ABSTRACT

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a tight barrier that is critical for preventing the entry of pathogens and small molecules into the brain. HIV protein Tat (Tat) is known to disrupt the tight junctions of the BBB. Autophagy is an intracellular process that involves degradation and recycling of damaged organelles to the lysosome and has recently been implicated in the BBB disruption. The role of autophagy in Tat-mediated BBB disruption, however, remains elusive. Herein we hypothesized that Tat induces endothelial autophagy resulting in decreased expression of the tight junction protein ZO-1 leading to breach of the BBB. In this study, we demonstrated that exposure of human brain microvessel endothelial cells (HBMECs) to Tat resulted in induction of autophagy in a dose- and time-dependent manner, with upregulation of BECN1/Beclin 1, ATG5 and MAP1LC3B proteins and a concomitant downregulation of the tight junction protein ZO-1 ultimately leading to increased endothelial cell monolayer paracellular permeability in an in vitro BBB model. Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of autophagy resulted in the abrogation of Tat-mediated induction of MAP1LC3B with a concomitant restoration of tight junction proteins, thereby underscoring the role of autophagy in Tat-mediated breach of the BBB. Additionally, our data also demonstrated that Tat-mediated induction of autophagy involved PELI1/K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1. Increased autophagy and decreased ZO-1 was further recapitulated in microvessels isolated from the brains of HIV Tg26 mice as well as the frontal cortex of HIV-infected autopsied brains. Overall, our findings identify autophagy as an important mechanism underlying Tat-mediated disruption of the BBB.

KEYWORDS: Permeability, HAND, tight junction proteins, brain microvessels, Pellino-1

Introduction

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) controls the ability of molecules, cells and viruses to cross from the periphery into the brain and plays a critical role in maintaining homeostasis of the central nervous system (CNS).1,2 Disruption of the BBB contributes to the pathogenesis of many CNS diseases, including but not limited to HIV-associated CNS dysfunction.3,4 HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) have been described as a spectrum of neurocognitive dysfunctioning associated with HIV infection.5 Even in the presence of successful control of virus replication by combined antiretroviral therapy (cART), almost 15–55% of HIV infected individuals will go on to develop HAND.6 HAND is associated with reduced quality of life and difficulty with everyday functioning, making HAND an important healthcare concern and an unresolved issue.7 The study by Avison et al. demonstrated that chronic damage to the BBB resulted in impaired neurocognitive functioning in patients with HAND.8 The underlying mechanisms responsible for this, however, remain elusive.

One possible mediator of damage to the BBB in HIV-infected individuals is the early viral protein – Tat. Tat is both secreted by infected cells and also be taken up by neighboring cells in various tissues, despite successful control of virus replication by cART.9 In addition, Tat has also been shown to compromise the integrity of the BBB and to impact the expression and distribution of specific tight junction proteins such as Tight Junction Protein-1/Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) in the brain endothelium, leading ultimately to the breakdown of the BBB.10 The detailed underlying mechanism(s) mediating this breach, however, are not well understood.

Autophagy is an intracellular process that involves the degradation and recycling of damaged organelles to the lysosome.11 The study by Chen and colleagues12 demonstrated that autophagy is involved in nano-alumina-mediated disruption of the BBB. Recent studies have also implicated autophagy in Tat-mediated dysfunction of neurons and glia.13–15 In this study, we sought to examine the role of autophagy in Tat-mediated disruption of endothelial cells. We thus hypothesized that exposure of HBMECs to Tat results in the induction of autophagy leading to decreased expression of tight junction proteins and ensuing disruption of the BBB. The ability of Tat to induce autophagy along with a decreased expression of tight junction proteins was examined in both endothelial cells as well as in an in vivo model – the Tg26 mice that over express HIV proteins globally. To further validate the role of autophagy, we also examined the effects of blocking this pathway using both pharmacological as well as genetic silencing approaches in Tat-mediated regulation of tight junction proteins expression as well as endothelial permeability.

Results

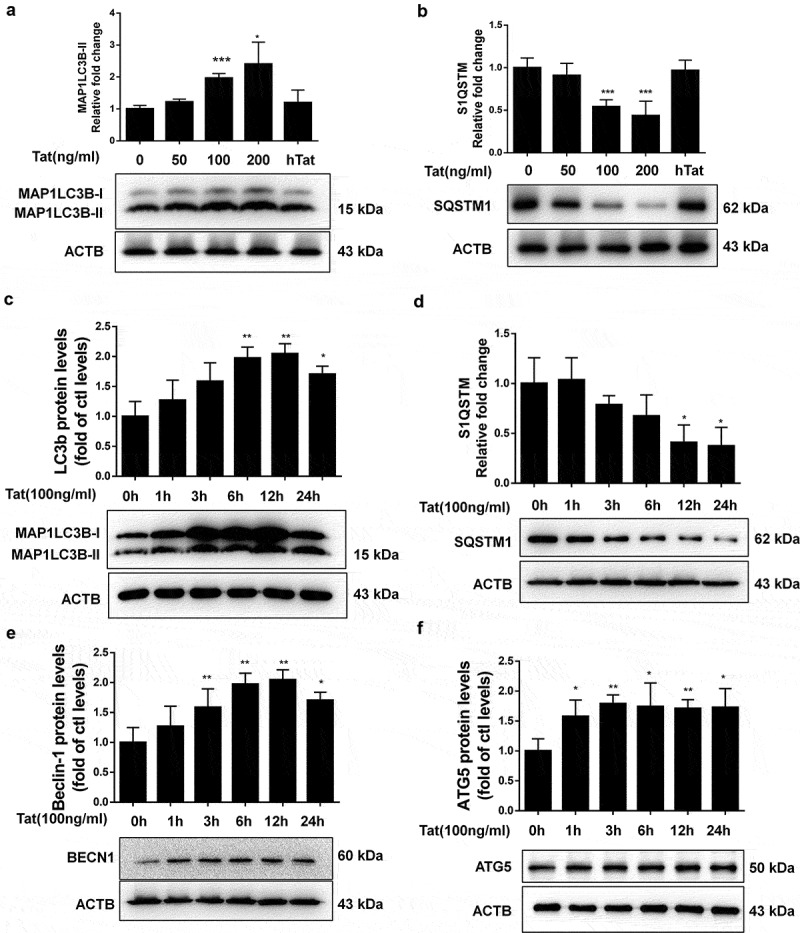

Exposure of HBMECs to Tat resulted in the induction of autophagy

HBMECs were exposed to Tat protein varying concentrations (50, 100 and 200 ng/ml) and heated-denatured Tat (100 ng/ml) for 24 h and then evaluated for the expression of autophagy mediator MAP1LC3B and autophagic flux marker SQSTM1. Tat exposure resulted in the induction of MAP1LC3B (Figure 1a) and reduction of SQSTM1 (Figure 1b) expression in a dose-dependent manner, with a maximal effect at 200 ng/ml Tat. Since 100 ng/ml Tat also showed strong effect on the induction of autophagy in HBMECs, the lower concentration of Tat (100 ng/ml) was chosen for all the ensuing experiments. As expected, heat-denatured Tat (100 ng/ml) did not affect MAP1LC3B and SQSTM1 expression, suggesting a requirement for native conformation of Tat for autophagy induction. Next, to determine the optimal time of Tat-mediated induction of autophagy in HBMECs treated with 100 ng/ml Tat, cells were exposed to Tat for varying times (1–24 h) and assessed for expression of autophagy markers. There was a significant induction of MAP1LC3B (Figure 1c), BECN1/Beclin 1 (Figure 1e) and ATG5 (Figure 1f) in the presence of Tat. Interestingly, the expression levels of SQSTM1 protein, a marker for autophagic flux, decreased from 3 h to 24 h exposure with Tat (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Tat-mediated induction of autophagy in HBMECs.

