Abstract

The influences of coagulation conditions on the characteristics of tofu have been investigated by many studies, with limited perspectives on the utilization of organic acid coagulants. Hence, this research aimed to study the psychochemical and functional properties of tofu coagulated by bilimbi (Averrhoa bilimbi) and lime (Citrus aurantifolia) juices. The highest tofu protein content was quantified for tofu prepared with 20% bilimbi and 5% lime juices, as much as 52.11 and 52.03% (DW), respectively. The corresponding yield was 73.46 and 69.17%. The hardness (155.98 g), gumminess (116.45 g), and chewiness (112.69 g) of treated tofu were found significantly higher than commercial tofu (p < 0.05). Total phenolic content of commercial tofu was about 370.09 μg GAE/g sample (DW). This value was significantly higher than that of treated tofu (p < 0.05). However, the antioxidant activity of the commercial tofu was lower than tofu coagulated with fruit juices. Based on SDS-PAGE analysis, protein band for 11S fraction of tofu coagulated by bilimbi and lime juices were thicker than that of commercial tofu. These small molecular weight peptides might contribute for higher antioxidant activities of tofu coagulated by bilimbi and lime juices. Conclusively, bilimbi and lime juices are potent natural acid coagulants for enhancing the physicochemical and functional properties of tofu.

Keywords: Antioxidant, Bilimbi, Functional property, Lime, Peptides, Tofu

Introduction

Tofu is commonly found, and consumed in Indonesia as part of the daily diet. Amongst others, proteins and antioxidants are two important components present in tofu (Zhao et al. 2020). Soybean-based tofu has approximately 70% primary storage proteins (i.e., glycinin (11S) and β-conglycinin (7S)) (Joo and Cavender 2020). According to Syah et al. (2015), the conditions of tofu processing inevitably influenced the 11S/7S storage protein ratio. This ratio has influences on hardness and gumminess of the formed soy curds. As suggested in the previous studies, the antioxidant activities of tofu are mainly ascribed to the soybean isoflavones, such as genistein, daidzein, and glycitein (Kridawati et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2019). However, the washing procedure might cause the excessive loss of the isoflavone (as high as 44%) during tofu preparation (Wang and Murphy 1996).

Protein coagulation is fundamental in tofu preparation. The coagulation depends on the complex interaction of many variables, including raw materials and processing conditions (Joo and Cavender 2020). When a salt coagulant such as CaCl2 is added to the prepared soymilk, the metal ion Ca2+ will form bridges with the negatively charged protein. The coagulates are formed due to cross-linking between the cations and the proteins (Wang et al. 2018). Mechanistically, calcium ion binds to carboxyl residue of aspartate or glutamate, and also to imidazole group of histidine that can accelerate curd formation (Chang 2005). On the other hand, an acid coagulant causes soy protein precipitation by lowering soymilk pH close to isoelectric point (pI). Two important phenomena in acid coagulation have been reported, such as protein denaturation and hydrophobic coagulation (Joo and Cavender 2020). Hydrophobic functional groups of protein are naturally located in the inner region of the protein structure. The application of heat (and in the presence of acid) can cause these functional groups moving to the outer part of the protein structure, and thus, leads to protein denaturation (Cao et al. 2017). Although denatured protein is negatively charged, the total net charge of the protein is close to zero because of the presence of proton from acid addition. Less hydrophilic–hydrophilic interaction between protein molecules and water, and the occurrence of protein aggregation due to hydrophobic interaction between neutral proteins entails in reduction of protein solubility (Kohyama et al. 1995).

The applications of natural acid coagulants for tofu production have been reported elsewhere (Rekha and Vijayalakshmi 2013; Sanjay et al. 2008). The acidic fruits such as Tamarindus indica (tamarind), Garcinia indica (kokum), Passiflora edulis (passion fruit), Citrus limonum (lemon) and Phyllanthus acidus (gooseberry) have been used to successfully produce tofu (Rekha and Vijayalakshmi 2013). Tofu coagulation by the addition of natural acid has been shown to have a higher antioxidant activity and protein content as compared with the one that was coagulated with gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) (Rekha and Vijayalakshmi 2010). It is worth mentioning that bioconversions of isoflavone glucosides (daidzin and genistin) into their corresponding bioactive aglycones (daidzein and genistein) were observed for tofu prepared by natural acid coagulants (Rekha and Vijayalakshmi 2013).

As a tropical country, Indonesia has been enjoying its richness in natural resources. There are various acidic fruits, which are potent as sources of acid coagulants. Averrhoa bilimbi (bilimbi) and Citrus aurantifolia (lime) are commonly found in Indonesian agricultural sector. The acidic tastes of bilimbi and lime are originated from their acid compounds. Acids identified in bilimbi are grouped as aliphatic acids, such as hexadecanoic acid, 2-furaldehyde, and octadecenoic acid (Alhassan and Ahmed 2016). Other acids are also found in bilimbi, such as glutamic acid, succinic acid (Istiqamah et al. 2019) and oxalic acid (Lim 2016). Oxalic acid is the highest acid identified in bilimbi, and may contribute to the low pH value (i.e., 0.9–1.5) of the bilimbi juices (Lim 2016). Several acids found in lime are citric acid, malic acid, lactic acid, ascorbic acid, and small amounts of oxalic acid and tartaric acid (Nour et al. 2010).

