Abstract

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is a standard treatment option for colorectal cancer (CRC) but its rapid metabolism and systemic instability (short half-life) has hindered its therapeutic efficacy. The objective of this study was to develop a novel drug delivery system, solid lipid nanoparticle (SLN), capable of delivering high payload of 5-FU to treat CRC. The rational was to improve 5FU-nanocarrier compatibility and therapeutic efficacy. The SLN-loaded 5-FU was developed by utilizing a Strategic and unique Method to Advance and Refine the Treatment (SMART) of CRC through hot and cold homogenization approach. The SLN was made of unique PEGylated lipids and combination of the surfactants. Cytotoxicity studies, clonogenic assay, flow cytometry and confocal imaging were conducted to evaluate the effectiveness and cellular uptake of 5FU-SLN4 in HCT-116 cancer cells. Pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters and receptor expressions were determined while tumor efficacy studies were conducted on mouse bearing subcutaneous HCT-116 cancer. Among the all the formulations, 5FU-SLN4 was the most effective with particle size of was 263 ± 3 nm, zeta potential was 0.1 ± 0.02 and entrapment efficiency of 81 ± 10%. The IC50 value of 5FU-SLN4 (7.4 ± 0.02 µM) was 2.3 fold low compared with 5-FU (17.7 ± 0.03 µM). For tumor efficacy studies, 5FU-SLN4 significantly inhibited tumor growth in comparison to 5-FU while area-under plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) of 5FU-SLN4 was 3.6 fold high compared with 5-FU. HER2 receptors expression were markedly reduced in 5-FU-SLN4 treated mice compared with 5FU and liver and kidney tissues showed no toxicity at dose of 20 mg/kg. 5FU-SLN4 was highly cytotoxic against HCT-116 cells and significantly inhibited subcutaneous tumor growth in mice compared with 5-FU. This emphasizes the significance of developing a smart nano-delivery system to optimize the delivery efficiency of anticancer drugs to tumors.

Subject terms: Cancer, Nanoscience and technology

Introduction

CRC is the third most diagnosed cancer in individuals in US, and a third leading cause of cancer related deaths. CRC is the second highest cause of cancer deaths when men and women are combined1. According to many sources, CRC is expected to cause more than 50,000 deaths during 20191,2.

The present treatment of CRC largely depends on radiotherapy, surgery, targeted therapy and chemotherapy; however, surgery is the preferred option if CRC is at stages one through to four with or without chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy3. Based on the stage of CRC, two or more treatment options are combined to achieve the desired therapeutic effect. Further, reports show that 5-year survival rate of individuals with metastatic cancer is less than those without metastatic cancer1. The present treatment strategies, examples, targeted therapy and chemotherapy largely affect CRC cells mainly through cell senescence and apoptosis.

The existing therapeutic agents for the treatment of CRC are diverse. They include cytotoxic agents such as 5-FU, oxaliplatin, capecitabine and irinotecan, and targeted therapies such as bevacizumab and anti-epidermal growth factor receptor anti-bodies (examples are cetuximab and panitumumab).

While 5-FU is often used alone or in combination with other anticancer agents such as irinotecan and folinic acid (FOLFIRI) or folinic acid and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX)4, it’s antimetabolite mimics uracil and thymine which eventually incorporates into DNA and RNA synthesis leading to cytotoxicity and cell death5. 5-FU is a fluorinated pyrimidine that inhibits DNA and RNA activity through inhibition of the rate-limiting enzyme (thymidylate synthetase) in pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis6.

Although 5-FU shows inhibitory activity on DNA synthesis, its therapeutic efficacy is limited due to its hydrophilic nature and rapid metabolism by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase. Therefore, continuous administration of high doses of 5-FU must be applied to attain the required therapeutic concentration which causes severe toxic effects on the gastrointestinal tract, hematological, neural, cardiac and dermatological reactions7. Hence, there is a need to develop a smart delivery system capable of protecting and delivering a high payload of 5-FU to the desired site with improved therapeutic efficacy.

Nanotechnology has become one of the fastest growing areas with potential applications in drug therapy such as liposomes, micelles, polymeric nanoparticles, and dendrimers have been widely used to convey and overcome drugs with aqueous solubility or systemic stability related issues. Among all the nanodelivery systems, lipid-based nanocarriers are commonly considered the least toxic for in vivo applications and a remarkable progress has been achieved in DNA/RNA in delivery8.

While delivery approaches such as liposomal and polymeric nanoparticles have had setbacks, investigations of solid lipid nanoparticle (SLN) as substitute drug carrier system has proven to be a novel, due to its various advantages such as the ability to incorporate of both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs, ease of scale-up and enhanced physical stability9,10. By virtue of nanoparticle’s size effect and improved physicochemical properties, the SLN can extravasate into the tumor through the tumor’s leaky vasculature and increase localized tumor drug exposure11.

The current study aimed to develop a smart delivery system capable of delivery a high payload of 5-FU, a hydrophilic drug, into optimized SLNs (5FU-SLNs) with special emphasis on protection and prolonging systemic circulation of 5-FU and, to improve its therapeutic outcome. In this context, the use of smart PEGylated 5FU-SLN4 was developed and optimized to obtain a high entrapment efficiency that was highly cytotoxic against HCT-116 cells, improved 5-FU pharmacokinetic parameters and significantly inhibited subcutaneous tumor growth in mice compared with 5-FU. These improved efficacy of 5-FU emphasized the significance of developing a smart nano-delivery system to optimize the delivery efficiency of anticancer drugs to tumors.

Results

CRC mortality has slowly decline largely due to cancer prevention and early detection, however; cancer prevention and early detection may not be the only key factors for the management or treatment of patients with CRC. In 2019, 145,600 estimated new cases of CRC will occur and an estimated 51,020 deaths is expected to occur for the year12. While prevention through screening is the best approach to combat the development of CRC, many patients present with advanced disease that will require surgery and systemic therapy to improve survival. With respect to systemic therapy, the median survival of patients with metastatic CRC has improved over the past three decades due to the introduction of 5-FU.

5-FU is commonly used alone or in combination with other anticancer drugs as first—line treatment for patients who have developed advanced CRC. The anticancer agent exerts its effect by interrupting RNA processing and blocking normal DNA synthesis. However, the response rate of 5-FU is less than 15% and due to dihydropyrimindine dehydrogenase (DPD) 80% of 5-FU is rapidly broken down limiting the therapeutic efficacy of the anti-cancer agent13–15.

Pharmaceutical nano drug systems have become idea for the transport of anti-cancer drugs and the reduction of unwanted distribution and side effects to healthy cells. These nanoparticles provide protection for anti-cancer drugs from first—pass metabolism and enzymatic degradation. In addition, nano drug systems generally provide enhancement properties of the drug, for example, prolong systemic circulation, increase drug entrapment and loading capacity. For many of those reasons, we decided to develop a novel SLN delivery system capable of high payload of 5-FU and improve 5-FU therapeutic efficacy on HCT-116 colon cancer.

