Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Cigarettes are the most harmful and most prevalent tobacco product in the United States (U.S.). This study examines cross-sectional prevalence and longitudinal pathways of cigarette use among U.S. youth (12–17 years), young adults (18–24 years), and adults 25+ (25 years and older).

DESIGN

Data were drawn from the first three waves (2013–2016) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, a nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of U.S. youth and adults. Respondents with data at all three waves (youth, N = 11,046; young adults, N = 6,478; adults 25+, N = 17,188) were included in longitudinal analyses.

RESULTS

Among Wave 1 (W1) any past 30-day (P30D) cigarette users, more than 60% persistently used cigarettes across three waves in all age groups. Exclusive cigarette use was more common among adult 25+ W1 P30D cigarette users (62.6%) while cigarette polytobacco use was more common among youth (57.1%) and young adults (65.2%). Persistent exclusive cigarette use was the most common pathway among adults 25+ and young adults; transitioning from exclusive cigarette use to cigarette polytobacco use was most common among youth W1 exclusive cigarette users. For W1 youth and young adult cigarette polytobacco users, the most common pattern of use was persistent cigarette polytobacco use.

CONCLUSIONS

Cigarette use remains persistent across time, regardless of age, with most W1 P30D smokers continuing to smoke at all three waves. Policy efforts need to continue focusing on cigarettes, in addition to products such as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) that are becoming more prevalent.

INTRODUCTION

Cigarettes are the most common tobacco product in the United States (U.S.), with approximately 61 million people in 2016 having smoked cigarettes in the past year, almost 2 million of them younger than age 18.1 Cigarette use is more than twice as prevalent as the use of any other tobacco product among US adults; in 2014, 18.1% currently smoked cigarettes, and 16.0% smoked cigarettes daily.2 Furthermore, cigarettes are the product most commonly used by tobacco users, including those who use one product and those who use multiple products.2–4

Tobacco products have been conceptualized as falling along a continuum of risk,5,6 with cigarettes on the most harmful end of the continuum considering exposure to harmful chemicals multiplied by vast number of users.7 Although cigarette smoking prevalence has decreased over the past decades,8–10 the resulting public health benefit may be tempered by evolving patterns of cigarette use, including increases in nondaily cigarette smoking,10 and disparities in cigarette smoking prevalence based on race/ethnicity,11,12 socioeconomic status,13,14 sexual orientation and/or gender identity.15,16

Polytobacco use, or use of more than one tobacco product, is increasing10 and is associated with continued cigarette smoking behavior and nicotine dependence among youth and adults.17–19 Among youth and adults, approximately 40% of tobacco users use multiple tobacco products,2 with cigarette polytobacco use (using cigarettes plus at least one other product) consistently included in the top combinations of products.2,4,20–22 Among adult smokers, 16.3% smoked cigarettes with at least one other tobacco product,23 while among young adult smokers, 22.6% were polytobacco users23 and among youth cigarette smokers in grades 6–12, 46.1% smoked cigarettes and also used one or more other tobacco products.24

The current study draws from the longitudinal cohort design of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study and examines pathways of cigarette use in the U.S. across three waves from 2013–2016. We first provide overall cross-sectional weighted estimates of ever, past 12-month (P12M), past 30-day (P30D), and daily P30D use for U.S. youth (ages 12–17), young adults (ages 18–24), and adults ages 25 and older (adults 25+) from 2013–2016. Using the first three waves of longitudinal within-person data from the PATH Study, the second aim is to examine whether the known age group differences in tobacco use discussed above are found among the pathways of persistent use, discontinued use, and reuptake of cigarettes among Wave 1 (W1) P30D cigarette users. The focus is on P30D use to provide a broad overview of the transitions in cigarette use. Aim 3 is to compare longitudinal transitions of use among W1 exclusive cigarette smokers and W1 cigarette smokers who use multiple tobacco products (cigarette polytobacco use) to understand broad transitions such as tobacco cessation, tobacco reuptake, persistent cigarette use, discontinued cigarette use, and switching to another tobacco product. Monitoring these longitudinal transitions among cigarette smokers separately for exclusive and polytobacco users will advance our understanding of critical product transitions, improving comprehension of the health risks associated with cigarette smoking at the population level. The important topic of initiation of cigarette use is addressed in another paper in this supplement issue.25

METHODS

Study Design and Population

The PATH Study is an ongoing, nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of youth (ages 12–17) and adults (ages 18 or older) in the U.S. Self-reported data were collected using audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) administered in English and Spanish. Further details regarding the PATH Study design and W1 methods are published elsewhere.26,27 At W1, the weighted response rate for the household screener was 54.0%. Among screened households, the overall weighted response rate was 78.4% for youth and 74.0% for adults at W1, 87.3% for youth and 83.2% for adults at Wave 2 (W2), and 83.3% for youth and 78.4% for adults at Wave 3 (W3). Details on interview procedures, questionnaires, sampling, weighting and adjustments for non-response, and information on accessing the data are available at https://doi.org/10.3886/Series606. The study was conducted by Westat and approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board. All participants ages 18 and older provided informed consent, with youth participants ages 12 to 17 providing assent while their parent/legal guardian provided consent.

