Abstract

The occurrence of human pathogenic viruses in aquatic ecosystems and, in particular, in internal water bodies (i.e., river, lakes, groundwater, drinking water reservoirs, recreational water utilities, and wastewater), raises concerns regarding the related impacts on environment and human health, especially in relation to the possibility of human exposure and waterborne infections. This paper reviews the current state of knowledge regarding severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) presence and persistence in human excreta, wastewaters, sewage sludge as well as in natural water bodies, and the possible implications for water services in terms of fecal transmission, public health, and workers’ risk. Furthermore, the impacts related to the adopted containment and emergency management measures on household water consumptions are also discussed, together with the potential use of wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) assessment as a monitoring and early warning tool, to be applied in case of infectious disease outbreaks. The knowledge and tools summarized in this paper provide a basic information reference, supporting decisions makers in the definition of suitable measures able to pursue an efficient water and wastewater management and a reduction of health risks. Furthermore, research questions are provided, in order to direct technical and public health communities towards a sustainable water service management in the event of a SARS-CoV-2 re-emergence, as well as a future deadly outbreak or pandemic.

Keywords: Fecal transmission, Public health, SARS-CoV-2, Urban water cycle, Wastewater-based epidemiology

Graphical abstract

The current knowledge on the SARS-CoV-2 in water services has been reviewed. The main challenges related to an efficient water and wastewater management have been discussed in order to guarantee public health and reduce risks during future deadly outbreak or pandemic.

1. Introduction

On December 31, 2019, the China Country Office of the World Health Organization (WHO) was alerted to a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown aetiology in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China (WHO, 2020a). On January 9, 2020, Chinese authorities confirmed that they had identified a novel (new) coronavirus as the cause of the pneumonia (XinhuaNet, 2020). The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) named the virus as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and the disease as COVID-19 (Gorbalenya et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 has spread globally, and currently (as of September 27, 2020), according to the daily report of the WHO, the world registered over 32.7 million confirmed cases and 991,000 deaths in 146 countries (WHO, 2020b). This dramatic world health emergency is a clear example of the new problems and challenges related to a rapidly changing world. In order to minimize negative impacts on human health, environment and economy, it is crucial to reduce transmission routes and risks of contagion and promote suitable policies aimed at improving the rational use of natural resources, the sustainability of production processes and environmental protection. Actions addressed to a rational management of water resources, wastewater, and waste should be included into an overall strategy aimed at tackling the impacts of the pandemic.

Coronaviruses (CoVs) belong to the Coronaviridae family in the order Nidovirales, and are further subdivided into four genera, the alpha (α), beta (β), gamma (γ) and delta (δ) coronavirus (Fehr and Perlman, 2015). CoVs are minute in size (65–125 nm in diameter) and are single-stranded, positive-sense, non-segmented enveloped RNA viruses (Baker et al., 2011). The surface has various corona- or crown-like spikes, which are helpful to attack and bind living cells, which give them the appearance of a solar corona, prompting the name, coronaviruses. CoVs are host-specific, and can infect a variety of different animals (including camels, bats, pigs, cows, chickens, dogs, and cats) (Fehr and Perlman, 2015), as well as humans, causing several diseases with varying severity (Zumla et al., 2016). In humans, the viruses can cause mild to moderate illnesses, ranging from the common cold to acute respiratory infections (Fehr and Perlman, 2015; Gulati et al., 2020). To date, there are seven known types of human coronaviruses that are common throughout the world: 229 E (alpha coronavirus), NL63 (alpha coronavirus), OC43 (beta coronavirus), HKU1 (beta coronavirus), MERS-CoV (the beta coronavirus causing MERS, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), SARS-CoV (the beta coronavirus causing SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and SARS-CoV-2 (the beta coronavirus causing COVID-19). Although most human coronavirus infections are mild, the epidemics of the two betacoronaviruses, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, have caused more than 8000 and 2000 cases respectively in the past two decades, with high mortality rates of 3.6–15.7% for SARS-CoV and 30–40% for MERS-CoV (Petrosillo et al., 2020). Currently, the coronavirus pandemic SARS-CoV-2, even if it is a less fatality rate (10–15%), has a high transmissibility and can be spread in the community more easily than MERS and SARS-CoV (Huang et al., 2020; Petrosillo et al., 2020).

The current global crisis clearly underlines the critical importance of water management and sanitation within an effective world health system. With regard to the COVID-19 emergency, appropriate water management is essential in the prevention of contagion (WHO, 2020c) and surveillance through monitoring of sewer systems (Mao et al., 2020b), while water itself may represent a potential means of transmission (WHO, 2020d). Consequently, water services, as an indispensable element for human development, welfare and health, play the fundamental role to guarantee safety and quality in drinking water supply as well as in wastewater collection and treatment.

To date, there is no clear evidence regarding SARS-CoV-2 survival in water or sewage (WHO, 2020c). Previous reviews reported the state of the art of CoVs detection, presence and persistence in the water environment (Carducci et al., 2020a; Farkas et al., 2020; La Rosa et al., 2020a). However, an overview on the all components of the water system is missing. This paper reports recent research on the presence and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewaters, water and sludge. The possible implications for the water service in terms of fecal transmission, human exposure, public health and workers risk are discussed. Furthermore, the impacts of containment measures and emergency management on household water consumptions are also analyzed, together with the potential of wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) as a monitoring and early warning tool to be applied in case of infectious disease outbreaks. This review is based on current knowledge on the SARS-CoV-2, focusing on its presence and impacts in water service. Current research information may be useful to support technician and local authorities to evaluate risks inherent to the adequacy of the wastewater collection and treatment systems, the disposal of the generated waste (i.e. sludge, grit, grease, oil) as well as for the development of guidelines in water service management, such as the sanitation safety plans - SSP (WHO, 2016).

2. Review methodology

Studies reported in this paper include research articles, reviews, short communications, editorials, case reports, case series, news and others. More accurately, in order to collect specific information on the SARS-CoV-2 in water service, literature has been searched by combining keywords with the Boolean operators “AND”. The keywords ‘COVID-19’/‘SARS-CoV-2‘ were searched together with ‘water, wastewater, sludge’/‘urban water cycle’/‘water service’/‘fecal/faecal transmission’/‘wastewater-based epidemiology’ in NCBI, Google scholar, Scopus and Science Directdatabases, collecting relevant and latest studies. To give a fairly representative view of the topic, the literature search was extended to preprints using the medRxiv server (https://www.medrxiv.org/).

3. Transmission of the SARS-CoV2

Human viruses can be, in general, transmitted by means of human bodily fluids, such as saliva, mucus, feces, vomits, urine and blood, which can enter in contact with either other people directly, or waters, foods and surfaces until another person comes into contact with them. Concerning COVID-19 disease, various routes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 have been verified, and others hypothesized.

According to current evidence, SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted between people by direct or indirect contact through contaminated respiratory droplets (droplet particles > 5–10 μm in diameter) produced by infected individuals (Chan et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020a; WHO, 2020e). Ren et al. (2020) reported that the most common CoVs may well survive or persist on surfaces for up to one month. Even if data on the transmissibility of CoVs from contaminated surfaces to hands were not found, the WHO recommends to ensure that environmental surface cleaning and disinfection procedures are followed consistently and correctly, mainly using water, detergent and ordinarily used hospital-level disinfectants (such as sodium hypochlorite) (WHO, 2020f). Until now, no SARS-CoV-2 infections transmitted via food have been reported, although it has been demonstrated that, at 4 °C, CoVs may survive up to 2–4 days in fresh food (Yepiz-Gomez et al., 2013).

