Abstract

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are known as one of the major classes of phytohormones essential for various processes during normal plant growth, development, and adaptations to biotic and abiotic stresses. Significant progress has been achieved on revealing mechanisms regulating BR biosynthesis, catabolism, and signaling in many crops and in model plant Arabidopsis. It is known that BRs control plant growth and development in a dosage-dependent manner. Maintenance of BR homeostasis is therefore critical for optimal functions of BRs. In this review, updated discoveries on mechanisms controlling BR homeostasis in higher plants in response to internal and external cues are discussed.

Keywords: brassinosteroids, phytohormones, homeostasis, cytochrome P450, transcriptional regulation

Introduction

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are a group of naturally occurring and polyhydroxylated phytosterols, carrying at least one oxygen moiety at the C3 position and additional ones at one or more of C2, C6, C22, and C23 carbon atoms (Bishop and Yokota, 2001). Since brassinolide (BL), the most active BR compound, was first isolated from Brassica napus pollen grains in 1970s, more than 70 BR compounds have been identified and they are ubiquitously presented in the plant kingdom (Mitchell et al., 1970; Grove et al., 1979; Bajguz and Tretyn, 2003). It is widely known that BRs regulate multiple processes during plant growth, development and environmental adaptations, especially controlling many important agronomic traits such as plant architecture, flowering time, seed yield, and stress tolerance (Clouse and Sasse, 1998; Tong and Chu, 2018). Therefore, genetic control of endogenous BR levels or signaling offers a novel approach for crop improvement.

Although application of limited amounts of BRs can significantly enhance growth, excessive BRs are usually harmful to plant growth and development (Clouse et al., 1996). Maintenance and regulation of endogenous BR levels are therefore essential for optimal plant growth and development. Considering that BRs cannot undergo long distance transport, BR biosynthesis and catabolism are two critical antagonistic processes for maintaining BR homeostasis in plants (Symons and Reid, 2004; Ye et al., 2011; Zhao and Li, 2012). In the past decades, extensive researches have been conducted to elucidate the BR biosynthesis pathway in many plant species. Various enzymes catabolizing bioactive BRs through acylation, sulfonation, glycosylation, or other manners in these plants have also been identified. This review focuses on the recent advances in our understanding of the dynamic regulation of BR homeostasis in higher plants in response to various internal and external factors. These pieces of information can be used to facilitate BR application in molecular design for modern agriculture.

BR Biosynthesis Pathways

BRs are classified as C27, C28, and C29 steroids based on the structure of their C24 alkyl groups (Fujioka and Yokota, 2003). C28 BRs, such as castasterone (CS) and BL, are the most abundant and ubiquitous BRs in plants. Synthesis of CS and BL from campesterol, one of the plant sterols, has been clearly elucidated and is discussed in detail. C27 and C29 BRs use two other compounds, cholesterol, and sitosterol, as their corresponding precursors, and may go through pathways similar to those of C28 BRs (Sakurai, 1999; Fujioka and Yokota, 2003).

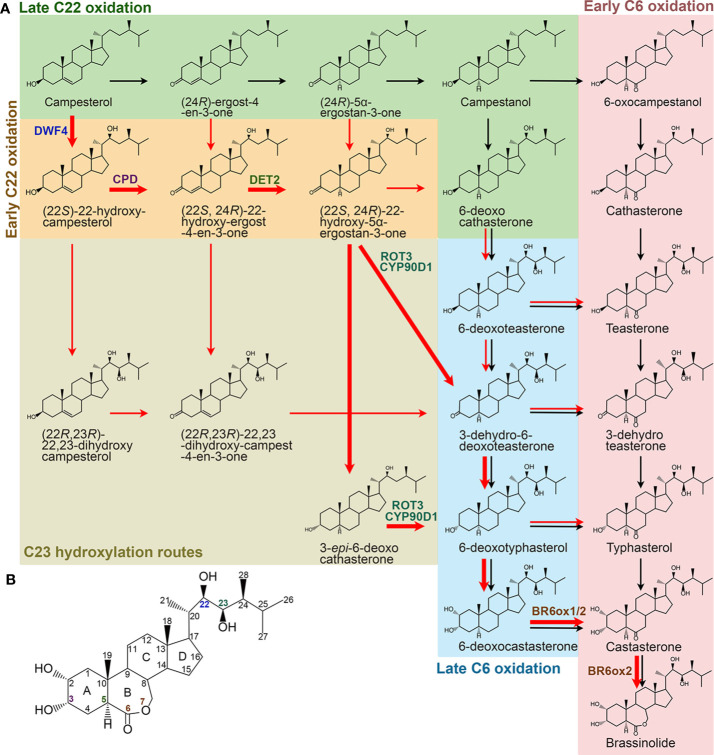

Sterol Biosynthesis From Cycloartenol to Campesterol and Sitosterol

The Common Steps

Plant sterols are synthesized from cycloartenol, a plant-specific C30 sterol derived from squalene (Figure 1). Most of the enzymes involved in the phytosterol biosynthetic pathway have been characterized in different plant species (Table 1). (1) Squalene epoxidase (SQE) catalyzes the oxidation of squalene to squalene-2,3-oxide (Rasbery et al., 2007; Pose et al., 2009; Unland et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020a). (2) Conversion of squalene-2,3-oxide into cycloartenol is catalyzed by a cycloartenol synthase (Corey et al., 1993; Babiychuk et al., 2008; Gas-Pascual et al., 2014). (3) The first C24 methylation reaction converts cycloartenol into 24-methylene cycloartenol (Shi et al., 1996; Diener et al., 2000; Holmberg et al., 2002; Schrick et al., 2002; Willemsen et al., 2003; Guan et al., 2017). This rate-limiting methylation step leads to subsequent synthesis of 24-methyl (campesterol) or 24-ethyl (sitosterol) instead of 24-desmethyl sterol (cholesterol). The second C24 methylation reaction after several steps determines the formation of 24-ethyl sterols instead of 24-methyl sterols. (4) Cycloeucalenol is produced from 24-methylene cycloartenol through demethylation at C4 position, which is performed with the sequential participation of three enzymes, a sterol 4α-methyl oxidase (SMO), a 4α-carboxysterol-C3-dehydrogenase/C4-decarboxylase (CSD), and a sterone ketoreductase (Darnet et al., 2001; Darnet and Rahier, 2004; Rahier, 2011; Song et al., 2019). Removal of the two methyl groups at C4 position is essential for sterols to be functional. The two separate C4 demethylation reactions in higher plants are catalyzed by two distinctive families of SMO enzymes, whereas the two consecutive C-4 demethylation reactions are catalyzed by the same enzymes in animals and fungi (Rahier, 2011). (5) Cycloeucalenol is then isomerized by cyclopropyl sterol isomerase. As a result, obtusifoliol is produced (Lovato et al., 2000; Men et al., 2008). (6) Subsequently, CYP51, one of the most ancient and conserved cytochrome P450s across the kingdoms, demethylates obtusifoliol at C14 to form 4α-methyl ergostatrienol (Kahn et al., 1996; Bak et al., 1997; Cabello-Hurtado et al., 1999; Kushiro et al., 2001; Burger et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005a). (7) C14 reduction of 4α-methyl ergostatrienol is catalyzed by FACKEL/HYDRA2/EXTRA-LONG-LIFESPAN 1 (FK/HYD2/ELL1), three alleles from Arabidopsis isolated by independent research groups, leading to formation of 4α-methyl fecosterol (Jang et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2000; Souter et al., 2002). (8) Isomerization of 4α-methyl fecosterol into 24-methylene lophenol is catalyzed by a Δ8-Δ7 sterol isomerase, identified as HYDRA1 (HYD1) in Arabidopsis (Souter et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis of campesterol and sitosterol from squalene. Numbers correspond to the description in the text and Table 1. Enzymes identified from higher plants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sterol biosynthesis enzymes identified in different plant species.

| Function | Species | Name | Steps* | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squalene epoxidase | Arabidopsis thaliana | SQE1 | 1 | Rasbery et al., 2007; Pose et al., 2009 |

| Tripterygium wilfordii | TwSQE6/7 | 1 | Liu et al., 2020a | |

| Taraxacum koksaghyz | TkSQE1 | 1 | Unland et al., 2018 | |

| Cycloartenol synthase | Arabidopsis thaliana | CAS1 | 2 | Corey et al., 1993; Babiychuk et al., 2008 |

| Nicotiana tabacum | NtCAS1 | 2 | Gas-Pascual et al., 2014 | |

| Sterol methyltransferase | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtSMT1/CPH/ORC | 3 | Diener et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2002; Willemsen et al., 2003 |

| CVP1/SMT2/3 | 13 | Husselstein et al., 1996; Bouvier-Navé et al., 1997; Schaller et al., 1998; Carland et al., 1999; Schaeffer et al., 2001; Carland et al., 2002; Carland et al., 2010 | ||

| Glycine max | SMT1 | 3 | Shi et al., 1996 | |

| Nicotiana tabacum | NtSMT1 | 3 | Holmberg et al., 2002 | |

| Tripterygium wilfordii | TwSMT1 | 3 | Guan et al., 2017 | |

| Gossypium hirsuturm | GhSMT2-1/2-2 | 3 | Luo et al., 2008 | |

| Sterol 4α-methyl oxidase | Arabidopsis thaliana | SMO1 | 4 | Darnet et al., 2001; Darnet and Rahier, 2004; Song et al., 2019 |

| SMO2 | 9/14 | Zhang et al., 2016 | ||

| Cyclopropyl sterol isomerase | Arabidopsis thaliana | CPI1 | 5 | Lovato et al., 2000; Men et al., 2008 |

| 14α‐demethylase | Arabidopsis thaliana | CYP51A2 | 6 | Kushiro et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2005a |

| Oryza sativa | OsCYP51G3 | 6 | Xia et al., 2015 | |

| Sorghum bicolor | CYP51 | 6 | Kahn et al., 1996; Bak et al., 1997 | |

| Triticum aestivum | CYP51 | 6 | Cabello-Hurtado et al., 1999 | |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | CYP51 | 6 | Burger et al., 2003 | |

| C14 reductase | Arabidopsis thaliana | FK/HYD2/ELL1 | 7 | Jang et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2000; Souter et al., 2002 |

| Δ8-Δ7 sterol isomerase | Arabidopsis thaliana | HYD1 | 8 | Souter et al., 2002 |

| C5 desaturase | Arabidopsis thaliana | DWF7/STE1/BUL1 | 10/15 | Gachotte et al., 1995; Choe et al., 1999b; Catterou et al., 2001a; Catterou et al., 2001b |

| C7 reductase | Arabidopsis thaliana | DWF5 | 11/16 | Choe et al., 2000 |

| Δ24 isomerase/reductase | Arabidopsis thaliana | DWF1/CBB1/DIM | 12/17 | Takahashi et al., 1995; Kauschmann et al., 1996; Klahre et al., 1998; Choe et al., 1999a |

| Oryza sativa | BRD2/LTBSG1/LHDD10 | 12/17 | Hong et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2016; Qin et al., 2018 | |

| Pyrus ussuriensis | PcDWF1 | 12/17 | Zheng et al., 2020 | |

| Hordeum vulgare | HvDIM | 12/17 | Dockter et al., 2014 | |

| Zea mays | NA2 | 12/17 | Best et al., 2016 |

*Step numbers correspond to the description in the text and Figure 1.

