g., HIV stigma and racism). Intersectionality provides a framework for understanding the multiple, intersecting identities that individuals embody within interlocking social systems of privilege and oppression [10–12]. Thus, a summary of SGM intervention literature is needed to comprehensively document how interventions address the multiple sources of the stigma that SGMs face and whether intersectionality is considered in health interventions implemented among diverse SGMs.

Current study

The current review investigates the integration of stigma into interventions targeting SGM psychological and behavioral health. We identified ways in which intervention content addresses stigma, how interventions directly intervene on stigma, and whether intervention efficacy is mediated or moderated by stigma. Finally, we reviewed the use of intersectional frameworks for intervention development and implementation among SGMs to determine whether these interventions address the many intersecting types of stigma SGM experience.

METHODS

We searched for empirical intervention studies among SGMs using PyscINFO and PubMed databases in July 2019 (study protocol [registered at Prospero Record ID CRD42020148605]). Search results included at least one stigma keyword (e.g., stigma, discrimination, and minority stress), one intervention keyword (e.g., intervention, clinical trial, and pilot), and one population keyword (e.g., bisexual, gender minority, and transgender) in paper titles or abstracts. The search was limited to English language, peer-reviewed papers published between January 1, 2003 (after the publication of Meyer’s [8] study of sexual minority stress) and July 10, 2019. Three authors reviewed titles and abstracts for the following eligibility criteria: (a) SGM sample, (b) empirical results of a behavioral or psychological intervention, and (c) inclusion of stigma in intervention content, intervention outcomes, or as a mediator or moderator of intervention effects. We included all types of behavioral interventions (e.g., prevention programs and psychotherapy). Strictly biomedical or surgical interventions were excluded. Stigma was defined broadly across multiple levels [13] to include individual internalized (internalization of negative societal attitudes) and anticipated (sensitivity to or expectation of stigma), interpersonal enacted (expressed by one person to another), and structural stigma (societal, cultural, or institutional norms and policies) and was inclusive across identity statuses to include both SGM stigma (e.g., transphobic discrimination) and non-SGM stigma experienced by SGMs (e.g., HIV stigma and racism). Eligible studies reported either exclusively SGM samples or explicit SGM subsample analyses. Interventions described in multiple papers were included as a single intervention.

Extracted data included sample sexual orientation, gender identity, race/ethnicity, age, and intervention geographic location. Coded intervention design characteristics included trial type, program content, level (e.g., individual and group), targeted health outcomes, adapting for SGMs, and adapting, if any, to additional identities or stigma beyond SGM status (e.g., intersectional frameworks and adapting procedures). To identify integration of stigma, we coded how stigma was included in the intervention (content, targeted outcome, and mediator/moderator) and identified the stigma level (internalized, anticipated, enacted, and structural) and type (e.g., bullying, identity concealment, and internalized homonegativity).

