Abstract

Introduction

Cigarette use is associated with substance use and mental health problems among youth, but associations are unknown for non-cigarette tobacco product use, as well as the increasingly common poly-tobacco use.

Methods

The current study examined co-occurrence of substance use and mental health problems across tobacco products among 13,617 youth aged 12–17 years from Wav 1 (2013–2014) of the nationally representative Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Participants self-reported ever cigarette, e-cigarette, smokeless tobacco, traditional cigar, cigarillo, filtered cigar, hookah, and other tobacco product use; alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs; and lifetime substance use, internalizing and externalizing problems.

Results

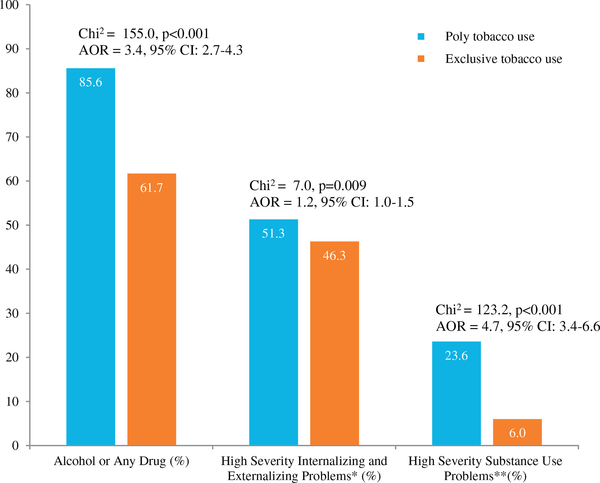

In multivariable regression analyses, use of each tobacco product was associated with substance use, particularly cigarillos and marijuana (AOR = 18.9, 95% CI: 15.3–23.4). Cigarette (AOR = 14.7, 95% CI: 11.8–18.2) and cigarillo (AOR = 8.1, 95% CI: 6.3–10.3) use were strongly associated with substance use problems and tobacco users were more likely to report internalizing (AOR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.4–1.8) and externalizing (AOR = 1.4, 95% CI: 1.3–1.6) problems. Female tobacco users were more likely to have internalizing problems than male tobacco users. Poly-tobacco users were more likely than exclusive users to use substances (AOR = 3.4, 95% CI: 2.7–4.3) and have mental health (AOR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.0–1.5) and substance use (AOR = 4.7, 95% CI: 3.4–6.6) problems.

Conclusions

Regardless of the tobacco product used, findings reveal high co-occurrence of substance use and mental health problems among youth tobacco users, especially poly-tobacco users. These findings suggest the need to address comorbidities among high risk youth in prevention and treatment settings.

Keywords: Adolescent, Tobacco, Cannabis, Mental health, Epidemiologic studies

1. Introduction

Although cigarette smoking has continually declined in the United States, cigarette use remains common among youth (Arrazola et al., 2015). Furthermore, national surveys show that use of non-cigarette products such as e-cigarettes, hookah, little cigars, and smokeless tobacco has become increasingly common (Arrazola et al., 2015; Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2017; Kasza et al., 2017; Y. O. Lee, Hebert, Nonnemaker, & Kim, 2015). Previous research has found consistent associations with certain tobacco products (especially cigarettes), alcohol or drugs, and mental health problems among U.S. youth. No study to date has examined these associations across tobacco products, addictive substances, and internalizing and externalizing mental health problems in a nationally representative sample. Moreover, approximately four in ten current tobacco users report using two or more products (Kasza et al., 2017), but scant research has examined the role of poly-tobacco use in these associations.

While available research suggests that the strong association between cigarette use and substance use may extend across specific substances (Richter, Pugh, Smith, & Ball, 2017), this has never been examined in a systematic and comprehensive manner (Kandel, Yamaguchi, & Chen, 1992). This literature is limited not only by a narrow focus on alcohol and marijuana, but few studies focus on emerging tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes, cigar types and hookah, that are commonly used by American youth (Kasza et al., 2017). Additionally, a 2012 review found high co-occurrence of tobacco (mostly cigarettes) and marijuana among youth and young adults in the majority of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies examined (Ramo, Liu, & Prochaska, 2012). Other recent studies show that hookah (water pipe) use is similarly associated with greater marijuana use among U.S. high school seniors and college students (Goodwin et al., 2014; Palamar, Zhou, Sherman, & Weitzman, 2014). Emerging research on e-cigarettes has documented an association between e-cigarette use and use of alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit substances (Demissie, Everett Jones, Clayton, & King, 2017; Westling, Rusby, Crowley, & Light, 2017), although much of this research compares e-cigarette use to cigarette use or dual use of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes (Dunbar et al., 2017; Kristjansson, Mann, & Smith, 2017; McCabe, West, Veliz, & Boyd, 2017).

Similarly, the assessment of the association between youth tobacco use and mental health problems is generally limited to cigarette smoking. Studies suggest a positive association between youth tobacco use and internalizing problems including depressive symptoms (Lechner, Janssen, Kahler, Audrain-McGovern, & Leventhal, 2017; Leventhal et al., 2016; Mistry, Babu, Mahapatra, & McCarthy, 2014; Tercyak & Audrain, 2002) and anxiety (Marmorstein et al., 2010; Marmorstein, White, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2010; Zehe, Colder, Read, Wieczorek, & Lengua, 2013). Youth cigarette smoking has also been associated with externalizing disorders involving disruptive behavior, including conduct disorder (Armstrong & Costello, 2002; Colder et al., 2013; Leventhal et al., 2016; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on and Smoking Health, 2012), oppositional defiant disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Brinkman, Epstein, Auinger, Tamm, & Froehlich, 2015; Elkins, McGue, & Iacono, 2007; Groenman et al., 2013; S. S. Lee, Humphreys, Flory, Liu, & Glass, 2011). Moreover, although two nationally representative studies found that youth poly-tobacco use was associated with alcohol, marijuana, and other drug disorders (Cavazos-Rehg, Krauss, Spitznagel, Grucza, & Bierut, 2014; Richter, Pugh, Smith, & Ball, 2017), these did not focus on co-occurring mental health problems.

