Abstract

The availability of high-quality RNA-sequencing and genotyping data of post-mortem brain collections from consortia such as CommonMind Consortium (CMC) and the Accelerating Medicines Partnership for Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) Consortium enable the generation of a large-scale brain cis-eQTL meta-analysis. Here we generate cerebral cortical eQTL from 1433 samples available from four cohorts (identifying >4.1 million significant eQTL for >18,000 genes), as well as cerebellar eQTL from 261 samples (identifying 874,836 significant eQTL for >10,000 genes). We find substantially improved power in the meta-analysis over individual cohort analyses, particularly in comparison to the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project eQTL. Additionally, we observed differences in eQTL patterns between cerebral and cerebellar brain regions. We provide these brain eQTL as a resource for use by the research community. As a proof of principle for their utility, we apply a colocalization analysis to identify genes underlying the GWAS association peaks for schizophrenia and identify a potentially novel gene colocalization with lncRNA RP11-677M14.2 (posterior probability of colocalization 0.975).

Subject terms: Gene regulation, Quantitative trait, Gene expression

Introduction

Defining the landscape of genetic regulation of gene expression in a tissue-specific manner is useful for understanding both normal gene regulation and how variation in gene expression can alter disease risk. In the latter case, a variety of approaches now leverage the association between genetic variants and gene expression changes, including colocalization analysis1–7, transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS)8,9, and gene regulatory network inference10–16.

There has been a relative lack of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) studies from the brain. Because of the more accessible nature of tissues such as blood or lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs), much of the large-scale identification of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) has occurred in these tissues17–20. For most other tissues, obtaining samples for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) requires invasive biopsy, and brain tissues are typically only available in post-mortem brain samples. One effort, the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project21,22, has profiled a broad range of tissues (42 distinct) for eQTL discovery, however, samples sizes in brain have been small (typically 100–150). Recently, efforts to understand gene expression changes in neuropsychiatric23–26 and neurodegenerative diseases27–34 have generated brain RNA-seq from disease and normal tissue, as well as genome-wide genotypes. These analyses have found little evidence for widespread disease-specific eQTL, as well as high cross-cohort overlap24,35, meaning that most eQTL detected are disease-condition independent. This implies that meta-analysis across disease-based cohorts will capture eQTL which are unconfounded by disease state despite differences in disease ascertainment of the samples, and leverages thousands of available samples to produce a well-powered brain eQTL resource for use in downstream research.

Here we generate a public eQTL resource from cerebral cortical tissue using 1433 samples from 4 cohorts from the CommonMind Consortium (CMC)23,24,26 and the Accelerating Medicines Partnership for Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) Consortium30,31, as well as from cerebellum using 261 samples from AMP-AD. We show that eQTL discovered in GTEx, which consists of control individuals (without disease) only, are replicated in this larger brain eQTL resource. We further show widespread differences in regulation between cerebral cortex and cerebellum. To demonstrate one example of the utility of these data, we apply a colocalization analysis, which seeks to identify expression traits whose eQTL association pattern appears to co-occur at the same loci as the clinical trait association, to identify putative genes underlying the GWAS association peaks for schizophrenia36.

Results

We generated eQTL from the publicly available AMP-AD (ROSMAP27,28,35,37, Mayo RNAseq29,38–40) and CMC23,24,26 (MSSM-Penn-Pitt24,26, HBCC26) cohorts with available genotypes and RNA-seq data, using a common analysis pipeline (Supplementary Table 1) (https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn17015233). Analyses proceeded separately by cohort. Briefly, the RNA-seq data were normalized for gene length and GC content prior to adjustment for clinical confounders, processing batch information, and hidden confounders using Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA)41. Genes having at least 1 count per million (CPM) in at least 50% of samples were retained for downstream analysis (Supplementary Table 2). Genotypes were imputed to the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) reference panel42. eQTL were generated adjusting for diagnosis (AD, control, other for AMP-AD cohorts and schizophrenia, control, other for CMC cohorts) and principal components of ancestry separately for ROSMAP, Mayo temporal cortex (TCX), Mayo cerebellum (CER), MSSM-Penn-Pitt, and HBCC. For HBCC, which had a small number of samples derived from infant and adolescents, we excluded samples with age-of-death less than 18, to limit heterogeneity due to differences between the mature and developing brain.

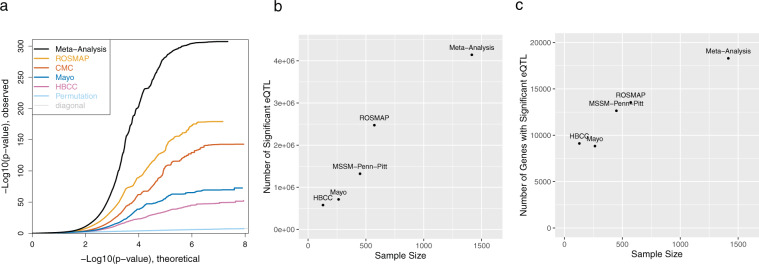

We then performed a meta-analysis using the eQTL from cortical brain regions from the individual cohorts (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) from ROSMAP, MSSM-Penn-Pitt, and HBCC and TCX from Mayo). The meta-analysis identifies substantially more eQTL than the individual cohorts (Table 1, Fig. 1). There is a strong relationship between the sample size in the individual cohorts and meta-analysis and the number of significant eQTL and genes with eQTL (Fig. 1b,c). Notably, the meta-analysis identified significant eQTL (at FDR ≤ 0.05) in >1000 genes for which no eQTL were observed in any individual cohort. Additionally, we find significant eQTL for 18,295 (18,433 when considering markers with minor allele frequency (MAF) down to 1%) of the 19,392 genes included in the analysis.

Table 1.

eQTL results from individual cohorts and meta-analysis.

| Cohort | Cis eQTL* | Unique Genes with Signif. eQTL | eQTL (Genes) not Present in GTEx** | Meta-eQTL (Genes) not found in Cohort | Genes w/o eQTL in CMC, ROSMAP, HBCC or Mayo TCX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROSMAP | 2,472,838 | 13,543 | 2,205,025 (7,829) | 2,103,711 (5,079) | |

| Mayo TCX | 712,401 | 8,838 | 480,507 (4,439) | 3,485,381 (9,591) | |

| CMC | 1,322,680 | 12,641 | 1,062,830 (7,206) | 2,948,886 (5,897) | |

| HBCC | 577,512 | 9,112 | 379,732 (4,645) | 3,614,448 (9,337) | |

| Meta-Analysis*** | 4,142,776 | 18,295 | 3,800,208 (11,395) | 1,042 |

*SNP-gene pairs with MAF ≥ 0.02 and FDR ≤ 0.05.

