Key Points

Question

Have rates of alcohol abstinence and marijuana abstinence, co-use, and use disorders changed in US young adults from 2002 to 2018 as a function of college status?

Findings

A nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted annually of 182 722 US young adults found that alcohol abstinence, marijuana use, and co-use of alcohol and marijuana all increased between 2002 and 2018. These findings were apparent for both college students and non–college students.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that colleges and communities should create and maintain supportive resources in response to the recent changes in the US young adult substance use landscape, accounting for increases in alcohol abstinence, marijuana use, and co-use of alcohol and marijuana.

Abstract

Importance

Recent information on the trends in past-year alcohol abstinence and marijuana abstinence, co-use of alcohol and marijuana, alcohol use disorder, and marijuana use disorder among US young adults is limited.

Objectives

To assess national changes over time in past-year alcohol and marijuana abstinence, co-use, alcohol use disorder, and marijuana use disorder among US young adults as a function of college status (2002-2018) and identify the covariates associated with abstinence, co-use, and marijuana use disorder in more recent cohorts (2015-2018).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study examined cross-sectional survey data collected in US households annually between 2002 and 2018 as part of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. The survey used an independent, multistage area probability sample for all states to produce nationally representative estimates. The sample included 182 722 US young adults aged 18 to 22 years. The weighted screening and weighted full interview response rates were consistently above 80% and 70%, respectively.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Measures included past-year abstinence, alcohol use, marijuana use, co-use, alcohol use disorder, marijuana use disorder, prescription drug use, prescription drug misuse, prescription drug use disorder, and other drug use disorders based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria.

Results

The weighted sample comprised 51.1% males. Between 2002 and 2018, there was an annual increase in past-year alcohol abstinence among young adults (college students: 0.54%; 95% CI, 0.44%-0.64%; non–college students: 0.33%; 95% CI, 0.24%-0.43%). There was an annual increase in marijuana use from 2002 to 2018 (college: 0.46%; 95% CI, 0.37%-0.55%; non-college: 0.49%; 95% CI, 0.40%-0.59%) without an increase in marijuana use disorder for all young adults. Past-year alcohol use disorder decreased annually (college: 0.66%; 95% CI, 0.60%-0.74%; non-college: 0.61%; 95% CI, 0.55%-0.69%), while co-use of alcohol and marijuana increased annually between 2002 and 2018 among all young adults (college: 0.60%; 95% CI, 0.51%-0.68%; non-college: 0.56%; 95% CI, 0.48%-0.63%). Young adults who reported co-use of alcohol and marijuana or met criteria for alcohol use disorder and/or marijuana use disorder accounted for 82.9% of young adults with prescription drug use disorder and 85.1% of those with illicit drug use disorder. More than three-fourths of those with both alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder reported past-year prescription drug use (78.2%) and illicit drug use (77.7%); 62.2% reported prescription drug misuse.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that US colleges and communities should create and maintain supportive resources for young adults as the substance use landscape changes, specifically as alcohol abstinence, marijuana use, and co-use increase. Interventions for polysubstance use, alcohol use disorder, and marijuana use disorder may provide valuable opportunities for clinicians to screen for prescription drug misuse.

This cross-sectional study examines changes over time in the use and disordered use of alcohol and controlled substances in US young adults attending vs not attending college.

Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are most prevalent among US young adults compared with other US age groups, and 2 of the most common SUDs are alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder.1,2,3 Recently, marijuana use has increased and alcohol use has decreased among US young adults, but trends in the co-use of these substances remain largely unknown.3,4 Consequences associated with alcohol, marijuana, and other drug use during young adulthood include injury, SUDs, depressive symptoms, overdose, and death.5,6,7

The transition from adolescence to young adulthood is an important developmental period for studying substance use behaviors because emerging adults often experience less parental monitoring and make increasingly independent decisions.8,9 Although the association between college attendance and substance use differs based on the substance used, the college environment can also directly affect substance use behavior, acting as either a protective influence or a risk factor.4,9 Research has shown that binge drinking, prescription stimulant misuse, and alcohol use disorder are more prevalent among college students than non–college students.4,10,11,12 In contrast, marijuana use, prescription opioid misuse, prescription sedative or tranquilizer misuse, and multiple SUDs are more prevalent among non–college students.4,12,13,14,15

Earlier studies examining changes over time in substance use behaviors among young adults focused largely on individual substances used by US college students.16,17,18 One concerning change between 1993 and 2001 was an increased risk for developing alcohol use disorder as a result of increased frequency of binge drinking.16 There was also an increase in past-year alcohol abstinence over the same period, from 16.4% in 1993 to 19.3% in 2001, suggesting a polarization of drinking behavior.17 The polarization of increased alcohol abstinence and high-risk drinking over the same period among college students occurred alongside a decrease in low-risk drinking.17 This change suggests a need for a more nuanced examination of long-term changes associated with alcohol involvement among US young adults. In addition, increases in marijuana use were found in US young adults between 1993 and 2017,4,18,19 especially among non–college students, with daily marijuana use reaching an all-time high of 13.2% in 2016.4 Although national data often focus on individual substances, it is useful to also examine changes in polysubstance use and multiple SUDs.20,21,22 Polysubstance use and multiple SUDs have been shown to be more persistent in their course and challenging to treat.20,21,22

Despite the increased focus on substance use changes among US adolescents,21,23 there has been a dearth of research examining trends in abstinence from substance use among US young adults, as well as little research differentiating these changes by educational status over the past 2 decades. The aim of the present study was to use nationally representative data collected from 17 cohorts of US young adults aged 18 to 22 years, with 2 objectives. The first was to identify the long-term changes (2002-2018) in past-year abstinence, nondisordered substance use (ie, substance use that does not meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV] criteria for SUD), and SUD based on DSM-IV criteria of alcohol use disorder, marijuana use disorder, and both alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder (ie, disordered co-use) as a function of college status. The second objective was to examine the prevalence of past-year prescription drug use, prescription drug misuse, illicit drug use, and SUDs based on DSM-IV criteria as a function of alcohol and marijuana use among US young adults in recent cohorts (2015-2018).