Examining these associations across the full range of tobacco products used by American adolescents, a high-risk population for the onset and exacerbation of tobacco use, substance use, and mental health problems (Office of the Surgeon General, 2016; Robinson & Riggs, 2016), is essential. Therefore, using Wave 1 data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, the present study examined co-occurrence of substance use, substance use problems, and mental health (internalizing and externalizing) problems across 12 tobacco products. This study further examined these associations by poly-tobacco use.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

The PATH Study is a nationally representative longitudinal study of 45,971 U.S. adults (18 years and older) and youth (12–17 years) designed to examine tobacco use and health. This paper reports Wave 1 (September 2013–December 2014) data from 13,617 youth participants with complete data on variables for the specific associations examined. Participants were recruited via an address-based, area-probability sampling approach, using an in-person household screener to select youth from households that oversampled adult tobacco users, young adults, and African-American adults. Generally, up to two youth were sampled per household. The weighting procedures adjusted for oversampling and nonresponse, allowing estimates to be representative of the non-institutionalized, civilian U.S. population. The weighted response rate among sampled youth was 78.4%.

After obtaining consent from parents and emancipated youth and assent from youth, data were collected using Audio-Computer Assisted Self-Interviews administered in English or Spanish. Detailed methodological information about the study design and protocol is available elsewhere (Hyland et al., 2017) and at http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NAHDAP/series/606. The study was conducted by Westat and approved by Westat’s Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Tobacco use

Ever use of tobacco products was determined based on participants’ responses to questions on lifetime use (dichotomized as no = 0, yes = 1) of the following: cigarettes, e-cigarettes, traditional cigars, cigarillos, filtered cigars, pipe, hookah, smokeless tobacco (i.e. loose snus, moist snuff, dip, spit, or chewing tobacco), snus pouches, kreteks, bidis, and dissolvable tobacco. A brief description and pictures of each product (except cigarettes) were shown to participants before being asked about the products. Additional questions were asked of cigar users to determine cigar type.

‘Any tobacco use’ was defined as ever using any tobacco product, ‘any cigar use’ was defined as ever using traditional cigars, cigarillos, or filtered cigars, and ‘smokeless including snus’ was defined as ever using smokeless tobacco or snus pouches. Among tobacco users, ‘poly-use’ of any tobacco was defined as ever use of any two or more of the following 8 tobacco product categories: cigarettes, e-cigarettes, any cigar, pipe, hookah, any type of smokeless tobacco (i.e., smokeless tobacco, snus pouches or dissolvable tobacco), kreteks, and bidis, versus exclusive use of any tobacco product, which was defined as ever use of only one of these 8 tobacco product categories. ‘Poly-use’ of cigarettes was defined as ever use of cigarettes and ever use of at least one of the other 7 tobacco product categories, versus exclusive use of cigarettes, which was defined as ever use of only cigarettes. ‘Poly-use’ of e-cigarettes was defined as ever use of e-cigarettes and ever use of at least one of the other 7 tobacco product categories, versus exclusive use of e-cigarettes, which was defined as ever use of only e-cigarettes. For each poly-use variable, complete data were required to categorize participants as exclusive users, but were not required to categorize participants as poly-users.

2.2.2. Substance use

Self-reported ever use was defined and dichotomized separately (no = 0, yes = 1) as lifetime use of each of the following: alcohol, marijuana (including blunts), misuse of prescription drugs (i.e. Ritalin® or Adderall®; painkillers, sedatives, or tranquilizers), and other drugs (cocaine or crack, stimulants (i.e. methamphetamine or speed), heroin, inhalants, solvents, and hallucinogens).

In addition, ever use of alcohol or any drug was defined as the lifetime use of any of the above substances (dichotomized as no = 0, yes = 1). Substance use items in the PATH Study were adapted from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (National Instiutes of Health (NIH); National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), 2004–2005) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), 2011–2012).

2.2.3. Substance use and mental health problems

Substance use and mental health problems were assessed via the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs - Short Screener (GAIN-SS), modified for the PATH Study (M. L. Dennis, Chan, & Funk, 2006). The GAIN-SS identifies individuals at risk for mental health or substance use disorders using a continuous measure of severity. Items for the GAIN-SS were derived from the full GAIN instrument, a validated, standardized biopsychosocial assessment for individuals entering treatment for substance use or mental health disorders (Garner, Belur, & Dennis, 2013) and recommended for use in epidemiological samples by the PhenX Toolkit (Hamilton et al., 2011). The PATH Study assessed severity across three subscales: substance use problems, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems. Table 1 displays the items and reliability (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011) for each subscale.

Table 1.

GAIN-SS items and reliability.

| GAIN-SS subscale | Items | Reliabilityf |

|---|---|---|

| Substance use problemsa,b | 1) Used alcohol or other drugs weekly or more often 2) Spent a lot of time getting alcohol or other drugsc 3) Spent a lot of time using or recoveringc 4) Alcohol or drugs causing social problems, fights, or trouble with others 5) Reduced involvement with activities at work, school, home, or social events 6) Withdrawal problemsc 7) Use of alcohol or other drugs to stop being sick or avoid withdrawal problemsc |

Lifetime = 0.85 Past year = 0.82 |

| Internalizing problemsa,d | 1) Feeling very trapped/sad/depressed 2) Trouble sleeping 3) Feeling nervous/anxious/tense/scared 4) Being distressed/upset about the past |

Lifetime = 0.81 Past year = 0.79 |

| Externalizing problemsa | 1) Hard time paying attention 2) Hard time listening to instructions 3) Lied/conned to get something 4) Bullied/threatened people 5) Started a physical fight 6) Felt restless/need to climb on thingse 7) Gave answers before question was finishede |

Lifetime = 0.77 Past year = 0.73 |

GAIN-SS: Global Appraisal of Individual Needs - Short Screener (GAIN-SS).

Symptoms were categorized into no/low (0–1 symptoms), moderate (2–3 symptoms), and high (4 symptoms for internalizing problems or ≥ 4 symptoms for substance use and externalizing problems) severity levels.

Those who had never used alcohol or drugs were coded as having ‘0’ symptoms

Items 2 and 3, as well as 6 and 7, were separated in the PATH Study.

A fifth suicide item was not included in the PATH Study.

Items 6 and 7 from the full GAIN Behavioral Complexity Scale were included in the PATH Study.

Cronbach’s α calculated for the PATH Study cutpoints.

The GAIN-SS measures problems across four time periods: past month, 2–12 months ago, over a year ago, and never. Given the relatively low proportions of youth substance use, the current study focused on lifetime measures to maximize stability of the estimates. The number of responses endorsed in the lifetime were summed for each subscale (complete data for subscale components were required). Summary scores ranged from 0 to 7 for substance use, 0–4 for internalizing, and 0–7 for externalizing problems. Based on the number of symptoms endorsed, participants were categorized into three severity levels: no/low (0–1 symptoms), moderate (2–3 symptoms), or high (4 for internalizing problems, or ≥ 4 symptoms for substance use and externalizing problems). These cut points were informed by previous studies showing concurrent and predictive validity in other samples (M. L. Dennis, et al., 2006; Garner, Belur, & Dennis, 2013). While individuals categorized as no/low severity are unlikely to have a diagnosis or need services, moderate severity indicates a possible diagnosis and need of services, and high severity indicates high likelihood of a disorder and need for services (M. Dennis, Feeney, Stevens, & Bedoya, 2006).