Characterization of PEGylated 5FU-SLNs

PEGylated SLNs are carrier systems that have been developed to encapsulate, protect and deliver active drug components. Six different batches of loaded SLNs were prepared by cold homogenization method. Cold homogenization was used to overcome temperature induced drug degradation, drug distribution into aqueous phase and crystallization modification as the method is also the preferred technique for hydrophilic drugs16,17. The active drug molecules were dispersed into the lipid melt fabricating a drug enriched core, a type of SLN as illustrated in Fig. 1. All batches were used in initial in-vitro studies indicated in Fig. 2A. Table 1 presents the drug, lipid, and surfactant composition for each batch of 5FU-SLN. With the chosen lipid compositions, glycerol monostearate, Compritol 888 ATO and Precirol ATO 5 (2–3%) the particle size and dispersity stayed in range, 77–288 nm. 5FU-SLN1 had a glycerol monostearate content of 2% and an observed higher particle size with decreased dispersity compared to other formulations with 3% lipid content. The choice of surfactants and its concentration has a great impact on SLN size. Lipid and surfactant compositions were kept below 5% to prevent particle growth and maintain small particle size. Again, higher concentrations of surfactants may lead to toxicity as reported in literature that ionic emulsifiers are more likely to produce smaller size in comparison to non-ionic emulsifiers even at the equal concentrations18. With the knowledge given formulations 5FU-SLN5 and 5FU-SLN6 both contain a non-ionic emulsifier as well as Lecithin, a highly recommended co-emulsifier to help decrease the particle size. The results showed smaller particle size for those formulations in comparison to those that were prepared with frequently used Tween 80 only. The surfactant concentrations did not drastically change/effect zeta potential. The results suggest that the surfactant concentrations are sufficient for the development of SLNs as the particle size range is expected. It could be seen from Table 1 the mean particle size, zeta potential and polydispersity index (PI) for each formulation (Supplementary Figures S7 and S8). The PI is used to measure the degree of non-uniformity of a size distribution of nanoparticles. With the use of the cold homogenization technique, wide dispersion typically occurs as indicated by the PI values shown in Table 1. Although all formulations had reasonable particle sizes, ranging from 77 to 288 nm, 5FU-SLN4 with particle size of 263 ± 3 nm with transmission electronic microscopy image (TEM) as shown in Supplementary Figure S1 was chosen for this study. The reason for selecting 5FU-SLN4 was due to the desired cytotoxicity activity displayed by 5FU-SLN4 in Fig. 2A–C, Supplementary figure S6 as well the high entrapment efficiency (EE) of 81 ± 10% (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

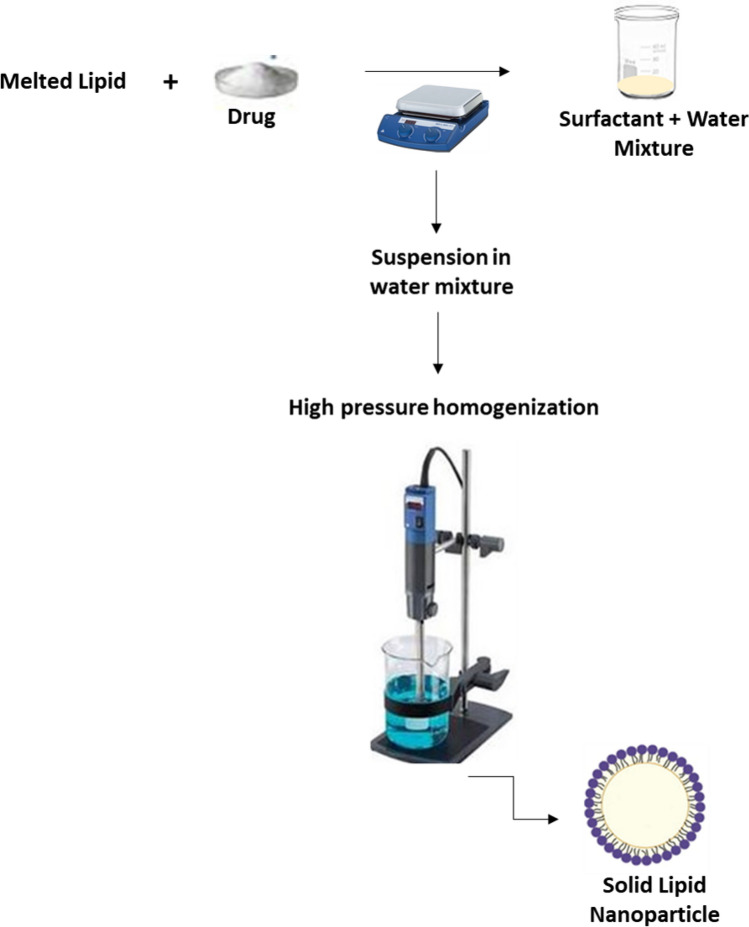

Figure 1.

Nanoparticle schematic: a visual illustration demonstrating the sequence of 5-FU loaded solid lipid nanoparticles.

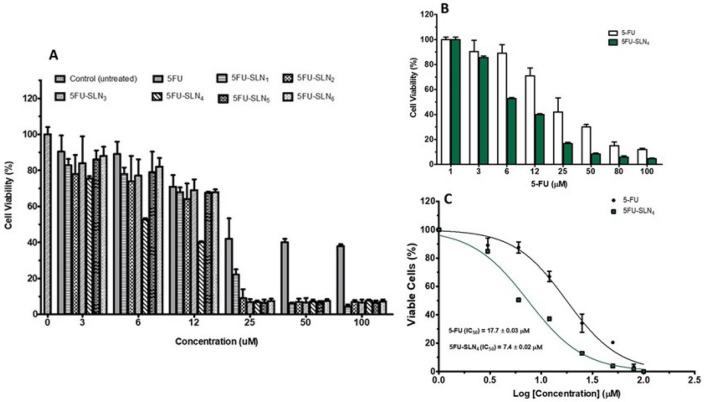

Figure 2.

Cell viability: Effects of 5FU-SLN formulations on HCT-116 cell growth. (A) Percent viability of HCT-116 cells after treatment with 5-FU and different 5FU-SLN formulations. (B) Viability of HCT-116 cells after treatment with 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4, treatment shows dose-dependent growth inhibition of cell lines, and (C) IC50 values generated based on non-linear curve fitting for dose–response curves for 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 treated HCT-116 cells.

Table 1.

Composition and characterization of 5FU-SLN.

| Formulation | 5-FU (%w/v) | Lipid composition | Lipid ratio (%w/v) | Surfactant composition | Surfactant ratio (%w/v) | Mean particle size (nm) | Mean zeta potential (mV) | Polydispersity index (P.I) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5FU-SLN1 | 0.15 | GM | 2 | TWN 80 | 1.5 | 288 ± 5 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 0.3 |

| 5FU-SLN2 | 0.15 | Compritol | 3 | TWN 80 | 4 | 170 ± 3 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | 1.4 |

| 5FU-SLN3 | 0.15 | Precirol | 3 | TWN 80 | 4 | 228 ± 6 | 0.6 ± 0.02 | 1.2 |

| 5FU-SLN4 | 0.15 | Precirol | 3 | TWN80/Lecithin | 4:2 | 263 ± 3 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 0.9 |

| 5FU-SLN5 | 0.15 | Precirol | 3 | Poly/Lecithin | 4:2 | 130 ± 5 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 0.7 |

| 5FU-SLN6 | 0.15 | Compritol | 3 | Poly/Lecithin | 4:2 | 77 ± 3 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | 2.8 |

All the formulations were freshly prepared.

TWN 80, Tween 80; GM, Glycerol monostearate; Poly, Poloxamer.

