Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

There is a growing population of childhood cancer survivors at risk for adverse outcomes, including sexual dysfunction.

AIM:

To estimate the prevalence of and risk factors for sexual dysfunction among adult female survivors of childhood cancer and evaluate associations between dysfunction and psychological symptoms/quality-of-life (QOL).

METHODS:

Female survivors (N=936, mean 7.8±5.6 years at diagnosis; 31±7.8 years at evaluation) and non-cancer controls (N=122) participating in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study completed clinical evaluations, Sexual Functioning Questionnaires (SFQ), and Medical Outcomes Survey Short Forms 36 (SF-36). Linear models compared SFQ scores between sexually active survivors (N=712) and controls; survivors with scores <10th percentile of controls were classified with sexual dysfunction. Logistic regression evaluated associations between survivor characteristics and sexual dysfunction, and between sexual dysfunction and QOL.

OUTCOMES:

Sexual dysfunction was defined by scores <10th percentile of non-cancer controls on the SFQ overall, as well as the domains of arousal, interest, orgasm and physical problems, while QOL was measured by scores on the SF-36 with both physical and mental summary scales.

RESULTS:

Sexual dysfunction was prevalent among 19.9% (95%CI 17.1,23.1) of survivors. Those diagnosed with germ cell tumors (OR=8.82, 95%CI 3.17,24.50), renal tumors (OR=4.49, 95%CI 1.89,10.67) or leukemia (OR=3.09, 95%CI 1.50,6.38) were at greater risk compared to controls. Age at follow-up (45–54 vs. 18–24 years; OR=5.72, 95% CI 1.87,17.49), pelvic surgery (OR=2.03, 95%CI 1.18,3.50), and depression (OR=1.96, 95% CI 1.10,3.51) were associated with sexual dysfunction. Hypogonadism receiving hormone replacement (vs. non-menopausal/non-hypogonadal; OR=3.31, 95%CI 1.53,7.15) represented an additional risk factor in the physical problems (e.g. vaginal pain and dryness) subscale. Survivors with, compared to those without sexual dysfunction, were more likely to score <40 on the physical (21.1% vs. 12.7%, p=0.01) and mental health (36.5% vs. 18.2%, p<0.01) summary scales of the SF-36. Only 2.9% of survivors with sexual dysfunction reported receiving intervention.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS:

Health care providers should be aware of the increased risk of sexual dysfunction in this growing population, inquire about symptomology, and refer for appropriate intervention.

STRENGTHS & LIMITATIONS:

Strengths of this study include the use of a validated tool for evaluating sexual function in a large population of clinically assessed female childhood cancer survivors. Limitations include potential for selection bias, and lack of clinically confirmed dysfunction.

CONCLUSION:

Sexual dysfunction is prevalent among female childhood cancer survivors and few survivors receive intervention; further research is needed to determine if those with sexual dysfunction would benefit from targeted interventions.

Keywords: childhood cancer, survivorship, sexual dysfunction, sexual function, psychosexual function

Introduction:

Ten-year survival rates of individuals with childhood cancer diagnoses now exceed 80%,1 resulting in an increasing population of adult survivors. Many survivors experience adverse health and psychosocial outcomes related to their cancer diagnosis and treatment,2,3 with over 95% experiencing at least one treatment-related chronic health condition by age 45 years4,5. Survivors have an increased prevalence of suboptimal outcomes across physical and psychosocial health domains. Previous studies suggest childhood cancer survivors are at risk for impaired sexual functioning6–10, postulated to result from disruption of normal psychosexual development during cancer treatment, and/or to long-term effects of cancer therapy6,8,11–15.

Although research indicates that female survivors have lower scores on measures of sexual function compared to females without a history of childhood cancer6,10, the burden of dysfunction in this population is not well understood and little is known about the availability of receipt of care for these impairments. Understanding disease- and treatment-related risk factors that may predispose female survivors to poor sexual function may improve targeted screening and/or development of tailored interventions for this population.

In this study of adult, female survivors of childhood cancer, we sought to: (i) estimate the prevalence of sexual dysfunction, and (ii) evaluate socio-demographic, medical, hormonal, health-related quality of life and psychological factors associated with sexual dysfunction.

Methods:

St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study

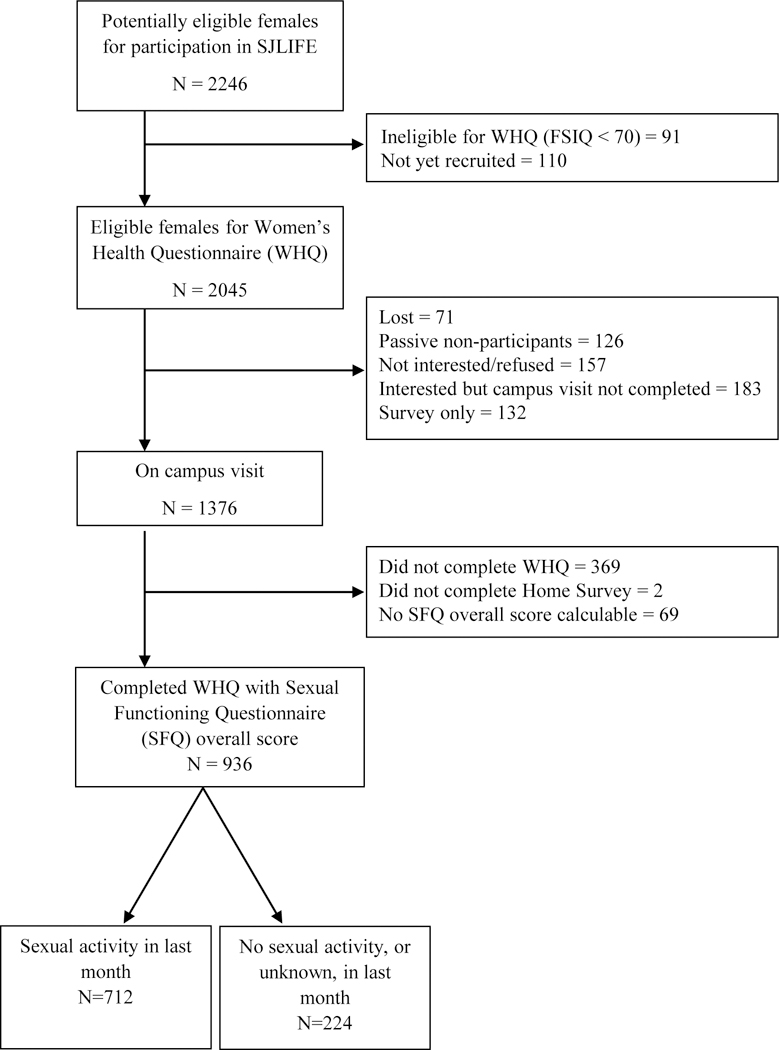

Participants were women enrolled in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE), who were previously treated for a childhood malignancy at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH), or members of a comparison group of community controls. The study was approved by the SJCRH Institutional Review Board (IRB ID SJLIFE) and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to initiation of any study activities, including questionnaires. Details about the SJLIFE study design, recruitment and participant characteristics have been previously described16–18. For this analysis, survivors were females at least 10 years from diagnosis, ≥18 years of age at time of survey completion, responded to health surveys that assessed quality of life and validated measures of psychosexual health, had an intelligence quotient (IQ) ≥70, and had completed a clinical assessment on the St. Jude campus (Figure 1). Community controls, recruited among friends and non-first-degree relatives of patients, were females without a history of childhood cancer, ≥18 years of age at time of survey, and completed a campus visit and surveys assessing quality of life and psychosexual health.