The current study reports cross-sectional estimates from 13,651 youth and 32,320 adults who participated in W1 (data collected September 12, 2013 through December 14, 2014), 12,172 youth and 28,362 adults at W2 (October 23, 2014 through October 30, 2015), and 11,814 youth and 28,148 adults at W3 (October 19, 2015 to October 23, 2016). The differences in the number of completed interviews between W1, W2, and W3 reflect attrition due to nonresponse, mortality, and other factors, as well as youth who enrolled in the study at W2 or W3.26 We also report longitudinal estimates from W1 youth (N = 11,046), W1 young adults (N = 6,478), and W1 adults 25+ (N = 17,188) with data collected at all three waves. See Supplemental Figure 1 for a detailed description of the analytic sample for longitudinal analysis.

Measures

Tobacco use

At each wave, adults and youth were asked about their tobacco use behaviors for cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems including e-cigarettes, traditional cigars, cigarillos, filtered cigars, pipe tobacco, hookah, snus pouches, other smokeless tobacco, and dissolvable tobacco. Participants were asked about P30D use of “e-cigarettes” at W1 and W2 and “e-products” (e- cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, and e-hookah) at W3; all electronic products noted above are referred to as ENDS. In addition, youth were asked about their use of bidis and kreteks. However, use of bidis, kreteks, and dissolvable tobacco were not included in the analyses due to small sample sizes.

Outcome measures

Cross-sectional definitions of use included ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D use. Longitudinal outcomes included persistent cigarette use, discontinued cigarette use, and reuptake of cigarette use, as well as transitions among exclusive and polytobacco cigarette users. The definition of each outcome is included in the footnote of the table/figure in which it is presented.

Analytic Approach

To address Aim 1, weighted cross-sectional prevalence of cigarette use was estimated across ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D use at each wave stratified by age. For Aim 2, irrespective of other tobacco product use, longitudinal W1-W2-W3 transitions in P30D cigarette use were summarized to represent pathways of persistent any P30D cigarette use (defined as continued exclusive or polytobacco cigarette use at W2 and W3), discontinued any P30D cigarette use (stopped cigarette use at W2 and W3 or just W3), and reuptake of any P30D cigarette use (used cigarettes at W1, discontinued cigarette use at W2, and used cigarettes again at W3). Finally, to address Aim 3, longitudinal W1-W2-W3 cigarette use pathways that flow through five mutually exclusive and exhaustive transition categories were examined for W1 P30D exclusive cigarette use, and W1 P30D cigarette polytobacco use (see Supplemental Figure 2). These pathways represent building blocks that may be aggregated to reflect higher-level behavioral transitions, such as discontinued tobacco use, tobacco use reuptake, persistent use, transition to exclusive or polytobacco use, exclusive use reuptake, switching product use, and inconsistent use. For each aim, weighted t-tests were conducted on differences in proportions to assess statistical significance. To correct for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used where relevant.

Cross-sectional estimates (Aim 1) were calculated using the PATH Study cross-sectional weights for W1 and single-wave (pseudo-cross-sectional) weights for W2 and W3. The weighting procedures adjusted for complex study design characteristics and nonresponse. Combined with the use of a probability sample, the weighted data allow these estimates to be representative of the noninstitutionalized, civilian, resident U.S. population aged 12 or older at the time of each wave. Longitudinal estimates (Aims 2 and 3) were calculated using the PATH Study W3 all-waves weights. These weighted estimates are representative of the resident U.S. population aged 12 and older at the time of W3 (other than those who were incarcerated) who were in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population at W1.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Survey Procedures, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Variances were estimated using the balanced repeated replication (BRR) method28 with Fay’s adjustment set to 0.3 to increase estimate stability.29 Analyses were run on the W1-W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8). Estimates with low precision (those based on fewer than 50 observations in the denominator or with a relative standard error greater than 0.30) were flagged and are not discussed in the Results. Respondents missing a response to a composite variable (e.g., ever, P30D) were treated as missing; missing data were handled with listwise deletion.

