Abstract

Lymphangiosarcoma, or Stewart-Treves Syndrome (STS), is a very rare skin angiosarcoma with poor prognosis, which usually affects the upper limbs of patients who underwent breast cancer surgery, including axillary dissection followed by radiotherapy (RT). Cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas, which account for approximately 5% of all angiosarcomas, usually originate in the limb with chronic lymphedema. Lymphatic blockade is involved in the onset of STS. RT contributes indirectly to an increased risk of developing STS by causing axillary-node sclerosis and resulting in a lymphatic blockade and lymphedema. Chronic lymphedema causes local immunodeficiency, which indirectly leads to oncogenesis. Currently, axillary nodes are no longer routinely irradiated after axillary dissection, which is associated with a reduction in the incidence of chronic lymphedema from 40% to 4%. The use of sentinel lymph node biopsy technique is also widespread and the associated risk of lymphedema is further reduced. Thus, the incidence of STS decreased significantly with improved surgical and radiation techniques. The overall prognosis of STS patients is very poor. Only early radical surgical removal, including amputation or disarticulation of the affected limb, or wide excision at an early stage offers the greatest chance of long-term survival. Only a few case reports and series with a small number of patients with lymphangiosarcoma can be found in the literature. We present a case report of the first diagnosed STS at our department in an effort to highlight the need of the consideration of developing lymphangiosarcoma in patients with chronic lymphedema.

Keywords: Stewart-Treves syndrome, Lymphangiosarcoma, Angiosarcoma, Radiotherapy, Breast cancer

1. Introduction

Lymphangiosarcoma, or Stewart-Treves Syndrome (STS), is a very rare skin angiosarcoma with very poor prognosis, which usually affects the upper limbs of patients who have undergone breast cancer surgery, including axillary dissection followed by radiotherapy (RT).1,2 The association between chronic lymphedema and the development of lymphangiosarcoma is typical.3 A major challenge physicians face when treating lymphangiosarcoma is a sheer lack of information. The mainstay of treatment is surgery. The role and choice of systemic treatment are unclear due to the lack of evidence-based data. Only few case reports and series with a small number of patients with lymphangiosarcoma can be found in the literature. We present in this article a case report of the first diagnosed STS at our department, together with a literature review.

2. Case report

A 56-year-old female patient underwent right-sided mastectomy and axillary dissection in August 2011 with the finding of multilocular ductal carcinoma of the right breast with lymphangioinvasion and extranodal invasion - pT2(2)pN3aM0, nodes 10/17, grade 3, triple negative, MIB1 90 %. BRCA1/2 gene mutations were not investigated. Between August and December 2011, she received 6 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with TAC (docetaxel, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide). Subsequently, in January and February 2012, she underwent adjuvant RT of the right chest wall, axilla and periclavicular area (50 Gy in 25 fractions á 2 Gy per fraction) using 3D conformal RT on a linear accelerator. The patient had Crohn's disease with sigmoid stenosis, hyperthyroidism and glucose tolerance disorder. Breast cancer remained in complete remission throughout treatment of STS.

Already in November 2012, 15 months after the surgical procedure and 9 months after the end of adjuvant radiotherapy, she had lymphedema on the upper right limb with a maximum on the dorsal side of the arm and forearm. The back of the hand and the fingers weren't swollen. The patient refused the recommended lymphotherapy, wearing only a compression sleeve. In March 2014, lymphedema spread to the back of the hand, but the patient continued to refuse the lymphotherapy. Lymphedema then did not change its extent and character in time. In December 2018, the patient still refused the lymphotherapy, continued to wear a compression sleeve.

