Abstract

Purpose

The objective of the present study was to purify sheep spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) from testicular isolate using combined enrichment methods and to study the effect of growth factors on SSC stemness during culture.

Methods

The testicular cells from prepubertal male sheep were isolated, and SSCs were purified using Ficoll gradients (10 and 12%) followed by differential plating (laminin with BSA). SSCs were cultured with StemPro®-34 SFM, additives, and FBS for 7 days. The various doses (ng/ml) of growth factors, EGF at 10, 15, and 20, GDNF at 40, 70, and 100 and IGF-1 at 50, 100, and 150 were tested for the proliferation and stemness of SSCs in vitro. The stemness in cultured cells was assessed using SSC markers PLZF, ITGA6, and GFRα1.

Results

Ficoll density gradient separation significantly (p < 0.05) increased the percentage of SSCs in 12% fraction (35.1 ± 3.8 vs 11.2 ± 3.7). Subsequently, purification using laminin with BSA plating further enriched SSCs to 61.7 ± 4.7%. GDNF at 40 ng/ml, EGF at 15 and 20 ng/ml and IGF1 at 100 and 150 ng/ml significantly (p < 0.05) improved proliferation and stemness of SSCs up to 7 days in culture. GDNF at 40 ng/ml outperformed other growth factors tested and could maintain the ovine SSCs proliferation and stemness for 36 days.

Conclusions

The combined enrichment method employing density gradient centrifugation and laminin with BSA plating improves the purification efficiency of ovine SSCs. GDNF at 40 ng/ml is essential for optimal proliferation and sustenance of stemness of ovine SSCs in vitro.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-020-01912-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Spermatogonial stem cells culture, Purification, Growth factors, Stemness maintenance, Sheep

Introduction

SSCs physiology and potential use of these cells are less studied in livestock when compared with rodents and humans [1]. In livestock, SSCs have numerous applications including transplantation of SSC for wider dissemination of superior germplasm, transgenesis, cloning, and regenerative medicine. The technologies involved in isolation, purification, long-term culture of SSCs and subsequent production of transgenic animals are well studied in rodents [2–4]. A milestone has been reached in primates, with the successful production of offspring from cryopreserved testes grafted onto autologous rhesus monkeys [5]. However, in livestock the application of SSC technology is advancing with different pace [1, 6]. The possible reasons for the slow progress of SSCs technology in livestock are inadequate methodologies in obtaining purified SSCs from the testicular cells, lack of identified SSCs markers in livestock, and non-availability of defined culture media for sustaining stemness during long-term proliferation in vitro [7, 8].

Isolation of SSCs free from differentiating germ cells and somatic cells in the testicular isolate is a prerequisite for developing a suitable culture system. The population of SSCs in testicular cells isolate is extremely low, for example, 0.02–0.03% in mice [9, 10] and 0.18–0.47% in adult sheep [6]. Single enrichment protocols with laminin in laboratory animals [11] and laminin in combination with bovine serum albumin (BSA) in sheep [6] were used for enriching SSCs. The purity of SSCs has been improved when the enrichment methods were combined and adopted. Differential plating using gelatin (0.1%) and Percoll density gradient centrifugation increased the purity of SSCs (UCHL1 + cells) to 60% in buffalo [12]. In another study, laminin followed by the Ficoll enrichment yielded up to 84% GDNF family receptor alpha-1 positive (GFRα1 + cells) SSCs in cats [13]. In sheep, in comparison of different extracellular matrix substances for purification of SSCs, we found that laminin in combination with BSA enriched sheep SSCs to 36% [6]. Further to improve the purification efficiency of sheep SSCs for in vitro culture, laminin in combination with BSA can be explored after density gradient centrifugation as reported in other species. However, such studies have not been conducted in sheep.

The requirements for the species-specific culture components for the SSC culture are unique for a particular species [14–16]. The stemness in the cultured cells are maintained by overcoming the apoptosis and differentiation in the culture [1] and in this regard, growth factors are reported to be integral components to the culture medium [17]. The growth factors such as glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) in the culture medium have been used for maintaining proliferation and stemness of SSCs in short- and long-term culture in various species [18–21]. GDNF produced by Sertoli cells has receptors on the SSCs [22]. GDNF acts in a paracrine manner through Src signaling and Ras signaling pathways for SSC self-renewal in the testis [23]. The EGF and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promotes the overexpression of cyclo-oxygenase 2 [24] and activates the JAK-STAT pathway for the self-renewal and proliferation of stem cells [25]. Recent studies documented that the addition of IGF1 in SSCs culture promotes proliferation and stemness through HIF-2α-OCT4/CXCR4 loop [7, 19].

The effect of these growth factors and the appropriate dose required for the sustenance of stemness and proliferation of ovine SSCs in culture have not been established. To the best of our knowledge, only one ovine SSC culture study documented the SSC isolation and culture procedure; however, the sufficient enrichment was not obtained. In that study, the cultured cells were also not checked for SSCs markers or stemness functional assay [26]. Hence, the objective of the present study was (i) to improve the purification efficiency of SSCs from the initial testicular isolate using the combined enrichment method and (2) to assess the efficiency of different doses of growth factors such as GDNF, EGF, and IGF1 for promoting proliferation and maintenance of stemness of ovine SSCs in vitro.

Materials and methods

Procurement and processing of the samples

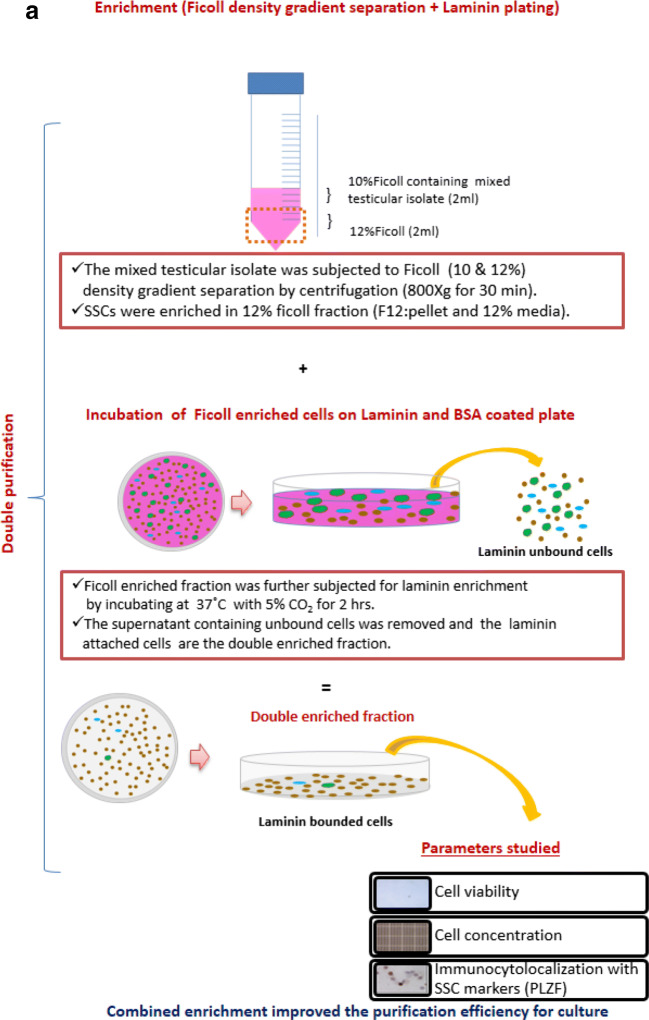

The experiment was conducted in accordance with Institutional Animal Ethics committee approval. The testes samples were procured from the corporation slaughterhouse and transported to the laboratory in ice-cold saline within 2 h. The testes samples (n = 6) from prepubertal (average weight of testis used: 19.1 ± 1.2 g) sheep were used in the present study. After removing the tunica vaginalis and epididymis, testicular parenchyma was excised and enzymatically digested. The whole testicular isolate thus obtained was subjected for SSCs isolation, enrichment, and culture. The overview of the methodology followed for the SSC enrichment and culture is presented (Fig. 1a & b).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the methodology followed for the (a) combined enrichment of the isolated sheep spermatogonial stem cells. (b) Sheep spermatogonial stem cell culture on laminin coated plates using different growth factors such as GDNF, EGF, and IGF1

