Abstract

This survey investigated the effect of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the clinical practice of endodontics among the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) members by evaluating the impact on clinical activities, patient screening, infection control measurements, potential transmission, clinical protocols, as well as psychological concerns. A descriptive, cross-sectional survey was developed to query AAE members from all 7 districts. The survey consisted of 24 questions, 8 demographic questions and 16 questions related to the COVID-19 pandemic impact on the clinical practice. A total of 454 AAE members participated in the survey. As of July 2020, most endodontists were active in front-line treatment of dental patients (82%). N95 respirator face mask was described by 83.1% of the participants as special measures beyond the regular personal protective equipment. Rubber dam isolation was recognized by the majority of the participants at some level to reduce the chance of COVID-19 cross infection. Most of the endodontist participants acknowledged trauma followed by swelling, pain, and postoperative complication to be emergencies. The majority of respondents reported being concerned about the effect of COVID-19 on their practice. No differences in worries about COVID-19 infection were related to demographics (P > .05). The majority of the endodontists are aware of the COVID-19 pandemic, are taking special precautions, and are concerned about contracting and spreading the virus. Despite the conflict between their roles as health care providers and family members with the potential risk of exposing their families, most of them remain on duty providing front-line care for dental treatment.

Key Words: COVID-19, dental, endodontics, root canal, SARS-CoV-2

Significance.

Endodontists need to be aware and prepared for root canal treatment during COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Additional protection measurements than PPE are needed. Endodontists must comply with the guidelines released by the World Health Organization and dental associations.

There was an outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in late December 20191. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency of international concern over this pandemic outbreak on January 30, 2020. Since then, the number of cases and confirmed deaths has increased globally, as indicated by the weekly operational update COVID-19 provided by WHO2 , 3.

As of now (August 21, 2020), there have been 21,294,845 cases confirmed and 761,779 deaths2. There is an interactive map of the global cases of COVID-19 by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, which is continually updated3.

The COVID-19 disease is caused by the novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome–associated coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2, formerly known as 2019-nCoV)4. The most commonly reported routes of SARS-CoV-2 transmission are inhalation or direct inoculation5. The inhalation may occur from respiratory droplets or aerosols from infected individuals within a 6-foot radius. In addition, the direct inoculation of SARS-CoV-2 infected particles occurs by touching surfaces contaminated with infected respiratory droplets as transmission via an inanimate vector5.

Because of the dual risk of high aerosol-generating procedures in dentistry plus saliva-borne SARS-CoV-2 in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, dental societies/associations immediately responded to the COVID-19 disease. The response of dental associations to curb the clinic-associated nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 varied at that time. At the early stage of the pandemic, the Public Health England under the guidance of the Chief Dental Officer6 recommended not providing aerosol-generating procedures. Instead, they were screening and sending true emergencies to a central location where dentists were carrying out aerosol-generating procedures. In contrast, the American Dental Association guidelines at that time7 restricted dental treatment to only addressing emergencies and reducing the number of routine check-ups and follow-up appointments. Despite the guidance, practitioners were still reluctant and felt fearful of treating patients in such a situation.

Endodontists are in a unique situation because they manage odontogenic pain, swelling, and dental alveolar trauma. Because of the chances to encounter patients suspected or confirmed with SARS-CoV-2, they had to act diligently to provide care and at the same time prevent nosocomial spread of the infection. For that, endodontists had to adopt special measurements to screen their patients, enhance infection control measurements, and follow specific dental treatment recommendations.

Here we assess endodontists’ knowledge and awareness about COVID-19 disease. In addition, we evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on clinical activities, patient screening, infection control measurements, potential transmission, clinical protocols, and psychological concerns on the clinical practice of endodontists across the United States.

