Abstract

Most countries exempted agri-food systems from “lockdown” policies introduced in early 2020 to curb the COVID-19 outbreak. Yet these policies had economywide implications, implying that even exempted sectors were indirectly affected by disruptions to supply chains and falling consumer demand. After its first confirmed case, Nigeria's federal and state governments implemented lockdowns across most cities and states. This included closing all borders and many non-essential businesses. Nigeria also faced declining remittances and export demand caused by the global recission. We estimate the economywide impacts of these lockdown policies and global shocks using a multiplier model of Nigeria calibrated to a 2018 social accounting matrix. We simulate Nigeria's 8-week lockdown (March–June), as well as “recovery” scenarios until the end of 2020. Simulations draw on information from official data, policy announcements, and interviews with government agencies and private sector and industry groups. Findings indicate that total GDP fell 23% during the lockdown. Agri-food system GDP fell 11%, primarily due to restrictions on food services. Household incomes also fell by a quarter, leading a 9% points increase in the national poverty rate. Given the scale of these economic losses, our recovery scenarios indicate that, even with a rapid easing of restrictions and global recovery, Nigeria is unlikely to escape a deep economic recession. We conclude that, while food systems were exempt, they were not immune to the effects of COVID-19. Protecting food supplies should be a priority alongside government efforts to address the health consequences of the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Economic impacts, Agri-food system, Poverty, Nigeria

1. Introduction

After spreading through East Asia, Europe, and North America in early 2020, the COVID-19 global pandemic started affecting countries in Africa and Latin America. With the largest population in Sub-Saharan Africa, and long-standing travel and trade links within Africa and to the rest of the world, it seemed inevitable that the pandemic would eventually reach Nigeria. In late February, Nigeria recorded the subcontinent's first confirmed case, after which it began to spread throughout Lagos, Ogun State, and the Federal Capital Authority (FCT) area of Abuja. The arrival of the pandemic set off a chain of policy actions, including public health and education campaigns, fiscal and monetary measures, restrictions on large sections of the economy, and compensating measures in the form of social protection for poor and vulnerable people (Onyekwena and Amara Mma, 2020). The sudden onset of the pandemic and the scale of policy responses imposed significant economic costs on Nigeria's population, but the nature of the impacts on food systems and the poor remains unclear.

This chapter provides an initial assessment of the economic impacts of COVID-19 and the immediate social distancing policies adopted to curb the spread of the virus in Nigeria. A simulation-based evaluation is conducted using an unconstrained multiplier model based on data from a 2018 social accounting matrix (SAM). Simulations are informed by an assessment of sectoral impacts based on reviews of official data and policy announcements, interviews with key informants including representatives of government agencies, the private sector and industry groups, and development practitioners working in Nigeria.

In our analysis, major economic impacts are caused by external shocks (e.g., weakening global demand for oil and a global economic recession) as well as domestic policies adopted to reduce viral transmission (i.e., enforced social distancing). Four major impact channels are considered, including: (i) government revenue shortfalls; (ii) reduced foreign remittances; (iii) direct impacts from a 5-week “lockdown” policy that restricted movement of people and economic activities within the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Abuja, and Kano, Lagos, and Ogun States, as well state-level lockdowns lasting 8 weeks in Akwa Ibom, Borno, Ekiti, Kwara, Osun, Rivers, and Taraba States; and (iv) indirect impacts of the lockdown policies on the rest of the country outside of the affected sectors or areas.

Economic impacts are assessed in terms of their effects on national gross domestic product (GDP), agri-food system GDP, and the number of people living below the international US$1.90-a-day poverty line. We estimate that national GDP declined sharply during the country's lockdown period, and that Nigeria will experience recession during 2020. More specifically, the lockdown policies reduced Nigerian GDP by US$11 billion or 23% during the 8-week period. Depending on the nature of economic recovery in the second half of 2020, we estimate that GDP will be between 6% and 9% lower compared to the levels of GDP there were expected during 2020 prior to the onset of COVID-19. Our estimated contraction of the economy is consistent with global projections (see IMF, 2020b; World Bank, 2020a), although these tend to fall close to our more optimistic scenarios. Despite being exempted from many of the government's lockdown policies, we estimate an 11% decline in agri-food system GDP (US$1.6 billion). We also estimate a temporary 9% point increase in the national poverty headcount rate, implying that there were 17 million more people living below the poverty line during the 8-week lockdown period—some of whom remain poor at the end of 2020.

In addition to posing a major health challenge for developing countries, COVID-19 is having severe socioeconomic impacts. For Nigeria's economy, an immediate concern was the sharp drop in oil prices, which threatened to undo years of moderate economic growth in Nigeria and many other oil-dependent African countries (IMF, 2020a). Nigeria's economy continues to suffer from oil dependence and vulnerability to oil price volatility (Arndt et al., 2018; FGN, 2020b). The economy recently emerged from a 2016 recession driven by a 2014–15 fall in oil prices. The 2016 recession was the first in 25 years, and while painful, it amounted to a relatively manageable contraction of about 1.6% of GDP (World Bank, 2019). An economic slowdown from the plunge in oil prices alone would have been damaging, but it is now clear that the continued spread of the pandemic and the associated policy responses across the globe, and within Nigeria, are likely to have severe consequences for Nigeria's economy and population.

Given these adverse outcomes, a pressing economic policy concern is to find ways to reduce the negative consequences of lower household income, higher poverty, and the greater likelihood of associated long-term impacts, such as deeper rates of malnutrition. In the short-term, while the focus has been on health, security, and the welfare of vulnerable population groups, the government has provided food from the national grain reserve and advanced payments of conditional cash transfers (FAO, 2020; FGN, 2020a; Nnabuife, 2020). Our findings suggest that not only are these measures important, but additional measures may be required, especially for urban lower-middle-income and rural nonfarm households. Our findings also indicate the need to consider, over the medium term, measures such as reopening Nigeria's borders, at least partially, to food imports to meet rising demand. Finally, looking toward longer-term strategies, our findings confirm that diversifying Nigeria's economy remains imperative—to reduce its dependence on oil extraction as the main source of growth (Arndt et al., 2018). Improving the resilience of agricultural production is one way of ensuring that future crises have a more limited impact on the health and well-being of Nigerians.

The chapter first provides a timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy responses in Nigeria (Section 2). The expected direct impacts of lockdown policies are then described (Section 3), before outlining the simulation methodology (Section 4). The results of the simulation analysis, for both lockdown and immediate recovery periods, are then presented (Section 5) and we conclude with a discussion of their implication for future policy priorities.

2. Nigeria's COVID-19 outbreak and responses

Fig. 1 shows average daily increases in confirmed COVID-19 infections in Nigeria, and provides a timeline of major policy responses, especially at the federal level of government. The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Nigeria was detected in a traveler who arrived in Lagos from Europe on February 27, 2020 (NCDC, 2020). In response, the government invested in preparedness measures, including a US$27 million increase in funding for the Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC) to strengthen laboratory testing and isolation capacity (IMF, 2020a). The government also launched public education campaigns emphasizing handwashing, maintaining physical distance from people, and avoiding large gatherings.

