Abstract

We report a case of a DICER1-associated EWSR1-rearranged malignant primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) arising in a patient with DICER1 tumor predisposition syndrome. A 16-yr-old female with a history of multinodular goiter presented with a widely metastatic abdominal small round blue cell tumor with neuroectodermal differentiation. EWSR1 gene rearrangement was identified in the tumor by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Genetic analysis revealed biallelic pathogenic DICER1 variation. The patient was treated with an aggressive course of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation with complete pathologic response. We believe this case to represent a new expression of the DICER1 tumor predisposition syndrome, an entity caused by deleterious germline mutations in the DICER1 gene, encoding a ribonuclease active in the processing of miRNA. Patients with germline mutations in DICER1 develop a diverse group of benign and malignant tumors. Some of these tumors have been noted to have immature neuroepithelium as a component, including the ciliary body medulloepithelioma and the recently described DICER1-associated presacral malignant teratoid neoplasm. To our knowledge, abdominal sarcomas that resemble PNET histology with an EWSR1 rearrangement have not previously been described as a classical expression of the DICER1 syndrome phenotype.

Keywords: Ewing's sarcoma, multinodular goiter, neoplasm of the genitourinary tract

INTRODUCTION

DICER1 syndrome is an autosomal dominant hereditary tumor predisposition syndrome caused by deleterious germline mutations of the DICER1 gene (Warren et al. 2020). The DICER1 gene is located on Chromosome 14 and encodes a RNase III endoribonuclease that processes precursor micro RNAs (miRNAs) into functional mature miRNAs, which serve to negatively regulate gene expression by messenger RNA (mRNA) silencing or repressing translation (Foulkes et al. 2014; Wormald et al. 2018). The predicted effects of mutations in DICER1 include reduction of DICER1 protein level, consequently reduction of miRNA levels, and thereby reduction in tumor-suppression activity. DICER1 function in cancer, however, may vary, as its inactivation has been associated with tumorigenesis in some tumor types, whereas increased DICER1 protein expression has been associated with invasion and metastasis in others (Kumar et al. 2007; Hata and Kashima 2016). The expression of DICER1 can be increased or decreased in various types of cancers, leading to expression changes in the large number of cellular miRNAs. Instances of global down-regulation of miRNAs in tumors have been reported, especially in poorly differentiated ones, and one explanation proposed is that the function of miRNAs is to define lineage-specific properties so that a low abundance of miRNAs could promote the undifferentiated state of tumor cells (Lu et al. 2005; Hata and Kashima 2016). On the other hand, elevated levels of DICER1 have been found in tumor cells, even if global up-regulation of miRNA is uncommon (Hata and Kashima 2016).

DICER1-associated tumors appear to arise as a result of the second hit hypothesis, whereby, in addition to a heterozygous germline mutation, typically a truncating loss of function mutation, a second, tumor-specific missense mutation occurs (Schultz 2018; Wormald et al. 2018). These somatic missense mutations predominantly occur within exons 24 and 25 in the RNaseIIIb domain at one of five hotspot codons, E105, D1709, G1809, D1810, or E1813 (Pugh et al. 2014).

Initially described in familial pleuropulmonary blastoma (Hill et al. 2009; Slade et al. 2011), in which 70% of cases harbor a germline heterozygous DICER1 loss-of-function mutation, DICER1 syndrome has since been associated with a variety of additional benign and malignant conditions including lung cysts, cystic nephroma (Bahubeshi et al. 2010; Faure et al. 2016), Wilms tumor (Foulkes et al. 2014), multinodular goiter (Rio Frio et al. 2011; Schultz 2018), thyroid adenoma, juvenile-type intestinal polyps, ciliary body medulloepithelioma, nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma, pituitary blastoma, pinealoblastoma (Schultz 2018), cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (Doros et al. 2012), Sertoli–Leydig tumors (Fremerey et al. 2017), and malignant sacrococcygeal tumors (Nakano et al. 2019; Warren et al. 2020). DICER1 syndrome exhibits incomplete penetrance, and up to 95% of DICER1 carriers do not develop any significant clinical features by the age of 10 (Doros et al. 1993; Wormald et al. 2018; de Kock et al. 2019; Stewart et al. 2019).

Although embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas and renal sarcomas are recognized in association with DICER1 syndrome, and recent reports have identified a small cohort of patients with intracranial sarcomas, other sarcoma types are not known to occur in these patients. Here, we report the unique case of a teenage girl who presented with a large abdominopelvic malignancy that was identified as a DICER1-associated, EWSR1-rearranged primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET), and thereby adds to the spectrum of malignant tumors that occur in patients with this cancer predisposition syndrome.