RESULTS

Cross-Sectional Weighted Prevalence

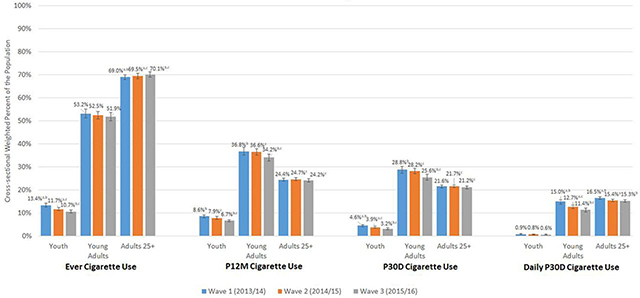

As shown in Figure 1, for youth, there were statistically significant decreases in prevalence of ever use of cigarettes at every wave from 13.4% (95% CI: 12.6–14.3) at W1 to 11.7% (95% CI 11.0–12.3) at W2 to 10.7% (95% CI: 10.0–11.4) at W3. For adults 25+, there are small increases in prevalence of ever use across waves that are statistically significant: ever use increased from 69.0% (95% CI: 67.9–70.1) in W1, to 69.5% (95% CI: 68.3–70.7) in W2, to 70.1% (95% CI: 68.9–71.3) in W3. For P12M cigarette use, among youth there was a decline between W1 (8.6% [95% CI: 8.0–9.3]) and W3 (6.7% [95% CI: 6.3–7.2]). Similarly, among young adults, there was a decline between W1 (36.8% [95% CI: 35.2–38.5]) and W3 (34.2% [95% CI: 32.7–35.6]). For adults 25+, there was a statistically significant decline between W2 (24.7% [95% CI: 24.1–25.4]) and W3 (24.2% [95% CI: 23.4–24.9]). Prevalence of P30D cigarette use decreased among youth between W1 (4.6% [95% CI: 4.2–5.0]) and W3 (3.2% [95% CI: 2.8–3.6]), and among young adults P30D cigarette use decreased between W2 (28.2% [95% CI: 27.0–29.4]) and W3 (25.6% [95% CI: 24.3–26.9]). Among adults 25+, P30D cigarette use decreased slightly between W2 and W3, from 21.7% (95% CI: 21.1–22.3) at W2 to 21.2% (95% CI: 20.5–21.8) at W3. Across all three waves, less than 1% of youth smoked cigarettes every day in the past 30 days. Among young adults, daily use of cigarettes in the past 30 days decreased between W1 (15.0% [95% CI:14.0–15.9]) and W2 (12.7% [95% CI: 11.9–13.5]) and W3 (11.4% [95% CI: 10.5–12.3]). Among adults 25+, daily use declined between W1 (16.5% [95% CI: 16.0–17.1]) and W2 (15.4% [95% CI: 14.9–16.0]) and remained about the same at W3.

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional weighted percent of ever, P12M, P30D and daily P30D cigarette use among youth, young adults and adults 25+ in W1, W2 and W3 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Abbreviations: P12M = past 12-month; P30D = past 30-day; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3 W1/W2/W3 ever cigarette use unweighted Ns: youth (ages 12-17) = 1,838/1,428/1,220; young adults (ages 18–24) = 5,963/4,853/4,580; adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) = 19,213/16,790/16,305 W1/W2/W3 P12M cigarette use unweighted Ns: youth = 1,170/965/757; young adults = 4,392/3,564/3,202; adults 25+ = 11,538/9,927/9,267 W1/W2/W3 P30D cigarette use unweighted Ns: youth = 634/481/366; young adults = 3,593/2,799/2,456; adults 25+ = 10,624/8,880/8,275 W1/W2/W3 daily P30D cigarette use unweighted Ns: youth = 127/96/73; young adults = 1,931/1,338/1,138; adults 25+ = 8,236/6,596/6,229 X-axis shows four categories of cigarette use (ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D). Y-axis shows weighted percentages of W1, W2, and W3 users. Sample analyzed includes all W1, W2, and W3 respondents at each wave. All respondents with data at one wave are included in the sample for that wave’s estimate and do not need to have complete data at all three waves. The PATH Study cross-sectional (W1) or single-wave weights (W2 and W3) were used to calculate estimates at each wave. W1-W3 ever cigarette use is defined as having smoked cigarettes, even once or twice in lifetime. W1-W3 P12M cigarette use is defined as any cigarette use within the past 12 months. W1-W3 P30D cigarette use is defined as any cigarette use within the past 30 days. W1-W3 daily P30D cigarette use is defined as cigarette use every day within the past 30 days. All use definitions refer to any use that includes exclusive or polytobacco use of cigarettes. a denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 and W2 b denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 and W3 c denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W2 and W3 The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Longitudinal Weighted W1-W2-W3 Pathways

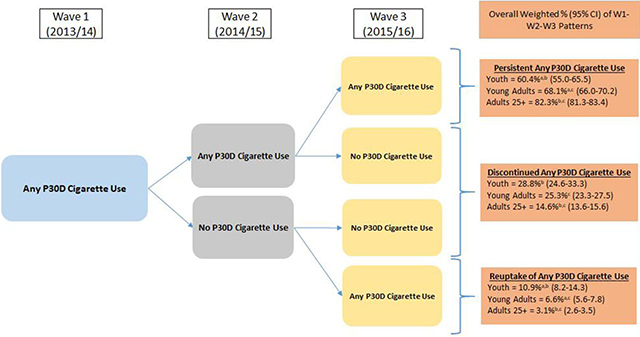

To address Aim 2, Figure 2 illustrates the potential longitudinal pathways among those who smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days at W1.