Fig. 1.

Daily new infections and major lockdown policy responses (27 February–3 September). Notes: Seven-day rolling average of confirmed daily new cases.

Source: Authors' compilation based on case tracking by the NCDC and policy announcements by the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN (Federal Government of Nigeria), 2020a. Address by his Excellency Muhammadu Buhari, President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, on the COVID-19 Pandemic, 29th March 2020. FGN, Abuja, Nigeria; FGN (Federal Government of Nigeria), 2020b. Address by his Excellency Muhammadu Buhari, President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, on the Extension of the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown, State House, Abuja, Monday, 13th April 2020. FGN, Abuja, Nigeria; FMBNP (Federal Ministry of Budget and National Planning), 2020. Ministerial Press Statement on Fiscal Stimulus Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic & Oil Price Fiscal Shock. FMBNP, Abuja, Nigeria. Downloaded on April 16th 2020 from https://statehouse.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/HMFBNP-Final-Press-Statement-on-Responding-to-the-COVID-19-06.04.2020-v.7.docx-1.pdf; IMF (International Monetary Fund), 2020a. Policy Responses to COVID-19 Policy Tracker. IMF, Washington, DC. Downloaded on May 15th 2020 from https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19#N; NCDC (Nigeria Centre for Disease Control), 2020. First Case of Corona Virus Disease Confirmed in Nigeria. NCDC, Abuja, Nigeria. Downloaded on March 30th 2020 from https://ncdc.gov.ng/news/227/first-case-of-corona-virus-disease-confirmed-in-nigeria).

The government's response was coordinated by a Presidential Task Force, established in early March (Ameh, 2020), that worked closely with the NCDC. The NCDC was made responsible for public health campaigns and for overall management of the testing, isolation, and treatment of patients. Nigeria's government was quick to recognize the potential scale of COVID-19's economic costs and was among the first developing countries to announce fiscal and stimulus measures to cushion economic impacts. These measures included reducing government spending in anticipation of lower revenues, and providing US$130 million to support households and small and medium-scale enterprises (FMBNP, 2020).

More importantly, Nigeria's government was among the first on the subcontinent to enforce social distancing. All schools in the country were closed in mid-March, and several states and local authorities instituted bans on public and social gatherings. After a second case was confirmed in Lagos, Nigeria instituted bans on foreign travelers from 13 “highly-infected” countries and stopped issuing visas on arrival. By late-March, with 44 confirmed cases, the government closed its land and air borders to all travelers for an initial period of 4 weeks, and suspended all passenger rail services (Ogundele, 2020).

On 29 March, President Buhari announced specific restrictions for Lagos, FCT, and Ogun States, which together contain 14% of Nigeria's population. These “lockdown” measures restricted the movement of residents outside of their homes. They also closed many business operations, as well as the borders linking the lockdown states to the rest of the country. Passenger air travel was also suspended nationwide (FGN, 2020a). Shortly afterwards the Presidential Taskforce issued exemptions for medical services, agricultural activities, food manufacturers and retailers, telecommunications, and certain financial services (PTF, 2020). The president also announced some palliative measures, mainly food distribution and a 2-month advance payment of the conditional cash transfers made by the government to vulnerable citizens. On 13 April, President Buhari announced a 2-week extension of the federal lockdown policies, which were also expanded to include Kano state.

Although it was the federal government that directed lockdown measures in four states, numerous other states implemented their own lockdown policies, sometimes predating the federal policies. States with significant social distancing measures included Akwa Ibom, Borno, Edo, Ekiti, Kwara, Taraba, Niger, Ogun, Ondo, Oyo, and Rivers. These lockdowns generally started with school closings, limited trading hours in informal markets, and restrictions on large social gatherings, including religious and sporting events. Restrictions were gradually expanded until they largely resembled the federal lockdowns (e.g., stay-at-home orders and the closing of businesses and state borders).

By the end of April, the group of states under lockdown measures accounted for almost two-thirds of the national economy. Under growing pressure to relax restrictions, the President announced that lockdowns would be eased in Lagos, FCT and Ogun states starting from around mid-May, but that the lockdown in Kano would be extended until early June. During June, and despite continued increases in daily cases, the government lifted restrictions on domestic airlines and interstate travel and allowed schools to reopen for graduating students. The number of new cases peaked at the end of June and fell during July and August. On 3 September, the government lifted all remaining restrictions on local markets.

3. Expected impacts of lockdown policies

To gauge the expected impacts for Nigeria, we interviewed key informants including government officials, private sector actors, and development partners.a We also reviewed news reports, public announcements, and security updates related to COVID-19. This review revealed that the COVID-19 impact is transmitted via three major impact channels, with potentially significant adverse effects on household incomes, demand for goods and services, and the economy's output in 2020.

The first major impact channel is the expected shortfall in federal budget revenue due primarily to the plunge in oil prices. Likewise, on the expenditure side, there are substantial unanticipated spending needs associated with COVID-19 in the form of increased health costs, new stimulus packages for businesses, and increased social support for vulnerable households. The second channel is the expected decline in private remittances into Nigeria as COVID-19 affects the well-being of Nigerian workers living abroad and remitting income back home. The third channel is the impact of domestic policies that restrict movement of people and business activities, particularly in the lockdown zones of Abuja FCT, Lagos, and Ogun States. These measures imposed, simultaneously, a demand-side shock as people were only permitted to buy essential goods and a supply-side shock as only essential businesses were permitted to operate. We consider each of these impact channels in more detail below.

3.1. Oil revenues and the government budget

With the pandemic expected to continue for most of 2020, the global economic slowdown will have consequences for Nigeria's oil-dependent economy. Air and ground travel have effectively come to a halt in most parts of the world, and oil prices have fallen by 45% to around US$30 per barrel in the first quarter of 2020 (Akanni and Gabriel, 2020). A direct consequence for Nigeria's federal government is a sharp decline in revenues. Oil revenues contribute more than 60% of government revenues, and projected revenues for 2020 were based on a benchmark oil price of US$57 per barrel (BudgIT, 2020; CBN, 2020; PWC, 2020). The Ministry of Finance, Budget, and National Planning (MFBNP) estimated that, due to COVID-19, government's monthly oil receipts would decline from USD 2.3 billion to around US$1 billion by September 2020 (FMBNP, 2020).

Apart from a revenue shortfall, the federal government also faced significant pressures to raise spending in areas not previously budgeted for, including US$300 million toward disease preparedness and response and stimulus payments of US$700 million (CBN, 2020). The government undertook a significant budget revision (FMBNP, 2020; PWC, 2020), and announced that revenue shortfalls would lead to cuts to capital spending rather than recurrent spending and social transfers (Onyekwena and Amara Mma, 2020). The government also applied for new loans from the African Development Bank, Islamic Development Bank, the IMF, and the World Bank (FMBNP, 2020).