To date, limited studies have focused on tofu production using both acidic fruits (bilimbi and lime) as coagulants. The measured parameters were also narrowed only to the yield, moisture content, and protein content of the tofu (Maharani and Kurniawati 2012). Some previous studies showed that natural acid coagulants were able to increase the antioxidant activity, sensory acceptance, and also improve texture, yield, and retention capacity of the produced tofu (Rekha and Vijayalakshmi 2010; Sanjay et al. 2008). In the present study, the juices of bilimbi and lime were used for producing tofu with beneficial characteristics, either physicochemical or functional. Three levels of concentration for each coagulant was determined to see their influences on both physicochemical and functional properties (i.e., antioxidant capacity) of the tofu. For the elaboration of tofu protein functionalities, such analytical method for the separation of tofu protein mixture based on molecular masses in an electric field (SDS-PAGE) was also conducted.

Materials and methods

Materials

The genetically modified soybean was purchased from Koperasi Tempe Indonesia (KOPTI). Bilimbi and lime were purchased in bulk form (maturity level of 70–80%) from traditional market in Bogor, Jawa Barat. The ascorbic acid standard (A1300000), tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (252859), glycine (G8898), glycerol (G2025), bromophenol blue (114391), glacial acetic acid (1005706), acrylamide (A3553), 2-mercaptoethanol (M3148), N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMED) (T9281), 2,2-Di(4-tert-octylphenyl)-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (257621), Brilliant Blue R (271816), bis-acrylamide (A3449), and Folin and Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent (F9252) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Singapore). The ExactPro pre-stained protein ladder was purchased from 1st BASE Pte Ltd., Singapore. All other reagents, such as phenolphthalein indicator, red methyl, blue methyl, absolute methanol, HCl, H2SO4, DPPH, K2SO4, H3BO3, Na2S2O3.5H2O, and NaOH were analytical grade, and were purchased from Toko Kimia Setia Guna located in Pabaton, Bogor, Jawa Barat.

Preparation of fruit juices

Bilimbi and lime were cut to pieces and trimmed from waste. The fruit juices were prepared using a fruit rasper (Hovex raspers, PT. Wahana Hijau, Inti Teknik). Fruit juices were filtered using 60 mesh filtercloth (pore size = 250 µm) to remove suspended materials in the juices. After the filtration, the juices were kept in amber bottles, placed inside a refrigerator (4–8 °C) prior to use. In order to minimize variation in fruits, the preparation was done once, and sufficient for all the experiments designed.

Titratable acidity and pH measurement of fruit juices

Measurement of pH was done using Orion Star™ A211 pH Benchtop Meter (Thermo Scientific™). For determining the titratable acidity of the juices, phenolphthalein 1% was used as color indicator. Sample was titrated using 0.1 M NaOH until the color of solution reach a stable slightly-red color.

Titration curve of fruit juices

Titration curves of the juices were conducted according to Harvey (2000) with minor modification. Fruit juices were filtered using whatman No.1 (retention characteristic: particle of 6.0 µm) to remove the interfering suspended solids. Fruit juices as much as 25 mL was titrated using 0.4 M NaOH. Measurement of pH value was done prior and during the titration until the juice was in basic condition, and the pH increase started to slow down. During the titration, pH value was recorded in every 0.5 mL of NaOH titrated.

Buffer capacity analysis of fruit juices

Buffer capacity () was calculated from pH titration curve as described above. The equivalent points of bilimbi and lime juices were determined by first derivatization and second derivatization from each corresponding titration curve. The number of acid’s mole was calculated using equivalent point obtained from the titration. Dissociation constant (Ka) was calculated using stoichiometry approach (Harvey 2000). After Ka was determined, molarity of buffer, and buffer capacity (β) were determined using the equations below (Eqs. 1–3):

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where n, mol of strong acid or strong base; Kw, water ionization constant; β, buffer capacity; Cbuf., molarity of buffer, and Ka, dissociation constant.

Soymilk preparation

Soymilk was prepared according to Chang (2005) with minor modifications. A 600 g of dried soybean (moisture content was about 14%) was washed, and soaked in water (i.e., with a ratio of water and soybean was 9:1) for 60 min with a temperature of 90 °C. Soaked soybean was drained, weighed, and grinded for 30 s in the presence of boiling water (90–95 °C) with a ratio of water to soaked soybean of 9:1. Soymilk was obtained by filtering the resulted suspension using 60 mesh filtercloth. The produced soymilk was pasteurised at 95 °C for 25 min with continuous stirring at 80 rpm.

Tofu production and yield measurement

Tofu was prepared according to Jun et al. (2019) with modifications. Initially, frozen juices were thawed at room temperature (25 °C). The concentration of natural acid coagulant was calculated as mass ratio of juices to dry soybean used to prepare soymilk. The ranges of concentrations employed in this study were determined qualitatively and quantitatively. A particular natural acid coagulant concentration was considered in-range qualitatively whenever: (i) soy whey color was cloudy yellow after the addition of coagulant, (ii) the absence of four basic tastes (salty, sweet, sour, and bitter), (iii) there was no coagulant odor detected, and (iv) curd formation was evident (Chang 2005). Moreover, coagulant concentration was in-range quantitatively when the protein content of tofu in the dry basis was higher or close to commercial one (~ 40%). Quantitative observations were done latter, and used for correcting qualitative observations. Eventually, there were three levels of coagulant concentrations for each lime and bilimbi juices that were considered as in-range, such as 5, 6, and 7% for lime juice, and 18, 20, and 22%, for bilimbi juice. Tofu started to exhibit acid taste at concentration above 7% of lime juice or 22% of bilimbi juices. Curd formation did not occur at concentration below 5% of lime juice or 18% of bilimbi juice.