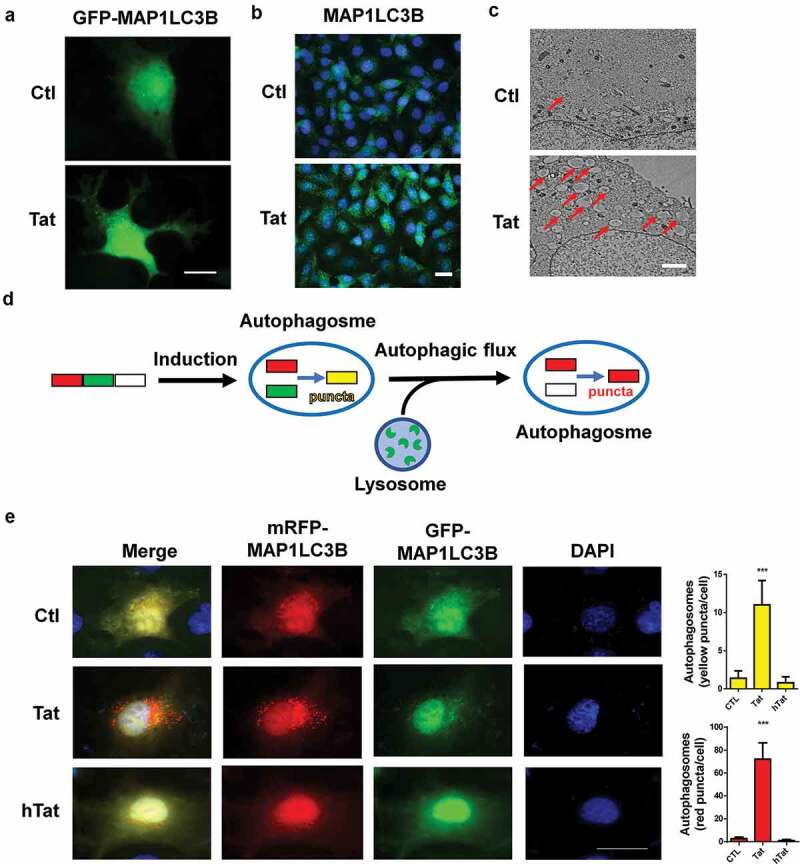

Tat increased intracellular autophagosome formation and autophagic flux in HBMECs

Having demonstrated that Tat induced autophagy in HBMECs as assessed by expression of autophagy markers, we next sought to confirm our findings by detecting Tat-mediated formation of autophagosomes, as reflected by the presence of MAP1LC3B puncta in HBMECs exposed to Tat. Herein HBMECs were transfected to overexpress a GFP-MAP1LCB plasmid, followed by exposure of the cells to Tat (100 ng/ml) for 24 h and, subsequent detection of GFP-MAP1LC3B puncta by immunofluorescence imaging. Intriguingly, the formation of exogenous MAP1LC3B puncta was increased in Tat-exposed HBMECs but not in the control vehicle-exposed cells (Figure 2a). Further validation of these findings was done by assessing the expression of endogenous levels of MAP1LC3B in the presence of Tat using immunofluorescence (Figure 2b) and TEM (Figure 2c) approaches. Next, we sought to examine the effect of Tat on autophagic flux. HBMECs were transfected with a tandem fluorescent-tagged MAP1LC3B plasmid for 24 h, followed by exposure of the cells to Tat protein for 24 h. In cells transfected with the plasmid construct, formation of autophagosomes resulted in emission of both red and green fluorescence from the tandem plasmid that, in turn, appeared as merged yellow puncta owing to the colocalization of mRFP and GFP-MAP1LC3B. Under acidic pH, however, the GFP signal of the tandem fluorescent-tagged MAP1LC3B fusion protein was quenched in the lysosomes, with the red fluorescence remaining stable, thus appearing as red puncta and indicating increased autophagic flux (Figure 2d). In HBMECs transfected with the tandem fluorescent-tagged MAP1LC3B reporter plasmid followed by exposure to HIV-1 Tat (100 ng/mL) for 24 h, there was a significant increase in the red puncta with a concomitant decrease in the green puncta, thereby indicating increased autophagy flux (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Tat-mediated induction of autophagosome formation and autophagic flux in HBMECs.

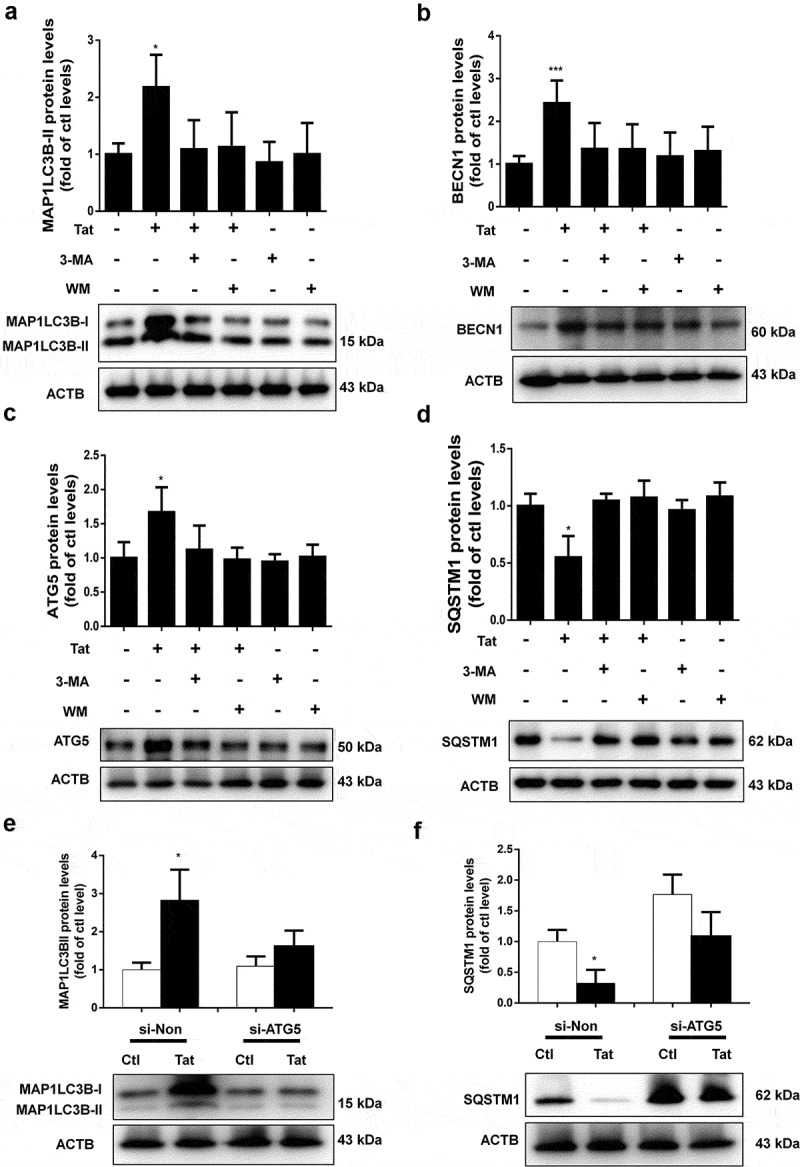

Tat-mediated disruption of tight junction protein involves autophagy

Next, we sought to examine the role of autophagy in Tat-mediated disruption of tight junction proteins. For this, HBMECs were pretreated with autophagy inhibitors 3-Methyladenine (3-MA) or wortmannin (WM) for 1 h followed by exposure of the cells to Tat and assessed for expression of autophagy markers. In cells pretreated with 3-MA or WM, exposure to Tat resulted in significantly inhibited expression of the autophagy markers MAP1LC3B, BECN1, ATG5 and SQSTM1 (Figure 3a-d). Furthermore, in cells transfected with ATG5 siRNA to knock down the expression of ATG5, Tat failed to upregulate the expression of MAP1LC3B and SQSTM1 compared with cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (Figure 3e,f).

