Highlights

-

•

Vitamin D may be a central biological determinant of COVID-19 outcomes.

-

•

Bolus vitamin D3 supplementation during or just before COVID-19 was associated with less severe COVID-19 in frail elderly.

-

•

Bolus vitamin D3 supplementation during or just before COVID-19 was associated with better survival rate in frail elderly.

-

•

Randomized controlled trials are expected to firmly conclude the effect of vitamin D supplementation on COVID-19 prognosis.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Vitamin D, Therapeutics, Quasi-experimental study, Older adults

Abstract

Vitamin D may be a central biological determinant of COVID-19 outcomes. The objective of this quasi-experimental study was to determine whether bolus vitamin D3 supplementation taken during or just before COVID-19 was effective in improving survival among frail elderly nursing-home residents with COVID-19. Sixty-six residents with COVID-19 from a French nursing-home were included in this quasi-experimental study. The “Intervention group” was defined as those having received bolus vitamin D3 supplementation during COVID-19 or in the preceding month, and the “Comparator group” corresponded to all other participants. The primary and secondary outcomes were COVID-19 mortality and Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement (OSCI) score in acute phase, respectively. Age, gender, number of drugs daily taken, functional abilities, albuminemia, use of corticosteroids and/or hydroxychloroquine and/or antibiotics (i.e., azithromycin or rovamycin), and hospitalization for COVID-19 were used as potential confounders. The Intervention (n = 57; mean ± SD, 87.7 ± 9.3years; 79 %women) and Comparator (n = 9; mean, 87.4 ± 7.2years; 67 %women) groups were comparable at baseline, as were the COVID-19 severity and the use of dedicated COVID-19 drugs. The mean follow-up time was 36 ± 17 days. 82.5 % of participants in the Intervention group survived COVID-19, compared to only 44.4 % in the Comparator group (P = 0.023). The full-adjusted hazard ratio for mortality according to vitamin D3 supplementation was HR = 0.11 [95 %CI:0.03;0.48], P = 0.003. Kaplan-Meier distributions showed that Intervention group had longer survival time than Comparator group (log-rank P = 0.002). Finally, vitamin D3 supplementation was inversely associated with OSCI score for COVID-19 (β=-3.84 [95 %CI:-6.07;-1.62], P = 0.001). In conclusion, bolus vitamin D3 supplementation during or just before COVID-19 was associated in frail elderly with less severe COVID-19 and better survival rate.

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, the COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 is spreading worldwide from China, affecting millions of people and leaving thousands of dead, mostly in older adults. With the lack of effective therapy, chemoprevention and vaccination [1], focusing on the immediate repurposing of existing drugs gives hope of curbing the pandemic. Importantly, a most recent genomics-guided tracing of the SARS-CoV-2 targets in human cells identified vitamin D among the three top-scoring molecules manifesting potential infection mitigation patterns through their effects on gene expression [2]. In particular, by activating or repressing several genes in the promoter region of which it binds to the vitamin D response element [3], vitamin D may theoretically prevent or improve COVID-19 adverse outcomes by regulating (i) the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), (ii) the innate and adaptive cellular immunity, and (iii) the physical barriers [4]. Consistently, epidemiology shows that hypovitaminosis D is more common from October to March at northern latitudes above 20 degrees [3], which corresponds precisely to the latitudes with the highest lethality rates of COVID-19 during the first months of winter 2020 [1]. In line with this, significant inverse associations were found in 20 European countries between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentration and the number of COVID-19 cases, as well as with COVID-19 mortality [5]. This suggests that increasing serum 25(OH)D concentration may improve the prognosis of COVID-19. However, no randomized controlled trial (RCT) has tested the effect of vitamin D supplements on COVID-19 outcomes yet. We had the opportunity to examine the association between the use of vitamin D3 supplements and COVID-19 mortality in a sample of frail elderly nursing-home residents infected with SARS-CoV-2. The main objective of this quasi-experimental study was to determine whether bolus vitamin D3 supplementation taken during or just before COVID-19 was effective in improving survival among frail elderly COVID-19 patients living in nursing-home. The secondary objective was to determine whether this intervention was effective in limiting the clinical severity of the infection.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study population

The study consisted in a quasi-experimental study in a middle-sized nursing-home in Rhône, South-East of France, the residents of which were largely affected by COVID-19 in March-April 2020 (N = 96, including n = 66 with COVID-19). Data were retrospectively collected from the residents’ records of the nursing-home.

