Abstract

Background

Homozygous loss‐of‐function mutations in TSEN54 (tRNA splicing endonuclease subunit 54; OMIM: 608755) cause different types of pontocerebellar hypoplasias (PCH) including PCH2, PCH4, and PCH5. The study aimed to determine the possible genetic factors contributing to PCH phenotypes in two affected male infants in an Iranian family.

Methods

We subjected two affected individuals in a consanguineous Iranian family. To systematically investigate the susceptible gene(s), whole‐exome sequencing was performed on the proband and a novel identified variant was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. We also analyzed 26 relatives in three generations using PCR‐restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR‐RFLP) followed and confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Results

Physical and medical examinations confirmed PCH in the patients. Besides, the proband showed bilateral moderate sensorineural hearing loss and structural heart defects as the novel phenotypes. The molecular findings also verified that two affected individuals were homozygote for the novel synonymous variant, NM_207346.2: c.1170G>A; p.(Val390Val), in TSEN54. PCR‐RFLP and Sanger sequencing elucidated that the parents and 16 relatives were heterozygote for the novel variant.

Conclusion

We identified a novel synonymous variant, c.1170G>A, in TSEN54 associated with PCH in an Iranian family. Based on this study, we strongly suggest using “TSENopathies” to show the overlapped phenotypes among different types of PCH resulted from TSEN causative mutations.

Keywords: PCR‐RFLP, pontocerebellar hypoplasias, synonymous variant, TSEN54, whole‐exome sequencing

In this research, we identified a homozygous synonymous variant, c.1170G>A or p.(Val390Val), in TSEN54 (NM_207346.2). This variant is associated with pontocerebellar hypoplasia in the patient, but due to overlapped clinical features of PCH‐2, ‐4, and ‐5, we suggest using the "TSENopathies” term.

1. INTRODUCTION

The production of functional tRNAs is highly regulated and vital for every tissue and cell. The tRNA splicing endonuclease (TSEN) genes including TSEN2 (OMIM: 608753), TSEN15 (OMIM: 608756), TSEN34 (OMIM: 608754), and TSEN54 (OMIM: 610204) encode the subunits of the tRNA endonuclease which have an important role in RNA processing (Namavar, Barth, Baas, & Poll‐The, 2011; Namavar et al., 2010). It has been shown that mutations affecting various facets of this process can cause distinct clinical disorders, e.g., mutations in varied aminoacyl‐tRNA synthetases result in Usher syndrome (OMIM: 614504) (Abbott et al., 2017), hereditary spastic paraplegia (OMIM: 615625) (Halevy et al., 2014), and pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH; OMIM: 611523) (Budde et al., 2008).

Nowadays, PCHs have been classified into 10 types according to different clinical characteristics, neuroimaging findings, and genetic bases (Barth, 2000). For example, PCH2 (OMIM: 277470) is the most common and the first genetically described group of PCHs, while its frequency is rather low, i.e., one per 200,000 people (Maraş‐Genç, Uyur‐Yalçın, Rosti, Gleeson, & Kara, 2015). Mutations in TSEN2, TSEN34, and TSEN54 have been identified to be associated with PCH2 (Namavar, Eggens, Barth, & Baas, 2016). Mutations in TSEN54 can cause different types of PCHs (PCH2, PCH4, and PCH5) (Maraş‐Genç et al., 2015), while the underlying mechanisms by which these mutations result in the disease remain undiscovered. Likewise, the TSEN proteins themselves have been implicated in hindbrain malformations (Doherty, Millen, & Barkovich, 2013). Accumulating evidence suggests that mutations in TSEN54 can affect the brain and cerebellum and lead to neurological disorders as well as impaired brain functions (Namavar et al., 2010).

The TSEN54 is involved in the formation of a subunit of the TSEN complex that has an enzymatic crucial role in RNA processing and maturation of tRNA molecules. Pathogenic variants in the TSEN54 account for over 90% of patients with PCH2 and PCH4 (Namavar et al., 2011).

Herein, we introduced a novel variant, NM_207346.2: c.1170G>A; p.(Val390Val), in TSEN54 which was associated with PCH in a consanguineous Iranian family. Furthermore, using PCR‐restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR‐RFLP) followed by Sanger sequencing, we checked the allele frequency in 26 closely related family members. Because of the greatly overlapped phenotypes with well‐described types of PCH, e.g., PCH2, PCH4, and PCH5, we suggest using the “TSENopathies” term which encompasses all described phenotypes of PCHs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the local medical ethics committee of Royan Institute, Tehran, Iran, in 2019, under the ethical code of “IR.ACECR.ROYAN.REC.1398.13.” All participants provided written, informed consent before enrollment. They also were informed that all clinical and whole‐exome sequencing (WES) data would be used only for scientific and not for commercial purposes. All clinical information and medical histories were collected at the Department of Medical Genetics, DeNA laboratory, and Royan Institute, Tehran, Iran.

2.2. Patients

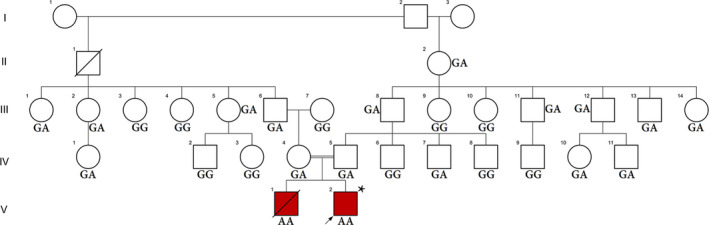

We examined two male infants (V.1 and V.2) with suspected PCH (Figure 1). V.1 had passed away before starting the experiment and his clinical data were obtained from his medical history. Although the blood sample of the proband (V.2) was accessible, to perform the genetic tests for V.1, the blood sample was collected from his remained bloody shirt. We also subjected 26 healthy relatives in three generations for genetic analysis.

Figure 1.

Pedigree of the family with PCH. An asterisk (*) indicates the sample that was selected for performing WES. In this pedigree, white symbols: unaffected who were homozygous for wild‐type allele; red symbol: affected and homozygous for c.1170G>A variant; squares: men; circles: females; parallel lines: consanguineous marriage; GG: original allele; GA: heterozygote; and AA: homozygous for c.1170G>A

2.3. Whole‐exome sequencing and cosegregation analysis

About 10 ml of peripheral blood was collected from each individual and genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted using the MagPurix kit (ZP02001, Zinexts company, Taiwan), and then, WES was applied based on the previous works (Method S1).

Samples from each parent and both affected patients (Figure 1) were subjected to Sanger sequencing to discern whether the causative homozygous variant in TSEN54 cosegregates with the disease phenotype or not. PCR was performed in a standard condition (Esmaeilzadeh‐Gharehdaghi, Razmara, Bitaraf, Mahmoudi, & Garshasbi, 2019), and sequence traces were analyzed using the Sequencher 4.7 program (Gene Codes Corporation, MI, USA).