RESULTS

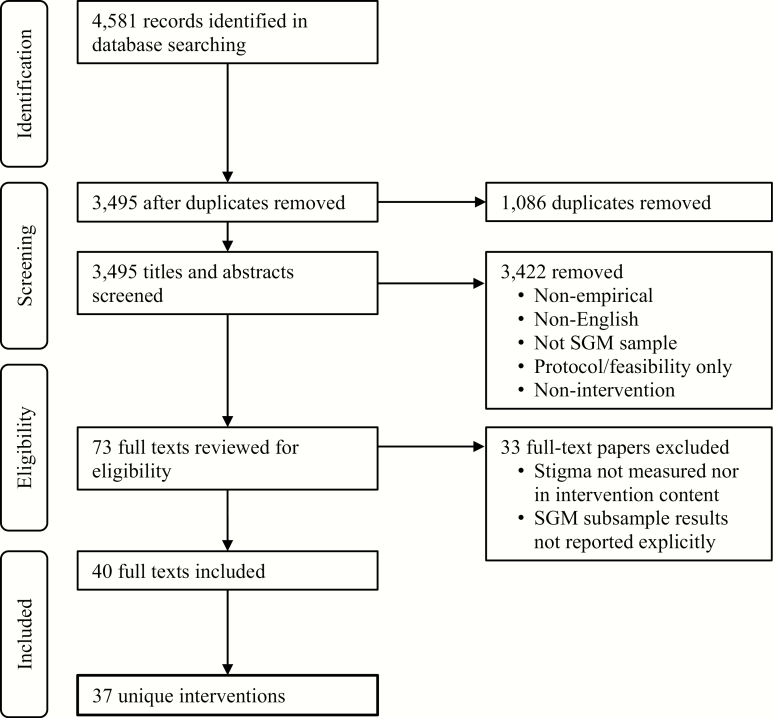

We identified 4,581 potentially eligible papers (Fig. 1). Thirty-seven interventions met eligibility criteria and comprised the final sample. Most were published in the last 5 years (75.7%, n = 28; 2015–2019). Individual (32.4%, n = 12), group (43.2%, n = 16), community (13.5%, n = 5), and multilevel interventions (10.8%, n = 4) were represented. Sample demographics are summarized in Table 1. Interventions most frequently included individuals who were gay men (48.6%, n = 18), bisexual men (37.8%, n = 14), or men who have sex with men (MSM; 27.0%, n = 10). Some interventions (24.3%, n = 9) included transgender participants, fewer included gender-nonbinary or gender-nonconforming participants (8.1%, n = 3) [14–16], and many did not disaggregate gender identities (43.2%, n = 16). Taken together, intervention studies included 16,872 SGMs (90.7% men, 9.2% women, and 0.1% nonbinary). Transgender participants comprised at least 0.6% of men and 14.5% of women. The unweighted average age across interventions was 29.7 years old (SD = 9.7). A complete list of interventions with summary of content, target population, and approach to addressing stigma can be found in Table 2.

Fig 1.

Inclusion and exclusion process according to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Table 1.

Demographic summary of interventions

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| Africa | ||

| Senegal | 1 | 2.7 |

| Asia | ||

| China | 2 | 5.4 |

| Thailand | 1 | 2.7 |

| Australia/New Zealand | 3 | 8.1 |

| North America | ||

| Canada | 4 | 10.8 |

| Mexico | 2 | 5.4 |

| USA | 24 | 64.9 |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| All Asian/predominantly Asian | 2 | 5.4 |

| All Black/predominantly Black | 9 | 24.3 |

| All Latino/predominantly Latino | 4 | 10.8 |

| All White/predominantly White | 13 | 35.1 |

| Racially diverseb | 7 | 18.9 |

| Not reported | 2 | 5.4 |

| Gender identityc | ||

| Men | ||

| Transmen only | 4 | 10.8 |

| Cismen or not specified | 28 | 75.7 |

| Cismen and transmen | 2 | 5.4 |

| No men | 3 | 8.1 |

| Women | ||

| Transwomen only | 6 | 16.2 |

| Ciswomen or not specified | 7 | 18.9 |

| Ciswomen and transwomen | 1 | 2.7 |

| No women | 23 | 62.2 |

| Gender-nonbinary/nonconforming | 3 | 8.1 |

| Sexual orientationd | ||

| Asexual | 4 | 10.8 |

| Bisexual/pansexual | 16 | 43.2 |

| Gay | 18 | 48.6 |

| Heterosexuale | 5 | 13.5 |

| Lesbian | 7 | 18.9 |

| MSM | 11 | 29.7 |

| Queer | 6 | 16.2 |

| Questioning | 2 | 5.4 |

| Same-sex attracted | 10 | 27.0 |

| Age group | ||

| Youth (under 18) | 3 | 8.1 |

| Young adults (18–30) | 6 | 16.2 |

| Youth and young adults (12–30) | 5 | 13.5 |

| Adults (18+) | 14 | 37.8 |

| Not reported | 9 | 24.3 |

n = 37.

MSM men who have sex with men.

aRace/ethnicity predominance indicated by a single racial/ethnic group comprising more than 50% of the sample.

bNo single race group exceeded 50% of the sample.

cStudies reporting gender as male or female without specifying cisgender or transgender were grouped with cisgender and marked as nonspecified.

dPercentages do not total to 100% because a single sample may have included many different orientations.

eHeterosexual orientation indicates sexual and gender minority (SGM) sample including heterosexually identified participants; heterosexual comparison groups are not accounted for in this table.

Table 2.

Intervention and stigma summary

| Name | Intervention content | Primary outcomes | Population | Stigma type | Stigma level | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level interventions | ||||||

| Healthy Choices [30] | Motivational interviewing intervention for HIV-positive youth and health care providers | Receptive anal sex, drug use for sexual pleasure, and STIs | Gay and bisexual men | HIV stigma | Internalized, anticipated | Mediator |

| SOLVE [53] | Online intervention targeting sexual shame and risky sexual behaviors | Condomless anal sex, shame | Young MSM | Shame | Internalized | Outcome; mediator |

| ESTEEM [36, 37] | In-person intervention using cognitive-behavioral skills to help participants directly address minority stress | Depression, anxiety, condomless sex, alcohol use, stigma coping | Gay, bisexual, and queer men | Explicit and implicit internalized homophobia, concealment | Internalized, anticipated | Outcome; moderator |

| RISE [27] | Web-based modules about social and cognitive aspects of internalized binegativity and attitudinal change. | Internalized binegativity | Bisexual individuals | Internalized binegativity, concealment | Internalized, anticipated | Outcome |

