Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to develop a tool for predicting in-hospital mortality of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted on 531 CAP patients with T2DM at The First Hospital of Qinhuangdao. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Variables to develop the nomogram were selected using multiple logistic regression analysis. Discrimination was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Calibration was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and calibration plot.

Results

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that age, pulse, urea and albumin (APUA) were independent risk predictors. Based on these results, we developed a nomogram (APUA model) for predicting in-hospital mortality of CAP in T2DM patients. In the training set, the area under the curve (AUC) of the APUA model was 0.814 (95% CI: 0.770–0.853), which was higher than the AUCs of albumin alone, CURB-65 and Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) class (p<0.05). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test (χ2=5.298, p=0.808) and calibration plot (p=0.802) showed excellent agreement between the predicted possibility and the actual observation in the APUA model. The results of the validation set were similar to those of the training set.

Conclusion

The APUA model is a simple and accurate tool for predicting in-hospital mortality of CAP, adapted for patients with T2DM. The predictive performance of the APUA model was better than CURB-65 and PSI class.

Keywords: community-acquired pneumonia, albumin, mortality, type 2 diabetes

Plain Language Summary

Current Knowledge

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is more common in patients with diabetes, especially type 2 diabetes (T2DM). CURB-65 and pneumonia severity index (PSI) are two classical tools for evaluating the severity of CAP. However, the predictive performances of CURB-65 and PSI class were poor in patients with diabetes. Albumin is a protein made by the liver that plays many important roles. Low serum albumin was associated with the risk of mortality in T2DM patients with infection.

What This Paper Contributes to the Existing Knowledge

In this study, age, pulse, urea and albumin (APUA) model were independent risk predictors for in-hospital mortality of CAP in T2DM patients. Based on these results, we developed a nomogram (APUA model) for predicting in-hospital mortality of CAP in T2DM patients. The APUA model is a simple and accurate tool for predicting in-hospital mortality of CAP, adapted for patients with T2DM. The predictive performance of the APUA model was better than CURB-65 and PSI class.

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common respiratory disease, with an incidence of 1.76–9.6 per 1000 person-years.1–5 Diabetes is another global problem. About 463 million adults were living with diabetes worldwide in 2019.6 Patients with diabetes have an increased risk of up to 1.4 for CAP.7 Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is the most common type. Therefore, CAP is more common in patients with diabetes, especially T2DM.

The outcomes varied enormously between different CAP patients, from rapid recovery to death. CURB-65 and Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) are two classical tools for evaluating the severity of CAP and are recommended by several CAP guidelines.8–11 A previous meta-analysis showed that the area under the curves (AUCs) of CURB-65 and PSI were about 0.8 for predicting 30-day mortality in hospitalized CAP patients.12 However, the predictive performances of CURB-65 and PSI class were poor in patients with diabetes. The AUCs of CURB-65 and PSI were only 0.669 and 0.682 in patients with T2DM.13

Albumin is a protein made by the liver that plays many important roles. Numerous studies confirmed that serum albumin correlated with short-term and long-term mortality of CAP.14–17 In the CAP-China network, albumin level was also an independent predictor of 60-day mortality of CAP.18

Serum albumin is closely related to the risk of death in T2DM. The level of albumin was negatively correlated with early mortality among elderly patients with T2DM.19 Low albumin levels increase the risk of mortality in diabetic patients with diabetic foot and chronic kidney disease.20,21 Low serum albumin was also associated with the risk of mortality in T2DM patients with infection. In T2DM, low albumin levels increase the risk of mortality in patients with community-onset bacterial bloodstream infections.22,23

Therefore, in this study, we developed a tool for predicting in-hospital mortality of CAP in patients with T2DM.

Methods

Subjects

The patients in this study were included from a survey on in-hospital mortality of CAP in patients with T2DM at our hospital. All subjects were adult inpatients, who were hospitalized due to CAP between January 2015 and December 2018. Patients with type 1 diabetes, other specific types of diabetes, no clear type classification, pre-diabetes, pregnancy and obstetric infection were excluded. Patients with missing clinical data on serum albumin, CURB-65 and PSI were also excluded. Eventually, 2365 patients, aged 66.6±17.3 years, were enrolled. Among these patients, 531 were T2DM patients (22.5%), while 1834 were non-diabetics. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Hospital of Qinhuangdao.