RESULTS

Clinical Presentation

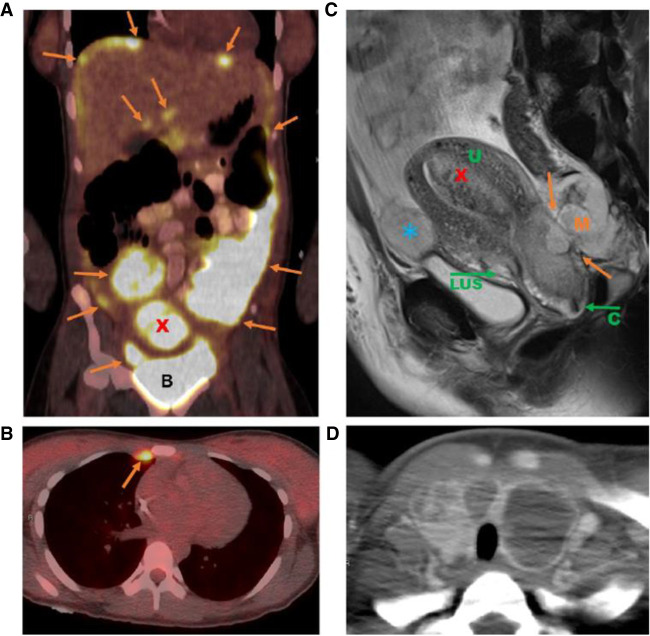

A 16-yr-old female presented with chest pain and several months of worsening abdominal distention. Her past medical history was notable for iron deficiency anemia and multinodular goiter with a prior biopsy demonstrating a benign adenomatoid nodule. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed multiple abdominal and pelvic masses with an enlarged uterus, omental caking, and ascites (Fig. 1). Both ovaries were normal and uninvolved by tumor. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT confirmed the presence of large FDG-avid masses within the pelvis and abdomen with uterine involvement (including both intrauterine mass and invasion of lower uterine segment), and FDG-avid bilateral mammary chain lymph nodes. FDG-avid thyroid enlargement, consistent with multinodular goiter, was also noted (Fig. 1). Serologic studies revealed a mildly elevated CA-125 (77U/mL), normal AFP, and normal CEA.

Figure 1.

Imaging findings at diagnosis. (A) Abdominal fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) scan image demonstrating diffuse hypermetabolic omental, peritoneal, and perihepatic tumor implants (orange arrows) as well as hypermetabolic intrauterine mass (red X). (B) Bladder. (B) Chest FDG-PET scan image demonstrating hypermetabolic internal mammary chain node (orange arrow). (C) Sagittal pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) image demonstrating pelvic mass invading cervix and lower uterine segment (orange arrows), intrauterine mass (red X), and peritoneal implant anterior to uterus (blue *). (U) Uterus, (LUS) lower uterine segment, (C) cervix, (M) mass. (D) Axial CT image showing thyroid gland with multifocal cystic lesions consistent with multinodular goiter.