In vitro cell viability studies

To evaluate the efficacy of PEGylated 5FU-SLNs, in vitro cytotoxicity of 5-FU and various PEGylated 5FU-SLN formulations studies were performed against HCT-116 cells for 48 h at different concentrations. Figure 2A shows the effect of increasing concentration of 5-FU along with the six batches (5FU-SLN1, 5FU-SLN2, 5FU-SLN3, 5FU-SLN4.5FU-SLN5 and 5FU-SLN6) to assess the growth inhibition of HCT-116 cancer cells. As shown in Fig. 2, PEGylated 5FU-SLN4 was most effective against HCT-116 cell growth at all concentrations in comparison to the free 5-FU (Fig. 2B) and the five 5FU-SLN formulations (Fig. 2A). To determine the extent of HCT-116 cells sensitivity to 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4, half maximum inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 5-FU and PEGylated 5FU-SLN4 against HCT-116 cells were measured. Figure 2C shows that IC50 value (17.7 ± 0.03 μM) of 5-FU was 2.4 fold-high compared with that of 5FU-SLN4 (7.4 ± 0.02 μM) suggesting that 5FU-SLN4 was significantly effective and would require significantly less concentration to treat HCT-116 cells compared with 5-FU.

In vitro drug release kinetics from PEGylated SLNs

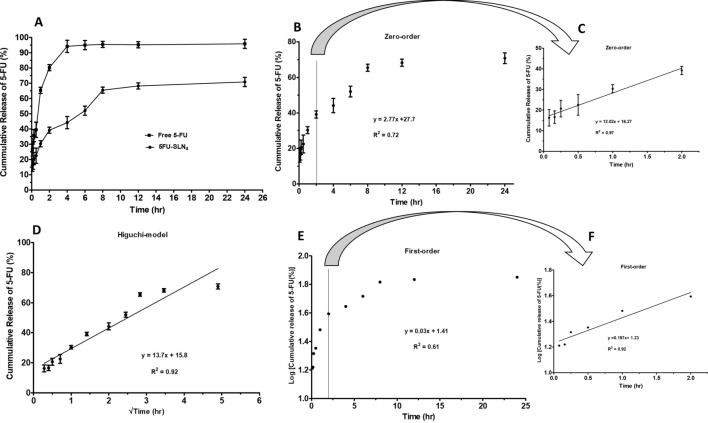

In Fig. 3, the cumulative in-vitro drug release of 5-FU during a 24 h period of incubation at 37 °C was presented. In this case, the dialysis bag method was used to study in vitro evaluation of 5-FU release profile from 5FU-SLN4. The formulation was designed with the expectation that 5-FU was encapsulated and retained within the SLN4. The release of free 5-FU was rapid and almost complete from the dialysis bag with about 80% released just within 2 h and about 90% released within the first 3 h. The free 5-FU release continued until it reached 95% within the first 4 h. This suggests that any free 5-FU placed in the dialysis bag would rapidly diffuse out in a significant amount within a short period of time. In addition, its release profile could be used to differentiate the release pattern of 5-FU from SLN4 as long as sink condition was maintained and diffusion of 5-FU to the receiving medium depended on concentration gradient (Fig. 3A). In comparison to 5-FU release from SLN4, about 40% of 5-FU was released within the first 2 h followed by a gradual or slow release of additional 20% over a period of 6 h and reached steady state at time 8 h. This implies that most of the 5-FU remained entrapped in SLN4 under the study conditions (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

In-vitro release kinetics of 5FU-SLN4: (A) In-vitro cumulative release profile of 5-FU from SLN4 at for 24 h, in which free 5-FU was the control. (B) The release profile of 5-FU exhibiting zero-order kinetics, (C) The release kinetics for the first 2 h (extracted from B), the release followed a linear pattern with R2 = 0.97, (D) The release profile of 5-FU exhibiting Higuchi-model release. The 5-FU release from SLN4 indicates Higuchi-model release with a R2 = 0.92, (E) The release profile of 5-FU exhibiting first-order kinetics, (F) Release kinetics for the first 2 h (extracted from E), the release followed a linear pattern with R2 = 0.92.

To determine the 5-FU diffusion mechanism, in vitro release kinetics of 5-FU from SLN4 was modeled as shown in Fig. 3B,C for zero-order kinetics, Fig. 3D for Higuchi model and Fig. 2E,F for first-order kinetics. The best-fit release mechanism was determined based on the comparison of R2 values of the various kinetic models (Fig. 3B,D,E)19. The R2 value (0.92) of Higuchi model (Fig. 3D) was found to be the highest compared with R2 value (0.72) of zero-order (Fig. 3B) and R2 value (0.61) of first-order (Fig. 3E) based on the 24 h. This suggests that 5-FU released from SLN4 followed Higuchi diffusion kinetics and implies that 5-FU release come from a homogeneous delivery system and diffuses out of the delivery system over a period of time19,20. Figure 3C (R2 = 0.97) and Fig. 3F (R2 = 0.97) were not considered in determining the best-fit model of 5-FU release because the graphs covered only the first 2 h (first six data points).

Flow cytometry and confocal imaging

To further assess PEGylated 5FU-SLN4 cell uptake by HCT-116 cells, flow cytometry analysis was performed. Supplementary Figure S2 shows cellular uptake of SLN as they were tagged with rhodamine (Rho-SLN4) and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. As shown in Supplementary Figure S2 (A and B), flow cytometry data revealed significant Rho-SLN cellular uptake. To further confirm the uptake of PEGylated 5FU-SLN4, HCT-116 cells were treated for 24 h at 37 °C with FITC-labeled SLNs. Confocal images Supplementary Figure S2C of HCT-116 cells showed uptake of FITC-SLN as Hoechst dye was used to counterstain nuclei. The merged image indicated that the solid lipid nanoparticle localized within the cell nuclei.

Clonogenic studies

Clonogenic survival assay was conducted to evaluate in vitro cell survival. The primary goal was to determine the proliferative ability of HCT-116 cell lines after treatment with 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4. As shown in Supplementary Figure S3A, as concentrations of both 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 increases, survival percent decreases. More importantly as 5FU-SLN4 concentration increased from 3 to 25 μM, we observed a significantly decreased colony formation of 5FU-SLN4 treated HCT-116 cells as shown in Supplementary Figure S3B. In contrast, colony formation especially in 6 μM 5-FU treated HCT-116 cells was a remarkably higher than that treated with 5FU-SLN4. The findings seem to suggest that a significant DNA damage might have occurred in 5FU-SLN4 treated cells than that 5-FU and was most likely due to the HCT-116 cells inability to repair DNA and reproduce.