Figure 2.

Patterns of W1–W2–W3 persistent any P30D cigarette use, discontinued any P30D cigarette use and reuptake of any P30D cigarette use among W1 any P30D cigarette users. Abbreviations: W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3; P30D = past 30-day; CI = confidence interval W1 any P30D cigarette use weighted percentages (95% CI) out of total U.S. population: youth (ages 12–17) = 4.5% (4.1–5.0); young adults (ages 18–24) = 28.3% (26.8–29.7); adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) = 21.3% (20.7–22.0) Analysis included W1 youth, young adults, and adults 25+ P30D cigarette users with data at all three waves. Respondent age was calculated based on age at W1. W3 longitudinal (all-waves) weights were used to calculate estimates. These rates vary slightly from those reported in Figure 1 or Supplemental Table 1 because this analytic sample in Figure 2 includes only those with data at each of the three waves to examine weighted longitudinal use and non-use pathways. Any P30D cigarette use was defined as any cigarette use within the past 30 days. Respondents could be missing data on other P30D tobacco product use and still be categorized into the following three groups: 1) Persistent any P30D cigarette use: Defined as exclusive or cigarette polytobacco use at W2 and W3. 2) Discontinued any P30D cigarette use: Defined as any noncigarette tobacco use or no tobacco use at either W2 and W3 or just W3. 3) Reuptake of any P30D cigarette use: Defined as discontinued any cigarette use at W2 and any cigarette use at W3. a denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between youth and young adults b denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between youth and adults 25+ c denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between young adults and adults 25+ The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% CIs. Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Among P30D cigarette users at W1

Among those with data from all waves (W1, W2, and W3), 4.5% (95% CI: 4.1–5.0) of youth, 28.3% (95% CI: 26.8–29.7) of young adults, and 21.3% (95% CI: 20.7–22.0) of adults 25+ were P30D cigarette users at W1. Persistent P30D cigarette use, regardless of concurrent P30D use of other products, was found among 60.4% (95% CI: 55.0–65.5) of youth, 68.1% (95% CI: 66.0–70.2) of young adults, and 82.3% (95% CI: 81.3–83.4) of adults 25+, and the differences among all three age groups were statistically significant. Discontinued cigarette use occurred among 28.8% (95% CI: 24.6–33.3) of youth, 25.3% (95% CI: 23.3–27.5) of young adults, and 14.6% (95% CI: 13.6–15.6) of adults 25+; the differences between youth and adults 25+, and between young adults and adults 25+, were statistically significant. Reuptake of cigarette use occurred among 10.9% (95% CI: 8.2–14.3) of youth, 6.6% (95% CI: 5.6–7.8) of young adults, and 3.1% (95% CI: 2.6–3.5) of adults 25+ and the differences among all three age groups were statistically significant.

Among P30D exclusive cigarette users and P30D cigarette poly tobacco users at W1

As shown in the notes to Supplemental Figure 2, among adult 25+ W1 P30D cigarette users, the majority were exclusive cigarette users (62.6% [95% CI: 61.1–64.0]) compared to cigarette polytobacco users (37.4% [95% CI: 36.0–38.9]). In contrast, among W1 P30D youth and young adult cigarette users, more were cigarette polytobacco users (57.1% [95% CI: 52.1–61.9] of youth; 65.2% [95% CI: 63.0–67.4] of young adults). Only 42.9% (95% CI: 38.1–47.9) of youth and 34.8% (95% CI: 32.6–37.0) of young adult W1 P30D smokers were exclusive cigarette users. Aim 3 examined 25 possible W1-W2-W3 pathways across five mutually exclusive use categories (Supplemental Figure 2) among W1 exclusive cigarette users (Supplemental Table 1a) and W1 cigarette polytobacco users (Supplemental Table 1b). Described below are aggregated pathways from Supplemental Tables 1a and 1b that estimate broad behavioral transitions such as persistent use, tobacco cessation, and relapse in these two W1 user groups (Table 1).

