Abstract

Placental site trophoblastic tumour (PSTT) is a very rare form of gestational trophoblastic disease that grows slowly, secretes low levels of beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), presents late-onset metastatic potential and is resistant to several chemotherapy regimens. Here, we report a case of PSTT in a 36-year-old woman who presented with amenorrhea and persistently elevated serum level of β-hCG after a miscarriage. Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a hypovascular ill-defined solid lesion of the uterine fundus and MRI showed a tumour infiltrating the external myometrium with discrete early enhancement and signal restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging. PSTT was suspected, and after endometrial biopsy by hysteroscopy and posterior hysterectomy, microscopic examination allowed the final diagnosis. The level of β-hCG dropped significantly in about a month after surgical treatment. Due to the rarity of PSTT, reporting new cases is crucial to improve the diagnosis and managing of these patients.

Keywords: gynecological cancer, radiology, pathology

Background

Placental site trophoblastic tumour (PSTT) is the rarest form of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD), with an estimated incidence of 1/100 000 pregnancies1–3 and accounting for 0.25%–5% of all GTD.4 PSTT typically occurs in women of reproductive age and it is secondary to any pregnancy, arising months to years after a term delivery, an abortion, an ectopic pregnancy or a molar pregnancy.5–8 Patients usually present with amenorrhea, irregular vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain.3 6 9 10

Remarkably, no more than 300 cases of PSTT have been reported.4 6 9 11 Due to this small number and absence of specific clinical or imaging features, the preoperative diagnosis is challenging and pathological examination is required. Also, information about prognosis, optimal management and long-term outcome is consequently restricted. Imaging plays a crucial role in assessing the local extent of disease and surveillance.12 The present report describes a case of PSTT and reviews the imaging features of this type of tumours.

Case presentation

A 36-year-old G3P2 woman was referred to our institution with a history of amenorrhea and persistently positive serum beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) after a spontaneous complete miscarriage around 6 weeks of gestation, confirmed by ultrasound and with any intervention, 15 months ago. She was using an etonogestrel implant for the last 12 months. Routine blood tests showed elevated values of β-hCG (52.9 mIU/mL) and all other results were within normal limits. The patient did not have a significant medical history and the gynaecological examination was unremarkable. Due to these findings, pelvic and transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) were requested.

Investigations

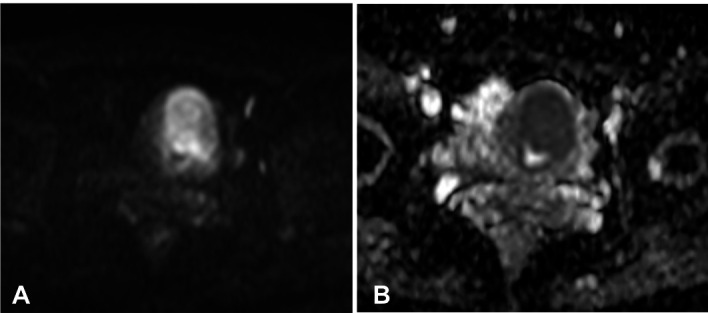

The pelvic and TVUS demonstrated the absence of a gestational sac in the uterine cavity, with an ill-defined solid tumour in the uterine fundus (figure 1A) which was hypovascular on colour Doppler imaging (figure 1B). Uterine dimensions were 78×32×38 mm, with a global shape. An MRI scan of the abdomen and pelvis was requested in order to characterise further this lesion. MRI demonstrated a solid tumour in the uterine fundus, extending to the external myometrium (figure 2A) and measuring about 34×26×23 mm. The tumour was slightly hyperintense on T2 comparing to the uterine myometrium (figure 2B) and revealed discrete early enhancement on dynamic sequences (figure 2C). Diffusion-weighted imaging showed restricted diffusion with high signal on b1000 image (figure 3A) and low signal intensity on apparent diffusion coefficient map (figure 3B), in keeping with dense cellularity of the lesion. Both ovaries were normal. No adenopathy, suspicious bone lesions or free fluid were detected.

Figure 1.

(A) Transvaginal sonography with a 10 MHz endocavitary probe (midline axial view) shows an ill-defined solid tumour on the left wall of the uterine fundus (white arrows). (B) Transvaginal ultrasound with colour Doppler (midline sagittal view) demonstrates minimal blood flow of the lesion.