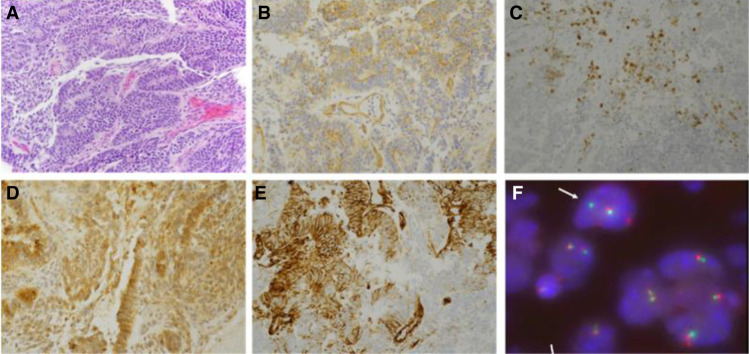

Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed with biopsy of peritoneal and omental implants. Histologic examination showed a high-grade undifferentiated malignancy consisting of primitive or blastemal-like small blue cells with scattered pseudo-rosette formation and gland-like structures. The tumor cells were variably round to spindled with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. Densely cellular areas alternated with less cellular areas with intervening loose fibroblastic stroma. The intervening fibroblastic stroma was negative for desmin. Chondroid foci and foci of rhabdomyosarcoma were absent. There was no evidence of teratoma. Areas of desmin positivity were noted, however, some of these foci also stained with calretinen, raising the possibility of entrapped mesothelium. Immunohistochemistry showed focal positive staining for NKX2.2, synaptophysin, and PAX8; dot-like positive staining for CD99 with areas of faint incomplete membranous staining; and positive WT-1 (Table 1; Fig. 2A–E). The staining patterns were not that of a classic Ewing sarcoma, which shows diffuse membranous staining for CD99. To further characterize the tumor, additional immunohistochemical stains were performed and were notable for negative cytokeratins (AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, CK7, CK20) and intact INI-1. Additional negative stains included thyroid markers (thyroglobulin, TTF-1), inhibin, α-feto protein (AFP), chromogranin, GFAP, SF-1, S-100, and OCT3/4. Yolk sac tumor was considered given glypican-3 positivity but thought to be unlikely given the minimal cytokeratin staining and negative AFP (Euscher 2019). In addition, positive glypican-3 staining can be seen in immature neural elements (Zynger et al. 2008). Taken together, the morphology and immunohistochemical profile of this difficult-to-classify tumor was felt to be most compatible with tumors within the primitive round-cell sarcoma family, including Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (Desai and Jambhekar 2010).

Table 1.

Diagnostic immunohistochemical stains

| Marker | Staining pattern |

|---|---|

| AE1/AE3 | Rare positive cells |

| AFP | Negative |

| BCL-2 | Patchy, weak positivity |

| β-catenin | Diffuse cytoplasmic and focal nuclear positivity |

| BRG-1 | Intact |

| Calretinin | Negative (highlights entrapped mesothelial cells) |

| CAM5.2 | Rare positive cells |

| CD99 | Focal weak cytoplasmic and rare membranous positivity |

| Chromogranin | Negative |

| CK7, CK20 | Negative |

| Desmin | Rare positive cells |

| ER | Negative |

| GFAP | Negative |

| Glypican-3 | Positive |

| Inhibin | Patchy positivity |

| INI-1 | Intact |

| NKX2.2 | Focal positivity |

| OCT3/4 | Negative |

| PAX-8 | Focal positivity |

| S-100 | Rare positive cells |

| SF-1 | Negative |

| Thyroglobulin, TTF-1 | Negative |

Figure 2.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections demonstrating a proliferation of small round blue cells with immature neuroepithelial components, areas of pseudo-rosette formation, and gland-like structures in a background of loose fibroblastic stroma with scattered spindle cells. H&E, 20×. (B) CD99 immunostain with dot-like positivity and faint cytoplasmic staining. Note lack of diffuse complete membranous staining typical of Ewing sarcoma, 40×. (C) NKX2.2 stain with rare positive cells, 20×. (D) Glypican-3 highlighting the neuroepithelial elements, 40× (Desai and Jambhekar 2010). (E) WT1 immunostain with cytoplasmic staining and absence of nuclear staining, 40×. (F) EWSR1 fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) break-apart probe demonstrating split signal (arrow) indicating gene rearrangement in a subset of cells.

The patient's worsening clinical status, with increasing ascites and lower extremity edema secondary to venous compression by pelvic masses, prompted initiation of chemotherapy. Ewing sarcoma/PNET type chemotherapy was chosen, using the schema of the Children's Oncology Group (COG) protocol AEWS0031 Regimen B1 (interval compression) consisting of cycles of vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (VDC) alternating with cycles of ifosfamide and etoposide (IE), administered every 2 wk (Womer et al. 2012), with the addition of a second weekly vincristine dose in VDC cycles, similar to that given in COG AEWS1031 (Mascarenhas et al. 2016). Significant clinical improvement was noted following one cycle of VDC with resolution of abdominal ascites and lower extremity edema.

Molecular Studies

Molecular testing for the EWSR1 gene rearrangement was performed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and was positive for the EWSR1 rearrangement in ∼16% of nuclei (Fig. 2F). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmation for FLI1, ERG, and WT1 as partner genes, however, resulted negative. Additional molecular profiling of the tumor was performed through a commercial platform (Personal Genome Diagnostics; Jones et al. 2015) and revealed a somatic missense G1809R mutation in DICER1 in 44% of transcripts, a previously described hotspot mutation affecting the RNaseIIIb domain. No other sequence mutations, amplifications, or translocations were identified within a panel of 203 cancer-associated genes that included those previously shown to be more commonly altered in sarcomas such as TP53, PTEN, MDM2, KRAS, NRAS, NF1, ATRX, CDK4, and RB1. The assay failed to detect a rearrangement in EWSR1, with coverage for breakpoints within introns 7–13 to a sequencing depth of 1500× (Table 2; Supplemental Table S2).

Table 2.