The Campesterol Branch

(9) Removal of the second methyl group at C4 converts 24-methylene lophenol into episterol, which involves a family of SMO enzymes distinctive from the first C4 demethylation reaction (Zhang et al., 2016). (10) Episterol is subsequently converted into 5-dehydro episterol by a C5 desaturase, named DWARF7/STE1/BOULE1 (DWF7/STE1/BUL1) in Arabidopsis (Gachotte et al., 1995; Choe et al., 1999b; Catterou et al., 2001b; Catterou et al., 2001a). (11) C7 reductase, also designated as DWARF5 (DWF5) in Arabidopsis, reduces 5-dehydro episterol to yield 24-methylene cholesterol (Choe et al., 2000). (12) The Δ24(28) bond of 24-methylene cholesterol is isomerized into a Δ24(25) bond, and then the double bond is reduced to produce campesterol, the specific precursor of BR biosynthesis. Both the isomerization and reduction are catalyzed by a single enzyme, named as DWF1/CBB1/DIM and BRD2/LTBSG1/LHDD10 in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively (Takahashi et al., 1995; Kauschmann et al., 1996; Klahre et al., 1998; Choe et al., 1999a; Hong et al., 2005; Best et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016; Qin et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2020).

The Sitosterol Branch

(13) The first step of sitosterol branch is the second C24 methylation reaction in the plant sterol biosynthesis pathway that converts 24-methylene lophenol into 24-ethylidene lophenol, the fundamental member of 24-ethyl sterols (Husselstein et al., 1996; Bouvier-Navé et al., 1997; Schaller et al., 1998; Carland et al., 1999; Schaeffer et al., 2001; Carland et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2008; Carland et al., 2010). (14-17) Subsequent four consecutive steps, including C4 demethylation, C5 desaturation, C7 reduction, and C24 isomerization/reduction, leads to the final biosynthesis of sitosterol. These four steps are catalyzed by the same enzymes functioning in the parallel campesterol branch (Klahre et al., 1998; Choe et al., 1999b; Choe et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2016).

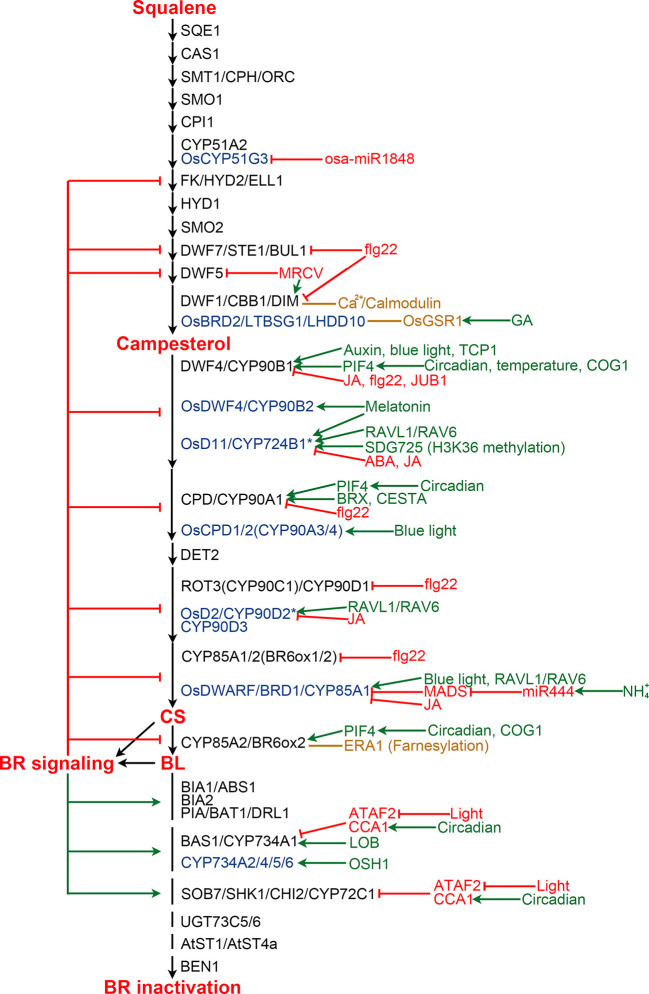

Specific Biosynthesis of BL From Campesterol

BR biosynthesis involves parallel and highly networked pathways (Figure 2). Campesterol can be first converted into campestanol (CN) through a late C22 oxidation pathway. CN in turn is converted to CS either via an early C6 oxidation or a late C6 oxidation pathway, which is also called a CN-dependent pathway (Fujioka and Yokota, 2003). On the other hand, campesterol can be first converted into 6-deoxocathasterone through an early C22 oxidation pathway, either flowing straightly or via a C23 hydroxylation reaction step then going into the C6 oxidation pathways to synthesize CS, which is also designated as a CN-independent pathway (Fujioka et al., 2002; Fujita et al., 2006; Ohnishi et al., 2006b). CS is the end and most bioactive BR compound in graminaceous plants, such as rice (Kim et al., 2008). Whereas, CS can further be converted into BL in most dicotyledonous plants due to the duplication of a C6 oxidase gene, one of their encoded C6 oxidases developed a BL synthase function (Kim et al., 2005b; Nomura et al., 2005). Compared with their parallel branches, the early C22 oxidation pathway and the late C6 oxidation pathway appear to be the predominant route in many plant species, including Arabidopsis, tomato, and pea (Nomura et al., 2001; Fujioka et al., 2002). Furthermore, the C23 hydroxylases prefer to use (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-5α-ergostan-3-one and 3-epi-6-deoxocathasterone as their substrates (Ohnishi et al., 2006b). Thus, the most dominant and efficient flow of BR intermediates, campesterol → (22S)-22-hydroxy-campesterol → (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-ergost-4-en-3-one → (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-5α-ergostan-3-one → 3-epi-6-deoxocathasterone/3-dehydro-6-deoxoteasterone → 6-deoxotyphasterol → 6-deoxocastasterone → CS → BL, is established (Ohnishi et al., 2012). Although there are two more steps in other biosynthetic routes compared with this dominant CN-independent pathway, all the BR biosynthesis routes involve common reaction steps, including hydroxylation at C22, C23, and C2, oxidation and reduction at C3, reduction at C5, and oxidation at C6, and an additional Baeyer-Villiger oxidation in most dicotyledonous plants. Most of the enzymes involved in the reactions were identified in different plant species (Table 2). Loss of function of these enzymes leads to similar defective phenotypes, including dwarf and compact plant architecture, short roots, delayed flowering time, reduced biomass and seed yield.

Figure 2.

Specific BR biosynthetic pathways from campesterol in higher plants. (A) Black and red arrows represent CN-dependent and -independent pathways, respectively. Bold red arrows represent the most dominant and efficient flow of the BR intermediates. Enzymes identified from Arabidopsis are only shown in the dominant routes. (B) Molecular structure of BL. The carbons are numbered and the rings are labelled by letters. Colors of the number correspond to the enzymes shown in (A).

Table 2.

Specific BR biosynthesis enzymes identified in different plant species.

| Function | Species | Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| C22 hydroxylase | Arabidopsis thaliana | DWF4/CYP90B1 | Choe et al., 1998; Fujita et al., 2006 |

| CYP724A1 | Zhang et al., 2012 | ||

| Oryza sativa | CYP90B2/OsDWF4 | Sakamoto et al., 2006 | |

| CYP724B1/D11* | Sakamoto et al., 2006 | ||

| Lycopersicon esculentum | CYP90B3 | Ohnishi et al., 2006c | |

| CYP724B2 | Ohnishi et al., 2006c | ||

| Zea mays | CYP90B2/ZmDWF4 | Liu et al., 2007 | |

| Solanum tuberosum | StDWF4 | Zhou et al., 2018 | |

| Populus tomentosa | PtoDWF4 | Shen et al., 2018 | |

| C23 hydroxylase | Arabidopsis thaliana | CYP90C1/ROT3 CYP90D1 |

Ohnishi et al., 2006b |

| Oryza sativa | CYP90D2/OsD2* CYP90D3 |

Sakamoto et al., 2012 | |

| Lycopersicon esculentum | DPY | Koka et al., 2000 | |

| C2 hydroxylase | Pisum sativum | CYP92A6/DDWF1 | Kang et al., 2001 |

| C3 oxidase | Arabidopsis thaliana | CYP90A1/CPD | Szekeres et al., 1996; Ohnishi et al., 2012 |

| Oryza sativa | CYP90A3/4(OsCPD1/2) | Sakamoto and Matsuoka, 2006 | |

| CYP90D2/OsD2* | Hong et al., 2003; Li et al., 2013 | ||

| Hordeum vulgare | HvCPD | Dockter et al., 2014 | |

| C3 reductase | Oryza sativa | CYP724B1/OsD11* | Tanabe et al., 2005 |

| C5 reductase | Arabidopsis thaliana | DET2 | Chory et al., 1991; Fujioka et al., 1997; Noguchi et al., 1999 |

| Glycine max | GmDET2a/b | Huo et al., 2018 | |

| Gossypium hirsuturm | GhDET2 | Luo et al., 2007 | |

| Cucumis sativus | CsDET2 | Hou et al., 2017 | |

| Pisum sativum | LK | Nomura et al., 2004 | |

| Pharbitis nil | PnDET2 | Suzuki et al., 2003 | |

| C6 oxidase | Arabidopsis thaliana | CYP85A1/2 (BR6ox1/2) | Shimada et al., 2001 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum | CYP85A1(DWARF)/A3 | Bishop et al., 1999; Shimada et al., 2001 | |

| Pisum sativum | PsCYP85A1/6 | Jager et al., 2007 | |

| Oryza sativa | OsDWARF/BRD1 | Hong et al., 2002; Mori et al., 2002 | |

| Hordeum vulgare | HvBRD | Dockter et al., 2014 | |

| Cucumis sativus | SCP1/CsCYP85A1 | Wang et al., 2017 | |

| Brachypodium distachyon | BdBRD1 | Xu et al., 2015 | |

| Zea mays | ZmBRD1 | Makarevitch et al., 2012 | |

| Populus trichocarpa | PtCYP85A3 | Jin et al., 2017 |

Enzymes marked by an asterisk are those with controversial functions.