Methods

This study examined cross-sectional data collected annually in household surveys between 2002 and 2018 as part of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The NSDUH used an independent, multistage area probability sample for all states to produce nationally representative data. Interviews began with audio computer-assisted self-interviewing questions on sensitive variables such as substance use. Audio computer-assisted self-interviewing was used to ensure privacy and promote honest reporting and data completeness. Response rates for the NSDUH were consistently above 80% for the weighted screening and above 70% for the weighted full interview. Details regarding NSDUH methods are available elsewhere.24,25 The present study was exempt from review and need for informed patient consent by the Texas State University Institutional Review Board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.26

Measures

College status among respondents aged 18 to 22 years was categorized as college student and non–college student. Respondents were classified as college students if they reported that they were in their first through fourth year at a college or university and were either full- or part-time students (ranging from 44.5% to 51.0% between 2002 and 2018). Respondents were classified as non–college students if their current enrollment status was known and they were not classified as a full- or part-time college student (ranging from 38.9% to 44.9% between 2002 and 2018). Respondents who were on breaks in the school year were considered enrolled if they intended to return to college or university when the break ended. Respondents who were in high school, graduated college, or had an unknown current college enrollment status were considered another cohort and excluded from most analyses (ranging from 9.4% to 11.5% between 2002 and 2018).

Alcohol, marijuana, and other substance use included past-year alcohol use, past-year marijuana use, past-year other illicit drug use, and past-year prescription drug use/misuse. Past-year alcohol use, past-year marijuana use, and past-year other illicit drug use, including heroin, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, and methamphetamine, were all assessed from 2002 to 2018. Prescription drug use and misuse were assessed from 2015 to 2018 by asking respondents a series of questions regarding the use and misuse of prescription opioids, stimulants, and sedatives/tranquilizers in the past 12 months. The time frame for prescription drug use and misuse differed from other substances owing to wording changes in the NSDUH made in 2015. From 2015 to 2018, the NSDUH defined prescription drug misuse as “use without a prescription of one's own; use in greater amounts, more often, or longer than told to take a drug; or use in any other way not directed by a doctor.”25

Substance use disorders were assessed using past-year DSM-IV alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder criteria. Similar measures of other drug use disorders were assessed. Earlier studies reported that these measures have good reliability and validity.27,28 Nondisordered alcohol use and nondisordered marijuana use were defined as alcohol use and marijuana use that did not meet DSM-IV criteria for alcohol use disorder or marijuana use disorder. For combined alcohol and marijuana past-year use, a 7-level variable was created: (1) abstinence from both, (2) nondisordered alcohol use, (3) nondisordered marijuana use, (4) nondisordered co-use (ie, use of both alcohol and marijuana without meeting disorder criteria), (5) alcohol use disorder only, (6) marijuana use disorder only, and (7) both alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder.

Sociodemographic variables and other controls included sex, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, income, population density, religion, and physical health (self-reported health, body mass index, and hospitalizations). Mental health variables included mental health treatment, major depression, psychological distress, disability, and suicidal ideation.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses used Stata, version 16.0 (StataCorp, LLC), using svy commands to account for the NSDUH complex survey design. The NSDUH data were weighted, clustered on primary sampling units, and stratified. The Taylor series approximation was used, with adjusted degrees of freedom, to create robust variance estimates. Initially, weighted cross-tabulations estimated the annual prevalence of sex, race/ethnicity, and college enrollment status. Potential change over the study period was evaluated using binary logistic regression for sex and multinomial logistic regression for race/ethnicity and college enrollment status, with estimates of linearized annual change (via the Stata margins command, which calculates predicted trend slope, adjusting for average covariate values over the study period) for analyses significantly associated with year. Analyses with subpopulations (eg, college students and non–college students) used the subpop option. For all analyses examining annual change and all regression analyses thereafter, we adjusted for changing sociodemographic variables from 2002 to 2018. Over these 17 years, the US population changed in terms of race/ethnicity and college status (eTable 1 in the Supplement), making these annual adjustments necessary. We also adjusted analyses for income and population density. Based on the number of comparisons made in the present study, we focused on statistical significance for all analyses with a 2-sided P value <.001.

For alcohol use, marijuana use, and their co-use, weighted cross-tabulations estimated the prevalence of abstinence, nondisordered use, and use disorders (separately for alcohol and marijuana). Prevalence estimates were computed separately among those in college and those not in college, followed by multinomial regression analyses to evaluate the association of year with alcohol and marijuana use status. The margins command was used to evaluate annual change in models significantly associated with year, controlling for the variables noted above.

A third set of analyses used logistic regression to evaluate the association of alcohol and marijuana use status with any past-year prescription drug use, prescription drug misuse, prescription drug use disorders, illicit drug use (cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, methamphetamine, or inhalants), or illicit drug use disorders. Analyses controlled for sex, race/ethnicity, family income, and population density, with past-year abstinence from both alcohol and marijuana set as the reference group for the co-use variable. These analyses used data from the 2015-2018 NSDUH data sets only, as the prescription use/misuse assessment was changed between 2014 and 2015, making comparisons of prescription use and misuse between 2015-2018 and 2002-2014 data invalid.29

Results

Between 2002 and 2018, a total of 182 772 US young adults aged 18 to 22 years completed the NSDUH. The weighted sample, as described in eTable 1 in the Supplement, was 51.1% male, 48.9% female, 58.3% White, 19.7% Hispanic/Latino, 14.2% Black, 4.9% Asian, 1.9% multiracial, and 1.1% other. Relative to White respondents aged 18 to 22 years, the prevalence of respondents who identified as Black, Asian, multiracial, or Hispanic/Latino increased over time. While White respondent prevalence decreased by 0.70% annually (95% CI, 0.61%-0.79%), the prevalence of Black (0.03%; 95% CI, −0.04% to 0.08%), Asian (0.14%; 95% CI, 0.10%-0.18%), multiracial (0.11%; 95% CI, 0.09%-0.12%), and Hispanic/Latino respondents (0.43%; 95% CI, 0.35%-0.51%) increased. The proportion of those in college increased and decreased over the study period; however, the proportion of those not in college decreased by 0.16% annually (95% CI, 0.07%-0.24%) and respondents who selected the other racial category increased by 0.08% per year (95% CI, 0.04%-0.12%).