3.2. Private remittances

Nigeria is the largest recipient of foreign remittance incomes in Sub-Saharan Africa, and these comprise about 5% of Nigerian GDP (Nevin and Omosomi, 2019; World Bank, 2018, World Bank, 2019). The Economist (2020) reports that Nigeria relies on “major lockdown economies,” such as Britain, France, Italy, Spain, and the United States of America, for 54% of remittance incomes. Remittances from these countries declined dramatically in early-2020; for example, some payments companies in Europe reported declines of 80–90% in remittance payments to Africa. The World Bank (2020b) provides a longer-term perspective, predicting that remittance flows into Nigeria will decline by 25% this year due to COVID-19. This is at the upper-end of the 5–25% range decline anticipated by Kuhlcke and Bester (2020) based on an analysis of remittance flows during past crises, although they warn that the high proportion of remittances coming through informal channels makes it difficult to assess the true impact.

Remittances are also not evenly distributed across different socioeconomic groups. The Nigeria SAM used in our analysis reveals that net foreign remittance incomes (remittances payments are only about 1.5% of remittance receipts) account for 6.1% of consumption expenditure in Nigeria. However, remittance receipts account for a much larger share of consumption expenditure for urban households (9.6%) than rural households (2.7%), and a staggering 98.7% are to nonpoor households. As such, the expectation is that remittance income shocks will have mostly affected the well-being of nonpoor and urban-based consumers.

3.3. Domestic lockdown measures

The third major impact channel includes the direct effects of policies adopted to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, specifically the 5-week restrictions on movement and economic activity imposed by the federal government on the Abuja Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Lagos State, and Ogun State, as well as the extended lockdowns in other states, such as Kano. These restrictions directly reduce economic output and household incomes for a large share of the residents who are unable to work and earn an income. Consumer demand is also curtailed directly through measures that prevent consumers from spending money on non-essential goods and services.

Lockdown measures were not applicable to sectors considered “essential.” The federal government issued exemptions for medical services provided by public and private hospitals and pharmacies, food retail in markets during restricted hours, supermarkets and grocery shops, and prepared foods for delivery.b The policies allowed farms, food and drug manufacturers, and food distributors to continue their activities. Other services considered essential, and therefore exempt, included fuel stations, private security companies, and limited financial services to maintain cash availability and to allow for online transactions. Public utility services, news companies, and telecommunications providers were also exempted.

Sectors or subsectors that were not exempt from the lockdown measures were significantly affected. The impact on a sector or subsector at the national level depends on the share of productive activities that take place within the lockdown zones. Likewise, the immediate overall impact on the national economy depends on the importance of the sector in terms of its share of GDP or employment. We conclude this section by describing some of the anticipated effects of lockdown measures on different subsectors.

Manufacturing: Many nonfood manufacturing activities were suspended during the lockdown period and in the lockdown zones. The Lagos and Ogun State industrial clusters account for about 60% of manufacturing in Nigeria, according to some estimates, and the Apapa Port in Lagos serves as the point of entry for primary and intermediate manufacturing inputs. As such, we anticipate a major negative shock for the manufacturing sector. Affected industries include manufacturers of cement, basic and fabricated metals, plastics, glass, and furniture products. While port and cargo operations were exempted from movement restrictions, port operators and manufacturers still reported that the lockdown almost immediately resulted in a backlog of containers and increased congestion at the port, as interstate movement restrictions and fear of harassment led to reduced trucking services. Moreover, although manufacturers of food, drugs, pharmaceuticals, among others, were exempted from restrictions, anecdotal evidence suggests that security concerns and supply chain disruptions resulted in companies operating below capacity.

Construction: There were no exemptions for private or public construction works in the affected areas. Moreover, movement restrictions, locally imposed curfews, and state border closures affected construction activity outside of the affected areas as well due to difficulties in obtaining important inputs such as cement or other building materials. We therefore a modest, but nationwide, decline in the construction activity as a result of domestic policies.

Transportation, storage, and cargo handling: With the nationwide closure of bus services, passenger rail services, and phone-based taxi services, the movement restrictions curtailed most ground transportation in the affected areas. Transportation was limited to essential trips for food or medicines or to seek medical treatment. Although port cargo handling, air cargo services, and associated services, such as storage and warehousing, continued to operate, insecurity and fear of harassment on transport routes reduced operations for exempted services.

Hotels, catering, and food services: COVID-19 policy responses severely affected the business of hotels, restaurants, and catering services. Movement restrictions included bans on visiting restaurants. The lack of a “food delivery culture” in Nigeria implied a near-total shutdown of urban food services during the lockdown period.

Repair services: The bulk of repair services are carried out either in repair shops in markets as part of Nigeria's large informal sector, or by itinerant repair workers. This sector suffered severely from restricted movement and the closure of market centers.

Domestic workers and other personal services: Domestic workers (e.g., cooks, childcare providers, cleaners, gardeners, private security guards etc.) form a large share of the working population within the lockdown zones. While some domestic workers reside at their places of work, those who live outside were no longer able to commute to work. We estimated that about half of these workers are live-in workers and will continue to work and earn a living during the lockdown period.

4. Simulating economic impacts

4.1. Multiplier analysis

SAM multiplier models are often used to measure the direct and indirect impacts of rapid-onset economic shocks, such as those caused by COVID-19. At the heart of the multiplier model is a SAM, which is an economywide database that captures all income and expenditure flows between all actors in an economy. The SAM captures the structure of the economy at a given point in time, showing the relationships between producers (i.e., activities), consumers (i.e., households), government and the rest of the world. It tracks how these economic actors interact in markets for products and factors of production (i.e., land, labor and capital). The multiplier model used to estimate the impacts of COVID-19 in Nigeria is calibrated to a 2018 SAM that separates the economy into 86 sectors/products and 15 household groups. Although the SAM has a 2018 base year, the multiplier model's results are scaled to match national accounts, household income, and population data for 2019 to allow for an assessment of the absolute size of COVID-19 impacts in 2020 (relative to baseline values).

The SAM multiplier model provides a mechanism for estimating the effects of an external shock, typically an exogenous change in final demand for goods and services on total supply of different commodities. By capturing input-output and employment relationships, as well as the functional distribution of income, the model also generates results on domestic production, employment, and changes in household incomes. Final demand in our model includes government consumption demand, investments, and exports. It is also treats household consumption demand as exogenous, meaning that an income shock does not result in subsequent rounds of consumption demand and income feedbacks. This avoids over-estimating multiplier effects and allows us to directly simulate changes in household consumption where appropriate (e.g., for evaluating the impacts of declining foreign remittances).

A important assumption of our multiplier approach is that, over the short-run, technical input-output relationships, output choices of producers, and consumption patterns of households do not change in response to simulated shocks, and that prices are fixed. General equilibrium models are often considered superior to fixed-price models, because they capture price-mediated competition in markets for scarce resources. However, in the case of COVID-19 lockdowns, where trade and production have ceased due to government directives, rather than by market forces, a SAM multiplier framework is the more appropriate method for measuring impacts, at least for short-run analysis. For more on SAM multiplier models, see Breisinger et al. (2009).