Hydroxylation at C22, C23, and C2

There are at least five C22 hydroxylation reactions in the BR biosynthesis pathway, including campesterol to (22S)-22-hydroxy-campesterol, (24R)-ergost-4-en-3-one to (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-ergost-4-en-3-one, (24R)-5α-ergostan-3-one to (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-5α-ergostan-3-one, CN to 6-deoxocathasterone, and 6-oxocampestanol to cathasterone (Choe et al., 1998; Fujita et al., 2006; Ohnishi et al., 2006c). Although all these C22 hydroxylation reactions are catalyzed by the same cytochrome P450 monooxygenases in different plants, they prefer to take campesterol rather than others as a substrate (Choe et al., 1998; Fujita et al., 2006; Ohnishi et al., 2006c). In Arabidopsis, CYP90B1, a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase also known as DWARF4 (DWF4), is mainly responsible for these reactions (Choe et al., 1998; Fujita et al., 2006). CYP724A1 function at least partially as a C22 hydroxylase, since its overexpression can restore the deficiency caused by dwf4 mutation (Zhang et al., 2012). Homologs of CYP90B1/DWF4 and CYP724A1 in different plant species, such as CYP90B2/OsDWF4 and CYP724B1/OsD11 in rice, CYP90B3 and CYP724B2 in tomato, CYP90B2/ZmDWF4 in maize, StDWF4 in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), and PtoDWF4 in Populus tomentosa, were also found to possess similar biological functions (Ohnishi et al., 2006c; Sakamoto et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018). The C22 hydroxylation is considered as a rate-limiting step in the BR biosynthesis pathway possibly due to a low DWF4 expression level that cannot effectively catalyze the reaction (Choe et al., 1998). This makes DWF4 an ideal target for manipulating BR biosynthesis to regulate growth and stress adaptation in modern agriculture (Choe et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2006; Sakamoto et al., 2006; Sahni et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018).

Six C23 hydroxylation reactions, including (22S)-22-hydroxy-campesterol to (22R, 23R)-22, 23-dihydroxy-campesterol, (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-ergost-4-en-3-one to (22R, 23R)-22, 23-dihydroxy-campest-4-en-3-one, (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-5α-ergostan-3-one to 3-dehydro-6-deoxoteasterone, 3-epi-6-deoxocathasterone to 6-deoxotyphasterol, 6-deoxocathasterone to 6-deoxoteasterone, and cathasterone to teasterone, were identified in the BR biosynthesis pathway (Ohnishi et al., 2006b; Sakamoto et al., 2012). (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-5α-ergostan-3-one and 3-epi-6-deoxocathasterone are two favorable substrates for the C23 hydroxylases in plants, leading to a shortcut with two steps less than other biosynthetic routes (Ohnishi et al., 2006b; Sakamoto et al., 2012). The C23 hydroxylases are also members of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases, such as CYP90C1/ROTUNDIFOLIA3 (ROT3) and CYP90D1 in Arabidopsis, CYP90D2/OsD2 and CYP90D3 in rice, and CYP90C2/DUMPY (DPY) in tomato (Koka et al., 2000; Ohnishi et al., 2006b; Sakamoto et al., 2012).

The C2 hydroxylation steps, converting 6-deoxotyphasterol to 6-deoxocastasterone and typhasterol to castasterone located in the late and the early C6 oxidation pathways respectively, have only been elucidated in pea (Kang et al., 2001). A dark-induced cytochrome P450, named as DARK-INDUCED DWF-LIKE PROTEIN 1 (DDWF1), is activated by a small G protein PRA2 and then to catalyze the C2 hydroxylation reactions in the BR biosynthetic pathway (Kang et al., 2001).

Oxidation and Reduction at C3

At least twice redox reactions at C3 position were found in the BR biosynthetic pathway. The big difference between the dominant CN-independent route from others is that it contains one less C3 redox reaction (Ohnishi et al., 2012). The first time of C3 oxidation reactions include campesterol to (24R)-ergost-4-en-3-one, (22S)-22-hydroxy-campesterol to (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-ergost-4-en-3-one, and (22R, 23R)-22, 23-dihydroxycampesterol to (22R, 23R)-22, 23-dihydroxy-campest-4-en-3-one. Conversions from 6-deoxoteasterone to 3-dehydro-6-deoxoteasterone and from teasterone to 3-dehydroteasterone in the late and the early C6 oxidation pathways, respectively, are the second C3 oxidation reactions. In Arabidopsis, CYP90A1/CPD is responsible for the C3 oxidation and has a broad substrate specificity. Three of the five intermediates, (22S)-22-hydroxy-campesterol, (22R, 23R)-22, 23-dihydroxycampesterol, and 6-deoxoteasterone, can be converted to their respective 3-dehydro derivatives by CYP90A1/CPD, whereas, its preferred substrate is (22S)-22-hydroxy-campesterol (Szekeres et al., 1996; Ohnishi et al., 2012). Rice CYP90A3/OsCPD1 and CYP90A4/OsCPD2 were predicted to perform the similar function as Arabidopsis CYP90A1/CPD based on their high sequence similarity (Sakamoto and Matsuoka, 2006). However, rice CYP90D2/OsD2 is considered as the C3 oxidase for 6-deoxoteasterone and teasterone by two research groups, while another research group demonstrated that it functions redundantly with CYP90D3 as a C23 hydrolase (Hong et al., 2003; Sakamoto et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013).

C3 reductions include conversions from (24R)-5α-ergostan-3-one to campestanol, (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-5α-ergostan-3-one to 6-deoxocathasterone or 3-epi-6-deoxocathasterone, 3-dehydro-6-deoxoteasterone to 6-deoxotyphasterol, and 3-dehydroteasterone to typhasterol. In rice, CYP724B1/OsD11 is originally reported as the C3 reductase to produce 6-deoxotyphasterol and typhasterol (Tanabe et al., 2005). However, a different research group declared that it catalyzes the C22 hydroxylation together with CYP90B2/OsDWF4 (Sakamoto et al., 2006). The BR C3 reductase in Arabidopsis model plant is yet to be identified in the future.

C5 Reduction

C5 reduction is an early reaction step in the BR biosynthesis pathway, leading to the formation of (24R)-5α-ergostan-3-one, (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-5α-ergostan-3-one, and 3-dehydro-6-deoxoteasterone from (24R)-ergost-4-en-3-one, (22S, 24R)-22-hydroxy-ergost-4-en-3-one, and (22R, 23R)-22, 23-dihydroxy-campest-4-en-3-one, respectively. A steroid 5α-reductase, named as DEETIOLATION 2 (DET2), is responsible for the C5 reduction in Arabidopsis (Chory et al., 1991; Li et al., 1996; Fujioka et al., 1997; Li et al., 1997; Noguchi et al., 1999). Paralogs of DET2 in different plant species have also been identified, such as in soybean, cotton, cucumber, pea, and morning glory (Suzuki et al., 2003; Nomura et al., 2004; Luo et al., 2007; Hou et al., 2017; Huo et al., 2018).

C6 Oxidation and Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation

C6 oxidation converts the 6-deoxo BR intermediates in the late C6 oxidation pathway to corresponding 6-oxo compounds in the early C6 oxidation pathway. Although several pairs of substates and products seem to occur naturally in a number of plant species, only the conversion from 6-deoxotyphasterol to typhasterol and from 6-deoxocastasterone to castasterone have been verified in Arabidopsis and rice (Shimada et al., 2001; Mori et al., 2002). Conversions from 6-deoxoteasterone to teasterone and from 3-dehydro-6-deoxoteasterone to 3-dehydroteasterone were also thought to occurr but remain tentative in Arabidopsis and possibly other plants (Shimada et al., 2001). Whereas, in tomato, conversion from 6-deoxocastasterone to castasterone seems to be the only major C6 oxidation pathway (Bishop et al., 1999; Shimada et al., 2001). The C6 oxidases encoded by cytochrome P450s have been identified in different plant species, such as CYP85A1/2 (also name as BR6ox1/2) in Arabidopsis, DWARF/CYP85A1 and CYP85A3 in tomato, PsCYP85A1 and PsCYP85A6/LKE in pea, OsDWARF/BRD1 in rice, SCP1/CsCYP85A1 in cucumber, HvBRD in barley, BdBRD1 in Brachypodium distachyon, ZmBRD1 in maize, PtCYP85A3 in Populus trichocarpa, and so on (Bishop et al., 1999; Shimada et al., 2001; Hong et al., 2002; Mori et al., 2002; Jager et al., 2007; Makarevitch et al., 2012; Dockter et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). It should be noted that the C6 oxidation is also a rate-limiting step in the BR biosynthesis pathway (Nomura et al., 2001).

The Baeyer-Villiger oxidation creates a lactone at ring B of the steroid backbone, leading to the formation of BL from CS in Arabidopsis and tomato but not in rice (Kim et al., 2005b; Nomura et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2008). Consistently, there is only one copy of CYP85A gene in rice, while there are two copies of CYP85As in Arabidopsis and tomato genomes. It has been elucidated that the extra CYP85A enzymes, CYP85A2/BR6ox2 in Arabidopsis and CYP85A3 in tomato, are responsible for the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation (Kim et al., 2005b; Nomura et al., 2005).