**GTEx (v7) Anterior Cingulate Cortex, Cortex or Frontal Cortex.

***Additional 36,352 (138) eQTL (Genes) with 0.01 ≤ MAF < 0.02.

Fig. 1.

eQTL meta-analysis discovers more eQTL than individual cohorts. (a) Quantile-quantile plot of eQTL from individual cohorts as well as the meta-analysis of the true (black) and permuted (light blue) data. Number of significant eQTL (SNP-gene pairs) (b) or genes with significant eQTL (c) as a function of cohort size.

We then compared our cortical eQTL to those from GTEx (v7)21, which is the most comprehensive brain eQTL database available in terms of number of available brain tissues (Table 1, Table 2). Due to the substantially larger power in these data, we find >3.8 million eQTL not identified in GTEx cortical regions (Anterior Cingulate Cortex, Cortex or Frontal Cortex) and we find eQTL for >11,000 genes with no eQTL in these cortical regions in GTEx. While GTEx employs a stricter approach to the control of false discovery rate (FDR), we find that re-analysis of the GTEx cortical regions using an approach similar to ours (see Methods) did not account for the number of eQTL and genes with eQTL discovered in this analysis, but not in GTEx (3,619,693 and 6,866 for eQTL and genes, respectively, when using the less conservative approach). Next, we evaluated the replication within our cortical and cerebellar eQTL of the region specific eQTL identified in GTEx. The cortical eQTL generated through the current analyses strongly replicate the eQTL available through GTEx, not only for cortical regions, but for all brain regions including cervical spinal cord (Table 2). Interestingly, the replication in these cortical eQTL of eQTL derived from the two GTEx cerebellar brain regions (cerebellum and cerebellar hemisphere) is consistently lower than for other brain regions represented in GTEx. However, replication of GTEx cerebellar eQTL is high when compared to the cerebellar eQTL generated in this analysis from the Mayo Clinic CER samples. We also performed the reverse comparison, by examining the replication of our eQTL in those region-specific eQTL identified in GTEx. Unsurprisingly, the replication levels were substantially lower, due to the lower power in the GTEx analyses. Replication rates were not substantially changed by using GTEx eQTL discovered using our less conservative approach.

Table 2.

Replication rates between GTEx and publicly available eQTL from these analyses.

| GTEx Brain Region | # eQTL | Replication (π1) of GTEx eQTL | Replication (π1) of AMP-AD eQTL in GTEx | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-Analysis | ROSMAP | Mayo TCX | Mayo CER | Meta-Analysis | ROSMAP | Mayo TCX | Mayo CER | ||

| Amygdala | 158,270 | 0.974 | 0.987 | 0.986 | 0.916 | 0.356 | 0.421 | 0.701 | 0.555 |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex (BA24) | 291,898 | 0.976 | 0.971 | 0.962 | 0.903 | 0.445 | 0.516 | 0.772 | 0.592 |

| Caudate Basal Ganglia | 435,939 | 0.966 | 0.961 | 0.935 | 0.881 | 0.488 | 0.544 | 0.781 | 0.636 |

| Cerebellar Hemisphere | 575,583 | 0.896 | 0.897 | 0.781 | 0.962 | 0.458 | 0.509 | 0.719 | 0.831 |

| Cerebellum | 819,435 | 0.893 | 0.890 | 0.711 | 0.936 | 0.526 | 0.577 | 0.761 | 0.863 |

| Cortex | 478,903 | 0.980 | 0.973 | 0.941 | 0.892 | 0.547 | 0.604 | 0.834 | 0.659 |

| Frontal Cortex (BA9) | 342,988 | 0.974 | 0.967 | 0.963 | 0.897 | 0.489 | 0.547 | 0.792 | 0.632 |

| Hippocampus | 221,876 | 0.967 | 0.970 | 0.937 | 0.905 | 0.404 | 0.462 | 0.710 | 0.570 |

| Hypothalamus | 227,808 | 0.974 | 0.966 | 0.960 | 0.913 | 0.392 | 0.436 | 0.719 | 0.580 |

| Nucleus Accumbens Basal Ganglia | 376,390 | 0.958 | 0.952 | 0.781 | 0.894 | 0.453 | 0.514 | 0.761 | 0.622 |

| Putamen Basal Ganglia | 293,880 | 0.966 | 0.974 | 0.930 | 0.890 | 0.433 | 0.493 | 0.764 | 0.591 |

| Spinal Cord Cervical (c-1) | 175,702 | 0.940 | 0.952 | 0.918 | 0.862 | 0.330 | 0.394 | 0.640 | 0.514 |

| Substantia Nigra | 120,582 | 0.964 | 0.951 | 0.960 | 0.928 | 0.297 | 0.372 | 0.635 | 0.479 |

Additionally, we compared our eQTL to a publically available fetal brain eQTL resource43 and found good replication of these eQTL as well (estimated replication rate π1 = 0.909 for the cortical meta-analysis, and π1 = 0.861 for cerebellum), though somewhat lower than the replication observed in the GTEx cohorts, which are comprised of adult-derived samples.

Finally, as a proof of concept, we performed a colocalization analysis between our eQTL meta-analysis and the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) v2 schizophrenia GWAS summary statistics36. Seventeen genes showed posterior probability of colocalization using coloc7 (PP(H4)) > 0.7 (Table 3), with 3 showing PP(H4) > 0.95 (FURIN, ZNF823, RP11-677M14.2). FURIN, having previously identified as a candidate through colocalization24 has recently been shown to reduce brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) maturation and secretion when inhibited by miR-338-3p44. ZNF823 has been identified in previous colocalization analyses45,46. RP11-677M14.2, a lncRNA located inside NRGN, while not previously identified through colocalization analysis, has been shown to be down-regulated in the amygdala of schizophrenia patients47. Noteably, NRGN does not appear to show eQTL colocalization (PP(H4) = 0.006), instead showing strong evidence for the eQTL and GWAS associations occurring independently (PP(H3) = 0.994). Two additional strong colocalizations THOC7 (PP(H4) = 0.943) and FAM85B (PP(H4) = 0.948) show other potential candidates in the region (Supplementary Table 3). At the THOC7 locus, the competing gene, C3orf49 shows slightly lower strength for colocalization (PP(H4) = 0.820), and the associations do not appear to be independent (R2 between best SNPs = 0.979). At the FAM85B locus, the competing pseudo gene FAM86B3P shows substantially lower evidence for colocalization (PP(H4) = 0.513) and in this case too, the associations appear to be non-independent (R2 = 0.902).

