Abstract

In this research, biogenic amine content, acidity, pH values, total free amino acid content (TFAA), ash content, colour values (CIE L*, a*, b*), total phenolic compound content (TPCC) and antioxidant activity values of tarhana, which were fortified with pomegranate seed extract (PSE) in different ratios (0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%) were evaluated during six months of storage. It has been evaluated that pomegranate seed extract causes increase on TPCC, ash content and antioxidant activity values. Putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine, spermine, histamine, tyramine were studied as biogenic amines. Standard addition and internal standard techniques were performed for quantification of biogenic amines. Recovery rates were found between 87.0% and 94.6%. Total biogenic amine contents of tarhana samples decreased during the first two months of storage, remained constant and increased slightly for the next four months. It was found that, pomegranate seed extract causes decrease on biogenic amine content of tarhana samples. While the average total biogenic amine content in control group was 894.70 mg/kg, tarhana samples which were fortified with pomegranate seed extracts in ratios of 0.5%, 1%, 2% contained 569.67 mg/kg, 514.52 mg/kg, 424.60 mg/kg total biogenic amine, respectively.

Keywords: Biogenic amine, Phenolic compound, Pomegranate seed extract, Tarhana

Introduction

Biogenic amines are produced by the activity of either plant enzymes or microbial enzymes of various species of bacteria via decarboxylation mechanism of amino acids (Silla-Santos 1996). The most abundant biogenic amines in foods are histamine, tyramine, putrescine, cadaverine, tryptamine, agmatine, spermine and spermidine (Shalaby 1996). The highest concentrations of such amines are encountered in fish and fermented foods (Silla-Santos 1996; Shalaby 1996). The concentration and variety of biogenic amines in foods are affected by different factors such as composition of foodstuff, microbial flora, and intrinsic and extrinsic factors causing bacterial growth during several stages of food processing (Carelli et al. 2007).

The intake of high amount of biogenic amines with foods could cause toxic effect in human body with a variety of symptomatic signs (Alvarez and Moreno-Arribas 2014). In addition, for some foodstuff, biogenic amines were reported as indication of quality and acceptability criteria (Shalaby 1996; Alvarez and Moreno-Arribas 2014). As a recent class of plant growth regulators, polyamines play role in different physiological activities in plants (Kalac 2014). Polyamines consist of putrescine, spermidine and spermine. Nout (1994) suggested 100 mg/kg histamine, 800 mg/kg tyramine, and 30 mg/kg 2-phenylethylamine as safe levels for foods. Total concentration of biogenic amines up to 1000 mg/kg can be safe level in foods according to Silla-Santos (1996).

Biogenic amines in foods can be quantified using several analytical methods, such as gas chromatography, capillary electrophoresis, enzymatic methods and immunoassays (Lange and Wittmann 2002). In addition, a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with fluorescence or ultraviolet (UV) detector can detect and quantify biogenic amines with a high accuracy and sensitivity; and therefore HPLC is commonly used in biogenic amine studies (Ozdestan and Uren 2009).

In 1500s, it was the first time that Turkish people prepared tarhana for a longer/better/easier storage of meals in Middle Asia, and then it became known by many people in different regions of the world (Ozdemir et al. 2007). Similar to tarhana, as a fermented product, kishk in south-east part of Mediterranean Sea, and kushuk in east of Mediterranean (in Iraq) are traditional foods (Alnouri et al. 1974). Also in Europe, tarhana is known as tahonya/talkuna in Hungary and Finland, trahana in Greece and atole in Scotland (Tamime et al. 2000). Tarhana formulation may differ according to the region, technique and the type of ingredients; however, it mainly contains yoghurt, flour, salt, vegetables and spices. Tarhana is prepared by mixing these ingredients and then lactic acid and alcoholic fermentation take place for a timescale of min. 1 day and max. 15 days. Following the fermentation process, the prepared dough is dried by some means; conventional sun drying is a commonly used method, however recent industrial drying techniques can also be used. After drying is completed, dough is finely ground and in the end, the product has very small particles almost like a powder. In recent years many studies have been performed about increasing functional and nutritional properties of tarhana by increasing total phenolic compound contents (TPCC) of samples (Değirmencioğlu et al. 2016). The following average interval values were reported in tarhana by Ozdemir et al. (2007): moisture 6–10%, protein 12–20%, carbohydrates 40–75%, fat 1–9% and ash 1.5–4.0%. Tarhana is a good source of calcium, magnesium and potassium. Tarhana is a nutritious food as it contains both vegetable and animal proteins, vitamins and minerals and is therefore used largely for feeding children and elderly people (Bilgiçli et al. 2006).

Tarhana is mainly consumed as soup in Turkey. Tarhana powder is first mixed with cold water (1:5) and then allowed to dissolve for about half an hour, and finally cooked for 20 min with stirring (Ozdemir et al. 2007).

Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) is widely grown in many regions and warm climates (Fadavi et al. 2005). The pomegranate seeds constitute one-fifth of the whole fruit on weight basis (Jing et al. 2012). Several studies indicated that pomegranate seed is a nutritious by-product including high amount of antioxidants. For instance, Guo et al. (2007) suggested that when the seeds were consumed as a supplementary food, DNA damage could be decreased or totally suppressed, and thereby decreasing the probability of cancer. Bioactive compounds (particularly polyphenols) of pomegranate seeds cause such health-related beneficial effects. These polyphenols have high antioxidant effect. Although pomegranate seed extract (PSE) was widely studied for its functional properties (Jing et al. 2012), there is not enough scientific knowledge about the inhibitory effect of PSE on the formation of biogenic amines. In this research, biogenic amine content, acidity, pH values, TFAA content, ash content, colour values (CIE L*, a*, b*), TPCC and antioxidant activity values of tarhana, which were fortified with pomegranate seed extract in different ratios (0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%) were evaluated during six months of storage.