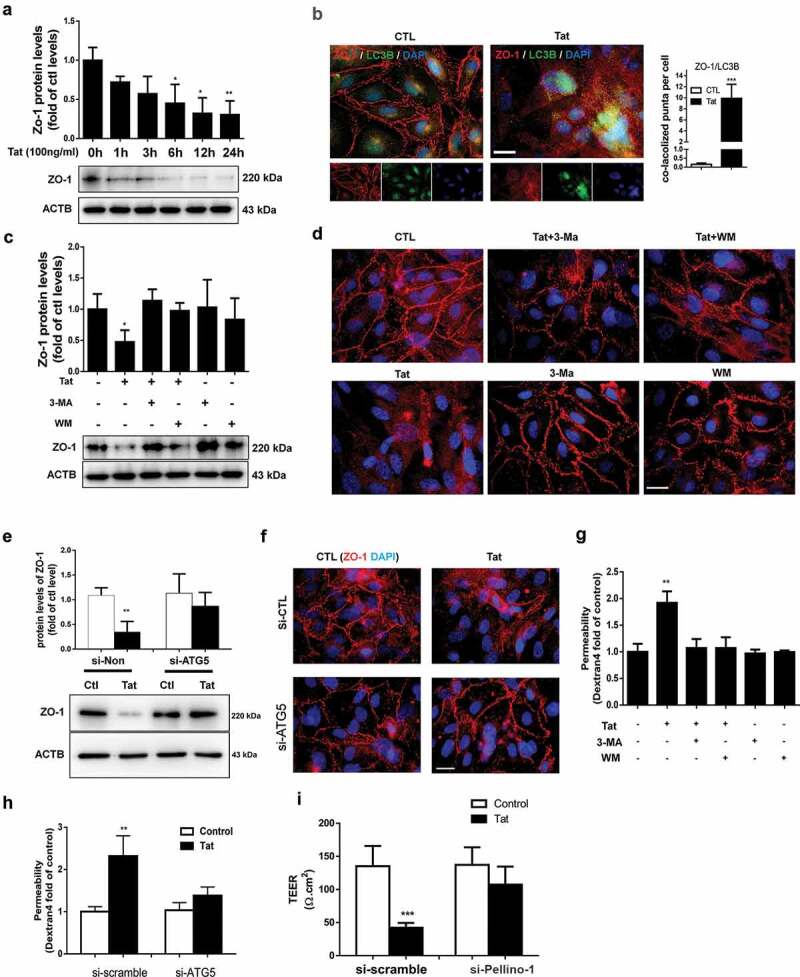

Next we sought to examine the expression of tight junction protein ZO-1 in HBMECs exposed to Tat. As shown in Figure 4a, exposure of cells to Tat resulted in time-dependent (1-24 h) downregulation in the expression of tight junction protein ZO-1 with a maximal decrease at 24 h. Interestingly, exposure of HBMECs to Tat resulted in increased colocalization of LC3 puncta with ZO-1, when assessed by immunostaining (Figure 4b). Next we sought to examine whether autophagy played a role in Tat-mediated downregulation of ZO-1. For this HBMECs were pretreated with autophagy inhibitor(s) 3-MA or WM for 1 h followed by exposure of the cells to Tat and assessed for the expression of ZO-1. In cells pretreated with 3-MA or WM, Tat resulted in significantly inhibited expression of ZO-1 as assessed by western blotting (Figure 4c) and immunofluorescence (Figure 4d). Similar to the findings with SQSTM1, HBMECs transfected with ATG5 siRNA failed to downregulate the expression of ZO-1 in the presence of Tat as assessed by western blotting (Figure 4e) and immunofluorescence (figure 4f).

Figure 3.

Effect of 3-MA, WM and ATG5 siRNA on Tat-mediated induction of autophagy in HBMECs.

Figure 4.

Role of autophagy in the Tat-mediated downregulation of tight junction protein and increased paracellular permeability in HBMECs.

Functional relevance of autophagy-mediated downregulation of ZO-1, leading to BBB disruption was further tested using trans-well endothelial cell monolayer permeability assays and TEER. As shown in Figure 4g, exposure of HBMEC monolayers to Tat resulted in increased permeability and furthermore, this effect was ameliorated in cells pretreated with autophagy inhibitors 3-MA and WM. Additionally, genetic knockdown ATG5 in HBMECs also resulted in abrogation of Tat-mediated increase in permeability of HBMECs assessed by trans-well endothelial cell monolayer permeability assays (Figure 4h) and TEER (Figure 4i).

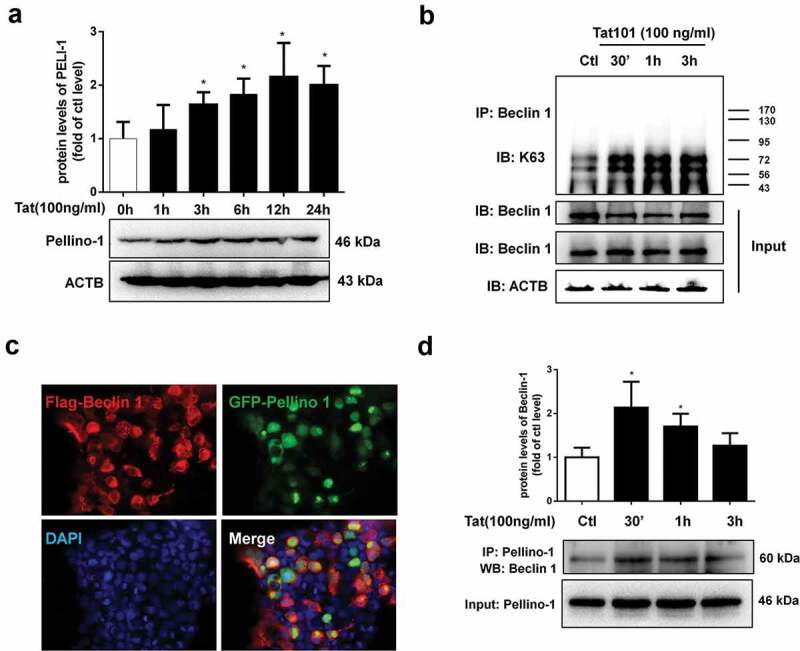

Tat-mediated induction of autophagy involves pellino-1/K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin 1

