Abstract

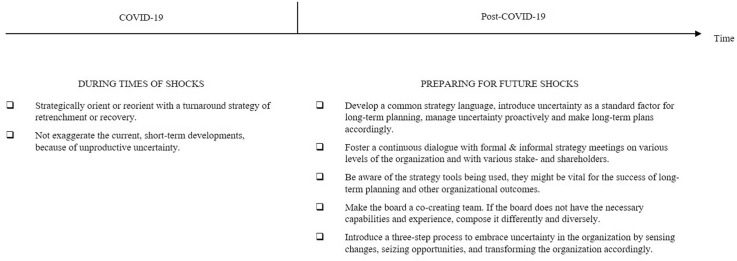

This article gives guidance to aviation managers being struck by environmental shocks. The introduced frameworks support aviation managers to think strategically during times of shocks and help them to prepare for future shocks by developing more resilient and learning organizations. Practical, short-term recommendations include strategically orienting or reorienting and not exaggerating the current, short-term developments due to unproductive uncertainty. Further, and to prepare for future shocks, the results of this study suggest that aviation managers should develop a common strategy language, introduce uncertainty as a standard factor for long-term planning, manage uncertainty proactively and make long-term plans accordingly by fostering a dialogue with various stake- and shareholders, being aware of the strategy tools in use, making the board a co-creating team and introducing a three-step process in sensing, seizing and transforming the organization accordingly.

Keywords: Air transport, Environmental shocks, Uncertainty, Strategic planning, Strategy process

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

During a shock, aviation managers should be aware of the following: 1. Strategically orient or reorient with a turnaround strategy of retrenchment or recovery, and 2. Not exaggerate the current, short-term developments, because of unproductive uncertainty:

-

•

To prepare for future environmental shocks, aviation managers should embrace the following: 1. Develop a common strategy language, introduce uncertainty as a standard factor for long-term planning, manage uncertainty proactively and make long-term plans accordingly. 2. Foster a continuous dialogue with formal & informal strategy meetings on various levels of the organization and with various stake- and shareholders. 3. Be aware of the strategy tools being used, they might be vital for the success of long-term planning and other organizational outcomes. 4. Make the board a co-creating team. If the board does not have the necessary capabilities and experience, compose it differently and diversely. 5. Introduce a three-step process to embrace uncertainty in the organization by sensing changes, seizing opportunities, and transforming the organization accordingly.

1. Introduction

In 2020, the aviation industry is looking different than months and years before. The disease COVID-19 is spreading across the globe, causing significant change to society and aviation organizations. The aviation industry has a history with natural and economic shocks that impacted the industry heavily in the last two decades: among others, SARS, 9/11, Eyjafjallajökull or the Indonesian volcano ash clouds as natural shocks and the financial crisis of 2008 as an economic shock. Also, companies of the aviation industry are being struck by industry-internal transformations that influence the rules and functioning of the industry, among others, deregulation in the airline market in the US and Europe, privatization of important network actors, competition from low-cost carriers for established full-service network carriers. Nevertheless, COVID-19 disrupted the airline industry in spring 2020 at an unprecedented level and the pandemic will impact the industry in the years to come. Airlines are going bankrupt internationally, governments help airlines and many other aviation organizations with credits, loans or other financial measures to ensure liquidity shortages. Others try to secure their future without any governmental support, blaming other airlines of misconduct by approaching governments or investors to offer financial shields. One can observe that nearly every aviation organization worldwide is challenged to secure the long-term survival of their organization. The main research question of this paper is, therefore, how to make plans for environmental shocks such as COVID-19 to reduce the exposure to the risks that such shocks pose as well as to strategically innovate, adapt and emerge successfully from shocks?

Each of the shocks, as mentioned above, had specific characteristics, yet all have something in common: an increase in the level of uncertainty posed by the external environment of organizations. A continuous transformation within the industry, combined with these environmental shocks, created a vacuum for strategic planning for many organizations, thus lifting them into a stadium of unproductive uncertainty and paralysis for long-term thinking and acting (Furr, 2020; Star, 2007). Therefore, it is crucial to learn how to prepare for and strategically innovate, adapt and emerge successfully from shocks such as COVID-19 (Gudmundsson and Merkert, 2020). This article aims at comprehensively summarizing main strategic management theories and frameworks on how to shape organizations strategically in times of environmental change, rising levels of uncertainty and environmental shocks. These frameworks and theories ought to be used to embrace uncertainty as a standard factor for aviation organizations (since it will be anyways) and introducing robust strategic structures and processes to handle shocks proactively, by creating a culture of resilience and openness to transformation. This theoretical summary helps aviation decision-makers to create organizations’ preparedness for shocks as well as offers opportunities for recovery strategies following significant shocks such as COVID-19. This paper highlights possible avenues on how aviation managers can make plans for such shocks, thus reducing the exposure to the risks that such shocks pose as well as strategically innovate, adapt and emerge successfully from shocks, such as COVID-19.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. COVID-19 is no black swan but increases the level of uncertainty for aviation managers

Every year, the World Economic Forum (WEF) asks managers before the annual meeting in Davos, what they consider to be the most significant risks for the business world (WEF, 2020). For this year, environmental issues such as climate change, cyber-attacks and data breaches were named as the most probable global risks (p. 3). A few months later, the world looks different: The disease COVID-19 has been spreading across the globe, causing significant change to society but also to aviation organizations internationally. Obviously, the aviation world was surprised by COVID-19 and its massive impact. The pandemic is impacting not only central network actors, such as airlines, airports, or service providers, but literally everyone involved in the so-called “aviation system” (to find a comprehensive definition of the «system of aviation» and the key actors being involved, see Wittmer et al., 2011). How could something like this happen?

Lipsitch et al. (2009) found that emerging influence pandemics are a “combination of urgency, uncertainty, and the costs of interventions [which] makes the effort to control infectious diseases especially difficult.” No doubt, globally spread infectious diseases are relatively rare events. The high damage potential is usually assigned a very low probability, which also means that pandemics are assigned a subordinate role compared to other risks. This is why some organizations might not have dedicated action and strategic plans for globally spread infectious diseases. Organizations were simply not able to quantify the impact of such an event. Managers of aviation organizations now ask themselves: how should I predict, calculate, or even make plans for such events? Not being able to answer these questions, the outbreak of COVID-19 is often described as ‘black swan’1 in recent articles (Deloitte, 2020; Winston, 2020). To be called a black-swan, the event must first of all be a surprise to the observer. Second, it has to have a significant effect. Third, after the first recorded instance of the event, it must be rationalized in hindsight, as if it could have been expected. However, COVID-19 did not arise in a vacuum. Pandemic plans have already been made by many countries, politicians, and organizations. Even the WEF managers rated ‘infectious diseases’ as their number 10 risk for the next ten years (WEF, 2020). So, COVID-19 should not have been a surprise at all. Similarly, Nassim Nicholas Taleb and Mark Spitznagel (2020) highlight in their article in March 2020 that COVID-19 is definitely no black swan, but should rather be described as an event which is inevitable, because of the structure of the modern, globalized world.

Though, calling COVID-19 a black-swan or not does not help any manager per se to make better plans for such events or cope with COVID-19. It seems evident that COVID-19 is an event in the external environment of an organization that creates high levels of uncertainty.2 The answer to the problems may be found in the management of uncertainty and the external environment and a shock is therefore basically two-fold from an action-perspective: operative reaction to the short-term development and long-term reaction with strategic planning to use the crisis as an opportunity. Central questions that this paper ought to answer are: how can someone prepare and make plans for such shocks? How do I manage uncertainty proactively? How can I strategically plan for uncertain times? How do I create a more resilient and future-oriented organization using the shock as opportunity?