2.2.4. Covariates

Information was collected on socio-demographics characteristics including age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity. Sensation seeking, a risk factor for substance use (Hoyle, Stephenson, Palmgreen, Lorch, & Donohew, 2002), was assessed via three modified items from the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale: 1) “I like to do frightening things”, 2) “I like new and exciting experiences even if I have to break the rules”, and 3) “I prefer friends who are exciting and unpredictable” (Hoyle, Stephenson, Palmgreen, Lorch, & Donohew, 2002). Response options for each item (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree) were summed to create an overall score (range: 0–12) and mean score. The scale was found to be internally consistent in the PATH Study (Cronbach’s α = 0.76).

2.3. Analytic approach

Distributions of participants’ demographic characteristics, tobacco use, substance use, and substance use and mental health problems were examined. All variables (except sensation seeking) were categorized for analyses. For the aggregate variables (e.g. any tobacco use), complete data were required to categorize participants as non-users, but not required to categorize participants as users.

Multivariable logistic regression evaluated the associations between tobacco use and substance use, adjusting for socio-demographics (Office of the Surgeon General, 2016) and sensation seeking. Due to potential comorbidity between mental health problems and substance use (Armstrong & Costello, 2002; Kessler et al., 2012), a combined variable for lifetime mental health (internalizing and externalizing) problems categorized as low/moderate (0–7 symptoms) and high (8–11 symptoms) was also included in the substance use regression models. Multivariable logistic regression also modeled the odds of high versus low/moderate substance use, internalizing, and externalizing problems according to tobacco use, adjusting for socio-demographics and sensation seeking.

Distributions of alcohol or any drug use, the combined high severity internalizing and externalizing problem measure, and high severity substance use problems were also examined according to poly-tobacco use. Multivariable logistic regression modeled the odds of alcohol or any drug use according to poly-tobacco use, adjusting for socio-demographics, sensation seeking, and the combined variable for lifetime mental health problems. Multivariable logistic regression also modeled the odds of the combined high severity internalizing and externalizing problem measure, and high severity substance use problems measure, according to any poly-tobacco use, adjusting for socio-demographics and sensation seeking. More detailed analyses can be found in the supplement (see eTables 1 and 2).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by repeating all analyses using the complete-case method for handling missing data. Post hoc exploratory analyses were conducted to examine if gender moderated the associations between tobacco use and substance use, as well as tobacco use and substance use, internalizing, and externalizing problems.

Estimates were weighted to represent the U.S. youth population; variances and confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using the balanced repeated replication (BRR) method (McCarthy, 1969) with Fay’s adjustment set to 0.3 to increase estimate stability (Judkins, 1990). Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% CIs were calculated for all regression analyses. Two-sided p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Estimates based on fewer than 50 observations in the denominator or the relative standard error > 0.30 were suppressed (Klein, Proctor, Boudreault, & Turczyn, 2002). All analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 12 (StataCorp, 2011).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and other characteristics

Approximately half of youth were between 12 and 14 years of age (50.4%) and male (51.3%) (Table 2). A third (31.1%) reported ever use of alcohol or any drug; alcohol (21.8%) and marijuana (13.4%) were the most commonly used substances. The proportion of youth with high severity of lifetime substance use problems was relatively low (3.9%), while a larger proportion reported high severity of lifetime internalizing (33.8%) and externalizing (47.1%) problems. The sensation seeking score ranged from 0 to 4 (mean (standard error (SE)) = 1.6 (1.1)).

Table 2.

Demographic and other characteristics of PATH study wave 1 youth, 2013–2014.

| Participant characteristics | na | %b | SEb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 13,617 | 100.0 | – |

| Age (years)c | |||

| 12–14 | 6973 | 50.4 | 0.02 |

| 15–17 | 6642 | 49.6 | 0.02 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 6949 | 51.3 | 0.03 |

| Female | 6630 | 48.7 | 0.03 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 6463 | 54.6 | 0.07 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1798 | 13.7 | 0.06 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic | 70 | 0.4 | 0.07 |

| Asian/Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 392 | 4.7 | 0.07 |

| Multiple races, non-Hispanic | 767 | 4.2 | 0.08 |

| Hispanic | 3872 | 22.5 | 0.05 |

| Education (grade in school) | |||

| 5th grade or below | 76 | 0.5 | 0.07 |

| Middle school (grades 6–8) | 5123 | 37.9 | 0.23 |

| High school (grades 9–12) | 7853 | 59.6 | 0.24 |

| College, vocational/technical school | 106 | 0.8 | 0.09 |

| Not enrolled | 32 | 0.2 | 0.04 |

| Home-schooled | 112 | 0.8 | 0.09 |

| Ungradedd | 14 | 0.1 | 0.03 |

| Ever substance usee | |||

| Alcohol or any drug | 4137 | 31.1 | 0.52 |

| Alcohol | 2914 | 21.8 | 0.52 |

| Marijuana | 1837 | 13.4 | 0.40 |

| Ritalin/adderall | 333 | 2.5 | 0.13 |

| Painkillers/sedatives | 1087 | 8.0 | 0.23 |

| Other drugf | 219 | 1.6 | 0.13 |

| Lifetime substance use problemsg | |||

| No/low | 11,943 | 90.6 | 0.31 |

| Moderate | 742 | 5.6 | 0.23 |

| High | 530 | 3.9 | 0.21 |

| Lifetime internalizing problemsg | |||

| No/low | 4865 | 36.5 | 0.53 |

| Moderate | 3956 | 29.7 | 0.46 |

| High | 4491 | 33.8 | 0.57 |

| Lifetime externalizing problemsg | |||

| No/low | 3407 | 25.7 | 0.57 |

| Moderate | 3538 | 27.2 | 0.43 |

| High | 6087 | 47.1 | 0.58 |

| Sensation seeking scoreh | |||

| Mean (SE) | 13,366 | 1.6 | 1.10 |

Represents unweighted sample size (numbers may not sum to the total due to missing data).

Percentages (%) and standard errors (SE) are weighted to represent the US youth population (N = 24,791,293).

An age range between 12 and 17 years rather than a specific age was available for two participants.

School where students are not assigned to a particular grade.