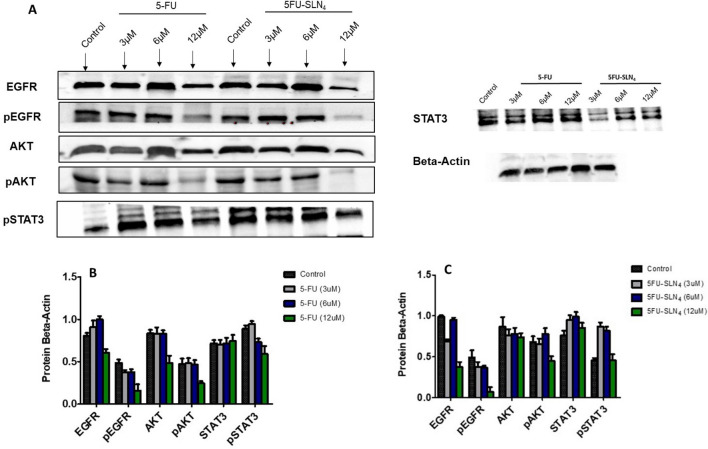

Western blot analysis

Utilizing the inhibitory concentrations (IC50) from viability experiments, we performed protein expression analysis in HCT-116 cells treated with 5-FU and PEGylated 5FU-SLN4 for 48 h. In Fig. 4A protein analysis showed greater dose-dependent reduction of EGFR and AKT phosphorylation with treatment of PEGylated 5FU-SLN4. As studies have shown, EGFR is highly expressed in advanced CRC with associated poor survival21. More importantly, the results indicate that, our developed formulation, PEGylated 5FU-SLN4 appeared to be more effective in targeting EGFR as seen in the reduction of protein expression compared with that of 5-FU treated cells (Fig. 4B,C). Our novel formulation, PEGylated 5FU-SLN4 reduced the expression of both the total and phosphorylated EGFR as well as some of the crucial molecules in the EGFR signaling pathways, activated AKT and STAT3. Such inhibitory effects of 5FU-SLN4 may negatively impacts the signaling through the key transduction pathways activated by EGFR such as RAS, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), Src and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) involved in the control of cell proliferation, survival and differentiation22. Blocking the EGFR-induced activation of the RAS-Raf-MEK-MAP kinase cascade or PI3K-AKT results in the inhibition of transcription factors regulating gene expression, while inactivation of STAT3 prevents dimerization and translocation to the nucleus where they act as transcription factors23.

Figure 4.

Cellular apoptosis by 5FU-SLN4: Western blot analysis shows the protein expression affected after 48 h of treatment with 12 µM of 5FU-SLN4 (A). Beta-Actin was used as a loading control. Effects of 5-FU on protein beta-actin ratio and protein expression in HCT-116 cells (B). Effects of 5FU-SLN4 on protein beta-actin ratio and protein expression in HCT-116 cells (C). Membrane blots were cut to enable blotting for multiple antibodies. Data presented as mean ± SD.

Acute toxicity

Clinical usefulness of 5-FU has been precluded because of its hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic side effects24. In the present study, careful examination of the H&E-stained sections of the liver and kidney of mice treated with 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 (dose: 20 mg/kg) revealed normal histological (hepatic and renal) architecture compared with that of the control mice (Supplementary Figure S4). While other reports indicate loss of normal hepatic and renal architecture of mouse treated with 5-FU (80 mg/kg, dose)25,26, we did not observe any abnormality in hepatocytes and nephrocytes architecture of mice treated with either 5-FU or 5FU-SLN4 (dose: 20 mg/kg). More importantly, at a dose of 20 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 significant CRC tumor growth suppression was observed, suggesting that the dose was tolerable and more effective than the 5-FU in the mice.

Pharmacokinetics

5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 was intraperitoneally dosed (20 mg/kg) with a single bolus administration in mice to evaluate and compare the pharmacokinetic parameters of 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 (at 5-FU equivalent dose). As shown in Table 2, the half-life (t1/2) of 5FU-SLN4 (2.13 ± 0.04 μg/mL * h) was found to be threefold high compared with 5-FU (0.68 ± 0.02 μg/mL * h) with p-value of 0.0001, while area under curve (AUC) of 5FU-SLN4 (54.7 ± 3.2 (μg/mL * h)) was significantly higher than 5-FU (15.5 ± 1.9 μg/mL * h) with p-value of 0.0001. As expected, the plasma clearance () of 5-FU (12.5 ± 1.3 mL/h) was remarkably high compared with 5FU-SLN4 (4.1 ± 0.8 mL/h) with p-value of 0.0007. In comparison with literature on pharmacokinetic profiles of similar 5-FU loaded SLNs formulations, we found that AUC and t1/2 values of our formulation 5FU-SLN4 were significantly greater than in literature27–29. In addition, CL value of 5FU-SLN4 was notably lower than that found in literature27,29. Put together, the results suggest that SLN4 may have prolonged plasma circulation of 5-FU and the observed favorable pharmacokinetics of 5-FU was mostly due to the unique ability of SLN4 to protect and deliver high payload of 5-FU. However, more studies will have to be conducted to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the 5FU-SLN4’s ability to increase the systemic exposure of 5-FU when administered intraperitoneally.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of free 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 upon IP injection in the mice.

| Parameter | Unit | One-compartment model | Significance level p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-FU | 5FU-SLN4 | |||

| ka | 1/h | 1.36 ± 0.02 | 1.91 ± 0.04 | 0.0001 |

| K10 | 1/h | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.0001 |

| t1/2 | h | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 2.13 ± 0.04 | 0.0001 |

| Vd | mL | 14.3 ± 2.8 | 12.6 ± 0.6 | 0.3619 |

| CL | mL/h | 12.5 ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 0.0007 |

| Cmax | µg/mL | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 12.7 ± 0.9 | 0.0005 |

| Tmax | h | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 0.0025 |

| AUC(0 − t) | µg/mL * h | 15.5 ± 1.9 | 54.7 ± 3.2 | 0.0001 |

| MRT | h | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 0.02 |

Cmax, peak plasma concentration; Tmax, peak time; AUC(0 − t), area under the plasma concentration–time curve; MRT, mean residence time; k10, elimination rate constant; Cl, clearance; Vd, volume of distribution; ka, absorption rate constant (Data analyzed using unpaired t-test, two-tailed).

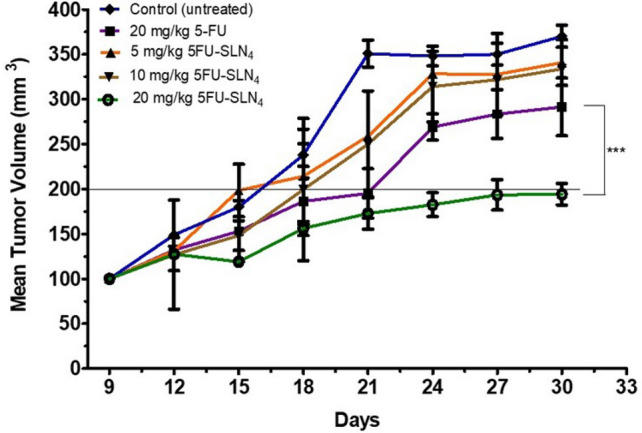

Tumor efficacy studies

The tumor-inhibition study was conducted over a period of 30 days and was concluded when the normalized mean tumor volume of control (untreated) animals reached 375 ± 12 mm3. From Fig. 5, it was clear that 20 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 was more effective in controlling the tumor growth compared to the other treated groups such as 20 mg/kg 5-FU, 5 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 and 10 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4. However, the normalized mean tumor volumes of 20 mg/kg 5FU (300 ± 50 mm3), 5 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 (328 ± 23 mm3) and 10 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 (325 ± 21 mm3) treated groups were significantly less than the control (untreated or normal saline) tumor (375 ± 12 mm3). Although 5 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 and 10 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 treatment groups were included in the tumor efficacy study, our final goal was to investigate the efficacy of 20 mg/kg 5-FU and 20 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 in controlling tumor growth. At the end of the study (30 days), mean tumor volume (200 ± 8 mm3) of 20 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 treated group was significantly lower than the mean tumor volume (300 ± 50 mm3) of 20 mg/kg 5-FU treated group (p < 0.0001).

Figure 5.

Efficacy study: Comparison of anticancer effects of 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 on tumor growth of HCT-116 tumor bearing mice. Data represented as mean ± SD, (number of mice in each treatment group (n) = 4).

