Abstract

Aim of present study is to quantify essential (Ca, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Na, P, Se and Zn) and non-essential/toxic (Al, As, Ba, Cd, Ni, Pb and Ti) elements of 100% fruit juices (orange, apple, pomegranate and grape) and fruit nectars (orange, peach, apricot and cherry and the determination of non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks. For this purpose, inductively coupled plasma-optical emmision spectroscopy was used to find out element content of samples after microwave digestion process. Essential element contents of 100% fruit juices and nectars were determined as max. 1350 mg/L (K, in 100% orange juice) and min. 0.007 mg/L (Cr, in 100% grape, cherry and apricot nectar and Cu, Mo, in 100% apple juice). Furthermore, the daily intake percentages of essential elements were calculated for 200 mL fruit juice consumption. Target hazard quotients, hazard indexes (HI) and target carcinogenic risks (TR) of non-essential, trace and ultra trace elements were also calculated and risk analysis were conducted. According to the results, the HI and TR of samples were founded as less than 1 and 1 × 10−4, respectively. All samples evaluated as in the low risk group.

Keywords: Food analysis, Fruit juice, Essential elements, Toxic elements, THQ, HI

Introduction

Fruit juices are widely consumed beverages all over the world by different age groups and consumption of them has been intensifying day by day depending on the increasing knowledge of their nutritional abilities, flavour, taste and beneficial health effects (Madeja et al. 2014).

They are generally divided into two segments of 100% fruit juices and fruit nectars. 100% fruit juices are restricted to beverages that are pure filtered juice. Various fruits are used to make juice such as orange, apple, grape, pomegranate etc. Nectars are prepared from diluted fruit juices and pulp (to a degree limited by regulations) and they contain additives including natural and artificial sweeteners, and preservatives. The fruit juice content in nectar can vary between 25 and 99% (FAO 2017; Demir et al. 2015).

The investigation of the contents of fruit juices is an important consideration for conscious consumption. Fruit juices contain carbohydrates, proteins, flavonoids various kinds of antioxidants, vitamins and various elements that are necessary to our body (Dehelean and Magdas 2013; Bartoszek 2016).

When elements are assessed for health effect they can be subdivided into two groups of essential and non-essential/toxic elements. Essential elements play important role in the human life but they may be toxic at higher consumption ratio. On the other hand, non-essential elements show toxic effects at low exposure levels and cause health problems (Kamunda et al. 2016).

Elements also can be classified into three groups (macrominerals, trace elements, ultra-trace elements) according to required by adults. Macro elements, which include Calcium (Ca), Potassium (K), Magnesium (Mg), Sodium (Na) and Phosphorus (P) elements are defined as elements required by adults in amounts higher than 100 mg/day. For adults, trace element [such as Iron (Fe), Copper (Cu), Zinc(Zn)] requirements are between 1 and 100 mg/day while ultra-trace [such as Chromium (Cr), Cadmium (Cd), Cobalt (Co), Manganese (Mn), Arsenic (As), Molybdenum (Mo) and Lead (Pb)] elements requirements are less than 1 mg/day (Dutta and Mukta 2012). Trace and ultra trace essential elements are important to vital activity as long as they do not exceed recommended daily intake otherwise they can lead to damaging effects (Hariri et al. 2015). The determination of the elemental composition of fruit juices is very important in terms of consumer safety and protection. Beside the provided essential elements for human body by fruit juice consumption, there is a possibility of toxic elements input which shows disruption effect of the consumer’s biological processes (Todorovska and Popovski 2012).

Several factors play role in the toxic element contamination of juices such as excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides, raw fruit origin, storage condition, processing technologies, endogenous or exogenous formation and polluted water (sewage sludge, irrigation with residual water etc.) (Pramod and Devendra 2014).

Toxic element exposure poses various negative effect for human health. Although each toxic element exhibits unique toxicology, there are some common symptom such as oxidative damage, disruption in cellular and enzymatic mechanisms and adduct formation with DNA or protein (Keil et al. 2011). Toxic elements show adverse effects even at very low concentration, in addition to this, the ranges between beneficial and toxic level of essential elements are usually small (Pramod and Devendra 2014).

There are various studies about element contents and health risk assessment of fruit juices. Previously published data of essential element concentrations are grouped and shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Published studies about essential and non-essential element concentrations of fruit juices in literature

| Essential elements (mg/L) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Co | Cr | Cu | Fe | K | Mg | Mn | Na | P | Zn | |

| Org. | 0.0079* | 0.0059* | 0.5* | 0.361* | 0.0209* | 0.895* | |||||

| 0.245 | 1.177 | ||||||||||

| 52 | 0.13 | 4.9 | 825 | 29 | 0.2 | 88 | 52 | 4.7 | |||

| 1082 | 0.009 | 0.198 | 0.549 | 71.2 | 0.316 | 235 | 0.235 | ||||

| 43.3 | 0.0082* | 0.204* | 196. | 32.8 | 0.0641* | 15.6 | 0.189* | ||||

| App. | 0.008* | 0.0063* | 0.317* | 0.325* | 0.0234* | 0.524* | |||||

| 0.283 | 0.55 | ||||||||||

| 83.4 | 0.022 | 0.083 | 1.79 | 44.3 | 0.406 | 75 | 0.21 | ||||

| 72.07 | 0.0002* | 0.0041* | 0.0991* | 415.4 | 50.42 | 0.214* | 364 | 0.1802* | |||

| Chr. | 42.8 | 0.021 | 0.246 | 0.284 | 5.15 | 157 | 39.9 | 0.272 | 75.8 | 0.158 | |

| 54.7 | 9.11 | 264 | 91 | 68.4 | 29 | ||||||

| Apr. | 24.8 | 0.007* | 0.0554* | 0.139* | 301.8 | 30.2 | 0.245* | 100.03 | 0.446* | ||

| 70 | 0.73 | 3.8 | 1140 | 50 | 30 | 0.9 | |||||

| 102.05 | 10.25 | 1046 | 150.9 | 68.3 | 63 | ||||||

| Pea. | 26.6 | 0.0076* | 0.0396* | 0.4038* | 257 | 40.33 | 0.23* | 129 | 0.569* | ||