2.4. Prediction of single point variation on splicing

Accumulating evidence suggests that synonymous (“Silent”) variants may impact protein expression and function (Andersson & Kurland, 1990; Chamary, Parmley, & Hurst, 2006; Czech, Fedyunin, Zhang, & Ignatova, 2010). In humans, synonymous variants have been shown to affect mRNA splicing (Chamary & Hurst, 2005), mRNA stability (Gu, Zhou, & Wilke, 2010), and/or mRNA secondary structure (Capon et al., 2004; Chamary & Hurst, 2005), translation efficiency and kinetics (Lavner & Kotlar, 2005; Tuller, Waldman, Kupiec, & Ruppin, 2010), protein folding (Kimchi‐Sarfaty et al., 2007), and protein function (Kimchi‐Sarfaty et al., 2007). We applied mFold (Zuker, 2003) and UNAFold (Markham & Zuker, 2008) (the static secondary structure predictors), KineFold (Xayaphoummine, Bucher, & Isambert, 2005) (a stochastic secondary structure predictor), and RNAsnp (Sabarinathan et al., 2013) to analyze the potential change of the minimum free energy (ΔG) in the mRNA fragments carrying the variant under investigation.

To in silico analyze the splicing variation, Human Splicing Finder (HSF) (http://www.umd.be/HSF3/) (Desmet et al., 2009) was utilized. In detail, HSF was applied to predict the formation or disruption of the splice donor site, splice acceptor site, exonic splicing silencer (ESS) site, and exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) site (Desmet et al., 2009). Similarly, the Potential effects of the variant on mRNA splicing were analyzed using the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP; https://www.fruitfly.org) (Spradling et al., 1999) and NetGene2 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetGene2) (Brunak, Engelbrecht, & Knudsen, 1991).

We also utilized CRYP‐SKIP (https://cryp‐skip.img.cas.cz/) (Divina, Kvitkovicova, Buratti, & Vorechovsky, 2009) program. This server analyzes significant predicting variables of cryptic splice site activation and exon skipping using a regularly updated logistic regression model. Furthermore, SpliceAid2 (Piva, Giulietti, Burini, & Principato, 2012) aiding to predict the splicing pattern alteration was utilized to guide the identification of the mutations/variants impacts molecularly and also to better understand the tissue‐specific alternative splicing (Piva et al., 2012).

2.5. Computational analysis of the variant's impacts on codon usage

Because of the general degeneracy of the genetic code, not all codons occur at the same frequency throughout the genome, i.e., a strong codon bias exists (Ikemura, 1985). Furthermore, it has been identified that different organisms have distinct codon biases (Ikemura, 1985); there is also a possibility that a difference in codon biases between tissues within the same organism can be detected (Dittmar, Goodenbour, & Pan, 2006; Sharp et al., 1988), reflecting tissue specificity in gene expression.

In this study, we assumed that the novel variant might affect the local speed of translation, impact cotranslational protein folding, and result in a protein by changing the conformation/specific activity. The overall impacts of a given codon change on the rate of translation or cotranslational protein folding might be detrimental causing a more substantial change in the codon usage frequency (Zhang, Hubalewska, & Ignatova, 2009). Therefore, in this study, we compared the codon usage frequencies of the variant versus wild‐type codon at the same location using the online in silico predictor (https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/codon_usage.html).

2.6. PCR‐restriction fragment length polymorphism

To screen the c.1170G>A (NM_207346.2) allele in the other 26 relatives, the PCR‐RFLP assay was designed and performed. The variant causes a gain of the RsaI restriction site (GTAC). The PCR products were digested with RsaI (Method S1). As the “Gold Standard” technique (Men, Wilson, Siemering, & Forrest, 2008), Sanger sequencing, in particular, was used to confirm the data of PCR‐RFLP.

2.7. Analysis of TSEN54 structure and location of the variant

Not every synonymous codon substitution would have an equal influence on protein folding in the cell (Tuller et al., 2010). The impact can be defined by the effects of variants on the stability and structure of protein folding intermediates forming along the cotranslational folding pathway (Tuller et al., 2010). Substitutions that affect codons encoding structurally important residues and/or protein fragments (e.g., domain linkers) have been suggested to impose more substantial effects on protein folding compared to other synonymous variants (Tuller et al., 2010).

To predict the possible effects of p.(Val390Val) on protein‐stability and ‐folding, the protein family and domains were analyzed using ScanProsite (Gattiker, Gasteiger, & Bairoch, 2002) and Sequence alignments of the human TSEN54 were recruited by using ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw). Also, a BLAST sequence search against the protein data bank (PDB) was performed to select the template structure with the closest sequence similarity to the domain of TSEN54, and finally, we used the template given for “RNA Recognition and Cleavage by a Splicing Endonuclease” (Xue, Calvin, & Li, 2006) (PDB ID: 2GJW) to build the favorite model.

2.8. Conservation analysis

An interesting question to consider is whether the variant is detected at the codon that encodes in wild‐type TSEN54 evolutionary conserved amino acid residue or not. The ConSurf (http://www.consurf.tau.ac.il) (Ashkenazy et al., 2016) and UCSC databases (https://genome.ucsc.edu) were exploited to provide an evolutionary conservation profile for TSEN54 to better discern the potential pathological identity of the variant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical assessments

The affected individuals (V.1 and V.2) were born to a consanguineous Iranian family with normal weights and lengths through spontaneous vaginal delivery at full term without any complications (Figure 1).

Biochemical blood tests for the mother (IV.4) were reported normal in her two pregnancy periods (Table S1). Meanwhile, the karyotype of the parents was normal (Figure S1). First‐trimester screening and quadruple tests showed no increased risk of aneuploidies. History of diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, systemic lupus erythematosus, pulmonary embolus, and smoking or alcohol consumption during pregnancy was negative for IV.4.

Investigations applied according to ultrasonography showed around 5 days' growth retardation in head (percentile 30%) of both fetuses (V.1 and V.2); this also revealed delayed growth of cerebellum (percentile 20%) at the gestational age (GA) of 28 weeks. This suggested that the abnormality in the patients was developmentally late‐onset and next to deliver time. In V.2, cisterna magna space was determined around 13 mm which was near the mega cisterna magna (28 weeks of GA) (Figure S2). Both fetuses were in a cephalic group with a grade 2 placentas. In sum, according to the medical histories, both fetuses revealed mega cisterna magna, small cerebellum, and slight skull‐growth restriction. The thalamo‐occipital distance was measured around 5.4 ± 0.3 mm for V.2.