2.2. Strategy-as-practice as an answer on how to deal with high levels of uncertainty

Many different theories and frameworks of strategic management have guided the discussions on how organizations may be strategically organized and structured in a more resilient way, to embrace high levels of uncertainty and prepare organizations for environmental shocks. The theories have only recently been led by researching the actual doings of strategy actors. This new research stream of “strategy as practice” (SAP) is combining existing theories of strategic management dealing with the aspect of uncertainty, such as “neo-institutional theory (NIT)” (DiMaggio, 1998; Scott, 2013), “structural contingency theory” (Donaldson, 2006, 2013; Ellis and Shpielberg, 2003), the theory of “scenarios” and “strategic foresight” (Allaire and Firsirotu, 1989; Chaharbaghi et al., 2005; Krys, 2013; Schoemaker and Van der Heijden, 1992; Vecchiato, 2012), the theory of the “resource based-view” (Aragón-Correa and Sharma, 2003) and its related theory of “dynamic capabilities” (Helfat and Peteraf, 2015; Teece et al., 1997, 2016), with sociological theories (Jarzabkowski, 2004; Jarzabkowski and Paul Spee, 2009; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011; Suddaby et al., 2013; Vaara and Whittington, 2012; Whittington, 2006, 2007), to tackle the real actions and problems of strategic managers (Jarzabkowski, 2005; Johnson, 2016). This theoretical push in strategy research ought to make the theories practically more useful. Among others, this recent theoretical development aims to find how strategic managers can embrace higher levels of uncertainty of their environment and make strategic plans accordingly by aligning their internal structures, processes and resources to the environmental change (Kaplan, 2008; Vaara and Whittington, 2012; Whittington, 2010) – vital characteristics in times of environmental shocks. The following paragraphs shall give an overview of this recent theoretical development to give guidance to aviation managers in times of shocks and environmental change. It may not be possible to predict COVID-19 in the form of occurrence, nor can the impact be quantified. However, what these theories of strategic management highlight is that the proactive management of uncertainty and a strong long-term perspective during and after such shocks might help react to changes in the external environment faster and more efficient and create more resilient organizations, possibly helping to manage even black-swans in the future.

3. Theories of long-term planning in times of environmental uncertainty

3.1. Long-term planning during environmental shocks

Scholars of strategic management have found that during shocks, such as COVID-19, managers should not get paralyzed by unproductive uncertainty and strategically orient or reorient with a retrenchment, recovery and thus, a turnaround strategy. This will enable aviation managers to think strategic, even when facing short-term challenges.

3.1.1. Strategically orient or reorient with a retrenchment, recovery or turnaround strategy

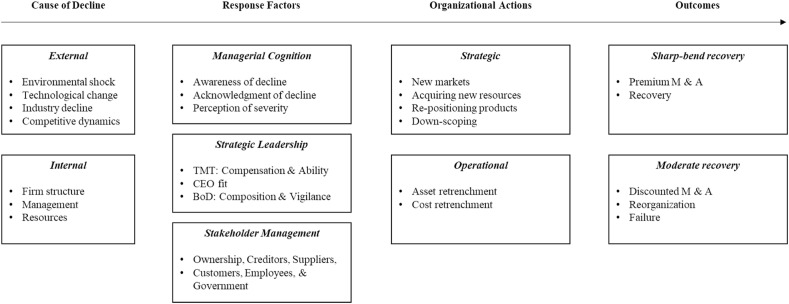

First of all, aviation managers need to be aware of the cause of the decline, the organization is facing. Sudden and discontinuous change in an environment, such as COVID-19, may reduce the efficiency and effectiveness of strategies, with a possible result being organizational decline. Thus, managers need to adapt to these environmental jolts properly (Meyer, 1982; Wan and Yiu, 2009). Understanding what the cause of decline is, will help to structure a process to cope with it and help alter the actions taken to react to it proactively. Subsequently, it is essential to consciously stress managerial cognition by acknowledging and making aware that an environmental shock is happening, trying to assessing its magnitude and severity. Further, it will be important to assess the TMT's strategic fit to the situation as by evaluating the TMT's (especially the CEO's and BoD's) capabilities and composition to cope with the situation at hand. They are the vital units to manage the turnaround. Lastly, stakeholders might be vital for the success of the turnaround, thus, engaging with them might enable an organization to have an outside view of the situation and create a buy-in for the turnaround strategy.

In the next step, organizational actions will define the success of the turnaround. Aviation managers need to be aware of the nature of the retrenchment–recovery interrelation. Scholars found that this relation might influence turnaround performance (Schmitt and Raisch, 2013; Trahms et al., 2013). They stress that retrenchment and recovery are both, contradictory and complementary (Schmitt and Raisch, 2013). Integrating retrenchment and recovery actions allows organizations to generate benefits that exceed the costs of their integration, which might positively affect turnaround performance overall (Nixon et al., 2004; Robbins and Pearce, 1992). For example, Lawton et al. (2011) developed a framework for successful reorientation in the legacy airline industry to focus on and leverage profit maximization, quality, leadership, alliance networks, regional consolidation and staff development. For aviation managers, it is vital to introduce a mix of cutbacks and strategic investments, strategic actors have to exercise cost discipline and financial prudence and, at the same time, sense opportunities that offer reliable returns in environmental shock periods (Gulati, 2010). For example, it might be advisable to discuss the causes of decline, before, e.g., firing people or introducing new H.R. strategies or practices (Arogyaswamy et al., 1995; Santana et al., 2017, 2019). The retrenchment–recovery interrelation, thus, highlights the challenge of developing strategic and operational actions at the same time, which is highlighted in Fig. 1 (BARKER III and Duhaime, 1997; Morrow et al., 2007; Wan and Yiu, 2009).

Fig. 1.

Framework of orientation and reorientation and strategic turnaround.

Fig. 1 summarizes the prior described main findings from recent literature on strategical orientation or reorientation for turnaround strategies. The model is split into four sections, the cause of decline, the response factors of organizations to it, organizational actions and the outcomes of these turnaround strategies. This framework acts as a guiding framework for the chapters that follow.

3.1.2. Do not get paralyzed by uncertainty but manage it proactively and develop uncertainty capabilities

Further, besides introducing a turnaround strategy, it is crucial for aviation managers not to get paralyzed by uncertainty, which might result in unproductive uncertainty.3 Aviation decision-makers must embrace uncertainty as a critical aspect not only for their short-term actions but also for their long-term planning process – thus developing uncertainty capabilities or dynamic capabilities with a particular focus on managing uncertain environments (Li and Liu, 2014; Teece and Leih, 2016). This means being aware and acknowledge the environmental shock and increase in uncertainty and perceive its severity and magnitude. These capabilities enable managers to open their eyes to options and alternatives of the present and the future. Human nature leads managers to make strategic decisions based on their lived experience (Berglund, 2007; Samra-Fredericks, 2003) as well as on the history of one's own prior decisions (Busenitz and Barney, 1997; Hodgkinson et al., 2002), and routines (Betsch and Haberstroh, 2014) rather than with an eye on the bigger picture and environmental change (Becker and Knudsen, 2005; Betsch et al., 1999; Johnson et al., 2010b). In times of black-swans, shocks or incremental, environmental change, it is tempting to firefight, but it is crucial to consider the future and thus long-term assumptions as well. Nathan Furr (2020) found that during times of unproductive uncertainty, managers often get trapped in imagining extreme performances. On the contrary, managers who are skilled in managing uncertainty think in terms of probabilities and alternatives instead. These managers also perceive the crisis as being a huge opportunity for the long-term development and sustainable success.

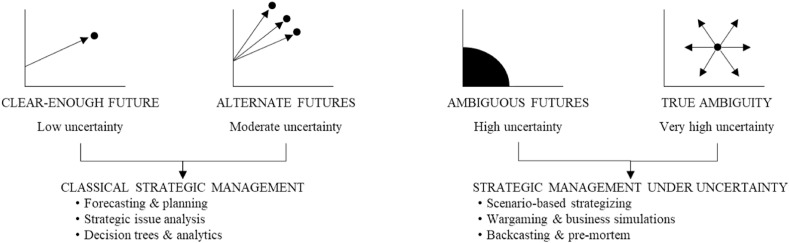

Through embracing uncertainty as being a vital factor for long-term planning, aviation managers will understand that strategy under uncertainty is different from classical strategic management (see Fig. 2 ; adapted from prior studies of Star, 2007; Amram, 1999; Thorén and Vendel, 2019). Whereas classical strategic management is vital in times of clear-enough or alternate futures, strategic management under uncertainty means that managers need to deal with higher ambiguous futures and even actual ambiguity. For actual ambiguity, what this means explicitly, is that there is no predictable range of outcomes. Managers should deal with this by using scenario-based approaches, wargaming & business simulations as well as backcasting or pre-mortem. The latter strategy tools might especially be useful for aviation actors, since the aviation industry has a history with environmental shocks, thus offering many exemplary cases that might be useful for future assumptions and planning under high levels of uncertainty.

