In January, 1892, the English social reformer and women's rights campaigner Josephine Butler wrote to her son, Stanley, to complain of fatigue and a general declension of the spirits. Butler attributed her symptoms to an attack of “Russian influenza” the previous Christmas, which had left her with painful conjunctivitis and inflamed lungs. “I don't think I ever remember being so weak, not even after the malaria fever at Genoa”, she confessed. 3 months later there was little improvement. “I am so weak that if I read or write for half an hour I become so tired and faint that I have to lie down,” Butler informed a friend.

Butler was one of the most prominent female sufferers to document the lingering after-effects of influenza following the pandemic of 1889–92—colloquially called the Russian influenza because the epidemic had broken out in St Petersburg in November, 1889. However, the best known and most widely reported influenza invalids in the UK were male and included the then British Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary Lord Salisbury, his nephew Alfred Balfour, the Secretary of State for Ireland, and Lord George Hamilton, the First Lord of the Admiralty. In February, 1895, the Liberal Party leader and Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery, also had Russian influenza and was confined to his home in Epsom, Surrey, for 6 weeks, with fatigue and insomnia, prompting intense commentary in Victorian newspapers and periodicals.

As with COVID-19, the diversity of these post-influenza symptoms and their unpredictability baffled contemporary medical observers and provoked lengthy disquisitions in The Lancet and other medical journals. The neurological conditions observed after the Russian influenza were given many names: neuralgia, neurasthenia, neuritis, nerve exhaustion, “grippe catalepsy”, “post-grippal numbness”, psychoses, “prostration”, “inertia”, anxiety, and paranoia. The Victorian throat specialist Sir Morell Mackenzie described how influenza appeared to “run up and down the nervous keyboard stirring up disorder and pain in different parts of the body with what almost seems malicious caprice”. The German-born Harley Street neurologist Julius Althaus concurred, stating that “there are few disorders or diseases of the nervous system which are not liable to occur as consequences of grip”.

The result was that by the middle 1890s Russian influenza was being blamed in England for everything from the suicide rate to the general sense of malaise that marked the fin de siècle, and the image of a nation of convalescents, too debilitated to work or return to daily routines, and plagued with mysterious and erratic symptoms and chronic illnesses, had become central to the period's medical and cultural iconography. Although H Franklin Parsons, the medical investigator for England's Local Government Board, completed his final report on the “1889–92 epidemic” in 1893, further severe recrudescences were observed in 1893, 1895, 1898, and 1899–1900. The official end of the pandemic, therefore, did not mean the end of illness but was merely the prelude to a longue durée of baffling sequelae.

Some 10 months into the pandemic sparked by the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, COVID-19 is revealing itself to be similarly protean, comprehensive, and persistent, and a new category of patients is emerging, colloquially known as COVID-19 “long-haulers”. These patients typically did not need critical care but on social media platforms and in interviews with journalists report “rolling waves of symptoms”, including fatigue, hallucinations, “brain fog”, delirium, memory loss, tachycardia, numbness and tingling, and shortness of breath. Some have joined social media survivor support groups and set up patient-led research forums. Others have shared their experiences on Twitter, where, in #LongCovid threads that resemble the epistolary dialogues of earlier influenza sufferers, they discuss their myriad symptoms and help each other navigate uncertainty about recurrence, debility, and dread of a new disease about which so much is still unknown.

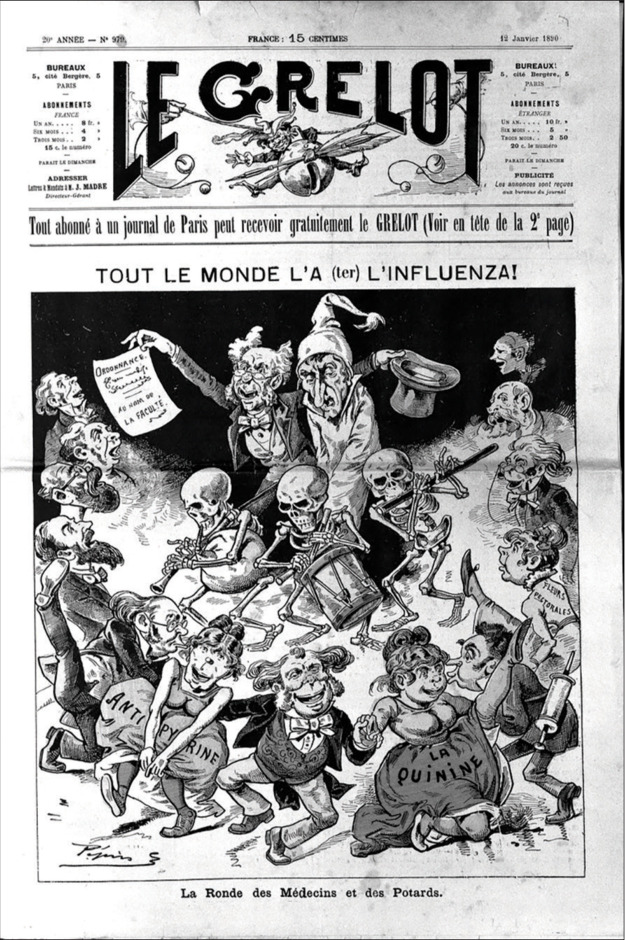

© 2020 Wellcome Collection/Attribution 4.0 International/CC BY 4.0/A man with influenza, taken in hand by a doctor, surrounded by dancing politicians. Wood engraving by Pépin (E Guillaumin), 1889

