Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To examine racial and ethnic differences in knowledge about one’s dementia status

DESIGN:

Prospective cohort study

SETTING:

2000-2014 Health and Retirement Study

PARTICIPANTS:

Our sample included 8,686 person-wave observations representing 4,065 unique survey participants age ≥70 with dementia, as identified by a well-validated statistical prediction model based on individual demographic and clinical characteristics.

MEASUREMENTS:

Primary outcome measure was knowledge of one’s dementia status as reported in the survey. Patient characteristics included race/ethnicity, age, gender, survey year, cognition, function, comorbidity, and whether living in a nursing home.

RESULTS:

Among subjects identified as having dementia by the prediction model, 43.5%-50.2%, depending on the survey year, reported that they were informed of the dementia status by their doctor. This proportion was lower among Hispanics (25.9%-42.2%) and non-Hispanic blacks (31,4%-50.5%) than among non-Hispanic Whites (47.7%-52.9%). Our fully-adjusted regression model indicated lower dementia awareness among non-Hispanic blacks (OR=0.74 95% CI: 0.58-0.94) and Hispanics (OR=0.60; 95% CI: 0.43-0.85), compared to non-Hispanic whites. Having more IADL limitations (OR=1.65, 95% CI: 1.56-1.75) and living in a nursing home (OR=2.78, 95% CI: 2.32-3.32) were associated with increased odds of subjects reporting being told about dementia by a physician.

CONCLUSION:

Less than half of individuals with dementia reported being told by a physician about the condition. A higher proportion of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients with dementia may be unaware of their condition, despite higher dementia prevalence in these groups, compared to non-Hispanic whites. Dementia outreach programs should target diverse communities with disproportionately high disease prevalence and low awareness.

Keywords: dementia, health disparities, cognitive health

INTRODUCTION

The Healthy People 2020 public health goals for United States suggest that 65% of Americans with dementia may be unaware of their diagnosis.1 Although the reported proportion varies by study, researchers often find that more than half of those with dementia are unaware they have the condition.2–9 Compared to people with other common chronic conditions, such as cancer, people with dementia may be much less likely to be informed of their diagnosis.10 Knowing the diagnosis may have psychological benefits to patients with dementia because it may help them understand and cope with their memory problems and other symptoms.10,11 Some dementia patients and caregivers feel relieved once an explanation for symptoms is provided and a treatment plan is in place.12 When patients with dementia know about their condition, they have the opportunity to seek appropriate medical care and support services, maximize benefits of available treatments, and participate in decisions about their care.10,11,13 Even though dementia may influence one’s ability to remember a diagnosis, knowing one’s dementia status in the early stages of disease also allows patients to play an active role in making legal and financial plans.10,11 Moreover, many observers argue people have a right to know and understand their diagnosis, including dementia, because patient autonomy is an important principle of medical ethics.14 Respecting patient autonomy and shared decision-making has been shown to improve quality of care, treatment adherence and patient outcomes.10

According to Healthy People 2020, disease awareness among older adults with a dementia diagnosis has been similar across racial and ethnic groups (37% among blacks and Hispanics and 34% among whites in 2007-2009).1 In contrast, an analysis of the National Health and Aging Trends Study found that, once diagnosed with dementia, a higher proportion of blacks and Hispanics know they have the condition, compared to whites.2 While useful, these data may be liable to sample selection bias because they reflect disease awareness among people who have a dementia diagnosis documented in their Medicare claims files, omitting individuals without a claims-based diagnosis.

Dementia diagnosis codes may appear on a claim well after a patient has already progressed to more advanced disease stages, thus under-representing patients with milder dementia.15 Moreover, dementia may be undercoded in administrative claims files for a number of reasons, including limited access or poor quality of available care, little financial incentive for coding dementia, or patient and family resistance to a dementia diagnosis.9,16 Although undiagnosed dementia is a problem across all racial and ethnic groups, it may be more common among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics than among non-Hispanic whites.2,17–21 Other analyses using small or convenient samples generally underrepresent non-Hispanic black and Hispanic populations.3–8 Therefore, current data, based on selected samples, are insufficient to characterize potential differences by race and ethnicity in dementia awareness. Quantifying these differences is critical to understanding the unmet health care needs of underserved dementia patients and their caregivers.

This study examines trends over time in knowledge about one’s dementia status reported by patients themselves or their informants. We also assess racial and ethnic differences in dementia awareness. To address limitations stemming from use of claims-based dementia diagnoses, we use a modeling approach to identify individuals with dementia. Our analysis leverages nationally representative survey data with unique measures of cognitive function, making our findings generalizable to the US population.

