Abstract

The paper describes how leaders behave and react in unprecedented times when a professional service firm has been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Firsthand data were gathered through interviews, observations, and participation based on direct interaction with leaders and employees. The concept of leadership anatomy is used to describe, discuss, and critique leadership behavior. It signifies the different parts of a human body equipped with sensory ability. The study reveals that in times of crisis, leaders tend to draw on the core of who they are through compassion rather than conventional wisdom in decision making and problem solving. The search for what truly matters helps leaders to reinterpret the ethos of the firm and what they stand for as leaders in their sensemaking of chaos. A deeper reflection of their personal values and beliefs gives them the courage to acknowledge their vulnerability and start seeing the value in others.

Keywords: Leadership anatomy, Adaptive leadership, Change, Resilience, Turbulence, Wicked problems

A time like never before

Joe receives an urgent phone call from a major client complaining of an ongoing project that has been unexpectedly delayed due to a sudden shortage of product supplies. He is suddenly dumbfounded without a solution as the project is one that involves multiple stakeholders, including employees and experts from across the firm as well as external vendors. Not only is the project time-sensitive but it is also multi-sited involving stakeholders from geographically-dispersed locations around the world. Time differences and complex task structures have made it excruciating for Joe to contact every key person in quick time. This is the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic where supply chains have been extensively disrupted due to international border closures.

The above scenario offers a glimpse of what a distressed organization could look like in times of crisis. Task structures have become transient as employees have been redeployed to focus on different aspects of operational contingencies. With emerging governmental regulations imposing on companies in the fight against COVID-19, leaders are expected to step up to the call of (heroic) duty in unprecedented times. The suspension of major business activities has caused massive disruptions to day-to-day operations. Employees have begun telecommuting and leaders are suddenly confounded by a wicked problem – a global health crisis for which there is no proven vaccine! Leaders must therefore learn to be agile and adaptive to rapid change. Conventional wisdom of leadership may not be the panacea for addressing complex issues in circumstances of turbulence. Accordingly, this paper explores leadership at the core, where knowing who you are and what you stand for is pivotal to leading your organization out of chaos. Not compromising on the deep values to which you hold true of yourself and your job is paramount. The paper (re)introduces the concept of leadership anatomy to unravel the human and practical aspect of leadership in times of uncertainty. While the concept is not entirely new, it has not been discussed adequately in the context of crises with a focus on the paradoxes and complementariness as well as the strengths and tradeoffs of leadership. The relevance of leadership anatomy in current times is an increased self-awareness of values and beliefs that could be translated into reflexive and purposeful action even if you have to say ‘no’ against the will of others.

The paper is based on empirical data gathered in a multinational firm, known only as Capital Co, at a time when the pandemic was at its peak in terms of outbreak and impact on the world economy. At the point of research, the firm was ramping up their contingency plans to minimize business impact, led by an inspirational CEO who was guided by a passion to enable change through positive influence and bold strokes. Capital Co was not adequately prepared for the crisis as their previous emergency response plans did not cater for a pandemic of that magnitude. The ethos of the firm was personified through the CEO, whose word and action illuminate the deeper meaning of the firm’s existence with people being central to the success of their business. The crisis unleashed the inspiration of the CEO to influence his management team to reflect and act on what they truly stand for as leaders. The paper uses leadership anatomy – the vital functions of leadership – as a symbol to draw out the contours of leadership behaviors in Capital Co. 25 supervisors with teams ranging from 10 to 120 employees each were interviewed in addition to 47 interviews with a cross-section of employees. Perceptions about how various leaders handled the crisis and performed during the crisis were explored. Findings led to a clearer illustration of leadership anatomy in response to internal tensions and external disruptions. Being aware of how you think, feel, and act is crucial for leading confidently in turbulent times as you maximize your leadership anatomy to achieve desired results.

Connecting to the core of who you are

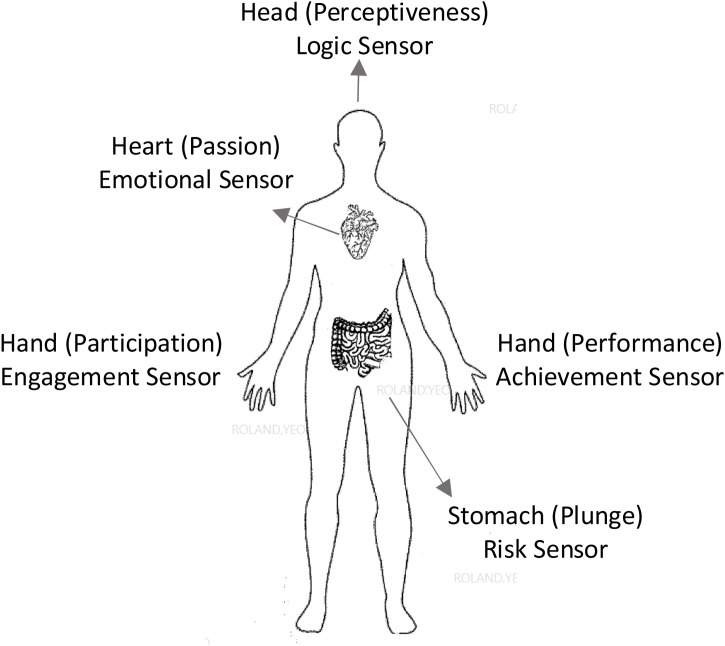

Imagine leadership is the human anatomy where the body parts could be used to characterize leadership comprising the head, heart, hand, and stomach (Figure 1 ). As a leader, harnessing the best of you to navigate through ambiguity and complexity would require that you delve deeper into the core of who you are rather than what you are. Think of your body parts as having the sensory power to connect your inner self to the external world. The various sensors trigger not only your cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to your environment, but also your gut response which leads to courage. For instance, your head is the logic sensor with the power to perceive connections and sequences, while the heart is your emotional sensor with the power to feel and empathize. Your hands function as the engagement and achievement sensors where you participate and perform to drive results. More importantly, your stomach functions as your risk sensor, giving you the power to leap out of or retract from rough situations, much like the fire in the belly.