As reported in Table 1,30 marginal estimates indicated that past-year alcohol abstinence increased for both college students and non–college students from 2002 to 2018. For example, 20% of college students reported alcohol abstinence in 2002, compared with 28% in 2018. Similarly, 23.6% of non–college students reported alcohol abstinence in 2002 compared with 29.9% in 2018. Alcohol use disorder prevalence decreased for both groups, with an annual decrease of 0.66% (95% CI, 0.60%-0.74%) for college students and 0.61% (95% CI, 0.54%-0.69%) for non–college students.

Table 1. Trends in Abstinence, Substance Use Behaviors, and Disorders by College Statusa.

| Variable | Weighted % | Annualized change, % (95% CI) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| Unweighted sample size, No. | 10 151 | 10 514 | 10 691 | 10 626 | 10 179 | 10 368 | 10 884 | 10 844 | 10 945 | 10 987 | 10 466 | 10 106 | 7250 | 7845 | 7325 | 7322 | 7456 | NA |

| Alcohol: college students | ||||||||||||||||||

| Abstinence | 20.0 | 18.6 | 20.2 | 20.0 | 18.1 | 19.9 | 21.7 | 19.5 | 20.6 | 23.9 | 23.8 | 24.2 | 26.3 | 27.4 | 26.9 | 28.7 | 28.0 | 0.54 (0.44 to 0.64) |

| Nondisordered alcohol use | 60.3 | 62.6 | 60.3 | 60.5 | 62.1 | 60.8 | 60.2 | 63.7 | 62.1 | 60.6 | 61.1 | 63.0 | 60.7 | 61.7 | 62.5 | 62.3 | 62.2 | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.22) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 19.7 | 18.8 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 19.8 | 19.3 | 18.2 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 10.9 | 10.6 | 8.9 | 10.0 | −0.66 (−0.74 to −0.60) |

| Alcohol: non–college students | ||||||||||||||||||

| Abstinence | 23.6 | 24.2 | 23.3 | 25.5 | 25.6 | 24.8 | 24.2 | 23.1 | 24.1 | 26.3 | 24.3 | 25.5 | 24.7 | 26.8 | 29.9 | 28.2 | 29.9 | 0.33 (0.24 to 0.43) |

| Nondisordered alcohol use | 57.2 | 59.1 | 58.1 | 56.9 | 57.4 | 57.8 | 59.1 | 60.0 | 59.6 | 59.6 | 61.2 | 61.5 | 62.8 | 62.6 | 59.4 | 61.9 | 60.8 | 0.28 (0.18 to 0.37) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 19.2 | 16.7 | 18.7 | 17.6 | 17.0 | 17.4 | 16.8 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 14.1 | 14.6 | 13.0 | 12.5 | 10.6 | 10.7 | 9.9 | 9.3 | −0.61 (−0.69 to −0.55) |

| Marijuana: college students | ||||||||||||||||||

| Abstinence | 67.1 | 68.1 | 68.1 | 69.2 | 68.7 | 69.0 | 68.2 | 65.4 | 67.0 | 66.4 | 65.8 | 65.5 | 65.7 | 65.6 | 65.2 | 64.2 | 63.2 | −0.41 (−0.51 to −0.31) |

| Nondisordered marijuana use | 26.9 | 25.7 | 24.9 | 24.9 | 25.5 | 25.3 | 25.7 | 28.3 | 27.1 | 28.1 | 27.8 | 29.1 | 29.5 | 28.8 | 29.8 | 30.3 | 30.8 | 0.46 (0.37 to 0.55) |

| Marijuana use disorder | 6.0 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 6.1 | −0.05 (−0.10 to 0.01) |

| Marijuana: non–college students | ||||||||||||||||||

| Abstinence | 66.8 | 67.5 | 68.0 | 68.9 | 69.8 | 69.5 | 70.0 | 65.3 | 67.6 | 66.6 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 63.7 | 64.4 | 63.4 | 62.5 | 62.9 | −0.41 (−0.51 to −0.31) |

| Nondisordered marijuana use | 25.7 | 24.7 | 23.9 | 23.9 | 23.1 | 23.0 | 22.7 | 27.9 | 25.5 | 25.7 | 27.8 | 28.3 | 30.2 | 29.5 | 30.2 | 31.4 | 30.0 | 0.49 (0.40 to 0.59) |

| Marijuana use disorder | 7.5 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 7.1 | −0.09 (−0.14 to −0.04) |

| Marijuana and alcohol: college students | ||||||||||||||||||

| Abstinence of both | 19.5 | 18.1 | 19.4 | 19.3 | 17.8 | 19.2 | 20.9 | 19.0 | 19.7 | 23.0 | 22.9 | 23.0 | 24.8 | 25.5 | 26.0 | 27.0 | 26.0 | 0.45 (0.35 to 0.55) |

| Nondisordered | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol use | 40.4 | 42.9 | 41.6 | 42.4 | 43.2 | 42.4 | 40.2 | 40.7 | 40.6 | 38.0 | 38.0 | 38.5 | 36.8 | 37.1 | 35.7 | 34.6 | 34.3 | −0.52 (−0.61 to −0.44) |