Recently, there have been several reports focused on the tumor doubling time (TDT) of cancer30–32 which sought to establish relationship between TDT and cancer prognosis which states that the longer TDT the better the prognosis. In this study, mean tumor volume of 20 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 treated group took 30 days to double while mean tumor volume of 20 mg/kg 5-FU treated group doubled within 21 days. This suggests that 20 mg/kg 5FU-SLN4 might be more effective in suppressing tumor growth compared with 20 mg/kg 5FU. This was expected, given the short half-life of 5-FU (Table 2) which is most likely due to rapid metabolism and the fact that it was administered without any protection. While SLN4 acted as an efficient vehicle or delivery system, it may have afforded 5-FU excellent protection, leading to prolong systemic circulation which may lead to more 5FU-SLN4 to accumulate in tumor site. However, biodistribution studies need to be performed to conclusively determine whether 5FU-SLN4 indeed accumulate to a greater extent in the tumors relative to other tissues. There were no significant weight changes in animals among all the treatment groups during study period, indicating minimum or total lack of apparent toxicity of the administered formulations (Supplementary Fig. S4).

The in vivo evaluations in this study employed a subcutaneous xenograft versus an orthotopic model employed in the study by Tseng et al.33. For future investigations in orthotopic models, the surface of SLN4 delivery system will be grafted with ligand specific to receptors expressed on CRC cells.

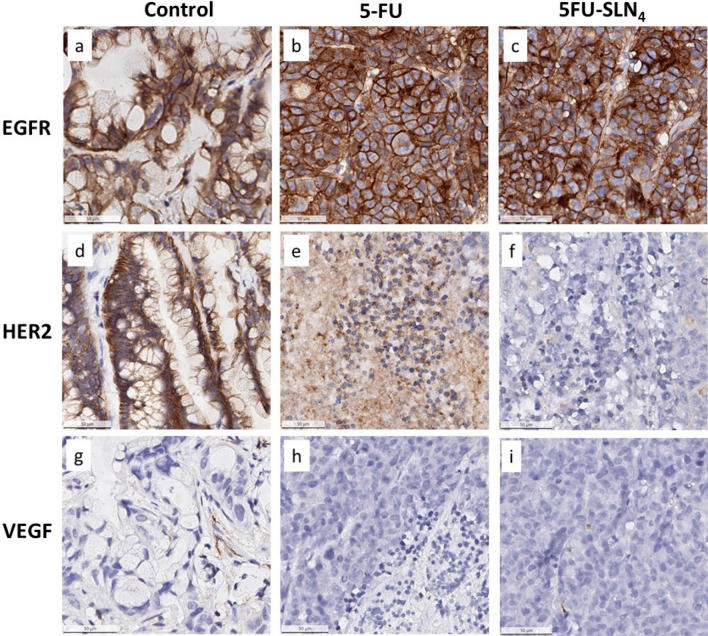

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human EGFR 2 (HER2) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) are tyrosine kinase receptors highly expressed in several solid tumors including CRC34–36. These receptors are frequently reported to harbor aberrant activities that lead to the proliferation, survival, migration and differentiation required for CRC pathogenesis. We therefore evaluated the impact of our novel formulated 5FU-SLN4 on the expression of EGFR, HER2 and VEGFR in the mice xenograft tumors derived from HCT-116 cells (Fig. 6). Immunohistochemistry staining of the tumor tissues indicated intense expression of EGFR in the control untreated (Fig. 6a) as well as 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 treated tissues (Fig. 6b,c). Based on our previous observation on the inhibitory effect of the compounds on EGFR signaling from the western blotting, the only plausible explanation to this increased EGFR expression is a possible compensatory protective response to overcome inhibition of downstream signaling in order to overcome growth suppression and to increase survival37.

Figure 6.

Expression of EGFR, HER2 and VEGF in colorectal cancer tissues. The protein expression of EGFR was positive (a), positive (b), positive (c); protein expression of HER2 was positive (d) positive (e), weak positive (f), and protein expression of VEGF negative (g), negative (h), negative (i), respectively.

The control untreated tissue also showed intense HER2 immunoreactivity indicating relatively high expression of the protein (Fig. 6d). Treatment with 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 caused a significant decrease in HER2 expression as shown in Fig. 6. Specifically, 5-FU-SLN4 was more effective at reducing HER2 expression compared to 5-FU as shown by relatively low immunoreactivity to HER2 in 5FU-SLN4 treated tumor tissues (Fig. 6e,f). Although in general, only trace to weak immunostaining was observed in the tumor tissue for VEGFR (Fig. 6g), immunoreactivity was markedly reduced in both 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 treated tumors (Fig. 6h,i). Significant differences in both HER2 and VEGFR immunoreactivity intensities between the control untreated tissues (Fig. 6d,g) and 5-FU and 5-FU-SLN4 treated tumor (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.001 respectively, Table 3) were observed when the stained sections were further analyzed as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Differential expression of receptors in mice bearing HT-116 subcutaneous cancer after treatment with 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 and staining scores analysis.

| Control | 5-FU | 5FU-SLN4 |

p-value (5-FU versus 5FU-SLN4) |

Significant? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | |||||

| % Positive cells | 76.1 ± 2.2 | 69.1 ± 4.1 | 71.4 ± 2.8 | 0.467 | No |

| % Weak positive cells | 45.1 ± 3.2 | 46.9 ± 2.5 | 33.4 ± 2.6 | ||

| % Moderate positive cells | 24.9 ± 4.2 | 18.9 ± 0.2 | 27.3 ± 1.8 | ||

| % Strong positive cells | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 10.7 ± 0.5 | ||

| % Negative cells | 23.9 ± 4.1 | 30.9 ± 1.7 | 28.6 ± 4.7 | ||

| H score | 113.4 | 94.6 | 119.8 | ||

| HER2 | |||||

| % Positive cells | 80.5 ± 2.8 | 26.9 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| % Weak positive cells | 0.001 | 26.8 ± 3.6 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | ||

| % Moderate positive cells | 10.1 ± 2.2 | 0.1 ± 0.002 | 0.02 ± 0.0 | ||

| % Strong positive cells | 70.4 ± 2.8 | 0.006 ± 0.0 | 0.003 ± 0.0 | ||

| % Negative cells | 20.4 ± 1.8 | 73.1 ± 8.6 | 96.3 ± 1.7 | ||

| H score | 57.9 | 27.1 | 3.7 | ||

| VEGF | |||||

| % Positive cells | 20.5 ± 4.2 | 1.27 ± 0.05 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 0.001 | Yes |

| % Weak positive cells | 11.7 ± 3.2 | 1.23 ± 0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.02 | ||

| % Moderate positive cells | 7.1 ± 1.6 | 0.04 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | ||

| % Strong positive cells | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.0003 ± 0 | 0.25 ± 0.001 | ||

| % Negative cells | 79.5 ± 5.1 | 99.1 ± 1.4 | 97.2 ± 3.6 | ||

| H score | 31.3 | 0.91 | 4.1 | ||

Conclusion

The development of novel delivery system capable of delivering high payload of chemotherapeutic agents across the tumor microenvironment to target cancer cells and enhance therapeutic response has been a challenge or daunting task. 5-FU has shown efficacy in the treatment of cancers but suffers from physico-chemical limitations that restrict its use as a free 5-FU; however, SLN4 developed in this project appeared to be robust and versatile, and seemed to have the desired requisite of novel drug delivery that could be utilized to overcome the limitations encountered by 5-FU and other free anticancer agents. Most importantly, 5FU-SLN4 activity in mouse bearing HCT-116 subcutaneous tumor significantly inhibited the HER2 expression. In literature, HER2 overexpression or amplification has been implicated as one of the drivers in CRC progression34,35. But further investigation of 5FU-SLN4’s biodistribution in vivo needs to be carried out to fully determine its pattern of distribution in tissues relative to tumor tissue.

