Abstract

Brazil is in a critical situation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare workers that are in the front line face challenges with a shortage of personal protective equipment, high risk of contamination, low adherence to the social distancing measures by the population, low coronavirus testing with underestimation of cases, and also financial concerns due to the economic crisis in a developing country. This study compared the impact of COVID-19 pandemic among three categories of healthcare workers in Brazil: physicians, nurses, and dentists, about workload, income, protection, training, feelings, behavior, and level of concern and anxiety. The sample was randomly selected and a Google Forms questionnaire was sent by WhatsApp messenger. The survey comprised questions about jobs, income, workload, PPE, training for COVID-19 patient care, behavior and feelings during the pandemic. The number of jobs reduced for all healthcare workers in Brazil during the pandemic, but significantly more for dentists. The workload and income reduced to all healthcare workers. Most healthcare workers did not receive proper training for treating COVID-19 infected patients. Physicians and nurses were feeling more tired than usual. Most of the healthcare workers in all groups reported difficulties in sleeping during the pandemic. The healthcare workers reported a significant impact of COVID-19 pandemic in their income, workload and anxiety, with differences among physicians, nurses and dentists.

Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus, pandemic, health personnel, healthcare workers, surveys and questionnaires, Brazil

What do we already know about this topic?

Brazil is in a critical situation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare workers that are in the front line face challenges with a shortage of personal protective equipment, high risk of contamination, low adherence to the social distancing measures by the population, low coronavirus testing with underestimation of cases, and also financial concerns due to the economic crisis in a developing country.

How does your research contribute to the field?

The COVID-19 pandemic caused changes in workload, jobs and life of healthcare workers. It is extremely important to evaluate and compare the impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the healthcare workers: physicians, nurses, and dentists, regarding workload, income, PPE, training, behavior, feelings, and level of anxiety.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

This study provided essential information that will be useful in the future, for comparisons between different stages of the pandemic, and in future challenges to the healthcare workers.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov2). The World Health Organization (WHO) characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic due to the rapid increase in the number of cases. To date, on July 24, 2020, there are more than 15 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, including 619,150 deaths. Brazil has a current critical situation with the second-highest number of cases and deaths in the world.1

Unfortunately, an effective vaccine or medicine is not available to treat COVID-19, and the most efficient strategies for controlling the COVID-19 pandemic are preventive measures and social distancing. However, these interventions make this pandemic a problem more significant than a health crisis with an impact meaningful in societies, politics, and economies as a whole.2,3

In this context, the COVID-19 pandemic causes concerns to the entire population, especially the health care professionals that are essential and continued to work and maintained patient care, despite the social distance and lockdown adopted in many countries. Many of the healthcare workers are in the front line, in close contact with COVID-19 infected patients, at high risk of infection and of transmitting the disease to their families and coworkers.4 In Brazil, there is lack of a homogeneous, transparent, and comprehensive surveillance system for COVID-19 cases among Brazilian health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.5

The coronavirus pandemic represents one of the greatest health challenges worldwide in this century, and this has a more devastating effect in third world countries, like Brazil. An increase in the workload of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic was reported in other countries,6,7 but the financial impact to these professionals were not yet fully reported, especially in Brazil, that is facing an economic crisis that appears to be only in its beginning.

To prevent infection and transmission of COVID-19 by healthcare workers, the WHO and other national and international public health authorities recommended the use of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). However, a shortage of PPE is being observed as a result of the high demand considering the increasing number of cases.3 In Brazil, since the beginning of the pandemic, there is a great concern with the lack of PPE, low adherence to the social distancing measures suggested, and low coronavirus testing, indicating an underestimation of the number of cases in the country.5,8

Another critical aspect regarding the protection of healthcare workers is the training to deal with COVID-19 disease. A study performed with healthcare workers working in the National Health Service (NHS) across the United Kingdom showed that approximately 50% of them did not receive proper training.4 In addition to the risk of contamination, healthcare workers have suffered high-stress rates. Many studies observed high rates of anxiety, stress symptoms, mental disorders, and post-traumatic stress among the healthcare workers during the pandemic.9-15

Primary care services are slightly superior as compared to traditional health care. In the Brazilian health system, the first contact of patients occurs with professionals of the primary care service such as physicians, nurses and dentists.16 However, with the COVID-19 pandemic, there were changes in workload, jobs and general life of these professionals. This way, this study aimed to compare the impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the healthcare workers: physicians, nurses, and dentists, regarding workload, income, PPE, training, behavior, feelings, and level of anxiety.