4.2. Simulation design

As explained, the economic impacts of COVID-19 restrictions are simulated through exogenous changes in the final demand component of those sectors affected by policy measures or external shocks. A summary of the shocks, separated into different domestic channels and global shocks, is presented in Table 1 , with further details provided in Table A1 in the Annex. The impact channels in the table coincide with the three major channels described in Section 3 (e.g., reductions in oil exports and remittances). The channel capturing the effects of domestic lockdown policies is further disaggregated in order to differentiate the effects of specific restrictions (e.g., separating closing of hotels and restaurants from the closing of schools). Shocks in each channel result in changes in domestic supply in affected sectors, which in turn affects other sectors via input-output relationships captured in the SAM multiplier model. This in turn results in direct and indirect changes in employment, household incomes, and poverty.

Table 1.

Domestic and global impact channels.

| Channel description | Policy measure or global shock | Impact size | Affected area (type of shock) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic channels | |||

| Direct restrictions on farming | Completely exempted | None | N/A |

| Limiting mining operations | Deemed an essential sector | None | N/A |

| Closing non-essential manufacturing operations | Essential goods exempted; many non-essential operations suspended | Modest (− 20%) | Selected cities/states (household demand) |

| Disruptions to energy and water supply | Completely exempted | None | N/A |

| Limiting construction activities | Partially exempted | Modest (− 15%) | National (investment demand) |

| Closing non-essential wholesale/retail trade | Trade of essential goods exempted; markets for non-essential goods closed or trading times limited | High (− 25%) | Selected cities/states (domestic supply) |

| Transport/travel restrictions | Interstate travel banned; urban passenger transport limited; non-essential air transport suspended | Very high (− 46%) | All states (domestic supply) |

| Closing hotels, bars and restaurants | Complete shutdown, but with informal sector enforcement gaps | Very high (− 80%) | All states (household demand) |

| Closing non-essential business services | Essential services exempted; non-essential businesses operate under work-from-home conditions if possible | Modest (− 19%) | Selected cities/states (domestic supply) |

| Government work-from-home orders | Civil service, public defense and security remained open | None | N/A |

| Closing all schools in the country | All public schools closed, with limited scope for online learning | High (− 40%) | Selected cities/states (domestic supply) |

| Disruptions to hospitals and clinics | Completely exempted | ||

| Banning sports and other entertainment | Most sports and entertainment banned; media activities still operated; religious and public gatherings suspended | High (− 40%) | All states (domestic supply) |

| Domestic work and other services | Most personal services (e.g., hairdressing) restricted or affected | High (− 29%) | Selected cities/states (domestic supply) |

| Global and other shocks | |||

| Lower export demand | Global demand and prices for oil and other commodities falls, but some production continues | High (− 10% to − 50%) | All export products (export demand) |

| Fewer international tourists and travelers | Closed borders and reduced demand for tourism (i.e., hotels, international travel) | Very high (− 75%) | Hotels, travel services (export demand) |

| Falling foreign remittances | Declining remittances sent by nationals working abroad | High (− 25%) | Household incomes (household demand) |

| Falling government revenues | Fall in government revenues, offset by reduced public capital investment | Low (− 3%) | Construction activities (investment demand) |

| Falling foreign direct investment | Fall in foreign capital inflows reduces total investment spending | High (− 50%) | Construction activities (investment demand) |

Whereas some of the COVID-19 restrictive measures, such as school closures, limits on the size of gatherings, and restrictions on intercity or interstate passenger travel are imposed nationwide, most lockdown measures are imposed in specific states. Therefore, where required, initial demand shocks are weighted to reflect this geographical targeting. Nigeria lockdown measures were instituted at two levels of government. Those imposed early on by the federal government affected Lagos, FCT-Abuja, Ogun, and Kano. These states account for about 40% of national GDP, and lockdown measures lasted for 5 weeks from 30 March until 4 May. Others were imposed by state governments independently of the federal government (see Section 2). These states account for around 25% of GDP, and lockdowns remained in force for about 8 weeks. Our results focus on the economic impacts during the combined 5- and 8-week lockdowns across the various affected states.

Following the lockdown, policy measures can either be lifted gradually or rapidly. Depending on how firms and consumers react, the recovery may therefore also be slower or faster. Evidence elsewhere has shown that even as restrictive measures are relaxed, economies often take time to return to a business-as-usual state. Therefore, beyond the lockdown period, we model and present a second set of results under various recovery scenarios. These inform revised growth paths for the Nigerian economy starting from the lockdown period in the second quarter (Q2) and extending through the third and fourth quarters (Q3 and Q4). As shown in Table 2 , we consider fast, gradual, and slower recovery scenarios. In each of these, we assume no shocks during the pre-COVID-19 period (January and February), followed by the introduction of lockdowns and external or global shocks in March. Toward the end of Q2, the lockdown measures are lifted either rapidly or gradually, which we simulate as a decline in the extent of the policy shock imposed during the lockdown period (e.g., if a 30% reduction in consumer demand was simulated during the lockdown, then that shock is reduced by 60% in June under the fast recovery scenario, i.e., the lingering effect of lockdown is a 12% reduction in consumer during that month).

Table 2.

Domestic policy and external shocks during lockdown and recovery scenarios.

| Domestic policy shocks |

Global shocks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster easing and recovery | Gradual easing and recovery | Gradual easing with slower recovery | |||

| Q1 | Jan | No lockdown restrictions or global shocks during pre-COVID-19 period | |||

| Feb | |||||

| Mar | 5-week lockdown for all states (late-March to early June) | 5-week lockdown for early states until early June (e.g., Lagos), and 8-week lockdown for late states until mid-June (e.g., Kano) | Exports, FDI and remittances fall from 1st March onwards | ||

| Q2 | Apr | ||||

| May | |||||

| Jun | Losses reduced 60% | Losses reduced 50% | Losses reduced 40% | ||

| Q3 | Jul | Losses reduced 90% (transport and arts/sports by 70%) | Losses reduced 80% (transport and arts/sports by 60%) | Losses reduced 70% (transport and arts/sports by 50%) | Shocks reduced 70% (60% in gradual or slower recovery) |

| Aug | |||||

| Sep | |||||

| Q4 | Oct | Losses reduced 99% (transport and arts/sports by 90%) | Losses reduced 95% (transport and arts/sports by 70%) | Losses reduced 80% (transport and arts/sports by 60%) | Shocks reduced 99% (70% in gradual or slower recovery) |

| Nov | |||||

| Dec | |||||

Notes: FDI is foreign direct investment. Early lockdown states include Lagos, FCT and Ogun. Late lockdown states include Akwa Ibom, Borno, Edo, Ekiti, Kwara, Taraba, Niger, Ogun, Ondo, Oyo, and Rivers.

Source: Authors' compilation.

Overall, the fast recover scenario assumes that almost all (99%) of the economic shocks during the lockdown period have dissipated by Q4, whereas the slow recovery scenario assumes that about a fifth of the shock still remains at the end of the year. While is difficult to predict actual outcomes, especially given the possibility of “second waves” of infections in Nigeria and abroad, our tree scenarios provide a reasonable range of possible outcomes under more or less optimistic assumptions.