SARS-CoV-2 can also be transmitted between people through airborne transmission (Carducci et al., 2020b). This refers to the presence of the virus within droplet nuclei, which are generally considered to be particles <5 μm, released during respiration or vocalism (Asadi et al., 2019) or the residual solid component after the evaporation of droplets (Asadi et al., 2020). Contini and Costabile (2020) state that, in order to correctly assess the probability of contagion through such a mechanism, a distinction must be made between indoor environments with limited air exchanges and outdoor environments. However, the effective probability of contagion depends on different factors, including the concentration and the size distribution of virus-laden aerosols in air, the chemical and biological composition of the bioaerosol, the lifetime of the virus, and the minimum amount of viable virus to be inhaled to produce infection.

Finally, a possible fecal transmission of the virus has been hypothesized (Amirian, 2020; Ding and Liang, 2020). The WHO in a technical report has stated that the risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 from the feces of an infected person seems to be low (WHO, 2020c). However, several case studies have reported that some patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 have viral RNA or live infectious virus present in feces (Hindson, 2020). This means that feces may contaminate hands, water, food, etc., and may cause COVID-19 transmission. Moreover, evidence of fecal–aerosol transmission route was reported during the March 2003 outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong (McKinney et al., 2006). The authors demonstrated that the SARS-CoV virus was spread in a large complex of private apartments, due to aerosol diffusion from inadequate wastewater management. Thus, concerning the SARS-CoV-2, even if no cases of fecal transmission have been reported, recent evidence support fecal–oral, fecal–fomite, or fecal–aerosol/droplet trasmission as possible transmission routes of COVID-19 (Amirian, 2020; Xiao et al., 2020). A framework of possible SARS-CoV-2 fecal transmission routes has been shown by Heller et al. (2020), who has hypothesized that starting from feces the three primary routes for the virus may be to water, to surfaces or to places where insect vectors are present. From these environments, through different pathways, viruses may reach the mouth of another individual and infect both the intestinal and the respiratory tracts of another individual. The authors stressed the need for more in-depth research to ascertain those transmission routes.

4. Presence and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, sludge and water environments

The occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 has been showed in stool samples of symptomatic and asymptomatic people (Rampelli et al., 2020) as well as in municipal wastewaters worldwide. Viral RNA fragments of SARS-CoV-2 have been found in the feces of infected patients suggesting that the infectious virions are secreted from the virus-infected gastrointestinal cells (Mao et al., 2020a; Wu et al., 2020a; Zhang et al., 2020a). Further, fecal samples have been shown to remain positive for the SARS-CoV-2 for a significantly longer time compared to upper respiratory samples, from a few hours up to 5 weeks (Wang et al., 2020a; Wu et al., 2020b; Xu et al., 2020). The duration of viral shedding from the feces after negative conversion in pharyngeal swabs may depend on the COVID-19 severity (Chen et al., 2020). Xiao et al. (2020), analyzing the feces of 71 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, confirmed that the viral gastrointestinal infection and potential fecal-oral transmission can last even after viral clearance in the respiratory tract. A study carried out on 41 patients revealed the presence of traces of the SARS-CoV-2 after 5 weeks in the stool of patients who tested negative by pharyngeal swab (Wu et al., 2020b). Another study, carried out on 3 infected children, revealed traces of the virus after 10 days in the feces of the patients who tested negative following a second pharyngeal swab (Zhang et al., 2020a). Similar results were achieved by Chen et al. (2020).

Nevertheless, the detection of viral genetic fragments in feces does not necessarily imply that viable infectious virions are present in fecal material and that the virus can spread through fecal transmission. To date, only one study has isolated the SARS-CoV-2 from stool samples (Zhang et al., 2020b), and few others have observed live viable virus in stool samples (Wang et al., 2020c; Wu et al., 2020b; Xiao et al., 2020). Wu et al. (2020b) observed that for over half of monitored patients, their fecal samples remained positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA for a mean of 11.2 days after respiratory tract samples became negative, implying that the virus is actively replicating in the gastrointestinal tract of patients. Recently, Liu et al. (2020a) experimentally proved that SARS-CoV-2 remaied viable for 2–6 h in adult’s feces and up to 2 days in children’s feces. Concerning urine, up to date, only few conflicting data are reported on SARS-CoV-2 presence. In the study of Wang et al. (2020b), none of the 72 urine specimens tested positive. On the contrary, Peng et al. (2020) reported for the first time a study in which SARS-CoV-2 RNA was identified in the urine of an infected patient. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 was recently detected up to 3 days in two adult urine samples and up to 4 days in one child urine sample (Liu et al., 2020b).

All those evidences clearly indicate that wastewaters may contain both RNA fragments and viable virus. Medema et al. (2020) published the first report of detection of SARS-CoV-2 in raw wastewater in Netherlands in 2020 from March 5to March 16, 2020. After this publication, novel papers have demonstrated the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 in raw wastewaters. Using different detection methods, SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater samples have been found in several cities around the world in 2020, including Milan and Rome, Italy, in the period from February 24 to April 02 (La Rosa et al., 2020b); Massachusetts, USA, in the period from March 18 to March 25 (Wu et al., 2020a); Paris, France, in the period from March 5 to April 23 (Wurtzer et al., 2020); in Brisbane, Australia, in the period from March 26 to April 4 (Ahmed et al., 2020); Region of Murcia, Spain, in the period from March 12 to April 14 (Randazzo et al., 2020); Milan Metropolitan Area, Italy, in the period from April 14 to April 22 (Rimoldi et al., 2020). However, the vitality of SARS-CoV-2 in raw wastewater was not significant, despite the likely high number of RNA copies present in the samples (Rimoldi et al., 2020). Similarly, no infectious SARS-CoV contamination was found in 2003 in any of the wastewater samples collected from two hospitals receiving SARS patients in Beijing (Wang et al., 2005a).

Effluent from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), equipped with both secondary treatments and tertiary disinfection step by peracetic acid or high intensity UV lamps, were mainly found negative for SARS-CoV-2, indicating the effectiveness of wastewater treatments (Rimoldi et al., 2020). The efficacy of tertiary treatments implemented in the WWPT against SARS-CoV-2 has been further confirmed by Randazzo et al. (2020). These results are in accordance with previous research in the literature. Wang et al. (2018) found that conventional WWTPs (i.e., WWTPs based on chlorine disinfection before the final release) proved to be efficient in removal of environmentally persistent non-enveloped viruses, that are more stable of enveloped viruses in the enviroment. Nevertheless, effluents from secondary treatment have been found positive to SARS-CoV-2 (Randazzo et al., 2020). Each stage of wastewater treatment, as well as treatment retention time and dilution effect, results in a consequential reduction of the potential risk. However, to date, little is known about the virus concentrations in WWTPs, the removal rates in treatment sections, and about activity of the genetic materials detected. Specific scientific suggestions for management, technology selection, and operation of hospital wastewater disinfection during COVID-19 pandemic have been provided by Wang et al. (2020a).

The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in sewage sludge is also an issue, but very few studies are available in literature. Ye et al. (2016) reported that up to 26% of the investigated enveloped viruses were adsorbed on the solid fraction of wastewater, that can be removed by sedimentation, suggesting that enveloped viruses may be found in sewage sludge. A metagenomic study identified 10 CoVs sequences, nine of which related to Human CoV-229 E and one to Human CoV-HKU1, in primary and secondary activated sludge, treated by means of mesophilic (35–37 °C) anaerobic digestion and belt pressing (Bibby et al., 2011). Another research reported the presence of the CoVs in sludge both entering and leaving the anaerobic digesters (Bibby and Peccia, 2013). SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been recently detected using qRT-PCR in primary sewage sludge during the COVID-19 outbreak in a northeastern U.S. metropolitan area (Peccia et al., 2020). However, in these studies there are no data relating to virus infectivity, but only the presence of fragments of RNA is reported, and further research studies are required. However, for sludge produced during the COVID-19 pandemic that has not undergone any disinfection treatment, there are not enough data available to be able to define the level of contamination by SARS-CoV-2.

