Abstract

Background

Intense pulsed light (IPL), as a therapeutic approach for rosacea, had advantage in removing erythema and telangiectasia and was gradually accepted by rosacea patients, but there have been few studies on economic evaluation of this therapy.

Purpose

This study aimed to detect willingness-to-pay (WTP) of IPL treatment for rosacea and to conduct a benefit–cost analysis (BCA) among the Chinese population, so as to provide an economic reference for doctors to make treatment decisions.

Materials and Methods

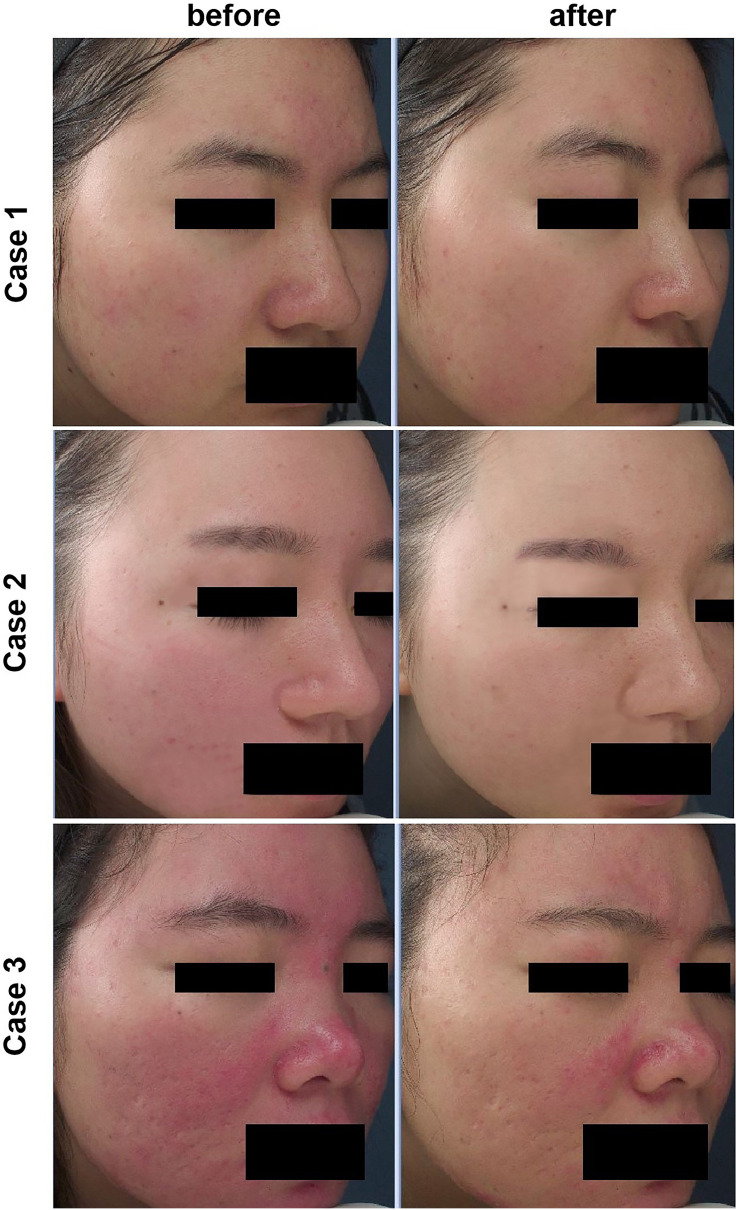

An observational, cross-sectional study assessed respondent’s demographic characteristics and willingness-to-pay (WTP) of IPL and rosacea patients’ clinical data and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). WTP was obtained by contingent valuation (CV) method. In brief, contrast figures of three cases treated with IPL (Case1, Case2, and Case3 represented the increasing severity of rosacea) were showed and WTP was inquired. The costs were obtained according the market and compared with WTP (benefits) to get a benefit–cost ratio (BCR). Predictors of cost-effective WTP were identified using the multivariable logistic regression model.