© 2020 damircudic/Getty Images

Medical literature is turning its attention to the long-term effects of COVID-19. One group of doctors in the UK, who have persisting symptoms of suspected or confirmed COVID-19, have called for research incorporating patients' perspectives to capture the “full spectrum” of this disease. Another group of long-haulers warn against comparing the symptoms observed after COVID-19 with those of other conditions or of treating the symptoms exclusively as a post-viral syndrome.

Unfortunately, many COVID-19 long-haulers report having their experience of physiological suffering disbelieved or dismissed by medical practitioners. Such responses are potentially demoralising and might also impact racial and ethnic minorities, people living with disabilities, and other vulnerable groups, potentially worsening health disparities that became evident in some countries during the first months of the pandemic. As the world surpassed 1 million deaths from COVID-19, it is becoming increasingly clear that the coronavirus interacts with other social and biological phenomena—eg, non-communicable diseases, health resource strain, socioeconomic disparities, unequal housing, racism—a clustering known as a syndemic.

These medical attitudes can perhaps partly be traced to the initial phase of the pandemic when a priority was to identify acute cases at risk of severe respiratory and multiorgan failure. By contrast, non-urgent cases were generally designated mild to moderate. However, as mitigation strategies have provided some respite for critical care physicians ahead of a resurgence in infections, it appears that COVID-19 is a disease with a bewildering array of complications. Moreover, the designation of mild disease in some patients risks conflating self-resolving illnesses of short duration with persistent and, according to some long-hauler accounts, emotionally and psychologically debilitating morbid responses.

These accounts remind us of the limitations of narrow biomedical models and the importance of listening to patients' narratives of illness, which are shaped by pre-existing diagnostic categories, a patient's particular social setting, and the wider cultural context. According to Arthur Kleinman, Rita Charon, and other scholars, the task of the sympathetic physician is to contextualise these narratives within a broader web of biopsychosocial meanings. This can be particularly important in the case of chronic illnesses where patients may struggle to obtain adequate support, thus exacerbating the sense of a rift between the self and others.

In this respect, elements of the response to COVID-19 long-haulers contrast with the sympathy shown for Russian influenza convalescents during the 1890s and the engagement of a wide range of medical professionals with the influenza's nervous sequelae. This engagement can be partly explained by the fact that in the 1890s demarcations between the medical specialties, and family and hospital practice, were less rigid than they are today and an ear, nose, and throat physician could pronounce on nervous complaints which would now more properly be considered the province of neuropsychiatrists and other experts. Furthermore, in the late Victorian period ideas of infectious disease causation were in a state of flux and laboratory medicine had yet to supplant older environmental and epidemiological understandings of disease and the close observation of patients' symptoms, particularly in the UK where physicians and medical researchers were suspicious of the “new” German bacteriological methods. A doctor's surgery was regarded as an important site for making and exploring new diagnostic categories and the physician–patient encounter was charged with the possibility of discovery. Little wonder then that the study of the psychoses of influenza came to be seen as a route to professional advancement and patient narratives and case histories became a popular subject for correspondents to medical journals and the emerging genre of the medical disease detective.

An association between influenza and CNS complications is established, even if the pathophysiology, the role of the host immunological response, and psychological stressors are not fully understood. For instance, the 1918–19 influenza pandemic was associated with parkinsonism, catatonia, and “encephalitis lethargica”, the so-called sleeping sickness that was reported in Europe in 1917 and persisted in Europe and North America until 1929. However, while the so-called Spanish influenza of 1918–19 is frequently invoked as an analogue for COVID-19, the Russian influenza might be a better cultural parallel.

The Russian influenza was the first influenza pandemic for 42 years. While veteran physicians recalled the diverse forms the disease had taken in 1847–48, in 1889 a standard classification was that found in Quain's Dictionary of Medicine, which emphasised the pulmonary and gastric forms of the disease. Influenza's nervous symptoms therefore came as a surprise to many practising physicians and discussion of typical cases soon became a hot topic, and not only in medical journals. “Influenza is the very Proteus of diseases, a malady which assumes so many different forms that it seems to be not one, but all diseases epitome”, Mackenzie informed readers of the Fortnightly Review during the second wave of the pandemic in 1891.

The Lancet's letter columns were full of correspondence from doctors in hospital and private practice attesting to unusual features of the disease. As in the first phase of COVID-19, men seemed more likely than women to suffer acute attacks of influenza and present at hospitals and doctors' surgeries—men were also reported to be more likely to suffer fatal outcomes. This might explain physicians' willingness to compare influenza to neurasthenia and, rather than characterise male patients' responses as a type of hysteria—a diagnosis generally reserved for women and which risked being gendered “feminine”—argue that the nervous sequelae were somatopsychic and the result of a primary focal infection. By 1892 influenza nervosa had been classified as a type of fatigue neurosis that, like neurasthenia, could be traced to overwork and hypervigilance, key tropes of masculinity and modernity.