Table 1:

Transitions in P30D Product Use at W2 and W3 Among W1 P30D Cigarette Users.

| Youth | Young Adults | Adults 25+ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 Exclusive Cigarette Use | W1 Cigarette PTU | W1 Exclusive Cigarette Use | W1 Cigarette PTU | W1 Exclusive Cigarette Use | W1 Cigarette PTU | |||||||

| Mutually Exclusive Pathways | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI |

|

Persistent cigarette use type at all waves Continuing the same W1 use type (exclusive or PTU) at each wave |

14.2a | (9.6–20.4) | 42.7a | (35.5–50.2) | 26.2a | (23.0–29.7) | 36.5a | (33.9–39.2) | 54.1a | (52.3–55.9) | 34.9a | (33.0–36.9) |

|

Cigarette use type reuptake The same use type (exclusive or PTU) at W1 and W3 (but a different tobacco use at W2) |

11.3 | (6.5–18.7) | 11.8 | (8.0–17.1) | 14.9a | (12.1–18.2) | 10.1a | (8.6–11.8) | 10.2 | (9.2–11.3) | 10.6 | (9.2–12.2) |

|

Cigarette use type transition Transition from W1 exclusive use to PTU by W3, or transition from W1 PTU to exclusive use by W3 (without discontinuing all tobacco use at W2) |

38.8a | (31.8–46.3) | 10.7a | (7.2–15.4) | 26.0 | (22.6–29.8) | 24.5 | (22.0–27.2) | 18.3a | (16.9–19.8) | 37.4a | (35.4–39.4) |

|

Switch or discontinue cigarette use, but continue other tobacco use W1 exclusive user who switches to another tobacco product by W3 or W1 polytobacco user that discontinues cigarette use by W3 but uses another tobacco product (without discontinuing all tobacco use at W2) |

4.7† | (2.1–10.0) | 6.9 | (4.2–11.0) | 5.0a | (3.5–7.0) | 10.5a | (8.9–12.4) | 1.7a | (1.3–2.3) | 7.3a | (6.3–8.5) |

|

Tobacco use reuptake W1 users who discontinue all tobacco use at W2 and use again at W3 |

11.5 | (7.7–16.8) | 8.2 | (5.3–12.6) | 7.2 | (5.3–9.7) | 4.9 | (3.7–6.4) | 2.8a | (2.3–3.4) | 1.9a | (1.4–2.5) |

|

Discontinue all tobacco use W1 users who discontinue all tobacco use at either W2 and W3 or just W3 |

19.5 | (14.1–26.4) | 19.8 | (14.8–26.0) | 20.7a | (17.3–24.6) | 13.4a | (11.6–15.5) | 12.9a | (11.7–14.2) | 7.9a | (7.0–9.1) |

Notes:

Abbreviations: P30D = past 30-day; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3; W1 = Wave 1; polytobacco use = PTU; CI = confidence interval; N/A = not applicable

Analysis included youth (ages 12–17), young adult (ages 18–24), and adult 25+ (ages 25 and older) W1 past 30-day cigarette users with data at all three waves. Respondent age was calculated based on age at W1. W3 longitudinal (all-waves) weights were used to calculate estimates. All tobacco use is defined as P30D use. Use type refers to exclusive use or PTU.

denotes significant difference at p<0.05 between W1 Exclusive Cigarette Use and W1 Cigarette PTU

The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% CIs.

Estimate should be interpreted with caution because it has low statistical precision. It is based on a denominator sample size of less than 50, or the coefficient of variation of the estimate or its complement is larger than 30%.

Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Among youth

As shown in Table 1, 14.2% (95% CI: 9.6–20.4) of W1 exclusive cigarette users persisted as exclusive users across all three waves, compared to 42.7% (95% CI: 35.5–50.2) of W1 cigarette polytobacco users who persisted as cigarette polytobacco users across all three waves. Complementing this finding, 38.8% (95% CI: 31.8–46.3) of W1 exclusive cigarette users transitioned to some form of polytobacco use by W3, in contrast to 10.7% (95% CI: 7.2–15.4) of W1 cigarette polytobacco users transitioning to exclusive cigarette use by W3.

Among young adults

As shown in Table 1, 26.2% (95% CI: 23.0-29.7) of W1 exclusive cigarette users persisted as exclusive users across all three waves, compared to 36.5% (95% CI: 33.9–39.2) of cigarette polytobacco users who persisted as cigarette polytobacco users across all three waves. In addition, there were differences in other pathways such as cigarette use type reuptake and switching or discontinuing cigarette use without quitting tobacco. For instance, 14.9% (95% CI: 12.1–18.2) of W1 exclusive cigarette users stopped exclusive cigarette use at W2 and took it up again at W3, without quitting tobacco entirely, compared to 10.1% (95% CI: 8.6–11.8) of W1 cigarette polytobacco users who stopped cigarette polytobacco use at W2 but took it up again at W3, without quitting tobacco entirely.