Results

A total of 303 rosacea patients and 202 controls were included in the study. The average cost of a single IPL treatment for rosacea was USD 208.04 in Changsha, China. The mean WTP for Case 1, Case 2, and Case 3 was USD 201.57, 214.64, and 221.74, respectively. WTP was statistically lower for Case 1 than that for Case 2 or Case 3 (P<0.05). The BCRs were 0.85, 1.03, and 1.06 for Case 1, Case 2, and Case 3, respectively. WTP is significantly associated with household monthly income, previous treatment cost, and DLQI after adjustments for demographic characteristics (P<0.05).

Conclusion

IPL is an acceptable treatment for rosacea with moderate to severe erythema. For patients with relatively high income or severely impaired quality of life, IPL is an economically feasible therapy and deserves to be recommended.

Keywords: benefit-cost analysis, intense pulsed light, rosacea, willingness-to-pay, economic evaluation

Introduction

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the facial skin, characterized by recurring episodes of several symptoms including facial flushing, erythema, papules, pustules, and telangiectasia in a symmetrical facial distribution.1,2 Epidemiological studies show that the incidence of rosacea is 5.5% in the global population and 3.48% in China.3,4

Management of rosacea is varying, including appropriate skin care and lifestyle management, as well as topical and oral therapies.5,6 Most treatments are generally effective at inhibiting the inflammatory pathways involved in rosacea,6 thereby promoting the mitigation of papules and pustules. However, the erythema is hard to completely clear by traditional treatments. In fact, it is exactly the conspicuous facial redness often has a deep impact on the patient’s self-esteem and quality of life.1,7,8 Based on the Clinician’s Erythema Assessment (CEA), an authorized measurement for the facial erythema of rosacea, there are 5 levels contained: Clear (Clear skin with no signs of erythema), Almost clear (Almost clear; slight redness), Mild (Mild erythema, definite redness), Moderate (Moderate erythema; marked redness), and Severe (Severe erythema; fiery redness).9 It is reported that for patients with an “almost clear” evaluation of the erythema, quit a few of them still desired further mitigation of the redness and to achieve “clear”.10 Thus, it is important to optimize therapeutic strategies for rosacea beyond the available medications and minimize the negative impact on life.

Intense pulsed light (IPL), whose therapeutic applications include vascular lesions, skin rejuvenation, and pigmented lesions, can improve the persistent erythema and telangiectasia of rosacea as an adjuvant therapy for rosacea. The mechanism of IPL in the therapeutic effect on rosacea mainly based on the selective photothermolysis of dilated blood vessels. Besides, it also has immunomodulatory effects on inflammatory processes and possibly on collagen remodelling.11,12 Compared with other laser devices, advantages of IPL include milder adverse reactions, general versatility, a shorter treatment duration, and without delayed working time.13,14 In recent years, successful treatment of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (ETR) with IPL has been widely documented. It was reported that improved clinical outcomes were expected after an average 3 times of IPL treatments.15 Especially for refractory erythema, IPL treatment can achieve the effect that medicine is difficult to achieve. However, the cost of IPL treatment, ranging from Chinese yuan (CNY) 1000 to 2000 is much higher than that of traditional drug treatment, limiting its application among patients with modest financial conditions. Further, Because of the limited health-care resources in China, evidences of both the therapeutic efficacy and cost-effectiveness were increasingly required when conducting a new treatment.

Consequently, an increasing number of health economic studies are being published in the field of rosacea. Nevertheless, we did not find any benefit-cost analysis (BCA) using willingness to pay (WTP) approach in the field of IPL treatment for rosacea. Willingness to pay (WTP), defined as the amount of money an individual is willing to spend in a hypothetical scenario to obtain a certain effect, has increasingly been used as a valuation measure for healthcare and health-related quality of life (HRQOL).16 Benefit-cost analysis (BCA) of a specific treatment can be performed by measuring patients’ WTP for a certain treatment and understanding whether a patient’s preferences outweigh costs, which can help to make decisions and subdivide patients’ demands.17,18 This method has at least two key advantages: 1) WTP can evaluate benefits more comprehensively than quality-adjusted life-years and 2) BCA allows questions of allocative efficiency to be addressed.17,19

In order to evaluate whether IPL for rosacea treatment is economical and cost-effective in China, in the current study, we detected the WTP with a contingent valuation (CV) as previously described and conduct BCA for the IPL treatment among Chinese rosacea patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