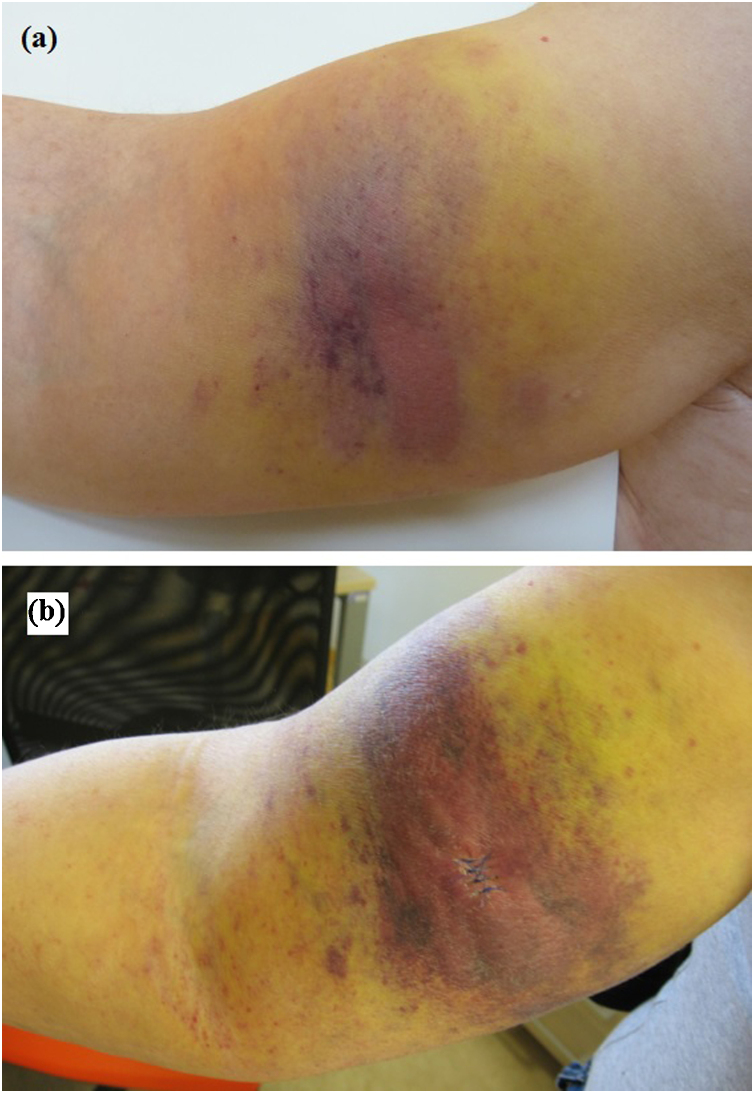

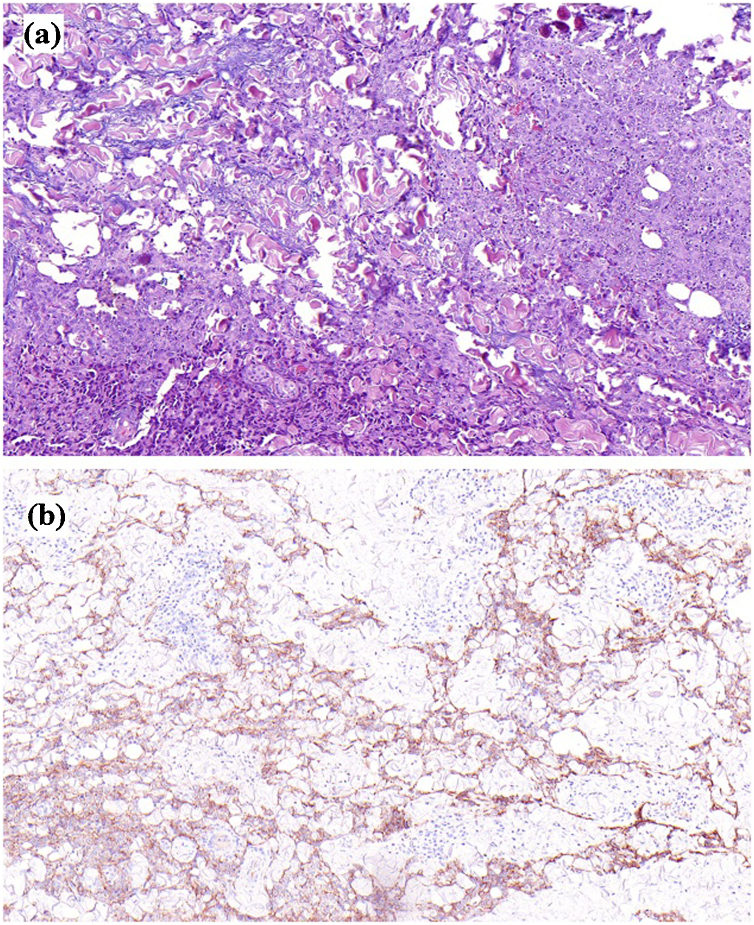

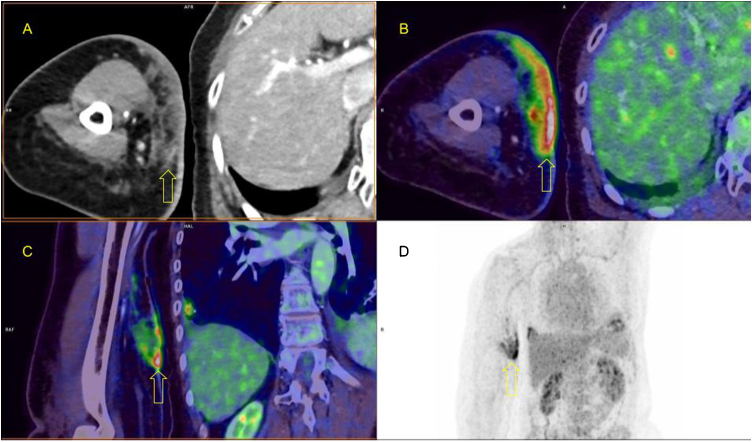

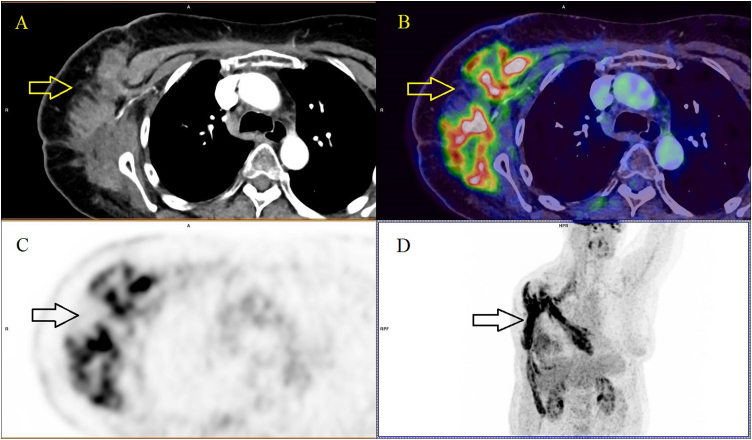

In January 2020, 8 years after the initial diagnosis, she attended a dermatology clinic for a three-week history of progressive hematoma on her right arm, without previous trauma. The local finding was described as a large hematoma about 15 cm in size on the inside of the right arm, centrally with erythema and stiffness. There was a slight erythema dorsally on the arm, warm to the touch (Fig. 1a). Ultrasound did not detect an expansive process, only suspected subcutaneous inflammatory infiltration. The finding was assessed as suspected erysipelas and the patient was treated with antibiotics (penicillin). There was no improvement reported in one week, on the contrary, a highlighted solid infiltrate with a color change of the skin (livid in the center, yellow around) and surrounded with tiny pink areas (Fig. 1b). Because of a suspicion of a vascular tumor, a probatory excision from the lesion was performed. In a subsequent histological examination, vascular breakthroughs in the dermis lined with polygonal polymorphic cells with large nucleoli and high proliferative activity (MIB1 50 %) were revealed. Immunohistochemically, the cells expressed D2-40, CD31 and factor VIII (CD20, MPOX and CD34 were negative) (Fig. 2). Based on the morphology, immunoprofile, and clinical presentation, the patient (at the age of 64) was diagnosed with Stewart-Treves Syndrome. Immediately thereafter, the patient underwent FDG (18F-fluorodeoxyglucose)-PET/CT (positron emission tomography/computed tomography) examination with the finding of the unfocused FDG accumulating infiltration of the subcutaneous fat layer on the inside of the right arm (range 10 × 7 cm; SUVmax = 9), at a depth reaching up to the musculus biceps brachii