ABTRACT

tRNA-derived fragments or tRFs were long considered merely degradation intermediates of full-length tRNAs; however, emerging research is highlighting unanticipated new and highly distinct functions in epigenetic control, metabolism, immune activity and stem cell fate commitment. Importantly, recent studies suggest that RNA epitranscriptomic modifications may provide an additional regulatory layer that dynamically directs tRF activity in stem and cancer cells. In this review, we explore current work illustrating unanticipated roles of tRFs in mammalian stem cells with a focus on the impact of post-transcriptional RNA modifications for the biogenesis and function of this growing class of small noncoding RNAs.

KEYWORDS: tRNA fragments, RNA modifications, RNA epitranscriptomics, translation control, stem cells, development, hematopoiesis, pseudouridine, 5-methylcytosine

Introduction

Recent advances in high-throughput RNA sequencing methods and comprehensive analysis of the small RNA compartment [1–4] have revealed myriad evolutionarily conserved non-coding (nc) RNA populations that are derived from various RNA species such as ribosomal RNA [5], messenger RNA [6], vault RNA [7], Y RNA [8] and transfer RNA (tRNA), also referred to as tRNA fragments (tRFs or tsRNAs) [9–14]. Although tRNA cleavage events were recognized in the body fluid of cancer patients already as early as the late 1970s [15,16], the functional potential of these tRNA processing intermediates has remained overlooked until recently. Intriguingly, emerging findings suggest that specific tRF subsets may harbour unanticipated biological activity and dynamically impact genetic information in mammalian cells. Taken together these results have sparked new interest into this expanding area of tRNA research.

tRF classification is based on their original location on the corresponding tRNA isoacceptor in three major categories: 5ʹ-derived tRFs (5ʹ-tRF), 3ʹ-derived tRFs (3ʹ-tRF) and internally derived tRFs (i-tRF) [17,18]. In addition, tRFs can be further divided in constitutive (steady-state) and stress-induced fragments, which are characterized by heterogeneous sequence and length distribution [13]. It has been shown that short 15–22 nucleotide (nt) long fragments are constitutively produced across several tissues and cell lines even in homeostatic conditions [19], whereas longer 31–40 nt tRNA-halves are predominantly generated in response to various stressors [3,4,20]. Notably, only a minor portion of mature cytoplasmic tRNAs (~1%) is processed during stress [4], strongly suggesting that stress-induced tRNA cleavage is unlikely to deplete cellular tRNA pools.

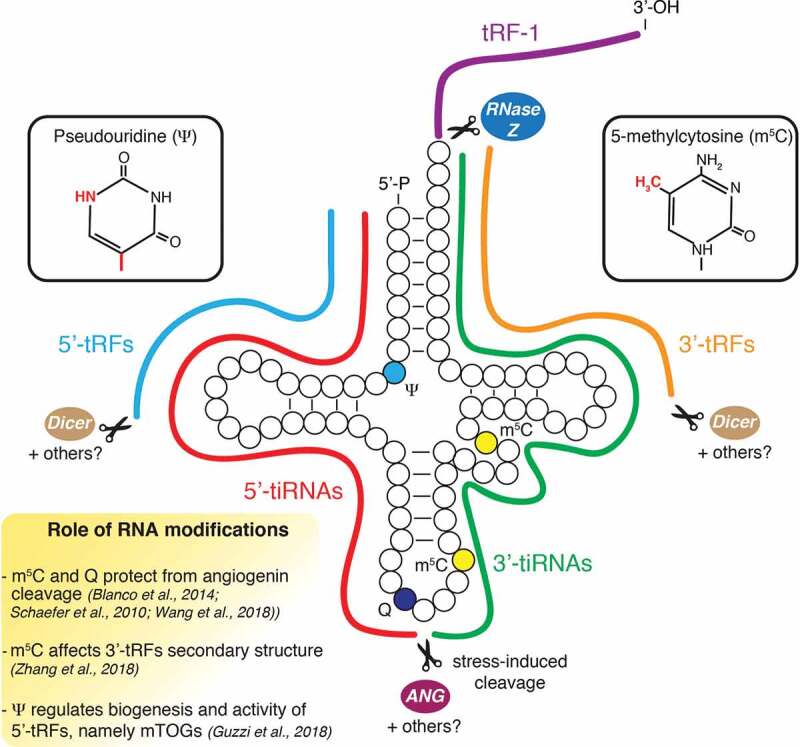

A breakthrough came with the identification of the vertebrate-specific RNase superfamily member angiogenin, which is responsible for the production of stress-induced tRNA-derived fragments (tiRNAs) in mammalian cells [1,4]. Furthermore, studies using RNA methyltransferases knockout cells and mouse models revealed that the ability of angiogenin to cleave tRNAs was modulated by the presence of 5-methylcytosine (m5C) base modification [21,22], unravelling a critical role of RNA modifications in tRF biology. This additional regulatory layer of tRF biogenesis was further supported by findings that queuosine modification at position 34 modulated angiogenin-dependent cleavage [23]. Over 90 different types of base modifications decorate tRNAs in humans with an average of 11–13 modifications per molecule, which provides plenty of room for post-transcriptional regulation of tRFs [24]. The importance of RNA modifications for tRF biogenesis and function has increasingly been appreciated and was recently reviewed [25]. Additionally, an important functional overlap with the miRNA pathway was proposed with findings that Dicer might be involved in the accumulation of 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-tRFs [9,26]. However, the role of Dicer in tRF biogenesis may be limited, as its depletion does not globally impact tRF levels in multiple model organisms [19,27,28]. Furthermore, other endonucleases have been shown to target tRNAs in mammalian cells. For example, the RNase Z/ELAC2 was involved in pre-tRNAs fragmentation to generate a specific class of 3ʹ-derived tRFs (tRF-1) with a unique sequence not present in mature tRNAs [13]. Another study illustrated that RNase L activation in response to viral infection led to site-specific tRNA cleavage and translational repression in human cancer cells, although whether the resulting tRFs harboured biological activity was not explored [29]. Given the complexity of the processing pathways involved in tRNA fragmentation, dissecting how tRF biogenesis undergoes cell context-specific regulation represents one of the major current challenges in tRF biology (Fig. 1 and Outstanding Questions).