Material and Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Research Committee of Ingá University Center Uningá, under number 31054320.6.0000.5220 and all participants agreed to participate in the survey.

Sample size calculation was performed with a confidence interval of 95% and margin of error of 5%, considering the application of a survey/questionnaire, with the number of physicians (496 422),17 nurses (2 321 509),18 and dentists (338 790),19 in Brazil, resulted in the need for at least 385 answers.

The sample was randomly selected among the three categories of healthcare workers in Brazil. A Google Forms (Google Inc, Mountain View, CA, USA) questionnaire was elaborated and sent by e-mail and WhatsApp messenger (WhatsApp Inc, Mountain View, CA, USA) to 700 healthcare workers. Inclusion criteria were: healthcare workers (physicians, nurses or dentists), above 22 years of age, working in the front line of the pandemic in private and public hospitals, healthcare units and private clinics, but not necessarily with direct contact with COVID-19 infected patients. Healthcare students were excluded from the sample.

In the introduction of the questionnaire, the informed consent approved by the human research ethics committee was described, and the subjects were informed about the objectives. The participant’s anonymity was ensured. The survey comprised questions about personal information, jobs, income, workload before, and during the pandemic. Personal protective equipment (PPE) and training for COVID-19 patient care and behavior during the pandemic were also assessed in the questionnaire.

A structured questionnaire was developed and tested on a pilot population before its administration in this study. The pilot study was undertaken with 30 healthcare workers previously and randomly selected to clarity the questions and the language used. Some words were rewritten with synonyms so that all participants were more likely to understand. The pilot study participants were not included in the main study.

The levels of concern, anxiety, anger, and impact of the pandemic were evaluated with a numerical rating scale from 0 to 10.20

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the intrarater agreement, one of the questions with yes/no responses was duplicated in the questionnaire. The answers to this duplicate question were compared using Kappa statistics. The result showed a coefficient of 0.96, indicating an excellent agreement.21

The percentage of distribution among the groups about sex, age, years of experience, income and workload information, knowledge about personal protective equipment (PPE), training to treat COVID-19 suspected or infected patients, and behavior during the pandemic were assessed with chi-square tests. The one-way ANOVA and Tukey tests were used for the intergroup comparison of the levels of anxiety and confidence about work, anger, concerns with family, and the influence of pandemic in the relationship with patients and the work team. Statistical analyzes were performed by Statistica software (Statistica for Windows, version 10.0, Statsoft, Tulsa, Okla, USA), and the results were considered significant at P < .05.

Results

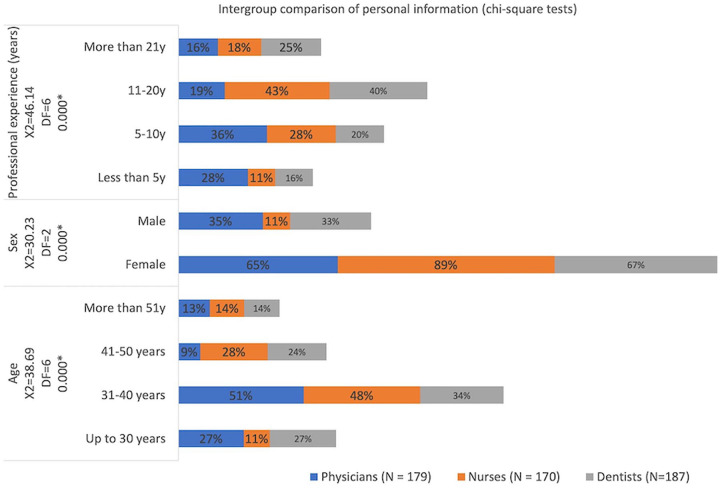

The response rate was 76.6% since a total of 536 healthcare workers answered the survey: 179 physicians (117 female; 62 males), 170 nurses (151 female; 19 male), and 187 dentists (125 female; 62 male). Most healthcare workers were between 31 and 40 years old, and physicians were younger than dentists and nurses. Females were the majority in all groups, but more significant in the nurses’ group. Physicians’ respondents had fewer years of experience in the profession than nurses and dentists (Figure 1; demographics).

Figure 1.

Intergroup comparison of personal information (demographics).