Materials and Methods

This survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (#HP-00092103). A descriptive, cross-sectional survey was generated through Qualtrics (http://umaryland.qualtrics.com). The study population consisted of 5191 selected members of the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) from all 7 districts (I–VII) in the United States listed in the AAE directory website (2019–2020 membership directory). Invitations to participate in the study were emailed to each participant in June 2020. The invitations were sent 2 times, with 2 weeks apart. The survey remained open for 1 month, and afterward, data were collected. The data were collected in July 2020. The questions for this questionnaire were developed mostly on the basis of COVID-19 guidelines published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WHO, American Dental Association, and Journal of Endodontics. The survey instruments consisted of 2 sections with a total of 24 questions. The first section of the questionnaire comprised 8 demographic questions and 16 questions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic impact in the clinical practice of endodontists (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Demographic and COVID-19 Related Questions and Answers

| Section 1: Demographic questions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | What is your gender? | n = 444 | |||

| Male | 324 (73%) | ||||

| Female | 120 (27%) | ||||

| Other | 0 | ||||

| Q2 | How many years have you been in practice? | n = 447 | |||

| 0–5 | 61 (13.6%) | ||||

| 6–10 | 62 (13.9%) | ||||

| 11–20 | 109 (24.4%) | ||||

| 21–30 | 85 (19%) | ||||

| 31–40 | 84 (18.8%) | ||||

| More than 40 | 46 (10.3%) | ||||

| Q3 | What best describes the nature of your practice? | n = 443 | |||

| Solo endodontist | 170 (38.4%) | Other specified (2.7%) | |||

| Group of endodontists | 182 (41.1%) | Full-time practice 32 y and full-time academia 18 y | 7 | ||

| Corporate | 19 (4.3%) | Retired | 1 | ||

| Military | 11 (2.5%) | VA | 1 | ||

| Multi-specialty | 10 (2.3%) | Locum tenens/part-time educator | 1 | ||

| Community/public health | 0 | 1 | |||

| Faculty practice | 8 (1.8%) | General practice office in-house endodontics and part-time teaching | 1 | ||

| Full-time educator | 19 (4.3%) | ||||

| Part-time educator | 9 (2.0%) | ||||

| Volunteer educator | 0 | ||||

| No teaching | 1 (0.2%) | ||||

| Hospital | 2 (0.5%) | ||||

| Other | 12 (2.7%) | ||||

| Q4 | Which best describes the nature of your practice? | n = 454 | |||

| Endodontist | 454 (100%) | ||||

| General dentist providing endodontic treatment | 0 | ||||

| Oral surgeon providing endodontic treatment | 0 | ||||

| Periodontist providing endodontic treatment | 0 | ||||

| Pediatric dentist providing endodontic treatment | 0 | ||||

| Q5 | How would you describe the location of your practice? | n = 446 | |||

| Rural | 33 (7.4%) | ||||

| Urban | 168 (37.7%) | ||||

| Suburban | 245 (54.9%) | ||||

| Q6 | In which state do you currently reside? | n = 381 | |||

| AL, AK, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, DC, FL, GA, HI, ID, IL | AL (n = 2), AK (n = 1), AZ (n = 13), AR (n = 3), CA (n = 48), CO (n = 12), CT (n = 4) | ||||

| IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, Ml, MN, MS, MO, MT | DE (n = 0), DC (n = 2), DE (n = 0), FL (n = 13), GA (n = 6), HI (n = 2), ID (n = 5), IL (n = 15) | ||||

| NE, NV, NH, NJ, NM, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, PR | IN (n = 8), IA (n = 1), KS (n = 2), KY (n = 2), LA (n = 3), ME (n = 1), MD (n = 19) | ||||

| RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY | MA (n = 10), MI (n = 10), MN (n = 10), MS (n = 0), MO (n = 10), MT (n = 1), NE (n = 0) | ||||

| NV (n = 4), NH (n = 2), NJ (n = 9), NM (n = 3), NY (n = 21), NC (n = 19), ND (n = 1) | |||||

| OH (n = 14), OK (n = 0), OR (n = 10), PA (n = 18), PR (n = 1), RI (n = 0), SC (n = 7) | |||||

| SD (n = 0), TN (n = 7), TX (n = 23), UT (n = 2), VT (n = 1), VA (n = 12), WA (n = 7) | |||||