Table 3.

Top colocalized genes as inferred between meta-analysis eQTL and the PGC2 schizophrenia GWAS.

| Gene | eQTL Peak Location* | NSNPs | Min(p-value) | Best Colocalized SNP** | Posterior Probability of Colocalization | Additional Candidates at this Locus*** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | Start | End | GWAS | eQTL | |||||

| RERE | 1 | 7412645 | 9877280 | 4905 | 2.72E-09 | 2.28E-21 | rs301792 | 0.730 | |

| PTPRU | 1 | 28563084 | 30653243 | 4099 | 1.28E-09 | 4.42E-10 | rs1498232 | 0.890 | |

| FOXN2 | 2 | 47542228 | 49606348 | 5437 | 1.66E-06 | 8.85E-45 | rs79073127 | 0.782 | |

| C3orf49 | 3 | 62805378 | 64834213 | 4906 | 2.58E-08 | 1.10E-13 | rs832187 | 0.820 | Yes |

| THOC7 | 3 | 62819766 | 64848612 | 4886 | 2.58E-08 | 2.21E-39 | rs832190 | 0.943 | Yes |

| TBC1D19 | 4 | 25578209 | 27755954 | 4432 | 7.44E-07 | 7.85E-07 | rs6825268 | 0.900 | |

| CLCN3 | 4 | 169533866 | 171644821 | 4956 | 1.02E-08 | 1.91E-09 | rs10520163 | 0.768 | |

| PPP1R18 | 6 | 29644275 | 31655438 | 1055 | 1.16E-19 | 5.52E-07 | rs2523607 | 0.827 | Yes |

| LINC00222 | 6 | 108073451 | 110091064 | 3600 | 3.37E-08 | 1.63E-07 | rs9398171 | 0.852 | |

| FAM85B | 8 | 8089567 | 9084121 | 3725 | 2.03E-08 | 5.63E-31 | rs2980439 | 0.948 | Yes |

| ENDOG | 9 | 130581300 | 132584048 | 3294 | 1.92E-06 | 6.90E-62 | rs6478854 | 0.721 | Yes |

| RP11-677M14.2 | 11 | 123614560 | 125616016 | 5253 | 3.68E-12 | 1.50E-09 | rs55661361 | 0.975 | |

| FURIN | 15 | 90414642 | 92426654 | 4767 | 2.30E-12 | 1.29E-20 | rs4702 | 0.999 | |

| CNOT1 | 16 | 57553885 | 59662867 | 5364 | 1.15E-08 | 1.16E-06 | rs12325245 | 0.862 | |

| ELAC2 | 17 | 11896953 | 13921426 | 5651 | 2.84E-06 | 3.90E-106 | rs1044564 | 0.856 | |

| ZNF823 | 19 | 10832190 | 12840037 | 3844 | 1.57E-06 | 5.38E-10 | rs3095917 | 0.961 | |

| PTK6 | 20 | 61160251 | 62960229 | 4527 | 4.03E-08 | 1.09E-26 | rs427230 | 0.897 | |

*eQTL Peak Location is ±1 Mb around the gene location.

**SNP showing the highest PP(H4) between the gene and GWAS trait.

***At Posterior Probability of Colocalization ≥ 0.5.

Discussion

Using resources generated in the AMP-AD and CMC consortia, we have generated a well-powered brain eQTL resource for use by the scientific community. Unsurprisingly, we see a strong relationship between the number of significant eQTL, as well as genes with significant eQTL, and sample size using analyses from the individual cohorts as well as the meta-analysis of those cohorts. This result has previously been shown for lower sample sizes21. We also show higher replication of GTEx eQTL in the meta-analysis relative to the individual cohorts. These conclusions appear to be independent of methodological differences between our analysis and the one done by GTEx.

Notably, we find significant eQTL for nearly every gene in our analysis, which include all but very lowly expressed genes (less than 1 cpm in more than 50% of samples). The wide discovery of eQTL is potentially beneficial for analyses utilizing these results, such as colocalization analysis or TWAS imputation, because more genes with significant eQTL means more genes can be evaluated with these approaches. Because we have discovered eQTL for most genes, further increasing sample size will not substantially increase the number of genes with significant eQTL. However it is likely that the number of significant eQTL associations within each gene would continue to increase, which may include additional associations tagging the same regulator or independent associations tagging weaker regulators, along with the accuracy of estimated effect sizes. This will result in a more accurate landscape of regulatory association, which will improve the ability to fine-map causal regions, and colocalize eQTL signal with clinical traits of interest. Thus, it will be valuable to continue to update this meta-analysis with additional data from these consortia and other resources as they become available, and continue to improve this resource as future data permits. Future work may also focus on using well-powered analysis to study the landscape of causal variation and co-variation in gene regulation.

We found distinct eQTL patterns across cerebral cortical and cerebellar brain regions in our resource. Specifically, comparison of eQTL from our resource with those from GTEx shows high replication for the majority of brain regions. However, cerebellar regions show consistently lower replication with the cerebral cortical eQTL generated here. In contrast, the cerebellar eQTL generated from the Mayo Clinic study replicate GTEx cerebellar eQTL at a substantially higher rate, suggesting a different pattern of regulatory variation affecting expression in cerebellum versus other brain regions. Indeed, epigenomic analyses show substantial differences between cerebellar and cerebral cortical regions48–51, particularly in methylation patterns, which could drive different eQTL association patterns. This is further corroborated by the observation of substantial coexpression differences between cerebellar and other brain regions52. These effects could be due to differences in cell type composition, with cerebellar regions consisting of substantially more neurons than other brain regions53. This is supported by a gene enrichment analysis of genes showing different eQTL association patterns between cerebellum and cortex, which showed that many of the top gene sets were neuron or signaling related (Supplementary Table 4). One recent report suggests that there are also widespread differences in histone modifications within cell types derived from cerebellar and cortical regions54, though this effect had not been noted in other studies. In particular, Ma et al.54 observed that both neuronal and non-neuronal cell types show differing histone modifications across tissue of origin. Further work is necessary to confirm this finding and to develop models to deconvolve the cell-type specific regulatory effects in different brain regions55–57, however our analysis demonstrates that this meta-analysis is representative of eQTL across the majority of brain regions, with the exception of cerebellum. Future meta-analytic analyses may also cast a wider net in terms of brain regions included.