Categories are not mutually exclusive (i.e. percentages do not sum to 100%).

Includes ever use of cocaine or crack, stimulants (i.e. methamphetamine or speed), or heroin, inhalants, solvents, or hallucinogens.

Lifetime substance use, internalizing and externalizing problems were assessed using the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs - Short Screener (GAIN-SS) and categorized as no/low (0–1 symptoms), moderate (2–3 symptoms), and high (4 symptoms for internalizing problems or ≥ 4 symptoms for substance use and externalizing problems) severity levels.

Assessed via three modified items from the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale.

3.2. Tobacco use and substance use

In multivariable analyses (Table 3), ever tobacco use was consistently associated with a higher odds of ever substance use across all tobacco products assessed. Tobacco users had nearly an 8-fold higher odds of alcohol or any drug use (95% CI: 6.7–8.6) when compared to non-users, after adjusting for socio-demographics, mental health problems, and sensation seeking. Across tobacco products, in comparison to non-users of the respective products, odds of marijuana use was 15-fold (95% CI: 12.4–17.2) for cigarettes, 10-fold for e-cigarettes (95% CI: 8.3–11.3), and 19-fold (95% CI: 15.3–23.4) for cigarillos. Associations across tobacco products with other drug use were also statistically significant and strong, with the strongest association at 19-fold (95% CI: 13.1–27.6) for cigarettes.

Table 3.

Ever substance use (%) among ever tobacco users (Y) and non-users (N), PATH study, 2013–2014.

| Alcohol or any drug | Specific alcohol or drug use |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol |

Marijuana |

Ritalin/adderall |

Painkillers/sedatives |

Other drugsa |

||||||||

| % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | |

| Any tobacco | ||||||||||||

| Y | 75.1 (0.97) | 7.6 (6.7–8.6) | 61.1 (0.97) | 6.5d (5.7–7.3) | 51.2 (1.38) | 17.8d (15.2–20.9) | 8.5 (0.57) | 6.3 (4.7–8.5) | 13.5 (0.71) | 1.5 (1.2–1.7) | 6.6 (0.54) | 22.3 (13.4–37.1) |

| N | 19.9 (0.47) | Referent | 12.5 (0.45) | Referent | 3.6 (0.20) | Referent | 0.8 (0.09) | Referent | 6.7 (0.26) | Referent | 0.2 (0.05) | Referent |

| Cigarettes | ||||||||||||

| Y | 80.1 (1.27) | 7.6 (6.4–9.1) | 65.8 (1.31) | 5.6d (4.8–6.5) | 60.8 (1.63) | 14.6d (12.4–17.2) | 10.6 (0.74) | 5.2d (4.1–6.7) | 16.0 (0.98) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 9.4 (0.76) | 19.0 (13.1–27.6) |

| N | 24.1 (0.49) | Referent | 16.0 (0.50) | Referent | 6.4 (0.28) | Referent | 1.2 (0.11) | Referent | 6.9 (0.24) | Referent | 0.3 (0.06) | Referent |

| E-cigarettes | ||||||||||||

| Y | 80.1 (1.15) | 7.0 (6.0–8.3) | 66.5 (1.25) | 5.4 (4.7–6.3) | 58.4 (1.32) | 9.7 (8.3–11.3) | 12.5 (0.97) | 6.0 (4.6–7.9) | 14.7 (1.06) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 9.6 (0.88) | 9.5 (6.8–13.4) |

| N | 25.9 (0.51) | Referent | 17.5 (0.51) | Referent | 8.4 (0.35) | Referent | 1.3 (0.10) | Referent | 7.4 (0.27) | Referent | 0.6 (0.08) | Referent |

| Any cigar | ||||||||||||

| Y | 89.0 (1.04) | 12.4 (9.8–15.5) | 74.7 (1.41) | 6.8d (5.6–8.3) | 73.6 (1.65) | 16.8 (13.9–20.3) | 14.2 (1.12) | 5.3d (4.0–7.2) | 17.3 (1.23) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 13.0 (1.34) | 13.8 (9.2–20.6) |

| N | 27.2 (0.51) | Referent | 18.8 (0.51) | Referent | 9.0 (0.33) | Referent | 1.5 (0.12) | Referent | 7.4 (0.26) | Referent | 0.6 (0.08) | Referent |

| Traditional cigars | ||||||||||||

| Y | 85.3 (1.95) | 7.1 (5.0–10.0) | 70.9 (3.05) | 4.1 (2.9–5.9) | 67.9 (3.16) | 8.0 (5.6–11.3) | 17.7 (2.40) | 4.2 (2.7–6.6) | 20.4 (2.43) | 2.2 (1.6–3.2) | 16.3 (2.39) | 7.2 (4.8–10.8) |

| N | 30.7 (0.55) | Referent | 21.9 (0.55) | Referent | 12.6 (0.41) | Referent | 2.1 (0.13) | Referent | 7.9 (0.26) | Referent | 1.2 (0.11) | Referent |

| Cigarillos | ||||||||||||

| Y | 89.9 (1.16) | 13.4 (10.2–17.7) | 74.8 (1.55) | 6.7d (5.4–8.3) | 76.7 (1.79) | 18.9 (15.3–23.4) | 15.2 (1.21) | 5.5d (4.1–7.4) | 17.7 (1.35) | 1.8 (1.5–2.3) | 14.3 (1.44) | 14.7 (10.0–21.7) |

| N | 27.8 (0.53) | Referent | 19.4 (0.53) | Referent | 9.5 (0.34) | Referent | 1.6 (0.12) | Referent | 7.4 (0.26) | Referent | 0.7 (0.08) | Referent |

| Filtered cigars | ||||||||||||

| Y | 92.3 (1.67) | 12.6 (7.7–20.5) | 82.2 (2.78) | 7.2 (4.7–11.1) | 78.8 (2.70) | 13.2 (9.2–19.1) | 19.2 (2.56) | 4.7 (3.1–7.1) | 23.9 (2.66) | 2.4 (1.8–3.3) | 19.3 (2.59) | 9.3 (6.0–14.2) |

| N | 30.5 (0.54) | Referent | 21.6 (0.54) | Referent | 12.4 (0.40) | Referent | 2.1 (0.13) | Referent | 7.7 (0.24) | Referent | 1.1 (0.11) | Referent |

| Pipe | ||||||||||||

| Y | 87.7 (2.23) | 10.0 (6.1–16.4) | 75.4 (3.32) | 6.1 (4.1–8.9) | 74.1 (3.03) | 12.4 (8.0–19.2) | 16.8 (2.84) | 3.9 (2.4–6.1) | 21.1 (2.99) | 2.2 (1.5–3.2) | 14.3 (2.64) | 5.5 (3.2–9.4) |