The nursing-home is dedicated to residents with physical disabilities, major neurocognitive and psychiatric disorders. The facility includes 56 single rooms and 21 double rooms, along with communal dining and activity areas. There are no closed units. All residents were allowed to move around the building until 21 March 2020, when social distancing and other preventive measures were implemented. Residents were isolated in their rooms with no communal meals or group activities. No visitors, including families, were allowed in the nursing-home since 10 March 2020. Enhanced hygiene measures were implemented, including cleaning and disinfection of frequently touched surfaces, permanent face masks, and additional hand hygiene stations for staff members.

The inclusion criteria for the present analysis were as follows: 1) residents with clinically obvious or diagnosed COVID-19 with RT-PCR in March-April 2020; 2) data available on the treatments received, including vitamin D supplementation, since the diagnosis of COVID-19 and during the previous month at least; 3) data available on the vital status and COVID-19 evolution as of May 15, 2020; 4) no objection from the resident and/or relatives to the use of anonymized clinical and biological data for research purposes. Sixty-six residents had COVID-19 during the study period. They all met the other inclusion criteria and were included in the present analysis.

2.2. Intervention: bolus vitamin D3 supplementation during or just before COVID-19

All residents in the nursing-home receive chronic vitamin D supplementation with regular maintenance boluses (single oral dose of 80,000 IU vitamin D3 every 2–3 months), without systematically performing serum control test as recommended in French nursing-homes [6] due to the very high prevalence of hypovitaminosis D reaching 90–100 % in this population [7]. Here, the "Intervention group" was defined as all COVID-19 residents who received an oral bolus of 80,000 IU vitamin D3 either in the week following the suspicion or diagnosis of COVID-19, or during the previous month. The "Comparator group" corresponded to all other COVID-19 residents who did not receive any recent vitamin D supplementation. None received D2 or intramuscular supplements. All medications were dispended and supervised by a nurse.

2.3. Primary outcome: COVID-19 mortality

The primary outcome was mortality of COVID-19 residents during follow-up. Follow-up started from the day of COVID-19 diagnosis for each patient, and continued until May 15, 2020, or until death if applicable.

2.4. Secondary outcome: OSCI score for COVID-19 in acute phase

The secondary outcome was the score on the World Health Organization’s Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement (OSCI) for COVID-19 [8]. The score was calculated by the geriatrician of the nursing-home during the most severe acute phase of COVID-19 for each patient. The OSCI distinguishes between several levels of COVID-19 clinical severity according to the outcomes and dedicated treatments required, with a score ranging from 0 (benign) to 8 (death). A score of 4 corresponds to the introduction of oxygen (nasal oxygen catheter or oral nasal mask), and a score of 6 to intubation and invasive ventilation [8].

2.5. Covariables

Age, gender, number of drugs daily taken, functional abilities, nutritional status, COVID-19 treatment with corticosteroids and/or hydroxychloroquine and/or dedicated antibiotics, and hospitalization for COVID-19 were used as potential confounders. The number of drugs usually taken per day was recovered from prescriptions in the nursing-home and served as a measure of the burden of disease, as previously reported [9]. The use of corticosteroids and/or hydroxychloroquine and/or dedicated antibiotics (i.e., azithromycin or rovamycin) were noted from prescriptions in the nursing-home or during hospitalization, as appropriate. Functional abilities prior to COVID-19 were measured from 1 to 6 (best) with the Iso-Resources Groups (GIR) [10]. Finally, the prognosis related to the nutritional status prior to COVID-19 was evaluated using the last measure of serum albumin concentration during the past semester, as appropriate [11].