METHODS

Data source

This study used eight waves of national survey data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) between 2000 and 2014, which was the latest wave available at the time of our analysis.22 The HRS is a longitudinal, national panel survey of U.S. adults over age 50 and their spouses or domestic partners. The study interviews roughly 20,000 respondents every two years (sample retention rate: 81%), eliciting information about demographics, income, health, cognition, health care utilization and costs, living arrangements, and other aspects of life. The HRS is well-suited for our investigation of racial and ethnic disparities in dementia because the survey oversamples non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics and allows the results to generalize to the U.S. population by applying sampling weights. Our sample included community-dwelling and nursing home residents, rather than recruitments from selected hospitals, for example, thus minimizing sample selection bias.

Identifying dementia cases

We identified HRS participants with dementia by using a statistical prediction model developed by Hurd and colleagues.23 The model estimates an HRS respondent’s probability of having dementia, based on the individual’s demographic and clinical characteristics. We used a modeling approach because HRS lacks a direct measure of dementia status. Hurd’s dementia prediction model has been well-validated and described in detail elsewhere.23,24 Briefly, the estimation involved two steps. Step 1 used a three-category order probit model to estimate the likelihood of “dementia,” “cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND),” or “normal” based on the Aging, Demographics and Memory Study (ADAMS) assessment. The initial ADAMS consisted of a stratified random subsample of 856 HRS respondents age >70 who underwent intensive clinical and neuropsychological assessments in their homes by a team of professionals.25–29 These assessments then classified each ADAMS respondent as having either dementia, a less significant level of cognitive impairment (i.e., CIND), or normal cognitive functioning, which served as the outcome variable of the order probit model. Predictors of the model include age, gender, education, imputed cognitive scores to account for missing values, changes in imputed cognitive scores between two previous HRS waves, functional limitations (including Activities of Daily Living [ADL] and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living [IADL]), and changes in functional limitations.23 Race or ethnicity was not used to predict dementia status.

The Hurd model predicted dementia status separately for self-respondents and proxy-respondents because cognitive assessments differ for these two groups (survey participants with severe cognitive and/or physical disabilities use a proxy respondent to give an interview). For self-respondents, the model used cognitive function measured by the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) scores, whereas for respondents represented by a proxy, cognitive function was measured by the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) scores.

Step 2 used these prediction results to calculate probabilities of dementia for all respondents age ≥70 who participated in the 2000-2014 waves of HRS. Per Hurd’s model, predicted dementia status referred to the time period one year after the HRS interview. For example, for a HRS 2000 respondent, the model would use the person’s responses to the 1998 and 2000 HRS interviews and estimate whether s/he had dementia in 2001. Following Hurd’s methodology, we categorized an HRS participant as having “dementia” if their predicted probability of dementia was higher than that of CIND or normal. The predicted dementia status served as the “gold standard” and determined subjects who had dementia. Our analyses assumed no backward transitions (that is, from a more severe to a less severe state), because fluctuation in the dementia prediction results may reflect short-term variation in cognitive states and measurement differences. Therefore, we excluded the few cases whose status changed from dementia to normal between two consecutive waves (n=20) and recoded a small proportion of subjects whose prediction results changed from dementia to CIND in subsequent surveys (n=453). Tests for within sample fit in ADAMS suggest that our re-created Hurd model demonstrates good predictive power to discriminate dementia cases (sensitivity: 78.0%; specificity: 86.9%); overall the model correctly classified 83.6% of cases. These performance metrics track closely with those reported by Hurd et al.23 Details of our re-creation of Hurd’s dementia prediction model are available in Supplemental Material S1 (dataset available from authors).

Measures

We measured knowledge of dementia based on an affirmative answer to the question “Has a doctor told you that you have Alzheimer’s disease or dementia?” in the HRS. We identified race and ethnicity (categorized as non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics) based on survey reports in the HRS. Non-Hispanic “other” respondents were excluded from the analyses due to small sample size. Other patient characteristics included age, gender, imputed cognitive scores (TICS scores for self-respondents and IQCODE scores for proxy-respondents), ADL and IADL function, number of comorbidities, and place of residence (community or nursing home).

Analysis

We analyzed predicted dementia prevalence rates in years 2001-2015 (i.e., the time period one year after the HRS interview) and survey-reported knowledge of dementia in 2002-2014 by race and ethnicity. Among individuals classified as having dementia by the prediction model, we examined racial and ethnic trends in awareness of one’s dementia status (i.e., whether they recalled receiving a memory problem/AD/dementia diagnosis from their doctor) in all waves in which they participated following the year of initial dementia prediction. For example, for a respondent classified as having dementia in 2001, who subsequently participated in the 2002, 2006, and 2008 HRS waves, we analyzed their survey-reported knowledge of dementia in those years.