Figure 2.

(A) Sagittal T2-weighted image reveals a solid tumour in the uterine fundus and infiltrating the external myometrium (white arrow). (B) Axial oblique (perpendicular to the long axis of endometrial cavity) T2-weighted image shows that the tumour was slightly hyperintense on T2 (white arrow) comparing to the uterine myometrium (yellow arrow). (C) Axial oblique T1-weighted image with fat suppression, obtained 25 s after contrast medium injection, demonstrates early tumour enhancement (white arrow). (Philips Intera Pulsar 1.5T: T2-weighted sagittal image (Repetition time (TR)=3825; Echo time (TE)=100); T2-weighted axial image (TR=3684; TE=105); dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI obtained with a T1-weighted sequence (TR=5.76; TE=2.79), with fat suppression and after the administration of 0.1 mmol/kg of gadopentetate dimeglumine at a rate of 2 mL/s.)

Figure 3.

(A) In the axial diffusion-weighted MRI, the tumour shows high signal intensity. (B) In the axial apparent diffusion coefficient map, the area of high signal intensity in the diffusion-weighted MRI shows low signal intensity, a finding that is consistent with restricted diffusion. (Philips Intera Pulsar 1.5T: axial diffusion-weighted images (TR=2616; TE=72.1); Flip angles of 90o, performed with b values of 1000 s/mm2.)

At the time of the referral to our institution, serum β-hCG levels were 129 mIU/mL. The persistent elevated serum β-hCG and imaging findings suggested PSTT. Therefore, hysteroscopic endometrial biopsy was performed.

Histological examination (figure 4) showed the endometrial mucosa involved by a compact, highly cellular proliferation, consisting predominantly of large mononucleated cells with abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm—intermediate trophoblast cells. Much less frequent scattered multinucleated cells with denser cytoplasm—syncytiotrophoblast cells—were identified. Rare mitotic figures were present and cytologic atypia was inconspicuous. Also, villous structures and necrosis were absent. Immunohistochemical study revealed diffuse human placental lactogen expression (not shown) and β-hCG production by syncytiotrophoblast cells (figure 5A), in keeping with its serum levels. Intermediate trophoblast cells expressed AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, CD10 and MUC4. Expression of p63 or α-inhibin was absent (not shown) and proliferation index evaluated by Ki67 expression (figure 5B) was about 5%–10%.

Figure 4.

Highly cellular proliferation with predominance of intermediate trophoblast cells and scattered syncytiotrophoblast cells (arrows). Ectatic vessels (*) in an otherwise poorly vascular tumour. Inset: further cytologic detail of the lesional cells and spiral endometrial artery (**) (low magnification image).

Figure 5.

(A) Beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin production by scattered cells (arrows), confirming their syncytiotrophoblastic nature. (B) Low Ki67 (estimated between 5% and 10%), in contrast to the usually higher than 10% proliferation fraction of epithelioid trophoblastic tumours and very high proliferation fraction of choriocarcinomas (typically >90%) (medium magnification images).

A chest CT was requested, which showed no evidence of metastases. Surgical excision of the tumour was proposed and total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy was then performed.

Macroscopic examination of the surgical specimen (figure 6) showed a well-demarcated nodular lesion of 2.5 cm in the greatest axis centred around the endometrial cavity and extending to the external half of the myometrium, sparing the serosa. The mass was homogeneously solid and white-yellowish. The histological examination confirmed the features observed in endometrial sampling, namely the absence of villous structures and necrosis. Uterine cervix and surgical margins were not involved by the lesion. The histopathological investigation was crucial to reach the final diagnosis, a PSTT.

Figure 6.

(A) Fleshy homogeneous lesion situated around the endometrial cavity; (B) expansive, well-demarcated growth of the lesion within the myometrium.

Differential diagnosis

This patient presented with a solid tumour of the uterine fundus with a history of persistently elevated serum β-hCG after a miscarriage; in this setting, the differential diagnosis of PSTT is made with other forms of GTD as invasive hydatidiform mole, epithelioid trophoblastic tumour (ETT) or choriocarcinoma.