| 38.6 | 0.017 | 0.377 | 1.36 | 7.37 | 185 | 24.6 | 0.346 | 50.58 | 0.536 | ||

| 42.9 | 10.29 | 679 | 110.7 | 50.51 | 48.08 | ||||||

| Grp. | 123 | 0.025 | 1.68 | 2.75 | 48.8 | 0.886 | 1360 | 0.351 | |||

| 49.4 | 0.022 | 0.33 | 0.321 | 5.3 | 144 | 32.2 | 0.284 | 88.2 | 0.322 | ||

| Pmg. | 2* | 5* | 2* | 1350* | 610* | ||||||

| 107.53 | 0.1 | 1.81 | 1283 | 67.2 | 0.096 | 96.02 | 76.5 | 0.04 | |||

| 0.42 | 207 | 13.8 | 133 | 23.4 | |||||||

| Non-essential elements (mg/L) | Refs. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | As | Ba | Cd | Ni | Pb | Ti | ||

| Org. | 0.0057* | Farid and Enani (2010) | ||||||

| 0.01 | 0.095 | Krejpcio et al. (2005) | ||||||

| 3.1 | 0.1 | 0.54 | Bao et al. (1999) | |||||

| 0.03 | 0.239 | 0.01 | 0.063 | Madeja et al. (2014) | ||||

| 0.0001* | 0.057* | 0.010* | Dehelean and Magdas (2013) | |||||

| App. | 0.0062* | Farid and Enani (2010) | ||||||

| 0.016 | 0.13 | Krejpcio et al. (2005) | ||||||

| 0.832 | 0.133 | 0.069 | 0.67 | Madeja et al. (2014) | ||||

| 0.0036* | 0.0001* | 0.0189* | 0.0248* | Dehelean and Magdas (2013) | ||||

| Chr. | 55.2 | 1.045 | 0.0571 | 0.0153 | Velimirović et al. (2013) | |||

| Demir and Acar (1995) | ||||||||

| Apr. | 0.0015* | 0.0004* | 0.0350* | 0.0053 | Dehelean and Magdas (2013) | |||

| Barners (2017) | ||||||||

| Demir and Acar (1995) | ||||||||

| Pea. | 0.0015* | 0.0005* | 0.0261* | 0.0059* | Dehelean and Magdas (2013) | |||

| 14.6 | 0.373 | 0.0471 | 0.331 | Velimirović et al. (2013) | ||||

| Demir and Acar (1995) | ||||||||

| Grp. | 0.48 | 0.049 | 0.055 | 0.106 | Madeja et al. (2014) | |||

| 86.1 | 1.36 | 0.0722 | 0.0413 | Velimirović et al. (2013) | ||||

| Pmg. | Akhtar et al. (2013) | |||||||

| 0.04 | 0.003 | Bayızıt (2010) | ||||||

| Dehelean et al. (2016) | ||||||||

Org orange, App apple, Chr cherry, Apr apricot, Pea peach, Grp grape, Pmg pomegranate

*Original data were converted to mg/L

ICP-OES is an elemental analysis technique, which uses the emission spectra of a sample to determine and identify the trace elements. Sample is subjected to enough high temperatures for causing excitation and/or ionization of the sample of atoms in this technique and it has high sensitivity for detecting the major trace elements (Demir et al. 2015).

The multielement capability, wide linear dynamic range, and high sample throughput properties of ICP-OES provides important advantages in comparison to other spectral techniques. Radial viewing of a plasma is possible in ICP-OES methods and it offers higher upper limit of linearity, reduced easily ionizable element effects, lower physical interferences, and fewer spectral interferences (Barners 2017). This method has additional advantages over the other techniques in terms of detection limits as well as speed of analysis (Vallapragada et al. 2011).

Within the scope of this study essential (Ca, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Na, P, Se and Zn) and non-essential/toxic (Al, As, Ba, Cd, Ni, Pb and Ti) element concentration of 100% fruit juices (orange, apple, pomegranate and grape) and fruit nectar (orange, peach, apricot and cherry) were determined with using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES).

This study also presents target hazard risk and cancer risk assessment investigating of fruit juices. It is researched whether fruit juices consumption is likely a significant source of non-essential and trace element exposure and whether this exposure poses an increased risk to human health.

Materials and methods

For 1 day before the digestion process, 100% fruit juices (apple, orange, pomegranate, grape) and nectars (orange, cherry, apricot, peach) were purchased in November 2014 from the local market in Istanbul, Turkey. The juices were stored at ambient conditions (temperature, 24 ± 5 °C; humidity, 45 ± 10%) in the original packings (1 L TetraPak packages for 100% orange, pomegranate and grape juices; 200 mL TetraPak packages for 100% apple juice, orange, cherry, apricot and peach nectars) Fruit juice samples were collected and analyzed in the 3rd month after the date of production to ensure that the analyzes were accurate and on the same conditions.

Preparation of the 100% juice and nectar samples

A digestion process was applied to samples to prepare elemental analysis. In digestion method, 5 mL of juice was digested with 10 mL of nitric acid (HNO3, 65%) (Merck chemicals (Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany), in Berghof Speed Wave microwave digestion system (Berghof Products & Instruments GmbH, Eningen, Germany). Operating conditions of the microwave digestion system were presented in previous study (Demir et al. 2015). The resulting solutions that were cooled and diluted to 25 mL with distilled water (0.07 µs cm−1), obtained from GFL 2004 water purification system (Gesellschaft fur Labortechnik, Burgwedel, Germany) were analysed by ICP-OES.

Preparation of the calibration sets and elemental analysis of the samples

External calibration technique was followed for the quantitative analysis of samples. Multi element calibration curve were prepared from 1000 mg L−1 Ca, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Mo, Mn, Na, P, Se, Zn (essential elements), Al, As, Ba, Cd, Ni, Pb, Sb, Ti (non-essential elements) mono element certified Standard solutions (VHG Labs, Single Element Standarts). All calibration solutions and calibration blank were prepared daily by appropriate stepwise dilutions with HNO3 3‰ (v/v). Linearity in terms of correlation coefficients (R2) was checked bye establishing calibration curves of all the analyte elements using a linear calibration algorithm analysis. The juice samples were diluted at various ratios between 1:5 and 1:50 to ensure compliance with the calibrated ranges. All analysis were performed in three replicates.

Perkin-Elmer Optima 2100 DV ICP-OES equipped with an AS-93 autosampler (PerkinElmer, CT, USA) was used in the experiments. Conditions in the experiment were adjusted to a power of 1.45 kW, plasma flow of 15.0 L min−1, auxiliary flow of 0.8 L min−1 and nebulizer flow of 1 L min−1.