2.6. Statistical analysis

Participants’ characteristics were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD) or frequencies and percentages, as appropriate. As the number of observations was higher than 40, comparisons were not affected by the shape of the error distribution and no transform was applied [12]. First, comparisons between participants separated into Intervention and Comparator groups were performed using Mann-Whitney U test or the Chi-square test or Fisher test, as appropriate; and then according to mortality. Secondly, a full-adjusted Cox regression was used to examine the associations of mortality (dependent variable) with bolus vitamin D3 supplements and covariables (independent variables). The model produces a survival function that provides the probability of death at a given time for the characteristics supplied for the independent variables. Third, the elapsed time to death was studied by survival curves computed according to Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test. Finally, univariate and multiple linear regressions were used to examine the association of bolus vitamin D3 supplementation (independent variable) with OSCI score (dependent variable), while adjusting for potential confounders. P-values<0.05 were considered significant. All statistics were performed using SPSS (v23.0, IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL) and SAS® version 9.4 software (Sas Institute Inc).

2.7. Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set forth in the Helsinki Declaration (1983). No participant or relatives objected to the use of anonymized clinical and biological data for research purposes. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Angers University Hospital (2020/67). The study protocol was also declared to the National Commission for Information technology and civil Liberties (CNIL, number 202000081).

3. Results

Sixty-six participants (mean ± SD age 87.7 ± 9.0years, range 63−103years; 77.3 % women) were infected with SARS-CoV-2 and included in this quasi-experimental study. The mean follow-up was 36 ± 17days. Fifty-one people survived COVID-19, while 15 died. The two groups were comparable at baseline with no significant difference regarding the age (P = 0.699), gender (P = 0.731), the mean number of drugs usually taken per day (P = 0.053), the GIR score (P = 0.209) and the serum albumin concentration (P = 0.263) (Table 1 ). Regarding care dedicated to COVID-19, only the proportion of patients who received a bolus of vitamin D3 during or just before COVID-19 differed between deceased participants and survivors, with a higher prevalence in survivors (respectively 92.2 % versus 66.7 %, P = 0.023). In contrast, there was no between-group difference in the proportion of patients treated with corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine or dedicated antibiotics, or hospitalized for COVID-19.

Table 1.

Characteristics and comparison of COVID-19 participants (n = 66) according to the study arm.

| All COVID-19 participants (n = 66) | Study arm |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparator group* (n = 9) | Intervention group* (n = 57) | |||

| Baseline data | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 87.7 ± 9.0 | 87.4 ± 7.2 | 87.7 ± 9.3 | 0.660 |

| Female gender | 51 (77.3) | 6 (66.7) | 45 (78.9) | 0.414 |

| Number of drugs usually taken per day, mean ± SD | 7 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 0.043 |

| GIR score (/6), mean ± SD | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 0.4 | 2 ± 1 | 0.003 |

| Serum albumin concentration† (g/L), mean ± SD | 34.2 ± 5.2 | 35.4 ± 2.5 | 34.1 ± 5.4 | 0.250 |

| COVID-19 | ||||

| Dedicated treatments | ||||

| Use of corticosteroids | 4 (6.1) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (5.3) | 0.452 |

| Use of hydroxychloroquine | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) | 1.000 |

| Use of dedicated antibiotics | 34 (51.5) | 3 (33.3) | 21 (54.4) | 0.297 |

| Hospitalization for COVID-19 | 4 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.0) | 1.000 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| OSCI score for COVID-19 in acute phase | 0.133 | |||

| OSCI 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| OSCI 1 | 22 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 21 (37.5) | |

| OSCI 2 | 19 (28.8) | 1 (11.1) | 18 (32.1) | |

| OSCI 3 | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| OSCI 4 | 5 (7.6) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (7.1) | |

| OSCI 5 | 3 (4.5) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (3.6) | |

| OSCI 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| OSCI 7 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| OSCI 8 | 15 (22.7) | 5 (55.6) | 10 (17.5) | |

| Mortality | 15 (22.7) | 5 (55.6) | 10 (17.5) | 0.023 |

| Follow-up after COVID-19 diagnosis‡(days), mean ± SD | 36 ± 17 | 20.9 ± 14.3 | 38.9 ± 15.6 | 0.002 |