Figure 1:

Consort diagram of enrollment as of June 30, 2015.

Disease and Treatment Variables

Disease and treatment data, including diagnosis, cumulative dose of individual chemotherapeutic agents, surgical procedures, radiation site and dosage, were obtained from medical records by trained abstractors as previously described16. Pelvic surgery was defined as invasive surgical procedures involving pelvic structures undertaken at the time of and up to five years after cancer diagnosis.

Survey Measures

Survivor and control participants completed questionnaires assessing health history, social and demographic factors, and psychosocial functioning, including a women’s health questionnaire that specifically assessed reproductive and sexual health.

Sexual Health

Sexual health and functioning were assessed by the Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ), a gender-specific multi-item questionnaire, previously validated in sexually active cancer survivor cohorts and used in childhood cancer survivors8,19. The SFQ addresses activity, arousal, desire, interest, orgasm, masturbation, problems (including vaginal dryness, tightness, bleeding and pain, as well as increased skin sensitivity), relationships and satisfaction, and provides an overall score and individual sub-scale scores ranging from 0–5, except for the problems sub-scale, ranging from 0–6, with lower scores indicating poorer function. The SFQ does not include a cut-off score, and because estimates of sexual dysfunction prevalence are widely variable across studies,20–24 for this analysis sexual dysfunction was conservatively defined as a score falling below the 10th percentile score (overall and sub-scales) of the non-cancer controls. The masturbation sub-scale was excluded from this analysis due to a 10th percentile score of zero in controls.

Quality of Life and Psychosocial Outcomes

The Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 was used to assess health-related quality of life (QOL) and includes summary measures of physical and mental health. The SF-36 includes eight sub-scales: physical function, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, role emotional and mental health. This instrument has been used previously to characterize QOL in childhood cancer survivors25–27. Results are reported as sex-standardized t-scores with a population mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Those whose t-score was <40, after adjusting for age at assessment, were classified with poor QOL28. Psychological symptoms were measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18), an 18-item questionnaire with sub-scales assessing anxiety, depression and somatization29. Scores ≥63 after adjustment for age in each sub-scale were considered to represent psychological distress.

Body image was assessed using the Body Image Scale (BIS). Scores on the BIS range from 0–12, with higher scores representing more distress or dissatisfaction30,31. Relationship satisfaction was assessed with the Relationship Assessment Scale, composed of a 7-item Likert scale, items scored 1 through 5 on a continuous scale, where higher scores represent higher satisfaction32.

Hypogonadism and Hormonal Status

Presence or absence of hypogonadism was determined by history and laboratory studies, and included both premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), as well as hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (FSH/LH deficiency); normally timed menopause was considered separately. In women with amenorrhea prior to the age of 40, not on hormone replacement therapy or hormonal contraception, POI was defined by laboratory findings including follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) >30 IU/L and estradiol <17 pg/mL; hypogonadotropic hypogonadism was defined by an estradiol <17 pg/mL and FSH <11.2 IU/L33. In women receiving hormone therapy, the diagnosis was based on historical medical information. Women with amenorrhea that occurred after the age of 40, regardless of hormonal values, were assumed to be menopausal. Patients with hysterectomies were grouped with either non-hypogonadal/non-menopausal women, or with menopausal women depending on age, history and hormonal values. Patients with bilateral oophorectomies were defined as having POI if the surgery took place prior to the age of 40 and were otherwise classified as normally-timed menopause.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic variables. Comparisons between groups utilized chi-square statistics or t-tests as appropriate. Linear models, adjusting for age at assessment, were used to compare mean sexual functioning scores between survivors and controls. Associations between survivor characteristics and sexual dysfunctions, overall and for arousal, interest, orgasm and problems subscales, which most closely resembled diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Reference Manual, 5th Edition34, and for associations between sexual dysfunction and QOL were evaluated in separate multivariable logistic regression models. Results are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). Initial analyses included all 936 female survivors and are presented in the supplement. However, because the SFQ is validated only among individuals who are sexually active, data presented in the manuscript pertain to the 712 sexually active survivors. When available, missing data was completed with relevant data from the patient medical chart, otherwise left blank if patient report unavailable. Analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Significance was defined using a two-sided p-value of ≤ 0.05.

Results:

Data for this analysis were derived from 1376 survivors who completed a clinical assessment at SJCRH, of whom 936 (68%) completed the SFQ, and 122 community controls who completed both assessments (Figure 1). Participants (N=936) did not differ from eligible non-participants (N=1109) by age at diagnosis, primary diagnosis, pelvic tumors or treatment with chemotherapy or radiation. There were significant differences in race/ethnicity with participants less likely than non-participant survivors to be black and more likely to be Hispanic or other race/ethnicity (Supplemental Table 1). Of 936 participants, 224 did not report having any sexual activity, alone, or with a partner, in the four weeks prior to filling out the SFQ.

Compared with sexually active controls, sexually active survivors were younger at age of assessment, less likely to be married or living as married, less likely to have an annual household income ≥$20,000, have a college degree or higher, be non-Hispanic white, or live independently, and were more likely to have had more than one sexual partner in the last year (Table 1). Survivors were diagnosed with cancer at a mean age of 8.05 years (SD 5.58), and were most commonly diagnosed with leukemia, lymphoma, renal tumors, soft tissue tumors and central nervous system (CNS) tumors (Table 1). Among survivors, almost 85% received chemotherapy, 51.8% received radiation and 14.9% had undergone invasive pelvic surgery at or within five-years of cancer diagnosis (pelvic surgery may not be related to cancer-directed therapy). Of the 12.5% of survivors with a history of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or premature ovarian insufficiency, 39.3% were receiving hormone replacement (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sexually active participant sociodemographic characteristics

| Survivors | Controls | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=712) |

Survivors with sexual dysfunction (n=142) |

Survivors without sexual dysfunction (n=570) |

Total (n=122) |

|||||||

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | No. | Mean (95% CI) | No. | Mean (95% CI) | p | No. | Mean (95% CI) | p |

| Age at assessment, years | 31.21 (7.71) | (30.64,31.78) | 142 | 33.15 (31.72,34.58) | 570 | 30.72(30.12,31.33) | 0.002 | 122 | 35.79 (34.21,37.37) | <0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 8.05 (5.58) | (7.64,8.46) | 142 | 8.47 (7.57,9.37) | 570 | 7.95 (7.49,8.41) | 0.31 | -- | -- | |