| N | 30.7 (0.53) | Referent | 21.8 (0.55) | Referent | 12.7 (0.41) | Referent | 2.2 (0.13) | Referent | 7.9 (0.24) | Referent | 1.3 (0.11) | Referent |

| Hookah | ||||||||||||

| Y | 84.6 (1.34) | 8.0 (6.5–9.9) | 71.4 (1.48) | 5.6d (4.7–6.7) | 65.5 (2.02) | 10.3 (8.5–12.6) | 12.5 (0.99) | 4.4 (3.4–5.8) | 17.0 (1.16) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 9.9 (1.17) | 6.7 (4.6–9.8) |

| N | 27.4 (0.51) | Referent | 18.8 (0.51) | Referent | 9.5 (0.35) | Referent | 1.6 (0.13) | Referent | 7.4 (0.24) | Referent | 0.9 (0.09) | Referent |

| Smokeless (including snus pouches) | ||||||||||||

| Y | 78.4 (2.12) | 5.9 (4.6–7.7) | 68.1 (2.39) | 5.2d (4.1–6.6) | 53.9 (2.82) | 6.1 (4.7–8.0) | 12.4 (1.52) | 3.7 (2.7–5.0) | 15.0 (1.56) | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 10.0 (1.50) | 5.4 (3.4–8.4) |

| N | 29.4 (0.51) | Referent | 20.5 (0.52) | Referent | 11.8 (0.39) | Referent | 2.0 (0.12) | Referent | 7.8 (0.25) | Referent | 1.1 (0.12) | Referent |

| Smokeless (excluding snus pouches) | ||||||||||||

| Y | 79.4 (2.12) | 6.1 (4.6–8.0) | 69.0 (2.39) | 5.3 (4.1–6.8) | 53.6 (2.81) | 5.7 (4.3–7.4) | 13.0 (1.65) | 3.8 (2.7–5.2) | 15.8 (1.68) | 1.8 (1.4–2.4) | 10.6 (1.57) | 5.6 (3.6–8.7) |

| N | 29.6 (0.52) | Referent | 20.7 (0.53) | Referent | 12.0 (0.40) | Referent | 2.0 (0.12) | Referent | 7.8 (0.25) | Referent | 1.2 (0.12) | Referent |

| Snus pouches | ||||||||||||

| Y | 81.1 (0.0366) | 5.8 (3.4–9.9) | 70.2 (4.21) | 4.5 (2.8–7.0) | 61.4 (4.24) | 6.6 (4.3–10.0) | 15.7 (2.95) | 3.6 (2.1–6.2) | 17.8 (2.70) | 2.0 (1.4–3.1) | 11.1 (2.50) | † |

| N | 31.0 (0.0052) | Referent | 22.0 (0.0053) | Referent | 13.0 (0.0040) | Referent | 2.2 (0.0013) | Referent | 8.0 (0.0026) | Referent | 1.4 (0.0012) | Referent |

| Kreteks | ||||||||||||

| Y | 89.7 (4.07) | † | 78.3 (6.59) | † | 82.4 (5.59) | † | 20.9 (5.98) | † | 33.4 (7.69) | † | 35.4 (7.18) | † |

| N | 31.7 (0.54) | Referent | 22.7 (0.55) | Referent | 13.6 (0.42) | Referent | 2.4 (0.14) | Referent | 8.1 (0.24) | Referent | 1.4 (0.12) | Referent |

| Bidis | ||||||||||||

| Y | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | 4.8 (1.7–13.7) | † | † | † | † |

| N | 31.7 (0.54) | Referent | 22.8 (0.55) | Referent | 13.7 (0.42) | Referent | 2.4 (0.14) | Referent | 8.1 (0.24) | Referent | 1.5 (0.12) | Referent |

| Dissolvable | ||||||||||||

| Y | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | NR | † | † | † | † |

| N | 31.8 (0.54) | Referent | 22.8 (0.55) | Referent | 13.8 (0.42) | Referent | 2.4 (0.13) | Referent | 8.1 (0.24) | Referent | 1.5 (0.13) | Referent |

Statistically significant associations at p < 0.05 indicated in bold text.

NR: estimates not reportable due to model convergence issues.

Includes ever use of cocaine or crack, stimulants (i.e. methamphetamine or speed), or heroin, inhalants, solvents, or hallucinogens.

Percentages (%) and standard errors (SE) are weighted to represent the US youth population.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from multivariable logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, lifetime mental health (internalizing and externalizing) problem symptoms, and sensation seeking.

Indicates gender interaction is significant at p < 0.05.

Estimates with a denominator < 50 or relative standard error > 30% were suppressed.

Although not systematic across tobacco products, gender moderated several associations between tobacco use and substance use. In all cases where this occurred, female tobacco users were more likely to use substances than male tobacco users. Specifically, female cigarette users were more likely than male cigarette users to use alcohol, marijuana, and Ritalin/Adderall. Additionally, for any tobacco product, any cigar, cigarillos, hookah, and smokeless tobacco (including snus pouches), female users were more likely to use alcohol than their male counterparts.

3.3. Tobacco use and substance use and mental health problems

Multivariable logistic regression models (Table 4) showed strong and consistent associations between ever tobacco use and high severity lifetime substance use problems. Tobacco users had an almost 20-fold (95% CI: 14.9–26.0) higher odds of substance use problems compared to non-users. Across tobacco products, the strongest associations were observed for cigarette (AOR = 14.7, 95% CI: 11.8–18.2), cigarillo (AOR = 8.1, 95% CI: 6.3–10.3), and filtered cigar (AOR = 8.1, 95% CI: 5.7–11.5) users, compared to non-users of those products, respectively.

Table 4.