Statistical analysis

Regression analysis was conducted using the Statistical 8.0 computer programme (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA).

Three replicate samples of each fruit juice are prepared and analysed. The average values of these three samples along with the standard deviations are calculated using the Eqs. (1) and (2):

| 1 |

| 2 |

where is the average value of the sample, xi is the average value of the sample at the parallel i, n is the, number of parallel samples and s is the standard deviation. The concentration (mg/L) results are given in the confidence level (P) between 90 and 99, respectively.

Quality assurance and quality control

Analytical methods are characterized by some selected validation parameters such as limits of detection (LOD) and limits of quantification (LOQ) and relative standard deviations. The sample or standard solution is measured by undertaking replicate measurements to make sure the results are accurate.

In this experiment, the capability of the method was estimated through the determination of the detection limits of every element studied. LOD and LOQ values, were calculated with three and ten times the standard deviation of the ten individually prepared blank solutions (Khan et al. 2013). Precision was evaluated in terms of percent coefficients of variance (CV %) which in turn was obtained by measuring the relative Standard deviation of ten repeated replicates of one sample. Relative standard deviations of analytical results which below 15% shows that the precision of the method is satisfactory (Madeja and Welna 2013).

Daily essential element intake percentages

Essential element intake percentages for humans between the ages of 31–50 in 200 mL of 100% fruit juices (apple, orange, pomegranate, grape) and nectars (orange, cherry, apricot, peach) were calculated with Eq. (3) and Eq. (4).

| 3 |

| 4 |

where ‘m’ is the element contents (mg) of 200 mL of apple juice, “C” (mg/L) is the element concentration, ‘DRI’ is daily recommended dietary reference intakes, which the values are given in Gorgulu et al. (2016), and ‘DMI’ is daily main intakes.

Risk assessment

Exposure of toxic chemical could occur via three main pathways including direct ingestion, inhalation and dermal absorption (Li and Zhang 2010).

Trace and non-essential elements are intook in the body by investigation in fruit juice consumption. For this reason, risk analysis evaluations were calculated only for oral consumption.

Non-carcinogenic risk

The target hazard quotients (THQs) is a term used to describe health risks of a single chemical while the risk of exposure to two or more chemicals are described as hazard index (HI) term.THQ and HI values can be calculated by using the following Eqs. (5) and (6) (Wu et al. 2016).

| 5 |

| 6 |

where EF is exposure frequency (365 days/year); ED is exposure duration (70 years); FIR is the rate of food consumption (mL/person/day); C is the element concentration in fruit juices (mg/L); RfD (mg/kg/day) is the oral reference dose; BW (60 kg) is the average body weight and AT is the average lifetime (365 days/year × 70 years). The RfD values are 1 for Al, 1 × 10−3 for Cd, 15 × 10−1 for Cr, 4 × 10−2 for Cu, 3 × 10−4 for Co, 36 × 10−4 for Pb, 2 × 10−2 for Ni, 3 × 10−1 for Zn (Yu et al. 2015), 2 × 10−1 for Ba, 4 × 10−4 for Sb (Gorgulu et al. 2014), 3 × 10−4 for As, 7 × 10−1 for Fe, 14 × 10−2 for Mn and 5 × 10−3 for Mo (Wu et al. 2016).

If the calculated THQ values were less than 1 indicates that no obvious health risk is present. On the other hand, if the THQ values were greater than 1, there is a potential health risk for human (Wu et al. 2016).

Carcinogenic risk

Target carcinogenic risks (TR) assessment is used to evaluate of risk involved as a result of exposure to potential carcinogens. TR value can be calculated by using the following Eq. (7) (Saiful Islam et al. 2015).

| 7 |

where CSF (mg/kg/day)−1 is the cancer slope factor and the CSF values are 15x10−1 for As, 85 × 10−4 for Pb (Saiful Islam et al. 2015), 63 × 10−1 for Cd (Bamuwamye et al. 2015) and 17 × 10−1 for Ni (Bhupander and Mukherjee 2011).

The US Environmental Protection Agency considers acceptable for regulatory purposes a cancer risk in the range of 1 × 10−6 to 1 × 10−4 and assessment of cancer risk is based on these values (Kamunda et al. 2016).

Results and discussion

Validation of analytical method

Validation of analytical method in terms of limits of detection and quantification, correlation coefficients, and coefficient of variance measurements by ICP-OES was given in Table 2. R2 of the calibration curves for these elements were higher than 0.999. To investigate the stability of the detector response during instrumental analysis, a multi-element Standard solution with moderate concentration was analyzed with each batch (ten samples), and the relative standard deviation was less than 10%. The values of limits of detection and quantification ranged 0.0001–0.0063 and 0.0005–0.0209 mg/L for essential elements, 0.0003–0.002 and 0.0012–0.0069 mg/L for non-essential elements, respectively. The values of CV % were below 9% for all the analyte elements.

Table 2.

Validation of analytical method obtained using a Standard reference in terms of limits of detection and quantification, correlation coefficients, and coefficient of variance measurements by ICP-OES

| Element | Limits of detection (mg/L) | Limits of quantification (mg/L) | Correlation coefficient (R2) | Coefficient of variance (CV %) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% apple | 100% pomegranate | 100% grape | 100% Orange | Orange | Cherry | Apricot | Pecah | ||||

| Ca | 0.0063 | 0.0209 | 0.999 | 3.50 | 2.25 | 2.43 | 1.15 | 2.64 | 3.99 | 2.61 | 1.88 |

| Cr | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.999 | 1.57 | b.d.l. | 2.69 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 2.02 | 4.23 | 4.01 |

| Co | 0.0005 | 0.0016 | 0.999 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. |

| Cu | 0.0004 | 0.0013 | 0.999 | 1.57 | 3.54 | 0.73 | 2.49 | 3.62 | 3.10 | 2.99 | 1.40 |

| Fe | 0.0017 | 0.0055 | 0.999 | 5.76 | 4.84 | 3.83 | 3.19 | 3.39 | 0.61 | 3.12 | 1.93 |

| K | 0.0015 | 0.0049 | 0.999 | 2.80 | 2.74 | 1.77 | 2.46 | 1.88 | 0.79 | 3.00 | 1.49 |

| Mg | 0.0010 | 0.0035 | 0.999 | 4.04 | 3.44 | 2.66 | 1.20 | 2.78 | 4.14 | 2.67 | 1.70 |