Finally, the presence of CoVs in natural water systems has been experimentally evaluated in a small number of studies, as reviewed by La Rosa et al. (2020a). Blanco et al. (2019) investigated the occurrence of Alpha- and Betacoronavirus in surface waters of Wadi Hanifa, Riyadh, Central Saudi Arabia, using a broad-range RT-PCR. Only one sample out of 21 was positive for Alphacoronavirus. Alexyuk et al. (2017) have detected by means of metagenomic studies Coronaviridae in surface water (river, lake and water reservoir). Recently, Rimoldi et al. (2020) found positive amplification of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in rivers downstream the Milano Metropolitan area, Italy, during the COVID-19 peak disease, probably due to untreated wastewater discharges or sewage overflows. However, virus infectiveness was not significant, indicating the natural decay of viral vitality. The WHO, in its technical report, has stated that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 has not been observed in drinking water supplies and concluded that the risk for water supplies is low (WHO, 2020g). The EPA recommends to continue using and drinking tap water as usual (EPA, 2020a). However, SARS-CoV-2 presence in drinking water remains a major concern for the water sector. In countries with a highly developed water supply system, it is difficult for viruses to overcome the existing stages of filtration and disinfection. On the contrary, in countries where water treatment is not equipped to remove viruses, its presence is unknown.

The molecular structure of CoVs influences the persistence of the virus in water environments. Indeed, CoVs are enveloped viruses characterized by a lipid (bilayer) membrane (Weiss and Navas-Martin, 2005). The lipid membrane makes the CoVs less stable in the environment and more susceptible to soap (Chaudhary et al., 2020), disinfectant and oxidants, such as chlorine (Shirai et al., 2000; Wood and Payne, 1998), as compared to non-enveloped human enteric viruses transmitted by water route (i.e. rotavirus, norovirus, adenoviruses, hepatitis A and E, astrovirus).

As recently reviewed by La Rosa et al. (2020a) the persistence or survival of CoVs in water mostly depends on water types (e.g. tap water/filtered tap water, reagent-grade water, lake water, domestic wastewater, pasteurized wastewater, hospital wastewater), temperature, disinfectant dosage and type, organic matter, presence of antagonist microorganisms as well as light exposure (solar or UV inactivation). However, little has been documented on the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in water and wastewater matrices (Kitajima et al., 2020).

CoVs were inactivated more rapidly in water without solids, which can provide protection for viruses in water (Casanova et al., 2009; Gundy et al., 2009). The persistence of CoVs increases with decreasing temperature (Casanova et al., 2009; Gundy et al., 2009; Ye et al., 2016). Chin et al. (2020) reported that SARS-CoV-2 is highly stable at 4 °C, but it is very sensitive to heat. The virus inactivation time goes from 14 days at 22 °C, to 2 days at 37 °C, to 30 min at 56 °C, and 5 min at 70 °C.

Concerning disinfectants, chlorine rather than chlorine dioxide has been found to be more effective in inactivating the CoVs Wang et al. (2005b). Chin et al. (2020) found that SARS-CoV-2 is extremely stable after 60 min chemical treatment at room temperature and for a wide range of pH values (pH 3–10). On the contrary, the same authors proved that SARS-CoV-2 is sensitive, for a contact time of only 5 min, to traditional cleaning products at room temperature (22 °C), such as ethanol (70%) and chlorine-based products with a concentration of 0.1% of active chlorine. Using hand soap, a minimum 15 min incubation time at room temperature was necessary to inactivate the virus. Ultraviolet light has been also reported to be capable of destroying CoVs (Darnell et al., 2004; Duan et al., 2003; Kariwa et al., 2006). However, up to date SARS-CoV-2 has not yet been specifically tested for its ultraviolet susceptibility in water samples. Finally, antagonist microorganisms in water environments can also influence the persistence of CoVs, increasing the extent of viruses inactivation (Pinon and Vialette, 2018; Rzezutka and Cook, 2004; Ye et al., 2016). A scheme of SARS-CoV-2 detection, viability and lifespan of viability in different section of the water system is depicted in the Supplementary information section (Fig. S1).

5. Potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in water service

Water service can play a critical role during pandemics, preventing or amplifing disease transmission. Currently, it is known that SARS-CoV-2 once expelled from the host, can survive for just a few days in the environment out of living cells (Liu et al., 2020b), but enough to reach other living organisms, and to be transferred from one compartment to another.

According Water Framework Directive (WFD) (European Commission, 2000), water services involve different compartments, and consists of all services connected to the human use of the water resource, from “abstraction, impoundment, storage, treatment and distribution of surface water or groundwater”, to “wastewater collection and treatment facilities, which subsequently discharge into surface water”. An overview of the water services in Europe in relation to the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission is provided in Supplementary Information. When proper prevention measures and adequate treatments are implemented in water management systems SARS-CoV-2, contamination risks are limited.

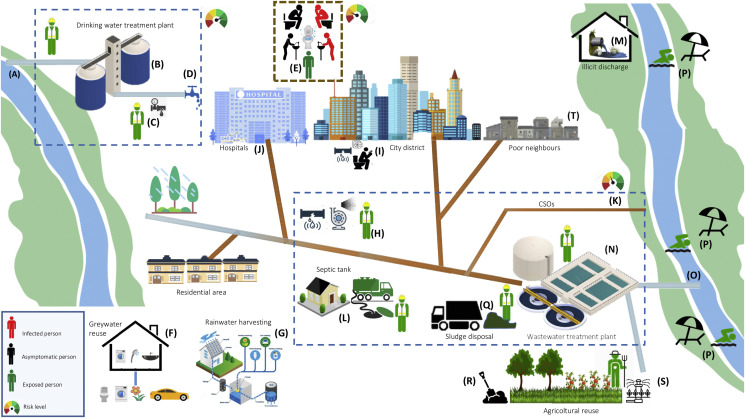

Fig. 1 summarizes the fate of SARS-CoV-2 in water services, highlighting potential routes of contamination. The level of risk rises in cases of inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene management.

-

(A)

Sources of drinking waters (i.e. surface water and groundwater) may contain viruses due to contamination with infected waste and wastewater. This risk is to be taken into account, expecially in cases of illicit wastewater discharges into surface water bodies exploited as sources for drinking water production.

-

(B)

Water withdrawn for municipal potable purposes is treated with a range of physical and chemical treatment processes to remove contaminants including viruses. Potential risks may exist in case of inadequate treatments. Exposure through aerosols or direct contact is limited to professional workers, if not adequately protected by personal protective equipment (PPE).

-

(C)

Drinking water is distributed to final consumers through distribution networks. Possible risks of contamination may exist in case of leaks in underground pipelines and low dynamic pressure in water distribution system.

-

(D)

Drinking water consumers are potentially exposed to viruses, if water treatments are not efficient and the distribution systems have structural weaknesses. However, this risk is very low.

-

(E)

Viruses are excreted in feces, urine, and vomit of symptomatic and asymptomatic infected people. Given the survival time of SARS-CoV-2 RNA nucleic acid-positive, attention should be paid to personal hygiene (e.g. washing, disinfection) and sanitation practices. Particular regard should be given to busy places, such as hospitals, rest homes, shopping centers, offices.

-

(F)

Where greywater reuse is practiced, particular attention should be paid to a potential transmission risk, due to the virus persistence on domestic surfaces (eg. ceramic sink, plastic toilet seat).

-

(G)

Where rainwater reuse is practiced, particular attention should be paid to potential transmission routes, due to the virus persistence in environment and aerosols.

-

(H)

Viruses excreted in feces, urine, and vomit enter into the sewage system. In the municipal sewage system there can be either an airborne transmission, especially in the points where areosols are produced, such as pumping stations, or a contamination of underground drinking water distribution systems, water surface resource, soil, etc. due to leaks in underground sewage pipes. However, exposure through aerosols or direct contact is limited to professional workers, if not adequately protected by personal protective equipment (PPE).

-

(I)

Inside buildings, where water or aeration networks present inadequate systems or operations, risks are to be linked to airborne or direct contact transmission.