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | P | No. | % | P | |

| Marital Status | 0.37 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Single, never married | 162 | 22.8 | 30 | 21.1 | 132 | 23.2 | 8 | 6.7 | ||

| Married or living as married | 481 | 67.6 | 102 | 71.8 | 379 | 66.5 | 102 | 85.7 | ||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 69 | 9.7 | 10 | 7.0 | 59 | 10.4 | 9 | 7.6 | ||

| Household income | 0.67 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| <$20,000 | 118 | 17.1 | 25 | 18.0 | 93 | 16.8 | 3 | 2.5 | ||

| ≥$20,000 | 511 | 73.8 | 99 | 71.2 | 412 | 74.5 | 113 | 93.4 | ||

| Do not know | 63 | 9.1 | 15 | 10.8 | 48 | 8.7 | 5 | 4.1 | ||

| Education | 0.005 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Less than college | 164 | 24.0 | 44 | 33.3 | 120 | 21.8 | 17 | 14.5 | ||

| College degree or higher | 519 | 76.0 | 88 | 66.7 | 431 | 78.2 | 100 | 85.5 | ||

| Ethnicity/race | 0.9 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| White | 566 | 79.5 | 116 | 81.7 | 450 | 79.0 | 104 | 85.3 | ||

| Black | 98 | 13.8 | 17 | 12.0 | 81 | 14.2 | 5 | 4.1 | ||

| Hispanic | 37 | 5.2 | 7 | 4.9 | 30 | 1.6 | 7 | 5.7 | ||

| Other | 11 | 1.5 | 2 | 1.4 | 9 | 5.3 | 6 | 4.9 | ||

| Independent Living | 0.86 | 0.009 | ||||||||

| Not living independently | 134 | 18.8 | 26 | 18.3 | 108 | 19.0 | 11 | 9.1 | ||

| Living independently | 578 | 81.2 | 116 | 81.7 | 462 | 81.1 | 110 | 90.9 | ||

| Age at first intercourse | <0.001 | 0.14 | ||||||||

| Never had intercourse | 16 | 2.3 | 10 | 7.1 | 6 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| <16 years of age | 130 | 18.3 | 25 | 17.7 | 105 | 18.5 | 28 | 23.0 | ||

| ≥16 years of age | 563 | 79.4 | 106 | 75.2 | 457 | 80.5 | 94 | 77.0 | ||

| Number of sexual partners in last year | <0.001 | 0.009 | ||||||||

| None | 29 | 4.1 | 17 | 12.1 | 12 | 2.1 | 6 | 5.0 | ||

| 1 sexual partner | 566 | 80.4 | 105 | 75.0 | 461 | 81.7 | 108 | 90.0 | ||

| > 1 sexual partner | 109 | 15.5 | 18 | 12.9 | 91 | 16.1 | 6 | 5.0 | ||

| Biologic Children | 0.20 | 0.10 | ||||||||

| None | 320 | 44.9 | 57 | 40.1 | 263 | 46.1 | 45 | 36.9 | ||

| At least one | 392 | 55.1 | 85 | 59.9 | 307 | 53.9 | 77 | 63.1 | ||

| Primary diagnosis | 0.01 | |||||||||

| Leukemia | 260 | 36.5 | 54 | 38.0 | 206 | 36.1 | ||||

| Lymphoma | 127 | 17.8 | 26 | 18.3 | 101 | 17.7 | ||||

| CNS tumor | 51 | 7.2 | 6 | 4.2 | 45 | 7.9 | ||||

| Soft tissue tumor | 57 | 8.0 | 9 | 6.3 | 48 | 8.4 | ||||

| Renal Tumor (Wilms) | 68 | 9.6 | 19 | 13.4 | 49 | 8.6 | ||||

| Osteosarcoma | 24 | 3.4 | 4 | 2.8 | 20 | 3.5 | ||||

| Ewing sarcoma family of tumors | 15 | 2.1 | 2 | 1.4 | 13 | 2.3 | ||||

| Retinoblastoma | 25 | 3.5 | 4 | 2.8 | 21 | 3.7 | ||||

| Germ cell tumor | 31 | 4.4 | 13 | 9.2 | 18 | 3.2 | ||||

| Neuroblastoma | 39 | 5.5 | 1 | 0.7 | 38 | 6.7 | ||||

| Other | 15 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.8 | 11 | 1.9 | ||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CNS, central nervous system.

Table 2.

Treatment characteristics of sexually active survivors, with and without sexual dysfunction

| Characteristic | Survivors, total | Survivors with sexual dysfunction | Survivors without sexual dysfunction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=712) | (n= 142) | (n= 570) | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | p | |