Data presented as n (%) where applicable; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; GIR: Iso Resource Groups; OSCI: Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement of the World Health Organization; *: “Intervention group” defined as COVID-19 patients having received a bolus of vitamin D3 supplement during COVID-19 or in the preceding month; †: measured in preceding 6 months; ‡: data were censored at the time of data cutoff (15 May 2020) or until death, as appropriate.

Table 1 indicates the characteristics of participants separated into Intervention (n = 57) and Comparator (n = 9) groups. Their baseline characteristics (age, gender, albuminemia) did not differ between groups, with the exception of the number of drugs usually taken (which involved the use of vitamin D supplements) and the disability score (Table 1). Similarly, the proportion of participants at each OSCI severity level as well as the use of dedicated COVID-19 drugs did not differ between Intervention and Comparator groups. At the end of the follow-up, 82.5 % of patients from the Intervention group survived COVID-19, compared to only 44.4 % in the Comparator group (P = 0.023).

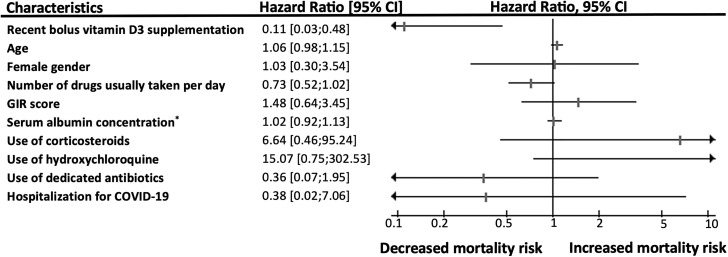

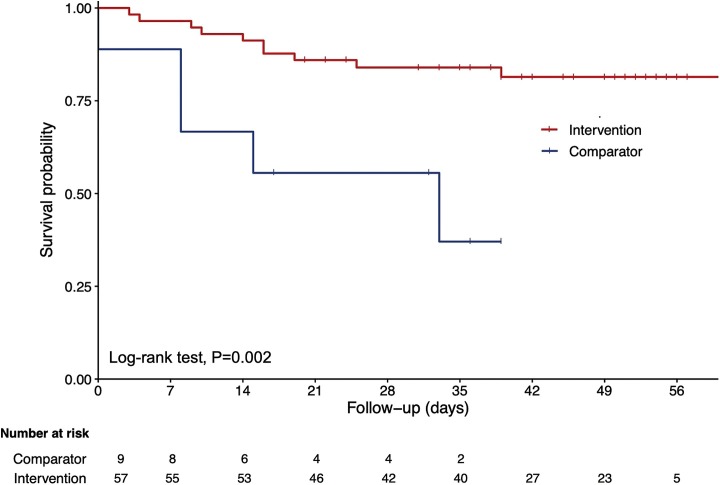

Fig. 1 shows a statistically significant and clinically relevant protective effect against mortality of bolus vitamin D3 supplementation received during or just before COVID-19. The hazard ratio (HR) for mortality according to vitamin D3 supplementation was 0.21 [95 % confidence interval (95 %CI): 0.07;0.63] P = 0.005 in the unadjusted model, and HR = 0.11 [95 %CI: 0.03;0.48] P = 0.003 after adjustment for all potential confounders. No other covariables were associated with mortality, in particular no other dedicated treatments. Using the season of the COVID-19 diagnosis as an additional potential confounder did not affect the results (data not shown). Consistently, Kaplan-Meier distributions showed in Fig. 2 that the residents who had not recently received vitamin D3 supplements had shorter survival time than those having received vitamin D3 supplementation during or just before COVID-19 (log-rank P = 0.002).