-

(J)

The interconnectedness of the wastewater plumbing network in high-risk transmission settings such as hospitals and health-care buildings have to be strictly monitored, as it may facilitate exposure to SARS-CoV-2

-

(K)

Sewage overflow (CSOs) events can lead to the release of infective viruses to surface waters.

-

(L)

Septic tank used in isolated buildings may contain viruses with subsequent risks for purge service operators and any subjects close to the places of operation.

-

(M)

Illicit discharges can cause potentially contaminated wastewaters to flow directly into the receiving water body, impacting drinking waters and bathing waters.

-

(N)

Wastewaters are transported to WWTPs to be treated before the final discharge into the environment. The adopted treatments must to be able to reduce virus levels and activity. Infective human viruses have been detected in WWTP streams mainly before disinfection treatment. Plant operators may be exposed to infective viruses in the case of contacts with raw wastewater, primary and secondary effluents as well as sewage sludge. Workers are adequately protected wearing personal protective equipment (PPE).

-

(O)

Inadequate wastewater treatments can result in viruses discharge into surface waters impacting drinking waters and bathing waters.

-

(P)

Illicit discharges, CSOs and WWTP effluents would possibly impact recreational activities, such as bathing.

-

(Q)

Residual biosolids from WWTP are disposed, often via land-application, composting, incineration, landfill. Workers in close contact with residual biosolids may be exposed to infective viruses, that have survived the solids treatment.

-

(R)

Particular attention must be paid to municipal sludge reuse in agriculture and agronomic spreading of livestock effluents.

-

(S)

Particular cautions should be paid to treated wastewaters reuse practices.

-

(T)

In order to limit the risk of virus spreadings, attention has to be paid to communities with poor quality residential water infrastructure.

Fig. 1.

Potential fate of SARS-CoV-2 in the water service and locations of potential human exposure. Adapted from Wigginton et al. (2015).

6. Roadmap

In this study, a roadmap for a safe management of water services during pandemics has been developed, analyzing the drinking-water supply, the fecal, wastewater and sludge management.

6.1. Safety of drinking-water supply

Ensuring the safety of drinking-water supplies is based on multiple barriers, from catchment to consumer. The first step to prevent drinking water contamination is the adequate protection of water reservoirs. In order to achieve this objective, it is mandatory to prevent surface and underground waters from coming into contact with fecal material, especially human feces, which represents one of the main source of potential SARS-CoV-2 contamination. Surface waters are more susceptible to CoVs contamination than groundwater, because the latter benefits from the pathogens removal due to soil filtration, adsorption on sediment grains and progressive inactivation, which increases with the time necessary to reach the aquifer. Nevertheless, viruses in surface waters are exposed to several potentially inactivating stressors, including sunlight, oxidative chemicals, and predation by microorganisms. The protection of water reservoirs also depends on adequate wastewater treatments.

Further, to ensure greater safety, an adequate drinking water treatment is required. Conventional centralized water treatment plants, employing filtration and disinfection, appear to be sufficient to inactivate the SARS-CoV-2 (WHO, 2020c). Research on other human CoVs and on different and more persistent viruses has shown high sensitivity of viruses to chlorination as well as to ultraviolet (UV) light disinfection (University of California - Santa Barbara, 2020). Recently, plasma discharge technology has been proposed for removing CoVs (Ghernaout and Elboughdiri, 2020). However, in order to guarantee the safety of drinking water supply during and after a lockdown, disinfection performance must be continuously monitored (i.e., turbidity, disinfectant dose, residual, pH, temperature, and flow). For an effective centralized disinfection with chlorine, the residual concentration of free chlorine should be more than 0.5 mg/L after at least 30 min of contact time at pH < 8.0. A chlorine residue must be maintained throughout the distribution system.

Researches on the efficacy of emerging disinfection technologies for CoVs inactivation, especially treatment steps that are integrated into drinking water reuse, including UV-based advanced oxidation processes (UV/AOPs) and ozone/biologically activated carbon (O3/BAC), are needed (Naddeo and Liu, 2020). Moreover, legislation and guidelines for virus removal in drinking reuse systems need to be reviewed taking into account pandemic events.

In order to prevent any recontamination of the treated water, it is necessary (i) to avoid leaks in the drinking water networks and drops in pressure in the pipes, in order to prevent pontentially contaminated water from other sources from entering; (ii) to ensure a safe and clean storage of drinking water, if it is to be conserved. Further, a better understanding of the role of bacterial colonies and biofilm in drinking waters networks in hosting viruses and affecting their viral stability is required.

In places where centralized water treatment are absent and drinking water supplies are not available, protection measures and regular maintenance of wells and septic tanks are recommended. Domestic water treatment can be used as an additional defense measure, particularly in the periods following intense rains, which increase the risk of possible wells contamination. Various domestic treatment technologies are recommended, effective in the removal or inactivation of viruses, including boiling water, or the use of membrane filtration of suitable molecular cutting, solar radiation and, in absence of water turbidity, or after adequate solid removal, UV radiation and appropriately dosed free chlorine (WHO, 2020).

By following these precautions and considering the characteristics of the virus, it is highly unlikely that drinking water could turn into a transmission vehicle for SARS-CoV-2, which in fact has never been detected in drinking water to date. Based on the current evidence, the risk to water supplies is low in countries with high-quality residential water infrastructure (EPA, 2020b).

Attention should be paid also to water supply in buildings that have been closed for weeks or months during lockdowns, where stagnant water can be accumulate inside building plumbing, increasing the risk of pathogens transmission. This water can become unsafe to drink or otherwise use for domestic or commercial purposes. Actions to minimize water stagnation during closures should be adepted by building owners and managers to guarantee building water quality prior to reopening.

6.2. Management of fecal material and wastewater

As far as wastewater is concerned, correct management of wastewaters must necessarily start from the collection. Wastewaters from hospitals and isolation centers treating SARS-CoV-2 patients as well as domestic sewage from areas of contamination may have elevated concentrations of viruses, and require particolar attention. Nevertheless, a recent study confirmed the low risk of contamination, when wastewater is adequately managed (Rimoldi et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, regards must be paid to preventing leaks from sewage systems, in order to avoid human exposure to pathogens and to prevent the contamination of surface and underground water reservoirs. Another potential risk of viral contamination of receiving waters is related to the discharge of combined sewage owerflows (CSOs) during heavy meteoric events, as untreated wastewaters are disharged together with rainwaters into natural environment (Hata et al., 2014; Rijal and Gerba, 2012). Risk of viral contamination can be further reduced preventing illegal sewage discharge. Indeed, as consequence of untreated discharges, or CSOs, some samples from receiving rivers showed a positivity to PCR amplification, even if the virus vitality was negligible, which implies to the absence of sanitary risks (Rimoldi et al., 2020). However, additional research is required to provide reassurance of low risk related to raw wastewater contamination.

Conventional centralized WWTPs are able to ensure an adequate level of protection (WHO, 2020c). Different treatment steps contribute to the removal or inactivation of viruses (Anastasi et al., 2008; Qiu et al., 2015), starting from primary sedimentation, which allows to separate the virus portion associated with the suspended solids. Among the biological treatment processes, the conventional secondary activated sludge treatment ensures a significant removals of pathogens due to the combined effect of the wastewater aeration, the biological activity of biomass and the secondary sedimentation. The residence time in the treatment tanks and the exposure to sunlight, although limited to the layers closest to the surface, can also contribute to viruses inactivation. Finally, an essential role is played by the final disinfection, which represent a further barrier to a potential viral contamination. Rimoldi et al. (2020) proved the effectiveness of WWTPs based on secondary treatments followed by disinfection. Nevertheless, disinfection is not always included in WWTPs, depending on Population Equivalent (PE). Thus, as SARS-CoV-2 is particularly susceptible to disinfection, in order to prevent virus contamination, it could be reasonable to include a disinfection treatment in all WWTPs, and for small WWTPs activate it only during epidemic episodes. China has asked WWTPs to strengthen their disinfection routines (mainly through increased use of chlorine) to prevent the new CoVs from spreading through wastewaters. Nevertheless, potential ecological impact of disinfection by-products present in chlorinated wastewater effluents has to be taken into account, and research on environmental friendly disinfection treatments to remove viruses should be carried out.