| WV (n = 4), WI (n = 0), WY (n = 2) | |||||

| Q7 | In which AAE district do you currently reside? | n = 395 | |||

| I (DE, DC, MA, MD, ME, NH, PA, VT, VA) | 65 (16.5%) | ||||

| II (CT, NJ, NY, RI) | 37 (9.4%) | ||||

| III (FL, GA, NC, SC, TN) | 58 (14.7%) | ||||

| IV (IL, IN, KY, MI, OH, WV, IN) | 59 (14.9%) | ||||

| V (AL, AR, AZ, LA, MS, NM, OK, PR, TX, VI, United States Armed Services, Veteran's Administration) | 54 (13.7%) | ||||

| Army, Navy, Veterans Administration, Virgin Islands | |||||

| VI (AK, CO, Guam, HI, ID, IA, KS, MN, MO, MT, NE | 70 (17.7%) | ||||

| NV, ND, OR, SD, UT, WA, WY) | |||||

| VII (CA) | 52 (13.2%) | ||||

| Q8 | Are you Board Certified? | n = 395 | |||

| Yes | 148 (37.5%) | ||||

| Eligible | 173 (43.8%) | ||||

| None | 74 (18.7%) | ||||

| Section 2: COVID-19 pandemic-related questions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q9 | Have you returned to your practice? | n = 397 | |||

| No | 19 (4.8%) | ||||

| 25% | 9 (2.3%) | ||||

| 50% | 25 (6.3%) | ||||

| 75% | 41 (10.3%) | ||||

| 100% | 299 (75.3%) | ||||

| Emergency only | 4 (1%) | ||||

| Q10 | Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the number of patients in your practice when compared with the same time a year ago? | n = 395 | |||

| No effect | 94 (24%) | ||||

| Decrease | 284 (72%) | ||||

| Increase | 17 (4%) | ||||

| Q11 | Are you taking part in endodontic care in front-line treatment of dental patients? | n = 397 | |||

| Yes | 322 (82%) | ||||

| No | 69 (18%) | ||||

| Q12 | What do you classify as an emergency? | n = 397 | |||

| Please select all that apply | Swelling | 325 (81.9%) | |||

| Trauma | 326 (82.1%) | ||||

| Pain | 302 (76.1%) | ||||

| Postoperative complication | 237 (59.7%) | ||||

| Loss of crown or temporary filling | 79 (19.9%) | ||||

| All of the above | 139 (35%) | ||||

| Q13 | Which best describe your current patient COVID-19 screening techniques? | n = 396 | |||

| Please select all that apply | Written questionnaire | 307 (77.5%) | |||

| Oral questions | 349 (88%) | ||||

| Taking patient body temperature | 373 (94.2%) | ||||

| RT-PCR | 8 (2%) | ||||

| Another paid COVID-19 test | 3 (0.7%) | ||||

| Chest x-ray | 0 | ||||

| Q14 | Which of the following do you identify as a positive response in your current patient screening techniques? | n = 397 | |||

| Please select all that apply | Body temperature higher than 100°F (38°C) | 371 (93.5%) | Other specified | ||

| Cough | 352 (88.7%) | COVID-19 test ordered all aerosol-generating | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Sore throat | 281 (70.8%) | procedures | |||

| Shortness of breath | 339 (85.4%) | Temperature 100.4°F | 2 (0.5%) | ||

| Flu-like symptoms | 376 (94.7%) | Temperature over 101°F | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Muscle pain | 207 (52.1%) | COVID or no COVID, I would not want to see | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Red or painful eyes, itching, or scratchy eyes | 102 (25.7%) | patients with any symptoms | |||

| Vomiting, diarrhea, stomach pain | 234 (58.9%) | Diagnosis within the last 2 weeks of COVID-19 | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Loss of smell | 349 (87.9%) | ||||

| Runny nose | 162 (40.8%) | ||||

| Changes in toe or new toe condition | 78 (19.6%) | ||||

| Around someone diagnosed with COVID-19 | 327 (82.4%) | ||||

| Pulse oximeter below 90% | 132 (33.2%) | ||||

| Travel history | 298 (75.1%) | ||||

| Other (please specify) | 6 (1.5%) | ||||

| Q15 | Are patients cooperative with added screening measures? | n = 391 | |||

| Yes | 385 (98%) | ||||

| No | 6 (2%) | ||||

| Q16 | Which of the following best describe the special measures you are now taking beyond regular PPE? | n = 397 | |||