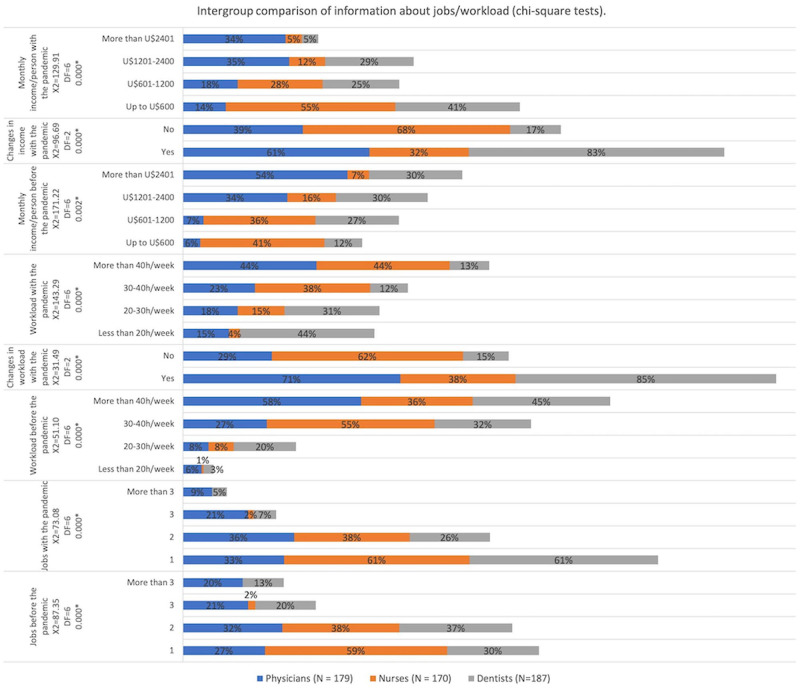

Physicians and dentists had more jobs than nurses before the pandemic. With the pandemic, the number of jobs reduced in all groups, but significantly more in the dentists’ group. Workload before the pandemic was higher for physicians, followed by dentists, and then the nurses, that presented a significantly lesser workload. The majority of physicians and dentists reported a reduction in workload during the pandemic. The monthly income was higher for physicians, followed by dentists and lesser for nurses. The majority of physicians and dentists reported a change in the monthly income with the pandemic. The income was reduced significantly in all professional groups and maintained the same pattern of difference between the groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Intergroup comparison of information about jobs/workload.

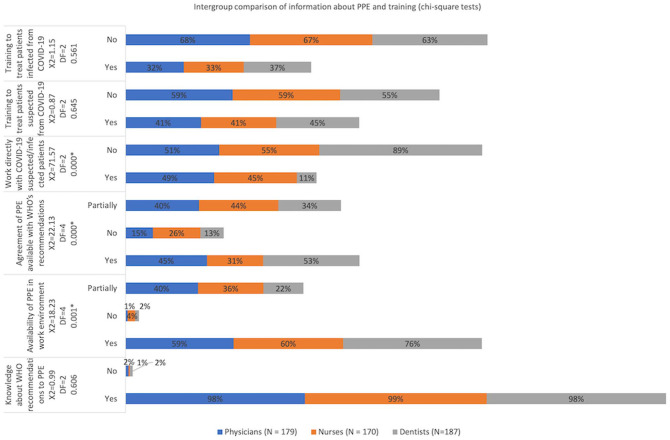

Almost all healthcare workers knew the WHO recommendations about the use of PPE. More nurses reported to have only partially the PPE, and more dentists have PPE in their work environment. More physicians and dentists reported that their work has PPE following the WHO recommendations than nurses, and approximately one-third of the healthcare workers reported that available PPE followed WHO recommendations. About half of the physicians and nurses were working directly with COVID-19 infected patients, but the minority of dentists were. Most healthcare workers did not receive training for treating patients suspected and infected from coronavirus (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Intergroup comparison of information about PPE and training.