In the 1890s, a marked feature of the psychoses of influenza was a profound sense of dread accompanied by feelings of alienation, both from oneself and from others. Disembodiment or the mutiny of one's own facilities was a common description: “My powers of endurance” have been shaken by “a recent attack of influenza and its consequences”, wrote Speaker Peel to Henry Lucy in 1894. Not being able to trust one's mind or memories was another: influenza has left an “extraordinary sequel behind”, reported Dr Arthur Feveral in L T Meade and Clifford Halifax's short story The Doctor's Dilemma, published in The Strand Magazine in 1895. In it, Feveral believes he may have poisoned a patient by mistake after an attack of influenza. Halifax was a pseudonym for the Harley Street physician Edgar Beaumont, and the story makes clear how seriously Victorian physicians regarded the Russian influenza and the psychosocial and economic consequences of its nervous sequelae. In his confusion, Feveral believes he has made a grave medical error. The influenza, we are told, has wrecked Feveral's memory and “the fear of it has made [him] thoroughly nervous and unfit for work”. In this way, the story makes explicit the supposed connection between overwork and mental debility at the heart of the influenza nervosa diagnosis and the social and economic pressures to which doctors and other bourgeois professionals were presumed to be subject, especially during the first months of the Russian influenza pandemic.

Will the COVID-19 pandemic elicit similar sympathy for COVID-19 long-haulers, three-quarters of whom, according to one patient survey, identify as female, an apparent reversal of the pattern seen in 1889–92 and prompting questions about whether women might be more likely than men to suffer long-term symptoms? Will doctors and medical researchers show the same enthusiasm for treating these patients and taking their symptoms seriously?

There are already some heartening signs. Post-COVID-19 rehabilitation and outpatient care is being rolled out in countries including India, Italy, and the USA. WHO has been pooling data about the long-term effects of COVID-19 and sharing advice on rehabilitation. In August, 2020, the UK's Department of Health and Social Care awarded a £2 million grant for a COVID-19 Symptom Study tracking app. To date initial findings from the Covid Symptom Study suggest that about 10% of those self-reporting symptoms to the tracker have had symptoms for 30 days and 1·5–2% for 90 days; patterns in the study also suggest that long COVID was about twice as common in women as in men. However, it is impossible to rule out sampling bias, hence the importance of rigorous studies measuring the long-term health impacts of this new disease. This is one of the aims of the Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 study (PHOSP-COVID) study in the UK, which is recruiting patients who were admitted to hospital with confirmed or suspected COVID-19.

Such refocusing is crucial now that the early, mysterious days of the pandemic are behind us and as it becomes clear that COVID-19, in one form or another, is here to stay. As they adjust to the pandemic's longue durée, physicians might find it helpful to look back to the Russian influenza and the historical accounts of the sequelae, even as COVID-19 long-haulers look to digital, patient-centred, and activist forums for support and validation in the present. Although such self-generated experiential accounts and communities do not offer certainty, they provide a narrative frame of reference and, as Sharrona Pearl writes, allow “individuals to emerge from behind the panic and spectacle of a plague”. For pandemics, like the illnesses they generate, linger not only in our bodies but also in our minds, culture, and communities. What we choose to make of this lingering, and how we interpret the pandemic's sequelae, will be the true measure of our care.

Further reading

- Alwan NA, Attree E, Blair JM. From doctors as patients: a manifesto for tackling persisting symptoms of COVID-19. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286:1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowse TS. Baillière, Tindall and Cox; London: 1894. On brain and nerve exhaustion (neurasthenia) and on the nervous sequelae of influenza. [Google Scholar]

- Honigsbaum M. Bloomsbury; London: 2020. A history of the great influenza pandemics, 1830–1920. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Basic Books; New York: 1988. The illness narratives: suffering, healing and the human condition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan L, Ogunwole SM, Cooper LA. Historical insights on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the 1918 influenza pandemic, and racial disparities: illuminating a path forward. Ann Intern Med. 2020;6:474–481. doi: 10.7326/M20-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade LT, Halifax C. Stories from the diary of a doctor. The Strand Magazine : An Illustrated Monthly. 1895;10:80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons HF. HM Stationery Office; London: 1891. Report on the influenza epidemic of 1889–90. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons HF. HM Stationery Office; London: 1893. Influenza epidemic. Further reports and papers on epidemic influenza, 1889–92. [Google Scholar]

- Patient-Led Research for COVID-19 What does COVID-19 recovery actually look like? 2020. https://patientresearchcovid19.com/research/report-1/

- Perego E, Callard F, Stras L. Why the patient-made term “Long Covid” is needed. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:244. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl S. Symptom check. Real Life. July 2, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Sleat D, Wain R, Miller B. Tony Blair Institute for Global Change; London: 2020. Long Covid: reviewing the science and assessing the risk. [Google Scholar]

- Yong E. Long-haulers are redefining COVID-19. The Atlantic. Aug 19, 2020 [Google Scholar]