| Any chemotherapy | 0.45 | ||||||

| No | 110 | 15.5 | 19 | 13.4 | 91 | 16.0 | |

| Yes | 602 | 84.6 | 123 | 86.6 | 479 | 84.0 | |

| Any vincristine | 0.03 | ||||||

| No | 234 | 32.9 | 36 | 25.4 | 198 | 34.7 | |

| Yes | 478 | 67.1 | 106 | 74.7 | 372 | 65.3 | |

| Alkylators | 0.99 | ||||||

| None | 326 | 46.1 | 64 | 45.7 | 262 | 46.2 | |

| 0–8000 CED | 181 | 25.6 | 36 | 25.7 | 145 | 25.6 | |

| 8001–12000 CED | 121 | 17.1 | 25 | 17.9 | 96 | 16.9 | |

| ≥12000 CED | 79 | 11.2 | 15 | 10.7 | 64 | 11.3 | |

| Any radiation | 0.11 | ||||||

| None | 343 | 48.2 | 60 | 42.3 | 283 | 49.7 | |

| Yes | 369 | 51.8 | 82 | 57.8 | 287 | 50.4 | |

| Any cranial radiation | 0.29 | ||||||

| None | 550 | 77.3 | 105 | 73.9 | 445 | 78.1 | |

| Yes | 162 | 22.8 | 37 | 26.1 | 125 | 21.9 | |

| Any pelvic radiation | 0.10 | ||||||

| None | 585 | 82.2 | 110 | 77.5 | 475 | 83.3 | |

| Yes | 127 | 17.8 | 32 | 22.5 | 95 | 16.7 | |

| Any abdominal radiation | 0.73 | ||||||

| None | 564 | 79.2 | 111 | 78.2 | 453 | 79.5 | |

| Yes | 148 | 20.8 | 31 | 21.8 | 117 | 20.5 | |

| Any chest radiation | 0.74 | ||||||

| None | 549 | 77.1 | 111 | 78.2 | 438 | 76.8 | |

| Yes | 163 | 22.9 | 31 | 21.8 | 132 | 23.2 | |

| Pelvic tumor | 0.08 | ||||||

| No | 677 | 95.1 | 131 | 92.3 | 546 | 95.8 | |

| Yes | 35 | 4.9 | 11 | 7.8 | 24 | 4.2 | |

| Pelvic surgery | 0.009 | ||||||

| No | 606 | 85.1 | 111 | 78.17 | 495 | 86.8 | |

| Yes | 106 | 14.9 | 31 | 21.83 | 75 | 13.2 | |

| Oophorectomy (uni- or bilateral) | 0.03 | ||||||

| No | 625 | 89.3 | 116 | 84.1 | 509 | 90.6 | |

| Yes | 75 | 10.7 | 22 | 15.9 | 53 | 9.4 | |

| Hysterectomy | 0.28 | ||||||

| No | 645 | 91.0 | 125 | 88.7 | 520 | 91.6 | |

| Yes | 64 | 9.0 | 16 | 11.4 | 48 | 8.5 | |

| Mastectomy | 0.09 | ||||||

| No | 699 | 98.2 | 136 | 96.5 | 558 | 98.6 | |

| Yes | 13 | 1.8 | 5 | 3.6 | 8 | 1.4 | |

| Any limb amputation | 0.80 | ||||||

| No | 686 | 97.4 | 136 | 97.1 | 550 | 97.5 | |

| Yes | 18 | 2.6 | 4 | 2.9 | 14 | 2.5 | |

| Overall gonadal status | 0.09 | ||||||

| Non-menopausal/non-hypogonadal | 596 | 83.7 | 109 | 76.8 | 487 | 85.4 | |

| Hypogonadism with no hormone replacement | 54 | 7.6 | 15 | 10.6 | 39 | 6.8 | |

| Hypogonadism with hormone replacement | 35 | 4.9 | 11 | 7.8 | 24 | 4.2 | |

| Menopausal | 27 | 3.8 | 7 | 4.9 | 20 | 3.5 | |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; CED, cyclophosphamide equivalent dose; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Non-sexually active survivors

The 224 participant survivors with no reported sexual activity in the prior month were younger at diagnosis, less likely to have been married, have an annual household income ≥$20,000, live independently, have had a child, or to have ever had sexual intercourse (with 67.3% having no sexual partners over the last year) compared to survivors reporting sexual activity in the previous month (Supplemental Table 2). Non-sexually active survivors were more likely to have received radiation therapy, including cranial irradiation, and have hypogonadism without receiving hormone replacement, but did not differ significantly with respect to diagnosis, perceptions of sexual dysfunction, or presence of psychological symptoms (Supplemental Table 2). When analyses were performed with and without the 224 survivors who did not report sexual activity, results were essentially equivalent (Supplemental Table 3). Because the SFQ is validated only for persons who report sexual activity, the final analysis included only the 712 sexually active female survivors and 122 sexually active female controls.

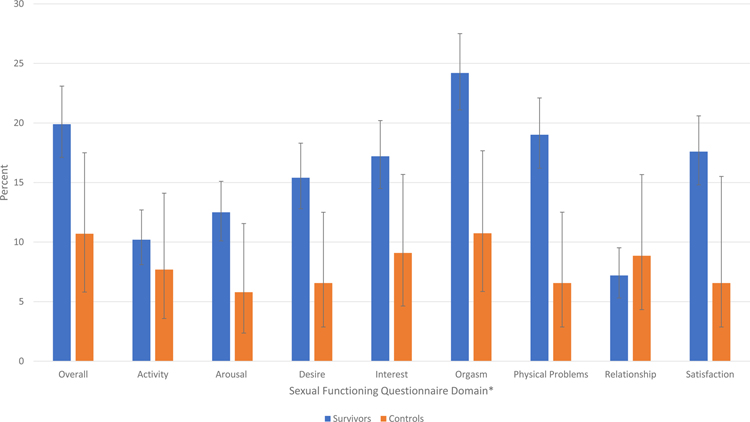

Sexual functioning of sexually active survivors

Survivors were more likely than controls to report overall sexual dysfunction (19.9%, 95% CI 17.1–23.1; vs. 10.7%, 95% CI 5.8–17.5). Survivors with primary diagnoses of germ cell tumors (OR 8.82, 95% CI 3.17–24.50), renal tumors (OR 4.49, 95% CI 1.89–10.67), and leukemia (OR 3.09, 95% CI 1.50–6.38), had the highest odds of reporting dysfunction as compared to controls after adjusting for age at assessment, race and education status (Supplemental Figure 1). Compared to controls, survivors’ mean scores on the SFQ were lower overall, and for the arousal desire, interest, orgasm, problems, relationship and satisfaction sub-scales (Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 3.

Sexual functioning questionnaire (SFQ) scores of sexually active survivors and controls, adjusted by age at assessment

| Survivors | Controls | Percent of survivors with sexual dysfunction | Percent of controls with sexual dysfunction | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFQ Scores | n | Mean | 95% CI | n | Mean | 95% CI | p | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | p |

| Overall | 712 | 3.19 | (3.13,3.23) | 122 | 3.47 | (3.35,3.60) | <0.01 | 142 | 19.9 | (17.1,23.1) | 13 | 10.7 | (5.80,17.50) | 0.015 |

| Activity | 704 | 2.65 | (2.55,2.74) | 117 | 2.87 | (2.63,3.10) | 0.10 | 72 | 10.2 | (8.10,12.7) | 9 | 7.69 | (3.58,14.10) | 0.39 |

| Arousal | 706 | 2.4 | (2.30,2.50) | 121 | 2.7 | (2.45,2.94) | 0.03 | 88 | 12.5 | (10.1,15.1) | 7 | 5.79 | (2.36,11.56) | 0.03 |

| Desire | 708 | 3.43 | (3.32,3.53) | 122 | 3.82 | (3.56,4.08) | 0.01 | 109 | 15.4 | (12.8,18.3) | 8 | 6.56 | (2.87,12.5) | <0.01 |

| Interest | 710 | 2.08 | (1.99,2.17) | 121 | 2.33 | (2.11,2.55) | 0.04 | 122 | 17.2 | (14.5,20.2) | 11 | 9.09 | (4.63,15.68) | 0.02 |

| Orgasm | 712 | 3.42 | (3.35,3.50) | 121 | 3.86 | (3.66,4.04) | <0.01 | 172 | 24.2 | (21.1,27.5) | 13 | 10.74 | (5.85,17.67) | <0.01 |

| Physical Problems | 710 | 4.28 | (4.23,4.34) | 122 | 4.52 | (4.39,4.65) | <0.01 | 135 | 19.0 | (16.2,22.1) | 8 | 6.6 | (2.87,12.51) | <0.01 |

| Relationship | 625 | 4.07 | (4.00,4.13) | 113 | 4.27 | (4.11,4.43) | 0.03 | 45 | 7.2 | (5.30,9.52) | 10 | 8.85 | (4.33,15.67) | 0.54 |

| Satisfaction | 712 | 3.7 | (3.62,3.78) | 122 | 4.21 | (4.01,4.41) | <0.01 | 125 | 17.6 | (14.8,20.6) | 8 | 6.56 | (2.87,15.51) | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: SFQ, Sexual functioning questionnaire; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2:

Percent of survivors and controls reporting sexual dysfunction across Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ) domains with 95% confidence intervals. *All p-values are <0.02, except for activity and relationship (Table 3).