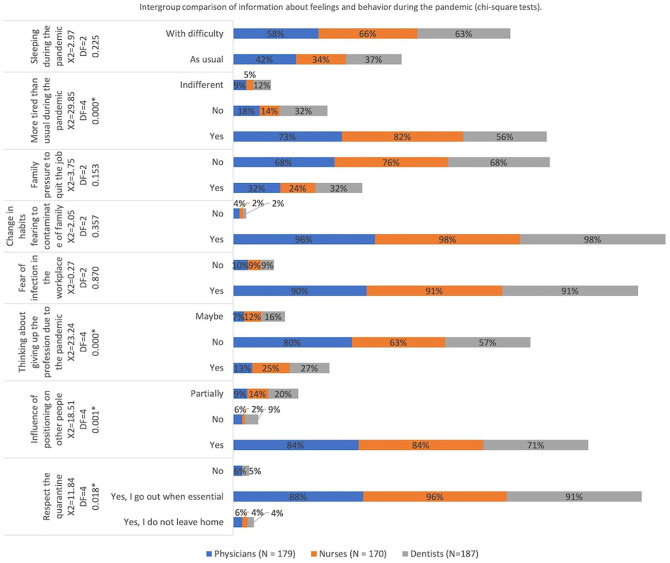

Nurses were respecting the quarantine more than physicians and dentists. Most of the healthcare workers believed that their positioning and behavior influence people around them, but physicians and nurses believed more than dentists. More dentists and nurses thought about giving up their jobs or professions after the beginning of the pandemic than physicians. In all groups, approximately 90% of the respondents reported being afraid of being infected by coronavirus in the clinical or hospital environment, and more than 95% of them changed habits fearing to contaminate their family members. The minority were pressured by family members to quit their jobs. More physicians and nurses were feeling more tired than usual than dentists. Most of the healthcare workers in all groups reported difficulties in sleeping during the pandemic (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Intergroup comparison of information about feeling and behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dentists felt less prepared and confident to care for COVID-19 patients than physicians, and nurses and dentists were more anxious and stressed with the pandemic. Nurses believed that the pandemic will have a more positive impact on their profession and that the experience during the pandemic will have a more significant influence in their professional future than physicians and dentists. The level of concern about infecting family members was high (above 8 of 10) and similar between the three groups. Physicians, nurses, and dentists were feeling comfortable similarly in providing patient care during the pandemic. Nurses were feeling angrier than physicians and dentists. Dentists reported being more anxious when providing patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic than physicians. Dentists answered that the relationship with the patient was more influenced by the pandemic than physicians and nurses, and the relationship of dentists with their work team was more influenced by the pandemic than physicians (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intergroup Comparison of the Level of Anxiety, Concern, and Impact of the Pandemic (one-way ANOVA and Tukey tests).

| Questions (responses in score of numerical rating scale) | Physicians (N = 179) |

Nurses (N = 170) |

Dentists (N = 187) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Prepared/confident for care of patients with COVID-19 | 6.08 (2.45) A | 5.73 (2.28) AB | 5.27 (2.79) B | .009* |

| Level anxiety/stress with the COVID-19 pandemic | 6.72 (2.34) A | 7.54 (2.15) B | 7.39 (2.49) B | .002* |

| Influence the pandemic on the job market to your professional | 5.91 (2.74) A | 7.14 (2.31) B | 5.25 (3.24) A | .000* |

| Influence the pandemic experience on professional future | 6.86 (2.35) A | 7.40 (2.18) B | 6.60 (2.79) A | .009* |

| Concern about infecting your family members | 8.41 (2.18) | 8.88 (1.88) | 8.69 (1.87) | .080 |

| Level of comfort in the work environment during the pandemic | 6.54 (2.60) | 6.84 (2.25) | 6.38 (2.63) | .225 |

| Level of anxiety when providing patient care during the pandemic | 6.71 (2.57) A | 7.22 (2.33) AB | 7.47 (2.41) B | .011* |

| Level of anger lately | 5.96 (3.05) A | 7.10 (2.54) B | 6.72 (2.73) A | .001* |

| Influence the pandemic in relationship with patients | 5.98 (2.99) A | 6.33 (2.89) A | 7.17 (2.78) B | .000* |

| Influence the pandemic in relationship with work team | 5.54 (3.18) A | 5.92 (3.18) AB | 6.42 (3.22) B | .033* |

Note. Different letters in the same row indicate the presence of a statistically significant difference between the groups.

Statistically significant for P < .05.

Discussion

This survey gives a broad outlook of the Brazilian healthcare workers’ views about the COVID-19 pandemic. At first, it is necessary to bring the Brazilian context in facing of the pandemic, mainly because the projections about the behavior of the pandemic and people related to it depend not only on scientific knowledge but mainly on quality and reliable data regarding the new disease,5,22 and currently it is not possible in Brazil. There is no clear leadership.23,24 Since May 15, 2020, Brazil does not have a health minister, and the governors and the president of the republic do not follow the same guidelines regarding the implementation of quarantine and medications. Effective quarantines and lockdown measures were not even implemented in Brazil. While the world scientific community says that only strict social isolation measures can slow the spread of the virus25,26 and that there is still no effective pharmacological treatment for COVID-19,27 the Brazilian denialist actual president24,28 insists on reopening of business offices, schools and churches, he also is against the use of face masks. He makes open advertisements about a medicine whose studies have already been canceled by WHO because the medicine is not effective against coronavirus.27 So, in Brazil, there have been no federal guidelines for primary health care services in response to COVID-19.28 Amid this situation, the healthcare workers do not know whether to follow the WHO recommendations or the president’s denialist recommendations. The national response is, in practice, being guided by developments at the local level, without any semblance of central coordination.28

