Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to confirm the accuracy of a machine-learning-based model in predicting the 30-day mortality of patients with pneumonia and evaluating whether they were required to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Methods

The study conducted a retrospective analysis of pneumonia patients at an emergency department (ED) in Seoul, Korea, from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2017. Patients aged 18 years or older with a pneumonia registry designation on their electronic medical record were enrolled. We collected their demographic information, mental status, and laboratory findings. Three models were used: the pre-existing CURB-65 model, and the CURB-RF and Extensive CURB-RF models, which were machine-learning models that used a random forest algorithm. The primary outcomes were ICU admission from the ED or 30-day mortality. Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed for the models, and the areas under these curves were compared.

Results

Out of the 1,974 pneumonia patients, 1,732 patients were eligible to be included in the study; from these, 473 patients died within 30 days or were initially admitted to the ICU from the ED. The area under receiver operating characteristic curves of CURB-65, CURB-RF, and extensive-CURB-RF were 0.615 (0.614–0.616), 0.701 (0.700–0.702), and 0.844 (0.843–0.845), respectively.

Conclusion

The proposed machine-learning models could predict the mortality of patients with pneumonia more accurately than the pre-existing CURB-65 model and can help decide whether the patient should be admitted to the ICU.

Keywords: Pneumonia; Machine-learning; Mortality; Emergency service, hospital

INTRODUCTION

Pneumonia remains the number one cause of death from infectious diseases worldwide [1]. As many as four million cases of pneumonia are reported annually, and nearly one-fifth of these cases require hospitalization [2]. In the outpatient setting, the mortality rate of pneumonia remains low, within the range of 1% to 5%; however, among patients with pneumonia who require hospitalization, the mortality rate approaches 25%, particularly if the patient requires admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) [3-9].

Patients suffering from fever, dyspnea, and upper/lower respiratory symptoms (e.g., coughing) often visit the emergency department (ED). Emergency physicians play an important role in the initial evaluation, assessment, management, and disposition of these patients. The CURB-65 score and the pneumonia severity index (PSI) score are the most commonly used predictive models for the classification of such patients.

However, many predictive models for pneumonia have different variables with a dichotomous and artificial cut-off [10-12]; thus, they have limited predictive powers. CURB-65 takes considerably less time for calculations and it is also more convenient to use in an ED setting than the PSI; however, it has a disadvantage in that it consists of only five variables.

Machine-learning methods have received significant attention in the medical fields, especially in diagnosis, radiology, pathology, and prediction [13-16]. Although studies on the usefulness of machine-learning models for pneumonia diagnosis have been conducted recently, their results have been insufficient [17-20]. There have been few studies directly comparing a machine-learning model to CURB-65 [18,20]. This study aimed to confirm the accuracy of a machine-learning-based model to predict the 30-day mortality of pneumonia patients as compared to CURB-65 and to determine whether pneumonia patients were required to be admitted to the ICU.

METHODS

Study setting

This study is based on a retrospective analysis of adult medical patients with a pneumonia registry designation in their electronic medical record (EMR) arriving at an ED of a tertiary referral center, which was established in 1994, in Seoul, Korea. This center has a 73-bed emergency unit with approximately 70,000 patients visits each year. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the study site (IRB number 2018-09-047-002).

Pneumonia registry

The pneumonia registry is an EMR designation documented by physicians in the ED of the tertiary referral center, since 2011. It includes information on the CURB-65 score, the pneumonia type, smoking status, and streptococcus pneumoniae vaccination preference. Patients were diagnosed with pneumonia if they exhibited acute lower respiratory symptoms accompanied by newly documented infiltrations on chest radiographs at the time of their ED visit [21]. Clinical diagnoses were made by a physician.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients aged 18 years or order with a pneumonia registry in their EMR were enrolled in the study from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2017. Exclusion criteria included a duplicated date, patients whose consent regarding the use of their EMR could not be obtained, and patients referred from or to another hospital.

Data collection

The EMRs of all the enrolled patients were reviewed by three physicians. The following data were collected: demographic information (age, sex, and past medical history, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, chronic liver disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accidents, chronic kidney disease, and cancer history), mental status at the ED, laboratory findings (Appendix 1), radiological findings such as the presence of pleural effusion, microbiological results, and in-hospital treatment data (ICU admission from the ED and 30-day mortality).