Even if potential infection risk due to accidental contacts with wastewaters (e.g., airborne aerosols and droplets) seems to be negligible, WHO highlights the need to adopt best practices for the protection of workers’ health in wastewater treatment facilities, such as pumping out tanks or unloading pumper trucks (WHO, 2020c). All workers should wear adequate PPE, including protective clothing, gloves, boots, protective glasses, or a visor and a mask. They should frequently perform hand hygiene and they should avoid touching eyes, nose, mouth and food with unwashed hands.

Finally, in order to minimizing health and hygiene risks related to wastewater reuse mainly in agricolture, a deeper knowledge on SARS-CoV-2 viability in reused water is needed. Wastewaters from health facilities should never be reused, or released on land that is used for production of food, or disposed of in recreational waters (WHO, 2020c).

6.3. Sludge management

Sewage sludge deriving from primary sedimentation (primary sludge), secondary sedimentation after biological treatment (secondary sludge) and clariflocculation (chemical sludge) are biologically unstable materials that have to be treated to reduce the content of biodegradable organic substances, the water content as well as the microbial and pathogenic load. Fragments of SARS-COV-2 genetic material has been detected in primary sewage sludge, but no data are available on its viability (Peccia et al., 2020). Usual treatments of sludge performed in the WWTPs are not always effective in reducing numbers of pathogens, and, depending on the sludge disposal method, further treatments are required.

Common disposal methods of sewage sludge from WWTPs in EU in 2017 include incineration (18%), landfilling (13%), agricultural use (23%), composting (19%) and others (long-term storage and land reclamation) (Eurostat, 2020). Each of them carry different risks of contaminating food, water, and eventually lead to viral infection of humans. Among them, agricultural use, in the form of spreading on the land, is one of the principal means by which sludge is disposed of. Agricultural use of sludge is only allowed if the sludge has undergone treatment by biological, chemical, thermal, or other suitable processes to diminish its capacity for fermentation and eliminate any human health risk related to such use. Usually treatments such as thermophilic (aerobic or anaerobic) digestion, pasteurization, stabilization treatment with lime, sulfuric acid, ammonia, soda or a combination of these, thermal drying, thermal hydrolysis, composting and lagooning are particularly effective for inactivating infected viral material (European Commission, 2001; ISS, 2020a). Therefore, the risk of transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 infection by means sludge spreading on the land may be considered irrelevant, if the sludge is properly treated. On the contrary attention should be paid in case of illegal disposal of untreated sludge, as it may pose risks related to direct human exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and to groundwater, or superficial water bodies contamination. Risks related to the sludge disposal in controlled landfills may be considered irrelevant, if the sludge is properly managed, while its disposal in uncontrolled landfills may carry some risks of contamination of groundwater by virus in the leachate.

However, adeguate PPEs should be worn by workers at all times when handling or transporting sludge offsite, and a great care should be taken to avoid release of areosol and droplets.

7. SARS-CoV-2 surveillance through wastewater monitoring

As SARS-CoV-2 is detectable in stool in up to half of COVID-19 patients (Xie et al., 2020) as well as in stool of asymptomatics (Rampelli et al., 2020) and the feces remain positive for as much as five weeks (Wu et al., 2020b), wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) has been proposed as an efficient, economical and powerful tool for assessing, monitoring and managing the pandemic (Hart and Halden, 2020). Various research groups in the Netherlands (Medema et al., 2020), France (Wurtzer et al., 2020), Italy (Rimoldi et al., 2020), Swizerland (EPFL, 2020), Australia (Ahmed et al., 2020), United States (Holshue et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a) and elsewhere have independently reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewaters, trying to correlate its concentration to the level of infection in the population (Mallapaty, 2020). Wastewater monitoring may be used to identify COVID-19 hotspots, tracking and providing early warnings of outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 (Mao et al., 2020b).

WBE surveillance of populations is cheaper and faster than clinical screening. However, challenges include the development and standardization of analytical methods and statistically representative sampling of sewage (Daughton, 2020a).

A wide range of analytical methods is available for infectious human enteric viruses detection in environmental water samples (Ahmed et al., 2011). SARS-CoV-2 in urban wastewater has been mainly detected by direct measures of viral RNA using RT-qPCR and nested RT-PCR (Ahmed et al., 2020; Medema et al., 2020; Rimoldi et al., 2020). Both qualitative RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR have been used. However, Hal et al. (2020) underlined that precautions are needed when interpreting the Ct values of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR in order to avoid misunderstanding of viral load kinetics, comparing different studies. A detailed review on PCR-based methods for SARS-CoV-2 detection in wastewater has been published by Kitajima et al. (2020). As RT-PCR is laborious and costly, other methods are currently being investigated (Orive et al., 2020). Even if not as sensitive as PCR, antigen test (e.g., capsid proteins) is emerging for rapid detection of the SARS-CoV-2 (US FDA, 2020). In future, WBE’s usefulness could be greatly expanded by targeting indirect markers of infection (e.g., by use of immunoassays (Xiang et al., 2020), pharmaceuticals used in the treatment of COVID-19), reducing analytical costs and increasing availability, or serving as better indicators of infection (Daughton, 2020b). Researchers from the University of Cranfield, England, are working on a new paper-based test to detect SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater from virus-infected communities (Mao et al., 2020a). Furthermore, as recently reviewed by Kitajima et al. (2020), a virus concentration step prior to subsequent detection of SARS-CoV-2 is necessary to increase the chance of detection of the virus in water samples, and numerous types of methods have been used for concentrating SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, such as ultrafiltration, PEG precipitation, and electronegative membrane adsorption followed by direct RNA extraction (Ahmed et al., 2020; Medema et al., 2020; Nemudryi et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a; Wurtzer et al., 2020). The initial research studies reporting molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater concentrated up to 200 mL of raw wastewater samples, but larger volumes of wastewater sample may need to be processed in areas where COVID-19 is less widespread. Meanwhile sensitivity and specificity of analytical techniques are developing, wastewater samples should be regularly collected and frozen for future validation of methods as well as reconstruction of the temporal trends of the infection (Murakami et al., 2020).

A careful selection of representative sample points along a sewer network en route to a WWTP is a crucial step, including the detection of pressure points in clear geographical wastewater catchments, such as quarantine facilities, hospitals, or local government area, etc. Furthermore, sampling of latrines into health surveillance should be integrated (Hart and Halden, 2020). Generally, the WWTP serves as a main sampling point, but wastewater sampling can be done at different points of the sewage pathway, in order to detect COVID-19 hotspots. Appropriate sampling campaigns may address spatio-temporal trends, and may be useful to detect real time deviations from the general trend as early as possible, providing useful information for public health policy (Mao et al., 2020b; Nghiem et al., 2020).

Recently, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 have been found in primary sludge, that may be advantageous for monitoring SARS-CoV-2 as it is a well mixed and significatively more concentrated sample than wastewaters (Peccia et al., 2020). The virus RNA concentrations were highly correlated with the COVID-19 epidemiological curve and local hospital admissions. This would imply the importance and the development of a raw wastewater and sludge-based epidemiology surveillance approach.