Regarding V.1, the axial spiral brain CT‐scan at age 28 weeks GA showed hypodensity of the cerebral white matter in frontal areas, hypoplasia of lower margin of the vermis, and dural venous sinuses. The microcephaly was evident and documented in the V.2 at 35 weeks of GA (head circumference: 27.3 cm, percentile <3). Regarding V.2, the measured nuchal translucency (NT) with crown‐rump length 67.4 was 2.2 mm (at 28 weeks of GA) which was considered normal.

A positive history of seizure and mild abnormal electroencephalography have been reported for both affected individuals. For instance, V.2 was irritable at presentation and had already experienced several episodes of seizures and was hospitalized due to loss of consciousness, poor feeding, generalized hypotonia, seizure and suspicious widened anterior, and posterior fontanel.

Electromyography and also a nerve conduction study (NCS) was reported as normal for both patients, whereas echocardiography showed structural heart diseases in the proband including a large patent foramen ovale (>23 microbubbles), patent ductus arteriosus, and mild tricuspid and mitral valve regurgitations. Moreover, an auditory brainstem response (ABR) test showed bilaterally moderate sensorineural hearing loss in V.2.

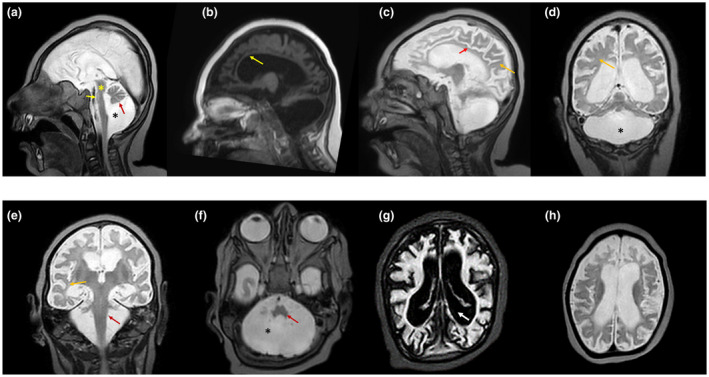

Complementary tests using brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the age of 22 months (V.2) showed supra‐ and infratentorial atrophy, hypoplasia of the pons, cerebellum and corpus callosum, delayed cerebral myelination and gray and white matter volume loss, absent folding of the olivary nucleus, and loss of transverse fibers of the pons. An extraaxial CSF space was also evident due to brain atrophy. An infratentorial chronic subdural hematoma was detected next to the Galen vein that had been developed in the line of anterior falx (Figure 2a–h). Other complications such as central visual impairments had not been observed in the patients (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of the proband (V.2). (a) Sagittal cut through the midline (T2‐W) shows the loss of transverse fibers of the pons (yellow asterisk), mega cisterna magna (black asterisk), hypoplasia of brainstem, cingulate gyrus, pons, vermis and cerebellar hemispheres (black arrow). The findings described would be highly compatible with pontocerebellar hypoplasia (black asterisk). (b) The corpus callosum is almost absent. (c) Hypoplasia of the cingulate gyrus (red arrow) and white matter (yellow arrow) are evident. (d and e) Lateral sagittal section (T2‐W) shows hypoplasia of the cerebellar hemispheres (asterisk). The white matter loss (delayed myelination) is also evident (yellow arrow). The red arrow shows the almost complete hypoplasia of the cerebellum. (f) Hypoplasia of cerebellum (asterisk) and pons (red arrow) is evident. (g) The coronal section (T2‐W) shows extremely small cerebellar hemispheres and extended vermal hypoplasia. Immaturity of the cerebral cortex and ventriculomegaly (white thick arrow) are also clearly evident. (h) Coronal sections show hypoplasia of the cerebellar hemispheres. An enlarged ventricle is visible and also there is an increased distance between the cortical surface and the skull evident, which is probably due to diminished brain growth in utero (IUGR)

Table 1.

Summary of clinical features of index patients (V.1 and V.2) in the family

| Patient | V.1 | V.2 (Proband) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of disease onset | At birth (congenital) | At birth (congenital) | |

| Gender (male/female) | Male | Male | |

| Age at death | 5 months | 22.5 months | |

| Ethnic origin | Iranian | Iranian | |

| Pregnancy duration | Full‐term | Full‐term | |

| Polyhydramnios | − | − | |

| Family history | − | + | |

| Weight at birth | 3.3 ± 0.2 kg | 3.4 ± 0.2 kg | |

| Head circumference at birth | 29.9 cm (percentile <3) | 30.1 cm (percentile <3) | |

| Age of diagnosis | NA | 18 months | |

| Intellectual disability | NA | + | |

| Intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) | + | + | |

| Irritability | + | + | |

| Seizure (age at onset) | + (4 months) | + (18 months) | |

| Visual findings | − | − | |

| Electroencephalography | Mild abnormality | Mild abnormality | |

| Motor findings | Spasticity | + | + |

| Limb hypertonia | − | − | |

| Generalized hypotonia | + | + | |

| Deep tendon reflexes | NA | NA | |

| Developmental milestones | Gross motor function | Delayed | Delayed |

| Fine motor function | Delayed | Delayed | |

| Language | NA | Delayed | |

| Cognitive | Delayed | Delayed | |

| Social interaction | ND | Delayed | |

| MRI findings | Cerebellum | Hypoplasia | Hypoplasia |

| Pons | Hypoplasia and loss of transverse fibers | Hypoplasia and loss of transverse fibers | |

| Cerebral cortex | Supratentorial/ infratentorial atrophy | Supratentorial/ infratentorial atrophy | |

| Ventricles | ex vacuo ventriculomegaly | ex vacuo ventriculomegaly | |

| White matter (WM)/gray matter | White and gray matter volume loss | White and gray matter volume loss | |

| Corpus callosum | Atrophy | Atrophy | |

| Genetic finding | c.1170G>A/c.1170G>A | c.1170G>A/c.1170G>A | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; ND, no data.