Figure 1.

Leadership Anatomy

Head: the logic sensor

Anatomically, the head resides above the rest of the body providing the vision for action. The vision is controlled by the mind or logic sensor, also the human cognition with the power to perform reasoning, abstraction, and analysis. This sensor facilitates a leader’s perception and interpretation of his or her surroundings by making sense of language and action patterns, connecting them to the rationale for certain decisions. Seeing through the eyes of the mind enables a leader to frame the social world with boundaries that characterize his or her long-range thinking. The leader seeks alternatives, reconsiders existing resources and processes, and develops distinct perspectives of what is happening around him or her. Activation of the logic sensor could also stretch a leader’s strategic foray to explore competitive forces and opportunities for growth and continuity while not losing sight of potential pitfalls and risks. The mind pushes boundaries and challenges assumptions through sharp questioning and reflection to identify possibilities for change. However, the mind could also fool the body by scanning for farfetched ideas that are possibly unreachable. Employees tend to gravitate toward leaders who possess a sharp mind in order to make swift but considered decisions with a wider impact on the organization. When the logic sensor is used in extreme, it could lead to inflexibility affecting decisions and actions that may contradict individual values and beliefs. Such inflexibility could reach a tunnel vision when a leader disregards the suggestions of others to achieve something at all cost. Leading at the core calls for a desire to challenge the logos (mind) in relation to other anatomical sensors in order to communicate with the rest of the body.

Heart: the emotional sensor

The heart not only pumps blood but also gives life to the entire being as the nerve point of the body. Blood signifies emotion, passion, and élan streaming out into relationships and connections searching into the depth of one’s soul. The heart is therefore the software of the body and functions as the emotional sensor that helps leaders develop true compassion for others and their business. Leaders who follow their hearts in decision making and social interaction connect with their employees at a deeper level. They are perceived as demonstrating fundamental human judgment without compromising on personal and organizational values. However, some leaders could be quite oblivious to their emotional sensor. Rather than using their emotional awareness and engagement to their advantage, they could potentially behave contrary to how they feel toward others. They also tend to overreact to crises and mask their emotions by focusing narrowly on mitigating existing challenges. In doing so, they inadvertently create pressure on others to meet their unrealistic expectations. They might fall into the trap of treating their employees as nuts and bolts rather than humans with intellectual capacity and emotion. This happens when their emotional sensor is dimmed by their preoccupation to deliver immediate outcomes over which they might have no complete control. At times, internal and external pressure would require leaders to make quick and tough decisions. Doing so without compassion and consideration of others could make their employees feel shortchanged and neglected. Leaders should also listen to their hearts when making decisions.

Hands: the engagement and achievement sensors

The hands are by far the most visible kinesthetic components of the body which provide motion and movement, adding a different dimension to human life. Unlike logic and emotion which are internal to the body, the hands are external constituents that get things going. They not only define the aesthetic appeal of the body but also create the anatomical and social dynamics that characterize the agility of the physical body and entire being. The hands can be enabled or constrained by logic and emotion, leading to actions that have internal and external implications. Hands are generally associated with executing and performing, providing sensory connections to engagement and achievement. Leaders who focus on their hands in managing people and tasks are perceived as driving for efficiency by setting high standards for their teams. Their hands-on approach tends to drive participation by involving others in getting things done to achieve set goals. Leaders who lead through their hands could produce positive relational outcomes. They offer their employees the tools, resources, and even handholding to accomplish their tasks successfully. They walk the talk and can be depended upon for direction and encouragement, giving rise to commitment and camaraderie. However, leaders could also be too hands-on to the extent that they become overly involved and sometimes forget to lead. They tend to lose sight of the big picture which affects their capacity to help others navigate through ambiguity. Such leaders drive for output but miss out on process and pay insufficient attention to the task at hand.

Stomach: the risk sensor

Leadership and the stomach have some commonality. A leader’s capacity to handle turbulence and ambiguity requires him or her to possess the courage to unlearn conventional wisdom and relearn the strategy in decision making and risk taking. The stomach functions like a risk sensor signaling what lies ahead and guides a leader to take the plunge when needed. In other words, the visceral aspect of the core self determines the texture (or courage) of a leader expressed in both word and deed. Leaders who follow their gutsy instinct often take the leap and prove something worthwhile through their acts. It is not about heroic acts but acts of integrity to do the right thing despite impending oppositions. These leaders often emerge with true courage in times of crisis through their ability to stomach immense tension, heartache, and stress to pursue what truly matters rather than what is expected of them by the organization. However, leaders who are too gutsy run the risk of making hasty decisions without consulting their logic, which could lead to regrets. Some leaders stretch their guts too excessively and make untimely decisions causing more harm to the organization than what was intended. Guts without conviction could just be empty hot air, but guts with conviction can give rise to courage for the right course of actions. Belief and perseverance with balanced sensibility can lead to courage and conviction in the face of adversity.