Figure 1.

Regulation of tRF biogenesis in stem cells. Schematic illustrates tRF biogenesis and epitranscriptomic modifications. Dicer and possibly other ribonucleases not yet identified have been proposed to modulate the production of 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-tRFs. Angiogenin (ANG) induces cleavage of tRNAs in the anticodon loop in response to stress conditions to promote the accumulation of 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-tiRNAs. 5-methylcytosine (m5C) and queuosine (Q) modulate angiogenin activity and may impact 3ʹ-tRF secondary structure. Pseudouridine (ψ) is necessary for the biogenesis and activity of a specific class of 5ʹ-tRFs (mTOGs) in stem cells.

Recent research on the role of tRFs has highlighted important functions in a variety of molecular processes including mRNA stabilization [30], regulation of cap-dependent and cap-independent translation [4,20,31–37], miRNA-mediated silencing [2,26,38], mRNA localization in stress granules [39] and suppression of transposable elements (TEs) [40]. Moreover, tRF production is also dynamically regulated during fundamental cellular processes involved in development and commonly dysregulated in cancer, thus increasing the functional complexity of these small RNAs [34,41]. These findings implicate tRFs as integral molecular components of gene expression programs that may contribute to direct lineage-specific commitment. This raises an important question: what is the underlying regulatory potential of tRFs in stem cells? In this review, we will summarize recent research highlighting the physiological importance of tRFs in germline, embryonic and somatic stem cells with a focus on the impact of RNA epitranscriptomic modifications on the biogenesis and function of specific tRF subsets during mammalian development.

tRFs in epigenetic regulation and germline-mediated intergenerational inheritance

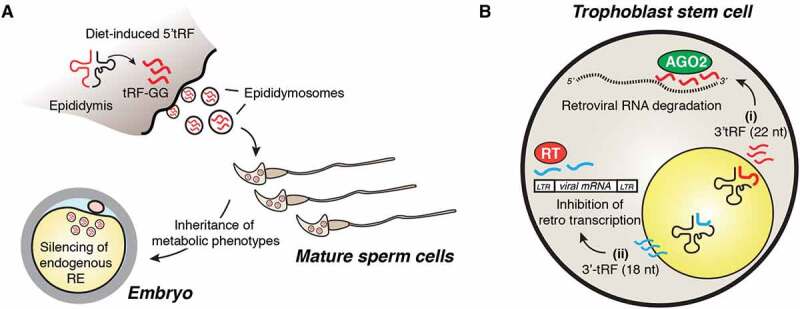

Several lines of evidence indicate a function for tRFs in gene expression control during early embryonic development. Seminal work demonstrated that epigenetic DNA modifications alone could not explain male contribution to intergenerational inheritance traits and indicated that RNA may be central to this process [42]. Additional studies further involved sperm tRFs in promoting intergenerational transmission of specific metabolic phenotypes in mice [43,44]. Authors showed that mature sperm cells were characterized by an abundant 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-tRF payload that was altered in response to environmental cues such as proteinrestriction and high-fat diet (HFD) regimens. Indeed, sperm 5ʹ-tRF levels were significantly different in mice fed with a low-protein diet compared to normal-diet controls and may contribute to transmission of metabolic phenotypes through inhibition of TE [44]. Unexpectedly, low levels of tRFs were detected in immature sperm cells purified from mice testicles. On the basis of this observation, it was subsequently shown that sperm cells were able to acquire their tRF payload after testicular maturation through fusion of transport vesicles enriched in 5ʹ-tRFs produced in the epididymis (epididymosomes) [45]. This compellingly suggested that tRF pools might be transferred between different cell types to pass higher-order organismal information, such as dietary protein restrictions, through the germline (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

tRF function in epigenetic silencing during early embryogenesis. (A) tRFs mediate intergenerational transmission of metabolic phenotypes. 5ʹ-tRFs including tRF-GG, exhibit a two-three fold increase in somatic epididymis cells upon dietary restriction and are transferred to maturing sperm cells. This process has been proposed to repress endogenous retroelements (RE) and pass paternal inherited information during embryonic development. (B) Murine trophoblastic stem cells produce 3ʹ-tRFs that inhibit the replication of endogenous retroviruses via two distinct mechanisms: (i) putative model illustrating 22 nt 3ʹ-tRFs inducing post-transcriptional silencing of retroviral RNA possibly via association with the canonical miRNA-effector protein AGO2. (ii) 18 nt 3ʹ-tRFs interfere with reverse transcription of viral RNAs to restrict transposon mobility.

Additional evidence illustrated that a significant proportion (~11.5%) of mature sperm 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-tRFs were differentially produced in mice kept on a HFD compared to a normal diet [43]. Remarkably, tRF-enriched small RNA fractions derived from HFD sperm were sufficient to induce glucose intolerance in the offspring when transferred to normal zygotes [43]. Despite these findings, the exact mechanisms that account for tRF-mediated intergenerational inheritance remain to be fully elucidated. Interestingly, zygotic injection of synthetic tRFs failed to recapitulate HFD-driven metabolic disorder phenotypes in the offspring [43], further indicating that the stability and activity of sperm-derived endogenous tRF pools might rely on post-transcriptional modifications [46]. This idea was further supported by findings that the levels of m5C and N2-methylguanosine (m2G) base modifications were significantly elevated within sperm small RNAs (30–40 nt) derived from HFD fed mice [43,46]. These studies suggest that distinct RNA modifications may impact the biogenesis and function of sperm-derived tRFs, thereby contributing to the transmission of metabolic phenotypes in the offspring. Consistently, subsequent results indicated that HFD induced the expression of the RNA methyltransferase Dnmt2/Trdmt1 hereafter referred to as Dnmt2, in the epididymis [46]. Critically, it was previously reported that Dnmt2-dependent m5C at position 38 protected specific tRNAs from angiogenin-mediated cleavage [22,47]. Thus, it is possible that HFD-dependent induction of Dnmt2 levels may be required to fine-tune sperm tRF cargos and promote inheritance of paternal phenotypic traits. Accordingly, genetic depletion of Dnmt2 in mouse models altered tRF profiles in sperm cells and prevented the transmission of paternally acquired metabolic disorders [46]. This study further revealed that Dnmt2-mediated m5C affected the secondary structure and biological properties of abundant 3ʹ-tRFs upon transfection in cell lines [46], although the exact contribution of m5C for tRF-mediated paternal inheritance was not fully delineated. Similarly, a recent study in humans showed that i-tRF levels in sperm cells from healthy donors were dynamically modulated in response to acute diet intervention and were positively associated with increased sperm motility [48]. Hence, further studies will be required to qualitatively assess the function of tRFs during the early developmental stages and their contribution to the transmission of paternally acquired metabolic traits.