| ART adherence reminders [28] | Two-way SMS reminder messages for medication adherence | ART adherence | Men living with HIV | HIV stigma and discrimination | Enacted | Outcome |

| Expressive writing [35] | Brief expressive writing exercises about gay-related trauma or stress | Affect, gay-specific functioning and stress | Gay men | Gay-related rejection sensitivity | Anticipated | Outcome |

| Evaluative conditioning [58] | Internet-based intervention targeting self-esteem and self-efficacy to decrease homonegativity internalization | Internalized homophobia; self-esteem | Gay men | Internalized homophobic stigma | Internalized | Outcome |

| CBT skills intervention [29] | CBT intervention for HIV-related distress and mental health and for integration in health care settings | Depressive thoughts, anxiety, and HIV-stigma distress | MSM | HIV stigma | Internalized | Outcome |

| Latinos Empowering Ourselves [44] | Intervention to prevent HIV transmission by improving self-efficacy and self-empowerment | Condomless sex; condom self-efficacy | Latino gay and bisexual men | Sexual minority stigma, internalized homophobia | Enacted, anticipated, internalized | Content only |

| PrEPTECH [51] | Telemedicine, home PrEP delivery, and at-home STI testing; intervention targeting barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence | PrEP initiation; daily adherence | Young MSM of color | PrEP stigma | Anticipated | Content only |

| Healthy Relationships [31] | Intervention delivered in primary care settings that targeted coping skills to promote HIV-related health | Condom use; depression, anxiety, substance use, HIV status disclosure | Gay men | HIV stigma, mental health stigma | Internalized | Content only |

| Rainbow SPARX [34] | Computerized CBT video game addressing emotion regulation in response to stigma | Depressive symptoms | Sexual minority youth | Internalized homophobia, heterosexism, rejection, bullying | Internalized, anticipated, enacted | Content only |

| Group-level interventions | ||||||

| Somatic Experiencing [14] | Intervention targeting coping with gender minority stigma and gender dysphoria to improve mental health | Depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms, quality of life, coping with discrimination | Gender minorities | Gender minority stigma | Enacted | Moderator |

| 2GETHER [23] | Individual and group-based couples intervention to improve relationship functioning and sexual health | Sexual risk behavior, HIV prevention behaviors | Sexual minority men | Internalized homonegativity | Internalized | Moderator |

| Project PRIDE [17] | Intervention focused on coping in response to minority stress, substance use reduction, and mental health concerns | Mental health, internalized homonegativity, substance use, sexual risk, self-esteem | Sexual minority young men | Internalized homonegativity, concealment | Internalized, anticipated | Outcome |

| La Familia [18] | Group discussions focused on sexual orientation disclosure, family rejection, and oppression of immigrant, Latino MSM | Condom use and intentions, sex and substance use coping | Latino MSM | Internalized homophobia, disclosure discomfort | Internalized, anticipated | Outcome |

| Modified Group CBT [19] | Manualized CBT intervention for depression | Internalized and anticipated stigma, depression | Sexual minorities | Internalized homophobia | Internalized | Outcome |

| Queer Women Conversations [20] | Group psychoeducational sessions with content on personal goal setting, coping, sex and bodies, sexual and internalized stigma, and relationships | Sexual risk behavior, sexual stigma | Sexual minority women | Sexual stigma, internalized homophobia | Internalized, enacted, structural | Outcome |

| Life Skills for Men—Adaptation [16] | Peer-led group intervention focused on HIV risk including adapted topics (e.g., identity affirmation; communication and partner negotiation; coming out; sexual practices; and HIV) | HIV risk and sexual behaviors | Transgender MSM | Internalized homophobia, prejudice, cisgender male stigma | Internalized, enacted | Outcome |

| Health Mpowerment [21, 22] | Mobile web-based intervention to reduce logistical, financial, and stigma barriers to HIV prevention and care with support through online forums and support | Barriers to HIV prevention and care, stigma coping | Black MSM | HIV stigma, internalized homophobia, sexual prejudice | Internalized, enacted | Outcome |

| Acceptance and compassion-based group therapy [32] | Group psychotherapeutic intervention targeting the mental distress associated with internalized HIV stigma | HIV stigma, cognitive flexibility | MSM | HIV stigma | Internalized | Outcome |

| Web-based peer counseling [40] | A video-interactive, internet-based peer counseling intervention for an at-home HIV-testing program | Transportation and anticipated HIV stigma as barriers to HIV testing | Gay and bisexual men | HIV stigma | Anticipated | Outcome |