| Mo | 0.0003 | 0.0011 | 0.999 | 5.99 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 5.54 |

| Mn | 0.0004 | 0.0013 | 0.999 | 3.86 | 3.60 | 1.64 | 1.56 | b.d.l. | 3.44 | 3.68 | 3.31 |

| Na | 0.0029 | 0.0096 | 0.999 | 3.27 | 3.05 | 2.68 | 1.67 | 2.33 | 3.89 | 3.63 | 3.52 |

| P | 0.0038 | 0.0125 | 0.999 | 4.38 | 5.87 | 0.95 | 0.40 | 3.96 | 2.89 | 3.26 | 4.77 |

| Se | 0.0036 | 0.012 | 0.999 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. |

| Zn | 0.0002 | 0.0006 | 0.999 | 5.81 | 2.24 | 1.23 | 1.06 | 3.75 | 1.79 | 2.04 | 3.01 |

| As | 0.0015 | 0.0053 | 0.999 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. |

| Al | 0.002 | 0.0069 | 0.999 | 4.09 | 5.90 | 6.67 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 6.59 | 6.53 | 5.13 |

| Ba | 0.0018 | 0.0053 | 0.999 | 6.58 | 1.31 | 2.75 | 5.31 | 6.81 | 6.44 | 5.17 | 3.87 |

| Cd | 0.0003 | 0.0012 | 0.999 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. |

| Ni | 0.0008 | 0.0028 | 0.999 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 7.70 | 8.24 |

| Pb | 0.0018 | 0.006 | 0.999 | 2.06 | 7.90 | 6.59 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 3.65 | 4.85 |

| Sb | 0.0007 | 0.0024 | 0.999 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. |

| Ti | 0.0003 | 0.0012 | 0.999 | 6.61 | b.d.l. | 8.44 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 8.61 | 5.97 |

*b.d.l: below detection limit

Instrumental analysis results

The concentrations of essential and non-essential elements in 100% fruit juices and nectars are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

The concentrations of essential and non-essential elements in 100% fruit juices and nectar

| Elements | Conc. (mg/L) | 100% apple | 100% pomegranate | 100% grape | 100% orange | Orange | Cherry | Apricot | Peach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential | Ca | 64.1 ± 0.19 | 162 ± 15.9 | 177 ± 3.7 | 120.2 ± 4.5 | 89.3 ± 0.30 | 68.8 ± 2.19 | 66.09 ± 3.95 | 53.80 ± 3.86 |

| Cr | 0.012 ± 7 × 10−4 | b.d.l. | 0.007 ± 6 × 10−4 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 0.007 ± 6 × 10−4 | 0.007 ± 6 × 10−4 | 0.010 ± 7 × 10−4 | |

| Cu | 0.007 ± 6 × 10−4 | 0.082 ± 0.005 | 0.083 ± 0.003 | 0.048 ± 0.001 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | 0.013 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.074 ± 0.001 | 0.083 ± 6 × 10−4 | |

| Fe | 0.227 ± 5 × 10−4 | 0.211 ± 6 × 10−4 | 0.343 ± 0.016 | 0.455 ± 0.007 | 0.066 ± 0.004 | 0.195 ± 0.004 | 0.894 ± 0.035 | 0.205 ± 0.014 | |

| K | 896 ± 13.9 | 941 ± 30.3 | 1080 ± 16 | 1350 ± 21 | 986 ± 19.8 | 565 ± 15.3 | 1038 ± 50.2 | 842 ± 5 | |

| Mg | 33.04 ± 0.38 | 61.7 ± 0.88 | 71.01 ± 1.22 | 73.3 ± 1.19 | 33.8 ± 1.10 | 31.4 ± 0.01 | 30.805 ± 1.096 | 27.7 ± 2.16 | |

| Mo | 0.007 ± 6 × 10−4 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 0.007 ± 6 × 10−4 | |

| Mn | 0.105 ± 0.004 | 0.013 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.087 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.029 ± 6 × 10−4 | b.d.l. | 0.015 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.047 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.090 ± 6 × 10−4 | |

| Na | 22.9 ± 0.09 | 16 ± 0.23 | 17.01 ± 0.79 | 7.7 ± 0.260 | 6.37 ± 0.026 | 23 ± 0.27 | 3.074 ± 0.159 | 4.760 ± 0.019 | |

| P | 36.7 ± 0.07 | 90.42 ± 1.98 | 100.9 ± 1.6 | 89.3 ± 0.23 | 51.30 ± 2.60 | 48.5 ± 0.73 | 46.6 ± 0.72 | 48.1 ± 2.36 | |

| Zn | 0.015 ± 6 × 10−4 | 0.080 ± 0.007 | 0.094 ± 0.002 | 0.049 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.006 ± 5 × 10−4 | 0.081 ± 0.004 | 0.046 ± 0.002 | |

| Non-essential | Al | 0.037 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.404 ± 0.038 | 0.043 ± 2 × 10−4 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 0.023 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.715 ± 0.03 | 0.830 ± 0.079 |

| Ba | 0.036 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.075 ± 2 × 10−4 | 0.015 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.028 ± 0.002 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.042 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.028 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.012 ± 7 × 10−4 | |

| Ni | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 0.018 ± 7 × 10−4 | 0.003 ± 2 × 10−4 | |

| Pb | 0.058 ± 0.004 | 0.055 ± 0.005 | 0.032 ± 2 × 10−4 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 0.121 ± 0.01 | 0.135 ± 0.006 | |

| Ti | 0.010 ± 2 × 10−4 | b.d.l. | 0.004 ± 2 × 10−4 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 0.024 ± 0.001 | 0.042 ± 0.003 |

*b.d.l: below detection limit

When the analysis results of the essential elements were examined, it can be seen that K, Ca, P, Mg, Na element contents are found as the major compositions, which are classified as macroelements. Fe, Mn, Zn, Cr, Cu and Mo elements contents followed to concentration value of macro-elements. The highest concentration of essential element present in all samples of fruit juices are found as K with the values between 565 and 1350 mg/L. The highest content of K belonged to 100% orange juice and the lowest K content was detected in cherry nectar. The higher K content of fruit juices may be due to addition of many potassium compounds (acesulfame K) or preservatives (E212-potassium benzoate, potassium sorbate-E201, potassium bisulfite-E228) during the production of these products as well as potassium in the contents of the fruits (Velimirović et al. 2013).