Isolation of putative SSCs

The putative SSCs from the pre-pubertal sheep testis were isolated using collagenase at 2 mg/ml (c5138, Sigma-Aldrich, Bengaluru) and trypsin at 0.5 mg/ml (TCL006, Himedia, India) as reported earlier [6]. Following isolation, the pellet containing testicular cells were suspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Combined enrichment with Ficoll density gradient separation and differential plating

The percentage of putative SSCs in the initial isolate was estimated by using the stem cell marker, promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein (PLZF). Furthermore, to improve the purification efficiency, a combined enrichment method was adopted. Initially, the isolated testicular cells were mixed with 10% Ficoll and layered over the 12% Ficoll for the density gradient centrifugation [27]. The cells obtained from each fractions were washed after Ficoll density gradient separation. The viability, concentration, and the percentage of putative SSCs were calculated in the initial isolate and in the 10 and 12% Ficoll fraction. The putative SSCs enriched fraction (12% Ficoll fraction) was further subjected to differential plating with extracellular matrix (ECM), laminin (20 μg/ml; L2020, Sigma-Aldrich, Bengaluru) in combination with BSA [6]. The purified fraction was plated onto laminin and BSA coated 34.8 mm plates. The plates were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The attached cells on the laminin-coated plates were the double-enriched fraction containing putative SSCs. The attached cells were collected following trypsinization by incubating the plate with 0.025% trypsin-EDTA in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) for 6 min at 37 °C. Trypsin action was terminated by adding an equal volume of DMEM containing 5% FBS. The media containing cells were collected and centrifuged at 1700 rpm for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in DMEM with 5% FBS. The viability, concentration and the percentage of putative SSCs were also calculated after combined enrichment procedure.

SSC attributes

Concentration

The number of SSCs obtained following isolation and after each step of enrichments from per gram of the testis was calculated using a hemocytometer. Based on the immunocytochemistry (ICC) results using the PLZF as a marker, the number of putative SSCs/g of the testis was calculated in the initial isolate and enriched fractions.

Viability

The viability of the isolated and enriched cells was assessed by trypan blue (0.5%) staining. The cells with blue color were considered as dead and those did not take up the stain were considered as viable. The cells were observed at × 400 magnification and the percentage of viability was calculated.

Localization of SSC markers in the isolated and enriched testicular cells

The clear grease-free glass slides were coated with poly-l-lysine (P8920, Sigma, USA) and the putative SSCs were localized using the PLZF marker as described earlier [6]. Briefly, the smears were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and rinsed with TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20). Then, the slides were incubated in 0.01% Triton-X in TBS (Tris-buffered saline) for 5 min and washed with TBS. Subsequently, the slides were incubated in TBS containing 0.6% H2O2 for 20 min to retrieve antigen and blocked with 3% BSA in TBST at room temperature (25–28 °C) for 30 min. The smear was incubated with primary antibody (rabbit polyclonal IgG: PLZF, 1:100 dilution, sc-22839, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA) at 4 °C for overnight. After incubation, the slides were washed three times using TBST for 5 min each and incubated with secondary antibody (105499, goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP, GeNei, India) at room temperature for 30 min. The slides were washed three times with TBST for 5 min each and incubated with DAB substrate for 10 min for the development of brown color. For negative controls, the smears were incubated in the TBST without the primary antibody. The cells were counterstained with hematoxylin. The cells were observed under × 400 magnification using phase-contrast microscope (Nikon 80i, Nikon, Japan) and the percentage of putative SSCs (PLZF+) were calculated.

SSC culture

Following isolation of testicular cells, the initial isolate containing relatively lesser numbers of putative SSCs were subjected to double purification procedures using the Ficoll density gradient centrifugation followed by laminin plating. Following Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, the enriched fraction containing putative SSCs were cultured onto the laminin coated 48 well plates (The surface area of each well in the 48 well plates is approximately 0.95 cm2.) The seeding density for the culture was 0.05 × 106 cells/well in the 48 well plates. The putative SSCs were cultured at 37 °C under 5% CO2 and maintained for 7 days in the culture media consisting of the StemPro®-34 SFM (serum-free medium with StemPro® nutrient supplement), additives (Supplementary Table 1), FBS and growth factors in various doses (EGF at 10, 15, and 20 ng/ml; GDNF at 40, 70, and 100 ng/ml; and IGF-1 at 50, 100, and 150 ng/ml). The culture medium was changed once every 48 h.

The doses of growth factors were selected based on the meta-analysis of the literatures (Supplementary Table 2). The concentrations (ng/ml) of EGF at 10 (Group: E10), 15 (Group: E15) and 20 (Group: E20); GDNF at 40 (Group: G40), 70 (Group: G70) and 100 (Group: G100); and IGF1 at 50 (Group: I50), 100 (Group: I100), and 150 (Group: I150) were added to the culture media. The medium composition of the control (C) was similar to the other groups but without any growth factors. The colony morphology was recorded during the media change and on termination of the culture.

Harvesting of the cultured cells

After 7 days of culture, the cells were harvested using the enzymes, namely collagenase and trypsin. Briefly, the culture media were aspirated from the cultured plates and the plates were washed twice with DPBS. The culture wells were added with collagenase (2 mg/ml) in DPBS and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After incubation, the plates were gently tapped and pipetted the media to allow the detachment of the cells from the plate. The plates were observed under the stereo zoom microscope (Meiji, USA) to confirm the complete detachment of the cells from the plate. Further, 0.5% trypsin containing 2% EDTA in DPBS was added to the well and incubated under a similar condition for 5 min. Then, the complete media containing dissociation cells were pipetted out of the well and an equal volume of DMEM containing 5% FBS was added to inactivate the enzymes.

Estimation of cultured cell characteristics

Cell concentration and viability

In the cultured cells, the concentration and viability were estimated as per the procedure described earlier.

Localization of SSC markers (PLZF, ITGA6, and GFRα1)

To determine the stemness and self-renewal capacity of putative SSCs, various stem cell markers, PLZF, Integrin alpha6 (ITGA6), and GFRα1 were localized in the harvested cells (day 7). The primary (rabbit polyclonal IgG: PLZF; 1:100, rabbit polyclonal IgG: ITGA6; 1:100, rabbit polyclonal IgG: GFRα1; 1:300) antibodies were added to the cells smeared on to the slides and incubated for overnight at 4 °C. The secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP, GeNei, India; 1:500) were added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The rest of the procedure followed is the same as described earlier for PLZF localization except for ITGA6 and GFRα1, in which, the Triton-X incubation step was not carried out as ITGA6 and GFRα1 were the surface markers.

Cell morphology documentation

The cell morphology was estimated in the harvested cells on the 7th day culture. The size and shape of the cultured cells were documented under × 400 magnification using a phase-contrast microscope. The nuclear morphology was studied in cultured SSCs after stained with DAPI. The cell stages were assessed after observing the nuclear morphology under a fluorescent microscope (Nikon 80i, Nikon, Japan).

Subculturing and stemness assessment

Since, the GDNF 40 ng/ml yielded higher proliferation rate and stemness as compared with other growth factors, the subculturing of SSCs were carried out with the media containing GDNF 40 ng/ml. The SSCs were maintained for four passages and expression of stemness markers (PLZF, ITGA6, and GFRα1) was carried using immunocytochemistry in the cultured cells. The cultured cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and rinsed with DPBS. Then, the slides were incubated in 0.01% Triton-X in DPBS for 5 min and washed twice with DPBS. The sections were blocked with 3% BSA in DPBS at room temperature for 1 h. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies (sc-22839, rabbit polyclonal IgG: PLZF, 1:100 dilution, sc-10730, rabbit polyclonal IgG: ITGA6, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA; 1:100, PAS-19873, rabbit polyclonal IgG: GFRα1; 1:300, Invitrogen, USA) in blocking buffer, overnight at 4 °C. Further, incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies in darkness at 1:500 dilution (Cat no: sc-516250, mouse anti-rabbit IgG-CFL 594 and sc-2990, chicken anti-rabbit IgG FITC, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). The cells were counterstained with DAPI (1 μg/ml). The cells were mounted with the antifade agent (ProLong diamond antifade, Invitrogen, Thermofisher, USA) and visualized under a fluorescent microscope (Nikon 80i, Nikon, Japan). The image analyses were performed using the NIS-Elements BR, (Version 3.1) software (Nikon, Japan). The intensity was measured by using Fiji software (version 1.46). The RGB channels were split and the threshold was set with default algorithm to the desired channel, and the intensity was measured by considering the mean intensity of the threshold image.