Materials and methods

Materials

Samples

For tarhana dough, wheat flour, strained yoghurt, tomato, red pepper, table salt, onion, tarhana herb, mint and dill were purchased from the local markets in Izmir, Turkey. Pomegranate seed extract (Balen, Turkey) was obtained from the market as powder (purity 100%) in Izmir, Turkey.

Reagents

Cadaverine dihydrochloride, spermidine trihydrochloride, spermine, histamine dihydrochloride, tyramine, gallic acid, and DPPH (1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical) were obtained from Sigma (Steinheim, Germany). 1,7-diaminoheptane (Merck, Schuchardt, Germany) was used as internal standard. Putrescine dihydrochloride was obtained from Fluka (Steinheim, Germany). Sodium hydroxide, benzoyl chloride, sodium chloride, anhydrous sodium sulfate, cadmium acetate dihydrate, ninhydrin, ethanol, acetic acid, L-leucine, trichloroacetic acid, nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide and Folin-Ciocalteu reagent were supplied from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Hydrochloric acid was bought from J. T. Baker (Deventer, Holland). Methanol, acetonitrile, and diethyl ether (all of them HPLC grade) were purchased from Lab-Scan (Dublin, Ireland). Sodium acetate trihydrate was supplied from Riedel (Germany). Phenolphthalein was obtained from Panreac (Barcelona, Spain).

Methods

Production of tarhana samples

The formulation of control tarhana sample and the pomegranate seed extract fortified samples were presented as A, B, C and D in Table 1. Onions, tomatoes and red peppers were chopped and cooked for 15 min and then cooled to room temperature. The cooked vegetables and yoghurt were added to the flour and then all ingredients were mixed together for 5 min to obtain homogenized dough. The tarhana dough was fermented at 30 °C for 15 days. After the fermentation the dough was divided into small pieces of about 5–6 g and dried in an air-oven at 70 °C until a moisture content of about 10%. After drying, samples were milled in a hammer mill (Armfield Ltd., Ringwood, UK) and sifted through a 1 mm screen sieve. The samples were stored in cloth bags at 25 °C until being analysed. PSE was added in formulation with flour as 0.5%, 1%, 2% (on weight of wheat flour). Triplicate samples were taken for chemical analyses at particular months (0, 1, 2, 4, 6) during storage since it is generally prepared in summer to consume in winter times.

Table 1.

Tarhana formulations

| Ingredients | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Control sample) | (0.5% PSE) | (1% PSE) | (2% PSE) | |

| (g) | (g) | (g) | (g) | |

| Tomato | 450 | 450 | 450 | 450 |

| Pepper | 350 | 350 | 350 | 350 |

| Onion | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Strained yoghurt | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Wheat flour | 1000 | 995 | 990 | 980 |

| Salt | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Baker's yeast | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Pomegranate seed extract (PSE) | – | 5 | 10 | 20 |

Samples were produced twice

Derivatization of biogenic amines

Benzoyl chloride was used for derivatization of biogenic amines. The method of Ozdestan and Uren (2009) was used for this purpose. The standard addition technique was used for quantifications.

Chromatographic conditions

Biogenic amines were separated according to the method explained in the study of Yeğin and Uren (2008). A binary gradient elution including methanol and acetate buffer was used.

Determinations of pH, acidity, total dry matter content, total ash content, colour value, total free amino acid content, total phenolic compound content, and antioxidant activity.

A digital pH meter was used for the determination of pH values of tarhana samples (Erbaş et al. 2006). The acidity (as lactic acid) of tarhana samples was calculated by titrating the samples with 0.1 M NaOH (Ibanoglu et al. 1999). The total dry matter content was determined by keeping the samples in an oven at 105 °C until a constant weight was reached (Ibanoglu et al. 1999). The total ash content of the samples was determined by ashing samples in an ash oven at 600 °C (AOAC 1990). Colour measurements of the tarhana samples were carried out using a Hunter Lab Color flex (CFLX 45–2 Model Colorimeter, Hunter Lab, Reston, VA). The values were expressed as L*, a*, and b*. The total free amino acid (TFAA) contents (as leucine) of tarhana samples were quantified following the method of Folkertsma and Fox (1992). The total phenolic compound content (TPCC) analysis was performed by slightly modifying the method of Xu and Chang (2007). Antioxidant activity of the samples was determined according to the DPPH radical-scavenging assay method (Brand-Williams et al. 1995).

Apparatus

Quantification of biogenic amines were performed by using an Agilent 1260 Infinity liquid chromatograph (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). C18 column (10 μm particle size, 300 mm, 3.9 mm i.d., Hichrom Ltd., Theale, U.K.) was used for separation in HPLC. A Hanna Instrument 9124 pH Meter (Hanna Instruments, Romania) was used for the determination of pH values. Sigma 4–165 centrifuge instrument was used for sample preparation. Agilent Cary 60 UV–Visible spectrophotometer (Varian, U.K.) was used for total free amino acid content, TPCC, antioxidant activity analyses. Hunter Lab Color Flex CFLX 45–2 colorimeter (Hunter Lab, Reston, VA) was used for colour analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS 24.0 statistics package program using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) and Pearson correlation test (P < 0.05). All trials were made triplicate.