5. Estimated impacts

5.1. Economic costs of the lockdown

We first consider economic impacts during Nigeria's lockdown period. Table 3 shows the impact on aggregate GDP and its main components. The largest losses, in absolute and relative terms, are recorded in the industrial (− 25.9%) and services (− 27.5%) sectors, with GDP losses in the services sector (US$7.6 billion) accounting for over two-thirds of the recorded 23.4% loss in national GDP (US$11.3 billion). Losses in the agricultural sector are small in absolute terms (US$0.7 billion), but still significant in relative terms (− 7.9%) considering that the sector was exempt from any direct restrictive measures.

Table 3.

Estimated change in GDP during lockdown period.

| GDP share in 2019 (%) | GDP change during lockdown |

Contribution to change (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | US$billions | |||

| All sectors | 100 | − 23.4 | − 11.3 | 100 |

| Agriculture | 18.1 | − 7.9 | − 0.7 | 6.5 |

| Industry | 23.6 | − 25.9 | − 2.9 | 26.1 |

| Services | 58.3 | − 27.5 | − 7.6 | 67.4 |

Source: Nigeria SAM Multiplier Results.

Table 4 provides a breakdown of the contribution of different impact channels to total GDP losses (see Table 2). This can help policymakers weigh up the economic costs and health implications of imposing or lifting restrictions in subsectors of the economy. As noted, the relative contributions of these impact channels depend on the severity of the lockdown measures, the geographical scope of the lockdown measures, the relative size of the cluster of sectors represented within each impact channel, and the economic input-output linkages between the sectors affected directly by the policy measure and other sectors. Severe restrictions imposed on non-essential wholesale and retail trade activities in the lockdown zones account for 17.5% of overall GDP losses in Nigeria during the lockdown period. The suspension of all sport, arts, and entertainment activities, together with transport restrictions, account for another fifth of total GDP losses.

Table 4.

Contribution of channels to total and agri-food GDP losses during lockdown period.

| Contribution to total GDP change |

Contribution to agri-food GDP change |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | Rank | (%) | Rank | |

| All domestic policies and global shocks | 100 | 100 | ||

| Closing non-essential manufacturing operations | 4.2 | (10) | 3.2 | (8) |

| Limiting construction activities | 9.5 | (5) | 5.4 | (5) |

| Closing non-essential trading activities | 17.5 | (1) | 24.6 | (2) |

| Transport and travel restrictions | 10.6 | (3) | 10.0 | (3) |

| Closing hotels, bars and restaurants | 6.7 | (7) | 29.7 | (1) |

| Closing non-essential business services | 6.1 | (9) | 1.5 | (11) |

| Closing all schools in the country | 6.7 | (8) | 2.4 | (9) |

| Banning sports and other entertainment | 11.4 | (2) | 2.3 | (10) |

| Limits on domestic workers and other services | 7.3 | (6) | 1.5 | (12) |

| Lower export demand | 9.7 | (4) | 5.1 | (6) |

| Falling foreign remittances | 4.2 | (11) | 8.0 | (4) |

| Falling government revenues | 2.0 | (13) | 1.1 | (13) |

| Falling foreign direct investment | 1.8 | (14) | 1.0 | (14) |

| Fewer international tourists and travelers | 2.3 | (12) | 4.3 | (7) |

Source: Nigeria SAM Multiplier Results.

Although primary agricultural activities were excluded from direct restrictions imposed in the lockdown zones, the agricultural sector is still affected indirectly, with agricultural GDP falling 7.9% (Table 3). These unintended effects of policies highlight the importance of using a model framework that captures inter-industry linkages and measures indirect effects. To better understand some of the linkages between agriculture and the rest of the economy, it is useful to consider the effects of COVID-19 throughout the agri-food system. Table 5 shows that the agri-food system accounts for 32.6% of GDP in Nigeria, and consists of primary agriculture (21.0%), agro-processing (4.0%), food services, such as hotels and restaurants (0.9%), and food and agriculture-related trade and transport services (6.7%).

Table 5.

Estimated change in agri-food system GDP during lockdown period.

| GDP share in 2019 (%) | GDP change during lockdown |

Contribution to change (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | US$ billions | |||

| All sectors | 100 | − 23.4 | − 11.3 | 100 |

| Agri-food system | 32.6 | − 11.1 | − 1.6 | 14.4 |

| Agriculture | 21.0 | − 7.9 | − 0.7 | 6.5 |

| Agro-processing | 4.0 | − 16.5 | − 0.3 | 2.9 |

| Food-related trade and transport | 6.7 | − 10.0 | − 0.3 | 2.9 |

| Food services | 0.9 | − 83.6 | − 0.3 | 2.2 |

| Rest of the economy | 67.4 | − 28.8 | − 9.6 | 85.6 |

Source: Nigeria SAM Multiplier Results.

Agri-food GDP declines 11.1% or US$1.6 billion. Just less than half of these losses occur within the agricultural sector. Although food processing is exempt from restrictions, losses in the agro-processing sector are large (16.5%) due to restrictions imposed on non-essential manufacturing or services sectors that demand agro-processing products. Food and agricultural trade and transport services decline by 10% and in monetary terms contributes about the same (US$0.3 billion) to overall agri-food GDP losses. The near-total shutdown of hotels and restaurants within the lockdown zones also means the food services sector declines substantially (i.e., by 83.6% during the lockdown period). However, food services are a relatively small component of the overall agri-food system and so their contribution to the overall decline in agri-food GDP is similar to agro-processing and food trade and transport (i.e., US$0.3 billion).

A breakdown of agri-food GDP losses by impact channel reveals that the suspension of non-essential wholesale and retail trade and the closure of hotels, bars, and restaurants jointly account for over half of all losses (see Table 4). The large impact from closing hotels, bars, and restaurants is particularly noteworthy. Despite the small size of the food services sector itself, it has significant linkages to other subsectors within the agri-food system, thus explaining the large overall impact within the agri-food system. As expected, with a possible exception of transport restrictions, most other policy measures have a limited impact on agri-food GDP.

We next turn to household income losses suffered during the lockdown period. Lockdown measures affect household incomes via employment income changes and falling foreign remittances. As such, households with stronger ties to the (formal) labor market, and especially those sectors directly affected by lockdown measures, are affected more. These tend to be wealthier, urban-based households. Similarly, as discussed before, most remittance incomes are earned by nonpoor urban households. It is therefore not surprising, as shown in Fig. 2 , that income losses suffered by nonpoor households, i.e., those in the top three quintiles, are significantly higher (23.8%) than those in the poorer bottom two quintiles (15.3%). Urban and rural nonfarm households also experience much higher income losses (26.9% and 23.7%, respectively) compared to rural farm households (16.4%).

Fig. 2.

Estimated change in household incomes during lockdown period. Notes: Quintiles are defined based on per capita consumption spending. Rural nonfarm households do not any income from farming land themselves.

Source: Nigeria SAM Multiplier Results.