Given the high cost of COVID-19-related lockdowns (Nuno, 2020), having information available in real-time to inform decision makers would have substantial economic value. The challenge, thus, is to design a widely-accepted surveillance system to detect the potential community presence of COVID-19, in order to collect data to support politician decision-making processes (Sims and Kasprzyk-Hordern, 2020), helping both to define COVID-19 reopening plants and to prevent SARS-CoV-2 re-emergence (Fig. 2 ). Data from massive virus surveillance from sewers can be coupled with health and socio-economic data under an unique National Digital Epidemic Observatory, by using Machine Learning to link various data sources and optimize early warning and mitigation measures. WBE’s limitation related to the identification of infected individuals and their specific locations can be overcome by suitable sampling campaigns, that can allow to implement a first step of an effective surveillance to identify infected areas, followed by a second step of clinical testing to identify infected individuals in WBE-revealed hotspots (Hart and Halden, 2020).

Fig. 2.

Water based epidemiologic approach. Adapted from Randazzo et al. (2020).

Governments worldwide and National agencies should encourage the implemetation of WBE. European Commission’s Joint Research Centre and the Directorate-General for Environment have issued a call for participation in European Action to investigate the development of the WBE approach for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance, exchanging experiences among utilities, research centers, universities, governments (European Commission, 2020). Up to date, numerous european stakeholders (international, national, regional and local activities) are working in parallel, with different designs and approaches, collaborating to solve challenges related to sampling, analytical methodology, interaction with health services and epidemiologists, data hosting and decision support, and knowledge transfer and international exchange.

8. Impacts on the water sector and the environment

The severity of the COVID-19 pandemic has forced almost all world countries to observe extraordinary measures to tackle the exponential virus spread. Waiting for a specific vaccine, the first measures adopted were those aimed at limiting the contagion phase through social distancing, closure of educational centers, restriction of social activities and public life, lockdown of many commercial and work activities or, where possible, their remodulation with new tools such as home working as well as the recommendation to take special hygienic and sanitary measures, focused on handwashing, cleaning and disinfecting to prevent COVID-19.

These measures heavily impact on our behavior. Indeed, after many States around the world had issued lockdown orders, a very high percentage of people has been forced to stay the whole day at home, with consequences for the entire water sector, starting from drinking water consumption in homes to the quality and quantity of municipal wastewater. The possible effects on WWTPs, on water bodies, on public health and on operators in the sector are to be assessed. The consequences on water sector are further compounded by the adopted cleaning and disinfection measures of external environmental surfaces (i.e. streets, urban pavements) and environments in healthcare and nonhealthcare settings (ECDC, 2020).

If it is plausible that the measures to combat the COVID-19 pandemic lead to inevitable increases in water consumption on the domestic side, it is also, on the contrary, to be considered that during the lockdown the forced arrest of countless industrial water-intensive activities induces a strong reduction. Obviously the overall effects on the national water systems are difficult to quantify and can only be verified with the collection of real consumption data generated in the period, with the support of water utilities around the world. However, trying to quantify the changes in consumption at the domestic level can be an indication of the impact on families and, through greater awareness, cause a better approach in the use of water resources.

8.1. Household water consumptions

Among the measures for COVID-19 epidemiological emergency, containment and management there are, as mentioned, measures that limit the movement, impose social restrictions and require home quarantine of infected, or potentially infected subjects. In addition, sanitary prevention measures include the following recommendations: washing often hands with soap and water, or with a hydroalcoholic solution; clean the surfaces with chlorine or alcohol based disinfectants; in the case of infected patients, washing clothes, sheets, towels in the washing machine at 60–90 °C, as well as using disposable paper towels (WHO, 2020c, 2020g).

The confinement in houses, together with the greater demand for sanitation, has a possible significant impact on household water consumption. A rough estimation of the increase in water consumption associated with a greater presence of the residents at home has been made from data collected as part of an our European project on rational use and re-use of water in residential buildings (ENEA, 2001). After the realization of the project, in the period 2012–2014, a 3-years of water consumption monitoring has been carried out on an entire building consisting of 8 apartments in Italy. Results showed that water consumption had a 3–4 fold increase depending on different behavioral modalities. The highest values of water consumption have been recorded for older people as compared to younger people (about 200 and 55 L/day/person for an average age of the residents of 60 and 25 years old, respectively) (Fig. S2). This result has been related to the fact that elderly people spend much more time in their homes during the day since they do not have work and/or school needs. Based on this result, it can be hypothesized that the continuous presence in the house induced by the lockdown can lead to increase more than three times water consumption in those families who normally live most of the day outside the home.

This estimation is further supported by a simple calculation of the increase of the average water consumption per capita in buildings, calculated as consequence of recommendations to increase handwashing frequency. Considering 12 additional daily washes and 40 s each washing operation, handwashing practice will result in an extra daily water consumption of about 25–96 L/day/person, depending on tap type (e.g. aerators, starndard, flow reducer) and water saving measures (see Supplemental Information and Table S1). Even higher consumption must be expected if handwashing is performed by means of hot water, because in this case more water is generally wasted, waiting to reach the desired temperature. The use of warm water (about 40 °C) is common both to reduce virus and bacteria during handwashing and to increase comfort during the operation (Sickbert-Bennett et al., 2005). However, some studies have highlighted how cleaning efficiency is closely linked to the quality of the soaps used and the prudence and obstinacy with which hands are scrubbed, rather than the water temperature (Laestadius and Dimberg, 2005; Michaels, 2001; Michaels et al., 2002). Furthermore, a higher domestic water consumption should also be linked to the higher frequency of laundry washing and dishwashing, which are two everyday household activities that, in normal conditions, account for approximately 20% of the household water consumption (Schleich and Hillenbrand, 2009).

Changes in daily water consumption patterns have been also observed, due to the closure of schools and non-essential activities and the increase in home-working. Data on daily water consumption profile in a German city have been published by a water utility (WatEner, 2020). Under normal situation (March 3, 2020, before COVID-19 measures) the demand peak occurred at around 7.10 a.m., when schools and activities open, causing a sharp increase of water consumption, while after the restriction measures were adopted (March 24, 2020), the demand peak was delayed of approximately 2 h. Furthermore, before lockdown, water consumption was minimum after 8:00–8:30 until late afternoon (16:00–17:00), while during the quarantine period, water consumption was distributed more gradually in the morning, reducing slowly until the afternoon. Moreover, data showed that between 17:00 and midnight, there were no significant differences in consumption before and after the containment measures, indicating that consumers behavior was not altered during this time.

In order to limit, as much as possible, the impact in terms of greater domestic water consumption, due to the ongoing health emergency, it is important, while following hygienic recommendations, to limit the use of water as much as possible, in order to avoid excessive stress of the drinking water distribution system and wastewater management system. In this regard, it should be considered that in public places only taps with pedal or automatic start&stop and dispensers with photocell should be installed, which can save water and have the ulterior sanitary advantage of not requiring direct contact with hands. This aspect shoud be taken into account expecially in areas where drought occurs.

Graywater recovery technologies (i.e. water deriving from the drains of showers, washbasins etc.) should normally be encouraged, as they could allow drinking water savings for those uses where it is not strictly necessary. Nevertheless, some critical aspects should be kept in mind in the case of graywater reuse during sanitary emergency conditions, like those occurred with the COVID-19 pandemic. Graywater recovery systems usually undergoes a 3- to 4-stage treatment based on separation and disinfection processes, whose effectiveness against the virus is to be verify. For a correct risk assessment, it would be necessary to carry out additional research. Minor critical issues are instead conceivable in the case of using rainwater recovery systems, once a check on the actual residence times of the virus on the external surfaces have been established.

8.2. Wastewater quality and the environment

The recommendations provided to deal with the emergency of the COVID-19 epidemic may also have an impact on the quality of wastewaters, the environment, and eventually may compromise the quality of drinking water. This aspect is mainly related to the cleaning and disinfection operations of surfaces of indoor and outdoor environmets. Several studies have evaluated the persistence of the SARS-CoV-2 on different surfaces (Chin et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020b; Van Doremalen et al., 2020), and its susceptibility to heat and standard disinfection (Chin et al., 2020) and cleaning (Chaudhary et al., 2020) methods. Thus, surfaces and areas potentially contaminated by SARS-CoV-2 have to be cleaned with water, detergents and disinfectants with proven effectiveness on coronaviruses removal. Recently, considerations for the cleaning and disinfection of surfaces and areas in the context of COVID-19 in both health care and non-health care settings has been published by WHO (WHO, 2020h).