Additionally, while 5.0% (95% CI: 3.5–7.0) of W1 exclusive cigarette users discontinued cigarettes while still using tobacco, compared to 10.5% (95% CI: 8.9–12.4) of W1 cigarette polytobacco users who discontinued cigarettes while still using tobacco. Finally, 20.7% (95% CI: 17.3–24.6) of W1 exclusive cigarette users discontinued all tobacco use by Wave 3, compared to 13.4% (95% CI: 11.6–15.5) of W1 cigarette polytobacco users.

Among adults 25+

As shown in Table 1, 54.1% (95% CI: 52.3–55.9) of W1 exclusive cigarette users persisted as exclusive users across all three waves, compared to 34.9% (95% CI: 33.0–36.9) of W1 cigarette polytobacco users who persisted as cigarette polytobacco users across all three waves. Additionally, 18.3% (95% CI: 16.9–19.8) of W1 exclusive cigarette users transitioned from W1 exclusive use to polytobacco use by W3, compared to 37.4% (95% CI: 35.4–39.4) of W1 cigarette polytobacco users who transitioned to exclusive use by W3. Almost 13% (12.9% [95% CI: 11.7–14.2]) of W1 exclusive cigarette users discontinued all tobacco use by Wave 3, compared to 7.9% (95% CI: 7.0–9.1) of W1 cigarette polytobacco users.

DISCUSSION

Cigarettes are the most prevalent form of tobacco used in the U.S.2 as well as the most harmful tobacco product.7 This combination of higher prevalence and greater harm has significant implications for public health. In cross-sectional analyses based on data from 2013–2016 (W1- W3), prevalence of ever (only among youth), P12M and P30D cigarette smoking decreased among youth and young adults but remained relatively constant for adults 25+ (although statistically significant changes in adult 25+ ever, past 12M and P30D use were detected, they are of small magnitude and may not be meaningful). Likely of greater import for public health, there were statistically significant decreases in daily cigarette use among both young adults and adults 25+, with the largest decreases occurring between W1 and W2.

The observed decrease in youth cigarette smoking is consistent with other national surveillance studies,8 although the rates of P30D cigarette smoking in 2016 are slightly lower among youth in the PATH Study (5.5% among 15- to 17-year-olds; 1.0% among 12- to 14-year- olds), compared to those in the 2016 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) (8.0% in high school students; 2.2% in middle school students).8 This may be due to differences in the definition of youth, with high school students aged 18 and older included in the NYTS estimate but not in the PATH Study youth estimate, as well as different skip patterns in the data collection instruments. There is also evidence that household-based assessments of tobacco use prevalence, such as the PATH Study, tend to be lower than school-based assessments (e.g., NYTS).30

Across the 3 years observed in this paper, about 60% of youth W1 P30D cigarette smokers smoked cigarettes in P30D at all three waves, compared to almost 70% of young adults and 80% of adults 25+. Several other longitudinal studies have identified that cigarette smoking is persistent over even longer time periods.31–33 For example, over a 15-year period of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), almost 40% of established smokers continued to smoke cigarettes over time.17 In the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, 52.8% of baseline current smokers continued cigarette smoking over 25 years.34 Given ongoing changes in the U.S. tobacco market where an increasingly diverse mix of tobacco products including ENDS, cigars and smokeless tobacco products are available, the finding that cigarette use remains persistent highlights the continued importance of monitoring all tobacco products including cigarette.

Nevertheless, we also found that 15 to 30% of W1 P30D cigarette smokers discontinued cigarette use by W3, with youth having the highest rate of discontinuing cigarettes and adults 25+ having the lowest. Looking across the papers in this supplement issue, the P30D cigarette discontinuation rate was lower than that of other tobacco products,35–37 with the exception of smokeless tobacco.38 In contrast to their low P30D cigarette discontinuation rate, adults 25+ had higher rates of discontinuing ENDS and hookah, compared to youth and young adults.35–38

Among W1 P30D exclusive cigarette smokers, less than 15% of youth, a quarter of young adults, and more than half of adults 25+ used only cigarettes across all three waves without using another product. We also found that among W1 cigarette polytobacco users in all age groups, the most common transition among those examined was to continue cigarette polytobacco use at W2 and W3; the second most common transition for young adults and adults 25+ was a transition back to exclusive cigarette use by W3. This is consistent with studies that have found higher levels of nicotine dependence among polytobacco users, which might lead to continued cigarette use,39 and those that have found that cigarette use is persistent over time, as discussed above. The finding that both exclusive and polytobacco cigarette users tend to continue cigarette use further demonstrates the persistence of cigarette use and the pressing need to determine the most effective strategies to help users of all tobacco products including cigarettes quit tobacco.