Data Collection

Initial data after admission were extracted from the Hospital Information System. Sociodemographic variables included age, gender and ethnicity. Serum albumin, CURB-65 and PSI were also collected. The scores of CURB-65 and PSI were calculated.24,25 According to the PSI score, the patients were classified into five risk classes. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL), R version 3.6.1 (R Development Core Team; http://www.r-project.org) and MedCalc15.2.2 (Ostend, Belgium) software. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For nomogram development and validation, we randomly assigned 70% of the participants to the training set and 30% to the validation set. The characteristics of the two sets were described and compared using chi-square test or Student’s t-test. Variables to develop the nomogram were selected using multiple logistic regression analysis.

Nomogram validation consisted of two parts, discrimination and calibration. Discrimination was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI). Calibration was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and calibration plot. Clinical effectiveness was evaluated using the decision curve analysis (DCA).

Results

This study enrolled 531 CAP patients with T2DM (305 males and 226 females), aged 71.7±11.7 years. The participants were randomly divided into the training set (n=359) and the validation set (n=172). No statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics, CURB-65, PSI and in-hospital mortality were observed between the two sets (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Training and Validation Set in Community-Acquired Pneumonia Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

| Variables | All (N=531) |

Training Set (N=359) |

Validation Set (N=172) |

t or χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (males/females) | 305/226 | 212/147 | 93/79 | 1.181 | 0.277 | |

| Age (years) | 71.7±11.7 | 72.0±11.6 | 71.1±11.9 | 0.826 | 0.409 | |

| Ethnicity [n(%)] | Han | 509(95.9) | 342(95.3) | 167(97.1) | 2.879 | 0.237 |

| Other | 15(2.8) | 13(3.6) | 2(1.2) | |||

| Unknown | 7(1.3) | 4(1.1) | 3(1.7) | |||

| Confusion [n(%)] | 63(11.9) | 43(12.0) | 20(11.6) | 0.014 | 0.907 | |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.9±0.8 | 36.9±0.8 | 36.9±0.8 | 0.390 | 0.697 | |

| Respiratory rate (/min) | 21.1±3.7 | 21.2±3.8 | 20.8±3.4 | 0.899 | 0.369 | |

| Pulse (/min) | 89.7±18.2 | 90.7±18.5 | 87.6±17.4 | 1.851 | 0.065 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 135.8±24.7 | 134.9±24.3 | 137.6±25.5 | 1.168 | 0.243 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.5±13.8 | 77.0±12.7 | 78.4±15.9 | 1.103 | 0.271 | |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 8.19±5.85 | 8.20±5.79 | 8.16±5.98 | 0.075 | 0.940 | |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 137.1±6.6 | 137.1±6.7 | 137.1±6.3 | 0.081 | 0.935 | |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 10.8±5.0 | 10.9±5.2 | 10.5±4.5 | 0.815 | 0.415 | |

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.9±6.7 | 36.1±6.7 | 35.5±6.7 | 1.002 | 0.317 | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 34.2±5.2 | 34.5±5.1 | 33.7±5.5 | 1.683 | 0.093 | |

| CURB-65 Score | 1.42±0.99 | 1.44±0.98 | 1.37±1.01 | 0.744 | 0.457 | |

| PSI Score | 96.5±29.5 | 96.9±29.5 | 95.5±29.6 | 0.524 | 0.600 | |

| Death [n(%)] | 47(8.9) | 34(9.5) | 13(7.6) | 0.527 | 0.468 |

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PSI, Pneumonia Severity Index.

In the univariate analyses, the frequencies of age ≥85 yrs, respiratory rate ≥30/min, pulse ≥125/min, urea ≥11 mmol/L, albumin 25–34.9 g/L and albumin ≥35 g/L were significantly higher in the dead patients than in the surviving patients (p<0.05) (Table 2). Multivariate analyses were performed using the significant risk factors determined in the univariate analysis. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that age, pulse, urea and albumin (APUA) were independent risk predictors (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Survival and Death Patients in the Training Set

| Variables | Survival (N=325) |

Death (N=34) |

t or χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (males/females) | 193/132 | 19/15 | 0.156 | 0.693 |

| Age (years) | 71.5±11.5 | 76.7±10.9 | 2.497 | 0.013 |

| Age<64yrs | 89(27.4) | 4(11.8) | 7.433 | 0.024 |

| Age 65~84yrs | 196(60.3) | 21(61.8) | ||

| Age ≥85yrs | 40(12.3) | 9(26.5) | ||

| Ethnicity [n(%)] | ||||

| Han | 310(95.4) | 32(94.1) | 0.954 | 0.621 |

| Other | 11(3.4) | 2(5.9) | ||

| Unknown | 4(1.2) | 0(0.0) | ||

| Confusion [n(%)] | 36(11.1) | 7(20.6) | 1.816 | 0.178 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.9±0.8 | 36.9±1.0 | 0.312 | 0.755 |