Finally, Fig. 3 reports poverty effects during the lockdown period. In generating poverty estimates, we assume that a production slowdown translates into a decline in employment income. In reality, some employers continued to pay workers during the lockdown and/or households were able to draw on savings to sustain consumption. As such, our result may overstate the actual experience of being poor from the perspective of people's ability to access food and essential items. We find that the national rate of poverty increases 8.7% points from a base of 43.5%, which equates to 17 million more people falling below the poverty line during lockdown. Although the percentage point increase in poverty is higher for urban than for rural households, rural households account for a larger share of the population, and hence the majority of people that fall into poverty during the lockdown period.

Fig. 3.

Estimated change in poverty during lockdown period. Notes: Poverty headcount rate is defined as the share of the national population with per capita consumption levels below the international U$1.90-a-day poverty line.

Source: Nigeria SAM Multiplier Results.

5.2. Easing of restrictions and recovery scenarios

The results presented above focused on the shocks experienced during Nigeria's lockdown. We now consider the potential annual impacts of COVID-19 that assumes either a rapid or slower easing of restrictions and recovery during the rest of the year (see Table 2). Results are reported by quarter (i.e., Q1–Q4). Q1 was mostly exempt from shocks; in Q2 we record the largest economic losses due to lockdown measures being fully enforced; and in Q3 and Q4 the economy starts to recover as lockdown measures are lifted and global shocks are assumed to decline in severity.

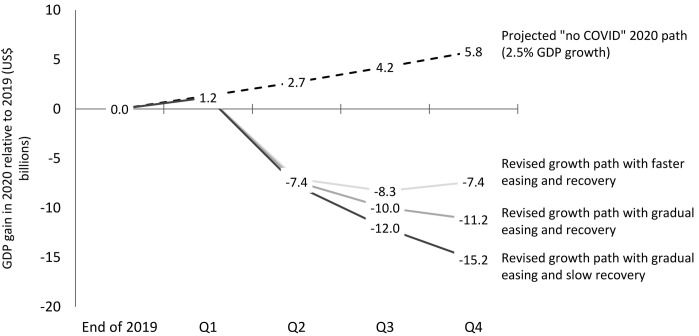

GDP losses relative to the baseline are shown in Fig. 4 . Since the federal and state lockdowns are mainly implemented in Q2, Q1 losses are minimal. However, average GDP losses in Q2 range from 17.0% to 18.2%. This range results from uncertainty over the pace of recovery during June, after some of the lockdown measures were lifted. Also for this reason, the average quarterly loss is less than the loss experienced during the actual lockdown period (see Fig. 2). Under the rapid recovery scenario losses are 4.4% and 1.0% in Q3 and Q4, respectively. By contrast, under the slow recovery scenario losses remain high, i.e., 9.3% and 7.4% in Q3 and Q4. The weighted average deviation from the baseline GDP ranges from − 5.5% to − 8.8% for the year.

Fig. 4.

Estimated change in quarterly and annual total GDP during 2020 (relative to baseline). Notes: Baseline is the GDP expected in 2020 in the absence of COVID-19's economic impacts.

Source: Nigeria SAM Multiplier Results.

An alternative way of presenting these GDP results is to compare it against the projected GDP growth path for 2020. Assuming real GDP would have grown 2.5% in 2020, the economy would have gained around US$1.3 billion per quarter for an annual gain of US$5.8 billion (see Fig. 5 ). However, with the outbreak of COVID-19 and associated policies and external shocks, this growth path needs to be revised. As shown in the figure, under our various scenarios, the cumulative loss in GDP is now expected to range from US$7.4 to US$15.2 billion this year. This equates to year-on-year real GDP growth rates of − 3.0% to − 5.3% in 2020.

Fig. 5.

Projected cumulative total GDP losses during 2020 (relative to 2019).

Source: Nigeria SAM Multiplier Results.

Lastly, we consider quarterly poverty rates in Fig. 6 . As expected, there is a large spike in poverty during Q2 when most of Nigeria's lockdown measures were in place. However, poverty rates are expected to fall significantly in Q3 and Q4. Under the fast recovery scenario, the poverty rate is only 0.3% points above the baseline rate by Q4, whereas under the slow recovery scenario the rate is still expected to be 2.2% points above the baseline by Q4. The latter equates to 4.3 million additional poor people by the end of the year. Even though poverty may eventually return to baseline levels, millions of people still suffer severe deprivation during Q2 and Q3 and may require government support. Future analysis should consider the mitigating effects of such government household support programs.

Fig. 6.

Estimated change in poverty headcount rate during 2020 (relative to baseline). Notes: Poverty headcount rate is defined as the share of the national population with per capita consumption levels below the international U$1.90-a-day poverty line.

Source: Nigeria SAM Multiplier Results.

6. Conclusions

The scale and speed at which COVID-19 has spread across the globe, and the rapid adoption of wide-ranging policy measures to contain the disease, have combined to produce sudden and severe economic shocks. In this paper we measured the impacts of the shocks from COVID-19 and the policies adopted to curb the spread of the virus in Nigeria. Using a SAM multiplier model for Nigeria, with simulations informed by key informant interviews, we estimate that Nigeria's GDP suffered a 23.4% loss, amounting to US$11.3 billion, with two-thirds of the losses occurring in the services sector. The agri-food system, which is the primary means of livelihood for most Nigerians, suffered a 11.1% loss in output (US$1.6 billion). Although food and agricultural activities were excluded from direct restrictions imposed in the lockdown zones, the agricultural sector was affected indirectly via its linkages to the rest of the economy.

COVID-19 infections are still rising in Nigeria, and federal, state, and local policies are evolving to respond to the disease and to minimize the economic impacts. Therefore, policymakers at all levels need more evidence to assess economic impacts and weigh policy options. This is especially important as Nigeria moves from lockdown policies to policies aimed at promoting economic recovery, while also ensuring that measures are in place to mitigate further spread. The approach and findings presented here provide an early assessment of economic costs. Further and more sophisticated economywide analyses are needed to evaluate policy options, especially as the initial economic shocks subside and markets begin to function again. Nevertheless, based on an initial assessment, conclusions can be drawn to guide Nigeria's policymakers, researchers, and development practitioners about COVID-19.

First, we have shown that, when considering impacts on agriculture, it is important to take an agri-food systems approach that goes beyond primary agriculture to consider subsectors such as food processing, food-related trade and transport, and food services. All of these components of the agri-food system have strong linkages to the rest of the economy and, therefore, suffer severe shocks when restrictions are placed on other sectors, such as manufacturing, education and tourism. In the case of COVID-19, most shocks originate from the consumer's “plate” and pass back through to the “farm” where they are likely to affect the livelihoods of both smallholder and larger-scale farmers. Agencies implementing policies aimed at supporting agriculture during the COVID-19 and recovery period should consider disruptions to and policy support for the broader agri-food system.

Second, this study finds a temporary, but substantial increase in the national poverty rate of 8.7% points due to COVID-19, and that households lost almost a quarter of their incomes on average during the lockdown period. During this time, 17 million more people fell into poverty in Nigeria—a country that already accounted for the highest absolute number of poor people in Sub-Saharan Africa before the COVID-19 crisis. Considering that the policies under examination in this paper were mainly lockdowns in the relatively wealthier southwestern parts of the country and in the capital city, Abuja, we might expect poverty impacts to increase during 2020 as COVID-19 spreads to other regions where poverty rates are higher, such as the northeast, especially if further targeted lockdowns are implemented.

