Abstract

Introduction

Meningiomas are the most common primary intracranial tumor. Recent next generation sequencing analyses have elaborated the molecular drivers of this disease. We aimed to identify and characterize novel fusion genes in meningiomas.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of our RNA sequencing data of 145 primary meningioma from 140 patients to detect fusion genes. Semi-quantitative rt-PCR was performed to confirm transcription of the fusion genes in the original tumors. Whole exome sequencing was performed to identify copy number variations within each tumor sample. Comparative RNA seq analysis was performed to assess the clonality of the fusion constructs within the tumor.

Results

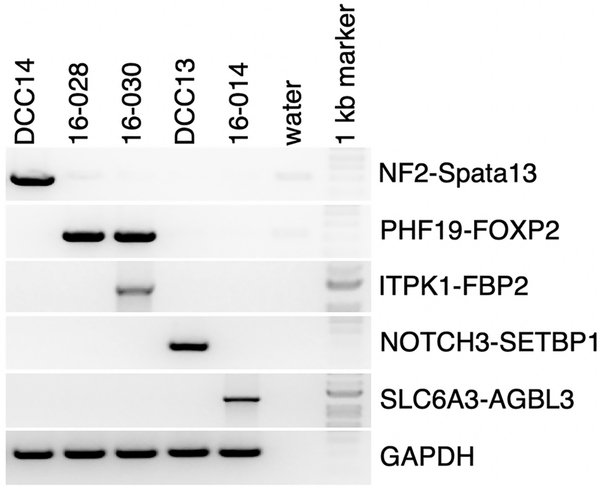

We detected six fusion events (NOTCH3-SETBP1, NF2-SPATA13, SLC6A3-AGBL3, PHF19-FOXP2 in two patients, and ITPK1-FBP2) in five out of 145 tumor samples. All but one event (NF2-SPATA13) led to extremely short reading frames, making these events de facto null alleles. Three of the five patients had a history of childhood radiation. Four out of six fusion events were detected in expression type C tumors, which represent the most aggressive meningioma. We validated the presence of the RNA transcripts in the tumor tissue by semi-quantitative RT PCR. All but the two PHF19-FOXP2 fusions demonstrated high degrees of clonality.

Conclusions

Fusion genes occur infrequently in meningiomas and are more likely to be found in tumors with greater degree of genomic instability (expression type C) or in patients with history of cranial irradiation.

Keywords: Meningioma, Fusion Gene, NF2, RNA Sequencing

Introduction

Meningiomas are the most common primary intracranial tumor, accounting for nearly one-third of all CNS tumors [1, 2]. While most are benign and effectively treated by surgery or radiosurgery, approximately 20% behave aggressively [3, 4]. Currently the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies these tumors as benign (grade I), atypical (grade II), and malignant (grade III) [5].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques have delineated the molecular underpinnings of meningiomas and helped differentiate benign from aggressive disease [6]. These studies have identified large scale copy number variations, recurrent mutations, methylation changes, and transcriptional changes involved in meningioma biology [7–9]. Biallelic NF2 loss, which can occur via chromosome 22q (chr22q) loss, inactivating NF2 mutation, or NF2 promotor methylation, is important in both benign and aggressive meningiomas [6]. Studies of benign meningiomas have identified recurrent mutations in TNF receptor-associated factor 7 (TRAF7), Krupple-like factor 4 (KLF4), v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (AKT1), smoothened, frizzled family receptor (SMO), and RNA polymerase II subunit A (POLR2A) genes [6, 10–12]. High-grade meningiomas are largely characterized by NF2 loss and widespread chromosomal instability [6]. Recently, using transcriptional profiling, we found that meningiomas cluster into three types, A, B, and C. These clusters are characterized by progressively worsening clinical course [6, 8]. Type A tumors consist entirely of WHO grade I tumors, without chromosomal losses or gains. Type B tumors are 80% WHO grade I and 20% WHO grade II and exhibit loss of PRC2 mediated gene repression as well as isolated chr22q/NF2 loss. The PRC2 complex silences target gene expression by histone H3K27M di- and trimethylation. 60% of Type C tumors are WHO grade I, while 40% are WHO grade II/III. This is the most aggressive category. These tumors are characterized by combined loss of chr22q/NF2 and chr1p and demonstrate a high degree of genomic instability. Type C tumors are additionally characterized by loss of the cell cycle regulating DREAM complex.

Whole-genome (WGS) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) have allowed for detection of fusion genes resulting from chromosomal translocations. Fusion events can result in a novel functional protein, gene inactivation, or gene deletion[13]. While fusion genes play crucial roles in other CNS tumors, such as the C11orf95-RELA fusion, which has been found to activate oncogenic nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) in ependymomas, only a handful of fusion genes have been identified in meningiomas [14]. Most notably, inactivating NF2 fusion genes coupled with chr22q loss have been reported in a subset of radiation-induced meningiomas [14, 15]. Additionally, some recurrent non-NF2 gene fusions have been reported in histologic grade I meningiomas [7]. Identification of fusion events, even if infrequent, may help identify factors driving meningioma development and growth.

Here, we performed a secondary analysis of the RNA-sequencing of our cohort of 145 meningiomas for fusion events [8]. We detected six fusion events in a total of five tumor samples with one tumor harboring two fusions and one fusion found in two tumors from separate patients.

Methods

Patient Selection and Tumor Analysis

We analyzed 145 primary (not recurrent) meningiomas from 140 patients using RNA-seq from our prior cohort of 160 primary and recurrent tumors as previously described and reported [8]. All patients provided written informed consent. Tumor tissues were collected under an IRB approved protocol. Clinical and demographic information was reviewed by searching electronic medical record. All data is publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession no. GSE136661).

Gene Fusion Detection

Fusion events were detected by deFuse (RRID:SCR_003279) with default settings. BLAT (RRID:SCR_011919) was then used to assess the unique mapping of the junction read; fusion junctions mapped to multiple genome locations were filtered out. Each fusion event was visualized in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (RRID:SCR_011793). High confidence fusion transcripts were selected for validation using the following criteria: 1) consist of an open reading frame; 2) have a probability score of >= 0.9; 3) are inter-chromosome fusions; and have no read through.