We performed an observational, cross-sectional study among Chinese populations aged 18 and above. The study was conducted from December 2019 to February 2020. The patients included have two sources. Some were enrolled from the current outpatients in the Department of Dermatology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (CSU), and the others were from the Rosacea Database of Xiangya Hospital, CSU who had registered ahead of the survey. All the patients registered in the Database have been diagnosed by two dermatologists separately and met the diagnostic criteria of rosacea based on the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee,20 and they do not have to be invited to the clinic for examination by social media. All skin-healthy controls included in our study were recruited in the Physical Examination Center, Xiangya Hospital, CSU. The participants were examined by an experienced dermatologist and those with rosacea or other facial skin diseases were excluded. An online survey link was created and the investigators can directly invite the participants by social media platforms (dermatology platforms and WeChat groups). Each participant was allowed to submit a questionnaire once by the IP address in order to avoid repeated submissions.

Study Questionnaire

The questionnaire is divided into four parts: demographic characteristics, willingness-to-pay (WTP), clinical data, and quality of life (QoL). Demographic characteristics including age, gender, residence, education level, marital status, household monthly income. In the rosacea group, clinical data on duration of disease, previous treatment cost, the degree of satisfaction to prior treatment (1–10), and patients self-rated severity of symptoms (0–10) were presented.

Benefits: WTP

In our study, WTP approximated benefits were evaluated by the contingent valuation (CV) method.21 This method is widely acknowledged as a theoretically acceptable method for potential consumers to value goods and services. At first, the participants were educated about the effects, process, and adverse effects of IPL treatment, so that the respondents had a sufficient understanding of the studied treatment. Pictures of three typical rosacea cases before and after IPL treatment (Figure 1), which demonstrated typical and average therapeutic effects of patients with different levels of severity, were presented to the respondents (For ease of understanding, we uses Case 1, Case 2, and Case 3 to describe the cases according to the increasing level of severity below). Then the same standardized question elicited WTP:

How much would you be willing to pay for one new treatment with minor side effects to achieve the effects as shown in contrast figure? (This new treatment requires 3–5-time visits and cost 15 minutes per time).

Figure 1.

Pictures of three rosacea patients before and after IPL treatment.

The options of WTP consisted of five discrete amounts of monetary value as follows: CNY2000, 1800, 1500, 1000, and 500.22

DLQI

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), a widely used tool to evaluate skin disease patients’ quality of life,23 using six domains, could group its 10 questions as follows: Symptoms, feelings (1,2), Daily activities (3,4), Leisure (5,6), Work/school (7), Personal relationships (8,9), Treatment (10). A higher DLQI score implies a greater QoL impairment.24 Banding of the DLQI with the scores for each band: No effect (0–1), Mild effect (2–5), Moderate effect (6–10), Severe effect (11–20), Very severe effect (21–30).23

Average Costs

The average costs of a single IPL treatment for rosacea include direct medical costs (physician visit fees, IPL treatment fees, and post-treatment complementary costs), direct nonmedical costs (travel costs), and indirect costs (time off from work to visit physician) (Table 1). Because there was no standard pricing for IPL treatment in China, the price per IPL treatment was estimated using the mean cost in three Chinese tertiary hospitals (Xiangya Hospital; The Second Xiangya Hospital; and Xiangya Third Hospital, Central South University). Physicians’ professional fees and indirect costs in terms of time loss were estimated according to the data from the 2019 Yearbook of Health Statistics of China and China Labour Statistical Yearbook 2019.25,26 All costs in this study are expressed in USD with an exchange rate of USD 1=CNY6.8985 (2019).

Table 1.

Aggregated Costs of IPL Treatment per Time

| Cost | Hospital1 (USD) | Hospital 2 (USD) | Hospital 3 (USD) | Average (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct costs | ||||

| Physician visit | 4.16 | 5.25 | 4.00 | 4.47 |

| IPL treatment | 181.19 | 217.44 | 144.96 | 181.20 |

| Post-treatment costs | 5 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Direct nonmedical cost | ||||

| In-city transportation | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Indirect costs | ||||

| Time off from work | 13.73 | 13.73 | 13.73 | 13.73 |

| Total | 206.08 | 246.42 | 172.69 | 208.40 |

BCA

Benefit-cost analysis (BCA) is obtained by calculating benefit-cost ratio (BCR) as previously.27 From the participant perspective, the average WTP divided by the total cost for IPL is the BCR.22 If the benefits outweighed the costs (ie, BCR>1), the IPL treatment was considered worth providing.