Healthcare in Brazil is the responsibility of the municipalities, using the Health Unic System (called SUS in Brazil), including pandemic preparedness. It means that matters such as the provision of PPE, rules on social distancing, and testing arrangements vary.24

Starting from this specific information, it is then possible to begin to affirm that the COVID-19 pandemic has burdened unprecedented psychological stress on people around the world, especially the medical workforce.29 Emotional and behavioral reactions that healthcare workers may experience during this crisis (e.g., difficulty sleeping, anger) are also being shared by the entire community.30 Healthcare providers are vital resources for every country, mainly in disruptive periods like this that we are facing. The intensive work drained healthcare providers physically and emotionally,6 and the entire population trusts in the work of these professionals and hopes that they can carry out their tasks safely and correctly. Therefore, it is essential to know the impact that the pandemic has had on health professions to promote strategies to counteract stressors and challenges during this outbreak. Studies like this are necessary because mobilization now will allow public health to apply the learnings gained to any future periods of increased infection and lockdown, which will be particularly crucial for healthcare workers and vulnerable groups, and to future pandemics.31 Reporting information like this is essential to plan future prevention strategies.10

The questionnaire was created using Google Forms and was sent via a link in a messaging app, e-mail and social media, and is in accordance with Iqbal et al.4 Consolo et al32 also used Google Forms to create their survey, but they sent it via an anonymous e-mail. In this study, a messaging app was chosen because they are practical and can be accessed quickly by cell phone, which facilitates the healthcare workers’ response.

Most health care workers were in the 31 to 40 years age range (Figure 1). Lai et al33 found similar results; however, the respondents of Chew et al9 were younger (age range: 25-35 years). This age difference, although not significant, may have been due to the methodology that the surveys were conducted. Chew et al9 survey was conducted directly at the healthcare workers’ workplace, while this present study sends on-line questionnaires via messaging app. The greatest part of the respondents were females, and also the females were the majority in all health profession groups, but even so, greater in the nurses’ group (Figure 1) Other authors found similar results.9,33 Also, cross-sectional studies show minimal male participants in this type of study.32,34 Besides that, women are more willing to participate in researches,35 and the majority of nursing professionals in Brazil are females.36

The workload was reduced for physicians and dentists during the pandemic (Figure 2). This reduction was observed because quarantines were recommended in several cities in Brazil, and private practices, both for physicians and dentists, were closed for elective procedures. This result also justifies why the dentists and physicians had more jobs than nurses before the pandemic. Most respondent nurses work in public health, with a predetermined workload, which has not been changed due to the pandemic. Besides that, the income was significantly reduced in all professional groups (Figure 2). It is known that a pandemic often brings economic recession, and this is what happened during the first quarter of 2020.37,38 This result is in agreement with a study about dental practitioners,32 conducted in Italy in the early stages of the pandemic, where all respondents reported practice closure or substantial activity reduction with serious concerns regarding their professional future and economic crisis. Previous crises have shown how an economic crash has direct consequences for public39 and this is no different for healthcare workers. With the increasing cases in Brazil, it was expected that job opportunities would also increase, but this was not observed in this study, no new hires were made, which leads to the conclusion that the concern about the future financial impact is great among health professionals. However, this survey was conducted in an earlier stage of the pandemic, and now, in the peak, this scenario may have changed.

It can be speculated that physicians and dentists have more PPE following WHO recommendations than nurses because as most of them work in their private practice, they bought the necessary PPE themselves, while the majority of the nurses work in public health, where PPE is sometimes not adequate (Figure 3). PPE has gained even more importance in recent times because with the increased demand for use, PPE has become more expensive and scarcer. Healthcare workers reported that there was limited access to essential PPE and support from healthcare authorities during the COVID-19 pandemic from Latin America to Europe.3,4 Some physicians related reusing face masks that are meant to be disposable because their hospitals may run out in the next few weeks.30 Consolo et al32 related that 77% of the dentists in their study increased the use of PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the professionals’ inherent concern with PPE, in Brazil there is also a concern about the shortage of supplies needed to treat the more severe patients, scarce availability of diagnostic tests and constant tension regarding the collapse of the ICU beds available is also observed.5 To date and exemplify, as of July 22, drugs used to keep ICU patients sedated will end in four days on Paraná state, in the South region of Brazil.40