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were ICU admission from the ED or 30-day mortality, which was defined as documented death from any cause within 30 days of visiting the ED. Patients who were discharged after 30 days of their visit were considered to be alive. The case group included death within 30 days or admission to the ICU from the ED. The control group was composed of the other patients.

Data analysis

Preprocessing

By choosing a random under-sampled selection of the control group, we solved the problem of an imbalanced outcome variable. The ratio of the under-sampled selection was 1:2 between the case and control groups. To solve the problem of missing data, a multiple imputation method was used [22].

Developing prediction models

In this study, three models were established and compared. The first is a pre-existing model, CURB-65, consisting of five clinical and laboratory characteristics (confusion, blood urea nitrogen >7 mmol/L, respiratory rate >30 breaths/minute, diastolic blood pressure <60 mmHg or systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, age ≥65 years old) [23].

The second is a CURB-RF model consisting of the same variables as CURB-65 but with continuous and non-dichotomous values. Here, the term “RF” indicates the use of the random forest method. The final model is an extensive-CURB-RF (E-CURB-RF) model; this model not only contains more variables than CURB-65, but also contains continuous values, which are obtained by applying the random forest method. Appendix 1 shows the variables used to compose these models.

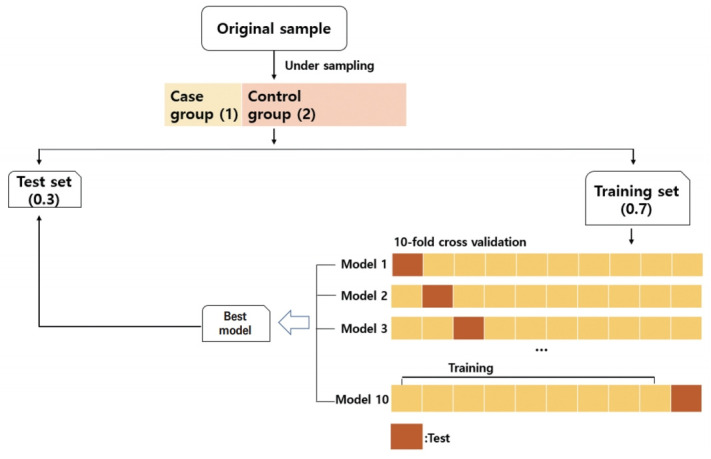

We used the basic random forest model and attempted to perform auto parameter searching by ten-fold cross validation. The dataset was divided into two smaller sets, 0.7 for the training set and 0.3 for the test set; the training set underwent ten-fold cross validation. In particular, the number of trees was fixed at 500 and the number of randomly selected features used to conduct evaluations at each tree node was searched from 1 to 15. The optimal tree node finally obtained through the ten-fold cross validation was 2. The random forest and caret package was used for modeling. The CURB-RF and E-CURB-RF models were developed based on this process (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic showing how the data were processed in this study. By choosing a random under-sampled selection of the control group at a 1:2 ratio, the presence of an imbalanced outcome variable was solved. The dataset was divided into two sets—0.7 for the training set and 0.3 for the test set. The training set went through ten-fold cross-validation. After learning the data of the training set using a random forest algorithm, the best model derived was evaluated in the test set. This process was repeated 1,000 times.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range. Categorical data were presented as absolute numbers and percent frequencies. Differences between the continuous variables were analyzed using a Wilcoxon test and differences between the categorical variables were analyzed using a chi-square test.

After learning from the data of the training set through the random forest algorithm, the prediction rates of the primary outcomes were measured for the test set for each developed model. Because there is a fundamental weakness of randomness due to the process of dividing data into training and test sets, the random forest models were created 1,000 times to compensate for the weakness. Further, each of the area under receiver operating characteristic curves (AUROCs) for CURB-65, CURB-RF, and E-CURB-RF were constructed and compared using the KruskalWallis test. In addition, we calculated the sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values, negative predictive values, accuracies, and F1 scores to compare performance of the three models. All analyses were conducted using the software package R ver. 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