In addition to a putative role in paternal inheritance, tRFs have been shown to strongly inhibit endogenous TEs [40]. Interestingly, extra-embryonic trophoblast and embryonic stem cells (ESC) with de-repressed chromatin were characterized by remarkably high levels of 3ʹ-tRFs, thus suggesting a putative role for these small ncRNAs in controlling transposon mobility [40]. Two possible mechanisms have been proposed for tRF-mediated retrotransposon silencing: (i) short 18 nt 3ʹ-tRFs interfere with reverse transcription by targeting the reverse transcriptase primer binding sites; (ii) 22 nt 3ʹ-tRFs induce post-transcriptional silencing of viral RNA [40] possibly via association with Argonaute 2 (AGO2) as previously proposed [28] (Fig. 2B). However, direct evidence for tRF-driven AGO2 silencing is still lacking. Novel mechanistic insights into how tRFs may control TE were recently revealed in a new study. Authors found that a specific 5ʹ-tRF derived from tRNA-Gly-GCC, tRF-GG, regulated the expression of the endogenous retroelement MERVL in mouse ESCs (mESC) and in pre-implantation embryos [49]. Strikingly, tRF-GG promoted the biogenesis of a wide range of ncRNAs including U7 snRNA, which contributed to the stabilization of histone mRNAs through binding to a histone stem loop (HSL) located in the 3ʹ-untranslated region (UTR) of these transcripts. This subsequently resulted in heterochromatin assembly associated with TE silencing in mESCs. Since tRF-GG was previously highlighted as one of the most differentially produced fragments (two-three fold increase) in sperm cells upon protein restriction, it is possible that a similar mechanism may also be involved in the parental transmission of metabolic phenotypes [44]. Together, these findings indicate that tRFs may contribute to genomic stability during the earliest steps of development.

Developmentally regulated tRF subsets impact embryonic stem cell function

Novel insights into the role of tRFs in embryogenesis were recently obtained using human ESCs (hESCs) [34]. This work unveiled a new molecular circuitry orchestrated by a pool of short 5ʹ-tRFs, denoted mini TOGs (mTOGs), that were characterized by a distinct 5ʹ terminal oligoguanine (TOG) motif shared by a group of tRNA isoacceptors including tRNA-Ala, tRNA-Cys and tRNA-Val [34]. We discovered an essential role for the stem cell-enriched pseudouridine synthase, PUS7, in the biogenesis and function of mTOGs in hESCs. Importantly, PUS7 mediated the pseudouridylation (ψ) of a critical uridine (U) at position 8 within the mTOG sequence and this was required for translation repression through selective binding and inhibition of the polyadenylate binding protein 1 (PABPC1), an integral component of the 5ʹ cap-translation initiation complex. Notably, PUS7-depleted hESCs were characterized by dramatic growth and differentiation defects that significantly impaired germ layer specification in the absence of changes in tRNA abundance. Findings that PUS7 and mTOGs were rapidly downregulated during embryonic differentiation further suggest that the post-transcriptional regulatory layer governed by tRFs and ψ may provide a physiological means to spatiotemporally control gene expression during development. As such, more work will be necessary to determine the underlying developmental signals and molecular mechanisms that direct PUS7-mediated ψ and mTOG repressive function in embryonic development. Further evidence that tRFs may contribute to lineage commitment of mouse ESCs (mESCs) was reported in a recent study [50]. Specifically, it was shown that the abundance of defined 5ʹ-tRFs was differentially modulated in mESCs undergoing retinoic acid (RA)-induced differentiation and this was uncoupled from parental tRNA isoacceptors gene copy number. Additionally, authors showed that only a small percentage of differentiation-induced tRFs were dependent on angiogenin processing [50]. This evidence suggested that additional RNases, other than angiogenin, might become activated in response to differentiation-promoting signals to modulate tRF abundance. Importantly, developmentally controlled 5ʹ-tRFs were shown to repress the expression of key pluripotency factors including c-Myc and Klf4. Specifically, authors found that the effect on c-Myc levels was in part mediated through the direct association between a 35 nt 5ʹ-tRF (tsGlnCTG) and the RNA binding protein, Igf2bp1. These data preliminarily implicate the differentiation-induced tsGlnCTG in promoting c-Myc degradation by sequestering Igf2bp1, a protein required to prevent c-Myc endonucleolytic cleavage [51]. Notably, novel putative interactions between tRFs and several proteins were also reported in this study [50]. This may suggest that multiple layers of tRF regulation could be necessary to determine the phenotypic changes observed in embryogenesis. Building on evidence that RNA modifications affect tRF interactomes [34], more efforts will be necessary to delineate how the presence of individual chemical marks impacts the assembly and function of tRF-protein complexes and comprehensively assess the biological implications of these interactions for pluripotency and fate commitment.