We also conducted longitudinal analyses to examine whether knowledge about one’s dementia status differed by race and ethnicity, pooling data across eight HRS cohorts from 2000 to 2014. We used a logit-link binomial distribution generalized estimating equation (GEE) assuming an unstructured correlation. Our parsimonious model adjusted for age, gender and HRS survey year; the expanded model further adjusted for cognition, functional limitations, comorbidities and nursing home status, in addition to age, gender and year. All analyses adjusted for HRS sampling weights and were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 or STATA 15.1. This study was approved by the Tufts Medical Center/Tufts University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Predicted dementia prevalence rates by race and ethnicity

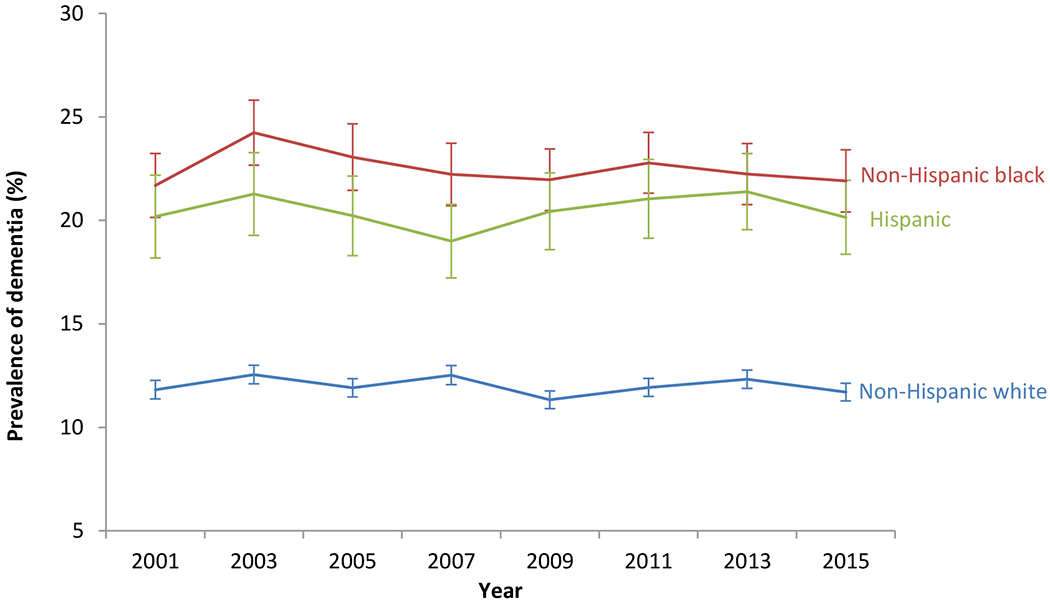

Our analytic sample included 8,686 person-wave observations representing 4,065 unique individuals age ≥70 with dementia (Supplementary Figure S1), as identified by the prediction model. Predicted dementia prevalence rates in 2001-2015 ranged from a high of 13.9% in 2003 and in 2013, to a low of 12.8% in 2009. The model predicted dementia prevalence was highest among non-Hispanic blacks (range during years 2001 through 2015: 21.6%-24.2%), followed by Hispanics (19.0%-21.4%) and non-Hispanic whites (11.4%-12.5%) (Figure 1). Estimated dementia prevalence appeared fairly consistent over time within each racial and ethnic group.

Figure 1: Trends in predicted prevalence rates of dementia by race and ethnicity (n=16,052).

Note: Sample used for this analysis are HRS respondents meeting criteria for inclusion in the dementia prediction model (Box 2 of the consort diagram in Supplementary Figure S1).

Sample characteristics

Study participants classified as having dementia in 2001 (the earliest cohort of our analysis) on average had two ADL limitations, two IADL limitations, and almost three other chronic conditions (Table 1). Among self-respondents, non-Hispanic whites had slightly higher average TICS scores (i.e., better cognitive function) than non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, whereas among those represented by proxy respondents, the three groups had similar average IQCODE scores. More non-Hispanic whites were living in a nursing home (37.1%) compared to non-Hispanic blacks (23.6%) and Hispanics (19.6%). These trends were similar among participants with dementia in 2015 (the latest cohort of our analysis).