with its mild infiltration (Fig. 3). No distant metastases were found, but with an accidental finding of a bilateral pulmonary embolism. Subsequently, deep vein thrombosis of the left popliteal and fibular veins was found. The patient was further indicated for anticoagulation therapy, introduction of a caval filter and for immediate surgical treatment. In February 2020 she underwent an exarticulation of the right upper limb. Macroscopically, a dark violet plaque on an area of 15 × 10 cm of hematoma appearance was described on the back of the arm, forming a multicystic formation filled with blood, reaching up to 5 cm. Histological examination confirmed a vascular tumor, irregularly and diffusely growing subepidermally and made up of large polymorphic cells with high proliferative activity (Ki-67 estimated 50 %). Immunohistochemically, the cells expressed CD31, D2-40 and factor VIII only sporadically, CD34 was negative. It was thus lymphangiosarcoma. Adjuvant therapy was not indicated, the patient was only followed up. However, an early FDG-PET/CT examination in April 2020 revealed extensive infiltration with high accumulation around the stump with involvement of the deltoid muscle, the latissimus dorsi muscle and the pectoralis muscle, no distant metastases were found (Fig. 4). Immediately thereafter, she was indicated to palliative chemotherapy with ifosfamide (3 g/m2 i.v. day 1–3). After the first cycle, in May 2020, the overall condition of the patient deteriorated. Weakness, fatigue and anorexia were present. There were only small purple lesions on the skin of the stump. However, extensive right-sided fluidotorax and progression of the extent of local recurrence were described on CT examination. Furthermore, she was treated symptomatically, but she died shortly afterwards. The overall survival (OS) of STS, calculated from the initial biopsy, was 4 months.