Ca is found as the second most abundant element in analyzed samples. The concentration of Ca ranged from 53.80 (peach nectar) to 177 mg/L (100% grape juice). Higher presence of calcium in fruit juices may be relevant to acidity regulators such as calcium ascorbate or calcium chloride used to prevent enzymatic browning (Dehelean et al. 2016).

Ca is followed by P element that ranged from 36.70 (100% apple juice) to 100.9 mg/L (100% grape juice). The highest content of calcium and phosphorus is found in 100% grape juice.

The level of Mg and Na in juices ranged from 27.70 (peach nectar) to 73.3 mg/L (100% orange juice) and 3.074 (apricot nectar) to 23 mg/L (cherry nectar), respectively. P, Mg and Na elements may be used for enrichment of juice and supplied from various source such as the water, the fruit or added ingredient e.g. benzoates, citrates or saccharin (Velimirović et al. 2013).

Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, Cr and Mo elements are existed at lower concentrations than macro elements in analyzed fruit juices. The highest concentrations of Fe are observed in apricot nectar (0.894 mg/L) and lowest content is detected in orange nectar (0.066 mg/L). Zn and Mn concentrations ranged from 0.006 (cherry nectar) to 0.094 mg/L (100% grape juice) and 0.013 (100% pomegranate juice) to 0.105 mg/L (100% apple juice), respectively. Mn element concentration was below the detection limit in orange nectar.

The content of other essential trace elements followed the descending order; Cu (max: 0.083 mg/L, in 100% grape juice and peach) > Cr (max: 0.012 mg/L, in 100% apple juice) > Mo (max: 0.007 mg/L, in 100% apple juice and peach nectar). Mo and Cr elements were below the detection limit in 100% pomegranate juice, 100% orange juice, orange nectar but Mo element was also found to be below the detection limit in 100% grape juice, cherry nectar, and apricot nectar. The concentration of essential trace elements of Co and Se were below the detection limit in all samples.

When the analysis results of the non-essential elements are examined, it can be seen that Al concentrations are ranged from 0.023 (cherry nectar) to 0.830 mg/L (peach nectar) and it is below the detection limit in 100% orange juices and orange nectar. Al content of water used in fruit juices process, Al-containing food additives and Al-made containers such as TetraPak and TetraBriks that made from layers of paper, plastic (polyethylene) and aluminium foil can cause the high Al content (Velimirović et al. 2013). The Ba contents are varied between 0.075 (100% pomegranate) and 0.012 mg/L (peach nectar). Ni element is only found in apricot nectar (0.018 mg/L) and peach nectar (0.003 mg/L) while it is below the detection limits in other analysed samples. The highest concentrations of Pb and Ti are measured in 100% grape juice (0.135 and 0.042 mg/L) and lowest content is detected in peach nectar (0.032 and 0.004 mg/L). Pb and Ti concentration could not be detected in 100% orange juice, orange nectar and cherry nectar. Ti content of 100% pomegranate juice is also below detected limit. The concentration of non-essential elements of As, Cd, and Sb are below the detection limit in all samples.

There were some differences in essential and non-essential elements concentrations of analysed fruit juices from published data. These differences based on element content of fruit, element content of water that used in production of juices and added ingredients. According to the literature studies on essential and non-essential element content of fruit juices; in 100% apple juice, the value of Mg (33.04 mg/L) are between the study results of Madeja and Welna (2013)) and Dehelean and Magdas (2013). The Pb value of 100% apple juice (0.058 mg/L) are between the study results of Dehelean and Magdas (2013) and Krejpcio et al. (2005), respectively. Al values of 100% grape juice (0.043 mg/L) is compatible with Madeja and Welna (2013) and Mg values of 100% pomegranate juice (61.70 mg/L) is close to study results of Bayızıt (2010). In apricot nectar, the value of Mg (30.80 mg/L) and K (1038 mg/L) is compatible with Dehelean and Magdas (2013) and Demir and Acar (1995), respectively and the value of Ca (66.09 mg/L) is compatible with Barners (2017). In peach nectar, the values of P (48.10 mg/L) is close to Demir and Acar (1995) and Mg (27.7 mg/L) are between the study results of Velimirović et al. (2013) and Dehelean and Magdas (2013).

Daily intake percentages and health effects of essential elements

Daily essential element requirements for human body which were classified for different age groups and gender are given in Gorgulu et al. (2016). Daily requirements of Co element was not given in detail in literature so the maximum amount for Co was taken as 1 mg/day according to Gorgulu et al. (2016). Daily intake percentages of essential element are calculated by using daily requirements and element intake from the consumption of 200 mL of fruit juices to the human body. Results of daily element intake percentages between the ages of 31–50 for consumption of 200 mL of fruit juices and nectars are shown in Table 4. Macro-elements of K, Ca, P, Mg, Na have various effects on the human body. K is an essential macro mineral required for the maintenance of cellular water balance, acid–base balance and nerve transmission. Human body needs large amounts of K for healthy. Ca is an important micronutrient required for biological functions in the body. It is essential for bones and teeth structure, blood clotting, nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction. It also regulates hormonal secretion and cell division. P is a primary constituent of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) so it is required for energy production, DNA synthesis and protein synthesis. Mg is important for over 500 enzymes that regulate sugar metabolism and it is also used in energy production, cell membrane permeability, and muscle and nerve conduction. Na regulates blood pressure and control the heart beat and it is necessary for brain, nervous system, and muscles (Dehelean et al. 2016; Gorgulu et al. 2016). According to the results obtained, the five macro-element intakes for humans in the juices were found maximum as; K (5.74% for both males and females) in 100% orange juices, Ca (1.42–3.54% for both males and females) in 100% grape juice, P (0.50-2.88% for both males and females) in 100% grape juices, Mg (1.43% for males and 1.85% for females) in 100% orange juices and Na (0.19–0.30% for both males and females) in 100% apple juices and cherry nectar.

Table 4.