Each natural acid coagulant was added to soymilk at temperature of 85 ± 1 °C, stirred at 80 rpm for 20 min. In this study, the influence of coagulating temperature was not part of the interest. The produced curd and whey were separated by means of filter cloth. Curd was wrapped in a cheesecloth and was positioned inside the tofu molder. Curd was pressed by a load as much as 25.0 g/cm2. The resulted tofu and whey were stored in refrigerator maximum 24 h at 4–8 °C prior to analyses. Tofu yield was calculated based on the following equation (Eq. 4):

| 4 |

where m1, weight of produced tofu (g) and m2, weight of dry soybean (g)

Moisture, protein content, and color analysis

The quantification of moisture (i.e., gravimetric analysis) and protein content (i.e., Kjeldahl method) of the produced tofu were according to the official methods (AOAC 2006). Color measurement was done using Hunter-color-system with Chromameter (CR-300 Minolta, Konica Minolta Sensing Americas, Inc.). Each parameter was analysed in triplicate.

Texture analysis

Tofu was cut into 10 pieces in cube shape with a volume of 1.0 cm3. Tofu texture was analyzed with texture analyzer TA-XT2 (Stable Micro Systems, United Kingdom). The parameters measured were hardness, cohesiveness, springiness, gumminess, and chewiness. The probe used was SMS P/35. The measurement conditions were set as following: test speed = 1.5 mm/sec, ruptured test distance = 1.0%, distance = 30%, force = 205 g, trigger force = 5 g and unit distance = % strain. Each parameter measured in ten replicate, giving 30 samples were tested for each condition.

DPPH free radical-scavenging assay

The extraction of the antioxidantive compounds from tofu was according to Annegowda et al. (2012), and the antioxidant capacity was measured using DPPH free radical-scavenging assay (Sharma and Bhat 2009; Sitanggang et al. 2020). A 1.0 g sample was macerated in 10 mL of absolute methanol for 30 min in Branson 8510 sonicator (LabX, Canada). Suspension was filtered using filter paper Whatman No. 1. The ascorbic acid was used to construct the standard curve with concentrations of 5–30 μg/mL in absolute methanol (coefficient of determination, r2 = 0.9953). For making DPPH stock solution, DPPH was dissolved in methanol to reach concentration of 0.790 mM. A 0.5 mL of sample extract and 5.0 mL of DPPH stock solution were put into the test tube, and considered as sample. Whereas for the blank, 0.5 mL of methanol was used to replace the juices. Every tube was vortexed, and incubated in dark room for 30 min under room temperature prior to measurement. The absorbances of standard solutions and samples were measured using Shimadzu UVmini-1240 (Shimadzu Europe) at 517 nm. The antioxidant activity was expressed as ascorbic acid equivalent antioxidant capacity (AEAC) and calculated based on following equation (Eq. 5):

| 5 |

where Cas, concentration of ascorbic acid (mg/mL); V, volume of extracted sample (mL); DR, dilution ratio and W, weight of sample (DW, g).

Total phenolic content

The extraction of phenolic compounds was according to Mastura et al. (2017), and the total phenolic content was measured following a procedure reported by (Vermerris and Nicholson 2006) with minor modifications. The total phenolic content was determined for both produced tofu and the natural acid coagulants (bilimbi and lime juice). A 2.0 g of tofu was macerated in 6.0 mL of absolute methanol for 30 min in Branson 8510 sonicator (LabX, Canada). The suspension was then filtered using filter paper Whatman No.1. For fruit juices, 3.0 mL of juices were added with 6.0 mL of absolute methanol. A 0.25 mL of sample solution and 5.0 mL of 7% Na2CO3 were mixed, and incubated for 5 min under room temperature. A 0.25 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent was added to mixture. Finally, it was incubated in a dark room for 30 min at 25 °C. A standard curve was made at concentrations of 150–400 μg/mL of gallic acid in distilled water (coefficient of determination, r2 = 0.9968). The absorbance of standard solutions and samples were measured using Shimadzu UVmini-1240 (Shimadzu Europe) at 750 nm. Total phenolic content was expressed in gallic acid equivalent (GAE), and calculated based on following equation (Eq. 6):

| 6 |

where Cga, concentration of gallic acid (mg/mL); V, volume of extracted sample (mL); DR, dilution ratio and W, weight of sample (DW, g).

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis

Tofu was initially defatted according to Rydberg et al. (2004). Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.4 was used to dissolve tofu protein (Mujoo et al. 2003). The SDS-PAGE analytical procedures followed within this study was according to Harris (2015). Separating gel concentrations used were wide range, with a range of molecular weights of the protein from 20 to 260 kDa (12% T; 2.7% C). Herein, T states the total concentration of both acrylamide and bis-acrylamide, while C indicates bis-acrylamide concentration based on acrylamide amount (w/w). A 40 µL of the protein sample was mixed with 10 μL tris–HCl pH 8.4 in a 1.5 mL tube. The tube was heated in boiling water for 5 min for denaturing the protein. As much as 15 µL of the resulted solution were injected into the well. The protein markers were injected as well according to the supplier’s procedures. The horizontal electrophoresis apparatus (Bio-Rad, Singapore) was installed according to the manufacturer’s guide. The device was set to a constant voltage of 70 volts. After electrophoresis was complete, the gel was immersed in dye solution (0.1% w/v Brilliant blue R-250, 45% v/v methanol, 10% v/v glacial acetic acid, and 45% v/v distilled water) for 1 h in a New Brunswick™ Innova® 2300 rotary shaker (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). The stained gel was rinsed with distilled water, heated in boiling water for 5 min until the protein bands were clearly visible on the polyacrylamide gel (Harris 2015). For determination of molecular weight of peptides contained in the samples, a linear regression obtained from the markers was used. The linear regression was a logarithmic function of the marker peptide molecular weight to relative mobility.

Statistical analysis

One Way ANOVA using IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0 was performed on the analytical results. If there were significant differences among the treatments, then further statistical analysis by Duncan Test at p < 0.05 was conducted.