Results and discussion

pH, acidity, total dry matter content, ash content, and total free amino acid content of tarhana samples during storage period were shown in Table 2. pH values of tarhana samples were found between 3.61 and 4.12. According to ANOVA and DMRT, statistically significant differences were found between pH values of different tarhana samples (P < 0.05). In addition, the pH values of tarhana samples vary from each other during storage period (P < 0.05). pH values of tarhana samples decreased during the first two months of storage period and remained constant during the next storage period. This could be related with continuing microbial activity during the first two months of storage. Acidity values of tarhana samples were found between 1.18 and 1.49%. The highest acidity values were found in 2% fortified tarhana samples. The fortification with 2% PSE caused statistically significant difference in acidity values (P < 0.05). Acidity values of tarhana samples increased during first two months of storage period and were constant during the rest of the storage period. Total dry matter contents of samples were detected between 89.03 and 90.95%. No significant difference between the total dry matter content of different tarhana samples was observed (P > 0.05). The highest total dry matter content was found in the six month stored samples and the lowest total dry matter content was found in the two month stored samples (P < 0.05). Mean ash content of tarhana samples were found as 3.99%, 4.04%, 4.15% and 4.24% for control, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, PSE fortified samples, respectively. PSE addition caused a signigicant increase in ash content (P < 0.05). Ash contents of tarhana samples decreased during the first month of storage period and increased during the storage period. The reason of this situation was related with the changes on the content of dry matter. A possible change in the free amino acid content of tarhana could have affected the formation of biogenic amine through the mechanism of decarboxylation. TFAA content of tarhana samples were found between 0.017% and 0.042%. No siginificant differences were detected between the TFAA content of tarhana samples (P > 0.05). TFAA content generally increased for the first 2 months storage period then decreased and remained constant unproportional with the results of total biogenic amine content. As a result, it is thought that total free amino acids are pre-substances for the formation of biogenic amines. Ozdestan and Uren (2013) determined pH, acidity, total dry matter, total free amino acid and biogenic amine content of home-made and commercially produced tarhana samples. The pH values of tarhana samples were found in the range from 3.43 to 5.03; acidities were from 0.60 to 3.89 g/100 g tarhana (as lactic acid); total dry matters were from 86.42 to 92.32 g/100 g tarhana; and total free amino acid contents were from 0.035 to 1.427 g/100 g tarhana (as leucine) by Ozdestan and Uren (2013). Our results were compatible to the results of Ozdestan and Uren (2013) with slight differences. The reason of this difference thought to be related with different formulations and production conditions of tarhana samples.

Table 2.

pH, acidity, total dry matter content, ash content, and total free amino acid content of tarhana samples during storage period

| Analysis | 0 month | 1 month | 2 month | 4 month | 6 month | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | pH | 4.12Bb ± 0.00 | 4.11Bb ± 0.02 | 3.70Ab ± 0.02 | 3.71Ab ± 0.02 | 3.71Ab ± 0.02 |

| B | 4.11Bb ± 0.03 | 4.10Bb ± 0.03 | 3.71Bb ± 0.02 | 3.71Ab ± 0.03 | 3.71Ab ± 0.02 | |

| C | 4.09Bb ± 0.04 | 4.10Bb ± 0.05 | 3.74Ab ± 0.04 | 3.70Ab ± 0.04 | 3.70Ab ± 0.02 | |

| D | 4.04Ba ± 0.05 | 4.01Ba ± 0.05 | 3.64Aa ± 0.05 | 3.61Aa ± 0.02 | 3.61Aa ± 0.05 | |

| A | Acidity (%, w/w, as lactic acid) | 1.18Aa ± 0.02 | 1.17Aa ± 0.02 | 1.41Aa ± 0.02 | 1.42Aa ± 0.02 | 1.42Ba ± 0.06 |

| B | 1.17Aa ± 0.05 | 1.18Aa ± 0.04 | 1.40Bab ± 0.03 | 1.41Ba ± 0.02 | 1.42Ba ± 0.02 | |

| C | 1.19Aab ± 0.01 | 1.20Aab ± 0.02 | 1.40Bab ± 0.04 | 1.43Ba ± 0.03 | 1.44Bab ± 0.04 | |

| D | 1.23Ab ± 0.13 | 1.23Ab ± 0.03 | 1.44Bb ± 0.02 | 1.47BCb ± 0.03 | 1.49Cb ± 0.03 | |

| A | Dry matter content (%, w/w) | 90.53C ± 0.39 | 89.46AB ± 0.29 | 89.15A ± 0.20 | 90.05BC ± 0.77 | 90.58C ± 0.06 |

| B | 89.73B ± 0.65 | 89.18A ± 0.31 | 89.03A ± 0.16 | 89.99B ± 0.21 | 90.83C ± 0.19 | |

| C | 90.52C ± 0.25 | 89.61B ± 0.39 | 89.95A ± 0.16 | 90.27CD ± 0.40 | 90.92D ± 0.33 | |

| D | 89.96B ± 0.57 | 89.37AB ± 0.37 | 89.12A ± 0.13 | 89.96B ± 0.38 | 90.95C ± 0.28 | |

| A | Ash content (%, w/w) | 3.98Aa ± 0.03 | 3.96Aa ± 0.03 | 3.99Aa ± 0.03 | 4.01Aa ± 0.03 | 3.97Aa ± 0.02 |