tRFs as novel regulators of haematopoietic stem cell fate and immune response

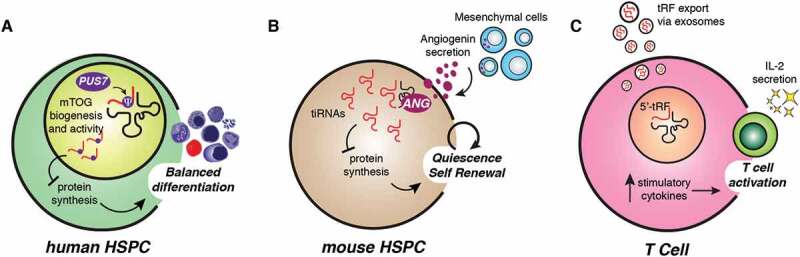

There is a growing appreciation that tRFs may share important regulatory functions in adult haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) [34,52,53], multipotent cells endowed with self-renewal potential that produce all blood lineages throughout life [54,55]. Remarkably, high levels of the pseudouridine ‘writer’ PUS7 in human HSPCs were shown to control protein synthesis and haematopoietic differentiation through activation of mTOGs [34]. Specifically, PUS7 depletion resulted in low mTOG levels that were accompanied by abnormal increases of global translation rates in HSPCs. These molecular dysfunctions led to impaired haematopoietic differentiation in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 3A). Significantly, we found that PUS7 was frequently altered in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), a collection of clonal haematological disorders associated with HSPC dysfunction and high risk of leukaemia transformation [56,57]. Based on previous studies illustrating that HSPCs are highly sensitive to perturbations of protein synthesis [58–60], additional work using in vivo models and patient-derived primary cells will be necessary to explore the potentially broad clinical implications of impairments in PUS7 and mTOG in leukaemogenesis. The contribution of tRNA modifications for mammalian haematopoiesis is further supported by findings that Dnmt2 knockout (Dnmt2-/-) mice were characterized by HSPC defects [53]. Complete loss of Dnmt2-dependent m5C activity on its substrates tRNA-Asp, tRNA-Val and tRNA-Gly was concomitant to a significant increase of tRF levels in the bone marrow (BM) of these mice, which was in line with previous research performed on Dnmt2 mutant Drosophila [22]. Interestingly, Dnmt2-depletion in mice did not globally perturb protein synthesis rates but rather affected specific mRNAs through reduced translation fidelity caused by loss of tRNA-Asp methylation [53]. While this suggested that most of the phenotypic effects in Dnmt2-/- mice were likely the result of translational changes, the potential impact of elevated tRF levels due to Dnmt2 loss in haematopoiesis remains completely unexplored. Thus, additional work will be necessary to unambiguously differentiate the contribution of altered tRF abundance in stem cells from the complex phenotypes observed upon depletion of Dnmt2 and other tRNA modifying enzymes.

Figure 3.

tRFs regulate self-renewal, differentiation and activation of haematopoietic cells. (A) Pseudouridine synthase 7 (PUS7) regulates biogenesis and activity of specific 5ʹ-tRFs, namely mTOGs. In human HSPCs, mTOGs ensure accurate protein synthesis levels and haematopoietic differentiation. Loss of PUS7 and mTOGs leads to aberrant stem cell growth and impaired multi-lineage commitment. (B) Angiogenin is released by MSCs in the bone marrow niche and accumulates in HSPCs to promote tiRNAs biogenesis, maintain low protein synthesis level and stem cell quiescence. (C) Activated T lymphocytes secrete inhibitory 5ʹ-tRF pools to enable production of co-stimulatory cytokines such as IL-2 and immune activation.

A potential role for tRFs as haematopoietic niche modulators was revealed by evidence that angiogenin differentially affected specific populations of stem and progenitor cells [52]. Initial observations indicated that angiogenin expression was different between pools of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) in close proximity to HSPCs, suggesting specialized functions of this secreted RNase in haematopoietic cells [61]. This was subsequently explored using angiogenin knockout (Ang-/-) mice that displayed abnormal expansion of long-term haematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) resulting from the angiogenin-deficient BM microenvironment. At the molecular level, angiogenin-depleted HSPCs showed significant higher global protein synthesis rates, which were modulated upon transduction of angiogenin or addition of downstream-regulated tRFs including tiRNA-Gly-GCC halves [52] (Fig. 3B). This further highlighted that angiogenin pro-regenerative effects might rely on the repressive effect of specific tiRNA on HSPC translation. This notion was in part supported by previous studies illustrating that phosphorylated 5ʹ-tiRNAs were shown to induce stress granule formation and suppress global protein synthesis in different cell types [4,20,39]. Nonetheless, additional experiments will be needed to comprehensively address the extent to which sequence specificity, 5ʹ-phosphate and RNA modifications contribute to tRF-mediated translation control in the HSPC compartment. Furthermore, Ang-/- mice were also characterized by defective proliferation of myeloid-restricted progenitor (MyePro) cells [52]. The authors showed that angiogenin impacted MyePro cell proliferation affecting ribosomal RNA (rRNA) levels without global tRF changes in these cells. These findings suggest dichotomous angiogenin-dependent mechanisms for differential control of distinct haematopoietic cell populations and highlighted a critical contribution to the stem cell niche. Interestingly, angiogenin was shown to enhance the survival and proliferation of different cell types including angiogenic, neuronal and cancer cells [62–65]. Nonetheless, how angiogenin substrate specificity is regulated within different cell types and the direct contribution of downstream tRF-dependent and tRF-independent effects on protein synthesis in stem and somatic cells remains to be fully elucidated.

Additional evidence for tRF-mediated regulation in haematopoietic cells is provided by recent work illustrating that tRFs may repress immune activation in mice [66]. Specifically, it was shown that antibody-stimulated T lymphocytes secreted extracellular vesicles (EV) significantly enriched for 5ʹ-tRFs that were different from those released in resting condition. Moreover, it was proposed that the accumulation of 5ʹ-tRFs was detrimental for T cell activation and this was possibly caused by reduced synthesis of co-stimulatory cytokines such as interleukin 2 (IL-2). The authors concluded that activated T cells preferentially eliminated inhibitory intracellular tRF cargos through EV-mediated secretion to maintain cell fitness and activity [66] (Fig. 3C). It remains unclear whether secreted tRFs are further transferred between haematopoietic cells to exchange information and modulate the immune response. Nonetheless, these studies set the basis for future work investigating the contribution of tRFs for physiological and pathological cell-to-cell communications within the haematopoietic system.