Sequence variants identified by next-generation sequencing (Personal Genome Diagnostics, Cancer Select-203)

| Gene | Origin | Chromosome | HGVS DNA reference | HGVS protein reference | Variant type | Predicted effect | dbSNP/dbVar ID | Genotype | ClinVar ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DICER1 | Tumor | 14:95557642 | NM_177438.2:c.5425G > A | G1809R | Substitution (missense) | Inactivation | rs1595314951 | Heterozygous | SCV000959315.1 and SCV001372111.1 |

| DICER1 | Tumor | 14:95598875 | NM_1774382.2:c.282_283dupAA | p.Arg95Lysfs*34 | Insertion (frameshift) | Inactivation | rs1555376368 | Heterozygous | SCV000658204.1 |

| DICER1 | Normal | 14:95598875 | NM_1774382.2:c.282_283dupAA | p.Arg95Lysfs*34 | Insertion (frameshift) | Inactivation | rs1555376368 | Heterozygous | SCV000658204.1 |

Given the patient's history of multinodular goiter in conjunction with the somatic DICER1 mutation identified in the tumor, there was strong suspicion for inherited DICER1 syndrome. Germline testing was performed and detected a heterozygous mutation in exon 3 of the DICER1 gene, with insertion of two nucleotides (NM_177438.2: c.282.283dupAA) causing a frameshift mutation leading to a premature translational stop signal (p.Arg95Lysfs*34). This was a variant not previously reported but predicted to be a pathogenic loss of function mutation (Table 2; Supplemental Table S2). Thus, this DICER1-associated tumor appeared to arise from a typical tumor-specific DICER1 second hit in the setting of a deleterious germline mutation.

Treatment Outcome

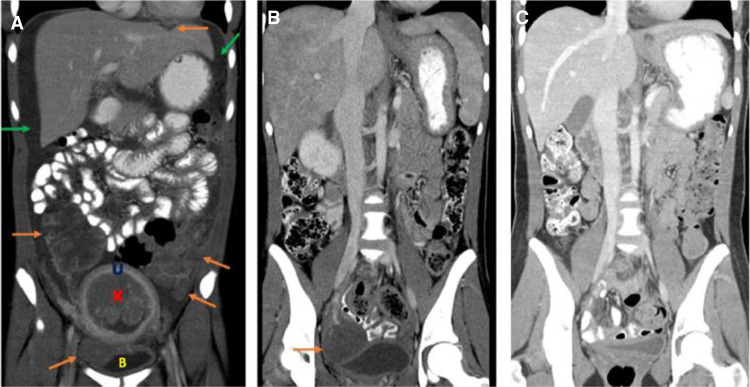

The patient continued treatment with VDC/IE chemotherapy, which was tolerated well. Restaging imaging after six cycles of chemotherapy showed a striking response to treatment with resolution of omental and peritoneal disease and multiple pelvic masses, a residual right pelvic mass that was decreased in size and FDG avidity (Fig. 3). At this time, the decision was made to proceed with aggressive surgical resection of all gross residual disease and previously involved areas. Surgery was performed, and included total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, resection of the right lower quadrant mass, and removal of all grossly visible peritoneal implants. Pathological examination of the resected tumor specimens showed extensive chemotherapy treatment effect with no evidence of remaining viable tumor. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and chemotherapy with VDC/IE was resumed until completion of 14 total cycles. Given the extent of disease at presentation, consolidative radiation therapy was recommended upon completion of chemotherapy. Whole-abdomen–pelvis radiation therapy (WAPRT) and whole-lung irradiation (WLI) was administered to a total of 1500 cGy to the chest and 2400 cGy to the abdomen/pelvis. The patient tolerated the intensive therapy well with no undue side effects.

Figure 3.

Coronal contrast-enhanced computed tomographic (CT) images of the abdomen and pelvis at presentation and after treatment. (A) At presentation demonstrating presence of multiple abdominal/pelvic tumors (orange arrows), intrauterine mass (red X), and malignant ascites (green arrows). (U) Uterus, (B) bladder. (B) After six cycles of chemotherapy demonstrating treatment response with resolution of malignant ascites and significant decrease in tumor burden with residual right pelvic tumor (orange arrow). (C) After surgical resection and completion of chemotherapy demonstrating complete treatment response with no detectable tumor.

Total thyroidectomy for multinodular goiter was performed at ∼1.5 yr post–treatment completion. The patient is now more than 2 years postcompletion of planned treatment and is doing well. Regular surveillance imaging continues, with no concerns for recurrent disease to date.