Fig. 2.

Classical strategic management and strategic management under uncertainty.

Thus, acknowledging and embracing these high levels of uncertainty during times of shocks for the short-, but also in the long-run, will prevent managers of unproductive uncertainty and support managers in making better decisions about the future of their organization.

3.2. Long-term planning to prepare for future environmental shocks

Besides the short-term, more operational oriented strategic actions during times of environmental shocks highlighted in chapter 3.1, long-term planning are vital to adapt, innovate, and emerge successfully from such environmental shocks, such as COVID-19, to develop a more resilient organization for future environmental shocks. To do this properly, scholars of strategic management found several aspects being vital: fostering a common strategic language among strategic actors, introducing uncertainty as a standard factor for long-term planning (since it will be anyways), enable an internal and external dialogue on environmental change, and make the TMT a co-creator to use its capabilities and experience best. Further, and as soon as possible, introduce a three-step process to embrace uncertainty in the organization by sensing changes, seizing opportunities, and transforming the organization accordingly to make the organization more resilient of environmental change in the long-run, as well as clearly define roles and involvement of actors during crisis management in this three-step process.

3.2.1. Foster a common strategic language

To foster strategy under high levels of uncertainty, aviation managers first need to speak the same language. The author of this paper does not mean the literal language that an organization speaks, which might be vital to address as well (Neeley and Kaplan, 2014), but instead taking the actual social practice of strategizing seriously (Vaara and Whittington, 2012). Strategic language is difficult and can lead to misunderstanding, even impacting the strategic and financial performance of organizations (Seidl, 2006). Seidl (2006, p. 1) found that “every single strategy discourse can merely construct its own discourse-specific concepts.” This might lead to productive misunderstandings in strategy-making (Mantere, 2010; Seidl, 2006). On the contrary, good strategy discourse might lead to better sensemaking in top management teams (Balogun et al., 2014) and strategic sensemaking and sense-giving by middle-managers (Rouleau, 2005). Managers should not underestimate the importance of negotiations and written text documents of strategy (Fenton and Langley, 2011). Narratives of strategizing ought to be seen “as a way of giving meaning to the practice that emerges from sensemaking activities, of constituting an overall sense of direction or purpose, of refocusing organizational identity, and of enabling and constraining the ongoing activities of actors” (Fenton and Langley, 2011). Thus, texts and strategy documents play a vital role in strategizing (Hendry, 2000; Kornberger and Clegg, 2011). Pälli et al. (2009) show in a case study of Lahti city planners that “specific communicative purposes and lexico-grammatical features characterize the genre of strategy and how the actual negotiations over strategy text involve particular kinds of intersubjectivity and intertextuality” (p. 2). For aviation managers, this means that they need to introduce key terms and definitions for their strategizing and approve these terms with their strategic actors within and outside of the organization regularly. An aviation manager talking about the “vision” or “strategy” of the respective organization might mean something vitally different than another manager, if the strategic language has not been defined previously. This common language might especially be important in highly technological contexts, such the aviation industry. These expert organizations and their managers might have difficulties translating highly technical or engineering terms into strategic and thus long-term language. E.g., aircraft manufacturers and their supply chain managers as well as their tiers in the supply chain might speak of the same tool or technical term, but from a totally different angle. In this context, speaking the same strategic language in such complex and uncertain environments means more efficiency and more effective supply chain management – vital in times of shocks and important to secure supply chain operations in times of historic circumstances that the aviation industry is recently facing.

3.2.2. Introduce uncertainty as a standard factor for long-term planning

Although embracing the uncertainty of the external environment being a vital factor for long-term planning, uncertainty does not only arise via external environments. Strategizing itself is concerned with the future of an organization, and this future is per se uncertain. Every decision itself creates new uncertainties. Thus, uncertainty also develops internally through decision-makers making decisions on future directions and plans of organizations. The challenge in this situation is not to crave for more information to make ambiguous less, but instead feeling comfortable with uncertainty. As Johnson (2015) put it in an HBR article, “get comfortable with the unknown”. Baran and Scott (2010) have studied how people in high-risk professions, such as firefighting, deal with uncertainty. What they found is the so-called theory of organizing ambiguity. Firefighters conceptualize their circumstances by “mak[ing] effective sense of the hazards within dangerous contexts such that they avoid catastrophic mistakes” (p. 43). Firefighters take action knowing that the environment might change and alterations from original plans may be needed. Strategic aviation managers need to cope with uncertainty such as firefighters do. They need to make it their daily routine and habit to work with uncertainty – not solely for the sake of reacting to the environment, such as in the case of COVID-19, but also for their decision-making praxis and practices. Aviation managers should, therefore, introduce uncertainty as a standard factor, since it will always be part of long-term planning anyways.

3.2.3. Enable an internal and external dialogue on environmental change

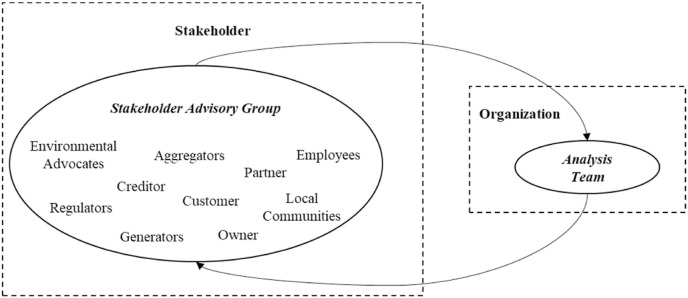

What might help to embrace uncertainty as a standard factor is to enable an internal and external dialogue on environmental changes to challenge assumptions regularly (Hellström, 1996). A critical and open discussion on internal and external environmental changes should be fostered between the primary stake- and shareholders of the organization (Cornell et al., 2013). This dialogue also fosters cognitive and reflexive functions, which are vital for strategy-making (de Boer et al., 2010) and turnarounds in times of environmental shocks (Arogyaswamy et al., 1995). This means introducing more formal as well as informal strategy interactions for exchanging ideas and thoughts on recent changes in the environment and developing strategic initiatives or programs. These strategy interactions should be based on openness in terms of weak signals, strategy and business models (Chesbrough and Appleyard, 2007; Hautz et al., 2017). Important here is to raise the level of imagination and curiosity for change internally, but also externally. This impulse to seek new information and experiences as well as to explore novel alternatives might lead to new assumptions, fewer black-boxes and finally, lead to better firm performance (Gino, 2018). Triggering and fostering curiosity and imagination might lead to more broad, deep and rational decisions as well as more creative solutions (Harvey et al., 2007). One might assign dedicated teams to scan the environment in so-called analysis teams. This is also helpful to institutionalize and routinize the interactions and have dedicated people and clear roles and responsibilities for this topic. Further, organizations might engage with an extensive range of stakeholders in brainstorming or platform sessions (Buysse and Verbeke, 2003; Freeman and McVea, 2005). In the best case, aviation managers should foster such a dialogue on different levels as well as with the main stakeholders of the organization4 (see Fig. 3 below).

Fig. 3.

Platform for internal and external dialogue on environmental change.