| B | 4.08Bb ± 0.01 | 4.02Ab ± 0.03 | 4.05ABb ± 0.01 | 4.06ABb ± 0.02 | 4.01Ab ± 0.04 | |

| C | 4.21Dc ± 0.02 | 4.13Bc ± 0.02 | 4.17Cc ± 0.01 | 4.16BCc ± 0.02 | 4.09Ac ± 0.01 | |

| D | 4.26Bd ± 0.03 | 4.22ABd ± 0.02 | 4.21Ad ± 0.03 | 4.26Bd ± 0.03 | 4.24ABd ± 0.01 | |

| A | Total free amino acid content (%, w/w, as leucine) | 0.020aC ± 0.002 | 0.023bBC ± 0.004 | 0.043aA ± 0.010 | 0.033bB ± 0.001 | 0.031bB ± 0.003 |

| B | 0.024aB ± 0.003 | 0.025bB ± 0.002 | 0.034aA ± 0.003 | 0.038bA ± 0.002 | 0.037bA ± 0.004 | |

| C | 0.021aC ± 0.002 | 0.024bC ± 0.001 | 0.042aA ± 0.005 | 0.036bB ± 0.002 | 0.035bB ± 0.002 | |

| D | 0.024aB ± 0.002 | 0.016aC ± 0.001 | 0.034aA ± 0.004 | 0.017aC ± 0.004 | 0.017aC ± 0.003 |

ADifferent matching upper-case letters in the same line mean significant differences between different months according to DMRT (P < 0.05)

aDifferent matching lower-case letters in the same column mean significant differences between the sample groups according to DMRT (P < 0.05)

Total phenolic compound content (TPCC), antioxidant activity, L*, a*, and b* values of tarhana samples during storage period were given in Table 3. TPCC of samples were detected between 842.24 and 7744.23 mg/kg for all samples. Significant differences between phenolic contents were detected by the addition of PSE in tarhana samples (P < 0.05). TPCC of tarhana samples increased by the addition of PSE. During the storage, 2% PSE fortified samples had the highest TPCC. TPCC of 2% fortified samples were 5.9 times higher than the control group samples. Statistically significant decrease was obtained between TPCC of all samples during storage period (P < 0.05). This could be related with the decomposition of phenolic compounds during storage period. According to Çalışkan Koç and Özçıra (2019) the addition of the wheat germ to the tarhana formulation resulted in a significant increase in the total phenolic content similar to our result (P < 0.05). They found the total phenolic compound content of tarhana samples between 1320.03 and 3436.09 mg/kg. The differences between the results may be due to the different ingredients and replacement ratios and duration of fermentation. Antioxidant activity of samples was determined between 15.19 and 88.40% and increased by the addition of PSE. However, no significant differences were obtained between the antioxidant activity of fortified samples (P > 0.05). In addition, antioxidant activity of tarhana samples during storage was statistically the same (P > 0.05). According to Pearson correlation test, there were positive significant correlations between TPCC and antioxidant activity of tarhana samples (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Total phenolic content, antioxidant activity, L*, a*, and b* values of tarhana samples during storage period

| Biogenic amines | Samples | 0 month | 1 month | 2 month | 4 month | 6 month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Total phenolic content (mg/kg, as gallic acid) | 1231.62Ca ± 4.34 | 976.99Ba ± 38.56 | 872.94Aa ± 48.81 | 847.56Aa ± 11.68 | 842.24Aa ± 20.95 |

| B | 2945.26Cb ± 38.50 | 2834.09Cb ± 6.67 | 2303.52Bb ± 75.20 | 2313.56Bb ± 118.94 | 2113.29Ab ± 52.08 | |

| C | 4790.62Dc ± 46.80 | 3878.75Cc ± 20.10 | 3890.11ABc ± 39.91 | 3772.12Bc ± 100.57 | 3526.4Ac ± 28.77 | |

| D | 7744.23Cd ± 193.56 | 6199.00Cd ± 198.77 | 5785.59Bd ± 102.59 | 5408.41Bd ± 76.81 | 5407.03ABd ± 18.94 | |

| A | Antioxidant activity (% inhibition) | 16.67a ± 1.28 | 15.19a ± 2.47 | 16.24a ± 1.56 | 16.46a ± 1.27 | 17.20a ± 0.97 |

| B | 88.40b ± 0.18 | 88.29 b ± 0.00 | 87.55b ± 0.91 | 87.97b ± 0.32 | 88.40b ± 0.66 | |

| C | 87.03b ± 1.14 | 86.92 b ± 0.48 | 87.87 b ± 0.37 | 86.60b ± 0.66 | 87.56 b ± 0.8 | |

| D | 87.45b ± 0.66 | 87.03 b ± 0.00 | 87.13b ± 0.37 | 87.45 b ± 0.66 | 87.03 b ± 0.00 | |

| A | L* | 65.69c ± 1.05 | 67.09c ± 0.45 | 65.44c ± 0.69 | 66.71c ± 0.89 | 66.31d ± 1.69 |

| B | 59.03b ± 1.38 | 60.65b ± 1.36 | 58.43b ± 0.91 | 59.02b ± 0.62 | 59.10c ± 1.49 | |

| C | 57.45b ± 1.50 | 57.83a ± 1.87 | 56.15a ± 0.37 | 55.65a ± 1.86 | 56.64b ± 0.61 | |

| D | 54.07a ± 0.79 | 59.59a ± 0.80 | 54.31a ± 0.37 | 53.93a ± 1.45 | 53.93a ± 2.05 | |