There were no statistically significant differences between survivors with and without sexual dysfunction regarding marital status, household income, or race/ethnicity, though survivors with dysfunction were less likely to have ever had sexual intercourse or any sexual partners over the last year (Table 1). Moreover, when comparing survivors with and without sexual dysfunction, there were no statistically significant differences in exposures to any chemotherapy, including alkylating agents, or radiation therapy (Table 2). However, a greater proportion of those with dysfunction received an oophorectomy (unilateral or bilateral) than those without.

In a multivariable logistic regression model, survivors aged 35–44 years and ≥45 had increased odds of reporting sexual dysfunction compared to women 18–24 years at time of assessment, in the overall SFQ score as well as the interest and arousal sub-scores (Table 4). Higher educational attainment was associated with a lower odds of overall dysfunction, as well as, orgasm and arousal dysfunction. Survivors with depression had higher odds of sexual dysfunction both overall and in difficulties in the orgasm sub-scale. Survivors with hypogonadism had lower scores on the problems sub-scale than those with normal menstruation or menopause (Table 4). Common sexual problems reported during 75% or more of sexual encounters included lack of interest/desire (18.4% of survivors), inability to achieve orgasm (16.5%), and physical discomfort (e.g. vaginal dryness (15.7%) and vaginal tightness (18.0%) (Table 5)).

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of characteristics of sexually active survivors with sexual dysfunction

| Arousal | Interest | Orgasm | Physical Problems | Overall | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.01 | (0.96,1.06) | 0.65 | 1.01 | (0.97,1.05) | 0.79 | 1.00 | (0.96,1.04) | 0.98 | 1.00 | (0.96,1.04) | 0.81 | 0.99 | (0.95,1.03) | 0.45 |

| Age at follow-up, yrs v. 18–24 yrs | |||||||||||||||

| 25–34 | 1.93 | (0.86,4.34) | 0.11 | 1.52 | (0.75,3.07) | 0.24 | 1.23 | (0.71,2.14) | 0.46 | 0.85 | (0.47,1.53) | 0.58 | 1.29 | (0.67,2.48) | 0.44 |

| 35–44 | 1.47 | (0.56,3.87) | 0.44 | 1.68 | (0.75,3.74) | 0.21 | 1.58 | (0.83,3.01) | 0.17 | 0.87 | (0.43,1.77) | 0.70 | 1.68 | (0.80,3.55) | 0.17 |

| 45–54 | 8.35 | (2.22,31.37) | 0.002 | 4.15 | (1.29,13.37) | 0.02 | 1.91 | (0.66,5.57) | 0.23 | 0.74 | (0.24,2.30) | 0.60 | 5.72 | (1.87,17.49) | 0.002 |

| Marriage status v. single, never married | |||||||||||||||

| Married, living as married | 0.72 | (0.34,1.51) | 0.38 | 1.35 | (0.68,2.68) | 0.40 | 1.34 | (0.77,2.35) | 0.30 | 1.27 | (0.69,2.33) | 0.44 | 2.26 | (1.09,4.66) | 0.03 |

| Widowed/divorced | 0.43 | (0.14,1.37) | 0.15 | 0.63 | (0.22,1.80) | 0.39 | 0.64 | (0.29,1.42) | 0.27 | 0.69 | (0.30,1.64) | 0.40 | 1.15 | (0.45,2.96) | 0.77 |

| Education status v. less than college degree | |||||||||||||||

| College degree or higher | 0.35 | (0.20,0.60) | <0.001 | 0.62 | (0.38,1.00) | 0.05 | 0.59 | (0.39,0.89) | 0.01 | 0.81 | (0.51,1.29) | 0.38 | 0.56 | (0.35,0.89) | 0.01 |

| Number of sexual partners in last year v. no sexual partners | |||||||||||||||

| 1 sexual partner | 0.08 | (0.03,0.20) | <0.001 | 1.64 | (0.45,5.99) | 0.46 | 0.73 | (0.29,1.83) | 0.50 | 1.24 | (0.39,3.95) | 0.71 | 0.08 | (0.03,0.21) | <0.001 |

| >1 sexual partner | 0.06 | (0.02,0.17) | <0.001 | 0.92 | (0.22,3.81) | 0.90 | 0.94 | (0.35,2.50) | 0.90 | 1.79 | (0.54,5.93) | 0.34 | 0.09 | (0.03,0.24) | <0.001 |

| Cranial Irradiation v. none | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.72 | (0.82,3.64) | 0.15 | 1.45 | (0.78,2.67) | 0.24 | 1.52 | (0.88,2.62) | 0.13 | 0.90 | (0.51,1.59) | 0.71 | 1.32 | (0.73,2.39) | 0.36 |

| Abdominal/Pelvic Irradiation v. none | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.77 | (0.39,1.52) | 0.46 | 0.77 | (0.44,1.34) | 0.35 | 0.62 | (0.38,1.00) | 0.05 | 1.30 | (0.79,2.15) | 0.31 | 0.89 | (0.52,1.51) | 0.66 |

| Pelvic Surgery v. none | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.24 | (1.16,4.33) | 0.02 | 1.30 | (0.72,2.36) | 0.38 | 1.62 | (0.98,2.67) | 0.06 | 1.97 | (1.17,3.31) | 0.01 | 2.03 | (1.18,3.50) | 0.01 |

| Gonadal Status v. non-menopausal/hypogonadal | |||||||||||||||

| Hypogonadal without hormone replacement | 0.69 | (0.26,1.82) | 0.45 | 0.97 | (0.44,2.13) | 0.94 | 0.87 | (0.43,1.77) | 0.70 | 1.93 | (0.97,3.84) | 0.06 | 0.97 | (0.46,2.07) | 0.94 |

| Hypogonadal with hormone replacement | 2.44 | (0.92,6.42) | 0.07 | 1.79 | (0.75,4.25) | 0.19 | 1.95 | (0.91,4.21) | 0.09 | 3.31 | (1.53,7.15) | 0.002 | 1.74 | (0.76,4.00) | 0.19 |

| Menopausal | 0.41 | (0.10,1.73) | 0.22 | 0.64 | (0.19,2.18) | 0.47 | 0.71 | (0.22,2.30) | 0.57 | 1.22 | (0.35,4.17) | 0.76 | 0.47 | (0.14,1.54) | 0.21 |

| Presence of Depression (BSI-18) v. none | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.02 | (0.47,2.19) | 0.96 | 1.34 | (0.70,2.54) | 0.37 | 2.00 | (1.17,3.42) | 0.01 | 1.12 | (0.61,2.08) | 0.71 | 1.96 | (1.10,3.51) | 0.02 |

Table 5.