Finally, the 5FU-SLN4 developed in this project revealed an enhanced in vitro activity, which translated into to a favorable therapeutic efficacy in vivo compared to the free 5-FU.

Materials and methods

Materials

Compritol 888 ATO (glyceryl behenate) and Precirol ATO 5 (glyceryl palmitostearate) were obtained from Gattefosse (Saint Priest, France). Tween 80 (polysorbate 80), Lecithin, glycerol monostearate and 5-FU were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Trevigen HT PARP/Apoptosis Assay kit was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Colorectal carcinoma cell lines, HCT -116, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All other chemicals used were of an analytical reagent grade.

Preparation of PEGylated 5-FU SLN suspension

Different 5FU-SLNs were prepared by means of cold emulsification method using high-shear mixer based on a reported method with slight modifications38 as illustrated in Fig. 1. A combination of PEGylated lipids and surfactants were used in the optimization of 5FU-SLN. The following lipids formed the matrix: glycerol monostearate, mPEG2000-DSPE, Compritol or Precirol (2–3% w/v ratio) and the formulations were stabilized with Tween 80, Lecithin and Poloxamer (1.5–4% w/v ratio).

Lipids with different amounts and 5-FU (0.15% w/v) in a glass vial were heated to 70–80 °C to melt. For the cold homogenization technique, the 5FU-containing lipid melt is cooled, the solid lipid ground to lipid microparticles (approximately 50–100 μm) and these lipid microparticles were dispersed in a cold surfactant solution (water, Tween 80, Lecithin or Poloxamer) to yield a pre-suspension. This pre-suspension was homogenized (1,200 rpm (3,820 rcf), 3–5 cycles) on ice-bath (below room temperature) causing lipid microparticles to break directly to solid lipid nanoparticles. This process avoids or minimizes the melting of the lipid and therefore minimizing loss of hydrophilic drugs to the water phase39. The freshly prepared formulations were used to characterize all the various SLN formulations and, for in vitro and in vivo studies. The selected SLN formulation (5FU-SLN4) was lyophilized with 5% w/v mannitol and stored at 4 °C for future use.

Characterization of SLN formulations

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The morphological examination of the PEGylated 5FU-SLN4 was performed using high resolution TEM. The 3 μl samples were stained with 50 μl of ammonium molybdate solution (1% w/v) after adjusting the 5FU-SLN4 suspension to pH of 7.0 with 5 N sodium hydroxide. The stained sample was then placed on copper grids, allowed to dry and viewed by Tecnai F-20 transmission electron microscope (Philips Co. Japan).

Particle size and zeta potential

All analyzed samples were diluted with deionized water for both particle size and zeta potential measurements using a Zeta Potential/Particle Sizer (NICOMP 380 ZLS). All measurements were performed in triplicate. The NICOMP 380 ZLS measures the nanoparticles based on principles of dynamic light scattering (DLS).

HPLC analysis

5-FU analysis was performed according to method described by Ciccolini and colleagues with minor modification40. Briefly, 5-FU analysis was performed using a chromatographic system, which consisted of a HPLC (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) equipped with an auto-sampler, photo diode array (2998 UV/Vis) detector and pumps. Separation was performed using a reverse phase column (ZORBEX SB—C18 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm).

A flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and injection volume 20 μl at ambient temperature were maintained while detection was performed at wavelength of 268 nm41. Prior to analysis, reverse phase column was equilibrated with mobile phase made up of methanol 5 mM sodium phosphate buffer in ratio of 595, and pH adjusted to 542. An isocratic elution was performed throughout the entire analysis including internal standards.

A calibration curve was prepared using 5-FU standard solutions with concentration range of 3–100 µg/mL (r = 0.9). A plot of the peak areas as a function of 5-FU concentration was plotted and the linear equation of the calibration curve given as y = mx + c was determined, where y is the peak area, m is the slope, x is the concentration of 5-FU and c is the y—intercept. Supernatants from controls were spiked with aliquots of 0.5 μg/ml of 5-FU.

Encapsulation efficiency (%)

The entrapment efficiency (E.E) corresponds to the amount of drug incorporated in the nanoparticle. Entrapment efficiency analysis was performed by adding 1 mL of loaded SLN to 1 mL of methanol. The mixture was placed into the chamber of the ultrafiltration tube and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 6 min. After centrifugation, the non-entrapped drug amount in the supernatant was collected and ran on HPLC analysis to estimate the amount of 5-FU present in the sample. The E.E was calculated using the following equation:

| 1 |

In vitro release of 5-FU

The cumulative release of 5-FU from the solid lipid nanoparticles was performed at 37 ± 1 °C. Twenty milligrams (20 mg) of lyophilized 5FU-SLN4 was suspended in 1.0 ml of PBS (pH = 7.4), transferred into a dialysis bag (MWCO = 3,500) and incubated in 5 ml of PBS pre-equilibrated to temperature (37 ± 1 °C). One milliliter (1.0 ml) was collected at selected time points and replaced with 1.0 ml of fresh PBS. Collected samples were analyzed by HPLC–UV/Vis spectrophotometry to determine the amount of 5-FU released at different time points43.

Mathematical models to determine 5-FU release kinetics

The release kinetics of 5-FU from the heat sensitive liposomes was investigated to predict the possible mechanism of release using mathematical models. The release order was determined using zero order (Eq. 2) and first order kinetic model as shown below.

| 2 |

| 3 |

where Co is the initial amount of drug, C is the % cumulative 5-FU released (zero order) or first order (Eq. 3) at time “t” and Ko is zero order release constant and K1 is the first order release constant44.

A Higuchi model was used determine whether the release mechanism follows Fickian diffusion as shown below20:

| 4 |

where C is the % cumulative 5-FU release at time, t and KH is the Higuchi constant.

Cytotoxicity of PEGylated 5FU-SLNs against HCT-116 cells

Cell Viability: Cell viability study was performed using 96-well plates and evaluated by Alamar Blue assay. The HCT-116 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 103 cells/well. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F-12 medium enriched with L-glutamine, HEPES, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After cells were grown to 70% confluence, they were treated with freshly prepared treatments at different concentrations of 5-FU-SLN and 5-FU equivalents. Cells were treated for a 48-h period followed by termination, stained with 0.05% resazurin, gently mixed and incubated in the dark for 2–3 h before measurement of the fluorescence with excitation at 560 nm and emission at 590 nm using GloMax Explorer Microplate Reader (Promega Biotech, Madison, WI).

Cellular uptake of FITC-labeled PEGylated SLNs

Confocal imaging

HCT-116 cancer cells were grown in 6-well plates (with cover slips) at a cell density of 2 × 103, for 24 h at 37 °C45. The cells were then treated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled SLN4 in growth media. After 3 h, FITC-SLN4 was removed and the cells gently washed twice with PBS. Next, 5 μg/ml of Hoechst dye was added for nuclear staining, the cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, then mounted and imaged using Leica SP2 Multiphoton system45.

Flow cytometry

To determine 5-FU-loaded solid lipid nanoparticle uptake by the cells, HCT-116 cells were grown in 6-well plates at a cell density of 1 × 105 and cultured in growth media until 70% confluence45. Cells were treated with the rhodamine-labeled solid lipid nanoparticles (Rho-SLN) for 24 h at 37 °C. After treatment, the adherent cells were washed three times with PBS, detached from the culture plate with 0.25% trypsin- ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution, and centrifuged at 6,000 rpm (3820 rcf) for 5 min45. Finally, the cells were re-suspended in 500 μl PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and kept on ice until analysis using a Becton Dickinson (BD) Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Canto Analyzer and a BD Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Aria Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences)45.