The estimated poverty impacts due to COVID-19 are mainly due to reductions in employment income. Therefore, minimizing and reversing these estimated poverty impacts calls for policy approaches to protect small and medium-scale enterprises during the recovery period. In the short-term mitigating poverty requires targeted support for sustaining household incomes, such as cash transfers and other social protection measures. In the medium term, the real sector pillar in the government's strategy for recovering from COVID-19 relies on rapid employment generation in the agriculture sector (FGN, 2020b). However, the question remains how to achieve these goals, and which sectors of agricultural development would be best suited for achieving the goals? Resolving this question requires further analysis to determine priority value chains, policies, and public investments in agriculture to drive job creation. More broadly, reduced incomes and higher household poverty have consequences for food and nutrition security in Nigeria. For example, reduced household incomes make it less likely that households will purchase nutritious foods for consumption by children and women at reproductive ages.

In the long term, for post-COVID recovery policy formulation and implementation, the emerging lessons from COVID-19 crisis reinforce the existing incentives for restructuring Nigeria's economy. Nigeria's economy needs to diversify away from a dependency on oil and remittances from other economies, and toward the development of productivity-enhancing and poverty-reducing sectors, such as agriculture and manufacturing, which can generate employment and value-added. Developing the agri-food system will require investments in public goods, such as research and rural infrastructure. In this way, federal and state policies can support the recovery from COVID-19 and build a more resilient Nigerian economy.

Footnotes

Interview respondents included the Statistician-General of the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the Head of Macroeconomic Unit of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), the Director and National Monitoring and Evaluation Officer of the Federal Ministry of National Planning and Budget, and a Research Officer at the Agricultural Research Council of Nigeria (ARCN).

Some local authorities placed additional restrictions on the operations of food markets. For example, the Abuja FCT local authority limited food market openings to 4 h on just 2 days of the week.

Annex: Detailed scenario assumptions

Table A1.

Detailed lockdown scenario assumptions.

| Domestic channel | Affected sectors (ISIC sections) | Geography affected | Shock size (%) | Detailed subsectors affected by shock (ISIC codes: D = division, G = group, C = class) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct restrictions on farming | Agriculture (A) | None | 0 | Crop/animal production, hunting, related service activities (D01); forestry, logging (D02); fishing, aquaculture (D03) |

| Limiting mining operations | Mining, quarrying (B) | None | 0 | Coal, lignite (D5); crude petroleum, natural gas (D06); metal ores (D07); quarrying (D08); mining support service activities (D09) |

| Closing non-essential manufacturing operations | Manufacturing (C) | None | 0 | Food products (D10); coke, refined petroleum (D19); pharmaceuticals (D21); electromedical equipment (G266); beverages, tobacco (D11–12) |

| Selected cities and states | − 20 | Textiles, clothing, leather (D13–15); wood, paper, printing (D16–18); chemicals, rubber, plastics (D20–21); non-metallic minerals (D23); metals (D24–25); equipment, machinery (D26–28 excl. G266); vehicles, transport equipment (D29–30); furniture (D31), other manufactures (D33) | ||

| Disruptions to energy and water supply | Electricity, gas (D); water supply (E) | None | 0 | Electricity, gas, steam supply (D35); water collection, treatment, supply (D36); sewerage, waste collection/remediation (D37–39) |

| Limiting construction | Construction (F) | All states | − 15 | Construction of buildings (D41); civil engineering (D42); specialized construction activities (D43) |

| Closing non-essential trading activities | Wholesale and retail trade (G) | None | 0 | Agricultural raw materials, live animals (G462); agricultural machinery, equipment, supplies (C4653); food, beverages, tobacco, incl. stalls and markets (G463 G471–472 C4781); construction materials, hardware, plumbing, heating equipment (C4663); automotive fuels (G473) |

| Selected cities and states | − 25 | Motor vehicle trade/repair (D45); wholesale trade (D46 excl. G462–463 C4653 C4663); retail trade (D47 excl. G471–472 G47 C4781) | ||

| Transport and travel restrictions | Transportation, storage (H) | None | 0 | Postal/courier activities (D53); transport via pipeline (G493) |

| All states | − 25 | Water transport (C5011–5012 C5022); transport support (G522) | ||

| − 50 | Freight rail/road/air transport (C4912 C4923 G512); warehousing/storage (G521) | |||

| − 75 | Urban/suburban passenger/other land transport (C4911 C4921–4922); Passenger air transport (G511) | |||

| Closing hotels, bars and restaurants | Accommodation, food services (I) | Selected cities and states | − 80 | Accommodation (D55); food/beverage service activities (D56) |

| Government work-from-home orders | Public administration, defense (O) | None | 0 | Public administration, defense, compulsory social security (D84) |

| Closing all schools in the country | Education (P) | All states | − 50 | Pre-primary and primary education (G851) |

| − 35 | Secondary education (G852); Other education (G854) | |||

| − 20 | Higher education (G853); Educational support activities (G855) | |||

| Closing non-essential business services | Information, communication (J); finance, insurance (K); real estate (L); professional/scientific/technical activities (M); administrative/support services (N) | Selected cities and states | 0 | Publishing activities (D58); programming/broadcasting activities (D60); telecommunications (D61); computer programming/consultancy activities (D62); information service activities (D63); financial services, insurance, pension funding, auxiliary services (D64–66); real estate activities (D68); security and investigation activities (D80) |

| − 10 | Accounting, bookkeeping, auditing, tax consultancy (G692); head offices, management consultancy (D70); scientific research/development (D72); advertising, market research (D73); other professional/scientific/technical activities (D74); | |||

| − 25 | Legal activities (G692); architectural/engineering activities (D71); veterinary activities (D75) | |||

| − 40 | Motion picture/video/television program production, etc. (D59); renting/leasing activities (D77); employment activities (D78); travel agencies, tour operators (D79); building services, landscape activities (D81); office administrative, office support, other business support activities (D82) | |||

| Disruptions to hospitals and clinics | Human health, social work (Q) | None | 0 | Human health activities (D86); residential care activities (D87); social work activities without accommodation (D88) |

| Banning sports and other entertainment | Arts, recreation, entertainment (R) | All states | − 40 | Creative/arts/entertainment activities (D90); libraries, archives, museums, other cultural activities (D91); gambling, betting activities (D92); sports, amusement/recreation activities (D93) |

| Limits on domestic workers and other services | Other service activities (S); households as employers (T); extraterritorial organizations (U) | Selected cities and states | 0 | Extraterritorial organizations/bodies (D99) |

| − 10 | Membership organizations (D94) | |||

| − 25 | Other personal services (D96); domestic workers/personnel (D97); Other production activities of private households for own use (D98) | |||

| − 40 | Repairing computers and personal/household goods (D95) |

Notes: ISIC is the International Standard Industrial Classification. Selected cities and states include early lockdown states (Lagos, FCT and Ogun) and late lockdown states (Akwa Ibom, Borno, Edo, Ekiti, Kwara, Taraba, Niger, Ogun, Ondo, Oyo, and Rivers).