| Marijuana use | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.10) |

| Co-use | 17.1 | 16.9 | 16.1 | 15.6 | 16.3 | 16.0 | 17.0 | 19.9 | 18.5 | 19.9 | 19.8 | 21.3 | 21.2 | 21.4 | 23.6 | 24.3 | 24.0 | 0.60 (0.51 to 0.68) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 16.6 | 15.4 | 15.3 | 16.2 | 16.7 | 16.1 | 15.1 | 13.7 | 14.6 | 12.8 | 12.0 | 10.7 | 11.0 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 7.9 | −0.55 (−0.62 to −0.48) |

| Marijuana use disorder | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.10) |

| Disordered co-use | 3.1 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.0 | −0.11 (−0.14 to −0.09) |

| Marijuana and alcohol: non–college students | ||||||||||||||||||

| Abstinence of both | 22.3 | 22.7 | 22.4 | 24.0 | 24.1 | 23.8 | 23.0 | 21.6 | 22.8 | 24.1 | 22.6 | 23.8 | 22.6 | 24.6 | 27.1 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 0.22 (0.14 to 0.31) |

| Nondisordered | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol use | 37.0 | 38.3 | 38.5 | 38.2 | 38.5 | 39.3 | 40.5 | 37.8 | 38.6 | 37.3 | 37.2 | 37.6 | 36.4 | 36.8 | 33.0 | 34.2 | 33.4 | −0.31 (−0.41 to −0.22) |

| Marijuana use | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 0.10 (0.07 to 0.13) |

| Co-use | 17.0 | 17.3 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 15.1 | 19.1 | 17.8 | 18.4 | 20.2 | 20.7 | 22.7 | 22.5 | 22.7 | 23.8 | 23.0 | 0.56 (0.48 to 0.63) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 15.0 | 12.9 | 14.4 | 14.1 | 13.4 | 15.1 | 13.2 | 13.6 | 12.9 | 10.9 | 12.0 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 8.1 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 6.9 | −0.47 (−0.53 to −0.41) |

| Marijuana use disorder | 3.3 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.09) |

| Disordered co-use | 4.2 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.4 | −0.14 (−0.18 to −0.11) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Data from the US Department of Health and Human Services.30

The past-year abstinence from marijuana use decreased for both college students (0.41%; 95% CI, 0.31%-0.51%) and non–college students (0.41%; 95% CI, 0.31%-0.51%) from 2002 to 2018. The past-year prevalence of nondisordered marijuana use increased for both college students (0.46%; 95% CI, 0.37%-0.55%) and non–college students (0.49%; 95% CI, 0.40%-0.59%) from 2002 to 2018. Past-year marijuana use disorder held relatively steady for college students and non–college students from 2002 to 2018.

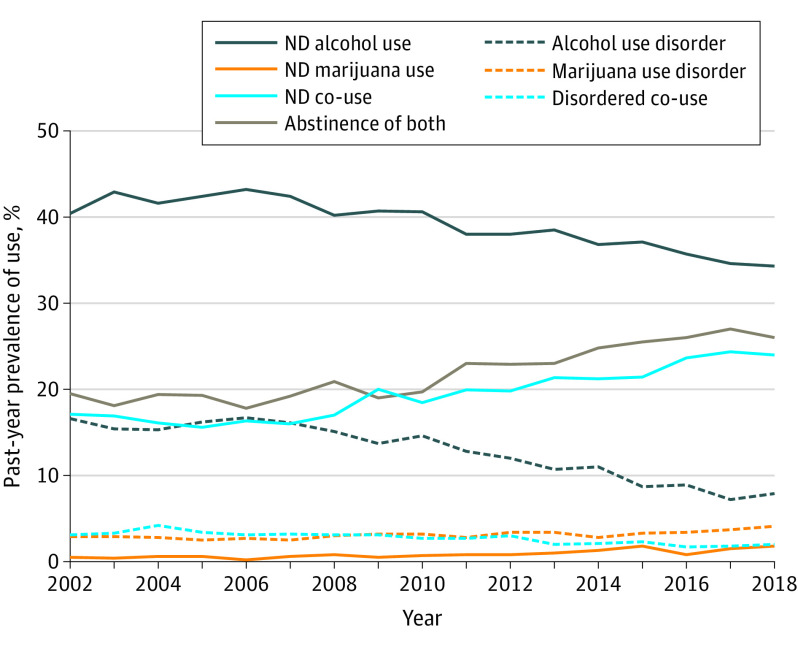

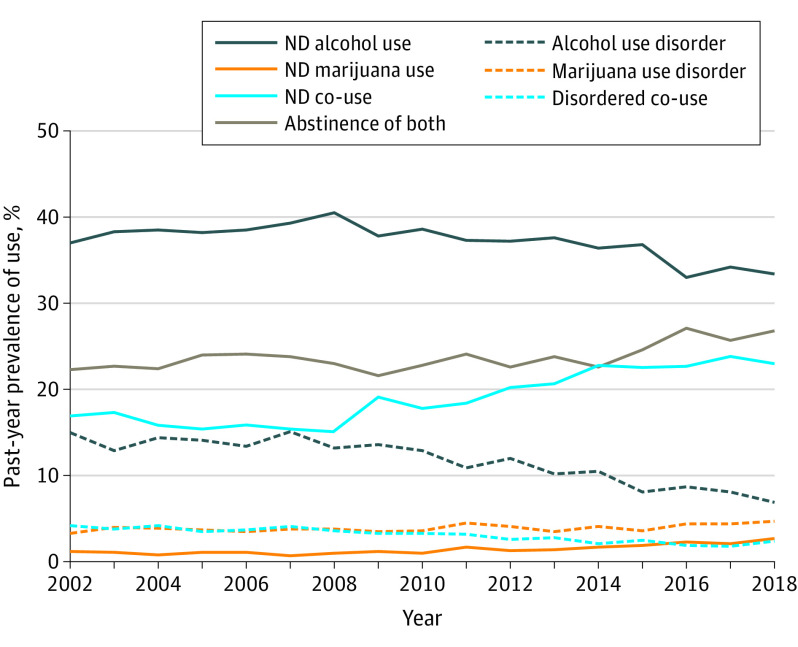

As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, college students and non–college students both experienced increases in abstinence of marijuana and alcohol. Past-year nondisordered co-use of alcohol and marijuana increased annually by similar amounts in college students (0.60%; 95% CI, 0.51%-0.68%) and non–college students (0.56%; 95% CI, 0.48%-0.63%).