Anatomical synergy: the head-heart-hands-stomach harmony

Achieving anatomical synergy in leadership is about balancing between being and becoming. Being is the innate part of you that either delights in or retreats from challenges. It is the holistic part of you that signifies your character, what you stand for, and how you respond to others. In contrast, becoming is the realization of your inner power to transform and renew yourself through constant craftsmanship as a leader. For instance, the head-hand leaders will learn to listen more to their hearts when they start valuing relationships and empowering their teams over achieving politicized power and authority. The heart-stomach leaders will learn to listen more to their heads when they can see the bigger picture beyond their roles by aligning purpose to strategy. However, maintaining balance between being and becoming is a challenge. Extreme utilization of any anatomical functions could cause disharmony and incoherence leading to deviating leadership behaviors, as illustrated in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Leadership Behaviors and Implications

| Anatomy | Behavior | Used Optimally | Used in Extreme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Logic sensor: Analytical, deductive, inquisitive, reflective, investigative, explorative | Lead by strategic thinking, evaluate options, maximize resources, explore alternatives, test assumptions, forecast challenges, analyze data | Blinded by unreachable goals, inflexible decisions, contradict personal values and beliefs at times, overemphasize outcomes and results, develop tunnel vision |

| Heart | Emotional sensor: Compassionate, considerate, passionate, connected, spontaneous | Lead by encouragement, drive motivation, listen to the deeper voice of others, show care and concern, promote genuine feedback, follow their instincts | Downplay outcomes or results, overemphasis on people than process, over-influence others’ interest and decision, overreact to circumstances |

| Hands | Engagement and achievement sensors: Participative, interactive, goal and result- orientated, efficient, productive | Lead by example, walk the talk, adopt a hands-on approach, experiment and improvise, seek collaboration, drive creativity and innovation, engage in change, develop solutions | Too task-focused and forget to lead, lose sight of big picture, drive for output but miss out on process, put pressure on others to perform, too busy to delegate, neglect supervision |

| Stomach | Risk sensor: Courageous, resilient, adaptive, tolerant, heroic, proactive, valiant, adventurous | Lead by conviction, unlearn conventional wisdom of leadership, able to handle ambiguity, act on what’s right, take the plunge, turn word in real action, go the extra mile | Make hasty decisions, act on impulsion, missed out on unexpected consequences, unaware of wider impact on people and organization, act with misguided conviction |

Leading at the core is searching deeply into your inner voice and awakening that which will make a difference to what you say and do. It is about preserving your identity as who you are while doing your best for others and the organization. It is not about letting your head fool you into getting what you want at all cost while losing your personal values and beliefs. It is about balancing passion with sensibility to navigate through power and politics to bring about enduring change through integrity and fairness. Leaders who care are those whose voice is genuine with the courage to demonstrate vulnerability. In turn, they win others over through respect and trust rather than power and authority.

Think of yourself as a symphony conductor who uses his or her hands (engagement and achievement) to motion the interpretations and control of pacing and musical rhythm with the help of a baton (tool). All the time the conductor connects logic (perceptiveness) and emotion (passion) with the musicians to execute and direct the tunes of the ensemble. Depending on the conditions under which the performance unfolds, the conductor might take the plunge (courage) to adapt different musical styles at critical junctures by redirecting the attention of the musicians to unexpected crescendos that heighten the overall performance. Such conditions are contingent upon the space, time, sound, lighting, coordination of the musicians, and response from the audience. In other words, the conductor achieves anatomical synergy in leadership by not just attuning to the environment but more importantly immersing in the dynamics that bring about harmony to his or her musical coordination and stylization. The tunes may be produced by the musicians, but the musical impact is sensationally facilitated through the conductor. Both the musicians and conductor perform on the same stage for a common purpose albeit different roles. The applause is not only their reward but a lasting satisfaction and fulfillment only such synergistic coordination and integration could achieve.

Wicked problems: the bad, ugly, and (possibly) good

Wicked problems surface as disguised organizational symptoms which could quickly progress into more serious operational consequences. These are problems within problems embedded in multiple layers of deeper issues which can only be unraveled through persistent confrontation. Response to wicked problems does not necessarily call for heroic acts but an adaptive mindset supported by a deep conviction for change. Being adaptive is to respond spontaneously and courageously to the problem, allowing the complexity to offer possible inspirations for experimentation. COVID-19 is an example of a wicked problem which is intractable without a clear known cause and spreads rapidly.

A case in point is Capital Co. Leaders were put to the test where their past experience could not provide the headway for managing the complexity of the problem. The change precipitated by the pandemic led to the development of character beyond what is typically outlined in a business contingency plan. Instead, it developed deeper trust and compassion amongst leaders and employees to ensure business continuity, where the human dimension of leadership was tested at different levels during the pandemic. The leaders were expected to act on their courage to bring about clarity and stability amidst ongoing disruption and confusion. Applying the consciousness of leadership anatomy became of importance to all change agents at that time.

The rate of change at Capital Co was contingent upon internal and external factors. Internally, the firm critically examined their existing contingencies not adequately planned for a pandemic. Externally, lockdowns and international border closures forced the firm to look inward for their own means of survival through existing resources. People are their key asset and they spared no effort in repatriating as many employees as possible, particularly those who were stranded overseas due to business or personal travels. The leaders had to exercise human compassion rather than logic to make sense of the uncertainty. Employee safety and wellbeing was at the heart of their contingency efforts, leading to swift decisions in suspending immediate training and business activities involving large groups. The efforts were massive as the firm had to contact hundreds of their overseas employees to ensure that they were not only physically safe but also provided with the necessary medical and logistical support.

The leaders were challenged to make tough and timely decisions about the safety of their employees sometimes even at the expense of their business priorities. They took the plunge to do what was right for the firm, demonstrating courage to determine what truly matters to the firm. Despite their best efforts, unpredictable obstacles surfaced. Repatriation flights could not be executed as scheduled due to much tighter travel restrictions causing undue delays. Employees and their families became anxious of their impending safety, which inadvertently resulted in another layer of complexity and frustration. Decisions were no longer made internally but collaboratively with their international partners, governmental authorities, overseas agencies, and even the wider community with employees’ families closely involved.