| Temperature <35°C or ≥40°C [n(%)] | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | ||

| Respiratory rate (/min) | 21.0±3.6 | 22.7±5.7 | 1.667 | 0.104 |

| Respiratory rate ≥30/min [n(%)] | 14(4.3) | 5(14.7) | 4.727 | 0.030 |

| Pulse (/min) | 89.2±17.1 | 105.4±24.8 | 3.711 | 0.001 |

| Pulse≥125/min [n(%)] | 12(3.7) | 6(17.6) | 9.826 | 0.002 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 135.2±23.6 | 132.1±30.0 | 0.579 | 0.566 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.0±12.6 | 76.6±13.4 | 0.193 | 0.847 |

| SBP <90mmHg [n(%)] | 6(1.8) | 2(5.9) | 0.170* | |

| Low BP(SBP<90 or DBP≤60mmHg) [n(%)] | 35(10.8) | 4(11.8) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 7.87±5.51 | 11.32±7.37 | 3.350 | 0.001 |

| Urea≥11mmol/L [n(%)] | 53(16.3) | 16(47.1) | 18.747 | <0.001 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 137.4±6.6 | 134.4±7.9 | 2.508 | 0.013 |

| Sodium<130mmol/L [n(%)] | 31(9.5) | 6(17.6) | 1.400 | 0.237 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 10.78±5.06 | 12.14±6.66 | 1.443 | 0.150 |

| Glucose≥14mmol/L [n(%)] | 61(18.8) | 8(23.5) | 0.449 | 0.503 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 36.4±6.8 | 34.0±5.9 | 1.945 | 0.053 |

| Hematocrit<30% [n(%)] | 56(17.2) | 6(17.6) | 0.004 | 0.951 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 34.8±5.0 | 31.7±4.7 | 3.465 | 0.001 |

| Albumin <25g/L | 165(50.8) | 5(14.7) | 20.840 | <0.001 |

| Albumin 25~34.9 g/L | 155(47.7) | 26(76.5) | ||

| Albumin≥35 g/L | 5(1.5) | 3(8.8) |

Note: *Fisher’s exact test.

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

Table 3.

The Risk Factors of in-Hospital Mortality in the Training Set

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aging | Age<64yrs | 1 | ||

| Age 65~84yrs | 2.224 | 0.691~7.159 | 0.180 | |

| Age≥85yrs | 4.780 | 1.299~17.591 | 0.019 | |

| Pulse≥125/min | 3.782 | 1.139~12.558 | 0.030 | |

| Urea≥11mmol/L | 3.510 | 1.583~7.784 | 0.002 | |

| Hypoproteinemia | Albumin≥35 g/L | 1 | ||

| Albumin 25~34.9 g/L | 4.929 | 1.787~13.595 | 0.002 | |

| Albumin<25g/L | 12.463 | 1.933~80.353 | 0.008 |

Notes: Multiple logistic regression analysis, in-hospital mortality was considered as the dependent variables in a multiple logistic regression analysis with aging, respiratory rate≥30/min, pulse≥125/min, urea≥11mmol/L and hypoproteinemia as independent variables.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

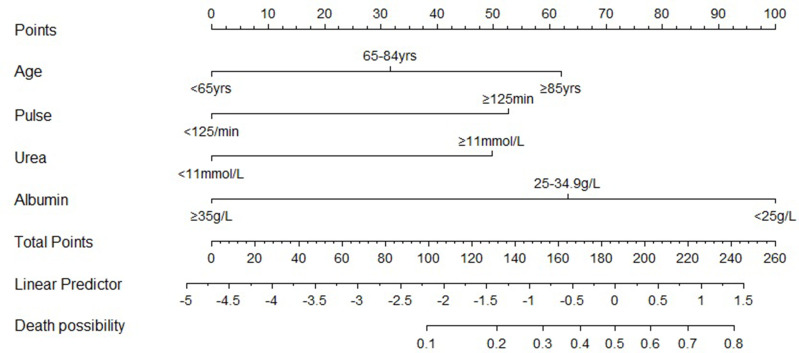

Based on these results, we developed a nomogram (APUA model) for predicting in-hospital mortality of CAP in T2DM patients. The nomogram illustrated that serum albumin had the largest contribution to prognosis in the APUA model (Figure 1). For example, a patient aged 87 years (62.02 points) had pulse 94/min (0 point), urea 7.3 mmol/L (0 point) and albumin 30.6g/L (63.23 points). The total score was 62.02 +0 + 0 + 63.23 = 125.25, and the predicted risk of in-hospital mortality was 17.6%. A web calculator based on the APUA model was developed to estimate the individualized risk of in-hospital mortality (https://doctorma.shinyapps.io/DynNomapp/).