Figure 1. Prevalence of Alcohol and Marijuana Use Groups in US College Students: 2002-2018.

ND indicates nondisordered.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Alcohol and Marijuana Use Groups in US Non–College Students: 2002-2018.

ND indicates nondisordered.

Per Table 2,30 all alcohol and/or marijuana use groups had higher rates of controlled prescription drug use, prescription drug misuse, prescription drug use disorder, illicit drug use, and illicit drug use disorder than abstinent (ie, alcohol and marijuana) respondents. For prescription drug use disorder and illicit drug use disorder, the nondisordered alcohol use and abstinent groups did not differ significantly. Most of those with both alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder reported past-year prescription drug misuse and past-year illicit drug use. Among young adults with both alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder, the prevalence of all 3 prescription drug outcomes and illicit drug use was higher among college students, while the prevalence of illicit drug use disorder was higher among non–college students. As presented in eTable 2 in the Supplement, young adults who reported co-use or met criteria for alcohol use disorder and/or marijuana use disorder accounted for 82.9% of young adults with prescription drug use disorders and 85.1% of young adults with illicit drug use disorders.

Table 2. Prescription and Illicit Drug Use by Abstinence, Nondisordered Use, and Disordered Use, 2015-2018a,b.

| Variable | Unweighted sample size, No. | Past-year, weighted % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescription drug | Other illicit drug | |||||

| Any use | Any misuse | Use disorder | Use | Use disorder | ||

| Alcohol and marijuana: college students | ||||||

| Abstinence of both | 3739 | 23.6 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 0.3 |

| Nondisordered | ||||||

| Alcohol use | 5388 | 33.4 | 6.0 | 0.2 | 7.2 | 0.3 |

| Marijuana use | 209 | 42.8 | 10.9 | 0.4 | 16.0 | 1.3 |

| Co-use | 3378 | 52.3 | 25.5 | 1.1 | 35.1 | 1.9 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1231 | 63.9 | 38.3 | 4.4 | 47.7 | 6.7 |

| Marijuana use disorder | 497 | 72.9 | 47.7 | 4.6 | 63.7 | 6.0 |

| Disordered co-use | 268 | 82.1 | 66.1 | 19.4 | 80.9 | 23.2 |

| Alcohol and marijuana: non–college students | ||||||

| Abstinence of both | 3988 | 25.7 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 0.6 |

| Nondisordered | ||||||

| Alcohol use | 5269 | 36.2 | 6.3 | 0.6 | 8.0 | 0.9 |

| Marijuana use | 375 | 36.6 | 16.1 | 3.6 | 22.2 | 4.8 |

| Co-use | 3397 | 51.6 | 25.0 | 2.3 | 36.4 | 4.6 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1233 | 62.9 | 38.0 | 6.3 | 47.6 | 10.6 |

| Marijuana use disorder | 652 | 60.1 | 39.0 | 7.5 | 53.9 | 13.1 |

| Disordered co-use | 324 | 76.1 | 58.7 | 19.2 | 75.8 | 30.6 |

| Alcohol and marijuana: overall | ||||||

| Abstinence of both | 7727 | 24.6 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 0.5 |

| Nondisordered | ||||||

| Alcohol use | 10 657 | 34.3 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 7.5 | 0.6 |

| Marijuana use | 584 | 37.8 | 12.6 | 2.1 | 17.4 | 3.1 |

| Co-use | 6775 | 51.8 | 25.1 | 1.8 | 35.4 | 3.3 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 2464 | 63.5 | 38.2 | 5.5 | 47.7 | 8.8 |

| Marijuana use disorder | 1149 | 66.4 | 43.2 | 5.7 | 58.2 | 9.4 |

| Disordered co-use | 592 | 78.2 | 62.2 | 19.3 | 77.7 | 27.9 |

All comparisons are within column, with abstinence as the reference group. Prescription drug refers to prescription opioids, prescription stimulants, and/or prescription sedatives/tranquilizers/anxiolytics. Other illicit drug use refers to heroin, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, and methamphetamine.

Data from the US Department of Health and Human Services.30

As reported in Table 3,30 the most consistent covariates across all of the outcomes were prescription drug misuse and illicit drug use. For instance, young adults who had engaged in prescription drug misuse had more than 2 times greater odds of marijuana use disorder than young adults who had not engaged in prescription drug misuse (college: 2.28; 95% CI, 1.71-3.03; non-college: 2.04; 95% CI, 1.62-2.58). Similarly, young adults who reported illicit drug use had over 4 times greater odds of marijuana use disorder than young adults who did not report illicit drug use (college: 5.09; 95% CI, 3.86-6.70; non-college: 4.41; 95% CI, 3.48-5.60). Prescription drug use was associated with lower odds of abstinence (college: 0.60; 95% CI, 0.52-0.70; non-college: 0.65; 95% CI, 0.56-0.75) and increased odds of nondisordered co-use (college: 1.41; 95% CI, 1.22-1.63; non-college: 1.32; 95% CI, 1.14-1.52) and marijuana use disorder (college: 1.85; 95% CI, 1.42-2.41) among young adults, except marijuana use disorder for non–college students. In contrast, religiosity was related to higher odds of abstinence (college: 1.08; 95% CI, 1.06-1.10; non-college: 1.04; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06) and lower odds of nondisordered co-use (college: 0.92; 95% CI, 0.90-0.93; non-college: 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92-0.95) and marijuana use disorder (college: 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99) among young adults, except marijuana use disorder for non–college students. We found sex differences in marijuana use disorder for both college students (1.94; 95% CI, 1.57-2.41) and non–college students (2.20; 95% CI, 1.80-2.71), with men in each group having approximately 2 times higher odds of marijuana use disorder.