Integrating these platforms for dialogue into a centralized, in the best case already established, “Governance, Risk and Compliance Management” tool might be helpful to institutionalize the findings and build organizational routines, while complying with regulation, addressing the risks appropriately, and assigning tasks and responsibilities efficiently (Becker and Zirpoli, 2008; Tarantino, 2012). An excellent example of such internal and external dialogue is the ANSP of Switzerland, skyguide. Together with the main stake- and shareholders, customers, partners, regulators, and general environmental advocates, they introduced a platform called SUSI (Swiss U-Space Implementation), which is hosted by the Federal Office for Civil Aviation (FOCA) in Switzerland. This dialogue-platform offers skyguide strategic reflexivity and dialogue on unmanned air traffic as well as an outside view into recent and future developments of this field, which might be vital for their long-term success in the ANSP market. The platform is even integrated into a more extensive, international network called GUTMA (Global UTM Association), which fosters this reflective dialogue on a larger scale. Skyguide links these platforms to a dedicated analysis team internally, to align their own assumptions and to seize the opportunities that might arise for them. This is not exclusive to skyguide and the Swiss context, but observable in many different national contexts and throughout the whole aviation system. For example, Carton (2017) found in studies on NASA-teams in a paper published in 2017 that this sense of purpose might boost employees’ coordination and collective enthusiasm, thus not only offering alignment to environmental change but also fostering internal processes and employee satisfaction through involvement and sensemaking. Fostering this engagement on curiosity and imagination on different levels might also allow leaders to gain more respect from their followers and inspire employees to develop more-trusting and more-collaborative relationships with colleagues (Gino, 2018)

3.2.4. Be aware of the strategy tools being used

Such platforms may establish fast and interactive iterations of thinking and acting in the best case resulting in commitment, motivation, and strategic change in- and outside of the organization more rapidly. This encouragement might help people to imagine the future, which counters the passivity and feeling of helplessness in times of shocks (Bode et al., 2011). However, and besides the great opportunities such platforms pose, aviation managers should be aware of the tools being used during strategizing. Tools are boundary objects for strategy-making and will, most probably, affect the success of the long-term planning process as well as firm performance (Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009). Tools, such as scenarios or wargaming, might help to reduce uncertainty and align the organization to environmental change, but only if addressed correctly and for the right purpose (Alberts, 1996; Godet, 2000; Schwarz, 2009). Jarzabkowski and Kaplan (2015) highlight that “strategy is not something an organization has but rather something that people in organizations do (Whittington, 2006). Tools are most usefully seen as parts of the process rather than purely as sources of the answer.”

Thus, aviation managers need to be aware of the pitfalls and risks facing new management tools by, e.g., leading virtual teams (Ale Ebrahim et al., 2009; Ford et al., 2017). Using virtual meetings correctly and strategically and breaking up big virtual meetings by embracing silence in brainstorming sessions and using breakout rooms to create a sense of accountability (Kreamer and Rogelberg, 2020) might increase effectiveness and efficiency. Raffoni (2020) highlights in her HBR article that leaders should ask themselves five main questions when leading virtually:

-

1.

Am I being strategic enough?

-

2.

Have I revamped communication plans for my direct team and the organization at large?

-

3.

How might I reset roles and responsibilities to help people to succeed?

-

4.

Am I keeping my eye on (and communicating about) the big picture?

-

5.

What more can I do to strengthen our company culture?

Managers should keep these five questions in mind, especially when leading virtually, but also for the long-run to use these new tools appropriately and effectively.

3.2.5. Make the TMT and especially the board a co-creator in times of uncertainty

In times of transformation and environmental shocks, aviation managers need to continuously assess their Top Management Team (TMT) and reflect their abilities and competences. The strategic leadership of the organization may be a vital obstacle or facilitator of the strategic turnaround. Especially the CEO and his or her fit to the situation might be critical for the success of the turnaround. For example, Chen and Hambrick (2012) found that longer-tenured CEOs may be less effective in turnaround contexts. Aviation managers, thus, need to ask themselves if the leadership is fit enough to cope with the situation? Does the organization need other capabilities to manage the situation? Does the TMT need an outside view to reflect on current biases and black-boxes? Would outsiders in the TMT be beneficial? Is the TMT compensated enough and efficiently for taking the risk of their reputation and future employment? By answering these questions, organizations enable a fit between the situation and the TMT as well as motivate their leadership to take risks and manage the turnaround strategically.

Also, many organizations have problems and struggle with who is responsible for strategy-making in times of uncertain environments and communication between levels (Arogyaswamy et al., 1995). Scholars found that the conversation between management and the board is especially relevant here since these are the most crucial teams for strategizing (Paroutis and Heracleous, 2013). One should reduce the natural information asymmetry between these two most vital strategic teams. Scholars found that strategy meetings and workshops are vital for this relationship, among other effects, constructing shared views around strategic issues, creating consensus, and introducing strategic change (Johnson et al., 2010a; Kwon et al., 2014; Liu and Maitlis, 2014; Wodak et al., 2011). Scholars found that the board might be the key strategizing actor, especially in times of environmental uncertainty, with Leblanc and Gillies (2005) even argue that “nothing is more important to the wellbeing of [an organization] than its board”. For example, in Switzerland, the board is the key strategizing actor even by law.5 Among other duties, the board is responsible for the development of strategic objectives, the determination of the means necessary to achieve the goals, issuing the required instructions to the executing bodies, and controlling the implementing bodies about the achievement of objectives (Müller et al., 2014). To do this, the board needs to be in a cooperative strategic dialogue with management and steer through strategic guidelines (Carpenter et al., 2004).

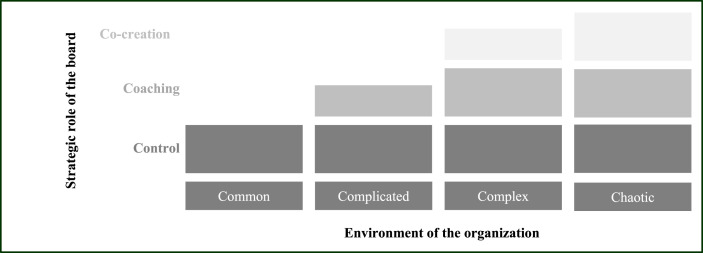

Despite strategy being a non-delegable duty, the strategic role of the board is not self-determined in organizations today. Hence, and especially in times of environmental uncertainty, it is essential to define the role, function, responsibilities, and involvement of the board in strategizing. Scholars highlight that the board needs to take a more substantial strategic role (Cossin and Metayer, 2014; Hendry et al., 2010) and get involved more often (Carpenter and Westphal, 2001; Pearce and Zahra, 1992; Ruigrok et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2016) especially in dynamic industries and in times of high levels of uncertainty (Garg and Eisenhardt, 2017; Judge and Talaulicar, 2017; Oehmichen et al., 2017). This might diverge from solely supervision, to coaching or even a co-creating role,6 depending on the context of the organization (see Fig. 4 below). In times of highly uncertain environments, such as in times of COVID-19, it might be advisable for boards to be co-creators, not only to take a controlling-, supervising- or coaching-role (see Fig. 4).7 Thus, in this so-to-say chaotic environment of COVID-19, the board needs to spend an equal amount of time on co-creating as on supervision (Gardner and Peterson, 2020). This would mean making most of the capabilities and, in the best case, the experience of its members (Ingley and Van der Walt, 2001; Kim et al., 2009). If the board does not lead strategically or does not have the necessary capabilities and experiences for such shocks, compose the team differently, since this is key for the success of the organizations (Åberg and Shen, 2019; Van der Walt et al., 2006).

Fig. 4.

The strategic role of the board depends on the environment of the organization.

When discussing strategic involvement and actions, a particular focus needs to be placed on the interactions of the chairman and the CEO, who are the most influential and important actors for the long-term success of organizations (Ma et al., 2019; Nadler, 2004). Like the dialogue with stakeholders, this includes introducing more formal as well as informal strategy interactions for exchanging ideas and thoughts on recent changes in the environment and developing strategic initiatives or programs. One strategy workshop with the board per year might not be enough anymore to develop sustainable strategies. Aviation managers need to step-up their strategic game in their top management team and use platforms for regularly strategizing to enable the prior-described three-step process to be successful. Only then, they will be able to develop literal dynamic capabilities and adapt, innovate, and emerge from environmental shocks, such as COVID-19.