Results and discussion

pH and titratable acidity of the juices

The acidity and titratable acidity of the fruit juices are shown in Table 1. Bilimbi juice was more acidic as indicated by a lower pH value. However, the molarity of acid in lime juice was higher than bilimbi juice. Further observation was carried out related to the titration curve and buffer capacity for both juices.

Table 1.

Titratable acidity and pH of fruit juices

| Fruit juices | pH | Titratable acidity (mL NaOH 0.01 M/100 mL sample) |

|---|---|---|

| Lime | 2.35 ± 0.00 | 1140.00 ± 6.00 |

| Bilimbi | 1.45 ± 0.00 | 0171.50 ± 0.87 |

Titration curve and buffer capacity of fruits juices

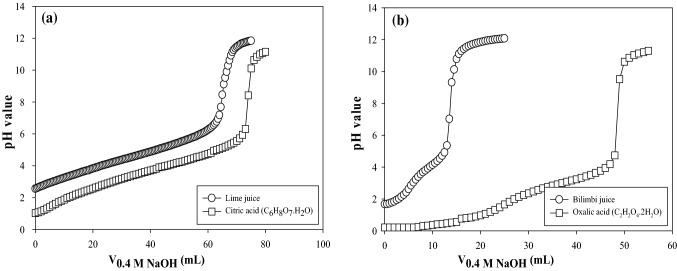

Titration curves of lime and bilimbi juices can be seen in Fig. 1. Small increment of pH in lime juice observed until 63 mL of 0.4 M NaOH titrated, and pH was 6.77. After this point, pH significantly increased from 7.18 to 10.92 by the addition of 4.0 mL of titrant. The pH of bilimbi juice increased slowly as well until the volume of titrant used was around 12 mL (Fig. 1b). The pH then increased sharply from 5.35 to 10.78 with 2.0 mL titrant added. For both juices, the rates of pH change were small again due to alkaline conditions.

Fig. 1.

Titration curves of lime (a) and bilimbi juices (b) and its corresponding dominant acids using 0.4 M NaOH as the titrant

Citric acid monohydrate (0.4 M, C6H8O7.H2O) and oxalic acid dihydrate (0.4 M, C2H2O4·2H2O) were used as standards for titration curves of lime and bilimbi juices, respectively. Lime has been reported to have citric acid as the major acid, whereas for bilimbi, oxalic acid has been reported as the dominant acid (Cho and Lim 2016). From Fig. 1, it can be seen clearly that titration curves of lime and bilimbi juices have similar trends with the standard acids. This confirmation was of importance to highlight that other acids in lime or bilimbi juices had insignificant effect on the trend of titration curve.

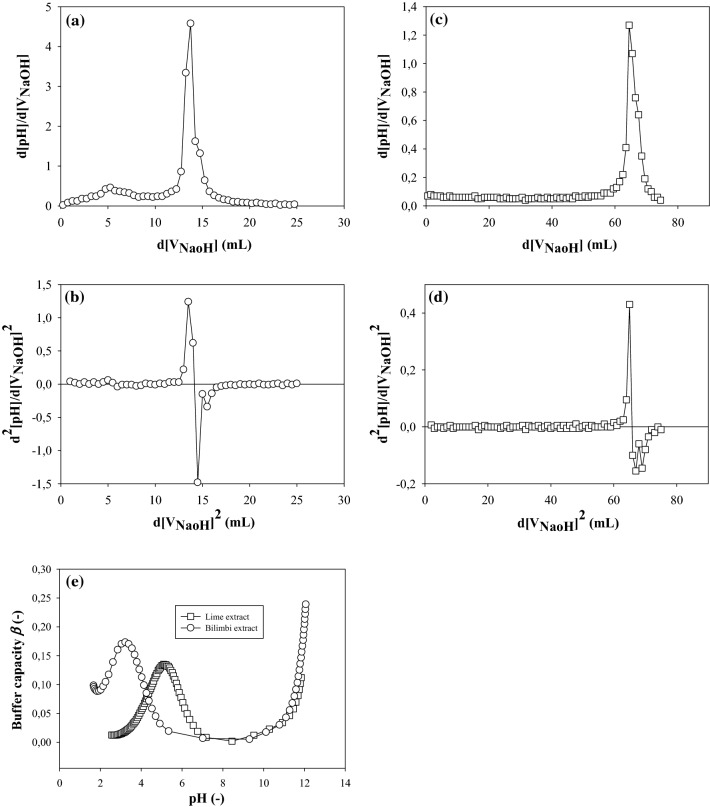

The equivalence points of lime and bilimbi juice titration were determined by first derivatization (i.e., through observation of the maximum value) or second derivatization (i.e., intercession with ordinate) (see Fig. 2). Based on Fig. 2, to reach the equivalence points for lime and bilimbi juices, as much as 64.8 and 13.75 mL of 0.4 M NaOH were used, respectively. The corresponding pH values were 8.45 and 8.0, respectively. The molarity of acid for each juice was determined based on the corresponding titrant volumes needed to reach equivalence point (i.e., 1.063 and 0.226 M, respectively for lime and bilimbi juices). The molarity of hydronium ion (H3O+) of each juice was calculated based on the pH value of the juice prior to titration. Finally, using simple stoichiometry approach (Harvey 2000), and by employing Eqs. (1) and (3), the buffer capacity of each fruit juice was determined as shown in Fig. 2(e).

Fig. 2.