About half of the physicians and nurses were working directly with COVID-19 infected patients, but the minority of dentists were (Figure 3). A survey conducted in the United Kingdom in the first two weeks of April showed similar results, where 95.26% of the healthcare workers had direct patient contact in daily activity.4 Dentists had less contact with infected patients because as already seen, their elective appointments were suspended due to the quarantine.41,42 In this scenario, it would be expected that healthcare workers have adequate training to care for patients infected with COVID-19, but most healthcare workers did not receive this training. In a study conducted in the UK, half of the healthcare workers also reported that they did not have adequate training. As already stated here, this is an unprecedented event, so many countries, even the richest, are having difficulties in establishing training protocols for healthcare workers. Besides that, dentists reported being more anxious when providing patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic than physicians (Figure 3 and Table 1). It is reasonable that dentists feel more anxious to assist patients during the pandemic, as it is known that the contamination rate of this disease is very high in aerosols and droplets,43,44 which makes the dental community a relatively high-risk population. However, it is essential to highlight that in the early stages of the pandemic, the Brazilian Ministry of Health launched a national program called “Brazil Counts on Me”.45 This program focused on training and registering healthcare workers to face the coronavirus pandemic. It seems that many professionals did not do this training offered by the government. Moreover, a recent survey29 showed that as compared to the non-clinical staff, front line medical staff with close contact with infected patients showed higher scores of fear, anxiety and depression. This implies that effective strategies toward to improving mental health should be provided to these individuals.29

Healthcare workers often feel fully responsible for the well-being of their patients. They usually face the challenges of work as their duty.6 This has become more evident in recent times and could reflect in the way that they influence people around them, like respecting the quarantine, as an example. In this study, the majority of the healthcare workers believed that their positioning and behavior influence people around them, and physicians and nurses believed more than dentists (Figure 4). One can say that physicians and nurses believed they have a more considerable influence on society than dentists due to the nature of their work. People, in general, tend to view physicians and nurses as essential professionals, and they tend to observe them as an example, even outside the work environment. So, it is natural for them to believe that their behavior can influence (in a positive way) the people around them.

In all groups, approximately 90% of the respondents reported being afraid of contamination by the coronavirus in the clinical or hospital environment (Figure 4), agreeing with previous reports.4,32 This was probably the cause of more dentists and nurses thought about giving up their jobs or professions during the pandemic, although the minority of healthcare workers reported pressure from family members to quit their jobs (Figure 4). As already discussed above, several factors must be related to the insufficient training to care for infected patients, lack of adequate PPE, and decreased income. Another point that must be taken into account is the amount of healthcare workers deaths by the coronavirus, which is alarmingly high in Brazil. In May 2020, which was the early stage of the pandemic in Brazil, Brazil already surpassed the USA in deaths of nursing professionals by COVID-19 and had more deaths than Italy and Spain combined.18

Most of the healthcare workers in all groups reported difficulties in sleeping during the pandemic (Figure 4). Previous pandemic experiences showed that these reactions reflect a sense of fearful waiting, or even terror, about what the future may hold for all humankind while an unfamiliar and uncomfortable quiet fills the halls.46 This is expected because the own nature of the pandemic and the unique characteristics and unpredictable evolution of the COVID-19 disease, like a uniquely high risk of asymptomatic transmission and significant knowledge gaps about the viral pathophysiology47,48 can also lead to loss of sleep. Recent studies showed that a significant part of the healthcare workers presented symptoms of insomnia.9,33,34 All these features generate many uncertainties in healthcare workers, but, for the Brazilian ones, the challenge is even greater, and the scenario is even scarier. Additionally to the already established insufficient scientific knowledge about the new virus and its high speed of dissemination,49,50 little is known about the transmission characteristics of the COVID-19 in a context of great social and demographic inequality. Here in Brazil, people are living in precarious housing and sanitary conditions, without constant access to water, in an agglomeration and with a high prevalence of chronic diseases.22