| A | a* | 30.46cB ± 0.79 | 30.27cB ± 0.61 | 29.48cB ± 0.10 | 27.86cA ± 0.48 | 27.05bA ± 1.62 |

| B | 21.62bD ± 0.60 | 20.82bDC ± 0.6 | 19.99bCB ± 0.29 | 19.49bBA ± 0.75 | 19.57aA ± 0.99 | |

| C | 21.27bB ± 1.44 | 21.42abB ± 1.39 | 20.46bB ± 1.15 | 19.56bA ± 0.97 | 18.00aA ± 1.42 | |

| D | 19.39aA ± 1.14 | 19.39 aA ± 1.6 | 18.77aA ± 0.66 | 17.91aA ± 0.77 | 18.04aA ± 0.97 | |

| A | b* | 45.08cA ± 1.54 | 44.60 cA ± 0.98 | 44.71 cA ± 1.33 | 44.05 cA ± 0.53 | 43.36cA ± 0.90 |

| B | 36.20bA ± 0.47 | 35.87 bA ± 0.17 | 35.28 bA ± 1.06 | 34.84 bA ± 1.13 | 34.55 bA ± 1.84 | |

| C | 35.23bC ± 0.70 | 35.56bC ± 0.61 | 34.47bBC ± 0.60 | 33.46aBA ± 0.39 | 32.62bA ± 1.28 | |

| D | 30.18aA ± 1.46 | 31.37 aA ± 1.73 | 30.37aA ± 2.10 | 29.17aA ± 2.15 | 29.91aA ± 2.63 |

ADifferent matching upper-case letters in the same line mean significant differences between different months according to DMRT (P < 0.05)

aDifferent matching lower-case letters in the same column mean significant differences between the sample groups according to DMRT (P < 0.05)

The maximum L* value was belong to control sample. L* values of tarhana samples were in the range of 53.93 and 67.09. PSE addition caused significant decrease on L*, a* and b* values of samples (P < 0.01), whereas L* values during storage had no statistical difference (P > 0.05). a* values were between 17.91 and 30.46 and b* values were between 29.17 and 45.08. a* and b* values decreased during storage but no significant difference was seen on a* and b* values during storage (P > 0.05).

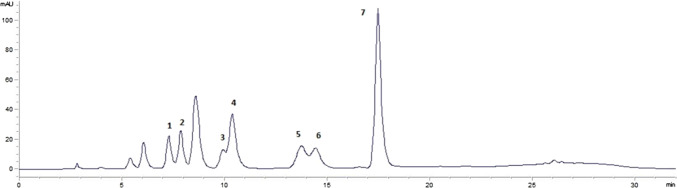

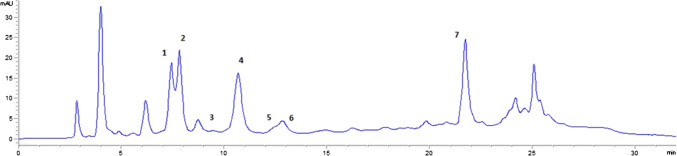

Biogenic amine contents of tarhana samples were given in Table 4. The chromatograms for standards and that for a 2% PSE added tarhana sample for 0th month were given in Figs. 1, 2, respectively. Putrescine, cadaverine, histamine and tyramine were detected in all samples during the storage period, whereas spermine and spermidine could not be detected at some times during storage. Among biogenic amines, concentration of tyramine was the highest in tarhana, of which the maximum concentration was detected as 206.42 mg/kg in control sample. During storage period, tyramine concentration increased from 137.6 to 206.42 mg/kg in control sample. In the literature, the range of tyramine content for tarhana was reported as: 6.9–267.1 mg/kg and it was differed according to the formulation of tarhana which was similar with our results Keşkekoğlu and Uren (2013).

Table 4.

Mean biogenic amine contents (mg/kg) and standard deviation values of tarhana samples

| Biogenic amines | Samples | 0 month | 1 month | 2 month | 4 month | 6 month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putrescine | A | 170.04Cb ± 5.96 | 134.97Ab ± 10.42 | 136.29Aa ± 3.09 | 151.1Bb ± 4.1 | 151.14Ba ± 9.00 |

| B | 165.70Bb ± 6.56 | 132.51Ab ± 13.18 | 129.18Aa ± 15.12 | 133.21Ab ± 3.94 | 124.89Aa ± 16.56 | |

| C | 121.32Aa ± 3.92 | 113.49Aab ± 12.87 | 114.46Aa ± 12.70 | 101.95Aa ± 22.43 | 109.89Aa ± 4.64 | |

| D | 121.40Aa ± 24.91 | 107.5Ab ± 17.92 | 112.8Aa ± 13.35 | 109.05Aa ± 5.96 | 104.4Ab ± 15.97 | |

| Cadaverine | A | 177.17Db ± 2.23 | 151.75ABc ± 4.45 | 141.90Ac ± 5.01 | 160.50BCd ± 8.89 | 163.63CDd ± 9.01 |

| B | 173.58Db ± 17.06 | 137.45ABbc ± 5.35 | 124.28Ab ± 2.34 | 139.60ABc ± 7.80 | 142.29Cc ± 7.90 | |

| C | 159.59Cb ± 12.02 | 131.26Bab ± 12.0 | 125.42Cb ± 8.7 | 123.13Cb ± 4.82 | 125.46Ab ± 4.89 | |