| All Gender Health [50] | Group prevention and sexual health education program using lectures, video, music, and discussion developed for transgender and gender-nonconforming populations | Safe sex self-efficacy, condom use and attitudes, number of casual partners, relationship monogamy | SGM | Gender minority stigma, transphobic discrimination | Enacted | Content only |

| AFFIRM [15] | Group CBT intervention with integrated sexual and gender affirming practice to improve coping and mental health | Depression and reflective stigma coping skills | SGM youth | Transphobic stigma | Enacted | Content only |

| TIM Project: A Black Young Men’s Health Study [45] | Facebook group intervention with videos and chats to improve HIV testing through HIV education, social support, and self-management | HIV testing | Black young MSM | HIV stigma | Enacted | Content only |

| Still Climbin’ [41] | Group CBT intervention targeting coping with minority stress across multiple stigmatized identities | Coping with discrimination | Black MSM | HIV, race, sexual orientation discrimination | Enacted | Content only |

| SSSR Program [24, 26] | Group-based couples intervention on relationship skills for same-sex male couples (e.g., communication; problem-solving; negotiating monogamy; and minority stress coping) | Relationship communication and satisfaction, minority stress coping | Sexual minority men | Homophobia | Internalized, enacted, structural | Content only |

| SSSR—female adaptation [25] | Group intervention focused on relationship education skills for same-sex female couples; adapted SSSR with female same-sex couple content | Relationship functioning, minority stress coping | Sexual minority women | Homophobia | Internalized, enacted, structural | Content only |

| Community-level interventions | ||||||

| POSSE [46] | Popular opinion leaders delivered intervention sessions with HIV risk reduction messages to young people in the House and Ball community | Sexual risk behavior, HIV stigma | Black young MSM and transwomen | HIV stigma | Enacted | Outcome |

| Out in Schools [42] | Film screenings in schools followed by facilitated dialogue about SGM experiences; both sexual minority and nonminority students participated | Suicide ideation, bullying discrimination, and school connectedness | Heterosexual and sexual minority youth | Discrimination, bullying | Enacted | Outcome |

| hivstigma.com [47] | Media campaign followed by moderated online blogs and forums aimed at reducing HIV stigma | HIV stigma | Sexual minority men | HIV stigma | Enacted | Outcome |

| Connect-To-Protect [33] | Community resource changes to decrease HIV stigma via community partner mobilization, targeting MSM, injection drug users, or heterosexual women | HIV stigma, HIV-related community resources | Young MSM, drug users, heterosexual women | HIV stigma | Internalized | Outcome |

| Combination Prevention Programme [39] | Multisite, multicity behavioral, biomedical, and structural interventions targeting HIV transmission and stigma in Mexico | Condom usage, HIV testing, awareness of HIV status, perceived stigma | MSM | HIV stigma, healthcare discrimination | Anticipated | Content only |

| Multilevel interventions | ||||||

| Life Skills [48] | Peer-led groups and individual intervention focused on HIV risk with transgender-specific topics (e.g., transgender pride, medical care, housing, and employment; sexual negotiation) | HIV risk reduction | Transwomen | HIV stigma, gay-related stress | Enacted | Outcome |

| Health Mpowerment—community adaptation [43] | Community-level intervention using peer outreach and small group to discuss HIV testing and safer sex topics | HIV testing, safe sex | Black MSM and transwomen | Racism, homophobia, comfort with being gay | Enacted, internalized | Outcome |

| Reducing stigma and increasing health [52] | Multitiered community intervention aimed at mitigating healthcare stigma as a barrier to HIV prevention | Stigma mitigation | MSM and female sex workers | Health care discrimination | Enacted, anticipated | Outcome |

| LA-ICCSSCH [49] | Individual and structural interventions targeting housing discrimination and HIV stigma to reduce HIV transmission | HIV stigma as barrier to HIV care, HIV education and prevention | Black MSM and people living with HIV | Housing discrimination, HIV stigma | Enacted | Outcome |

CBT cognitive behavioral therapy; MSM men who have sex with men; SGM sexual and gender minority.

Stigma in sexual and gender minority interventions

Stigma was operationalized across internalized (64.8%, n = 24), anticipated (32.4%, n = 12), enacted (67.8%, n = 21), and structural levels (8.1%, n = 3). For internalized stigma, interventions most frequently reported addressing internalized homophobia/homonegativity/binegativity (27.02%, n = 10) [16–27]. Internalized HIV stigma was the most commonly addressed non-SGM stigma (16.2%, n = 6) [28–33]. HIV stigma, though non-SGM specific, was addressed across all levels of stigma. Anticipated stigma most frequently included rejection sensitivity and fear (10.8%, n = 4) [18, 34–37], concealment (8.1%, n = 3) [17, 27, 37, 38], and HIV stigma (8.1%, n = 3) [30, 39, 40]. Enacted stigma most frequently included sexual minority discrimination (24.3%, n = 9) [19, 20, 24–26, 34, 41–44], HIV stigma (16.2%, n = 6) [41, 45–49], and transgender stigma (8.1%, n = 3) [15, 16, 50]. Structural stigma was addressed in three interventions [20, 24–26]. Interventions most frequently intervened on HIV transmission (54.1%, n = 20) and, to a lesser extent, mental health concerns (18.9%, n = 7).