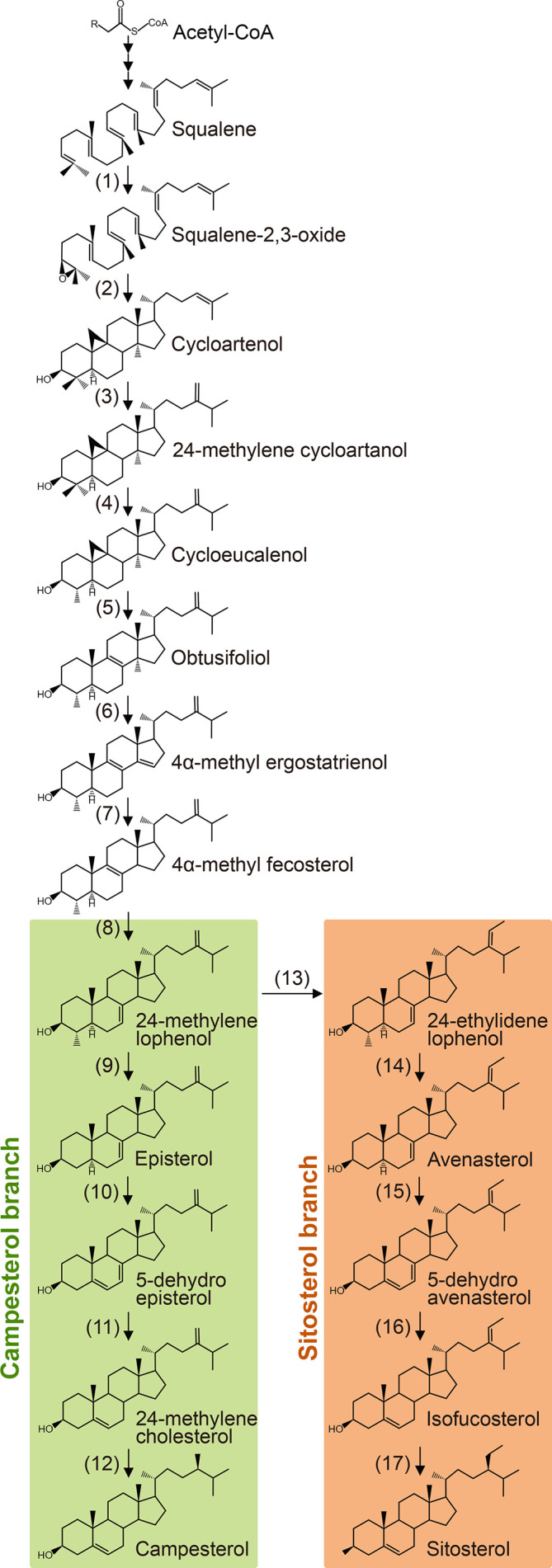

Regulation of BR Biosynthesis

BR biosynthesis is inhibited by the end product, CS or BL, via a feedback loop (Figure 3). Exogenous application of BL leads to down-regulation of multiple BR biosynthetic genes, while BR biosynthesis inhibitors induce the expression of these genes, suggesting feedback transcriptional regulation occurs at multiple steps of the BR biosynthesis pathway (Mathur et al., 1998; Hong et al., 2002; Hong et al., 2003; Tanabe et al., 2005; Tanaka et al., 2005). Now, it is clear that perception of BL by its receptor BRI1 and coreceptor BAK1 ultimately leads to the activation of a group of transcription factors, including BES1 and BZR1, in the nucleus (Li and Chory, 1997; Li et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002). BES1 and BZR1 not only regulate the expression of thousands of genes involved in diverse processes during plant growth and development, but also are responsible for the feedback inhibition via directly binding to the promoter regions of multiple BR biosynthesis genes to repress their expression (He et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2011).

Figure 3.

Regulation of BR biosynthesis and catabolism in Arabidopsis and rice. BR biosynthesis pathway is shown from squalene to BL. Enzymes from Arabidopsis and rice are shown in black and blue colors, respectively. Enzymes marked by an asterisk are those with controversial functions. Enzymes from other plants are list in Table 2 and Table 3. Green and red arrows indicate positive and negative regulation, respectively. Orange lines represent protein-protein interaction.

The BR biosynthesis pathway is regulated by various internal signaling molecules and by its end products (Figure 3). For example, auxin induces DWF4 expression to increase endogenous BR level in Arabidopsis roots, partially by repressing the binding of BZR1 to the DWF4 promoter (Chung et al., 2011). BREVIS RADIX (BRX) mediates auxin action on BR biosynthesis through activating the CPD expression in Arabidopsis (Mouchel et al., 2006). Gibberellins (GAs) have also been reported to play roles in regulating BR biosynthesis. OsGSR1, a GAST member (a GA-stimulated transcript) induced by GA and repressed by BR at a transcription level, interacts with DIM/DWF1 to modulate the BR level in rice (Wang et al., 2009). SPINDLY, an O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase negatively regulating GA signaling in rice, represses BR biosynthesis via an unknown mechanism (Shimada et al., 2006). JUNGBRUNNEN1 (JUB1), a NAC transcriptional regulator, acts at the nexus of BR-GA network by regulating a complex transcriptional module composed of key components of GA and BR pathways including GA3ox1, DWF4 and the DELLA genes GAI and RGL1 (Shahnejat-Bushehri et al., 2016). Moreover, the functional mechanism of JUB1 in regulating BR/GA biosynthesis and signaling is considerably conserved across species (Shahnejat-Bushehri et al., 2017). Jasmonic acid and abscisic acid were found to inhibit the expression of BR biosynthetic genes to antagonize BR functions (Ren et al., 2009; Gan et al., 2015; Li et al., 2019). Melatonin also plays a role in regulating BR biosynthesis. Block of its biosynthesis results in a decreased BR level in rice, while exogenously applied melatonin induces the expression of BR biosynthesis genes (Hwang and Back, 2018; Hwang and Back, 2019; Lee and Back, 2019).

Pieces of evidence support that light plays an important role in regulating BR biosynthesis. In rice aerial tissues, blue light promotes expression of CYP85A1/BRD1/OsDWARF and OsCYP90A3/4, thereby increasing CS level. While, far-red light, instead of blue light or red light, positively regulate BR biosynthesis in rice roots (Asahina et al., 2014). However, in Arabidopsis, blue light perception in aerial tissues enhances DWF4 accumulation in the root tips (Sakaguchi and Watanabe, 2017; Sakaguchi et al., 2019). Moreover, the expression levels of Arabidopsis CPD and CYP85A2/BR6ox2 display complex diurnal patterns (Bancos et al., 2006). A recent study revealed that BES1 inhibits the expression of BR biosynthesis genes during the day, while elevated PIF4 competes for BES1 resulting in de-repressed BR biosynthesis at dawn (Martinez et al., 2018). In addition, it was found that PIF5 acts redundantly with PIF4 to positively regulate BR biosynthesis. COG1, a Dof type transcription factor negatively regulating phytochrome signaling, can directly promote the expression of PIF4 and PIF5. PIF4 and PIF5 then directly bind to the promoters of DWF4 and CYP85A2/BR6ox2 to enhance their expression, resulting in elevated levels of endogenous BRs (Park et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2017). It was demonstrated that PIF4 also activates the expression of BR biosynthesis genes in response to elevated temperatures to promote thermomorphogenic hypocotyl growth (Maharjan and Choe, 2011; Martinez et al., 2018).

BR biosynthesis is highly regulated by different environmental stimuli as well as light. For instance, ammonium (NH4+), one of the major nitrogen resources for plants, induces the accumulation of miR444, which then positively regulates rice BR biosynthesis via inhibiting its MADS-box targets and subsequently activating OsBRD1 expression (Jiao et al., 2020). Calmodulin, a Ca2+ sensor protein which plays an essential role in sensing and transducing environmental stimuli, can interact with DWF1 in a Ca2+-dependent manner and control its function to regulate BR biosynthesis (Du and Poovaiah, 2005). Bacterial flagellin 22 triggers plant immunity responses, resulting in reduced expression of several BR biosynthetic genes, including CPD, DWF4, BR6ox1/2, ROT3, DWF1, and DWF7 in Arabidopsis (Jimenez-Gongora et al., 2015). Mal de Río Cuarto virus (MRCV) causes severe diseases in several monocotyledonous crops. It was found that MRCV infection causes the up-regulation of DIM/DWF1 but the down-regulation of DWF5, and significantly increased amount of BL in wheat (de Haro et al., 2019).

Several additional components regulating BR biosynthesis were identified from different plant species. However, their upstream signaling is yet to be elucidated in the future. In Arabidopsis, TCP1, a basic helix loop helix (bHLH) transcription factor, can directly bind to the promoter of DWF4 to enhance its expression and promotes BR biosynthesis (Guo et al., 2010; An et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2015). CESTA, another bHLH transcription factor, positively regulates BR biosynthesis via promoting the expression of CPD (Poppenberger et al., 2011). Farnesylation, a post-translational modification, of Arabidopsis CYP85A2/BR6ox2 was found to be essential for its subcellular localization and function. Loss of CYP85A2/BR6ox2 farnesylation results in reduced BL accumulation, similar to the mutation of CYP85A2/BR6ox2 (Northey et al., 2016; Jamshed et al., 2017). In rice, RAVL1 and RAV6, two homologous B3 transcription factors, mediate activation of both OsBRI1 and the BR biosynthetic genes that have antagonistic actions on BR levels to ensure the basal activity of the BR signaling and biosynthetic pathways (Il Je et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2015). Rice microRNA osa-miR1848 mediates OsCYP51G3 mRNA cleavage to regulate phytosterol and BR biosynthesis (Xia et al., 2015). SDG725, a H3K36 methyltransferase from rice, modulates the expression of OsD11, suggesting an important role of H3K36 methylation on BR biosynthesis (Sui et al., 2012). In addition, both SLG and XIAO, predicted to be a BAHD acyltransferase-like protein and a leucine-rich repeat protein like kinase (LRR-RLK), respectively, function as the positive regulators of BR biosynthesis via unknown mechanisms (Jiang et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2016). In wheat, TaSPL8 binds to the promoter of CYP90D2/OsD2 to activate its expression and regulate leaf angle (Liu et al., 2019). In cotton, GhFP1, a bHLH transcription factor, directly binds to the promoters of GhDWF4 and GhCPD to activate their expression (Liu et al., 2020b). In apple, MdWRKY9 directly represses MdDWF4 transcription to inhibit BR biosynthesis (Zheng et al., 2018). MdNAC1 negatively modulates BR production probably by inhibiting the expression of MdDWF4 and MdCPD (Jia et al., 2018).