The cleaning actions by means of soap use (handwashing, surfaces cleaning) help to remove pathogens or significantly reduce their load on contaminated surfaces and are an indispensable step in any disinfection process. The efficacy of cleaning actions of soap is attributed mainly to the presence of surfactants. Soaps are amphiphilic molecules which interact with both hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances. Their effectiveness is attributed to low surface tension, basic nature, amphiphilic orientation, and the ability to form a micelle. The lipid envelope of the SARS-CoV-2 is susceptible to soap. Chaudhary et al. (2020) recently clarified the cleaning mechanisms of surfactants in relation to coronavirus, they may act either by destroying the lipid membrane of the virus, or by trapping the viral particle within the micelle, or by adsorbing soap monomers on the viral surface, charging and stabilizing them. Additionally, high temperatures (60–90 °C) could also be used, alone or in combination with soaps, for disinfection of contaminated fomites. Thus, a possible variation in the composition of municipal wastewaters in terms of a higher concentration of surfactants may be hypotized, and the effects on the environment and processes in WWTPs should be evaluated (Arvind and Kumar, 2008; Freeling et al., 2019; Palmer and Hatley, 2018).

Disinfection, moreover, is performed mainly by using several disinfectants. In a recent review it was shown that some disinfectant agents effectively reduce coronavirus infectivity within 1 min, such as 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, chlorine based products (e.g. 0.1% sodium hypochlorite) or 62–71% ethanol (Kampf, 2020). Other compounds such as 0.05–0.2% benzalkonium chloride or 0.02% chlorhexidine digluconate are less effective. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has published an expanded list of EPA-registered disinfectant products against SARS-CoV-2. The list contains nearly 200 products that have not been tested specifically on SARS-CoV-2, but they are expected to be effective because they have been tested and proven efficient on either a harder-to-kill virus, or another human coronavirus (EPA, 2020c). However, the selection of disinfectants should take into account toxicity and impacts on environmental and human health. Spraying or fogging of formaldehyde and chlorinebased or quaternary ammonium compounds, is not recommended due to negative health effects on workers in facilities where these products have been previously utilized (Schyllert et al., 2016). The use of hypochlorite-based products, including sodium hypochlorite (liquid) and calcium hypochlorite (powdered or solid), should be carried out carefully. Hypochlorite-based products are, indeed, dangerous substances, and are responsible for cause serious skin burns, eye injuries and respiratory irritation. They are also very toxic to the aquatic environment, both in the short and long term (APA, 2020). Moreover, these substances, in the presence of organic materials present on surfaces, could also give rise to the formation of extremely dangerous by-products, such as chloramines and trihalomethanes and other volatile carcinogenic substances and dangerous non-volatile by-products (WHO, 2004).

Besides touchable surfaces in indoor environments, in order to protect the public health, some governments have addressed the issue related to the cleaning and disinfection of outdoor spaces and road surfaces, spraying disinfectant on the streets and in marketplaces. Nevertheless, outdoor spaces disinfection is not recommended by WHO to kill the SARS-CoV-2, because it does not eliminate the virus, mainly due to the fact that disinfectants are inactivated by dirt and debris and the adequate contact time to inactivate pathogens is not guaranteed (WHO, 2020h). This practice even poses a human health (Benzoni and Hatcher, 2020; Mehtar et al., 2016) and environmental pollution risk. Some countries underline the opportunity to wash street and urban pavements by ordinary cleaning methods, i.e. by means of water and conventional detergents – avoiding the production of dust and aerosols, and to limit disinfection with products such as sodium hypochlorite to exceptional interventions and on limited areas (ISS, 2020b). Sodium hypochlorite may affect the quality of surface water as well as the quality of groundwater if it reaches these areas. Finally, another aspect to take into account in sewage and WWTPs management is the overload of the sewage system due to a possible greater presence of disinfectant wipes, toilet paper and other similar products that may have been mistakenly thrown into the toilet due to COVID-19 emergency. All these aspects should be investigated in collaboration with water utilities who provide both water and sanitation services.

9. Conclusions

Many research studies have been carried out during SAR-CoV-2 pandemic, each with its own contribution in terms of understanding and defining the potential role of the water services in the spread of the virus. A roadmap for a safe management of water services has been developed in this study. According to the evidences highlighted in the present paper, it is possibile to identify a series of key aspects and recommendations that are worth being taken into consideration and to be extended and improved in order to further progress with the status of knwoledge related to SAR-CoV-2 pandemic:

-

•

Access to safe drinking water and sanitation services, especially for vulnerable communities, has to be improved and guaranteed.

-

•

Water distibution systems and wastewater collection infrastructures have to be optimized, reducing pipe leaks, CSOs, illicit discharges.

-

•

Methods for SARS-CoV-2 detection (concentrating, extracting and purifying) from complex sample matrices such as wastewater, residual biosolids, and surface water need to be optimized and standardized.

-

•

Further research activities regarding the viability, infectivity and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in feces, urine, raw wastewater, and sludge, are required.

-

•

Water and wastewater treatment plants should be managed an operated try to prevent possible risks.

-

•

In order to have a systematic approach in pandemic surveillance, the water sector should work in coordination with local health authorities and other relevant bodies.

-

•

The “sewage epidemiology approach” should be considered together with the “wastewater epidemiology approach”, and coupled with health and socioeconomic data, as a first step of an effective surveillance to identify infected areas, followed by a second step of clinical testing to identify infected individuals in WBE-revealed hotspots.

-

•

Quantitative risk assessments should be conducted for SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, recreational water utilities and drinking waters.

Such research issues are also critical in order to increase the public awareness and technical knowledge and to set-up sustainable water services management in the event of a SARS-CoV-2 re-emergence, as well as of future deadly outbreaks or pandemics.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

This paper has been recommended for acceptance by Dr. Sarah Harmon.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115806.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ahmed I., Jurzik L., Überla K., Wilhelm M. Methods to detect infectious human enteric viruses in environmental water samples. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2011;214:424–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., Brien J.W.O., Choi P.M., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Li J., Tscharke B., Verhagen R., Smith W.J.M., Zaugg J., Dierens L., Hugenholtz P., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID- 19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138764. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexyuk M.S., Turmagambetova A.S., Alexyuk P.G., Bogoyavlenskiy A.P., Berezin V.E. Comparative study of viromes from freshwater samples of the Ile-Balkhash region of Kazakhstan captured through metagenomic analysis. Virus Dis. 2017;28:18–25. doi: 10.1007/s13337-016-0353-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirian E.S. Potential fecal transmission of SARS-CoV-2: current evidence and implications for public health. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;95:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasi P., Bonanni E., Cecchini G., Divizia M., Donia D., Di Gianfilippo F., Gabrieli R., Petrinca A.R., Zanobini A. [Virus removal in conventional wastewater treatment process] in Italiano. Ig. Sanita Pubblica. 2008;64:313–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA . 2020. National Center for Biotechnology Information (2020). PubChem Compound Summary for CID 23665760, Sodium Hypochlorite. [WWW Document]. Retrieved Oct. 2, 2020 from https//pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Sodium-hypochlorite. [Google Scholar]

- Arvind K.M., Kumar P. Occurrence of anionic surfactants in treated sewage: risk assessment to aquatic environment. J. Hazard Mater. 2008;160:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadi S., Bouvier N., Wexler A.S., Ristenpart W.D. The coronavirus pandemic and aerosols: does COVID-19 transmit via expiratory particles? Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2020;54:635–638. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2020.1749229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadi S., Wexler A.S., Cappa C.D., Barreda S., Bouvier N.M., Ristenpart W.D. Aerosol emission and superemission during human speech increase with voice loudness. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38808-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S., Nicklin J., Griffiths C. fourth ed. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. BIOS Instant Notes in Microbiology. [Google Scholar]