Gene fusion validation

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific) from 5 mg of fresh-frozen tumor samples according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. RNA was quantified with the Nanodrop ND1000 (ThermoFisher Scientific) and 5 μg was used in a 20 μl reaction using 200 U M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific) and 100 ng Random Hexamers (ThermoFisher Scientific) for reverse transcription at 30°C for 60 minutes. Each fusion gene was amplified using 200 ng cDNA in a 20 μl reaction using EconoTaq Master Mix (Lucigenn, Middleton, WI) with the following PCR protocol: 2 min at 95°C; 35 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 60°C and 30 sec at 72°C and a final elongation of 10 min at 72°C. Primers used were as follows: ITPK1-FBP2_F 5’-CGATTTCCTCCGGACCCAG-3’, ITPK1-FBP2_R 5’-TGTGGGGTCAAACTCGCTAG-3’ (505 nts amplicon; NF2-SPATA13_F 5’-TGGCCCAAGAGGAATTGCTT-3’, NF2-SPATA13_R 5’-CCGTAGTCAGAGAATGGCCG-3’(310 nts); NOTCH3-SETBP1_F 5’-GACCGCGTGGCTTCTTTCTA-3’, NOTCH3-SETBP1_R 5’-GGGGGCATGAGAAGCACAT-3’ (194 nts); PHF19-FOXP2_F 5’-GGTGCTGTCCTACCAGCCCGAGG-3’, PHF19-FOXP2_R 5’-GAGCTGGTGTCACCACTTGA-3’ (224 nts); SLC6A3-AGBL3_F 5’-GGCTTCACGGTCATCCTCAT-3’, SLC6A3-AGBL3_R 5’-TTTCCAATGACCTGTGGGGC-3’ (365 nts); GAPDH_F 5’-GGATTTGGTCGTATTGGG-3’, GAPDH_R 5’-GGAAGATGGTGATGGGATT-3’ (224 nts).

Assessment of Clonality

We are focusing on expression-based clonality of the fusion transcripts because the fusion may take place RNA level by readthrough events by trans-splicing. To estimate the RNA level clonality, we divided each gene into two parts such that, for each gene, the breakpoint separates the gene into left and right sides. We hypothesized that the discordance of the average RNA-seq signal on left and right sides of each gene can be used to estimate the expression level clonality. Based on this, we compute the total RNA-seq on each side of the breakpoint, for each gene. One side of each gene contained significantly lower amount of RNA-seq signal, because of the fusion event, than the other (Figure 3). We counted the number of reads mapping on each side of the breakpoint for each gene using samtools [16]. We then estimated the chimeric transcript signal and the total transcript signal (Figure 3) and finally computed the expression clonality. Table in Figure 3 shows the estimated expression clonality levels. Although the discordance between left and right sides of the breakpoint may be stemming from the 3’ biases in mRNA sequencing, the clonality estimates are strikingly high for them to be stemming from the 3’ biases. We also performed visual check on the discordance for each fusion event to confirm the discordance.

Fig 3. Assessment of clonality.

Approximation of clonality from comparative RNA-seq analysis. A. Illustration of the RNA-seq signal in one of the fused genes, denoted by Gene 1. The breakpoint is shown with dashed arrows. Left side (or 5’ end) of the gene denotes the portion of the gene lost to fusion and contains much lower RNA-seq signal than the right side (3’ end) of the gene. The right side contains the total of the wildtype and fused transcript signal whereas left side of the breakpoint contains the wildtype signal only. We use the signal on the left and right side to estimate the average fusion signal (numerator of the fraction) and normalize this with respect to the average wildtype and fusion signal (denominator). B. Illustration of the fusion and estimation of clonality for each gene. Gene1 and Gene2 are shown on genomic coordinates on top. In the middle row, the fusion transcript is illustrated. Left side of Gene 1 and right side of Gene 2 are fused in the fusion transcript. and represent the estimate of the wildytype+fusion signal on Gene 1 and Gene 2, respectively. These are computed as average total RNA-seq signal divided by the length of exons, e.g., (𝑙3 + 𝑙4) is the total length of the 2 exons for . Similarly, and represent the average signal on the fusion transcript. C. Table of results indicating the relative degree of clonality.

Results

Patient Selection and Clinical Characteristics

We analyzed 145 meningioma samples from 140 patients and found that they sorted to three transcriptional classes: Type A (N=58, 40% of cases, 100% WHO grade I), type B (N=40, 28%, 80%−20% WHO grade I-II, respectively), and type C (N=47, 32%, 60%−40% WHO grade I-II, respectively) [8]. Using deFuse, we evaluated the RNA-seq data to identify fusion events [17]. We found six fusion events in five primary tumors; one patient had two events and one fusion occurred in two patients. The clinical characteristics of these patients are described in Table 1. Three patients were female and two were male. Their median age was 48 years (range 42–70 years). Four patients underwent gross total resection, while one had a subtotal resection. Tumor size ranged from 0.8 to 4.5cm in maximum dimension. The median MIB1 (labeling index indicating presence of antibody against Ki-67, a protein expressed in proliferating cells) was 5.7% (range 3–40%). Four tumors were type C (80%) and one was type B (20%), thus 9% (4/47) of type C and 3% (1/40) of type B tumors had fusion genes. Tumor recurrence was seen in three patients with type C tumors at a median of 11 months (range 3–25 months). Three patients with fusion genes had a history of childhood radiation.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of tumors with fusion genes

| Tumor | Gender | Age | Race | History of radiation | Location | Tumor Size (SI x TV x AP) cm | Salient Radiographic Features | WHO Grade | Histologic type | MIB1 (%) | Fusion Gene | Transcriptomic Type | Gross Resection | Simpson Grade | Recurrence | Interval to Recurrence (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCC14 | F | 70 | White | Yes (tinea capitis) | Left occipital | 3.9x2.9x3.8 | Homogenously enhancing, distinct border, lobulated | 2 | Unknown | 40 | NF2- SPATA13 | C | GTR | 1 | Yes | 11 |