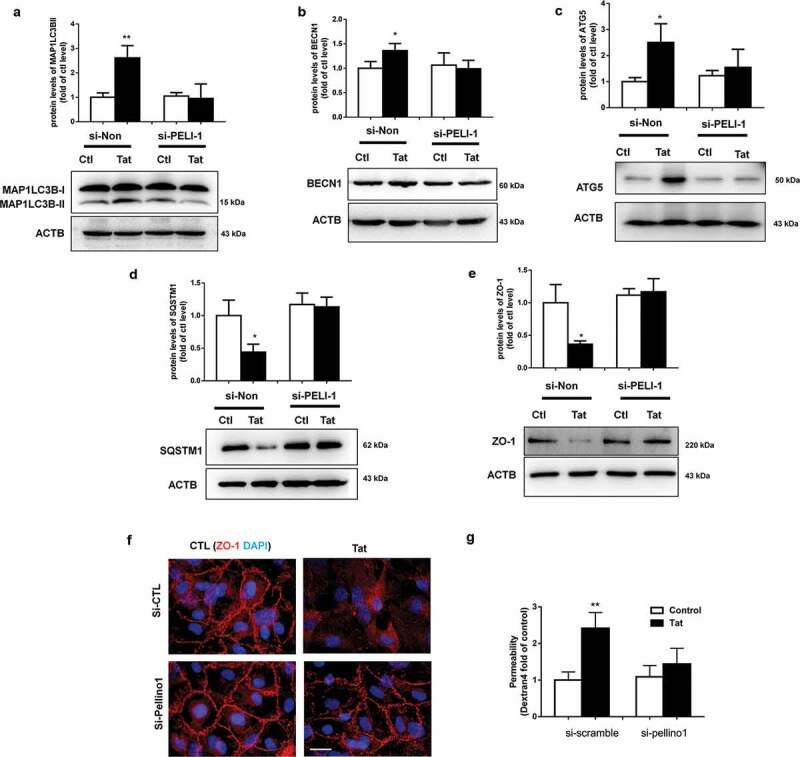

Having demonstrated that exposure of HBMECs to Tat induces autophagy with a concomitant decrease of tight junction protein ZO-1, in turn, leading to increased permeability; next, we sought to examine the mechanism(s) underlying this process. BECN1/Beclin 1 is a key component of a class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex (PI3KC3) that initiates the formation of autophagosomes by facilitating the localization of other autophagy proteins to the pre-autophagosomal membrane.12 Oligomerization of BECN1/Beclin 1 could thus serve as a scaffold for other molecules that associate with it for the initiation of autophagosome formation. For example, the study by Chong-Shan Shi et al.16 demonstrated that K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin 1 controlled TLR4 ligand-induced autophagy via a mechanism that depended on TRAF6. PELI1/Pellino-1 is a well-known E3-ubiquitin ligase involved in ubiquitination and has been reported to facilitate TRAF6-mediated ubiquitination of TLR signaling.17 Whether PELI1/Pellino-1 also mediates K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin 1 however, remains unknown. We thus sought to examine whether Tat-mediated induction of PELI1/Pellino-1 could lead to ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin 1, resulting in increased autophagy and permeability in HBMECs. As shown in Figure 5a, in HBMECs exposed to Tat there was significantly (P < .05) increased expression of PELI1/Pellino-1 protein starting at 1 h post exposure. Next, to determine whether BECN1/Beclin 1 underwent K63-linked ubiquitination, HBMECs were stimulated with Tat for various times (0–3 h). Cells were then lysed followed by dissociation of protein–protein interactions and then immunoprecipitated using the BECN1/Beclin 1 antibody and analyzed for the expression of K63-linked ubiquitin by western blotting. As shown in Figure 5b, in the presence of Tat there was increased smearing of ubiquitinated proteins specifically in the range of 43 to 95 kD, within 30 min post-Tat exposure with the effect peaking at 3 h. To next assess the binding of PELI1/Pellino-1 to BECN1/Beclin 1, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with Flag-BECN1/Beclin-1 and GFP-PELI1-1 plasmids to overexpress the proteins and analyzed by confocal microscopy for colocalization of the two proteins using the anti-GFP and anti-FLAG antibodies. As shown in Figure 5c, in cells overexpressing both the proteins, there was an indication of increased protein–protein interaction as evidenced by increased merging of the red and green fluorescence. Further validation of this interaction was done by series of co-immunoprecipitation assays using lysates from Tat-treated HBMECs. As shown in Figure 5d, in the presence of Tat, we consistently found the presence of BECN1/Beclin 1 immunoreactive band in the HBMEC lysates immunoprecipitated using the anti-PELI1/Pellino1 antibody. Having demonstrated that in HBMECs Tat induced the interaction of PELI1/Pellino-1 and BECN1/Beclin 1, leading, in turn, to K63-mediated ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin 1, we next sought to explore whether PELI1/Pellino-1 also played a role in Tat-mediated induction of autophagy and increased permeability in HBMECs. For this, HBMECs were transfected with either PELI1/Pellino-1 or scrambled siRNA followed by exposure of the cells to Tat and assessed for the expression of autophagy marker proteins by western blotting. As expected, HBMECs transfected with PELI1/Pellino-1 siRNA followed by exposure to Tat failed to alter the expression of autophagy markers, MAP1LC3B (Figure 6a), BECN1/Beclin 1 (Figure 6b), ATG5 (Figure 6c) and SQSTM1 (Figure 6d). Cells transfected with scrambled siRNA, on the other hand, continued to demonstrate Tat-mediated alteration of the autophagy markers.

Figure 5.

Tat-mediated induction of PELI1/K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin-1.

Figure 6.

Role of PELI1/K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin-1 in Tat-mediated induction of autophagy and increased paracellular permeability of HBMECs.

For further validation of the role of PELI1/Pellino-1 in Tat-mediated disruption of HBMECs, we knocked down the expression of PELI1/Pellino-1 using the siRNA approach and subsequently assessed the effect of Tat exposure on the expression of tight junction ZO-1 and permeability of HBMECs. As shown in Figures 6e,f, in HBMECs transfected with PELI1/Pellino-1 siRNA, Tat exposure failed to downregulate the expression of ZO1 as assessed by western blotting (Figure 6e) and immunofluorescence (figure 6f). Additionally, in the PELL1 knocked down group, Tat exposure had no effect on cellular permeability as evidenced by dextran fluorescence across the in vitro blood-brain barrier model (Figure 6g).

Presence of increased autophagy and disrupted tight junctions in the brains of HIV Tg26 mice and in HIV+ humans