Catabolism

BR Catabolism

Endogenous bioactive levels of BRs are also controlled by their catabolic processes. BR catabolism leads to decreased levels of bioactive BRs and attenuated signaling output. Elucidation of BR catabolism can help us, from a different aspect, to understand how plants regulate BR homeostasis for their optimal growth, development and environmental adaptations. Diverse modifications of BRs were revealed by various feeding experiments and analytic chemistry analyses, such as epimerization of C2 and C3 hydroxy groups, hydroxylation of C20, C25, and C26, side chain cleavage; sulfonation of C22; conjugation with fatty acids or glucose; acylation; demethylation; and so on (Fujioka and Yokota, 2003). At present, several BR inactivating reactions and some of their corresponding enzymes have been demonstrated in plants (Table 3). In Arabidopsis, at least 10 BR inactivating enzymes with different or similar biochemical mechanisms have been identified. Overexpression of these BR catabolic genes leads to BR deficiency, whereas loss of function of these enzymes results in elevated amounts of BL or CS in plants.

Table 3.

BR metabolism enzymes in different plant species.

| Function | Species | Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyltransferase | Arabidopsis thaliana | BIA1/ABS1 | Roh et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012 |

| BIA2 | Zhang and Xu, 2018 | ||

| PIZ/BAT1/DRL1 | Schneider et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013 | ||

| C26 hydroxylase | Arabidopsis thaliana | BAS1/CYP734A1 | Neff et al., 1999; Turk et al., 2003 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum | CYP734A7 | Ohnishi et al., 2006a | |

| Oryza sativa | CYP734A2/4/5/6 | Sakamoto et al., 2011 | |

| Gossypium hirsuturm | PAG1 | Yang et al., 2014 | |

| Daucus carota | DcBAS1 | Que et al., 2019 | |

| Sulfotransferase | Brassica napus | BNST3/4 | Rouleau et al., 1999; Marsolais et al., 2004 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtST1/AtST4a | Marsolais et al., 2007 | |

| Glycosyltransferase | Arabidopsis thaliana | UGT73C5 | Poppenberger et al., 2005 |

| UGT73C6 | Husar et al., 2011 | ||

| Unknown | Arabidopsis thaliana | CYP72C1/SOB7/SHK1/CHI2 | Nakamura et al., 2005; Takahashi et al., 2005; Turk et al., 2005 |

| Unknown | Arabidopsis thaliana | BEN1 | Yuan et al., 2007 |

Hydroxylases

C26 hydroxylation is a relatively well characterized way of BR inactivation. Arabidopsis BAS1/CYP734A1 (formerly named CYP72B1) is the first reported BR C26 hydroxylase as revealed by the feeding experiment. It is able to convert both CS and BL to their C26 hydroxylated derivatives (Neff et al., 1999; Turk et al., 2003). Such modification possibly prevents the side chain of BRs from fitting into the binding pocket of the receptor, BRI1 (Hothorn et al., 2011; She et al., 2011). Tomato CYP734A7 can also convert CS and BL to their hydroxylated products, respectively (Ohnishi et al., 2006a). CYP734A orthologs from rice control endogenous bioactive levels of BRs by metabolizing both CS and its precursors (Sakamoto et al., 2011; Thornton et al., 2011). It is noteworthy that rice CYP734As can catalyze not only the hydroxylation but also the second and the third oxidations to produce aldehyde and carboxylate groups at C26 (Sakamoto et al., 2011). PAG1 from cotton and DcBAS1 from carrot may also inactivate bioactive BRs in a way similar to that of the Arabidopsis BAS1 (Yang et al., 2014; Que et al., 2019).

CYP72C1/SOB7/SHK1/CHI2, a homolog of BAS1/CYP734A1, was identified by three independent research groups in the same year. It acts redundantly with BAS1/CYP734A1 to modulate Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis and BR inactivation processes (Nakamura et al., 2005; Takahashi et al., 2005; Turk et al., 2005). However, CYP72C1 prefer to act on BR immediate precursors via an uncharacterized mechanism, which is different from CYP734A members that can inactivate both BL and CS through C26 hydroxylation (Thornton et al., 2010).

Glycosyltransferases

Glucosylation is one of the important regulatory mechanisms controlling hormone homeostasis in planta. CS and BL can be glucosylated at different positions. C2-, C3-, C22-, and C23-glucosylation of CS, and C2-, C3-, and C23-glucosylation of BL were confirmed, although the glucosylation profiles varied in different plant species (Soeno et al., 2006). 23-O-glucosylation of CS or BL was found to be predominant in Arabidopsis, which is catalyzed by two homologous UDP-glycosyltransferases named UGT73C5 and UGT73C6 (Poppenberger et al., 2005; Husar et al., 2011). Overexpression of UGT73C5 or UGT73C6 leads to a BR-deficient phenotype in Arabidopsis. Since these two functionally redundant genes are tightly linked, it is impossible to get high-order null mutant with traditional genetics to support the biochemical analysis results at the time when it was first published. Of course, using a CRISPR-Cas9 approach can solve such a problem at present time. In addition, enzymes mediating C2-, C3-, and C22- glucosylation of BRs in plants are still unknown.

BEN1, a Putative Reductase

BRI1-5 ENHANCED1 (BEN1) is also involved in BR inactivation in Arabidopsis (Yuan et al., 2007). Although the detailed biochemical mechanism has not been elucidated, strong genetic evidence supports that BEN1 functions as a BR inactivating enzyme. Gain of function of BEN1 severely enhances the bri1-5 defective phenotype, while loss of function of BEN1 leads to an organ-elongation phenotype. Since BEN1 encodes a dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR)-like protein, it is hypothesized that BEN1 functions as a reductase to convert 6-oxo BR intermediates to their 6-deoxo counterparts (Yuan et al., 2007). It is noteworthy that the intronic T-DNA insertion in the ben1-1 mutant is epigenetically regulated (Sandhu et al., 2013).

Acyltransferases

Three acyltransferases were found to decrease endogenous bioactive levels of BRs likely via different biochemical mechanisms in Arabidopsis. BRASSINOSTEROID INACTIVATOR 1 (BIA1)/ABNORMAL SHOOT1 (ABS1), a BAHD acyltransferase in Arabidopsis, was isolated by two independent research groups. Activation tagged mutants or transgenic plants overexpressing BIA1/ABS1 display reduced levels of endogenous BRs and BR-deficient phenotypes that can be rescued by exogenous application of active BRs, indicating a possible role of BIA1/ABS1 in maintaining BR homeostasis (Roh et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). A more recent study demonstrated that BIA1 uses acetyl-CoA as a donor substrate to acylate CS, leading to the formation of monoacetylated and diacetylated CS (Gan et al., 2020). BIA2, a homolog of BIA1/ABS1 in Arabidopsis, also plays a role in BR inactivation possibly via the esterification of certain BRs (Zhang and Xu, 2018). PIZZA (PIZ)/BR-RELATED ACYLTRANSFERASE1 (BAT1)/DWARF AND ROUND LEAF1 (DRL1), an acyltransferase in Arabidopsis, was found to regulate BR homeostasis probably by converting BR intermediates into acylated inactive conjugates (Schneider et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013).

Sulfotransferases

BNST3 and BNST4, two homologous steroid sulfotransferases from Brassica napus, catalyze the in vitro O-sulfonation of BRs as well as mammalian estrogenic steroids and hydroxysteroids (Rouleau et al., 1999; Marsolais et al., 2004). They are stereospecific for 24-epiBRs, with a preference for 24-epicathasterone, an intermediate in the biosynthesis of 24-epiBL, which is different from other known metabolic enzymes that utilize CS and BL as substrates. However, BNST3 and BNST4 were also thought to be involved in BR inactivation since sulfonation of 24-epiBL leads to the absence of its biological activity in the bean second internode bioassay (Rouleau et al., 1999; Marsolais et al., 2004). AtST1, an Arabidopsis ortholog of BNST3 and BNST4, displays a similar specificity toward 24-epiBRs. Whereas, AtST4a, another steroid sulfotransferase from Arabidopsis, is specific for bioactive BR compounds (Marsolais et al., 2007). Genetic evidence to support the significance of these sulfotransferases in BR inactivation is still lacking (Sandhu and Neff, 2013).

Regulation of BR Catabolism

Plants evolved various mechanisms to control BR catabolism (Figure 3). Feedback regulation of key BR catabolic genes is one of these mechanisms. It was found that BL induces the expression of several BR catabolic genes, including BIA1/ABS1, BIA2, PIZ/BAT1/DRL1, BAS1/CYP734A1, and SOB7/SHK1/CHI2 in Arabidopsis, PAG1 in cotton, and DcBAS1 in carrot (Tanaka et al., 2005; Roh et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014; Zhang and Xu, 2018; Que et al., 2019).

Besides the end products of the BR biosynthetic pathway, other phytohormones were also found to regulate the expression of the BR catabolic genes. For example, the expression of BNST3/4 can be induced by salicylic acid (Rouleau et al., 1999). The expression of PIZ/BAT1/DRL1 is induced by auxin but repressed by abscisic acid (Choi et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013). Moreover, ARF7, an auxin responsive transcription factor, can directly inhibit the expression of BAS1/CYP734A1 to increase endogenous BR contents in Arabidopsis, providing sufficient evidence that auxin regulates BR catabolism (Youn et al., 2016).

Most of the abovementioned BR catabolic genes show different expression patterns under light and in darkness, indicating an important role of light in maintaining BR homeostasis by regulating the catabolic reactions. However, little is known about the detailed mechanisms. It has been found that PHYB, a red/far red-absorbing phytochrome, modulates BAS1 expression in Arabidopsis shoot apex to inhibit phase transition (Sandhu et al., 2012). ATAF2, an Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor suppressed by light at a transcription level, modulates BR inactivation via directly binding to the promoter of BAS1/CYP734A1 and SOB7/SHK1/CHI2 to repress their expression (Peng et al., 2015). A more recent study demonstrated that CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1), a MYB transcription factor, interacts with ATAF2 and directly regulates the oscillation expression of BAS1/CYP734A1 and SOB7/SHK1/CHI2 (Peng and Neff, 2020).