| DCC13 | F | 47 | Hispanic | No | Right intraventricular | 3.2 x 2.6 x 2.8 | Homogenously enhancing, diffusion restriction, round, indistinct medial border | 1 | Fibroblastic | 3 | NOTCH3- SETBP1 | C | GTR | 2 | No | NA |

| 16–028 | M | 49 | White | Yes (testicular cancer and leukemia) | Right tentorial | 2.2 x 4 x 3 (infra); 1.8 x 3.4 x 4.5 (supra) | Nonhomogenously enhancing, difusion restriction, T2 hyperintense, ill-defined borders | 1 | Fibroblastic | 8.5 | PHF19- FOXP2 | C | STR | 4 | Yes | 3 |

| 16–030 | M | 48 | White | No | Left frontal falcine | 4.8x3.8x5cm | Homogenously enhancing, distinct border | 1 | Unknown | 5.7 | PHF19- FOXP2; ITPK1- FBP2 | C | GTR | 1 | Yes | 25 |

| 16–014 | F | 42 | White | Yes (cerebellar astrocytoma) | Left cerebellar | 0.8 x 0.6 x 0.8 | Homogenously enhancing, indistinct border, lobulated | 1 | Fibroblastic | 4.5 | SLC6A3- AGBL3 | B | GTR | 1 | No | NA |

Abbreviations: SI - superoinferior, TV - transverse, AP - anteroposterior.

Four of the five tumors from which we found these novel fusion genes were type C meningiomas, notable for large-scale copy number variations (CNV) [8, 18]. The fusion genes we discovered were all inter-chromosomal fusions occurring between genes on separate, non-homologous chromosomes. We have summarized the CNV as derived from whole exome sequencing (WES) in Table 2. The four type C tumors had an average arm-level chromosome loss of 9 (range 7–13) and an average arm-level chromosome gain of 1.3 (range 0–4) whereas the single type B tumor showed only loss of chromosome 22q, and no copy number gains [8].

Table 2.

Copy number variation from each tumor sample

| Tumor | Chromosome loss | Chromosome Gain |

|---|---|---|

| 16–014 | 22q | None |

| DCC13 | 1p, 2p, 6q, 8p, 18q, 19p, 22q | None |

| DCC14 | 1p, 3p, 3q, 6p, 6q, 8p, 8q, 9p, 14p, 14q, 17p, 19p, 22q | 2q, 4p, 17q |

| 16–030 | 1p, 6q, 7p, 9p, 11p, 10q, 22q | 1q |

| 16–028 | Unknown | Unknown |

NF2-SPATA13 in a type C tumor

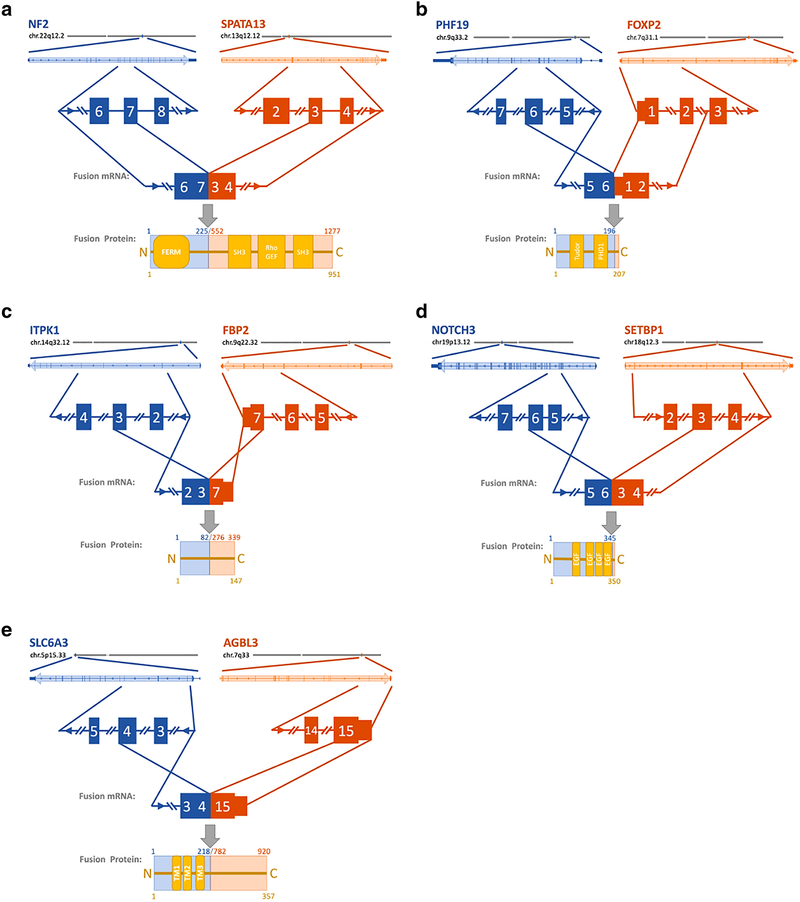

We identified the NF2-SPATA13 fusion in a left occipital meningioma in a 70-year-old woman with a history of childhood radiation for tinea capitis who subsequently developed multiple meningiomas. Despite gross total resection, her tumor recurred four times over a four-year period before the patient ultimately died of her disease. The original tumor was WHO grade II with a MIB1 of 40% (Table 1). Her recurrences had the following characteristics: MIB1 60% grade II, MIB1 60% grade III, MIB1 22.3% grade III, and MIB1 39% grade III. RNA sequencing of her tumors demonstrated that they were all expression type C meningiomas [8]. Her original tumor, as well as all recurrences, demonstrated characteristic loss of chr22q and chr1p, as well as widespread genomic instability (complete losses of chr3, chr6, chr8 and chr14; losses in chr9p, chr17p, and chr.19p; gains in chr.2q, chr4p and chr17q) (Table 2). The fusion event resulted in the splicing of exon seven of NF2 to exon three of SPATA13 causing the fusion of the NF2 FERM domain to the Rho guanylate exchange factor (GEF) domains of SPATA13 (Fig. 1C). The predicted 1277aa merlin hybrid protein is likely non-functional, as it has been reported that merlin function is impaired with a mutated or missing C-terminal domain [19]. The fusion transcript encodes the GEF domain of SPATA13 and functionality of the encoded protein product is unclear (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1. Fusion gene overview.