Nurses and dentists were more anxious and stressed with the pandemic, and nurses were feeling angrier than the other healthcare workers evaluated in this survey (Table 1). A recent systematic review showed that anxiety was the most prevalent mental health symptom during the pandemic.12 Studies on the mental health of the healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that there are occupational differences regarding affective symptoms among healthcare workers, and nurses showed the highest levels.34 Besides that, nurses may face a higher risk of exposure to COVID-19 patients as they spend more time in the front line, providing direct care of patients.6 Dentists, physicians, and nurses had a similar level of concern about infecting family members (Table 1). It was observed that more physicians and nurses were feeling more tired than usual than dentists. This was expected, because, in addition to all the concerns inherent to the actual moment, these two categories of healthcare workers are dealing directly with infected patients, and there are also other contributing factors related to this: excessive workload and work hours, work-life imbalance, inadequate support, insufficient rewards, interpersonal communication, and sleep privation).13 Although many of the health care workers accept the increased risk of infection as part of their chosen profession, some may have concerns about family transmission or feel pressure to comply because of fear of losing their job, desire to be part of the team, and altruistic goals of caring for patients in need.30

Disruptive periods like this generate uncertainty and fear of the unknown, especially in the professional field. When asked how the COVID-19 pandemic could influence the future of their professions, nurses were more optimistic than physicians and dentists. They believed that the pandemic would have a more positive impact on their profession. Consolo et al32 showed that ¾ of the respondent dentists reported that there had been an extremely negative impact on their practice.

Dentists believed that the relationship with the patient and their staff were more influenced by the pandemic than physicians and nurses (Table 1). This is understandable, as dentists usually have a very close relationship with their patients and staff. Since the dental team is considered to be at high risk for COVID-19 infection, dental offices had to prepare for providing care, improving communication with their patients, changing the routine of their dental offices, and improving the PPE of their employees and patients. In the long term, patients will notice these changes and will value professionals who care about them. On the other hand, according to Consolo et al32 there is a concern regarding the inability to prevent the end of the pandemic, followed by the impaired economy that might affect future patient turnover and the capability to pay for the dental practice expenses, which include buying further devices and to adequate to new clinical protocols to counteract the spreading of SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusions

The number of jobs reduced to all healthcare workers during the pandemic, but this reduction was more significant for dentists. Also, the workload and income reduced to all healthcare workers.

Almost all healthcare workers were aware of the WHO recommendations about the use of PPE. Nurses related that their work has PPE partially following the WHO recommendations. Most healthcare workers did not receive training for treating patients suspected and infected from coronavirus.

Physicians and nurses were feeling more tired than usual than dentists. Most of the healthcare workers in all groups reported difficulties in sleeping during the pandemic. Dentists reported being more anxious when providing patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic than physicians.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Karina Maria Salvatore Freitas  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9145-6334

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9145-6334

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation Report 187. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200725-covid-19-sitrep-187.pdf?sfvrsn=1ede1410_2. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- 2. Tang Y, Serdan TDA, Masi LN, Tang S, Gorjao R, Hirabara SM. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in Brazil: using a mathematical model to estimate the outbreak peak and temporal evolution. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1453-1456. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1785337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delgado D, Wyss Quintana F, Perez G, et al. Personal safety during the COVID-19 pandemic: realities and perspectives of healthcare workers in Latin America. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2798. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iqbal MR, Chaudhuri A. COVID-19: results of a national survey of United Kingdom healthcare workers’ perceptions of current management strategy - a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Int J Surg. 2020;79:156-161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pessa Valente E, Cruz Vaz da Costa Damasio L, Luz LS, da Silva Pereira MF, Lazzerini M. COVID-19 among health workers in Brazil: the silent wave. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):010379. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e98. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Felice C, Di Tanna GL, Zanus G, Grossi U. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on healthcare workers in Italy: results from a national e-survey. J Community Health. 2020;45(4):675-683. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00845-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. PAHO. COVID-19: PAHO Director calls for “extreme caution” when transitioning to more flexible social distancing measures. https://www.paho.org/en/news/14-4-2020-covid-19-paho-director-calls-extreme-caution-when-transitioning-more-flexible-social. Accessed July 24, 2020.

- 9. Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak [published online ahead of print April 21, 2020]. Brain Behav Immun. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El-Hage W, Hingray C, Lemogne C, et al. [Health professionals facing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: what are the mental health risks?]. Encephale. 2020;46(3S):S73-S80. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ornell F, Schuch JB, Sordi AO, Kessler FHP. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42(3):232-235. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shah K, Chaudhari G, Kamrai D, Lail A, Patel RS. How essential is to focus on physician’s health and burnout in coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic? Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7538. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020:89(4):242-250. doi: 10.1159/000507639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu J, Sun L, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms in the first-line medical staff fighting against COVID-19 in Gansu. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:386. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Viacava F, Oliveira RAD, Carvalho CC, Laguardia J, Bellido JG. SUS: supply, access to and use of health services over the last 30 years. Cien Saude Colet. 2018;23(6):1751-1762. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232018236.06022018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Federal Council of Medicine. Statistics. https://portal.cfm.org.br/index.php?option=com_estatistica. Accessed June 28, 2020.