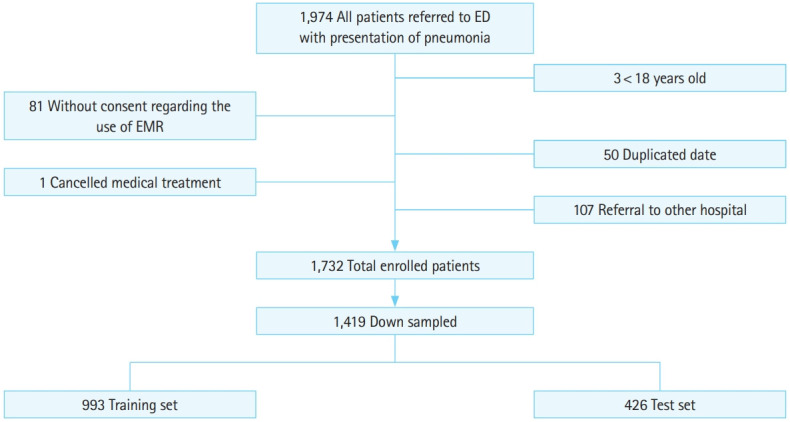

Of the 1,974 pneumonia patients originally considered for the study, 1,732 patients were eligible for inclusion and were analyzed. We excluded patients younger than 18 years old (n=3), patients without consent regarding the use of their EMR (n=81), patients with duplicated data that were mistakenly included in the original data (n=50), patients who cancelled ED care (n=1), and patients referred from or to other hospitals (n=107) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient selection process and the number of patients distributed in each group. The case group comprising death within 30 days or intensive care unit admission from the emergency department (ED) involved 473 patients. Through under-sampled selection, three times as many patients were selected. EMR, electronic medical record.

Patient characteristics

Primary information regarding the study subjects are presented in Table 1. Among the 1,732 patients considered, the total number in the case group was 473. Among them, 358 subjects died within 30 days and 178 were transferred to an ICU from the ED (Appendix 2). Among all the study patients, a total of 1,087 (62.7%) people had community-acquired pneumonia, 89 (5.0%) had hospital-acquired pneumonia, and 546 (31.5%) had healthcare-associated pneumonia. There were significant differences in the distributions of these types of pneumonia between the groups (P<0.001). In total, 695 (40.1%) patients had some type of cancer, and the case group had a significantly higher history of cancer (P<0.05), with exception of lymphoma.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study subjects

| Characteristics | Control group (n = 1,259) | Case group (death or ICU admission) (n = 473) | Total (n = 1,732) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 745 (59.2) | 344 (72.7) | 1,089 (62.9) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 67 (57–77) | 69 (61–77) | 68 (58–77) | 0.010 |

| BMI | 22.6 (19.9–25) | 21.2 (18.5–24.1) | 22.1 (19.5–24.7) | < 0.001 |

| Nursing home resident | 39 (3.1) | 24 (5.1) | 63 (3.6) | 0.070 |

| Pneumonia type | < 0.001 | |||

| CAP | 896 (71.7) | 191 (40.6) | 1,087 (62.7) | |

| HAP | 51 (4.1) | 36 (7.6) | 87 (5.0) | |

| HCAP | 302 (24.2) | 244 (51.8) | 546 (31.5) | |

| Intubation | 0 (0) | 55 (11.6) | 55 (3.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 363 (28.8) | 144 (30.4) | 507 (29.3) | 0.550 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 237 (18.8) | 93 (19.7) | 330 (19.1) | 0.744 |

| Chronic lung disease | 263 (20.9) | 128 (27.1) | 391 (22.6) | 0.008 |

| Chronic liver disease | 45 (3.6) | 30 (6.3) | 75 (4.3) | 0.017 |

| CHF | 98 (7.8) | 42 (8.9) | 140 (8.1) | 0.518 |

| CVA | 127 (10.1) | 54 (11.4) | 181 (10.5) | 0.473 |

| CKD | 127 (10.1) | 69 (14.6) | 196 (11.3) | 0.011 |

| Cancer | 410 (32.5) | 285 (60.2) | 695 (40.1) | |

| Lung cancer | 155 (12.3) | 119 (25.2) | 274 (15.8) | < 0.001 |

| Solid cancer | 169 (13.4) | 99 (20.9) | 268 (15.5) | 0.001 |

| Lung metastasis | 33 (2.6) | 26 (5.5) | 59 (3.4) | 0.005 |

| Hematologic cancer | 30 (2.4) | 25 (5.3) | 55 (3.2) | 0.004 |

| Lymphoma | 23 (1.8) | 16 (3.4) | 39 (2.3) | 0.078 |

| Confusion | 77 (6.1) | 60 (12.7) | 137 (7.9) | < 0.001 |

| SBP | 127 (111–143) | 121 (104–139) | 125 (109–142) | < 0.001 |

| DBP | 72 (64–83) | 69 (59–79) | 72 (62–82) | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate | 99 (86–113) | 108 (92–124) | 101 (87–116) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate | 20 (18–20) | 21 (20–24) | 20 (18–22) | < 0.001 |