Escalation of the problems became overwhelming to the extent that the firm was confronted with unexpected issues affecting business continuity at the height of a nation-wide lockdown. A large majority of employees were asked to work from home with many of them without proper technological support. The CEO’s financial accountability to the board of directors and shareholders added undue psychological distress. The need to consider an aggressive strategy to mitigate potential financial losses became imminent in addition to other human-related issues. The challenge for the leaders to juggle between logic, compassion, and courage in critical situations was further exacerbated by an emerging health threat with employees running the risk of being COVID-19 infected. As the number of quarantine cases increased by the days, Capital Co had to ensure that affected employees were receiving timely and proper medical attention.

Fears intensified as the virus outbreak in the community loomed larger and posed a further threat to employees’ health and wellbeing. At that juncture, the leaders were challenged to balance compassion with courage by acting on what was right versus what was easy. They had to make tough decisions considering the wider impact on what they deemed as most essential to the firm – that is, people’s lives. This led to their falling back on compassion with their hearts superseding logic. Anything risking their employees’ lives was given top priority. This led to the firm developing a rigorous contact-tracing system to ensure that employees who were in contact with any infected persons be immediately quarantined with proper medical support. In the same manner, the leaders raised their level of responsiveness on employees experiencing psychological trauma as a result of heightened precautionary measures. In the course of the outbreak, they exercised spontaneous courage and resilience coupled with deep compassion in their protection of employees against any potential exposure to the virus.

Developing leadership resilience

Can wicked problems bring out the best in leaders? Response to wicked problems often puts the leadership anatomy to the test, grinding leaders’ stomach, punching their heart, jolting their brain, and desensitizing their hands. The study of Capital Co reveals five specific resilience enablers that leaders could apply to confront wicked problems such as the pandemic. The findings further reveal observable inconsistencies in leadership performance resulting from variations in internal response to external pressure, as summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Insights on Leadership Performance

| Resilience Enablers | Building Blocks | Stumbling Blocks |

|---|---|---|

| Experimenting with resources | Courage with passion makes a difference to approaching and turning complexity around with unexpected outcomes. | Underestimation of the disruption of tools such as technology derails progress and dampens morale. |

| Asking bold questions | Articulating unspoken resilience opens up opportunities for change and action. Challenging status quo pushes boundaries of risk taking for liberated action. |

A narrow focus on solutions constricts awareness of potential shortfalls they bring. Boundary pushing without a solid grasp of the context leads to confusion. |

| Integrating strategic thinking | Looking externally for inspiration rather than internally for solutions offers insights into the problem at hand. | Being too farsighted leads to a loss of focus on the issues at hand, leading to excessive planning with any clear action. |

| Navigating teams out of chaos | Inspirational belief in people reinforces the value in leadership and helps keep them grounded. Strategic communication through shared vision and beliefs brings clarity and courage in decision making. |

Oversight in people’s readiness for change exacerbates their uncertainty of the future. Pursuing tasks without conviction or a deeper purpose leads to emotional disconnection with others. |

| Immersing in the problem | Acceptance of uncertainty brings psychological and emotional safety and stability. | Being overly comfortable with doubt results in complacency and delayed action. |

Experimenting with existing data and resources

In turbulent times, leaders need to think like bricoleurs by using existing data and resources to work things out. Bricoleurs are those who embrace a do-it-yourself attitude (mind) through improvisation and experimentation (hands). The emergent creation of possibilities requires leaders to follow their hunches (stomach), take the leap, and connect with what truly matters (heart) during pressing times. In Capital Co, the leaders were confronted by the chaotic bricolage of precautionary actions as they searched deeply into the core values of their business reminding them of what the firm truly stands for. Their human capital would always be central to the firm’s interest in protecting.

With critical programs and services suspended, not only did the leaders deploy their existing technological capabilities to alter the way business was conducted, but they also offered alternative delivery options. They had to quickly determine if their clients were prepared for different modalities of training and consultancy delivery. A critical step was to examine their existing resources by redeploying some of their employees, whose jobs were vastly affected by the service suspension, to re-channel their expertise into ready resources in support of more urgent delivery needs. In this instance, the leaders demonstrated uncommon courage through a genuine belief in their employees which resulted in a positive emotional force that resulted in collective action. Risk taking underpinned by an appreciation of the true value of people led to bold initiatives that helped the firm push through tough times. Hands driven to develop initiatives ultimately placed employees at the center of their business continuity.

There were also decisions that could not proceed as expected due to aggressive cutbacks from all parties. Rather than deferring decisions, the leaders internalized their clients’ challenges and collaboratively offered solutions that could lead to win-win solutions in the long run. In other words, they turned their sudden halt in business operations into an entrepreneurial opportunity by helping their clients identify new business possibilities. In more specific ways, they helped their clients identify wider learning needs and design innovative solutions to co-create potential business opportunities, such as the development of curricula for digital learning, coaching, and consultation, by challenging status quo and reimagining the new normal. The leaders did not freeze at internal constraints where potential solutions could be limited, but rather looked to external market dynamics for inspiration. Getting out of their comfort zone helped them reconstruct their conception of business prospects for alternative offerings and possibilities.