High severity (%) of lifetime substance use, internalizing, and externalizing problems among ever tobacco users (Y) and non-users (N), PATH study, 2013–2014.

| High severity substance use problemsa | Mental health problems |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High severity internalizing problemsa |

High severity externalizing problemsa |

|||||

| % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | % (SE)b | AOR (95% CI)c | |

| Any tobacco | ||||||

| Y | 16.0 (0.82) | 19.7 (14.9–26.0) | 48.3 (0.95) | 1.6d (1.4–1.8) | 61.3 (1.06) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) |

| N | 0.6 (0.09) | Referent | 30.5 (0.66) | Referent | 43.8 (0.64) | Referent |

| Cigarettes | ||||||

| Y | 21.4 (1.18) | 14.7 (11.8–18.2) | 51.9 (1.28) | 1.7d (1.5–2.0) | 63.7 (1.27) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) |

| N | 1.2 (0.10) | Referent | 31.3 (0.58) | Referent | 44.8 (0.60) | Referent |

| E-cigarettes | ||||||

| Y | 20.4 (1.22) | 8.0 (6.5–9.9) | 50.5 (1.41) | 1.6d (1.3–1.8) | 64.8 (1.38) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) |

| N | 1.9 (0.14) | Referent | 32.1 (0.60) | Referent | 45.3 (0.59) | Referent |

| Any cigar | ||||||

| Y | 25.6 (1.57) | 9.5 (7.4–12.3) | 49.0 (1.39) | 1.4d (1.2–1.7) | 64.8 (1.64) | 1.4d (1.2–1.7) |

| N | 2.2 (0.17) | Referent | 33.0 (0.62) | Referent | 46.2 (0.58) | Referent |

| Traditional cigars | ||||||

| Y | 26.9 (2.89) | 5.8 (4.1–8.3) | 48.9 (3.03) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 67.6 (3.07) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) |

| N | 3.4 (0.20) | Referent | 33.9 (0.59) | Referent | 47.1 (0.57) | Referent |

| Cigarillos | ||||||

| Y | 25.7 (1.68) | 8.1 (6.3–10.3) | 48.4 (1.68) | 1.4d (1.2–1.7) | 64.3 (1.88) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) |

| N | 2.4 (0.17) | Referent | 33.2 (0.61) | Referent | 46.3 (0.58) | Referent |

| Filtered cigars | ||||||

| Y | 34.3 (3.18) | 8.1 (5.7–11.5) | 56.0 (3.23) | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | 70.8 (2.78) | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) |

| N | 3.2 (0.19) | Referent | 33.7 (0.58) | Referent | 47.0 (0.57) | Referent |

| Pipe | ||||||

| Y | 32.1 (3.53) | 7.2 (5.0–10.6) | 49.4 (3.79) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 61.2 (3.96) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) |

| N | 3.4 (0.19) | Referent | 33.8 (0.57) | Referent | 47.2 (0.58) | Referent |

| Hookah | ||||||

| Y | 22.7 (1.65) | 6.4 (5.0–8.1) | 47.5 (1.46) | 1.2d (1.0–1.4) | 59.1 (1.62) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) |

| N | 2.4 (0.16) | Referent | 33.0 (0.61) | Referent | 46.4 (0.61) | Referent |

| Smokeless (including snus pouches) | ||||||

| Y | 18.8 (1.53) | 4.7 (3.5–6.1) | 43.5 (1.96) | 1.2d (1.0–1.4) | 61.9 (1.75) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| N | 3.2 (0.20) | Referent | 33.6 (0.58) | Referent | 46.7 (0.60) | Referent |

| Smokeless (excluding snus pouches) | ||||||

| Y | 18.6 (1.57) | 4.3 (3.2–5.8) | 44.5 (2.03) | 1.2d (1.0–1.5) | 62.2 (1.88) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| N | 3.2 (0.21) | Referent | 33.6 (0.58) | Referent | 46.7 (0.60) | Referent |

| Snus pouches | ||||||

| Y | 23.8 (3.48) | 5.0 (3.3–7.7) | 42.4 (3.33) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 63.2 (3.35) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) |

| N | 3.6 (0.20) | Referent | 33.9 (0.58) | Referent | 47.1 (0.59) | Referent |

| Kreteks | ||||||

| Y | 37.7 (7.28) | † | 48.4 (8.46) | † | 70.7 (6.53) | † |

| N | 3.8 (0.21) | Referent | 34.1 (0.57) | Referent | 47.4 (0.59) | Referent |

| Bidis | ||||||

| Y | † | † | † | † | † | † |

| N | 3.8 (0.21) | Referent | 34.1 (0.57) | Referent | 47.4 (0.59) | Referent |

| Dissolvable | ||||||

| Y | † | NR | † | † | † | † |

| N | 3.9 (0.22) | Referent | 34.1 (0.57) | Referent | 47.4 (0.59) | Referent |

Statistically significant associations at p < 0.05 indicated in bold text.

NR: estimates not reportable due to model convergence issues.

Includes ever use of cocaine or crack, stimulants (i.e. methamphetamine or speed), or heroin, inhalants, solvents, or hallucinogens.

Percentages (%) and standard errors (SE) are weighted to represent the US youth population.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from multivariable logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, lifetime mental health (internalizing and externalizing) problem symptoms, and sensation seeking.

Indicates gender interaction is significant at p < 0.05.

Estimates with a denominator < 50 or relative standard error > 30% were suppressed.

The magnitude of associations for internalizing and externalizing problems varied by tobacco product, with ever cigarette, e-cigarette, traditional cigar, cigarillo, and filtered cigar use each significantly associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems, after adjusting for socio-demographics and sensation seeking. The strongest associations were observed for cigarette (AOR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.5–2.0) and filtered cigar (AOR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.3–2.3) users for internalizing problems, and filtered cigar users (AOR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.3–2.4) for externalizing problems. Results were virtually unchanged when analyses were repeated using the complete case method for handling missing data.

Similar to the tobacco and substance use associations, a significant gender-by-tobacco use interaction was seen across most tobacco product use groups for internalizing problem associations, which were stronger among female tobacco users than male tobacco users. In comparison, no gender differences were found for substance use problems or externalizing problems, with the exception of female cigar users being more likely to have externalizing problems than male cigar users.

3.4. Poly-tobacco use and substance use and mental health problems

Fig. 1 presents the proportions of alcohol or any drug use, high severity mental health problems, and high severity substance use problems among poly-tobacco users of any tobacco product versus exclusive users of any tobacco product. Poly-tobacco users were more likely to use alcohol or any drug than exclusive users (AOR = 3.4, 95% CI: 2.7–4.3). Further, poly-tobacco users had a nearly 5-fold higher odds (95% CI: 3.4–6.6) of having substance use problems in comparison to exclusive tobacco users. While the prevalence of internalizing and externalizing problems was higher among poly-tobacco users in comparison to exclusive users, the strength of the association was not as pronounced as for substance use and substance use problems (AOR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.0–1.5). No significant gender interactions were seen for these associations.

Fig. 1.

Ever substance use (%) and lifetime high severity mental health problems (%) among youth poly-tobacco ever users versus exclusive ever tobacco users, PATH study, 2013–2014.