Stigma in intervention content

Interventions were developed for SGMs (48.6%, n = 18), adapted from non-SGM interventions (13.5%, n = 5), adapted from interventions serving other SGM subpopulations (e.g., intervention for sexual minority men adapted for bisexual people of any gender [27]; 13.5%, n = 5), or implemented without SGM-specific considerations in content design or cultural adaptation (24.3%, n = 9). Novel interventions developed for implementation among SGMs relied on input from SGM health experts, community members, and advisory boards. Among interventions not adapted or developed for SGMs, all addressed HIV vulnerability or HIV stigma primarily among sexual minority men [28–30, 32, 39, 40, 49, 51, 52].

Intervening on stigma

Over half (64.9%, n = 24) of interventions intervened directly on stigma and measured intervention effect on stigma reduction. Individual and group interventions predominantly focused on reducing internalized homonegativity and binegativity, internalized HIV stigma, and anticipated stigma. Some interventions focused on individual’s response to stigma (e.g., generating social support for participants experiencing enacted discrimination) [21, 22, 27, 30]. No interventions directly intervened on structural stigma, though some community-level interventions sought to create broader environmental change through reducing enacted stigma (e.g., [42]). Other community-level programs mobilized partners [33], developed media campaigns [47], identified discrimination in the community [49], or trained popular opinion leaders [46] to increase healthy behavior and reduce stigma through community engagement.

Mediation and moderation

Only five studies statistically tested stigma as a mediator (5.4%, n = 2) or moderator (8.1%, n =3) of intervention effects. Experiences of internalized HIV stigma did not mediate intervention effects in one intervention [30], whereas reductions in condomless anal intercourse in the Socially Optimized Learning Virtual Environments (SOLVE) intervention were fully mediated by reductions in experiences of sexual shame [53]. Discrimination coping [14] and internalized stigma [23, 37] moderated intervention effects.

Intersectional stigma and adaptation

Less than half (45.9%, n = 17) of interventions considered additional identities or stigma beyond SGM status. Some interventions used community evaluation and feedback to develop programs for sexual minority men of specific racial/ethnic groups, including Black [21, 40, 45, 46, 49, 54] and Latino men [18, 44] and men of color broadly [51]. Other interventions accounted for regional, cultural differences by adapting to the needs, barriers, and lived experiences of SGMs in China [29], Mexico [31], and Thailand [30]. A limited number of programs were developed on the intersections of gender and sexual orientation: two were designed or adapted for sexual minority women [20, 25] and one for transgender sexual minority men [16]. Interventions also considered the unique needs of SGMs living with HIV [31, 41, 44, 49], SGMs with a history of incarceration [49], and SGM immigrants to the USA [18]. The use of intersectional theory was scarce, with only one intervention [49] explicitly naming an intersectional framework [11]. The Health Mpowerment community adaptation and Still Climbin’ were the only two interventions to report intervention effects on racial stigma [41, 43], with mixed efficacy. No studies reported measures of intersectional stigma nor examined multiple sources of stigma within the same models.

Potential bias

About one third (n = 13) of interventions included fewer than 50 participants. Pilot tests were common (n =26), and only 12 studies described randomization into treatment. Most studies (n = 25) collected follow-up data at least 1 month after intervention.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this systematic review build on previous research identifying interventions that sought to reduce prejudice and stigma against sexual minorities [55] by reviewing evidence-based interventions addressing experiences of stigma among SGMs. Minority stress theory represents one of the most widely used models to explain health disparities experienced by SGM populations [8], which highlights the need for interventions to both consider and directly intervene on stigma. The more recent integration of minority stress theory with intersectionality frameworks expanded the understanding of how stigma related to multiple marginalized identities may uniquely impact some groups within the SGM community [10, 11]. Thus, we sought to systematically examine the extent to which such minority stress and intersectionality frameworks were used to develop new or adapted interventions, directly intervene on stigma-related processes, and examine the role of stigma in intervention efficacy. Of the 37 distinct interventions, we identified all included stigma within the intervention content, though few considered stigma reduction as an intervention outcome, limiting our knowledge of how effectively these interventions reduce stigma directly. Even fewer interventions examined stigma as a mechanism of intervention effects as predicted by minority stress theory [30, 53]. Few studies tested stigma as a moderator of intervention efficacy [14, 23, 37], which would inform how individual exposure to stigma alters program efficacy.