Location of the fusion gene event is depicted in a chromosomal arm level relative to the centromere. The primary gene is in blue shades while the fused gene is in orange shades. The genes are depicted in a close up and the exons in questions are highlighted in more detail. The fused mRNA is shown, and the predicted protein is depicted with protein domains in yellow. The corresponding protein positions are mentioned in respect to the original protein (upper) as well as the resulting fusion protein (yellow, lower). A. Demonstrating the NF2-SPATA13 fusion. B. The PHF19-FOXP2 fusion. C. The ITPK1-FBP2 fusion. D. The NOTCH3-SETBP1 fusion. E. The SLC6A3-AGBL3 fusion. Legend: FERM: Band 4.1 (F), Ezrin (E), Radixin (R), and Moesin (M) domain; SH3: SRC Homology 3 Domain; Rho/GEF: Rho / guanine nucleotide exchange factor domain; PHD1: prolyl hydroxylase domain 2; EGF: epidermal growth factor domain; TM1: transmembrane domain.

ITPK1-FBP2 in type C tumor

We identified an ITPK1-FBP2 fusion in a 48-year-old man with a left frontal falcine meningioma. Histopathologically, this tumor was WHO grade I with a MIB1 of 5.7% (Table 1). Despite gross total resection, the tumor recurred 25 months later. The recurrent tumor was also WHO grade I but had an increased MIB1 of 9.1%. Transcriptional profiling revealed that both tumors were type C. Consistent with this classification, the patient had loss of chr22q and chr1p, as well as additional losses in chr6q, chr7p, chr9p, chr10q, chr11p as well as amplification in chr1q (Table 2). The fusion event resulted in the splicing of exon three of ITPK1 to the last exon of FBP2, giving rise to a predicted 147aa short protein with no known functional protein domains, effectively a null allele for both genes (Fig. 1C).

PHF19-FOXP2 in two type C tumors

The aforementioned patient with an ITPK1-FBP2 fusion also had fusion of PHF19-FOXP2. This same fusion was also detected in a primary tumor from a second patient – a 49-year-old man with prior cranial irradiation for childhood leukemia and testicular cancer, who later developed multiple meningiomas. The patient underwent subtotal resection of his right tentorial meningioma, with residual adjacent to and within the transverse sinus. Pathology was consistent with WHO grade I tumor with a MIB1 of 8.5% and classified as a type C tumor by RNA-seq (Table 1). The patient had a rapid recurrence at three months post-resection. The recurrent tumor was also WHO grade I and expression type C, but had increased MIB1 of 20.9. The chromosomal rearrangements are unknown. The fusion event results in the splicing of exon six of PHF19 to the first exon of FOXP2. Due to an in-frame stop codon immediately after the splice site, the predicted protein is 207aa long and results in a null allele for FOXP2 (Fig. 1B). The transcript includes the PHF19 coding sequence for one of two PHD domains and the histone binding Tudor domain but lacks the c-terminal chromo domain necessary for binding to the PRC complex [20]. The predicted fusion protein is thus likely unable to facilitate interaction between the PRC complex and target histones, rendering this fusion a functional null allele for PHF19 (Fig. 1B).

NOTCH3-SETBP1 in type C tumor

We identified a NOTCH3-SETBP1 fusion event in an intraventricular meningioma from a 47-year-old woman. The patient underwent gross total resection and remains disease free after 78 months (Table 1). Histopathological analysis revealed she had a WHO grade I meningioma with a MIB1 of 3%. RNA-seq demonstrated this to be a type C meningioma. She had characteristic chr22q and chr1p loss in addition to loss of chr2p, chr6q, chr8p, chr18q and chr19p (Table 2). The fusion event combined of exon six of NOTCH3 to exon three of SETBP1. Due to a premature STOP codon, the encoded fusion protein has a predicted 350aa length. The near immediate STOP codon within the SETBP1 transcript leads to allelic loss of SETBP1 (Fig. 1D). The fusion transcript encodes four of the 34 extracellular epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains of NOTCH and lacks the signaling Notch intracellular domain (NICD) making it a functional null allele (Fig. 1D) [21].

SLC6A3-AGBL3 in type B tumor

We identified an SLC6A3-AGBL3 fusion in a left posterior fossa meningioma from a 42 year-old woman with childhood cranial irradiation for a posterior fossa astrocytoma. Gross total resection was achieved and the patient is without recurrence after 47 months. Pathology demonstrated a WHO grade I meningioma with a MIB1 of 4.5%. Unlike the other tumors with fusion events, this was a type B tumor based on transcriptional subtyping. The fusion joined exon four of SLC6A3 to the last exon of AGBL3. The predicted protein is 357 amino acids (aa) long and contains three of the 12 transmembrane SLC6A3 domains, leaving the unstructured 118aa of AGBL3 facing the extracellular space. This results in functional null alleles of both the AGBL3 protease and the SLC6A3 receptor (Fig. 1E).

Fusion gene confirmation and clonality analysis

To confirm that these genes are indeed transcribed and not an artifact of the WES, we performed semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2). We found that all of these genes were transcribed to mRNA with the expected sizes. No reciprocal fusion events were detected, and no patient had mutations of TRAF7, KLF4, AKT, SMARCB1, PIK3CA, SMO, or POLR2A.

Fig 2. Fusion event validation.