Invasive hydatidiform moles are locally invasive non-metastatic neoplasms. Typical presentation includes markedly elevated β-hCG levels and the characteristic findings on imaging are a poorly defined tumour with tiny cystic foci within the well-enhanced zone of trophoblastic proliferation.3 They develop in approximately 10% of women after treatment for complete/partial hydatidiform mole, unlike the PSTT, which are more common after non-molar pregnancies.3 13 14

PSTT and ETT are the rarest group of GTD, that should be suspected if the β-hCG level is relatively low for the volume of disease detected at imaging.15 Both tumours consist almost exclusively of intermediate trophoblast tissue and it is thought that they have similar behaviour.16 However, in this case, the morphology was not squamoid and immunohistochemical study showed no expression of p63 and α-inhibin, excluding the hypothesis of ETT.

As PSTT, choriocarcinoma can arise after any pregnancy and usually presents with abnormal vaginal bleeding.5 However, in choriocarcinoma β-hCG serum levels are higher, the tumour has an abundant blood supply and high proliferation index/Ki67.2 3

Treatment

Considering the patient’s age, abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy without oophorectomy were performed. No para-aortic or pelvic lymph nodes were detected during surgery and for that reason, lymphadenectomy was not accomplished. The etonogestrel implant was also removed.

Both the surgery and post-operative period were uneventful and the value of β-hCG dropped significantly until reaching a level of <1.0 mIU/mL in about a month after the surgery.

Outcome and follow-up

PSTT is potentially highly curable when the disease is confined to the uterus and the treatment is implemented quickly and appropriately.10 17 As the majority of PSTTs manifest as lesions confined to the uterus, these cases can achieve a complete remission with surgery alone and the prognosis is very good.1 9 18 Some studies have shown that the probability of overall and recurrence-free survival 10 years after treatment was 70%10 18; in contrast, 10%–15% of cases were malignant at presentation7 10 and mortality can reach up to 25% if metastasis occurs.4 10 19 The tumour may metastasise to lung, lymph nodes, liver, brain or other organs, and metastasis can occur years after the diagnosis.6 7 12 20 21 The most common site of metastasis is the lung, with an incidence at diagnosis of 10%–29% and, in general, patients with lung metastases are at increased risk of central nervous system metastases.12

PSTT could be staged according to the anatomical staging of trophoblastic tumours of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2000—table 1.5 11 22 These stages guide the treatment and are related to survival rates, with long term survival (~90% at 10 years) expected for stage I low-risk disease after hysterectomy.15 23 Furthermore, some risk factors associated with the prognosis have been described, including metastases out of the uterus, PSTT >4 years following the prior pregnancy, FIGO stage III–IV disease, woman aged over 40 years and tumour cells exhibit high-grade histological features, such as deep myometrial invasion (>50%), a high mitotic figure (>5/10 high power field (HPF)), cells with clear cytoplasm, coagulative necrosis or involvement of the vascular space.10 12 However, there is still controversy for potential prognostic factors and further studies are warranted to determine the significance of each one.4

Table 1.

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) anatomic staging of gestational trophoblastic disease22

| Stage | |

| I | Disease confined to the uterus. |

| II | Disease extends outside of the uterus but is limited to the genital structures (adnexa, vagina, broad ligament). |

| III | Disease spread to lungs, with or without known genital tract involvement. |

| IV | All other metastatic sites. |

Overall, this case is a stage I disease with some good prognostic factors (patient’s age and absence of metastases), but at least one poor prognosis factor (deep myometrial invasion), which makes the prognosis not entirely clear.

There is no available data regarding the best schedule of follow-up. A recent study suggests at least weekly β-hCG level monitoring for 6 weeks (after normalisation), followed by 12 months at least monthly. After that, the frequency can be reduced until it reach 10 years of follow-up.15 In patients who had only a slightly elevated β-hCG at presentation, this marker alone cannot be used to detect recurrence and additional imaging follow-up should be considered.15

Discussion

GTD is a heterogeneous group of conditions characterised by abnormal proliferation of trophoblastic tissue.15 24 Risk factors for GTD seem to be related to hormonal factors, since extremes of maternal age, women with poor menstrual flow, menarche after 12 years of age or a prior use of oral contraceptive are at increased risk.5 11 13 PSTT originates from a neoplastic proliferation of intermediate trophoblast cells with a relative scarcity of the syncytiotrophoblast cells, causing serum levels of β-hCG much lower than in another GTD.1 11 21