The first and second derivative of pH changes against changes in titrant volume for bilimbi (a, b) and lime juice (c, d); and buffer capacity (β) of lime and bilimbi juice (e)

The highest buffer capacity (β) in Fig. 2 (e) was shown in acidic region for both juices. The buffer capacity also increased significantly after equivalence point, because addition of strong base in alkaline conditions had little effect on pH increase (Harris 2015). The total buffer capacity (βtot) was the summation of β-value at inflection point until reaching the equivalence point. βtot for bilimbi juices was 2.42, whereas for lime was 4.50. Hereby, lime was more resistant to pH change than bilimbi juice. Based on these results, it was confirmed that concentrations of bilimbi juices needed for coagulating soymilk were therefore higher compared to the lime juices.

Yield, whey pH, moisture and protein content

The highest yield of tofu was obtained at 7% lime juice as seen in Table 2, and the other treatments showed insignificant difference amongst them at p > 0.05. The differences in yield might be due to the varied acid concentrations, acid homogeneities presence during coagulations, and product leftover in processing utilities. Additionally, the moisture content of the treated tofu were not significantly different. Yields of tofu prepared with natural acid coagulant, such as lemon, tamarind, garcinia, gooseberry and passion fruit ranged from 15 to 21% (Rekha and Vijayalakshmi 2010). Within this study, the yield of treated tofu ranged from 70 to 83%. According to Rekha and Vijayalakshmi (2010), tofu yield was calculated as weight ratio of fresh tofu obtained to soy milk used for its preparation. This calculation is different from the one used in this study, as shown in Eq. (4), thus, the results were not comparable.

Table 2.

Physicochemical characteristics of tofu and whey (treated and commercial)

| Treatment | Yield (%) | Whey pH | Moisture content (%) | Protein content (%) | Whey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brightness (L) | Red (a) | Yellow (b) | |||||

| Commercial | – | 5.15 ± 0.61a | 79.17 ± 0.75a | 41.81 ± 1.37a | – | – | – |

| Bilimbi conc. (%) | 18 | 69.11 ± 4.88a | 5.67 ± 0.12b | 75.21 ± 1.49a | 50.16 ± 2.70b | 53.95 ± 1.49a | − 1.72 ± 0.44ab |

| 20 | 73.46 ± 0.40a | 5.61 ± 0.09b | 77.31 ± 1.49a | 52.11 ± 2.04b | 55.16 ± 1.33a | − 1.42 ± 0.11ab | |

| 22 | 75.34 ± 5.58a | 5.54 ± 0.06ab | 76.26 ± 4.50a | 51.60 ± 0.70b | 54.76 ± 1.39a | − 1.14 ± 0.45b | |

| Lime conc. (%) | 5 | 69.17 ± 5.18a | 5.62 ± 0.06b | 75.45 ± 2.01a | 52.03 ± 0.90b | 56.48 ± 2.09a | − 1.90 ± 0.35a |

| 6 | 73.89 ± 4.15a | 5.52 ± 0.01ab | 77.28 ± 0.74a | 49.47 ± 1.45b | 62.18 ± 2.08c | − 1.92 ± 0.48a | |

| 7 | 83.00 ± 1.86b | 5.38 ± 0.06ab | 75.70 ± 0.71a | 44.43 ± 3.76a | 59.32 ± 0.56b | − 2.12 ± 0.21a | |

| Treatment | Yield (%) | Tofu | Texture | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brightness (L) | Red (a) | Yellow (b) | Hardness (g) | Cohesiveness (%) | Springiness (%) | Gumminess (g) | Chewiness (g) | |||

| Commercial | – | 72.18 ± 4.40abc | 0.66 ± 0.42a | 11.07 ± 1.57a | 155.98 ± 21.22a | 0.73 ± 0.20a | 0.97 ± 0.02a | 116.45 ± 44.22a | 112.69 ± 41.93a | |

| Bilimbi conc. (%) | 18 | 09.21 ± 0.81a | 72.73 ± 2.55abc | 0.92 ± 0.08a | 14.09 ± 0.55b | 559.10 ± 98.45bc | 0.82 ± 0.01a | 0.99 ± 0.05a | 459.92 ± 88.66bc | 457.44 ± 95.60bc |

| 20 | 10.99 ± 0.78a | 69.16 ± 0.36ab | 0.82 ± 0.29a | 13.17 ± 0.35b | 487.01 ± 61.20b | 0.84 ± 0.00a | 0.96 ± 0.01a | 408.25 ± 50.83b | 391.13 ± 46.31b | |

| 22 | 11.40 ± 2.14a | 74.51 ± 0.68bc | 0.63 ± 0.39a | 13.57 ± 0.61b | 525.10 ± 68.06bc | 0.82 ± 0.00a | 0.97 ± 0.01a | 433.12 ± 54.53bc | 418.79 ± 49.94bc | |

| Lime conc. (%) | 5 | 09.38 ± 1.85a | 68.14 ± 3.86a | 1.14 ± 0.15a | 12.96 ± 0.64b | 637.23 ± 32.85c | 0.83 ± 0.00a | 0.96 ± 0.01a | 528.75 ± 26.72 cd | 510.33 ± 32.47 cd |

| 6 | 09.47 ± 1.55a | 70.00 ± 1.41abc | 0.93 ± 0.09a | 12.97 ± 0.69b | 495.33 ± 66.37b | 0.83 ± 0.00a | 0.95 ± 0.05a | 410.90 ± 55.31b | 388.19 ± 49.36b | |

| 7 | 08.64 ± 0.79a | 74.70 ± 3.37c | 1.00 ± 0.17a | 14.09 ± 0.65b | 727.50 ± 50.41d | 0.84 ± 0.00a | 0.98 ± 0.02a | 604.37 ± 38.66d | 592.72 ± 28.49d | |