Daily intake percentages of essential elements with the consumption of 200 mL of fruit juice (19-50 years)

| Elements | 100% Apple (%) | 100% Pomegranate (%) | 100% Grape (%) | 100% Orange (%) | Orange (%) | Cherry (%) | Apricot (%) | Peach (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Male | 0.51–1.28 | 1.29–3.23 | 1.42–3.54 | 0.96–2.40 | 0.71–1.78 | 0.55–1.37 | 0.52–1.32 | 0.43–1.07 |

| Female | 0.51–1.28 | 1.29–3.23 | 1.42–3.54 | 0.96–2.40 | 0.71–1.78 | 0.55–1.37 | 0.52–1.32 | 0.43–1.07 | |

| Cr | Male | 6.85 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5.71 | |||

| Female | 9.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 8 | ||||

| Cu | Male | 0.02–0.15 | 0.16–1.82 | 0.16–1.84 | 0.09–1.06 | 0.03–0.33 | 0.03–0.28 | 0.15–1.64 | 0.16–1.84 |

| Female | 0.02–0.15 | 0.16–1.82 | 0.16–1.84 | 0.09–1.06 | 0.03–0.33 | 0.03–0.28 | 0.15–1.64 | 0.16–1.84 | |

| Fe | Male | 0.10–0.56 | 0.09–0.52 | 0.15–0.85 | 0.20–1.13 | 0.03–0.16 | 0.08–0.48 | 0.39–2.23 | 0.09–0.51 |

| Female | 0.10–0.25 | 0.09–0.23 | 0.15–0.38 | 0.20–0.50 | 0.03–0.07 | 0.08–0.21 | 0.39–0.99 | 0.09–0.22 | |

| K | Male | 3.81 | 4 | 4.59 | 5.74 | 4.19 | 2.4 | 4.41 | 3.58 |

| Female | 3.81 | 4 | 4.59 | 5.74 | 4.19 | 2.4 | 4.41 | 3.58 | |

| Mg | Male | 0.95 | 1 | 1.15 | 1.43 | 1.05 | 0.6 | 1.10 | 0.89 |

| Female | 1.23 | 1.29 | 1.48 | 1.85 | 1.35 | 0.77 | 1.42 | 1.15 | |

| Mo | Male | 0.07–3.11 | 0.07–3.11 | ||||||

| Female | 0.07–3.11 | 0.07–3.11 | |||||||

| Mn | Male | 0.19–0.91 | 0.02–0.11 | 0.15–0.75 | 0.05–0.25 | 0.02–0.13 | 0.08–0.41 | 0.016–0.78 | |

| Female | 0.19–1.16 | 0.02–0.14 | 0.15–0.96 | 0.05–0.32 | 0.02–0.16 | 0.08–0.52 | 0.16–1.00 | ||

| Na | Male | 0.19–0.30 | 0.14–0.21 | 0.15–0.22 | 0.07–0.10 | 0.05–0.08 | 0.19–0.30 | 0.02–0.04 | 0.04–0.06 |

| Female | 0.19–0.30 | 0.14–0.21 | 0.15–0.22 | 0.07–0.10 | 0.05–0.08 | 0.19–0.30 | 0.02–0.04 | 0.04–0.06 | |

| P | Male | 0.18–1.04 | 0.45–2.58 | 0.50–2.88 | 0.44–2.55 | 0.25–1.46 | 0.24–1.38 | 0.23–1.33 | 0.24–1.37 |

| Female | 0.18–1.04 | 0.45–2.58 | 0.50–2.88 | 0.44–2.55 | 0.25–1.46 | 0.24–1.38 | 0.23–1.33 | 0.24–1.37 | |

| Zn | Male | 0.007–0.03 | 0.04–0.14 | 0.05–0.17 | 0.02–0.09 | 0.008–0.03 | 0.003–0.01 | 0.04–0.15 | 0.02–0.08 |

| Female | 0.007–0.03 | 0.04–0.2 | 0.05–0.23 | 0.02–0.12 | 0.008–0.04 | 0.003–0.01 | 0.04–0.20 | 0.02–0.11 |

Trace and ultra trace elements of Fe, Mn, Zn, Cr, Cu and Mo have also lots of effects on human health. Iron is required to deliver oxygen throughout the body and is an essential part of hemoglobin. Manganese plays role in regulation glucose metabolism in the human body. Zn is involved in the metabolism of energy, proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and nucleic acids and supports normal growth and development in pregnancy, childhood, and adolescence. It is also necessary for enzymatic activity and cofactor of more than 300 metalloenzymes.

Chromium improving tyrosine kinase activity on the insulin receptor is necessary for insulin activity. Copper is important for iron assimilation and hemoglobin synthesis and low Cu intake causes some negative effects on the health such as bone malformation during development, impaired melanin synthesis, poor immune response. Molybdenum (Mo) is involved in several enzymes used in DNA metabolism. According to the results obtained, the trace element intakes for humans in the juices were found maximum as; Fe (0.39–2.23% for males and 0.39–0.99% for females) in apricot nectar, Mn (0.19–0.91% for males and 0.19–1.16% for females) in 100% apple juices, Zn (as 0.05–0.17% for males and 0.05–0.23% for females) in 100% grape juices, Cr (6.85% for males and 9.6% for females) in 100% apple juices, Cu (0.16% for males and 1.84% for females) in 100% grape juice and peach nectar and Mo (0.07–3.11% for both males and females) in 100% apple juice and peach nectar.

Non-carcinogenic risk

THQ and HI are recognized as useful parameters for evaluating health risks associated. When HI values are less than 1, there is no health risk for human, but if these values higher than 1, there may be concerned for potential health risk (Kamunda et al. 2016). In present study THQ values of non-essential and trace/ultra trace elements in analysed fruit juices were calculated and shown in Table 5. Equation (3) was used for calculation of THQ values and calculated separately for each element and juice. When the results are examined, it was seen that risk assessments of individual metals via juices ingestion are found to be within safe limits (THQ < 1).

Table 5.