RNA of each patient was reversed transcribed, and subject to semi-quantitative PCR. GAPDH was used as positive control and each tumor served also as negative control for the other fusion events.

In addition, we sought to estimate the clonality of these fusion genes within the tumor by approximating the variant allele frequency (VAF) of the fusion genes. To do this, we compared the RNA-seq signal of the parent genes on either side of the breakpoint (Fig. 3A). The coverage of the RNA-seq signal of the portion of the parent gene that is lost to the fusion construct is lower as these reads will not map concordantly to the wildtype reference genome (Fig. 3A). If there are normal subclones, these will have wildtype transcripts whose reads will map normally on the reference. We use this to estimate the fraction of reads that are missing from the reference by comparing the average RNA-seq signal on the left and right side of the breakpoint. The missing signal is a measure of the clonality of the fused transcripts. The clonality is estimated for the two genes that are fused together (Fig. 3B). We found that most of the fusions show high clonality – potentially indicating that they are in the founding clones (Fig. 3C). Only the PHF19-FOXP2 fusions show low clonality, which suggests that this fusion may be subclonal, therefore arising later in the lifecycle of the tumor.

Discussion

In this study, we identified six fusion events in five tumor samples using the deFuse algorithm analyzing RNA-seq data from 145 meningiomas. Fusion genes have been reported in nearly all types of neoplasia, resulting in an estimated 20% of human cancer morbidity [22]. While certain types of neoplasia are defined by gene fusions, e.g. chronic myelogenous leukemia and solitary fibrous tumor, the incidence of fusion events in other tumors is much lower [23, 24]. Though infrequent, fusion events can still affect pathways critical to tumorigenesis. While there are multiple RNA-seq based algorithms developed to identify these events, validation must be performed in order to assure the RNA-seq detection/prediction of the transcripts is correct [25]. Synthesizing total cDNA from the tumor using random hexamer primers, along with semi-quantitative detection of the fusion gene, allowed us to assess several crucial fusion gene characteristics. There are several key steps necessary to ensure accuracy. First, taking out samples between different cycles during the PCR helps ensure that fusion product us detected within linear PCR range. Second, the semi-quantitative PCR yields one PCR product whose length can be compared to the predicted length of the fusion for confirmation. Third, Sanger sequencing of the PCR product can be performed to ensure that the fusion site matches what was predicted by RNA-seq. We Sanger sequenced all fusion PCR products, and their fusion site was correctly predicted. However, this method is not able to visualize the underlying interchromosomal rearrangement juxtaposing both genes. This can be achieved by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with two differently labeled probes. This was not performed in the current stury due to sample limitations.

Loss of gene function by fusion events

Fusion transcripts result from chromosomal aberrations: translocations, chromosomal inversions, and deletions. While the most notable fusion genes result in chimeric proteins with novel oncogenic functions, this is not always the case [23, 26, 27]. Alternatively, the fusion of a strong promotor to a proto-oncogene can result in the pathologic upregulation of the proto-oncogene. Lastly, a fusion event can result in allelic loss of a tumor suppressor, resulting in tumorigenesis [13].

Here we identify loss of two known tumor suppressors in meningioma, NF2 and PRC2 complex repression, by gene fusion [6]. NF2 is located on chromosome 22q and encodes merlin, a 69 kDa cytoskeleton scaffolding protein [28]. Merlin functions as a tumor suppressor by mediating contact inhibition of cell proliferation by downregulating pro-growth receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) as well as by inhibiting the Rac1-Pak1 pro-growth pathway [29, 30]. Additionally, merlin signaling leads to the cytosolic sequestration of the pro-growth transcription factor YAP, thereby inhibiting the Hippo pathway [31]. Merlin also suppresses the pro-growth signaling cascade of PI3K/AKT by binding PIKE-L [32]. NF2 loss is a key pathogenic factor in meningioma [6]. Loss of the tumor suppressor NF2 by gene fusion has been described in a subset of radiation induced meningiomas [15]. Similarly, we report an NF2-SPATA13 fusion effectively resulting in allelic loss of NF2. That patient also had chromosomal loss of chr22q, and thus biallelic loss of NF2.

Two different patients in our cohort had type C meningioma with fusion of the PHF19 and FOXP2 genes. PHF19 encodes the protein PHD Finger Protein 19 (Phf19) [20]. Phf19 binds to the PRC2 complex via its c-terminal chromo domain and to methylated histone H3 K36 via its Tudor domain thereby allowing the PRC2 mediated trimethylation of histone H3 [20]. The fusion gene we describe contains a truncated PHF19 presumably reducing PRC2 recruitment to mono-methylated histones. Harmanci et al. noted hypermethylation related to increased PRC2 activity in aggressive meningiomas [18]. In our previous transcriptional classification, type B tumors were characterized by loss of PRC2 gene repression [8]. It is clear that the PRC2 complex plays a critical role in meningioma biology and that further study is required to clarify its role in tumorigenesis [6, 8, 18, 33, 34].

Additionally, we discovered fusion constructs involving genes as yet undescribed in meningioma biology. One tumor with PHF19-FOXP2 fusion also contained an ITPK1-FBP2 fusion transcript. ITPK1 is located on chromosome 14q and encodes an inositol phosphate (IP) kinase capable of phosphorylating IP3 or IP4 [35]. As of yet, ITPK1 has not been strongly linked to any neoplastic process. FBP2 is located on chromosome 9q and encodes the enzyme Fructose-1–6-bispostatase 2 (FBP2), a key enzyme in gluconeogenesis. FBP2 serves as a tumor suppressor in gastric adenocarcinoma as well as sarcoma [36, 37]. Given the brevity of the fusion transcript, this results in allelic loss of both FBP2 and ITPK1. Neither of these genes have been previously implicated in meningioma biology.