Figure 1.

Nomogram for predicting the risk of in-hospital mortality in community-acquired pneumonia patients with type 2 diabetes.

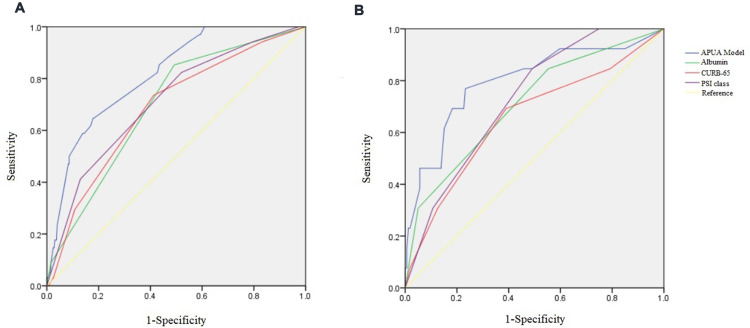

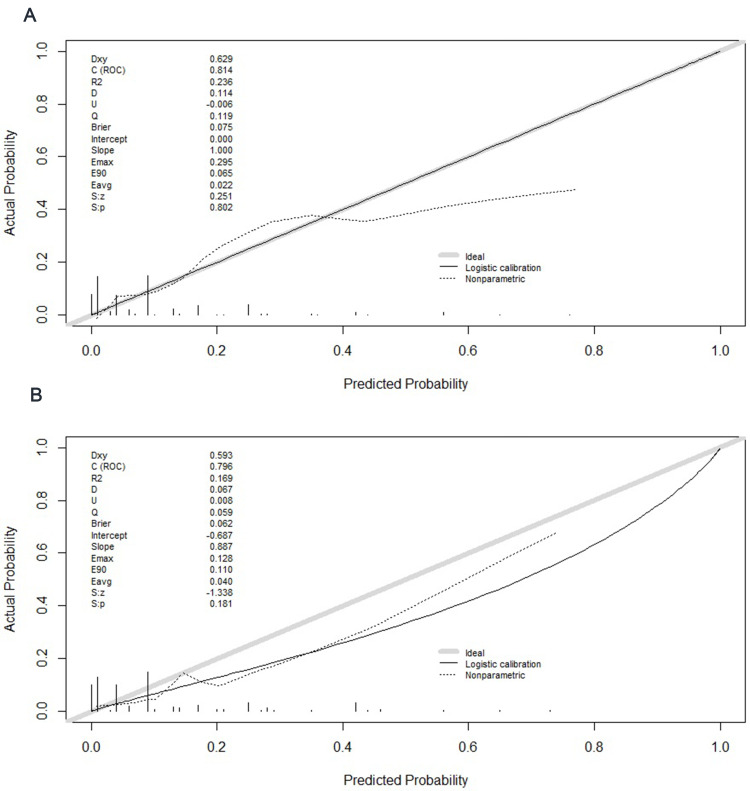

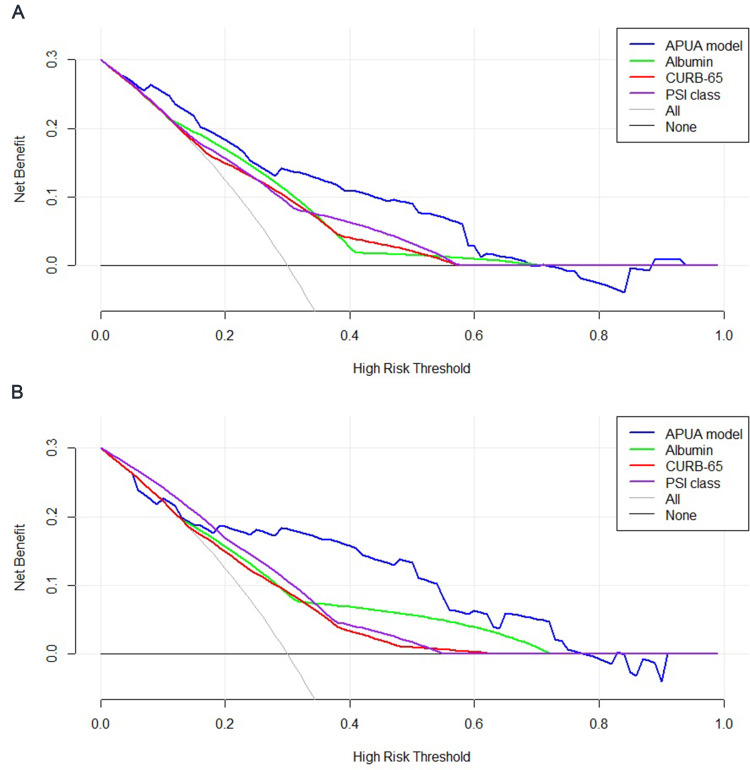

In the training set, the AUC of the APUA model was 0.814 (95% CI: 0.770–0.853), which was higher than the AUCs of albumin alone, CURB-65 and PSI class (p<0.05) (Table 4) (Figure 2A). Compared with albumin alone, CURB-65 and PSI class, the NRIs of the APUA model were 0.861 (0.533–1.189), 0.766 (0.462–1.070) and 0.815 (0.493–1.137), respectively (p<0.001) (Table 5). The IDIs of the APUA model were 0.080 (0.032–0.127), 0.087 (0.040–0.134) and 0.076 (0.023–0.128), respectively (p<0.05) (Table 5). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test (χ2=5.298, p=0.808) and calibration plot (p=0.802) showed excellent agreement between the predicted possibility and the actual observation in the APUA model (Figure 3A). In the DCA, the APUA model showed better net benefit than albumin alone, CURB-65 and PSI class (Figure 4A).

Table 4.

The Accuracy of APUA Model, Serum Albumin Alone, CURB-65 and PSI Class for Evaluating the Risk of in-Hospital Mortality in Community-Acquired Pneumonia Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

| Variables | AUC (95% CI) | SE | P | P* | P# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set (N=359) | |||||

| APUA model | 0.814(0.770~0.853) | 0.034 | <0.001 | ||

| Albumin | 0.695(0.645~0.743) | 0.037 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| CURB-65 | 0.686(0.635~0.733) | 0.045 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.864 |

| PSI class | 0.710(0.661~0.757) | 0.044 | <0.001 | 0.020 | 0.804 |