Fig. 1.

Hazard ratio for mortality in frail elderly COVID-19 patients according to the use of bolus vitamin D3 supplements during or just before COVID-19, adjusted for potential confounders (n = 66).

CI: confidence interval; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; GIR: Iso Resource Groups; *: measured in preceding 6 months.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative probability of participants’ survival according to the use of bolus vitamin D3 supplements during or just before COVID-19 (n = 66).

Finally, the linear regression model illustrated in Table 2 showed that bolus vitamin D3 supplementation during or just before COVID-19 was inversely associated with the OSCI score for COVID-19 in acute phase. Similar results were found before (β=-2.96 [95 %CI: -4.79;-1.12], P = 0.002) and after adjusting the analyses for potential confounders (β=-3.84 [95 %CI: -6.07;-1.62], P = 0.001).

Table 2.

Univariate and multiple linear regressions showing the association of the use of bolus vitamin D3 supplements during or just before COVID-19 (independent variable) with the OSCI score for COVID-19 in acute phase (dependent variable), adjusted for participants' characteristics (n = 66).

| OSCI score for COVID-19 in acute phase |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model |

Full-adjusted model |

|||

| Unadjusted β [95 % CI] | P-value | Full-adjusted β [95 % CI] | P-value | |

| Bolus vitamin D3 supplementation during or just before COVID-19 | −2.96 [-4.79;-1.12] | 0.002 | −3.84 [-6.07;-1.62] | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.02 [-0.05;0.10] | 0.563 | 0.04 [-0.05;0.12] | 0.400 |

| Female gender | −0.13 [-1.76;1.49] | 0.870 | 0.36 [-1.41;2.12] | 0.687 |

| Number of drugs usually taken per day | −0.26 [-0.54;0.02] | 0.070 | −0.18 [-0.51;0.15] | 0.273 |

| GIR score | −0.28 [-0.86;0.30] | 0.333 | 0.21 [-0.48;0.89] | 0.617 |

| Serum albumin concentration* | 0.03 [-0.11;0.17] | 0.647 | −0.001 [-0.15;0.15] | 0.993 |

| Use of corticosteroids | 2.41 [-0.36;5.20] | 0.087 | 3.53 [0.30;6.75] | 0.033 |

| Use of hydroxychloroquine | 1.83 [-2.11;5.76] | 0.357 | 2.49 [-1.59;6.57] | 0.226 |

| Use of dedicated antibiotics | −0.22 [-1.59;1.14] | 0.746 | −0.56 [-2.21;1.10] | 0.503 |

| Hospitalization for COVID-19 | 1.09 [-1.75;3.92] | 0.446 | 0.72 [-2.48;3.93] | 0.652 |

β: coefficient of regression corresponding to a change in OSCI score for COVID-19 in acute phase (/8); CI: confidence interval; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; GIR: Iso Resource Groups; OSCI: Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement of the World Health Organization; *: measured in preceding 6 months.

4. Discussion

The main finding of this nursing-home-based quasi-experimental study is that, irrespective of all measured potential confounders, bolus vitamin D3 supplementation during or just before COVID-19 was associated with less severe COVID-19 and better survival rate in frail elderly. No other treatment showed protective effect. This novel finding provides a scientific basis for vitamin D replacement trials attempting to improve COVID-19 prognosis.