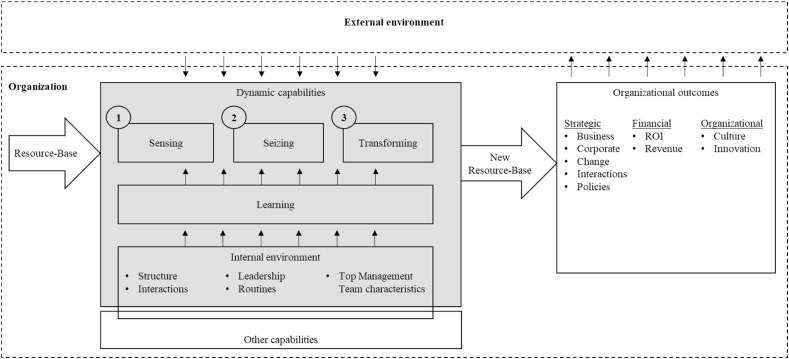

3.2.6. Introduce a three-step process to embrace uncertainty within the organization

Besides the possible paralysis through high levels of uncertainty, environmental shocks also influence the strategic processes of organizations in a major way. Strategic management scholars have found that under high levels of uncertainty and in times of shocks, long-term plans need to be adapted accordingly and more regularly (Hambrick, 1982; Hambrick et al., 2008; Kukalis, 1991). Thus, in times of, e.g., pandemics, climate change or digitalization, agile and more flexible long-term, strategic plans are vital for the success of an organization (Eisenhardt et al., 2010). Such dynamic plans might create a temporary but also a sustainable competitive advantage (Dibrell et al., 2014). To embrace uncertainty, it is essential to demonstrate a determination to sense what is happening in the environment, seize the opportunities arising from the environmental change, and transform the organization accordingly (Hodgkinson and Healey, 2011). The terms sense, seize and transform are vital terms for long-term planning of organizations and refer to the “theory of dynamic capabilities”, first introduced by Teece et al. (1997). The goal of dynamic capabilities is to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments as an organization. Therefore, aviation managers need to create a “learning organization” (Romme et al., 2010; Teece, 2012), partly and continuously breaking with established routines and structures (Turner et al., 2017), to adapt to the new environment (Makkonen et al., 2014) and develop a more resilient organization (Mamouni Limnios et al., 2014). Following this established three-step process of sensing, seizing and transforming, aviation managers might be able to manage the associated uncertainties of the environment more proactively, often and much more regular and agile. The following paragraphs will highlight what this three-step process specifically means for aviation managers in times of environmental shocks such as Covid-19 and what they need to be aware of:

3.2.6.1. Sensing

First of all, in a situation of uncertainty, it is vital to grasp and describe the problem. It is essential to learn quickly and build or rebuild strategic resources, which requires routines of interaction in coordinated search and learning procedures (Pavlou and El Sawy, 2011; Schilke, 2014). What was certain before might be uncertain in the new situation. Therefore, one should 1: Define the most critical key performance indicators8 for the uncertain situation – both for the short- and long-run. What are the most critical factors – of the event and for the organization? In the case of COVID-19, does the disease impact these performance indicators? 2: It is crucial to distinguish between the short- and long-term impact, for example, on the business model, the supply chain, or the workforce, respectively, the resource base of the organization. 3: It is beneficial to work with scenarios, wargames or general business simulations to embrace uncertainty. 4: It is necessary to work with radical alternatives and options to develop an extensive range of possible futures, e.g., for the impact on liquidity, other financial measures, and operational metrics. 5: Managers should try to design dashboards to filter the most relevant and urgent information and be up-to-date in real-time. The better uncertainty is understood, the more likely it is that efficient and effective trade-offs can be made between different outcomes for the organization and decisions to be taken more objectively. Therefore, managers should think in terms of options, not binary outcomes (Helfat and Peteraf, 2015). For example, governments might change their rules for production facilities fast, regulators might introduce new rules of compliance, airlines might change their fleet strategy, and aircraft manufacturers might change their supply chain management according to the new environment. Being open, curious about this change and being able to imagine such change will benefit the individual manager, but also the organization as a whole. Thus, aviation managers should be aware that nothing is completely within their control and assumptions are not conclusive. Change might happen fast and the true capability of sensing is to continuously challenge the prior established assumptions – literally as a learning organization.

3.2.6.2. Seizing

Once essential parameters have been identified in a broader context, the next step is to analyze causal relationships for their organization (Teece et al., 1997). What does environmental change for my own business and how can I leverage it? For example, aviation managers must be able to link, e.g., behavioral changes of customers, suppliers or partners, as well as new regulations (in this case in times of COVID-19) with their existing business model and structures of the organization. Aviation managers need to understand that this seizing activity is vital to create an ambidextrous organization, which means that the organization can be efficient in its management of today's business, but also adapted for coping with tomorrow's change as well (O'Reilly 3rd and Tushman, 2004; Taylor and Helfat, 2009). Despite common assumptions, these two aspects are not contradictory but complementary. Aviation managers, therefore, need to be able to engineer design choices for both to develop opportunities for their own business. While engineering design choices, aviation managers should also identify potential markets and the timing for these seizing alternatives (Day and Schoemaker, 2016). To enable this, managers might break down the significant environmental change into smaller, more manageable steps for which a solution may already exist or which are easier to calculate (Wilden et al., 2013). These smaller shares then need to be adjusted to the internal context and the structure of the organization (Kindström et al., 2013). These discrete and manageable sets of options should be made clear and definite to build trust and commitment – internally and externally with the main stakeholders (Fainshmidt and Frazier, 2017; Vanpoucke et al., 2014). Seizing, in this case, means, for example, for network carriers to rethink their loyalty programs because of behavioral change patterns of customers. For LCCs, seizing opportunities of COVID-19 could mean to alter revenue sources and out-of-the-box forward integration because of new work possibilities and more home-office. Understanding causal relations of the environmental change and internal structures and resources is vital in this second phase of seizing.

3.2.6.3. Transforming

Thirdly, environmental change requires the ability of an organization to transform its asset structure and accomplish the necessary internal and external transformation (Teece et al., 1997). Aviation managers should develop an action plan for adjusting their internal and external strategic assets. The long-term competitive advantage might be fostered through the integration of external activities and technologies by selecting the boundaries of the organization and therefore looking for possible alliances, networks, or partnerships (Blome et al., 2013). In the case of COVID-19, this means that new strategic assumptions might foster a change in the structure, processes, designs, and incentives of the organization – maybe even long overdue anyhow. It is helpful to think of decentralization, local autonomy, and strategic alliances or networks to transform the organization (Birkinshaw et al., 2016). It is essential to ask what the organization is aiming for as turnaround outcome – premium or discounted M&A, recovery, reorganization or even failure. Therefore, managers should also think of possible exit strategies of non-productive, inefficient programs or technologies. For example, as Air Navigation Service Provider (ANSP), it might be interesting to partner with new technology providers in the area of U-space, create spinoffs for digital airspace solutions, introduce long overdue digital strategies to transform the organization or even exit in certain areas where decline is inevitable anyways. COVID-19 might be a trigger for such transformations. Skyguide, again, is an excellent example of such a transformation process. They push a strategy towards a virtual center and foster a strategy for unmanned air traffic, called u-space, with a national and international partner network, thus using COVID-19 as an enabler for a transformation that is long overdue, and despite, and maybe even because of, a very low number of flights operating in times of COVID-19. Thus, despite the workforce being involved in temporary labor reductions plans, they foster strategic change and introduce long-term actions. In this transformation phase, aviation managers need to be aware of their communication of such a transformation (Helfat and Peteraf, 2015). Roles and responsibilities should be clearly defined, and transformation needs to be clearly communicated and made transparent to accomplish an effective and efficient alignment (Dixon et al., 2014; Hodgkinson and Healey, 2011). If not done correctly, for example in the case of skyguide, this transformation in times of COVID-19 might backlash, offering opportunities for unions, governments or other stakeholders that might see the transformation critical, to restrict the transformation of happening at all, causing long-term damage to the success of the organization. Thus, short term actions based on such long-term assumptions might be vital, but also risky when not done properly.

Fig. 5 offers a summary of the above-mentioned three-step process, illustrating how these dynamic capabilities of sensing, seizing and transforming are strongly interlinked with the external and internal environment of the organization. Further, what is illustrated in Fig. 5 is that these dynamic capabilities impact the strategic, organizational and financial outcome of the organization, highlighting that these capabilities are vital for the long-term success of organizations challenged by environmental change.

Fig. 5.

Dynamic capabilities in and their relationships to the external and internal environment as well as their organization outcomes.

3.3. An integrative model to foster resilience and tackle environmental shocks

Fig. 6 summarizes the prior described aspects for long-term thinking during environmental shocks and increasing the readiness for future ones. It offers a solution to foster long-term planning during times of environmental shocks and, further, highlights possibilities on how to prepare for future shocks and make the organization more resilient to them. This framework is to be seen as a framework for aviation managers and may be used as a rough guideline for long-term planning for the months and years to come.

Fig. 6.

A framework to foster long-term planning during environmental shocks and to prepare for future ones.