Among youth, the pattern among cigarette polytobacco users was different. After persistent cigarette polytobacco use, the next most common transition among those examined was discontinued use of all tobacco, which likely reflects the more episodic, less stable pattern of youth tobacco use.40 However, there are also patterns of youth reuptake of cigarette polytobacco use and transition to exclusive cigarette use, which may indicate that among those youth who continue using tobacco, cigarette use also persists.

Finally, we found that the frequency of transitioning to cigarette polytobacco use among W1 exclusive cigarette smokers differed among age groups. While almost 40% of youth transitioned from exclusive to cigarette polytobacco use by W3, only 26% of young adults and 18% of adults 25+ followed this pathway. In contrast, transitions from W1 cigarette polytobacco use to exclusive cigarette use at W3 occurred in only about a third of adults 25+, a quarter of young adults, and about 10% of youth. These findings suggest that, compared to adults, youth may be more vulnerable to polytobacco use, which may be due to the appeal of other tobacco products like flavored products and products that are perceived as low risk like ENDS.41 In addition, it is also not clear if youth use of tobacco products is mere experimentation or if these patterns are indicative of future long-term use. This report is a resource that provides building blocks to aggregate different pathways to explore a variety of research questions regarding cigarette use.

Limitations

This study relies on self-reported data, which is subject to recall bias. In addition, discontinued use was defined as no P30D use, without any consideration of intent to quit or duration of cessation, which may have overestimated rates of discontinued use. This study also did not examine transitions in frequency of use, especially transitions to daily use, which may be important to understanding overall patterns of transition. Future studies are needed to examine correlates that predict patterns of transition among exclusive and polytobacco users. Within this journal supplement, Kasza et al.42,43 and Edwards et al.44 examine demographic correlates of initiation, cessation, and relapse of cigarette use to further explore predictors of these behavioral outcomes.

Summary and Implications

The persistence of cigarette use among all types of cigarette users (exclusive cigarette users and cigarette polytobacco users) is of particular public health concern since cigarettes have been identified as the most harmful tobacco product. Policy efforts that focus on the continuum of risk, such as the Food and Drug Administration’s comprehensive plan for tobacco and nicotine, which is aimed at reducing the harmful effects of tobacco, need to consider a continued focus on cigarettes in addition to new and emerging products such as ENDS.

Supplementary Material

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

This study adds a three-wave examination of cigarette use rates in the U.S. across multiple definitions of use for youth, young adults, and adults 25+. Across all three waves, young adults have the highest prevalence rates of P12M and P30D use, compared to youth and adults 25+.

Longitudinal pathways indicate that cigarette use is persistent over time, with more than 80% of W1 P30D adult 25+ cigarette smokers, almost 70% of W1 P30D young adult cigarette smokers, and about 60% of W1 P30D youth cigarette smokers using cigarettes at all three waves. Since cigarettes have been identified as the most harmful tobacco product on the continuum of risk, persistent use of cigarettes is a risk to public health.

Consistent with the finding that the majority of W1 P30D cigarette smokers continued to smoke, 15 to 30% of P30D smokers discontinued cigarette use between W1 and W3, with youth having the highest rate of discontinuation and adults 25+ the lowest.