3.2. Whole‐exome sequencing findings

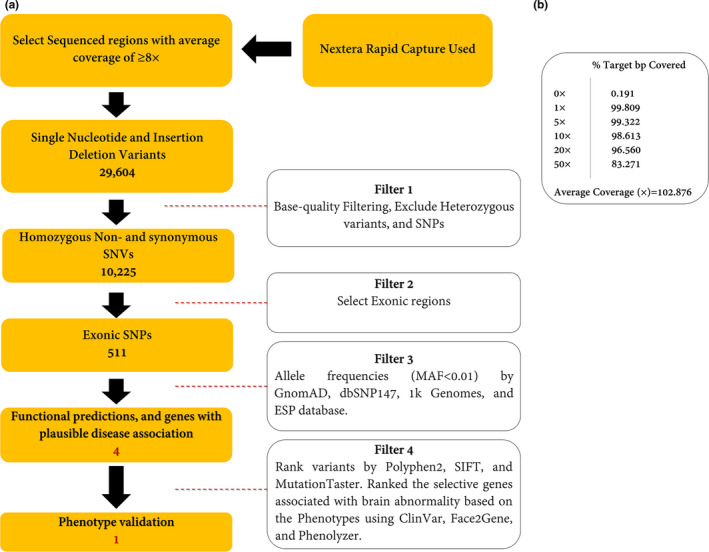

The WES was applied to V.2 with an average depth of 100× (Method S1). In total, 10,225 homozygous SNV and Indel variants were detected in the patient. By choosing the variant in exonic regions, 511 variants remained. By excluding the variants with MAF ≥1% in publicly available databases (e.g., dbSNP147 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP), 1000 Genomes Project (Li et al., 2009), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) (Karczewski et al., 2016), and gnomAD (Karczewski & Francioli, 2017), and Iranome (Fattahi et al., 2019), prioritizing according to their functional impacts, and choosing genes with plausible disease association, only four variants were obtained. Consequently, using phenotype analyzers, Face2Gene (Mishima et al., 2019) and Phenolyzer (Yang, Robinson, & Wang, 2015), a novel synonymous variant, NM_207346.2: c.1170G>A; p.(Val390Val), in TSEN54 was selected to cosegregate completely with the disease in the family (Figure 1). The schematic presentation of the applied steps is depicted in Figure 3. We also reclassified the variant based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics‐Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG‐AMP guidelines) (Biesecker & Harrison, 2018) into the “Pathogenic Variant.” The novel variant was submitted to Leiden Open Variation Database (LOVD; https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/individuals/00301207).

Figure 3.

(a) Variant filtering scheme used to prioritize the variants of exome data. Approximately 37 Mb (214,405 exons) of the Consensus Coding Sequences (CCS) were enriched from fragmented genomic DNA by >340,000 probes designed against the human genome (Nextera Rapid Capture Exome, Illumina) and the generated library sequenced on an Illumina platform to an average coverage depth ~100×. The regions with an average coverage of ≥8× were selected. Other procedures are discussed in the main text in detail. (b) Analysis of statistics WES. The average coverage was about 102.876×

3.3. Molecular findings

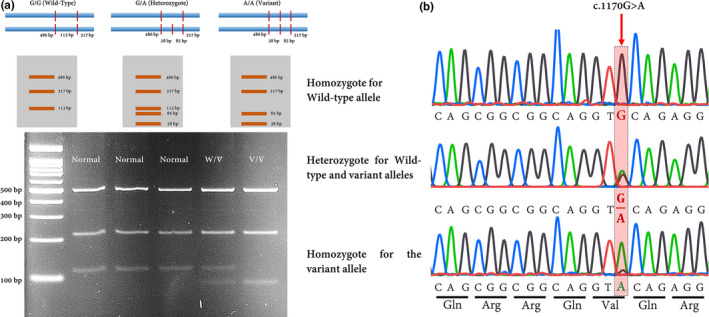

A novel synonymous variant was identified that was absent in dbSNP147, 1000 genome project phase 3, ExAC, Iranome, HGMD®, and ClinVar database. The variant also was not found in the literature. Sequencing of exon 8 of TSEN54 in available members verified that the variant, c.1170G>A, cosegregates with a PCH phenotype (Figure 1), i.e., the patients were homozygous for this variant. For further investigation, c.1170G>A variant was checked in 26 relatives of the family using the PCR‐RFLP technique which was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Results indicated that 16 subjects were heterozygous for the variant (GA), whereas 10 individuals only were carrying the wild‐type allele (GG) (Figure 4a,b).

Figure 4.

(a) A simple and rapid PCR‐RFLP assay for detecting c.1170G>A variant in the TSEN54 gene. This schematic figure showing the generated fragments after digestion with RsaI. The variant makes a new site for this enzyme. Agarose gel (2.0%) electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining following the RsaI digestion of the PCR products is shown. PCR‐RFLP results in normal control showing 486, 217, and 113 bp (A1) and after RsaI digestion (A2), a proband who was homozygously showing three distinct bands including 486, 217, and 85 bp. The 28 bp band is not seen in this figure; Normal is wild‐type allele (GG); W/V is heterozygote; and V/V is homozygous for c.1170G>A. (b) Chromatograms showing nucleotide sequences of TSEN54 in the regions of c.1170G>A which was detected in the family. The affected region is highlighted

Data resulted from CRYP‐SKIP showed that the variant can increase the probability of cryptic splice site activation (scores from 0.1 for wild‐type to 0.33 for the variant). Also according to SpliceAid2, the novel variant can make a new place for binding ZRANB2 protein. This protein is an SR‐like nuclear protein serving as a splicing factor that is required for alternative splicing of TRA2B/SFRS10 transcripts (Loughlin et al., 2009). Thus, this variant may interfere with constitutive 5′‐splice site selection. Furthermore, the HSF server revealed that the c.1170G>A substitution can alter an exonic ESE site resulting in the potential alteration of splicing (Table 2).

Table 2.

In silico prediction of pathogenicity of p.(Val390Val) in the family

| Variant | Gene/genomic position | Zygosity | HSF | Mutation taster | BDGP | NetGene2 | Mutpred splice | 1 K Genome | ExAC | Iranome | PROVEAN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (V.1 and V.2) | Mother (IV.4) | Father (IV.5) | |||||||||||

| c.1170G>A; p.(Val390Val) | TSEN54 (g.73518332G>A) | Hom. | Het. | Het. |

Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing. (ESE Site Broken) |

Disease‐causing Donor gained |

Creates a donor site | Creates a donor site (Confidence 0.88) |

Cryptic 5′ SS (p = 0.0028). The variant disrupts splicing. |

N.R | N.R | N.R | Neutral |

Abbreviations: Het, heterozygote; Hom, homozygote; N.R, not reported.

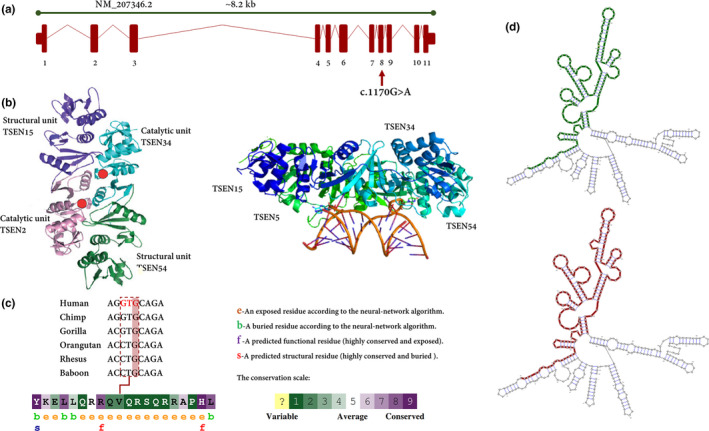

We also showed that the variant is located in exon 8 of TSEN54 which, in turn, encodes an important structural unit of TSEN complex (Figure 5a,b). The conservational analysis revealed that the variant is a highly conserved region in primates (Figure 5c). As discussed, synonymous mutations can change the mRNA structure. To address this concern, we used mFold, UNAFold, KineFold, and RNAsnp web servers. All of them verified that the variant can increase the ΔG of RNA folding (Figure 5d). Furthermore, data showed that c.1170G>A variant is capable of changing codon usage by substituting GTA instead of GTG. The latter is the preferred codon in human, while the former codon is less‐used.