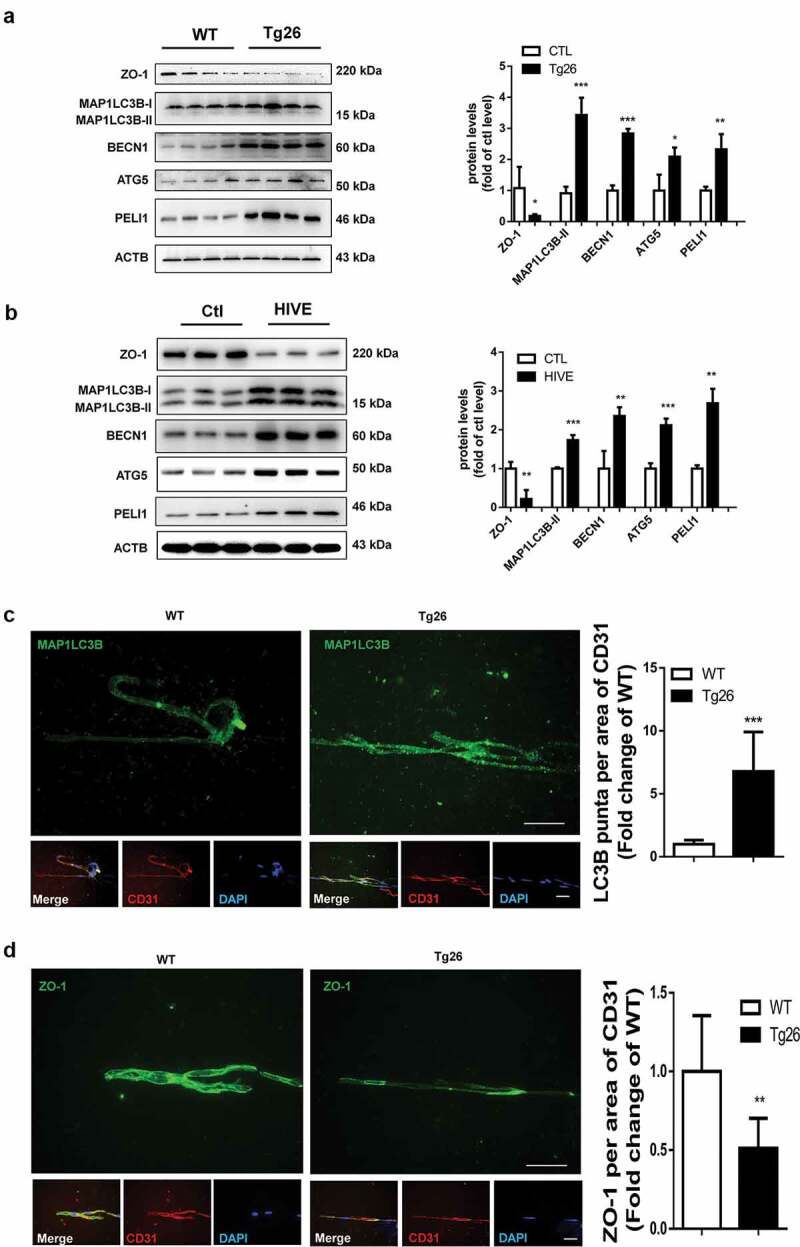

To validate the in vitro findings on the role of autophagy in Tat-mediated downregulation of tight junction proteins, we next sought to assess the expression of both autophagy marker MAP1LC3B, as well as the tight junction protein ZO-1 in the brain microvascular endothelial cells present in the microvessels isolated from the brains of Tg26 mice and HIV, infected humans. There was increased expression of PELI1/Pellino-1, autophagy markers BECN1/Beclin-1, ATG5 and MAP1LC3B with a concomitantly decreased expression of ZO-1 in the lysates of brain microvessels isolated from HIV Tg26 mice (Figure 7a) and HIV+ subjects (Figure 7b). Additionally, isolated microvessels from both HIV Tg26 as well as WT mice were also subjected to double immunostaining using antibodies specific for MAP1LC3B (green color) and PECAM1/CD31 (endothelial cell marker, red color). Our findings demonstrated a significant upregulation of MAP1LC3B puncta in PECAM1/CD31-positive endothelial cells in the microvessels isolated from HIV-1 Tg26 (Figure 7c) that was accompanied by significant downregulation of ZO-1 expression in endothelial cells (Figure 7d).

Figure 7.

Induction of autophagy and disruption of tight junction proteins in the brains of Tg26 mice and HIV-E subjects.

Discussion

The breach of BBB is one of the underlying features contributing to neuroinflammation associated with HAND.3,18-20 Various reports implicate disruption of the BBB during HIV-1 infection,21,22 with a prominent role of the viral protein Tat, which is often implicated as one of the pathogenic factors of HAND.23,24 Many studies implicate the role of autophagy in vascular leakage and BBB disruption, for example, the inflammatory mediator HMGB1 has been shown to induce autophagy, leading, in turn, to increased vascular permeability.25,26 Additionally, sepsis-mediated secretion of cytokines has also been shown to increase both vascular permeability as well as autophagy.26,27 In a separate study, alumina nanoparticles have also been shown to induce brain endothelial barrier disruption via induction of autophagy.12 It remains less understood, however, whether Tat-mediated breach of BBB involves the autophagy pathway.

Based on the above information, we thus hypothesized that exposure of HBMECs to Tat could lead to the induction of endothelial autophagy, which in turn, could contribute to the downregulated expression of tight junction proteins, ultimately resulting in the disruption of BBB. Our findings demonstrate the time-dependent induction of autophagy in HBMECs exposed to Tat. Increased autophagy, in turn, contributed to Tat-mediated downregulation of tight junction protein ZO-1, thereby increasing vascular permeability in our in vitro BBB model. We do acknowledge the limitation of our in vitro BBB model is that it comprises of a single cell type – HBMECs. Although brain microvascular endothelial cells are the major components of the BBB, many studies have included other cell types such as astrocytes, pericytes and neurons in their model system, all of which play crucial regulatory roles in the maintenance of the BBB.28 It is reported29 that the TEER values measured in vivo could reach as high as 5900 Ω.cm2 which is markedly greater than that achieved in our in vitro model (around 150 Ω.cm2). In our future studies will plan to use complex in vitro co-culture models involving other cell types. Next, we sought to examine the molecular mechanism(s) underlying this process. BECN1/Beclin-1 is a key component of class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex (PI3KC3) that initiates the formation of autophagosomes by facilitating the localization of other autophagy proteins to the pre-autophagosomal membrane.12 K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin-1 has been demonstrated to be required for the initiation of autophagosome formation.30 In our current study, we demonstrated a novel mechanism by which Tat triggered PELI1/K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin-1 resulting in the induction of autophagy with a concomitant downregulated the expression of tight junction proteins ZO-1, ultimately leading to increased vascular permeability. Our findings demonstrated the Tat-mediated induction of autophagosome formation with a concomitant down-regulated expression of SQSTM1 in HBMECs. These findings are in agreement with previous studies in glial cells demonstrating Tat-mediated induction of BAG3 proteins, subsequently leading to increased autophagy, as evidenced by an increase in MAP1LC3B expression and a decrease in SQSTM1.15 Reports in other cells such as the neurons by Hui et al.31 however, have reported that Tat (100 nM, 1.6 µg/ml) was associated with lysosomes resulting in reduced expression of MAP1LC3B. It is thus possible that Tat could exert differential effects in different cell types, and also that these effects could be dose-dependent.

In accordance with earlier reports,32,33 our findings also demonstrated that in HBMECs, Tat exposure resulted in decreased expression of tight junction protein (ZO-1) that was accompanied by increased permeability of these cells. The function of tight junctions regulating permeability is based on two pathways: (1) “pore” pathway that can carry small uncharged solutes and specific ions and (2) “leak” pathway that can carry none-charged larger molecules.34 The TJ membrane proteins such as claudins (such as claudin-2) have been shown to play a crucial role in regulating the cation-selective pore pathway while the barrier-forming protein occludin is known to regulate the leak pathway. Induction of autophagy has been shown to result in degradation of claudin-2, which, in turn, leads to enhancement of TJ barrier function with increased transepithelial resistance (TEER). In contrast, nitric oxide-mediated induction of autophagy resulted in lysosome-dependent degradation of claudin-5 in the endothelial cells under prolonged ischemia (OGD/R injury), leading to disrupted endothelial barrier.35 In addition, Kim et al. have demonstrated oxygen-glucose deprivation-mediated induction of ischemic autophagy in the brain endothelial cells, which, in turn, leads to the degradation of occludin with permeability disruption.36 Overall, autophagy-mediated degradation of claudins (pore pathway) and occludin (leaky pathway) has been shown to be critical for regulating function of the TJ barrier. ZO-1 is known to act as a scaffolding protein linking claudin and occludin to the actin cytoskeleton. ZO-1 is thus important for both pore and leak pathways in the maintenance of BBB permeability. In the current study, we also found that exposure of HBMECs to Tat induced colocalization of MAP1LC3B puncta with ZO-1 and also that Tat-mediated downregulation of ZO-1 was attenuated by pretreating the cells with pharmacological inhibitors of autophagy as well as by a silencing approach using si-RNA-ATG5. Collectively these findings underpin the role of autophagy in Tat-mediated downregulation of ZO-1. Corroboration of these findings was also done ex vivo, wherein we observed upregulation of the autophagy marker MAP1LC3B and a concomitant downregulation of ZO-1 in microvessels isolated from the brains of HIV-1 Tg26 mice. In line with these observations and of importance, we also observed increased autophagy and disrupted expression of ZO-1 in sections of frontal cortices from the brains of individuals with HIV-E compared with the uninfected controls, thereby underscoring the conservation of this effect across species.