Fig. 1.

Large hematoma-like lesion on the inside of the right arm, centrally with erythema (a). One week later - highlighted solid infiltrate with a color change of the skin and tiny pink areas around (b).

Fig. 2.

Varying growth patterns of the neoplastic proliferation could be recognized; irregular vessels dissecting the dermis, solid or infiltrative growth of neoplastic cells between collagen bundles were found (a). Immunostain for D2-40 (podoplanin) shows an intense staining of the neoplastic cells (b).

Fig. 3.

FDG-PET/CT examination. 18F-FDG avid infiltration (arrow) of the skin and subcutaneous tissue at the right arm (A-axial CT image; B-axial fused image; C-coronal fused image; D-PET image).

Fig. 4.

FDG-PET/CT examination. 18F-FDG avid infiltration (arrow) of the stump with involvement of the deltoid muscle, the latissimus dorsi muscle and the pectoralis muscle (A-axial CT image; B-axial fused image; C-axial PET image; D-coronal PET image).

3. Discussion and literature review

Angiosarcomas, accounting for only 2% of all sarcomas,4 originate either from the endothelium of blood vessels – hemangiosarcomas – or more rarely from the endothelium of lymphatic vessels – lymphangiosarcomas. Hemangiosarcomas are usually localized to the skin and most of them originated in irradiated area, typically after breast conserving surgery6,7 – secondary hemangiosarcomas. Cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas, which account for approximately 5% of all angiosarcomas,8 usually originate on the limb with chronic lymphedema. The association between chronic lymphedema and the development of lymphangiosarcoma, now known as Stewart-Treves Syndrome, was first described in 1948 by Dr. Fred W. Stewart, Professor of Pathology, and Dr. Norman Treves, Associate Professor of Surgery, both from the Cornell University Medical College, New York, N.Y., USA. The authors described 6 cases of angiosarcomas growing in the field of postmastectomic lymphedema in the upper limb, then called “elephantiasis chirurgica”.3 Its incidence is reported to be between 0.07 and 0.45% in breast cancer patients surviving at least 5 years after radical mastectomy9 and it most commonly affects women aged 65–70 years.10 Extremely rare is lymphangiosarcoma in the lower limbs. Here it occurs most often as a result of idiopathic chronic lymphedema,11,12 sometimes to the appearance of elephantiasis.13