| D | 105.67Aa ± 22.05 | 113.49Aa ± 12.4 | 101.65Aa ± 4.58 | 106.52Aa ± 6.84 | 108.50Aa ± 6.93 | |

| Spermidine | A | 17.40Ab ± 0.20 | 20.37ABa ± 1.42 | 21.93Bb ± 1.57 | 20.70ABa ± 1.85 | 19.81ABb ± 3.50 |

| B | 19.09Ac ± 0.77 | 19.39Aa ± 1.01 | nd | nd | nd | |

| C | 19.34Ac ± 0.42 | 19.14Aa ± 1.00 | 19.09ABa ± 0.12 | 20.88Aa ± 1.21 | 6.60Aa ± 0.67 | |

| D | 8.98Aa ± 0.28 | nd | nd | nd | nd | |

| Spermine | A | 21.96Ba ± 1.50 | 15.21Ac ± 0.50 | nd | nd | 13.68Aa ± 2.44 |

| B | 32.07Db ± 4.06 | 7.09Bb ± 0.20 | 1.60Ab ± 0.33 | 1.24A ± 0.15 | 13.93Ca ± 3.90 | |

| C | 28.66Bb ± 1.13 | 21.37Ad ± 2.36 | nd | nd | 16.19Ca ± 5.33 | |

| D | 21.62Ba ± 4.57 | 4.15Aa ± 0.66 | 4.76Aa ± 0.48 | nd | 19.38Ba ± 0.98 | |

| Histamine | A | 55.90 Da ± 4.81 | 34.84Aa ± 2.64 | 34.34Aa ± 1.27 | 44.71Ba ± 1.04 | 49.70Cb ± 0.50 |

| B | 55.65Ca ± 5.93 | 36.36Aa ± 1.45 | 33.94Aa ± 1.47 | 45.85Ba ± 1.99 | 39.83ABa ± 3.50 | |

| C | 53.86Ba ± 6.06 | 46.58ABb ± 1.45 | 46.67ABb ± 2.00 | 45.20ABa ± 5.86 | 38.27Aa ± 2.41 | |

| D | 46.07Aa ± 1.37 | 49.32Ab ± 0.56 | 45.18Ab ± 0.66 | 48.40Aa ± 6.00 | 49.70Ab ± 1.97 | |

| Tyramine | A | 206.42Cb ± 12.05 | 137.36Ad ± 3.73 | 167.70Bb ± 2.11 | 177.0Bb ± 12.85 | 172.85Bb ± 7.00 |

| B | 123.56Ba ± 19.70 | 93.50Aa ± 0.83 | 127.69Ba ± 13.68 | 127.01Ba ± 7.94 | 136.42Ba ± 5.21 | |

| C | 131.70Ba ± 3.99 | 116.97Ac ± 1.38 | 123.35Aa ± 10.16 | 132.21Ba ± 3.07 | 130.14Ba ± 8.61 | |

| D | 129.84Ba ± 10.79 | 100.90Ab ± 6.22 | 130.51BCa ± 4.22 | 123.80Ba ± 5.60 | 142.00Ca ± 14.00 |

ADifferent matching upper-case letters in the same line mean significant differences between different months according to DMRT (P < 0.05)

aDifferent matching lower-case letters in the same column mean significant differences between the sample groups according to DMRT (P < 0.05)

Fig. 1.

HPLC chromatogram of standard biogenic amines (Peaks: 1, putrescine; 2, cadaverine; 3, spermidine; 4, 1,7-diaminoheptane (IS); 5, spermine; 6, histamine; 7, tyramine)

Fig. 2.

HPLC chromatogram of 2% PSE fortified tarhana at 0th month (Peaks: 1, putrescine; 2, cadaverine; 3, spermidine; 4, 1,7-diaminoheptane (IS); 5, spermine; 6, histamine; 7, tyramine)

Putrescine and cadaverine concentrations were found in high amounts in tarhana samples. Mean putrescine and cadaverine concentrations were found as 170.0 and 177.2 mg/kg in control samples, respectively. Putrescine concentration was in the range of 101.95–170.04 mg/kg. In the literature, the range of putrescine content for tarhana was reported as: 6.9–267.1 mg/kg (Keşkekoğlu & Uren 2013). Cadaverine concentration was found between 101.65 and 177.17 mg/kg. In compliance with our study, Keşkekoğlu and Uren (2013) pointed out that cadaverine formation was various for different tarhana samples and cadaverine may occur again after its degradation.

Histamine, spermine and spermidine concentrations were found less than putrescine and cadaverine concentrations in tarhana samples. Histamine content of tarhana was detected between 33.94 and 55.90 mg/kg. Ozdestan and Uren (2013) reported histamine content of home-made tarhana samples between 6.3 and 115.9 mg/kg similar to our results. The spermine content of tarhana was changed from non detectable values to 32.07 mg/kg. The spermidine content of tarhana samples was ranged from non detectable values to 21.93 mg/kg. Ozdestan and Uren (2013) reported that the spermidine concentrations of tarhana samples varied from 12.0 and 45.6 mg/kg which were in agreement with our results. Spermine and spermidine have potential to increase the toxicity of histamine and tyramine (Rodriguez et al. 2014). Therefore, the level of spermine and spermidine in the foods should be limited.