| Validation set (N=172) | |||||

| APUA model | 0.796(0.728~0.854) | 0.076 | <0.001 | ||

| Albumin | 0.710(0.636~0.777) | 0.072 | 0.003 | 0.232 | |

| CURB-65 | 0.655(0.578~0.725) | 0.086 | 0.073 | 0.067 | 0.645 |

| PSI class | 0.727(0.654~0.792) | 0.057 | <0.001 | 0.343 | 0.870 |

Notes: *Compared with APUA model, #Compared with Albumin alone.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error; PSI, pneumonia severity index.

Figure 2.

The receiver operator characteristic curve of the APUA model, serum albumin alone, CURB-65 and PSI class for evaluating the risk of in-hospital mortality in community-acquired pneumonia patients with type 2 diabetes. (A) Training set; (B) Validation set.

Table 5.

Comparison of Serum Albumin Alone, CURB-65 and PSI Class with The Accuracy of APUA Model for Evaluating the Risk of in-Hospital Mortality in Community-Acquired Pneumonia Patients with Type 2 Diabetes by NRI and IDI

| Variables | NRI (95% CI) | P | IDI (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set (N=359) | ||||

| Albumin | 0.861(0.533~1.189) | <0.001 | 0.080(0.032~0.127) | 0.001 |

| CURB-65 | 0.766(0.462~1.070) | <0.001 | 0.087(0.040~0.134) | <0.001 |

| PSI class | 0.815(0.493~1.137) | <0.001 | 0.076(0.023~0.128) | 0.005 |

| Validation set (N=172) | ||||

| Albumin | 0.599(0.041~1.157) | 0.035 | 0.067(−0.033~0.167) | 0.188 |

| CURB-65 | 0.693(0.170~1.216) | 0.009 | 0.109(0.027~0.191) | 0.010 |

| PSI class | 0.643(0.119~1.166) | 0.016 | 0.086(0.005~0.168) | 0.038 |

Abbreviations: NRI, net reclassification improvement; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; CI, confidence interval; PSI, Pneumonia Severity Index.