| Please select all that apply | N95 respirator face mask | 330 (83.1%) | Other specified (9.8%) | ||

| Face shield | 234 (58.9%) | Plastic shield from the microscope | 1 | ||

| Protective suit | 146 (36.8%) | Retired | 1 | ||

| Head cover | 219 (55.2%) | Closed eye goggles | 1 | ||

| Shoe covers | 62 (15.6%) | Respirator mask | 1 | ||

| Oral aerosol vacuum | 67 (16.9%) | Level 3 surgical mask | 1 | ||

| Plexiglass aerosol shield for microscope | 114 (28.7%) | Just go fogger | 1 | ||

| Cold fogging | 38 (9.6%) | Window fan exhausting outdoors | 1 | ||

| Negative pressure operatory for treating COVID-19 | 13 (3.3%) | Goggles | |||

| positive or suspected patients | Air purifier in building central air | 1 | |||

| Air purifying unit | 168 (42.3%) | K95 | 1 | ||

| Nothing special | 23 (5.8%) | UVC light for OP disinfection | 1 | ||

| Other | 39 (9.8%) | K95 mask due to lack of N95 availability | 1 | ||

| Ventilation units | 1 | ||||

| Oral pre-rinse, bathe the tooth with rubbing alcohol | 1 | ||||

| and sodium hypochlorite after placing dental can | |||||

| and before using high speed | |||||

| UV light in between patients | 1 | ||||

| Q17 | Are you concerned about contracting or spreading SARS-CoV-2? | n = 374 | |||

| Strongly agree | 147 (39.3%) | ||||

| Agree | 92 (24.6%) | ||||

| Somewhat agree | 65 (17.4%) | ||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 23 (6.1%) | ||||

| Somewhat disagree | 14 (3.7%) | ||||

| Disagree | 19 (5.1%) | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 14 (3.7%) | ||||

| Q18 | Do you believe the rubber dam reduces the chance of COVID-19 cross infection from routine endodontic procedure? | n = 373 | |||

| Strongly agree | 110 (29.5%) | ||||

| Agree | 124 (33.2%) | ||||

| Somewhat agree | 100 (26.8%) | ||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 12 (3.20%) | ||||

| Somewhat disagree | 11 (2.9%) | ||||

| Disagree | 12 (3.2%) | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 4 (1.1%) | ||||

| Q19 | Are you worried about the effect of COVID-19 on your practice of endodontics? | n = 374 | |||

| Yes | 298 (80%) | ||||

| No | 76 (20%) | ||||

| Q20 | What is the reason behind your worries? | n = 396 | |||

| Please select all that apply | I will become infected | 243 (23.7%) | |||

| My family will become infected | 262 (25.5%) | ||||

| My staff will become infected | 287 (28%) | ||||

| My patients will become infected | 234 (22.8%) | ||||

| Q21 | Do you agree with the COVID-19 phase in your state? | n = 374 | |||

| Strongly agree | 59 (15.8%) | ||||

| Agree | 142 (38%) | ||||

| Somewhat agree | 79 (21.1%) | ||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 25 (6.7%) | ||||

| Somewhat disagree | 17 (4.5%) | ||||

| Disagree | 30 (8%) | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 22 (5.9%) | ||||

| Q22 | In what phase of COVID-19 recovery is your state? | n = 354 | |||

| 1 | 26 (7.3%) | ||||

| 2 | 124 (35%) | ||||

| 3 | 110 (31.1% | ||||

| 4 | 45 (12.7%) | ||||

| 5 | 2 (0.6%) | ||||

| 6 | 1 (0.3%) | ||||

| Other | 46 (13%) | ||||

| Q23 | Are staff worried about chronic effects of COVID-19? | n = 374 | |||

| Strongly agree | 69 (18.4%) | Other specified (0.5%) | |||

| Agree | 113 (30.2%) | My staff enjoys being on unemployment and will not | 1 | ||

| Somewhat agree | 78 (20.9%) | return. I have sold my practice and am now retired. | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 61 (16.3%) | Unsure | 1 | ||