4. Discussion

This is one of few studies to comprehensively examine co-occurrence of substance use and mental health problems across tobacco-product user groups and among poly-tobacco users in a nationally representative sample of U.S. youth. Findings indicate that youth tobacco users, in comparison to non-users, are more likely to use substances and have substance use problems. Moreover, these associations were robust across the 12 tobacco products assessed, as well as for poly-tobacco use. Tobacco users were also more likely to experience internalizing and externalizing problems. Notably, gender moderated the associations between tobacco use, substance use, and mental health problems. These findings have important implications for understanding substance use and mental health problems among youth tobacco users, as well as emphasizing the need to address these comorbidities in clinical and public health settings.

As documented previously (Ramo, Liu, & Prochaska, 2012; Richter et al., 2017), our findings show robust tobacco and substance use associations across tobacco products, particularly between filtered cigar and alcohol. The strong association between cigarillo and marijuana use was also striking and may point to the simultaneous use of tobacco and marijuana (e.g., blunts) as a risk pattern for continued use, addiction and associated medical consequences (Bélanger et al., 2013; Ramo et al., 2012). Considering the rapidly changing policies surrounding marijuana legalization and the emergence of non-cigarette tobacco products, the increased availability and use of these products by youth (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2017) represent a public health concern that warrants further attention.

Results were equally striking for associations between tobacco product use and substance use problems. The strongest association for substance use problems was found among cigarette users, which suggests that cigarette use may be a clinically useful indicator of problematic substance use (Office of the Surgeon General, 2016). This study also demonstrates that users of e-cigarettes, traditional cigars, cigarillos, filtered cigars, hookah, and smokeless tobacco are more likely to experience internalizing problems compared to their non-using counterparts, thereby extending prior research that focused primarily on cigarette smoking (Marmorstein et al., 2010; Marmorstein, White, Loeber, et al., 2010; Mistry, Babu, Mahapatra, & McCarthy, 2014; Zehe, Colder, Read, Wieczorek, & Lengua, 2013). While the association between cigarette use and externalizing problems has been established among youth (Armstrong & Costello, 2002; Colder et al., 2013; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on and Smoking Health, 2012), this study extends the literature for youth filtered cigar, e-cigarette, traditional cigar, and cigarillo users. Our finding of increased risk regardless of tobacco product points to nicotine as a common denominator of potential etiological significance in understanding the interplay between mental health and substance use problems. However, we cannot rule out that these associations may also be driven by a shared environmental, familial, or genetic diathesis representing a common underlying factor for tobacco use, substance use, and mental illness. Future analysis of the PATH Study’s longitudinal data can examine whether youth who use tobacco products are more or less likely to develop or exacerbate mental health problems.

Additionally, consistent with recent findings using 2014 data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) and the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study (Richter et al., 2017) and extending to mental health problems, poly-tobacco users were more likely to use alcohol and drugs and have substance use and mental health problems than exclusive tobacco users. Although these comorbidities are frequently documented, few prevention and intervention strategies address tobacco use within the same framework as substance use and mental health. Given the high prevalence of poly-tobacco use (Kasza et al., 2017; Richter et al., 2017; Villanti et al., 2016) and poly-substance use (Connor, Gullo, White, & Kelly, 2014) among youth, our findings support and reinforce the need for timely and comprehensive interventions and treatment that effectively address these co-occurring conditions (Camenga & Klein, 2016).

While exploratory, the gender differences in tobacco, substance use, and mental health comorbidities observed in this study warrant further attention. In all occurrences of gender-by-tobacco use interactions, female tobacco users were more likely to use substances than male tobacco users, particularly for cigarette users. Associations with alcohol use were also stronger for female non-cigarette tobacco product users compared to their male counterparts and across tobacco products, female users were more likely to have internalizing problems than males. These findings are consistent with the co-occurrence of these behaviors among adults (Conway et al., 2017), suggesting that female tobacco product users may be on an increased trajectory of risk for substance use and mental health problems beginning in adolescence, and effective interventions and treatment tailored to females are critical at a young age to prevent these disparities persisting into adulthood.

Although Wave 1 data from the PATH Study are nationally representative, harmonized with other national studies, and focus on multiple tobacco products, this study has limitations. The GAIN-SS measures severity of mental-health symptomology rather than diagnosis. However, the high sensitivity and specificity between GAIN-SS items and diagnoses supports the use of symptoms as good indicators of clinically significant mental-health problems (M. L. Dennis, et al., 2006). Additionally, some items from the GAIN-SS were omitted from the PATH Study’s Wave 1 instrument, thereby limiting the ability to assess their associations with tobacco use. Given the instrument design, we were not able to assess whether cigarillo users were also using cigarillos modified as a blunt at the same time or other instances, potentially explaining the large odds ratios observed for those associations. Furthermore, while testing interactions with demographic variables aside from gender were beyond the scope of this study, future studies may explore comorbidities across different subgroups defined by demographics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity), which can provide additional insight into the associations observed in this study. Finally, while the cross-sectional Wave 1 data preclude the establishment of temporality, future longitudinal data of the PATH Study will help clarify the temporal ordering between youth tobacco use, substance use, and substance use and mental health problems.

5. Conclusions

The present study documents high co-occurrence of alcohol and drug use, as well as substance use and mental health problems, across tobacco products in a nationally representative sample of U.S. youth. These findings also point to youth tobacco use, especially cigarette and poly-tobacco use, as a potential indicator of treatment need for substance use problems. Researchers and health-care providers should consider comprehensive assessments of tobacco use, substance use, and mental health problems to identify vulnerable youth for prevention and early intervention efforts, and effective treatments should take into account and address these comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Youth tobacco users were more likely to use alcohol or drugs compared to non-users.

Youth tobacco users were more likely to have substance use and mental health problems.

In particular, poly-tobacco use was strongly associated with substance use problems.

Female tobacco users were more likely to have substance use and internalizing problems.