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic genetic map of TSEN54 (NM_207346.2) and the c.1170G>A variant identified in the consanguineous family members. The c.1170G>A is located in exon 8. (b) The three‐dimensional structure is shown. This complex is composed of TSEN2, TSEN15, TSEN34, and TSEN54. TSEN15 and TSEN54 are structural units of TSEN complex, while TSEN2 and TSEN34 play an important role as catalytic units. After processing by the tRNA endonuclease, the intron is removed, resulting in the mature tRNA. (c) The amino acid sequence of GPT2 colored based on conservation scores by the ConSurf database. ConSurf demonstrates evolutionary conservation profiles for proteins of known/unknown structure according to the phylogenetic relations between homologous sequences as well as amino acid's structural and functional importance. To be on the safe side, the UCSC database used to show the conservation of specific regions including the variant site in vertebrae, with high brain function and structure. (d) The RNAsnp webserver output for the putative structurally variant. the variant can significantly increase the minimum free energy from −181.50 kcal/mol to −180.20 kcal/mol. The green lines show the optimal secondary structure of the global wild‐type sequence (970‐1370), while the red one is exhibiting the optimal secondary structure of the global variant sequence in the same region

4. DISCUSSION

Over 50 human diseases have been associated with synonymous mutations (Sauna & Kimchi‐Sarfaty, 2011) and it has been recently identified that nonsynonymous and synonymous variations have a similar probability of disease association (1.46% versus 1.26%, respectively) (Hunt, Simhadri, Iandoli, Sauna, & Kimchi‐Sarfaty, 2014). Moreover, they have a statistically equivalent effect size, suggesting that the list of disease‐causing synonymous mutations will grow (Chen, Davydov, Sirota, & Butte, 2010). In this study, we identified a novel synonymous variant in TSEN54 which was the most probable cause of PCH in the patients (Table 3). PCHs rare autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorders with prenatal onset, disrupting brain development (Malandrini et al., 1997).

Table 3.

TSEN54 gene‐related pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Adapted and extended from Namavar et. al (Namavar et al., 2011)

| PCH subtype | Gene | MIM | Clinical features | Lethality | Pathological features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCH2 | TSEN54, TSEN2, TSEN34 | 277470, 612389, 612390 | Clonus and impaired swallowing during neonatal period. In Infancy and later: chorea, variable spastic paresis; progressive microcephaly. variable neocortical atrophy, and pontocerebellar hypoplasia are evident in MRI. | In Infancy and childhood. | Cerebellar hypoplasia. Segmental degeneration of cortex. Fragmentation of cerebellar dentate nucleus. Neuron loss and decreased folding in Olivary nucleus. progressive loss of ventral nuclei and transverse fibers in pons, and progressive atrophy in Cerebral cortex. | Barth et al. (1995), Valayannopoulos et al. (2011) |

| PCH4 | TSEN54 | 225753 | Polyhydramnios, hypertonia, severe clonus, and/or contractures and primary hypoventilation are evident in neonatal period. Delayed neocortical maturation, pontocerebellar hypoplasia; microcephaly on autopsy are discernable from MRI. | Early postnatal death from apnea | Cerebellar hypoplasia: hemispheres ≫vermis, areas of stunted or absent folial development. Cerebellar dentate nucleus presents as tiny remnants. Olivary nucleus: absent folding and gliosis. Pons: loss of ventral nuclei and transverse fibers. | Budde et al. (2008), Chaves‐Vischer et al. (2000) |

| PCH5 | TSEN54 | 611523 | Seizures in Prenatal/neonatal period and clonus during neonatal period. Persistent clonus, microcephaly and pontocerebellar hypoplasia on autopsy during the following months. | Early postnatal death from apnea | Cerebellar hypoplasia: cortical involvement as in PCH4, but vermal cortex more extensively affected than hemispheric cortex; subtotal loss of cerebellar dentate nucleus. Olivary nucleus: absent folding. Pons: loss of ventral nuclei and transverse fibers. | Patel, Becker, Toi, Armstrong, and Chitayat (2006) |

It has been indicated that several candidate genes associated with congenital brain malformations (Najmabadi et al., 2011); however, very few studies have investigated genes related to PCHs (Namavar, Barth, & Baas, 2011). The majority of studies in this area have been subject to various limitations, e.g., in most studies, only one or two patients were investigated or the sample size was scant, so there is no possibility to distribute the results to the whole population. Previous studies have shown that the homozygous p.A307S missense mutation in TSEN54 is associated with PCH2 (Namavar et al., 2011), whereas it has been recently detected that a compound heterozygous mutation of c.919G>T and c.468+2T>C is associated with a more severe phenotype consistent with PCH type 5 (Namavar et al., 2011). The knockdown mouse model of TSEN54 led to the brain hypoplasia and loss of structural definition in the brain due to increased cell death via loss of functional mechanism (Kasher et al., 2011).

TSEN54 encodes a subunit of the tRNA splicing endonuclease (TSEN) complex involved in the identification and cleavage of RNAs from precursor tRNAs. This heterotetramer complex is composed of TSEN2, TSEN15, TSEN34, and TSEN54 (Figure 5b). The TSEN complex is also associated with a pre‐mRNA 3′‐end processing factor (Paushkin, Patel, Furia, Peltz, & Trotta, 2004). Additionally, the depletion of the TSEN complex causes defects in the maturation of pre‐tRNA and ‐mRNA (Paushkin et al., 2004). As stated in BrainSpan atlas (Atlas of the Developing Human Brain; http://www.brainspan.org/) (Hawrylycz et al., 2014), TSEN54 is one of the highly expressed genes in humans. The effects of codon usage on gene expression were previously thought to be mainly mediated by its impacts on translation (Robinson et al., 1984); however, Zhou et al. (2016) demonstrated that the impacts of codon usage are mainly due to effects on transcription, not translation. Based on the Sequence Manipulation Suite (sms2.0; https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/codon_usage.html), the preferred codon for Valine is GTG. The c.1170G>A variant can change this codon to GTA which is not preferred codon and its portion was determined approximately zero for humans through analyzing 1000 samples. The data were confirmed by the Genescript database (https://www.genscript.com/) introducing that GTA’s portion is 7.0% while GTG designated 47% of all Valine codons to itself. In this study, we predicted that the c.1170G>A variant can change the codon usage in the patients which may influence the transcription and translation rates. Any alteration in the expression of a single gene can change the levels of other genes and relevant pathways (Dagle & Weeks, 2001). In general, reducing the translation rate will increase the time available for N‐terminal portions of a protein to fold to a stable structure prior to the appearance of more C‐terminal portions (Sander, Chaney, & Clark, 2014). Data derived from RNA folding predicting databases confirmed that the c.1170G>A variant can change the RNA folding, i.e., this novel variant can increase the ΔG of mRNA folding (Figure 5d).