DISCUSSION

Since the initial description of DICER1 as the causative gene in the pleuropulmonary blastoma inherited cancer syndrome (Hill et al. 2009), DICER1 mutations have been associated with an increasing number of childhood and adult cancers. Several unique cancer entities have been reported in patients with pathogenic DICER1 mutations and include cystic nephroma, anaplastic renal sarcoma (Wu et al. 2018), Wilms tumor, Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor (SLCT) (Schultz et al. 2011), embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, and, more recently, intracranial sarcomas (Koelsche et al. 2018b). Sarcomas comprise a minority of DICER1-associated cancers, but of the 86 DICER1-associated sarcomas reported in the literature to date (Warren et al. 2020), embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus or uterine cervix (n = 28), intracranial sarcoma (n = 26), and anaplastic sarcoma of the kidney (n = 10) are the most common (Stewart et al. 2019; Warren et al. 2020). To our knowledge, only one case of PNET of the abdomen/pelvis, which was reported to arise from the uterine cervix, in a patient with DICER1 mutation has been described (Foulkes et al. 2011). Regardless of their location, DICER1-associated sarcomas reported in the literature demonstrate a heterogeneous histologic appearance including undifferentiated small round blue cells, spindle cells, and/or large anaplastic cells with or without rhabdomyoblastic, chondroid, myxoid differentiation, and bone/osteoid formation (Warren et al. 2020).

Here we describe the case of a 16-yr-old female with a metastatic high-grade malignancy that was difficult to characterize histologically and appeared to have rearrangement of the EWSR1 gene by FISH. The partner gene was not successfully identified via next-generation sequencing and the FISH positivity was low (16%). The focal and incomplete membranous staining pattern of CD99 and rare focal staining pattern of NKX2.2 were not classic for Ewing sarcoma. Also noted by immunostaining was focal positive PAX8, a transcription factor most strongly expressed by thyroid tumors and tumors of Mullerian origin. This tumor was morphologically more similar to primary DICER1-associated central nervous system sarcomas and embryonal tumors with multilayered primitive epithelium. Features of rhabdomyoblastic or chondroid differentiation often seen in DICER1-associated sarcomas were not identified; however, the biopsy specimen was small and the possibility of sampling error cannot be excluded (Warren et al. 2020). Overall, this tumor is best considered a DICER1-associated sarcoma with neuroectodermal differentiation, a morphology that has been described in other DICER1-associated tumors, specifically ciliary body medulloepithelioma and the recently described DICER1-associated presacral malignant teratoid neoplasm (Nakano et al. 2019). The finding of a subset of cells showing EWSR1 rearrangement raises the possibility that this additional mutation was the driver for malignant or more aggressive transformation.

To our knowledge, EWSR1-rearranged sarcomas have not been identified as members of the clinical spectrum of tumors that occur in DICER1 syndrome. EWSR1 is a member of the TET (TLS, EWSR1, TAFII68) family (Thway and Fisher 2019) and a gene commonly involved in translocation-associated sarcomas (Fisher 2014). EWSR1 rearrangements lead to formation of chimeric genes in which the EWSR1 amino-terminal transcriptional activation domain is fused to the carboxy-terminal DNS-binding domain of the partner gene, usually a transcription factor. Although most commonly rearranged in Ewing sarcoma, with the ETS transcription factors FLI1 or ERG, the spectrum of EWSR1-rearranged neoplasms now includes many soft-tissue sarcomas including desmoplastic small round cell tumor (EWSR1-WT1), myxoid liposarcoma (EWSR1-DDIT3), clear cell sarcoma (EWSR1-ATF1 or CREB1), extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EWSR1-NR4A3), and other EWSR1-associated tumors (Fisher 2014; Krystel-Whittemore et al. 2019). Of note, germline DICER1 mutations were not identified in a whole-genome sequencing study of Ewing sarcoma patients, which identified germline mutations most frequently affecting genes involved in DNA repair pathways (Brohl et al 2017).

The striking finding of multinodular goiter in our patient at presentation raised the possibility of DICER1 syndrome, despite the absence of family history to suggest an inherited cancer predisposition. Germline testing for DICER1, in fact, detected a mutation in exon 3 of the DICER1 gene with insertion of two nucleotides (c.282.283dupAA) causing a frameshift mutation leading to a premature translational stop signal (p.Arg95Lysfs*34). This is a variant not previously reported but predicted to be a pathogenic loss of function mutation. Consistent with a two-hit model, next-generation sequencing detected the G1809R missense mutation (variant allele frequency [VAF] 44%), confirming that this malignancy, although not a reported type in DICER1 syndrome, was potentially a novel cancer type in a syndrome increasingly being identified with predisposition to other sarcomas.