Stemness marker genes (PLZF, ITGA6, GFRα1, UCHL1, and CDH1), pan germ cell marker (VASA) and differentiating gene expression marker (cKIT) were studied in passage 3 and passage 4 using qPCR. The total RNA was isolated from cultured cells by kit method [28] and the quality of the isolated RNA was checked using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 1000, Thermo Scientific, USA). The primers were designed using the Primer-Blast software (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). The qPCR was carried out using SYBR green master mix (K0221, Thermo Scientific, Maxima SYBR Green/Rox PCR Master Mix, USA) and the relative quantification of the SSCs stemness, pan germ cell marker and differentiating germ cells were estimated using ACTB as the reference gene. The relative expression of these genes was calculated using 2−ΔΔCT [29].

Statistical analysis

The percentage data were arcsine transformed and analyzed using statistical software SPSS-15 (SPSS Corporation, USA). One-way ANOVA coupled with the LSD post-hoc test was employed for assessing the significant difference in the viability, concentration, and PLZF expressing cells in the initial testicular cell isolate and enriched SSCs. For assessing the variations in the concentration, viability, stem cell markers (PLZF, GFRα1, and ITGA6) expressing cells among the cultured groups, one-way ANOVA coupled with the LSD post-hoc test was employed. The relative expression of genes between passage 3 and passage 4 was calculated by considering the expression level of passage 3 as onefold. All the values are presented as mean ± SEM. The significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Isolation of putative SSCs

The average number of mixed testicular cells obtained following the enzymatic isolation was 17.7 ± 2.8 × 106 and the subpopulation of putative SSCs in the mixed population was 2.0 ± 0.30 × 106 cells per gram of the prepubertal sheep testis. The isolation of SSCs from prepubertal sheep testes employing the two-step enzymatic method yielded 11.2 ± 3.7% putative SSCs (PLZF + cells). The viability of the initial testicular cells isolate was 72 ± 4.1%.

Enrichment of putative SSCs using combination of Ficoll enrichment and laminin plating

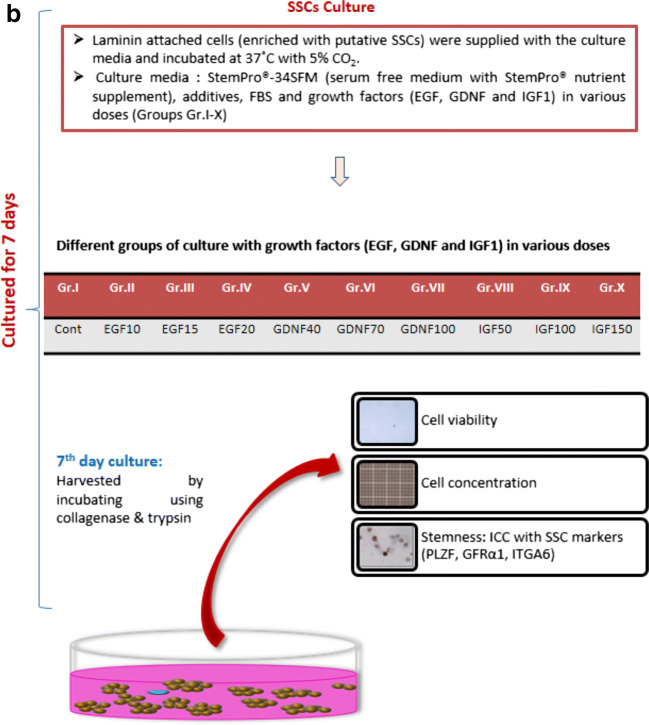

SSCs enriched fractions from Ficoll density gradient (F12) on subjecting to the second step of purification using laminin plating enriched the percentages of SSCs significantly (p < 0.05) when compared with the initial isolate (Table 1). After the first purification step, 27.4% and following the second purification step (laminin plating) only 1.8% of initially isolated cells were available for the culture. The remaining, mainly somatic and differentiating germ cells were discarded at different stages of purification, i.e., during Ficoll enrichment, laminin plating, and also during different washing steps followed in the protocol. The double purified fraction yielded a higher number of PLZF+ viable cells of uniform size and shape (Fig. 2). From each gram of the testicular tissue, the single purification procedure yielded 1.7 ± 2.8 × 106 PLZF+ cells, whereas the double purification yielded 0.19 ± 0.05 × 106 PLZF+ cells. The double enriched fraction had 61.7 ± 4.7% of PLZF +cells with 66.9 ± 6.2% viability and was subsequently used for culturing of the SSCs.

Table 1.

SSCs from the initial testicular isolate were enriched using combined enrichment method. As a first step, Ficoll at 10 and 12% gradients where used in which, SSCs were enriched in 12% Ficoll fraction (single purification, F12: pellet and 12% media). The cells in F12 fraction were further subjected to purification using laminin and BSA plating. Cells positive for PLZF (SSC marker) and viability after second enrichment procedure was significantly higher as compared to single and initial isolate

| Parameters | Without purification, initial isolate | Single purification, F10 fraction | Single purification, F12 fraction | Double purification, DF12 fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLZF +(%) | 11.2 ± 3.7a | 4.5 ± 0.5 a | 35.1 ± 3.8bc | 61.7 ± 4.7c |

| Viability (%) | 72.0 ± 4.1c | 60.5 ± 7.5ab | 51.2 ± 6.5a | 66.9 ± 6.2b |

| Number of cells (X106/g of the testis) | 17.7 ± 2.8 | 5.2 ± 2.64 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

Values in a row with different superscripts (a, b, c) differ significantly (p < 0.05), n = 6

F10 fraction: enriched cells from 10% Ficoll fraction; F12 fraction: enriched cells from 12% Ficoll fraction; DF12 fraction: F12 fraction followed by laminin enrichment

Fig. 2.

The representative figure showing (a) morphology, (b) viability, (c) PLZF+ cells in initial isolate, and enriched (the 12% fraction from Ficoll density gradient separation was subjected to second purification using differential plating on laminin and BSA coated plates) SSCs. More uniform sized cells with 66% viability and 61% PLZF+ cells were obtained after the combined enrichment procedure. (c) Brown-colored cells are positive for SSC marker PLZF and purple-colored cells (counterstained by hematoxylin) are negative for PLZF marker. Magnification × 40

Proliferation, stemness, and viability of cultured cells

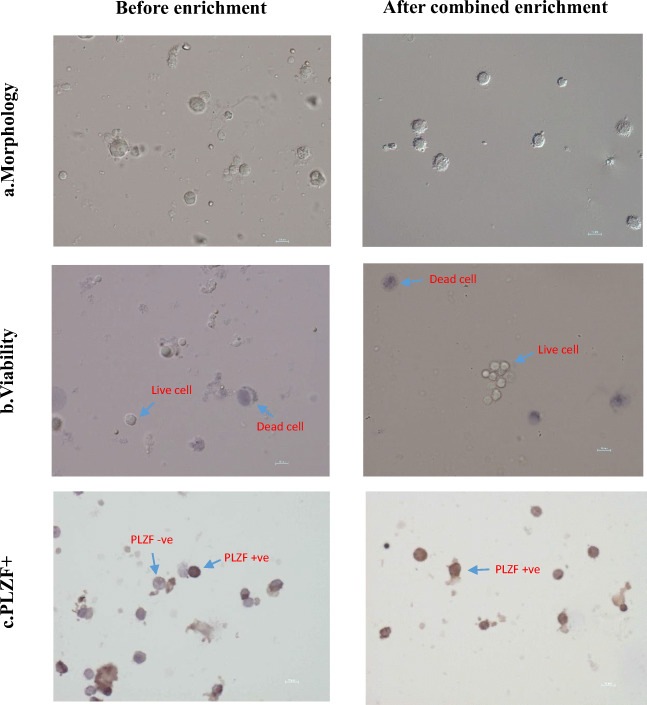

The SSC culture was maintained in the laminin-coated plates, supplied with the culture media (StemPro media, StemPro nutrients, additives, and FBS (10%) and growth factors. The SSC colonies started developing from the initial cell densities and the colony reached 80–90% confluency by day 7 (Fig. 3a). At the end of 7 days culture, the number of cells increased significantly (p < 0.05) in E15, E20, I100, I150, and G40 (p < 0.01) groups as compared with the number of cells on the day 0 (Table 2). Within 7 days of culture, the cell numbers increased to 3.1 ± 0.8 fold in the GDNF40 group and the majority of the groups supplemented with growth factors had doubled the cells in the culture (Fig. 4). With the selected growth factor GDNF 40 ng/ml, the SSC culture was maintained in the laminin-coated plates with the culture media (StemPro media, StemPro nutrients, additives, and FBS (10%) for 36 days (4 passages) (Fig. 3ab).