tRF-mediated protein synthesis control in skin and neuronal stem cells

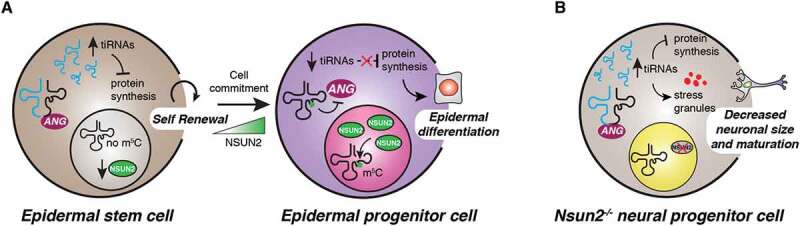

Somatic stem cells are particularly sensitive to perturbations of protein synthesis and thrive on low translational rates to maintain their undifferentiated state [58,60]. Recent studies showed that specific tRNA modifying enzymes might dynamically affect tRF production across different stem cell compartments and during development [34,41]. In addition to the roles of PUS7 and DNMT2 in accurate embryonic and haematopoietic commitment previously discussed (see above), the function of NSUN2 cytosine-C5 tRNA methyltransferase on modulating tRNA fragmentation during skin development was recently highlighted [41,67]. Specifically, it was shown that Nsun2-mediated m5C was critically required to balance stem cell self-renewal and differentiation within the epidermis [67]. In vivo studies revealed that Nsun2 expression was highly dynamic during embryogenesis and restricted to subpopulations of committed epidermal stem cells in the adult skin hair bulge [41,67]. Accordingly, skin-specific deletion of Nsun2 led to severe differentiation defects associated with increased stem cell quiescence [67]. Further research illustrated that Nsun2-deficient mouse brains were characterized by tRNA hypomethylation at position C34, C48 and C49 that favoured angiogenin-dependent endonucleolytic cleavage of selective tRNAs and subsequent accumulation of translational inhibitory and stress-inducing 5ʹ-tiRNAs [21]. Increased levels of translational inhibitory 5ʹ-tiRNAs were also observed during skin development. This effect was uncoupled from cell proliferation and was required to maintain skin stem cell homeostasis and function (Fig. 4A). These results further suggested a role for RNA modifications in tRNA fragmentation, which may drive the accumulation of tRFs in stem cells across tissues and organisms even in the absence of external stimuli [34,41,68]. This was also highlighted by studies using a skin tumour model indicating that Nsun2 deletion repressed protein synthesis to increase cancer-initiating cell self-renewal and promote tumorigenesis [41]. Additionally, rapid downregulation of Nsun2 along with dynamic and site-specific loss of m5C on distinct tRNA isoacceptors was observed upon oxidative stress [69]. These stress-induced changes selectively reshaped the tRF landscape to sustain an anabolic cellular state [69]. Future work will be required to investigate whether NSUN2 and tRFs rewire the stem cell metabolome during fate commitment and, when altered, malignant transformation.

Figure 4.

Dynamic tRNA methylation impacts tRF biogenesis and directs stem cell fate. (A) Nsun2 and Dnmt2-mediated m5C protects tRNAs from angiogenin cleavage. Low levels of NSUN2 in mouse and human epidermal stem cells lead to accumulation of tiRNAs that repress protein synthesis. Conversely, epidermal progenitors up-regulate Nsun2 to inhibit angiogenic-mediated tRNA cleavage and promote epidermal differentiation. (B) Nsun2-depletion leads to neurological disorders caused by accumulation of stress-induced tiRNAs in vivo. Nsun2-deficient neuronal cells display increased stress granules assembly, reduced size and impaired maturation. These defects are specifically rescued by angiogenin inhibition that reduces tiRNA levels in these cells.

NSUN2 is also critically required for accurate development and differentiation of murine and human neural stem cells [21,70]. For example, Nsun2-deficient mice were characterized by several neurodevelopmental defects including reduced neuronal cell size and decreased neuron maturation and synaptogenesis [21] (Fig. 4B). These phenotypes correlated with increased cellular stress, accumulation of 5ʹ-tRFs and a consequent reduction of global protein synthesis. Importantly, inhibition of angiogenin could rescue these defects, illustrating the specific effects of Nsun2 on tRF biogenesis and function in neuronal cells [21]. In humans, NSUN2 is highly expressed in early neuroepithelial stem (NES) cells, progenitors endowed with multipotent differentiation capacity towards the neural and glial lineages. Consistent with a central role in development, depletion of NSUN2 in NES cells caused delayed differentiation, possibly through a mechanism involving increased production of tRFs [70]. Accordingly, loss-of-function NSUN2 mutations have been reported in patients with microcephaly and mental retardation [71–73]. Additional studies are needed to determine the contribution of impairments in tRF epitranscriptomic modifications towards the aetiology of human neurodevelopmental diseases.

Concluding remarks

The identification of myriad tRNA-derived small RNA molecules harbouring critical roles in development and tumorigenesis has sparked new interest in tRNA research, expanding the complexity of these adaptor molecules beyond their canonical function in translation. Although tRNA fragmentation was identified in the 1970s, tRF biology only recently enjoyed a mechanistic renaissance, which raises important outstanding questions with respect to the biogenesis and molecular pathways controlled by this growing class of small noncoding RNAs (see Outstanding Questions).

Several lines of evidence indicate that different types of mammalian stem cells may be regulated by tRFs under stress and physiological conditions [68]; however, the differential effects of tRFs in stem cell compartments compared to other types of somatic cells need to be fully elucidated. Additionally, the regulatory mechanisms involved in tRF selective processing are still poorly understood. For example, stress-induced tRNA cleavage by the vertebrate-specific RNase angiogenin produces several tiRNAs involved in stemness and differentiation [21,41,52]. Yet, angiogenin is a secreted protein characterized by low sequence specificity [74], suggesting that additional regulatory signals may be necessary to direct cleavage activity within specific stem cell populations. Even less is known about the processes that control the biogenesis of shorter tRF forms across different types of cells. It has been proposed that Dicer-dependent and -independent cleavage events may contribute to 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-tRF production [9,26]. This has raised an important question: how do Dicer and other components of the microprocessor complex survey tRNA integrity? A future challenge will be to delineate the functional overlap with the miRNA and other RNA metabolic pathways to inform the basic mechanisms of tRF biogenesis.