To our knowledge we provide here the first quasi-experimental data examining the effect of vitamin D supplementation on the survival rate of COVID-19 patients. To date, only rare observational data, all of which are consistent, are available on the link between vitamin D and COVID-19. The first reports in COVID-19 patients indicated that adults with hypovitaminosis D are at greater risk of being infected with SARS-CoV-2 (RR = 1.77 with P < 0.02) [13], and that serum 25(OH)D concentrations are lower in COVID-19 patients compared to controls [14]. Similarly, significant inverse correlations were found in 20 European countries between the mean serum 25(OH)D concentrations and the number of COVID-19 cases, as well as with mortality [5]. The severity of hypovitaminosis D appears to relate to the prognosis of COVID-19 since, in the event of COVID-19, exhibiting hypovitaminosis D was associated with greater risks of having severe COVID-19 (OR = 1.95 with P = 0.029), of being hospitalized (OR = 1.77 with P = 0.026) and with a longer hospital stay (β = 0.47 with P < 0.001) [15]. Finally, hypovitaminosis D was found to be associated with greater COVID-19 mortality risk (IRR = 1.56 with P < 0.001 if vitamin D deficiency; P = 0.404 after adjustment) [16]. These results suggest that increasing serum 25(OH)D concentration may improve the prognosis of COVID-19. Interventional studies dedicated to COVID-19 are yet warranted for investigating the role of vitamin D supplementation on COVID-19 outcomes. Interestingly, previous meta-analyses found that high-dose prophylactic vitamin D supplementation was able to reduce the risk of respiratory tract infections [17]. Based on this observation, we and others are conducting an RCT designed to test the effect of high-dose versus standard-dose vitamin D3 on 14-day mortality in COVID-19 older patients (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04344041). While waiting for the recruitment of this RCT to be completed, the findings of the present quasi-experimental study strongly suggest a benefit of bolus vitamin D3 supplementation on COVID-19 outcomes and survival.

How vitamin D supplementation may improve COVID-19 outcomes and survival is not fully elucidated. Three mechanisms are possible: regulation of (i) the RAS, (ii) the innate and adaptive cellular immunity, and (iii) the physical barriers [4]. First, vitamin D reduces pulmonary permeability in animal models of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) by modulating the activity of RAS and the expression of the angiotensin-2 converting enzyme (ACE2) [18]. This action is crucial since SARS-CoV-2 reportedly uses ACE2 as a receptor to infect host cells [19] and downregulates ACE2 expression [20]. ACE2 is expressed in many organs, including the endothelium and the pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells, where it has protective effects against inflammation [21]. During COVID-19, downregulation of ACE2 results in an inflammatory chain reaction, the cytokine storm, complicated by ARDS [22]. In contrast, a study in rats with chemically-induced ARDS showed that the administration of vitamin D increased the levels of ACE2 mRNA and proteins [23]. Rats supplemented with vitamin D had milder ARDS symptoms and moderate lung damage compared to controls. Second, many studies have described the antiviral effects of vitamin D, which works either by induction of antimicrobial peptides with direct antiviral activity against enveloped and non-enveloped viruses, or by immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects [24]. These are potentially important during COVID-19 to limit the cytokine storm. Vitamin D can prevent ARDS [25] by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines, such as TNFα and interferon γ [24]. It also increases the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines by macrophages [24]. Third, vitamin D stabilizes physical barriers [4]. These barriers are made up of closely linked cells to prevent outside agents (such as viruses) from reaching tissues susceptible to viral infection. Although viruses alter the integrity of the cell junction, vitamin D contributes to the maintenance of functional tight junctions via E-cadherin [4]. All these antiviral effects could potentiate each other and explain our results.

We also found that none of the other dedicated drugs used in this quasi-experimental study was associated with better survival rate in COVID-19 patients. The interest of these drugs in COVID-19 is still debated, whether for hydroxychloroquine [26] or azithromycin [27] even if the administration of systemic corticosteroids has shown some interest on mortality risk in critically ill patients with COVID-19 [28]. However, it should be noted that these drugs were given here as part of patient care in the most advanced and severe clinical situations, which could have biased and masked their effectiveness (if any).

The strengths of the present study include i) the originality of the research question on an emerging infection for which there is no validated treatment, ii) the detailed description of the participants’ characteristics allowing the use of multivariate models to measure adjusted associations, and iii) the standardized collection of data from a single research center.