PSE addition caused a significant decrease in putrescine, cadaverine and tyramine concentrations in tarhana samples (P < 0.01). 1% PSE addition caused significant decrease in putrescine concentration (P < 0.01) but it caused no significant decrease in cadaverine and tyramine concentrations (P < 0.01) in the 0th month. 2% PSE addition caused a significant decrease in cadaverine and tyramine concentrations (P < 0.01). The highest total biogenic amine concentration was belong to the control samples and the lowest was belong to 2% PSE fortified samples. During storage, total biogenic amine content of the control tarhana sample was the highest and that of all samples’ total biogenic amine content decreased during the first 2 months and increased slightly in the next months of storage. Pearson correlation test showed positive significant correlations between putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine, histamine, tyramine concentrations and total biogenic amine concentrations (P < 0.05). This correlation suggests that there might be one specific microorganism being responsible for the formation of all biogenic amines. On the other hand, spermine and total biogenic amine concentrations had no significant correlation between each other (P > 0.05).

Limit of detection for all biogenic amines used in this study was 0.5 mg/kg or less, except for tyramine, which had a limit of detection value of 2.5 mg/kg (Ozdestan & Uren 2009). Recovery rates of the tarhana were found between 87.0 and 94.6%. According to the statistical analyses, positive significant correlation was found between total biogenic amine content and pH values (P < 0.05). pH values of tarhana samples were found between 3.61 and 4.12. Silla-Santos (1996) gave as 4.0–5.5 for optimum pH for biogenic amine formation and mentioned that low pH caused the stop of microbial activation (Silla-Santos 1996). So our result was in agreement with this knowledge. Negative significant correlation was determined between total biogenic amine content and acidity values (P < 0.05). Negative significant correlations were shown between putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine, histamine, tyramine, total biogenic amine concentrations and TPCC by Pearson test (P < 0.05). According to this result, samples with the highest TPCC had the lowest total biogenic amine content. A negative significant correlation was detected between inhibition % values (antioxidant activity) and total biogenic amine content (P < 0.05). As a result, antioxidant activity and TPCC increased with the addition of PSE similar as the results of Keskekoglu and Uren (2014).

Biogenic amine content of foods is important from the point of food quality, shelf life and public health. Tarhana is a dry food but according to the results, some biogenic amines’ concentrations increased during the storage period. So determination of biogenic amine content of some fermented-dry foods during their shelf life is important. Total biogenic amine content of samples was found between 398.25 and 632.75 mg/kg. These values were found under the limit value of 1000 mg/kg given by Silla-Santos (1996). Histamine concentrations were below the maximum permissible value (< 100 mg/kg). Concentration of tyramine, which is the most abundant biogenic amine in tarhana, was found in between 103.01 and 218.48 mg/kg. The concentrations of the biogenic amines decreased for the two months of storage possibly due to the activities of biogenic amine degrading bacteria. Lonvaud-Funel (2001) reported that some strains of bacteria were able to degrade biogenic amines, which were unable to decarboxylate amino acids. On the other hand, contents of some biogenic amines increased at the end of the storage period compared to the 2 month stored samples because of the microorganisms cultivated during the storage period. Biogenic amine contents of tarhana samples were found to be different at the end of the storage. These differences were normal as ingredients and original bacterial status might affect biogenic amine levels of the product. There were significant differences between biogenic amine contents of control samples and PSE added samples (P < 0.05). PSE added samples had the less amount of biogenic amine compared with control samples. 1% PSE addition in tarhana samples caused a significant decrease in putrescine concentration and 2% PSE addition caused a significant decrease in cadaverine and tyramine concentrations. Total biogenic amine content of tarhana samples (0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%) were found as 894.7 mg/kg, 569.67 mg/kg, 514.52 mg/kg and 424.60 mg/kg, respectively. Chiacchierini et al. (2006) reported that consumption of biogenic amines more than 40 mg per meal could have toxic effects. According to this information, intake of more than 60 g tarhana per meal could be toxic. In addition, this level is very high compared to the traditional consumption level (20 g of tarhana required for 1 bowl of soup) of people per meal.

Ozdestan and Uren (2013) reported the average total biogenic amine content of 15 homemade tarhana samples as 255.97 mg/kg. Similar to the results of this study, tyramine was also found as the most abundant biogenic amine in their study. The amounts of biogenic amines were not the same because the production methods and the raw materials of tarhana change according to the region in Turkey. Three different types of tarhana were produced by different formulations and total dry matter, pH, total acidity, LAB counts and biogenic amine contents of these samples were determined during fermentation and storage periods by Keşkekoğlu and Uren (2013). Tyramine, putrescine and cadaverine were the major biogenic amines. Spermidine, spermine and histamine were found irregularly and at very low concentrations as proportional with our results. Effect of natural (green tea extract, Thymbra spicata oil) and synthetic antioxidants (buthylatedhydroxytoluene, BHT) on the quality of sucuk were studied during the ripening periods by Bozkurt (2006). They reported that the use of antioxidants decreased the concentration of tyramine. Besides, the use of green tea extract in sucuk samples resulted in the lowest tyramine concentration. Therefore, it can be inferred that natural antioxidants were more effective on inhibition of biogenic amine formation than synthetic ones. We used natural antioxidant in this study and obtained effective results in agreement with Bozkurt (2006)’s results.