Figure 3.

Calibration curves of the APUA model for predicting in-hospital mortality in community-acquired pneumonia patients with type 2 diabetes. (A) Training set; (B) Validation set.

Figure 4.

Decision curve analysis of the APUA model for predicting in-hospital mortality in community-acquired pneumonia patients with type 2 diabetes. (A) Training set; (B) Validation set.

In the validation set, the AUC of the APUA model was 0.796 (0.728–0.854), which was higher than the AUCs of albumin alone, CURB-65 and PSI class, although without statistically significant differences (p>0.05) (Table 4) (Figure 2B). Compared with albumin alone, CURB-65 and PSI class, the NRIs of the APUA model were 0.599 (0.041–1.157), 0.693 (0.170–1.216) and 0.643 (0.119–1.166), respectively (p<0.05) (Table 5). Compared with albumin alone, CURB-65 and PSI class, the IDIs of the APUA model were 0.109 (0.027–0.191) and 0.086 (0.005–0.168), respectively (p<0.05) (Table 5). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test (χ2=7.426, p=0.593) and calibration plot (p=0.181) showed excellent agreement between the predicted possibility and the actual observation in the APUA model (Figure 3B). In the DCA, the APUA model showed better net benefit than albumin alone, CURB-65 and PSI class (Figure 4B).

The sensitivities, specificities and Youden’s index are shown in Table 6. The optimal cutoff point of the APUA model was the predicted risk of in-hospital mortality ≥10%. The sensitivity was 68.1% and the specificity was 80.2%. The patients were divided into five groups according to the predicted risk of mortality by the APUA model. The actual mortalities increased with the predicted risk of mortality by the APUA model (Table 7).

Table 6.

The Sensitivities, Specificities and Youden’s Index of APUA Model in Community-Acquired Pneumonia Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

| Predicted Risk | Training Set (N=359) | Validation Set (N=172) | All (N=531) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sen (%) | Spe (%) | Youden’s Index | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | Youden’s Index | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | Youden’s Index | |

| 5% | 88.2 | 53.2 | 0.415 | 84.6 | 50.9 | 0.356 | 87.2 | 52.5 | 0.397 |

| 10% | 64.7 | 81.8 | 0.466 | 76.9 | 76.7 | 0.537 | 68.1 | 80.2 | 0.483 |

| 20% | 50.0 | 91.4 | 0.414 | 61.5 | 84.9 | 0.464 | 53.2 | 89.3 | 0.424 |

| 30% | 17.6 | 96.9 | 0.146 | 46.2 | 94.3 | 0.405 | 25.5 | 96.1 | 0.216 |

| 40% | 14.7 | 97.5 | 0.122 | 38.5 | 94.3 | 0.328 | 21.3 | 96.5 | 0.178 |

| 50% | 5.9 | 98.5 | 0.043 | 15.4 | 99.4 | 0.148 | 8.5 | 98.8 | 0.073 |

Abbreviations: Sen, sensitivity; Spe, specificity.

Table 7.

The Actual Mortality in Patients with Different Predicted Risk of Mortality by APUA Model

| Predicted Risk of Mortality | N | Actual Mortality (%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| 0~4.9% | 260 | 2.3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5~9.9% | 143 | 6.3 | 2.843(0.991~8.157) | 0.052 | 2.293(0.764~6.879) | 0.139 |

| 10~19.9% | 51 | 13.7 | 6.735(2.162~20.983) | 0.001 | 5.028(1.469~17.206) | 0.010 |

| 20~29.9% | 46 | 28.3 | 16.677(5.935~46.857) | <0.001 | 11.195(3.325~37.699) | <0.001 |

| ≥30% | 31 | 38.7 | 26.737(9.033~79.142) | <0.001 | 15.039(3.594~62.928) | <0.001 |

Notes: Model 1: univariate logistic regression analysis. Model 2: multiple logistic regression analysis, adjusted for sex, age and PSI score.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PSI, pneumonia severity index.