The three‐dimensional (3D) structure of the eukaryotic TSEN complex has not yet been solved. The large TSEN54 subunit takes a center stage in recognizing the precursor tRNA substrate and positioning the two catalytical subunits, TSEN2 and TSEN34, to their respective cleavage sites (Abelson, Trotta, & Li, 1998). We conjectured that the c.1170G>A can change the splicing process which would alter the 3D structure of TSEN54. It is conceivable that either the spatial changed peptide chain can interfere with the secondary structure of TSEN54 and/or might hinder the binding of TSEN54 to the target precursor tRNAs.

Namavar et al. also showed that TSEN54 was highly expressed in neurons of the pons, cerebellar dentate, and olivary nuclei during the second trimester of pregnancy, a determining period for the morphological development of these structures. Consistent with what has been found, the measured head circumference of the fetuses (V.1 and V.2) showed that the first symptoms were detectable after 28 weeks of pregnancy or in the third trimester; thus, applying genetic tests in suspected families are an asset to early diagnosis of such diseases. As well as, Namavar et al. showed that the nonsense or splice site mutations in TSEN54 were associated with a more severe phenotype of perinatal symptoms, ventilator dependency, and early death. In this study, we detected a broad range of overlapped symptoms, e.g., microcephaly and poor feeding (PCH7) absent folding and gliosis of olivary nucleus (PCH1, 2, 4, and 5), loss of ventral nuclei and transverse fibers on pons and hearing impairment (PCH1, 4, and 5), and cardiomyopathy (PCH6). We propose using the term “TSENopathies” to cover a wide range of symptoms. Besides, the proband showed structural heart diseases including a large patent foramen ovale (> 25 microbubbles), patent ductus arteriosus, and mild tricuspid and mitral valve regurgitations. The proband also showed bilateral moderate sensorineural hearing loss. All phenotypes have not been reported in association with PCH caused by TSEN mutations.

Taken together, we introduced a novel variant, c.1170G>A or p.(Val390Val), in two male neonates affected by PCH. We also checked the allele frequency in 26 relatives by PCR‐RFLP followed and affirmed by Sanger sequencing. In brief, we showed that homozygous c.1170G>A variant in TSEN54 causes PCH in two affected male individuals. Sanger sequencing and PCR‐RFLP showed that the parents (IV.4 and IV.5) were heterozygous and none of the relatives were homozygous for this variant. We strongly recommend doing a functional analysis and also further genetic screening in different ethnicities.

5. CONCLUSION

Nowadays, by using next‐generation sequencing, a list of genes responsible for various congenital brain malformations is rapidly growing. In this study, we used the WES to determine the possible genetic factors contributing to PCH phenotypes in two affected neonates in an Iranian family. This experiment adds to a growing corpus of research and suggests c.1170G>A or p.(Val390Val) variant in TSEN54 as a cause of PCH. These findings will not only enhance the clinical description and a better genetic diagnosis of PCH but also will illuminate the fundamental underlying molecular mechanisms. Although we provided adequate evidence to support the pathogenicity of p.(Val390Val) in PCH, to better understand the function of the TSEN54 protein, we strongly recommend doing functional analysis using the translational animal models.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors claim no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

MG conceived and designed the experiments. AS and FB conducted the experiments. MG, ER, ART, and NA analyzed and interpreted the data. MG and AS contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. ER, M.GA, and M.G. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Fig S2

Table S1

Method S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are very grateful to the patient and the family for their participation in this study and a research coordinator for collecting samples and processing genetic evaluations. We are especially grateful to the staff of the DeNA laboratory, Tehran, Iran, for helping us in this research. We also express our gratitude to Ms. Zahra Solati Mohammadi for her assistance in analyzing of whole‐exome sequencing data.

Sepahvand A, Razmara E, Bitarafan F, Galehdari M. A homozygote variant in the tRNA splicing endonuclease subunit 54 causes pontocerebellar hypoplasia in a consanguineous Iranian family. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1413 10.1002/mgg3.1413

Afrooz Sepahvand and Ehsan Razmara have contributed equally.