Two more transcription factors were found to be involved in regulating BR catabolism. However, the upstream signaling is unknown. LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES (LOB) activates BAS1/CYP734A1 expression via directly binding to its promoter and consequently decrease BR accumulation to limit growth in Arabidopsis organ boundaries (Bell et al., 2012). OSH1, a KNOX transcription factor, promotes the expression of three homologous BR catabolic genes, CYP734A2, CYP734A4, and CYP734A6, to control local bioactive BR levels in rice shoot apical meristems (Tsuda et al., 2014).

General Conclusion

It has been about fifty years since BL was first discovered from Brassica napus pollen grains (Mitchell et al., 1970). Significant progress has been made in our understanding of BR biosynthesis and catabolism. Although the BR biosynthesis pathway displays a metabolic grid, the most dominant and efficient shortcut was established, with only eight and seven steps in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively (Figure 2). Moreover, enzymes catalyzing each reaction in the BR biosynthetic pathway, except for the C2 hydroxylation and the C3 redox reaction, have been identified by using analytical chemistry and molecular genetic approaches. Structural and physiological studies revealed that C2 and C3 positions are important for BR activity and perception by its receptor and coreceptor (Hothorn et al., 2011; She et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2013). Therefore, identification of C2 hydroxylase and C3 oxidase/reductase is essential for clarifying the whole picture of BR biosynthesis. CYP92A6/DDWF1 from pea was identified as the C2 hydroxylase, providing reference for study of C2 hydroxylase in Arabidopsis, rice, and other higher plants (Kang et al., 2001). As revealed by feeding experiments or anticipated from naturally occurring metabolites, various BR metabolic reactions were found (Fujioka and Yokota, 2003). However, little is known about the corresponding enzymes and the underlying mechanisms. Moreover, knowledge about how BR biosynthesis and catabolism are regulated, especially in a specific organ or tissue, by diverse internal and external cues is still very limited. Elucidating the mechanisms regulating BR homeostasis can help us to generate high-yield transgenic crops via manipulating bioactive BR contents. For example, modulating the expression of C22 hydroxylase, catalyzing the rate-limiting step in BR biosynthesis pathway, in different plant species indeed resulted in increased vegetative growth, yield, and tolerance (Choe et al., 2001; Sakamoto et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2010; Sakaguchi and Watanabe, 2017; Li et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018). It might not be possible to obtain optimal BR effects for all of the agronomic traits, since BRs control many aspects of plant growth and development, and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. However, even if a subset of these traits can be improved by BRs, the accomplishment will be significant.

Author Contributions

ZW prepared the manuscript. JL revised the manuscript.