Regardless, a number of limitations also existed. First, the study cohort was restricted to a limited number of nursing-home residents who might be unrepresentative of all older adults. Second, although we were able to control for the important characteristics that could modify the association, residual potential confounders might still be present such as the serum concentration of 25(OH)D at baseline - a low level classically ensuring the effectiveness of the supplementation [29]. As this analysis was not initially planned, no concerted efforts were made to systematically measure the serum 25(OH)D concentration before and after supplementation. Third, the quasi-experimental design of our study is less robust than an RCT. Participants in the Comparator group did not receive vitamin D placebo, and there was no randomization. It should yet be noted that the characteristics of the two groups did not differ at baseline, which allows interpreting the survival difference as linked to the vitamin D3 supplementation.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we were able to report among frail elderly residents that bolus vitamin D3 supplementation taken during or just before COVID-19 was associated with less severe COVID-19 and better survival rate. No other treatment showed protective effect.

Vitamin D3 supplementation may represent an effective, accessible and well-tolerated treatment for COVID-19, the incidence of which increases dramatically and for which there are currently no treatments. Further prospective, preferentially interventional, studies are needed to confirm whether supplementing older adults with bolus vitamin D3 during or just before the infection could improve, or prevent, COVID-19.

Sponsor’s role

No sources of funding were used to assist in this study.

Authors contribution

-

-

CA has full access to all of the data in the study, takes responsibility for the data, the analyses and interpretation and has the right to publish any and all data, separate and apart from the attitudes of the sponsors. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

-

-

Study concept and design: CA, BH, CGE, JMS, LL and TC.

-

-

Acquisition of data: BH and CGE.

-

-

Analysis and interpretation of data: CA and TC.

-

-

Drafting of the manuscript: CA.

-

-

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: BH, CGE, JMS, LL and TC.

-

-

Obtained funding: Not applicable.

-

-

Statistical expertise: CA.

-

-

Administrative, technical, or material support: CA and TC.

-

-

Study supervision: CA.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their collaborators:

- Angeline MEY, MD, from the Department of Clinical Gerontology, University Hospital of Saint-Etienne, Saint-Etienne, France;

- Pauline GUILLEMIN, MD, from the Geriatric Hospital of Saint Symphorien sur Coise, Saint Symporien sur Coise, France;

- Jennifer GAUTIER, MS, from the Research Center on Autonomy and Longevity, University Hospital, Angers, France.

There was no compensation for their contribution.

References

- 1.Ahn D.G., Shin H.J., Kim M.H., Sunhee L., Hae-Soo K., Jinjong M. Current Status of Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Therapeutics, and Vaccines for Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020;30:313–324. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2003.03011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glinsky G.V. Tripartite Combination of Candidate Pandemic Mitigation Agents: Vitamin D, Quercetin, and Estradiol Manifest Properties of Medicinal Agents for Targeted Mitigation of the COVID-19 Pandemic Defined by Genomics-Guided Tracing of SARS-CoV-2 Targets in Human Cells. Biomedicines. 2020;8:129. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8050129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hossein-nezhad A., Holick M.F. Vitamin D for health: a global perspective. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013;88:720–755. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant W.B., Lahore H., McDonnell S.L., Baggerly C.A., French C.B., Aliano J.L. Evidence that vitamin d supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):988. doi: 10.3390/nu12040988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilie P.C., Stefanescu S., Smith L. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 infection and mortality. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rolland Y., de Souto Barreto P., Abellan Van Kan G., Annweiler C., Beauchet O., Bischoff-Ferrari H. Vitamin D supplementation in older adults: searching for specific guidelines in nursing-homes. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2013;17:402–412. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annweiler C., Souberbielle J.C., Schott A.M., de Decker L., Berrut G., Beauchet O. Vitamin D in the elderly: 5 points to remember. Geriatr. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. 2011;9:259–267. doi: 10.1684/pnv.2011.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) R&D. WHO. https://www.who.int/teams/blueprint/covid-19 Accessed 19 May 2020.