Detailed examination of studies included in our review provided evidence that interventions are now including diverse types (e.g., homonegativity, transgender stigma, and bullying) and levels (e.g., anticipated and enacted) of stigma in intervention content, indicating a nuanced understanding of the effects of stigma on SGMs. Despite designing intervention content to address the role of minority stress and, in some cases, testing the efficacy of the intervention in addressing stigma, few studies examined the mechanistic impact of stigma on intervention efficacy as either a mediator or effect modifier. The cultural appropriateness of the interventions was no doubt enhanced by considering the role of minority stress and stigma in the development of intervention content, though quantitatively assessing differences between adapted and nonadapted interventions is critical for better understanding the effect of addressing stigma in intervention success. Few interventions addressed structural stigma or called for meaningful structural change. Future intervention should consider the effect of stigma across multiple levels, including structural, to better capture the context within which SGM experience stigma [56].

Few interventions developed content designed to address the intersection of multiple identities and none quantitatively assessed stigma intersectionally. A major challenge is no doubt the complexity of capturing and analyzing quantitative intersectional data [10] and the relatively few validated measures of intersectional stigma among SGMs. Moreover, the most prominent intersecting identities in the reviewed interventions were SGMs and racial/ethnic identities, which highlights the need to consider not only racial/ethnic stigma and SGM stigma but also the intersectional stigma experienced uniquely by those who are both SGMs and racial/ethnic minorities. Intervention developers should address stigma at intersections of multiple marginalized identities, many of which were evident in the SGM samples in the studies reviewed—such as gender, gender expression, socioeconomic position, immigration status, intellectual and physical ability, and history of incarceration. The recent development in intersectional stigma measurement facilitates investigation of mechanisms mediating the association of intersectional stigma with health outcomes and points to the need to consider diverse measurement across levels and intersections of stigma [57]. Interventions that do not adequately consider the interlocking systems of power and oppression, including structural stigma [56], may miss evidence of differential intervention efficacy and, ultimately, risk propagating health disparities for SGM subgroups with multiple marginalized identities.

Overall, the majority of SGM interventions published to date were focused on HIV-related outcomes among sexual minority men. Indeed, more than 90% of participants in these intervention studies were men. Thus, significant gaps remain in addressing the wide range of health conditions among diverse SGMs. Interventions developed for cisgender women and gender-diverse people were uncommon and conclusions of effectiveness were based on a much smaller subsample than interventions among men. With extensive evidence of diverse health disparities among subgroups of SGMs, both research and funding must evolve to support intervention that addresses broader SGM health issues, not just HIV among sexual minority men.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations of the current review that are worth noting. First, the nature of the review necessitated a focus on published literature, which may exclude important, on-going and unpublished studies (e.g., null findings). It is possible that the consideration of intersectionality may not be a primary aim of reviewed studies and, thus, was not prominently described in reviewed papers. We also relied on a search of the literature using two databases, and it is possible that some published studies were not identified despite our best efforts. Further, studies of structural stigma may be framed within policy research rather than intervention research aimed at enacting individual-level change.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, many interventions focusing on SGM populations have taken minority stress frameworks into account in the design and implementation, mostly within intervention content. Fewer studies have tested stigma directly as an outcome or as a mediator or moderator of intervention efficacy. We did not identify any studies that took an explicit quantitative approach to examining the intersection of multiple stigmatized identities within the intervention. The literature to date is predominated by studies of sexual minority men, with a heavy emphasis on HIV and mental health and, thus, there is significant need to expand not just in considering intersectional identities but also focusing on other subsets of the SGM population and the full range of health needs for these groups. In addition to expanding the focus of interventions, novel methodologies are needed to expand the ability to quantitatively consider intersectional frameworks within the context of intervention trials.

Funding:

E.K.L. was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50DA010075). J.A.C. was supported by the Research Initiative for Scientific Enhancement (RISE) fellowship from Hunter College. N.S.P. and K.M.N. are supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH078788, K23MH109346). J.C.S. was supported in part by a diversity supplement from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U19HD089875-03S2). The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or Hunter College.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions: E.K.L., J.A.C. and N.S.P. contributed to data collection and screening, systematic review and data coding, and manuscript development. E.K.L. and J.C.S. wrote the background literature section. K.M.N., C.P.B., H.J.R. contributed to manuscript development and editorial support. E.K.L. and H.J.R. wrote the discussion section. All authors contributed to study development and design.

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This study does not involve human participants and informed consent was, therefore, not required.