The replication of fetal eQTL, while significant, is somewhat lower than the replication of adult eQTL represented in GTEx. This may be due to multiple factors. The fetal eQTL analysis was generated from brain homogenate, rather than dissected brain regions, though the lower replication likely also reflects broad transcriptional differences between developing and mature brain58. These transcriptional differences may also explain why we find substantially more eQTL than a recently published, similarly sized eQTL analysis which uses samples from across developmental and adult timepoints25, and why this meta-analysis shows higher replication of GTEx eQTL.

Previous studies report a lack of widespread disease-specific eQTL observed in schizophrenia (CMC)24 and Alzheimer’s (ROSMAP)35. In accordance, we find a strong overlap among eQTL across disparate disease samples, particularly those with neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders, as well as normal individuals from these and other cohorts such as GTEx24,35. This suggests that disease-specific eQTL, if they exist, are likely few in number and/or small in effect size, relative to condition-independent eQTL in general. If they do exist, disease-specific eQTL discovery may be successful in more targeted analyses or with larger sample sizes or meta-analyses, but was not explored for the purpose of this general resource. Thus, the heterogeneous samples derived from different disease-based cohorts can be meta-analyzed to create a general-purpose brain eQTL resource representing adult gene regulation, despite comprising samples with different disease backgrounds, along with normal controls. Therefore, these eQTL will be useful both within and outside these specific disease contexts. For example, since these eQTL are not disease specific they may be used to understand healthy gene expression regulation in the brain, as well as to infer colocalization of eQTL signatures with disease risk for any disease whose tissue etiology is from the brain, since these signatures are reflective of normal brain regulation. It should be stated that while many eQTL are not disease specific, i.e. they are identified under various central nervous system (CNS) disease diagnoses and in control brains, they may still contribute to common CNS diseases as previously demonstrated24,32–34,45,46. While we have demonstrated a proof-of-concept colocalization analysis with a previously published schizophrenia GWAS, these eQTL are a broadly useful resource for studying neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders, as well as for understanding the landscape of gene regulation in brain.

Methods

RNA-seq Re-alignment

For the CMC studies (MSSM-Penn-Pitt, HBCC), RNA-seq reads were aligned to GRCh37 with STAR v2.4.0g159 from the original FASTQ files. Uniquely mapping reads overlapping genes were counted with featureCounts v1.5.260 using annotations from ENSEMBL v75.

For the AMP-AD studies (ROSMAP, Mayo RNAseq), Picard v2.2.4 (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) was used to generate FASTQ files from the available BAM files, using the Picard SamToFastq function. Picard SortSam was first applied to ensure that R1 and R2 reads were correctly ordered in the intermediate SAM file before converting to FASTQ. The converted FASTQs were aligned to the GENCODE24 (GRCh38) reference genome using STAR v2.5.1b, with twopassMode set as Basic. Gene counts were computed for each sample by STAR by setting quantMode as GeneCounts.

RNA-seq normalization

To account for differences between samples, studies, experimental batch effects and unwanted RNA-seq-specific technical variations, we performed library normalization and covariate adjustments for each study separately using fixed/mixed effects modeling. A mixed effect model was required to jointly normalize both tissues from the Mayo cohort. All other cohorts contained only one tissue, so a fixed effect model was used. The workflow consisted of the following steps:

Gene filtering: Out of ~56 K aligned and quantified genes, only genes showing at least modest expression were used in this analysis. Genes that were expressed more than 1 CPM (read Counts Per Million total reads) in at least 50% of samples in each tissue and diagnosis category were retained for analysis. Additionally, genes with available gene length and percentage GC content from BioMart December 2016 archive were subselected from the above list. This resulted in approximately 14 K to 16 K genes in each study.

Calculation of normalized expression values: Sequencing reads were then normalized in two steps. First, conditional quantile normalization (CQN)61 was applied to account for variations in gene length and GC content. In the second step, the confidence of sampling abundance was estimated using a weighted linear model using the voom-limma package in bioconductor62,63. The normalized observed read counts, along with the corresponding weights, were used in the following steps.

Outlier detection: Based on normalized log2(CPM) of expression values, outlier samples were detected using principal component analysis (PCA)64,65 and hierarchical clustering. Samples identified as outliers using both the above methods were removed from further analysis.

Covariate imputation: Before identifying associated covariates, important missing covariates were imputed. Principally, post-mortem interval (PMI), or the latency between death and tissue collection, which is frequently an important covariate for the analysis of gene expression from post-mortem brain tissue, was imputed for a portion of samples in Mayo RNAseq data for which true values were unavailable. Genomic predictors of PMI were estimated using ROSMAP and MSSM (an additional RNA-seq study available through AMP-AD) samples and were used to impute missing values as necessary.

Covariate identification: Normalized log2(CPM) counts were then explored to determine which known covariates (both biological and technical) should be adjusted. Except for the HBCC study, we used a stepwise (weighted) fixed/mixed effect regression modeling approach to select the relevant covariates having a significant association with gene expression. Here, covariates were sequentially added to the model if they were significantly associated with any of the top principal components, explaining more than 1% of variance of expression residuals. For HBCC, we used a model selection based on Bayesian information criteria (BIC) to identify the covariates that improve the model in more than 50% of genes.

SVA adjustments: After identifying the relevant known confounders, hidden-confounders were identified using the Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA)41. We used a similar approach as previously defined24 to find the number of surrogate variables (SVs), which is more conservative than the default method provided by the SVA package in R66. The basic idea of this approach is that for an eigenvector decomposition of permuted residuals each eigenvalue should explain an equal amount of the variation. By the nature of eigenvalues, however, there will always be at least one that exceeds the expected value. Thus, from a series of 100 permutations of residuals (white noise) we identified the number of covariates as shown in Supplementary Table 1. We applied the “irw” (iterative re-weighting) version of SVA to the normalized gene expression matrix, along with the covariate model described above to obtain residual gene expression for eQTL analysis.

Covariate adjustments: We performed a variant of fixed/mixed effect linear regression, choosing mixed-effect models when multiple tissues or samples, were available per individual, as shown here: gene expression ~ Diagnosis + Sex + covariates + (1|Donor), where each gene was linearly regressed independently. Here Donor (individual) was modeled as a random effect when multiple tissues from the same individual were present. Observation weights (if any) were calculated using the voom-limma62,63 pipeline, which has a net effect of up-weighting observations with inferred higher precision in the linear model fitting process to adjust for the mean-variance relationship in RNA-seq data. The diagnosis component was then added back to the residuals to generate covariate-adjusted expression for eQTL analysis.