With regard to etiopathogenesis, lymphatic blockade, manifested by chronic lymphedema, is involved in the onset of STS. The affected limb is not, as is evident, directly irradiated. Thus, RT contributes indirectly to an increased risk of developing STS by causing axillary-node sclerosis and resulting in lymphatic blockade and lymphedema.14 Why this chronic lymphedema can lead to lymphangiosarcoma is still unclear and controversial, but there are several theories. One of them claims that chronic lymphedema causes local immunodeficiency, which indirectly leads to oncogenesis.15 The local immune response in the affected limb is altered by protein-rich interstitial fluid and the lymphatic channels enriched with growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF),1 stimulating lymphangiogenesis and the development of collateral vessels.9 When local immune surveillance mechanisms fail, the lymphedema area becomes an immunologically vulnerable area, predisposed to malignancies such as vascular tumors.16 The DNA mutation of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 repair genes also predisposes patients to develop angiosarcoma after breast cancer treatment.17 The interval for developing lymphangiosarcoma in the patient presented by us was 8 years, which corresponds to published data.5 Currently, axillary nodes are no longer routinely irradiated after axillary dissection, which is associated with a reduction in the incidence of the chronic lymphedema from 40% to 4%.18 The use of sentinel lymph node biopsy technique is also widespread and the associated risk of lymphedema is further reduced. Thus, the incidence of STS decreased significantly with improved surgical and radiation techniques.11

STS usually manifests as fast-growing multiple red-blue macules with surrounding indurations, turning into plaques of coalescing purple papules with necrotic precincts.1 Sometimes, the clinical finding may have the appearance of non-resorbing hematoma, as was the case with our patient. Before the lesions appear, the lymphedema of the upper limb may gradually spread from the arm to the forearm, the dorsal part of the hand to the toes.19 As the lesions increase, the overlapping atrophic skin may ulcerate, which may further lead to infection and bleeding.12 The most common sites of possible metastatic spread are the lungs and the thoracic wall, followed by the liver, bones, soft tissues and lymph nodes.2,9,17,20 Our patient´s STS presented with very aggressive locally infiltrative nature, without distant metastases.

In differential diagnosis, both benign (acquired angioedema, ecchymosis, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangiectasis, angioendotheliomatosis, benign lymphangioendothelioma, lymphangioma, cellulitis), as well as malignant diseases such as melanoma or skin metastases of other tumors (usually breast cancer), should be considered.1,9,20 The most important thing is to distinguish Kaposi's sarcoma. Immunohistochemical testing for the presence of HHV-8 virus helps here. Kaposi's sarcoma is associated with this virus, STS is not.17

Histopathological and immunohistochemical examination is essential for the diagnosis of STS. Immunohistochemical antibodies against endothelial cells are typically the stain of choice. However, not all malignant endothelial cells are positive for these markers; therefore, a panel of immunohistochemical stains should be used to avoid false negativity.17 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) together with PET/CT examination help to evaluate the exact extent of the disease and, thus, to choose the most appropriate treatment strategy for the patient.21

Regardless of the treatment modality chosen, the overall prognosis of STS patients is very poor with a high number of local and distant recurrences.22 OS ranges between 18 and 31 months.23,24,27 Most patients die of metastatic disease within 2 years.9,12,17 Untreated patients usually live only 5–8 months after diagnosis.11 We were dealing with a very aggressive tumor, as OS was only 4 months despite radical surgery and early initiation of palliative chemotherapy, albeit only 1 cycle. The treatment principles are not created on evidence-based practice, but rather on limited data from case reports or series with a small number of patients. The treatment strategy should be complex. Early radical surgical removal, including amputation or disarticulation of the affected limb, or wide excision at an early stage offers the greatest chance of long-term survival.25 Roy et al.26 report cases of five STS patients treated in their center. In four of them, forequarter amputation was performed and they were alive and disease-free at 3, 16, 23 and 135 months. One patient declined amputation, and isolated limb perfusion using melphalan and TNF-alpha was performed followed by débridement of residual tumour, but finally palliative forequarter amputation was performed because of recurrent disease. She died from metastatic oesophageal carcinoma. On the other hand, Farzaliyev et al.24 describe two cases in which they performed the radical subfascial skin excision of the affected arm followed by mesh skin graft transplantation from both thighs. In both cases the axillary hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion (HILP) with TNF-alpha and high-dose melphalan was used (in one case as a non-curative, in the other as a neoadjuvant treatment method). A complete pathological response was observed after neoadjuvant treatment, no response was observed after non-curative treatment. The first patient had no evidence of disease 18 months after surgery, the latter patient died 18 months after the first presentation of disease. McKeown et al.27 report the case of a patient with STS developing 15 years after the initial diagnosis of breast cancer, who refused a surgical procedure and was treated with doxorubicin. She also died in 18 months. Regarding other treatment modalities, there is no difference in OS when using RT or chemotherapy. Among available cytostatics, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, bleomycin, actinomycin D, vincristine, doxorubicin, metronomic cyclophosphamide with prednisolone, paclitaxel, ifosfamide and dacarbazine can be used therapeutically.9,12,17,24,28 Some authors favor the use of paclitaxel as a first-line treatment of the advanced or metastatic angiosarcoma. Paclitaxel with or without bevacizumab, VEGF inhibitor, was tested in a randomized phase II trial.29 The study found that both paclitaxel with and without bevacizumab were supported as active treatment regimens, although they did not find a benefit of adding bevacizumab. However, bevacizumab as a monotherapy is an attractive option for a second-line treatment.30 Pazopanib, a multityrosine kinase inhibitor, also showed promising results and should also be considered as one of the second-line treatment options.31 The use of neoadjuvant HILP has also the potential to improve local control.24,26,32