Despite an extremely high tumor burden and the extensive metastatic disease at presentation, our patient's sarcoma proved extremely chemotherapy-sensitive. Little is known overall about the optimal multimodality treatment for patients with DICER1-associated sarcomas, and treatment paradigms often rely on those of the tumor type it most closely resembles. In many cases, treatment choices were not those used for sarcomas at all and reflect an emerging knowledge regarding the spectrum of tumors that occur in DICER1 syndrome (Koelsche et al. 2018a). We elected to treat our patient following the U.S. Ewing sarcoma–like paradigm, and that approach proved successful. No viable tumor remained after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, and the surgical approach was similar to the aggressive type of resection usually reserved for desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT), in which the extent of resection has proven to be prognostic (La Quaglia 2014; Hayes-Jordan et al. 2016). Whole-abdomen–pelvis radiation was given, also following the approach used for DSRCT (Casey et al. 2014), which seemed logical in our patient's case, given widespread omental and peritoneal studding. It is unknown which, or perhaps all, of these therapeutic choices resulted in the positive outcome for our patient.

Based on available data from similar patients with extensively metastatic extra-osseous Ewing sarcoma, the chances of survival were low (Miser et al. 2004), which suggests that the biology of the DICER1-PNET is perhaps of a different nature. This hypothesis may also be supported by a similar report of a woman with a malignant thyroid teratoma with neuroectodermal differentiation and a somatic DICER1 mutation. She also received chemotherapy like that given for Ewing sarcoma and had a complete response (Rabinowits et al. 2017). Regardless, this is the first case to our knowledge of a confirmed EWSR1-rearranged sarcoma in a patient with DICER1 syndrome, who was treated successfully and remains alive and well.

METHODS

Next-generation sequencing was conducted using the Cancer Select-203 panel commercially available from Personal Genome Diagnostics (Jones et al. 2015), which evaluates a total of 203 cancer-associated genes for mutations, copy-number variation, and/or translocations. Sequencing was performed using both tumor (abdominal peritoneal implant) and normal (blood) specimens to identify somatic mutations. Sequences were aligned to Human Reference genome hg19. A complete list of genes included in the assay can be found in Supplemental Table S1 and sequencing depth data can be found in Supplemental Table S2. Additional information on the bioinformatics analysis pipeline is available at https://www.personalgenome.com/.

Targeted sequencing of DICER1 for germline mutation testing was performed by Invitae (www.invitae.com) with reads aligned to Human Reference genome hg19.

Additional Information

Data Deposition and Access

Coding variants identified in the Personal Genome Diagnostics Cancer Select-203 analysis are reported in the body of the manuscript. The patient did not provide consent for public deposition of all raw sequencing data for all genes included in the assay. The somatic DICER1 variant was submitted to ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and can be found under accession number SCV001429657.1. The germline DICER1 mutation was previously submitted to ClinVar by Invitae under accession number SCV000658204.1.

Ethics Statement

The patient has provided written consent to publication of relevant clinical information presented in the manuscript and was given the opportunity to read the manuscript prior to publication. The patient understands that material will be freely available on the web and can be freely redistributed and that complete anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dana Petry and Stephanie Terezakis, MD. We additionally acknowledge the patient and her family.

Author Contributions

L.P., D.S.R., J.A.F., and C.A.P. were responsible for patient care and clinical decision making. A.P., L.P., and C.A.P. were responsible for the concept and design. E.D. provided radiographic interpretation and figures. D.B. and J.A.F. provided pathologic diagnosis and figures. A.P., L.P., and C.A.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors performed a final review of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no funding sources to acknowledge.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

REFERENCES

- Bahubeshi A, Bal N, Rio Frio T, Hamel N, Pouchet C, Yilmaz A, Bouron-Dal Soglio D, Williams GM, Tischkowitz M, Priest JR, et al. 2010. Germline DICER1 mutations and familial cystic nephroma. J Med Genet 47: 863–866. 10.1136/jmg.2010.081216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohl AS, Patidar R, Turner CE, Wen X, Song YK, Wei JS, Calzone KA, Khan J. 2017. Frequent inactivating germline mutations in DNA repair genes in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Genet Med 19: 955–958. 10.1038/gim.2016.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey DL, Wexler LH, LaQuaglia MP, Meyers PA, Wolden SL. 2014. Favorable outcomes after whole abdominopelvic radiation therapy for pediatric and young adult sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 61: 1565–1569. 10.1002/pbc.25088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kock L, Wu MK, Foulkes WD. 2019. Ten years of DICER1 mutations: provenance, distribution, and associated phenotypes. Hum Mutat 40: 1939–1953. 10.1002/humu.23877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai SS, Jambhekar NA. 2010. Pathology of Ewing's sarcoma/PNET: current opinion and emerging concepts. Indian J Orthop 44: 363–368. 10.4103/0019-5413.69304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doros L, Schultz KA, Stewart DR, Bauer AJ, Williams G, Rossi CT, Carr A, Yang J, Dehner LP, Messinger Y, et al. 1993. DICER1-related disorders. In GeneReviews [Internet] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24761742