This workflow was applied separately for each study. For the AMP-AD studies, gene locations were lifted over to GRCh37 for comparison with the genotype imputation panel (described below). For HBCC, samples with age <18 were excluded prior to analysis. Supplementary Table 1 shows the covariates and surrogate variables identified in each study.

AD diagnosis harmonization

Prior to RNA-seq normalization, we harmonized the LOAD definition across AMP-AD studies. AD controls were defined as patients with a low burden of plaques and tangles, as well as lack of evidence of cognitive impairment. For the ROSMAP study, we defined AD cases to be individuals with a Braak67 greater than or equal to 4, CERAD score68 less than or equal to 2, and a cognitive diagnosis of probable AD with no other causes (cogdx = 4), and controls to be individuals with Braak less than or equal to 3, CERAD score greater than or equal to 3, and cognitive diagnosis of ‘no cognitive impairment’ (cogdx = 1). For the Mayo Clinic study, we defined disease status based on neuropathology, where individuals with Braak score greater than or equal to 4 were defined to be AD cases, and individuals with Braak less than or equal to 3 were defined to be controls. Individuals not meeting “AD case” or “control” criteria were retained for analysis, and were categorized as “other” for the purposes of RNA-seq adjustment.

Genotype QC and imputation

Genotype QC was performed using PLINK v1.969. Markers with zero alternate alleles, genotyping call rate ≤ 0.98, Hardy-Weinberg p-value < 5e−5 were removed, as well as individuals with genotyping call rate < 0.90. Samples were then imputed to HRC (Version r1.1 2016)42 as follows: marker positions were lifted-over to GRCh37, if necessary. Markers were then aligned to the HRC loci using HRC-1000G-check-bim-v4.2 (http://www.well.ox.ac.uk/~wrayner/tools/), which checks the strand, alleles, position, reference/alternate allele assignments and frequencies of the markers, removing A/T & G/C single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.4, SNPs with differing alleles, SNPs with > 0.2 allele frequency difference between the genotyped samples and the HRC samples, and SNPs not in the reference panel. Imputation was performed via the Michigan Imputation Server70 using the Eagle v2.371 phasing algorithm. Imputation was done separately by cohort and by chip within cohort, and markers with R2 ≥ 0.7 and minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.01 (within cohort) were retained for analysis.

Genetic ancestry inference

GEMTOOLs72 was used to infer ancestry and compute ancestry components separately by cohort. The GEMTOOLs algorithm uses a significance test to estimate the number of eigenvectors (ancestry components) necessary to represent the variability in the data73. For each cohort, we used the top components as estimated by the GEMTOOLs algorithm, which resulted in some variation in the number of components selected. For MSSM-Penn-Pitt and HBCC, which are multi-ethnic cohorts, only Caucasian samples were retained for eQTL analysis.

eQTL analysis

eQTL were generated separately in each cohort and tissue using MatrixEQTL74 adjusting for harmonized Diagnosis and inferred Ancestry components using “cis” gene-marker comparisons: Expression ~ Genotype + Diagnosis + PC1 + … + PCn,, where PCk is the kth ancestry component, using Expression variables which were previously covariate adjusted as described above. Here we define “cis” as ± 1 MB around the gene, and GRCh37 gene locations were used for consistency with the marker imputation panel. Meta-analysis was performed via fixed-effect model75 using an adaptation of the metareg function in the gap package in R. In order to assess potential inflation of Type 1 error, we performed 5 permutations of the gene expression values, relative to genotype and ancestry components, within diagnosis for each cohort, and repeated the regression analyses as described above. For each of the 5 iterations of permutation, a meta-analysis was then performed across the 4 cohorts. We found that Type 1 error was well controlled (Fig. 1a). Given that multiple tissues were present, we also evaluated a random-effect model, but found substantially deflated p-values (less significant) in the permutations, relative to the expected distribution, suggesting that this model is over-conservative.

Comparison with GTEx and fetal eQTL

Full summary statistics for the GTEx v721 eQTL for all available brain regions were obtained from the GTEx Portal (https://gtexportal.org/), and fetal eQTL were obtained from Figshare76. For each replication comparison (e.g. meta-analysis vs GTEx or meta-analysis vs. fetal eQTL), only markers and genes present in both the external eQTL and our analysis were retained for comparison. As this was done separately for GTEx and for the fetal eQTL resource, the list of genes and SNPs varies slightly for each comparison. The replication rate was estimated as the π1 statistic using the qvalue package77 in R as follows: we extracted the meta-analysis p-values for all SNP-gene pairs, which were significant in GTEx at FDR ≤ 0.05. We then applied the ‘qvalue’ command to the meta-analysis p-values to generate , which corresponds to estimated proportion of non-null p-values77. The ‘smoother’ option was used to estimate as a function of the tuning parameter λ as it approaches 1. The variance around this estimate is relatively small (see Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 for example) and does not materially affect the observations in this manuscript.

Conversely, we estimated the replication rate of significant meta-analysis eQTL SNP-gene pairs in GTEx. Analogous methods were used to estimate all other replication rates. For the purposes of reporting the total number of eQTL not present in GTEx, and genes without eQTL in GTEx (Table 1), we have included genes and SNP-gene pairs not present in GTEx in the count, however this accounts for a relatively small proportion of the difference (472,995 eQTL and 1481 genes).

GTEx eQTL generation

In order to verify that the observed power increase and replication imbalances were not due to methodological differences between this manuscript and those performed by GTEx, we obtained access to the GTEx v7 data, and generated eQTL for cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and frontal cortex using our approach. We used gene expression and imputed genotypes as provided, as well as the provided covariates, which included 3 ancestry covariates, 14-15 surrogate variable covariates, sex and platform. We then repeated the comparisons with the meta-analysis described in the previous section, using a MAF cutoff of 0.03, which best appeared to control Type 1 error, as observed by permutation between genotype and gene expression, while maximizing the number of significant eQTL in the true data. Results did not change materially.

Pathway analysis of cerebellar eQTL genes

In order to identify whether genes showing cerebellar-specific eQTL patterns showed any biological coherence, we performed a pathway analysis as follows. For genes with at least 5 significant cerebellar eQTL, we computed the Spearman correlation of effect-size between cerebellum eQTL and cortical eQTL for the loci that were significant in cerebellum. We then selected genes for which the effect-sizes did not show positive correlation (Spearman’s ρ < 0.1) between the two tissues as showing different eQTL association patterns across the gene and performed a pathway analysis with GO biological processes Fisher’s exact test. Note that due to the (power-mediated) greater detection of eQTL in cortex, we did not perform the reverse comparison. The results were relatively robust to the choice of minimum number of significant eQTL, correlation cutoff, and choice of correlation statistic (Spearman vs Pearson).