One tumor harbored NOTCH3-SETBP1 fusion. NOTCH3, located on chromosome 19p, encodes the Notch-3 protein, which is characterized by a large extracellular domain of 30–36 EGF repeats, a single pass transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain [21, 38]. Upon binding of its ligand, Delta or Jagged, the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) is liberated and localizes to the nucleus where it promotes gene transcription by binding to CSL (CBF1, Suppressor of Hairless, Lag-1) proteins. Notch proteins play complex roles in tumor biology, in some cancer types acting as oncogenes and in others as tumor suppressors [39–42]. Deregulated Notch signaling has been implicated in meningioma [43], with induction of HES1, a downstream target of Notch2, in meningioma [44]. Meningioma cell lines with increased HES1 expression demonstrated increased rates of tetraploidy and chromosomal instability [45]. The fusion transcript in our study results in a severely truncated Notch-3 transcript, encoding only 4 of the 30–36 extracellular EGF repeats and none of the signaling NICD.

The SETBP1 gene is located on chromosome 18q21.1 and encodes the DNA-binding protein SET binding protein 1 [46]. The heterodimer of SET binding protein 1 and SET are thought to inhibit the tumor suppressor PP2A, thereby increasing the rate of cell proliferation [47]. Patients with myelomonocytic leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome who have SETBP1 mutations have poorer outcomes [47]. Our fusion gene likely represents a functional allelic loss of SETBP1 as there is a near-immediate stop-codon within the fusion transcript. One microarray study of meningiomas found SETBP1 to be a part of an “oncogenic functional module,” a set significantly differentially expressed genes that differentiate malignant from benign meningiomas [48].

One tumor in our cohort had an SLC6A3-AGBL3 fusion. SLC6A3, located on chromosome5p, is also known as DAT1; it encodes a dopamine-sodium symporter located on pre-synaptic nerve terminals [49]. DAT1 consists of 12 putative transmembrane domains [50]. In our fusion transcript, only the first three transmembrane domains are expressed. AGBL3 is a gene located on chromosome 7p and encodes the enzyme cytosolic carboxypeptidase 3 (CCP3) [51]. CCP3 is a metalloprotease that utilizes a zinc cofactor to catalyze the c-terminal deglutamylation and deaspartylation of various proteins [52]. These genes have also not previously been implicated in meningioma biology.

Genomic instability as mechanism for gene fusion in meningioma

Genomic instability is a key pathogenic factor in many neoplastic diseases, most commonly in the form of chromosomal instability, characterized by abnormal number and arrangement of chromosomes in cancer cells. In hereditary cancer syndromes, genomic instability is often related to mutation of “caretaker” genes that repair DNA damage. However, in sporadic cancer, oncogenes lead to DNA replication stress materializing most commonly at so-called common fragile sites [53]. It has been reported that large scale genomic changes, as opposed to increased burden of somatic mutations, are associated with more aggressive types of meningioma [6]. Multiple groups have shown a significantly higher number of copy number alterations in clinically aggressive meningioma [8, 18, 54]. That genomic instability results in chromosomal aberrations and subsequently the formation of fusion transcripts is corroborated by the fact that four of the five tumors in our cohort were type C tumors.

Viaene et al. found several fusion events and argued that these occurred mostly in grade I meningioma, which is in accordance with our data [7]. Of the fusion genes identified in their study, two novel fusion constructs (NF2-ZPBP2 and NF2-OXCT1) were found in higher grade or recurrent tumors. These fusions resulted in a truncated NF2 transcript, a key pathogenic event in meningioma tumorigenesis. The authors note that the function of the remaining fusion transcripts is unknown and that future analyses of their function will be necessary to understanding their role in progression to higher grades.

Only one of our five patients had an atypical (WHO grade II) meningioma while the remainder were WHO grade I tumors. However, four of our 5 patients had type C meningioma, characterized by genomic instability, a likely mechanism for development of fusion events. This highlights a limitation of the current histopathologic classification of meningiomas, as the tumors we describe here behave aggressively despite their grade I designation. In radiation induced meningiomas, NF2 fusion genes coincide with large scale chromosomal abnormalities, including frequent loss of both chr1p and chr22q, a marker for transcriptional type C tumors [15]. These findings indicate that fusion genes are more common in meningiomas with chromosomal instability, and that prior radiation is a key risk factor for fusion genes within meningiomas.

The estimation of VAF and clonality for fusions is not straightforward because the fusion may occur either at the DNA or RNA level [55]. The mechanisms for this are trans-splicing or read-through transcription of the adjacent genes [55]. Thus, identifying the number of fusion events at the DNA level may provide an incomplete estimate of the clonality since the expression levels of the fused transcripts may be different.

We therefore proceeded to assess clonality at the RNA expression level as described above. Interestingly, all but two fusion events (PHF19-FOXP2) were expressed in the majority of sequenced tumor cells suggesting that these fusion events occur early in tumorigenesis. Given the variety of fusion genes, it is unclear if these are driver events of tumorigenesis or byproduct markers that indicate the importance of genetic instability in the early tumorigenesis of aggressive meningioma.

Radiation therapy as a risk factor for fusion events

Three of the five patients that we identified with gene fusions had a history of childhood radiation. One of these radiation-induced meningiomas had a fusion between NF2 and SPATA13, effectively resulting in allelic loss of NF2. This is consistent with the findings of Agnihotri et al [15]. They characterized 31 radiation-induced meningiomas using multi-modal NGS, including RNA-seq and found 12 tumors with NF2 gene rearrangements. In our cohort, three of the five of the patients with identified gene fusions had radiation-induced tumors. From our data and others, it is evident that fusion events are more common in radiation-induced meningiomas than sporadic meningiomas [7, 8, 15]. Though the dose-related risk of cranial radiation exposure to the development of gene fusion events in meningioma remains unclear, a study of patients developing thyroid cancer after exposure to radiation from the Chernobyl disaster found a dose-response relationship between gene fusions and radiation exposure [56]. Further investigation is necessary to clarify this effect in meningiomas.

Table 3.