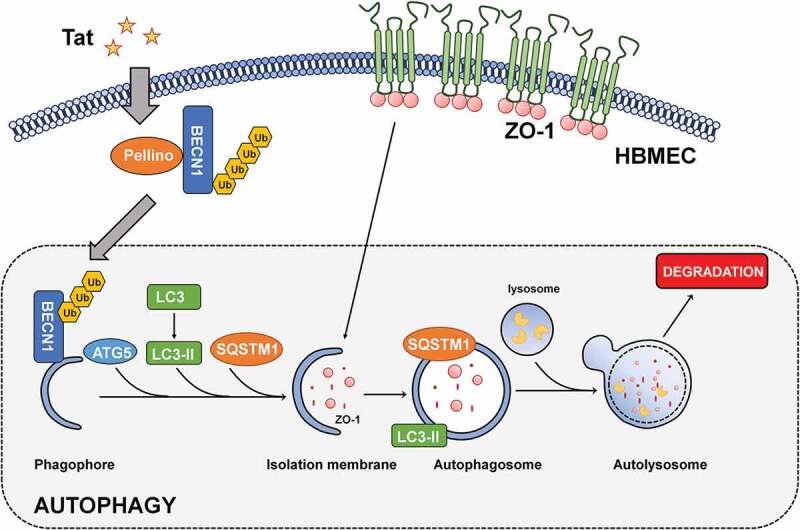

A number of other mechanisms besides autophagy have been implicated in Tat-mediated disruption of BBB underlying HAND. For example, Tat can induce activation of oxidative stress,37,38 which, in turn, leads to increased expression of inflammatory genes such as MCP-1,39 TNF-α40 IL6,41 IL1-β42 and PDGF-BB.4 Importantly, it has been well-established that induction of inflammatory chemokines in the brain such as MCP-143,44can further perpetuate increased recruitment of HIV-infected monocytes into the CNS, thereby enhancing the pool of cytotoxic Tat in the CNS. In light of our current studies, this increased pool of Tat could cause a further cascade of neuroinflammation by mediating disruption of the BBB permeability. In parallel, Tat has also been shown to induce apoptosis of brain endothelial cells by activating caspase-3,45 which could further exacerbate BBB breach, leading to an even more increased influx of HIV-infected monocytes into the CNS. Such a vicious loop triggered by Tat could continually perpetuate neuroinflammation,42,46,47 likely contributing to the development and persistence of HAND. Our novel findings for the first time implicate autophagy as a regulator in Tat-mediated disruption of BBB, which, in turn, could lead to a further increase in the influx of peripheral leukocytes into the CNS, thereby contributing to underlying neuroinflammation. Herein we also demonstrate a novel mechanism by which Tat induces autophagy involving the PELI1/K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin-1. Our results have established a novel link between PELI1/K63-linked ubiquitination of BECN1/Beclin-1, autophagy and disruption of tight junction proteins (Figure 8), thereby suggesting that interventions aimed at dampening the autophagy signaling pathway could be considered as promising therapeutic targets for abrogating HIV-1-mediated neuroinflammation and progression of HAND.

Figure 8.

Schematic of Tat-mediated induction of the BBB disruption via autophagy.

Materials and methods

WM (W3144), 3-MA (M9281), fluorescein isothiocyanate Dextran-4 and Mammalian Cell Lysis kit were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Recombinant Tat was purchased from ImmunoDiagnostics (Foster City, CA, USA). The transfection reagent Lipofectamine 2000 was purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA). Antibodies were as follows: ZO-1 (Cat # 40–2200), mouse anti-β-actin antibody (Cat # AM4302), Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cat #:A-11012) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Cat # A32723) were purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA); BECN1/Beclin 1 (sc-48341), MAP1LC3B (sc-16756), PELI1 (sc-271065) Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA); ATG5 (NB110-53818), SQSTM1 (H00008878-M01), Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA); goat anti-rabbit (111-035-144) and goat anti-mouse (115-035-003), Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). Short interfering RNA (siRNA) of ATG5 (Cat # AM16708) was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Hudson, NH, USA). Trypsin were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Cell Sciences (Newburyport, MA, USA). The GFP-MAP1LC3B plasmid was a generous gift from Dr. Howard Fox (University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE), and HIV-1 transgenic mice (Tg26), which express high levels of HIV proteins, including Tat, rev, nef, vif, vpr and vpu, were established as described previously48 and kindly provided by Dr. Roy L. Sutliff (Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Atlanta, GA). Human brain tissue samples were obtained from the Cell-Animal-Tissue Core of UNMC.

HBMECs culture

Human primary brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs, ScienCell, Cat # 1000) were purchased from ScienCell (the donor information: Donor1: fetal brain, age 21 weeks, male, TAN Record: #1404, Donor2: fetal brain, age 21 weeks, unknown sex, TAN Record: #1405, Donor3: fetal brain, age 21 weeks, unknown sex, TAN Record: #1409). HBMECs were grown and routinely maintained in Endothelial Cell Medium (ScienCell, Cat # 1001) with 5% FBS, 5 ml Endothelial Cell Growth Supplement (ECGS, ScienCell, Cat #1052), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2 and used up to passage 5.

Western blotting

Cell and brain lysates were extracted using the Mammalian Cell Lysis kit (MCL1-1KT), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Equal amounts of protein were separated by electrophoresis in a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel followed by transfer to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with either 5% nonfat dry milk or 5% BSA in PBS (137 mM NaCl; 2.7 mM KCl; 10 mM Na2HPO4; 2 mM KH2PO). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with TBST, the blots were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h, followed by 3 washes, and MAP1LC3B, SQSTM1, BECN1/Beclin1, ATG5 and ZO-1 were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit. β-Actin was used as an internal control to normalize the protein amounts loaded.

Plasmid transfection

HBMECs were seeded into 24-well plates and maintained in complete culture medium overnight. The next day, cells were incubated with GFP – MAP1LC3B plasmid dissolved in 100 µl Opti-MEM together with Lipofectamine 2000 for 20 min at room temperature. Following exposure to the DNA-lipofectamine mixture, cells were incubated in serum-free medium for 6 h at 37°C. The medium was then replaced with complete culture medium. After 24 h, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml Tat for 24 h and imaged under a fluorescence microscope to visualize exogenous GFP-MAP1LC3B puncta formation.

Immunocytochemistry

HBMECs were plated on coverslips and exposed to 100 ng/ml Tat for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were then incubated with a blocking buffer containing 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubating with either rabbit MAP1LC3B antibody (1:200) or ZO-1 (1:200) overnight at 4°C. The next day, the cells were washed three times, followed by incubation with the secondary Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (at 1:500) for 2 h. After a final wash with PBS, the coverslips were mounted with Prolong Gold Anti-fade Reagent. HBMECs were analyzed using a fluorescence microscope for endogenous MAP1LC3B puncta formation and ZO-1 expression. Images were processed using the AxioVs 40 Version 4.8.0.0 software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

HBMECs were exposed to 100 ng/ml Tat for 24 h, then washed twice with PBS. The cells were fixed by 2.5% TEM grade glutaraldehyde fixative buffer for 30 min at room temperature. HBMECs were collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 200 g. Subsequently, the cell pellets were re-suspended in the fixative solution and stored at 4°C until used for electron microscopy.