Table 1:

Characteristics of Health and Retirement Study (HRS) participants classified as having dementia

| HRS participants classified as having dementia in 2001 | HRS participants classified as having dementia in 2015 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Non-Hispanic white (702) | Non-Hispanic black (199) | Hispanic (107) | Non-Hispanic white (780) | Non-Hispanic black (213) | Hispanic (136) | ||

| Age, %* | † | † | ||||||

| 70-74 | 6.3 | 12.2 | 18.9 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 6.8 | ||

| 75-79 | 15.7 | 12.8 | 17.3 | 9.7 | 14.9 | 13.9 | ||

| 80-84 | 24.6 | 29.9 | 26.0 | 21.0 | 27.5 | 26.0 | ||

| 85+ | 56.1 | 45.1 | 37.9 | 66.6 | 54.0 | 53.4 | ||

| Female, %* | 71.9 | 70.4 | 65.4 | 63.5 | 72.2 | 65.8 | ||

| Proxy Respondent (%)* | 61.0 | 53.7 | 59.7 | 40.1 | 38.9 | 38.1 | ||

| Mean TICS Score (SD)1 | 9.75 (0.22) | 7.44 (0.41) | 9.34 (0.44) | § | 9.86 (0.23) | 8.77 (0.41) | 8.24 (0.41) | § |

| Mean IQCODE Score (SD) 2 | 3.73 (0.05) | 3.77 (0.11) | 3.64 (0.14) | 3.51 (0.06) | 3.24 (0.14) | 3.47 (0.12) | ||

| Mean Number of ADL Limitations (SD)3 | 1.96 (0.08) | 1.89 (0.17) | 1.81 (0.22) | 2.00 (0.09) | 1.97 (0.16) | 2.41 (0.21) | ||

| Mean Number of IADL Limitations (SD)4* | 2.51 (0.07) | 2.31 (0.14) | 2.22 (0.19) | 2.21 (0.07) | 2.31 (0.14) | 2.64 (0.18) | § | |

| Mean Number of Comorbidities (SD) | 2.63 (0.06) | 2.70 (0.12) | 2.51 (0.16) | 3.31 (0.06) | 3.41 (0.14) | 3.30 (0.14) | ||

| Living in a Nursing Home, %* | 37.1 | 23.6 | 19.6 | † | 25.6 | 16.0 | 11.2 | † |

Weighted percentages/means using the HRS sample weights

Weighted chi-squared test p-value < 0.5

Weighted ANOVA test p-value < 0.5

Only for participants who did not have a proxy respondent (self-reported). Scale from 0-33; Higher scores indicate higher cognitive function

Only for participants who had a proxy respondent. Scale from 0-5; Lower scores indicate higher cognitive function

ADL: Activities of Daily Living. Numbers are the reported number of activities (6 total) participants have difficulty performing; Lower scores indicate higher functional ability

IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Numbers are the reported number of activities (5 total) participants have difficulty performing; Lower scores indicate higher functional ability

Proportion of subjects reporting being informed of dementia by their doctor in the overall HRS sample

Of HRS participants age ≥70 in 2014 (n=7,829), 7.7% reported that they were informed of the dementia status by their doctor (Table 2). More non-Hispanic blacks reported knowing their dementia status (11.6%), compared to Hispanics (9.5%) and non-Hispanic whites (7.1%). The gaps between racial and ethnic groups in predicted dementia prevalence were wider than the gaps in survey-reported knowledge of dementia.

Table 2:

Percentage of Health and Retirement Study (HRS) participants with dementia, by race and ethnicity

| Model-predicted dementia (2013 HRS, n=8,144)1 | Survey-reported dementia (2014 HRS, n=7,829)2 | Kappa statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage with dementia, overall | 13.9% | 7.7% | 0.490 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 12.5% | 7.1% | 0.497 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 23.1% | 11.6% | 0.506 |

| Hispanic | 21.7% | 9.5% | 0.395 |

Reflects predicted dementia status of respondents who participated in HRS survey years 2010 and 2012, and met the inclusion criteria for the dementia prediction model (this group belongs to Box 2 of the consort diagram in Supplemental Figure S1).

Reflects respondents who participated in the 2014 HRS survey and reported being told by a doctor of having dementia.