Percent of sexual problems experienced by sexually active survivors and controls

| Survivors | Controls | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | 25%–50% of the time | ≥ 75% of the time | Not at all | 25%–50% of the time | ≥ 75% of the time | ||||||||||

| Total | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | Total | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | p | |

| Anxiety about performance | 702 | 505 | 71.9 | 156 | 22.2 | 41 | 5.8 | 122 | 100 | 82.0 | 21 | 17.2 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.02 |

| Lack of sexual desire/interest | 705 | 282 | 40.0 | 293 | 41.6 | 130 | 18.4 | 122 | 39 | 32.0 | 67 | 54.9 | 16 | 13.1 | 0.02 |

| Vaginal tightness | 693 | 367 | 53.0 | 201 | 29.0 | 125 | 18.0 | 120 | 83 | 69.2 | 30 | 25.0 | 7 | 5.8 | <0.01 |

| Vaginal bleeding or irritation from penetration or intercourse | 699 | 557 | 79.7 | 119 | 17.0 | 23 | 3.3 | 120 | 98 | 81.7 | 19 | 15.8 | 3 | 2.5 | 0.84 |

| Sharp pain inside or outside your vagina | 702 | 558 | 79.5 | 110 | 15.7 | 34 | 4.8 | 121 | 110 | 90.9 | 7 | 5.8 | 4 | 3.3 | <0.01 |

| Vaginal dryness during sexual activity | 707 | 270 | 38.2 | 326 | 46.1 | 111 | 15.7 | 122 | 56 | 45.9 | 57 | 46.7 | 9 | 7.4 | 0.04 |

| Pain during penetration or intercourse | 708 | 384 | 54.2 | 258 | 36.4 | 66 | 9.3 | 122 | 83 | 68.0 | 30 | 24.6 | 9 | 7.4 | 0.02 |

| Unable to orgasm | 697 | 316 | 45.3 | 266 | 38.2 | 115 | 16.5 | 122 | 74 | 60.7 | 42 | 34.4 | 6 | 4.9 | <0.01 |

| Increased skin sensitivity to intimate touching | 694 | 514 | 74.1 | 132 | 19.0 | 48 | 6.9 | 121 | 86 | 71.1 | 27 | 22.3 | 8 | 6.6 | 0.70 |

| Other problem with sexuality | 627 | 594 | 94.7 | 21 | 3.4 | 12 | 1.9 | 109 | 103 | 94.5 | 4 | 3.7 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.98 |

Psychological factors of sexually active survivors

Among survivors with sexual dysfunction, 41% reported a perception that they were at greater risk for this impairment compared to other women their age without a history of childhood cancer (Table 6). Despite this perceived risk, only 2.9% of survivors with poor function reported receiving an intervention (medical, psychological or alternative/complementary therapy) addressing sexual function. Sexual dysfunction was also associated with increased symptoms of depression, anxiety and somatization as well as greater distress with body image and lower relationship satisfaction (Table 6).

Table 6.

Psychological and pubertal variables of sexually active survivors with and without sexual dysfunction

| Survivors, total | Survivors with sexual dysfunction | Survivors without sexual dysfunction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n= 712) | (n= 142) | (n= 570) | |||||

| Characteristic | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | p |

| Puberty Status | 0.21 | ||||||

| Early | 130 | 18.4 | 29 | 20.9 | 101 | 17.8 | |

| Normal | 471 | 66.6 | 84 | 60.4 | 387 | 68.1 | |

| Late | 106 | 15.0 | 26 | 18.7 | 80 | 14.1 | |

| Depression | <0.01 | ||||||

| No | 623 | 88.6 | 100 | 70.9 | 468 | 83.3 | |

| Yes | 80 | 11.4 | 41 | 29.1 | 94 | 16.7 | |

| Anxiety | 0.02 | ||||||

| No | 622 | 88.6 | 117 | 83.0 | 505 | 90.0 | |

| Yes | 80 | 11.4 | 24 | 17.0 | 56 | 10.0 | |

| Somaticizing | <0.01 | ||||||

| No | 568 | 80.8 | 113 | 80.1 | 510 | 90.8 | |

| Yes | 135 | 19.2 | 28 | 19.9 | 52 | 9.3 | |

| History of intervention for sexual dysfunction | 0.15 | ||||||

| No | 688 | 98.4 | 132 | 97.1 | 556 | 98.8 | |

| Yes | 11 | 1.6 | 4 | 2.9 | 7 | 1.2 | |

| Perception of sexual dysfunction (compared to peers) | <0.01 | ||||||

| Less | 117 | 16.8 | 20 | 14.3 | 97 | 17.5 | |

| same | 400 | 57.5 | 63 | 45.0 | 337 | 60.6 | |

| more | 179 | 25.7 | 57 | 40.7 | 122 | 21.9 | |

| Perceptions of infertility (compared to peers) | 0.83 | ||||||

| less | 103 | 14.7 | 22 | 15.6 | 81 | 14.5 | |

| same | 229 | 32.7 | 48 | 34.0 | 181 | 32.3 | |

| more | 369 | 52.6 | 71 | 50.4 | 298 | 53.2 | |

| Overall body image | 709 | 6.6 | 142 | 8.7 | 567 | 6.1 | <0.01 |

| Relationship Satisfaction | 606 | 30.0 | 111 | 26.8 | 495 | 30.8 | <0.01 |

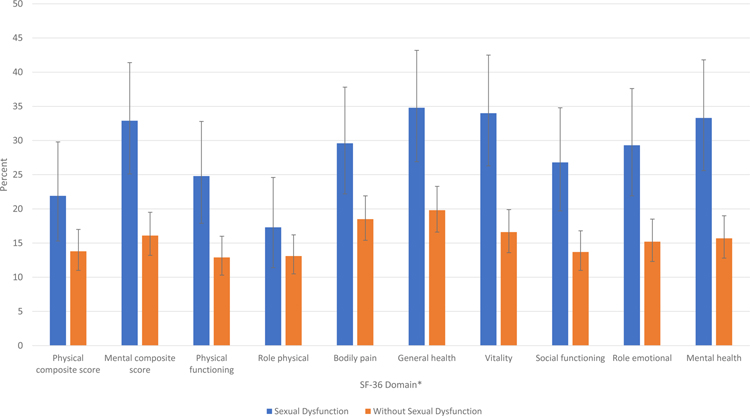

Quality of Life of sexually active survivors

Compared to survivors without sexual dysfunction, a greater proportion of survivors with dysfunction reported poor health-related quality of life on measures of both composite scores for mental (32.9% vs. 16.1%) and physical health (21.9% vs. 13.8%), and sub-scales for physical functioning (24.8% vs. 12.9%), bodily pain (29.6% vs. 18.5%), general health (34.8% vs. 19.8%), vitality (34.0% vs. 16.6%), social functioning (26.8% vs. 13.7%), role emotional (29.3% vs. 15.2%) and mental health domains (33.3% vs. 15.7%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Percent of sexually active survivors with poor health-related quality of life (score ≤40) on domains of the SF-36 stratified by sexual dysfunction status, with 95% confidence intervals. *All p-values are <0.02, except for role physical (supplemental Table 4).