| Body Temperature | 37.5 (36.9–38.3) | 37.5 (36.85–38.1) | 37.5 (36.9–38.2) | 0.253 |

| SpO2 | 96 (94–98) | 94 (89–96) | 95 (93–97) | < 0.001 |

Values are presented as number (%) or median (interquartile range).

ICU, intensive care unit; BMI, body mass index; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; HCAP, healthcare-associated pneumonia; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; CKD, chronic kidney disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation.

In a comparison between the control and case groups, patients in the case group were noted to be older (69 vs. 67 years old, P= 0.010) and were predominantly male (72.7 vs. 59.2%, P<0.001). In terms of the initial vital signs, the case group had lower blood pressure and SpO2 (systolic blood pressure, 121 vs. 127 mmHg; diastolic blood pressure, 69 vs. 72 mmHg; SpO2, 94 vs. 96%; P<0.001) as well as higher heart rate and respiratory rate (heart rate, 108 vs. 99/min; respiratory rate, 21 vs. 20/min; P<0.001).

Table 2 confirms the presence of pleural effusion and various initial laboratory findings in the study subjects. The case group is assigned more patients with significant pleural effusion (P<0.001), and had significantly lower hemoglobin, platelet, and albumin, as well as significantly higher lactic acid, procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine, than the control group.

Table 2.

Basic characteristics of the study subjects (radiological and laboratory findings)

| Control group (n = 1,259) | Case group (death or ICU admission) (n = 473) | Total (n = 1,732) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleural effusion on X-ray | 278 (22.1) | 179 (37.8) | 457 (26.4) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory finding | ||||

| pH | 7.46 (7.43–7.49) | 7.46 (7.41–7.49) | 7.46 (7.43–7.49) | 0.078 |

| pCO2 | 32.5 (28.7–37.1) | 31.5 (27.2–37.6) | 32.2 (28.2–37.2) | 0.133 |

| Lactic acid | 1.43 (1.11–1.93) | 2.07 (1.41–3.05) | 1.56 (1.16–2.22) | < 0.001 |

| Procalcitonin | 0.21 (0.1–0.66) | 0.53 (0.21–2.5) | 0.3 (0.12–1.07) | < 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein | 7.86 (2.98–15.1) | 11.45 (5.39–20.02) | 8.78 (3.63–16.5) | < 0.001 |

| WBC | 9.64 (7.09–13.5) | 10.08 (6.29–15.15) | 9.71 (6.91–13.8) | 0.458 |

| Segmented neutrophils | 77.4 (69–84.3) | 81.05 (69.9–86.5) | 78.5 (69.1–85) | 0.002 |

| ANC | 7.42 (5–11.0) | 8.08 (4.47–12.14) | 7.54 (4.89–11.2) | 0.385 |

| Hemoglobin | 12.6 (11.2–13.9) | 11.2 (9.7–12.8) | 12.3 (10.7–13.7) | < 0.001 |

| Platelet | 223 (169–286.5) | 206 (133–307) | 220 (163–290) | 0.010 |

| BUN | 14.5 (10.6–20.7) | 19.4 (12.8–31.6) | 15.4 (11.1–23.3) | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine | 0.83 (0.67–1.06) | 0.93 (0.67–1.43) | 0.85 (0.67–1.13) | < 0.001 |

| Glucose | 125 (109–159) | 136 (114.7–174) | 128 (110–163.5) | < 0.001 |

| Potassium (K+) | 4.2 (3.9–4.5) | 4.3 (3.9–4.8) | 4.2 (3.9–4.6) | < 0.001 |

| PT (INR) | 1.09 (1.02–1.18) | 1.17 (1.07–1.31) | 1.11 (1.03–1.22) | < 0.001 |

| Protein | 6.5 (6–7) | 6.2 (5.5–6.8) | 6.4 (5.9–6.9) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin | 3.8 (3.4–4.2) | 3.3 (3–3.8) | 3.7 (3.3–4.1) | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.001 |

| D-dimer | 1.36 (0.68–2.48) | 2.60 (1.33–4.80) | 1.78 (0.82–3.28) | < 0.001 |

| TCO2 | 20.8 (18.7–22.8) | 20.4 (18.0–23.1) | 20.7 (18.5–23) | 0.540 |

| NT-pro BNP | 984 (213.3–3,120) | 1,797 (767.5–5,882) | 1,305 (299.3–3,933) | 0.005 |

Values are presented as number (%) or median (interquartile range).