Cell permeability

HBMECs were seeded into 6.5-mm polyester Transwell inserts (0.4-μm pore size) to form monolayers. After reaching confluency, HBMEC monolayers were treated with 100 ng/ml Tat for 24 h in the absence or presence of inhibitors 3-MA and WM. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled Dextran-4 (1 mg/mL) was then added, followed by the detection of changes in monolayer permeability by measuring changes of fluorescence in the lower chamber at excitation/emission wavelengths of 480/530 nm.

Transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER)

The transwell with PET membrane (6.5-mm polyester Transwell inserts (0.4-μm pore size)) was filled with fresh HBMEC culture media in the upper and lower chambers at the same height. The TEER of blank PET membrane was assessed by a Millicell electrical resistance system (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Next, we seeded the HBMECs transfected with either siRNA-control or siRNA-ATG5 into the transwell insert to form the monolayers, followed by treating of HBMECs with or without HIV Tat for 24 h. The TEER of the HBMECs were assessed by a Millicell electrical resistance system. The resistance of the cell monolayer was calculated by subtracting the ‘blank’ cell-free inserts from the TEER of the transwell insert containing cells.

Short interfering RNA transfection

HBMECs were seeded into 24-well plates and maintained with complete culture medium overnight. The next day, ATG5 siRNA was dissolved in 100 µl Opti-MEM and incubated with Lipofectamine 2000 for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were exposed to the siRNA-lipofectamine mixture and incubated in serum-free medium for 6 h at 37°C. The medium was then replaced with complete culture medium. After 24 h, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml Tat for 24 h, and MAP1LC3B, and ZO-1 expression was measured by Western blotting.

Animals

All mice strains (male, 8–10 weeks), wild-type C57BL/6 mice and Tg26 mice were housed under conditions of constant temperature and humidity on a half/half light and dark cycle. All animal procedures were performed following approved protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the National Institute of Health. Animals were divided into two groups with 6 per group (wild-type and Tg26) for brain microvessel isolation.

Isolation of brain microvessels

Mouse and human (patients with HIV-E were obtained from the Cell-Animal-Tissue Core of UNMC (for clinical data, see Table 1)) brain microvessels were isolated following a differential centrifugation protocol as described previously.2 Briefly, the brains were removed and immediately immersed in ice-cold isolation buffer A (103 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4 and 15 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), followed by the removal of the cerebellum, olfactory bulb and meninges. Subsequently, the brains were homogenized in 2.5 ml of isolation buffer B (10 mM glucose, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM Na pyruvate and 10 g/L Dextran, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors. The homogenates were added to Dextran (6 ml; 26%) and centrifugated for 20 min at 5800 × g. Pellets were resuspended in isolation buffer B, followed by filtration through a 70-μm mesh filter. Isolated brain microvessels were then harvested from the filtered homogenates by centrifugation. Some pure brain microvessels were used for immuno-staining by spreading on glass slides and prepared for MAP1LC3B, PECAM1/CD31 and ZO-1 detection; others were lysed for Western blotting to detect MAP1LC3B, BECN1/Beclin 1, ATG5 and ZO-1.

Table 1.

Brain tissue donor characteristics.

| Age (years) |

Gender | Donor program | Brain region | Pathology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-Negative Control Patients | |||||

| 42 | Male | From pathology | Cortex | Hypertensive and severe conronary artery disease. Old infarct revealed-right temporal area. | |

| 66 | Male | From pathology | Cortex | Massive pulmonary consolidation secondary to diffuse alveolar damage (ARDS). Cryptogenic cirrhosis complicated with portal hn, upper GI bleed due to ulcers, hepatic encephalopathy, corpulmonate, chronic renal failure. | |

| 55 | Male | From pathology | Cortex | Sudden Cardiac death in a setting of moderate-severe coronary artery disease | |

| HIV- E Patients | |||||

| 38 | Male | Gift of hope | Cortex | Brain: HIV Encephalopathy/Leukoencephalopathy. No evidence of toxoplasma infection or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. AIDS | |

| 36 | Male | Gift of hope | Cortex | Brain: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Encephalitis. Endstage AIDS Mild dementia, opportunistic infections. | |

| 34 | Male | Gift of hope | Cortex | Brain: Encephalitis with microglial nodules suggestive of CMV infection. AIDS | |

Statistical analysis

Bonferroni post hoc tests were used following a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare data between groups. Results were judged statistically significant if Bonferroni test p < .05. All the analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 7.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc. CA, USA).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tom Bargar and Nicholas Conoan of the Electron Microscopy Core Facility (EMCF) at the University of Nebraska Medical Center for technical assistance. The EMCF is supported by state funds from the Nebraska Research Initiative (NRI) and the University of Nebraska Foundation, and institutionally by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- CNS