- Doros L, Yang J, Dehner L, Rossi CT, Skiver K, Jarzembowski JA, Messinger Y, Schultz KA, Williams G, André N, et al. 2012. DICER1 mutations in embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas from children with and without familial PPB-tumor predisposition syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59: 558–560. 10.1002/pbc.24020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euscher ED. 2019. Germ cell tumors of the female genital tract. Surg Pathol Clin 12: 621–649. 10.1016/j.path.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure A, Atkinson J, Bouty A, O'Brien M, Levard G, Hutson J, Heloury Y. 2016. DICER1 pleuropulmonary blastoma familial tumour predisposition syndrome: what the paediatric urologist needs to know. J Pediatr Urol 12: 5–10. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C. 2014. The diversity of soft tissue tumours with EWSR1 gene rearrangements: a review. Histopathology 64: 134–150. 10.1111/his.12269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes WD, Bahubeshi A, Hamel N, Pasini B, Asioli S, Baynam G, Choong CS, Charles A, Frieder RP, Dishop MK, et al. 2011. Extending the phenotypes associated with DICER1 mutations. Hum Mutat 32: 1381–1384. 10.1002/humu.21600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes WD, Priest JR, Duchaine TF. 2014. DICER1: mutations, microRNAs and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer 14: 662–672. 10.1038/nrc3802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremerey J, Balzer S, Brozou T, Schaper J, Borkhardt A, Kuhlen M. 2017. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma in a patient with a heterozygous frameshift variant in the DICER1 gene and additional manifestations of the DICER1 syndrome. Fam Cancer 16: 401–405. 10.1007/s10689-016-9958-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata A, Kashima R. 2016. Dysregulation of microRNA biogenesis machinery in cancer. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 51: 121–134. 10.3109/10409238.2015.1117054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Jordan A, LaQuaglia MP, Modak S. 2016. Management of desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Semin Pediatr Surg 25: 299–304. 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DA, Ivanovich J, Priest JR, Gurnett CA, Dehner LP, Desruisseau D, Jarzembowski JA, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Suarez BK, Whelan AJ, et al. 2009. DICER1 mutations in familial pleuropulmonary blastoma. Science 325: 965 10.1126/science.1174334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Anagnostou V, Lytle K, Parpart-Li S, Nesselbush M, Riley DR, Shukla M, Chesnick B, Kadan M, Papp E, et al. 2015. Personalized genomic analyses for cancer mutation discovery and interpretation. Sci Transl Med 7: 283ra53 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa7161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsche C, Hartmann W, Schrimpf D, Stichel D, Jabar S, Ranft A, Reuss DE, Sahm F, Jones DTW, Bewerunge-Hudler M, et al. 2018a. Array-based DNA-methylation profiling in sarcomas with small blue round cell histology provides valuable diagnostic information. Mod Pathol 31: 1246–1256. 10.1038/s41379-018-0045-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsche C, Mynarek M, Schrimpf D, Bertero L, Serrano J, Sahm F, Reuss DE, Hou Y, Baumhoer D, Vokuhl C, et al. 2018b. Primary intracranial spindle cell sarcoma with rhabdomyosarcoma-like features share a highly distinct methylation profile and DICER1 mutations. Acta Neuropathol 136: 327–337. 10.1007/s00401-018-1871-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystel-Whittemore M, Taylor MS, Rivera M, Lennerz JK, Le LP, Dias-Santagata D, Iafrate AJ, Deshpande V, Chebib I, Nielsen GP, et al. 2019. Novel and established EWSR1 gene fusions and associations identified by next-generation sequencing and fluorescence in-situ hybridization. Hum Pathol 93: 65–73. 10.1016/j.humpath.2019.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T. 2007. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet 39: 673–677. 10.1038/ng2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Quaglia MP. 2014. State of the art in oncology: high risk neuroblastoma, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, and POST-TEXT 3 and 4 hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Surg 49: 233–240. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, et al. 2005. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 435: 834–838. 10.1038/nature03702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas L, Felgenhauer JL, Bond MC, Villaluna D, Femino JD, Laack NN, Ranganathan S, Meyer J, Womer RB, et al. 2016. Pilot study of adding vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide to interval-compressed chemotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with localized Ewing sarcoma: a report from the children's oncology group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63: 493–498. 