Fig. 3.

(a) Representative figure of SSC colonies during different days of culture (passage 0). Putative SSCs colonies were formed on fourth day of culture and by seventh day well-developed SSC colonies were formed. (b) Representative figure of SSC colonies during different passages (passage 1: 14th day, passage 2: 21st day, passage 3: 28th day, passage 4: 36th day). Magnification × 40

Table 2.

Effect of different growth factors on the proliferation and viability of SSCs in culture. SSC culture were maintained under the influence of different growth factors, epidermal growth factor at the rate of 10 (E10), 15 (E15), 20 (E20) ng/ml, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic growth factor at the rate of 40 (G40), 70 (G70), 100 (G100) ng/ml, insulin-like growth factor-1 at the rate of 50 (I50), 100 (I100), and 150 (I150) ng/ml and control (without growth factor) for 7 days. The seeding cell group is the cells on day 0 culture

| Parameters (n = 6) | Seeding cells | Control | E10 | E15 | E20 | G40 | G70 | G100 | I50 | I100 | I150 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (× 104 cells/well) | 5.4 ± 0.0a | 7.8 ± 0.0 | 12.2 ± 0.0 | 13.6 ± 0.0b | 14.3 ± 0.0b | 17.1 ± 0.0c | 8.8 ± 0.01 | 7.0 ± 0.02 | 10.9 ± 0.01 | 14.2 ± 0.05b | 13.1 ± 0.03b |

| Viability (%) | 75.4 ± 6.3x | 94.3 ± 1.8y | 96.0 ± 1.6y | 93.8 ± 1.9y | 93.2 ± 2.4y | 94.0 ± 2.0y | 92.2 ± 1.8y | 94.5 ± 1.1y | 92.8 ± 2.1y | 95.3 ± 1.4y | 97.2 ± 0.6y |

n = 6. x,yp < 0.05, a,cp < 0.01

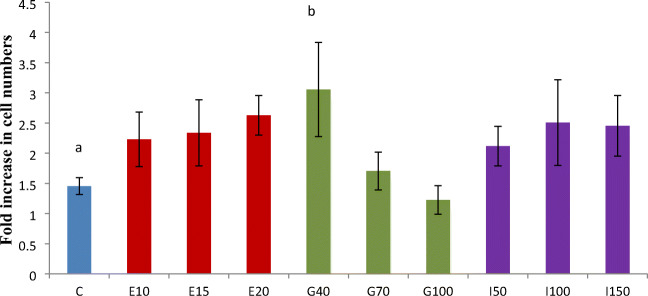

Fig. 4.

Effect of different growth factors on the proliferation (fold increase in the number of cultured cells as on seventh day) of putative SSCs following 7 day of culture. The seeding cell concentration is considered as fold 1. SSCs were cultured without any growth factors (control) and with growth factors such as epidermal growth factor at the rate of 10 (E10), 15 (E15), and 20 (E20) ng/ml; glial cell line–derived neurotrophic growth factor at the rate of 40 (G40), 70 (G70), and 100 (G100) ng/ml; insulin-like growth factor-1 at the rate of 50 (I50),100 (I100), and 150 (I150) ng/ml. The values with different superscript differ significantly (p < 0.05)

The stemness of the cultured cells was assessed using three SSC markers, PLZF, ITGA6, and GFRα1 (Fig. 5 and Table 3). The harvested cells were spherical in shape and the average diameter of the cells is 15.4 ± 0.3 μm (Fig. 5). The cells in the culture were in the different phases of growth (G0, G1, S, G2) and mitotic division stages such as prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, telophase, and cytokinesis (Supplementary Fig. 1). The viability (%) of the cultured cells was significantly (p < 0.01) higher than the viability of the seeded cells. However, the viability percentage of the cultured SSCs did not differ significantly among the various treatments and control groups (Table 2).

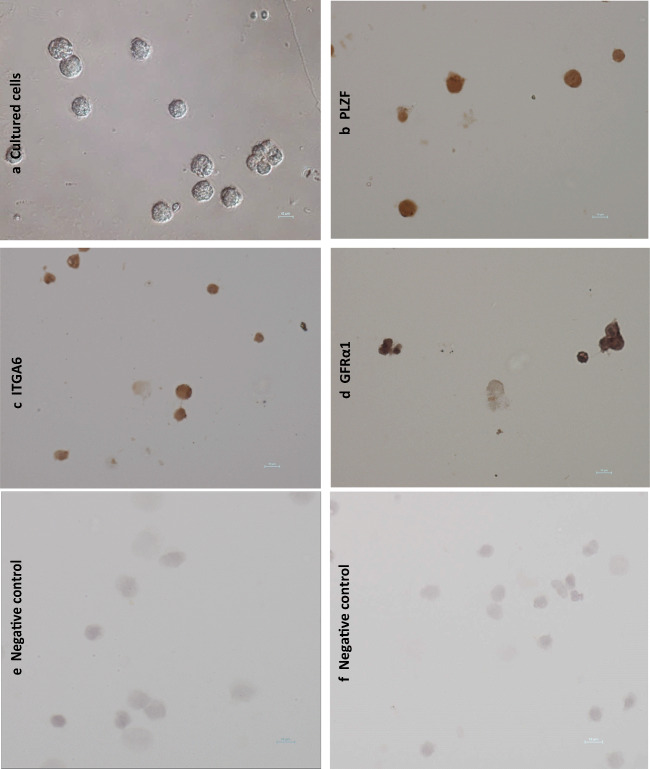

Fig. 5.

The representative figure of (a) harvested cells from the 7 days ovine SSC culture. Immunocytolocalization using SSC markers (b) PLZF, (c) ITGA6, and (d) GFRα1 in cultured cells. The brown-colored cells in b, c, and d are positive for the SSCs marker. e, and f. representative figure for the negative control for the SSC markers. Magnification × 40

Table 3.

The stemness of ovine SSC in culture as assessed using PLZF, ITGA6, and GFRα1 as SSC markers. The percentages of PLZF, ITGA6, and GFRα1 positive cells in the SSCs cultured for 7 days with different doses of growth factors namely, epidermal growth factor at 10 (E10), 15 (E15), and 20 (E20) ng/ml; glial cell line–derived neurotrophic growth factor at 40 (G40), 70 (G70), and 100 (G100) ng/ml and insulin-like growth factor-1 at 50 (I50), 100 (I100), and 150 (I150) ng/ml. n = 6

| SSC markers | Control | E10 | E15 | E20 | G40 | G70 | G100 | I50 | I100 | I150 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLZF+ (positive, %) | 76 ± 3 | 70 ± 8 | 78 ± 8 | 76 ± 5 | 84 ± 3 | 81 ± 3 | 69 ± 5 | 76 ± 5 | 79 ± 4 | 78 ± 4 |

| ITGA6 + (positive, %) | 69 ± 7 | 59 ± 9 | 76 ± 8 | 74 ± 5 | 72 ± 7 | 75 ± 6 | 64 ± 9 | 76 ± 5 | 78 ± 3 | 81 ± 3 |

| GFRα1+ (positive, %) | 74 ± 7 | 68 ± 7 | 75 ± 7 | 70 ± 10 | 80 ± 6 | 74 ± 6 | 74 ± 7 | 71 ± 7 | 83 ± 4 | 73 ± 7 |