Awareness of one’s dementia status among HRS participants with dementia

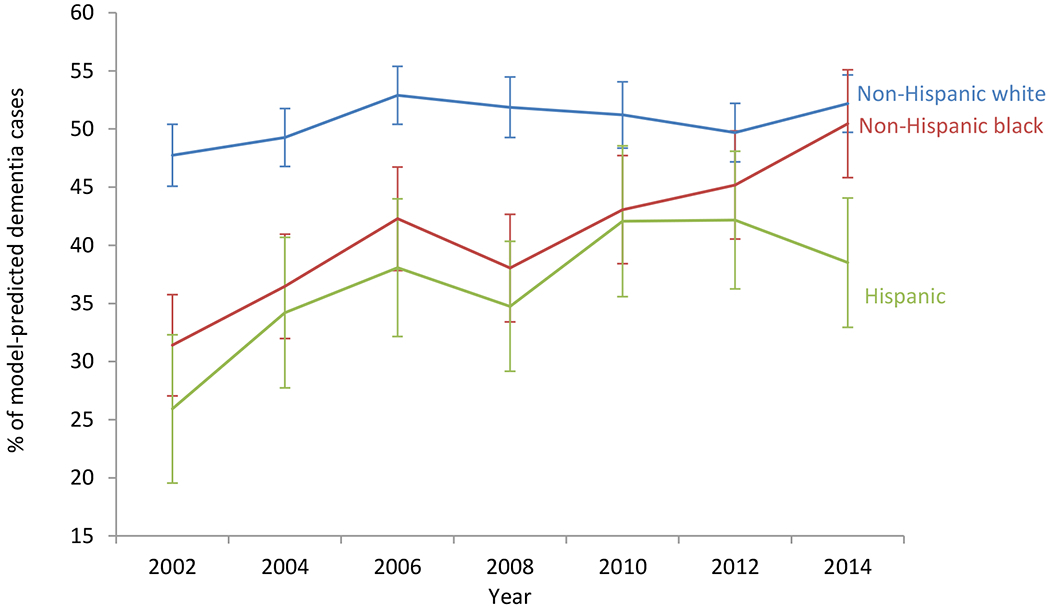

Among subjects identified as having dementia by the prediction model (n=4,065), 43.5%-50.2% (depending on the HRS survey year) reported that they were informed of the dementia status by their doctor (Figure 2). Knowledge of one’s dementia status was lower among Hispanics (25.9%-42.2%) and non-Hispanic blacks (31.4%-50.5%) than among non-Hispanic Whites (47.7%-52.9%). Dementia awareness generally improved over time across all racial and ethnic groups.

Figure 2: Trends in knowledge about dementia status by race and ethnicity among model-predicted dementia cases (n=4,065).

Note: Sample used for this analysis are HRS respondents predicted to have dementia (Box 4 of the consort diagram in Supplementary Figure S1).

In adjusted analyses (Table 3), our parsimonious model showed that non-Hispanic black and Hispanic respondents with dementia (as classified by model) were less likely than their non-Hispanic white peers to report being told by a physician that they had dementia (OR=0.66; 95% CI: 0.53-0.83 and OR=0.61; 95% CI: 0.46-0.83, respectively). Similarly, the expanded model adjusting for additional patient characteristics also indicated lower dementia awareness among non-Hispanic blacks (OR=0.74 95% CI: 0.58-0.94) and Hispanics (OR=0.60; 95% CI: 0.43-0.85), compared to non-Hispanic whites. Having more IADL limitations (OR=1.65, 95% CI: 1.56-1.75) and living in a nursing home (OR=2.78, 95% CI: 2.32-3.32) were associated with increased odds of reporting being told about dementia by a physician. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes baseline characteristics of these respondents.

Table 3:

Odds ratios of reporting being told of dementia by a doctor among model-predicted dementia cases1

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.66 (0.53, 0.83) | 0.74 (0.58, 0.93) |

| Hispanic | 0.61 (0.46, 0.80) | 0.60 (0.43, 0.85) |

| Age | ||

| 70-74 | 1.48 (1.02, 2.14) | 1.46 (0.89, 2.38) |

| 75-79 | 1.53 (1.22, 1.92) | 1.55 (1.17, 2.06) |

| 80-84 | 1.15 (0.98, 1.36) | 1.33 (1.10, 1.60) |

| 85+ | Reference | Reference |

| Female vs. Male | 1.29 (1.06, 1.57) | 1.12 (0.91, 1.40) |

| HRS Survey Year | 1.09 (1.07, 1.11) | 1.05 (1.03, 1.07) |

| Cognitive Impairment2 | -- | 1.31 (0.98, 1.76) |

| Number of ADL Limitations3 | -- | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) |

| Number of IADL Limitations4 | -- | 1.65 (1.56, 1.75) |

| Number of Comorbidities | -- | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) |

| Living in a Nursing Home | -- | 2.77 (2.32, 3.32) |

Sample used for the analyses corresponds with Box 5 of the consort diagram in Supplemental Figure S1 (n=2,367 respondents). The analyses used a weighted logit-link binomial distribution generalized estimating equations assuming an unstructured correlation structure. We used average sample weighs of each HRS respondent, following NHANES guidelines on combing survey cycles. The results had little to no change when using participants’ combined, first, last, or first year predicted to have dementia HRS wave-specific sample weights.