10.1002/pbc.25837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miser JS, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, Link MP, Fryer CJH, Pritchard DJ, Gebhardt MC, Dickman PS, Perhnan EJ, Meyers PA, et al. 2004. Treatment of metastatic Ewing's sarcoma or primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone: evaluation of combination ifosfamide and etoposide—a children's cancer group and pediatric oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 22: 2873–2876. 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Hasegawa D, Stewart DR, Schultz KAP, Harris AK, Hirato J, Uemura S, Tamura A, Saito A, Kawamura A, et al. 2019. Presacral malignant teratoid neoplasm in association with pathogenic DICER1 variation. Mod Pathol 32: 1744–1750. 10.1038/s41379-019-0319-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh TJ, Yu W, Yang J, Field AL, Ambrogio L, Carter SL, Cibulskis K, Giannikopoulos P, Kiezun A, Kim J, et al. 2014. Exome sequencing of pleuropulmonary blastoma reveals frequent biallelic loss of TP53 and two hits in DICER1 resulting in retention of 5p-derived miRNA hairpin loop sequences. Oncogene 33: 5295–5302. 10.1038/onc.2014.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowits G, Barletta J, Sholl LM, Reche E, Lorch J, Goguen L. 2017. Successful management of a patient with malignant thyroid teratoma. Thyroid 27: 125–128. 10.1089/thy.2016.0201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio Frio T, Bahubeshi A, Kanellopoulou C, Hamel N, Niedziela M, Sabbaghian N, Pouchet C, Gilbert L, O'Brien PK, Serfas K, et al. 2011. DICER1 mutations in familial multinodular goiter with and without ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors. J Am Med Assoc 305: 68–77. 10.1001/jama.2010.1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz KAP. 2018. DICER1 and associated conditions: identifications of at-risk individuals and recommended surveillance strategies. Clin Cancer Res 176: 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz KAP, Pacheco MC, Yang J, Williams GM, Messinger Y, Hill DA, Dehner LP, Priest JR. 2011. Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors, pleuropulmonary blastoma and DICER1 mutations: a report from the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry. Gynecol Oncol 122: 246–250. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade I, Bacchelli C, Davies H, Murray A, Abbaszadeh F, Hanks S, Barfoot R, Burke A, Chisholm J, Hewitt M, et al. 2011. DICER1 syndrome: clarifying the diagnosis, clinical features and management implications of a pleiotropic tumour predisposition syndrome. J Med Genet 48: 273–278. 10.1136/jmg.2010.083790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DR, Best AF, Williams GM, Harney LA, Carr AG, Harris AK, Kratz CP, Dehner LP, Messinger YH, Rosenberg PS, et al. 2019. Neoplasm risk among individuals with a pathogenic germline variant in DICER1. J Clin Oncol 37: 668–676. 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.4678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thway K, Fisher C. 2019. Mesenchymal tumors with EWSR1 gene rearrangements. Surg Pathol Clin 12: 165–190. 10.1016/j.path.2018.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren M, Hiemenz MC, Schmidt R, Shows J, Cotter J, Toll S, Parham DM, Biegel JA, Mascarenhas L, Shah R. 2020. Expanding the spectrum of dicer1-associated sarcomas. Mod Pathol 33: 164–174. 10.1038/s41379-019-0366-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womer RB, West DC, Krailo MD, Dickman PS, Pawel BR, Grier HE, Marcus K, Sailer S, Healey JH, Dormans JP, et al. 2012. Randomized controlled trial of interval-compressed chemotherapy for the treatment of localized Ewing sarcoma: a report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol 30: 4148–4154. 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.5703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormald B, Elorbany S, Hanson H, Williams JW, Heenan S, Barton DPJ. 2018. Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour and DICER1 mutation: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2018: 7927362 10.1155/2018/7927362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MK, Vujanic GM, Fahiminiya S, Watanabe N, Thorner PS, O'Sullivan MJ, Fabian MR, Foulkes WD. 2018. Anaplastic sarcomas of the kidney are characterized by DICER1 mutations. Mod Pathol 31: 169–178. 10.1038/modpathol.2017.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zynger DL, Everton MJ, Dimov ND, Chou PM, Yang XJ. 2008. Expression of glypican 3 in ovarian and extragonadal germ cell tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 130: 224–230. 10.1309/8DN7DQRDFB4QNH3N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Coding variants identified in the Personal Genome Diagnostics Cancer Select-203 analysis are reported in the body of the manuscript. The patient did not provide consent for public deposition of all raw sequencing data for all genes included in the assay. The somatic DICER1 variant was submitted to ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and can be found under accession number SCV001429657.1. The germline DICER1 mutation was previously submitted to ClinVar by Invitae under accession number SCV000658204.1.