Values did not differ significantly between the control and the treatment groups

Influence of growth factors and their concentration on SSC stemness on day 7

PLZF

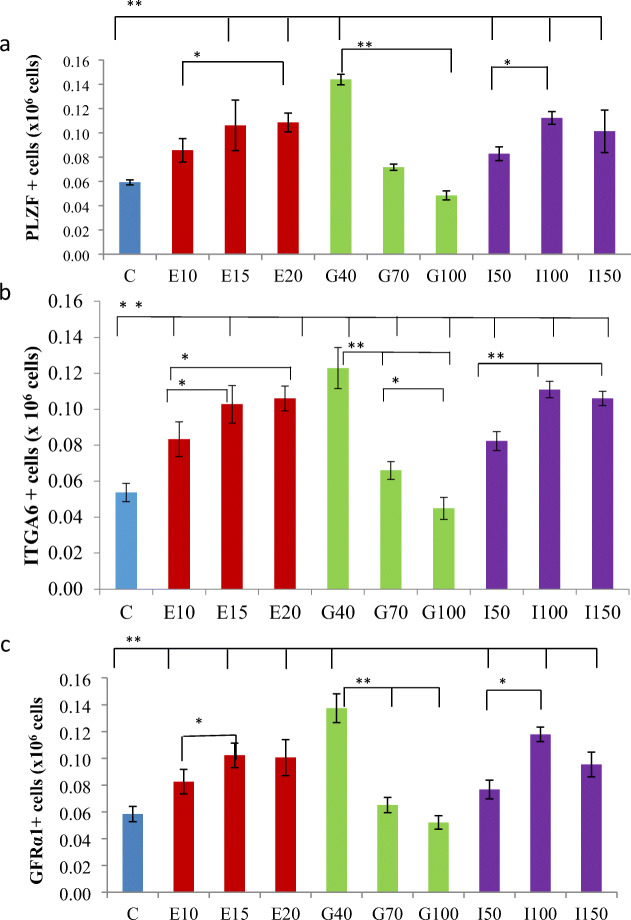

The number of PLZF positive cells was significantly (p < 0.01) higher in the group supplemented with EGF at 15 and 20 ng/ml; GDNF at 40 ng/ml; and IGF1 at 50, 100, and 150 ng/ml than the control. Among the GDNF supplemented groups, the GDNF 40 ng/ml had significantly (p < 0.01) higher PLZF+ cells than those with GDNF 70 ng/ml and GDNF 100 ng/ml. Among the IGF1 groups, the cells cultured with the dose rate of 100 ng/ml proliferated significantly (p < 0.05) than the other doses, 50 ng/ml and 100 ng/ml (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

The stemness and proliferation rate of ovine SSC in culture as assessed using (a) PLZF, (b) ITGA6, and (c) GFRα1 as SSC marker. The total number of PLZF, ITGA6, and GFRα1 positive cells in the cultured SSCs (after 7 days of culture) with different doses of growth factors, namely epidermal growth factor at 10 (E10), 15 (E15), and 20 (E20) ng/ml; glial cell line-derived neurotrophic growth factor at 40 (G40), 70 (G70), and 100 (G100)ng/ml and insulin-like growth factor-1 at 50 (I50), 100 (I100), and 150 (I150)ng/ml. The expression of SSCs marker on seventh day in vitro-cultured ram SSCs were estimated using immunocytochemistry

ITGA6

The number of ITGA6+ cells were significantly (p < 0.01) higher in the culture media supplemented with the growth factors, EGF at 10, 15, and 20 ng/ml; GDNF at 40 ng/ml; and IGF1 at 50, 100, and 150 ng/ml than the SSCs cultured without the growth factor. Among the GDNF supplemented groups, the culture media containing GDNF 40 ng/ml had significantly (p < 0.01) higher ITGA6+ cells than those with GDNF 70 ng/ml and 100 ng/ml. Further, G70 group had significantly (p < 0.05) higher ITGA6+ cells than G100. Among the IGF1 groups, the cultured cells maintained with the dose rate of 100 ng/ml had significantly (p < 0.05) higher ITGA6+ cells than 150 ng/ml (Fig. 6b).

GFRα1

The number of GFRα1+ cells was significantly (p < 0.01) higher in the culture media supplemented with the growth factors, EGF at 10, 15, and 20 ng/ml; GDNF at 40 ng/ml and IGF1 at 50, 100, and 150 ng/ml than the control. Within the GDNF supplemented groups, culture media containing GDNF 40 ng/ml had significantly (p < 0.01) higher GFRα1+ cells than GDNF 70 ng/ml and GDNF 100 ng/ml. Among the IGF1 groups, the cultured cells maintained with a dose rate of 100 ng/ml proliferated significantly (p < 0.05) than 50 ng/ml (Fig. 6c).