Cognitive function combined normalized TICS scores and IQCODES scores based on whether participants had a proxy respondent. 0: No impairment; 1: High impairment

Activities of Daily Living. Numbers are the reported number of activities (total of six) participants has difficulty performing; Lower scores indicate higher functional ability

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Numbers are the reported number of activities (total of five) participants has difficulty performing; Lower scores indicate higher functional ability

DISCUSSION

Leveraging nationally representative survey data with unique cognitive measures, our study found that less than half of those with dementia (as identified by a prediction model) reported being told by a physician about the condition. Awareness of one’s dementia status improved in more recent years in all racial and ethnic groups. Our modeling results showed that dementia prevalence rates may be nearly twice as high among non-Hispanic blacks and 1.7 times as high among Hispanics, compared to non-Hispanic whites. A higher proportion of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients with dementia may be unaware of their condition, despite higher dementia prevalence in these groups, compared to non-Hispanic whites.

Why are there ethnoracial differences in dementia awareness? We consider two possibilities. First, levels of undiagnosed dementia may vary across populations (i.e., diagnosis disparity). Although undiagnosed dementia in its early stages is a general phenomenon, it may be more common among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics than among non-Hispanic whites.2,17–21 Racial and ethnic minority groups also may experience additional barriers such as less knowledge about dementia and inferior access to health care services.30 Ethnoracial differences in dementia prevalence found in our model prediction were greater than claims-based estimates reported in the literature,31 also suggesting more frequent undiagnosed dementia among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics.

Second, some groups may be less likely to be informed of their illness by their health care providers (i.e., disclosure disparity). Although not specifically about dementia, some evidence indicates that provider bias may affect their disease disclosure or treatment decisions in certain ethnoracial groups.32–34 Suboptimal communication of diagnostic findings to dementia patients and their caregivers is problematic because it prevents or delays access to timely medical and supportive care. Besides diagnosis and disclosure disparities, it is possible that some people may be reluctant to report they have dementia and some may perceive memory loss as part of normal aging, thus under-recognizing the condition. However, because differences between each of these two ethnoracial groups and non-Hispanic whites observed in our study show consistent patterns, it is unlikely such differences are due to personal or cultural factors.

Our study results, whether they reflect diagnosis disparity, disclosure disparity or both, have important implications for community education and provider training. We found that reporting about being informed of dementia has increased in recent years, suggesting that disease awareness may have generally improved in the community. Still, roughly half of dementia patients or their caregivers in our study may be unaware of the condition. Prior research comparing claims-based dementia diagnosis and survey-reported knowledge of dementia also found about half of Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with dementia may not know they had the condition.9 These findings highlight an important unmet need in dementia care. As proposed in Healthy People 2020, increasing awareness of dementia diagnosis among individuals with the condition and their caregivers is an important policy goal.1 Our findings call for system changes to promote early detection and assessment of dementia and better communication of the diagnosis. More importantly, such efforts should target diverse communities, especially those with disproportionately high dementia prevalence and low awareness. These interventions should develop culturally-appropriate education, based on community and other stakeholder input,35 to increase awareness and knowledge about cognitive health. Lacking knowledge about early signs of dementia among some ethnoracial minority groups, rather than culturally-influenced beliefs, has been identified as a key deterrent to memory assessment in older adults.36

Furthermore, provider training in making and delivering a dementia diagnosis also needs improvement. Training programs should promote culturally sensitive and competent dementia care, such as using a tailored approach to communicate dementia diagnostic information.17,36–38 For example, some individuals may prefer a direct disclosure, whereas others may benefit from having the physician ease them into the dementia diagnosis.37 Despite concerns about causing an emotional reaction, studies of the general population, people with dementia and their caregivers all suggest the desire of knowing.12,17,36 Physicians should work with the person with dementia and their care partner(s) to understand preferences for diagnostic disclosure, as recommended by the Alzheimer’s Association Clinical Practice Guidelines.39