Statistical Analyses

The comparisons of the relative average WTP of the responders with different characteristics were statistically analyzed, respectively, by the Mann–Whitney U-tests (Binary variables) or Kruskal–Wallis test (Multi-categorical variables). The average WTP for each case was analyzed separately. Means, medians, and IQR were used for statistical description. The Friedman test was used to compare the mean WTP among three patients. Multivariable logistic regression (forward elimination: Wald) analyses of all potential predictors as independent variables and cost-effective WTP (BCR>1) as the dependent variable were performed. The odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IMB Corp).

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board of the Xiangya Hospital, CSU, China, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants before the investigation. Before the pictures of the three cases were used in the questionnaires and articles, and written informed consent has been obtained from the patients. We have obtained the three patients’ informed consent for the images to be published.

Result

A total of 303 rosacea patients and 202 age-matched healthy controls completed the study. The majority of participants (85.61%) were female. The general characteristics and the corresponding WTP of all the participants are shown in Table 2. For rosacea patients, the clinical data and the corresponding WTP are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Participants’ Demographic Characteristics and the Corresponding WTP

| Demographic Characteristics | N (%) | Average WTP (USD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 83(16.44) | 210.45 | 216.57 | 222.33 |

| Female | 422(83.56) | 199.82 | 214.28 | 221.63 |

| Age | ||||

| <30 | 275(54.46) | 197.62 | 212.17 | 221.71 |

| ≥30 | 230(45.54) | 206.28 | 217.63 | 221.79 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 460 (91.09) | 201.49 | 214.41 | 222.17 |

| Rural | 45 (8.91) | 202.30 | 217.12 | 217.44 |

| Education level | ||||

| High school, technical secondary school and blow | 85(16.83) | 191.86 | 200.90 | 203.45 |

| Undergraduate and junior college | 367(72.67) | 205.08 | 217.40 | 223.21 |

| Postgraduate and above | 53(10.5) | 192.82 | 217.71 | 240.96 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 197(39.01) | 196.03 | 208.02 | 218.10 |

| In a stable relationship | 72(14.26) | 195.29 | 218.04 | 226.90 |

| Married | 236(46.73) | 208.10 | 219.16 | 223.21 |

| Household monthly incomea | ||||

| ≤1203.16 | 255(50.50) | 180.15 | 195.78 | 202.37 |

| >1203.16 | 250 (49.50) | 223.41 | 233.91 | 241.50 |

| Have or do not have rosacea | ||||

| You have rosacea | 303(60.0) | 196.53 | 211.51 | 216.63 |

| You do not have rosacea | 202(40.0) | 209.11 | 219.38 | 229.42 |

Notes: a In the three cases, there are significant differences in WTP among different household monthly income levels (P<0.05). There is no significant difference in WTP among other participants’ characteristics.

Table 3.

Rosacea Patients’ Clinical Data and the Corresponding WTP

| Clinical Data | N (%) | Average WTP (USD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | ||

| Duration of rosacea, year | ||||

| 0–1 | 76 (25.08) | 206.21 | 222.13 | 229.89 |

| 1–5 | 227 (74.92) | 197.79 | 212.07 | 217.02 |

| The degree of satisfaction to prior treatment | ||||

| 0–3 | 65(23.30) | 209.63 | 218.11 | 218.55 |

| 4–6 | 114(40.86) | 194.93 | 213.80 | 221.13 |

| 7–10 | 100(35.84) | 199.32 | 213.81 | 220.48 |

| Previous treatment cost | ||||

| <724.80a | 180(59.41) | 182.39 | 197.81 | 203.40 |

| 724.80–1449.59 | 63(20.79) | 218.59 | 231.24 | 237.00 |

| >1449.59 | 60(19.80) | 227.43 | 242.43 | 247.89 |

| Patients self-rated severity of symptoms | ||||

| 0–3 | 85(28.05) | 189.20 | 217.06 | 221.77 |

| 4–6 | 126(41.59) | 201.19 | 210.94 | 219.06 |

| 7–10 | 92(30.36) | 207.83 | 217.44 | 220.64 |

Notes: aWTP of Previous treatment cost<724.80 is significantly different from the other two groups. There is no significant difference in WTP among other parameters.