Telecommuting for over 80% of their workforce also posed an emergent issue. Not all departments were prepared for such a massive arrangement due to the lack of technological infrastructure, capacity, and network coverage to support employees working from home. Rather than ignoring these technological issues, the leaders came together to focus on how they could turn the employees’ network challenges into a source of unified energy. They were convinced that keeping people intact was the way forward. With their hearts set on what the firm stands for, unification between the logic, action, and courage followed. Topmost on their minds was how to reengage their employees in more meaningful ways. They experimented with a communication strategy with all line supervisors, reaching out to every single employee and finding out if they had specific issues working in isolation through regular phone calls. Engaging these employees through intentional connection was a source of inspiration for the leaders than tucking in to brew up new ideas. Active engagement with their employees reinforced relational significance and opened up a reservoir of spontaneous ideas and propositions not previously experienced.

Response from the employees about the calls was overwhelming not surprisingly, as they were appreciative of the firm’s commitment to employee wellbeing. What followed was a swift relocation of desktops, laptops, and iPads through a third-party vendor to these employees’ homes to ensure that they remain network-connected. Such experimentation led to an unexpected emotional reinforcement of people’s dedication to their jobs, which turned the COVID-19 gloom into positive work reengagement. However, frustration quickly set in for some leaders as their underestimation of technical and morale issues brought about by technology was not earlier anticipated. Employees expressed that they were uncomfortable utilizing their personal internet subscription to access the network of the company in support of their work. Technical glitches and weak internet connection due to limited bandwidth in home internet made working from home frustrating, affecting productivity. Had the leaders considered the flipside of technological disruption and disablement, they would have embarked on a more strategic and realistic network deployment plan.

Asking bold questions

Unanswered questions continued to confront Capital Co as a result of bolder questions raised.

No one was certain about what to expect in the new normal with increasing daily infections. Questions surrounding the mitigation of business losses were overshadowed by questions of what’s next for their employees all over the world. Bold questions were largely fueled by the firm’s focus on people, which gave the leaders the appetite (stomach) to take drastic steps in ensuring the safety of their employees (heart – what truly matters). Bold questions such as relocating employees from higher-risk to lower-risk countries as temporary measures to circumvent the strict international travel restrictions attests to their focus (head) on what should be prioritized. Deep questioning led to the leaders extending their search for alternative solutions beyond their boundaries of familiarity (hands). In other words, they constructed bold dialogue with internal and external stakeholders, such as governmental authorities and international agencies, in hopes of seeing some light at the end of the tunnel as far as employee repatriation was concerned. Bold dialogue helped the leaders challenge the boundaries of risk taking that led to swift, considered, and aggressive decision making regarding employee safety.

Driving the right dialogue with bold questions also raised the collective capacity of the leaders’ strategic thinking to another level. Bold questions led to out-of-the-box responses helping internal and external stakeholders break through the chains of doubt and skepticism to collaboratively explore wider solutions for the stranded employees. Through a variety of channels such as extensive contacts and diplomatic ties, the various teams were able to first contact every single overseas employee for immediate support. Hand sanitizers, face masks, and other necessities were subsequently sent to the employees. Further, special arrangements were planned for the firm’s overseas representatives to travel to the most accessible cities to meet up with these employees within the same country. Some employees also volunteered to travel to cities farther away to help newer employees. They developed a tag-team approach to caring for one another in times of anguish. Mobilization of volunteers was largely driven by heart-wrenching stories of individuals who expressed vulnerability and helplessness. It was the compassion (heart) that motivated people to action (hands). Coupled with sound logic (head) through strategic risk taking (stomach), the leaders were able to take the plunge of mobilizing existing resources and ultimately repatriating over 75% of their overseas employees against all odds at that point with more flights being planned.

Despite the success in repatriation, the leaders did not foresee the potential complications of diplomatic and political constraints due to strict border closures. Over-presumption of travel protocols and safety measures did result in unexpected inconveniences for some returning employees. For instance, several flights were rerouted to other unplanned destinations due to unforeseen regulatory restrictions, leaving passengers stranded for hours in some foreign countries. Several other flights were refused landing in designated airports and had to turn back to the point of origin. Such delays and disruptions caused undue frustration and concerns for employees’ families. Those who returned safely had to be confronted by the uncertainty of possibly tested COVID-19 positive as was the case for several returnees, leading to unexpected isolation and hospitalization, and causing more stress and frustration for the infected returnees.

Integrating strategic thinking into day-to-day operations

Bold questions became the modus operandi for most leaders in Capital Co. Although these questions led to bolder actions, the level of strategic thinking could not penetrate entirely to the ground level. The remaining 20% of the employees back in their offices challenged the rationale for why their safety was compromised by being deployed onsite. Potential exposure to the virus created immediate fear and concern amongst them as they could have supported the already scaled-down operations from home. However, the firm’s position was to maintain a core group of forerunners onsite to address any emergent issues, particularly in response to governmental curfews impacting daily operations. With people’s wellbeing as their priority (heart), the leaders addressed these employees’ concerns seriously through strategic thinking (head). Although the forerunners were stationed in geographically-dispersed office buildings, they were connected on a regular basis through video conferencing and daily emails to keep them in the big picture. In doing so, the leaders involved their employees in developing bold questions and big ideas through critique, refinement, and suggestions. Doing so built the employees’ self-worth and propelled them toward finding alternative resolutions. Strategic communication helped onsite employees stay connected and engaged to a considerable extent, but this called for extensive commitment from the leaders.

The leaders also saw the need to consider futures and foresight as a strategic integration to determine the stimulus for greater innovation and experimentation. Suspension of conventional training and consultancy services led the firm to exploring the escalation of digital transformation. Transforming old ways of practice into the future of work led to the conceptualization and introduction of innovative digital learning and service delivery. A number of applications were designed and preliminarily tested, such as virtual learning, assessment, career counseling, and leadership coaching with encouraging feedback from their clients. In some ways, COVID-19 became the stimulus for the firm to re-imagine their competitive edge by capitalizing on their core competencies. Delivering high-quality programs and services through digital capabilities like virtual reality and artificial intelligence without losing personal touch became of reality. There was a sudden awakening of Capital Co’s hidden treasures, not least their foresight in digital technology investment in preparation for a post−COVID world.