A better understanding of the pathogenesis of angiosarcomas may result in better targeting of effective treatment. Further efforts to influence VEGF, which is a potent angiogenic factor and has also been shown in angiosarcomas, may improve treatment outcomes in the future, as mentioned above.33,34 Several studies also have shed light on the role of the immune system in patients with angiosarcoma, and these reports show that patients may benefit from anti-PD-1 (programmed death) therapy.35,36 As for a possible preventive action, the use of lymphatic supermicrosurgery for the treatment of chronic lymphedema, such as vascularised lymph node transfer, or lymphovenous anastomosis, can probably further decrease the incidence of STS.37,38

4. Conclusion

The possibility of developing lymphangiosarcoma should be considered in patients with chronic lymphedema. In particular, the inexplicable expanding plaques of coalescing purple papules deserve great attention. However, despite early diagnosis, the overall prognosis of STS patients is very poor with a high number of local and distant recurrences.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Conflict of interest

Declaration

The patient has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal. She signed an informed consent regarding publishing her pictures.

Acknowledgments

None declared.

References

- 1.Gottlieb R., Serang R., Chi D., Menco H. Stewart-Treves syndrome. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;7(4):693. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v7i4.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodward A.H., Ivins J.C., Soule E.H. Lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous extremities. Cancer. 1972;30(2):562–572. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197208)30:2<562::aid-cncr2820300237>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart F.W., Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema; a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1(1):64–81. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(194805)1:1<64::aid-cncr2820010105>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mark R.J., Poen J.C., Tran L.M., Fu Y.S., Juillard G.F. Angiosarcoma. A report of 67 patients and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1996;77(11):2400–2406. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2400::AID-CNCR32>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cozen W., Bernstein L., Wang F., Press M.F., Mack T.M. The risk of angiosarcoma following primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;81(3):532–536. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fineberg S., Rosen P.P. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102(6):757–763. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/102.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vojtíšek R., Kinkor Z., Fínek J. Secondary angiosarcomas after conservation treatment for breast cancers. Klin Onkol. 2011;24(5):382–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nascimento A.F., Raut C.P., Fletcher C.D. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast: Clinicopathologic analysis of 49 cases, suggesting that grade is not prognostic. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(12):1896–1904. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318176dbc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma A., Schwartz R.A. Stewart-Treves syndrome: Pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(6):1342–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sordillo P.P., Chapman R., Hajdu S.I., Magill G.B., Golbey R.B. Lymphangiosarcoma. Cancer. 1981;48(7):1674–1679. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811001)48:7<1674::aid-cncr2820480733>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berebichez-Fridman R., Deutsch Y.E., Joyal T.M. Stewart-Treves syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol. 2016;9(1):205–211. doi: 10.1159/000445427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHaffie D.R., Kozak K.R., Warner T.F., Cho C.S., Heiner J.P., Attia S. Stewart-Treves syndrome of the lower extremity. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(21):e351–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shavit E., Alavi A., Limacher J.J., Sibbald R.G. Angiosarcoma complicating lower leg elephantiasis in a male patient: An unusual clinical complication, case report and literature review. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2018;6:1–5. doi: 10.1177/2050313X18796343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schirger A. Postoperative lymphedema: Etiologic and diagnostic factors. Med Clin North Am. 1962;46:1045–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)33688-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanczyk M., Gewartowska M., Swierkowski M., Grala B., Maruszynski M. Stewart-Treves syndrome angiosarcoma expresses phenotypes of both blood and lymphatic capillaries. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126(2):231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruocco V., Schwartz R.A., Ruocco E. Lymphedema: an immunologically vulnerable site for development of neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(1):124–127. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young R.J., Brown N.J., Reed M.W., Hughes D., Woll P.J. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):983–991. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee R., Saardi K.M., Schwartz R.A. Lymphedema-related angiogenic tumors and other malignancies. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(5):616–620. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aygit A.C., Yildirim A.M., Dervisoglu S. Lymphangiosarcoma in chronic lymphoedema. Stewart-Treves syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 1999;24(1):135–137. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1998.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grobmyer S.R., Daly J.M., Glotzbach R.E., Grobmyer A.J., 3rd Role of surgery in the management of postmastectomy extremity angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome) J Surg Oncol. 2000;73(3):182–188. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(200003)73:3<182::aid-jso14>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi P., Lele V., Gandhi R. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan and nuclear magnetic resonance findings in a case of Stewart-Treves syndrome. J Cancer Res Ther. 2011;7(3):360–363. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.87014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naka N., Ohsawa M., Tomita Y. Prognostic factors in angiosarcoma: A multivariate analysis of 55 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;61(3):170–176. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199603)61:3<170::AID-JSO2>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chopra S., Ors F., Bergin D. MRI of angiosarcoma associated with chronic lymphoedema: Stewart Treves syndrome. Br J Radiol. 2007;80(960):e310–3. doi: 10.1259/bjr/19441948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farzaliyev F., Hamacher R., Steinau Professor H.U., Bertram S., Podleska L.E. Secondary angiosarcoma: A fatal complication of chronic lymphedema. J Surg Oncol. 2020;121(1):85–90. doi: 10.1002/jso.25598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.di Meo N., Drabeni M., Gatti A., Trevisan G. A Stewart-Treves syndrome of the lower limb. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18(6):14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy P., Clark M.A., Thomas J.M. Stewart-Treves syndrome--treatment and outcome in six patients from a single centre. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30(9):982–986. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKeown D.G., Boland P.J. Stewart–Treves syndrome: A case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(5):e80–e82. doi: 10.1308/003588413X13629960046110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shon W., Ida C.M., Boland-Froemming J.M., Rose P.S., Folpe A. Cutaneous angiosarcoma arising in massive localized lymphedema of the morbidly obese: A report of five cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38(7):560–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ray-Coquard I.L., Domont J., Tresch-Bruneel E. Paclitaxel given once per week with or without bevacizumab in patients with advanced angiosarcoma: A randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2797–2802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agulnik M., Yarber J.L., Okuno S.H. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(1):257–263. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kollár A., Jones R.L., Stacchiotti S. Pazopanib in advanced vascular sarcomas: An EORTC Soft tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (STBSG) retrospective analysis. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2017;56(1):88–92. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1234068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevenson M.G., Hoekstra H.J., Song W., Suurmeijer A.J.H., Been L.B. Histopathological tumor response following neoadjuvant hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion in extremity soft tissue sarcomas: Evaluation of the EORTC-STBSG response score. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(9):1406–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zietz C., Rössle M., Haas C. MDM-2 oncoprotein overexpression, p53 gene mutation, and VEGF up-regulation in angiosarcomas. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(5):1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65729-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLaughlin Er, Brown Lf, Weiss Sw, Mulliken Jb, Perez-Atayde A., Arbiser Jl. VEGF and its receptors are expressed in a pediatric angiosarcoma in a patient with Aicardi's syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114(6):1209–1210. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00005-3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishida Y., Otsuka A., Kabashima K. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: Update on biology and latest treatment. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30(2):107–112. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimizu A., Kaira K., Okubo Y. Positive PD-L1 expression predicts worse outcome in cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Glob Oncol. 2016;3(4):360–369. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.005843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang D.W., Suami H., Skoracki R. A prospective analysis of 100 consecutive lymphovenous bypass cases for treatment of extremity lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(5):1305–1314. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4d626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engel H., Lin C.Y., Huang J.J., Cheng M.H. Outcomes of lymphedema microsurgery for breast cancer-related lymphedema with or without microvascular breast reconstruction. Ann Surg. 2018;268(6):1076–1083. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]