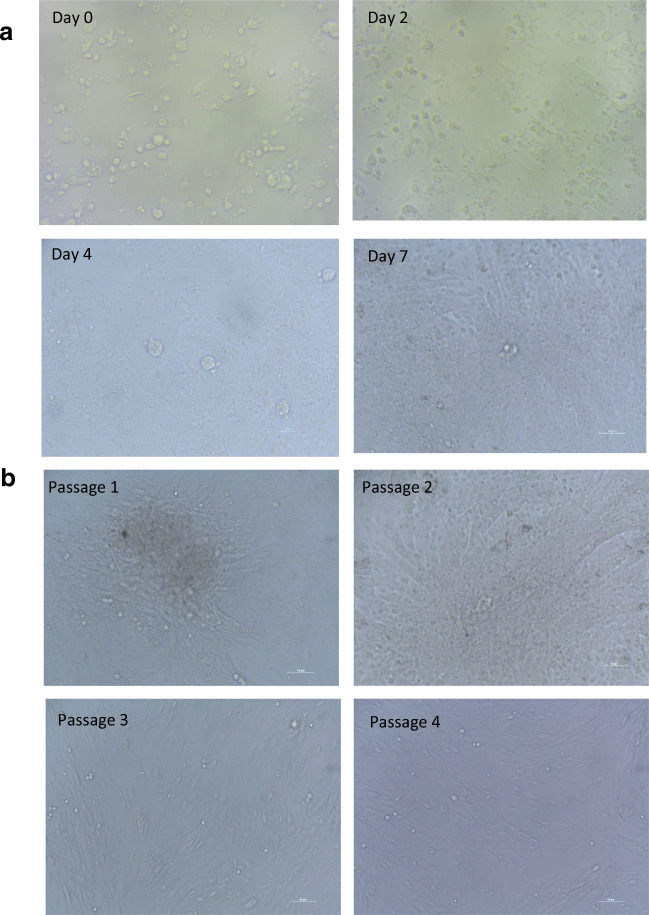

Long-term culture

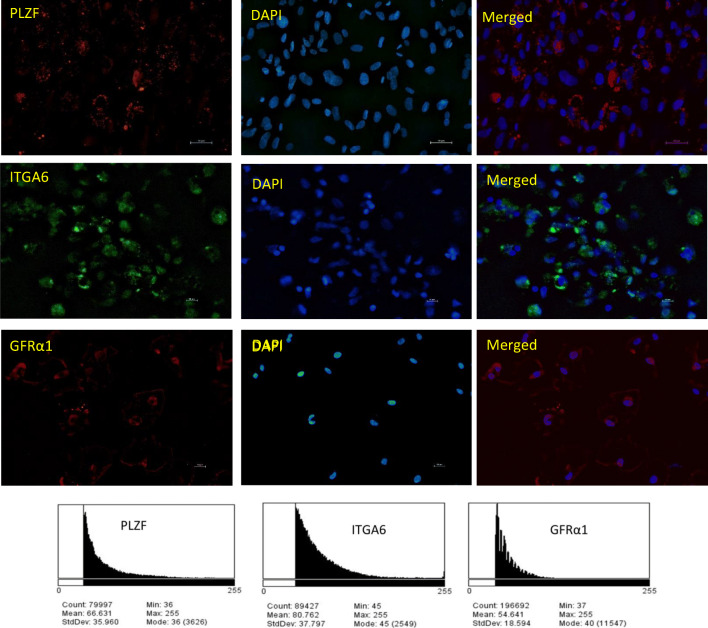

During long-term culture, there was a cellular colonization up to passage 4 in laminin-coated cultured cells. However, the cell proliferation came to standstill and SSCs could not be subcultured and propagated. During subculturing, the cultured cells expressed the stemness markers such as PLZF, GFRα1, and ITGA6. The mean percentage intensity of markers, PLZF, GFRα1, and ITGA6 after immunofluorescence staining in the cultured cells were 66.63, 54.5, and 80.76, respectively (Fig. 7. The IgG control for the immunofluorescence staining is presented in supplementary Fig. 2). The expression of CDH1, UCHL1, and GFRα1 genes were significantly (p < 0.05) lowered in passage 4 when compared with passage 3. However, there was no significant difference in the expression level of PLZF and ITGA6 between passage 3 and passage 4. The expression of differentiating marker such as cKIT were significantly downregulated while pan germ cell marker VASA significantly upregulated in passage 4 when compared with passage 3 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Immunocytochemistry of the SSC markers namely, PLZF, ITGA6, and GFR α1 localized in the cultured spermatogonial stem cells and the corresponding mean intensity were 54.5% (GFRα1), 66.63% (PLZF), and 80.76% (ITGA6)

Fig. 8.

Stemness and differentiating gene expression in the cultured cells during long term maintenance in vitro (Passage 3 (P3): 28 days culture and Passage 4 (P4): 36-day culture). Stemness marker expression (UCHL1, GFRα1, and CDH1). Differentiating marker expression (cKIT, and VASA). Stemness marker genes such as UCHL1, GFRα1, and CDH1 were significantly reduced and cKIT and VASA are significantly increased from passage 3 to passage 4. PLZF was undetected in the P3 and P4

Discussion

The present study documented successful purification of SSCs from the ovine testis and identified the growth factor requirement for in vitro culture of SSCs.

The relative number of SSCs obtained in the initial testicular cell isolate is very less compared with the total testicular cells in the isolate. Hence, an ideal method for purification of SSCs by eliminating other testicular cells are crucial for the subsequent contamination-free purified putative SSC cell culture [30–35]. Since the Ficoll protocol was less expensive and yielded high recovery rate with sufficient purity [36], in the present study, Ficoll density gradient separation is employed as an initial enrichment step to eliminate the cells of varying density and shape present in the mixed testicular cells isolates. In this step, 12% fraction provided a better recovery rate as compared with the cells in 10% Ficoll fraction [27]. Subsequently, the Ficoll enriched fraction was subjected to the second purification by plating on laminin in combination with BSA [6] to increase the purity of putative SSCs. The study revealed that combining the Ficoll density gradient with laminin plating yielded the highest purity of putative SSCs (61.7 vs 35.1%) as compared with single purification with more than 60% viability.

Differential plating with extracellular matrix substrates has been used to enrich putative SSCs with varied success rates in livestock including sheep [6, 36–38]. The in vitro SSC culture were carried out successfully with various levels of purified SSCs, 26% [39] and 91% [11] in rodents, 70–73% [40, 41] in porcine, 72% in bovine [42], and 83% in goat [43]. The variation in the purity of the SSC obtained in the present study as compared to previous studies may be attributed to the developmental stage of the testes used for isolation, differences in enrichment protocol (single or double) employed and markers used for validation [13].

In the present study, the individual effects of different doses of growth factors on the proliferation and stemness during in vitro were assessed. The stem cell–specific media, StemPro-34 reported to be more effective than DMEM or Minimum Essential Media α (MEMα) in humans [44] and ruminants [45] was chosen as the base media for ovine SSc culture.

In rodents, different growth factors, GDNF [23, 46], EGF [47], and IGF1 [31] either individually or in different combinations [48–51] were used in short- and long-term SSC cultures. As the culture system is species-specific [34, 52] and knowledge gap exists regarding the growth factor required for the maintenance and proliferation of SSCs in the culture media of domestic animals [16]. In ovine SSC, within 7 days of culture, the colony formed and attained 60–80% confluency. The cytoplasmic extension started forming on the second day and putative SSC colonies were formed on fourth day of the culture. Similar colony morphology was reported in bovine [52] and porcine [7] SSCs. On day 7, cells were observed to be in different phases of growth and stages of mitosis as reported earlier [53].

The growth factors, EGF at 15 and 20 ng/ml, GDNF at 40 ng/ml, and IGF1 at 100 ng/ml outperformed other doses in terms of proliferation rate and maintenance of stemness in vitro. The dose of GDNF used in SSC culture of different species ranged from 1 to 100 ng/ml in various studies [42, 54, 55]. The present study revealed that GDNF at 40 ng/ml was the most effective dose for the proliferation of SSCs with the maintenance of stemness in vitro than EGF and IGF1. The culture media containing GDNF at 40 ng/ml also maintained stemness up to 36 days (4 passages).

The expression of stemness marker genes such as CDH1, UCHL1, GFRα1, PLZF, and ITGA6 revealed the stemness capability of the cultured putative SSCs. The reduced expression of stemness marker genes (UCHL1, GFRα1, and CDH1) along with upregulation of pan germ cell marker (VASA) during the fourth passage suggest that culture media with GDNF at 40 ng/ml used in the present study can maintain stemness and proliferation for 36 days in ovine species. After 36 days of culture, the putative SSC proliferation slowed down and increased cellular senescence. Further, studies are needed to optimize the culture conditions for sustaining long-term ovine SSC stemness in vitro.

The earlier study in ovine SSC culture with GDNF 15 ng/ml supported SSC proliferation for 14 days; however, stemness was not assessed using the SSC marker [26]. The GDNF in different doses added to SSC culture in different species, cattle at 40 ng/ml [56], buffalo 50 ng/ml [57], canine 20 ng/ml [58], and porcine 10 ng/ml [41, 54] were found optimal for proliferation and stemness of the SSCs. The variations in dose-response can be attributed to the species-specific requirement for the proliferation of SSCs. GDNF binds to GFRα1 receptor [21] and acts through MAP kinase MAPK1/3 (ERK1/2) pathway resulting in phosphorylation and activation of transcription factors such as Creb-1, Atf-1, and Crem-1 [23]. Such transcription factors favor G1/S transition [59] resulting in improved proliferation and stemness of SSCs.

The EGF at 15 and 20 ng/ml exhibited comparable proliferation and stemness in vitro as detected by the putative stem cell marker PLZF, GFRα1, and ITGA6. Various doses of EGF ranging from 0.1 to 20 ng/ml as alone or in combination with other factors have been tried for the SSC culture of different species and the optimal dose reported for EGF is 20 ng/ml in bovine [56], caprine [60], and canine [61] and is in agreement with our present findings. In contrast, a study in bovine reported that EGF at 20 ng/ml was not found suitable for the culture of SSCs as it enhanced the proliferation of somatic cells [35]. As observed in this study, the EGF supplemented to the bovine culture media had a lesser proliferation rate as compared with GDNF [42]. EGF-mediated positive effect on proliferation and stemness in the present study could be due to activation of MAPK cascade or/and PI3K pathway by the EGF. These pathways might enhance the expressions of stem cell factor (SCF), immunoglobulin-like domain-containing neuregulin1 (Ig-NRG1), and ErbB4 in SSCs.

Among the IGF1 doses, IGF1 at 100 ng/ml provided the maximum SSCs proliferation. SSCs were cultured by incorporating IGF1 to the medium ranging from 1 to 100 ng/ml [32, 41, 62, 63]. In bovine, the culture media supplemented with IGF1 (100 ng/ml) improved the proliferation and post-freezing viability rate of SSCs [32]. IGF1 enhances the stem cell activity and colony formation in a dose-dependent manner [62] and modulates the pathways essential for the progression of spermatogenesis [64]. IGF1 acts through PI3K/Akt signaling to regulate transcription factor, Oct-4, for the maintenance of germ cell stemness [62]. IGF1 also regulates the progression of cell division from the G2/M phase [59] and might have favored the mitotic division of the cultured SSCs in the present study.