Investigation of these tumours usually starts with anamnesis, physical examination, laboratory tests and among the imaging techniques, TVUS plays a crucial role in the initial evaluation. Ultrasound findings are not specific but when performed by an expert, TVUS can localise the tumour, predict the stage of the disease and evaluate the local invasion.11 The primary tumour site is almost always located in the uterine corpus or fundus, and only few cases of cervical location have been described.6 11 It is typically a slow-growing tumour comparing with other types of GTD, but it can extends into adjacent structures.11 25 PSTT is classified in three different types according to the characteristics observed on TVUS: type I are heterogeneous solid masses in the uterine cavity, with minimal to moderate degree of vascularisation on colour Doppler; type II are heterogeneous solid masses in the myometrium, with minimal to high degree of vascularisation; and type III are cystic lesions in the myometrium with a high degree of vascularisation.11 21 According to this classification, our case is a type II, because the solid mass extends to the external myometrium and has minimal degree of vascularisation (figure 1B).

In the case of tumours that are poorly visualised at the ultrasound, MRI is particularly useful to locate the tumour, accurately determine the depth of myometrial invasion and loco-regional extension, thus allowing the guidance of treatment.6 11 In our case, since the patient had no neurological symptoms or pulmonary metastases, brain MRI was not requested. However, according to recent international guidelines,15 minimal requirements to the diagnosis and staging of these tumours include not only pelvic MRI but also thoraco-abdominal CT and brain MRI to exclude metastatic disease.

Any new case of PSST should be reported to International Database of Rare Trophoblastic Tumours of the International Society for the Study of Trophoblastic Disease and to local GTD centre, if available.15

PSTT cells invade uterine muscle fibres and tend to spread through lymphatic pathways, causing relative resistance to chemotherapy.4 10 26 Due to this characteristic, surgery is the most appropriate treatment, usually total hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.1 2 10 13 18 The role of lymphadenectomy is still controversial.23 26 In young women, preservation of ovaries is recommended, not only because ovarian metastases are uncommon, but also because oophorectomy does not improve prognosis or prevent post-operative extrauterine metastases.4 10 18

The treatment of PSTT is guided by the interval from the previous pregnancy.15 In stage I and the last pregnancy <48 months, hysterectomy and surveillance are recommended. In case of stage I and an interval ≥48 months, adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy can be introduced after surgery. In stage II/III with last pregnancy <48 months, hysterectomy followed by platinum-based combination chemotherapy is recommended and the resection of any visible residual disease should be performed. In case of an interval ≥48 months or stage IV (regardless of interval), besides that, also a high dose chemotherapy can be pondered.15

Fertility sparing surgery is experimental and may include focal resection of the tumour and/or chemotherapy.15 Some of these cases have been reported; however, in many of them, an additional hysterectomy was subsequently required.6

The present case highlights the difficulties encountered in diagnosing and treating PSTT and emphasises the importance of reporting any new cases to better characterisation of this rare disease and to achieve a more consistent approach for managing these patients.

Learning points.

Placental site trophoblastic tumour (PSTT) should be suspected in patients with solid intrauterine lesions who present amenorrhea or irregular vaginal bleeding and a mildly persistent elevated level of serum beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG).

PSTT diagnosis is challenging and routinely requires a combination of serum β-hCG testing, as well as radiological and pathological examination.

PSTT differs deeply from other gestational trophoblastic diseases due to a particular clinical behaviour such as slow growth, late-onset metastatic potential and relative resistance to chemotherapy regimens, which requires peculiar diagnostic strategies and therapeutic options.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Ana Félix (Pathologist) and Dr Andreia Relva (Gynaecologist) who, as part of the multidisciplinary team, helped in the characterisation of the lesion and surgical treatment, respectively, of the patient here described. They also thank the patient for allowing them to write up her case.