Table 3. Multivariable Results: Past-Year Abstinence, Co-Use, and Marijuana Use Disorder, 2015-2018a,b.

| Variable | AOR (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol and marijuana abstinence | Alcohol and marijuana co-use | Marijuana use disorder | ||||||

| College students | Non–college students | College students | Non–college students | College students | Non–college students | |||

| Unweighted sample size, No. | 12 762 | 14 268 | 12 762 | 14 268 | 12 762 | 14 268 | ||

| Sociodemographic covariates | ||||||||

| Male | 1.21 (1.11-1.33) | 1.07 (0.95-1.21) | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) | 1.01 (0.88-1.15) | 1.94 (1.57-2.41) | 2.20 (1.80-2.71) | ||

| White | 0.60 (0.54-0.67) | 0.71 (0.63-0.80) | 1.14 (0.99-1.30) | 0.98 (0.87-1.10) | 0.80 (0.62-1.03) | 0.59 (0.48-0.72) | ||

| Poverty | 0.79 (0.68-0.91) | 1.55 (1.37-1.76) | 1.22 (1.09-1.37) | 0.97 (0.84-1.11) | 1.06 (0.82-1.36) | 0.98 (0.79-1.22) | ||

| CBSA >1 million | 1.12 (0.99-1.25) | 0.86 (0.77-0.97) | 1.08 (0.98-1.20) | 1.13 (1.04-1.24) | 0.96 (0.77-1.18) | 1.13 (0.91-1.39) | ||

| Religiosity | 1.08 (1.06-1.10) | 1.04 (1.03-1.06) | 0.92 (0.90-0.93) | 0.94 (0.92-0.95) | 0.97 (0.94-0.99) | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | ||

| Lesbian/gay | 1.21 (0.76-1.91) | 0.58 (0.38-0.90) | 1.42 (1.03-1.97) | 1.41 (1.03-1.93) | 0.87 (0.53-1.43) | 0.82 (0.49-1.36) | ||

| Bisexual | 1.03 (0.79-1.36) | 0.82 (0.68-1.00) | 1.17 (0.98-1.40) | 1.44 (1.19-1.75) | 1.02 (0.67-1.55) | 1.17 (0.86-1.61) | ||

| Physical health covariates | ||||||||

| Self-reported fair or poor health | 1.21 (0.90-1.64) | 1.18 (0.94-1.49) | 0.93 (0.68-1.25) | 0.99 (0.82-1.20) | 1.24 (0.73-2.12) | 1.20 (0.94-1.53) | ||

| Overweight/obese BMI | 0.93 (0.82-1.05) | 1.07 (0.98-1.18) | 0.93 (0.83-1.05) | 0.88 (0.78-0.98) | 1.03 (0.82-1.30) | 0.78 (0.64-0.96) | ||

| Past-year hospitalization | 1.44 (1.11-1.88) | 1.58 (1.34-1.85) | 0.87 (0.65-1.16) | 0.69 (0.54-0.87) | 1.01 (0.68-1.61) | 1.01 (0.71-1.44) | ||

| Mental health covariates, past year | ||||||||

| Mental health treatment | 1.19 (1.02-1.40) | 1.10 (0.96-1.26) | 0.98 (0.80-1.18) | 0.97 (0.82-1.15) | 1.33 (1.01-1.76) | 1.13 (0.86-1.50) | ||

| Major depression | 1.27 (1.01-1.61) | 1.28 (1.03-1.60) | 0.92 (0.75-1.14) | 1.12 (0.89-1.40) | 0.95 (0.70-1.29) | 1.15 (0.83-1.60) | ||

| Psychological distress | 0.79 (0.67-0.93) | 1.06 (0.87-1.28) | 0.98 (0.79-1.21) | 0.81 (0.69-0.95) | 1.46 (1.09-1.97) | 1.50 (1.16-1.93) | ||

| WHO disability scale | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 1.05 (1.02-1.07) | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | ||

| Suicidal ideation | 0.93 (0.76-1.12) | 0.85 (0.68-1.07) | 0.92 (0.75-1.12) | 1.09 (0.86-1.38) | 1.14 (0.86-1.51) | 1.41 (1.07-1.86) | ||

| Substance use covariates, past year | ||||||||

| Prescription drug use | 0.60 (0.52-0.70) | 0.65 (0.56-0.75) | 1.41 (1.22-1.63) | 1.32 (1.14-1.52) | 1.85 (1.42-2.41) | 1.14 (0.91-1.43) | ||

| Prescription drug misuse | 0.21 (0.15-0.31) | 0.34 (0.25-0.47) | 1.53 (1.27-1.83) | 1.40 (1.18-1.65) | 2.28 (1.71-3.03) | 2.04 (1.62-2.58) | ||

| Other illicit drug use | 0.08 (0.04-0.15) | 0.11 (0.08-0.17) | 1.86 (1.60-2.17) | 2.14 (1.88-2.44) | 5.09 (3.86-6.70) | 4.41 (3.48-5.60) | ||

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CBSA, US Census core-based statistical area; WHO, World Health Organization.

Prescription drug refers to prescription opioids, prescription stimulants, and/or prescription sedatives/tranquilizers/anxiolytics. Other illicit drug use refers to heroin, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, and methamphetamine.