DLQI

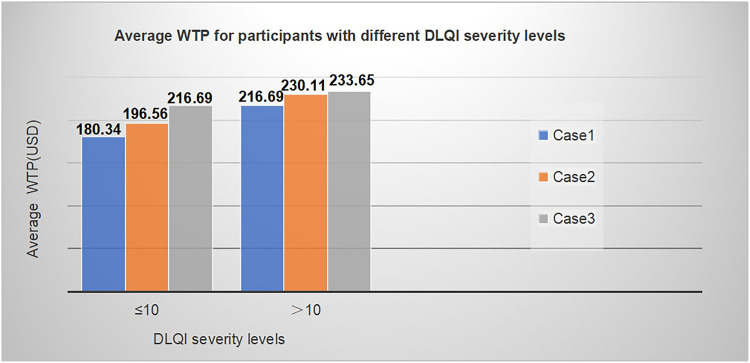

The mean DLQI total score in rosacea was 11.07±8.04, and the median value was 10. A DLQI score of >10, indicating a severe or very severe limitation of quality of life,24 was calculated for 44.6% of all patients with rosacea. The distribution of average WTP for different DLQI severity levels is shown in Figure 2. With Mann–Whitney U-tests, WTP of patients with severe or every severe effect quality of life (QoL) was significantly higher than that of moderate or below effect QoL (P<0.05). The relationship between DLQI score and WTP is shown in Table 4. The DLQI total scores correlated positively with WTP (P<0.05). For DLQI specific problems, only question 8 which represents personal relationship has a significant correlation with WTP (P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Average WTP for different DLQI score.

Table 4.

WTP of DLQI Specific Problems for Different Case Scenarios of IPL Treatment: Multivariable Logistic Models (Demographic Data Have Been Adjusted)

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| DLQI total scores | 1.35(1.11–1.65) | 0.003 | 1.37(1.12–1.67) | 0.003 | 1.30(1.06–1.60) | 0.012 |

| 1 | 1.32(0.92–1.91) | 0.13 | 1.02(0.71–1.47) | 0.919 | 0.98(0.68–1.42) | 0.918 |

| 2 | 0.61(0.37–1.01) | 0.057 | 0.73(0.43–1.23) | 0.729 | 0.98(0.59–1.63) | 0.930 |

| 3 | 1.11(0.70–1.77) | 0.655 | 1.26(0.77–2.05) | 0.363 | 1.48(0.90–2.42) | 0.124 |

| 4 | 0.97(0.65–1.46) | 0.897 | 0.78(0.51–1.20) | 0.262 | 0.88(0.57–1.35) | 0.559 |

| 5 | 0.86(0.51–1.46) | 0.585 | 0.96(0.56–1.65) | 0.894 | 0.74 (0.43–1.27) | 0.269 |

| 6 | 1.13(0.77–1.65) | 0.546 | 1.05(0.71–1.56) | 0.804 | 1.26(0.84–1.87) | 0.259 |

| 7 | 1.37(0.96–1.95) | 0.082 | 1.25(0.87–1.80) | 0.231 | 1.06(0.73–1.52) | 0.765 |

| 8 | 2.06(1.22–3.47) | 0.007 | 2.25(1.29–3.93) | 0.004 | 1.93(1.10–3.38) | 0.022 |

| 9 | 1.22(0.81–1.83) | 0.342 | 1.17(0.76–1.82) | 0.474 | 1.06(0.69–1.64) | 0.789 |

| 10 | 0.69(0.44–1.08) | 0.082 | 0.79(0.50–1.26) | 0.326 | 0.66(0.41–1.05) | 0.082 |

Note: The numbers 1 to 10 represent questions 1 to 10 in the dermatology life quality index (DLQI) questionnaire.24

WTP for Different Cases and BCR

The mean and median WTP for the three cases are presented in Table 5, which showed the participant’s WTP increased with the increasing level of the severity of the disease. WTP for Case 1 was statistically lower than that for Case 2 (P=0.028) or Case 3 (P<0.001). However, differences in WTP between Case 2 and Case 3 were not significant (P=0.559). BCR of Cases 2 and 3 > 1 among the three cases (Table 5), indicating that the expected benefit exceeded the mean cost of IPL treatment, and IPL is profitable.