Coloc analysis

We applied Approximate Bayes Factor colocalization (coloc.abf)7 from the coloc R package to the summary statistics from the PGC2 Schizophrenia GWAS36 downloaded from the PGC website (http://pgc.unc.edu), and the summary statistics from the eQTL meta-analysis. Each gene present in the meta-analysis was compared to the GWAS in turn, and suggestive and significant GWAS peaks with p-value < 5e-6 were considered for analysis.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

For the ROSMAP and Mayo RNAseq studies, the results published here are in whole or in part based on data obtained from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (doi:10.7303/syn2580853). ROSMAP study data were provided by the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. Data collection was supported through funding by NIA grants P30AG10161, R01AG15819, R01AG17917, R01AG30146, R01AG36836, U01AG32984, U01AG46152, the Illinois Department of Public Health, and the Translational Genomics Research Institute. Mayo RNA-seq study data were provided by the following sources: The Mayo Clinic Alzheimers Disease Genetic Studies, led by Dr. Nilufer Ertekin-Taner and Dr. Steven G. Younkin, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL using samples from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, and the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank. Data collection was supported through funding by NIA grants P50 AG016574, R01 AG032990, U01 AG046139, R01 AG018023, U01 AG006576, U01 AG006786, R01 AG025711, R01 AG017216, R01 AG003949, NINDS grant R01 NS080820, CurePSP Foundation, and support from Mayo Foundation. Study data includes samples collected through the Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona. The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinsons Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimers Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimers Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinsons Research. This study was in part supported by NIH RF1 AG051504 and R01 AG061796 (NET). For CommonMind, data were generated as part of the CommonMind Consortium supported by funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Limited, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and NIH grants R01MH085542, R01MH093725, P50MH066392, P50MH080405, R01MH097276, RO1-MH-075916, P50M096891, P50MH084053S1, R37MH057881, AG02219, AG05138, MH06692, R01MH110921, R01MH109677, R01MH109897, U01MH103392, and contract HHSN271201300031C through IRP NIMH. Brain tissue for the study was obtained from the following brain bank collections: the Mount Sinai NIH Brain and Tissue Repository, the University of Pennsylvania Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center, the University of Pittsburgh NeuroBioBank and Brain and Tissue Repositories, and the NIMH Human Brain Collection Core. CMC Leadership: Panos Roussos, Joseph Buxbaum, Andrew Chess, Schahram Akbarian, Vahram Haroutunian (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai), Bernie Devlin, David Lewis (University of Pittsburgh), Raquel Gur, Chang-Gyu Hahn (University of Pennsylvania), Enrico Domenici (University of Trento), Mette A. Peters, Solveig Sieberts (Sage Bionetworks), Thomas Lehner, Geetha Senthil, Stefano Marenco, Barbara K. Lipska (NIMH). SKS, TP, KKD, JE, AKG, LO, BAL, and LMM were additionally supported by NIA grants U24 AG61340, U01 AG46170, U01 AG 46161, R01 AG46171, R01 AG 46174. All data used in this manuscript have been previously released through their respective consortia and have been reviewed by IRBs at their institution of origin. Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals.

Author contributions

S.K.S., S.M., M.P., P.L.D.J., N.E.T. and L.M.M., the AMP-AD Consortium, and the CMC Consortium contributed to the design and generation of the study data. S.K.S., T.P., M.C., M.A., J.S.R., G.H., K.D.D., J.C., P.J.E. and J.E. contributed the data analysis. S.K.S., T.P., G.H., A.K.G., L.O., M.P., B.A.L., L.M.M. contributed to the manuscript preparation and data sharing.

Data availability

Data for the ROSMAP37 and Mayo cohorts40 are available through the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal31. Data for the MSSM-Penn-Pitt and HBCC cohorts are available through the CommonMind Knowledge Portal23.

eQTL results for the ROSMAP78, Mayo TCX79, Mayo CER80 and cortical meta-analysis81 are available through the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal. These results include SNP (location, rsid, alleles, and allele frequency) and gene (location, gene symbol, strand and biotype) information, as well as estimated effect size (beta), statistic (z), p-value, FDR, and expression-increasing allele.

Code availability

An R package with all code for the gene expression normalization is available at https://github.com/Sage-Bionetworks/ampad-diffexp. All other analyses were generated using packages publicly available from their respective authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Solveig K. Sieberts, Email: solly.sieberts@sagebase.org

Lara M. Mangravite, Email: lara.mangravite@sagebase.org

The CommonMind Consortium (CMC):

Schahram Akbarian, Jaroslav Bendl, Michael S. Breen, Kristen Brennand, Leanne Brown, Andrew Browne, Joseph D. Buxbaum, Alexander Charney, Andrew Chess, Lizette Couto, Greg Crawford, Olivia Devillers, Bernie Devlin, Amanda Dobbyn, Enrico Domenici, Michele Filosi, Elie Flatow, Nancy Francoeur, John Fullard, Sergio Espeso Gil, Kiran Girdhar, Attila Gulyás-Kovács, Raquel Gur, Chang-Gyu Hahn, Vahram Haroutunian, Mads Engel Hauberg, Laura Huckins, Rivky Jacobov, Yan Jiang, Jessica S. Johnson, Bibi Kassim, Yungil Kim, Lambertus Klei, Robin Kramer, Mario Lauria, Thomas Lehner, David A. Lewis, Barbara K. Lipska, Kelsey Montgomery, Royce Park, Chaggai Rosenbluh, Panagiotis Roussos, Douglas M. Ruderfer, Geetha Senthil, Hardik R. Shah, Laura Sloofman, Lingyun Song, Eli Stahl, Patrick Sullivan, Roberto Visintainer, Jiebiao Wang, Ying-Chih Wang, Jennifer Wiseman, Eva Xia, Wen Zhang, and Elizabeth Zharovsky

The AMP-AD Consortium:

Laura Addis, Sadiya N. Addo, David Charles Airey, Matthias Arnold, David A. Bennett, Yingtao Bi, Knut Biber, Colette Blach, Elizabeth Bradhsaw, Paul Brennan, Rosa Canet-Aviles, Sherry Cao, Anna Cavalla, Yooree Chae, William W. Chen, Jie Cheng, David Andrew Collier, Jeffrey L. Dage, Eric B. Dammer, Justin Wade Davis, John Davis, Derek Drake, Duc Duong, Brian J. Eastwood, Michelle Ehrlich, Benjamin Ellingson, Brett W. Engelmann, Sahar Esmaeelinieh, Daniel Felsky, Cory Funk, Chris Gaiteri, Samuel Gandy, Fan Gao, Opher Gileadi, Todd Golde, Shaun E. Grosskurth, Rishi R. Gupta, Alex X. Gutteridge, Vahram Haroutunian, Basavaraj Hooli, Neil Humphryes-Kirilov, Koichi Iijima, Corey James, Paul M. Jung, Rima Kaddurah-Daouk, Gabi Kastenmuller, Hans-Ulrich Klein, Markus Kummer, Pascale N. Lacor, James Lah, Emma Laing, Allan Levey, Yupeng Li, Samantha Lipsky, Yushi Liu, Jimmy Liu, Zhandong Liu, Gregory Louie, Tao Lu, Yiyi Ma, Yasuji Y. Matsuoka, Vilas Menon, Bradley Miller, Thomas P. Misko, Jennifer E. Mollon, Kelsey Montgomery, Sumit Mukherjee, Scott Noggle, Ping-Chieh Pao, Tracy Young Pearce, Neil Pearson, Michelle Penny, Vladislav A. Petyuk, Nathan Price, Danjuma X. Quarless, Brinda Ravikumar, Janina S. Ried, Cara Lee Ann Ruble, Heiko Runz, Andrew J. Saykin, Eric Schadt, James E. Scherschel, Nicholas Seyfried, Joshua M. Shulman, Phil Snyder, Holly Soares, Gyan P. Srivastava, Henning Stockmann, Mariko Taga, Shinya Tasaki, Jessie Tenenbaum, Li-Huei Tsai, Aparna Vasanthakumar, Astrid Wachter, Yaming Wang, Hong Wang, Minghui Wang, Christopher D. Whelan, Charles White, Kara H. Woo, Paul Wren, Jessica W. Wu, Hualin S. Xi, Bruce A. Yankner, Steven G. Younkin, Lei Yu, Maria Zavodszky, Wenling Zhang, Guoqiang Zhang, Bin Zhang, and Jun Zhu

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-020-00642-8.

References

- 1.Zhu Z, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:481–487. doi: 10.1038/ng.3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nica AC, et al. Candidate Causal Regulatory Effects by Integration of Expression QTLs with Complex Trait Genetic Associations. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ongen H, et al. Estimating the causal tissues for complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1676–1683. doi: 10.1038/ng.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun S, et al. Limited statistical evidence for shared genetic effects of eQTLs and autoimmune-disease-associated loci in three major immune-cell types. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:600–605. doi: 10.1038/ng.3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hormozdiari F, Kostem E, Kang EY, Pasaniuc B, Eskin E. Identifying Causal Variants at Loci with Multiple Signals of Association. Genetics. 2014;198:497–508. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.167908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He X, et al. Sherlock: Detecting Gene-Disease Associations by Matching Patterns of Expression QTL and GWAS. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:667–680. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giambartolomei C, et al. Bayesian Test for Colocalisation between Pairs of Genetic Association Studies Using Summary Statistics. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamazon ER, et al. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1091–1098. doi: 10.1038/ng.3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbeira AN, et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1825. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03621-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, et al. An integrative genomics approach to the reconstruction of gene networks in segregating populations. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2004;105:363–74. doi: 10.1159/000078209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schadt E, et al. Mapping the Genetic Architecture of Gene Expression in Human Liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu J, et al. Integrating large-scale functional genomic data to dissect the complexity of yeast regulatory networks. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:854–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenawalt, D. M. et al. A survey of the genetics of stomach, liver, and adipose gene expression from a morbidly obese cohort. Genome Res. 21, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Zhang B, et al. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2013;153:707–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franzén O, et al. Cardiometabolic risk loci share downstream cis- and trans-gene regulation across tissues and diseases. Science. 2016;353:827–30. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters LA, et al. A functional genomics predictive network model identifies regulators of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1437–1449. doi: 10.1038/ng.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Battle A, et al. Characterizing the genetic basis of transcriptome diversity through RNA-sequencing of 922 individuals. Genome Res. 2014;24:14–24. doi: 10.1101/gr.155192.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westra H-J, et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1238–1243. doi: 10.1038/ng.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Võsa, U. et al. Unraveling the polygenic architecture of complex traits using blood eQTL meta-analysis. bioRxiv Preprint at, http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/10/19/447367.abstract (2018).

- 20.Qi T, et al. Identifying gene targets for brain-related traits using transcriptomic and methylomic data from blood. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2282. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04558-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguet F, et al. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550:204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature24277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ardlie KG, et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: Multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science (80-.) 2015;348:648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2015. CommonMind Consortium Data Release Portal. Synapse. [DOI]

- 24.Fromer M, et al. Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nature Neuroscience. 2016;19:1442–1453. doi: 10.1038/nn.4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D, et al. Comprehensive functional genomic resource and integrative model for the human brain. Science (80-.). 2018;362:eaat8464. doi: 10.1126/science.aat8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman GE, et al. CommonMind Consortium provides transcriptomic and epigenomic data for Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Sci. Data. 2019;6:180. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0183-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chibnik LB, et al. Susceptibility to neurofibrillary tangles: role of the PTPRD locus and limited pleiotropy with other neuropathologies. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;23:1521. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mostafavi S, et al. A molecular network of the aging human brain provides insights into the pathology and cognitive decline of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:811–819. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen M, et al. Human whole genome genotype and transcriptome data for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Sci. Data. 2016;3:160089. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wan, Y.W. et al. Meta-Analysis of the Alzheimer’s Disease Human Brain Transcriptome and Functional Dissection in Mouse Models. Cell Rep. 32(2), 107908 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.2015. AMP AD Target Discovery Data Portal. Synapse. [DOI]

- 32.Allen M, et al. Novel late-onset Alzheimer disease loci variants associate with brain gene expression. Neurology. 2012;79:221–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182605801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou F, et al. Brain expression genome-wide association study (eGWAS) identifies human disease-associated variants. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen M, et al. Late-onset Alzheimer disease risk variants mark brain regulatory loci. Neurol. Genet. 2015;1:e15. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng B, et al. An xQTL map integrates the genetic architecture of the human brain’s transcriptome and epigenome. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:1418–1426. doi: 10.1038/nn.4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ripke S, et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.2016. ROSMAP Study. Synapse. [DOI]