Clonogenic study

For colony assay, HCT-116 cells were seeded into T-25cm2 culture flask at a density of 5 × 105 cells and cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin45. After the cells reached 70% confluency, they were exposed to different concentrations of free 5-FU and 5FU-SLN445. Treatment was repeated after 24 h for 48 h exposure after which the experiment was terminated, cells harvested, and then re-plated onto 6-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells per well and incubated with growth medium for 7 days45. After the control cells reached 75% confluence, the experiment was terminated by fixing and staining the plates with 0.5% crystal violet solution45. The stained colonies (fifty per colony) were counted using a Jenco Stereomicroscope.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis were conducted by seeding (1 × 106) HCT-116 cells into 75 cm2 flask. The cells were treated with 3, 6 and 12 µM of 5FU-SLN4. After a 48 h period, treatment was terminated through trypsinization, cell pellets were collected after centrifugation and washed 3 times. The cell pellet was collected in microcentrifuge tubes and lysed with RIPA buffer supplemented with 1% Protease inhibitor cocktail (Millipore Sigma, St Louis, MO). Samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 14,000 rpm (3,820 rcf) and the supernatant stored at − 20 °C until further used. Lysates containing 100 μg of protein were mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, placed in boiling water bath for 5 min and separated by Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, CA) overnight46. After blocking, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight and then horseradish-peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:1,000; Cell Signaling, MA, USA) were added for 1 h at RT46. Chemiluminescence images were captured using the ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad, CA).

Cutting of membranes

To enhance the detection of multiple proteins, membranes were cut into individual strips for better detection with different antibodies prior to imaging.

Western Blot bands were quantified by densitometric analysis using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and GraphPad Prism version 6. The primary and secondary antibodies were: EGFR (1:1,000, sc-373746; Santa Cruz Dallas, TX), pEGFR (1:1,000, 2234) (Cell Signaling, MA), STAT3 (1:1,000, 9139; Cell Signaling, MA), pSTAT3 (1:1,000, 9134; Cell Signaling, MA), AKT (1:1,000, 9272; Cell Signaling, MA), pAKT (1:1,000, 9271; Cell Signaling, MA). Anti-Beta-Actin (1:1,000, sc-517582; Santa Cruz Dallas, TX) served as loading control for protein normalization. The experiments were performed at least two times.

Animal studies

NOD/Scid mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in a virus-free, indoor, light and temperature-controlled environment provided with adequate food and water. All procedures with animals were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Florida A&M University Animal Care and Use Committee. Colorectal HCT-116 cancer cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C47.

Mice were inoculated with HCT-116 cells (5.7 × 106 in 150 μl PBS) and injected subcutaneously in the lower flanks of NOD/Scid mice48,49. Prior to the tumor appearance within two weeks of inoculation, mice were grouped into 6 groups with 5 mice in a group [control, 5-FU, 5FU-SLN4 (5 mg/kg), 5FU-SLN4 (10 mg/kg) and 5FU-SLN4 (20 mg/kg)]. The mice were administered with selected formulations for 2 weeks, every other day via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection50. The control group received normal saline throughout the study. Tumor measurements were taken every other day using a digital Vernier caliper throughout the experiment. Mice were euthanized when tumor size reached 2.0 cm.

Pharmacokinetic studies

A group of mice were injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of 20 mg/kg of 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 (at 5-FU equivalent dose). Blood samples were taken from the tail vein of mice at different time points (5 min, 10 min, 15 min, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h). The samples were placed in heparinized centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 8–10 min. The plasma was then stored at − 20 °C until analysis.

Assay validation and recovery

A calibration curve was prepared using the peak areas of 5-FU against the respective concentrations of 5-FU. Linear regression analysis of the calibration data was performed using the equation y = mx + c, where y is the peak area, x is the concentration of 5-FU, and m and c are the slope and intercept, respectively51. The recovery of 5-FU from plasma or tissue samples was determined by comparing the peak areas from the samples containing known added 5-FU with those from 5-FU standard solutions51.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were euthanized and tissue samples (tumor, liver and kidney) were excised from mice immediately, washed with PBS and placed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h and transferred to 70% ethanol for histopathological analysis. Histology was performed by HistoWiz Inc. (histowiz.com) using a Standard Operating Procedure and fully automated workflow. Samples were processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4 μm52–54. Immunohistochemistry was performed on a Bond Rx autostainer (Leica Biosystems) with enzyme treatment (1:1,000) using standard protocols. Antibodies used were rat monoclonal F4/80 primary antibody (eBioscience, 14-4801, and 1:200) and rabbit anti-rat secondary (Vector, 1:100)52–54. Bond Polymer Refine Detection (Leica Biosystems) was used according to manufacturer’s protocol. After staining, sections were dehydrated and film coverslipped using a Tissue-Tek Prisma and Coverslipper (Sakura). Whole slide scanning (40 ×) was performed on an Aperio AT2 (Leica Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated using software Pharmacokinetic Solutions 2.0 (PK Solver). The difference between 5-FU and 5FU-SLN4 treatment groups were analyzed using paired Student’s t-test and considered significant at p < 0.05. All experiments were performed at least in triplicate and analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Numbers U54MD007582, U54CA233396-01 and 5P20CA192990-04. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

E.A., J.T. and T.S designed experiments, collected, analyzed, interpreted the data and wrote the main manuscript text. K.A. contributed to design of experiments. E.N. contributed to the work and performed western blot analysis. F.A., B.H. and S.K. provided data analysis and interpretation. E.A., J.T. and S.K. conceived the concept development and design, provided materials, analysis of results and manuscript write-up. All authors reviewed the revised manuscript and provided valuable insight and edits.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information Files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-73218-6.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doubeni CA. Early-onset colorectal cancer: what reported statistics can and cannot tell us and their implications. Cancer. 2019;125:3706–3708. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gulbake A, Jain A, Jain A, Jain A, Jain SK. Insight to drug delivery aspects for colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:582–599. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richarlm. Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month (2019). https://yourhealthradio.org/2019/03/20/colorectalcancer-awareness-month/. Accessed 18 June 2019.