Table 5.

Willingness-to-Pay (WTP) for Different Case Scenarios of IPL Treatment per and Benefit–Cost Ratios

| Case | Mean WTP per Timea (USD) | Median WTP per Time (IQR) (USD) | Benefit–Cost Ratio (BCR) | BCR>1(WTP Overweight the Cost of USD208.40)(N(%)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 201.57 | 289.92(72.48–289.92) | 0.97 | 277(54.85) |

| 2 | 214.65 | 289.92(144.96–289.92) | 1.03 | 315(62.38) |

| 3 | 221.74 | 289.92(144.96–289.92) | 1.06 | 338(66.93) |

Note: aIn Case 1 VS Case 2 and Case 1 VS Case 3, the difference in WTP is statistically significant (P<0.05).

Predictors of Cost-Effective WTP (BCR>1)

In a multivariable logistic regression analysis, household monthly income, previous treatment cost, and DLQI score were independently and significantly associated with a cost-effective WTP (BCR>1) (Table 6). In the three cases, participants in the high-income group (>USD 1203.16/month) were more likely to pay the cost for IPL compared to those with low-income (OR 1.89–2.16). The relationship of DLQI score with WTP was seemed to be strongest with the largest OR. And in Case 3, the longer duration of rosacea and the higher education level displayed a positive relationship with WTP, covering the cost (P<0.05).

Table 6.

Associations of Rosacea Patients’ Characteristics and WTP Analyses

| Predictor | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age | / | / | 0.98(0.95–1.01) | 0.097 | / | / |

| Education level | / | / | / | / | 1.92(1.13–3.28) | 0.016 |

| Household monthly income | 2.42(1.45–4.03) | 0.001 | 2.23(1.31–3.80) | 0.003 | 2.09(1.20–3.63) | 0.009 |

| Duration of rosacea | / | / | / | / | 0.46(0.24–0.88) | 0.019 |

| Previous treatment cost | 1.37(0.99–1.90) | 0.058 | 1.56(1.08–2.25) | 0.018 | 1.58(1.09–2.29) | 0.017 |

| DLQI (Severity effect and above band) | 2.51(1.50–4.18) | <0.001 | 2.26(1.33–3.86) | 0.003 | 2.15(1.24–3.72) | 0.007 |

Note: Fitted Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis with BCR>1(WTP overweight the cost of USD208.40) as the Outcome.

Discussion

To date, this study provides the first comprehensive data on WTP of IPL treatment for rosacea. The result of BCR>1 for Case 2 and Case 3 suggested that IPL is roughly cost-effective and has good acceptance and promotion value among rosacea patients with moderate or severe erythema.

Our study did not detect cost-effectiveness using the traditional methods with cost/clinical outcomes or cost/quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), because different individuals have different subjective values for health benefits.28 For skin conditions with the rare risk of disability or death, WTP can reflect the preferences and disease burden in a monetary manner, which may be more accurate and direct in detecting BCA compared with the traditional tools. In the past, there are a few studies that used WTP method to obtain the BCA for a specific treatment in the field of dermatology.22,29–34 In this study, WTP and BCA analysis can help us to know the IPL treatment preferences in rosacea patients and provided evidence of pharmacoeconomics for health policymakers and patients in China.

In this study, the elicited WTP is valid because WTP of IPL for rosacea treatment was significantly associated with household monthly income, according to economic common sense. Meanwhile, in Case 3, there is a significant positive correlation between participants’ education level and WTP. In general, people with higher education tend to have higher wages and higher personal image requirements. These further confirm the reliability and rationality of our results.

According to our results, WTP increased as the severity of facial erythema increased in three cases. And the obtained BCR of Case 2 and 3 both showed benefits outweighed costs. It may be attributed to the visualized effects of Cases 2 and 3 are more apparent compare to Case 1, as the removal of redness is more effective. The significant differences among the cases indicated that personalized treatment is needed, and it is particularly important to implement IPL to treat moderate to severe rosacea with persistent and refractory erythema. However, in this study, we did not find significant differences in WTP among patients with varying self-rated severity, which might be partly explained by the fact that the self-reported information was generally neither accurate nor objective.