The notion that RNA modifications may be directly involved in tRF biogenesis and function is consistent with tRNAs being heavily post-transcriptionally modified RNA molecules [24]. Several studies have shown that angiogenin-driven tRNA processing is sensitive to m5C base modifications installed by DMNT2 and NSUN2 in various cell types including primary epidermal, neuronal and haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in vivo [68]. Furthermore, it has been recently shown that queuosine modification within the wobble anticodon position of specific tRNAs significantly reduces cleavage of tRNA cognates by angiogenin, suggesting that other types of RNA modifications may regulate tRF processing in mammalian cells [23]. Findings in embryonic and haematopoietic stem cells illustrate that ψ is important for tRF biogenesis and function through a mechanism that involves fine-tuned modulation of translation initiation [34]. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that ψ, m5C and possibly other types of RNA modifications may introduce important secondary structural changes necessary for specific RNA–protein interactions that impact tRF maturation and function as recently proposed for other types of small RNAs [75,76]. Recent progress in single-molecule-sequencing along with remarkable advances in mass-spectrometry approaches to detect nucleotide chemical modifications may offer new opportunities to comprehensively assess the tRF epitranscriptomic landscape and determine the specific effects on development and disease [77–79].

Accumulating evidence indicates that dysregulation of RNA modifications may impact human diseases [80–82]. Recent studies compellingly show that cancer cells may co-opt tRFs to affect gene expression and promote tumorigenesis [30,83]. Furthermore, it has been shown that loss-of-function mutations in tRNA modifying enzymes are associated with neurological defects such as microcephaly and intellectual disability in humans [73,84,85]. Accordingly, loss of tRNA modifiers, including PUS7 and NSUN2, leads to perturbed tRF levels associated with aberrant protein synthesis rates in malignant stem cell populations of aggressive skin and haematological cancers [34,41]. These findings highlight both the explosive growth as well as its limits in understanding these new roles for tRFs, as the mechanistic basis by which tRFs govern protein synthesis in stem and cancer cells are still not fully understood. Balanced protein synthesis is central to cellular processes involved in development and tumorigenesis [86]. Future efforts using genome-wide sequencing methods such as ribosome profiling [87] combined with quantitative mass spectrometry [88] will be necessary to decipher the translation-based programs that are driven by tRFs as opposed to those caused by dysfunctional parental isoacceptor tRNA pools in normal and malignant cells [89,90].

Two interesting studies indicate that tRFs may also be transferred between different cell types during development and in adult tissues [44,45]. As such, it is possible that tRFs may thusly exchange information between different cell populations within the stem cell niche and the cancer microenvironment. Additional intriguing developments illustrate that other species of ncRNAs are fragmented into functional small ncRNAs that can also be secreted into extracellular vesicles and may have a role in cancer progression and stem cell differentiation [91]. Interestingly, tRF levels are associated with disease progression in some cancer types [92]; however, the therapeutic potential of these small RNAs remains mostly unexplored. Their clinical promise may be borne out by recent progress with miRNA-based therapeutics [93,94]. Ultimately, as research is unveiling unanticipated facets of gene expression regulated by tRFs in stem cells, this will provide future opportunities to investigate the contribution of this growing class of small noncoding RNAs in regenerative medicine and cancer biology.

Outstanding questions

What is the tRFome that regulates stemness and cell fate differentiation? More broadly, among more than ~20,000 tRFs identified thus far [95], how many are functional and contribute to stem cell regulation?

How is tRF biogenesis controlled? What drives the specificity of angiogenin and other ribonuclease complexes towards distinct isoacceptor tRNAs in different types of stem cells?

Which upstream signalling pathways govern tRF activity?

How do RNA epitranscriptomic modifications impact tRF-protein and tRF-RNA interactions necessary for modulating stem cell function? Are tRF modifications dynamically regulated?

Do tRFs contribute to cell-to-cell communication within the stem cell niche?

Can tRFs be employed as novel RNA therapeutic tools or predictive, prognostic biomarkers in disease?

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to those researchers whose work greatly contributed to the field but were not cited owing to space limitations. We thank all the members of the Bellodi laboratory for helpful comments, Andrew Hsieh for critical reading of this review and Kimhouy Tong for editing the manuscript. C.B is supported by the Swedish Foundations’ Starting Grant (SFSG) (C.B.), StemTherapy (C.B.), Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) (C.B.) and Swedish Cancer Society (Cancerfonden) (C.B.). C.B. is a Ragnar Söderberg Fellow in Medicine and Cancerfonden Young Investigator.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Cancerfonden [190320PJ]; Cancerfonden [190321US]; Familjen Erling-Perssons Stiftelse [2017-2022]; Ragnar Söderbergs stiftelse [2015-2020]; Vetenskapsrådet [2019-00982].