ICU, intensive care unit; pCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; TCO2, total carbon dioxide; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide.

The distribution of 30-day mortality or ICU admission from the ED according to the CURB-65 scores are listed in Table 3. Scores of 0 and 1 were distributed more in the control group, whereas scores of ≥2 were observed more in the case group. Because previous studies have set only 28- or 30-day mortality as the primary outcome, it is difficult to create a pure distribution of the mortality according to the CURB-65 scores for comparison with results from previous studies [20,23].

Table 3.

Distribution of CURB-65 scores between groups

| Control group (n = 1,259) | Case group (death or ICU admission) (n = 473) | Total (n = 1,732) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CURB-65 | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 Score | 480 (38.1) | 122 (25.8) | 602 (34.8) | |

| 1 Score | 557 (44.2) | 179 (37.8) | 736 (42.5) | |

| 2 Score | 186 (14.8) | 96 (20.3) | 282 (16.3) | |

| 3 Score | 33 (2.6) | 60 (12.7) | 93 (5.4) | |

| 4 Score | 3 (0.2) | 14 (3.0) | 17 (1.0) | |

| 5 Score | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.1) |

Values are presented as number (%).

ICU, intensive care unit.

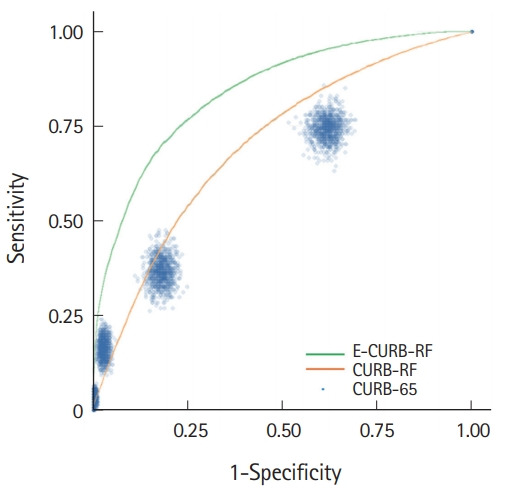

Comparison of three models

The AUROCs used to predict the primary outcome were 0.615 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.614–0.616), 0.701 (95% CI, 0.700–0.702), and 0.844 (95% CI, 0.843–0.845) for the CURB-65, CURB-RF, and E-CURB-RF models (Fig. 3). The ROC curves for 30-day mortality are shown in Appendix 3, the AUROCs of which are 0.581 (95% CI, 0.579–0.582) for CURB-65, 0.638 (95% CI, 0.636–0.639) for CURB-RF, and 0.822 (95% CI, 0.821–0.823) for E-CURB-RF model. A comparison of the performance of the three models is listed in Table 4. The performance of the CURB-65 model was evaluated based on a score of 2, which is the original cut-off point [23]. In the case of the CURB-RF and E-CURB-RF models, we choose the data that have the highest F1 scores for a sensitivity of 0.8 or more and specificity of 0.2 or more for each of the 1,000 models. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to confirm the significance among the three models and a post-hoc test was performed using Bonferroni correction. As a result, statistical significance was observed among the three models (P<0.001), except for the negative predictive value between two random forest models (P=0.083). The model with higher sensitivity is thus chosen if early treatment is important and to admit patients who are likely to worsen. The model with higher specificity is chosen if reducing medical care costs incurred by hospitalization of low-risk groups of pneumonia is the more important factor [24,25].

Fig. 3.

Comparison of receiver operating characteristics curves among the three models.

Table 4.