Rosacea patients often have an impact on their quality of life due to their discosmetic appearance and recurring symptoms.7,35 DLQI is a common indicator for evaluating the quality of life and represents the disease burden. Based on our results, almost 44.6% of participants reported unsatisfying general health and the mean DLQI score of 11.07 reflected a severe impairment of quality of life. Notably, WTP has also been demonstrated to be a valid method to assess an individual’s burden of skin disease and has a correlation with DLQI.34,36 Although WTP referred in our study was specific to IPL treatment, it could reflect the burden of disease to some extent. As expected, an explicit positive correlation between the DLQI score and WTP was observed in our study. Rosacea patients whose quality of life was severely affected were willing to spend significantly more money on IPL treatment than those whose quality of life was less affected. Among the questions contained in DLQI, question 8 (Over the last week, how much has your skin created problems with your partner or any of your close friends or relatives?) showed the strongest correlation with WTP, suggesting the impaired personal relationships was an important factor that may influence the decision to pay for a new therapy, and reflected a high disease burden.

In addition, we found WTP for IPL treatment is higher for patients with shorter disease duration or higher previous cost for treatment, which were both indirect indicators of disease burden. It has been previously proved that patients with longer disease duration were less likely to have a high WTP/severe impairment of quality of life.33,37 The previous treatment cost represents the occupied medical resources and reflects the social burdens as well. These close associations of WTP with the indicators of disease burden indicated the feasibility of IPL therapy in rosacea patients with high disease burden. Compared with filling the DLQI, knowledge of the skin duration and treatment experiences can help doctors understand the patient’s disease burden quickly, then to optimize the medical decisions.

In order to understand the acceptance of IPL among the general public and to judge if it is economical, we also investigated 202 normal populations on WTP for IPL. Interestingly, we found that participants without rosacea were willing to pay more than the patients, though the difference was not significant. The possible explanation was that the chronic feature of rosacea made the patients adapt to the situation, and thus have relatively little visual impact on the therapeutic effects presented. On the other hand, the suffered patients might be unwilling to pay for IPL because of their low confidence in treatment.

There are several limitations to our study. First, because it is an online questionnaire, all information related to clinical symptoms is self-evaluation and lack accurate and object information about the severity of rosacea patients. However, this deficiency can be partially supplemented by choosing three cases with different levels of severity to investigate the relationship between the WTP and disease severity. In addition, because it is hard to standardize and quantify the therapeutic efficacy of IPL due to different skin types and rosacea types, expert-selected cases for WTP might lead to less accuracy and more subjective conclusions. However, in order to meet the majority of patients’ requirements for representativeness and accuracy, visualized cases are the most feasible method to demonstrate the expected effect and detect WTP.

Conclusion

IPL is an economically acceptable and cost-effective treatment for rosacea patients with moderate to severe erythema in China. The WTP value is positively associated with household monthly income, previous treatment cost, and DLQI score. From the perspective of health economics, IPL is a feasible therapy and deserves to be recommended for patients with relatively high income or severely impaired quality of life.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81502750). The authors thank all of the responders who participated in this study and their legal guardians, and the following investigators (in order of family name): Ming-liang Chen, Zhi-yu Hong, Dan Jian, Yu-meng Jiang, Ye-hong Kuang, Pei-yao Li, Jie Li, Yu-yan Ouyang, Juan Su, Qi Shi, Yan Tang, Ya-ling Wang, Ben Wang, Jiang-lin Zhang, Jin-mao Li, Xiang Chen, Fangfang Li, Fan Wang, Xin Meng, Xi-zhao Yang, Lei Zhou, Ya Zhang, Zhi-xiang Zhao, Shuang Zhao, Yi-ya Zhang.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. Co-first authors: Qing Deng and Shu-ping Zhang.

References

- 1.Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9(1):e1361574. doi: 10.1080/19381980.2017.1361574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the national rosacea society expert committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Wang B, Deng Y, et al. Epidemiological features of rosacea in Changsha, China: a population-based, cross-sectional study. J Dermatol. 2020;47(5):497–502. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(2):282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang YX, Li J, Zhao ZX, et al. Effects of skin care habits on the development of rosacea: a multi-center retrospective case-control survey in Chinese population. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the national rosacea society expert committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):1501–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Q, Tang Y, Shi X, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and health-related quality of life of rosacea in Chinese adolescents: a population-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Xie H, Gong Y, et al. Relationship between rosacea and sleep. J Dermatol. 2020;47(6):592–600. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan J, Liu H, Leyden JJ, Leoni MJ. Reliability of clinician erythema assessment grading scale. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(4):760–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan J, Steinhoff M, Bewley A, et al. Rosacea: beyond the visible. The BMJ hosted content; 2018. Available from: https://hosted.bmj.com/rosaceabeyondthevisible. Accessed May, 2019.