Funding

We are grateful for the support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31720103902, 31530005, 31700245), the 111 Project (grant no. B16022), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. lzujbky-2020-32 from Lanzhou University).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- An J., Guo Z., Gou X., Li J. (2011). TCP1 positively regulates the expression of DWF4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav. 6 (8), 1117–1118. 10.4161/psb.6.8.15889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina M., Tamaki Y., Sakamoto T., Shibata K., Nomura T., Yokota T. (2014). Blue light-promoted rice leaf bending and unrolling are due to up-regulated brassinosteroid biosynthesis genes accompanied by accumulation of castasterone. Phytochemistry 104, 21–29. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiychuk E., Bouvier-Nave P., Compagnon V., Suzuki M., Muranaka T., Van Montagu M., et al. (2008). Allelic mutant series reveal distinct functions for Arabidopsis cycloartenol synthase 1 in cell viability and plastid biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (8), 3163–3168. 10.1073/pnas.0712190105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajguz A., Tretyn A. (2003). The chemical characteristic and distribution of brassinosteroids in plants. Phytochemistry 62 (7), 1027–1046. 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00656-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak S., Kahn R. A., Olsen C. E., Halkier B. A. (1997). Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase of Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench, a cytochrome P450 orthologous to the sterol 14α-demethylases (CYP51) from fungi and mammals. Plant J. 11 (2), 191–201. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11020191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancos S., Szatmari A. M., Castle J., Kozma-Bognar L., Shibata K., Yokota T., et al. (2006). Diurnal regulation of the brassinosteroid-biosynthetic CPD gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 141 (1), 299–309. 10.1104/pp.106.079145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E. M., Lin W. C., Husbands A. Y., Yu L. F., Jaganatha V., Jablonska B., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES negatively regulates brassinosteroid accumulation to limit growth in organ boundaries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (51), 21146–21151. 10.1073/pnas.1210789109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best N. B., Hartwig T., Budka J., Fujioka S., Johal G., Schulz B., et al. (2016). NANA PLANT2 encodes a maize ortholog of the Arabidopsis brassinosteroid biosynthesis gene DWARF1, identifying developmental interactions between brassinosteroids and gibberellins. Plant Physiol. 171 (4), 2633–2647. 10.1104/pp.16.00399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop G. J., Yokota T. (2001). Plants steroid hormones, brassinosteroids: current highlights of molecular aspects on their synthesis/metabolism, transport, perception and response. Plant Cell Physiol. 42 (2), 114–120. 10.1093/Pcp/Pce018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop G. J., Nomura T., Yokota T., Harrison K., Noguchi T., Fujioka S., et al. (1999). The tomato DWARF enzyme catalyses C-6 oxidation in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (4), 1761–1766. 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier-Navé P., Husselstein T., Desprez T., Benveniste P. (1997). Identification of cDNAs encoding sterol methyl-transferases involved in the second methylation step of plant sterol biosynthesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 246 (2), 518–529. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C., Rondet S., Benveniste P., Schaller H. (2003). Virus-induced silencing of sterol biosynthetic genes: identification of a Nicotiana tabacum L. obtusifoliol-14α-demethylase (CYP51) by genetic manipulation of the sterol biosynthetic pathway in Nicotiana benthamiana L. J. Exp. Bot. 54 (388), 1675–1683. 10.1093/jxb/erg184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello-Hurtado F., Taton M., Forthoffer N., Kahn R., Bak S., Rahier A., et al. (1999). Optimized expression and catalytic properties of a wheat obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) expressed in yeast - Complementation of erg11Δ yeast mutants by plant CYP51. Eur. J. Biochem. 262 (2), 435–446. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carland F. M., Berg B. L., FitzGerald J. N., Jinamornphongs S., Nelson T., Keith B. (1999). Genetic regulation of vascular tissue patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11 (11), 2123–2137. 10.1105/tpc.11.11.2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carland F. M., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., Nelson T. (2002). The identification of CVP1 reveals a role for sterols in vascular patterning. Plant Cell 14 (9), 2045–2058. 10.1105/tpc.003939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carland F., Fujioka S., Nelson T. (2010). The sterol methyltransferases SMT1, SMT2, and SMT3 influence Arabidopsis development through nonbrassinosteroid products. Plant Physiol. 153 (2), 741–756. 10.1104/pp.109.152587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterou M., Dubois F., Schaller H., Aubanelle L., Vilcot B., Sangwan-Norreel B. S., et al. (2001. a). Brassinosteroids, microtubules and cell elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. I. Molecular, cellular and physiological characterization of the Arabidopsis bul1 mutant, defective in the Δ7-sterol-C5-desaturation step leading to brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Planta 212 (5-6), 659–672. 10.1007/s004250000466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterou M., Dubois F., Schaller H., Aubanelle L., Vilcot B., Sangwan-Norreel B. S., et al. (2001. b). Brassinosteroids, microtubules and cell elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. II. Effects of brassinosteroids on microtubules and cell elongation in the bul1 mutant. Planta 212 (5-6), 673–683. 10.1007/s004250000467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S. W., Dilkes B. P., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Sakurai A., Feldmann K. A. (1998). The DWF4 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a cytochrome P450 that mediates multiple 22α-hydroxylation steps in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 10 (2), 231–243. 10.1105/Tpc.10.2.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S., Dilkes B. P., Gregory B. D., Ross A. S., Yuan H., Noguchi T., et al. (1999. a). The Arabidopsis dwarf1 mutant is defective in the conversion of 24-methylenecholesterol to campesterol in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 119 (3), 897–907. 10.1104/Pp.119.3.897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S. W., Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Tissier C. P., Gregory B. D., et al. (1999. b). The Arabidopsis dwf7/ste1 mutant is defective in the Δ7 sterol C-5 desaturation step leading to brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 11 (2), 207–221. 10.1105/Tpc.11.2.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S., Tanaka A., Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Ross A. S., et al. (2000). Lesions in the sterol Δ7 reductase gene of Arabidopsis cause dwarfism due to a block in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant J. 21 (5), 431–443. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00693.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S., Fujioka S., Noguchi T., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., Feldmann K. A. (2001). Overexpression of DWARF4 in the brassinosteroid biosynthetic pathway results in increased vegetative growth and seed yield in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 26 (6), 573–582. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S., Cho Y. H., Kim K., Matsui M., Son S. H., Kim S. K., et al. (2013). BAT1, a putative acyltransferase, modulates brassinosteroid levels in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 73 (3), 380–391. 10.1111/tpj.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chory J., Nagpal P., Peto C. A. (1991). Phenotypic and genetic-analysis of det2, a new mutant that affects light-regulated seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 3 (5), 445–459. 10.1105/tpc.3.5.445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y., Maharjan P. M., Lee O., Fujioka S., Jang S., Kim B., et al. (2011). Auxin stimulates DWARF4 expression and brassinosteroid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 66 (4), 564–578. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04513.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse S. D., Sasse J. M. (1998). Brassinosteroids: essential regulators of plant growth and development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 427–451. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse S. D., Langford M., McMorris T. C. (1996). A brassinosteroid-insensitive mutant in Arabidopsis thaliana exhibits multiple defects in growth and development. Plant Physiol. 111 (3), 671–678. 10.1104/Pp.111.3.671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J., Matsuda S. P. T., Bartel B. (1993). Isolation of an Arabidopsis thaliana gene encoding cycloartenol synthase by functional expression in a yeast mutant lacking lanosterol synthase by the use of a chromatographic screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (24), 11628–11632. 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnet S., Rahier A. (2004). Plant sterol biosynthesis: identification of two distinct families of sterol 4α-methyl oxidases. Biochem. J. 378, 889–898. 10.1042/Bj20031572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnet S., Bard M., Rahier A. (2001). Functional identification of sterol-4α-methyl oxidase cDNAs from Arabidopsis thaliana by complementation of a yeast erg25 mutant lacking sterol-4α-methyl oxidation. FEBS Lett. 508 (1), 39–43. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haro L. A., Arellano S. M., Novak O., Feil R., Dumon A. D., Mattio M. F., et al. (2019). Mal de Río Cuarto virus infection causes hormone imbalance and sugar accumulation in wheat leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 19 (1), 112. 10.1186/s12870-019-1709-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener A. C., Li H. X., Zhou W. X., Whoriskey W. J., Nes W. D., Fink G. R. (2000). STEROL METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 controls the level of cholesterol in plants. Plant Cell 12 (6), 853–870. 10.1105/Tpc.12.6.853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockter C., Gruszka D., Braumann I., Druka A., Druka I., Franckowiak J., et al. (2014). Induced variations in brassinosteroid genes define barley height and sturdiness, and expand the green revolution genetic toolkit. Plant Physiol. 166 (4), 1912–1927. 10.1104/pp.114.250738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L. Q., Poovaiah B. W. (2005). Ca2+/calmodulin is critical for brassinosteroid biosynthesis and plant growth. Nature 437 (7059), 741–745. 10.1038/nature03973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z. M., Wu C. Y., Wang C. M., Roh J., Zhang L., Chen J., et al. (2016). SLG controls grain size and leaf angle by modulating brassinosteroid homeostasis in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 67 (14), 4241–4253. 10.1093/jxb/erw204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka S., Yokota T. (2003). Biosynthesis and metabolism of brassinosteroids. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54, 137–164. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka S., Li J. M., Choi Y. H., Seto H., Takatsuto S., Noguchi T., et al. (1997). The Arabidopsis deetiolated2 mutant is blocked early in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 9 (11), 1951–1962. 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S. (2002). An early C-22 oxidation branch in the brassinosteroid biosynthetic pathway. Plant Physiol. 130 (2), 930–939. 10.1104/pp.008722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S., Ohnishi T., Watanabe B., Yokota T., Takatsuto S., Fujioka S., et al. (2006). Arabidopsis CYP90B1 catalyses the early C-22 hydroxylation of C27, C28 and C29 sterols. Plant J. 45 (5), 765–774. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachotte D., Meens R., Benveniste P. (1995). An Arabidopsis mutant deficient in sterol biosynthesis - heterologous complementation by ERG3 encoding a Δ7-sterol-C-5-desaturase from yeast. Plant J. 8 (3), 407–416. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08030407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L. J., Wu H., Wu D. P., Zhang Z. F., Guo Z. F., Yang N., et al. (2015). Methyl jasmonate inhibits lamina joint inclination by repressing brassinosteroid biosynthesis and signaling in rice. Plant Sci. 241, 238–245. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan S., Rozhon W., Varga E., Unterholzner S. J., Berthiller F., Poppenberger B. (2020). The BAHD acyltransferase BIA1 uses acetyl-CoA for catabolic inactivation of brassinosteroids. Plant Physiol. 184 (1), 23–26. 10.1104/pp.20.00338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. H., Zhang D. Z., Li J. (2015). TCP1 modulates DWF4 expression via directly interacting with the GGNCCC motifs in the promoter region of DWF4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Genet. Genomics 42 (7), 383–392. 10.1016/j.jgg.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gas-Pascual E., Berna A., Bach T. J., Schaller H. (2014). Plant oxidosqualene metabolism: cycloartenol synthase-dependent sterol biosynthesis in Nicotiana benthamiana. PloS One 9 (10), e109156. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove M. D., Spencer G. E., Rohwedder W. K., Mandava N., Worley J. F., Warthen J. D., et al. (1979). Brassinolide, a plant growth-promoting steroid isolated from Brassica napus pollen. Nature 281, 216–217. 10.1038/281216a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan H. Y., Zhao Y. J., Su P., Tong Y. R., Liu Y. J., Hu T. Y., et al. (2017). Molecular cloning and functional identification of sterol C24-methyltransferase gene from Tripterygium wilfordii. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 7 (5), 603–609. 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z. X., Fujioka S., Blancaflor E. B., Miao S., Gou X. P., Li J. (2010). TCP1 modulates brassinosteroid biosynthesis by regulating the expression of the key biosynthetic gene DWARF4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22 (4), 1161–1173. 10.1105/tpc.109.069203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. X., Gendron J. M., Sun Y., Gampala S. S. L., Gendron N., Sun C. Q., et al. (2005). BZR1 is a transcriptional repressor with dual roles in brassinosteroid homeostasis and growth responses. Science 307 (5715), 1634–1638. 10.1126/science.1107580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg N., Harker M., Gibbard C. L., Wallace A. D., Clayton J. C., Rawlins S., et al. (2002). Sterol C-24 methyltransferase type 1 controls the flux of carbon into sterol biosynthesis in tobacco seed. Plant Physiol. 130 (1), 303–311. 10.1104/pp.004226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Shimizu-Sato S., Inukai Y., Fujioka S., Shimada Y., et al. (2002). Loss-of-function of a rice brassinosteroid biosynthetic enzyme, C-6 oxidase, prevents the organized arrangement and polar elongation of cells in the leaves and stem. Plant J. 32 (4), 495–508. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Umemura K., Uozu S., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., et al. (2003). A rice brassinosteroid-deficient mutant, ebisu dwarf (d2), is caused by a loss of function of a new member of cytochrome P450. Plant Cell 15 (12), 2900–2910. 10.1105/tpc.014712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., Hasegawa Y., et al. (2005). The rice brassinosteroid-deficient dwarf2 mutant, defective in the rice homolog of Arabidopsis DIMINUTO/DWARF1, is rescued by the endogenously accumulated alternative bioactive brassinosteroid, dolichosterone. Plant Cell 17 (8), 2243–2254. 10.1105/tpc.105.030973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn M., Belkhadir Y., Dreux M., Dabi T., Noel J. P., Wilson I. A., et al. (2011). Structural basis of steroid hormone perception by the receptor kinase BRI1. Nature 474 (7352), 467–U490. 10.1038/nature10153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S. S., Niu H. H., Tao Q. Y., Wang S. H., Gong Z. H., Li S., et al. (2017). A mutant in the CsDET2 gene leads to a systemic brassinosteriod deficiency and super compact phenotype in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 130 (8), 1693–1703. 