Footnotes

Contributors: MMC developed the concept, captured the images and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors; TM performed the pathological analysis and captured the histological and surgical specimen pictures; TMC captured the images and gave expert opinion and VFV contributed in the management of the patient. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Niknejadi M, Ahmadi F, Akhbari F. Imaging and clinical data of placental site trophoblastic tumor: a case report. Iran J Radiol 2016;13:e18480. 10.5812/iranjradiol.18480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng X, Wei Z, Zhang S, et al. A review on the pathogenesis and clinical management of placental site trophoblastic tumors. Front Oncol 2019;9:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas R, Cunha TM, Santos FB. Placental site trophoblastic tumor: a case report and review of the literature. J Radiol Case Rep 2015;9:14–22. 10.3941/jrcr.v9i4.2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee H-J, Shin W, Jang YJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of placental site trophoblastic tumor: experience of single institution in Korea. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2018;61:319–27. 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.3.319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Fisher RA, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi39–50. 10.1093/annonc/mdt345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouquet de la Jolinière J, Khomsi F, Fadhlaoui A, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Front Surg 2014;1:31. 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behnamfar F, Rouholamin S, Esteki M. Presentation of placental site trophoblastic tumor with amenorrhea. Adv Biomed Res 2017;6:29. 10.4103/2277-9175.201686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braga A, Mora P, de Melo AC, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia worldwide. World J Clin Oncol 2019;10:28–37. 10.5306/wjco.v10.i2.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luiza JW, Taylor SE, Gao FF, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor: immunohistochemistry algorithm key to diagnosis and review of literature. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep 2014;7:13–15. 10.1016/j.gynor.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng X, Liu X, Tian Q, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor: a case report and literature review. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2015;4:147–51. 10.5582/irdr.2015.01013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Nola R, Schönauer LM, Fiore MG, et al. Management of placental site trophoblastic tumor: two case reports. Medicine 2018;97:e13439. 10.1097/MD.0000000000013439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rey Valzacchi GM, Odetto D, Chacon CB, et al. Placental site trophoblastic disease. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2020;30:144–9. 10.1136/ijgc-2019-000952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Expert Panel on Women’s Imaging Panel, Dudiak KM, Maturen KE, et al. ACR appropriateness Criteria® gestational trophoblastic disease. J Am Coll Radiol 2019;16:S348–63. 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leite I, Cunha TM, Félix A. Postmolar gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. EURORAD 2013:case 10754. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lok C, van Trommel N, Massuger L, et al. Practical clinical guidelines of the EOTTD for treatment and referral of gestational trophoblastic disease. Eur J Cancer 2020;130:228–40. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Froeling FEM, Ramaswami R, Papanastasopoulos P, et al. Intensified therapies improve survival and identification of novel prognostic factors for placental-site and epithelioid trophoblastic tumours. Br J Cancer 2019;120:587–94. 10.1038/s41416-019-0402-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marques V, Cunha TM, trofoblasto Ddo. In: Ramos I, Ventura SR. Imagem em Oncologia Médica. Lidel Edições Técnicas, Lda 2018:296–307. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid P, Nagai Y, Agarwal R, et al. Prognostic markers and long-term outcome of placental-site trophoblastic tumours: a retrospective observational study. Lancet 2009;374:48–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60618-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang F, Zheng W, Liang Q, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of placental site trophoblastic tumor. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013;6:1448–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt KR, Coakley KJ. Mr appearance of placental site trophoblastic tumor: a report of three cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;170:485–7. 10.2214/ajr.170.2.9456970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Y, Lu H, Yu C, et al. Sonographic characteristics of placental site trophoblastic tumor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41:679–84. 10.1002/uog.12269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.FIGO Oncology Committee Figo staging for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia 2000. FIGO oncology Committee. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002;77:285–7. 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00063-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horowitz NS, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. Placental site trophoblastic tumors and epithelioid trophoblastic tumors: biology, natural history, and treatment modalities. Gynecol Oncol 2017;144:208–14. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marques V, Cunha TM, Coutinho S, et al. A placental site trophoblastic tumour.. EURORAD 2010:case 8427. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucas R, Cunha TM. Placental site trophoblastic tumour 3 years after a complete molar pregnancy with atypical localisation. J Obstet Gynaecol 2015;35:530–2. 10.3109/01443615.2014.968108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lan C, Li Y, He J, et al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor: lymphatic spread and possible target markers. Gynecol Oncol 2010;116:430–7. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]