The impact of COVID-19 jolted the leaders’ thinking (head), connecting them to the core of what they stand for (heart), turning their fuzzy ideas into concrete applications (hands), and stepping into new forays in their offerings (stomach). It is about bringing practical focus on the future of work in the midst of uncertainty through strategic clarity, alignment, and insight. However, thinking ahead could be far-reaching for some leaders as they began to lose sight of the existing challenges. Rather than managing the tension between then and the future, they engaged in farfetched imagination without considering the readiness of their workforce. The lack of human competencies and capacity to transform conventional training delivery into virtual applications only caused fear and anxiety to some employees, dampening their morale. Further, client preference for human touch through in-person delivery and their lack of confidence in digital offerings posed greater challenges for leaders to manage internal deficiencies and external demands.

Navigating teams out of chaos to pursue agility with a clear purpose

Communicating accurate and timely information was for Capital Co a fundamental responsibility to employees in the midst of confusion. Some leaders came together to develop an extensive response program with a focus on providing psychological and emotional support for employees and dependents affected by COVID-19. These include those tested positive for the virus and those in quarantine for being in contact with suspect or infected cases or exhibiting health symptoms. Regular phone calls and special arrangements based on the employees’ needs were executed. Initial feedback from these employees reinforced the impact of human touch where they felt a sense of solidarity and inclusivity in a time of isolation. The connection of hearts quickly turned into a form of empowerment, creating positive energy as these employees took greater control of their situation and felt a part of the wider community.

As time passed, the response efforts led to undue fatigue as the calls were not entirely motivated by a genuine concern. For some leaders, calling employees became more of an obligation not necessarily supported by a deeper passion. Subsequent feedback suggests that some leaders were led by their heads rather than their hearts with almost-scripted lines like “I am calling you because the firm wanted me to find out how you are coping.” The intent of each call became contestable and some employees felt psychologically distant with responses like “I am doing ok. If I have any problem, I will let you know.” This is a case of leaders completing a task without an impact as they were doing it without any inner conviction. However, leaders who truly care showed more genuine and deeper concern by listening through empathy and compassion. They were also more willing to help by going the extra mile to ensure that their employees’ needs are met.

Shifting attention to what truly matters was crucial for upholding the ethos of Capital Co as their employees were perceived as not merely contributors to firm success but also people of true value with hopes and dreams to be fulfilled. The challenge was to navigate them out of their psychological barriers. However, employees who were trapped in their entrenched mindset and behavior gradually became complacent as business operations decreased in pace. Thoughts like “COVID-19 will soon pass and things will return to normal again,” could be detrimental to the firm’s renewed vision for a different future beyond the pandemic. Program and service suspension also exacerbated the state of complacency as some employees lapsed into inaction by becoming docile and apathetic. Here, some leaders fell into a similar psychological trap; they became unduly shortsighted being less responsive to the far-reaching impact of the pandemic.

Leaders who made a genuine attempt to connect with their employees did make a positive impact. Keeping employees excited about the future and valuing their talent and expertise did serve as a stimulus that motivated them to remain positive and agile. Subsequently, a growing number of employees became more proactive and generated wild ideas to help the firm sustain their business. Others took time to upgrade themselves through e-learning and self-development programs available from the firm’s existing licensed databases. Navigating employees out of their psychological barriers would require persistent effort and a genuine interest. Leaders who made a conscious effort to share the vision and dreams of their perceived future, and embrace the expectations of others helped them interpret the unfolding circumstances and challenges. In doing so, they brought some clarity and courage that helped themselves and others to grapple with the ensuing ambiguity.

Immersing in the problem to gain deeper and rare insights

Leadership vulnerability often gets exposed in times of crisis. Some leaders in Capital Co literally felt helpless about the pandemic. Not knowing how to plan forward led to mental and emotional exhaustion. The social, economic, and political impact of the virus was immense. Indeed, COVID-19 was a wakeup call and the only way to move forward would be to continue planning as though the virus would never disappear, but live in the present as though there was no tomorrow. In essence, the leaders chose the hard approach to continue chewing the problem while breathing through their curiosity with an open mind. Some leaders attempted a realistic approach to planning for unforeseen circumstances despite grappling with the new normal. In other words, they acted on their fear and doubt to make progress, Wishful thinking about when the ‘normal’ normal would resume was not part of their agenda. Instead, the pandemic made them view the external world through their stomachs (courage), desensitize their psychological immunity to the outbreak through their hearts (compassion), conceptualize a possible future through their minds (logic), and acting on what truly matters through their hands (engagement). A resolute view of the unresolved circumstances helped them keep pace with their psychological and emotional stability to anchor their day-to-day decisions.

Staying on course and visualizing the future despite the uncertainty did not particularly result in any potential solutions, but rather ruffled the way they wrapped their heads around the crisis. Some leaders had never been in such overwhelming doubt about the threat posed by the pandemic. Their concern was not merely about minimizing financial losses but rather optimizing resources to create a dramatic shift in their business orientation. Many had to get out of their comfort zone and view the world through a different perspective, largely from their stomachs (courage) rather than minds (logic). Being comfortable with their doubt depends on where leaders are sitting to view the situation, which is crucial for helping them interpret the crisis. Navigating through looming doubt is no easy feat for the leaders in Capital Co as they had to deal with external pressure to remain competitive and internal demands to keep cost at bay through potential layoffs. In doing so, they used a different narrative that confronted real issues at the ground level garnering the understanding and support of employees at all levels to achieve collective responsibility. However, being too comfortable with doubt could potentially lead to unintended complacency as some leaders simply did not feel the urge to revitalize their business prospects. They would rather wait and let nature take its course, but this would only result in their increased restlessness. A more ferocious appetite for change would probably serve the firm in a more positive light in times of crisis.