10.1007/s00122-017-2919-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo W. G., Li B. D., Kuang J. B., He P. A., Xu Z. H., Wang J. X. (2018). Functional characterization of the steroid reductase genes GmDET2a and GmDET2b from Glycine max. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (3), 726. 10.3390/ijms19030726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husar S., Berthiller F., Fujioka S., Rozhon W., Khan M., Kalaivanan F., et al. (2011). Overexpression of the UGT73C6 alters brassinosteroid glucoside formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 51. 10.1186/1471-2229-11-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husselstein T., Gachotte D., Desprez T., Bard M., Benveniste P. (1996). Transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a cDNA encoding a sterol C-methyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana results in the synthesis of 24-ethyl sterols. FEBS Lett. 381 (1-2), 87–92. 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00089-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang O. J., Back K. (2018). Melatonin is involved in skotomorphogenesis by regulating brassinosteroid biosynthesis in rice plants. J. Pineal Res. 65 (2), e12495. 10.1111/jpi.12495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang O. J., Back K. (2019). Melatonin deficiency confers tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in rice via decreased brassinosteroid levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (20), 5173. 10.3390/ijms20205173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Il Je B., Piao H. L., Park S. J., Park S. H., Kim C. M., Xuan Y. H., et al. (2010). RAV-Like1 maintains brassinosteroid homeostasis via the coordinated activation of BRI1 and biosynthetic genes in rice. Plant Cell 22 (6), 1777–1791. 10.1105/tpc.109.069575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager C. E., Symons G. M., Nomura T., Yamada Y., Smith J. J., Yamaguchi S., et al. (2007). Characterization of two brassinosteroid C-6 oxidase genes in pea. Plant Physiol. 143 (4), 1894–1904. 10.1104/pp.106.093088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamshed M., Liang S. Y., Nickerson N. M. N., Samuel M. A. (2017). Farnesylation-mediated subcellular localization is required for CYP85A2 function. Plant Signal Behav. 12 (10), e1382795. 10.1080/15592324.2017.1382795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J. C., Fujioka S., Tasaka M., Seto H., Takatsuto S., Ishii A., et al. (2000). A critical role of sterols in embryonic patterning and meristem programming revealed by the fackel mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 14 (12), 1485–1497. 10.1101/gad.14.12.1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D. F., Gong X. Q., Li M. J., Li C., Sun T. T., Ma F. W. (2018). Overexpression of a novel apple NAC transcription factor gene, MdNAC1, confers the dwarf phenotype in transgenic apple (Malus domestica). Genes 9 (5), 229. 10.3390/genes9050229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. H., Bao L., Jeong S. Y., Kim S. K., Xu C. G., Li X. H., et al. (2012). XIAO is involved in the control of organ size by contributing to the regulation of signaling and homeostasis of brassinosteroids and cell cycling in rice. Plant J. 70 (3), 398–408. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04877.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X. M., Wang H. C., Yan J. J., Kong X. Y., Liu Y. W., Chu J. F., et al. (2020). Promotion of br biosynthesis by miR444 is required for ammonium-triggered inhibition of root growth. Plant Physiol. 182 (3), 1454–1466. 10.1104/pp.19.00190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Gongora T., Kim S. K., Lozano-Duran R., Zipfel C. (2015). Flg22-triggered immunity negatively regulates key br biosynthetic genes. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 981. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y. L., Tang R. J., Wang H. H., Jiang C. M., Bao Y., Yang Y., et al. (2017). Overexpression of Populus trichocarpa CYP85A3 promotes growth and biomass production in transgenic trees. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15 (10), 1309–1321. 10.1111/pbi.12717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. A., Bak S., Olsen C. E., Svendsen I., Moller B. L. (1996). Isolation and reconstitution of the heme-thiolate protein obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase from Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. J. Biol. Chem. 271 (51), 32944–32950. 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. G., Yun J., Kim D. H., Chung K. S., Fujioka S., Kim J. I., et al. (2001). Light and brassinosteroid signals are integrated via a dark-induced small G protein in etiolated seedling growth. Cell 105 (5), 625–636. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00370-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauschmann A., Jessop A., Koncz C., Szekeres M., Willmitzer L., Altmann T. (1996). Genetic evidence for an essential role of brassinosteroids in plant development. Plant J. 9 (5), 701–713. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.9050701.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. B., Schaller H., Goh C. H., Kwon M., Choe S., An C. S., et al. (2005. a). Arabidopsis cyp51 mutant shows postembryonic seedling lethality associated with lack of membrane integrity. Plant Physiol. 138 (4), 2033–2047. 10.1104/pp.105.061598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. W., Hwang J. Y., Kim Y. S., Joo S. H., Chang S. C., Lee J. S., et al. (2005. b). Arabidopsis CYP85A2, a cytochrome P450, mediates the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of castasterone to brassinolide in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 17 (8), 2397–2412. 10.1105/tpc.105.033738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. B., Kwon M., Ryu H., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., et al. (2006). The regulation of DWARF4 expression is likely a critical mechanism in maintaining the homeostasis of bioactive brassinosteroids in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 140 (2), 548–557. 10.1104/pp.105.067918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. K., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Tsujimoto M., Choe S. (2008). Castasterone is a likely end product of brassinosteroid biosynthetic pathway in rice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 374 (4), 614–619. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahre U., Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Yokota T., Nomura T., et al. (1998). The Arabidopsis DIMINUTO/DWARF1 gene encodes a protein involved in steroid synthesis. Plant Cell 10 (10), 1677–1690. 10.1105/tpc.10.10.1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koka C. V., Cerny R. E., Gardner R. G., Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., et al. (2000). A putative role for the tomato genes DUMPY and CURL-3 in brassinosteroid biosynthesis and response. Plant Physiol. 122 (1), 85–98. 10.1104/Pp.122.1.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushiro M., Nakano T., Sato K., Yamagishi K., Asami T., Nakano A., et al. (2001). Obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) antisense Arabidopsis shows slow growth and long life. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 285 (1), 98–104. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Back K. (2019). Melatonin-deficient rice plants show a common semidwarf phenotype either dependent or independent of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. J. Pineal Res. 66 (2), e12537. 10.1111/jpi.12537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. M., Chory J. (1997). A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell 90 (5), 929–938. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80357-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. M., Nagpal P., Vitart V., McMorris T. C., Chory J. (1996). A role for brassinosteroids in light-dependent development of Arabidopsis. Science 272 (5260), 398–401. 10.1126/science.272.5260.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. M., Biswas M. G., Chao A., Russell D. W., Chory J. (1997). Conservation of function between mammalian and plant steroid 5α-reductases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (8), 3554–3559. 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wen J. Q., Lease K. A., Doke J. T., Tax F. E., Walker J. C. (2002). BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110 (2), 213–222. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00812-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Jiang L., Youn J. H., Sun W., Cheng Z. J., Jin T. Y., et al. (2013). A comprehensive genetic study reveals a crucial role of CYP90D2/D2 in regulating plant architecture in rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 200 (4), 1076–1088. 10.1111/nph.12427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. F., Yu J. W., Lu J., Fei H. Y., Luo M., Cao B. W., et al. (2018). Seed-specific expression of OsDWF4, a rate-limiting gene involved in brassinosteroids biosynthesis, improves both grain yield and quality in rice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66 (15), 3759–3772. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. F., Lu J., Zhou Y., Wu F., Tong H. N., Wang J. D., et al. (2019). Abscisic acid represses rice lamina joint inclination by antagonizing brassinosteroid biosynthesis and signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (19), 4908. 10.3390/ijms20194908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. S., Zhang J. P., Wang M. Y., Wang Z. Y., Li G. F., Qu L., et al. (2007). Expression and functional analysis of ZmDWF4, an ortholog of Arabidopsis DWF4 from maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Cell Rep. 26 (12), 2091–2099. 10.1007/s00299-007-0418-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Feng Z. M., Zhou C. L., Ren Y. K., Mou C. L., Wu T., et al. (2016). Brassinosteroid (BR) biosynthetic gene lhdd10 controls late heading and plant height in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Rep. 35 (2), 357–368. 10.1007/s00299-015-1889-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. Y., Cao J., Yu K. H., Liu X. Y., Gao Y. J., Chen Q., et al. (2019). Wheat TaSPL8 modulates leaf angle through auxin and brassinosteroid signaling. Plant Physiol. 181 (1), 179–194. 10.1104/pp.19.00248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhou J. W., Hu T. Y., Lu Y., Gao L. H., Tu L. C., et al. (2020. a). Identification and functional characterization of squalene epoxidases and oxidosqualene cyclases from Tripterygium wilfordii. Plant Cell Rep. 39 (3), 409–418. 10.1007/s00299-019-02499-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. H., Chen Y., Wang N. N., Chen Y. H., Wei N., Lu R., et al. (2020. b). A basic helix-loop-helix protein (GhFP1) promotes fibre elongation of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) by modulating brassinosteroid biosynthesis and signalling. New Phytol. 225 (6), 2439–2452. 10.1111/nph.16301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato M. A., Hart E. A., Segura M. J. R., Giner J. L., Matsuda S. P. T. (2000). Functional cloning of an Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA encoding cycloeucalenol cycloisomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (18), 13394–13397. 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Xiao Y. H., Li X. B., Lu X. F., Deng W., Li D., et al. (2007). GhDET2, a steroid 5 alpha-reductase, plays an important role in cotton fiber cell initiation and elongation. Plant J. 51 (3), 419–430. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03144.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Tan K. L., Xiao Z. Y., Hu M. Y., Liao P., Chen K. J. (2008). Cloning and expression of two sterol C-24 methyltransferase genes from upland cotton (Gossypium hirsuturm L.). J. Genet. Genomics 35 (6), 357–363. 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60052-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharjan P. M., Choe S. (2011). High temperature stimulates DWARF4 (DWF4) expression to increase hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. J. Plant Biol. 54 (6), 425–429. 10.1007/s12374-011-9183-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Makarevitch I., Thompson A., Muehlbauer G. J., Springer N. M. (2012). Brd1 gene in maize encodes a brassinosteroid c-6 oxidase. PloS One 7 (1), e30798. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsolais F., Sebastia C. H., Rousseau A., Varin L. (2004). Molecular and biochemical characterization of BNST4, an ethanol-inducible steroid sulfotransferase from Brassica napus, and regulation of BNST genes by chemical stress and during development. Plant Sci. 166 (5), 1359–1370. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.01.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsolais F., Boyd J., Paredes Y., Schinas A. M., Garcia M., Elzein S., et al. (2007). Molecular and biochemical characterization of two brassinosteroid sulfotransferases from Arabidopsis, AtST4a (At2g14920) and AtST1 (At2g03760). Planta 225 (5), 1233–1244. 10.1007/s00425-006-0413-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C., Espinosa-Ruiz A., de Lucas M., Bernardo-Garcia S., Franco-Zorrilla J. M., Prat S. (2018). PIF4-induced BR synthesis is critical to diurnal and thermomorphogenic growth. EMBO J. 37 (23), e99552. 10.15252/embj.201899552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur J., Molnar G., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Sakurai A., Yokota T., et al. (1998). Transcription of the Arabidopsis CPD gene, encoding a steroidogenic cytochrome P450, is negatively controlled by brassinosteroids. Plant J. 14 (5), 593–602. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Men S. Z., Boutte Y., Ikeda Y., Li X. G., Palme K., Stierhof Y. D., et al. (2008). Sterol-dependent endocytosis mediates post-cytokinetic acquisition of PIN2 auxin efflux carrier polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 10 (2), 237–U124. 10.1038/ncb1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. W., Mandava N., Worley J. F., Plimmer J. R., Smith M. V. (1970). Brassins–a new family of plant hormones from rape pollen. Nature 225 (5237), 1065–1066. 10.1038/2251065a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M., Nomura T., Ooka H., Ishizaka M., Yokota T., Sugimoto K., et al. (2002). Isolation and characterization of a rice dwarf mutant with a defect in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 130 (3), 1152–1161. 10.1104/pp.007179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchel C. F., Osmont K. S., Hardtke C. S. (2006). BRX mediates feedback between brassinosteroid levels and auxin signalling in root growth. Nature 443 (7110), 458–461. 10.1038/nature05130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M., Satoh T., Tanaka S. I., Mochizuki N., Yokota T., Nagatani A. (2005). Activation of the cytochrome P450 gene, CYP72C1, reduces the levels of active brassinosteroids in vivo. J. Exp. Bot. 56 (413), 833–840. 10.1093/jxb/eri073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff M. M., Nguyen S. M., Malancharuvil E. J., Fujioka S., Noguchi T., Seto H., et al. (1999). BAS1: A gene regulating brassinosteroid levels and light responsiveness in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (26), 15316–15323. 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Sakurai A., Yoshida S., Li J. M., et al. (1999). Arabidopsis det2 is defective in the conversion of (24R)-24-methylcholest-4-en-3-one to (24R)-24-methyl-5α-cholestan-3-one in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 120 (3), 833–839. 10.1104/Pp.120.3.833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura T., Sato T., Bishop G. J., Kamiya Y., Takatsuto S., Yokota T. (2001). Accumulation of 6-deoxocathasterone and 6-deoxocastasterone in Arabidopsis, pea and tomato is suggestive of common rate-limiting steps in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 57 (2), 171–178. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00440-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura T., Jager C. E., Kitasaka Y., Takeuchi K., Fukami M., Yoneyama K., et al. (2004). Brassinosteroid deficiency due to truncated steroid 5α-reductase causes dwarfism in the lk mutant of pea. Plant Physiol. 135 (4), 2220–2229. 10.1104/pp.104.043786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]