Discussion

This study established a tool termed the APUA model for predicting mortality of CAP, adapted for patients with T2DM. The APUA model is based on serum albumin, and consists of age, pulse, urea and albumin. This model has several advantages. First, the APUA model is relatively simpler and consists of only four risk factors. Urea and albumin can be tested in both primary and tertiary hospitals. Hence, the APUA model can be used in many medical institutions. Second, the APUA model is a fast assessment system. These factors can be rapidly obtained after admission, and the severity of CAP can be quickly evaluated by the APUA model. Moreover, a web calculator was developed, which is convenient for use in clinical application. Third, the APUA model is suitable for T2DM patients with CAP. In T2DM patients with CAP, simple APUA model was superior to CURB-65 and PSI class. The AUCs of the APUA model were about 0.8 for predicting in-hospital mortality of CAP, and were higher than CURB-65 and PSI class. NRI and IDI are two novel metrics for evaluating improvement in discrimination. AUC, NRI and IDI offer complementary information. In this study, the results of NRI and IDI were in accordance with the results of AUC. DCA was performed to assess the performance of the APUA model. The net benefit of the APUA model was better than CURB-65 and PSI class.

Studies from Japan and Korea showed that serum albumin is not less accurate than CURB-65 or PSI class for predicting 30-day mortality in CAP patients.26,27 In this study, hypoalbuminemia was closely correlated with in-hospital mortality of CAP in T2DM patients. Compared to T2DM patients with albumin ≥35 g/L, T2DM patients with albumin 25–34.9 g/L [OR= 4.929] and albumin <25 g/L [OR= 12.463] were more likely to die at the time of hospitalization. The predictive accuracy of albumin alone was similar to CURB-65 or PSI class, which may be related to the following mechanisms. First, hypoalbuminemia was common in CAP patients on admission, but most patients recovered during follow-up visits.28 The decline of serum albumin during early phase after admission was closely correlated with inflammatory proteins.29 Therefore, the level of serum albumin reflected the degree of inflammatory response. The lower the level of serum albumin, the more severe was the inflammatory response. Second, serum albumin was associated with the severity of infection. Hypoalbuminemia on admission was an independent risk factor for the development of bacteremia, parapneumonic effusion or empyema in patients with CAP.30,31 Third, acute cardiac events were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality in CAP patients. Hypoalbuminemia was a predictor of acute cardiac events.32,33

Some studies have proven that hypoalbuminemia significantly improved the performance of CURB-65 and PSI class for predicting mortality in patients with CAP.17,26,34,35 However, CURB-65 and PSI class, particularly PSI class, are complicated scoring systems. Serum albumin makes the systems more complex. In this study, we developed a tool based on serum albumin. After combining with age, pulse and urea, the prognostic performance of serum albumin was increased. The AUCs increased from about 0.7 to about 0.8.

This study had some limitations. First, the level of glucose was similar between dead patients and surviving patients with T2DM. Glucose levels on admission can predict mortality in patients with CAP without diabetes, but not with diabetes.36 Glycemic gap was associated with mortality in diabetic CAP patients.13 Macro and microvascular complications also increased infection-related mortality in patients with T2DM.37 Glycemic gap, micro and macrovascular complications cannot be quickly identified after admission or tested in primary hospital. Therefore, these potential risk factors were not included in this study. However, the validation of the APUA model based on four risk factors demonstrated a good performance. Second, we performed an internal validation in this study, but the validation population was small. So the APUA model should be validated in a larger population.

In summary, the APUA model is a simple and accurate tool for predicting in-hospital mortality of CAP, adapted for patients with T2DM. The predictive performance of the APUA model was better than the CURB-65 and PSI class.

Consent Statement

This was a retrospective study. Data were extracted from the Hospital Information System. We covered patient data confidentiality. Personal information of the patients, such as name and telephone number, were not extracted. So Informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of the First Hospital of Qinhuangdao, and this study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure

The authors have no relevant funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partouche H, Lepoutre A, Vaure CBD, Poisson T, Toubiana L, Gilberg S. Incidence of all-cause adult community-acquired pneumonia in primary care settings in France. Med Mal Infect. 2018;48:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopardo GD, Fridman D, Raimondo E, et al. Incidence rate of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based prospective active surveillance study in three cities in South America. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takaki M, Nakama T, Ishida M, et al. High incidence of community-acquired pneumonia among rapidly aging population in Japan: a prospective hospital-based surveillance. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2014;67:269–275. doi: 10.7883/yoken.67.269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heo JY, Seo YB, Choi WS, et al. Incidence and case fatality rates of community-acquired pneumonia and pneumococcal diseases among Korean adults: catchment population-based analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas, 9th edn. Brussels, Belgium; 2019. Available from: http://www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed September16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres A, Blasi F, Dartois N, Akova M. Which individuals are at increased risk of pneumococcal disease and why? Impact of COPD, asthma, smoking, diabetes, and/or chronic heart disease on community-acquired pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease. Thorax. 2015;70:984–989. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao B, Huang Y, She DY, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Chinese Thoracic Society, Chinese Medical Association. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:1320–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–e67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 2009;64(Suppl 3):iii1–55. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyles TH, Brink A, Calligaro GL, et al.; South African Thoracic S and Federation of Infectious Diseases Societies of Southern A. South African guideline for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:1469–1502. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.05.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Akram AR, et al. Severity assessment tools for predicting mortality in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010;65:878–883. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.133280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen PC, Liao WI, Wang YC, et al. An elevated glycemic gap is associated with adverse outcomes in diabetic patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1456. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irfan M, Hussain SF, Mapara K, et al. Community acquired pneumonia: risk factors associated with mortality in a tertiary care hospitalized patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:448–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naffaa ME, Mustafa M, Azzam M, et al. Serum inorganic phosphorus levels predict 30-day mortality in patients with community acquired pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:332. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1094-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holter JC, Ueland T, Jenum PA, et al. Risk factors for long-term mortality after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia: a 5-year prospective follow-up study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viasus D, Garcia-Vidal C, Simonetti A, et al. Prognostic value of serum albumin levels in hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect. 2013;66:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han X, Zhou F, Li H, et al. Effects of age, comorbidity and adherence to current antimicrobial guidelines on mortality in hospitalized elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:192. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3098-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanz-Paris A, Martin-Palmero A, Gomez-Candela C, et al. GLIM criteria at hospital admission predict 8-year all-cause mortality in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from VIDA study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeyaraman K, Berhane T, Hamilton M, Chandra AP, Falhammar H. Mortality in patients with diabetic foot ulcer: a retrospective study of 513 cases from a single Centre in the Northern Territory of Australia. BMC Endocr Disord. 2019;19:1. doi: 10.1186/s12902-018-0327-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Alessandro C, Barsotti M, Cianchi C, et al. Nutritional aspects in diabetic CKD patients on tertiary care. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang CH, Chiu CH, Chen IW, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and outcomes of community-onset bacterial bloodstream infections in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;15:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang CH, Tsai JS, Chen IW, Hsu BR, Huang MJ, Huang YY. Risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes complicated by community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114:916–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377–382. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeon Lee S, Cha SI, Seo H, et al. Multimarker prognostication for hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Intern Med. 2016;55:887–893. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.5764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyazaki H, Nagata N, Akagi T, et al. Comprehensive analysis of prognostic factors in hospitalized patients with pneumonia occurring outside hospital: serum albumin is not less important than pneumonia severity assessment scale. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hedlund J. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalisation. Factors of importance for the short-and long term prognosis. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1995;97:1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harimurti K, Setiati S. C-reactive protein levels and decrease of albumin levels in hospitalized elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Acta Med Indones. 2007;39:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Washio Y, Ito A, Kumagai S, Ishida T, Yamazaki A. A model for predicting bacteremia in patients with community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia: a retrospective observational study. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:24. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0572-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Murray MP, Scally C, Fawzi A, Hill AT. Risk factors for complicated parapneumonic effusion and empyema on presentation to hospital with community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2009;64:592–597. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.105080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cilli A, Cakin O, Aksoy E, et al. Acute cardiac events in severe community-acquired pneumonia: a multicenter study. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:2212–2219. doi: 10.1111/crj.12791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viasus D, Garcia-Vidal C, Manresa F, Dorca J, Gudiol F, Carratala J. Risk stratification and prognosis of acute cardiac events in hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect. 2013;66:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, Kim J, Kim K, et al. Albumin and C-reactive protein have prognostic significance in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Crit Care. 2011;26:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu JL, Xu F, Zhou H, et al. Expanded CURB-65: a new score system predicts severity of community-acquired pneumonia with superior efficiency. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22911. doi: 10.1038/srep22911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lepper PM, Ott S, Nuesch E, et al.; German Community Acquired Pneumonia Competence N. Serum glucose levels for predicting death in patients admitted to hospital for community acquired pneumonia: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e3397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cardoso CR, Salles GF. Macro and microvascular complications are determinants of increased infection-related mortality in Brazilian type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]