On a positive note, some leaders turned to the collective intelligence of their employees by engaging (hands) in their mental models to develop future scenarios. Abandoning their leadership wisdom (head), the leaders drew attention to their personal values (heart) and perceived risks (stomach) to work through the uncertainty along with their teams. Being sensitive to the deeper gifts of the employees challenged their doubt of the future in more meaningful ways. They realized the future of the firm would lie in the hidden intellectual treasures of their employees. More crucially, it took rare moments of vulnerability and doubt to gain a more hopeful view of the new normal. Tapping into deeper resources including the unspoken resilience of employees opened up new opportunities for change and development. Like leading a troop in an army, the battle is not just the commanders’ but also the soldiers’. It is a collective force that motivates leaders to harness a body of commitment and a spirit of trust in fighting against COVID-19.

Leading on: cultivating the core of you

This study suggests that the practice of leadership is much like gardening where the crisis presents the context for leaders to engage in people in much deeper ways. Attentiveness to employee wellbeing over business priorities in a crisis transposes leadership anatomy to a greater dynamic. For instance, the head must listen to the heart while the hands must follow the capacity of the stomach to create bold strokes. Like a gardener, the leader demonstrates care over the people (seeds), cultivates talent (soil), and removes unnecessary distractions (weeds) to ensure a healthy workforce (crop). Selection and planting of seeds is akin to the understanding of people – an art. There is a relational and material component to human interaction beyond socialization that nourishes people at the core. Maintaining the balancing act of leadership anatomy is always a challenge. It is not merely about keeping employees engaged (relational) and materially-satisfied (recognition), but more about harnessing the inner values and beliefs to bring out the greater good in others. All it takes is a listening heart to build and cultivate lasting and productive relationships.

Leading in turbulent times calls for the need to develop co-responsibility. Leaders need to empower and mobilize their people, and distribute their responsibility to others. This will create ripple effects of mutual interest by turning situations around and making work life more meaningful. Cultivating the crop is akin to reaching out and sharing ownership and responsibility with others to facilitate change. A gardener enjoys growth and harvest by building a relationship with his or her plants. It is a love that is cultivated in being (heart) and becoming (mind), accepting and embodying (hands), and recognizing and changing (stomach). Leading in turbulent times is all about working out work. Perhaps it is more about adaptive work by awakening the core of who you are as an individual and a leader. Being true to yourself offers you rare insights to help others navigate through uncertain times.

Leadership in practice: lessons learned

The paper concludes with some practical insights gleaned from the extant literature as outlined in the bibliographic section. First, for organizations to adapt to the shifting conditions of turbulence, leaders need to draw on their existing resources, processes, and systems to innovate and inject variations in their business conduct. By harnessing the collective intelligence of their employees, they could learn to create new dynamics and tensions that propel the organization out of the ordinary into extraordinary endeavors. In the face of wicked problems, leaders are expected to adopt wider learning capabilities by experimenting and adapting to massive change. Leaders should learn through execution in order to gauge the complexity of the circumstances while being open to provisional avenues for assumption testing. As such, strategy should be approached as an emergent, responsive, and adaptive process as rigorous planning might not necessarily lead to predictable outcomes.

Second, a key aspect of wicked problems is their elusive quality with no immediate and logical solutions. Decisive action would only intensify the problems rather than rectifying them. A fundamental step forward is to ask the right questions rather than finding the right answers. More critically, leaders should learn to depart from their expert contribution to one that deploys a wider variation and flexibility of techniques to reframe the problem and foster collective action. To explore breakthrough ideas and techniques, they should deploy the intellectual capacity of others as a spontaneous and evolving process both within and beyond the organization. In other words, leaders should minimize standardization and maximize opportunities for coactions based on shared principles and intentions.

Third, a significant step forward is to unlearn by letting go of habitual thought and action, and radically questioning boundaries of familiarity including power relations. The challenge is to maintain a delicate balance in the coordination of processes and human relations in the way leaders accept and reject as well as control and consent to emerging dynamics. At a deeper level, it is important to engage in the psychological and emotional experience of others by gaining genuine acceptance into their social world. This will allow leaders to view specific circumstances through the individual, unique perspective of their employees. The ability to appreciate and articulate the lived experience of others from a more intimate position offers renewed meaning, dynamic, and perhaps clarity to an otherwise chaotic world.

CRediT author statement

The paper was conceptualized, developed, written, and edited based on firsthand data collection by the sole author.

Jeff Gold: Resources.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Selected bibliography

This paper draws on the concepts of turbulence and complexity that characterize the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. The following work provides the context for the study as it introduces organizations as complex systems and adaptive leadership as working toward helping organizations respond to emergent disruptions and shocks. Organizations’ ability to self-organize not only helps them survive through tough times but also renew themselves to remain agile and nimble in response to rapid change. To gain a deeper understanding of complexity and chaos, read: R. Pascale, M. Milleman and L. Gioja, Surfing the edge of chaos: The laws of nature and the new laws of business (New York, NY: Three Rivers Press, 2001).

As the paper anchors on the importance of understanding complexity as affecting organizational change, the following study provides further insight into leadership influence and its impact on the strategic behavior of organizations. In framing the paper, I was curious about the shifting role of leaders in reconfiguring organizational systems and dynamics to garner the support of their employees to move toward a common goal. Read: P. Anderson, “Complexity theory and organization science,” Organization Science 10 (1999): 216−232. Research by the following scholars provides a multilevel analysis of organizational capabilities in the face of turbulence, which helped me develop a better understanding of the concept of leadership resilience. Read: J. McCann, J. and J.W. Selsky, “Not A, not R – it’s AR’, in J. MCann and J. W. Selsky (eds.), Mastering turbulence: The essential capabilities of agile and resilient individuals, teams and organizations (1st ed.) (35–41) (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2012).