The identification of SSC markers is critical for the enrichment and in vitro culture of SSCs [32]. Even though numerous studies have been carried out to explore SSC markers [8], the appropriate marker to assess SSCs is still lacking, especially in the livestock [1]. The selection of markers for identification of putative SSCs is important. Hence, in the present study, a battery of markers for identification of putative SSCs namely PLZF, ITGA6, GFRα1, UCHL1, and CDH1 have been used to assess the stemness of cultured cells. PLZF has been employed as an SSC marker in various species including ovine [1]. ITGA6 and GFRα1 have been identified as a marker in bovine, porcine, caprine, and rodents [30, 31, 43, 55]. CDH1 has been used as an SSC marker in rodents [65] and livestock including ovine species (Zhang et al., 2014). UCHL1 was used as a marker of gonocytes and spermatogonia in large animals such as cattle, buffalo, goat, and pig [66]. The present study suggests that these markers could also be used for assessing the stemness in ovine SSCs.

Conclusion

The double enrichment method, employing Ficoll density gradient separation and differential plating using laminin in combination with BSA improved ovine SSC enrichment efficiency. Though EGF at 15 and 20 ng/ml and IGF1 at 100 and 150 ng/ml enhanced the proliferation of ovine SSCs, GDNF at 40 ng/ml is the best for the proliferation and stemness maintenance of ovine SSCs in vitro for 36 days. These findings could pave way for the successful establishment of livestock SSC technology and its application in the near future.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 9662 kb)