While almost 40% of youth cigarette users transitioned from exclusive cigarette use at W1 to cigarette polytobacco use by W3, only 26% of young adults and 18.3% of adults 25+ followed this pathway. Transitions from W1 cigarette polytobacco use to exclusive cigarette use at W3 occurred in only about 10% of youth, a quarter of young adults, and about a third of adults 25+. These finding suggests that youth may be more likely to be cigarette polytobacco users, compared to adults 25+.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This manuscript is supported with Federal funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Center for Tobacco Products, Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, under a contract to Westat (Contract No. HHSN271201100027C).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Financial disclosure: Wilson Compton reports long-term stock holdings in General Electric Company, 3M Company, and Pfizer Incorporated, unrelated to this manuscript. No financial disclosures were reported by the other authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soneji S, Sargent J, Tanski S. Multiple tobacco product use among US adolescents and young adults. Tobacco control 2016;25(2):174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Toukhy S, Choi K. A risk-continuum categorization of product use among us youth tobacco users. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2016;18(7):1596–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FDA announces comprehensive regulatory plan to shift trajectory of tobacco-related disease, death [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; July 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeller M, Holman MR, Crosby K. FDA’S Center For Tobacco Products: An Update on Regulatory Activities and Priorities. Paper presented at: SRNT 2018; Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu S, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students- United States, 2011–2016. MMWRMorbMortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(23):597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014:943. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamal A Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahende JW, Malarcher AM, Teplinskaya A, Asman KJ. Quit attempt correlates among smokers by race/ethnicity. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2011;8(10):3871–3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martell B, Garrett B, Caraballo R. Disparities in Adult Cigarette Smoking-United States, 2002–2005 and 2010–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(30):753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid JL, Hammond D, Boudreau C, Fong GT, Siahpush M, Collaboration I. Socioeconomic disparities in quit intentions, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among smokers in four western countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(suppl_1):S20–lS33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JE, Tsoh JY. Cigarette Smoking Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Young Adults in Association With Food Insecurity and Other Factors. Preventing chronic disease. 2016;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchting FO, Emory KT, Kim Y, Fagan P, Vera LE, Emery S. Transgender use of cigarettes, cigars, and e-cigarettes in a national study. American journal of preventive medicine. 2017;53(1):e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews AK, Cesario J, Ruiz R, Ross N, King A. A Qualitative Study of the Barriers to and Facilitators of Smoking Cessation Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Smokers Who Are Interested in Quitting. LGBT health. 2017;4(1):24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutra LM, Glantz SA, Lisha NE, Song AV. Beyond experimentation: Five trajectories of cigarette smoking in a longitudinal sample of youth. PloS one. 2017;12(2):e0171808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein EG, Bernat DH, Lenk KM, Forster JL. Nondaily smoking patterns in young adulthood. Addictive behaviors. 2013;38(7):2267–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saddleson M, Kozlowski L, Giovino G, Homish G, Mahoney M, Goniewicz M. Assessing 30-day quantity-frequency of US adolescent cigarette smoking as a predictor of adult smoking 14 years later. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2016;162:92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Youth tobacco product use in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Gara E, Sharma E, Boyle RG, Taylor KA. Exploring Exclusive and Poly-tobacco Use among Adult Cigarette Smokers in Minnesota. American journal of health behavior. 2017;41(1):84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrell PT, Naqvi SMH, Plunk AD, Ji M, Martins SS. Patterns of youth tobacco and polytobacco usage: The shift to alternative tobacco products. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2017;43(6):694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bombard JM, Pederson LL, Nelson DE, Malarcher AM. Are smokers only using cigarettes? Exploring current polytobacco use among an adult population. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32(10):2411–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bombard JM, Rock VJ, Pederson LL, Asman KJ. Monitoring polytobacco use among adolescents: do cigarette smokers use other forms of tobacco? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(11):1581–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanton CA, Sharma E, Seaman EL, et al. Initiation of any tobacco and five tobacco products across 3 years among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s178–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tobacco Control. 2016:tobaccocontrol-2016–052934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tourangeau R, Yan T, Sun H, Hyland A, Stanton CA. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) reliability and validity study: selected reliability and validity estimates. Tobacco control. 2018:tobaccocontrol-2018–054561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy PJ. Pseudoreplication: further evaluation and applications of the balanced half-sample technique. 1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Judkins DR. Fay’s method for variance estimation. Journal of Official Statistics. 1990;6(3):223. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. Journal of adolescent health. 2003;33(6):436–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Augustson EM, Marcus SE. Use of the current population survey to characterize subpopulations of continued smokers: a national perspective on the “hardcore” smoker phenomenon. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(4):621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emery S, Gilpin EA, Ake C, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Characterizing and identifying” hard-core” smokers: implications for further reducing smoking prevalence. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(3):387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorg A, Xu J, Doppalapudi SB, Shelton S, Harris JK. Hardcore smokers in a challenging tobacco control environment: the case of Missouri. Tobacco control. 2011:tc. 2010.039743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caraballo RS, Kruger J, Asman K, et al. Relapse among cigarette smokers: the CARDIA longitudinal study-1985–2011. Addic tBehav. 2014;39(1):101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanton CA, Sharma E, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal transitions of exclusive and polytobacco electronic nicotine delivery systems (ends) use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma E, Bansal-Travers M, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco hookah use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s155–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards KC, Sharma E, Halenar MJ, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco cigar use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma E, Edwards KC, Halenar MJ, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco smokeless use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strong DR, Pearson J, Ehlke S, et al. Indicators of dependence for different types of tobacco product users: Descriptive findings from Wave 1 (2013–2014) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2017;178:257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orpinas P, Lacy B, Nahapetyan L, Dube SR, Song X. Cigarette smoking trajectories from sixth to twelfth grade: associated substance use and high school dropout. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;18(2):156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mermelstein RJ. Adapting to a changing tobacco landscape: Research implications for understanding and reducing youth tobacco use. American journal of preventive medicine. 2014;47(2):S87–S89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasza K, Edwards KC, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product initiation among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kasza K, Edwards KC, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product cessation among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s203–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edwards KC, Kasza K, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product relapse among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s216–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.