- 5.Udofot O. Cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil-loaded pH-sensitive liposomal nanoparticles in colorectal cancer cell lines. Integr. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2015;2:245. doi: 10.15761/icst.1000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gokare P, et al. P53 represses pyrimidine catabolic gene dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD) expression in response to thymidylate synthase (TS) targeting. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9711. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09859-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latchman J, Guastella A, Tofthagen C. 5-Fluorouracil toxicity and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase enzyme: implications for practice. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014;18:581–585. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.581-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Pinel B, et al. Lipid-based nanoparticles: application and recent advances in cancer treatment. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2019;9:2. doi: 10.3390/nano9040638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carla Vitorino FAC, Almeida AJ, Sousa JJ, Pais AA. The size of solid lipid nanoparticles: an interpretation from experimental design. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2011;84:117–130. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pooja D, Tunki L, Kulhari H, Reddy BB, Sistla R. Optimization of solid lipid nanoparticles prepared by a single emulsification-solvent evaporation method. Data Brief. 2016;6:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2015.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong HL, Bendayan R, Rauth AM, Li Y, Wu XY. Chemotherapy with anticancer drugs encapsulated in solid lipid nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007;59:491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daly, M. C. & Paquette, I. M. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) and SEER-medicare databases: Use in clinical research for improving colorectal cancer outcomes. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg.32, 61–68 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Ashwanikumar N, Kumar NA, Asha Nair S, Vinod Kumar GS. Dual drug delivery of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and methotrexate (MTX) through random copolymeric nanomicelles of PLGA and polyethylenimine demonstrating enhanced cell uptake and cytotoxicity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2014;122:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Tang J, Li C, Kong J, Wang J, Wu Y, Xu E, Lai M. MiR-22 regulates 5-FU sensitivity by inhibiting autophagy and promoting apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandran SP, Natarajan SB, Chandraseharan S, Shahimi MSBM. Nano drug delivery strategy of 5-fluorouracil for the treatment ofcolorectal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Pract. 2017;4:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrpr.2017.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganesan P, Narayanasamy D. Lipid nanoparticles: different preparation techniques, characterization, hurdles, and strategies for the production of solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers for oral drug delivery. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2017;6:37–56. doi: 10.1016/j.scp.2017.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacheen Kumar JKR. High melting lipid based approach for drug delivery: solid lipid nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013;33:1842–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalaycioglu GD, Aydogan N. Preparation and investigation of solid lipid nanoparticles for drugdelivery. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016;510:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siepmann J, Siepmann F. Mathematical modeling of drug dissolution. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;453:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siepmann J, Peppas NA. Higuchi equation: derivation, applications, use and misuse. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;418:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Italiano A, Saint-Paul M-C, Caroli-Bosc F-X, Francois E, Bourgeon A, Benchimol D, Gugenheim J, Michiels J-F. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) status in primary colorectal tumors correlates with EGFR expression in related metastatic sites: biological and clinical implications. Ann. Oncol. 2005;16:1503–1507. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turke AB, et al. MEK inhibition leads to PI3K/AKT activation by relieving a negative feedback on ERBB receptors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3228–3237. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong A, Yang Z, Shen Y, Zhou J, Shen Q. Transcription factor STAT3 as a novel molecular target for cancer prevention. Cancers. 2014;6:926–957. doi: 10.3390/cancers6020926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Sayyad HI, et al. Histopathological effects of cisplatin, doxorubicin and 5-flurouracil (5-FU) on the liver of male albino rats. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009;5:466–473. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baek JH, et al. Unpredicted severe toxicity after 5-fluorouracil treatment due to dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2006;21:43–45. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2006.21.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meta-Analysis Group In, C et al. Toxicity of fluorouracil in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: effect of administration schedule and prognostic factors. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998;16:3537–3541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu BT, Sun X, Zhang ZR. Enhanced liver targeting by synthesis of N1-stearyl-5-Fu and incorporation into solid lipid nanoparticles. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2003;26:1096–1101. doi: 10.1007/bf02994764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S, Wang A, Jiang W, Guan Z. Pharmacokinetic characteristics and anticancer effects of 5-fluorouracil loaded nanoparticles. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du B, Yan Y, Li Y, Wang S, Zhang Z. Preparation and passive target of 5-fluorouracil solid lipid nanoparticles. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2010;15:346–353. doi: 10.3109/10837450903246390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi SJ, Kim HS, Ahn SJ, Jeong YM, Choi HY. Evaluation of the growth pattern of carcinoma of colon and rectum by MDCT. Acta Radiol. 2013;54:487–492. doi: 10.1177/0284185113475923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun S, Klebaner F, Tian T. A new model of time scheme for progression of colorectal cancer. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014;8(Suppl 3):S2. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-S3-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ota DM, Drewinko B. Growth kinetics of human colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2128–2131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tseng W, Leong X, Engleman E. Orthotopic mouse model of colorectal cancer. J. Vis. Exp. 2007;10:484. doi: 10.3791/484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siena S, et al. Targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) oncogene in colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:1108–1119. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang XY, et al. Significance of HER2 protein expression and HER2 gene amplification in colorectal adenocarcinomas. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019;11:335–347. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i4.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bendardaf R, El-Serafi A, Syrjanen K, Collan Y, Pyrhonen S. The effect of vascular endothelial growth factor-1 expression on survival of advanced colorectal cancer patients. Libyan J. Med. 2017;12:1290741. doi: 10.1080/19932820.2017.1290741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinway SN, Dang H, You H, Rountree CB, Ding W. The EGFR/ErbB3 pathway acts as a compensatory survival mechanism upon c-Met inhibition in human c-Met+ hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0128159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poovi Ganesana DN. Lipid nanoparticles: different preparation techniques, characterization, hurdles, and strategies for the production of solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers for oral drug delivery. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2017;6:37–56. doi: 10.1016/j.scp.2017.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller RH, Schwarz C, Mehnert W, Lucks JS. Production of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery. Proc. Int. Symp. Control Release Bioact. Mater. 1993;20:480. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciccolini J, et al. A simple and rapid high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) method for 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) assay in plasma and possible detection of patients with impaired dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) activity. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2004;29:307–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2004.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zatta KC, et al. An inhalable powder formulation based on micro- and nanoparticles containing 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Nanomaterials Basel. 2018;8:75. doi: 10.3390/nano8020075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang N, Wang T, Wang M, Hao A, Li T. Using ultrafiltration to facilitate simultaneous quantification of 5-fluorouracil in mouse plasma and tissues by HPLC. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2011;34:2033–2047. doi: 10.1080/10826076.2011.583372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel MN, et al. Characterization and evaluation of 5-fluorouracil-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles prepared via a temperature-modulated solidification technique. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014;15:1498–1508. doi: 10.1208/s12249-014-0168-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dash S, Murthy PN, Nath L, Chowdhury P. Kinetic modeling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Pol. Pharm. Drug Res. 2010;67:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Udofot O, Affram K, Israel B, Agyare E. Cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil-loaded pH-sensitive liposomal nanoparticles in colorectal cancer cell lines. Integr. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2015;2:245–252. doi: 10.15761/icst.1000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moser JJ, Chan EK, Fritzler MJ. Optimization of immunoprecipitation-western blot analysis in detecting GW182-associated components of GW/P bodies. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:674–685. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayinde O, Wang Z, Pinton G, Moro L, Griffin M. Transglutaminase 2 maintains a colorectal cancer stem phenotype by regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 2019;10:4556–4569. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.27062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hao GW, et al. Growth of human colon cancer cells in nude mice is delayed by ketogenic diet with or without omega-3 fatty acids and medium-chain triglycerides. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015;16:2061–2068. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.5.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McIntyre RE, Buczacki SJ, Arends MJ, Adams DJ. Mouse models of colorectal cancer as preclinical models. BioEssays. 2015;37:909–920. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hare JI, et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer using a combination of liposomal irinotecan (Irinophore C) and 5-fluorouracil. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Udofot O, et al. Pharmacokinetic, biodistribution and therapeutic efficacy of 5-fluorouracil-loaded pH-sensitive PEGylated liposomal nanoparticles in HCT-116 tumor bearing mouse. J. Nat. Sci. 2016;2:e171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harder J, et al. EGFR and HER2 expression in advanced biliary tract cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4511–4517. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pignochino Y, et al. Targeting EGFR/HER2 pathways enhances the antiproliferative effect of gemcitabine in biliary tract and gallbladder carcinomas. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:631. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walsh N, et al. EGFR and HER2 inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Invest. New Drugs. 2013;31:558–566. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9891-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information Files.