Central nervous system

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- HBMECs

Human brain microvessel endothelial cells

- HAND

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder

- siRNA

Short interfering RNA

- Tat

HIV Tat

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- Tg26

HIV-1 transgenic mice

- WM

Wortmannin

- 3-MA

3-Methyladenine

Authors’ contributions

SB designed the research. KL designed the research, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. FN, GH, SS and MG analyzed the data and assisted with writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Additional support was obtained from the Nebraska Center for Substance Abuse Research.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Upadhyay RK. Drug delivery systems, CNS protection, and the blood brain barrier. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:1. doi: 10.1155/2014/869269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss N, Miller F, Cazaubon S, Couraud PO.. The blood-brain barrier in brain homeostasis and neurological diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:842–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma R, Yang L, Niu F, Buch S. HIV Tat-mediated induction of human brain microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis involves endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:132–142. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8991-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niu F, Yao H, Zhang W, Sutliff RL, Buch S. Tat 101-mediated enhancement of brain pericyte migration involves platelet-derived growth factor subunit B homodimer: implications for human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11812–11825. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1139-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clifford DB, Ances BM. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:976–986. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70269-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saylor D, Dickens AM, Sacktor N, Haughey N, Slusher B, Pletnikov M, Mankowski JL, Brown A, Volsky DJ, McArthur JC, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder–pathogenesis and prospects for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:234–248. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saylor D, Dickens AM, Sacktor N, Haughey N, Slusher B, Pletnikov M, Mankowski JL, Brown A, Volsky DJ, McArthur JC, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder - pathogenesis and prospects for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:309. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avison MJ, Nath A, Greene-Avison R, Schmitt FA, Greenberg RN, Berger JR. Neuroimaging correlates of HIV-associated BBB compromise. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niu F, Yao H, Liao K, Buch S, Tat HIV. 101-mediated loss of pericytes at the blood-brain barrier involves PDGF-BB. Ther Targets Neurol Dis. 2015;2(1):e471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pu H, Tian J, Flora G, Lee YW, Nath A, Hennig B, Toborek M. HIV-1 Tat protein upregulates inflammatory mediators and induces monocyte invasion into the brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:224–237. doi: 10.1016/S1044-7431(03)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010;221:3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Zhang B, Toborek M. Autophagy is involved in nanoalumina-induced cerebrovascular toxicity. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fields J, Dumaop W, Elueteri S, Campos S, Serger E, Trejo M, Kosberg K, Adame A, Spencer B, Rockenstein E. HIV-1 Tat alters neuronal autophagy by modulating autophagosome fusion to the lysosome: implications for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neurosci. 2015;35:1921–1938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3207-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thangaraj A, Periyasamy P, Liao K, Bendi VS, Callen S, Pendyala G, Buch S. HIV-1 TAT-mediated microglial activation: role of mitochondrial dysfunction and defective mitophagy. Autophagy. 2018;14:1596–1619. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1476810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruno AP, De Simone FI, Iorio V, De Marco M, Khalili K, Sariyer IK, Capunzo M, Nori SL, Rosati A. HIV-1 Tat protein induces glial cell autophagy through enhancement of BAG3 protein levels. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3640–3644. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.952959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi CS, Kehrl JH. Traf6 and A20 differentially regulate TLR4-induced autophagy by affecting the ubiquitination of Beclin 1. Autophagy. 2010;6:986–987. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinsella S, Fichtner M, Watters O, Konig HG, Prehn JHM. Increased A20-E3 ubiquitin ligase interactions in bid-deficient glia attenuate TLR3- and TLR4-induced inflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:130. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1143-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai Y, Yang L, Callen S, Buch S. Multiple faceted roles of cocaine in potentiation of HAND. Curr HIV Res. 2016;14:412–416. doi: 10.2174/1570162X14666160324125158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagashev A, Sawaya BE. Roles and functions of HIV-1 Tat protein in the CNS: an overview. Virol J. 2013;10:358. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atluri VS, Hidalgo M, Samikkannu T, Kurapati KR, Jayant RD, Sagar V, Nair MPN. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus on blood-brain barrier integrity and function: an update. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:212. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masia M, Padilla S, Garcia N, Jarrin I, Bernal E, Lopez N, Hernández I, Gutiérrez F. Endothelial function is impaired in HIV-infected patients with lipodystrophy. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:101–110. doi: 10.3851/IMP1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McArthur JC, Steiner J, Sacktor N, Nath A. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive disorders: mind the gap. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:699–714. doi: 10.1002/ana.22053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal L, Louboutin JP, Reyes BA, Van Bockstaele EJ, Strayer DS. HIV-1 Tat neurotoxicity: a model of acute and chronic exposure, and neuroprotection by gene delivery of antioxidant enzymes. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King JE, Eugenin EA, Buckner CM, Berman JW. HIV tat and neurotoxicity. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1347–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang D, Kang R, Livesey KM, Cheh C-W, Farkas A, Loughran P, Hoppe G, Bianchi ME, Tracey KJ, Zeh HJ. Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:881–892. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann S, Grasberger H, Jung P, Bidlingmaier M, Vlotides J, Janssen OE, Landgraf R. The tumour necrosis factor-alpha induced vascular permeability is associated with a reduction of VE-cadherin expression. Eur J Med Res. 2002;7:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris J. Autophagy and cytokines. Cytokine. 2011;56:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srinivasan B, Kolli AR, Esch MB, Abaci HE, Shuler ML, Hickman JJ. TEER measurement techniques for in vitro barrier model systems. J Lab Autom. 2015;20:107–126. doi: 10.1177/2211068214561025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butt AM, Jones HC, Abbott NJ. Electrical resistance across the blood-brain barrier in anaesthetized rats: a developmental study. J Physiol. 1990;429:47–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuang E, Qi J, Ronai Z. Emerging roles of E3 ubiquitin ligases in autophagy. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hui L, Chen X, Haughey NJ, Geiger JD. Role of endolysosomes in HIV-1 Tat-induced neurotoxicity. ASN Neuro. 2012;4:243–252. doi: 10.1042/AN20120017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu R, Feng X, Xie X, Zhang J, Wu D, Xu L. HIV-1 Tat protein increases the permeability of brain endothelial cells by both inhibiting occludin expression and cleaving occludin via matrix metalloproteinase-9. Brain Res. 2012;1436:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahajan SD, Aalinkeel R, Sykes DE, Reynolds JL, Bindukumar B, Fernandez SF, Chawda R, Shanahan TC, Schwartz SA. Tight junction regulation by morphine and HIV-1 tat modulates blood–brain barrier permeability. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:528–541. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen L, Weber CR, Raleigh DR, Yu D, Turner JR. Tight junction pore and leak pathways: a dynamic duo. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:283–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Weaver J, Jin X, Zhang Y, Xu J, Liu KJ, Li W, Liu W. Nitric oxide interacts with caveolin-1 to facilitate autophagy-lysosome-mediated claudin-5 degradation in oxygen-glucose deprivation-treated endothelial cells. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:5935–5947. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9504-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim KA, Shin D, Kim JH, Shin YJ, Rajanikant GK, Majid A, Baek S-H, Bae O-N. Role of autophagy in endothelial damage and blood-brain barrier disruption in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:1571–1579. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deshmane SL, Mukerjee R, Fan S, Del Valle L, Michiels C, Sweet T, Rom I, Khalili K, Rappaport J, Amini S. Activation of the oxidative stress pathway by HIV-1 Vpr leads to induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11364–11373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809266200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Louboutin JP, Agrawal L, Reyes BA, Van Bockstaele EJ, Strayer DS. Oxidative stress is associated with neuroinflammation in animal models of HIV-1 tat neurotoxicity. Antioxidants (Basel). 2014;3:414–438. doi: 10.3390/antiox3020414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khiati A, Chaloin O, Muller S, Tardieu M, Horellou P. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) gene expression by human immunodeficiency virus-1 Tat in human astrocytes is CDK9 dependent. J Neurovirol. 2010;16:150–167. doi: 10.3109/13550281003735691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ben Haij N, Planes R, Leghmari K, Serrero M, Delobel P, Izopet J, BenMohamed L, Bahraoui E. HIV-1 tat protein induces production of proinflammatory cytokines by human dendritic cells and monocytes/macrophages through engagement of TLR4-MD2-CD14 complex and activation of NF-kappaB pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ambrosino C, Ruocco MR, Chen X, Mallardo M, Baudi F, Trematerra S, Quinto I, Venuta S, Scala G. HIV-1 Tat induces the expression of the interleukin-6 (IL6) gene by binding to the IL6 leader RNA and by interacting with CAAT enhancer-binding protein beta (NF-IL6) transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14883–14892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chivero ET, Guo ML, Periyasamy P, Liao K, Callen SE, Buch S. HIV-1 tat primes and activates microglial NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation. J Neurosci. 2017;37:3599–3609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3045-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eugenin EA, Osiecki K, Lopez L, Goldstein H, Calderon TM, Berman JW. CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mediates enhanced transmigration of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected leukocytes across the blood-brain barrier: a potential mechanism of HIV-CNS invasion and NeuroAIDS. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1098–1106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3863-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cinque P, Vago L, Mengozzi M, Torri V, Ceresa D, Vicenzi E, Transidico P, Vagani A, Sozzani S, Mantovani A. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 correlate with HIV-1 encephalitis and local viral replication. AIDS. 1998;12:1327–1332. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199811000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim TA, Avraham HK, Koh YH, Jiang S, Park IW, Avraham S. HIV-1 Tat-mediated apoptosis in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:2629–2637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang L, Niu F, Yao H, Liao K, Chen X, Kook Y, Ma R, Hu G, Buch S. Exosomal miR-9 released from HIV Tat stimulated astrocytes mediates microglial migration. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2018;13:330–344. doi: 10.1007/s11481-018-9779-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu G, Liao K, Yang L, Pendyala G, Kook Y, Fox HS, Buch S. Tat-mediated induction of miRs-34a & −138 promotes astrocytic activation via downregulation of SIRT1: implications for aging in HAND. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2017;12:420–432. doi: 10.1007/s11481-017-9730-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kopp JB, Klotman ME, Adler SH, Bruggeman LA, Dickie P, Marinos NJ, Eckhaus M, Bryant JL, Notkins AL, Klotman PE. Progressive glomerulosclerosis and enhanced renal accumulation of basement membrane components in mice transgenic for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1577–1581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]