4. Discussion

The theories and frameworks highlighted in chapter 3 offer guidance to aviation managers in times of high levels of uncertainty, during times of environmental shocks, as well as offer solutions on how to prepare for shocks in the future. Despite these approaches being vital for aligning the organization to the environment and sustainable organizational success, one should always reflect if strategic transformation is needed and possible in the long-run. Besides not getting paralyzed, it is also essential to be prudent and patient in times of environmental change, too. One should not overreact to environmental change too soon and align strategic assets, processes or even whole strategies based on short-term assumptions, changes and developments. Further, short-term actions might counteract established and successful long-term plans. Aviation managers should not be actionists in times of environmental change. While highly technological companies might do transformations more naturally and more commonly, for aviation organizations this transformation process towards embracing uncertainty might be more difficult. An excellent example of long-term thinking in times of COVID-19 are the recent decisions of airline managers to retire main parts of their “old” and inefficient fleet to make room for new, more efficient and more sustainable aircraft after COVID-19. Even if this seems counterintuitive and irresponsible at first from a financial perspective, these decisions might be vital for airlines, in the long run, to be successful after the environmental shock of COVID-19.

Also, in times of pandemics such as COVID-19, new work developments seem to influence the actual strategy practices and praxis described in chapter 3. During COVID-19 or other environmental shocks, it might be that people are not able to meet at times. This pressure and a general trend towards New Work will open up opportunities by, e.g., introducing more flexible working hours and jobs, shared desk solutions, or using digital solutions to liaise closely and foster creativity and collaboration even when not meeting physically. Full virtual workforces might be established on a level we've never seen before. One the other hand, leading virtually offers significant challenges and different ways of interacting as well as sharing information. The pitfalls and major questions to answer described in chapter 3 might help aviation managers to cope with this high amount of further complexity in managing their teams virtually. New Work and the respective strategic tools to foster this development focus on the progress of each individual person. In times of environmental shocks and more generally in the future, it will be about the successful symbiosis of living and working to conduct strategy practices and praxis effectively.

The structure, strategy processes and interactions, as well as new dynamic capabilities aviation managers, are building right now will continue to serve them after COVID-19 and potentially for next shocks that are hitting the industry in the future. Every shock, and every effective response to it, creates a “new normal” complete with new routines, new assumptions, and possibly new technologies (Kanter, 2020). Also, it creates cognitive patterns and experiences with such situations, which might, in times of future environmental shocks, benefit aviation managers that have experienced such a situation before. And thanks to the strategic theories and frameworks mentioned in chapter 3 of this paper, aviation managers might be sharply focused and sensitized for future environmental shocks, with new dynamic capabilities, processes and activities that might lead to their organization being more resilient, effectively and, generally, more long-term-looking and long-term-thinking than before - whether from home or the office.

Further, in the aviation system, a shock such as COVID-19 exposes institutional gaps, divides, and many unsolved problems. This might be a massive opportunity through an intense quest for new standards in the aviation industry. What one can see already is that customers might change their behavior and needs, partners might want to rethink their agreements and manufacturers might change their requirements for suppliers. Also, in the broader system of the aviation industry, legislators might want to add or tighten regulations, new technologies might emerge faster, and sustainable solutions might be more critical than ever before – not only to customers but also to institutional actors. Government officials might want to fix long-standing systemic problems by taking a new tack. Strategizing of aviation managers needs to align with this so-called “new normal” of the industry. The frameworks and theories of this paper might help aviation managers to do so and think in the long-run, even if this might be counter to what managers are used to and lead to tough decisions in the short-run.

5. Conclusion

COVID-19 undeniably disrupts whole industries, increasing uncertainty for long-term planning. Thus, management of uncertainty is vital for the long-term success of organizations. COVID-19 embodies a strong call for long-term thinking. COVID-19 means high levels of uncertainty for aviation managers. This uncertainty might paralyze humans and lets them think in assumptions that might be too ambiguous for actual management. Anxiety and fear of the unknown kicks in, whereas most cannot imagine an upside during such shocks. Managers become paralyzed, caught in a state of unproductive uncertainty. Therefore, strategizing may be more critical than ever before within the aviation industry, to secure short-term operations, but also to prepare the organization for future shocks from today on. The author of this paper asked the following main research question: how to make plans for environmental shocks such as COVID-19 to reduce the exposure to the risks that such shocks pose as well as to innovate strategically, adapt and emerge successfully from shocks?

This paper calls for strategic action in times of environmental uncertainty. The author of this paper bases his findings on the main theories and frameworks of strategic management literature and praxis. The main recommendations for aviation managers include the following: first, they should strategically orient or reorient with a turnaround strategy of retrenchment or recovery. Second, they should not exaggerate the current, short-term developments, because of unproductive uncertainty. Further, and to prepare for future environmental shocks, aviation managers need to develop a common strategy language, introduce uncertainty as a standard factor for long-term planning, manage uncertainty proactively and make long-term plans accordingly. They should foster a continuous dialogue with formal & informal strategy meetings on various levels of the organization and with various stake- and shareholders. While doing so, they need to be aware of the strategy tools being used and make the board a co-creating team. If the board does not have the necessary capabilities and experience, they should compose it differently and diversely. Finally, aviation managers should introduce a three-step process to sense, seize and transform the organization according to the environmental change. Managers should address the following questions proactively: who (roles and involvement) is responsible for strategizing? When (process), how (interactions), how regular, for how long, with whom, and with what tools does strategy happen in the organization? Addressing these questions will help aviation managers to use uncertainty proactively and productively, make plans during times of environmental shocks, and strategically innovate, adapt and emerge successfully from shocks. Also, these theories and frameworks will enable aviation managers to be well-prepared for future shocks through creating a shared understanding for long-term planning as well as by developing a more resilient organization that is better prepared for such high levels of uncertainty.

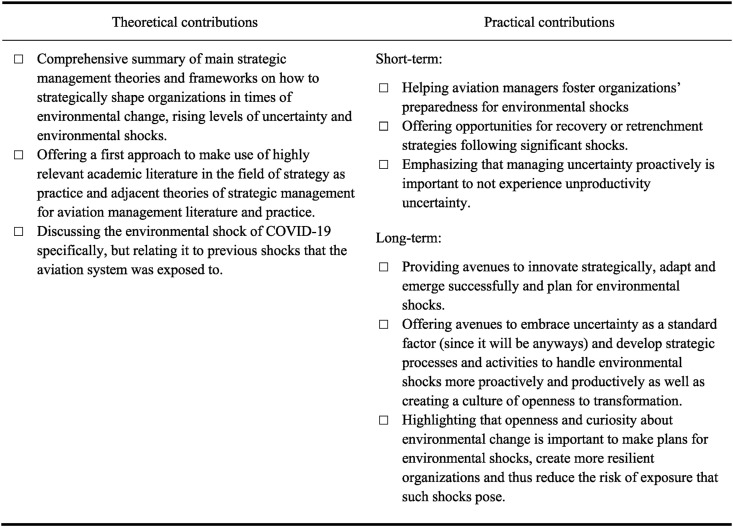

This article contributes theoretically by offering a comprehensive summary of main strategic management theories and frameworks on how to strategically shape organizations in times of environmental change, rising levels of uncertainty and environmental shocks. Further, by discussing main theories and frameworks of strategic management and apply them to the aviation industry, this paper offers a first approach to make use of highly relevant academic literature in the field of strategy as practice and adjacent theories of strategic management for aviation management literature and practice. Also, this paper offers an extensive discussion of these theories and frameworks with a focus on one specific environmental shock that is COVID-19. At the same time, the paper relates this specific shock to prior environmental shocks that the aviation system was exposed to, thus discussing possible relationships that might be important for long-term planning and acting of aviation managers.

From a practical viewpoint, this paper contributes by helping aviation managers foster organizations’ preparedness for environmental shocks as well as offering opportunities for recovery or turnaround strategies following significant shocks, such as COVID-19. These activities and frameworks might help aviation managers during times of environmental shocks and in the short-run. Additionally, the paper provides avenues for aviation managers to innovate strategically, adapt and emerge successfully from environmental shocks, such as COVID-19, and plan for environmental shocks in the long-run. The frameworks and tools might be used hands-on by aviation managers to embrace uncertainty as a standard factor for aviation organizations (since it will be anyways) and develop strategic processes and activities to handle environmental shocks more proactively and productively as well as creating a culture of openness to transformation. Being open and curious about environmental change and embracing as well as managing uncertainty proactively might help aviation managers to make plans for such environmental shocks, create more resilient organizations and thus reduce the risk of exposure that such shocks pose in the long-run, too Table 1 .