References

- 1. Bränström R, Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Sexual orientation disparities in physical health: Age and gender effects in a population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(2):289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reisner SL, Greytak EA, Parsons JT, Ybarra ML. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: Disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. J Sex Res. 2015;52(3):243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams SL, Mann AK. Sexual and gender minority health disparities as a social issue: How stigma and intergroup relations can explain and reduce health disparities. J Soc Issues. 2017;73(3):450–461. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee JH, Gamarel KE, Bryant KJ, Zaller ND, Operario D. Discrimination, mental health, and substance use disorders among sexual minority populations. LGBT Health. 2016;3(4):258–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N. Sexual orientation disparities in cardiovascular biomarkers among young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(6):612–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonvicini KA. LGBT healthcare disparities: What progress have we made? Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(12):2357–2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):368–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chaudoir SR, Wang K, Pachankis JE. What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit.” J Soc Issues. 2017;73(3):586–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110(2014):10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bowleg L. When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59(5–6):312–325. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscriminatoin doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg For. 1989;1989(1):139–167. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):985–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Briggs PC, Hayes S, Changaris M. Somatic experiencing informed therapeutic group for the care and treatment of biopsychosocial effects upon a gender diverse identity. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin A, Craig SL, D’Souza SA. An AFFIRMative cognitive behavioral intervention for transgender youth: Preliminary effectiveness. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2018;49(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reisner SL, Hughto JM, Pardee DJ, Kuhns L, Garofalo R, Mimiaga MJ. LifeSkills for men (LS4M): Pilot evaluation of a gender-affirmative HIV and sti prevention intervention for young adult transgender men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2016;93(1):189–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith NG, Hart TA, Kidwai A, Vernon JRG, Blais M, Adam B. Results of a pilot study to ameliorate psychological and behavioral outcomes of minority stress among young gay and bisexual men. Behav Ther. 2017;48(5):664–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Melendez RM, Zepeda J, Samaniego R, Chakravarty D, Alaniz G. “La Familia” HIV prevention program: A focus on disclosure and family acceptance for Latino immigrant MSM to the USA. Salud Publica Mex. 2013;55(suppl 4:S491–S497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ross LE, Doctor F, Dimito A, Kuehl D, Armstrong MS. Can talking about oppression reduce depression? Modified CBT group treatment for LGBT people with depression. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2007;19(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Weaver J, Navia D, Este D. A pilot study of a group-based HIV and STI prevention intervention for lesbian, bisexual, queer, and other women who have sex with women in Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(6):321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barry MC, Threats M, Blackburn NA, et al. “Stay strong! keep ya head up! move on! it gets better!!!!”: resilience processes in the healthMpowerment online intervention of young black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2018;30(suppl 5):S27–S38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bauermeister JA, Muessig KE, LeGrand S, et al. HIV and sexuality stigma reduction through engagement in online forums: results from the HealthMPowerment Intervention. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):742–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feinstein BA, Bettin E, Swann G, Macapagal K, Whitton SW, Newcomb ME. The influence of internalized stigma on the efficacy of an HIV prevention and relationship education program for young male couples. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(12):3847–3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Whitton SW, Weitbrecht EM, Kuryluk AD, Hutsell DW. A randomized waitlist-controlled trial of culturally sensitive relationship education for male same-sex couples. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30(6):763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whitton SW, Scott SB, Dyar C, Weitbrecht EM, Hutsell DW, Kuryluk AD. Piloting relationship education for female same-sex couples: results of a small randomized waitlist-control trial. J Fam Psychol. 2017;31(7):878–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Buzzella BA, Whitton SW, Tompson MC. A preliminary evaluation of a relationship education program for male same-sex couples. Couple Fam Psychol Res Pract. 2012;1(4):306–322. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Israel T, Choi AY, Goodman JA, Matsuno E, Lin Y-J., Kary KG, Merrill CRS. Reducing internalized binegativity: Development and efficacy of an online intervention. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2019;6(2):149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mao L, Buchanan A, Wong HTH, Persson A. Beyond mere pill taking: SMS reminders for HIV treatment adherence delivered to mobile phones of clients in a community support network in Australia. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(4):486–494. 10.1111/hsc.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang JP, Simoni JM, Dorsey S, Lin Z, Sun M, Bao M, Lu H. Reducing distress and promoting resilience: A preliminary trial of a CBT skills intervention among recently HIV-diagnosed MSM in China. AIDS Care. 2018;30(suppl 5):S39–S48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rongkavilit C, Wang B, Naar-King S, et al. Motivational interviewing targeting risky sex in HIV-positive young Thai men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(2):329–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Flores-Palacios F, Torres-Salas N. Improving health and coping of gay men who live with HIV: A case study of the “healthy relationships” program in Mexico. Cogent Psychol. 2017;4(1):1–14. 10.1080/23311908.2017.1387952 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Skinta MD, Lezama M, Wells G, Dilley JW. Acceptance and compassion-based group therapy to reduce HIV stigma. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22(4):481–490. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miller RL, Janulis PF, Reed SJ, Harper GW, Ellen J, Boyer CB; Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Creating youth-supportive communities: outcomes from the connect-to-protect (C2p) structural change approach to youth HIV prevention. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45(2):301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lucassen MFG, Merry SN, Hatcher S, Frampton CMA. Rainbow SPARX: A novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22(2):203–216. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR. Expressive writing for gay-related stress: Psychosocial benefits and mechanisms underlying improvement. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(1):98–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pachankis JE, Cochran SD, Mays VM. The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(5):890–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Millar BM, Wang K, Pachankis JE. The moderating role of internalized homonegativity on the efficacy of LGB-affirmative psychotherapy: Results from a randomized controlled trial with young adult gay and bisexual men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(7):565–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pachankis JE, Rendina HJ, Restar A, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. A minority stress–emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychol. 2015;34(8):829–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Colchero MA, Bautista-Arredondo S, Cortés-Ortiz MA, et al. Impact and economic evaluations of a combination prevention programme for men who have sex with men in Mexico. AIDS. 2016;30(2):293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maksut JL, Eaton LA, Siembida EJ, Driffin DD, Baldwin R. A test of concept study of at-home, self-administered HIV testing with web-based peer counseling via video chat for men who have sex with men. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2(2):e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bogart LM, Dale SK, Daffin GK, et al. Pilot intervention for discrimination-related coping among HIV-positive black sexual minority men. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2018;24(4):541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Burk J, Park M, Saewyc EM. A media-based school intervention to reduce sexual orientation prejudice and its relationship to discrimination, bullying, and the mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents in western Canada: A population-based evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):1–16. 10.3390/ijerph15112447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Eke AN, Johnson WD, O’Leary A, et al. Effect of a community-level hiv prevention intervention on psychosocial determinants of HIV risk behaviors among young black men who have sex with men (ybmsm). AIDS Behav. 2019;23(9):2361–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C, Leu CS, et al. A randomized controlled trial to test an HIV-prevention intervention for Latino gay and bisexual men: lessons learned. AIDS Care. 2005;17(3):314–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Washington TA, Applewhite S, Glenn W. Using Facebook as a platform to direct young black men who have sex with men to a video-based HIV testing intervention: A feasibility study. Urban Soc Work. 2017;1(1):36–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hosek SG, Lemos D, Hotton AL, et al. An HIV intervention tailored for black young men who have sex with men in the house ball community. AIDS Care. 2015;27(3):355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Adam BD, Murray J, Ross S, Oliver J, Lincoln SG, Rynard V. hivstigma.com, an innovative web-supported stigma reduction intervention for gay and bisexual men. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(5):795–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Garofalo R, Johnson AK, Kuhns LM, Cotten C, Joseph H, Margolis A. Life skills: Evaluation of a theory-driven behavioral HIV prevention intervention for young transgender women. J Urban Health. 2012;89(3):419–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brewer R, Daunis C, Ebaady S, et al. Implementation of a socio-structural demonstration project to improve HIV outcomes among young black men in the deep south. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(4):775–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bockting WO, Robinson BE, Forberg J, Scheltema K. Evaluation of a sexual health approach to reducing HIV/STD risk in the transgender community. AIDS Care. 2005;17(3):289–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Refugio ON, Kimble MM, Silva CL, Lykens JE, Bannister C, Klausner JD. Brief report: prEPTECH: A telehealth-based initiation program for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in young men of color who have sex with men. a pilot study of feasibility. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;80(1):40–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lyons CE, Ketende S, Diouf D, et al. Potential impact of integrated stigma mitigation interventions in improving HIV/AIDS service delivery and uptake for key populations in Senegal. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(suppl 1):S52–S59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Christensen JL, Miller LC, Appleby PR, et al. Reducing shame in a game that predicts HIV risk reduction for young. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(suppl 2):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bauermeister JA, Muessig KE, LeGrand S, et al. HIV and sexuality stigma reduction through engagement in online forums: Results from the HealthMPowerment intervention. AIDS Behav. 2018;23(3):742–752. 10.1007/s10461-018-2256-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chaudoir SR, Wang K, Pachankis JE. What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit.” J Soc Issues. 2017; 73(3):586–617. 10.1111/josi.12233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Evans CR. Modeling the intersectionality of processes in the social production of health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2019;226:249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bauer GR, Scheim AI. Methods for analytic intercategorical intersectionality in quantitative research: Discrimination as a mediator of health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2019;226:236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fleming JB, Burns MN. Online evaluative conditioning did not alter internalized homonegativity or self-Esteem in gay men. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(9):1013–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]