Literature summary of reported fusion genes in meningiomas

| Study | Tumor samples | Fusion genes present | Fusion gene | Number of individual events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viaene et al. (2019) | 38 | 9 | NF2-ZPBP2* | 1 |

| NF2-OXCT1* | 3 | |||

| C10orf112-PLXDC2 | 3 | |||

| GAB1-HHIP-AS1 | 1 | |||

| HHIP-AS1-GAB1 | 1 | |||

| KANSL1-ARL17A | 6 | |||

| MLLT3-CNTLN | 3 | |||

| RP11–444D3.1-SOX5 | 2 | |||

| SAMD5-SASH1 | 4 | |||

| Agnihotri et al. (2017) | 31 radiation-induced meningiomas (RIM); 30 sporadic meningiomas(SM) | 12 in RIMs; 0 in SM | NF2-MBD3 | 1 |

| NF2-NIPSNAP1 | 1 | |||

| NF2-DDX49** | 1 | |||

| NF2-PHF21A | 1 | |||

| NF2-PPIL2 | 1 | |||

| NF2-ARHGAP20 | 1 | |||

| NF2-intergenic (chr2:121337428–121338406) | 1 | |||

| NF2-intergenic (chr9:114706080–114707283) | 1 | |||

| NF2-intergenic (chr22:42851857–42852717) | 1 | |||

| NF2-RBFOX2 | 1 | |||

| NF2-COA1 | 1 | |||

| NF2-ADNP | 1 |

- novel gene fusions not previously reported.