- 18. Federal Council of Nursing. Enfermagem em Números. http://www.cofen.gov.br/enfermagem-em-numeros. Accessed June 28, 2020.

- 19. Federal Council of Dentistry. General number of specialist dental surgeons. http://website.cfo.org.br/estatisticas/quantidade-geral-de-cirurgioes-dentistas-especialistas/

- 20. Johnson C. Measuring pain. Visual analog scale versus numeric pain scale: what is the difference? J Chiropr Med. 2005;4(1):43-44. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60112-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barreto ML, Barros AJDd, Carvalho MS, et al. What is urgent and necessary to inform policies to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil? Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2020;23:e200032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Freitas KMS, Cotrin P. COVID-19 and orthodontics in Brazil: what should we do? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158(3):311. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burki T. COVID-19 in Latin America. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):547-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sacchi BC, de Oliveira Cotrim I, dos Santos VKJ, Campiolo EL. Impacts and effectiveness of quarantine in the outbreak of COVID-19: a comparison among pandemics. InterAm J Med Health. 2020;3. doi: 10.31005/iajmh.v3i0.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferguson N, Laydon D, Nedjati Gilani G, et al. Report 9: impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand. 2020. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-9-impact-of-npis-on-covid-19/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27. Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M, Giarratano A, Einav S. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J Crit Care. 2020;57:279-283. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lotta G, Wenham C, Nunes J, Pimenta DN. Community health workers reveal COVID-19 disaster in Brazil. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):365-366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31521-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong AH, Pacella-LaBarbara ML, Ray JM, Ranney ML, Chang BP. Healing the healer: protecting emergency health care workers’ mental health during COVID-19 [published online ahead of print May 3, 2020]. Ann Emerg Med. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547-560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Consolo U, Bellini P, Bencivenni D, Iani C, Checchi V. Epidemiological aspects and psychological reactions to COVID-19 of dental practitioners in the Northern Italy Districts of Modena and Reggio Emilia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3459. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print May 8, 2020]. Brain Behav Immun. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2):e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Machado MH, Aguiar Filho W, de Lacerda WF, et al. General characteristics of nursing: the socio-demographic profile. Enf Foco. 2016;7(ESP):9-14. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Craven M, Liu L, Wilson M, Mysore M. COVID-19: implications for business. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk/our-insights/covid-19-implications-for-business. Accessed May 3, 2020.

- 38. Farooq I, Ali S. COVID-19 outbreak and its monetary implications for dental practices, hospitals and healthcare workers [published online ahead of print April 3, 2020]. Postgrad Med J. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McKee M, Stuckler D. If the world fails to protect the economy, COVID-19 will damage health not just now but also in the future. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):640-642. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. RPC Paraná. Coronavirus: drugs used to keep ICU patients sedated end in four days in Paraná, says secretary. https://g1.globo.com/pr/parana/noticia/2020/07/22/coronavirus-medicamentos-usados-para-manter-pacientes-de-uti-sedados-acabam-em-quatro-dias-no-parana-diz-secretario.ghtml. Accessed July 26, 2020.

- 41. Cotrin P, Peloso RM, Oliveira RC, et al. Impact of coronavirus pandemic in appointments and anxiety/concerns of patients regarding orthodontic treatment [published online ahead of print May 25, 2020]. Orthod Craniofac Res. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Peloso RM, Pini NIP, Sundfeld Neto D, et al. How does the quarantine resulting from COVID-19 impact dental appointments and patient anxiety levels? Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e84. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564-1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970-971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ministry of Health. MS/GM Ordinance No. 639, of March 31, 2020. Provides for the strategic action “Brazil Counts with Me-Health Professionals”, aimed at training and registering health professionals, to face the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). http://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-n-639-de-31-de-marco-de-2020-250847738. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- 46. Biggs QM, Fullerton CS, Reeves JJ, Grieger TA, Reissman D, Ursano RJ. Acute stress disorder, depression, and tobacco use in disaster workers following 9/11. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(4):586-592. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406-1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19). Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19 - navigating the uncharted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1268-1269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931-934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]