- 9.De Decker L., Launay C., Annweiler C., Kabeshova A., Beauchet O. Number of drug classes taken per day may be used to assess morbidity burden in older inpatients: a pilot cross-sectional study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013;61:1224–1225. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vetel J.M., Leroux R., Ducoudray J.M. AGGIR. Practical use. Geriatric autonomy group resources needs. Soins Gerontol. 1998;(13):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabrerizo S., Cuadras D., Gomez-Busto F., Artaza-Artabe I., Marín-Ciancas F., Malafarina V. Serum albumin and health in older people: review and meta analysis. Maturitas. 2015;81:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rochon J., Gondan M., Kieser M. To test or not to test: preliminary assessment of normality when comparing two independent samples. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012;12:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meltzer D.O., Best T.J., Zhang H., Vokes T., Arora V., Solway J. Association of vitamin d status and other clinical characteristics with covid-19 test results. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3:e2019722. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Avolio A., Avataneo V., Manca A., Cusato J., De Nicolò A., Lucchini R. 25-hydroxyvitamin d concentrations are lower in patients with positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1359. doi: 10.3390/nu12051359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendy A., Apewokin V., Wells A.A., Morrow A.L. Factors associated with hospitalization and disease severity in a racially and ethnically diverse population of COVID-19 patients. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.25.20137323. Preprint . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastie C.E., Mackay D.F., Ho F., Celis-Morales C.A., Katikireddi S.V., Niedzwiedz C.L. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14:561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martineau A.R., Jolliffe D.A., Hooper R.L., Greenberg L., Aloia J.F., Bergman P. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong J., Zhu X., Shi Y., Liu T., Chen Y., Bhan I. VDR attenuates acute lung injury by blocking Ang-2-Tie-2 pathway and renin-angiotensin system. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013;27:2116–2125. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dijkman R., Jebbink M.F., Deijs M., Milewska A., Pyrc K., Buelow E. Replication-dependent downregulation of cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protein expression by human coronavirus NL63. J. Gen. Virol. 2012;93:1924–1929. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043919-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annweiler C., Cao Z., Wu Y., Faucon E., Mouhat S., Kovacic H. Counter-regulatory’ Renin-Angiotensin’ system-based candidate drugs to treat COVID-19 diseases in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets. 2020 doi: 10.2174/1871526520666200518073329. Epub May 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji X., Zhang C., Zhai Y., Zhang Z., Zhang C., Xue Y. TWIRLS, an Automated Topic-Wise Inference Method Based on Massive Literature, Suggests a Possible Mechanism via ACE2 for the Pathological Changes in the Human Host after Coronavirus Infection. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.27.967588. 02.27.967588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang J., Zhang H., Xu J. Effect of Vitamin D on ACE2 and Vitamin D receptor expression in rats with LPS-induced acute lung injury. Chinese J Emerg Med. 2016;25:1284–1289. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabbri A., Infante M., Ricordi C. Editorial - Vitamin D status: a key modulator of innate immunity and natural defense from acute viral respiratory infections. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;24:4048–4052. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dancer R.C., Parekh D., Lax S., D’Souza V., Zheng S., Bassford C.R. Vitamin d deficiency contributes directly to the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) Thorax. 2015;70:617–624. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferner R.E., Aronson J.K. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in covid-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gbinigie K., Frie K. Should azithromycin be used to treat COVID-19? A rapid review. BJGP Open. 2020;4 doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101094. bjgpopen20X101094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Sterne J.A.C., Murthy S., Diaz J.V., Slutsky A.S., Villar J., Angus D.C. Association Between Administration of Systemic Corticosteroids and Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heaney R.P. Guidelines for optimizing design and analysis of clinical studies of nutrient effects. Nutr. Rev. 2014;72:48–54. doi: 10.1111/nure.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]