Comparison of performance among the three models

| CURB-65 | CURB-RF | E-CURB-RF | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area under the receiver operating characteristics | 0.615 (0.614–0.616) | 0.701 (0.700–0.702) | 0.844 (0.843–0.845) | < 0.001 |

| Sensitivity | 0.366 (0.364–0.368) | 0.924 (0.922–0.925) | 0.803 (0.803–0.803) | < 0.001 |

| Specificity | 0.820 (0.819–0.822) | 0.270 (0.266–0.274) | 0.711 (0.709–0.714) | < 0.001 |

| Positive predictive value | 0.505 (0.502–0.507) | 0.718 (0.717–0.719) | 0.848 (0.847–0.850) | < 0.001 |

| Negative predictive value | 0.722 (0.721–0.723) | 0.643 (0.640–0.647) | 0.642 (0.642–0.643) | < 0.001 |

| Accuracy | 0.669 (0.668–0.670) | 0.706 (0.705–0.707) | 0.773 (0.772–0.773) | < 0.001 |

| F1 score | 0.424 (0.422–0.426) | 0.808 (0.807–0.808) | 0.825 (0.824–0.826) | < 0.001 |

All the variables in Appendix 1 were used for the machinelearning algorithm, and the top 5 variables in the dataset that had the highest area under the curve values among the 1,000 E-CURB-RF models are serum lactic acid, serum albumin, hemoglobin, D-dimer, and peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, respectively. Although there may be differences in the types of top-10 variables for every 1,000 models, it is expected that the difference would not be significant.

DISCUSSION

There have been a few studies using machine-learning methods to predict mortality from pneumonia [17-20], and a few studies have included patients who visited an ED [20]. Previous studies on predicting mortality from pneumonia for CURB-65 demonstrated an AUROC range of approximately 0.6 to 0.75 [18,20,26,27], and this study showed an AUROC of 0.615 (95% CI, 0.614–0.616). In fact, the AUROC value of CURB-65 for 30-day mortality was only 0.581 (95% CI, 0.579–0.582), which is considered to be an extremely low predictive power compared to other reported studies.

Machine-learning involves scientific studies focusing on how computers learn trends from data [13]. One of the remarkable characteristics of machine learning is the improvement observed with additional learning [16]. This study suggests that machine-learning methods perform better than the existing CURB-65 model with regard to predicting the 30-day mortality or ICU admission of patients with pneumonia. By comparing the CURB-65 and CURB-RF models, it is observed that using a continuous value through a machine-learning method is more advantageous than dividing the dichotomous cutoffs by a clinician to improve predictive power. Furthermore, by comparing the CURB-RF and E-CURB-RF models, it is confirmed that when greater number of variables are considered, the AUROC values are higher. As the CURB-RF model has higher sensitivity than the E-CURB-RF model (0.924 vs. 0.803), but lower specificity of 0.270, the use of the CURB-RF model as a predictive model seems to be challenging. In practice, there has been a preference toward quick and convenient models, such as CURB-65 consisting of five variables, and q-SOFA consisting of three variables, in an ED setting. It is expected that the inconvenience of a complex model comprising more variables will be complemented by advances in machine-learning methods.

Unlike other studies, the 30-day mortality or ICU admission from the ED were included in the primary outcomes of this study. As predicting not only the 30-day mortality and deciding whether patients require admission but also whether they should be admitted to an ICU is crucial, the setting of primary outcomes seems meaningful. Unfortunately, the ICU admission rate of patients having pneumonia was underestimated. The rate was measured only when patients having pneumonia were admitted directly from the ED to an ICU; consequently, the cases of patients transferring to an ICU through general wards were missing. Therefore, analyzing cases of ICU transfer within 24 or 48 hours after a general ward admission is necessary to determine the factors for predicting patient deterioration.

According to Appendix 2, of the 358 deaths within the 30-day period, 295 were admitted to the general ward, and 63 to the ICU initially. In general, similar to that in other hospitals, physicians determined admission to an ICU if patients had an intubation, high vasopressor requirements, or needed intensive intervention such as continuous renal replacement therapy [28,29]. However, whether the patient is in a “Do not resuscitate (DNR)” state is also an important factor in terms of ICU care and limit of ICU capacity. It can be assumed that the number of patients with DNR setting is high owing to the high proportion of history of cancer or chronic medical disease in the hospital where this study was being conducted. Furthermore, the “ICU admission” of “Death within 30-day” group showed worse laboratory findings such as significantly lower albumin, higher lactic acid, procalcitonin, Creactive protein, and creatinine than the “No ICU” of “Death within 30-day” group. It can be inferred that patients with possibility of deterioration or possibility of hemodialysis due to high creatinine were preferentially selected to ICU admission. In addition, the higher the CURB-65 score, the more patients were admitted to an ICU. To identify ICU admission criteria in this study, supplementing several variables such as use of vasopressors and its dosage and whether a person has DNR status is necessary.