REFERENCES

- Abbott, J. A. , Guth, E. , Kim, C. , Regan, C. , Siu, V. M. , Rupar, C. A. , … Robey‐Bond, S. M. (2017). The usher syndrome type IIIB histidyl‐tRNA synthetase mutation confers temperature sensitivity. Biochemistry, 56(28), 3619–3631. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abelson, J. , Trotta, C. R. , & Li, H. (1998). tRNA splicing. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273(21), 12685–12688. 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, S. , & Kurland, C. (1990). Codon preferences in free‐living microorganisms. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 54(2), 198–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazy, H. , Abadi, S. , Martz, E. , Chay, O. , Mayrose, I. , Pupko, T. , & Ben‐Tal, N. (2016). ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(W1), W344–W350. 10.1093/nar/gkw408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth, P. G. (2000). Pontocerebellar hypoplasia—how many types? European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 4(4), 161–162. 10.1053/ejpn.2000.0294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth, P. G. , Blennow, G. , Lenard, H.‐G. , Begeer, J. H. , Van der Kley, J. M. , Hanefeld, F. , … Valk, J. (1995). The syndrome of autosornal recessive pontocerebellar hypoplasia, microcephaly, and extrapyramidal dyskinesia (pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2): Compiled data from 10 pedigrees. Neurology, 45(2), 311–317. 10.1212/wnl.45.2.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesecker, L. G. , & Harrison, S. M. (2018). The ACMG/AMP reputable source criteria for the interpretation of sequence variants. Genetics in Medicine, 20(12), 1687 10.1038/gim.2018.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunak, S. , Engelbrecht, J. , & Knudsen, S. (1991). Prediction of human mRNA donor and acceptor sites from the DNA sequence. Journal of Molecular Biology, 220(1), 49–65. 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90380-o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde, B. S. , Namavar, Y. , Barth, P. G. , Poll‐The, B. T. , Nürnberg, G. , Becker, C. , … Baas, F. (2008). tRNA splicing endonuclease mutations cause pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Nature Genetics, 40(9), 1113 10.1038/ng.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capon, F. , Allen, M. H. , Ameen, M. , Burden, A. D. , Tillman, D. , Barker, J. N. , & Trembath, R. C. (2004). A synonymous SNP of the corneodesmosin gene leads to increased mRNA stability and demonstrates association with psoriasis across diverse ethnic groups. Human Molecular Genetics, 13(20), 2361–2368. 10.1093/hmg/ddh273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamary, J. , & Hurst, L. D. (2005). Evidence for selection on synonymous mutations affecting stability of mRNA secondary structure in mammals. Genome Biology, 6(9), R75 10.1093/hmg/ddh273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamary, J. , Parmley, J. L. , & Hurst, L. D. (2006). Hearing silence: non‐neutral evolution at synonymous sites in mammals. Nature Reviews Genetics, 7(2), 98 10.1038/nrg1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves‐Vischer, V. , Pizzolato, G.‐P. , Hanquinet, S. , Maret, A. , Bottani, A. , & Haenggeli, C.‐A. (2000). Early fatal pontocerebellar hypoplasia in premature twin sisters. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 4(4), 171–176. 10.1053/ejpn.2000.0295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. , Davydov, E. V. , Sirota, M. , & Butte, A. J. (2010). Non‐synonymous and synonymous coding SNPs show similar likelihood and effect size of human disease association. PLoS One, 5(10), e13574 10.1371/journal.pone.0013574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech, A. , Fedyunin, I. , Zhang, G. , & Ignatova, Z. (2010). Silent mutations in sight: Co‐variations in tRNA abundance as a key to unravel consequences of silent mutations. Molecular Biosystems, 6(10), 1767–1772. 10.1039/c004796c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagle, J. M. , & Weeks, D. L. (2001). Oligonucleotide‐based strategies to reduce gene expression. Differentiation, 69(2–3), 75–82. 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.690201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, F.‐O. , Hamroun, D. , Lalande, M. , Collod‐Béroud, G. , Claustres, M. , & Béroud, C. (2009). Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Research, 37(9), e67 10.1093/nar/gkp215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, K. A. , Goodenbour, J. M. , & Pan, T. (2006). Tissue‐specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS Genetics, 2(12), e221 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divina, P. , Kvitkovicova, A. , Buratti, E. , & Vorechovsky, I. (2009). Ab initio prediction of mutation‐induced cryptic splice‐site activation and exon skipping. European Journal of Human Genetics, 17(6), 759 10.1038/ejhg.2008.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, D. , Millen, K. J. , & Barkovich, A. J. (2013). Midbrain and hindbrain malformations: advances in clinical diagnosis, imaging, and genetics. The Lancet Neurology, 12(4), 381–393. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70024-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilzadeh‐Gharehdaghi, E. , Razmara, E. , Bitaraf, A. , Mahmoudi, M. , & Garshasbi, M. (2019). S3440P substitution in C‐terminal region of human reelin dramatically impairs secretion of reelin from HEK 293T cells. Cellular and Molecular Biology, 65(6), 12–16. 10.14715/cmb/2019.65.6.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattahi, Z. , Beheshtian, M. , Mohseni, M. , Poustchi, H. , Sellars, E. , Nezhadi, H. , … Jamali, P. (2019). Iranome: A catalogue of genomic variations in the Iranian population. Human Mutation, 40(11), 1968–1984. 10.1002/humu.23880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattiker, A. , Gasteiger, E. , & Bairoch, A. M. (2002). ScanProsite: a reference implementation of a PROSITE scanning tool. Applied Bioinformatics, 1(2), 107–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, W. , Zhou, T. , & Wilke, C. O. (2010). A universal trend of reduced mRNA stability near the translation‐initiation site in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. PLoS Computational Biology, 6(2), e1000664 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy, A. , Lerer, I. , Cohen, R. , Kornreich, L. , Shuper, A. , Gamliel, M. , … Lossos, A. (2014). Novel EXOSC3 mutation causes complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia. Journal of Neurology, 261(11), 2165–2169. 10.1007/s00415-014-7457-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawrylycz, M. , Ng, L. , Feng, D. , Sunkin, S. , Szafer, A. , & Dang, C. (2014).The Allen brain atlasIn Kasabov N. (Eds.), Springer handbook of bio‐/neuroinformatics. Springer handbooks. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, R. C. , Simhadri, V. L. , Iandoli, M. , Sauna, Z. E. , & Kimchi‐Sarfaty, C. (2014). Exposing synonymous mutations. Trends in Genetics, 30(7), 308–321. 10.1016/j.tig.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemura, T. (1985). Codon usage and tRNA content in unicellular and multicellular organisms. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2(1), 13–34. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski, K. , & Francioli, L. (2017). The genome aggregation database (gnomAD). Boston, MA: MacArthur Lab. [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski, K. J. , Weisburd, B. , Thomas, B. , Solomonson, M. , Ruderfer, D. M. , Kavanagh, D. , … MacArthur, D. G. (2016). The ExAC browser: Displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(D1), D840–D845. 10.1093/nar/gkw971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasher, P. R. , Namavar, Y. , van Tijn, P. , Fluiter, K. , Sizarov, A. , Kamermans, M. , … Baas, F. (2011). Impairment of the tRNA‐splicing endonuclease subunit 54 (tsen54) gene causes neurological abnormalities and larval death in zebrafish models of pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Human Molecular Genetics, 20(8), 1574–1584. 10.1093/hmg/ddr034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimchi‐Sarfaty, C. , Oh, J. M. , Kim, I.‐W. , Sauna, Z. E. , Calcagno, A. M. , Ambudkar, S. V. , & Gottesman, M. M. (2007). A" silent" polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science, 315(5811), 525–528. 10.1126/science.1135308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner, Y. , & Kotlar, D. (2005). Codon bias as a factor in regulating expression via translation rate in the human genome. Gene, 345(1), 127–138. 10.1016/j.gene.2004.