Because HRS lacks a direct measure of dementia status and because there is no uniformly accepted definition of dementia in observational studies, we rely on a statistical model to identify subjects with dementia. Our approach has the advantage of including patients who otherwise may have been missed by using claims-based dementia diagnoses. Studies linking Medicare claims records and clinical dementia assessments have reported that Medicare claims correctly identify roughly 85% of patients with dementia, but the sensitivity by race and ethnicity is less clear due to lacking sufficient sample sizes.15,40 The Hurd model has been well-validated and may out-perform other dementia prediction algorithms, such as those cutoff-based approaches that classify dementia status based solely on summary cognitive and/or functional scores.41 Our re-created Hurd model demonstrates good predictive performance in ADAMS not only among non-Hispanic whites (sensitivity: 75.1%; specificity: 91.0%), but also among non-Hispanic blacks (sensitivity: 84.8%; specificity: 76.7%) and Hispanics (sensitivity: 91.3%; specificity: 75.4%). Newly available data from the HRS-linked Healthy Cognitive Aging Project with dementia ascertainment information could help assess model prediction results across ethnoracial subgroups in a large, nationally representative sample.

Several study limitations warrant consideration. First, some individuals, especially self-respondents with dementia, may not recall whether being told that they have the condition. However, consistent with prior research,10 our data showed that individuals who had more severe cognitive and functional limitations were more likely than those with milder impairment to report having dementia. Moreover, self- or proxy-report of dementia in survey data is an important source for case ascertainment and may identify more dementia cases than diagnosis codes in medical claims.9 Second, self-respondents and subjects using proxies may have different patterns for reporting knowledge of dementia status. In our data, sample members using proxy informants had poorer cognitive function, more functional impairments and more comorbidities than self-respondents. These trends are consistent with the fact that the HRS includes interviews of proxy informants when sample members are unable to complete an interview due to physical or cognitive limitations. In our adjusted analyses, including proxy status in the expanded model did not have an impact on the relationship between dementia awareness and race/ethnicity or other patient characteristics. Although proxy interviews are not a perfect substitute, prior research has shown that excluding proxy responses may introduce more biases than including them.42 In fact, by integrating the use of proxies into the study design, HRS data can minimize sample composition bias on cognitive function due to attrition and non-response.42 Third, our analyses were restricted to individuals age ≥70. We found that younger individuals may be more likely to report being told about having dementia, although the differences by race and ethnicity might not fully generalize to a younger population.

Using national survey data with unique cognition measures, we found that less than half of individuals with dementia may be aware of their condition, and this problem may be more pronounced among some ethnoracial minority groups. Our analyses highlight important unmet needs in diagnosing dementia and communicating the diagnosis effectively. These findings call for improvement in dementia diagnostic services to assist underserved populations and their families. Dementia outreach programs should target diverse communities with disproportionately high disease prevalence and low awareness. Moreover, provider training should include communication skills tailored to patient and caregiver needs and preferences. Further qualitative and quantitative research is critical to understanding health care barriers to dementia assessment among different racial and ethnic groups.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding of our research was provided by the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institutes of Health (R01AG060165). We are grateful to Dr. Paco Martorell at the UC Davis School of Education for assistance with programming their dementia prediction model.

Conflict of Interest: Pei-Jung Lin reports consulting from Avanir, Otsuka, and Takeda outside the submitted work. Joshua Cohen reports consulting from Axovant, Novartis, Partnership for Health Analytic Research, Pharmerit, Precision Health Economics, Sage Therapeutics, and Sarepta Therapeutics outside the submitted work. Peter Neumann reports advisory boards or consulting from Abbvie, Amgen, Avexis, Bayer, Congressional Budget Office, Vertex, Veritech, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Precision Health Economics, and funding from The CEA Registry Sponsors by various pharmaceutical and medical device companies. The other authors do not have any disclosures.

Sponsor’s Role: Publication is not contingent on Alzheimer’s Association’s or the National Institute of Health’s approval.

Funding source: Alzheimer’s Association and National Institutes of Health (R01AG060165)