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- [1].Fu HJ, Feng JJ, Liu Q, et al. Stress induces tRNA cleavage by angiogenin in mammalian cells. Febs Lett. 2009;583:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Haussecker D, Huang Y, Lau A, et al. Human tRNA-derived small RNAs in the global regulation of RNA silencing. Rna. 2010;16:673–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Thompson DM, Lu C, Green PJ, et al. tRNA cleavage is a conserved response to oxidative stress in eukaryotes. RNA. 2008;14:2095–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yamasaki S, Ivanov P, Hu GF, et al. Angiogenin cleaves tRNA and promotes stress-induced translational repression. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thompson DM, Parker R.. The RNase Rny1p cleaves tRNAs and promotes cell death during oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pircher A, Bakowska-Zywicka K, Schneider L, et al. An mRNA-derived noncoding RNA targets and regulates the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2014;54:147–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Persson H, Kvist A, Vallon-Christersson J, et al. The non-coding RNA of the multidrug resistance-linked vault particle encodes multiple regulatory small RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1268–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Meiri E, Levy A, Benjamin H, et al. Discovery of microRNAs and other small RNAs in solid tumors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6234–6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cole C, Sobala A, Lu C, et al. Filtering of deep sequencing data reveals the existence of abundant Dicer-dependent small RNAs derived from tRNAs. Rna. 2009;15:2147–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Haiser HJ, Karginov FV, Hannon GJ, et al. Developmentally regulated cleavage of tRNAs in the bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:732–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hsieh LC, Lin SI, Kuo HF, et al. Abundance of tRNA-derived small RNAs in phosphate-starved Arabidopsis roots. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5:537–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lee SR, Collins K. Starvation-induced cleavage of the tRNA anticodon loop in Tetrahymena thermophila. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42744–42749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee YS, Shibata Y, Malhotra A, et al. A novel class of small RNAs: tRNA-derived RNA fragments (tRFs). Gene Dev. 2009;23:2639–2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li Y, Luo J, Zhou H, et al. Stress-induced tRNA-derived RNAs: a novel class of small RNAs in the primitive eukaryote Giardia lamblia. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6048–6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Borek E, Baliga BS, Gehrke CW, et al. High turnover rate of transfer RNA in tumor tissue. Cancer Res. 1977;37:3362–3366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Speer J, Gehrke CW, Kuo KC, et al. tRNA breakdown products as markers for cancer. Cancer. 1979;44:2120–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kumar P, Mudunuri SB, Anaya J, et al. tRFdb: a database for transfer RNA fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D141–D145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Loher P, Telonis AG, Rigoutsos I. MINTmap: fast and exhaustive profiling of nuclear and mitochondrial tRNA fragments from short RNA-seq data. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kumar P, Anaya J, Mudunuri SB, et al. Meta-analysis of tRNA derived RNA fragments reveals that they are evolutionarily conserved and associate with AGO proteins to recognize specific RNA targets. Bmc Biol. 2014;12:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, et al. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011;43:613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Blanco S, Dietmann S, Flores JV, et al. Aberrant methylation of tRNAs links cellular stress to neuro-developmental disorders. Embo J. 2014;33:2020–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schaefer M, Pollex T, Hanna K, et al. RNA methylation by Dnmt2 protects transfer RNAs against stress-induced cleavage. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1590–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang X, Matuszek Z, Huang Y, et al. Queuosine modification protects cognate tRNAs against ribonuclease cleavage. RNA. 2018;24:1305–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D303–D307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lyons SM, Fay MM, Ivanov P. The role of RNA modifications in the regulation of tRNA cleavage. Febs Lett. 2018;592:2828–2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Maute RL, Schneider C, Sumazin P, et al. tRNA-derived microRNA modulates proliferation and the DNA damage response and is down-regulated in B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1404–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Langenberger D, Cakir MV, Hoffmann S, et al. Dicer-processed small RNAs: rules and exceptions. J Exp Zool Part B. 2013;320b:35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li ZH, Ender C, Meister G, et al. Extensive terminal and asymmetric processing of small RNAs from rRNAs, snoRNAs, snRNAs, and tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6787–6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Donovan J, Rath S, Kolet-Mandrikov D, et al. Rapid RNase L-driven arrest of protein synthesis in the dsRNA response without degradation of translation machinery. Rna. 2017;23:1660–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Goodarzi H, Liu X, Nguyen HC, et al. Endogenous tRNA-derived fragments suppress breast cancer progression via YBX1 displacement. Cell. 2015;161:790–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fricker R, Brogli R, Luidalepp H, et al. A tRNA half modulates translation as stress response in Trypanosoma brucei. Nat Commun. 2019;10:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gebetsberger J, Wyss L, Mleczko AM, et al. A tRNA-derived fragment competes with mRNA for ribosome binding and regulates translation during stress. Rna Biol. 2017;14:1364–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gebetsberger J, Zywicki M, Kunzi A, et al. tRNA-derived fragments target the ribosome and function as regulatory non-coding RNA in Haloferax volcanii. Archaea. 2012;2012:260909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guzzi N, Ciesla M, Ngoc PCT, et al. Pseudouridylation of tRNA-derived fragments steers translational control in stem cells. Cell. 2018;173:1204–1216 e1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kim HK, Fuchs G, Wang S, et al. A transfer-RNA-derived small RNA regulates ribosome biogenesis. Nature. 2017;552:57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kim HK, Xu J, Chu K, et al. A tRNA-derived small RNA regulates ribosomal protein S28 protein levels after translation initiation in humans and mice. Cell Rep. 2019;29:3816–3824 e3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sobala A, Hutvagner G. Small RNAs derived from the 5 end of tRNA can inhibit protein translation in human cells. Rna Biol. 2013;10:553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Martinez G, Choudury SG, Slotkin RK. tRNA-derived small RNAs target transposable element transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:5142–5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Emara MM, Ivanov P, Hickman T, et al. Angiogenin-induced tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs promote stress-induced stress granule assembly. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10959–10968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schorn AJ, Gutbrod MJ, LeBlanc C, et al. LTR-retrotransposon control by tRNA-derived small RNAs. Cell. 2017;170:61–71 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Blanco S, Bandiera R, Popis M, et al. Stem cell function and stress response are controlled by protein synthesis. Nature. 2016;534:335–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Shea JM, Serra RW, Carone BR, et al. Genetic and epigenetic variation, but not diet, shape the sperm methylome. Dev Cell. 2015;35:750–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chen Q, Yan M, Cao Z, et al. Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder. Science. 2016;351:397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sharma U, Conine CC, Shea JM, et al. Biogenesis and function of tRNA fragments during sperm maturation and fertilization in mammals. Science. 2016;351:391–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Sharma U, Sun F, Conine CC, et al. Small RNAs are trafficked from the epididymis to developing mammalian sperm. Dev Cell. 2018;46:481–494 e486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhang Y, Zhang X, Shi J, et al. Dnmt2 mediates intergenerational transmission of paternally acquired metabolic disorders through sperm small non-coding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:535–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Goll MG, Kirpekar F, Maggert KA, et al. Methylation of tRNAAsp by the DNA methyltransferase homolog Dnmt2. Science. 