Source: Authors' estimations based on COVID-19 policy announcements issued by the Government of Nigeria (FGN (Federal Government of Nigeria), 2020a. Address by his Excellency Muhammadu Buhari, President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, on the COVID-19 Pandemic, 29th March 2020. FGN, Abuja, Nigeria; FGN (Federal Government of Nigeria), 2020b. Address by his Excellency Muhammadu Buhari, President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, on the Extension of the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown, State House, Abuja, Monday, 13th April 2020. FGN, Abuja, Nigeria; PTF (Presidential Task Force), 2020. Implementation Guidance for Lockdown Policy. Abuja, Nigeria. Downloaded on March 30th 2020 from https://statehouse.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PTF-COVID-19-Guidance-on-implementation-of-lockdown-policy-FINAL.docx-2.pdf).

References

- Akanni L.O., Gabriel S.C. Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa (CSEA); 2020. The Implication of Covid19 on the Nigerian Economy.http://cseaafrica.org/the-implication-of-covid19-on-the-nigerian-economy/ Downloaded on April 15th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- Ameh J. Punch; 2020. Covid-19: Buhari Names 12-Member Presidential Task Force to Control Spread.https://punchng.com/covid-19-buhari-names-12-member-presidential-task-force-to-control-spread/ March 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt C., Chuku C., Adeniran A., Morakinyo A., Victor A., George M., Chukwuka O. International Food Policy Research Institute; Washington, DC: 2018. Nigeria's Macroeconomic Crisis Explained. NSSP Working Paper 52. [Google Scholar]

- Breisinger C., Thomas M., Thurlow J. International Food Policy Research Institute; Washington, DC: 2009. Social Accounting Matrices and Multiplier Analysis: An Introduction With Exercises. Food Security in Practice Technical Guide. [Google Scholar]

- BudgIT 2020 Budget: Analysis and Opportunities. 2020. https://yourbudgit.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2020-Budget-Analysis.pdf Downloaded on April 15th 2020 from.

- CBN (Central Bank of Nigeria) Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN); Abuja, Nigeria: 2020. Central Bank of Nigeria Communiqué No. 129 of the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting of Monday 23rd and Tuesday 24th March 2020.https://www.cbn.gov.ng/Out/2020/MPD/ Downloaded on April 10th 2020 from. Central Bank of Nigeria Communique No. 129 of the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting held on Monday 23rd and Tuesday 24th March 2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); Rome, Italy: 2020. National Policy Responses to Limit the Impact of COVID-19 on Food Markets. Food Policy and Market Developments.http://www.fao.org/giews/food-prices/food-policies/detail/en/c/1270543/ Downloaded on April 12th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- FGN (Federal Government of Nigeria) FGN; Abuja, Nigeria: 2020. Address by his Excellency Muhammadu Buhari, President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, on the COVID-19 Pandemic. 29th March. [Google Scholar]

- FGN (Federal Government of Nigeria) FGN; Abuja, Nigeria: 2020. Bouncing Back: Nigeria Economic Sustainability Plan. [Google Scholar]

- FMBNP (Federal Ministry of Budget and National Planning) FMBNP; Abuja, Nigeria: 2020. Ministerial Press Statement on Fiscal Stimulus Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic & Oil Price Fiscal Shock.https://statehouse.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/HMFBNP-Final-Press-Statement-on-Responding-to-the-COVID-19-06.04.2020-v.7.docx-1.pdf Downloaded on April 16th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- IMF (International Monetary Fund) IMF; Washington, DC: 2020. Policy Responses to COVID-19 Policy Tracker.https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19#N Downloaded on May 15th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- IMF (International Monetary Fund) IMF; Washington, DC: 2020. Regional Economic Outlook June 2020 Update: Sub-Saharan Africa.https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/SSA/Issues/2020/06/29/sreo0629 Downloaded on July 3rd 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlcke K., Bester H. Cenfri.org; 2020. COVID-19 and Remittances to Africa: What Can We Do?https://cenfri.org/articles/covid-19-and-remittances-to-africa-what-can-we-do/ Downloaded on March 30th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- NCDC (Nigeria Centre for Disease Control) NCDC; Abuja, Nigeria: 2020. First Case of Corona Virus Disease Confirmed in Nigeria.https://ncdc.gov.ng/news/227/first-case-of-corona-virus-disease-confirmed-in-nigeria Downloaded on March 30th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- Nevin A.S., Omosomi O. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC); Lagos, Nigeria: 2019. Strength from Abroad: The Economic Power of Nigeria's Diaspora.https://www.pwc.com/ng/en/pdf/the-economic-power-of-nigerias-diaspora.pdf Downloaded on March 30th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- Nnabuife C. Tribune; 2020. COVID-19: FG Commences Process to Distribute 70,000 Metric Tons of Food Items.https://tribuneonlineng.com/covid-19-fg-commences-process-to-distribute-70000-metric-tons-of-food-items/ April 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundele K. The Punch; 2020. Updated: FG Places Travel Ban on China, Italy, US, UK, Nine Others.https://punchng.com/breaking-fg-places-travel-ban-on-china-italy-us-uk-others/ March 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Onyekwena C., Amara Mma E. Brookings Institution; Washington, DC: 2020. Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on the Nigerian Economy.https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/04/08/understanding-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-the-nigerian-economy/ Downloaded on March 30th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- PTF (Presidential Task Force) Implementation Guidance for Lockdown Policy. Abuja, Nigeria. 2020. https://statehouse.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PTF-COVID-19-Guidance-on-implementation-of-lockdown-policy-FINAL.docx-2.pdf Downloaded on March 30th 2020 from.

- PWC (PricewaterhouseCoopers) Nigeria Economic Alert: X-Raying the 2020 FGN Budget Proposal 2016–20. 2020. https://www.pwc.com/ng/en/assets/pdf/economic-alert-nov-2019.pdf Downloaded on April 15th 2020 from.

- The Economist . The Economist; 2020. Covid Stops Many Migrants Sending Money Home.https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2020/04/16/covid-stops-many-migrants-sending-money-home?fsrc=scn/fb/te/bl/ed/acashcowdriesupcovidstopsmanymigrantssendingmoneyhomemiddleeastandafrica&fbclid=IwAR3slLExKK09JPQVYjpdFjDvBGrQILB1JxCWQezRkKaky0 April 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Bank; Washington, DC: 2018. Personal Remittances, Received (% of GDP)https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS Downloaded on April 16th 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Bank; Washington, DC: 2019. Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Bank; Washington, DC: 2020. Nigeria in Times of COVID-19: Laying Foundations for a Strong Recovery. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank World Bank Predicts Sharpest Decline of Remittances in Recent History. 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/22/world-bank-predicts-sharpest-decline-of-remittances-in-recent-history Press Release. Downloaded on May 5th 2020 from.