- only in frame intronic rearrangement.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Parts of this study were funded by the Roderick D. MacDonald Fund, the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurologic Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital, and the Hamill Foundation. A.J.P. is supported by a K08 award by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (K08NS102474). The Human Tissue Acquisition and Pathology Core at Baylor College of Medicine is funded through P30 Cancer Center Support Grant NCI-CA125123.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Achey TS, McEwen CL, Hamm MW. Implementation of a workflow system with electronic verification for preparation of oral syringes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(Supplement_1):S28–S33. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxy019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holleczek B, Zampella D, Urbschat S, Sahm F, von Deimling A, Oertel J, et al. Incidence, mortality and outcome of meningiomas: A population-based study from Germany. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;62:101562. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aghi MK, Carter BS, Cosgrove GR, Ojemann RG, Amin-Hanjani S, Martuza RL, et al. Long-term recurrence rates of atypical meningiomas after gross total resection with or without postoperative adjuvant radiation. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(1):56–60; discussion doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000330399.55586.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modha A, Gutin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: a review. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(3):538–50; discussion −50. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000170980.47582.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Karas PJ, Hadley CC, Bayley VJ, Khan AB, Jalali A, et al. The Role of Merlin/NF2 Loss in Meningioma Biology . Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(11). doi: 10.3390/cancers11111633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viaene AN, Zhang B, Martinez-Lage M, Xiang C, Tosi U, Thawani JP, et al. Transcriptome signatures associated with meningioma progression. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0690-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel AJ, Wan YW, Al-Ouran R, Revelli JP, Cardenas MF, Oneissi M, et al. Molecular profiling predicts meningioma recurrence and reveals loss of DREAM complex repression in aggressive tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(43):21715–26. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912858116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira BJA, Oba-Shinjo SM, de Almeida AN, Marie SKN. Molecular alterations in meningiomas: Literature review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;176:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark VE, Erson-Omay EZ, Serin A, Yin J, Cotney J, Ozduman K, et al. Genomic analysis of non-NF2 meningiomas reveals mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO. Science. 2013;339(6123):1077–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1233009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark VE, Harmanci AS, Bai H, Youngblood MW, Lee TI, Baranoski JF, et al. Recurrent somatic mutations in POLR2A define a distinct subset of meningiomas. Nat Genet. 2016;48(10):1253–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brastianos PK, Horowitz PM, Santagata S, Jones RT, McKenna A, Getz G, et al. Genomic sequencing of meningiomas identifies oncogenic SMO and AKT1 mutations. Nat Genet. 2013;45(3):285–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards PA. Fusion genes and chromosome translocations in the common epithelial cancers. J Pathol. 2010;220(2):244–54. doi: 10.1002/path.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, Weinlich R, Dalton JD, Li Y, et al. C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature. 2014;506(7489):451–5. doi: 10.1038/nature13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agnihotri S, Suppiah S, Tonge PD, Jalali S, Danesh A, Bruce JP, et al. Therapeutic radiation for childhood cancer drives structural aberrations of NF2 in meningiomas. Nat Commun 2017;8(1):186. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00174-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPherson A, Hormozdiari F, Zayed A, Giuliany R, Ha G, Sun MG, et al. deFuse: an algorithm for gene fusion discovery in tumor RNA-Seq data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7(5):e1001138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmanci AS, Youngblood MW, Clark VE, Coskun S, Henegariu O, Duran D, et al. Integrated genomic analyses of de novo pathways underlying atypical meningiomas. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14433. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutmann DH, Hirbe AC, Haipek CA. Functional analysis of neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) missense mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(14):1519–29. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballare C, Lange M, Lapinaite A, Martin GM, Morey L, Pascual G, et al. Phf19 links methylated Lys36 of histone H3 to regulation of Polycomb activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(12):1257–65. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louvi A, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. CADASIL: a critical look at a Notch disease. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28(1–2):5–12. doi: 10.1159/000090748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitelman F, Johansson B, Mertens F. The impact of translocations and gene fusions on cancer causation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):233–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben-Neriah Y, Daley GQ, Mes-Masson AM, Witte ON, Baltimore D. The chronic myelogenous leukemia-specific P210 protein is the product of the bcr/abl hybrid gene. Science. 1986;233(4760):212–4. doi: 10.1126/science.3460176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Cao X, Lonigro RJ, Sung YS, et al. Identification of recurrent NAB2-STAT6 gene fusions in solitary fibrous tumor by integrative sequencing. Nat Genet. 2013;45(2):180–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haas BJ, Dobin A, Li B, Stransky N, Pochet N, Regev A. Accuracy assessment of fusion transcript detection via read-mapping and de novo fusion transcript assembly-based methods. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):213. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1842-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golub TR, Barker GF, Bohlander SK, Hiebert SW, Ward DC, Bray-Ward P, et al. Fusion of the TEL gene on 12p13 to the AML1 gene on 21q22 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(11):4917–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erickson P, Gao J, Chang KS, Look T, Whisenant E, Raimondi S, et al. Identification of breakpoints in t(8;21) acute myelogenous leukemia and isolation of a fusion transcript, AML1/ETO, with similarity to Drosophila segmentation gene, runt. Blood. 1992;80(7):1825–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asthagiri AR, Parry DM, Butman JA, Kim HJ, Tsilou ET, Zhuang Z, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 2. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1974–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60259-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmad Z, Brown CM, Patel AK, Ryan AF, Ongkeko R, Doherty JK. Merlin knockdown in human Schwann cells: clues to vestibular schwannoma tumorigenesis. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31(3):460–6. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181d2777f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chow HY, Dong B, Duron SG, Campbell DA, Ong CC, Hoeflich KP, et al. Group I Paks as therapeutic targets in NF2-deficient meningioma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(4):1981–94. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Striedinger K, VandenBerg SR, Baia GS, McDermott MW, Gutmann DH, Lal A. The neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, regulates human meningioma cell growth by signaling through YAP. Neoplasia. 2008;10(11):1204–12. doi: 10.1593/neo.08642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rong R, Tang X, Gutmann DH, Ye K. Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) tumor suppressor merlin inhibits phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase through binding to PIKE-L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(52):18200–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405971102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bi WL, Prabhu VC, Dunn IF. High-grade meningiomas: biology and implications. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44(4):E2. doi: 10.3171/2017.12.FOCUS17756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collord G, Tarpey P, Kurbatova N, Martincorena I, Moran S, Castro M, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of anaplastic meningioma identifies prognostic molecular signatures. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13537. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chamberlain PP, Qian X, Stiles AR, Cho J, Jones DH, Lesley SA, et al. Integration of inositol phosphate signaling pathways via human ITPK1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(38):28117–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703121200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huangyang P, Li F, Lee P, Nissim I, Weljie AM, Mancuso A, et al. Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphatase 2 Inhibits Sarcoma Progression by Restraining Mitochondrial Biogenesis. Cell Metab. 2020;31(1):174–88 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, Wang J, Xu H, Xing R, Pan Y, Li W, et al. Decreased fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase-2 expression promotes glycolysis and growth in gastric cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2013;12(1):110. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ong CT, Cheng HT, Chang LW, Ohtsuka T, Kageyama R, Stormo GD, et al. Target selectivity of vertebrate notch proteins. Collaboration between discrete domains and CSL-binding site architecture determines activation probability. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(8):5106–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dotto GP. Notch tumor suppressor function. Oncogene. 2008;27(38):5115–23. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park JT, Li M, Nakayama K, Mao TL, Davidson B, Zhang Z, et al. Notch3 gene amplification in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(12):6312–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dang TP, Gazdar AF, Virmani AK, Sepetavec T, Hande KR, Minna JD, et al. Chromosome 19 translocation, overexpression of Notch3, and human lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(16):1355–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui H, Kong Y, Xu M, Zhang H. Notch3 functions as a tumor suppressor by controlling cellular senescence. Cancer Res. 2013;73(11):3451–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papaioannou MD, Djuric U, Kao J, Karimi S, Zadeh G, Aldape K, et al. Proteomic analysis of meningiomas reveals clinically-distinct molecular patterns. Neuro Oncol 2019. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuevas IC, Slocum AL, Jun P, Costello JF, Bollen AW, Riggins GJ, et al. Meningioma transcript profiles reveal deregulated Notch signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2005;65(12):5070–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baia GS, Stifani S, Kimura ET, McDermott MW, Pieper RO, Lal A. Notch activation is associated with tetraploidy and enhanced chromosomal instability in meningiomas. Neoplasia. 2008;10(6):604–12. doi: 10.1593/neo.08356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cristobal I, Blanco FJ, Garcia-Orti L, Marcotegui N, Vicente C, Rifon J, et al. SETBP1 overexpression is a novel leukemogenic mechanism that predicts adverse outcome in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(3):615–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shou LH, Cao D, Dong XH, Fang Q, Wu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Prognostic significance of SETBP1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic neutrophilic leukemia: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang X, Shi L, Gao F, Russin J, Zeng L, He S, et al. Genomic and transcriptome analysis revealing an oncogenic functional module in meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2013;35(6):E3. doi: 10.3171/2013.10.FOCUS13326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandenbergh DJ, Persico AM, Hawkins AL, Griffin CA, Li X, Jabs EW, et al. Human dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) maps to chromosome 5p15.3 and displays a VNTR. Genomics. 1992;14(4):1104–6. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torres GE, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(1):13–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petrera A, Lai ZW, Schilling O. Carboxyterminal protein processing in health and disease: key actors and emerging technologies. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(11):4497–504. doi: 10.1021/pr5005746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez de la Vega M, Sevilla RG, Hermoso A, Lorenzo J, Tanco S, Diez A, et al. Nna1-like proteins are active metallocarboxypeptidases of a new and diverse M14 subfamily. FASEB J. 2007;21(3):851–65. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7330com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Negrini S, Gorgoulis VG, Halazonetis TD. Genomic instability--an evolving hallmark of cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(3):220–8. doi: 10.1038/nrm2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bi WL, Greenwald NF, Abedalthagafi M, Wala J, Gibson WJ, Agarwalla PK, et al. Genomic landscape of high-grade meningiomas. NPJ Genom Med. 2017;2. doi: 10.1038/s41525-017-0014-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen S, Liu M, Huang T, Liao W, Xu M, Gu J. GeneFuse: detection and visualization of target gene fusions from DNA sequencing data. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14(8):843–8. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.24626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cardis E, Hatch M. The Chernobyl accident--an epidemiological perspective. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23(4):251–60. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.01.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]