2006;311:395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Natt D, Kugelberg U, Casas E, et al. Human sperm displays rapid responses to diet. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Boskovic A, Bing XY, Kaymak E, et al. Control of noncoding RNA production and histone levels by a 5ʹ tRNA fragment. Genes Dev. 2020;34:118–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Krishna S, Yim DGR, Lakshmanan V, et al. Dynamic expression of tRNA-derived small RNAs define cellular states. Embo Rep. 2019;20::e47789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Weidensdorfer D, Stohr N, Baude A, et al. Control of c-myc mRNA stability by IGF2BP1-associated cytoplasmic RNPs. Rna. 2009;15:104–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Goncalves KA, Silberstein L, Li SP, et al. Angiogenin promotes hematopoietic regeneration by dichotomously regulating quiescence of stem and progenitor cells. Cell. 2016;166:894–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tuorto F, Herbst F, Alerasool N, et al. The tRNA methyltransferase Dnmt2 is required for accurate polypeptide synthesis during haematopoiesis. Embo J. 2015;34:2350–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Orford KW, Scadden DT. Deconstructing stem cell self-renewal: genetic insights into cell-cycle regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wires Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:640–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bagger FO, Rapin N, Theilgaard-Monch K, et al. HemaExplorer: a database of mRNA expression profiles in normal and malignant haematopoiesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sperling AS, Gibson CJ, Ebert BL. The genetics of myelodysplastic syndrome: from clonal haematopoiesis to secondary leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Signer RA, Magee JA, Salic A, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells require a highly regulated protein synthesis rate. Nature. 2014;509:49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sigurdsson V, Takei H, Soboleva S, et al. Bile acids protect expanding hematopoietic stem cells from unfolded protein stress in fetal liver. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:522–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Tahmasebi S, Amiri M, Sonenberg N. Translational control in stem cells. Front Genet. 2018;9:709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Silberstein L, Goncalves KA, Kharchenko PV, et al. Proximity-based differential single-cell analysis of the niche to identify stem/progenitor cell regulators. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:530–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Fett JW, Strydom DJ, Lobb RR, et al. Isolation and characterization of angiogenin, an angiogenic protein from human carcinoma-cells. Biochemistry-Us. 1985;24:5480–5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kieran D, Sebastia J, Greenway MJ, et al. Control of motoneuron survival by angiogenin. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14056–14061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kishimoto K, Liu SM, Tsuji T, et al. Endogenous angiogenin in endothelial cells is a general requirement for cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Yoshioka N, Wang L, Kishimoto K, et al. A therapeutic target for prostate cancer based on angiogenin-stimulated angiogenesis and cancer cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14519–14524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Chiou NT, Kageyama R, Ansel KM. Selective export into extracellular vesicles and function of tRNA fragments during T cell activation. Cell Rep. 2018;25:3356–3370 e3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Blanco S, Kurowski A, Nichols J, et al. The RNA-Methyltransferase Misu (NSun2) poises epidermal stem cells to differentiate. Plos Genet. 2011;7(12):e1002403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Frye M, Harada BT, Behm M, et al. RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science. 2018;361:1346–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gkatza NA, Castro C, Harvey RF, et al. Cytosine-5 RNA methylation links protein synthesis to cell metabolism. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Flores JV, Cordero-Espinoza L, Oeztuerk-Winder F, et al. Cytosine-5 RNA methylation regulates neural stem cell differentiation and motility. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8:112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Abbasi-Moheb L, Mertel S, Gonsior M, et al. Mutations in NSUN2 cause autosomal-recessive intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:847–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Khan MA, Rafiq MA, Noor A, et al. Mutation in NSUN2, which encodes an RNA methyltransferase, causes autosomal-recessive intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:856–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Martinez FJ, Lee JH, Lee JE, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies a splicing mutation in NSUN2 as a cause of a Dubowitz-like syndrome. J Med Genet. 2012;49:380–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Russo N, Acharya KR, Vallee BL, et al. A combined kinetic and modeling study of the catalytic center subsites of human angiogenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:804–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Chen YG, Chen R, Ahmad S, et al. N6-Methyladenosine modification controls circular RNA immunity. Mol Cell. 2019;76:96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Pandolfini L, Barbieri I, Bannister AJ, et al. METTL1 promotes let-7 microRNA processing via m7G methylation. Mol Cell. 2019;74:1278–1290 e1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Liu H, Begik O, Lucas MC, et al. Accurate detection of m(6)A RNA modifications in native RNA sequences. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Motorin Y, Helm M. Methods for RNA modification mapping using deep sequencing: established and new emerging technologies. Genes-Basel. 2019;10(1):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Zaccara S, Ries RJ, Jaffrey SR. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:608–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Delaunay S, Frye M. RNA modifications regulating cell fate in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:552–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Deng XL, Su R, Weng HY, et al. RNA N-6-methyladenosine modification in cancers: current status and perspectives. Cell Res. 2018;28:507–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, et al. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell. 2017;169:1187–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Soares AR, Santos M. Discovery and function of transfer RNA-derived fragments and their role in disease. Wires Rna. 2017;8::e1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].de Brouwer APM, Abou Jamra R, Kortel N, et al. Variants in PUS7 cause intellectual disability with speech delay, microcephaly, short stature, and aggressive behavior. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103:1045–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Shaheen R, Tasak M, Maddirevula S, et al. PUS7 mutations impair pseudouridylation in humans and cause intellectual disability and microcephaly. Hum Genet. 2019;138:231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Truitt ML, Ruggero D. New frontiers in translational control of the cancer genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:288–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Ingolia NT. Ribosome profiling: new views of translation, from single codons to genome scale applications of next-generation sequencing - innovation. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Pappireddi N, Martin L, Wuhr M. A review on quantitative multiplexed proteomics. Chembiochem. 2019;20:1210–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Gingold H, Tehler D, Christoffersen NR, et al. A dual program for translation regulation in cellular proliferation and differentiation. Cell. 2014;158:1281–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Goodarzi H, Nguyen HCB, Zhang S, et al. Modulated expression of specific tRNAs drives gene expression and cancer progression. Cell. 2016;165:1416–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Fish L, Zhang S, Yu JX, et al. Cancer cells exploit an orphan RNA to drive metastatic progression. Nat Med. 2018;24:1743–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Balatti V, Nigita G, Veneziano D, et al. tsRNA signatures in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:8071–8076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Lieberman J. Tapping the RNA world for therapeutics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:203–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Pliatsika V, Loher P, Magee R, et al. MINTbase v2.0: a comprehensive database for tRNA-derived fragments that includes nuclear and mitochondrial fragments from all the cancer genome atlas projects. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D152–D159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]