Discussion:

In a large and well-characterized cohort of adult female survivors of childhood cancer with comprehensive treatment, detailed medical history, and clinical and laboratory evaluations, we found the prevalence of self-reported sexual dysfunction to be nearly two-fold higher than that reported by community controls (19.9% vs. 10.7%). Among sexually active survivors, sexual dysfunction was observed overall, and in nearly every sub-scale of the SFQ, including activity, orgasm, problems, relationship, interest, and desire. A substantial proportion of survivors (19.0%) reported dysfunction on the physical problems subscale during sexual activity compared to controls (6.6%) (Table 3). The problems most commonly reported were lack of desire, vaginal tightness, inability to orgasm and vaginal dryness (Table 5). Risk of overall dysfunction was associated with older age at assessment, marital status, depression, and cancer therapy exposures, including pelvic surgeries proximal to cancer diagnosis, as well as laboratory validated hypogonadism, a downstream effect of radiation and alkylating agent exposure33. Additionally, sexual dysfunction was associated with psychological distress, underscoring the potential for concurrent emotional and sexual dysfunction in this population.

Unlike our study, a previous analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) did not consistently find an association between marriage and sexual dysfunction.8 The reason for the discordance in these results from two large populations of childhood cancer survivors is not clear. However, in the SJLIFE analysis there is a higher proportion of women who reported being married, or living as married, than in the CCSS analysis (67.6% vs. 39.5%, respectively). Other populations have shown an association between being in a relationship or marriage and higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction, including in adult women diagnosed with gynecologic cancer.35 Similarly, among a general population of women transitioning to menopause, those who were married had lower sexual function scores.36 Spousal or partner expectations and/or relationship dynamics affects an individual’s sexual function and contributes to these differences.

In assessing differences between diagnostic groups, germ cell tumors, renal tumors and leukemia all demonstrated an increased risk of sexual dysfunction (Supplemental Figure 1). Females with germ cell tumors typically require pelvic surgery and oophorectomy. However, the increased risk of sexual dysfunction among survivors of leukemia and renal tumors was unexpected. While this may be attributable to both psychologic and physiologic factors, in our univariate analysis of treatment characteristics, a greater proportion of survivors with sexual dysfunction received therapy with vincristine than those without dysfunction (Table 2). Treatment for both acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and Wilms tumor, includes vincristine, a vinca-alkaloid known to increase risk for peripheral and sensory neuropathy.37 Additional research in larger cohorts is needed to elucidate factors underpinning the higher risk for sexual dysfunction, observed in specific diagnostic groups.

While 40% of our study population perceived that they were at higher risk of sexual dysfunction compared to their peers, less than 3% reported receiving interventions, including psychological, medical or an alternative therapy despite existing treatment guidelines38,39. Our study did not specifically assess if female cancer survivors had discussions surrounding sexual functioning with a health care provider, but results suggest that lack of intervention in this population may relate to a deficiency in identifying sexual dysfunction among survivors. While previous reports have shown that childhood cancer survivors have demonstrated problems with sexual development and functioning during their adolescent and young adult years,11,13,40,41 our data supports that this burden of dysfunction persists well into adulthood, as our cohort includes patients over 18, at least 10 years from diagnosis and the mean age of the women in our cohort was in their 30s.

The literature also highlights deficiencies and gaps between adolescent and young adult cancer patients and their oncologists in communicating about sexual health42. While patients desire these conversations, many oncologists feel they lack appropriate training to tackle these discussions or do not feel comfortable engaging in these topics43. Furthermore, conversations regarding sexual health may focus on fertility issues rather than being inclusive of all aspects of sexual health, including sexual function42,43. While pediatric clinicians share responsibility for discussing sexual health and function with their patients at diagnosis, during therapy and into survivorship (when developmentally appropriate), the persistence of sexual dysfunction into adulthood demonstrates the need for awareness of this high risk population by adult providers, and sexual medicine professionals who may be called upon in ameliorating the burden of symptoms in this population. Childhood cancer survivors experience the bulk of their sexual life outside the ages cared for by their pediatric and oncology practitioners, so early identification of deficiencies in sexual function prompting referral to sexual medicine providers will increase the likelihood of appropriate intervention.

Providing intervention is important, as our study shows an association between survivors with sexual dysfunction experience poorer QOL in both physical and mental health domains, symptoms of emotional distress, concerns with body image, and relationship dissatisfaction. Prior studies have also shown an association between sexual dysfunction and psychosocial/health-related QOL measures in both survivor and non-cancer populations6,41,44. In a cohort of 599 survivors assessing the association between sexual functioning and health-related QOL, female survivors showed a significant association between sexual dysfunction and poorer scores on multiple sub-scales of the SF-36, including bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional status, role physical, and overall mental health and physical functioning41. It is unclear whether poor function or psychosocial symptoms manifest first, but there likely is a complex reciprocal association as emotional symptoms may contribute to, or be the result of, sexual dysfunction44. As other reports in the literature do not consistently show an association between sexual function and mental health or quality of life measures,40,45 further investigation of this relationship among female survivors of childhood cancer is warranted.

Furthermore, while there are established interventions for sexual dysfunctions, including pelvic floor therapy, and mindfulness techniques, with emerging pharmacologic therapies, such as flibanserin, which may be offered for certain dysfunctions, including decreased sexual desire,46 it remains unclear whether female childhood cancer survivors will respond similarly to these interventions as their peers without cancer. Providers who care for childhood cancer survivors should inquire about sexual problems and be positioned to facilitate referral to appropriate sexual-health providers, and these providers, including psychologists, sexual therapists, gynecologists and/or pelvic floor therapists should be aware of this growing population of at-risk women38,47.

Strengths of this research include large sample size, and inclusion of detailed information from prospective medical assessments, as well as patient reported data. However, larger studies are necessary to investigate treatment and psychosocial factors that may be associated with dysfunctions among specific diagnostic categories, as the heterogeneity of diagnosis, treatment exposures, and dysfunction may have limited the power to detect an effect. We were also limited by patient self-report of dysfunction and were unable to document the actual presence or absence of a disorder. Future studies may benefit by correlating SFQ scores to diagnosis of sexual dysfunction via structured interviews by professionals experienced in diagnosing and treating these disorders and testing interventions for sexual dysfunction established in the non-cancer population among cancer survivors. As an important caveat to consider in interpreting the results of this study, the sexually active survivors differed from controls in age at assessment, marital status and annual household income. While these differences have been reported in other studies comparing childhood cancer survivors to a non-cancer population,8,15 they may represent a source of bias. In addition, this analysis likely underreported sexual problems. Discussing one’s sexual experiences is a sensitive topic. Adolescent and young adult cancer survivors have reported discomfort in initiating conversations surrounding sexual health (42,48) and those with sexual dysfunction may be less likely to complete a survey reporting on this topic.