Conclusion

As a result, PSE addition caused an increase in total phenolic compound content and antioxidant activity of tarhana samples. In addition, total biogenic amine content decreased by the addition of PSE. Total BA contents of all tarhana samples were lower than the toxic limits. Therefore, consumption of tarhana is safe for normal people, but it may present a health risk for individuals being treated with amino oxidase inhibitors. With regard to the results of total phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and total biogenic amine content it can be suggested to consume tarhana in two months. Usage of PSE up to 2% was acceptable for tarhana, however higher ratios may lead to undesired taste. PSE fortified tarhana can be produced commercially. In the next studies, different antioxidants can be used for the control of total biogenic amine content of foods and functional fermented foods can be produced such as PSE fortified tarhana.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to Ege University Scientific Research Council for their financial support (Project number: 2014-MUH-009).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alnouri FF, Duitschaever CL, DeMan JM. The use of pure cultures for the preparation of kushuk. Can Int Food Sci Technol J. 1974;7:228–229. doi: 10.1016/S0315-5463(74)73909-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez MA, Moreno-Arribas MV. The problem of biogenic amines in fermented foods and the use of potential biogenic amine-degrading microorganisms as a solution. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2014;39:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC Methods . Official methods for analysis. 15. Arlington: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgiçli N, Elgün A, Türker S. Effects of various phytase sources on phytic acid content mineral extractability and protein digestibilityof tarhana. Food Chem. 2006;98:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.05.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt H. Utilization of natural antioxidants: green tea extract and Thymbra spicata oil in Turkish dry-fermented sausage. Meat Sci. 2006;73:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams W, Cuveller M, Berset C. Use of free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 1995;28:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Çalışkan Koç G, Özçıra N. Chemical composition, functional, powder, and sensory properties of tarhana enriched with wheat germ. J Food Sci Technol Mys. 2019;56(12):5204–5213. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03989-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli D, Centonze D, Palermo C, Quinto M, Rotunno T. An interference free amperometric biosensor for the detection of biogenic amines in food products. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23:640–647. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiacchierini E, Restuccia D, Vinci G. Evaluation of two different extraction methods for chromatographic determination of bioactive amines in tomato products. Talanta. 2006;69:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Değirmencioğlu N, Gürbüz O, Herken EN, Yurdunuseven Yıldız A. The impact of drying techniques on phenolic compound, total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of oat flour tarhana. Food Chem. 2016;194:587–594. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbaş M, Uslu MK, Erbaş MO, Certel M. Effects of fermentation and storage on the organic and fatty acid contents of tarhana, a Turkish fermented cereal food. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;19:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2004.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fadavi A, Barzegar M, Azizi MH, Bayat M. Physicochemical composition of 10 pomegranate cultivars (Punica granatum L.) grown in Iran. Food Sci Technol Int. 2005;11:113–119. doi: 10.1177/1082013205052765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folkertsma B, Fox PF. Use of the Cd-ninhydrin reagent to ases proteolysis in cheese during ripening. J Dairy Sci. 1992;59:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Deng Q, Xiao J, Xie B, Sun Z. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and preventing DNA damage effect of pomegranate extracts by chemiluminescence method. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:3134–3140. doi: 10.1021/jf063443g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanoglu S, Ibanoglu E, Ainsworth P. Effect of different ingredients on the fermentation activity in tarhana. Food Chem. 1999;64:103–106. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00071-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jing P, Ye T, Shi H, Sheng Y, Slavin M, Gao B, Liu L, Yu L. Antioxidant properties and phytochemical composition of China-grown pomegranate seeds. Food Chem. 2012;132:1457–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalac P. Health effects and occurrence of dietary polyamines: a review for the period 2005–mid 2013. Food Chem. 2014;161:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keşkekoğlu H, Uren A. Formation of biogenic amines during fermentation and storage of tarhana: a traditional cereal food. Qual Assur Saf Crop Food. 2013;5(2):169–176. doi: 10.3920/QAS2012.0150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keskekoglu H, Uren A. Inhibitory effects of pomegranate seed extract on the formation of heterocyclic aromatic amines in beef and chicken meatballs after cooking by four different methods. Meat Sci. 2014;96(4):1446–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange J, Wittmann C. Enzyme sensor array for the determination of biogenic amines in food samples. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2002;372:276–283. doi: 10.1007/s00216-001-1130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonvaud-Funel A. Biogenic amines in wines: role of lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;199(1):9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nout MJR. Fermented foods and food safety. Food Res Int. 1994;27(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/0963-9969(94)90097-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir S, Göçmen D, Kumral AY. A traditional Turkish fermented cereal food: tarhana. Food Rev Int. 2007;23:107–121. doi: 10.1080/87559120701224923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdestan O, Uren A. A method for benzoyl chloride derivatization of biogenic amines for high performace liquid chromatography. Talanta. 2009;78(4–5):1321–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdestan O, Uren A. Biogenic amine content of tarhana: a traditional fermented food. Int J Food Prop. 2013;16(2):416–428. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2011.551867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MBR, Carneiro C, Feijó MB, Júnior CAC, Mano SB. Bioactive amines: aspects of quality and safety in food. Food Nutr Sci. 2014;5(2):138–146. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby AR. Significance of biogenic amines to food safety and human health. Food Res Int. 1996;29(7):675–690. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(96)00066-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silla-Santos MH. Biogenic amines: their importance in foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;29:213–231. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(95)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamime AY, Muir DD, Khaskheli M, Barclay MNI. Effect of processing conditions and raw materials on the properties of Kishk 1. Compositional and microbiological qualities. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2000;33:444–451. doi: 10.1006/fstl.2000.0686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu BJ, Chang SKC. A comparative study on phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities of legumes as affected by extraction solvents. J Food Sci. 2007;72:159–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2006.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeğin S, Uren A. Biogenic amine content of boza: a traditional cereal-based, fermented Turkish beverage. Food Chem. 2008;111(4):983–987. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]