This study has several limitations, one of which was being a retrospective analysis conducted at a single, tertiary referral center. As can be seen in Table 1, 40.1% of patients had a history of cancer and 36.5% were non–community-acquired pneumonia patients, and the distribution might be likely to be different compared to other hospitals. Because a machine learning method is used to select the appropriate variables to create a model from an original dataset through a learning process, it can be inferred that whenever machine learning models are created based on the individual data from different hospitals, the models will reflect the specific characteristics of each hospital. In other words, the E-CURB-RF model created in this study cannot accurately demonstrate the validity of the dataset of other hospitals. In this aspect, a data analysis of multiple centers of the same level is necessary.

Furthermore, it is expected that each time another machine learning method such as deep learning is used, new models comprising different variables with different weighted values will appear. This characteristic can put the reliability in doubt; however, random forest is the most popular ensemble technique used to solve classification problems based on large data and is widely used in various fields, including medicine [30-32]. Random forest builds a set of decision trees based on the bagging and bootstrap technique. In general, the number of trees is sufficient, the models’ error rate is low and its prediction is stable [30], and this robust nature meets medical needs. Besides, because the highly weighted variables used herein have already been known to be important factors in previous studies [11,33], the results are reliable to a certain degree.

In this study, there might be a concern in that it is difficult to explain the cause of death within 30 days as being from pneumonia alone because the case group had significantly more patients with a history of cancer. In fact, however, history of cancer was not included in the highly weighted variables and likely did not have a significant impact on the outcome.

Owing to the limitation of retrospective studies, many cases that were diagnosed as having pneumonia but not recorded in the pneumonia registry might have been missed. There is also a limitation in that 1,974 data were analyzed by three clinicians during the data collection process. Even if certain criteria are determined prior to an EMR review, it is possible that each clinician evaluates the data differently.

The results were not compared with various other pre-existing prediction models such as the PSI score or SOFA score, which are frequently used in ICU care. However, this study is conducted on the ED setting that routinely calculates the CURB-65 score, and obtaining the components of other pre-existing models such as Glasgow coma scale score, vasoactive dosage, and partial pressure of arterial oxygen is difficult. There will be several missing values that makes comparison difficult. In the future, prospective studies are needed to apply a new machine learning-based model complemented by improving the above-mentioned limitations for patients having pneumonia visiting an ED.

In summary, we established that a machine learning-based model can predict the mortality of patients with pneumonia in an ED more accurately than pre-existing CURB-65 and help decide whether ICU care needs to be pursued.

Appendix 1.

Variables used for each model

Appendix 2.

Basic characteristics of the study subjects stratified by death within 30 days and ICU admission

Appendix 3.

Comparison of receiver operating characteristics curves among the three models for 30-day mortality.

Capsule Summary

What is already known

Pneumonia is the leading cause of death from infectious diseases, and thus the importance has been given to its disposition based on different severity scores.