Table 1.

Theoretical and practical contributions of this paper.

| Theoretical contributions | Practical contributions |

|---|---|

|

|

Despite the theoretical and practical recommendations for long-term planning during times of shocks and preparing for future shocks, COVID-19 clearly shows that short-term thinking is vital as well. Managers need to secure financial liquidity and the continuance of the operation. This might be more important than long-term planning in certain situations, such as at the beginning of a shock. While this paper calls for more long-term thinking, specific short-term measures taken by airline managers are unavoidable and vital, too. These consist of, e.g., securing liquidity to sustain the airline's business in the short term. Otherwise, the best long-term strategy is useless. Nevertheless, the theories and frameworks also offer solutions to prepare for future shocks by creating a more resilient organization. Thus, in the best case and in times of future shocks, these short-term, more operative decisions, might be dealt with more easily.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Biography

Erik is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland. His research focuses on long-term planning, with a particular focus on strategy-as-practice, strategy processes, business models, business plans, future research as well as aviation and transportation management. He studied Business Management at the University of St. Gallen and has a professional business background in transportation management, business management, and public transport. Further, he is currently Managing Director of the Swiss Aerospace Cluster and lecturer at various Universities and Universities of Applied Sciences. He is the founder of the Special Interest Group (SIG) of “Strategic Management” within the Air Transport Research Society (ATRS), dedicated to research long-term planning in the aviation industry.

Footnotes

The term originates from the author Nassim Nicholas Taleb, N.N., 2007. The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable. Random house. He uses the term to describe extreme impact of rare and unpredictable outlier events and the human tendency to find simplistic explanations for these events, retrospectively - such as financial crises.

In 1921, Knight, F., 1921. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit, Mifflin, Boston, New York.distinguished uncertainty as being a lack of knowledge which is immeasurable and impossible to calculate from risk which is calculable and fundamental uncertainty as literal ambiguity. This definition of uncertainty is since then referred to as Knightian uncertainty.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.Ibid.

The term was introduced by Nathan Furr in his HBR article “Don't Let Uncertainty Paralyze You” in April 2020.

According to the stakeholder management approach for strategic management, among others by Freeman, R.E., McVea, J., 2005. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management, 183–201. And Buysse, K., Verbeke, A., 2003. Proactive Environmental Strategies: A Stakeholder Management Perspective. Strategic Management Journal 24, 453–470. This is especially important in industries, which are highly dependent on main actors and dynamic in nature, such as the aviation industry.

Long-term planning is one of the major tasks the board in accordance with OR 716a of the Swiss Code of Obligations (OR). See more details to the role and duties of Swiss boards in Müller, R., Lipp, L., Plüss, A., 2014. Der Verwaltungsrat: Ein Handbuch für Theorie und Praxis Schulthess, Zurich. This is comparable to other board-systems such as, e.g., the management board in the US and many other national contexts, where the board plays a major role in strategizing.

See Cossin, D., Metayer, E., 2014. How strategic is your board? MIT Sloan Review. In their article on “How Strategic Is Your Board?” in the MIT Sloan Management Review. See also Fig. 4, which has been designed according to their article.

Roles for communication are delegable. But it is important to define who communicates, how and to whom.

A performance indicator or key performance indicator (KPI) is a type of performance measurement to evaluate the success of an organization or of a particular activity (such as projects, programs, products, events and other initiatives) in which it engages

Appendix A1. Checklist for aviation managers to make long-term plans to use during times of environmental shocks and to prepare for them

This checklist is ought to be seen as a literal aviation checklist for long-term planners of aviation organizations in times of environmental change and shocks. Strategic managers may use this checklist for long-term planning during and after environmental shocks and in times of environmental uncertainty:

During an environmental shock:

-

□

Not exaggerate the current, short-term developments, because of unproductive uncertainty.

-

□

Introduce a three-step process to embrace uncertainty in the organization by sensing changes, seizing opportunities, and transforming the organization accordingly.

To prepare for future environmental shocks:

-

□

Develop a common strategy language, introduce uncertainty as a standard factor for long-term planning, manage uncertainty proactively and make long-term plans accordingly.

-

□

Foster a continuous dialogue with formal & informal strategy meetings on various levels of the organization and with various stakeholders.

-

□

Be aware of the strategy tools being used, they might be vital for the success of long-term planning and other organizational outcomes.

-

□

Make the board a co-creating team. If the board does not have the necessary capabilities and experience, compose it differently and heterogeneously.

PREPARING FOR FUTURE SHOCKS.

-

❑

Develop a common strategy language, introduce uncertainty as a standard factor for long-term planning, manage uncertainty proactively and make long-term plans accordingly.

-

❑

Foster a continuous dialogue with formal & informal strategy meetings on various levels of the organization and with various stake- and shareholders.

-

❑

Be aware of the strategy tools being used, they might be vital for the success of long-term planning and other organizational outcomes.

-

❑

Make the board a co-creating team. If the board does not have the necessary capabilities and experience, compose it differently and diversely.

-

❑

Introduce a three-step process to embrace uncertainty in the organization by sensing changes, seizing opportunities, and transforming the organization accordingly.

DURING TIMES OF SHOCKS.

-

❑

Strategically orient or reorient with a turnaround strategy of retrenchment or recovery

-

❑

Not exaggerate the current, short-term developments, because of unproductive uncertainty.

References

- Åberg C., Shen W. Can board leadership contribute to board dynamic managerial capabilities? An empirical exploration among Norwegian firms. J. Manag. Govern. 2019:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts D.S. Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University; Washington, DC: 1996. The Unintended Consequences of Information Age Technologies: Avoiding the Pitfalls, Seizing the Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Ale Ebrahim N., Ahmed S., Taha Z. 2009. Virtual Teams: a Literature Review. [Google Scholar]

- Allaire Y., Firsirotu M.E. Coping with strategic uncertainty. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1989;30:7. [Google Scholar]

- Amram M., Kulatilaka N. Uncertainty: the new rules for strategy. J. Bus. Strat. 1999;20:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aragón-Correa J.A., Sharma S. A contingent resource-based view of proactive corporate environmental strategy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003;28:71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Arogyaswamy K., Barker V.L., Yasai‐Ardekani M. Firm turnarounds: an integrative two‐stage model. J. Manag. Stud. 1995;32:493–525. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun J., Jacobs C., Jarzabkowski P., Mantere S., Vaara E. Placing strategy discourse in context: sociomateriality, sensemaking, and power. J. Manag. Stud. 2014;51:175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Baran B.E., Scott C.W. Organizing ambiguity: a grounded theory of leadership and sensemaking within dangerous contexts. Mil. Psychol. 2010;22:S42–S69. [Google Scholar]

- Barker V.L., III, Duhaime I.M. Strategic change in the turnaround process: theory and empirical evidence. Strat. Manag. J. 1997;18:13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Becker M.C., Knudsen T. The role of routines in reducing pervasive uncertainty. J. Bus. Res. 2005;58:746–757. [Google Scholar]

- Becker M.C., Zirpoli F. Applying organizational routines in analyzing the behavior of organizations. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008;66:128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund H. Researching entrepreneurship as lived experience. Handb of qual res methods entrepren. 2007;3:75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Betsch T., Brinkmann B.J., Fiedler K., Breining K. When prior knowledge overrules new evidence: adaptive use of decision strategies and the role of behavioral routines. Swiss Journal of Psychology/Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Revue Suisse de Psychologie. 1999;58:151. [Google Scholar]

- Betsch T., Haberstroh S. Psychology Press; 2014. The Routines of Decision Making. [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw J., Zimmermann A., Raisch S. How do firms adapt to discontinuous change? Bridging the dynamic capabilities and ambidexterity perspectives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016;58:36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Blome C., Schoenherr T., Rexhausen D. Antecedents and enablers of supply chain agility and its effect on performance: a dynamic capabilities perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013;51:1295–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Bode C., Wagner S.M., Petersen K.J., Ellram L.M. Understanding responses to supply chain disruptions: insights from information processing and resource dependence perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2011;54:833–856. [Google Scholar]