- 38.Allen M, et al. Conserved brain myelination networks are altered in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimers. Dement. 2018;14:352–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen M, et al. Divergent brain gene expression patterns associate with distinct cell-specific tau neuropathology traits in progressive supranuclear palsy. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:709–727. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1900-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.2016. Mayo RNAseq Study. Synapse. [DOI]

- 41.Leek JT, Storey JD. Capturing Heterogeneity in Gene Expression Studies by Surrogate Variable Analysis. Plos Genet. 2007;3:e161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCarthy S, et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1279–83. doi: 10.1038/ng.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Brien HE, et al. Expression quantitative trait loci in the developing human brain and their enrichment in neuropsychiatric disorders. Genome Biol. 2018;19:194. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1567-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hou Y, et al. Schizophrenia-associated rs4702 G allele-specific downregulation of FURIN expression by miR-338-3p reduces BDNF production. Schizophr. Res. 2018;199:176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dobbyn A, et al. Landscape of Conditional eQTL in Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex and Co-localization with Schizophrenia GWAS. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;102:1169–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pardiñas AF, et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:381–389. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0059-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, et al. Non-coding RNA dysregulation in the amygdala region of schizophrenia patients contributes to the pathogenesis of the disease. Transl. Psychiatry. 2018;8:44. doi: 10.1038/s41398-017-0030-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu AT, et al. Genetic architecture of epigenetic and neuronal ageing rates in human brain regions. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15353. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davies MN, et al. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue-specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hannon E, Lunnon K, Schalkwyk L, Mill J. Interindividual methylomic variation across blood, cortex, and cerebellum: implications for epigenetic studies of neurological and neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Epigenetics. 2015;10:1024–1032. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1100786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guintivano J, Aryee MJ, Kaminsky ZA. A cell epigenotype specific model for the correction of brain cellular heterogeneity bias and its application to age, brain region and major depression. Epigenetics. 2013;8:290–302. doi: 10.4161/epi.23924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Negi SK, Guda C. Global gene expression profiling of healthy human brain and its application in studying neurological disorders. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:897. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00952-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azevedo FAC, et al. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;513:532–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma S, Hsieh Y-P, Ma J, Lu C. Low-input and multiplexed microfluidic assay reveals epigenomic variation across cerebellum and prefrontal cortex. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaar8187. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar8187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Westra H-J, et al. Cell Specific eQTL Analysis without Sorting Cells. Plos Genet. 2015;11:e1005223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van der Wijst MGP, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies celltype-specific cis-eQTLs and co-expression QTLs. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:493–497. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang, J., Devlin, B. & Roeder, K. Using multiple measurements of tissue to estimate individual- and cell-type-specific gene expression via deconvolution. bioRxiv 379099, 10.1101/379099 (2018).

- 58.Li M, et al. Integrative functional genomic analysis of human brain development and neuropsychiatric risks. Science (80-.). 2018;362:eaat7615. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hansen KD, Irizarry RA, WU Z. Removing technical variability in RNA-seq data using conditional quantile normalization. Biostatistics. 2012;13:204–216. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxr054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47–e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. Voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pearson K. LIII. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. London, Edinburgh, Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1901;2:559–572. doi: 10.1080/14786440109462720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hotelling H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933;24:417–441. doi: 10.1037/h0071325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leek, J. T. et al. Bioconductor - sva., 10.18129/B9.bioc.sva (2018).

- 67.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chandler MJ, et al. A total score for the CERAD neuropsychological battery. Neurology. 2005;65:102–106. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167607.63000.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang CC, et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Das S, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1284–1287. doi: 10.1038/ng.3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Loh P-R, et al. Reference-based phasing using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1443. doi: 10.1038/ng.3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klei, L., Kent, B. P., Melhem, N., Devlin, B. & Roeder, K. GemTools: A fast and efficient approach to estimating genetic ancestry. (2011).

- 73.Lee AB, Luca D, Klei L, Devlin B, Roeder K. Discovering genetic ancestry using spectral graph theory. Genet. Epidemiol. 2010;34:51–59. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shabalin AA. Matrix eQTL: ultra fast eQTL analysis via large matrix operations. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1353–1358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Begum F, Ghosh D, Tseng GC, Feingold E. Comprehensive literature review and statistical considerations for GWAS meta-analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3777–3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O’Brien H, Bray NJ. 2018. Summary statistics for expression quantitative trait loci in the developing human brain and their enrichment in neuropsychiatric disorders. Figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Storey, J.D., Bass, A.J., Dabney, A. & Robinson, D. qvalue: Q-value estimation for false discovery rate controlhttp://github.com/jdstorey/qvalue (2020).

- 78.Sieberts S. 2019. ROSMAP DLPFC eQTL. Synapse. [DOI]

- 79.Sieberts S. 2019. Mayo Temporal Cortex eQTL. Synapse. [DOI]

- 80.Sieberts S. 2019. Mayo Cerebellum eQTL. Synapse. [DOI]

- 81.Sieberts S. 2019. Cortical eQTL Meta-analysis. Synapse. [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2015. CommonMind Consortium Data Release Portal. Synapse. [DOI]

- 2015. AMP AD Target Discovery Data Portal. Synapse. [DOI]

- 2016. ROSMAP Study. Synapse. [DOI]

- 2016. Mayo RNAseq Study. Synapse. [DOI]

- O’Brien H, Bray NJ. 2018. Summary statistics for expression quantitative trait loci in the developing human brain and their enrichment in neuropsychiatric disorders. Figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sieberts S. 2019. ROSMAP DLPFC eQTL. Synapse. [DOI]

- Sieberts S. 2019. Mayo Temporal Cortex eQTL. Synapse. [DOI]

- Sieberts S. 2019. Mayo Cerebellum eQTL. Synapse. [DOI]

- Sieberts S. 2019. Cortical eQTL Meta-analysis. Synapse. [DOI]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for the ROSMAP37 and Mayo cohorts40 are available through the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal31. Data for the MSSM-Penn-Pitt and HBCC cohorts are available through the CommonMind Knowledge Portal23.

eQTL results for the ROSMAP78, Mayo TCX79, Mayo CER80 and cortical meta-analysis81 are available through the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal. These results include SNP (location, rsid, alleles, and allele frequency) and gene (location, gene symbol, strand and biotype) information, as well as estimated effect size (beta), statistic (z), p-value, FDR, and expression-increasing allele.

An R package with all code for the gene expression normalization is available at https://github.com/Sage-Bionetworks/ampad-diffexp. All other analyses were generated using packages publicly available from their respective authors.