What is new in the current study

This study suggests that a machine-learning-based model can predict the mortality of pneumonia patients in an emergency department more accurately than pre-existing CURB-65 and help decide whether to pursue intensive care unit care.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aliberti S, Ramirez J, Cosentini R, et al. Low CURB-65 is of limited value in deciding discharge of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Med. 2011;105:1732–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garibaldi RA. Epidemiology of community-acquired respiratory tract infections in adults: incidence, etiology, and impact. Am J Med. 1985;78(6B):32–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates JH, Campbell GD, Barron AL, et al. Microbial etiology of acute pneumonia in hospitalized patients. Chest. 1992;101:1005–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang GD, Fine M, Orloff J, et al. New and emerging etiologies for community-acquired pneumonia with implications for therapy: a prospective multicenter study of 359 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69:307–16. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrie TJ, Durant H, Yates L. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization: 5-year prospective study. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:586–99. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortqvist A, Sterner G, Nilsson JA. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: factors influencing need of intensive care treatment and prognosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1985;17:377–86. doi: 10.3109/13813458509058778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pachon J, Prados MD, Capote F, Cuello JA, Garnacho J, Verano A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: etiology, prognosis, and treatment. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:369–73. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torres A, Serra-Batlles J, Ferrer A, et al. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: epidemiology and prognostic factors. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:312–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodhead MA, Macfarlane JT, McCracken JS, Rose DH, Finch RG. Prospective study of the aetiology and outcome of pneumonia in the community. Lancet. 1987;1:671–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruger S, Ewig S, Marre R, et al. Procalcitonin predicts patients at low risk of death from community-acquired pneumonia across all CRB-65 classes. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:349–55. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00054507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH, Kim J, Kim K, et al. Albumin and C-reactive protein have prognostic significance in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Crit Care. 2011;26:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siljan WW, Holter JC, Michelsen AE, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers are associated with aetiology and predict outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia: results of a 5-year follow-up cohort study. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5:00014–2019. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00014-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deo RC. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation. 2015;132:1920–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jha S, Topol EJ. Adapting to artificial intelligence: radiologists and pathologists as information specialists. JAMA. 2016;316:2353–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharya S, Rajan V, Shrivastava H. ICU mortality prediction: a classification algorithm for imbalanced datasets. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017 Feb 4-9; San Francisco, CA, USA. Menlo Park, CA. 2017. pp. 1288–94. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon JG, Heo J, Kim M, et al. Machine learning-based diagnosis for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC): development, external validation, and comparison to scoring systems. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper GF, Aliferis CF, Ambrosino R, et al. An evaluation of machine-learning methods for predicting pneumonia mortality. Artif Intell Med. 1997;9:107–38. doi: 10.1016/s0933-3657(96)00367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logan WM, Campos CC, Ceccato A, Gabarrus A, Amaro R, Torres A. A machine-learning model for prediction of mortality among patients with community-acquired pneumonia. In: 29th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases; 2019 Apr 13-16; Amsterdam, Netherland. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiemken TL, Furmanek SP, Mattingly WA, et al. Predicting 30-day mortality in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia using statistical and machine learning approaches. Univ Louisville J Respir Infect. 2017;1:50–6. doi: 10.18297/jri/vol1/iss1/1/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bae Y, Moon HK, Kim SH. Predicting the mortality of pneumonia patients visiting the emergency department through machine learning. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2018;29:455–64. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederman MS, Bass JB, Jr, Campbell GD, et al. Guidelines for the initial management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: diagnosis, assessment of severity, and initial antimicrobial therapy. American Thoracic Society. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1418–26. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2010;45:1–68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377–82. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colice GL, Morley MA, Asche C, Birnbaum HG. Treatment costs of community-acquired pneumonia in an employed population. Chest. 2004;125:2140–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.6.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guest JF, Morris A. Community-acquired pneumonia: the annual cost to the National Health Service in the UK. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1530–4. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10071530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahn BK, Lee YS, Kim YJ, et al. Prediction model for mortality in cancer patients with pneumonia: comparison with CURB-65 and PSI. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:538–46. doi: 10.1111/crj.12560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez C, Johnson T, Rolston K, Merriman K, Warneke C, Evans S. Predicting pneumonia mortality using CURB-65, PSI, and patient characteristics in patients presenting to the emergency department of a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer Med. 2014;3:962–70. doi: 10.1002/cam4.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdel Aziz AO, Abdel Fattah MT, Mohamed A, Abdel Aziz MO, Mohammed MS. Mortality predictors in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia requiring ICU admission. Egypt J Bronchology. 2016;10:155–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KH. Patient stratification and decision to hospitalize patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Korean Med Assoc. 2007;50:868–76. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goel E, Abhilasha E. Random forest: a review. Int J Adv Res Comput Sci Softw Eng. 2017;7:251–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao M, Yan H, Song J, Yang Y, Yang X. Sleep stages classification based on heart rate variability and random forest. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2013;8:624–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang F, Wang HZ, Mi H, Lin CD, Cai WW. Using random forest for reliable classification and cost-sensitive learning for medical diagnosis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10 Suppl 1:S22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-S1-S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demirel B. Lactate levels and pneumonia severity index are good predictors of in-hospital mortality in pneumonia. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:991–5. doi: 10.1111/crj.12616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]