- Benzoni T., Hatcher J. 2020. Bleach Toxicity.www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441921 [Updated 2020 Jun 29]. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Isl. StatPearls Publ. 2020 Jan-. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibby K., Peccia J. Identification of viral pathogen diversity in sewage sludge by metagenome analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:1945–1951. doi: 10.1021/es305181x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibby K., Viau E., Peccia J. Viral metagenome analysis to guide human pathogen monitoring in environmental samples. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2011:386–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco A., Abid I., Al-Otaibi N., Pérez-Rodríguez F.J., Fuentes C., Guix S., Pintó R.M., Bosch A. Glass wool concentration optimization for the detection of enveloped and non-enveloped waterborne viruses. Food Environ. Virol. 2019;11:184–192. doi: 10.1007/s12560-019-09378-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carducci A., Federigi I., Liu D., Thompson J.R., Verani M. Making Waves: coronavirus detection, presence and persistence in the water environment: state of the art and knowledge needs for public health. Water Res. 2020;179:115907. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carducci A., Federigi I., Verani M. Covid-19 airborne transmission and its prevention: waiting for evidence or applying the precautionary principle? Atmosphere. 2020;11:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova L., Rutala W.A., Weber D.J., Sobsey M.D. Survival of surrogate coronaviruses in water. Water Res. 2009;43:1893–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K., To K.K., Chu H., Yang J., Xing F., Liu J., Yip C.C., Poon R.W., Tsoi H., Lo S.K., Chan K., Poon V.K., Chan W., Ip J.D., Cai J.-P., Cheng V.C.-C., Chen H., Hui C.K.-M., Yuen K.-Y. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission : a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary N.K., Chaudhary N., Dahal M., Guragain B., Rai S., Chaudhary R., Sachin K., Lamichhane-Khadka R., Bhattarai A. Fighting the SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic with soap. Prepr. 2020:1–19. doi: 10.20944/preprints202005.0060.v1. 2020, 2020050060 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Chen L., Deng Q., Zhang G., Wu K., Ni L., Yang Y., Liu B., Wang W., Wei C., Yang J., Ye G., Cheng Z. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A.W.H., Chu J.T.S., Perera M.R.A., Hui K.P.Y., Yen H., Chan M.C.W., Peiris M., Poon L.L.M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. The Lancet Microbe. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contini D., Costabile F. Does air pollution influence COVID-19 outbreaks? Atmos. 2020;11:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Darnell M.E.R., Subbarao K., Feinstone S.M., Taylor D.R. Inactivation of the coronavirus that induces severe acute respiratory syndrome. SARS-CoV. J. ofVirological Methods. 2004;121:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton C. The international imperative to rapidly and inexpensively monitor community-wide Covid-19 infection status and trends. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;726:10–11. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton C.G. Wastewater surveillance for population-wide Covid-19: the present and future. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S., Liang T.J. Is SARS-CoV-2 also an enteric pathogen with potential fecal–oral transmission? A COVID-19 virological and clinical review. Gastroenterology. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan S.-M., Zhao X.-S., Wen R.-F., Huang J.-J., Pi G.-H., Zhang S.-X., Han J., Bi S.-L., Ruan L., Dong X.-P. Stability of SARS coronavirus in human specimens and environment and its sensitivity to heating and UV irradiation. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2003:246–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECDC . 2020. Disinfection of Environments in Healthcare and Non- Healthcare Settings Potentially Contaminated with COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- ENEA . LIFE97ENVIRONEMET/IT/000106; 2001. Experimental Aquasave Project in Households - Tecnologies and Results. [Google Scholar]

- EPA . 2020. Is Drinking Tap Water Safe?https://www.epa.gov/coronavirus/drinking-tap-water-safe [WWW Document]. Coronavirus Inf. from EPA. [Google Scholar]

- EPA . 2020. Coronavirus and Drinking Water and Wastewater. [Google Scholar]

- EPA . 2020. List N: Disinfectants for Use against SARS-CoV-2.https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2 [WWW Document]. Pestic. Regist. [Google Scholar]

- EPFL . Sci. Bus; 2020. EPFL Researchers Developed a Method for Detecting COVID-19 in Wastewater Samples. [30 April 2020] [WWW Document] [Google Scholar]

- European_Commission . 2000. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy.https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32000L0060 [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . 2020. CALL NOTICE Feasibility Assessment for an EU-wide Wastewater Monitoring System for SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance.https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/science-update/call-notice-feasibility-assessment-eu-wide-wastewater-monitoring-system-sars-cov-2-surveillance [WWW Document]. EU Sci. HUB. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . 2001. Evaluation of Sludge Treatments for Pathogen Reduction. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat . 2020. Eurostat Database. [WWW Document]. Sew. sludge Prod. Dispos. [website accessed May 16th, 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas K., Hillary L.S., Malham S.K., Mcdonald J.E., Jones D.L. Wastewater and public health: the potential of wastewater surveillance for monitoring COVID-19. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Heal. 2020;17:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr A.R., Perlman S. Methods in Molecular Biology. Clifton, N.J.; 2015. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis; pp. 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeling F., Alygizakis von der Ohe P., Slobodnik J., Oswald P., Aalizadeh R., Cirka L., Thomaidis N.S., Scheurer M. Occurrence and potential environmental risk of surfactants and their transformation products discharged by wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 681, Sci. Total Environ. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghernaout D., Elboughdiri N. Disinfecting water: plasma discharge for removing coronaviruses. Open Access Libr. J. 2020;7 doi: 10.4236/oalib.1106314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbalenya A.E., Baker S.C., Baric R.S., de Groot R.J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A.A., Haagmans B.L., Lauber C., Leontovich A.M., Neuman B.W., Penzar D., Perlman S., Poon L.L.M., Samborskiy D.V., Sidorov I.A., Sola I., Ziebuhr J. The species Severe acute respiratory syndromerelated coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati A., Pomeranz C., Qamar Z., Thomas S., Frisch D., George G., Summer R., DeSimone J., Sundaram B. A comprehensive review of manifestations of novel coronaviruses in the context of deadly COVID-19 global pandemic. Am. J. Med. Sci. Receiv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundy P.M., Gerba C.P., Pepper I.L. Survival of coronaviruses in water and wastewater. Food Env. Virol. 2009;1:10–14. doi: 10.1007/s12560-008-9001-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hal M.S., Byun J., Cho Y., Rim J.H. RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2: quantitative versus qualitative. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;3099:30424. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30424-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart O.E., Halden R.U. Computational analysis of SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 surveillance by wastewater-based epidemiology locally and globally: feasibility, economy, opportunities and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata A., Katayama H., Kojima K., Sano S., Kasuga I., Kitajima M., Furumai H. Effects of rainfall events on the occurrence and detection efficiency of viruses in river water impacted by combined sewer overflows. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;468–469:757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller L., Mota C.R., Greco D.B. COVID-19 faecal-oral transmission: are we asking the right questions? Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindson J. COVID-19: faecal–oral transmission? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;17:14309. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0295-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holshue M., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K.H., Wiesman J., Bruce H., Spitters C., Ericson K., Wilkerson S., Tural A., Diaz G., Cohn A., Fox L., Patel A., Pharm D., Gerber S.I., Kim L., Tong S., Lu X., Lindstrom S., Pallansch M.A., Weldon W.C., Biggs H.M., Uyeki T.M., Pillai S.K. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan , China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISS . 2020. Interim Indications on the Management of Sewage Sludge for the Prevention of the Spread of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Report n. 9/2020. [In italiano] [Google Scholar]

- ISS . 2020. Recommendations for the Disinfection of Outdoor Environments and Road Surfaces for the Prevention of Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Report n.7/2020 [In Italiano] [Google Scholar]