THQ, HI and TR values of non-essential and trace/ultra trace of essential elements in analysed fruit juices

| Elements | THQ values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% apple | 100% pomegranate | 100% grape | 100% orange | Orange nectar | Cherry nectar | Apricot nectar | Peach nectar | |

| Al | 1.23E−4 | 1.35E−3 | 1.43E−4 | – | – | 7.67E−5 | 2.38E−3 | 2.77E−3 |

| Ba | 6.000E−4 | 1.250E−3 | 2.500E−4 | 4.67E−4 | 2.33E−4 | 7.000E−4 | 4.67E−4 | 2.000E−4 |

| Cr | 2.67E−5 | – | 1.56E−5 | – | – | 1.56E−5 | 1.56E−5 | 2.22E−5 |

| Cu | 5.83E−4 | 6.83E−3 | 6.92E−3 | 4.000E−3 | 1.250E−3 | 1.083E−3 | 6.17E−3 | 6.92E−3 |

| Fe | 1.080E−3 | 1.004E−3 | 1.63E−3 | 2.17E−3 | 3.14E−4 | 9.29E−4 | 4.26E−3 | 9.76E−4 |

| Mn | 2.500E−3 | 3.095E−4 | 2.07E−3 | 6.904E−4 | – | 3.57E−4 | 1.12E−3 | 2.14E−3 |

| Mo | 4.67E−3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4.67E−3 |

| Ni | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.000E−3 | 5.000E−4 |

| Pb | 5.370E−2 | 5.092E−2 | 2.96E−2 | – | – | – | 1.120E−1 | 1.250E−1 |

| Zn | 1.67E−4 | 8.89E−4 | 1.044E−3 | 5.44E−4 | 1.78E−4 | 6.67E−5 | 9.000E−4 | 5.11E−4 |

| ∑ HI | 6.35E−2 | 6.26E−2 | 4.170E−2 | 7.87E−3 | 1.98E−3 | 3.23E−3 | 1.303E−1 | 1.44E−1 |

| Pb | 1.64E−6 | 1.56E−6 | 9.066E−7 | – | – | – | 3.43E−6 | 3.83E−6 |

| Ni | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.020E−4 | 1.700E−5 |

| ∑ TR | 1.64E−6 | 1.56E−6 | 9.066E−7 | – | – | – | 1.054E−4 | 2.082E−5 |

Taking the THQ values of fruit juices samples into consideration, Eq. (4) was used to estimate the total health risk index (HI) value caused by Al, Ba, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb and Zn. Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo and Zn are essential elements for human health at low concentrations; however, they can show toxic effect when consumed at high concentrations.

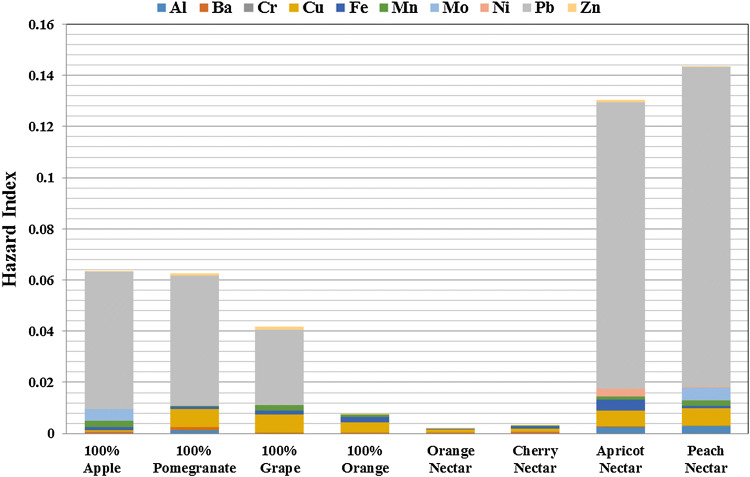

As shown in Fig. 1, the main reason of the obtained HI values was Pb content of samples and when fruit juices were compared, the highest HI value was seen in peach nectar.

Fig. 1.

Hazard Index values of fruit juices

The trends of HI values for the 100% fruit juice and fruit nectar samples were in descending order to peach nectar > apricot nectar > 100% apple juice > 100% pomegranate juice > 100% Grape juice > 100% orange juice > cherry nectar > orange nectar.

According to the results of the risk analysis of the elements in fruit juice samples, the Hazard Index was founded as less than 1 which is calculated for 200 mL consumption of juice and these fruit juice samples had been included in the low-risk group.

Carcinogenic risk

TR value is a term used to cancer risk assessment and define that it is the probability of an individual developing any type of cancer from lifetime exposure to carcinogenic hazards. According to the US EPA risk management guidelines, the value of acceptable risk is between 1 × 10−6 and 1 × 10−4 (Wang et al. 2016).

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) categorized carcinogenicity of chemicals to four group such as Group 1: carcinogenic to humans, Group 2A: probably carcinogenic, Group 2B: possibly carcinogenic, Group 3: not classifiable. According to IARC, non-essential and trace/ultra trace elements are classified as As, Cd, Cr(hexavalent chromium compounds), Ni (Nickel compounds) in Group 1; Co, Pb, Ni (Metallic nickel) in Group 2B and Cr, Fe, Pb, Se, Ti in Group 3 (Mulware 2013).

The elements in the Group 3 are not used in the cancer risk assessment. Chromium in Group 1 is human carcinogen by the inhalation route of exposure. For the oral consumption, chromium (VI) is classified as Group 3, not classified as to human carcinogenicity (IRIS 2001).

In the analyzes made within the scope of this study there was no As, Cd and Co elements in fruit juices samples so they have not been taken into consideration for risk calculation. TR values of analyzed fruit juices are also calculated and shown in Table 5. According to the results the TR value was founded as less than 1 × 10−4 for juices except apricot nectar. In apricot nectar it was seen that TR value was equal to 1 × 10−4 which is the limit value. However, results of cancer risk calculation for all juices were not higher than limit value and there was no cancer risk in daily consumption of 200 mL of fruit juice.

Conclusion

Contents of some essential and non-essential elements in fruit juices samples sold in Istanbul, Turkey were measured in the present study. The amounts of K were significantly higher than other elements in all samples and it is followed by Ca (max: 177 mg/L; in 100% grape juices), P (max: 100.9 mg/L; in 100% grape juices), Mg (max: 73.3 mg/L; in 100% orange juices) and Na (max: 23 mg/L; in cherry nectar), respectively. Trace and ultra trace elements concentrations in fruit juices followed macro-element concentrations. After that, daily intake percentages for 200 mL consumption, THQ, HI and TR values were calculated for selected fruit juices samples. HI values of all samples of presented in this study were determinate as less than 1 and included in low risk group. TR values are used to estimated carcinogenic risk for human body. The value of acceptable risk is between 1 × 10−6 and 1 × 10−4. TR values of all samples of presented in this study were determinate as less than 1 × 10−4 except apricot nectar whose TR values were equal to limit value and included in low risk group. According to carcinogenic risk assessment results there was no cancer risk in all analyzed fruit juice samples.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by Yildiz Technical University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Department. Project Number: 2015-07-01-YL03.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akhtar S, Ali J, Javed B, Khan FA. Studies on the preparation and storage stability of pomegranate juice based drink. Middle-East J Sci Res. 2013;16:91–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bamuwamye M, Ogwok P, Tumuhairwe V. Cancer and non-cancer risks associated with heavy metal exposures from street foods: evaluation of roasted meats in an urban setting. J Pollut Hum Health. 2015;3:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bao SX, Wang ZH, Liu JS. X-ray fluorescence analysis of trace elements in fruit juice. Spectrochim Acta, Part B. 1999;54:1893–1897. doi: 10.1016/S0584-8547(99)00160-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barners KW (2017) The analysis of trace metals in fruit, juice and juice production using a dual-view plasma. Perkin Elmer Instruments. Retrieved from https://www.perkinelmer.com.cn/PDFs/downloads/APP_TraceMetalsinFruitJuicesViewPlasma.pdf