Data from the US Department of Health and Human Services.30

Discussion

Past-year abstinence from alcohol was more prevalent among non–college students in the early 2000s relative to college students; however, this gap has closed in recent years. More than 1 in every 4 (28%) college students in the US were abstinent from alcohol use, or approximately 3 000 000 US college students in 2018. We found that increases in alcohol abstinence were accompanied by decreases in alcohol use disorder among college and non–college students. These changes may be influenced by increases in the number of US young adults living with their parents,10,31,32 which could promote increased alcohol abstinence and decreased alcohol use disorder as found in the present study. These changes may also be an example of the prevention paradox, where upstream interventions aimed at low- to moderate-risk drinking populations more substantially address overall drinking-related problems in young adults than interventions solely for high-risk groups.33,34 Perhaps increased alcohol prevention and intervention efforts targeting US college students33,35,36,37 substantially addressed drinking-related problems among this low- to moderate-risk group.

There was an increase in nondisordered marijuana use from 2002 to 2018 without an increase in marijuana use disorder among US young adults. This finding is consistent with earlier changes reported in the US population, indicating an increase of 19% in the annual past-year prevalence of marijuana use between 2002 and 2013 without an increase in marijuana use disorder.38 Nevertheless, the trends in marijuana use and marijuana use disorder remain important to monitor both cross-sectionally and prospectively given that marijuana use among US young adults has reached its highest level in several decades.39

Nondisordered co-use of alcohol and marijuana increased between 2002 and 2018 among US young adults. For example, approximately 2.6 million college students co-used alcohol and marijuana in 2018, as opposed to approximately 1.8 million college students in 2002. Those engaging in simultaneous use of alcohol and marijuana (ie, use of both substances on the same occasion) tend to use both substances more frequently, use greater quantities, and experience more substance-related consequences.40 Although alcohol use disorder is declining and alcohol abstinence is increasing in parallel, the legal landscape of marijuana is changing and the percentage of tetrahydrocannabinol in marijuana strains has steadily increased in recent decades,41 with evidence of an increase in risk related to development of symptomatic marijuana use,42 marijuana use disorder severity,43 and psychosis.44,45 Therefore, clinicians and physicians have a complex task in developing effective programs to reduce the risk of negative consequences associated with the rising prevalence of marijuana use and co-use of alcohol and marijuana. In addition, schools and employers may require additional resources to scale interventions to address both individuals with and without a disorder, including brief interventions for nondisordered co-use of alcohol and marijuana.

More than three-fourths of young adults who met criteria for both alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder reported past-year prescription drug use (78.2%) and illicit drug use (77.7%); 62.2% reported prescription drug misuse. Prescription drug misuse is more prevalent among young adults than any other age group in the US.39,46,47 Young adults who reported co-use of alcohol and marijuana or met criteria for alcohol use disorder and/or marijuana use disorder accounted for 82.9% of young adults with prescription drug use disorder and 85.1% of those with illicit drug use disorder. Current national studies and diagnostic instruments often focus on individual drug classes and can miss changes in co-use as suggested by the present study. This assessment gap impacts prevention and intervention efforts because an individual may not be considered at risk based on any single substance; however, the same individual could be at risk for dangerous drug interactions (eg, combining central nervous system depressants). Therefore, clinicians are encouraged to screen for a wide range of substances and polysubstance use to detect risky use behaviors. Similarly, the high prevalence of prescription drug use among young adults who report co-use of alcohol and marijuana or met criteria for alcohol use disorder and/or marijuana use disorder reinforces the importance of carefully monitoring use of controlled substances among such individuals.

Limitations

The results of the present study should be considered within the context of its limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the NSDUH precludes any causal determinations regarding the temporal associations between substance use and educational status. Second, all measures were self-reported and, although all measures are considered reliable and valid, studies suggest that misclassification and underreporting of sensitive behaviors such as substance use can occur.48,49 Also, we combined illicit drugs and additional research is needed that considers individual drugs to help detect emerging drug patterns (eg, methamphetamine and heroin), including co-use. While we adjusted for relevant sociodemographic characteristics associated with college enrollment and substance use, the secondary analyses were limited to the available variables, and other factors that may influence the associations could not be included (eg, social context and substance availability). In addition, the present study was constrained by the NSDUH measures, such as the DSM-IV criteria used to determine SUD, and further work is needed to examine the trends in DSM-5-classified alcohol use disorder and marijuana use disorder among US young adults.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that greater attention is needed to provide a diverse set of social support services and resources to the growing number of US young adults in college and not in college who are abstinent from alcohol, including those in recovery and those abstinent for other reasons. In addition, screening for co-use of alcohol and marijuana, alcohol use disorder, and marijuana use disorder provide opportunities for clinicians to detect illicit drug use, prescription drug misuse, and other SUDs. Colleges and communities in the US must find ways to address the changing landscape of substance use behaviors by providing support to the increasing number of young adults who are abstinent, while also creating interventions to address the increases in marijuana use and co-use of alcohol and marijuana.

eTable 1. Trends in Demographic Characteristics Among US Young Adults Aged 18-22 Years Old: 2002-2018

eTable 2. Cumulative Percentage of Prescription and Illicit Drug Use as a Function of Alcohol or Marijuana Involvement in US Young Adults: 2015-2018

References

- 1.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. . Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, et al. . Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(1):39-47. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Published 2019. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2018-nsduh-detailed-tables

- 4.Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, Patrick ME Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2016: volume II, college students and adults ages 19-55. Institute for Social Research: The University of Michigan; 2019. Accessed October 15, 2019. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2016.pdf

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Multiple causes of death 1999-2017 on CDC wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (CDC Wonder). CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. Published 2018. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/mcd.html