(DOCX 23 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Director, ICAR-National Institute of Animal Nutrition and Physiology, Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Ministry of Agriculture, Govt. of India, Bengaluru, India for providing the necessary facilities to undertake the work. The research work is supported by the institute funded project at ICAR-National Institute of Animal Nutrition and Physiology, Bengaluru, India, and DST-SERB, India. Dr. S. Selvaraju is supported by ICAR-National Fellow Project, ICAR, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India. We thank Dr. Raghavendra B S, DBT-RA for the technical help in conducting qPCR experiments. We also sincerely acknowledge Dr. J. P Ravindra, Former Head, Animal Physiology Division, ICAR-NIANP for the technical contribution.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Qu R, He Y, Tian X, Zeng W. Spermatogonial stem cells from domestic animals: progress and prospects. Reproduction. 2014;147(3):R65–R74. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinster RL, Nagano M. Spermatogonial stem cell transplantation, cryopreservation and culture. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9(4):401–409. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodyear S, Brinster R. Culture and expansion of primary undifferentiated spermatogonial stem cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2017;2017(4):pdb-rot094193. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot094193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oatley JM, Brinster RL. Regulation of spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal in mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:263–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fayomi AP, Peters K, Sukhwani M, Valli-Pulaski H, Shetty G, Meistrich ML, Houser L, Robertson N, Roberts V, Ramsey C, Hanna C. Autologous grafting of cryopreserved prepubertal rhesus testis produces sperm and offspring. AAAS. 2019;363(6433):1314–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.aav2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binsila KB, Selvaraju S, Ghosh SK, Parthipan S, Archana SS, Arangasamy A, Prasad JK, Bhatta R, Ravindra JP. Isolation and enrichment of putative spermatogonial stem cells from ram (Ovis aries) testis. Anim Reprod Sci. 2018;196:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2018.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Chen T, Zhang Y, Li B, Xu Q, Song C. Isolation and culture of pig spermatogonial stem cells and their in vitro differentiation into neuron-like cells and adipocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(11):26333–26346. doi: 10.3390/ijms161125958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li CH, Yan LZ, Ban WZ, Tu Q, Wu Y, Wang L, Bi R, Ji S, Ma YH, Nie WH, Lv LB. Long-term propagation of tree shrew spermatogonial stem cells in culture and successful generation of transgenic offspring. Cell Res. 2017;27(2):241–252. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aponte PM, Van Bragt MP, De Rooij DG, Van Pelt AM. Spermatogonial stem cells: characteristics and experimental possibilities. Apmis. 2005;113(11–12):727–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tagelenbosch RA, de Rooij DG. A quantitative study of spermatogonial multiplication and stem cell renewal in the C3H/101 F1 hybrid mouse. Mutat Res. 1993;290(2):193–200. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90159-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamra FK, Chapman KM, Nguyen DM, Williams-Stephens AA, Hammer RE, Garbers DL. Self renewal, expansion, and transfection of rat spermatogonial stem cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(48):17430–17435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508780102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goel S, Reddy N, Mandal S, Fujihara M, Kim SM, Imai H. Spermatogonia-specific proteins expressed in prepubertal buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) testis and their utilization for isolation and in vitro cultivation of spermatogonia. Theriogenology. 2010;74(7):1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiptanavattana N, Techakumphu M, Tharasanit T. Simplified isolation and enrichment of spermatogonial stem-like cells from pubertal domestic cats (Felis catus). J Vet Med Sci. 2015:15–0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Feng W, Chen S, Do D, Liu Q, Deng Y, Lei X, Luo C, Huang B, Shi D. Isolation and identification of prepubertal buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) spermatogonial stem cells. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2016;29(10):1407. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill JR, Dobrinski I. Male germ cell transplantation in livestock. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2005;18(2):13–18. doi: 10.1071/rd05123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahare MG, Imai H. Recent advances of in vitro culture systems for spermatogonial stem cells in mammals. Reprod Med Biol. 2018;17(2):134–142. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma A, Lagah SV, Nagoorvali D, Kumar BB, Singh MK, Singla SK, Manik RS, Palta P, Chauhan MS. Supplementation of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, fibroblast growth factor 2, and epidermal growth factor promotes self-renewal of putative buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) spermatogonial stem cells by upregulating the expression of miR-20b, miR-21, and miR-106a. Cell Rep. 2019;21(1):11–17. doi: 10.1089/cell.2018.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Miki H, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Toyokuni S, Ogura A, Shinohara T. Long-term culture of mouse male germline stem cells under serum-or feeder-free conditions. Biol Reprod. 2005;72(4):985–991. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.036400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo YC, Au HK, Hsu JL, Wang HF, Lee CJ, Peng SW, Lai SC, Wu YC, Ho HN, Huang YH. IGF-1R promotes symmetric self-renewal and migration of alkaline phosphatase+ germ stem cells through HIF-2α-OCT4/CXCR4 loop under hypoxia. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;10(2):524–537. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim JJ, Sung SY, Kim HJ, Song SH, Hong JY, Yoon TK, Kim JK, Kim KS, Lee DR. Long-term proliferation and characterization of human spermatogonial stem cells obtained from obstructive and non-obstructive azoospermia under exogenous feeder-free culture conditions. Cell Prolif. 2010;43(4):405–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takashima S, Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Tanaka T, Morimoto H, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Jijiwa M, Takahashi M, Ogura A, Shinohara T. Functional differences between GDNF-dependent and FGF2-dependent mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(3):489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parekh P, Garcia TX, Hofmann MC. Regulation of GDNF expression in Sertoli cells. Reproduction. 2019;157(3):R95–R107. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann MC. Gdnf signaling pathways within the mammalian spermatogonial stem cell niche. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;288(1–2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabri A, Ziaee AA, Ostad SN, Alimoghadam K, Ghahremani MH. Crosstalk of EGF-directed MAPK signalling pathways and its potential role on EGF-induced cell proliferation and COX-2 expression in human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2011;29(1):64–70. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu M, Wei Y, Xu K, Liu S, Ma L, Pei Y, Hu Y, Liu Z, Zhang X, Wang B, Mu Y. EGFR deficiency leads to impaired self-renewal and pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells. Peer J. 2019;7:e6314. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paul RK, Bahire SV, Davendra K. Isolation and biochemical characterization of ovine spermatogonial stem cells. Indian J Small Ruminants. 2017;23(2):186–0189. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Binsila BK, Selvaraju S, Ghosh SK, Prasad JK, Ramya L, Ravindra JP, Bhatta R. Purification of spermatogonial stem cells from ram testicular isolate using ficoll density gradient separation. Indian J Anim Reprod. 2019;40(1):7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parthipan S, Selvaraju S, Somashekar L, Kolte AP, Arangasamy A, Ravindra JP. Spermatozoa input concentrations and RNA isolation methods on RNA yield and quality in bull (Bos taurus) Anal Biochem. 2015;482:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giassetti MI, Goissis MD, Moreira PV, de Barros FR, Assumpção ME, Visintin JA. Effect of age on expression of spermatogonial markers in bovine testis and isolated cells. Anim Reprod Sci. 2016;170:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinohara T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. β1-and α6-integrin are surface markers on mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(10):5504–5509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panahi BQ, Tajik P, Movahedin M, Moghaddam G, Geranmayeh MH. Study of insulin-like growth factor 1 effects on bovine type A spermatogonia proliferation and viability. Turk J Vet Anim Sci. 2014;38(6):693–698. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng Y, He Y, An J, Qin J, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Tian X, Zeng W. THY1 is a surface marker of porcine gonocytes. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2014;26(4):533–539. doi: 10.1071/RD13075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofmann MC, Braydich-Stolle L, Dettin L, Johnson E, Dym M. Immortalization of mouse germ line stem cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23(2):200–210. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2003-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahare M, Kim SM, Otomo A, Komatsu K, Minami N, Yamada M, Imai H. Factors supporting long-term culture of bovine male germ cells. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2016;28(12):2039–2050. doi: 10.1071/RD15003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herrid M, Davey RJ, Hutton K, Colditz IG, Hill JR. A comparison of methods for preparing enriched populations of bovine spermatogonia. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21(3):393–399. doi: 10.1071/rd08129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borjigin U, Davey R, Hutton K, Herrid M. Expression of promyelocytic leukaemia zinc-finger in ovine testis and its application in evaluating the enrichment efficiency of differential plating. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2010;22(5):733–742. doi: 10.1071/RD09237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu H, Liu C, Li M, Sun J, Song W, Hua J. Optimization of the conditions of isolation and culture of dairy goat male germline stem cells (mGSC) Anim Reprod Sci. 2013;137(1–2):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gat I, Maghen L, Filice M, Kenigsberg S, Wyse B, Zohni K, Saraz P, Fisher AG, Librach C. Initial germ cell to somatic cell ratio impacts the efficiency of SSC expansion in vitro. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2018;64(1):39–50. doi: 10.1080/19396368.2017.1406013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo J, Megee S, Rathi R, Dobrinski I. Protein gene product 9.5 is a spermatogonia-specific marker in the pig testis: application to enrichment and culture of porcine spermatogonia. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73(12):1531–1540. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang P, Chen X, Zheng Y, Zhu J, Qin Y, Lv Y, Zeng W. Long-term propagation of porcine undifferentiated spermatogonia. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26(15):1121–1131. doi: 10.1089/scd.2017.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aponte PM, Soda T, Van De Kant HJ, de Rooij DG. Basic features of bovine spermatogonial culture and effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. Theriogenology. 2006;65(9):1828–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pramod RK, Mitra A. In vitro culture and characterization of spermatogonial stem cells on Sertoli cell feeder layer in goat (Capra hircus) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31(8):993–1001. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0277-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piravar Z, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Sadeghi MR, Mohazzab A, Eidi A, Akhondi MM. In vitro culture of human testicular stem cells on feeder-free condition. J Reprod Infertil. 2013;14(1):17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oatley MJ, Kaucher AV, Yang QE, Waqas MS, Oatley JM. Conditions for long-term culture of cattle undifferentiated spermatogonia. Biol Reprod. 2016;95(1):14–11. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.116.139832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu RJ, Xu SF. Mechanism of epidermal growth factor effects on spermatogonial stem cells. Life Sci Res. 2010;14(1):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oatley JM, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor regulation of genes essential for self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells is dependent on Src family kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(35):25842–25851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703474200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bahadorani M, Hosseini SM, Abedi P, Abbasi H, Nasr-Esfahani MH. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in combination with insulin-like growth factor 1 and basic fibroblast growth factor promote in vitro culture of goat spermatogonial stem cells. Growth Factors. 2015;33(3):181–191. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2015.1062758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heidari B, Rahmati-Ahmadabadi M, Akhondi MM, Zarnani AH, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Shirazi A, Naderi MM, Behzadi B. Isolation, identification, and culture of goat spermatogonial stem cells using c-kit and PGP9. 5 markers. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(10):1029–1038. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9828-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Helsel AR, Oatley MJ, Oatley JM. Glycolysis-optimized conditions enhance maintenance of regenerative integrity in mouse spermatogonial stem cells during long-term culture. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;8(5):1430–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kadam PH, Kala S, Agrawal H, Singh KP, Singh MK, Chauhan MS, Palta P, Singla SK, Manik RS. Effects of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, fibroblast growth factor 2 and epidermal growth factor on proliferation and the expression of some genes in buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) spermatogonial cells. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2013;25(8):1149–1157. doi: 10.1071/RD12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aponte PM. Spermatogonial stem cells: current biotechnological advances in reproduction and regenerative medicine. World J Stem Cells. 2015;7(4):669–680. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i4.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee J, Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Morimoto H, Kazuki Y, Takashima S, Oshimura M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. Genetic reconstruction of mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal in vitro by Ras-cyclin D2 activation. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(1):76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han SY, Gupta MK, Uhm SJ, Lee HT. Isolation and in vitro culture of pig spermatogonial stem cell. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2009;22(2):187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee WY, Park HJ, Lee R, Lee KH, Kim YH, Ryu BY, Kim NH, Kim JH, Kim JH, Moon SH, Park JK. Establishment and in vitro culture of porcine spermatogonial germ cells in low temperature culture conditions. Stem Cell Res. 2013;11(3):1234–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aponte PM, Soda T, Teerds KJ, Mizrak SC, van de Kant HJ, de Rooij DG. Propagation of bovine spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. Reproduction. 2008;136(5):543–557. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kala S, Kaushik R, Singh KP, Kadam PH, Singh MK, Manik RS, Singla SK, Palta P, Chauhan MS. In vitro culture and morphological characterization of prepubertal buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) putative spermatogonial stem cell. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(12):1335–1342. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9883-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim Y, Turner D, Nelson J, Dobrinski I, McEntee M, Travis AJ. Production of donor-derived sperm after spermatogonial stem cell transplantation in the dog. Reproduction. 2008;136(6):823–831. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang S, Wang X, Wu Y, Han C. IGF-1R signaling is essential for the proliferation of cultured mouse spermatogonial stem cells by promoting the G2/M progression of the cell cycle. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;24(4):471–483. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma V, Saini S, Aneja B, Kumar A, Thakur A, Bajwa KK, Kumar S, Mohanty AK, Malakar D. 180 increasing GfrA1-positive Spermatogonial stem cell population of goat. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2018;30(1):230. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee KH, Lee WY, Kim DH, Lee SH, Do JT, Park C, Kim JH, Choi YS, Song H. Vitrified canine testicular cells allow the formation of spermatogonial stem cells and seminiferous tubules following their xenotransplantation into nude mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21919. doi: 10.1038/srep21919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang YH, Chin CC, Ho HN, Chou CK, Shen CN, Kuo HC, Wu TJ, Wu YC, Hung YC, Chang CC, Ling TY. Pluripotency of mouse spermatogonial stem cells maintained by IGF-1-dependent pathway. FASEB J. 2009;23(7):2076–2087. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeong D, McLean DJ, Griswold MD. Long-term culture and transplantation of murine testicular germ cells. J Androl. 2003;24(5):661–669. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yao J, Zuo H, Gao J, Wang M, Wang D, Li X. The effects of IGF-1 on mouse spermatogenesis using an organ culture method. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;491(3):840–847. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tokuda M, Kadokawa Y, Kurahashi H, Marunouchi T. CDH1 is a specific marker for undifferentiated spermatogonia in mouse testes. Biol Reprod. 2007;76(1):130–141. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Komeya M, Ogawa T. Spermatogonial stem cells: Progress and prospects. Asian J Androl. 2015;17(5):771. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.154995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 9662 kb)

(DOCX 23 kb)