- Busenitz L.W., Barney J.B. Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. J. Bus. Ventur. 1997;12:9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse K., Verbeke A. Proactive environmental strategies: a stakeholder management perspective. Strat. Manag. J. 2003;24:453–470. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M.A., Geletkanycz M.A., Sanders W.G. Upper echelons research revisited: antecedents, elements, and consequences of top management team composition. J. Manag. 2004;30:749–778. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M.A., Westphal J.D. The strategic context of external network ties: examining the impact of director appointments on board involvement in strategic decision making. Acad. Manag. J. 2001;44:639–660. [Google Scholar]

- Carton A.M. “I'm not mopping the floors, I'm putting a man on the moon”: how NASA leaders enhanced the meaningfulness of work by changing the meaning of work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2017;63:323–369. [Google Scholar]

- Chaharbaghi K., Adcroft A., Willis R., Walsh P.R. Dealing with the uncertainties of environmental change by adding scenario planning to the strategy reformulation equation. Manag. Decis. 2005;43(1):113–122. doi: 10.1108/00251740510572524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Hambrick D.C. CEO replacement in turnaround situations: executive (mis) fit and its performance implications. Organ. Sci. 2012;23:225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough H.W., Appleyard M.M. Open innovation and strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007;50:57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell S., Berkhout F., Tuinstra W., Tàbara J.D., Jäger J., Chabay I., de Wit B., Langlais R., Mills D., Moll P., Otto I.M., Petersen A., Pohl C., van Kerkhoff L. Opening up knowledge systems for better responses to global environmental change. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2013;28:60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cossin D., Metayer E. How strategic is your board? MIT Sloan Review. 2014;56(1) [Google Scholar]

- Day G.S., Schoemaker P.J.H. Adapting to fast-changing markets and technologies. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016;58:59–77. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J., Wardekker J.A., van der Sluijs J.P. Frame-based guide to situated decision-making on climate change. Global Environ. Change. 2010;20:502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte . 2020. COVID-19: a black swan event for the semiconductor industry? [Google Scholar]

- Dibrell C., Craig J.B., Neubaum D.O. Linking the formal strategic planning process, planning flexibility, and innovativeness to firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2014;67:2000–2007. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio P. The new institutionalisms: avenues of collaboration. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft. 1998;154:696–705. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S., Meyer K., Day M. Building dynamic capabilities of adaptation and innovation: a study of micro-foundations in a transition economy. Long. Range Plan. 2014;47:186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson L. Springer; 2006. The Contingency Theory of Organizational Design: Challenges and Opportunities, Organization Design; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson L. Oxford University Press; 2013. Structural Contingency Theory/Information Processing Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt K.M., Furr N.R., Bingham C.B. CROSSROADS—microfoundations of performance: balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organ. Sci. 2010;21:1263–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S., Shpielberg N. Organizational learning mechanisms and managers' perceived uncertainty. Hum. Relat. 2003;56:1233–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Fainshmidt S., Frazier M.L. What facilitates dynamic capabilities? The role of organizational climate for trust. Long. Range Plan. 2017;50:550–566. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton C., Langley A. Strategy as practice and the narrative turn. Organ. Stud. 2011;32:1171–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Ford R.C., Piccolo R.F., Ford L.R. Strategies for building effective virtual teams: trust is key. Bus. Horiz. 2017;60:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R.E., McVea J. The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; 2005. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Furr N. Don't let uncertainty paralyze You. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Gardner H.K., Peterson R.S. Executives and boards, avoid these missteps in a crisis. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Garg S., Eisenhardt K.M. Unpacking the CEO–board relationship: how strategy making happens in entrepreneurial firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2017;60:1828–1858. [Google Scholar]

- Gino F. 2018. The Business Case for Curiosity. [Google Scholar]

- Godet M. The art of scenarios and strategic planning: tools and pitfalls. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2000;65:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson S.V., Merkert R. Call for papers: Journal of Air Transport Management: Special issue: managing for pandemics and economic shocks in air transport: the future of the aviation industry in a post-COVID-19 world. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020 https://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-air-transport-management/call-for-papers/the-future-of-the-aviation-industry-in-a-post-covid-19-world [Google Scholar]

- Gulati R., Nohria N., Wohlgezogen F. Roaring out of recession. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010:63–69. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick D.C. Environmental scanning and organizational strategy. Strat. Manag. J. 1982;3:159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick D.C., Werder A.v., Zajac E.J. New directions in corporate governance research. Organ. Sci. 2008;19:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey M., Novicevic M., Leonard N., Payne D. The role of curiosity in global managers' decision-making. J. Leader. Organ Stud. 2007;13:43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hautz J., Seidl D., Whittington R. Open strategy: dimensions, dilemmas, dynamics. Long. Range Plan. 2017;50:298–309. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat C.E., Peteraf M.A. Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strat. Manag. J. 2015;36:831–850. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström T. The science-policy dialogue in transformation: model-uncertainty and environmental policy. Sci. Publ. Pol. 1996;23:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry J. Strategic decision mking, discourse, and strategy as social practice. J. Manag. Stud. 2000;37:955–978. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry K.P., Kiel G.C., Nicholson G. How boards strategise: a strategy as practice view. Long. Range Plan. 2010;43:33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson G.P., Healey M.P. Psychological foundations of dynamic capabilities: reflexion and reflection in strategic management. Strat. Manag. J. 2011;32:1500–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson G.P., Maule A.J., Bown N.J., Pearman A.D., Glaister K.W. Further reflections on the elimination of framing bias in strategic decision making. Strat. Manag. J. 2002;23:1069–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Ingley C.B., Van der Walt N.T. The strategic board: the changing role of directors in developing and maintaining corporate capability. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 2001;9:174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzabkowski P. Strategy as practice: recursiveness, adaptation, and practices-in-use. Organ. Stud. 2004;25:529–560. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzabkowski P. Sage; 2005. Strategy as Practice: an Activity Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzabkowski P., Kaplan S. Strategy tools-in-use: a framework for understanding “technologies of rationality” in practice. Strat. Manag. J. 2015;36:537–558. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzabkowski P., Paul Spee A. Strategy‐as‐practice: a review and future directions for the field. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2009;11:69–95. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G. Pearson Education; 2016. Exploring Strategy: Text and Cases. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G., Prashantham S., Floyd S.W., Bourque N. The ritualization of strategy workshops. Organ. Stud. 2010;31:1589–1618. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G., Smith S., Codling B. Cambridge handbook of strategy as practice; 2010. Institutional Change and Strategic Agency: an Empirical Analysis of Managers' Experimentation with Routines in Strategic Decision Making; pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. Avoiding decision paralysis in the face of uncertainty. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Judge W.Q., Talaulicar T. Board involvement in the strategic decision making process: a comprehensive review. Annals of Corporate Governance. 2017;2:51–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter R.M. Leading your team past the peak of a crisis. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S. Framing contests: strategy making under uncertainty. Organ. Sci. 2008;19:729–752. [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Burns M.L., Prescott J.E. The strategic role of the board: the impact of board structure on top management team strategic action capability. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 2009;17:728–743. [Google Scholar]

- Kindström D., Kowalkowski C., Sandberg E. Enabling service innovation: a dynamic capabilities approach. J. Bus. Res. 2013;66:1063–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Knight F. Mifflin; Boston, New York: 1921. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. [Google Scholar]

- Kornberger M., Clegg S. Strategy as performative practice: the case of Sydney 2030. Strat. Organ. 2011;9:136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kreamer L., Rogelberg S.G. Break up your big virtual meetings. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Krys C. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. Scenario-based Strategic Planning: Developing Strategies in an Uncertain World. [Google Scholar]

- Kukalis S. Determinants of strategic planning systems in large organizations: a contingency approach. J. Manag. Stud. 1991;28:143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon W., Clarke I., Wodak R. Micro-level discursive strategies for constructing shared views around strategic issues in team meetings. J. Manag. Stud. 2014;51:265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton T., Rajwani T., O’Kane C. Strategic reorientation and business turnaround: the case of global legacy airlines. Journal of Strategy and Management. 2011;4(3):215–237. doi: 10.1108/17554251111152252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc R., Gillies J. John Wiley & Sons; 2005. Inside the Boardroom: How Boards Really Work and the Coming Revolution in Corporate Governance. [Google Scholar]

- Li D.-y., Liu J. Dynamic capabilities, environmental dynamism, and competitive advantage: evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 2014;67:2793–2799. [Google Scholar]