- 6.Hall WD, Patton G, Stockings E, et al. . Why young people’s substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):265-279. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00013-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe SE, Veliz PT, Boyd CJ, Schepis TS, McCabe VV, Schulenberg JE. A prospective study of nonmedical use of prescription opioids during adolescence and subsequent substance use disorder symptoms in early midlife. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:377-385. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. J Drug Issues. 2005;35:235-254. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002;(14):54-70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(4):477-488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grucza RA, Norberg KE, Bierut LJ. Binge drinking among youths and young adults in the United States: 1979-2006. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(7):692-702. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a2b32f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schepis TS, Teter CJ, McCabe SE. Prescription drug use, misuse and related substance use disorder symptoms vary by educational status and attainment in US adolescents and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;189:172-177. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arterberry BJ, Boyd CJ, West BT, Schepis TS, McCabe SE. DSM-5 substance use disorders among college-age young adults in the United States: prevalence, remission and treatment. J Am Coll Health. 2019;1-8. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1590368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford JA, Pomykacz C. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants: a comparison of college students and their same-age peers who do not attend college. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2016;48(4):253-260. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2016.1213471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martins SS, Kim JH, Chen LY, et al. . Nonmedical prescription drug use among US young adults by educational attainment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(5):713-724. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0980-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among US college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(3):263-270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993-2001. J Am Coll Health. 2002;50(5):203-217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohler-Kuo M, Lee JE, Wechsler H. Trends in marijuana and other illicit drug use among college students: results from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993-2001. J Am Coll Health. 2003;52(1):17-24. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. SMA 18-5068, NSDUH Series H-53. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Published 2018. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.htm

- 20.Connor JP, Gullo MJ, White A, Kelly AB. Polysubstance use: diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(4):269-275. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy S, Campbell MD, Shea CL, DuPont R. Trends in abstaining from substance use in adolescents: 1975-2014. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20173498. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, DuPont RL. National trends in substance use and use disorders among youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(9):747-754.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaughn MG, Nelson EJ, Oh S, Salas-Wright CP, DeLisi M, Holzer KJ. Abstention from drug use and delinquency increasing among youth in the United States, 2002-2014. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(9):1468-1481. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1413392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: methodological summary and definitions. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Published September 2015. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs2014/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs2014.htm

- 25.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: methodological summary and definitions. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Published September 2018. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHMethodSummDefs2017/NSDUHMethodSummDefs2017.htm

- 26.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan BK, Karg RS, Batts KR, Epstein JF, Wiesen C. A clinical validation of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health assessment of substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2008;33(6):782-798. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Reliability of key measures in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Office of Applied Studies, Methodology Series M-8, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4425. Published 2010. Accessed October 15, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2k6ReliabilityP/2k6ReliabilityP.pdf [PubMed]

- 29.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of the effects of the 2015 NSDUH questionnaire redesign: implications for data users. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Published June 2016. Accessed October 19, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-TrendBreak-2015.pdf [PubMed]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2019. National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2002-2018 (NSDUH-2002-2018-DS0001). Accessed January 6, 2020. https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

- 31.Vespa J. The Changing Economics and Demographics of Young Adulthood: 1975–2016. Current Population Reports, P20-579. US Census Bureau; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gfroerer JC, Greenblatt JC, Wright DA. Substance use in the US college-age population: differences according to educational status and living arrangement. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(1):62-65. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.1.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gruenewald PJ, Johnson FW, Light JM, Lipton R, Saltz RF. Understanding college drinking: assessing dose response from survey self-reports. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(4):500-514. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skog OJ. The prevention paradox revisited. Addiction. 1999;94(5):751-757. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94575113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cronce JM, Toomey TL, Lenk K, Nelson TF, Kilmer JR, Larimer ME. NIAAA’s college alcohol intervention matrix. Alcohol Res. 2018;39(1):43-47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dejong W, Larimer ME, Wood MD, Hartman R. NIAAA’s rapid response to college drinking problems initiative: reinforcing the use of evidence-based approaches in college alcohol prevention. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;(16):5-11. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saltz RF. Environmental approaches to prevention in college settings. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(2):204-209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grucza RA, Agrawal A, Krauss MJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Bierut LJ. Recent trends in the prevalence of marijuana use and associated disorders in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):300-301. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, Patrick ME Monitoring the future: national survey results on drug use, 1975-2017: volume II, college students and adults ages 19-55. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Published July 2018. Accessed October 19, 2019. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2017.pdf

- 40.Yurasek AM, Aston ER, Metrik J. Co-use of alcohol and cannabis: a review. Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4(2):184-193. doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0149-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ElSohly MA, Mehmedic Z, Foster S, Gon C, Chandra S, Church JC. Changes in cannabis potency over the last 2 decades (1995–2014): analysis of current data in the United States. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(7):613-619. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arterberry BJ, Treloar Padovano H, Foster KT, Zucker RA, Hicks BM. Higher average potency across the United States is associated with progression to first cannabis use disorder symptom. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;195:186-192. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeman TP, Winstock AR. Examining the profile of high-potency cannabis and its association with severity of cannabis dependence. Psychol Med. 2015;45(15):3181-3189. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Forti M, Morgan C, Dazzan P, et al. . High-potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):488-491. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.064220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Forti M, Sallis H, Allegri F, et al. . Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6):1509-1517. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hughes A, Williams M, Lipari RN, Bose J, Copello EA, Kroutil LA Prescription drug use and misuse in the United States: results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review. Published September 2016. Accessed October 19, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR2-2015/NSDUH-FFR2-2015.htm

- 47.McCabe SE, Wilens TE, Boyd CJ, Chua KP, Voepel-Lewis T, Schepis TS. Age-specific risk of substance use disorders associated with controlled medication use and misuse subtypes in the United States. Addict Behav. 2019;90:285-293. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Chien S. Measurement of adolescent drug use. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(3):301-309. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parra GR, O’Neill SE, Sher KJ. Reliability of self-reported age of substance involvement onset. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(3):211-218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Trends in Demographic Characteristics Among US Young Adults Aged 18-22 Years Old: 2002-2018

eTable 2. Cumulative Percentage of Prescription and Illicit Drug Use as a Function of Alcohol or Marijuana Involvement in US Young Adults: 2015-2018