Value was presented as mean ± S.D. of triplicate measurements, except for texture. Different superscripts in the same column indicate significant different at p < 0.05

As an acid coagulant, the addition of fruit juices reduced the pH of soymilk, reaching isoelectric point (pI) (Poysa et al. 2006). There was a significant difference in pH values between commercial tofu whey and the treated whey. A higher concentration of fruit juice yielded in a lower whey pH which could be explained by the higher amount of hydronium ion (H30+) presence in soy whey (Harvey 2000). Almost all treated tofu had higher protein content (DW) than commercial tofu, except for tofu prepared with 7% of lime juices. This finding is in agreement with Rekha and Vijayalakshmi (2010) where there was an increase in protein content of tofu coagulated with natural coagulants, especially with the juices of garcinia and tamarind. The highest protein content of tofu using bilimbi juice as coagulant was obtained at a concentration of 20% (52.11% DW), whereas for lime juice was at 5% (52.03% DW). The estimated pI of soybean protein found within this research was at range of 5.61–5.62. It was found that coagulation at pI did not obtain the highest tofu yield. Herein, the additional materials that increased tofu yield, i.e., at 7% lime juices, might be due to the presence of fat and carbohydrates. The content of fats and carbohydrates (e.g., fibers) may also vary in tofu depending on the type and concentration of coagulant used, variability of the soybean as well as other processing methods as reported by Yasin et al. (2019). Additionally, the underlining factor that presumably contributed to the different protein concentrations in tofu coagulated with fruit juices could be related to the effect of coagulants on cross linking of glysin and β-conglycinin (Rekha and Vijayalakshmi 2010).

Color and texture analysis of tofu

The lightness of whey amongst bilimbi treatments were not significantly different, while for lime treatments were significantly different, as seen on Table 2. It might be due to the pH change that was sensitive in lime juices. The lowest brightness of tofu was obtained at 5% of lime juices (68.14), and for the highest brightness was at 7% of bilimbi juices (74.70). The red color intensities of all tofu were not significantly different at p > 0.05. The yellow intensities of treated tofu were significantly different compared to commercial one. It has been reported that tofu made from soybean without the presence of lipoxygenase expressed a higher yellow intensity (Torres-Penaranda et al. 2010). Within this study, such lipoxygenase‐free condition was presumably obtained through the soymilk preparation at temperature of more than 90 °C (Anthon and Barrett 2003; Endo et al. 2004). This soymilk preparation temperature was higher than the commercial one, which was only 70 °C. Thus, the yellow intensity of treated tofu was found higher than the commercial one.

For texture analysis, the hardness, gumminess, and chewiness of commercial tofu were lower and significantly different with the treated tofu. The coagulant used for producing commercial tofu was CaSO4·2H2O, in which the tofu had a higher moisture content (see Table 2). Additionally, coagulation using acid has been reported to have tofu with a harder texture (Chang 2005). Tofu produced from acid coagulants had hardness almost fivefold higher than commercial one. Within this study, soy curd was subjected to a load of 25.0 g/cm2, which was different from the preparation of commercial tofu. Rekha and Vijayalakshmi (2013) reported the influence of solid content on tofu hardness when coagulated with calcium sulfate. Increasing in solid content (7–9 oBrix) resulted in the increase of hardness (4–6 N). The hardness of treated tofu in this study was comparable with that of the previous study conducted by Rekha and Vijayalakshmi (2013). The hardness of treated tofu ranged from 500 to 700 g-force or equaled to approximately 5–7 N (conversion factor of 1 gf to N = 0.0098). Amongst bilimbi treatments, there was no significant difference in terms of tofu hardness, gumminess, and chewiness. In lime treatments, although the trend was inconsistence, such significant difference was obtained for hardness, gumminess, and chewiness, respectively.

Antioxidant activity, total phenolic content and SDS-PAGE analysis of tofu

It was observed that both fruit juices contained phenolic content of 60.22 and 78.60 μg GAE/g sample (DW), respectively for bilimbi and lime juice. The phenolic content of tofu produced with 20% of bilimbi juice was found higher than 5% of lime juice. This might be due to a higher amount of bilimbi juice added to coagulate the soymilk. Interestingly, commercial tofu had the highest total phenolic content, up to 370.09 μg GAE/g sample (DW). Besides processing conditions, soybean source and type might also contribute to phenolic content variations in tofu (Szymczak et al. 2017). Organic and inorganic soybeans contain 209 and 156 mg GAE/100 g soybean as reported by Mastura et al. (2017).