Several years ago I came across the concept of wicked problems introduced by Keith Grint and two of his following works helped me frame COVID-19 as a type of wicked problem given the extensive impact of the pandemic on the world economy. Read: K. Grint, “Problems, problems, problems: The social construction of ‘leadership’”, Human Relations 58 (2005): 1467−1494. Read also: K. Grint, K., “Wicked problems and clumsy solutions: The role of leadership, in S. Brookes and K. Grint (eds.), The new public leadership challenge (pp. 169–186) (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). Writing the research in the midst of an impending pandemic made me realize that the conventional practice of leadership might be deeply challenged in times of complexity. I then engaged in the action learning literature to explore the concept of unlearning and the following study became of relevance. Read: M. Pedler and S. Hsu, “Unlearning, critical action learning and wicked problems”, Action Learning: Research and Practice 11 (2014): 296−310.

When I first heard of adaptive leadership I was immediately drawn to the significance of the concept to current uncertain times. I found the following book helpful in framing leadership as a practice rather than theory. Read: R.A. Heifetz, M. Linsky and A. Grashow, The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2009). Being adaptive requires that leaders engage in deep sensemaking of contexts and paradigms. The following book details different scenarios of how sensemaking played out in the decision making processes of leaders in circumstances over which they had no direct control. Read: K.E. Weick and K.M. Sutcliffe, Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty (2nd ed.) (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2007).

This paper builds on the current conversation around the impact of COVID-19 on leadership and organizations, and the following study caught my attention. Read: G. Seijts, K.Y. Milani, “The myriad ways in which COVID-19 revealed character”, Organizational Dynamics (2020), https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2020.100765. Research on leader character has always been an interest to me and an earlier study by Seijts and his colleagues provided some empirical basis for me to explore the unfolding values and beliefs of leadership in a crisis setting. Read: G. Seijts, J. Gandz, M. Crossan and M. Reno, “Character matters: Character dimensions’ impact on leader performance and outcomes”, Organizational Dynamics 44 (2015): 65−74. As my study progressed, I realized the importance of leaders harnessing their emotions so that compassion and understanding for others could be clearly expressed. I found the following study on authentic leadership of relevance as it offers a further understanding of how leaders reconcile and manage their authentic selves. Read: S. Michie and J. Gooty, “Values, emotions, and authenticity: Will the real leader please stand up?”, The Leadership Quarterly 16 (2005): 441−457. The concept of servant leadership which I first heard of from Ken Blanchard intrigued me and a recent study illustrates how leaders could manage their emotional landscape to respond to the suffering of others through compassion and humility. Read: B. Davenport, “Compassion, suffering and servant-leadership: Combining compassion and servant-leadership to respond to suffering”, Leadership 11 (2015): 300−315.

The methodological paradigm of para-ethnography became of relevance when I was conducting this study. As I was closely intertwined with the case organization’s dynamics and activities, I found myself relating to the interviewees on more intertextual levels. The following paper helped me theorize the interlocking dynamics of my research context by being an insider and outsider. Read: G. Islam, “Practitioners as theorists: Para-ethnography and the collaborative study of contemporary organizations”, Organizational Research Methods, 18 (2015): 231−251. Understanding my role and that of others during the research could be complex, but hearing the deeper voice of those with whom I interacted helped me appreciate the significance of the bounded and unbounded selves. Gergen’s book inspired me to find my voice. Read: K.J. Gergen, Relational being: Beyond self and community (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009). Finding that voice was crucial as I was able to identify what truly matters as a researcher and participant. The following paper helped me discover that voice. Read: A. Edwards and H. Daniels, “The knowledge that matters in professional practices”, Journal of Education and Work 25 (2012): 39−58.

At the end of the research, I realized that I had a renewed connection with myself and others in search of a deeper voice. Kegan’s work inspired me to be both reflexive and practical in discovering the ‘self’ as a motivation for enabling meaningful change. The context of COVID-19 with lockdowns and curfews presented an ‘abnormal’ normal context from which to review my inner and outer worlds. Read: R. Kegan, The evolving self: Problems and processes in human development (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982). For a wider perspective, read: R. Kegan and L.L. Lahey, Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock the potential in yourself and your organization (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2009)

Acknowledgments

The author appreciates the candidness of the interviewees who shared their stories and perspectives during the course of the research at a time of COVID-19. The opportunity provided by the case organization to learn about their response to the health crisis is also acknowledged. Finally, feedback from the reviewers is deeply appreciated as it helped sharpen the focus of the paper.

Biography

Roland K. Yeo (University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, and King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals, PO Box 12979, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia e-mail: e-mail: Roland.Yeo.OBA@said.oxford.edu, roland.yeo@unisa.edu.au) Roland K. Yeo holds a Ph.D. in Organization Studies from the Leeds Business School in UK and postgraduate degrees from the University of Oxford and HEĆ Paris. He is currently based in Saudi Aramco as Strategic HR Advisor and is associated with the University of South Australia Business School (AACSB) as Adjunct Senior Research Fellow. He is also Adjunct Professor of Management at the King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals in Saudi Arabia involved in the teaching of their Executive MBA program (AACSB). Roland is an advocate of practice-based research and is currently working on crisis-induced leadership behavior, work reengagement, and knowledge spillovers through the shadow of learning, a process of intraorganizational learning.