| Somewhat disagree | 14 (3.7%) | ||||

| Disagree | 30 (8%) | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 7 (1.9%) | ||||

| Other | 2 (0.5%) | ||||

| Q24 | Please rate the order of importance of the following protection measuresagainst COVID-19. | n = 369 | |||

| N95 respirator face mask, hand wash, hand sanitizer | 200 (54.2%) | ||||

| Hand wash, hand sanitizer, N95 respirator face mask | 74 (20.1%) | ||||

| Hand sanitizer, N95 respirator face mask, hand wash | 10 (2.7%) | ||||

| Hand sanitizer, hand wash, N95 respirator face mask | 5 (1.4%) | ||||

| Hand wash, N95 respirator face mask, hand sanitizer | 65 (17.6%) | ||||

| N95 respirator face mask, hand sanitizer, hand wash | 15 (4.1%) | ||||

Data Analysis

All data were transferred from the Qualtrics forms into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and analyzed with the Statistical Package of the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 25; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were used for the analysis. The generalized linear model with binary logistic regression was performed to explore the factors associated with the effect of COVID-19 on the clinical practice of endodontics and the independent variables including gender, years of experience, type of practice, location, nature of practice, participation in education, board certification, and practicing district. A P value less than .05 was considered significant (P < .05).

Results

From the 5191 invited to take the survey from all 7 AAE districts, 454 participated in the survey. Despite efforts through the survey design to prevent skipping questions, some respondents did not answer all the questions. A total of 324 men and 120 women participated in this survey (Table 1). A total of 324 respondents had practiced for more than 10 years. A greater number of respondents belonged to AAE District VI (70/395, 17.7%), I (65/395, 16.5%), followed by IV (59/454, 14.9%), and III (58/395, 14.7%) (Table 1). The 4 states with a greater number of participants were California, New York, followed by Maryland and North Carolina (Table 1). Most respondents have their practice located in the suburban (245/446, 54.9%) and urban (168/446, 37.7%) areas (Table 1). All participants were endodontists (454, 100%). Most of the respondents described their practice setting as a group of endodontists (182/443, 41.1%) and solo endodontist (170/443, 38.4%) (Table 1). The demographic information of participants is detailed in Table 1.

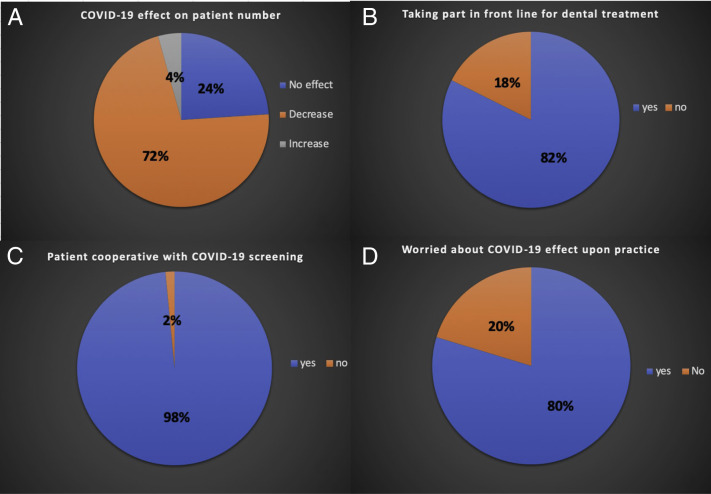

As of July 2020, 299/397 participants (75.3%) had fully resumed their practice, and 75/397 (18.9%) had partially returned to their practice. Only 19/397 (4.8%) had not returned to their practice (Table 1). From the participants who resumed their practice, 284/395 (72%) reported that the number of patients decreased compared with the same time a year ago. In comparison, only 17/454 (4%) reported no effect or an increase in the number of patients (Fig. 1 A). As of July 2020, most endodontists took part in endodontic care in the front-line treatment of dental patients (322/397, 82%) (Fig. 1 B). Most of the participants acknowledged trauma (326/397, 82.1%) followed by swelling (325/397, 81.9%), pain (302/397, 76.1%), and postoperative complication (237/397, 59.7%) to be emergencies. Thirty-five percent of the participants reported all of the above emergencies (139/397, 35%) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the number of patients in your practice when compared with the same time a year ago? (Question 10). (B) Are you taking part in endodontic care in front-line treatment of dental patients? (Question 11). (C) Are patients cooperative with added screening measures? (Question 15). (D) Are you worried about the effect of COVID-19 on your practice of endodontics? (Question 19).