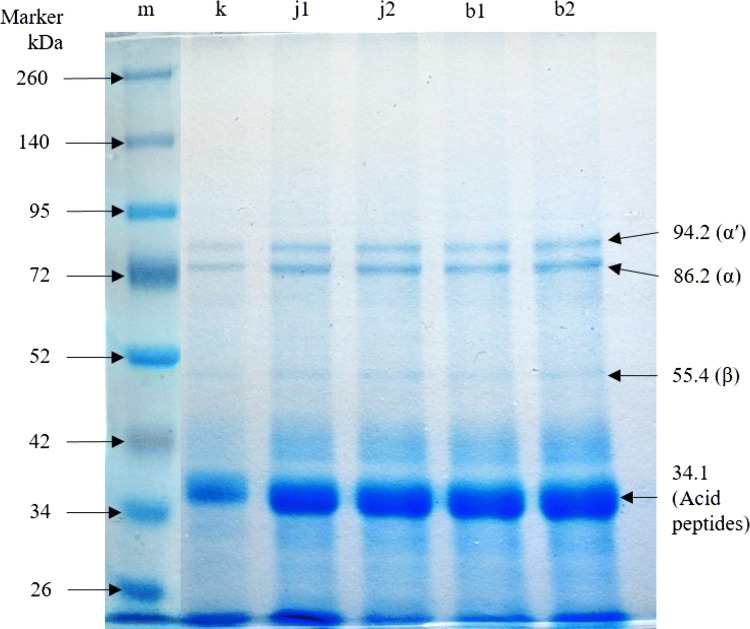

The antioxidant activity of tofu produced using 20% of bilimbi juices was the highest compared to 5% of lime juice and commercial tofu, with 251.82 μg AEAC/g sample (DW) (see Table 3). It is worth-noting that this antioxidant capacity was about 2.5-fold higher than the commercial one. The bioconversion of daidzin and genistin (i.e., isoflavone glucosides) into daidzein and genistein (i.e., corresponding bioactive aglycones) has been reported to also increase antioxidant capacity of the produced tofu using natural acid coagulant (Rekha and Vijayalakshmi 2010, 2013). On the other hand, amino acids in form of peptides could act as endogenous or exogenous antioxidants, and have been considered contributing to total antioxidant activity in cells (Amadou et al. 2010). Histidine, cysteine, methionine, and tyrosine are examples of amino acid which in form of peptides could act as endogenous antioxidants (Xiong 2010). Due to the presence of the acids in natural coagulants, it was presumed the hydrolysis of soybean proteins might be pronounced. Hereby, the resulted peptides and free amino acids were possibly contribute to the increased antioxidant capacities of the treated tofu. As seen in Fig. 3, the protein band of 34.1 kDa was thicker in tofu produced with fruit juices, especially with 20% of bilimbi juice, as compared to commercial one. Moreover, this band was also thicker in comparison with the other bands (i.e., 94.2, 86.2, and 55.4 kDa). Furthermore, proteins with molecular weights of 94.2, 86.2 and 55.4 kDa were also thicker in tofu prepared with natural coagulants compared to commercial one. They were estimated as 7S protein (β-conglycinin) which classified as α', α, and β protein (Hidayat et al. 2011). β-Conglycinin peptide (7S) is important protein in coagulation of tofu (Syah et al. 2015), and has been reported to act as exogenous antioxidant (Xiong 2010). Conclusively, the presence of peptides and free amino acids as a result of protein hydrolysis during the preparation tofu using natural acid coagulants might be also contributed to the higher antioxidant activity of tofu (as seen in tofu prepared with 20% of bilimbi juice). It is worth-mentioning that production of bilimbi and lime are sustainable in Indonesia. Therefore, for commercial applications, it is feasible to produce tofu with higher antioxidant properties coagulated by these natural acid coagulants.

Table 3.

Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of tofu

| Treatments | Antioxidant activity (μg AEAC/g sample) (DW) | Total phenolic content (μg GAE/g sample) (DW) |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial | 105.12 ± 37.85a | 370.091 ± 07.072d |

| Bilimbi juice-added | 60.219 ± 00.886a | |

| Concentration (%) | ||

| 18 | 176.06 ± 26.71b | – |

| 20 | 251.82 ± 14.38c | 345.995 ± 06.934c |

| 22 | 204.05 ± 17.51b | – |

| Lime juice-added | 78.602 ± 00.327a | |

| Concentration (%) | ||

| 5 | 244.74 ± 10.60c | 280.238 ± 27.333b |

| 6 | 132.39 ± 05.53a | – |

| 7 | 143.61 ± 12.87a | – |

Value was presented as mean ± S.D. of triplicate measurements. Different superscripts in the same column indicate significant different at p < 0.05

Fig. 3.

Protein bands of commercial and treated tofu by means of SDS-PAGE. Note: M: protein marker, k: commercial tofu, j1 and j2: tofu coagulated with 5% of lime juice (rep. 1 and 2), b1 and b2: tofu coagulated with 20% of bilimbi juice (rep. 1 and 2)

Conclusion

The use of natural acid coagulants during tofu preparation has benefits for the produced tofu. The highest protein contents and antioxidant activities of tofu made from genetically modified soybean were obtained by coagulating soymilk with 20% (w/w) of bilimbi juice or 5% (w/w) of lime juice. Yellow intensities of tofu prepared with natural acid coagulants were higher than commercial tofu. The hardness, gumminess and chewiness of the treated tofu were higher compared to the commercial one. However, cohesiveness and springiness were found not significantly different amongst commercial and treated tofu. Within this study, the presence of organics acids in natural acid coagulants could facilitate the hydrolysis of parent proteins found in soybean as indicated by SDS-PAGE results, to yield antioxidative peptides and free amino acids.

Acknowledgement

The Indonesian Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education, Republic of Indonesia was acknowledged to support this research partially through scheme WCU Program managed by Institut Teknologi Bandung.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alhassan AM, Ahmed QU. Averrhoa bilimbi Linn.: a review of its ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(4):265–271. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.199342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadou I, Gbadamosi OS, Hui SY, et al. Identification of antioxidative peptides from Lactobacillus plantarum Lp6 fermented soybean protein meal. Res J Microbiol. 2010;5(5):372–380. doi: 10.3923/jm.2010.372.380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Annegowda HV, Bhat R, Min-Tze L, et al. Influence of sonication treatments and extraction solvents on the phenolics and antioxidants in star fruits. J Food Sci Technol. 2012;49(4):510–514. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthon GE, Barrett DM. Thermal inactivation of lipoxygenase and hydroperoxytrienoic acid lyase in tomatoes. Food Chem. 2003;81(2):275–279. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00424-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC (2006) Official methods of the association of official analytical chemist. Washington, DC