References

- 1.US Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy people 2020. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amjad H, Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Lyketsos CG, Wolff JL, Samus QM. Underdiagnosis of dementia: An observational study of patterns in diagnosis and awareness in us older adults. Journal of general internal medicine 2018;33:1131–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett AM, Orange W, Keller M, Damgaard P, Swerdlow RH. Short-term effect of dementia disclosure: How patients and families describe the diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1968–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell KH, Stocking CB, Hougham GW, Whitehouse PJ, Danner DD, Sachs GA. Dementia, diagnostic disclosure, and self-reported health status. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindau M, Bjork R. Anosognosia and anosodiaphoria in mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders extra 2014;4:465–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savva GM, Arthur A. Who has undiagnosed dementia? A cross-sectional analysis of participants of the aging, demographics and memory study. Age and ageing 2015;44:642–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stites SD, Karlawish J, Harkins K, Rubright JD, Wolk D. Awareness of mild cognitive impairment and mild alzheimer’s disease dementia diagnoses associated with lower self-ratings of quality of life in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2017;72:974–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaleta AK, Carpenter BD, Porensky EK, Xiong C, Morris JC. Agreement on diagnosis among patients, companions, and professionals after a dementia evaluation. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012;26:232–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin PJ, Kaufer DI, Maciejewski ML, Ganguly R, Paul JE, Biddle AK. An examination of alzheimer’s disease case definitions using medicare claims and survey data. Alzheimers Dement 2010;6:334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:332–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bamford C, Lamont S, Eccles M, Robinson L, May C, Bond J. Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: A systematic review. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 2004;19:151–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter BD, Xiong C, Porensky EK, et al. Reaction to a dementia diagnosis in individuals with alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter B, Dave J. Disclosing a dementia diagnosis: A review of opinion and practice, and a proposed research agenda. Gerontologist 2004;44:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Association AM. Code of medical ethics. CHAPTER 2: OPINIONS ON CONSENT, COMMUNICATION & DECISION MAKING, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee E, Gatz M, Tseng C, et al. Evaluation of medicare claims data as a tool to identify dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2019;67:769–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fillit H, Geldmacher DS, Welter RT, Maslow K, Fraser M. Optimizing coding and reimbursement to improve management of alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1871–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lines LM, Sherif NA, Wiener JM. Racial and ethnic disparities among individuals with alzheimer’s disease in the united states: A literature review. RTI Press, Research Triangle Park, NC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manly JJ, Mayeux R . Ethnic differences in dementia and alzheimer’s disease In: Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen, eds. Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. Washington (DC), 2004, pp. 95–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitten LJ, Ortiz F, Ponton M. Frequency of alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in a community outreach sample of hispanics. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1301–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark PC, Kutner NG, Goldstein FC, et al. Impediments to timely diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease in african americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:2012–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Tysinger B, Crimmins E, Zissimopoulos JM. Analysis of dementia in the us population using medicare claims: Insights from linked survey and administrative claims data. Alzheimer’s & dementia (New York, N Y) 2019;5:197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR. Cohort profile: The health and retirement study (hrs). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the united states. N Engl J Med 2013;369:489–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Langa K. Future monetary costs of dementia in the united states under alternative dementia prevalence scenarios. J Popul Ageing 2015;8:101–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the united states: The aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology 2007;29:125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the united states. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, et al. A comparison of the prevalence of dementia in the united states in 2000 and 2012. JAMA internal medicine 2017;177:51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langa KM, Plassman BL, Wallace RB, et al. The aging, demographics, and memory study: Study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology 2005;25:181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: The health and retirement study and the aging, demographics, and memory study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2011;66 Suppl 1:i162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sayegh P, Knight BG. Cross-cultural differences in dementia: The sociocultural health belief model. International psychogeriatrics 2013;25:517–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the united states (2015-2060) in adults aged >/=65 years. Alzheimers Dement 2019;15:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: Do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? American journal of public health 2003;93:248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. Journal of general internal medicine 2007;22:1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarthy AM, Bristol M, Domchek SM, et al. Health care segregation, physician recommendation, and racial disparities in brca1/2 testing among women with breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2016;34:2610–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Services USDoHaH. National stakeholder strategy for achieving health equity.

- 36.Mahoney DF, Cloutterbuck J, Neary S, Zhan L. African american, Chinese, and latino family caregivers’ impressions of the onset and diagnosis of dementia: Cross-cultural similarities and differences. Gerontologist 2005;45:783–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Connell CM, Boise L, Stuckey JC, Holmes SB, Hudson ML. Attitudes toward the diagnosis and disclosure of dementia among family caregivers and primary care physicians. Gerontologist 2004;44:500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, et al. Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement 2019;15:292–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atri A, Knopman DS, Norman M, et al. Details of the new alzheimer’s association best clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation of neurodegenerative cognitive behavioral syndromes, alzheimer’s disease and dementias in the united states. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2018;14:P1559. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor DH Jr., Ostbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL. The accuracy of medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: The case of dementia revisited. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2009;17:807–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rand hrs 2000 fat file (v1c). In: RAND Center for the Study of Aging UoM, ed., V1C edn, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weir D, Faul J, Langa K. Proxy interviews and bias in the distribution of cognitive abilities due to non-response in longitudinal studies: A comparison of hrs and elsa. Longitudinal and life course studies 2011;2:170–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.