The participants best described their current patient COVID-19 screening techniques as taking patient body temperature (373/396, 94.2%), and/or oral questions (349/396, 88%), and/or written questionnaire (307/396, 77.5%). Only a few participants (8/396, 2%) reported using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for COVID-19 screening. No respondent reported having requested chest x-ray for COVID-19 screening in dental practice. Most participants identified flu-like symptoms (376/397, 94.7%), body temperature > 100°F (371/397, 93.5%), cough (352/397, 88.7%), loss of smell (349/397, 87.9%), shortness of breath (339/397, 85.4%), being around someone diagnosed with COVID-19 (327/397, 82.4%), travel history (298/397, 75.1%), sore throat (281/397, 70.8%), as well as vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain (234/397, 58.9%) to be a positive response in their current patient screening technique (Table 1). Only 2% of the participants (6/454) reported uncooperative patients for the COVID-19 screening measurement adopted in their practice (Fig. 1 C). In addition to the regular personal protective equipment (PPE), 100% of the participants reported having taken special protective measures for routine root canal therapy, with the most common ones being the N95 respirator face mask (330/397, 83.1%), face shield (234/397, 58.9%), and head cover (219/397, 55.2%) (Table 1). In addition, some respondents (168/397, 42.3%) reported implementing an air-purifying unit in their operatory (Table 1). Other protective measurements were also reported by the respondents (Table 1).

Most participants agreed at some level to be concerned with contracting/spreading the COVID-19 virus. Rubber dam isolation was recognized by the majority of the participants at some level to reduce the chance of COVID-19 cross infection from routine endodontic procedures. Two hundred ninety-eight participants (298/374, 80%) reported being worried about the effect of COVID-19 on their practice (Fig. 1 D). The reasons behind their worries were mostly common staff and/or family becoming infected (Table 1). The majority of the participants agreed at different levels with the COVID-19 phase in their state. As of July 2020, most of the states were in phases 2 and 3 (Table 1). Most of the respondents agreed at some level that most of their staff worry about the chronic effects of COVID-19 (Table 1). The great majority of respondents ranked the order of most to least important protection measures against COVID-19 as an N95 mask, hand wash, and hand sanitizer (200/369, 54.2%) (Table 1). Our results indicated no significant differences in worries about COVID-19 infection related to gender, years of experience, type of practice, location, nature of the practice, and practicing district (P > .05).

Discussion

In this survey, endodontists who resumed their activities at some level as well as those who discontinued their practices shared that they were afraid of becoming infected, carrying infection from their dental practice to their families, staff becoming infected, as well as patient cross infection. Our results indicated no differences in worries about COVID-19 infection related to gender, years of experience, type of practice, location, nature of the practice, and practicing district (P > .05). Psychological distress, including the fear of becoming infected while treating a patient or passing the infection on to family, is one of the most common fears shared among practitioners8, 9, 10. Recently, Tysiąc-Miśta and Dziedzic10 reported a higher level of anxiety in those who suspended their clinical work than a dentist who continued their practice. The fear and anxiety are powerful emotions associated with the overwhelming reports on the COVID-19 pandemic by social, electronic, and print media.

From the endodontists who resumed their practice by July 2020, 72% of them reported that the number of patients decreased compared with the same time a year ago, whereas 24% of the endodontists said that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the number of patients attendance. In contrast, only 4% of the respondents reported an increase in the number of patients. Such variation may indirectly be due to the number of practitioners in operation at that time in their location. The reduction in the number of admitted patients is reported in the literature10.