- Cao FH, Li XJ, Luo SZ, et al. Effects of organic acid coagulants on the physical properties of and chemical interactions in tofu. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017;85:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. Chemistry and technology of tofu making. In: Hui YH, editor. Handbook of food science, technology, and engineering. 1. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cho D, Lim S. Germinated brown rice and its bio-functional compounds. Food Chem. 2016;196:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo H, Ohno M, Tanji K, et al. Effect of heat treatment on the lipid peroxide content and aokusami (beany flavor) of soymilk. Food Sci Technol Res. 2004;10(3):328–333. doi: 10.3136/fstr.10.328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris DC. Quantitative chemical analysis. New York: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. Modern analytical chemistry. Boston: The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat M, Sujatno M, Sutadipura N, et al. β-Conglycinin content obtained from two soybean varieties using different preparation and extraction methods. HAYATI J Biosci. 2011;18:37–42. doi: 10.4308/hjb.18.1.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Istiqamah A, Lioe HN, Adawiyah DR. Umami compounds present in low molecular umami fractions of asam sunti—a fermented fruit of Averrhoa bilimbi L. Food Chem. 2019;270:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.06.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo KH, Cavender GA. Investigation of tofu products coagulated with trimagnesium citrate as a novel alternative to nigari and gypsum: comparison of physical properties and consumer preference. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JY, Jung MJ, Jeong IH, et al. Effects of crab shell extract as a coagulant on the textural and sensorial properties of tofu (soybean curd) Food Sci Nutr. 2019;7(2):547–553. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohyama K, Sano Y, Doi E. Rheological characteristics and gelation mechanism of tofu (soybean curd) J Agric Food Chem. 1995;43(7):1808–1812. doi: 10.1021/jf00055a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kridawati A, Rahardjo TB, Hardinsyah W, et al. Comparing the effect of tempe flour and tofu flour consumption on estrogen serum in ovariectomized rats. Heliyon. 2019;5(6):e01787. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim TK. Edible medicinal and non-medicinal plants. Netherlands: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maharani A, Kurniawati DNA. Pengaruh jenis agen pengendap alami terhadap karakteristik tahu. J Teknol Kim Ind. 2012;1(1):528–533. [Google Scholar]

- Mastura YH, Hasnah H, Dang TN. Total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of beans: organic vs inorganic. Int Food Res J. 2017;24(2):510–517. [Google Scholar]

- Mujoo R, Trinh DT, Ng PKW. Characterization of storage proteins in different soybean varieties and their relationship to tofu yield and texture. Food Chem. 2003;82(2):265–273. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00547-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nour V, Trandafir I, Ionica ME. HPLC organic acid analysis in different citrus juices under reversed phase conditions violeta. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 2010;38(1):44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Poysa V, Woodrow L, Yu K. Effect of soy protein subunit composition on tofu quality. Food Res Int. 2006;39(3):309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2005.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rekha CR, Vijayalakshmi G. Influence of natural coagulants on isoflavones and antioxidant activity of tofu. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47(4):387–393. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0064-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekha CR, Vijayalakshmi G. Influence of processing parameters on the quality of soycurd (tofu) J Food Sci Technol. 2013;50(1):176–180. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0245-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydberg J, Cox M, Musikas C, Choppin GR. Principles and practices of solvent extraction. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjay KR, Subramanian R, Senthil A, Vijayalakshmi G. Use of natural coagulants of plant origin in production of soycurd (tofu) Int J Food Eng. 2008;4(1):1–13. doi: 10.2202/1556-3758.1351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma OP, Bhat TK. DPPH antioxidant assay revisited. Food Chem. 2009;113(4):1202–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sitanggang AB, Sinaga WSL, Wie F, et al. Enhanced antioxidant activity of okara through solid state fermentation of GRAS fungi. Food Sci Technol. 2020;40(1):178–186. doi: 10.1590/fst.37218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syah D, Sitanggang AB, Faradilla RF, et al. The influences of coagulation conditions and storage proteins on the textural properties of soy-curd (tofu) CYTA J Food. 2015;13(2):259–263. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2014.948071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak G, Wójciak-Kosior M, Sowa I, et al. Evaluation of isoflavone content and antioxidant activity of selected soy taxa. J Food Compos Anal. 2017;57:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2016.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Penaranda AV, Reitmeier CA, Wilson LA, et al. Sensory characteristics of soymilk and tofu made from lipoxygenase-free and normal soybeans. J Food Sci. 2010;63:1084–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1998.tb15860.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vermerris W, Nicholson R, et al. Biosynthesis of phenolic compounds. In: Vermerris, et al., editors. Phenolic compound biochemistry. Dordrecht: Springer; 2006. pp. 63–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wang HJ, Murphy PA. Mass balance study of isoflavones during soybean processing. J Agric Food Chem. 1996;44(8):2377–2383. doi: 10.1021/jf950535p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Luo K, Liu S, et al. Textural and rheological properties of soy protein isolate tofu-type emulsion gels: influence of soybean variety and coagulant type. Food Biophys. 2018;13(3):324–332. doi: 10.1007/s11483-018-9538-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong YL, et al. Antioxidant Peptides. In: Mine, et al., editors. Bioactive proteins and peptides as functional foods and nutraceuticals. Iowa: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yasin UA, Horo JT, Gebre BA. Physicochemical and sensory properties of tofu prepared from eight popular soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] varieties in Ethiopia. Sci Afr. 2019;6:e00179. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao CC, Kim PH, Eun JB. Influence of high-intensity ultrasound application on the physicochemical properties, isoflavone composition, and antioxidant activity of tofu whey. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Wang Z, Zhang L. Optimization of lactic acid fermentation conditions for fermented tofu whey beverage with high-isoflavone aglycones. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2019;111:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]