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Handsaker, B. , Wysoker, A. , Fennell, T. , Ruan, J. , Homer, N. , … Durbin, R. (2009). 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics, 25(16), 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin, F. E. , Mansfield, R. E. , Vaz, P. M. , McGrath, A. P. , Setiyaputra, S. , Gamsjaeger, R. , … Mackay, J. P. (2009). The zinc fingers of the SR‐like protein ZRANB2 are single‐stranded RNA‐binding domains that recognize 5′ splice site‐like sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(14), 5581–5586. 10.1073/pnas.0802466106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandrini, A. , Palmeri, S. , Villanova, M. , Parrotta, E. , Sicurelli, F. , Amato, D. , … Guazzi, G. C. (1997). A syndrome of autosomal recessive pontocerebellar hypoplasia with white matter abnormalities and protracted course in two brothers. Brain and Development, 19(3), 209–211. 10.1016/s0387-7604(96)00563-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraş‐Genç, H. , Uyur‐Yalçın, E. , Rosti, R. Ö. , Gleeson, J. G. , & Kara, B. (2015). TSEN54 gene‐related pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2 presenting with exaggerated startle response: report of two cases in a family. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 57(3), 286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham, N. R. , & Zuker, M. (2008). UNAFold In Keith J. M. (Ed.), Bioinformatics. Methods in molecular biology (Vol. 453(1), pp. 3–31). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 10.1007/978-1-60327-429-6_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Men, A. E. , Wilson, P. , Siemering, K. , & Forrest, S. (2008). Sanger DNA sequencing In Janitz M. (Ed.), Next generation genome sequencing: Towards personalized medicine. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley‐VCH; 10.1002/9783527625130.ch1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima, H. , Suzuki, H. , Doi, M. , Miyazaki, M. , Watanabe, S. , Matsumoto, T. , … Kosaki, K. (2019). Evaluation of Face2Gene using facial images of patients with congenital dysmorphic syndromes recruited in Japan. Journal of Human Genetics, 64(8), 789–794. 10.1038/s10038-019-0619-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najmabadi, H. , Hu, H. , Garshasbi, M. , Zemojtel, T. , Abedini, S. S. , Chen, W. , … Ropers, H. H. (2011). Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature, 478(7367), 57 10.1038/nature10423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namavar, Y. , Barth, P. G. , & Baas, F. (2011). Classification, diagnosis and potential mechanisms in pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 6(1), 50 10.1038/nature10423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namavar, Y. , Barth, P. G. , Baas, F. , & Poll‐The, B. T. (2011). Reply: Mutations of TSEN and CASK genes are prevalent in pontocerebellar hypoplasias type 2 and 4. Brain, 135(1), e200 10.1093/brain/awr108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namavar, Y. , Barth, P. G. , Kasher, P. R. , Van Ruissen, F. , Brockmann, K. , Bernert, G. , … Poll‐The, B. T. (2010). Clinical, neuroradiological and genetic findings in pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Brain, 134(1), 143–156. 10.1093/brain/awq287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namavar, Y. , Chitayat, D. , Barth, P. G. , Van Ruissen, F. , De Wissel, M. B. , Poll‐The, B. T. , … Baas, F. (2011). TSEN54 mutations cause pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 5. European Journal of Human Genetics, 19(6), 724 10.1038/ejhg.2011.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namavar, Y. , Eggens, V. R. , Barth, P. G. , & Baas, F. (2016). TSEN54‐related pontocerebellar hypoplasia In Adam M. P., Ardinger H. H., Pagon R. A., Wallace S. E., Bean L. J., Karen S., & Amemiya A. (Eds.), GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M. S. , Becker, L. E. , Toi, A. , Armstrong, D. L. , & Chitayat, D. (2006). Severe, fetal‐onset form of olivopontocerebellar hypoplasia in three sibs: PCH type 5? American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 140(6), 594–603. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paushkin, S. V. , Patel, M. , Furia, B. S. , Peltz, S. W. , & Trotta, C. R. (2004). Identification of a human endonuclease complex reveals a link between tRNA splicing and pre‐mRNA 3′ end formation. Cell, 117(3), 311–321. 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00342-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piva, F. , Giulietti, M. , Burini, A. B. , & Principato, G. (2012). SpliceAid 2: A database of human splicing factors expression data and RNA target motifs. Human Mutation, 33(1), 81–85. 10.1002/humu.21609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M. , Lilley, R. , Little, S. , Emtage, J. , Yarranton, G. , Stephens, P. , … Humphreys, G. (1984). Codon usage can affect efficiency of translation of genes in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Research, 12(17), 6663–6671. 10.1002/humu.21609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabarinathan, R. , Tafer, H. , Seemann, S. E. , Hofacker, I. L. , Stadler, P. F. , & Gorodkin, J. (2013). The RNAsnp web server: predicting SNP effects on local RNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Research, 41(W1), W475–W479. 10.1093/nar/gkt291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander, I. M. , Chaney, J. L. , & Clark, P. L. (2014). Expanding Anfinsen’s principle: Contributions of synonymous codon selection to rational protein design. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 136(3), 858–861. 10.1021/ja411302m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauna, Z. E. , & Kimchi‐Sarfaty, C. (2011). Understanding the contribution of synonymous mutations to human disease. Nature Reviews Genetics, 12(10), 683 10.1038/nrg3051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, P. M. , Cowe, E. , Higgins, D. G. , Shields, D. C. , Wolfe, K. H. , & Wright, F. (1988). Codon usage patterns in Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Drosophila melanogaster and Homo sapiens; a review of the considerable within‐species diversity. Nucleic Acids Research, 16(17), 8207–8211. 10.1093/nar/16.17.8207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling, A. C. , Stern, D. , Beaton, A. , Rhem, E. J. , Laverty, T. , Mozden, N. , … Rubin, G. M. (1999). The Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project gene disruption project: Single P‐element insertions mutating 25% of vital Drosophila genes. Genetics, 153(1), 135–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuller, T. , Waldman, Y. Y. , Kupiec, M. , & Ruppin, E. (2010). Translation efficiency is determined by both codon bias and folding energy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(8), 3645–3650. 10.1073/pnas.0909910107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valayannopoulos, V. , Michot, C. , Rodriguez, D. , Hubert, L. , Saillour, Y. , Labrune, P. , … de Lonlay, P. (2011). Mutations of TSEN and CASK genes are prevalent in pontocerebellar hypoplasias type 2 and 4. Brain, 135(1), e199 10.1093/brain/awr108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xayaphoummine, A. , Bucher, T. , & Isambert, H. (2005). Kinefold web server for RNA/DNA folding path and structure prediction including pseudoknots and knots. Nucleic Acids Research, 33(2), 605–610. 10.1093/nar/gki447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, S. , Calvin, K. , & Li, H. (2006). RNA Recognition and cleavage by a splicing endonuclease. Science, 312(5775), 906 10.1126/science.1126629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. , Robinson, P. N. , & Wang, K. (2015). Phenolyzer: phenotype‐based prioritization of candidate genes for human diseases. Nature Methods, 12(9), 841–843. 10.1038/nmeth.3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G. , Hubalewska, M. , & Ignatova, Z. (2009). Transient ribosomal attenuation coordinates protein synthesis and co‐translational folding. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 16(3), 274 10.1038/nsmb.1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. , Dang, Y. , Zhou, M. , Li, L. , Yu, C.‐H. , Fu, J. , … Liu, Y. I. (2016). Codon usage is an important determinant of gene expression levels largely through its effects on transcription. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(41), 6117–6125. 10.1073/pnas.1606724113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker, M. (2003). Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Research, 31(13), 3406–3415. 10.1073/pnas.1606724113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Fig S2

Table S1

Method S1