- 11.Rone M, Kisis J. A12 IPL therapy in the inflammatory stage of rosacea. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2002;1(2):108. doi: 10.1046/j.1473-2165.2002.00040_13.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papageorgiou P, Clayton W, Norwood S, Chopra S, Rustin M. Treatment of rosacea with intense pulsed light: significant improvement and long-lasting results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(3):628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawana S, Ochiai H, Tachihara R. Objective evaluation of the effect of intense pulsed light on rosacea and solar lentigines by spectrophotometric analysis of skin color. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(4):449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li YH, Wu Y, Chen JZ, et al. A split-face study of intense pulsed light on photoaging skin in Chinese population. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42(2):185–191. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann MA, Lehmann P. Physical modalities for the treatment of rosacea. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14(Suppl 6):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanBeek MJ. Integrating patient preferences with health utilities - a variation on health-related quality of life. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(8):1037–1041. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.8.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen JA, Smith RD. Theory versus practice: a review of ‘willingness-to-pay’ in health and health care. Health Econ. 2001;10(1):39–52. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samson AL, Schokkaert E, Thébaut C, et al. Fairness in cost-benefit analysis: a methodology for health technology assessment. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haefeli M, Elfering A, McIntosh E, Gray A, Sukthankar A, Boos N. A cost-benefit analysis using contingent valuation techniques: a feasibility study in spinal surgery. Value Health. 2008;11(4):575–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard grading system for rosacea: report of the national rosacea society expert committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(6):907–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadick M, Muller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular anomalies (part i): classification and diagnostics of vascular anomalies. Rofo. 2018;190(9):825–835. doi: 10.1055/a-0620-8925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao Y, Chen L, Jing D, et al. Willingness-to-pay and benefit-cost analysis of chemical peels for acne treatment in China. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:363–370. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S194615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The dermatology life quality index 1994–2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):997–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. The 2019 Yearbook of Health Statistics of China. Beijing: Beijing Union Medical University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Bureau of Statistical of the People’s Republic of China. China Labour Statistical Yearbook 2019. Beijing: China Statistics Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trippoli S. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio and net monetary benefit: current use in pharmacoeconomics and future perspectives. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;43:e36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Firth SJ. The quality adjusted life year: a total-utility perspective. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2018;27(2):284–294. doi: 10.1017/S0963180117000615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, Hermansson C, Lindberg M. Quality of life, health-state utilities and willingness to pay in patients with psoriasis and atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(6):1067–1075. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiffner R, Brunnberg S, Hohenleutner U, Stolz W, Landthaler M. Willingness to pay and time trade-off: useful utility indicators for the assessment of quality of life and patient satisfaction in patients with port wine stains. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(3):440–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delfino M Jr, Holt EW, Taylor CR, Wittenberg E, Qureshi AA. Willingness-to-pay stated preferences for 8 health-related quality-of-life domains in psoriasis: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(3):439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beikert FC, Langenbruch AK, Radtke MA, Kornek T, Purwins S, Augustin M. Willingness to pay and quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2014;306(3):279–286. doi: 10.1007/s00403-013-1402-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beikert FC, Langenbruch AK, Radtke MA, Augustin M. Willingness to pay and quality of life in patients with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(6):734–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04549.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu SW, Tkachenko E, Lam C, et al. Willingness-to-pay stated preferences in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a pilot study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, Desai SR, Rendon MI, Taylor SC. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1722–1729.e1727. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seidler AM, Bayoumi AM, Goldstein MK, Cruz PD Jr, Chen SC. Willingness to pay in dermatology: assessment of the burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(7):1785–1790. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stefanidou M, Evangelou G, Kontodimopoulos N, et al. Willingness to pay and quality of life in patients with pruritic skin disorders. Arch Dermatol Res. 2019;311(3):221–230. doi: 10.1007/s00403-019-01900-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]