Conclusions:

Sexual dysfunction is prevalent among female survivors of childhood cancer. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction in this population include pelvic surgery occurring proximal to cancer diagnosis, as well as hormonal deficiencies. Although survivors with sexual dysfunction perceive that they are at risk for sexual dysfunction, few reported receiving intervention. Screening for, and interventions to further identify and treat sexual dysfunction among survivors are needed. Addressing this important problem has potential to improve mental health and enhance overall quality of life. Providers who care for childhood cancer survivors should inquire regularly about sexual functioning and refer to sexual health specialists when indicated. Continued research is necessary to identify risk factors among survivors that characterize high-risk subgroups, as well as, targeted screening and intervention strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Relative odds of sexual dysfunction by diagnostic group, compared to community controls, adjusted for age at assessment.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Grant Support: St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Cancer Center Support Grant No. 5P30CA021765–33, the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study Grant No. U01 CA195547, and American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This study has been presented in part at: ASCO Survivorship Symposium 2018

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotta A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). : SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR), 1975–2013. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. : The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Brinkman TM, Zhu L, Zeltzer LK, et al. : Longitudinal patterns of psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer 109:1373–81, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, et al. : Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 32:1218–27, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. : Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. Jama 309:2371–81, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bober SL, Zhou ES, Chen B, et al. : Sexual function in childhood cancer survivors: a report from Project REACH. J Sex Med 10:2084–93, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frederick NN, Recklitis CJ, Blackmon JE, et al. : Sexual Dysfunction in Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ford JS, Kawashima T, Whitton J, et al. : Psychosexual functioning among adult female survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 32:3126–36, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon JY, Park HJ, Ju HY, et al. : Gonadal and Sexual Dysfunction in Childhood Cancer Survivors. Cancer Res Treat, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Barrera M, Teall T, Barr R, et al. : Sexual function in adolescent and young adult survivors of lower extremity bone tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 55:1370–6, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dijk EM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Kaspers GJ, et al. : Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology 17:506–11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puukko LR, Hirvonen E, Aalberg V, et al. : Sexuality of young women surviving leukaemia. Arch Dis Child 76:197–202, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF: The course of life of survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology 14:227–38, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haavisto A, Henriksson M, Heikkinen R, et al. : Sexual function in male long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 122:2268–76, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundberg KK, Lampic C, Arvidson J, et al. : Sexual function and experience among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer 47:397–403, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Nolan VG, et al. : Prospective medical assessment of adults surviving childhood cancer: study design, cohort characteristics, and feasibility of the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56:825–36, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ojha RP, Oancea SC, Ness KK, et al. : Assessment of potential bias from non-participation in a dynamic clinical cohort of long-term childhood cancer survivors: results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60:856–64, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudson MM, Ehrhardt MJ, Bhakta N, et al. : Approach for Classification and Severity Grading of Long-term and Late-Onset Health Events among Childhood Cancer Survivors in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26:666–674, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syrjala KL, Schroeder TC, Abrams JR, et al. : Sexual Function Measurement and Outcomes in Cancer Survivors and Matched Controls. The Journal of Sex Research 37:213–225, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anastasiadis AG, Davis AR, Ghafar MA, et al. : The epidemiology and definition of female sexual disorders. World J Urol 20:74–8, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC: Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. Jama 281:537–44, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons JS, Carey MP: Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions: results from a decade of research. Arch Sex Behav 30:177–219, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nappi RE, Cucinella L, Martella S, et al. : Female sexual dysfunction (FSD): Prevalence and impact on quality of life (QoL). Maturitas 94:87–91, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worsley R, Bell RJ, Gartoulla P, et al. : Prevalence and Predictors of Low Sexual Desire, Sexually Related Personal Distress, and Hypoactive Sexual Desire Dysfunction in a Community-Based Sample of Midlife Women. J Sex Med 14:675–686, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reulen RC, Zeegers MP, Jenkinson C, et al. : The use of the SF-36 questionnaire in adult survivors of childhood cancer: evaluation of data quality, score reliability, and scaling assumptions. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:77, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reulen RC, Winter DL, Lancashire ER, et al. : Health-status of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a large-scale population-based study from the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Int J Cancer 121:633–40, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rueegg CS, Gianinazzi ME, Rischewski J, et al. : Health-related quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer: the role of chronic health problems. J Cancer Surviv 7:511–22, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–83, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derogatis L: Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN, USA, NCS Pearson, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vuotto SC, Ojha RP, Li C, et al. : The role of body image dissatisfaction in the association between treatment-related scarring or disfigurement and psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, et al. : A body image scale for use with cancer patients. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 37:189–97, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendrick SS: A Generic Measure Of Relationship Satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family 50:93–98, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Krasin MJ, et al. : Premature Ovarian Insufficiency in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:2242–2250, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (ed 5th). Washington, DC, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guntupalli SR, Sheeder J, Ioffe Y, et al. : Sexual and Marital Dysfunction in Women With Gynecologic Cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 27:603–607, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith RL, Gallicchio L, Flaws JA: Factors Affecting Sexual Function in Midlife Women: Results from the Midlife Women’s Health Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 26:923–932, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Velde ME, Kaspers GL, Abbink FCH, et al. : Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in children with cancer: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 114:114–130, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, et al. : Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology 36:492–511, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melisko ME, Narus JB: Sexual Function in Cancer Survivors: Updates to the NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 14:685–9, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wettergren L, Kent EE, Mitchell SA, et al. : Cancer negatively impacts on sexual function in adolescents and young adults: The AYA HOPE study. Psychooncology 26:1632–1639, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, et al. : Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology 19:814–22, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frederick NN, Revette A, Michaud A, et al. : A qualitative study of sexual and reproductive health communication with adolescent and young adult oncology patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66:e27673, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frederick NN, Campbell K, Kenney LB, et al. : Barriers and facilitators to sexual and reproductive health communication between pediatric oncology clinicians and adolescent and young adult patients: The clinician perspective. Pediatr Blood Cancer:e27087, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Flynn KE, Lin L, Bruner DW, et al. : Sexual Satisfaction and the Importance of Sexual Health to Quality of Life Throughout the Life Course of U.S. Adults. J Sex Med 13:1642–1650, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lehmann V, Hagedoorn M, Gerhardt CA, et al. : Body issues, sexual satisfaction, and relationship status satisfaction in long-term childhood cancer survivors and healthy controls. Psychooncology 25:210–6, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Z, Yang D, Yu L, et al. : Efficacy and Safety of Flibanserin in Women with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sex Med 12:2095–104, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barbera L, Zwaal C, Elterman D, et al. : Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr Oncol 24:192–200, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albers LF, Haj Mohammad SF, Husson O, et al. : Exploring Communication About Intimacy and Sexuality: What Are the Preferences of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer and Their Health Care Professionals? J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Relative odds of sexual dysfunction by diagnostic group, compared to community controls, adjusted for age at assessment.