The participants best described their patient COVID-19 screening techniques as taking patient body temperature, oral questions, and/or written questionnaires. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several screening questionnaires have been released by different dental associations and journals. Recently, Ather et al11 published in the Journal of Endodontics a COVID-19 screening questionnaire with 6 short questions. The authors also emphasized to the endodontic community the need to measure the patient’s body temperature by using a non-contact forehead thermometer or with cameras having infrared thermal sensors.

Although the diagnosis of COVID-19 relies on the detection of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA by real-time RT-PCR4 , 12 , 13, here only a few endodontists were using it as their patient screening technique. No endodontist participant requested chest x-ray for COVID-19 screening in their dental practice, although chest x-ray might show patchy shadows and ground-glass opacity in the lung14. It is worth pointing out that only a few participants reported uncooperative patients for the COVID-19 screening measurements adopted in their practice.

Patients with COVID-19 usually present with symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, fatigue, myalgia, headache, shortness of breath, and in some cases diarrhea11 , 15. Here most of the endodontists identified flu-like symptoms, body temperature higher than 100°F (38°C), loss of smell, shortness of breath, and being around someone diagnosed with COVID-19 as a positive response in their current patient screening techniques. The respondents also identified other findings such as travel history, sore throat, vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain as a positive response in their current patient screening techniques. More recent studies have shown that the loss of taste (ageusia) or taste alteration (dysgeusia/amblygeustia) is common in COVID-1916. Indeed, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention17 include ageusia and dysgeusia as an early symptom of COVID-19. The salivary gland and tongue are potential targets for SARS-CoV-2 because of the expression of AC218 , 19, but AC2 is also expressed in the gastrointestinal tract19, and individuals may present with diarrhea20.

Despite different screening techniques, 80% of positive patients have only mild symptoms that resemble flu-like symptoms and seasonal allergies. This might lead to an increased number of undiagnosed cases21. Of concern, these asymptomatic patients can act as “carriers” and also serve as a reservoir for re-emergence of the infection11.

Because of the high likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the dental care setting, PPE is discussed in almost every COVID-19 survey-based research regarding dentists during COVID-19 pandemic. Here most of the endodontists described taking special measures beyond regular PPE. The use of the N95 respirator face mask was reported by 83.1% of the participants. The percentage of practitioners who enhanced PPE utilization with the use of N95 respirator face mask varies across the surveys, ranging from 12%–90%11 , 22 , 23. The lack of adherence to the N95 respirator face mask may not only be explained as a lack of willingness to implement adequate procedures but also by the shortage of PPE announced in March 2020 by the WHO24. Some respondents also reported the use of other additional COVID-19 protection such as the face shield, head cover protective suit, as well as plexiglass aerosol shield for microscope and others.

According to our results, as of July 2020, most endodontists took part in endodontic care in the front-line treatment of dental patients (322/397, 82%). Most of the participants acknowledged trauma (326/397, 82.1%) followed by swelling (325/397, 81.9%), pain (302/397, 76.1%), and postoperative complication (237/397, 59.7%) to be emergencies. Thirty-five percent of the participants (139/397, 35%) reported all of the above emergencies. To help endodontists to assess a true emergency, Ather et al16 provided a questionnaire for the assessment of true emergency. In addition, the authors put together a set of recommendations for the management of dental emergencies.

The majority of the respondents agreed at some level that the rubber dam is sufficient/efficient to reduce COVID-19 cross infection from routine endodontic procedures. For instance, the rubber dam isolation can reduce airborne particles by up to 70% within a 3-foot diameter of the operational field25 , 26. The American Dental Association27 recommends rubber dam isolation not only for endodontics procedures but for almost all aerosol-generating dental procedures. Because the virus load in human saliva is relatively high, preprocedural mouth rinses, despite their limited activity against SARS-CoV-2, the use of high volume saliva ejectors and oral aerosol vacuum, as well as air purifying unit, are recommended to reduce the hazard. Our survey indicated that 42.3% of the endodontists implemented an air purifying unit, and 16.9% added oral aerosol vacuum in their practice beyond regular PPE and rubber dam isolation.

One of the limitations of this study is the number of respondents who participated in the survey. The small sample size may produce a clustering effect. Although participants were assured of their anonymity, concerns about being identified may have affected their answers28.