Comprehensive interventions and treatments can effectively address youth comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

This manuscript is supported with federal funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, under a contract to Westat (Contract No. HHSN271201100027C).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures

W.M. Compton declares ownership of stock in General Electric Co, 3M Co, and Pfizer Inc, unrelated to the submitted work. No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views, official policy or position of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

References

- Armstrong TD, & Costello EJ (2002). Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1224–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg BJ, … Caraballo RS (2015). Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64, 381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger RE, Marclay F, Berchtold A, Saugy M, Cornuz J, & Suris J-C (2013). To what extent does adding tobacco to cannabis expose young users to nicotine? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15, 1832–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Epstein JN, Auinger P, Tamm L, & Froehlich TE (2015). Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder with early tobacco and alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 147, 183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenga DR, & Klein JD (2016). Tobacco use disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25, 445–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Grucza RA, & Bierut LJ (2014). Youth tobacco use type and associations with substance use disorders. Addiction, 109, 1371–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (2011–2012). National Health and nutrition examination survey questionnaire (NHANES) questionnaire Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Scalco M, Trucco EM, Read JP, Lengua LJ, Wieczorek WF, & Hawk LW Jr. (2013). Prospective associations of internalizing and externalizing problems and their co-occurrence with early adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 667–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JP, Gullo MJ, White A, & Kelly AB (2014). Polysubstance use: Diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27, 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Green VR, Kasza KA, Silveira ML, Borek N, Kimmel HL, … Compton WM (2017). Co-occurrence of tobacco product use, substance use, and mental health problems among adults: Findings from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177, 104–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demissie Z, Everett Jones S, Clayton HB, & King BA (2017). Adolescent risk behaviors and use of electronic vapor products and cigarettes. Pediatrics, 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Chan YF, & Funk RR (2006). Development and validation of the GAIN Short Screener (GSS) for internalizing, externalizing and substance use disorders and crime/violence problems among adolescents and adults. The American Journal on Addictions, 15(Suppl. 1), 80–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Feeney T, Stevens L, & Bedoya L (2006). Global Appraisal of Individual Needs–Short Screener (GAIN-SS): Administration and scoring manual for the GAIN-SS version 2.0.3 http://www.chestnut.org/LI/gain/GAIN_SS/index.htmlBloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar MS, Tucker JS, Ewing BA, Pedersen ER, Miles JN, Shih RA, & D’Amico EJ (2017). Frequency of E-cigarette use, health status, and risk and protective health behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 11, 55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, McGue M, & Iacono WG (2007). Prospective effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and sex on adolescent substance use and abuse. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner BR, Belur VK, & Dennis ML (2013). The GAIN short screener (GSS) as a predictor of future arrest or incarceration among youth presenting to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment. Substance Abuse, 7, 199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Grinberg A, Shapiro J, Keith D, McNeil MP, Taha F, … Hart CL (2014). Hookah use among college students: Prevalence, drug use, and mental health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 141, 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenman AP, Oosterlaan J, Rommelse N, Franke B, Roeyers H, Oades RD, … Faraone SV (2013). Substance use disorders in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A 4-year follow-up study. Addiction, 108, 1503–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, Maiese D, Hendershot T, Kwok RK, … Haines J (2011). The PhenX toolkit: Get the most from your measures. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174, 253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, & Donohew RL (2002). Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personal Individual Difference, 32, 401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Borek N, Lambert E, Carusi C, … Compton WM (2017). Design and methods of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Tobacco Control, 26(4), 371–378. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052934 (Epub 2016 Aug 8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2017). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Judkins DR (1990). Fay’s method for variance estimation. Journal of Official Statistics, 6, 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, & Chen K (1992). Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: Further evidence for the gateway theory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53, 447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Borek N, Taylor K, Goniewicz ML, … Hyland AJ (2017). Tobacco-product use by adults and youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376, 342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, … Merikangas KR (2012). Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Psychological Medicine, 42, 1997–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Proctor SE, Boudreault MA, & Turczyn KM (2002). Healthy People 2010 criteria for data suppression. Healthy People 2010 Stat Notes (pp. 1–12). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson AL, Mann MJ, & Smith ML (2017). Prevalence of substance use among middle school-aged e-cigarette users compared with cigarette smokers, nonusers, and dual users: Implications for primary prevention. Substance Abuse, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner WV, Janssen T, Kahler CW, Audrain-McGovern J, & Leventhal AM (2017). Bi-directional associations of electronic and combustible cigarette use onset patterns with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 96, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, & Kim AE (2015). Youth tobacco product use in the United States. Pediatrics, 135, 409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K, Liu R, & Glass K (2011). Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 328–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Sussman S, Kirkpatrick MG, Unger JB, Barrington-Trimis JL, & Audrain-McGovern J (2016). Psychiatric comorbidity in adolescent electronic and conventional cigarette use. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 73, 71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, White H, Chung T, Hipwell A, Stouthamer-Loeber M, & Loeber R (2010). Associations between first use of substances and change in internalizing symptoms among girls: Differences by symptom trajectory and substance use type. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 545–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, White HR, Loeber R, & Stouthamer-Loeber M (2010). Anxiety as a predictor of age at first use of substances and progression to substance use problems among boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 211–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Veliz P, & Boyd CJ (2017). E-cigarette use, cigarette smoking, dual use, and problem behaviors among U.S. adolescents: Results from a national survey. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(2), 155–162. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.004 (Epub 2017 Apr 5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy PJ (1969). Pseudoreplication: Further evaluation and applications of the balanced half-sample technique. Vital and Health Statistics, 2, 1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry R, Babu GR, Mahapatra T, & McCarthy WJ (2014). Cognitive mediators and disparities in the relation between teen depressiveness and smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 140, 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on and Smoking Health (2012). Reports of the surgeon general In preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Instiutes of Health (NIH); National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2004–2005). National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) MD: Rockville. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health Washington (DC): US Dept of Health and Human Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Zhou S, Sherman S, & Weitzman M (2014). Hookah use among U.S. high school seniors. Pediatrics, 134, 227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Liu H, & Prochaska JJ (2012). Tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of their co-use. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 105–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, Pugh BS, Smith PH, & Ball SA (2017). The co-occurrence of nicotine and other substance use and addiction among youth and adults in the United States: Implications for research, practice, and policy. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43, 132–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson ZD, & Riggs PD (2016). Cooccurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25, 713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp (2011). Stata statistical software: Release 12 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol M, & Dennick R (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. 10.5116/ijme.5114dfb.5118dfd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, & Audrain J (2002). Psychosocial correlates of alternate tobacco product use during early adolescence. Preventive Medicine, 35, 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Glasser AM, Johnson AL, Collins LK, Niaura RS, & Abrams DB (2016). Frequency of youth e-cigarette and tobacco use patterns in the U.S.: Measurement precision is critical to inform public health. Nicotine Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/ntw388 (pii: ntw388, Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westling E, Rusby JC, Crowley R, & Light JM (2017). Electronic cigarette use by youth: Prevalence, correlates, and use trajectories from middle to high school. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 60, 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehe JM, Colder CR, Read JP, Wieczorek WF, & Lengua LJ (2013). Social and generalized anxiety symptoms and alcohol and cigarette use in early adolescence: The moderating role of perceived peer norms. Addictive Behaviors, 38, 1931–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.