- Bartoszek M. A comparison of antioxidative capacities of fruit juices, drinks and nectars, as determined by EPR and UV–vis spectroscopies. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2016;153:546. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayızıt AA. Analysis of mineral content in pomegranate juice by ICP-OES. Asian J Chem. 2010;8:6542–6546. [Google Scholar]

- Bhupander K, Mukherjee DP. Assessment of human health risk for arsenic, copper, nickel, mercury and zinc in fish collected from tropical wetlands in India. Adv Life Sci Technol. 2011;2:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dehelean A, Magdas DA. Analysis of mineral and heavy metal content of some commercial fruit juices by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Sci World J. 2013;2013:215423. doi: 10.1155/2013/215423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehelean A, Magdas DA, Puscas R, Lung I, Stan M. Quality assessment of some commercıal romanıan juıces. Rom Rep Phys. 2016;68:746–759. [Google Scholar]

- Demir N, Acar J. Ankara’da tüketime sunulan bazı meyve sularının mineral madde içerikleri üzerine bir araştırma. Gıda. 1995;20:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Demir F, Kipcak AS, Ozdemir DO, Moroydor ED, Piskin S. Determination and comparison of some elements in different types of orange juices and investigation of health effects. Int J Biol Biomol Agric Food Biotechnol Eng. 2015;9:5. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta TK, Mukta V. Trace elements. Med Update. 2012;22:353–357. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2017) FaoStat: agriculture data. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-au112e.pdf

- Farid SM, Enani MA. Levels of trace elements in commercial fruit juices in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Med J Islam World Acad Sci. 2010;18:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgulu YT, Kipcak AS, Ozdemir OD, Derun EM, Piskin S. Examination of the lemon effect on risk element concentrations of herbal and fruit teas. Czech J Food Sci. 2014;32:555–562. doi: 10.17221/83/2014-CJFS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgulu TY, Ozdemir OD, Kıpcak AS, Piskin MB, Derun EM. The effect of lemon on the essential element concentrations of herbal and fruit teas. Appl Biol Chem. 2016;59:425–431. doi: 10.1007/s13765-016-0161-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri E, Abboud MI, Demirdjian S, Korfali S, Mroueh M, Tale RI. Carcinogenic and neurotoxic risks of acrylamide and heavy metals from potato and corn chips consumed by the Lebanese population. J Food Compo Anal. 2015;42:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2015.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IRIS(2001) Integrated risk information system. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved from https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/toxreviews/0144tr.pdf

- Kamunda C, Mathuthu M, Madhuku M (2016) Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Soils from Witwatersrand Gold Mining Basin. South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13:663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Keil DE, Ritchie JB, McMillin GA. Testing for toxic elements: a focus on arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury. Labmedicine. 2011;42:735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Jeong IS, Hwang IM, Kim JS, Choi SH, Nho EY, Choi JY, Kwak B-M, Ahn JH, Yoon T, Kim KS. Method validation for simultaneousdetermination of chromium, molybdenum and selenium in infant formulas by ICP-OES and ICP-MS. Food Chem. 2013;141:3566–3570. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejpcio Z, Sionkowski S, Bartela J. Safety of fresh fruits and juices available on the polish market as determined by heavy metal residues. Pol J Environ Stud. 2005;14:877–881. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zhang Q. Risk assessment and seasonal variations of dissolved trace elements and heavy metals in the Upper Han River, China. J Hazard Mater. 2010;181:1051–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.05.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeja AS, Welna M. Evaluation of a simple and fast method for the multi-elemental analysis in commercial fruit juice samples using atomic emission spectrometry. Food Chem. 2013;141:3466–3472. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeja AS, Welna M, Jedryczko D, Pohl P. Developments and strategies in the spectrochemical elemental analysis of fruit juices. Trends Anal Chem. 2014;55:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2013.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulware SJ. Trace elements and carcinogenicity: a subject in review. Biotech. 2013;3:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s13205-012-0072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramod HP, Devendra JH. Determination od specific heavy metals in fruit juices using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) Int J Res Chem Environ. 2014;4(163):168. [Google Scholar]

- Saiful Islam Md, Kawser Ahmed Md, Habibullah-Al-Mamun Md, Raknuzzaman M. The concentration, source and potential human health risk of heavy metals in the commonly consumed foods in Bangladesh. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2015;122:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovska N, Popovski O. Analysis of the chemical toxic and essential elements in fruit juices. J Hyg Eng Des. 2012;1:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vallapragada VV, Inti G, Sri Ramulu J. Validated inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) method to estimate free calcium and phosphorus in in vitro phosphate binding study of eliphos tablets. Am J Anal Chem. 2011;2:718–725. doi: 10.4236/ajac.2011.26082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velimirović DS, Mitić SS, Tošić SB, Kaličanin BM, Pavlović AN, Mitić MN. Levels of major and minor elements in some commercial fruit juices available in Serbia. Trop J Pharm Res. 2013;12:805–811. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Pan Y, Tian S, Chen X, Wang L, Wang Y. Size distributions and health risk of particulate trace elements in rural areas in northeastern China. Atmos Res. 2016;168:191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2015.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhang H, Liu G, Zhang J, Wang J, Yu Y. Concentrations and health risk assessment of trace elements in animal-derived food in southern China. Chemosphere. 2016;144:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Liu Y, Achal V, Fu QL, Li L. Health risk assessment of Al and heavy metals in milk products for different age groups in China. Pol J Environ Stud. 2015;24:2707–2714. doi: 10.15244/pjoes/58964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]