Overall, most endodontists are aware of the COVID-19 pandemic and are concerned about contracting and spreading the virus. Despite the conflict between their roles as health care providers and family members with the potential risk of exposing their families, most of them remain on duty providing front-line care for dental treatments. In addition, this survey demonstrates endodontists’ knowledge and awareness of the need for patient screening measures for COVID-19 and special measures beyond regular PPE equipment. It is important to point out that COVID-19 conditions can change rapidly, and endodontists must comply with the guidelines released by the WHO and dental associations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Liesa Berg for technical support.

The authors deny any conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang D. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Word Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) weekly epidemiological update and weekly operational update. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Available at:

- 3.COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html Available at:

- 4.Chau C.H., Strope J.D., Figg W.D. COVID-19 clinical diagnostics and testing technology. Pharmacotherapy. 2020 doi: 10.1002/phar.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019 ncov/hcp/faq.html#Transmission Available at:

- 6.England NHS. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/issue-3 preparedness-letter-for-primary-dental-care-25-march-2020.pdf Available at: Accessed August 21, 2020.

- 7.American Dental Association ADA interim guidance for management of emergency and urgent dental care. https://www.coronavirus.kdheks.gov/DocumentCenter/View/853/ADA-Interim-Guidance-for-Management-of-Emergency-and-Urgent-Dental-Care-PDF---4-15-20 Available at:

- 8.British Dental Association Coronavirus: your FAQs. https://bda.org/advice/Coronavirus/Pages/faqs.aspx Available at: Accessed August 21, 2020.

- 9.Duruk G., Gümüşboğa Z.Ş., Çolak C. Investigation of Turkish dentists’ clinical attitudes and behaviors towards the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:14703. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tysiąc-Miśta M., Dziedzic A. The attitudes and professional approaches of dental practitioners during the COVID-19 outbreak in Poland: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4703. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ather A., Patel B., Ruparel N.B. Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19): implications for clinical dental care. J Endod. 2020;46:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000045. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfefferle S., Reucher S., Nörz D., Lütgehetmann M. Evaluation of a quantitative RT-PCR assay for the detection of the emerging coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 using a high throughput system. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000152. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Z., Li X., Sun H. Rapid identification of COVID-19 severity in CT scans through classification of deep features. Biomed Eng Online. 2020;19:63. doi: 10.1186/s12938-020-00807-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamal M., Shah M., Almarzooqi S.H. Overview of transnational recommendations for COVID-19 transmission control in dental care settings. Oral Dis. 2020:10. doi: 10.1111/odi.13431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen L., Zhao J., Peng J. Detection of 2019-nCoV in saliva and characterization of oral symptoms in COVID-19 patients. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3557140 Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.American Dental Association ADA interim guidance for management of emergency and urgent dental care. https://www.ada.org/∼/media/CPS/Files/COVID/ADA_Int_Guida nce_Mgmt_Emerg-Urg_Dental_COVID19.pdf Available at:

- 18.Cano I.P., Dionisio T.J., Cestari T.M. Losartan and isoproterenol promote alterations in the local renin-angiotensin system of rat salivary glands. PLoS One. 2019;14:0217030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M.L. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus: a first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu T.U. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed M.A., Jouhar R., Ahmed N. Fear and practice modifications among dentists to combat novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2821. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cagetti M.G., Cairoli J.L., Senna A., Campus G. COVID-19 outbreak in North Italy: an overview on dentistry—a questionnaire survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3835. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment- endangering-health-workers-worldwide Available at:

- 25.Peng X., Xu X., Li Y. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:9. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samaranayake L.P., Reid J., Evans D. The efficacy of rubber dam isolation in reducing atmospheric bacterial contamination. ASDC J Dent Child. 1989;56:442–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Dental Association ADA adds frequently asked questions from dentists to coronavirus resources. 2020. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/march/ada-adds- frequently-asked-questions-from-dentists-to-coronavirus-resources Available at:

- 28.Yu J., Hua F., Shen Y. Resumption of endodontic practices in COVID-19 hardest-hit area of China: a Web-based survey. J Endod. 2020;46:1577–1583.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]